- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

10: Vitamin C Analysis (Experiment)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 95879

- Santa Monica College

- To standardize a \(\ce{KIO3}\) solution using a redox titration.

- To analyze an unknown and commercial product for vitamin C content via titration.

- To compare your results for the commercial product with those published on the label.

Note: You will need to bring a powdered or liquid drink, health product, fruit samples, or other commercial sample to lab for vitamin C analysis. You will need enough to make 500 mL of sample for use in 3-5 titrations. Be sure the product you select actually contains vitamin C (as listed on the label or in a text or website) and be sure to save the label or reference for comparison to your final results. Be careful to only select products where the actual vitamin C content in mg or percent of RDA (recommended daily allowance) is listed. The best samples are lightly colored and/or easily pulverized.

The two reactions we will use in this experiment are:

\[\ce{KIO3(aq) + 6 H+(aq) +5 I- (aq)→ 3 I2(aq) + 3 H2O(l) + K+(aq) } \quad \quad \text{generation of }\ce{I2} \label{1}\]

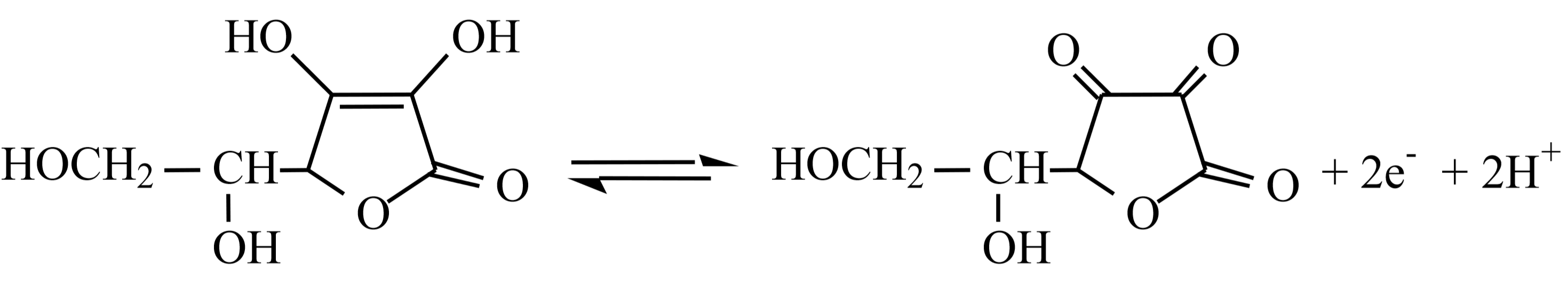

\[\underbrace{\ce{C6H8O6(aq)}}_{\text{vitamin C(ascorbic acid)}}\ce{ + I2(aq) →C6H6O6(aq) +2 I- (aq) + 2 H+(aq) } \quad \quad \text{oxidation of vitamin C}\label{2}\]

Reaction \ref{1} generates aqueous iodine, \(\ce{I2}\) ( aq ). This is then used to oxidize vitamin C (ascorbic acid, \(\ce{C6H8O6}\)) in reaction \ref{2}. Both of these reactions require acidic conditions and so dilute hydrochloric acid, \(\ce{HCl}\) ( aq ), will be added to the reaction mixture. Reaction one also requires a source of dissolved iodide ions, \(\ce{I^-}\) ( aq ). This will be provided by adding solid potassium iodide, \(\ce{KI}\) ( s ), to the reaction mixture.

This is a redox titration. The two relevant half reactions for reaction \ref{2} above are:

Reduction half reaction for Iodine at pH 5:

\[\ce{I2 +2e^{⎯} → 2I^{⎯}}\]

Oxidation half reaction for vitamin C (\(\ce{C6H8O6}\)) at pH 5:

A few drops of starch solution will be added to help determine the titration endpoint. When the vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is completely oxidized, the iodine, \(\ce{I2}\) ( aq ), will begin to build up and will react with the iodide ions, \(\ce{I^-}\) ( aq ), already present to form a highly colored blue \(\ce{I3^-}\)-starch complex, indicating the endpoint of our titration.

Vitamin C: An Important Chemical Substance

Vitamin C , known chemically as ascorbic acid , is an important component of a healthy diet. The history of Vitamin C revolves around the history of the human disease scurvy, probably the first human illness to be recognized as a deficiency disease. Its symptoms include exhaustion, massive hemorrhaging of flesh and gums, general weakness and diarrhea. Resultant death was common. Scurvy is a disease unique to guinea pigs, various primates, and humans. All other animal species have an enzyme which catalyzes the oxidation of L- gluconactone to L-ascorbic acid, allowing them to synthesize Vitamin C in amounts adequate for metabolic needs.

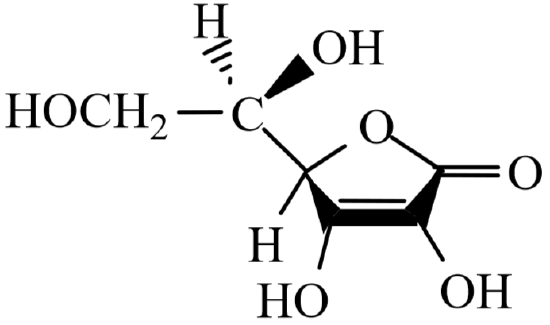

L-Ascorbic Acid -- Vitamin C

As early as 1536, Jacques Cartier, a French explorer, reported the miraculous curative effects of infusions of pine bark and needles used by Native Americans. These items are now known to be good sources of ascorbic acid. However, some 400 years were to pass before Vitamin C was isolated, characterized, and synthesized. In the late 1700's, the British Navy ordered the use of limes on ships to prevent scurvy. This practice was for many years considered to be quackery by the merchant marines, and the Navy sailors became known as “Limeys”. At that time scurvy aboard sailing vessels was a serious problem with often up to 50% of the crew dying from scurvy on long voyages.

The RDA ( Recommended Daily Allowance ) for Vitamin C put forward by the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Research Counsel is 60 mg/day for adults. It is recommended that pregnant women consume an additional 20 mg/day. Lactating women are encouraged to take an additional 40 mg/day in order to assure an adequate supply of Vitamin C in breast milk. Medical research shows that 10 mg/day of Vitamin C will prevent scurvy in adults. There has been much controversy over speculation that Vitamin C intake should be much higher than the RDA for the prevention of colds and flu. Linus Pauling, winner of both a Nobel Prize in Chemistry and the Nobel Peace Prize, has argued in his book, Vitamin C and the Common Cold , that humans should be consuming around 500 mg of Vitamin C a day (considered by many doctors to be an excessive amount) to help ward off the common cold and prevent cancer.

Vitamin C is a six carbon chain, closely related chemically to glucose. It was first isolated in 1928 by the Hungarian-born scientist Szent-Gyorgi and structurally characterized by Haworth in 1933. In 1934, Rechstein worked out a simple, inexpensive, four-step process for synthesizing ascorbic acid from glucose. This method has been used for commercial synthesis of Vitamin C. Vitamin C occurs naturally primarily in fresh fruits and vegetables.

Table 1: Vitamin C content of some foodstuffs

From Roberts, Hollenberg, and Postman, General Chemistry in the Laboratory .

Work in groups of three, dividing the work into three parts (standardization, unknown analysis, and food products) among your group members and then compare data if you are to finish in one period. Work carefully: your grade for this experiment depends on the accuracy and precision of each of your final results.

Materials and Equipment

You will need the following additional equipment for this experiment: 3 Burets, 1 Mortar and pestle, 1 Buret stand

Avoid contact with iodine solutions, as they will stain your skin. Wear safety glasses at all times during the experiment.

WASTE DISPOSAL : You may pour the blue colored titrated solutions into the sink. However, all unused \(\ce{KIO3}\) (after finishing parts A-C) must go in a waste container for disposal. This applies to all three parts of the experiment.

Proper Titration Techniques

Using a Buret

Proper use of a buret is critical to performing accurate titrations. Your instructor will demonstrate the techniques described here.

- Rinsing: Always rinse a buret (including the tip) before filling it with a new solution. You should rinse the buret first with deionized water, and then twice with approximately 10-mL aliquots of the solution you will be using in the buret. Be sure to swirl the solution to rinse all surfaces. If you are using an acid or base solution be careful to avoid spilling the solution on hands or clothing.

- Filling: Mount the buret on a buret stand. Be sure that the tip fits snuggly into the buret and is pressed all the way in. If the tip is excessively loose, exchange it for a tighter fitting one. Using a funnel rinsed in the same manner as the buret, fill the buret with the titrant to just below the 0.00 mL mark. There is no need to fill the buret to exactly 0.00 mL since you will use the difference between the ending and starting volumes to determine the amount delivered. When the buret is full, remove the funnel as drops remaining in or around the funnel can creep down and alter your measured volume. If you overfill the buret, drain a small amount into an empty beaker. Do not re-use this "extra" solution as it may have been contaminated by the beaker or diluted slightly by any water present in the beaker. Always pour fresh solution into the buret.

- Removing Air Bubbles: Often air bubbles will be trapped in the tip of a newly filled buret. These can be difficult to see and troublesome as they alter the measured volume when they escape. To remove air bubbles hold the buret over an open beaker and open the stopcock fully to allow solution to flow out of the buret. Your instructor will demonstrate this technique. Refill the buret as necessary.

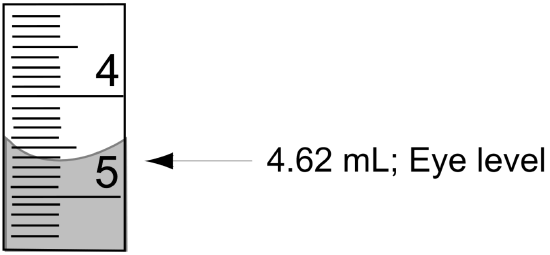

- Reading the Buret: You should always read the volume in a buret from the bottom of the meniscus viewed at eye level (see Figure 1). A black or white card held up behind the buret helps with making this reading. Burets are accurate to ±0.02 mL and all readings should be recorded to two decimal places. Be sure to record both the starting and ending volumes when performing a titration. The difference is the volume delivered.

Figure 1: Reading a Buret

Good Titration Techniques

Throughout your scientific careers you will probably be expected to perform titrations; it is important that you learn proper technique. In performing a titration generally an indicator that changes color is added to a solution to be titrated (although modern instruments can now perform titrations automatically by spectroscopically monitoring the absorbance). Add titrant from the buret dropwise , swirling between drops to determine if a color change has occurred. Only if you know the approximate end-point of a titration should you add titrant faster, but when you come within a few milliliters of the endpoint you should begin to slow down and add titrant dropwise.

As you become proficient in performing titrations you will get a "feeling" for how much to open the stopcock to deliver just one drop of titrant. Some people become so proficient that they can titrate virtually "automatically" by allowing the titrant to drip out of the buret dropwise while keeping a hand on the stopcock, and swirling the solution with the other hand. If you do this, be sure that the rate at which drops are dispensed is slow enough that you can stop the flow before the next drop forms! Overshooting an end-point by even one drop is often cause for having to repeat an entire titration. Generally, this will cost you more time than you will gain from a slightly faster droping rate.

Refill the buret between titrations so you won’t go below the last mark. If a titration requires more than the full volume of the buret, you should either use a larger buret or a more concentrated titrant. Refilling the buret in the middle of a trial introduces more error than is generally acceptable for analytical work.

Set-up and Preparation of Equipment

- Clean and rinse a large 600-mL beaker using deionized water. Label this beaker “standard \(\ce{KIO3}\) solution.”

- From the large stock bottles of ~0.01 M \(\ce{KIO3}\) obtain about 600 mL of \(\ce{KIO3}\) solution. This should be enough \(\ce{KIO3}\) for your group for all three parts of the experiment including rinsings. The reason for collecting one beaker of stock is there is no guarantee that different batches of \(\ce{KIO3}\) from the stockroom will have the same exact molarity. By having one beaker of stock you ensure that all your trials come from the same solution. (If you run out of stock or spill this solution accidentally you will need to repeat part A on the new solution).

- Clean and rinse three burets once with deionized water and then twice with small (5-10 ml) aliquots of standard \(\ce{KIO3}\) from your large beaker. Pour the rinsings into a waste beaker.

- Fill each of the burets (one for each part of the experiment) with \(\ce{KIO3}\) from your beaker. Remove any air bubbles from the tips. The starting volumes in each of the burets should be between 0.00 mL and 2.00 mL. If you use a funnel to fill the burets be sure it is cleaned and rinsed in the same way as the burets and removed from the buret before you make any readings to avoid dripping from the funnel into the buret.

Each of the following parts should be performed simultaneously by different members of your group. You do not have enough time to do these sequentially and finish in one lab period.

Part A: Standardization of your \(\ce{KIO3}\) solution

The \(\ce{KIO3}\) solution has an approximate concentration of about ~0.01 M. You will need to determine exactly what the molarity is to three significant figures. Your final calculated results for each trial of this experiment should differ by less than ± 0.0005 M. Any trials outside this range should be repeated. You will need to calculate in advance how many grams of pure Vitamin C powder (ascorbic acid, \(\ce{C6H8O6}\)) you will need to do this standardization (this is part of your prelaboratory exercise). Remember that your buret holds a maximum of 50.00 mL of solution and ideally you would like to use between 25-35 mL of solution for each titration (enough to get an accurate measurement, but not more than the buret holds).

- Calculate the approximate mass of ascorbic acid you will need and have your instructor initial your calculations on the data sheet.

- Weigh out approximately this amount of ascorbic acid directly into a 250-mL Erlenmeyer flask. Do not use another container to transfer the ascorbic acid as any loss would result in a serious systematic error. Record the mass added in each trial to three decimal places in your data table. It is not necessary that you weigh out the exact mass you calculated, so long as you record the actual mass of ascorbic acid added in each trial for your final calculations.

- Dissolve the solid ascorbic acid in 50-100 mL of deionized water in an Erlenmeyer flask.

- Add approximately 0.5-0.6 g of \(\ce{KI}\), 5-6 mL of 1 M \(\ce{HCl}\), and 3-4 drops of 0.5% starch solution to the flask. Swirl to thoroughly mix reagents.

- Begin your titration. As the \(\ce{KIO3}\) solution is added, you will see a dark blue (or sometimes yellow) color start to form as the endpoint is approached. While adding the \(\ce{KIO3}\) swirl the flask to remove the color. The endpoint occurs when the dark blue color does not fade after 20 seconds of swirling.

- Calculate the molarity of this sample. Repeat the procedure until you have three trials where your final calculated molarities differ by less than ± 0.0005 M.

Part B: Vitamin C Unknown (internal control standard)

- Obtain two Vitamin C tablets containing an unknown quantity of Vitamin C from your instructor.

- Weigh each tablet and determine the average mass of a single tablet.

- Grind the tablets into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle.

- Weigh out approximately 0.20-0.25 grams of the powdered unknown directly into a 250-mL Erlenmeyer flask. Do not use another container to transfer the sample as any loss would result in a serious systematic error. Record the mass added in each trial to three decimal places in your data table.

- Dissolve the sample in about 100 mL of deionized water and swirl well. Note that not all of the tablet may dissolve as commercial vitamin pills often use calcium carbonate (which is insoluble in water) as a solid binder.

- Add approximately 0.5-0.6 g of \(\ce{KI}\), 5-6 mL of 1 M \(\ce{HCl}\), and 2-3 drops of 0.5% starch solution to the flask before beginning your titration. Swirl to mix.

- Perform two more trials. If the first titration requires less than 20 mL of \(\ce{KIO3}\), increase the mass of unknown slightly in subsequent trials.

- Calculate milligrams of ascorbic acid per gram of sample and using the average mass of a tablet, determine the number of milligrams of Vitamin C contained in each tablet. Be sure to use the average molarity for \(\ce{KIO3}\) determined in Part A for these calculations. Your results should be accurate to at least three significant figures. Repeat any trials that seem to differ significantly from your average.

Part C: Fruit juices, foods, health-products, and powdered drink mixes

Solids samples

- Pulverize solid samples (such as vitamin pills, cereals, etc.) with a mortar and pestle. Powdered samples (such as drink mixes) may be used directly.

- Weigh out enough powdered sample, so that there will be about 100 mg of ascorbic acid (according to the percentage of the RDA or mg/serving listed by the manufacturer) in each trial.

- Add the sample to a 250-mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 50-100 mL of water. (Note: If your sample is highly colored, you might want to dissolve the KI in the water before adding the mix, so that you can be sure it dissolves).

- Begin your titration. As the \(\ce{KIO3}\) solution is added, you will see a dark blue (or sometimes yellow or black depending on the color of your sample) color start to form as the endpoint is approached. While adding the \(\ce{KIO3}\) swirl the flask to remove the color. The endpoint occurs when the dark color does not fade after 20 seconds of swirling.

- Calculate the milligrams of ascorbic acid per gram of sample. Be sure to use the average molarity determined for the \(\ce{KIO3}\) in Part A for these calculations. Your results should be accurate to at least three significant figures. Repeat any trials that seem to differ significantly from your average.

Liquid samples

- If you are using a pulpy juice, strain out the majority of the pulp using a cloth or filter.

- Using a graduated cylinder, measure out at least 100 mL of your liquid sample. Record the volume to three significant figures (you will calculate the mass of ascorbic acid per milliliter of juice).

- Add this liquid to an Erlenmeyer flask.

- Begin your titration. As the \(\ce{KIO3}\) solution is added, you will see a dark blue (or sometimes yellow or black depending on the color of your sample) color start to form as the endpoint is approached. While adding the \(\ce{KIO3}\) swirl the flask to remove the color. The endpoint occurs when the dark color does not fade after 20 seconds of swirling. With juices it sometimes takes a little longer for the blue color to fade, in which case the endpoint is where the color is permanent.

- Perform two more trials. If the first titration requires less than 20 mL of \(\ce{KIO3}\), increase the volume of unknown slightly in subsequent trials.

- Calculate the milligrams of ascorbic acid per milliliter of juice. Be sure to use the average molarity determined for the \(\ce{KIO3}\) in Part A for these calculations. Your results should be accurate to at least three significant figures. Repeat any trials that seem to differ significantly from your average.

Pre-laboratory Assignment: Vitamin C Analysis

- If an average lemon yields 40 mL of juice, and the juice contains 50 mg of Vitamin C per 100 mL of juice, how many lemons would one need to eat to consume the daily dose of Vitamin C recomended by Linus Pauling? Show all work.

- Why are \(\ce{HCl}\), \(\ce{KI}\), and starch solution added to each of our flasks before titrating in this experiment? What is the function of each?

- \(\ce{HCl}\):

- \(\ce{KI}\):

- A label states that a certain cold remedy contains 200% of the US Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) of Vitamin C per serving, and that a single serving is one teaspoon (about 5 mL). Calculate the number of mg of Vitamin C per serving and per mL for this product. Show all work.

- Based on the balanced reactions \ref{1} and \ref{2} for the titration of Vitamin C, what is the mole ratio of \(\ce{KIO3}\) to Vitamin C from the combined equations?

_______ moles \(\ce{KIO3}\) : _______ moles Vitamin C (ascorbic acid)

- Assuming that you want to use about 35 mL of \(\ce{KIO3}\) for your standardization titration in part A, about how many grams of ascorbic acid should you use? (you will need this calculation to start the lab). Show all work.

Hint: you will need to use the approximate \(\ce{KIO3}\) molarity given in the lab instructions and the mole ratio you determined in the prior problem.

Lab Report: Vitamin C Analysis

Mass of ascorbic acid to be used for standardization of ~0.01 M \(\ce{KIO3}\): __________ g ______Instructor’s initials

Supporting calculations:

Standardization Titration Data:

*All values should be with in ±0.0005 M of the average; trials outside this range should be crossed out and a fourth trial done as a replacement. Express your values to the correct number of significant figures. Show all your calculations on the back of this sheet.

- Average Molarity of \(\ce{KIO3}\):

"Internal Control Sample" (unknown) code:

Mass of Tablet 1:

Mass of Tablet 2:

Average mass:

Control Standard (Unknown) Titration Data:

* Express your values to the correct number of significant figures. Show all your calculations on the back of this sheet.

- ____________mg/g

- ____________mg/tablet

Name of Sample Used: ________________________________________________________

- Briefly describe the sample you chose to examine and how you prepared it for analysis. You may continue on the back if necessary:

Part C Titration Data:

*Express your values to the correct number of significant figures. Show all your calculations on the back of this sheet.

Average ascorbic acid :

- What is the concentration of Vitamin C listed on the packaging by the manufacturer or given in the reference source? This can be given in units of %RDA, mg/g, mg/mL, mg/serving, or %RDA per serving. Be sure to include the exact units cited.

- Manufacturer’s claim: ____________________________ (value and units)

- Serving Size (if applicable): ________________________ (value and units)

____________ mg / g or mL

- If your reference comes from a text book or the internet give the citation below. If it comes from a product label please remove the label and attach it to this report.

- Using your average milligrams of Vitamin C per gram or milliliter of product from part C as the "correct" value, determine the percent error in the manufacturer or text’s claim (show calculations)?

- What can you conclude about the labeling of this product or reference value? How do you account for any discrepancies? Does the manufacturer or reference overstate or understate the amount of Vitamin C in the product? If so, why might they do this? Explain below. Use the back of this sheet if necessary.

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Vitamin C - an Update on Current Uses and Functions

Introductory Chapter: Vitamin C

Submitted: 03 December 2018 Published: 03 January 2019

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.83392

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

Vitamin C - an Update on Current Uses and Functions

Edited by Jean Guy LeBlanc

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

1,162 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

Author Information

Jean guy leblanc *.

- CERELA-CONICET, San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentina

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected], [email protected]

1. Vitamins

The word vitamin was originally coined to describe amines that are essential for life. It is now known that although not all vitamins are amines, there are organic micronutrients that mean that they must be consumed in small quantities for adequate growth and are required in numerous metabolic reactions to maintain homeostasis. There are 13 vitamins that are recognized by all researchers, and these can be classified as either being soluble in fats (fat soluble) (including vitamins A (retinols and carotenoids), D (cholecalciferol), E (tocopherols and tocotrienols), and K (quinones)) or soluble in water (water soluble) (including vitamin C (ascorbic acid) and the B group vitamins). B group vitamins include the following: vitamin B1 (thiamine), vitamin B2 (riboflavin), vitamin B3 (niacin), vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid), vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), vitamin B7 (biotin), vitamin B9 (folic acid or folate), and vitamin B12 (cobalamins).

2. Vitamin deficiencies

Although all 13 vitamins are present in a wide variety of foods, deficiencies are still very common in all parts of the world. There is no magic food that contains all the vitamins; the only way to avoid deficiencies is to consume a variety of foods, which are the bases of all the nutritional guidelines, or consume dietary supplements. In addition to malnutrition, certain diseases and treatments have been shown to affect vitamin absorption or bioavailability. Furthermore, pregnant women and children have a greater need for vitamins because of their increased metabolism during cell replication.

3. Vitamin C

Vitamin C, also known as ascorbic acid, is mainly present in fruits and vegetables; citrus fruits, tomatoes and potatoes are the principal exogenous source of this vitamin. The consumption of such foods is important since the human body does not have the ability to produce this essential micronutrient. Because it is water soluble, it can easily be lost by cooking and long-term storage; fortunately, most fruits and vegetables that contain large amounts of vitamin C are consumed fresh without cooking. However, it is well known that most people do not consume the recommended five servings of fruits and vegetables that would be necessary for them to fulfill their daily recommended intake of vitamin C that is around 200 mg. Because of this problem, it is now common that ascorbic acid be used as a dietary supplement, which can easily be added to foods or consumed directly in capsules or part of multivitamin preparations.

Even though it is almost unheard of that people still can be affected by scurvy today, which is directly caused by vitamin C deficiency, its early symptoms are very common. These include fatigue, inflammatory problems (especially of the gums), depression, joint pain, and anemia. Besides an inadequate ingestion of the vitamin, other causes have been linked to vitamin C deficiency such as smoking (direct and passive), malnutrition (inadequate ingestion of eating unbalanced diets), certain drugs, and malabsorption caused by certain diseases.

The consumption of vitamin C supplements are nowadays very common, not only to prevent deficiencies but also to ensure the wide range of beneficial health effects that have been reported to be associated with the consumption of this vitamin. These include having an active role in immunity, reason for which is that many consume ascorbic acid when they have a common cold, and also because it has been stated that it can play a role in cancer (in its prevention and treatment), cardiovascular diseases, and age-related diseases such a cataracts, among others. Vitamin C is also the most commonly used antioxidant substance in foods because of its safety. This property has made it the object of numerous studies where it is used as adjunctive treatments in many bacterial and virus infections and cancer treatments, another reason that has made it the vitamin of choice by consumers to improve their general health.

4. Conclusions

Even though the role of vitamin C has been known since the early 1930s and a series of interesting studies have been performed in the 1970s, only recently researchers have been actively studying and demonstrating its role and function in the treatment and prevention of many diseases. These studies will be the key to providing the scientific basis that explains why this simple but important vitamin possesses such a wide range of positive biological activities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas and the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica for their financial support.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interests exists with the publication of this chapter.

© 2019 The Author(s). Licensee IntechOpen. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Continue reading from the same book

Published: 10 May 2019

By Nermin M. Yussif

3094 downloads

By Fadime Eryılmaz Pehlivan

1861 downloads

By Philippe Humbert, Loriane Louvrier, Philippe Saas ...

2276 downloads

Log In | Join AACT | Renew Membership

AACT Member-Only Content

You have to be an AACT member to access this content, but good news: anyone can join!

- AACT member benefits »

- Forgot User Name or Password?

Save Your Favorite AACT Resources! ×

Log in or join now to start building your personalized "My Favorites" page. Easily save all the resources you love by logging in and clicking on the star icon next to any resource title.

Vitamin C Quality Control Mark as Favorite (10 Favorites)

LESSON PLAN in Concentration , Reduction , Redox Reaction , Accuracy , Dimensional Analysis , Measurements , Significant Figures , Titrations , Indicators , Oxidation , Error Analysis , Chemical Technical Professionals . Last updated July 11, 2023.

In this lesson, students will learn about a career in the skilled technical workforce, develop skills utilized in a quality control lab, and obtain data that may not have a clear “right answer.” For example, though many over-the-counter medications and vitamins state the amount of active ingredient, any individual tablet may have between 97 to 103% of the stated label claim. In addition, any products past the expiry date may have less due to potential decomposition. Students practice scientific communication by reporting their findings in a professional manner.

Grade Level

High School

NGSS Alignment

This lesson will help prepare your students to meet the performance expectations in the following standards:

- HS-PS1-2 : Construct and revise an explanation for the outcome of a simple chemical reaction based on the outermost electron states of atoms, trends in the periodic table, and knowledge of the patterns of chemical properties.

- HS-PS1-7 : Use mathematical representation to support the claim that atoms, and therefore mass, are conserved during a chemical reaction.

- Using Mathematics and Computational Thinking

- Analyzing and Interpreting Data

- Planning and Carrying Out Investigations

- Engaging in Argument from Evidence

- Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information

By the end of this lesson, students should be able to:

- Explain the role of chemical technicians in a quality control lab.

- Prepare solutions and conduct titrations.

- Analyze titration data and communicate results and quality control recommendations in a technical memo.

Chemistry Topics

This lesson supports students’ understanding of:

- Chemical reactions

- Oxidation-reduction reactions

- Data analysis and significant figures

Teacher Preparation :

- 30-45 minutes to prepare solutions

- 30 minutes to standardize iodine solution

- 30 minutes for the introductory activity on Chemistry and Quality Control (can be assigned as homework as a pre-lab assignment)

- 60-90 minutes for lab activity (depends on whether students complete 2 or more titrations per analysis)

- 100 mL volumetric flask

- 100-mL & 10-mL graduated cylinders

- two 125-mL Erlenmeyer flasks

- 50-mL burette, ring stand and burette clamp

- 1-mL volumetric pipette and pipette bulb

- Deionized or distilled water

- 1000 mg Vitamin C tablets are recommended, see teacher notes for more detail; do not use multivitamins as the other ingredients may interfere with the titration.

- 1% starch solution (3 mL per lab group, see teacher notes for preparation details)

- 2% Iodine-Potassium Iodide Solution (referred to throughout this lesson as “iodine solution;” see teacher notes for preparation and standardization details)

- Ascorbic acid stock solution , about 1 mg/mL (20-30 mL total for teacher standardization, or 10-20 mL per lab group if students standardize iodine solution; see teacher notes)

- Always wear safety goggles when handling chemicals in the lab.

- Iodine solutions may stain, so gloves and lab coat or apron may be worn.

- Students should wash their hands thoroughly before leaving the lab.

- When students complete the lab, instruct them how to clean up their materials and dispose of any chemicals.

- Do not consume lab solutions, even if they are otherwise edible products.

- Food in the lab should be considered a chemical not for consumption.

Teacher Notes

- The National Science Board estimates that there are over 16 million jobs in the Skilled Technical Workforce (STW) that don’t require a 4-year college degree, but require STEM knowledge such as the use of chemicals, application of arithmetic and algebra, and the knowledge of quality control and other techniques for manufacturing goods. This lesson was developed as part of a content writing team to support the ACS Strategic Initiative on Fostering a Skilled Technical Workforce, with the goal of increasing awareness of and appreciation for STW opportunities in the chemistry enterprise at the high school level.

- This lesson plan introduces students to quality control (QC) in pharmaceuticals and nutritional supplements. Students practice using some of the skills needed by chemical technicians, including preparing solutions, conducting chemical analyses, and preparing a report to summarize results.

- Lilly Quality Control Laboratories Help Ensure High Quality Medicines from Eli Lilly and Company

- Chemical Technician Career Video from Career One Stop

- Lab Technician | What I do & how much I make | Part 1 from Khan Academy

- For the lab portion of this lesson, 1000 mg vitamin C tablets are recommended. Lower dose vitamins could be used and would take less time and titrant to analyze, but care should be taken to ensure that amounts are not too small for students to measure or have too few significant figures for meaningful data analysis. Be sure it is not a multivitamin, as other ingredients may interfere with titration data.

- In this lab, ascorbic acid (vitamin C) is directly titrated with iodine (iodimetry). The titrant iodine is reduced and the ascorbic acid analyte is oxidized as shown below. A starch solution is used as an indicator, as it forms a dark blue-black complex with I 2 once all the ascorbic acid is consumed. This color change marks the endpoint of the reaction.

- Generally, titrations should be run in triplicate, but time may limit students to fewer. It is helpful to have students share data (for example, via a shared Google Sheets) to allow more meaningful (and realistic) error analysis.

- For the final report, students can research the recommended daily amounts and upper limits for Vitamin C themselves, or you can provide the following information. While many students may know the problem with too little Vitamin C (scurvy), they may not know that too much Vitamin C can cause diarrhea or stomach cramps, and increase the risk of kidney stones. If time permits, a discussion about the importance of quality control as it pertains to these recommendations could help students further appreciate the relevance and real-world impact of QC careers.

- At the end of the final report, students are asked to submit raw data and full calculations as appendices. You could have them just submit the lab handout for this section, or, to make it more formal, you could have them neatly write or type up their data tables and calculations.

- The scenario can be modified to test fruit juices (see Ballentine, 1941 in “Further reading about techniques” section below). Light-colored juices must be used in order to see the endpoint.

- To increase the challenge for a more advanced class, you could remove the SOP section from the student handout and have the students research methods to measure ascorbic acid and write their own procedure. There are two methods of using iodine to oxidize ascorbic acid (iodometry and iodimetry) that differ only in how the reagents are combined.

- Another option to increase the level of difficulty of this lesson is to remove the guided calculations and have students independently determine how to analyze the results.

Standardization of Iodine Solution with Ascorbic Acid

- You can use 2% Tincture of Iodine Solution from a drug store (which contains 1.8 to 2.2 grams of I 2 /100 mL solution with an approximate molarity of 0.08 M I 2 ), or Lugol solution (1% iodine solution which contains 1 g I 2 /100 mL of solution with an approximate molarity of 0.04 M I 2 ). In either case, it must be standardized relative to ascorbic acid (see below).

- The procedures in the student document assume that time is limited, and that the teacher standardizes the iodine solution in advance and provides the conversion factor to the students. Alternatively, provide the standardization procedures (below) to the class, and each lab group can perform one titration (or more, if time allows) and contribute a data point for a group calibration. This standardization step would be a valuable addition to help students understand another example of the roles and responsibilities of skilled technical workers if time allows.

- Ascorbic acid oxidizes quickly in the presence of oxygen. The standard solution should preferably be prepared on the day of the lab but may be prepared the day before if stored in a brown bottle or a bottle wrapped in aluminum foil and refrigerated. If the teacher is completing the standardization and providing students with a conversion factor, the entire standardization procedure can occur the day before/when the ascorbic acid solution is fresh.

- The 1% starch solution is the indicator that will identify the endpoint of the titration when excess iodine reacts with starch and turns the solution blue-black. The exact concentration is not important, and the solution can be prepared by dissolving 1 g of soluble starch in 100 mL of distilled or deionized water (water should be heated for easier dissolving), or by spraying ironing starch into distilled or deionized water. More detailed instructions are available here .

- Procedure to standardize the iodine solution:

- Using a 100-mL volumetric flask, dissolve 0.10 g of ascorbic acid in distilled or deionized water to prepare a stock solution with a concentration of ~1 mg/mL of solution. Record the exact mass of ascorbic acid used and label the concentration of the stock solution $\ce{{$\frac{mg~asorbic~acid} {100~mL~solution} $}}$. (It should be approximately 100 mg ascorbic acid/100 mL solution.)

- Using a volumetric pipette, transfer 10 mL of the ascorbic acid solution to an Erlenmeyer flask.

- Using the 10-mL graduated cylinder, add 1 mL of 1% starch solution to the ascorbic acid solution in the flask.

- Fill the burette with the iodine solution and record the initial volume to the nearest 0.01 mL (or as appropriate for the particular burettes used).

- Add the iodine solution by drops to the flask, gently swirling to mix, until the dark blue color of the iodine-starch complex persists.

- Record the final volume and determine conversion factor $\ce{{$\frac{mg~asorbic~acid} {100~mL~solution} $}}$ as shown below.

Calculations and Sample Data for Standardization

- Use the most precise balances available for best results.

- Mass of ascorbic acid: 0.103 g ascorbic acid = 103 mg ascorbic acid

- Concentration of ascorbic acid stock solution from step 1: $\ce{{$\frac{103~mg~asorbic~acid} {100~mL~solution} $}}$

- Determine the mass, in mg, of ascorbic acid in 10 mL solution:

Trial 1 & 2:

$\ce{10.0~mL~of~ascorbic~acid~solution * {$\frac{103~mg~ascorbic~acid}{100~mL~solution}$} = 10.3~mg~of~ascorbic~acid}$

- For each trial, determine how many mL of iodine solution needed to react with the mass of ascorbic acid in 10 mL solution.

Trial 1: 3.36 mL reacted with 10.3 mg of ascorbic acid

Trial 2: 3.42 mL reacted with 10.3 mg of ascorbic acid

- Calculate a conversion factor that relates 1 mL of iodine solution to mass of ascorbic acid.

$\ce{{$\frac{10.3~mg~ascorbic~acid}{3.36~mL~solution}$} = {$\frac{3.07~mg~ascorbic~acid}{1.00~mL~solution}$}}$

$\ce{{$\frac{10.3~mg~ascorbic~acid}{3.36~mL~solution}$} = {$\frac{3.01~mg~ascorbic~acid}{1.00~mL~solution}$}}$

Average Conversion Factor: 1 mL iodine solution = 3.04 mg ascorbic acid (provide this value to the students)

- If desired, you can have the students calculate molarities of the solutions instead of mg/mL, but this gravimetric conversion factor is more direct and is more likely to be used in a QC laboratory.

Further reading about techniques

- Ballentine, R. (1941). Determination of Ascorbic Acid in Citrus Fruit Juices. Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, Analytical Edition, 13(2), 89. doi: doi.org/10.1021/i560090a011

- Moore, C. E. (1948). The determination of vitamin C as a means of teaching iodimetry. Journal of Chemical Education, 25(12), 671. doi: doi.org/10.1021/ed025p671

- Cesar R. Silva, J. A. (1999). Ascorbic Acid as a Standard for Iodometric Titrations. Journal of Chemical Education, 76(10), 1421-1422. doi: doi.org/10.1021/ed076p1421

- This resource provides a very useful reference for use and care of burettes.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Cochrane Database Syst Rev

Vitamin C supplementation for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease

Vitamin C is an essential micronutrient and powerful antioxidant. Observational studies have shown an inverse relationship between vitamin C intake and major cardiovascular events and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors. Results from clinical trials are less consistent.

To determine the effectiveness of vitamin C supplementation as a single supplement for the primary prevention of CVD.

Search methods

We searched the following electronic databases on 11 May 2016: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE (Ovid); Embase Classic and Embase (Ovid); Web of Science Core Collection (Thomson Reuters); Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE); Health Technology Assessment Database and Health Economics Evaluations Database in the Cochrane Library. We searched trial registers on 13 April 2016 and reference lists of reviews for further studies. We applied no language restrictions.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials of vitamin C supplementation as a single nutrient supplement lasting at least three months and involving healthy adults or adults at moderate and high risk of CVD were included. The comparison group was no intervention or placebo. The outcomes of interest were CVD clinical events and CVD risk factors.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected trials for inclusion, abstracted the data and assessed the risk of bias.

Main results

We included eight trials with 15,445 participants randomised. The largest trial with 14,641 participants provided data on our primary outcomes. Seven trials reported on CVD risk factors. Three of the eight trials were regarded at high risk of bias for either reporting or attrition bias, most of the 'Risk of bias' domains for the remaining trials were judged as unclear, with the exception of the largest trial where most domains were judged to be at low risk of bias.

The composite endpoint, major CVD events was not different between the vitamin C and placebo group (hazard ratio (HR) 0.99, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.89 to 1.10; 1 study; 14,641 participants; low‐quality evidence) in the Physicians Health Study II over eight years of follow‐up. Similar results were obtained for all‐cause mortality HR 1.07, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.18; 1 study; 14,641 participants; very low‐quality evidence, total myocardial infarction (MI) (fatal and non‐fatal) HR 1.04 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.24); 1 study; 14,641 participants; low‐quality evidence, total stroke (fatal and non‐fatal) HR 0.89 (95% CI 0.74 to 1.07); 1 study; 14,641 participants; low‐quality evidence, CVD mortality HR 1.02 (95% 0.85 to 1.22); 1 study; 14,641 participants; very low‐quality evidence, self‐reported coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)/percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) HR 0.96 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.07); 1 study; 14,641 participants; low‐quality evidence, self‐reported angina HR 0.93 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.03); 1 study; 14,641 participants; low‐quality evidence.

The evidence for the majority of primary outcomes was downgraded (low quality) because of indirectness and imprecision. For all‐cause mortality and CVD mortality, the evidence was very low because more factors affected the directness of the evidence and because of inconsistency.

Four studies did not state sources of funding, two studies declared non‐commercial funding and two studies declared both commercial and non‐commercial funding.

Authors' conclusions

Currently, there is no evidence to suggest that vitamin C supplementation reduces the risk of CVD in healthy participants and those at increased risk of CVD, but current evidence is limited to one trial of middle‐aged and older male physicians from the USA. There is limited low‐ and very low‐quality evidence currently on the effect of vitamin C supplementation and risk of CVD risk factors.

Plain language summary

Vitamin C supplementation to prevent cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are a group of conditions affecting the heart and blood vessels. CVD is a global burden and varies between regions, and this variation has been linked in part to dietary factors. Such factors are important because they can be modified to help with CVD prevention and management.This review assessed the effectiveness of vitamin C supplementation as a single supplement at reducing cardiovascular death, all‐cause death, non‐fatal endpoints (such as heart attacks, strokes and angina) and CVD risk factors in healthy adults and adults at high risk of CVD .

Study characteristics

We searched scientific databases for randomised controlled trials (clinical trials where people are allocated at random to one of two or more treatments) looking at the effects of vitamin C supplementation in healthy adults or those at high risk of developing CVD. We did not include people who already had CVD (e.g. heart attacks and strokes). The evidence is current to May 2016.

Key results

Eight trials fulfilled our inclusion criteria. One large trial looked at the effects of vitamin C supplements on the risk of major CVD events (fatal and non‐fatal) and found no beneficial effects. This trial was however conducted in middle‐aged and older male doctors in the USA and so its not certain that the effects are the same in other groups of people. Seven trials looked at the effects of vitamin C supplements on CVD risk factors. We could not combine these trials as there was lots of missing information and differences between the trials in terms of the participants recruited, the dose of vitamin C and the duration of trials. Overall, there were inconsistent effects of vitamin C supplements on lipid levels and blood pressure and more research is needed. Four of the included studies did not mention sources of funding of the study, two had non‐commercial (grants) funding and two had both commercial (industries) and non‐commercial funding (grants).

Quality of the evidence

The evidence was of low or very low quality for major CVD events (myocardial infraction, stroke, angina and coronary artery bypass grafting), all‐cause mortality and CVD mortality. The evidence was of low quality because it was not applicable to the general population (included only USA male physicians) and limited studies of vitamin C on the prevention of CVD.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

1 Middle‐aged US male physicians and is therefore not highly applicable to the decision context (downgraded by one for indirectness). 2 Small number of included studies (n = 1) for these outcomes (downgraded by one for imprecision). 3 8 years follow‐up (timeframe) may not be sufficient to detect mortality (downgraded by one for indirectness).

Description of the condition

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the number one cause of death globally ( WHO 2011a ). CVDs are the result of disorders of the heart and blood vessels and include cerebrovascular disease, coronary heart disease (CHD), and peripheral arterial disease (PAD) ( WHO 2011b ). In 2008, an estimated 17.3 million people died from CVDs, representing 30% of all global deaths. Of these deaths, an estimated 7.3 million were due to CHD and 6.2 million were due to stroke ( WHO 2011a ). Over 80% of CVD deaths occur in low‐ and middle‐income countries, and the number of CVD deaths is expected to increase to 23.3 million by 2030 ( Mathers 2006 ; WHO 2011a ).

One of the main mechanisms thought to cause CVD is atherosclerosis, in which the arteries become narrowed by plaques or atheromas ( NHS 2012 ). Atherosclerosis can cause CVD when the arteries are completely blocked by a blood clot or when blood flow is restricted by a narrowed artery, limiting the amount of blood and oxygen that can be delivered to organs or tissue ( British Heart Foundation 2012 ). Whilst arteries may naturally become harder and narrower with age, this process may be accelerated by factors such as smoking, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, obesity, a sedentary lifestyle, and ethnicity ( NHS 2012 ). Prevention of CVD by targeting modifiable factors remains a key public health priority. Diet plays a major role in the aetiology of many chronic diseases including CVD, thereby contributing to a significant geographical variability in morbidity and mortality rates across different countries and populations worldwide ( WHO 2003 ). A number of dietary factors have been found to be associated with CVD risk, such as a low consumption of fruit and vegetables ( Begg 2007 ), a high intake of saturated fat ( Siri‐Tarino 2010 ) and a high consumption of salt ( He 2011 ). Dietary factors are important since they can be modified in order to lower CVD risk, making them a prime target for interventions aimed at primary prevention and management of CVD.

Description of the intervention

The intervention examined in this review is vitamin C supplementation as a single ingredient. No limit was placed on the dose or frequency at which vitamin C is taken. Vitamin C (ascorbic acid or ascorbate) is an essential micronutrient that acts as a powerful water‐soluble antioxidant, reducing oxidative stress. It cannot be synthesised in the body and is acquired primarily through the consumption of fruit, vegetables, supplements, fortified beverages, and fortified breakfast or 'ready‐to‐eat' cereals ( Frei 1989 ; WHO 2006 ).

Adults need 40 mg/day of vitamin C, which can be obtained from a healthy diet. Supplementation of vitamin C up to 1000 mg per day is unlikely to cause side effects ( NHS choices 2015 ), whereas larger amounts can cause stomach pain, diarrhoea and flatulence. The pharmacokinetics of vitamin C are complex where the relationship between the amount ingested and plasma and tissue levels is dependent on absorption, tissue transport, renal reabsorption and excretion and rate of utilisation ( Levine 2011 ). The dose concentration curve is sigmoidal with its steep portion between 30 mg and 100 mg of vitamin C daily. At doses greater than 100 mg/day, plasma concentrations reach a plateau between 70 μmol/L and 80 μmol/L. At doses greater than 400 mg/day, further increases in plasma concentrations are minimal ( Levine 2011 ).

Data on the adverse effects of vitamin C supplementation show that these are relatively rare. A survey of 9328 patients who used high‐dose intravenous vitamin C during the preceding 12 months revealed that only 101 had side effects, mostly minor, including lethargy/fatigue in 59 patients, change in mental status in 21 patients and vein irritation/phlebitis in six patients ( Padayatty 2010 ). In a recent meta‐analysis of the effects of vitamin C supplementation, alone and in combination with other agents (such as vitamin E, magnesium, zinc, selenium) on blood pressure ( Juraschek 2012 ), few trials (six of 29) reported adverse effects, however details of these were not provided in the paper.

How the intervention might work

Population‐based observational studies have shown an inverse association between plasma vitamin C concentrations and vitamin C intake with blood pressure ( McCarron 1984 ; Moran 1993 ). Observational studies have also shown an inverse relationship between vitamin C intake and mortality due to CVD ( Jacques 1995 ; Simon 1998 ). However, the results from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have not observed beneficial effects of vitamin C supplementation in the prevention of cardiovascular events ( Cook 2007 ; The Physicians Health Study II ), or mortality outcomes ( Bjelakovic 2007 ).

Low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in the blood may be importantly atherogenic only after oxidative modification, which allows it to be taken up by macrophages in the artery walls. These macrophages, which are attracted to regions where oxidised LDL is being taken up, become loaded with cholesterol (and are then described as "foam cells" in the artery walls), leading to the development of "fatty streaks". Oxidised LDL can also be cytotoxic. Antioxidants such as vitamin C can protect LDL from oxidative modification and may help avoid CVD ( Steinberg 1989 ).

A recent review has summarised the important functions of vitamin C in the vascular bed in support of endothelial cells ( May 2013 ). These functions include increasing the synthesis and deposition of type IV collagen in the basement membrane, stimulating endothelial proliferation, inhibiting apoptosis, scavenging radical species, and sparing endothelial cell‐derived nitric oxide to help modulate blood flow. Endothelial dysfunction is an early sign of inflammatory disease such as atherosclerosis and vitamin C could have a part to play in preventing these early stages.

In the early stages of atherosclerosis, monocytes adhere to the walls of the endothelium, causing the vessel walls to thicken and lose their elasticity. Research has shown that vitamin C supplementation can reduce the rate of monocyte adhesion to the endothelial cell wall. A study looked at the effects of vitamin C (250 mg per day, six weeks duration) in healthy adults with normal and below‐average plasma vitamin C concentration at baseline. Before the study, participants with below average levels of vitamin C had 30% greater monocyte adhesion than normal, putting them at higher risk for atherosclerosis. After six weeks of vitamin C supplementation, the rate of monocyte adhesion fell by 37% ( Woollard 2002 ).

Furthermore, intercellular adhesion molecule‐1 (ICAM‐1) is an inducible surface glycoprotein that mediates the adhesion of monocytes to the endothelium. The researchers went on to demonstrate that the same dose and duration of vitamin C supplementation was able to reduce monocyte ICAM‐1 expression by 50% in participants with below‐average plasma vitamin C concentration ( Rayment 2003 ). Vitamin C supplementation might improve nitric oxide bioactivity ( Huang 2000 ), as well as endothelial function of brachial and coronary arteries, as suggested by short‐term interventions among high‐risk individuals ( Grebe 2006 ; McNulty 2007 ; Silvestro 2002 ; Solzbach 1997 ).

Why it is important to do this review

A systematic review of the effects of individual vitamins and minerals, and multivitamins, on clinical endpoints has been conducted ( Fortmann 2013 ). This review was conducted for the US Task Force for Preventative Services. The authors found two trials of vitamin C supplementation reporting clinical endpoints relevant for CVD prevention, where no effect of the intervention was found. In terms of effects on CVD risk factors, from preliminary searching of the Cochrane Library, we identified five systematic reviews in the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), which assessed the effects of vitamin C supplementation on blood pressure ( Juraschek 2012 ; McRae 2006a ; Ness 1997 ), low‐density lipid (LDL) cholesterol and triglycerides ( McRae 2008 ), and total cholesterol ( McRae 2006b ). Only two of these included only RCTs ( Juraschek 2012 ; McRae 2008 ), the reminder include also non‐randomised experimental studies and observational studies. The first review of RCTs covered both primary and secondary prevention and the effects of vitamin C supplementation alone and in combination with other agents (such as vitamin E, magnesium, zinc, selenium) in trials between two and 26 weeks duration ( Juraschek 2012 ). The authors concluded that vitamin C supplementation reduced systolic and diastolic blood pressure in short‐term trials. The second review concluded that supplementation with at least 500 mg/day of vitamin C, for a minimum of four weeks, can result in a significant decrease in serum LDL cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations. However, the lack of quality assessment and analysis of statistical heterogeneity, and the small sample sizes of the included trials, limit the reliability of the authors' conclusions ( McRae 2008 ).

For the current review we examined evidence from RCTs of vitamin C as a single supplement in the general population and those at moderate to high risk of CVD. This review will update and build on the existing systematic reviews discussed above by assessing vitamin C supplementation (as a single supplement only) in populations relevant for the primary prevention of CVD, in trials of at least three months duration and assessing a wider range of outcomes.

To determine the effectiveness of vitamin C supplementation as a single supplement for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies.

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) including cross‐over trials,studies reported as full‐text, those published as abstract only, and unpublished data were eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

Healthy adults (18 years old or over) from the general population and those at moderate to high risk of CVD (e.g. hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, overweight/obesity). As the review focuses on the primary prevention of CVD, we excluded those who have experienced a previous myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, revascularisation procedure (coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA)), and those with angina or angiographically‐defined coronary heart disease (CHD). If participants were at high risk of CVD they were included if less than 25% of participants had CVD at baseline.

We also planned to exclude trials involving participants with type 2 diabetes, although this is a major risk factor for CVD, as interventions for the treatment and management of type 2 diabetes are covered by reviews registered with the Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group.

Types of interventions

The intervention was vitamin C supplements alone as a single ingredient. No limit was placed on the dose or frequency of vitamin C taken. Trials were only considered where the comparison group was placebo or no intervention. Multifactorial intervention studies (including other additional interventions such as dietary changes and exercise) were not included in this review, in order to avoid confounding. If there had been a sufficient number of trials, we also planned to stratify results by dose of vitamin C.

Types of outcome measures

We included studies with follow‐up periods of at least three months. Follow‐up is considered to be the time elapsed since the start of the intervention.

Primary outcomes

Major cardiovascular events, cardiovascular mortality, all‐cause mortality.

- Non‐fatal endpoints such as MI, CABG, PTCA, angina, or angiographically‐defined CHD, stroke, carotid endarterectomy, peripheral arterial disease (PAD)

Secondary outcomes

- Changes in blood pressure (BP) (systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) and blood lipids (total cholesterol, high‐density lipid (HDL) cholesterol, low‐density lipid (LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides)

- Occurrence of type 2 diabetes as a major CVD risk factor

- Validated health‐related quality of life measures

Adverse effects

Search methods for identification of studies, electronic searches.

We identified trials through systematic searches of the following bibliographic databases on 11 May 2016:

- Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library (2016, Issue 4 of 12)

- Health Technology Assessment (HTA) in the Cochrane Library (2016, Issue 2 of 4)

- Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) in the Cochrane Library (2015, Issue 2 of 4)

- NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NEED) in the Cochrane Library (2015, Issue 2 of 4)

- MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to April week 4 2016)

- Embase Classic and Embase (Ovid, 1947 to 2016 Week 19)

- Web of Science Core Collection (Thomson Reuters, 1970 to 11 May 2016)

We used Medical subject headings (MeSH) or equivalent and text word terms. Searches were designed in accordance with the Cochrane Heart Group methods and guidance.

The search strategies are detailed in Appendix 1 . The Cochrane sensitivity‐maximising RCT filter ( Lefebvre 2011 ) was applied to MEDLINE (Ovid) and adaptations of it to the other databases, except CENTRAL.

We searched all databases from their inception to the present, and we imposed no restriction on language of publication.

Searching other resources

We checked reference lists of reviews for additional studies. We searched ClinicalTrials.gov (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/) and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry platform (ICTRP) search portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/) for ongoing trials on 13 April 2016 using the search terms Vitamin C OR ascorbic acid AND cardio*. Where necessary we contacted authors for any additional information.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (LA, LH, NF, RW, OG or KR) independently screened for inclusion titles and abstracts of all the studies we identified as a result of the search, and coded them as 'retrieve' (eligible or potentially eligible/unclear) or 'do not retrieve'. We retrieved the full‐text study reports/publication and two review authors (LA, LH, NF, RW, OG or KR) independently screened the full‐text and identified studies for inclusion, and identified and recorded reasons for exclusion of the ineligible studies. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third author (KR/SS). We identified and excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study rather than each report was the unit of interest in the review. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram ( Figure 1 ) and ' Characteristics of excluded studies ' table.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (LA, LH, NF, RW) independently extracted study characteristics from included studies using a pre‐standardised data extraction form, and contacted chief investigators to request additional relevant information if necessary. We extracted details of the study design, participant characteristics, study setting, intervention (including dose and duration), and outcome data including details of outcome assessment, adverse effects, and methodological quality (randomisation, blinding, attrition) from each of the included studies. We resolved disagreements by consensus or by involving a third author (KR/SS). One author (NF) transferred data into the Review Manager ( RevMan 2012 ) file. We double‐checked that data were entered correctly by comparing the data presented in the systematic review with the study reports. A second author (KR/LA) spot‐checked study characteristics for accuracy against the trial report.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (NF, RW) independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions ( Higgins 2011 ). We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by involving another author (KR/SS). We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains.

- Random sequence generation

- Allocation concealment

- Blinding of participants and personnel

- Blinding of outcome assessment

Incomplete outcome data

- Selective outcome reporting

- Other bias (bias due to problems not covered elsewhere, e.g. industry funding)

We graded each potential source of bias as having a 'low risk of bias', a 'high risk of bias' or an 'unclear risk of bias'. Studies were regarded as at high risk of bias if any of the domains listed above were regarded at high risk of bias.

Assessment of bias in conducting the systematic review

We conducted the review according to the published protocol and report any deviations from it in the ' Differences between protocol and review ' section of the systematic review.

Measures of treatment effect

Data were processed in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions ( Higgins 2011 ). We expressed dichotomous outcomes as hazard ratios (HRs), with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous outcomes, net changes were compared (i.e. intervention group minus control group differences) and a mean difference (MD) and 95% CIs calculated for each study.

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over trials.

We used data only from the first half of the trial as a parallel group design. We only considered risk factor changes (i.e. blood pressure, lipid levels) before patients crossed over to the other therapy and where the duration was a minimum of three months before cross‐over occurred.

Studies with multiple intervention groups

Data for the control group were used for each intervention group comparison. We reduced the weight assigned to the control group by dividing the control group number (N) by the number of intervention groups.

Cluster‐randomised trials

If identified, we intended to analyse cluster‐randomised trials using the unit of randomisation (cluster) as the number of observations. Where necessary, individual‐level means and standard deviations (SDs) adjusted for clustering would be utilised together with the number of clusters in the denominator, in order to weight the trials appropriately. We did not find any cluster‐RCTs that met the inclusion criteria for our review.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted investigators in order to verify key study characteristics and obtain missing numerical outcome data where possible.

Missing data were captured in the data extraction form and reported in the 'Risk of bias' table. If a trial collected an outcome measure at more than one time point, the longest period of follow‐up with 20% or fewer dropouts was utilised.

Assessment of heterogeneity

For each outcome, we conducted tests of heterogeneity using the Chi 2 test of heterogeneity and I 2 statistic. Where there was no heterogeneity, a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis was performed. If moderate to substantial heterogeneity was detected (40% to 100%), we looked for possible explanations for this (e.g. participants and intervention). If the source of heterogeneity could not be explained, we considered the following options: provide a narrative overview and not aggregate the studies at all or use a random‐effects model with appropriate cautious interpretation.

Assessment of reporting biases

Had there been sufficient studies (10 or more), we intended to plot the trial effect against the standard error and present the results as funnel plots ( Sterne 2011 ). Since asymmetry could be caused by a relationship between effect size and sample size or by publication bias, we planned to examine any observed effect for clinical heterogeneity and carry out additional sensitivity tests ( Sterne 2011 ). There were insufficient trials to conduct this analysis.

Data synthesis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the Cochrane Collaboration’s statistical software, ( RevMan 2012 ). Dichotomous data were entered as events and the number of participants and continuous data were entered as means and SDs. In the absence of moderate to substantial heterogeneity (40% to 100%) and provided that there were sufficient trials, we combined the results, using a fixed‐effect model. In the presence of substantial heterogeneity we plotted the effects for individual trials in the forest plot but have not pooled them statistically.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If there were sufficient trials (10 or more) we intended to stratify results by high risk of CVD versus the general population, and also by dose of vitamin C.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analyses with studies of six months or more follow‐up, and excluding studies at a high risk of bias. Studies were regarded as at high risk of bias if any of the domains in the risk of bias tool were regarded at high risk of bias.

Quality of evidence

We present the overall quality of the evidence for each outcome according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, which takes into account issues not only related to internal validity (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias), but also to external validity such as directness of results. Two review authors (LA, KR) rated the quality for each outcome. We presented a summaries of the evidence in Table 1 , which provides key information about the best estimate of the magnitude of the effect, in relative terms for each relevant comparison of alternative management strategies, numbers of participants and trials addressing each important outcome, and the rating of the overall confidence in effect estimates for each outcome. We created the 'Summary of findings' table based on the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions ( Higgins 2011 ). We presented results on the outcomes as described in Types of outcome measures .

In addition, we established an appendix 'Checklist to aid consistency and reproducibility of GRADE assessments' ( Meader 2014 ) to help with standardisation of 'Summary of findings' tables ( Appendix 2 ).

Description of studies

Results of the search.

The searches generated 5555 hits after duplicates were removed. Screening of titles and abstracts identified 227 papers to go forward for formal inclusion and exclusion. Of these, nine randomised controlled trials (RCTs) met the inclusion criteria. There is one trial in abstract form awaiting classification. Details of the flow of studies through the review are shown in the PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1 .

Included studies

Details of the methods, participants, intervention, comparison group and outcome measures for each of the studies included in the review are shown in the Characteristics of included studies . Eight trials were included randomising a total of 15,445 participants. The largest trial recruited males only (14,641 randomised) ( The Physicians Health Study II ), six trials recruited male and female participants, and one trial did not specify the gender of participants ( Mostafa 1989 ). The trials varied in the participants recruited. Three trials recruited patients with hypercholesterolaemia ( ASAP Study ; Cerna 1992 ; Jacques 1995 ), one trial recruited patients with hypertension ( Schindler 2003 ), one trial recruited older participants aged 60 to 80 years, some with borderline or newly diagnosed hypertension ( Fotherby 2000 ), one trial recruited healthy young medical students aged 18 to 25 years ( Menne 1975 ), another recruited from a US University campus, but no details of age were provided ( Mostafa 1989 ), and the largest trial recruited US male physicians aged 50 years or older at the start of the study ( The Physicians Health Study II ), where some participants had CVD risk factors (see Characteristics of included studies ).

Two trials were conducted in Boston, MA, USA ( Jacques 1995 ; The Physicians Health Study II ). The remaining studies were conducted in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia ( Cerna 1992 ), the UK ( Fotherby 2000 ), South Africa ( Menne 1975 ), Mississippi, USA ( Mostafa 1989 ), Kuopio, Eastern Finland ( ASAP Study ), and for one trial this was unclear ( Schindler 2003 ).

The duration of the intervention and follow‐up periods varied considerably from three months to eight years. The trial with the longest intervention and follow‐up period was eight years ( The Physicians Health Study II ). This was followed by three years ( ASAP Study ); two years ( Schindler 2003 ), 18 months ( Cerna 1992 ), eight months ( Jacques 1995 ), six months ( Mostafa 1989 ), four months ( Menne 1975 ), and three months ( Fotherby 2000 ).

In five of the trials the dose of vitamin C supplementation was 500 mg/day ( ASAP Study ; Cerna 1992 ; Fotherby 2000 ; Mostafa 1989 ; The Physicians Health Study II ); in two trials the dose was 1 g/day ( Jacques 1995 ; Menne 1975 ), and in the remaining trial the dose was 2 g/day ( Schindler 2003 ).

Details of the trial awaiting assessment is presented in the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table. This study is only available as an abstract and we are awaiting responses from the authors to our requests asking for further information.

Excluded studies

Details and reasons for exclusion for studies that closely missed the inclusion criteria are provided in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Reasons for exclusion for the majority of studies included alternative designs (not RCTs), short‐term studies (< three months), and no relevant outcomes (see Figure 1 ).

Risk of bias in included studies

Details are presented for the included trial in the 'Risk of bias' tables in the Characteristics of included studies table and in Figure 2 ; Figure 3 .

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Only one study reported the method of random sequence generation which was regarded as at low risk of bias ( The Physicians Health Study II ); for the remaining eight studies this was unclear. No details were provided for the method of allocation concealment in all eight trials so this was judged to be at unclear risk of bias.

Five trials reported blinding participants and personnel and were judged to be at low risk of performance bias ( ASAP Study ; Fotherby 2000 ; Jacques 1995 ; Mostafa 1989 ; The Physicians Health Study II ). The remaining three studies were at unclear risk of performance bias as blinding or participants and personnel were not reported ( Cerna 1992 ; Menne 1975 ; Schindler 2003 ). Two trials were judged to be at low risk of detection bias as outcome assessors were blind to group allocation ( Fotherby 2000 ; The Physicians Health Study II ). For the remaining six trials blinding of outcome assessors was not stated and this was judged to be at unclear risk of bias ( ASAP Study ; Cerna 1992 ; Jacques 1995 ; Menne 1975 ; Mostafa 1989 ; Schindler 2003 ).

There was a low risk of attrition bias in three trials ( ASAP Study ; Jacques 1995 ; The Physicians Health Study II ). In one trial there was a high risk of attrition bias as no reasons for loss to follow‐up were given and the authors did not perform an intention‐to‐treat analysis ( Schindler 2003 ). For the remaining four studies this was judged as unclear ( Cerna 1992 ; Fotherby 2000 ; Menne 1975 ; Mostafa 1989 ).

Selective reporting

Two studies were judged to be at high risk of reporting bias ( ASAP Study ; Mostafa 1989 ). The first because no outcome data were provided for total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides or blood pressure ( ASAP Study ), the second because outcome data were not provided for the control group ( Mostafa 1989 ).

Other potential sources of bias

There was insufficient information to judge other potential sources of bias and all studies were regarded as unclear risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1