Module 8: Analysis and Synthesis

Analytical thesis statements, learning objective.

- Describe strategies for writing analytical thesis statements

- Identify analytical thesis statements

In order to write an analysis, you want to first have a solid understanding of the thing you are analyzing. Remember, when you are analyzing as a writer, you are:

- Breaking down information or artifacts into component parts

- Uncovering relationships among those parts

- Determining motives, causes, and underlying assumptions

- Making inferences and finding evidence to support generalizations

You may be asked to analyze a book, an essay, a poem, a movie, or even a song. For example, let’s suppose you want to analyze the lyrics to a popular song. Pretend that a rapper called Escalade has the biggest hit of the summer with a song titled “Missing You.” You listen to the song and determine that it is about the pain people feel when a loved one dies. You have already done analysis at a surface level and you want to begin writing your analysis. You start with the following thesis statement:

Escalade’s hit song “Missing You” is about grieving after a loved one dies.

There isn’t much depth or complexity to such a claim because the thesis doesn’t give much information. In order to write a better thesis statement, we need to dig deeper into the song. What is the importance of the lyrics? What are they really about? Why is the song about grieving? Why did he present it this way? Why is it a powerful song? Ask questions to lead you to further investigation. Doing so will help you better understand the work, but also help you develop a better thesis statement and stronger analytical essay.

Formulating an Analytical Thesis Statement

When formulating an analytical thesis statement in college, here are some helpful words and phrases to remember:

- What? What is the claim?

- How? How is this claim supported?

- So what? In other words, “What does this mean, what are the implications, or why is this important?”

Telling readers what the lyrics are might be a useful way to let them see what you are analyzing and/or to isolate specific parts where you are focusing your analysis. However, you need to move far beyond “what.” Instructors at the college level want to see your ability to break down material and demonstrate deep thinking. The claim in the thesis statement above said that Escalade’s song was about loss, but what evidence do we have for that, and why does that matter?

Effective analytical thesis statements require digging deeper and perhaps examining the larger context. Let’s say you do some research and learn that the rapper’s mother died not long ago, and when you examine the lyrics more closely, you see that a few of the lines seem to be specifically about a mother rather than a loved one in general.

Then you also read a recent interview with Escalade in which he mentions that he’s staying away from hardcore rap lyrics on his new album in an effort to be more mainstream and reach more potential fans. Finally, you notice that some of the lyrics in the song focus on not taking full advantage of the time we have with our loved ones. All of these pieces give you material to write a more complex thesis statement, maybe something like this:

In the hit song “Missing You,” Escalade draws on his experience of losing his mother and raps about the importance of not taking time with family for granted in order to connect with his audience.

Such a thesis statement is focused while still allowing plenty of room for support in the body of your paper. It addresses the questions posed above:

- The claim is that Escalade connects with a broader audience by rapping about the importance of not taking time with family for granted in his hit song, “Missing You.”

- This claim is supported in the lyrics of the song and through the “experience of losing his mother.”

- The implications are that we should not take the time we have with people for granted.

Certainly, there may be many ways for you to address “what,” “how,” and “so what,” and you may want to explore other ideas, but the above example is just one way to more fully analyze the material. Note that the example above is not formulaic, but if you need help getting started, you could use this template format to help develop your thesis statement.

Through ________________(how?), we can see that __________________(what?), which is important because ___________________(so what?). [1]

Just remember to think about these questions (what? how? and so what?) as you try to determine why something is what it is or why something means what it means. Asking these questions can help you analyze a song, story, or work of art, and can also help you construct meaningful thesis sentences when you write an analytical paper.

Key Takeaways for analytical theses

Don’t be afraid to let your claim evolve organically . If you find that your thinking and writing don’t stick exactly to the thesis statement you have constructed, your options are to scrap the writing and start again to make it fit your claim (which might not always be possible) or to modify your thesis statement. The latter option can be much easier if you are okay with the changes. As with many projects in life, writing doesn’t always go in the direction we plan, and strong analysis may mean thinking about and making changes as you look more closely at your topic. Be flexible.

Use analysis to get you to the main claim. You may have heard the simile that analysis is like peeling an onion because you have to go through layers to complete your work. You can start the process of breaking down an idea or an artifact without knowing where it will lead you or without a main claim or idea to guide you. Often, careful assessment of the pieces will bring you to an interesting interpretation of the whole. In their text Writing Analytically , authors David Rosenwasser and Jill Stephen posit that being analytical doesn’t mean just breaking something down. It also means constructing understandings. Don’t assume you need to have deeper interpretations all figured out as you start your work.

When you decide upon the main claim, make sure it is reasoned . In other words, if it is very unlikely anyone else would reach the same interpretation you are making, it might be off base. Not everyone needs to see an idea the same way you do, but a reasonable person should be able to understand, if not agree, with your analysis.

Look for analytical thesis statements in the following activity.

Using Evidence

An effective analytical thesis statement (or claim) may sound smart or slick, but it requires evidence to be fully realized. Consider movie trailers and the actual full-length movies they advertise as an analogy. If you see an exciting one-minute movie trailer online and then go see the film only to leave disappointed because all the good parts were in the trailer, you feel cheated, right? You think you were promised something that didn’t deliver in its execution. A paper with a strong thesis statement but lackluster evidence feels the same way to readers.

So what does strong analytical evidence look like? Think again about “what,” “how,” and “so what.” A claim introduces these interpretations, and evidence lets you show them. Keep in mind that evidence used in writing analytically will build on itself as the piece progresses, much like a good movie builds to an interesting climax.

Key Takeaways about evidence

Be selective about evidence. Having a narrow thesis statement will help you be selective with evidence, but even then, you don’t need to include any and every piece of information related to your main claim. Consider the best points to back up your analytic thesis statement and go deeply into them. (Also, remember that you may modify your thesis statement as you think and write, so being selective about what evidence you use in an analysis may actually help you narrow down what was a broad main claim as you work.) Refer back to our movie theme in this section: You have probably seen plenty of films that would have been better with some parts cut out and more attention paid to intriguing but underdeveloped characters and/or ideas.

Be clear and explicit with your evidence. Don’t assume that readers know exactly what you are thinking. Make your points and explain them in detail, providing information and context for readers, where necessary. Remember that analysis is critical examination and interpretation, but you can’t just assume that others always share or intuit your line of thinking. Need a movie analogy? Think back on all the times you or someone you know has said something like “I’m not sure what is going on in this movie.”

Move past obvious interpretations. Analyzing requires brainpower. Writing analytically is even more difficult. Don’t, however, try to take the easy way out by using obvious evidence (or working from an obvious claim). Many times writers have a couple of great pieces of evidence to support an interesting interpretation, but they feel the need to tack on an obvious idea—often more of an observation than analysis—somewhere in their work. This tendency may stem from the conventions of the five-paragraph essay, which features three points of support. Writing analytically, though, does not mean writing a five-paragraph essay (not much writing in college does). Develop your other evidence further or modify your main idea to allow room for additional strong evidence, but avoid obvious observations as support for your main claim. One last movie comparison? Go take a look at some of the debate on predictable Hollywood scripts. Have you ever watched a movie and felt like you have seen it before? You have, in one way or another. A sharp reader will be about as interested in obvious evidence as he or she will be in seeing a tired script reworked for the thousandth time.

One type of analysis you may be asked to write is a literary analysis, in which you examine a piece of text by breaking it down and looking for common literary elements, such as character, symbolism, plot, setting, imagery, and tone.

The video below compares writing a literary analysis to analyzing a team’s chances of winning a game—just as you would look at various factors like the weather, coaching, players, their record, and their motivation for playing. Similarly, when analyzing a literary text you want to look at all of the literary elements that contribute to the work.

The video takes you through the story of Cinderalla as an example, following the simplest possible angle (or thesis statement), that “Dreams can come true if you don’t give up.” (Note that if you were really asked to analyze Cinderella for a college class, you would want to dig deeper to find a more nuanced and interesting theme, but it works well for this example.) To analyze the story with this theme in mind, you’d want to consider the literary elements such as imagery, characters, dialogue, symbolism, the setting, plot, and tone, and consider how each of these contribute to the message that “Dreams can come true if you don’t give up.”

You can view the transcript for “How to Analyze Literature” here (opens in new window) .

- UCLA Undergraduate Writing Center. "What, How and So What?" Approaching the Thesis as a Process. https://wp.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/UWC_handouts_What-How-So-What-Thesis-revised-5-4-15-RZ.pdf ↵

- Keys to Successful Analysis. Authored by : Guy Krueger. Provided by : University of Mississippi. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Thesis Statement Activity. Authored by : Excelsior OWL. Located at : https://owl.excelsior.edu/research/thesis-or-focus/thesis-or-focus-thesis-statement-activity/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- What is Analysis?. Authored by : Karen Forgette. Provided by : University of Mississippi. License : CC BY: Attribution

- How to Analyze Literature. Provided by : HACC, Central Pennsylvania's Community College. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pr4BjZkQ5Nc . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.7: Analytical Thesis Statements

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 58364

- Lumen Learning

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objective

- Describe strategies for writing analytical thesis statements

- Identify analytical thesis statements

In order to write an analysis, you want to first have a solid understanding of the thing you are analyzing. Remember, this means:

- Breaking down information or artifacts into component parts

- Uncovering relationships among those parts

- Determining motives, causes, and underlying assumptions

- Making inferences and finding evidence to support generalizations

You may be asked to analyze a book, an essay, a poem, a movie, or even a song. For example, let’s suppose you want to analyze the lyrics to a popular song. Pretend that a rapper called Escalade has the biggest hit of the summer with a song titled “Missing You.” You listen to the song and determine that it is about the pain people feel when a loved one dies. You have already done analysis at a surface level and you want to begin writing your analysis. You start with the following thesis statement:

“Escalade’s hit song “Missing You” is about being sad after a loved one dies.”

There isn’t much depth or complexity to such a claim because the thesis doesn’t give much information. In order to write a better thesis statement, we need to dig deeper into the song. What is the importance of the lyrics? What are they really about? Why is the song about being sad? Why did he present it this way? Why is it a powerful song? Ask questions to lead you to further investigation. Doing so will help you better understand the work, but also help you develop a better thesis statement and stronger analytical essay.

Formulating an Analytical Thesis Statement

When formulating an analytical thesis statement in college, there are three words/phrases to remember:

- What? What is the claim?

- How? How is this claim supported?

- So what? In other words, “What does this mean, what are the implications, or why is this important?”

Telling readers what the lyrics are might be a useful way to let them see what you are analyzing and/or to isolate specific parts where you are focusing your analysis. However, you need to move far beyond “what.” Instructors at the college level want to see your ability to break down material and demonstrate deep thinking. The claim in the thesis statement above said that Escalade’s song was about being sad, but what evidence do we have for that, and why does that matter?

Effective analytical thesis statements require digging deeper and perhaps examining the larger context. Let’s say you do some research and learn that the rapper’s mother died not long ago, and when you examine the lyrics more closely, you see that a few of the lines seem to be specifically about a mother rather than a loved one in general.

Then you also read a recent interview with Escalade in which he mentions that he’s staying away from hardcore rap lyrics on his new album in an effort to be more mainstream and reach more potential fans. Finally, you notice that some of the lyrics in the song focus on not taking full advantage of the time we have with our loved ones. All of these pieces give you material to write a more complex thesis statement, maybe something like this:

“In the hit song ‘Missing You,’ Escalade draws on his experience of losing his mother and raps about the importance of not taking time with family for granted in order to connect with a broad audience.”

Such a thesis statement is focused while still allowing plenty of room for support in the body of your paper. It addresses the questions posed above:

- The claim is that Escalade connects with a broader audience by rapping about the importance of not taking time with family for granted in his hit song, “Missing You.”

- This claim is supported in the lyrics of the song and through the “experience of losing his mother.”

- The implications are that we should not take valuable things for granted.

Certainly, there may be many ways for you to address “what,” “how,” and “so what,” and you may want to explore other ideas, but the above example is just one way to more fully analyze the material. Note that the example above is not formulaic, but if you need help getting started, you could use this template format to help develop your thesis statement.

Through ________________(how?), we can see that __________________(what?), which is important because ___________________(so what?). [1]

Just remember to think about these questions (what? how? and so what?) as you try to determine why something is what it is or why something means what it means. Asking these questions can help you analyze a song, story, or work of art, and can also help you construct meaningful thesis sentences when you write an analytical paper.

Key Takeaways for analytical theses

Don’t be afraid to let your claim evolve organically . If you find that your thinking and writing don’t stick exactly to the thesis statement you have constructed, your options are to scrap the writing and start again to make it fit your claim (which might not always be possible) or to modify your thesis statement. The latter option can be much easier if you are okay with the changes. As with many projects in life, writing doesn’t always go in the direction we plan, and strong analysis may mean thinking about and making changes as you look more closely at your topic. Be flexible.

Use analysis to get you to the main claim. You may have heard the simile that analysis is like peeling an onion because you have to go through layers to complete your work. You can start the process of breaking down an idea or an artifact without knowing where it will lead you or without a main claim or idea to guide you. Often, careful assessment of the pieces will bring you to an interesting interpretation of the whole. In their text Writing Analytically , authors David Rosenwasser and Jill Stephen posit that being analytical doesn’t mean just breaking something down. It also means constructing understandings. Don’t assume you need to have deeper interpretations all figured out as you start your work.

When you decide upon the main claim, make sure it is reasoned . In other words, if it is very unlikely anyone else would reach the same interpretation you are making, it might be off base. Not everyone needs to see an idea the same way you do, but a reasonable person should be able to understand, if not agree, with your analysis.

Look for analytical thesis statements in the following activity.

https://lumenlearning.h5p.com/content/1290920118213584118/embed

Using Evidence

An effective analytical thesis statement (or claim) may sound smart or slick, but it requires evidence to be fully realized. Consider movie trailers and the actual full-length movies they advertise as an analogy. If you see an exciting one-minute movie trailer online and then go see the film only to leave disappointed because all the good parts were in the trailer, you feel cheated, right? You think you were promised something that didn’t deliver in its execution. A paper with a strong thesis statement but lackluster evidence feels the same way to readers.

So what does strong analytical evidence look like? Think again about “what,” “how,” and “so what.” A claim introduces these interpretations, and evidence lets you show them. Keep in mind that evidence used in writing analytically will build on itself as the piece progresses, much like a good movie builds to an interesting climax.

https://assessments.lumenlearning.co...essments/20272

Key Takeaways about evidence

Be selective about evidence. Having a narrow thesis statement will help you be selective with evidence, but even then, you don’t need to include any and every piece of information related to your main claim. Consider the best points to back up your analytic thesis statement and go deeply into them. (Also, remember that you may modify your thesis statement as you think and write, so being selective about what evidence you use in an analysis may actually help you narrow down what was a broad main claim as you work.) Refer back to our movie theme in this section: You have probably seen plenty of films that would have been better with some parts cut out and more attention paid to intriguing but underdeveloped characters and/or ideas.

Be clear and explicit with your evidence. Don’t assume that readers know exactly what you are thinking. Make your points and explain them in detail, providing information and context for readers, where necessary. Remember that analysis is critical examination and interpretation, but you can’t just assume that others always share or intuit your line of thinking. Need a movie analogy? Think back on all the times you or someone you know has said something like “I’m not sure what is going on in this movie.”

Move past obvious interpretations. Analyzing requires brainpower. Writing analytically is even more difficult. Don’t, however, try to take the easy way out by using obvious evidence (or working from an obvious claim). Many times writers have a couple of great pieces of evidence to support an interesting interpretation, but they feel the need to tack on an obvious idea—often more of an observation than analysis—somewhere in their work. This tendency may stem from the conventions of the five-paragraph essay, which features three points of support. Writing analytically, though, does not mean writing a five-paragraph essay (not much writing in college does). Develop your other evidence further or modify your main idea to allow room for additional strong evidence, but avoid obvious observations as support for your main claim. One last movie comparison? Go take a look at some of the debate on predictable Hollywood scripts. Have you ever watched a movie and felt like you have seen it before? You have, in one way or another. A sharp reader will be about as interested in obvious evidence as he or she will be in seeing a tired script reworked for the thousandth time.

One type of analysis you may be asked to write is a literary analysis, in which you examine a piece of text by breaking it down and looking for common literary elements, such as character, symbolism, plot, setting, imagery, and tone.

The video below compares writing a literary analysis to analyzing a team’s chances of winning a game—just as you would look at various factors like the weather, coaching, players, their record, and their motivation for playing. Similarly, when analyzing a literary text you want to look at all of the literary elements that contribute to the work.

The video takes you through the story of Cinderalla as an example, following the simplest possible angle (or thesis statement), that “Dreams can come true if you don’t give up.” (Note that if you were really asked to analyze Cinderella for a college class, you would want to dig deeper to find a more nuanced and interesting theme, but it works well for this example.) To analyze the story with this theme in mind, you’d want to consider the literary elements such as imagery, characters, dialogue, symbolism, the setting, plot, and tone, and consider how each of these contribute to the message that “Dreams can come true if you don’t give up.”

You can view the transcript for “How to Analyze Literature” here (opens in new window) .

- UCLA Undergraduate Writing Center. "What, How and So What?" Approaching the Thesis as a Process. https://wp.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/UWC_handouts_What-How-So-What-Thesis-revised-5-4-15-RZ.pdf ↵

Contributors and Attributions

- Keys to Successful Analysis. Authored by : Guy Krueger. Provided by : University of Mississippi. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Thesis Statement Activity. Authored by : Excelsior OWL. Located at : https://owl.excelsior.edu/research/thesis-or-focus/thesis-or-focus-thesis-statement-activity/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- What is Analysis?. Authored by : Karen Forgette. Provided by : University of Mississippi. License : CC BY: Attribution

- How to Analyze Literature. Provided by : HACC, Central Pennsylvania's Community College. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pr4BjZkQ5Nc . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

beginner's guide to literary analysis

Understanding literature & how to write literary analysis.

Literary analysis is the foundation of every college and high school English class. Once you can comprehend written work and respond to it, the next step is to learn how to think critically and complexly about a work of literature in order to analyze its elements and establish ideas about its meaning.

If that sounds daunting, it shouldn’t. Literary analysis is really just a way of thinking creatively about what you read. The practice takes you beyond the storyline and into the motives behind it.

While an author might have had a specific intention when they wrote their book, there’s still no right or wrong way to analyze a literary text—just your way. You can use literary theories, which act as “lenses” through which you can view a text. Or you can use your own creativity and critical thinking to identify a literary device or pattern in a text and weave that insight into your own argument about the text’s underlying meaning.

Now, if that sounds fun, it should , because it is. Here, we’ll lay the groundwork for performing literary analysis, including when writing analytical essays, to help you read books like a critic.

What Is Literary Analysis?

As the name suggests, literary analysis is an analysis of a work, whether that’s a novel, play, short story, or poem. Any analysis requires breaking the content into its component parts and then examining how those parts operate independently and as a whole. In literary analysis, those parts can be different devices and elements—such as plot, setting, themes, symbols, etcetera—as well as elements of style, like point of view or tone.

When performing analysis, you consider some of these different elements of the text and then form an argument for why the author chose to use them. You can do so while reading and during class discussion, but it’s particularly important when writing essays.

Literary analysis is notably distinct from summary. When you write a summary , you efficiently describe the work’s main ideas or plot points in order to establish an overview of the work. While you might use elements of summary when writing analysis, you should do so minimally. You can reference a plot line to make a point, but it should be done so quickly so you can focus on why that plot line matters . In summary (see what we did there?), a summary focuses on the “ what ” of a text, while analysis turns attention to the “ how ” and “ why .”

While literary analysis can be broad, covering themes across an entire work, it can also be very specific, and sometimes the best analysis is just that. Literary critics have written thousands of words about the meaning of an author’s single word choice; while you might not want to be quite that particular, there’s a lot to be said for digging deep in literary analysis, rather than wide.

Although you’re forming your own argument about the work, it’s not your opinion . You should avoid passing judgment on the piece and instead objectively consider what the author intended, how they went about executing it, and whether or not they were successful in doing so. Literary criticism is similar to literary analysis, but it is different in that it does pass judgement on the work. Criticism can also consider literature more broadly, without focusing on a singular work.

Once you understand what constitutes (and doesn’t constitute) literary analysis, it’s easy to identify it. Here are some examples of literary analysis and its oft-confused counterparts:

Summary: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” the narrator visits his friend Roderick Usher and witnesses his sister escape a horrible fate.

Opinion: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Poe uses his great Gothic writing to establish a sense of spookiness that is enjoyable to read.

Literary Analysis: “Throughout ‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ Poe foreshadows the fate of Madeline by creating a sense of claustrophobia for the reader through symbols, such as in the narrator’s inability to leave and the labyrinthine nature of the house.

In summary, literary analysis is:

- Breaking a work into its components

- Identifying what those components are and how they work in the text

- Developing an understanding of how they work together to achieve a goal

- Not an opinion, but subjective

- Not a summary, though summary can be used in passing

- Best when it deeply, rather than broadly, analyzes a literary element

Literary Analysis and Other Works

As discussed above, literary analysis is often performed upon a single work—but it doesn’t have to be. It can also be performed across works to consider the interplay of two or more texts. Regardless of whether or not the works were written about the same thing, or even within the same time period, they can have an influence on one another or a connection that’s worth exploring. And reading two or more texts side by side can help you to develop insights through comparison and contrast.

For example, Paradise Lost is an epic poem written in the 17th century, based largely on biblical narratives written some 700 years before and which later influenced 19th century poet John Keats. The interplay of works can be obvious, as here, or entirely the inspiration of the analyst. As an example of the latter, you could compare and contrast the writing styles of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Edgar Allan Poe who, while contemporaries in terms of time, were vastly different in their content.

Additionally, literary analysis can be performed between a work and its context. Authors are often speaking to the larger context of their times, be that social, political, religious, economic, or artistic. A valid and interesting form is to compare the author’s context to the work, which is done by identifying and analyzing elements that are used to make an argument about the writer’s time or experience.

For example, you could write an essay about how Hemingway’s struggles with mental health and paranoia influenced his later work, or how his involvement in the Spanish Civil War influenced his early work. One approach focuses more on his personal experience, while the other turns to the context of his times—both are valid.

Why Does Literary Analysis Matter?

Sometimes an author wrote a work of literature strictly for entertainment’s sake, but more often than not, they meant something more. Whether that was a missive on world peace, commentary about femininity, or an allusion to their experience as an only child, the author probably wrote their work for a reason, and understanding that reason—or the many reasons—can actually make reading a lot more meaningful.

Performing literary analysis as a form of study unquestionably makes you a better reader. It’s also likely that it will improve other skills, too, like critical thinking, creativity, debate, and reasoning.

At its grandest and most idealistic, literary analysis even has the ability to make the world a better place. By reading and analyzing works of literature, you are able to more fully comprehend the perspectives of others. Cumulatively, you’ll broaden your own perspectives and contribute more effectively to the things that matter to you.

Literary Terms to Know for Literary Analysis

There are hundreds of literary devices you could consider during your literary analysis, but there are some key tools most writers utilize to achieve their purpose—and therefore you need to know in order to understand that purpose. These common devices include:

- Characters: The people (or entities) who play roles in the work. The protagonist is the main character in the work.

- Conflict: The conflict is the driving force behind the plot, the event that causes action in the narrative, usually on the part of the protagonist

- Context : The broader circumstances surrounding the work political and social climate in which it was written or the experience of the author. It can also refer to internal context, and the details presented by the narrator

- Diction : The word choice used by the narrator or characters

- Genre: A category of literature characterized by agreed upon similarities in the works, such as subject matter and tone

- Imagery : The descriptive or figurative language used to paint a picture in the reader’s mind so they can picture the story’s plot, characters, and setting

- Metaphor: A figure of speech that uses comparison between two unlike objects for dramatic or poetic effect

- Narrator: The person who tells the story. Sometimes they are a character within the story, but sometimes they are omniscient and removed from the plot.

- Plot : The storyline of the work

- Point of view: The perspective taken by the narrator, which skews the perspective of the reader

- Setting : The time and place in which the story takes place. This can include elements like the time period, weather, time of year or day, and social or economic conditions

- Symbol : An object, person, or place that represents an abstract idea that is greater than its literal meaning

- Syntax : The structure of a sentence, either narration or dialogue, and the tone it implies

- Theme : A recurring subject or message within the work, often commentary on larger societal or cultural ideas

- Tone : The feeling, attitude, or mood the text presents

How to Perform Literary Analysis

Step 1: read the text thoroughly.

Literary analysis begins with the literature itself, which means performing a close reading of the text. As you read, you should focus on the work. That means putting away distractions (sorry, smartphone) and dedicating a period of time to the task at hand.

It’s also important that you don’t skim or speed read. While those are helpful skills, they don’t apply to literary analysis—or at least not this stage.

Step 2: Take Notes as You Read

As you read the work, take notes about different literary elements and devices that stand out to you. Whether you highlight or underline in text, use sticky note tabs to mark pages and passages, or handwrite your thoughts in a notebook, you should capture your thoughts and the parts of the text to which they correspond. This—the act of noticing things about a literary work—is literary analysis.

Step 3: Notice Patterns

As you read the work, you’ll begin to notice patterns in the way the author deploys language, themes, and symbols to build their plot and characters. As you read and these patterns take shape, begin to consider what they could mean and how they might fit together.

As you identify these patterns, as well as other elements that catch your interest, be sure to record them in your notes or text. Some examples include:

- Circle or underline words or terms that you notice the author uses frequently, whether those are nouns (like “eyes” or “road”) or adjectives (like “yellow” or “lush”).

- Highlight phrases that give you the same kind of feeling. For example, if the narrator describes an “overcast sky,” a “dreary morning,” and a “dark, quiet room,” the words aren’t the same, but the feeling they impart and setting they develop are similar.

- Underline quotes or prose that define a character’s personality or their role in the text.

- Use sticky tabs to color code different elements of the text, such as specific settings or a shift in the point of view.

By noting these patterns, comprehensive symbols, metaphors, and ideas will begin to come into focus.

Step 4: Consider the Work as a Whole, and Ask Questions

This is a step that you can do either as you read, or after you finish the text. The point is to begin to identify the aspects of the work that most interest you, and you could therefore analyze in writing or discussion.

Questions you could ask yourself include:

- What aspects of the text do I not understand?

- What parts of the narrative or writing struck me most?

- What patterns did I notice?

- What did the author accomplish really well?

- What did I find lacking?

- Did I notice any contradictions or anything that felt out of place?

- What was the purpose of the minor characters?

- What tone did the author choose, and why?

The answers to these and more questions will lead you to your arguments about the text.

Step 5: Return to Your Notes and the Text for Evidence

As you identify the argument you want to make (especially if you’re preparing for an essay), return to your notes to see if you already have supporting evidence for your argument. That’s why it’s so important to take notes or mark passages as you read—you’ll thank yourself later!

If you’re preparing to write an essay, you’ll use these passages and ideas to bolster your argument—aka, your thesis. There will likely be multiple different passages you can use to strengthen multiple different aspects of your argument. Just be sure to cite the text correctly!

If you’re preparing for class, your notes will also be invaluable. When your teacher or professor leads the conversation in the direction of your ideas or arguments, you’ll be able to not only proffer that idea but back it up with textual evidence. That’s an A+ in class participation.

Step 6: Connect These Ideas Across the Narrative

Whether you’re in class or writing an essay, literary analysis isn’t complete until you’ve considered the way these ideas interact and contribute to the work as a whole. You can find and present evidence, but you still have to explain how those elements work together and make up your argument.

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay

When conducting literary analysis while reading a text or discussing it in class, you can pivot easily from one argument to another (or even switch sides if a classmate or teacher makes a compelling enough argument).

But when writing literary analysis, your objective is to propose a specific, arguable thesis and convincingly defend it. In order to do so, you need to fortify your argument with evidence from the text (and perhaps secondary sources) and an authoritative tone.

A successful literary analysis essay depends equally on a thoughtful thesis, supportive analysis, and presenting these elements masterfully. We’ll review how to accomplish these objectives below.

Step 1: Read the Text. Maybe Read It Again.

Constructing an astute analytical essay requires a thorough knowledge of the text. As you read, be sure to note any passages, quotes, or ideas that stand out. These could serve as the future foundation of your thesis statement. Noting these sections now will help you when you need to gather evidence.

The more familiar you become with the text, the better (and easier!) your essay will be. Familiarity with the text allows you to speak (or in this case, write) to it confidently. If you only skim the book, your lack of rich understanding will be evident in your essay. Alternatively, if you read the text closely—especially if you read it more than once, or at least carefully revisit important passages—your own writing will be filled with insight that goes beyond a basic understanding of the storyline.

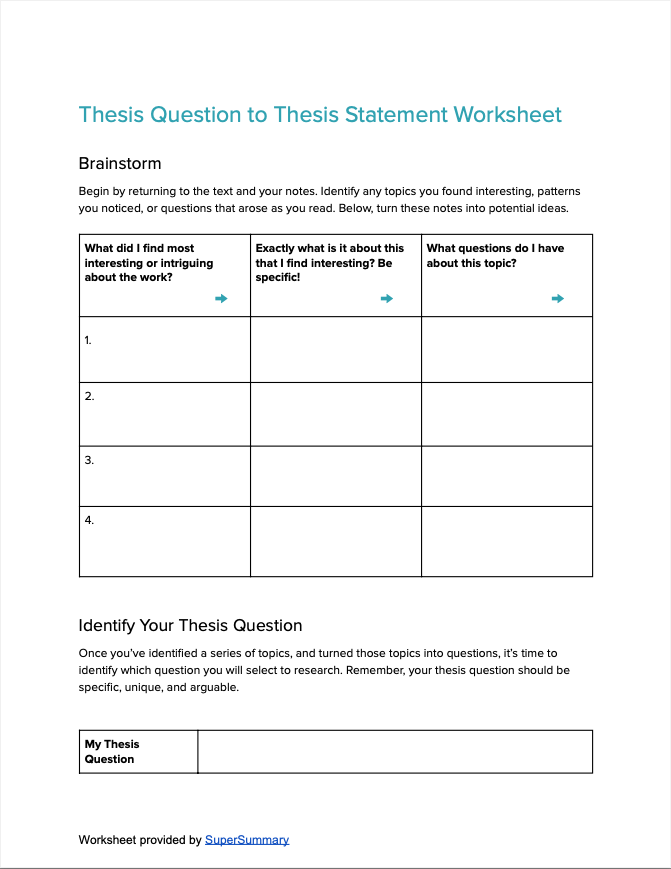

Step 2: Brainstorm Potential Topics

Because you took detailed notes while reading the text, you should have a list of potential topics at the ready. Take time to review your notes, highlighting any ideas or questions you had that feel interesting. You should also return to the text and look for any passages that stand out to you.

When considering potential topics, you should prioritize ideas that you find interesting. It won’t only make the whole process of writing an essay more fun, your enthusiasm for the topic will probably improve the quality of your argument, and maybe even your writing. Just like it’s obvious when a topic interests you in a conversation, it’s obvious when a topic interests the writer of an essay (and even more obvious when it doesn’t).

Your topic ideas should also be specific, unique, and arguable. A good way to think of topics is that they’re the answer to fairly specific questions. As you begin to brainstorm, first think of questions you have about the text. Questions might focus on the plot, such as: Why did the author choose to deviate from the projected storyline? Or why did a character’s role in the narrative shift? Questions might also consider the use of a literary device, such as: Why does the narrator frequently repeat a phrase or comment on a symbol? Or why did the author choose to switch points of view each chapter?

Once you have a thesis question , you can begin brainstorming answers—aka, potential thesis statements . At this point, your answers can be fairly broad. Once you land on a question-statement combination that feels right, you’ll then look for evidence in the text that supports your answer (and helps you define and narrow your thesis statement).

For example, after reading “ The Fall of the House of Usher ,” you might be wondering, Why are Roderick and Madeline twins?, Or even: Why does their relationship feel so creepy?” Maybe you noticed (and noted) that the narrator was surprised to find out they were twins, or perhaps you found that the narrator’s tone tended to shift and become more anxious when discussing the interactions of the twins.

Once you come up with your thesis question, you can identify a broad answer, which will become the basis for your thesis statement. In response to the questions above, your answer might be, “Poe emphasizes the close relationship of Roderick and Madeline to foreshadow that their deaths will be close, too.”

Step 3: Gather Evidence

Once you have your topic (or you’ve narrowed it down to two or three), return to the text (yes, again) to see what evidence you can find to support it. If you’re thinking of writing about the relationship between Roderick and Madeline in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” look for instances where they engaged in the text.

This is when your knowledge of literary devices comes in clutch. Carefully study the language around each event in the text that might be relevant to your topic. How does Poe’s diction or syntax change during the interactions of the siblings? How does the setting reflect or contribute to their relationship? What imagery or symbols appear when Roderick and Madeline are together?

By finding and studying evidence within the text, you’ll strengthen your topic argument—or, just as valuably, discount the topics that aren’t strong enough for analysis.

Step 4: Consider Secondary Sources

In addition to returning to the literary work you’re studying for evidence, you can also consider secondary sources that reference or speak to the work. These can be articles from journals you find on JSTOR, books that consider the work or its context, or articles your teacher shared in class.

While you can use these secondary sources to further support your idea, you should not overuse them. Make sure your topic remains entirely differentiated from that presented in the source.

Step 5: Write a Working Thesis Statement

Once you’ve gathered evidence and narrowed down your topic, you’re ready to refine that topic into a thesis statement. As you continue to outline and write your paper, this thesis statement will likely change slightly, but this initial draft will serve as the foundation of your essay. It’s like your north star: Everything you write in your essay is leading you back to your thesis.

Writing a great thesis statement requires some real finesse. A successful thesis statement is:

- Debatable : You shouldn’t simply summarize or make an obvious statement about the work. Instead, your thesis statement should take a stand on an issue or make a claim that is open to argument. You’ll spend your essay debating—and proving—your argument.

- Demonstrable : You need to be able to prove, through evidence, that your thesis statement is true. That means you have to have passages from the text and correlative analysis ready to convince the reader that you’re right.

- Specific : In most cases, successfully addressing a theme that encompasses a work in its entirety would require a book-length essay. Instead, identify a thesis statement that addresses specific elements of the work, such as a relationship between characters, a repeating symbol, a key setting, or even something really specific like the speaking style of a character.

Example: By depicting the relationship between Roderick and Madeline to be stifling and almost otherworldly in its closeness, Poe foreshadows both Madeline’s fate and Roderick’s inability to choose a different fate for himself.

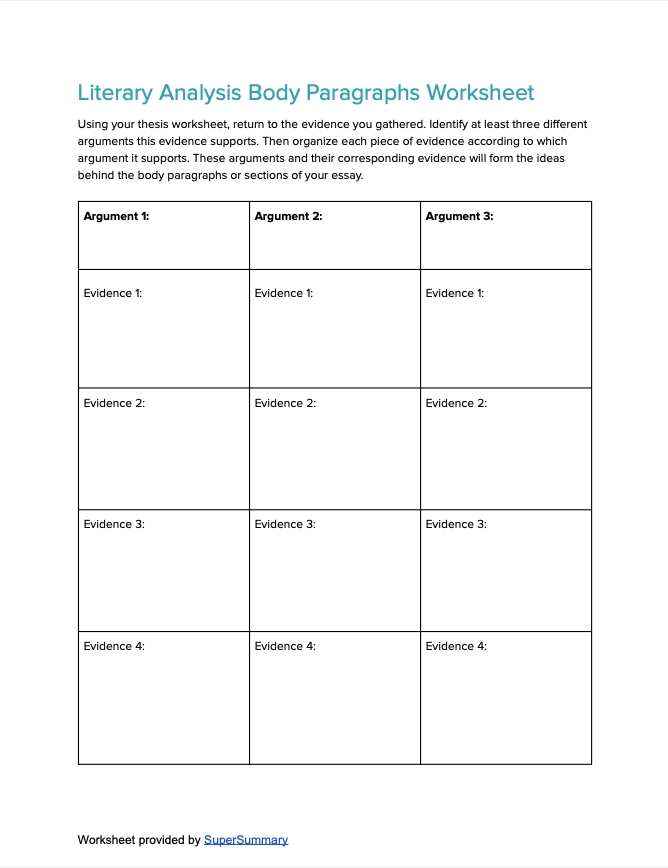

Step 6: Write an Outline

You have your thesis, you have your evidence—but how do you put them together? A great thesis statement (and therefore a great essay) will have multiple arguments supporting it, presenting different kinds of evidence that all contribute to the singular, main idea presented in your thesis.

Review your evidence and identify these different arguments, then organize the evidence into categories based on the argument they support. These ideas and evidence will become the body paragraphs of your essay.

For example, if you were writing about Roderick and Madeline as in the example above, you would pull evidence from the text, such as the narrator’s realization of their relationship as twins; examples where the narrator’s tone of voice shifts when discussing their relationship; imagery, like the sounds Roderick hears as Madeline tries to escape; and Poe’s tendency to use doubles and twins in his other writings to create the same spooky effect. All of these are separate strains of the same argument, and can be clearly organized into sections of an outline.

Step 7: Write Your Introduction

Your introduction serves a few very important purposes that essentially set the scene for the reader:

- Establish context. Sure, your reader has probably read the work. But you still want to remind them of the scene, characters, or elements you’ll be discussing.

- Present your thesis statement. Your thesis statement is the backbone of your analytical paper. You need to present it clearly at the outset so that the reader understands what every argument you make is aimed at.

- Offer a mini-outline. While you don’t want to show all your cards just yet, you do want to preview some of the evidence you’ll be using to support your thesis so that the reader has a roadmap of where they’re going.

Step 8: Write Your Body Paragraphs

Thanks to steps one through seven, you’ve already set yourself up for success. You have clearly outlined arguments and evidence to support them. Now it’s time to translate those into authoritative and confident prose.

When presenting each idea, begin with a topic sentence that encapsulates the argument you’re about to make (sort of like a mini-thesis statement). Then present your evidence and explanations of that evidence that contribute to that argument. Present enough material to prove your point, but don’t feel like you necessarily have to point out every single instance in the text where this element takes place. For example, if you’re highlighting a symbol that repeats throughout the narrative, choose two or three passages where it is used most effectively, rather than trying to squeeze in all ten times it appears.

While you should have clearly defined arguments, the essay should still move logically and fluidly from one argument to the next. Try to avoid choppy paragraphs that feel disjointed; every idea and argument should feel connected to the last, and, as a group, connected to your thesis. A great way to connect the ideas from one paragraph to the next is with transition words and phrases, such as:

- Furthermore

- In addition

- On the other hand

- Conversely

Step 9: Write Your Conclusion

Your conclusion is more than a summary of your essay's parts, but it’s also not a place to present brand new ideas not already discussed in your essay. Instead, your conclusion should return to your thesis (without repeating it verbatim) and point to why this all matters. If writing about the siblings in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” for example, you could point out that the utilization of twins and doubles is a common literary element of Poe’s work that contributes to the definitive eeriness of Gothic literature.

While you might speak to larger ideas in your conclusion, be wary of getting too macro. Your conclusion should still be supported by all of the ideas that preceded it.

Step 10: Revise, Revise, Revise

Of course you should proofread your literary analysis essay before you turn it in. But you should also edit the content to make sure every piece of evidence and every explanation directly supports your thesis as effectively and efficiently as possible.

Sometimes, this might mean actually adapting your thesis a bit to the rest of your essay. At other times, it means removing redundant examples or paraphrasing quotations. Make sure every sentence is valuable, and remove those that aren’t.

Other Resources for Literary Analysis

With these skills and suggestions, you’re well on your way to practicing and writing literary analysis. But if you don’t have a firm grasp on the concepts discussed above—such as literary devices or even the content of the text you’re analyzing—it will still feel difficult to produce insightful analysis.

If you’d like to sharpen the tools in your literature toolbox, there are plenty of other resources to help you do so:

- Check out our expansive library of Literary Devices . These could provide you with a deeper understanding of the basic devices discussed above or introduce you to new concepts sure to impress your professors ( anagnorisis , anyone?).

- This Academic Citation Resource Guide ensures you properly cite any work you reference in your analytical essay.

- Our English Homework Help Guide will point you to dozens of resources that can help you perform analysis, from critical reading strategies to poetry helpers.

- This Grammar Education Resource Guide will direct you to plenty of resources to refine your grammar and writing (definitely important for getting an A+ on that paper).

Of course, you should know the text inside and out before you begin writing your analysis. In order to develop a true understanding of the work, read through its corresponding SuperSummary study guide . Doing so will help you truly comprehend the plot, as well as provide some inspirational ideas for your analysis.

How To Write an Analytical Essay

If you enjoy exploring topics deeply and thinking creatively, analytical essays could be perfect for you. They involve thorough analysis and clever writing techniques to gain fresh perspectives and deepen your understanding of the subject. In this article, our expert research paper writer will explain what an analytical essay is, how to structure it effectively and provide practical examples. This guide covers all the essentials for your writing success!

What Is an Analytical Essay

An analytical essay involves analyzing something, such as a book, movie, or idea. It relies on evidence from the text to logically support arguments, avoiding emotional appeals or personal stories. Unlike persuasive essays, which argue for a specific viewpoint, a good analytical essay explores all aspects of the topic, considering different perspectives, dissecting arguments, and evaluating evidence carefully. Ultimately, you'll need to present your own stance based on your analysis, synthesize findings, and decide whether you agree with the conclusions or have your own interpretation.

Wondering How to Impress Your Professor with Your Essay?

Let our writers craft you a winning essay, no matter the subject, field, type, or length!

How to Structure an Analytical Essay

Crafting an excellent paper starts with clear organization and structuring of arguments. An analytical essay structure follows a simple outline: introduction, body, and conclusion.

Introduction: Begin by grabbing the reader's attention and stating the topic clearly. Provide background information, state the purpose of the paper, and hint at the arguments you'll make. The opening sentence should be engaging, such as a surprising fact or a thought-provoking question. Then, present your thesis, summarizing your stance in the essay.

Body Paragraphs: Each paragraph starts with a clear topic sentence guiding the reader and presents evidence supporting the thesis. Focus on one issue per paragraph and briefly restate the main point at the end to transition smoothly to the next one. This ensures clarity and coherence in your argument.

Conclusion: Restate the thesis, summarize key points from the body paragraphs, and offer insights on the significance of the analysis. Provide your thoughts on the topic's importance and how your analysis contributes to it, leaving a lasting impression on the reader.

Meanwhile, you might also be interested in how to write a reflection paper , so check out the article for more information!

How to Write an Analytical Essay in 6 Simple Steps

Once you've got a handle on the structure, you can make writing easier by following some steps. Preparing ahead of time can make the process smoother and improve your essay's flow. Here are some helpful tips from our experts. And if you need it, you can always request our experts to write my essay for me , and we'll handle it promptly.

.webp)

Step 1: Decide on Your Stance

Before diving into writing, it's crucial to establish your stance on the topic. Let's say you're going to write an analytical essay example about the benefits and drawbacks of remote work. Before you start writing, you need to decide what your opinion or viewpoint is on this topic.

- Do you think remote work offers flexibility and improved work-life balance for employees?

- Or maybe you believe it can lead to feelings of isolation and decreased productivity?

Once you've determined your stance on remote work, it's essential to consider the evidence and arguments supporting your position. Are there statistics or studies that back up your viewpoint? For example, if you believe remote work improves productivity, you might cite research showing increased output among remote workers. On the other hand, if you think it leads to isolation, you could reference surveys or testimonials highlighting the challenges of remote collaboration. Your opinion will shape how you write your essay, so take some time to think about what you believe about remote work before you start writing.

Step 2: Write Your Thesis Statement

Once you've figured out what you think about the topic, it's time to write your thesis statement. This statement is like the main idea or argument of your essay.

If you believe that remote work offers significant benefits, your thesis statement might be: 'Remote work presents an opportunity for increased flexibility and work-life balance, benefiting employees and employers alike in today's interconnected world.'

Alternatively, if you believe that remote work has notable drawbacks, your thesis statement might be: 'While remote work offers flexibility, it can also lead to feelings of isolation and challenges in collaboration, necessitating a balanced approach to its implementation.'

Your thesis statement guides the rest of your analytical essay, so make sure it clearly expresses your viewpoint on the benefits and drawbacks of remote work.

Step 3: Write Topic Sentences

After you have your thesis statement about the benefits and drawbacks of remote work, you need to come up with topic sentences for each paragraph while writing an analytical essay. These sentences introduce the main point of each paragraph and help to structure your essay.

Let's say your first paragraph is about the benefits of remote work. Your topic sentence might be: 'Remote work offers employees increased flexibility and autonomy, enabling them to better manage their work-life balance.'

For the next paragraph discussing the drawbacks of remote work, your topic sentence could be: 'However, remote work can also lead to feelings of isolation and difficulties in communication and collaboration with colleagues.'

And for the paragraph about potential solutions to the challenges of remote work, your topic sentence might be: 'To mitigate the drawbacks of remote work, companies can implement strategies such as regular check-ins, virtual team-building activities, and flexible work arrangements.'

Each topic sentence should relate back to your thesis statement about the benefits and drawbacks of remote work and provide a clear focus for the paragraph that follows.

Step 4: Create an Outline

Now that you have your thesis statement and topic sentences, it's time to create an analytical essay outline to ensure your essay flows logically. Here's an outline prepared by our analytical essay writer based on the example of discussing the benefits and drawbacks of remote work:

Step 5: Write Your First Draft

Now that you have your outline, it's time to start writing your first draft. Begin by expanding upon each point in your outline, making sure to connect your ideas smoothly and logically. Don't worry too much about perfection at this stage; the goal is to get your ideas down on paper. You can always revise and polish your draft later.

As you write, keep referring back to your thesis statement to ensure that your arguments align with your main argument. Additionally, make sure each paragraph flows naturally into the next, maintaining coherence throughout your essay.

Once you've completed your first draft, take a break and then come back to review and revise it. Look for areas where you can strengthen your arguments, clarify your points, and improve the overall structure and flow of your essay.

Remember, writing is a process, and it's okay to go through multiple drafts before you're satisfied with the final result. Take your time and be patient with yourself as you work towards creating a well-crafted essay on the benefits and drawbacks of remote work.

Step 6: Revise and Proofread

Once you've completed your first draft, it's essential to revise and proofread your essay to ensure clarity, coherence, and correctness. Here's how to approach this step:

- Check if your ideas make sense and if they support your main point.

- Make sure your writing style stays the same and your format follows the rules.

- Double-check your facts and make sure you've covered everything important.

- Cut out any extra words and make your sentences clear and short.

- Look for mistakes in spelling and grammar.

- Ask someone to read your essay and give you feedback.

What is the Purpose of an Analytical Essay?

Analytical essays aim to analyze texts or topics, presenting a clear argument. They deepen understanding by evaluating evidence and uncovering underlying meanings. These essays promote critical thinking, challenging readers to consider different viewpoints.

They're also great for improving critical thinking skills. By breaking down complex ideas and presenting them clearly, they encourage readers to think for themselves and reach their own conclusions.

This type of essay also adds to academic discussions by offering fresh insights. By analyzing existing research and literature, they bring new perspectives or shine a light on overlooked parts of a topic. This keeps academic conversations lively and encourages more exploration in the field.

Analytical Essay Examples

Check out our essay samples to see theory in action. Crafted by our dissertation services , they show how analytical thinking applies to real situations, helping you understand concepts better.

With our tips on how to write an analytical essay, you're ready to boost your writing skills and craft essays that captivate your audience. With practice, you'll become a pro at analytical writing, ready to tackle any topic with confidence. And, if you need help to buy essay online , just drop us a line saying ' do my homework for me ' and we'll jump right in!

Do Analytical Essays Tend to Intimidate You?

Give us your assignment to uncover a deeper understanding of your chosen analytical essay topic!

How to Write an Analytical Essay?

What is an analytical essay.

Daniel Parker

is a seasoned educational writer focusing on scholarship guidance, research papers, and various forms of academic essays including reflective and narrative essays. His expertise also extends to detailed case studies. A scholar with a background in English Literature and Education, Daniel’s work on EssayPro blog aims to support students in achieving academic excellence and securing scholarships. His hobbies include reading classic literature and participating in academic forums.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

Related Articles

.webp)

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)