Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 24 November 2021

A study of awareness on HIV/AIDS among adolescents: A Longitudinal Study on UDAYA data

- Shobhit Srivastava ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7138-4916 1 ,

- Shekhar Chauhan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6926-7649 2 ,

- Ratna Patel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5371-7369 3 &

- Pradeep Kumar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4259-820X 1

Scientific Reports volume 11 , Article number: 22841 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

7 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health care

- Health services

- Public health

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome caused by Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) poses a severe challenge to healthcare and is a significant public health issue worldwide. This study intends to examine the change in the awareness level of HIV among adolescents. Furthermore, this study examined the factors associated with the change in awareness level on HIV-related information among adolescents over the period. Data used for this study were drawn from Understanding the lives of adolescents and young adults, a longitudinal survey on adolescents aged 10–19 in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. The present study utilized a sample of 4421 and 7587 unmarried adolescent boys and girls, respectively aged 10–19 years in wave-1 and wave-2. Descriptive analysis and t-test and proportion test were done to observe changes in certain selected variables from wave-1 (2015–2016) to wave-2 (2018–2019). Moreover, random effect regression analysis was used to estimate the association of change in HIV awareness among unmarried adolescents with household and individual factors. The percentage of adolescent boys who had awareness regarding HIV increased from 38.6% in wave-1 to 59.9% in wave-2. Among adolescent girls, the percentage increased from 30.2 to 39.1% between wave-1 & wave-2. With the increase in age and years of schooling, the HIV awareness increased among adolescent boys ([Coef: 0.05; p < 0.01] and [Coef: 0.04; p < 0.01]) and girls ([Coef: 0.03; p < 0.01] and [Coef: 0.04; p < 0.01]), respectively. The adolescent boys [Coef: 0.06; p < 0.05] and girls [Coef: 0.03; p < 0.05] who had any mass media exposure were more likely to have an awareness of HIV. Adolescent boys' paid work status was inversely associated with HIV awareness [Coef: − 0.01; p < 0.10]. Use of internet among adolescent boys [Coef: 0.18; p < 0.01] and girls [Coef: 0.14; p < 0.01] was positively associated with HIV awareness with reference to their counterparts. There is a need to intensify efforts in ensuring that information regarding HIV should reach vulnerable sub-groups, as outlined in this study. It is important to mobilize the available resources to target the less educated and poor adolescents, focusing on rural adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Predictors of never testing for HIV among sexually active individuals aged 15–56 years in Rwanda

Awareness and use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and factors associated with awareness among MSM in Beijing, China

Identification of adolescent girls and young women for targeted HIV prevention: a new risk scoring tool in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa

Introduction.

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) caused by Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) poses a severe challenge to healthcare and is a significant public health issue worldwide. So far, HIV has claimed almost 33 million lives; however, off lately, increasing access to HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and care has enabled people living with HIV to lead a long and healthy life 1 . By the end of 2019, an estimated 38 million people were living with HIV 1 . More so, new infections fell by 39 percent, and HIV-related deaths fell by almost 51 percent between 2000 and 2019 1 . Despite all the positive news related to HIV, the success story is not the same everywhere; HIV varies between region, country, and population, where not everyone is able to access HIV testing and treatment and care 1 . HIV/AIDS holds back economic growth by destroying human capital by predominantly affecting adolescents and young adults 2 .

There are nearly 1.2 billion adolescents (10–19 years) worldwide, which constitute 18 percent of the world’s population, and in some countries, adolescents make up as much as one-fourth of the population 3 . In India, adolescents comprise more than one-fifth (21.8%) of the total population 4 . Despite a decline projection for the adolescent population in India 5 , there is a critical need to hold adolescents as adolescence is characterized as a period when peer victimization/pressure on psychosocial development is noteworthy 6 . Peer victimization/pressure is further linked to risky sexual behaviours among adolescents 7 , 8 . A higher proportion of low literacy in the Indian population leads to a low level of awareness of HIV/AIDS 9 . Furthermore, the awareness of HIV among adolescents is quite alarming 10 , 11 , 12 .

Unfortunately, there is a shortage of evidence on what predicts awareness of HIV among adolescents. Almost all the research in India is based on beliefs, attitudes, and awareness of HIV among adolescents 2 , 12 . However, few other studies worldwide have examined mass media as a strong predictor of HIV awareness among adolescents 13 . Mass media is an effective channel to increase an individuals’ knowledge about sexual health and improve understanding of facilities related to HIV prevention 14 , 15 . Various studies have outlined other factors associated with the increasing awareness of HIV among adolescents, including; age 16 , 17 , 18 , occupation 18 , education 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , sex 16 , place of residence 16 , marital status 16 , and household wealth index 16 .

Several community-based studies have examined awareness of HIV among Indian adolescents 2 , 10 , 12 , 20 , 21 , 22 . However, studies investigating awareness of HIV among adolescents in a larger sample size remained elusive to date, courtesy of the unavailability of relevant data. Furthermore, no study in India had ever examined awareness of HIV among adolescents utilizing information on longitudinal data. To the author’s best knowledge, this is the first study in the Indian context with a large sample size that examines awareness of HIV among adolescents and combines information from a longitudinal survey. Therefore, this study intends to examine the change in the awareness level of HIV among adolescents. Furthermore, this study examined the factors associated with a change in awareness level on HIV-related information among adolescents over the period.

Data and methods

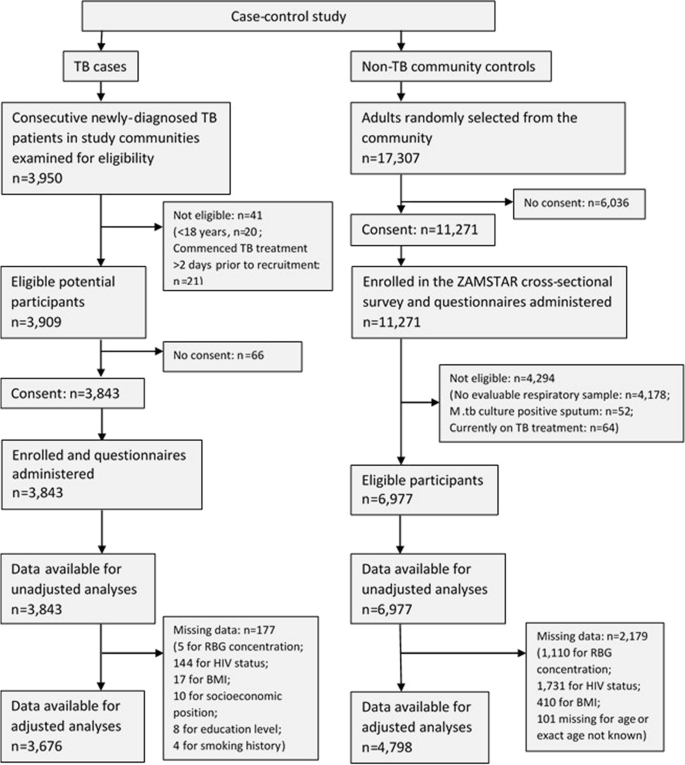

Data used for this study were drawn from Understanding the lives of adolescents and young adults (UDAYA), a longitudinal survey on adolescents aged 10–19 in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh 23 . The first wave was conducted in 2015–2016, and the follow-up survey was conducted after three years in 2018–2019 23 . The survey provides the estimates for state and the sample of unmarried boys and girls aged 10–19 and married girls aged 15–19. The study adopted a systematic, multi-stage stratified sampling design to draw sample areas independently for rural and urban areas. 150 primary sampling units (PSUs)—villages in rural areas and census wards in urban areas—were selected in each state, using the 2011 census list of villages and wards as the sampling frame. In each primary sampling unit (PSU), households to be interviewed were selected by systematic sampling. More details about the study design and sampling procedure have been published elsewhere 23 . Written consent was obtained from the respondents in both waves. In wave 1 (2015–2016), 20,594 adolescents were interviewed using the structured questionnaire with a response rate of 92%.

Moreover, in wave 2 (2018–2019), the study interviewed the participants who were successfully interviewed in 2015–2016 and who consented to be re-interviewed 23 . Of the 20,594 eligible for the re-interview, the survey re-interviewed 4567 boys and 12,251 girls (married and unmarried). After excluding the respondents who gave an inconsistent response to age and education at the follow-up survey (3%), the final follow-up sample covered 4428 boys and 11,864 girls with the follow-up rate of 74% for boys and 81% for girls. The effective sample size for the present study was 4421 unmarried adolescent boys aged 10–19 years in wave-1 and wave-2. Additionally, 7587 unmarried adolescent girls aged 10–19 years were interviewed in wave-1 and wave-2 23 . The cases whose follow-up was lost were excluded from the sample to strongly balance the dataset and set it for longitudinal analysis using xtset command in STATA 15. The survey questionnaire is available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/file.xhtml?fileId=4163718&version=2.0 & https://dataverse.harvard.edu/file.xhtml?fileId=4163720&version=2.0 .

Outcome variable

HIV awareness was the outcome variable for this study, which is dichotomous. The question was asked to the adolescents ‘Have you heard of HIV/AIDS?’ The response was recorded as yes and no.

Exposure variables

The predictors for this study were selected based on previous literature. These were age (10–19 years at wave 1, continuous variable), schooling (continuous), any mass media exposure (no and yes), paid work in the last 12 months (no and yes), internet use (no and yes), wealth index (poorest, poorer, middle, richer, and richest), religion (Hindu and Non-Hindu), caste (Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe, Other Backward Class, and others), place of residence (urban and rural), and states (Uttar Pradesh and Bihar).

Exposure to mass media (how often they read newspapers, listened to the radio, and watched television; responses on the frequencies were: almost every day, at least once a week, at least once a month, rarely or not at all; adolescents were considered to have any exposure to mass media if they had exposure to any of these sources and as having no exposure if they responded with ‘not at all’ for all three sources of media) 24 . Household wealth index based on ownership of selected durable goods and amenities with possible scores ranging from 0 to 57; households were then divided into quintiles, with the first quintile representing households of the poorest wealth status and the fifth quintile representing households with the wealthiest status 25 .

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was done to observe the characteristics of unmarried adolescent boys and girls at wave-1 (2015–2016). In addition, the changes in certain selected variables were observed from wave-1 (2015–2016) to wave-2 (2018–2019), and the significance was tested using t-test and proportion test 26 , 27 . Moreover, random effect regression analysis 28 , 29 was used to estimate the association of change in HIV awareness among unmarried adolescents with household factors and individual factors. The random effect model has a specific benefit for the present paper's analysis: its ability to estimate the effect of any variable that does not vary within clusters, which holds for household variables, e.g., wealth status, which is assumed to be constant for wave-1 and wave-2 30 .

Table 1 represents the socio-economic profile of adolescent boys and girls. The estimates are from the baseline dataset, and it was assumed that none of the household characteristics changed over time among adolescent boys and girls.

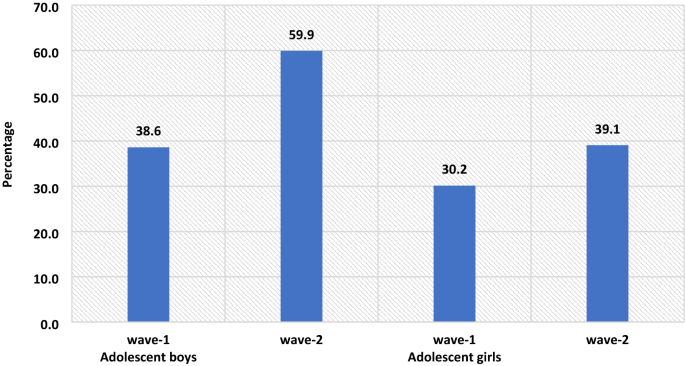

Figure 1 represents the change in HIV awareness among adolescent boys and girls. The percentage of adolescent boys who had awareness regarding HIV increased from 38.6% in wave-1 to 59.9% in wave-2. Among adolescent girls, the percentage increased from 30.2% in wave-1 to 39.1% in wave-2.

The percenate of HIV awareness among adolescent boys and girls, wave-1 (2015–2016) and wave-2 (2018–2019).

Table 2 represents the summary statistics for explanatory variables used in the analysis of UDAYA wave-1 and wave-2. The exposure to mass media is almost universal for adolescent boys, while for adolescent girls, it increases to 93% in wave-2 from 89.8% in wave-1. About 35.3% of adolescent boys were engaged in paid work during wave-1, whereas in wave-II, the share dropped to 33.5%, while in the case of adolescent girls, the estimates are almost unchanged. In wave-1, about 27.8% of adolescent boys were using the internet, while in wave-2, there is a steep increase of nearly 46.2%. Similarly, in adolescent girls, the use of the internet increased from 7.6% in wave-1 to 39.3% in wave-2.

Table 3 represents the estimates from random effects for awareness of HIV among adolescent boys and girls. It was found that with the increases in age and years of schooling the HIV awareness increased among adolescent boys ([Coef: 0.05; p < 0.01] and [Coef: 0.04; p < 0.01]) and girls ([Coef: 0.03; p < 0.01] and [Coef: 0.04; p < 0.01]), respectively. The adolescent boys [Coef: 0.06; p < 0.05] and girls [Coef: 0.03; p < 0.05] who had any mass media exposure were more likely to have an awareness of HIV in comparison to those who had no exposure to mass media. Adolescent boys' paid work status was inversely associated with HIV awareness about adolescent boys who did not do paid work [Coef: − 0.01; p < 0.10]. Use of the internet among adolescent boys [Coef: 0.18; p < 0.01] and girls [Coef: 0.14; p < 0.01] was positively associated with HIV awareness in reference to their counterparts.

The awareness regarding HIV increases with the increase in household wealth index among both adolescent boys and girls. The adolescent girls from the non-Hindu household had a lower likelihood to be aware of HIV in reference to adolescent girls from Hindu households [Coef: − 0.09; p < 0.01]. Adolescent girls from non-SC/ST households had a higher likelihood of being aware of HIV in reference to adolescent girls from other caste households [Coef: 0.04; p < 0.01]. Adolescent boys [Coef: − 0.03; p < 0.01] and girls [Coef: − 0.09; p < 0.01] from a rural place of residence had a lower likelihood to be aware about HIV in reference to those from the urban place of residence. Adolescent boys [Coef: 0.04; p < 0.01] and girls [Coef: 0.02; p < 0.01] from Bihar had a higher likelihood to be aware about HIV in reference to those from Uttar Pradesh.

This is the first study of its kind to address awareness of HIV among adolescents utilizing longitudinal data in two indian states. Our study demonstrated that the awareness of HIV has increased over the period; however, it was more prominent among adolescent boys than in adolescent girls. Overall, the knowledge on HIV was relatively low, even during wave-II. Almost three-fifths (59.9%) of the boys and two-fifths (39.1%) of the girls were aware of HIV. The prevalence of awareness on HIV among adolescents in this study was lower than almost all of the community-based studies conducted in India 10 , 11 , 22 . A study conducted in slums in Delhi has found almost similar prevalence (40% compared to 39.1% during wave-II in this study) of awareness of HIV among adolescent girls 31 . The difference in prevalence could be attributed to the difference in methodology, study population, and study area.

The study found that the awareness of HIV among adolescent boys has increased from 38.6 percent in wave-I to 59.9 percent in wave-II; similarly, only 30.2 percent of the girls had an awareness of HIV during wave-I, which had increased to 39.1 percent. Several previous studies corroborated the finding and noticed a higher prevalence of awareness on HIV among adolescent boys than in adolescent girls 16 , 32 , 33 , 34 . However, a study conducted in a different setting noticed a higher awareness among girls than in boys 35 . Also, a study in the Indian context failed to notice any statistical differences in HIV knowledge between boys and girls 18 . Gender seems to be one of the significant determinants of comprehensive knowledge of HIV among adolescents. There is a wide gap in educational attainment among male and female adolescents, which could be attributed to lower awareness of HIV among girls in this study. Higher peer victimization among adolescent boys could be another reason for higher awareness of HIV among them 36 . Also, cultural double standards placed on males and females that encourage males to discuss HIV/AIDS and related sexual matters more openly and discourage or even restrict females from discussing sexual-related issues could be another pertinent factor of higher awareness among male adolescents 33 . Behavioural interventions among girls could be an effective way to improving knowledge HIV related information, as seen in previous study 37 . Furthermore, strengthening school-community accountability for girls' education would augment school retention among girls and deliver HIV awareness to girls 38 .

Similar to other studies 2 , 10 , 17 , 18 , 39 , 40 , 41 , age was another significant determinant observed in this study. Increasing age could be attributed to higher education which could explain better awareness with increasing age. As in other studies 18 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , education was noted as a significant driver of awareness of HIV among adolescents in this study. Higher education might be associated with increased probability of mass media and internet exposure leading to higher awareness of HIV among adolescents. A study noted that school is one of the important factors in raising the awareness of HIV among adolescents, which could be linked to higher awareness among those with higher education 47 , 48 . Also, schooling provides adolescents an opportunity to improve their social capital, leading to increased awareness of HIV.

Following previous studies 18 , 40 , 46 , the current study also outlines a higher awareness among urban adolescents than their rural counterparts. One plausible reason for lower awareness among adolescents in rural areas could be limited access to HIV prevention information 16 . Moreover, rural–urban differences in awareness of HIV could also be due to differences in schooling, exposure to mass media, and wealth 44 , 45 . The household's wealth status was also noted as a significant predictor of awareness of HIV among adolescents. Corroborating with previous findings 16 , 33 , 42 , 49 , this study reported a higher awareness among adolescents from richer households than their counterparts from poor households. This could be because wealthier families can afford mass-media items like televisions and radios for their children, which, in turn, improves awareness of HIV among adolescents 33 .

Exposure to mass media and internet access were also significant predictors of higher awareness of HIV among adolescents. This finding agrees with several previous research, and almost all the research found a positive relationship between mass-media exposure and awareness of HIV among adolescents 10 . Mass media addresses such topics more openly and in a way that could attract adolescents’ attention is the plausible reason for higher awareness of HIV among those having access to mass media and the internet 33 . Improving mass media and internet usage, specifically among rural and uneducated masses, would bring required changes. Integrating sexual education into school curricula would be an important means of imparting awareness on HIV among adolescents; however, this is debatable as to which standard to include the required sexual education in the Indian schooling system. Glick (2009) thinks that the syllabus on sexual education might be included during secondary schooling 44 . Another study in the Indian context confirms the need for sex education for adolescents 50 , 51 .

Limitations and strengths of the study

The study has several limitations. At first, the awareness of HIV was measured with one question only. Given that no study has examined awareness of HIV among adolescents using longitudinal data, this limitation is not a concern. Second, the study findings cannot be generalized to the whole Indian population as the study was conducted in only two states of India. However, the two states selected in this study (Uttar Pradesh and Bihar) constitute almost one-fourth of India’s total population. Thirdly, the estimates were provided separately for boys and girls and could not be presented combined. However, the data is designed to provide estimates separately for girls and boys. The data had information on unmarried boys and girls and married girls; however, data did not collect information on married boys. Fourthly, the study estimates might have been affected by the recall bias. Since HIV is a sensitive topic, the possibility of respondents modifying their responses could not be ruled out. Hawthorne effect, respondents, modifying aspect of their behaviour in response, has a role to play in HIV related study 52 . Despite several limitations, the study has specific strengths too. This is the first study examining awareness of HIV among adolescent boys and girls utilizing longitudinal data. The study was conducted with a large sample size as several previous studies were conducted in a community setting with a minimal sample size 10 , 12 , 18 , 20 , 53 .

The study noted a higher awareness among adolescent boys than in adolescent girls. Specific predictors of high awareness were also noted in the study, including; higher age, higher education, exposure to mass media, internet use, household wealth, and urban residence. Based on the study findings, this study has specific suggestions to improve awareness of HIV among adolescents. There is a need to intensify efforts in ensuring that information regarding HIV should reach vulnerable sub-groups as outlined in this study. It is important to mobilize the available resources to target the less educated and poor adolescents, focusing on rural adolescents. Investment in education will help, but it would be a long-term solution; therefore, public information campaigns could be more useful in the short term.

WHO. HIV/AIDS . https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids (2020).

Singh, A. & Jain, S. Awareness of HIV/AIDS among school adolescents in Banaskantha district of Gujarat. Health Popul.: Perspect. Issues 32 , 59–65 (2009).

Google Scholar

WHO & UNICEF. adolescents Health: The Missing Population in Universal Health Coverage . 1–31 https://www.google.com/search?q=adolescents+population+WHO+report&rlz=1C1CHBF_enIN904IN904&oq=adolescents+population+WHO+report&aqs=chrome..69i57.7888j1j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 (2018).

Chauhan, S. & Arokiasamy, P. India’s demographic dividend: state-wise perspective. J. Soc. Econ. Dev. 20 , 1–23 (2018).

Tiwari, A. K., Singh, B. P. & Patel, V. Population projection of India: an application of dynamic demographic projection model. JCR 7 , 547–555 (2020).

Troop-Gordon, W. Peer victimization in adolescence: the nature, progression, and consequences of being bullied within a developmental context. J. Adolesc. 55 , 116–128 (2017).

PubMed Google Scholar

Dermody, S. S., Friedman, M., Chisolm, D. J., Burton, C. M. & Marshal, M. P. Elevated risky sexual behaviors among sexual minority girls: indirect risk pathways through peer victimization and heavy drinking. J. Interpers. Violence 35 , 2236–2253 (2020).

Lee, R. L. T., Loke, A. Y., Hung, T. T. M. & Sobel, H. A systematic review on identifying risk factors associated with early sexual debut and coerced sex among adolescents and young people in communities. J. Clin. Nurs. 27 , 478–501 (2018).

Gurram, S. & Bollampalli, B. A study on awareness of human immunodeficiency virus among adolescent girls in urban and rural field practice areas of Osmania Medical College, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. (2020).

Jain, R., Anand, P., Dhyani, A. & Bansal, D. Knowledge and awareness regarding menstruation and HIV/AIDS among schoolgoing adolescent girls. J. Fam. Med. Prim Care 6 , 47–51 (2017).

Kawale, S., Sharma, V., Thaware, P. & Mohankar, A. A study to assess awareness about HIV/AIDS among rural population of central India. Int. J. Commun. Med. Public Health 5 , 373–376 (2017).

Lal, P., Nath, A., Badhan, S. & Ingle, G. K. A study of awareness about HIV/AIDS among senior secondary school Children of Delhi. Indian J. Commun. Med. 33 , 190–192 (2008).

CAS Google Scholar

Bago, J.-L. & Lompo, M. L. Exploring the linkage between exposure to mass media and HIV awareness among adolescents in Uganda. Sex. Reprod. Healthcare 21 , 1–8 (2019).

McCombie, S., Hornik, R. C. & Anarfi, J. K. Effects of a mass media campaign to prevent AIDS among young people in Ghana . Public Health Commun. 163–178 (Routledge, 2002). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410603029-17 .

Sano, Y. et al. Exploring the linkage between exposure to mass media and HIV testing among married women and men in Ghana. AIDS Care 28 , 684–688 (2016).

Oginni, A. B., Adebajo, S. B. & Ahonsi, B. A. Trends and determinants of comprehensive knowledge of HIV among adolescents and young adults in Nigeria: 2003–2013. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 21 , 26–34 (2017).

Rahman, M. M., Kabir, M. & Shahidullah, M. Adolescent knowledge and awareness about AIDS/HIV and factors affecting them in Bangladesh. J. Ayub. Med. Coll. Abbottabad 21 , 3–6 (2009).

Yadav, S. B., Makwana, N. R., Vadera, B. N., Dhaduk, K. M. & Gandha, K. M. Awareness of HIV/AIDS among rural youth in India: a community based cross-sectional study. J. Infect. Dev. Countries 5 , 711–716 (2011).

Alhasawi, A. et al. Assessing HIV/AIDS knowledge, awareness, and attitudes among senior high school students in Kuwait. MPP 28 , 470–476 (2019).

Chakrovarty, A. et al. A study of awareness on HIV/AIDS among higher secondary school students in Central Kolkata. Indian J. Commun. Med. 32 , 228 (2007).

Katoch, D. K. S. & Kumar, A. HIV/AIDS awareness among students of tribal and non-tribal area of Himachal Pradesh. J. Educ. 5 , 1–9 (2017).

Shinde, M., Trivedi, A., Shinde, A. & Mishra, S. A study of awareness regarding HIV/AIDS among secondary school students. Int. J. Commun. Med. Public Health https://doi.org/10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20161611 (2016).

Article Google Scholar

Council, P. UDAYA, adolescent survey, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, 2015–16. Harvard Dataverse https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RRXQNT (2018).

Kumar, P. & Dhillon, P. Household- and community-level determinants of low-risk Caesarean deliveries among women in India. J. Biosoc. Sci. 53 , 55–70 (2021).

Patel, S. K., Santhya, K. G. & Haberland, N. What shapes gender attitudes among adolescent girls and boys? Evidence from the UDAYA Longitudinal Study in India. PLoS ONE 16 , e0248766 (2021).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fan, C., Wang, L. & Wei, L. Comparing two tests for two rates. Am. Stat. 71 , 275–281 (2017).

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Kim, T. K. T test as a parametric statistic. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 68 , 540–546 (2015).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bell, A., Fairbrother, M. & Jones, K. Fixed and random effects models: making an informed choice. Qual. Quant. 53 , 1051–1074 (2019).

Jarrett, R., Farewell, V. & Herzberg, A. Random effects models for complex designs. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 29 , 3695–3706 (2020).

MathSciNet CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Neuhaus, J. M. & Kalbfleisch, J. D. Between- and within-cluster covariate effects in the analysis of clustered data. Biometrics 54 , 638–645 (1998).

CAS PubMed MATH Google Scholar

Kaur, G. Factors influencing HIV awareness amongst adolescent women: a study of slums in Delhi. Demogr. India 47 , 100–111 (2018).

Alene, G. D., Wheeler, J. G. & Grosskurth, H. Adolescent reproductive health and awareness of HIV among rural high school students, North Western Ethiopia. AIDS Care 16 , 57–68 (2004).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Oljira, L., Berhane, Y. & Worku, A. Assessment of comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge level among in-school adolescents in eastern Ethiopia. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 16 , 17349 (2013).

Samkange-Zeeb, F. N., Spallek, L. & Zeeb, H. Awareness and knowledge of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) among school-going adolescents in Europe: a systematic review of published literature. BMC Public Health 11 , 727 (2011).

Laguna, E. P. Knowledge of HIV/AIDS and unsafe sex practices among Filipino youth. in 15 (PAA, 2004).

Teitelman, A. M. et al. Partner violence, power, and gender differences in South African adolescents’ HIV/sexually transmitted infections risk behaviors. Health Psychol. 35 , 751–760 (2016).

Oberth, G. et al. Effectiveness of the Sista2Sista programme in improving HIV and other sexual and reproductive health outcomes among vulnerable adolescent girls and young women in Zimbabwe. Afr. J. AIDS Res. 20 , 158–164 (2021).

DeSoto, J. et al. Using school-based early warning systems as a social and behavioral approach for HIV prevention among adolescent girls. Preventing HIV Among Young People in Southern and Eastern Africa 280 (2020).

Ochako, R., Ulwodi, D., Njagi, P., Kimetu, S. & Onyango, A. Trends and determinants of Comprehensive HIV and AIDS knowledge among urban young women in Kenya. AIDS Res. Ther. 8 , 11 (2011).

Peltzer, K. & Supa, P. HIV/AIDS knowledge and sexual behavior among junior secondary school students in South Africa. J. Soc. Sci. 1 , 1–8 (2005).

Shweta, C., Mundkur, S. & Chaitanya, V. Knowledge and beliefs about HIV/AIDS among adolescents. WebMed Cent. 2 , 1–9 (2011).

Anwar, M., Sulaiman, S. A. S., Ahmadi, K. & Khan, T. M. Awareness of school students on sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and their sexual behavior: a cross-sectional study conducted in Pulau Pinang, Malaysia. BMC Public Health 10 , 47 (2010).

Cicciò, L. & Sera, D. Assessing the knowledge and behavior towards HIV/AIDS among youth in Northern Uganda: a cross-sectional survey. Giornale Italiano di Medicina Tropicale 15 , 29–34 (2010).

Glick, P., Randriamamonjy, J. & Sahn, D. E. Determinants of HIV knowledge and condom use among women in madagascar: an analysis using matched household and community data. Afr. Dev. Rev. 21 , 147–179 (2009).

Rahman, M. Determinants of knowledge and awareness about AIDS: Urban-rural differentials in Bangladesh. JPHE 1 , 014–021 (2009).

Siziya, S., Muula, A. S. & Rudatsikira, E. HIV and AIDS-related knowledge among women in Iraq. BMC. Res. Notes 1 , 123 (2008).

Gao, X. et al. Effectiveness of school-based education on HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitude, and behavior among secondary school students in Wuhan, China. PLoS ONE 7 , e44881 (2012).

ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kotecha, P. V. et al. Reproductive health awareness among urban school going adolescents in Vadodara city. Indian J. Psychiatry 54 , 344–348 (2012).

Dimbuene, T. Z. & Defo, K. B. Fostering accurate HIV/AIDS knowledge among unmarried youths in Cameroon: do family environment and peers matter?. BMC Public Health 11 , 348 (2011).

Kumar, R. et al. Knowledge attitude and perception of sex education among school going adolescents in Ambala District, Haryana, India: a cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 11 , LC01–LC04 (2017).

ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tripathi, N. & Sekher, T. V. Youth in India ready for sex education? Emerging evidence from national surveys. PLoS ONE 8 , e71584 (2013).

Rosenberg, M. et al. Evidence for sample selection effect and Hawthorne effect in behavioural HIV prevention trial among young women in a rural South African community. BMJ Open 8 , e019167 (2018).

Gupta, P., Anjum, F., Bhardwaj, P., Srivastav, J. & Zaidi, Z. H. Knowledge about HIV/AIDS among secondary school students. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 5 , 119–123 (2013).

Download references

This paper was written using data collected as part of Population Council’s UDAYA study, which is funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. No additional funds were received for the preparation of the paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Ph.D. Research Scholar, Department of Survey Research & Data Analytics, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India

Shobhit Srivastava & Pradeep Kumar

Ph.D. Research Scholar, Department of Family and Generations, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India

Shekhar Chauhan

Ph.D. Research Scholar, Department of Public Health and Mortality Studies, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India

Ratna Patel

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conception and design of the study: S.S. and P.K.; analysis and/or interpretation of data: P.K. and S.S.; drafting the manuscript: S.C., and R.P.; reading and approving the manuscript: S.S., P.K., S.C. and R.P.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Pradeep Kumar .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Srivastava, S., Chauhan, S., Patel, R. et al. A study of awareness on HIV/AIDS among adolescents: A Longitudinal Study on UDAYA data. Sci Rep 11 , 22841 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02090-9

Download citation

Received : 05 June 2021

Accepted : 29 September 2021

Published : 24 November 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02090-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Open access

- Published: 07 December 2021

The lived experience of HIV-infected patients in the face of a positive diagnosis of the disease: a phenomenological study

- Behzad Imani ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1544-8196 1 ,

- Shirdel Zandi 2 ,

- Salman khazaei 3 &

- Mohamad Mirzaei 4

AIDS Research and Therapy volume 18 , Article number: 95 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

7523 Accesses

3 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

AIDS as a human crisis may lead to devastating psychological trauma and stress for patients. Therefore, it is necessary to study different aspects of their lives for better support and care. Accordingly, this study aimed to explain the lived experience of HIV-infected patients in the face of a positive diagnosis of the disease.

This qualitative study is a descriptive phenomenological study. Sampling was done purposefully and participants were selected based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data collection was conducted, using semi-structured interviews. Data analysis was performed using Colaizzi’s method.

12 AIDS patients participated in this study. As a result of data analysis, 5 main themes and 12 sub-themes were identified, which include : emotional shock (loathing, motivation of social isolation), the fear of the consequences (fear of the death, fear of loneliness, fear of disgrace), the feeling of the guilt (feeling of regret, feeling guilty, feeling of conscience-stricken), the discouragement (suicidal ideation, disappointment), and the escape from reality (denial, trying to hide).

The results of this study showed that patients will experience unpleasant phenomenon in the face of the positive diagnosis of the disease and will be subjected to severe psychological pressures that require attention and support of medical and laboratory centers.

Patients will experience severe psychological stress in the face of a positive diagnosis of HIV.

Patients who are diagnosed with HIV are prone to make a blunder and dreadful decisions.

AIDS patients need emotional and informational support when they receive a positive diagnosis.

As a piece of bad news, presenting the positive diagnosis of HIV required the psychic preparation of the patient

Introduction

HIV/AIDS pandemic is one of the most important economic, social, and human health problems in many countries of the world, whose, extent and dimensions are unfortunately ever-increasing [ 1 ]. In such circumstances, this phenomenon should be considered as a crisis, which seriously affects all aspects of the existence and life of patients and even the health of society [ 2 ]. Diagnosing and contracting HIV/AIDS puts a person in a vague and difficult situation. Patients suffer not only from the physical effects of the disease, but also from the disgraceful consequences of the disease. HIV/AIDS is usually associated with avoidable behaviors that are not socially acceptable, such as unhealthy sexual, relations and drug abuse: So the patients are usually held guilty for their illness [ 3 ]. On the other hand, the issue of disease stigma in the community is the cause of rejection and isolation of these patients, and in health care centers is a major obstacle to providing services to these patients [ 4 ]. Studies show that HIV/AIDS stigma has a completely negative effect on the quality of life of these patients [ 5 ]. Criminal attitudes towards these patients and disappointing behavior by family, community, and medical staff cause blame and discrimination in patients [ 6 ]. HIV/AIDS stigma is prevalent among diseases, making concealment a major problem in this behavioral disease. The stigma comes in two forms: a negative inner feeling and a negative feeling that other people in the community have towards the patient [ 7 ]. The findings of a study that conducted in Iran indicated that increasing HIV/AIDS-related stigma decreases quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS [ 8 ]. Robert Beckman has defined bad news as “any news that seriously and unpleasantly affects persons’ attitudes toward their future”. He considers the impact of counseling on moderating a person’s feeling of being important [ 9 ]. Therefore, being infected by HIV / AIDS due to the stigma can be bad news, which will lead to unpleasant emotional reactions [ 10 ]. Studies that have examined the lives of these patients have shown that these patients will experience mental and living problems throughout their lives. These studies highlight the need for age-specific programming to increase HIV knowledge and coping, increase screening, and improve long-term planning [ 11 , 12 ].

A prerequisite for any successful planning and intervention for people living with HIV/AIDS is approaching them and conducting in-depth interviews in order to discover their feelings, attitudes; their views on themselves, their illness, and others; and finally, their motivation to follow up and the participation in interventions [ 13 ]. Accordingly, the present study aimed to explain the lived experience of HIV-infected patients in the face of a positive diagnosis of the disease, since the better understanding of the phenomena leads to the smoother ways to help and care for these patients.

Study setting

In this study, a qualitative method of descriptive phenomenology was used to discover and interpret the lived experience of HIV-positive patients, when they face a positive diagnosis of the disease. The philosophical strengths underlying descriptive phenomenology afford a deeper understanding of the phenomenon being studied [ 14 ]. Husserl’s four steps of descriptive phenomenology were employed: bracketing, intuiting, analyzing and interpreting [ 15 ].

Participants and sampling

Sampling was done purposefully and participants were selected based on inclusion criteria. In this purposeful sampling, participants were selected among those patients who had sufficient knowledge about this phenomenon. The sample size was not determined at the beginning of the study, instead, it continued until no new idea emerged and data-saturated. Participants were selected from patients who were admitted to the Shohala Behavioral Diseases Counseling Center in Hamadan-Iran. The center has been set up to conduct tests, consultations, medical and dental services, and to distribute medicines among the patients. Additional inclusion criteria for selecting a participant are: having a positive diagnosis experience at the center, Ability to recall events and mental thoughts in the face of the first positive diagnosis of the disease, having psychological and mental stability, having a favorable clinical condition, willingness to work with the research team, and the possibility of re-access for the second interview if needed. Exclusion criteria were unwillingness to participate in the study and inability of verbal communication in Persian language.

Data collection

The interviews began with a non-structured question (tell us about your experience with a positive diagnosis) and continued with semi-structured questions. Each interview lasted 35–70 min and was conducted in two sessions if necessary. All interviews were conducted by the main investigator (ShZ) that who has experience in qualitative research and interviewing. The interview was recorded and then written down with permission of the participant.

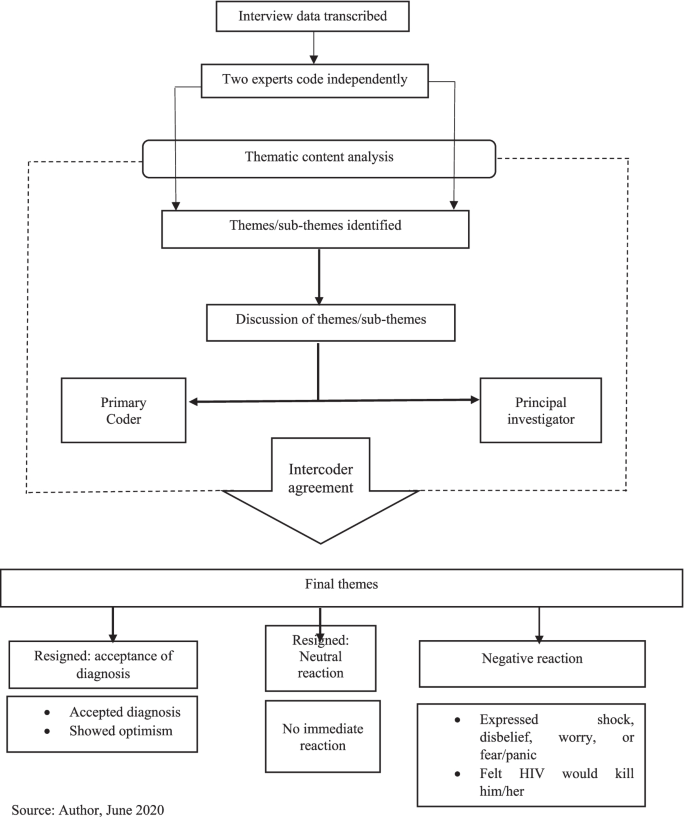

Data analysis

The descriptive Colaizzi method was used to analyses the collected data [ 16 ]. This method consists of seven steps: (1) collecting the participants’ descriptions, (2) understanding the meanings in depth, (3) extracting important sentences, (4) conceptualizing important themes, (5) categorizing the concepts and topics, (6) constructing comprehensive descriptions of the issues examined, and (7) validating the data following the four criteria set out by Lincoln and Guba.

Trustworthiness criteria were used to validate the research, due to the fact that importance of data and findings validity in qualitative research [ 17 ]. This study was based on four criteria of Lincoln and Guba: credibility, transferability, dependability, and conformability [ 18 ]. For data credibility, prolong engagement and follow-up observations, as well as samplings with maximum variability were used. For dependability of the data, the researchers were divided into two groups and the research was conducted as two separate studies. At the same time, another researcher with the most familiarity and ability in conducting qualitative research, supervised the study as an external observer. Concerning the conformability, the researchers tried not to influence their own opinions in the coding process. Moreover, the codes were readout by the participants as well as two researcher colleagues with the help of an independent researcher and expert familiar with qualitative research. Transferability of data was confirmed by offering a comprehensive description of the subject, participants, data collection, and data analysis.

Ethical considerations (ethical approval)

The present study was registered with the ethics code IR.UMSHA.REC.1398.1000 in Hamadan University of Medical Sciences. The purpose of the study was explained and all participants’ consents were obtained at first step. All participants were assured that the information obtained would remain confidential and no personal information would be disclosed. Participants were also told that there was no need to provide any personal information to the interviewer, including name, surname, phone number and address. To gain more trust, interviews were conducted by a person who was not resident of Hamadan and was not a native of the region, this case was also reported to the participants.

Twelve HIV-infected participated in this study. The mean age of the participants was 36.41 ± 4.12 years. 58.33% of the participants were male and 41.66% were married. Of these, 2 were illiterate, 2 had elementary diploma, 6 had high school diploma and 2 had academic education. Six of them were unemployed, 5 were self-employed and 1 was an official employee. These people had been infected by this disease for 6.08 ± 2.71 years, in average (Table 1 ).

Analysis of the HIV-infected patients’ experiences of facing the positive diagnosis of the disease by descriptive phenomenology revealed five main themes: emotional shock, the fear of the consequences, the feeling of the guilt, the discouragement, and the escape from reality (Table 2 ).

Emotional shock

Emotional shock is one of the unpleasant events that these patients have experienced after facing a positive diagnosis of the disease. This experience has manifested in loathing and motivation of social isolation.

These patients stated that after facing a positive diagnosis of the disease, they developed a strong inner feeling of hatred towards the source of infection. The patients feel hatred, since they hold the carrier as responsible for their infection. “…After realizing I was affected, I felt very upset with my husband, I did not want to see him again, because it made me miserable, I even decided to divorce ….”(P3).

Motivation of social isolation

The experiences of these patients showed that after facing the incident, they have suffered an internal failure that has caused them to try to distance from other people. These patients have become isolated, withdrawing from the community and sometimes even from their families. “…After this incident, I decided to live alone forever and stay away from all my family members. I made a good excuse and broke up our engagement…” (P7).

Fear of the consequences

Fear of the consequences is one of the unpleasant experiences that these patients will face, as soon as they receive a positive diagnosis of the disease. Based on experiences, these patients feel fear of loneliness, death, and disgrace as soon as they hear the positive diagnosis.

Fear of the death

The patients said that as soon as they got the positive test results, they thought that the disease was incurable and would end their lives soon. “…When I found I had AIDS, I was very upset and moved like a dead man because I was really afraid that at any moment this disease might kill me and I would die …” (P1).

Fear of loneliness

The participants stated that one of the feelings that they experienced as soon as they received a positive diagnosis of the disease was the fear of being alone. They stated that at that moment, the thought of being excluded from society and losing their intimacy with them was very disturbing. “…The thought that I could no longer have a family and had to stay single forever bothered me a lot, it was terrifying to me when I thought that society could no longer accept me as a normal person …” (P10).

Fear of disgrace

One of the feelings that these patients experienced when faced the positive diagnosis of the disease was the fear of disgrace. They suffer from the perception that the spread of news of the illness hurts the attitudes of those around them and causes them to be discredited. “…It was very annoying for me when I thought I would no longer be seen as a member of my family, I felt I would no longer have a reputation and everyone would think badly of me …” (P2).

Feeling of the guilt

From other experiences of these patients in facing the positive diagnosis of the disease is feeling guilty. This feeling appears in patients as feeling of regret, guilty and remorse.

Feeling of regret

These patients stated that they felt remorse for their lifestyle and actions as soon as they heard the positive diagnosis of the disease, because they thought that if they had lived healthier, they would not have been infected. “…After realizing this disease, I was very sorry for my past, because I really did not have a healthy life. I made a series of mistakes that caused me to get caught. At that moment, I just regretted why I had this disaster …” (P11).

Feeling guilty

The experience of these patients has shown that after receiving a positive diagnosis of the disease, they consider themselves guilty and complain about themselves. These patients condemn their lifestyle and sometimes even consider themselves deserving of the disease and think that it is a ransom that they have paid back. “…after getting the disease, I realized that I was paying the ransom because I was hundred percent guilty, I was the one who caused this situation with a series of bad deeds, and now I have to be punished …” (P5).

Feeling of conscience-stricken

One of the experiences that these patients reported is the pangs of conscience. These patients stated that after receiving a positive diagnosis of the disease, the thought that as a carrier they might have contaminated those around them was very unpleasant and greatly affected their psyche. “…after getting the disease. It was shocked and I was just crazy about the fact that if my wife and children had taken this disease from me, what would I do, I made them hapless … and this as very annoying for me …” (P8).

Discouragement

Discouragement is an unpleasant experience that patients experienced after receiving a positive HIV test results. Discouragement in these patients appears in the suicidal ideation and disappointment.

Suicidal ideation

The patients stated that they were so upset with the positive diagnosis of the illness and they immediately thought they could not live with the fact and the best thing to do was to end their own lives. “…The news was so bad for me that I immediately thought that if the test result was correct and I had AIDS, I would have to kill myself and end this wretch life, oh, I had a lot of problem and the thought of having to wait for a gradual death was horrible to me …” (P12).

Disappointment

The experience of these patients shows that a positive diagnosis of the disease for these patients leads to a destructive feeling of disappointment. So that they are completely discouraged from their lives. These patients think that their dreams and goals are vanished and that they have reached the end and everything is over. “…It was a horrible experience, so at that moment I felt my life was over, I had to prepare myself for a gradual death, I was at marriage ages when I thought I could no longer get married, I saw life as meaningless …” (P7).

Escape from reality

The lived experience of these patients shows that after receiving a positive diagnosis of the disease, they found that this fact was difficult to accept and somehow tried to escape from the reality. This experience has been in the form of denial and trying to hide from others.

One of the experiences of these patients in dealing with the positive test result of this disease has been to deny it. In this way, patients believed that the test result was wrong or that the result belonged to someone else. For this reason, the patients referred to other laboratories after receiving the first positive diagnosis of the disease. “…After the lab told me this and found out what the disease really was, I was really shocked and said it was impossible, it was definitely wrong and it is not true … I could not believe it at all, because I was a professional athlete and this could not happen to me. So I immediately went to a bigger city and there I went to a few laboratories for further tests …” (P6).

Trying to hide

These patients stated that after receiving the first positive diagnosis of the disease, they thought that no one should notice their disease and should remain anonymous as much as possible. “…I immediately decided that no one in my city should know that I got this disease and the news should not be spread anywhere, so I discard my phone number through which our city laboratory communicated with me and I came here to do a re-examination and go to the doctor, and after all these years, I always come here again for an examination …” (P4).

In this qualitative study, we attempted to discover lived experience of HIV-infected patients in the face of a positive diagnosis of the disease. Therefore, a descriptive phenomenological method was applied. As a result of this study, based on the experiences of the HIV-infected patients, the five main themes of emotional shock, fear of the consequences, feelings of guilt, discouragement and, escape from reality were obtained.

In this study, it was shown that the confrontation of these patients with the positive diagnosis of the disease causes them to experience a severe emotional shock. In this regard, Yangyang Qiu et al. [ 19 ] argued that anxiety and depression are very common among HIV-infected patients who have recently been diagnosed with the disease. The experience of the participants has shown that this emotional shock appears in the form of loathing and the motivation of social isolation. In fact, in these patients, the feeling of the loathing is an emotional response to the primary carrier that has infected them. The study of Imani et al. [ 20 ] have shown that decrease emotional intelligence in an environment where there is an HIV carrier, other people hate him/her, because they see him/her as a risk factor for their infection. The experience of the participants has also shown that receiving a positive diagnosis will motivate social isolation in these patients. Various studies have revealed that one of the consequences of AIDS/HIV that patients will suffer from, is social isolation [ 21 , 22 ].

Another experience of the participants, according to this study is fear of the consequences. This phenomenon appears in these patients as fear of the death, fear of loneliness, and fear of disgrace. Due to the nature of the disease, these patients feel an inner fear of premature death, as soon as they receive a positive diagnosis. In this regard, the study of Audrey K Miller et al. [ 23 ] showed that death anxiety in AIDS patients is a psychological complication. the participants have stated that they are very afraid of being alone after receiving a positive diagnosis, which is a natural feeling according to Keith Cherry and David H. Smith [ 24 ]; because these patients will mainly experience some degree of loneliness. HIV-infected patients also experienced a fear of disgrace, which will go back to the nature of the disease and people’s insight; but they should be aware that, as Newman Amy states, AIDS/ HIV is a disease, not a scandal [ 25 ].

Another experience of the participants in dealing with the positive diagnosis of the disease is guilt feeling. The patients will experience feelings of regret, the feeling guilty and feeling of the conscience-stricken. The experience of the participants shows that they regret their past. Earlier studies have also revealed that regret for the past is a common phenomenon among the patients living with HIV [ 26 , 27 , 28 ]. HIV-infected feel guilty while facing the positive diagnosis of the disease and consider themselves the main culprit of the situation. They often play a direct role in their infection, and their past lifestyle for sure [ 29 ]. Our study also found that these patients feel the conscience-stricken after a positive diagnosis, because they suspect that they may have infected people around them. This disease can be easily transmitted from the carrier to others if the health protocols are not followed [ 30 , 31 , 32 ].

Another experience of HIV-infected in dealing with the receiving a positive diagnosis of the disease is discouragement. These patients are disappointed and sometimes decide to suicide. Based on the lived experience of HIV-infected, it was found that receiving a positive diagnosis of the disease, will discourage them from life and patients will be disappointed in many aspects of life. Studies have shown that AIDS/HIV, as a crisis, will greatly reduce the patients' life expectancy and that they will continue to live in despair [ 33 ]. Studies also stated that they considered suicide as a solution to relieve stress when receiving a positive diagnosis. In this regard, various studies have emphasized that among the AIDS/HIV patients, loss of self-esteem and severe stress have led to high suicide rates [ 34 , 35 , 36 ].

According to the patients, trying to escape from reality is another phenomenon that they will experience. This phenomenon will occur in patients as denial and trying to hide the disease from others. Based on the lived experience of these patients, it was found that after facing a positive diagnosis, HIV-infected tend to deny that they are infected. In this regard, various studies have shown that AIDS/HIV patients in different stages of the disease and their lives try to deny it in different ways [ 37 , 38 , 39 ]. The HIV-infected also stated that at the beginning of the positive diagnosis of the disease, did not want others to know, so they wanted to hide themselves from others in any way possible. In this regard, Emilie Henry et al. [ 40 ] have shown that a high percentage of the patients living with AIDS/HIV have tried that others do not notice that they are ill.

One of the strengths of this study is the methodology of the study, because in this study, an attempt has been made to use descriptive phenomenology to explain the lived experience of HIV-infected patients when faced with a positive diagnosis of this disease. In fact, in this study, patients' experience of this particular situation was identified, and with careful analysis, the experiences of these people became codes and concepts, each of which can be a bridge that keeps the path of modern knowledge open to help these patients. One of the limitations of this study is the generalizability of the findings because patients’ experiences in different societies that have cultural, religious, subsistence, and economic differences can be different.

The results of this study showed that patients will experience unpleasant experiences in the face of receiving a positive diagnosis of the HIV. Patients’ unpleasant experiences at that moment include emotional shock, fear of the consequences, feeling guilty, discouragement and escape from reality. Therefore, medical and laboratory centers must pay attention to the patients' lived experience, and try to support the patients through education, counseling and other support programs to minimize the psychological trauma caused by the disease.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors through reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Hamadan Health Network, the Hamadan Shohada Behavioral Diseases Counseling Center, and the participants who helped us in this study.

The study was funded by Vice-chancellor for Research and Technology, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (No. 9812209934).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Operating Room, School of Paramedicine, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

Behzad Imani

Department of Operating Room, Student Research Committee, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

Shirdel Zandi

Research Center for Health Sciences, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

Salman khazaei

Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

Mohamad Mirzaei

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BI designed the study, collected the data, and provide the first draft of manuscript. ShZ designed the study and revised the manuscript. SKh participated in design of the study, the data collection, and revised the manuscript. MM participated in design of the study and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shirdel Zandi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study is the result of a student project that has been registered in Hamadan University of Medical Sciences of Iran with the ethical code IR.UMSHA.REC.1398.1000.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Imani, B., Zandi, S., khazaei, S. et al. The lived experience of HIV-infected patients in the face of a positive diagnosis of the disease: a phenomenological study. AIDS Res Ther 18 , 95 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-021-00421-4

Download citation

Received : 15 July 2021

Accepted : 26 November 2021

Published : 07 December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-021-00421-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Lived experience

- Phenomenological study

AIDS Research and Therapy

ISSN: 1742-6405

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- Español (Spanish)

HIV Overview

Hiv and aids clinical trials.

- A clinical trial is a research study in which people volunteer to help find answers to specific health questions. HIV and AIDS clinical trials help researchers find better ways to prevent, detect, or treat HIV and AIDS.

- Examples of HIV and AIDS clinical trials underway include studies of new HIV medicines, studies of vaccines to prevent or treat HIV, and studies of medicines to treat infections related to HIV and AIDS such as opportunistic infections .

- The details on the benefits and possible risks of participating in an HIV and AIDS clinical trial are explained to volunteers before they decide whether to participate in a study, through a process called an informed consent .

- Use the search feature on ClinicalTrials.gov to find HIV and AIDS studies looking for volunteer participants. Some HIV and AIDS clinical trials enroll only people who have HIV. Other studies enroll people who do not have HIV.

What is a clinical trial?

A clinical trial is a research study in which people volunteer to help find answers to specific health questions. These studies are conducted according to a plan, called a protocol, which include—

- New medicines or new combinations of medicines.

- New medical devices or surgical procedures.

- New, different ways to use an approved, existing medicine or device.

- New ways to change behaviors to improve health.

Clinical trials are conducted in several phases to determine whether new medical studies are safe and effective in people. Results from a Phase 1 Trial , Phase 2 Trial , and Phase 3 Trial are used to determine whether a new drug should be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for sale in the United States. Once a new drug is approved, researchers continue to track its safety in a Phase 4 Trial .

Interventional trial and observational trial are two main types of clinical trials:

- An interventional study tests (or tries out) an intervention—a potential drug or treatment, medical device, or procedure—in people. Interventional studies are often prospective and are specifically tailored to evaluate the direct effects of new drugs or treatments on disease.

- An observational study does not test potential treatments. Instead, researchers observe participants on their current treatment plan and track health outcomes. Observational studies (also called epidemiologic studies) are mostly retrospective .

What is an HIV and AIDS clinical trial?

HIV and AIDS clinical trials help researchers find better ways to prevent, detect, or treat HIV and AIDS. Every HIV medicine was first studied through clinical trials.

Examples of HIV and AIDS clinical trials include—

- studies of new medicines to prevent or treat HIV and AIDS.

- studies of vaccines to prevent or treat HIV.

- studies of medicines to treat infections related to HIV and AIDS, such as opportunistic infections.

Can anyone participate in an HIV and AIDS clinical trial?

Participation in a clinical trial depends on the study. Some HIV and AIDS clinical trials enroll only people who have HIV. Other studies include people who do not have HIV.

Participation in an HIV and AIDS clinical trial may also depend on other factors, such as age, gender, pregnancy, HIV treatment history, or other medical conditions.

What are the benefits of participating in an HIV and AIDS clinical trial?

Many people participate in HIV and AIDS clinical trials because they want to contribute to HIV and AIDS research. They may have HIV or know someone who has HIV.

People with HIV who participate in an HIV and AIDS clinical trial may benefit from new HIV medicines before they are widely available. HIV medicines being studied in clinical trials are called investigational drugs . To learn more, read the HIVinfo What is an Investigational HIV Drug? fact sheet.

Another benefit of participating in an HIV and AIDS clinical trial is that participants can receive regular and careful medical care from a research team that includes doctors and other health professionals. Often the medicines and medical care are free of charge.

Sometimes people get paid for participating in a clinical trial. For example, they may receive money or a gift card. They may be reimbursed for the cost of meals or transportation.

Are HIV and AIDS clinical trials safe?

Researchers try to make HIV and AIDS clinical trials as safe as possible. However, volunteering to participate in a study testing an experimental treatment for HIV can involve risks of varying degrees. Most volunteers do not experience serious side effects; however, potential side effects that may be serious or even life-threatening can occur from the treatment being studied.

Before enrolling in a clinical trial, potential volunteers learn about the study in a process called informed consent . The process includes an explanation of the possible risks and benefits of participating in the study.

The FDA believes that obtaining a research participant's written informed consent is only part of the process. Once enrolled in a study, people continue to receive information about the study through the informed consent process.

If a person decides to participate in an HIV and AIDS clinical trial, will their personal information be shared?

The privacy of study volunteers is very important to everyone involved in an HIV and AIDS clinical trial. The informed consent process includes an explanation of how a study volunteer’s personal information is protected.

How can one find an HIV and AIDS clinical trial looking for volunteer participants?

There are several ways to find an HIV and AIDS clinical trial searching for volunteer participants.

Use the find a case study search feature ClinicalTrials.gov to find HIV and AIDS studies looking for volunteer participants.

- Call a Clinicalinfo health information specialist at 1-800-448-0440 or email [email protected]

- Join ResearchMatch , which is a free, secure online tool that makes it easier for the public to become involved in clinical trials.

This fact sheet is based on information from the following sources:

From the National Institutes of Health (NIH):

- NIH Clinical Research Trials and You: The Basics

From the National Library of Medicine:

- Learn About Clinical Studies

From the Food and Drug Administration:

- Clinical Trials: What Patients Need to Know

- Informed Consent for Clinical Trials

Also see the HIV Source collection of HIV links and resources.

- Open access

- Published: 27 March 2023

A case study of HIV/AIDS services from community-based organizations during COVID-19 lockdown in China

- Jennifer Z.H. Bouey 1 , 2 ,

- Jing Han 3 ,

- Yuxuan Liu 1 ,

- Myriam Vuckovic 1 ,

- Keren Zhu 2 ,

- Kai Zhou 4 &

BMC Health Services Research volume 23 , Article number: 288 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2062 Accesses

2 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

Introduction

People living with HIV (PLHIV) relied on community-based organizations (CBOs) in accessing HIV care and support during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. However, little is known about the impact of, and challenges faced by Chinese CBOs supporting PLHIV during lockdowns.

A survey and interview study was conducted among 29 CBOs serving PLHIV in China between November 10 and November 23, 2020. Participants were asked to complete a 20-minute online survey on their routine operations, organizational capacity building, service provided, and challenges during the pandemic. A focus group interview was conducted with CBOs after the survey to gather CBOs’ policy recommendations. Survey data analysis was conducted using STATA 17.0 while qualitative data was examined using thematic analysis.

HIV-focused CBOs in China serve diverse clients including PLHIV, HIV high-risk groups, and the public. The scope of services provided is broad, ranging from HIV testing to peer support. All CBOs surveyed maintained their services during the pandemic, many by switching to online or hybrid mode. Many CBOs reported adding new clients and services, such as mailing medications. The top challenges faced by CBOs included service reduction due to staff shortage, lack of PPE for staff, and lack of operational funding during COVID-19 lockdowns in 2020. CBOs considered the ability to better network with other CBOs and other sectors (e.g., clinics, governments), a standard emergency response guideline, and ready strategies to help PLHIV build resilience to be critical for future emergency preparation.

Chinese CBOs serving vulnerable populations affected by HIV/AIDS are instrumental in building resilience in their communities during the COVID-19 pandemic, and they can play significant roles in providing uninterrupted services during emergencies by mobilizing resources, creating new services and operation methods, and utilizing existing networks. Chinese CBOs’ experiences, challenges, and their policy recommendations can inform policy makers on how to support future CBO capacity building to bridge service gaps during crises and reduce health inequalities in China and globally.

Peer Review reports

The COVID-19 pandemic is a defining catastrophic public health event of our lifetimes.In China, the COVID-19 pandemic started with a national lockdown in 2020. After two years of conservative intervention focusing on mass testing and quarantine, COVID-19 came back in 2022 and caused millions of infections and an overwhelming death toll, which put a significant strain on China’s healthcare system and paralyzed the economic engine. How do Chinese community organizations support vulnerable populations such as HIV/AIDS patients during such disasters? What policy changes do the Chinese CBOs hope to see? Our case study strives to answer these questions.

China was the first country to encounter the novel coronavirus disease and to implement a strict, large-scale lockdown between January 23, 2020, and April 2020 to contain the virus [ 1 , 2 ]. Most of the 31 provinces in China declared the highest Emergency Level on January 23rd of 2020, enabling local governments to employ social policing mechanisms to enforce quarantine and to close public events with crowd gatherings across the country. Most highways and public transportation were shut down (January 23- February 7) [ 2 ]. All businesses and recreational facilities were closed, except for medical emergency rooms, grocery stores, and keyinfrastructure-related economic activities. In rural areas, many villages stalled traffic and set up entrance checks, whereas urban residential communities required residents to prove their residence to use the weekly grocery shopping quota [ 3 ]. After the outbreak peaked in mid-February, many prefecture-level cities switched from the stringentshutdown to semi-lockdown for another month [ 4 ]. Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province and the origin of the outbreak, experienced the longest lockdown from January 21 to April 7, 2020 [ 5 ]. COVID-19 and the stringent intervention had a profound impact on the lives of the Chinese people during this initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic [ 6 , 7 ].

China is also home to 1.05 million people living with HIV (PLHIV) who needed long-term antiviral medical treatment and care in 2020 [ 8 ]. The central government provides PLHIVs access to free antiretroviral therapy (ART) and free voluntary counseling and testing since 2003 [ 9 ]. In 2016, the new “Treatment for All’’ policy removed the requirement of low CD4 levels as a treatment qualifier. By 2020, about 978,138 PLHIV had gained access to ART, covering 92.9% of all PLHIV in China [ 8 ]. Despite this progress and updated policies, various structural, psychological, and behavioral barriers to ART adherence persist [ 10 ]. Barriers including patients’ concerns for side effects and “pill burden,” lack of effective communication between patients and health care providers, low patient self-efficacy of ART, competing priorities for patients, and depression and stigma associated with HIV [ 11 , 12 ]. Like many Community-Based Organizations (CBO) serving vulnerable populations globally, Chinese CBOs play critical roles in helping PLHIV to improve their access to HIV screening, treatment and care, and reduce stigma, especially among men who have sex with men (MSM) [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. In China, there are two main types of CBOs providing services to PLHIV: those independently registered with the state/provincial or local government of Civil Affairs as a non-profit organization, and those affiliated with health clinics and local public health offices without an independent registry [ 17 ]. Both types of CBOs rely on government public health agencies for funding.

COVID-19 has led to unprecedented stress on health and public health systems and has intensified disruptions in HIV prevention, testing, and HIV care continuum services worldwide [ 18 ]. China is not an exception. A Chinese provincial study based on the HIV registration system found a 49% drop in HIV testing rates and a 37% drop in new HIV diagnoses during the first months of COVID-19. In addition, only half of the 475 newly diagnosed HIV patients underwent CD4 count testing and 28.6% did not receive routine linkage to care in the same time period [ 19 ].

Around the world,PLHIV and high-risk populations rely on CBOs for their rich local knowledge, operational flexibility, and direct contact to people in need, to provide humanitarian aid during a crisis [ 20 ]. Facing challenges due to quarantine requirements and transportation service requirements, CBOs in many countries responded by moving their services online and utilizing technology-driven solutions to promote access to HIV counseling, testing, and treatment [ 21 ]. Global [ 22 , 23 ] and China-specific [ 24 ] studies have shown that CBOs promoting community connectedness among MSM resulted in higher HIV testing rates during COIVD-19. However, CBOs themselves are not immune to the negative impact of COVID-19. Preliminary studies in the U.S. have found that the COVID-19 pandemic presents multifaceted challenges to CBOs providing HIV services, including but not limited to structural inequality, resources shortages, and disruption to patient-centered services provision [ 25 , 26 ].