17 Essay Conclusion Examples (Copy and Paste)

Essay conclusions are not just extra filler. They are important because they tie together your arguments, then give you the chance to forcefully drive your point home.

I created the 5 Cs conclusion method to help you write essay conclusions:

I’ve previously produced the video below on how to write a conclusion that goes over the above image.

The video follows the 5 C’s method ( you can read about it in this post ), which doesn’t perfectly match each of the below copy-and-paste conclusion examples, but the principles are similar, and can help you to write your own strong conclusion:

💡 New! Try this AI Prompt to Generate a Sample 5Cs Conclusion This is my essay: [INSERT ESSAY WITHOUT THE CONCLUSION]. I want you to write a conclusion for this essay. In the first sentence of the conclusion, return to a statement I made in the introduction. In the second sentence, reiterate the thesis statement I have used. In the third sentence, clarify how my final position is relevant to the Essay Question, which is [ESSAY QUESTION]. In the fourth sentence, explain who should be interested in my findings. In the fifth sentence, end by noting in one final, engaging sentence why this topic is of such importance.

Remember: The prompt can help you generate samples but you can’t submit AI text for assessment. Make sure you write your conclusion in your own words.

Essay Conclusion Examples

Below is a range of copy-and-paste essay conclusions with gaps for you to fill-in your topic and key arguments. Browse through for one you like (there are 17 for argumentative, expository, compare and contrast, and critical essays). Once you’ve found one you like, copy it and add-in the key points to make it your own.

1. Argumentative Essay Conclusions

The arguments presented in this essay demonstrate the significant importance of _____________. While there are some strong counterarguments, such as ____________, it remains clear that the benefits/merits of _____________ far outweigh the potential downsides. The evidence presented throughout the essay strongly support _____________. In the coming years, _____________ will be increasingly important. Therefore, continual advocacy for the position presented in this essay will be necessary, especially due to its significant implications for _____________.

Version 1 Filled-In

The arguments presented in this essay demonstrate the significant importance of fighting climate change. While there are some strong counterarguments, such as the claim that it is too late to stop catastrophic change, it remains clear that the merits of taking drastic action far outweigh the potential downsides. The evidence presented throughout the essay strongly support the claim that we can at least mitigate the worst effects. In the coming years, intergovernmental worldwide agreements will be increasingly important. Therefore, continual advocacy for the position presented in this essay will be necessary, especially due to its significant implications for humankind.

As this essay has shown, it is clear that the debate surrounding _____________ is multifaceted and highly complex. While there are strong arguments opposing the position that _____________, there remains overwhelming evidence to support the claim that _____________. A careful analysis of the empirical evidence suggests that _____________ not only leads to ____________, but it may also be a necessity for _____________. Moving forward, _____________ should be a priority for all stakeholders involved, as it promises a better future for _____________. The focus should now shift towards how best to integrate _____________ more effectively into society.

Version 2 Filled-In

As this essay has shown, it is clear that the debate surrounding climate change is multifaceted and highly complex. While there are strong arguments opposing the position that we should fight climate change, there remains overwhelming evidence to support the claim that action can mitigate the worst effects. A careful analysis of the empirical evidence suggests that strong action not only leads to better economic outcomes in the long term, but it may also be a necessity for preventing climate-related deaths. Moving forward, carbon emission mitigation should be a priority for all stakeholders involved, as it promises a better future for all. The focus should now shift towards how best to integrate smart climate policies more effectively into society.

Based upon the preponderance of evidence, it is evident that _____________ holds the potential to significantly alter/improve _____________. The counterarguments, while noteworthy, fail to diminish the compelling case for _____________. Following an examination of both sides of the argument, it has become clear that _____________ presents the most effective solution/approach to _____________. Consequently, it is imperative that society acknowledge the value of _____________ for developing a better _____________. Failing to address this topic could lead to negative outcomes, including _____________.

Version 3 Filled-In

Based upon the preponderance of evidence, it is evident that addressing climate change holds the potential to significantly improve the future of society. The counterarguments, while noteworthy, fail to diminish the compelling case for immediate climate action. Following an examination of both sides of the argument, it has become clear that widespread and urgent social action presents the most effective solution to this pressing problem. Consequently, it is imperative that society acknowledge the value of taking immediate action for developing a better environment for future generations. Failing to address this topic could lead to negative outcomes, including more extreme climate events and greater economic externalities.

See Also: Examples of Counterarguments

On the balance of evidence, there is an overwhelming case for _____________. While the counterarguments offer valid points that are worth examining, they do not outweigh or overcome the argument that _____________. An evaluation of both perspectives on this topic concludes that _____________ is the most sufficient option for _____________. The implications of embracing _____________ do not only have immediate benefits, but they also pave the way for a more _____________. Therefore, the solution of _____________ should be actively pursued by _____________.

Version 4 Filled-In

On the balance of evidence, there is an overwhelming case for immediate tax-based action to mitigate the effects of climate change. While the counterarguments offer valid points that are worth examining, they do not outweigh or overcome the argument that action is urgently necessary. An evaluation of both perspectives on this topic concludes that taking societal-wide action is the most sufficient option for achieving the best results. The implications of embracing a society-wide approach like a carbon tax do not only have immediate benefits, but they also pave the way for a more healthy future. Therefore, the solution of a carbon tax or equivalent policy should be actively pursued by governments.

2. Expository Essay Conclusions

Overall, it is evident that _____________ plays a crucial role in _____________. The analysis presented in this essay demonstrates the clear impact of _____________ on _____________. By understanding the key facts about _____________, practitioners/society are better equipped to navigate _____________. Moving forward, further exploration of _____________ will yield additional insights and information about _____________. As such, _____________ should remain a focal point for further discussions and studies on _____________.

Overall, it is evident that social media plays a crucial role in harming teenagers’ mental health. The analysis presented in this essay demonstrates the clear impact of social media on young people. By understanding the key facts about the ways social media cause young people to experience body dysmorphia, teachers and parents are better equipped to help young people navigate online spaces. Moving forward, further exploration of the ways social media cause harm will yield additional insights and information about how it can be more sufficiently regulated. As such, the effects of social media on youth should remain a focal point for further discussions and studies on youth mental health.

To conclude, this essay has explored the multi-faceted aspects of _____________. Through a careful examination of _____________, this essay has illuminated its significant influence on _____________. This understanding allows society to appreciate the idea that _____________. As research continues to emerge, the importance of _____________ will only continue to grow. Therefore, an understanding of _____________ is not merely desirable, but imperative for _____________.

To conclude, this essay has explored the multi-faceted aspects of globalization. Through a careful examination of globalization, this essay has illuminated its significant influence on the economy, cultures, and society. This understanding allows society to appreciate the idea that globalization has both positive and negative effects. As research continues to emerge, the importance of studying globalization will only continue to grow. Therefore, an understanding of globalization’s effects is not merely desirable, but imperative for judging whether it is good or bad.

Reflecting on the discussion, it is clear that _____________ serves a pivotal role in _____________. By delving into the intricacies of _____________, we have gained valuable insights into its impact and significance. This knowledge will undoubtedly serve as a guiding principle in _____________. Moving forward, it is paramount to remain open to further explorations and studies on _____________. In this way, our understanding and appreciation of _____________ can only deepen and expand.

Reflecting on the discussion, it is clear that mass media serves a pivotal role in shaping public opinion. By delving into the intricacies of mass media, we have gained valuable insights into its impact and significance. This knowledge will undoubtedly serve as a guiding principle in shaping the media landscape. Moving forward, it is paramount to remain open to further explorations and studies on how mass media impacts society. In this way, our understanding and appreciation of mass media’s impacts can only deepen and expand.

In conclusion, this essay has shed light on the importance of _____________ in the context of _____________. The evidence and analysis provided underscore the profound effect _____________ has on _____________. The knowledge gained from exploring _____________ will undoubtedly contribute to more informed and effective decisions in _____________. As we continue to progress, the significance of understanding _____________ will remain paramount. Hence, we should strive to deepen our knowledge of _____________ to better navigate and influence _____________.

In conclusion, this essay has shed light on the importance of bedside manner in the context of nursing. The evidence and analysis provided underscore the profound effect compassionate bedside manner has on patient outcome. The knowledge gained from exploring nurses’ bedside manner will undoubtedly contribute to more informed and effective decisions in nursing practice. As we continue to progress, the significance of understanding nurses’ bedside manner will remain paramount. Hence, we should strive to deepen our knowledge of this topic to better navigate and influence patient outcomes.

See More: How to Write an Expository Essay

3. Compare and Contrast Essay Conclusion

While both _____________ and _____________ have similarities such as _____________, they also have some very important differences in areas like _____________. Through this comparative analysis, a broader understanding of _____________ and _____________ has been attained. The choice between the two will largely depend on _____________. For example, as highlighted in the essay, ____________. Despite their differences, both _____________ and _____________ have value in different situations.

While both macrosociology and microsociology have similarities such as their foci on how society is structured, they also have some very important differences in areas like their differing approaches to research methodologies. Through this comparative analysis, a broader understanding of macrosociology and microsociology has been attained. The choice between the two will largely depend on the researcher’s perspective on how society works. For example, as highlighted in the essay, microsociology is much more concerned with individuals’ experiences while macrosociology is more concerned with social structures. Despite their differences, both macrosociology and microsociology have value in different situations.

It is clear that _____________ and _____________, while seeming to be different, have shared characteristics in _____________. On the other hand, their contrasts in _____________ shed light on their unique features. The analysis provides a more nuanced comprehension of these subjects. In choosing between the two, consideration should be given to _____________. Despite their disparities, it’s crucial to acknowledge the importance of both when it comes to _____________.

It is clear that behaviorism and consructivism, while seeming to be different, have shared characteristics in their foci on knowledge acquisition over time. On the other hand, their contrasts in ideas about the role of experience in learning shed light on their unique features. The analysis provides a more nuanced comprehension of these subjects. In choosing between the two, consideration should be given to which approach works best in which situation. Despite their disparities, it’s crucial to acknowledge the importance of both when it comes to student education.

Reflecting on the points discussed, it’s evident that _____________ and _____________ share similarities such as _____________, while also demonstrating unique differences, particularly in _____________. The preference for one over the other would typically depend on factors such as _____________. Yet, regardless of their distinctions, both _____________ and _____________ play integral roles in their respective areas, significantly contributing to _____________.

Reflecting on the points discussed, it’s evident that red and orange share similarities such as the fact they are both ‘hot colors’, while also demonstrating unique differences, particularly in their social meaning (red meaning danger and orange warmth). The preference for one over the other would typically depend on factors such as personal taste. Yet, regardless of their distinctions, both red and orange play integral roles in their respective areas, significantly contributing to color theory.

Ultimately, the comparison and contrast of _____________ and _____________ have revealed intriguing similarities and notable differences. Differences such as _____________ give deeper insights into their unique and shared qualities. When it comes to choosing between them, _____________ will likely be a deciding factor. Despite these differences, it is important to remember that both _____________ and _____________ hold significant value within the context of _____________, and each contributes to _____________ in its own unique way.

Ultimately, the comparison and contrast of driving and flying have revealed intriguing similarities and notable differences. Differences such as their differing speed to destination give deeper insights into their unique and shared qualities. When it comes to choosing between them, urgency to arrive at the destination will likely be a deciding factor. Despite these differences, it is important to remember that both driving and flying hold significant value within the context of air transit, and each contributes to facilitating movement in its own unique way.

See Here for More Compare and Contrast Essay Examples

4. Critical Essay Conclusion

In conclusion, the analysis of _____________ has unveiled critical aspects related to _____________. While there are strengths in _____________, its limitations are equally telling. This critique provides a more informed perspective on _____________, revealing that there is much more beneath the surface. Moving forward, the understanding of _____________ should evolve, considering both its merits and flaws.

In conclusion, the analysis of flow theory has unveiled critical aspects related to motivation and focus. While there are strengths in achieving a flow state, its limitations are equally telling. This critique provides a more informed perspective on how humans achieve motivation, revealing that there is much more beneath the surface. Moving forward, the understanding of flow theory of motivation should evolve, considering both its merits and flaws.

To conclude, this critical examination of _____________ sheds light on its multi-dimensional nature. While _____________ presents notable advantages, it is not without its drawbacks. This in-depth critique offers a comprehensive understanding of _____________. Therefore, future engagements with _____________ should involve a balanced consideration of its strengths and weaknesses.

To conclude, this critical examination of postmodern art sheds light on its multi-dimensional nature. While postmodernism presents notable advantages, it is not without its drawbacks. This in-depth critique offers a comprehensive understanding of how it has contributed to the arts over the past 50 years. Therefore, future engagements with postmodern art should involve a balanced consideration of its strengths and weaknesses.

Upon reflection, the critique of _____________ uncovers profound insights into its underlying intricacies. Despite its positive aspects such as ________, it’s impossible to overlook its shortcomings. This analysis provides a nuanced understanding of _____________, highlighting the necessity for a balanced approach in future interactions. Indeed, both the strengths and weaknesses of _____________ should be taken into account when considering ____________.

Upon reflection, the critique of marxism uncovers profound insights into its underlying intricacies. Despite its positive aspects such as its ability to critique exploitation of labor, it’s impossible to overlook its shortcomings. This analysis provides a nuanced understanding of marxism’s harmful effects when used as an economic theory, highlighting the necessity for a balanced approach in future interactions. Indeed, both the strengths and weaknesses of marxism should be taken into account when considering the use of its ideas in real life.

Ultimately, this critique of _____________ offers a detailed look into its advantages and disadvantages. The strengths of _____________ such as __________ are significant, yet its limitations such as _________ are not insignificant. This balanced analysis not only offers a deeper understanding of _____________ but also underscores the importance of critical evaluation. Hence, it’s crucial that future discussions around _____________ continue to embrace this balanced approach.

Ultimately, this critique of artificial intelligence offers a detailed look into its advantages and disadvantages. The strengths of artificial intelligence, such as its ability to improve productivity are significant, yet its limitations such as the possibility of mass job losses are not insignificant. This balanced analysis not only offers a deeper understanding of artificial intelligence but also underscores the importance of critical evaluation. Hence, it’s crucial that future discussions around the regulation of artificial intelligence continue to embrace this balanced approach.

This article promised 17 essay conclusions, and this one you are reading now is the twenty-first. This last conclusion demonstrates that the very best essay conclusions are written uniquely, from scratch, in order to perfectly cater the conclusion to the topic. A good conclusion will tie together all the key points you made in your essay and forcefully drive home the importance or relevance of your argument, thesis statement, or simply your topic so the reader is left with one strong final point to ponder.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

How to Write a Psychology Essay

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Before you write your essay, it’s important to analyse the task and understand exactly what the essay question is asking. Your lecturer may give you some advice – pay attention to this as it will help you plan your answer.

Next conduct preliminary reading based on your lecture notes. At this stage, it’s not crucial to have a robust understanding of key theories or studies, but you should at least have a general “gist” of the literature.

After reading, plan a response to the task. This plan could be in the form of a mind map, a summary table, or by writing a core statement (which encompasses the entire argument of your essay in just a few sentences).

After writing your plan, conduct supplementary reading, refine your plan, and make it more detailed.

It is tempting to skip these preliminary steps and write the first draft while reading at the same time. However, reading and planning will make the essay writing process easier, quicker, and ensure a higher quality essay is produced.

Components of a Good Essay

Now, let us look at what constitutes a good essay in psychology. There are a number of important features.

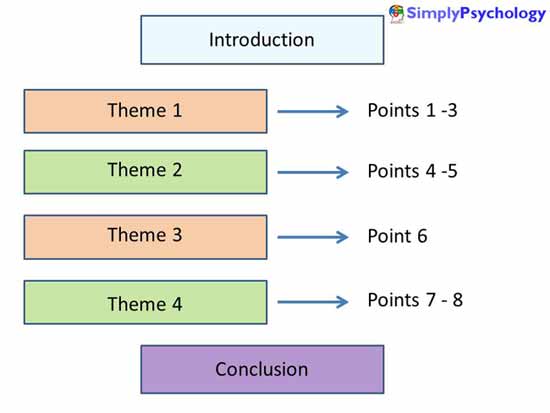

- Global Structure – structure the material to allow for a logical sequence of ideas. Each paragraph / statement should follow sensibly from its predecessor. The essay should “flow”. The introduction, main body and conclusion should all be linked.

- Each paragraph should comprise a main theme, which is illustrated and developed through a number of points (supported by evidence).

- Knowledge and Understanding – recognize, recall, and show understanding of a range of scientific material that accurately reflects the main theoretical perspectives.

- Critical Evaluation – arguments should be supported by appropriate evidence and/or theory from the literature. Evidence of independent thinking, insight, and evaluation of the evidence.

- Quality of Written Communication – writing clearly and succinctly with appropriate use of paragraphs, spelling, and grammar. All sources are referenced accurately and in line with APA guidelines.

In the main body of the essay, every paragraph should demonstrate both knowledge and critical evaluation.

There should also be an appropriate balance between these two essay components. Try to aim for about a 60/40 split if possible.

Most students make the mistake of writing too much knowledge and not enough evaluation (which is the difficult bit).

It is best to structure your essay according to key themes. Themes are illustrated and developed through a number of points (supported by evidence).

Choose relevant points only, ones that most reveal the theme or help to make a convincing and interesting argument.

Knowledge and Understanding

Remember that an essay is simply a discussion / argument on paper. Don’t make the mistake of writing all the information you know regarding a particular topic.

You need to be concise, and clearly articulate your argument. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences.

Each paragraph should have a purpose / theme, and make a number of points – which need to be support by high quality evidence. Be clear why each point is is relevant to the argument. It would be useful at the beginning of each paragraph if you explicitly outlined the theme being discussed (.e.g. cognitive development, social development etc.).

Try not to overuse quotations in your essays. It is more appropriate to use original content to demonstrate your understanding.

Psychology is a science so you must support your ideas with evidence (not your own personal opinion). If you are discussing a theory or research study make sure you cite the source of the information.

Note this is not the author of a textbook you have read – but the original source / author(s) of the theory or research study.

For example:

Bowlby (1951) claimed that mothering is almost useless if delayed until after two and a half to three years and, for most children, if delayed till after 12 months, i.e. there is a critical period.

Maslow (1943) stated that people are motivated to achieve certain needs. When one need is fulfilled a person seeks to fullfil the next one, and so on.

As a general rule, make sure there is at least one citation (i.e. name of psychologist and date of publication) in each paragraph.

Remember to answer the essay question. Underline the keywords in the essay title. Don’t make the mistake of simply writing everything you know of a particular topic, be selective. Each paragraph in your essay should contribute to answering the essay question.

Critical Evaluation

In simple terms, this means outlining the strengths and limitations of a theory or research study.

There are many ways you can critically evaluate:

Methodological evaluation of research

Is the study valid / reliable ? Is the sample biased, or can we generalize the findings to other populations? What are the strengths and limitations of the method used and data obtained?

Be careful to ensure that any methodological criticisms are justified and not trite.

Rather than hunting for weaknesses in every study; only highlight limitations that make you doubt the conclusions that the authors have drawn – e.g., where an alternative explanation might be equally likely because something hasn’t been adequately controlled.

Compare or contrast different theories

Outline how the theories are similar and how they differ. This could be two (or more) theories of personality / memory / child development etc. Also try to communicate the value of the theory / study.

Debates or perspectives

Refer to debates such as nature or nurture, reductionism vs. holism, or the perspectives in psychology . For example, would they agree or disagree with a theory or the findings of the study?

What are the ethical issues of the research?

Does a study involve ethical issues such as deception, privacy, psychological or physical harm?

Gender bias

If research is biased towards men or women it does not provide a clear view of the behavior that has been studied. A dominantly male perspective is known as an androcentric bias.

Cultural bias

Is the theory / study ethnocentric? Psychology is predominantly a white, Euro-American enterprise. In some texts, over 90% of studies have US participants, who are predominantly white and middle class.

Does the theory or study being discussed judge other cultures by Western standards?

Animal Research

This raises the issue of whether it’s morally and/or scientifically right to use animals. The main criterion is that benefits must outweigh costs. But benefits are almost always to humans and costs to animals.

Animal research also raises the issue of extrapolation. Can we generalize from studies on animals to humans as their anatomy & physiology is different from humans?

The PEC System

It is very important to elaborate on your evaluation. Don’t just write a shopping list of brief (one or two sentence) evaluation points.

Instead, make sure you expand on your points, remember, quality of evaluation is most important than quantity.

When you are writing an evaluation paragraph, use the PEC system.

- Make your P oint.

- E xplain how and why the point is relevant.

- Discuss the C onsequences / implications of the theory or study. Are they positive or negative?

For Example

- Point: It is argued that psychoanalytic therapy is only of benefit to an articulate, intelligent, affluent minority.

- Explain: Because psychoanalytic therapy involves talking and gaining insight, and is costly and time-consuming, it is argued that it is only of benefit to an articulate, intelligent, affluent minority. Evidence suggests psychoanalytic therapy works best if the client is motivated and has a positive attitude.

- Consequences: A depressed client’s apathy, flat emotional state, and lack of motivation limit the appropriateness of psychoanalytic therapy for depression.

Furthermore, the levels of dependency of depressed clients mean that transference is more likely to develop.

Using Research Studies in your Essays

Research studies can either be knowledge or evaluation.

- If you refer to the procedures and findings of a study, this shows knowledge and understanding.

- If you comment on what the studies shows, and what it supports and challenges about the theory in question, this shows evaluation.

Writing an Introduction

It is often best to write your introduction when you have finished the main body of the essay, so that you have a good understanding of the topic area.

If there is a word count for your essay try to devote 10% of this to your introduction.

Ideally, the introduction should;

Identify the subject of the essay and define the key terms. Highlight the major issues which “lie behind” the question. Let the reader know how you will focus your essay by identifying the main themes to be discussed. “Signpost” the essay’s key argument, (and, if possible, how this argument is structured).

Introductions are very important as first impressions count and they can create a h alo effect in the mind of the lecturer grading your essay. If you start off well then you are more likely to be forgiven for the odd mistake later one.

Writing a Conclusion

So many students either forget to write a conclusion or fail to give it the attention it deserves.

If there is a word count for your essay try to devote 10% of this to your conclusion.

Ideally the conclusion should summarize the key themes / arguments of your essay. State the take home message – don’t sit on the fence, instead weigh up the evidence presented in the essay and make a decision which side of the argument has more support.

Also, you might like to suggest what future research may need to be conducted and why (read the discussion section of journal articles for this).

Don”t include new information / arguments (only information discussed in the main body of the essay).

If you are unsure of what to write read the essay question and answer it in one paragraph.

Points that unite or embrace several themes can be used to great effect as part of your conclusion.

The Importance of Flow

Obviously, what you write is important, but how you communicate your ideas / arguments has a significant influence on your overall grade. Most students may have similar information / content in their essays, but the better students communicate this information concisely and articulately.

When you have finished the first draft of your essay you must check if it “flows”. This is an important feature of quality of communication (along with spelling and grammar).

This means that the paragraphs follow a logical order (like the chapters in a novel). Have a global structure with themes arranged in a way that allows for a logical sequence of ideas. You might want to rearrange (cut and paste) paragraphs to a different position in your essay if they don”t appear to fit in with the essay structure.

To improve the flow of your essay make sure the last sentence of one paragraph links to first sentence of the next paragraph. This will help the essay flow and make it easier to read.

Finally, only repeat citations when it is unclear which study / theory you are discussing. Repeating citations unnecessarily disrupts the flow of an essay.

Referencing

The reference section is the list of all the sources cited in the essay (in alphabetical order). It is not a bibliography (a list of the books you used).

In simple terms every time you cite/refer to a name (and date) of a psychologist you need to reference the original source of the information.

If you have been using textbooks this is easy as the references are usually at the back of the book and you can just copy them down. If you have been using websites, then you may have a problem as they might not provide a reference section for you to copy.

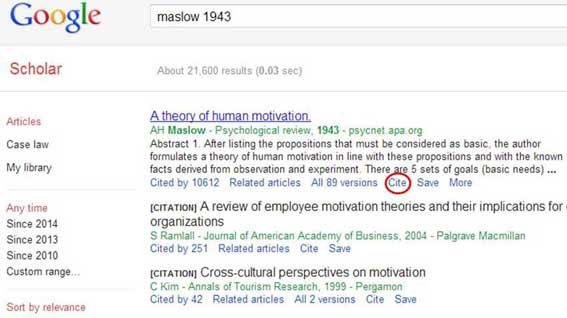

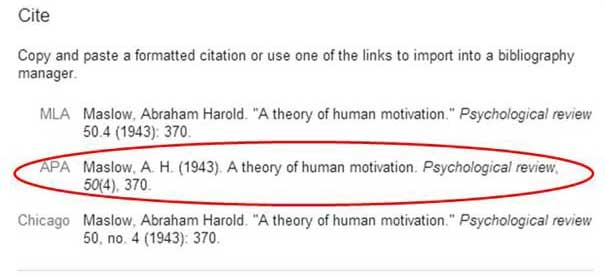

References need to be set out APA style :

Author, A. A. (year). Title of work . Location: Publisher.

Journal Articles

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (year). Article title. Journal Title, volume number (issue number), page numbers

A simple way to write your reference section is use Google scholar . Just type the name and date of the psychologist in the search box and click on the “cite” link.

Next, copy and paste the APA reference into the reference section of your essay.

Once again, remember that references need to be in alphabetical order according to surname.

How to Write a Conclusion of a Psychology Essay with an Example

A conclusion is an essential component of a psychology essay. It restates the main argument of your essay and helps to a lasting impression your reader. Let us dive in and learn how to create impactful conclusions within a short period without having to use a language model.

Table of Contents

Introduction

In the structure of a psychology essay, a conclusion is an essential component. Firstly, it serves to restate the main points that were covered in the essay using the shortest number of words possible. Secondly, it presents an opportunity to develop recommendations and reflections on the implications of your argument for psychology practice. A conclusion should not have in-text citations, as no new information is presented. Here, as a student, you are supposed to synthesize the main points, showing your comprehensive understanding of the topic. In this short post, I am going to show you how to write a conclusion of a psychology essay. I will discuss the recommended length, the steps you should follow and provide an example.

What is the length of a psychology essay conclusion?

The conclusion length of a psychology essay depends on the length of your whole paper. Whilst answering this question, Robin Turner, who was a former English lecturer at Bilkent University, states, “You don’t want your conclusion to be more than a fifth of your essay,” which translates to 20% of your essay. However, in my undergraduate and master’s psychology university education, the rule of thumb was that your conclusion should be 10% of the total word count limit. That is the case for most universities globally. We normally advise that you keep it at 10% of your essay’s total word count.

What are the steps for writing a conclusion for a psychology essay?

Restate your specific thesis statement. This involves linking back to the question that your essay was seeking to answer. There is an ongoing debate if you should use the phrase “in conclusion.” While answering this question, Ali Mullin, who is an instructor at Louisiana State University terms ending your conclusion with the phrase as being reductionist. She suggested the use of such styles as “[idea 1], [idea 2], and [idea 3] all illustrate [concept/argument]. Considering these [ideas] synthesizes/realizes/proves my point that [argument]. In the future, I hope to see [idea]”.

Summarize and synthesize the main points that were discussed in the essay, showing great mastery of the topic that you discussed.

Present your conclusion from the point of view of the conclusion that you provided, linking it to the main argument of your essay.

Finally, provide a broad statement that suggests how your conclusion impacts, is related, or is essential in practice.

For more information on h0w to write other parts of a psychology essay, check out our comprehensive guide .

Concisely, human beings use both the exemplar and prototype theories as framework for categorizing concepts. Even though both theories are essential, they are varied in their manner of application since the prototypes are appropriate for simple and hierarchical categories. On other hand, exemplars are suitable for flat and nuanced domains. Cultural differences in relation to various concepts such as classification of fruits and leadership shape categorization affecting prototypes and how conclusions are made in relation to specific examples. By harnessing both prototype and exemplar perspectives, people can optimize learning and creativity, drawing upon existing knowledge to navigate new terrain.

The first sentence restates the thesis statement.

The second and third sentences synthesizes the main points that were developed in the paper.

The last sentence is a broad statement regarding the argument that the essay makes.

It is worth noting that we discourage the use of language models in your psychology essay. However, you can use AI specifically Gemini to develop your conclusion.

We highly recommend seeking help from our psychology assignment experts .

Affordable Psychology Essay Writing Service

Provide your paper details using our intuitive form and find out how much our psychology essay help will cost you. Note that the price of your order will depend on the number of pages, deadline, and the academic level. If your place your order with us early enough, the price will be much lower, and our experts will have enough time to craft an excellent paper for you. We are currently offering 25% OFF discount for not only new customers but also new ones.

- Formatting (MLA, APA, Chicago, custom, etc.)

- Title page & bibliography

- 24/7 customer support

- Amendments to your paper when they are needed

- Chat with your writer

- 275 word/double-spaced page

- 12 point Arial/Times New Roman

- Double, single, and custom spacing

We have a strict policy against plagiarism. We always screen delivered psychology assignments using Turnitin before you receive them because it is the most used and trusted software by universities globally. Your university will use Turnitin AI detector to screen your written assignment. Our writers understand that using AI to produce content is frowned upon and anyone caught doing that is expelled from our platform.

Our service is General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and U.S. Data Privacy Protection Laws compliant. Therefore, your personal information such as credit cards and personal identification information such as email and phone number will not be shared with third parties. Even our writers do not have access to this information.

You can stay rest assured that you will get value for your money. In case your plans change and feel that you no longer need our services, you will get a refund as soon as possible.

How to Order

- 1 Fill the Order Form Fill out the details of your paper using our user-friendly and intuitive order form. The details should include the academic level, the type of paper, the number of words, your preferred deadline, and the writer level that best suits your needs and expectations. After providing all the necessary details, including additional materials, leave it to us at this point.

- 2 We find you an expert Our 24/7-available support team will receive your paid order. We will choose you the most suitable expert for your psychology paper. We consider the following factors in our writer selection criteria: (a) the academic level of the order, (b) the subject of your order, and (c) the urgency. The writer will start working on your order as soon as possible. We have a culture of delivering papers ahead of time without compromising quality, demonstrating our imppecable commitment towards customer satisfaction.

- 3 You get the paper done Immediately the customer delivers the order, you will receive a notification email containing the final paper. You can also login to your portal to download additional files, such as the plagiarism report and the AI-free content screenshot.

Samples of Psychology Essay Writing Help From Our Advanced Writers

Check out some psychology essay pieces from our best writers before you decide to buy a psychology paper from us. They will help you better understand the kind of psychology essay help we offer.

- Lab Report Psychology Lab Report Example: Brain Cerebral Hemispheres Laterality- Dowel Rod Experiment Master's Psychology APA View this sample

- Case study Analysis of Common Alcohol Screening Tools Undergrad. (yrs 3-4) Psychology APA View this sample

- Coursework Critique of Western Approaches to Psychological Science Master's Psychology APA View this sample

- Term paper Challenges of Supporting Mental Health Patients in the Community Undergrad. (yrs 3-4) Psychology APA View this sample

- Term paper To what extent does Social Psychology Contribute to our Understanding of Current Events Master's Psychology APA View this sample

- Research paper Patient Centered Care and Dementia Master's Psychology APA View this sample

- Research paper Age and Belongingness Master's Psychology APA View this sample

- Essay (any type) Prolonged Grief Disorder Undergrad. (yrs 1-2) Psychology APA View this sample

- Essay (any type) Five-Factor Personality Model vs The Six-Factor Personality Model Undergrad. (yrs 3-4) Psychology APA View this sample

- Essay (any type) Counselling Session and Person-Centered Approach Master's Psychology APA View this sample

- Essay (any type) Psychosocial Development Theories Undergrad. (yrs 3-4) Psychology APA View this sample

- Essay (any type) Student Bias Against Female Instructors Undergrad. (yrs 3-4) Psychology APA View this sample

- Essay (any type) Personal Construct Theory Undergrad. (yrs 1-2) Psychology APA View this sample

- Essay (any type) Can Personality Predict a Person's Risk of Psychological Distress Undergrad. (yrs 3-4) Psychology APA View this sample

Get your own paper from top experts

Benefits of our psychology essay writing service.

We offer more than more than customized psychology papers. Here are more of our greatest perks.

- Confidentiality and Privacy Your identifying information, such as email address and phone number will not be shared with any third party under whatever circumstance.

- Timely Updates We will send you regular updates regarding the progress of your order at any given time.

- Free Originality Reports Our service strives to give our customers plagiarism-free papers, 100% human-written.

- 100% Human Content Guaranteed Besides giving you a free plagiarism/Turnitin report, we will also provide you with a TurnItIn AI screenshot.

- Unlimited Revisions Ask improvements to your completed paper unlimited times.

- 24/7 Support We typically reply within a few minutes at any time of the day or day of week.

Take your studies to the next level with our experienced Psychology Experts

4 Chapter 1. Conclusions

In conclusion, the first chapter of this textbook has provided you with a glimpse into the multifaceted nature of the field of psychology. We have explored the fundamental question of “What is Psychology?” and have discussed its diverse subfields and applications. Moreover, we have delved into the rich history of psychology, acknowledging both its achievements and its ugliness, such as psychology’s contribution to eugenics and its failure to recognize the intellectual potential of BIPOC people and women. We have highlighted the transformative efforts of social justice activists within the discipline. As you consider becoming a psychology major or potential careers in psychology, it is important to recognize the profound impact psychologists can have on individuals and society as a whole. By studying the human mind and behavior, we can contribute to understanding, supporting, and advocating for the well-being of others. With this knowledge, we hope that you will embrace opportunities to make a positive difference and foster social change.

Introduction to Psychology (A critical approach) Copyright © 2021 by Rose M. Spielman; Kathryn Dumper; William Jenkins; Arlene Lacombe; Marilyn Lovett; and Marion Perlmutter is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to conclude an essay | Interactive example

How to Conclude an Essay | Interactive Example

Published on January 24, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 23, 2023.

The conclusion is the final paragraph of your essay . A strong conclusion aims to:

- Tie together the essay’s main points

- Show why your argument matters

- Leave the reader with a strong impression

Your conclusion should give a sense of closure and completion to your argument, but also show what new questions or possibilities it has opened up.

This conclusion is taken from our annotated essay example , which discusses the history of the Braille system. Hover over each part to see why it’s effective.

Braille paved the way for dramatic cultural changes in the way blind people were treated and the opportunities available to them. Louis Braille’s innovation was to reimagine existing reading systems from a blind perspective, and the success of this invention required sighted teachers to adapt to their students’ reality instead of the other way around. In this sense, Braille helped drive broader social changes in the status of blindness. New accessibility tools provide practical advantages to those who need them, but they can also change the perspectives and attitudes of those who do not.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: return to your thesis, step 2: review your main points, step 3: show why it matters, what shouldn’t go in the conclusion, more examples of essay conclusions, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about writing an essay conclusion.

To begin your conclusion, signal that the essay is coming to an end by returning to your overall argument.

Don’t just repeat your thesis statement —instead, try to rephrase your argument in a way that shows how it has been developed since the introduction.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Next, remind the reader of the main points that you used to support your argument.

Avoid simply summarizing each paragraph or repeating each point in order; try to bring your points together in a way that makes the connections between them clear. The conclusion is your final chance to show how all the paragraphs of your essay add up to a coherent whole.

To wrap up your conclusion, zoom out to a broader view of the topic and consider the implications of your argument. For example:

- Does it contribute a new understanding of your topic?

- Does it raise new questions for future study?

- Does it lead to practical suggestions or predictions?

- Can it be applied to different contexts?

- Can it be connected to a broader debate or theme?

Whatever your essay is about, the conclusion should aim to emphasize the significance of your argument, whether that’s within your academic subject or in the wider world.

Try to end with a strong, decisive sentence, leaving the reader with a lingering sense of interest in your topic.

The easiest way to improve your conclusion is to eliminate these common mistakes.

Don’t include new evidence

Any evidence or analysis that is essential to supporting your thesis statement should appear in the main body of the essay.

The conclusion might include minor pieces of new information—for example, a sentence or two discussing broader implications, or a quotation that nicely summarizes your central point. But it shouldn’t introduce any major new sources or ideas that need further explanation to understand.

Don’t use “concluding phrases”

Avoid using obvious stock phrases to tell the reader what you’re doing:

- “In conclusion…”

- “To sum up…”

These phrases aren’t forbidden, but they can make your writing sound weak. By returning to your main argument, it will quickly become clear that you are concluding the essay—you shouldn’t have to spell it out.

Don’t undermine your argument

Avoid using apologetic phrases that sound uncertain or confused:

- “This is just one approach among many.”

- “There are good arguments on both sides of this issue.”

- “There is no clear answer to this problem.”

Even if your essay has explored different points of view, your own position should be clear. There may be many possible approaches to the topic, but you want to leave the reader convinced that yours is the best one!

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

- Argumentative

- Literary analysis

This conclusion is taken from an argumentative essay about the internet’s impact on education. It acknowledges the opposing arguments while taking a clear, decisive position.

The internet has had a major positive impact on the world of education; occasional pitfalls aside, its value is evident in numerous applications. The future of teaching lies in the possibilities the internet opens up for communication, research, and interactivity. As the popularity of distance learning shows, students value the flexibility and accessibility offered by digital education, and educators should fully embrace these advantages. The internet’s dangers, real and imaginary, have been documented exhaustively by skeptics, but the internet is here to stay; it is time to focus seriously on its potential for good.

This conclusion is taken from a short expository essay that explains the invention of the printing press and its effects on European society. It focuses on giving a clear, concise overview of what was covered in the essay.

The invention of the printing press was important not only in terms of its immediate cultural and economic effects, but also in terms of its major impact on politics and religion across Europe. In the century following the invention of the printing press, the relatively stationary intellectual atmosphere of the Middle Ages gave way to the social upheavals of the Reformation and the Renaissance. A single technological innovation had contributed to the total reshaping of the continent.

This conclusion is taken from a literary analysis essay about Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein . It summarizes what the essay’s analysis achieved and emphasizes its originality.

By tracing the depiction of Frankenstein through the novel’s three volumes, I have demonstrated how the narrative structure shifts our perception of the character. While the Frankenstein of the first volume is depicted as having innocent intentions, the second and third volumes—first in the creature’s accusatory voice, and then in his own voice—increasingly undermine him, causing him to appear alternately ridiculous and vindictive. Far from the one-dimensional villain he is often taken to be, the character of Frankenstein is compelling because of the dynamic narrative frame in which he is placed. In this frame, Frankenstein’s narrative self-presentation responds to the images of him we see from others’ perspectives. This conclusion sheds new light on the novel, foregrounding Shelley’s unique layering of narrative perspectives and its importance for the depiction of character.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Your essay’s conclusion should contain:

- A rephrased version of your overall thesis

- A brief review of the key points you made in the main body

- An indication of why your argument matters

The conclusion may also reflect on the broader implications of your argument, showing how your ideas could applied to other contexts or debates.

For a stronger conclusion paragraph, avoid including:

- Important evidence or analysis that wasn’t mentioned in the main body

- Generic concluding phrases (e.g. “In conclusion…”)

- Weak statements that undermine your argument (e.g. “There are good points on both sides of this issue.”)

Your conclusion should leave the reader with a strong, decisive impression of your work.

The conclusion paragraph of an essay is usually shorter than the introduction . As a rule, it shouldn’t take up more than 10–15% of the text.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, July 23). How to Conclude an Essay | Interactive Example. Scribbr. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/conclusion/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, example of a great essay | explanations, tips & tricks, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

The discussion section contains the results and outcomes of a study. An effective discussion informs readers what can be learned from your experiment and provides context for the results.

What makes an effective discussion?

When you’re ready to write your discussion, you’ve already introduced the purpose of your study and provided an in-depth description of the methodology. The discussion informs readers about the larger implications of your study based on the results. Highlighting these implications while not overstating the findings can be challenging, especially when you’re submitting to a journal that selects articles based on novelty or potential impact. Regardless of what journal you are submitting to, the discussion section always serves the same purpose: concluding what your study results actually mean.

A successful discussion section puts your findings in context. It should include:

- the results of your research,

- a discussion of related research, and

- a comparison between your results and initial hypothesis.

Tip: Not all journals share the same naming conventions.

You can apply the advice in this article to the conclusion, results or discussion sections of your manuscript.

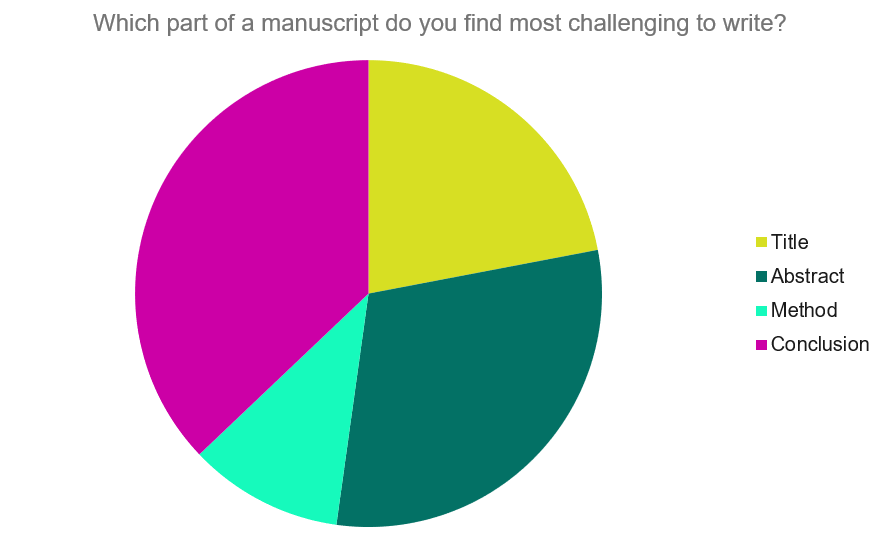

Our Early Career Researcher community tells us that the conclusion is often considered the most difficult aspect of a manuscript to write. To help, this guide provides questions to ask yourself, a basic structure to model your discussion off of and examples from published manuscripts.

Questions to ask yourself:

- Was my hypothesis correct?

- If my hypothesis is partially correct or entirely different, what can be learned from the results?

- How do the conclusions reshape or add onto the existing knowledge in the field? What does previous research say about the topic?

- Why are the results important or relevant to your audience? Do they add further evidence to a scientific consensus or disprove prior studies?

- How can future research build on these observations? What are the key experiments that must be done?

- What is the “take-home” message you want your reader to leave with?

How to structure a discussion

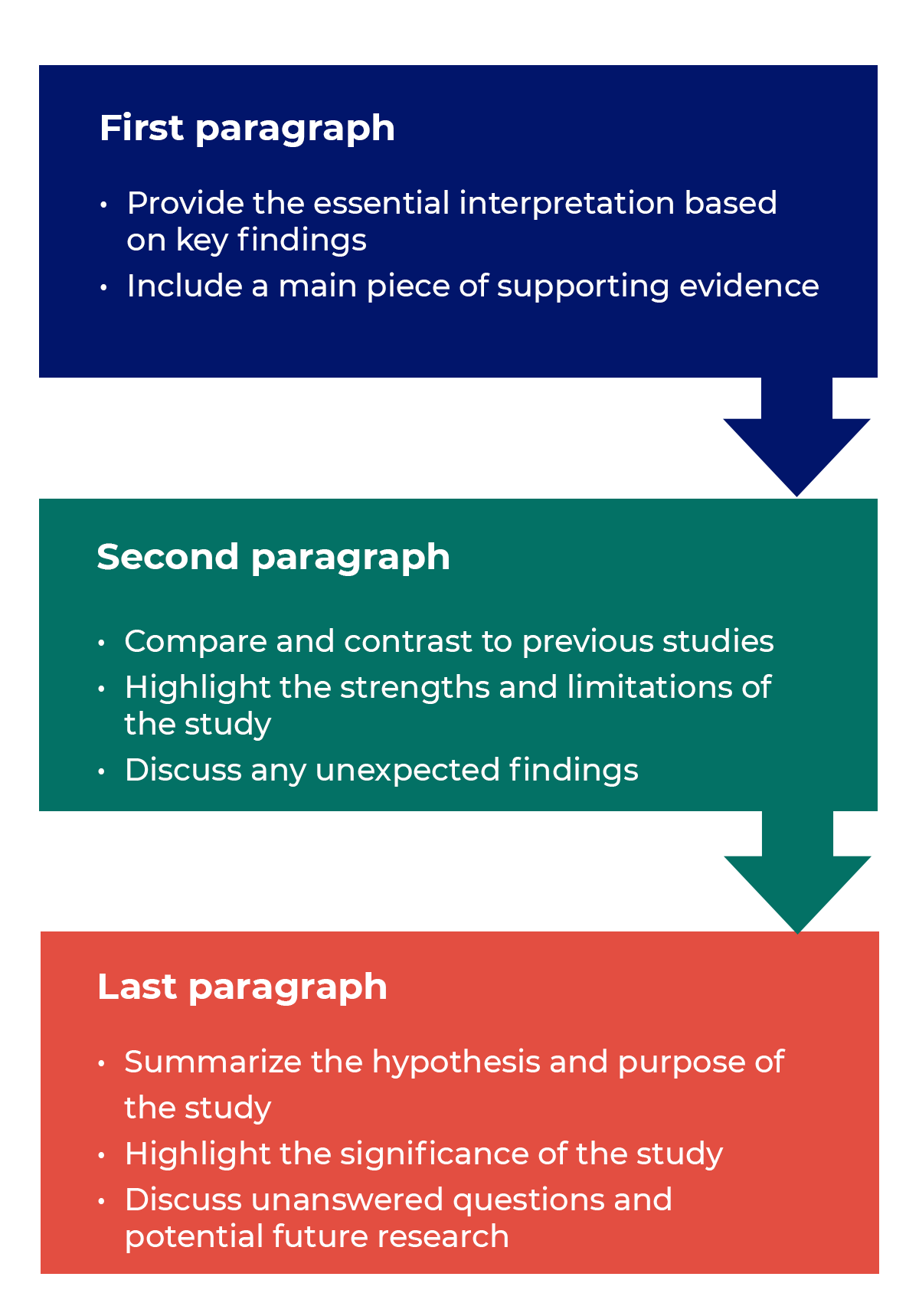

Trying to fit a complete discussion into a single paragraph can add unnecessary stress to the writing process. If possible, you’ll want to give yourself two or three paragraphs to give the reader a comprehensive understanding of your study as a whole. Here’s one way to structure an effective discussion:

Writing Tips

While the above sections can help you brainstorm and structure your discussion, there are many common mistakes that writers revert to when having difficulties with their paper. Writing a discussion can be a delicate balance between summarizing your results, providing proper context for your research and avoiding introducing new information. Remember that your paper should be both confident and honest about the results!

- Read the journal’s guidelines on the discussion and conclusion sections. If possible, learn about the guidelines before writing the discussion to ensure you’re writing to meet their expectations.

- Begin with a clear statement of the principal findings. This will reinforce the main take-away for the reader and set up the rest of the discussion.

- Explain why the outcomes of your study are important to the reader. Discuss the implications of your findings realistically based on previous literature, highlighting both the strengths and limitations of the research.

- State whether the results prove or disprove your hypothesis. If your hypothesis was disproved, what might be the reasons?

- Introduce new or expanded ways to think about the research question. Indicate what next steps can be taken to further pursue any unresolved questions.

- If dealing with a contemporary or ongoing problem, such as climate change, discuss possible consequences if the problem is avoided.

- Be concise. Adding unnecessary detail can distract from the main findings.

Don’t

- Rewrite your abstract. Statements with “we investigated” or “we studied” generally do not belong in the discussion.

- Include new arguments or evidence not previously discussed. Necessary information and evidence should be introduced in the main body of the paper.

- Apologize. Even if your research contains significant limitations, don’t undermine your authority by including statements that doubt your methodology or execution.

- Shy away from speaking on limitations or negative results. Including limitations and negative results will give readers a complete understanding of the presented research. Potential limitations include sources of potential bias, threats to internal or external validity, barriers to implementing an intervention and other issues inherent to the study design.

- Overstate the importance of your findings. Making grand statements about how a study will fully resolve large questions can lead readers to doubt the success of the research.

Snippets of Effective Discussions:

Consumer-based actions to reduce plastic pollution in rivers: A multi-criteria decision analysis approach

Identifying reliable indicators of fitness in polar bears

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

What this handout is about

This handout discusses some of the common writing assignments in psychology courses, and it presents strategies for completing them. The handout also provides general tips for writing psychology papers and for reducing bias in your writing.

What is psychology?

Psychology, one of the behavioral sciences, is the scientific study of observable behaviors, like sleeping, and abstract mental processes, such as dreaming. Psychologists study, explain, and predict behaviors. Because of the complexity of human behaviors, researchers use a variety of methods and approaches. They ask questions about behaviors and answer them using systematic methods. For example, to understand why female students tend to perform better in school than their male classmates, psychologists have examined whether parents, teachers, schools, and society behave in ways that support the educational outcomes of female students to a greater extent than those of males.

Writing in psychology

Writing in psychology is similar to other forms of scientific writing in that organization, clarity, and concision are important. The Psychology Department at UNC has a strong research emphasis, so many of your assignments will focus on synthesizing and critically evaluating research, connecting your course material with current research literature, and designing and carrying out your own studies.

Common assignments

Reaction papers.

These assignments ask you to react to a scholarly journal article. Instructors use reaction papers to teach students to critically evaluate research and to synthesize current research with course material. Reaction papers typically include a brief summary of the article, including prior research, hypotheses, research method, main results, and conclusions. The next step is your critical reaction. You might critique the study, identify unresolved issues, suggest future research, or reflect on the study’s implications. Some instructors may want you to connect the material you are learning in class with the article’s theories, methodology, and findings. Remember, reaction papers require more than a simple summary of what you have read.

To successfully complete this assignment, you should carefully read the article. Go beyond highlighting important facts and interesting findings. Ask yourself questions as you read: What are the researchers’ assumptions? How does the article contribute to the field? Are the findings generalizable, and to whom? Are the conclusions valid and based on the results? It is important to pay attention to the graphs and tables because they can help you better assess the researchers’ claims.

Your instructor may give you a list of articles to choose from, or you may need to find your own. The American Psychological Association (APA) PsycINFO database is the most comprehensive collection of psychology research; it is an excellent resource for finding journal articles. You can access PsycINFO from the E-research tab on the Library’s webpage. Here are the most common types of articles you will find:

- Empirical studies test hypotheses by gathering and analyzing data. Empirical articles are organized into distinct sections based on stages in the research process: introduction, method, results, and discussion.

- Literature reviews synthesize previously published material on a topic. The authors define or clarify the problem, summarize research findings, identify gaps/inconsistencies in the research, and make suggestions for future work. Meta-analyses, in which the authors use quantitative procedures to combine the results of multiple studies, fall into this category.

- Theoretical articles trace the development of a specific theory to expand or refine it, or they present a new theory. Theoretical articles and literature reviews are organized similarly, but empirical information is included in theoretical articles only when it is used to support the theoretical issue.

You may also find methodological articles, case studies, brief reports, and commentary on previously published material. Check with your instructor to determine which articles are appropriate.

Research papers

This assignment involves using published research to provide an overview of and argument about a topic. Simply summarizing the information you read is not enough. Instead, carefully synthesize the information to support your argument. Only discuss the parts of the studies that are relevant to your argument or topic. Headings and subheadings can help guide readers through a long research paper. Our handout on literature reviews may help you organize your research literature.

Choose a topic that is appropriate to the length of the assignment and for which you can find adequate sources. For example, “self-esteem” might be too broad for a 10- page paper, but it may be difficult to find enough articles on “the effects of private school education on female African American children’s self-esteem.” A paper in which you focus on the more general topic of “the effects of school transitions on adolescents’ self-esteem,” however, might work well for the assignment.

Designing your own study/research proposal

You may have the opportunity to design and conduct your own research study or write about the design for one in the form of a research proposal. A good approach is to model your paper on articles you’ve read for class. Here is a general overview of the information that should be included in each section of a research study or proposal:

- Introduction: The introduction conveys a clear understanding of what will be done and why. Present the problem, address its significance, and describe your research strategy. Also discuss the theories that guide the research, previous research that has been conducted, and how your study builds on this literature. Set forth the hypotheses and objectives of the study.

- Methods: This section describes the procedures used to answer your research questions and provides an overview of the analyses that you conducted. For a research proposal, address the procedures that will be used to collect and analyze your data. Do not use the passive voice in this section. For example, it is better to say, “We randomly assigned patients to a treatment group and monitored their progress,” instead of “Patients were randomly assigned to a treatment group and their progress was monitored.” It is acceptable to use “I” or “we,” instead of the third person, when describing your procedures. See the section on reducing bias in language for more tips on writing this section and for discussing the study’s participants.

- Results: This section presents the findings that answer your research questions. Include all data, even if they do not support your hypotheses. If you are presenting statistical results, your instructor will probably expect you to follow the style recommendations of the American Psychological Association. You can also consult our handout on figures and charts . Note that research proposals will not include a results section, but your instructor might expect you to hypothesize about expected results.

- Discussion: Use this section to address the limitations of your study as well as the practical and/or theoretical implications of the results. You should contextualize and support your conclusions by noting how your results compare to the work of others. You can also discuss questions that emerged and call for future research. A research proposal will not include a discussion section. But you can include a short section that addresses the proposed study’s contribution to the literature on the topic.

Other writing assignments

For some assignments, you may be asked to engage personally with the course material. For example, you might provide personal examples to evaluate a theory in a reflection paper. It is appropriate to share personal experiences for this assignment, but be mindful of your audience and provide only relevant and appropriate details.

Writing tips for psychology papers

Psychology is a behavioral science, and writing in psychology is similar to writing in the hard sciences. See our handout on writing in the sciences . The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association provides an extensive discussion on how to write for the discipline. The Manual also gives the rules for psychology’s citation style, called APA. The Library’s citation tutorial will also introduce you to the APA style.

Suggestions for achieving precision and clarity in your writing

- Jargon: Technical vocabulary that is not essential to understanding your ideas can confuse readers. Similarly, refrain from using euphemistic phrases instead of clearer terms. Use “handicapped” instead of “handi-capable,” and “poverty” instead of “monetarily felt scarcity,” for example.

- Anthropomorphism: Anthropomorphism occurs when human characteristics are attributed to animals or inanimate entities. Anthropomorphism can make your writing awkward. Some examples include: “The experiment attempted to demonstrate…,” and “The tables compare…” Reword such sentences so that a person performs the action: “The experimenter attempted to demonstrate…” The verbs “show” or “indicate” can also be used: “The tables show…”

- Verb tenses: Select verb tenses carefully. Use the past tense when expressing actions or conditions that occurred at a specific time in the past, when discussing other people’s work, and when reporting results. Use the present perfect tense to express past actions or conditions that did not occur at a specific time, or to describe an action beginning in the past and continuing in the present.

- Pronoun agreement: Be consistent within and across sentences with pronouns that refer to a noun introduced earlier (antecedent). A common error is a construction such as “Each child responded to questions about their favorite toys.” The sentence should have either a plural subject (children) or a singular pronoun (his or her). Vague pronouns, such as “this” or “that,” without a clear antecedent can confuse readers: “This shows that girls are more likely than boys …” could be rewritten as “These results show that girls are more likely than boys…”

- Avoid figurative language and superlatives: Scientific writing should be as concise and specific as possible. Emotional language and superlatives, such as “very,” “highly,” “astonishingly,” “extremely,” “quite,” and even “exactly,” are imprecise or unnecessary. A line that is “exactly 100 centimeters” is, simply, 100 centimeters.

- Avoid colloquial expressions and informal language: Use “children” rather than “kids;” “many” rather than “a lot;” “acquire” rather than “get;” “prepare for” rather than “get ready;” etc.

Reducing bias in language

Your writing should show respect for research participants and readers, so it is important to choose language that is clear, accurate, and unbiased. The APA sets forth guidelines for reducing bias in language: acknowledge participation, describe individuals at the appropriate level of specificity, and be sensitive to labels. Here are some specific examples of how to reduce bias in your language:

- Acknowledge participation: Use the active voice to acknowledge the subjects’ participation. It is preferable to say, “The students completed the surveys,” instead of “The experimenters administered surveys to the students.” This is especially important when writing about participants in the methods section of a research study.

- Gender: It is inaccurate to use the term “men” when referring to groups composed of multiple genders. See our handout on gender-inclusive language for tips on writing appropriately about gender.

- Race/ethnicity: Be specific, consistent, and sensitive with terms for racial and ethnic groups. If the study participants are Chinese Americans, for instance, don’t refer to them as Asian Americans. Some ethnic designations are outdated or have negative connotations. Use terms that the individuals or groups prefer.

- Clinical terms: Broad clinical terms can be unclear. For example, if you mention “at risk” in your paper, be sure to specify the risk—“at risk for school failure.” The same principle applies to psychological disorders. For instance, “borderline personality disorder” is more precise than “borderline.”

- Labels: Do not equate people with their physical or mental conditions or categorize people broadly as objects. For example, adjectival forms like “older adults” are preferable to labels such as “the elderly” or “the schizophrenics.” Another option is to mention the person first, followed by a descriptive phrase— “people diagnosed with schizophrenia.” Be careful using the label “normal,” as it may imply that others are abnormal.

- Other ways to reduce bias: Consistently presenting information about the socially dominant group first can promote bias. Make sure that you don’t always begin with men followed by other genders when writing about gender, or whites followed by minorities when discussing race and ethnicity. Mention differences only when they are relevant and necessary to understanding the study. For example, it may not be important to indicate the sexual orientation of participants in a study about a drug treatment program’s effectiveness. Sexual orientation may be important to mention, however, when studying bullying among high school students.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

American Psychological Association. n.d. “Frequently Asked Questions About APA Style®.” APA Style. Accessed June 24, 2019. https://apastyle.apa.org/learn/faqs/index .

American Psychological Association. 2010. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association . 6th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Landrum, Eric. 2008. Undergraduate Writing in Psychology: Learning to Tell the Scientific Story . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Teesside University Student & Library Services

- Subject LibGuides

- How to write assignments

- Finding Books

- Finding Journal Articles

- Finding Open Access content

- Finding Websites and Statistics

- Finding Newspapers

- Finding Images

- How to Reference

- Doing a Systematic Review

- Finding your module Reading List

- Teesside Advance Recommended Book Bundles

Help with writing assignments

You can improve your skills at writing assignments for your subject area in a number of ways:

- Read the guidance or view the online tutorial on this page. They both go through the TIME model (Targeted, In-depth, Measured, Evidence-based) to explain what's required in academic writing.

- Come along to one of our Succeed@Tees workshops. We run a workshop on academic writing, as well as on other types of writing (including critical writing, reflective writing, report writing). See the http://tees.libguides.com/workshops for more information, including a list of dates and times.

- Book a one-to-one tutorial with a learning advisor at the Learning Hub. We can provide guidance on your structure and writing style.

Guidance on academic writing

Evidence-based.

- Bringing it all together

- Finally ...

- Writing an assignment takes time, more time than you may expect. Just because you find yourself spending many weeks on an assignment doesn’t mean that you’re approaching it in the wrong way.

- It also takes time to develop the skills to write well, so don’t be discouraged if your early marks aren’t what you’d hoped for. Use the feedback from your previous assignments to improve.