Elements of an Essay

Definition of elements of an essay.

An essay is a piece of composition that discusses a thing, a person, a problem, or an issue in a way that the writer demonstrates his knowledge by offering a new perspective , a new opinion, a solution, or new suggestions or recommendations. An essay is not just a haphazard piece of writing. It is a well-organized composition comprising several elements that work to build an argument , describe a situation, narrate an event, or state a problem with a solution. There are several types of essays based on the purpose and the target audience . Structurally, as an essay is an organized composition, it has the following elements:

- Introduction

- Body Paragraphs

Nature of Elements of an Essay

An essay has three basic elements as given above. Each of these elements plays its respective role to persuade the audience, convince the readers, and convey the meanings an author intends to convey. For example, an introduction is intended to introduce the topic of the essay. First it hooks the readers through the ‘ hook ,’ which is an anecdote , a good quote, a verse , or an event relevant to the topic. It intends to attract the attention of readers.

Following the hood, the author gives background information about the topic, which is intended to educate readers about the topic. The final element of the introduction is a thesis statement. This is a concise and compact sentence or two, which introduces evidence to be discussed in the body paragraphs.

Body paragraphs of an essay discuss the evidences and arguments introduced in the thesis statement . If a thesis statement has presented three evidences or arguments about the topic, there will be three body paragraphs. However, if there are more arguments or evidences, there could be more paragraphs.

The structure of each body paragraph is the same. It starts with a topic sentence, followed by further explanation, examples, evidences, and supporting details. If it is a simple non-research essay, then there are mostly examples of what is introduced in the topic sentences. However, if the essay is research-based, there will be supporting details such as statistics, quotes, charts, and explanations.

The conclusion is the last part of an essay. It is also the crucial part that sums up the argument, or concludes the description, narration, or event. It is comprised of three major parts. The first part is a rephrasing of the thesis statement given at the end of the introduction. It reminds the readers what they have read about. The second part is the summary of the major points discussed in the body paragraphs, and the third part is closing remarks, which are suggestions, recommendations, a call to action, or the author’s own opinion of the issue.

Function of Elements of an Essay

Each element of an essay has a specific function. An introduction not only introduces the topic, but also gives background information, in addition to hooking the readers to read the whole essay. Its first sentence, which is also called a hook, literally hooks readers. When readers have gone through the introduction, it is supposed that they have full information about what they are going to read.

In the same way, the function of body paragraphs is to give more information and convince the readers about the topic. It could be persuasion , explanation, or clarification as required. Mostly, writers use ethos , pathos , and logos in this part of an essay. As traditionally, it has three body paragraphs, writers use each of the rhetorical devices in each paragraph, but it is not a hard and fast rule. The number of body paragraphs could be increased, according to the demand of the topic, or demand of the course.

As far as the conclusion is concerned, its major function is to sum up the argument, issue, or explanation. It makes readers feel that now they are going to finish their reading. It provides them sufficient information about the topic. It gives them a new perspective, a new sight, a new vision, or motivates them to take action. The conclusion needs to also satisfy readers that they have read something about some topic, have got something to tell others, and that they have not merely read it for the sake of reading.

Related posts:

- Important Elements of Poetry

- Narrative Essay

- Definition Essay

- Descriptive Essay

- Types of Essay

- Analytical Essay

- Argumentative Essay

- Cause and Effect Essay

- Critical Essay

- Expository Essay

- Persuasive Essay

- Process Essay

- Explicatory Essay

- An Essay on Man: Epistle I

- Comparison and Contrast Essay

Post navigation

Elements of Literature

WHAT DO WE MEAN BY THE PHRASE ‘ELEMENTS OF LITERATURE?

The phrase ‘elements of literature’ refers to the constituent parts of a work of literature in whatever form it takes: poetry, prose, or drama.

Why are they important?

Students must understand these common elements if they are to competently read or write a piece of literature.

Understanding the various elements is particularly useful when studying longer works. It enables students to examine specific aspects of the work in isolation before piecing these separate aspects back together to display an understanding of the work as a whole.

Having a firm grasp on how the different elements work can also be very useful when comparing and contrasting two or more texts.

Not only does understanding the various elements of literature help us to answer literature analysis questions in exam situations, but it also helps us develop a deeper appreciation of literature in general.

what are the elements of literature ?

This article will examine the following elements: plot , setting, character, point-of-view, theme, and tone. Each of these broad elements has many possible subcategories, and there is some crossover between some elements – this isn’t Math , after all!

Hundreds of terms are associated with literature as a whole, and I recommend viewing this glossary for a complete breakdown of these.

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN AN ELEMENT OF LITERATURE AND A LITERARY DEVICE?

Elements of literature are present in every literary text. They are the essential ingredients required to create any piece of literature, including poems, plays, novels, short stories, feature articles, nonfiction books, etc.

Literary devices , on the other hand, are tools and techniques that are used to create specific effects within a work. Think metaphor, simile, hyperbole, foreshadowing, etc. We examine literary devices in detail in other articles on this site.

While the elements of literature will appear in every literary text, not every literary device will.

Now, let’s look at each of these oh-so-crucial elements of literature.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING STORY ELEMENTS

☀️This HUGE resource provides you with all the TOOLS, RESOURCES , and CONTENT to teach students about characters and story elements.

⭐ 75+ PAGES of INTERACTIVE READING, WRITING and COMPREHENSION content and NO PREPARATION REQUIRED.

Plot refers to all related things that happen in the sequence of a story. The shape of the plot comes from the order of these events and consists of several distinct aspects that we’ll look at in turn.

The plot comprises a series of cause-and-effect events that lead the reader from the story’s beginning, through the middle, to the story’s ending (though sometimes the chronological order is played with for dramatic effect).

Exposition: This is the introduction of the story. Usually, it will be where the reader acquires the necessary background information they’ll need to follow the various plot threads through to the end. This is also where the story’s setting is established, the main characters are introduced to the reader, and the central conflict emerges.

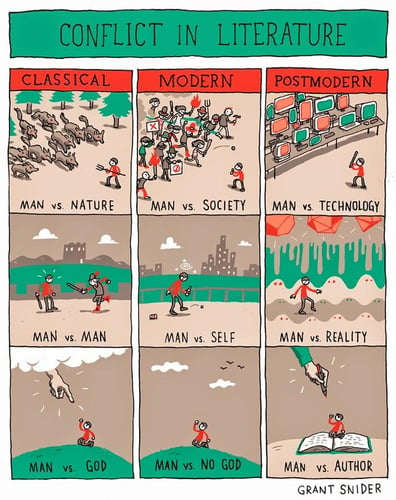

Conflict: The conflict of the story serves as the focus and driving force of most of the story’s actions. Essentially, conflict consists of a central (and sometimes secondary) problem. Without a problem or conflict, there is no story. Conflict usually takes the form of two opposing forces. These can be external forces or, sometimes, these opposing forces can take the form of an internal struggle within the protagonist or main character.

Rising Action: The rising action of the narrative begins at the end of the exposition. It usually forms most of the plot and begins with an inciting incident that kick-starts a series of cause-and-effect events. The rising action builds on tension and culminates in the climax.

Climax: After introducing the problem or central conflict of the story, the action rises as the drama unfolds in a series of causes and effects . These events culminate in the story’s dramatic high point, known as the climax. This is when the tension finally reaches its breaking point

Falling Action: This part of the narrative comprises the events that happen after the climax. Things begin to slow down and work their way towards the story’s end, tying up loose ends on the way. We can think of the falling action as a de-escalation of the story’s drama.

Resolution: This is the final part of the plot arc and represents the closing of the conflict and the return of normality – or new normality – in the wake of the story’s events. Often, this takes the form of a significant change within the main character. A resolution restores balance and order to the world or brings about a new balance and order.

PRACTICE ACTIVITY: PLOT

Discuss a well-known story in class. Fairytales are an excellent resource for this activity. Students must name a scene from each story that corresponds to each of the sections of the plot as listed above: exposition, conflict, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution.

Setting consists of two key elements: space and time. Space refers to the where of the story, most often the geographical location where the action of the story takes place. Time refers to the when of the story. This could be a historical period, the present, or the future.

The setting has other aspects for the reader or writer to consider. For example, drilling down from the broader time and place, elements such as the weather, cultural context, physical surroundings, etc., can be important.

The setting is a crucial part of a story’s exposition and is often used to establish the mood of the story. A carefully crafted setting can be used to skillfully hint at the story’s theme and reveal some aspects of the various characters.

PRACTICE ACTIVITY: SETTING

Gather up a variety of fiction and nonfiction texts. Students should go through the selected texts and write two sentences about each that identify the settings of each. The sentences should make clear where and when the stories take place.

3. CHARACTER

A story’s characters are the doers of the actions. Characters most often take human form, but, on occasion, a story can employ animals, fantastical creatures, and even inanimate objects as characters.

Some characters are dynamic and change over the course of a story, while others are static and do not grow or change due to the story’s action.

There are many different types of characters to be found in works of literature, and each serves a different function.

Now, let’s look at some of the most important of these.

Protagonist

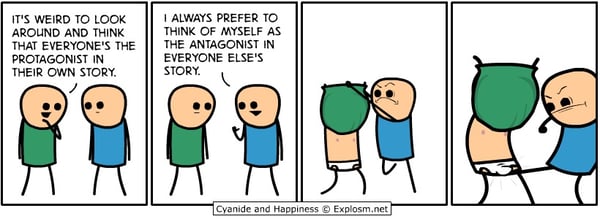

The protagonist is the story’s main character. The story’s plot centers around these characters, who are usually sympathetic and likable to the reader; that is, they are most often the ‘hero’ of the story.

The antagonist is the bad guy or girl of the piece. Most of the plot’s action is borne of the conflict between the protagonist and the antagonist.

Flat Character

Flat characters are one-dimensional characters that are purely functional in the story. They are more a sketch than a detailed portrait, and they help move the action along by serving a simple purpose. We aren’t afforded much insight into the interior lives of such characters.

Rounded Character

Unlike flat characters, rounded characters are more complex and drawn in more detail by the writer. As well as being described in comprehensive physical detail, we will gain an insight into the character’s interior life, their hopes, fears, dreams, desires, etc.

Choose a play that has been studied in class. Students should look at the character list and then categorize each of the characters according to the abovementioned types: protagonist, antagonist, flat character, or rounded character. As an extension, can the students identify whether each character is dynamic or static by the end of the tale?

4: POINT OF VIEW

Point of view in literature refers to the perspective through which you experience the story’s events.

There are various advantages and disadvantages to the different points of view available for the writer, but they can all be usefully categorized according to whether they’re first-person, second-person, or third-person points of view.

Now, let’s look at some of the most common points of view in each category.

First Person

The key to recognizing this point of view is using pronouns such as I, me, my, we, us, our, etc. There are several variations of the first-person narrative , but they all have a single person narrating the story’s events either as it unfolds or in the past tense.

When considering a first-person narrative, the first question to ask is who is the person telling the story. Let’s look at two main types of the first-person point of view.

First-Person Protagonist : This is when the story’s main character relates the action first-hand as he or she experiences or experienced it. As the narrator is also the main character, the reader is placed right at the center of the action and sees events unfold through the main character’s eyes.

First-Person Periphery: In this case, we see the story unfold, not from the main character’s POV but from the perspective of a secondary character with limited participation in the story itself.

Second Person: This perspective is uncommon. Though it is hard to pull off without sounding corny, you will find it in some books, such as those Choose Your Own Adventure-type books. You can recognize this perspective by using the second person pronoun ‘you’.

Third Person Limited: From this perspective, we see events unfold from the point of view of one person in the story. As the name suggests, we are limited to seeing things from the perspective of the third-person narrator and do not gain insight into the internal life of the other characters other than through their actions as described by the third-person narrator (he, she, they, etc.).

Third Person Omniscient: The great eye in the sky! The 3rd person omniscient narrator, as the name suggests, knows everything about everyone. From this point of view, nothing is off-limits. This allows the reader to peek behind every curtain and into every corner of what is going on as the narrator moves freely through time and space, jumping in and out of the characters’ heads along the way.

Advantages and Disadvantages

As we’ve mentioned, there are specific advantages and disadvantages to each of the different points of view. While the third-person omniscient point of view allows the reader full access to each character, the third-person limited point of view is great for building tension in a story as the writer can control what the reader knows and when they know it.

The main advantage of the first-person perspective is that it puts the reader into the head of the narrator. This brings a sense of intimacy and personal detail to the story.

We have a complete guide to point of view here for further details.

PRACTICE ACTIVITY: POINT OF VIEW

Take a scene from a story or a movie that the student is familiar with (again, fairytales can serve well here). Students must rewrite the scene from each of the different POVs listed above: first-person protagonist, first-person periphery, second-person, third-person limited, and third-person omniscient. Finally, discuss the advantages and disadvantages of writing the scene from each POV. Which works best and why?

THE STORY TELLERS BUNDLE OF TEACHING RESOURCES

A MASSIVE COLLECTION of resources for narratives and story writing in the classroom covering all elements of crafting amazing stories. MONTHS WORTH OF WRITING LESSONS AND RESOURCES, including:

If the plot refers to what happens in a story, then the theme is to do with what these events mean.

The theme is the big ideas explored in a work of literature. These are often universal ideas that transcend the limits of culture, ethnicity, or language. The theme is the deeper meaning behind the events of the story.

Notably, the theme of a piece of writing is not to be confused with its subject. While the subject of a text is what it is about, the theme is more about how the writer feels about that subject as conveyed in the writing.

It is also important to note that while all works of literature have a theme, they never state that theme explicitly. Although many works of literature deal with more than one theme, it’s usually possible to detect a central theme amid the minor ones.

The most commonly asked question about themes from students is, ‘ How do we work out what the theme is? ’

The truth is, how easy or how difficult it will be to detect a work’s theme will vary significantly between different texts. The ease of identification will depend mainly on how straightforward or complex the work is.

Students should look for symbols and motifs within the text to identify the theme. Especially symbols and motifs that repeat.

Students must understand that symbols are when one thing is used to stand for another. While not all symbols are related to the text’s theme, when symbols are used repeatedly or found in a cluster, they usually relate to a motif. This motif will, in turn, relate to the theme of the work.

Of course, this leads to the question: What exactly is a motif?

A motif is a recurring idea or an element that has symbolic significance. Uncovering this significance will reveal the theme to a careful reader.

We can further understand the themes as concepts and statements. Concepts are the broad categories or issues of the work, while statements are the position the writer takes on those issues as expressed in the text.

Here are some examples of thematic concepts commonly found in literature:

- Forgiveness

When discussing a work’s theme in detail, identifying the thematic concept will not be enough. Students will need to explore what the thematic statements are in the text. That is, they need to identify the opinions the writer expresses on the thematic concepts in the text.

For example, we might identify that a story is about forgiveness, that is, that forgiveness is the primary thematic concept. When we identify what the work says about forgiveness, such as it is necessary for a person to move on with their life, we identify a thematic statement.

PRACTICE ACTIVITY: THEME

Again, choose familiar stories to work with. For each story, identify and write the thematic concept and statement. For more complex stories, multiple themes may need to be identified.

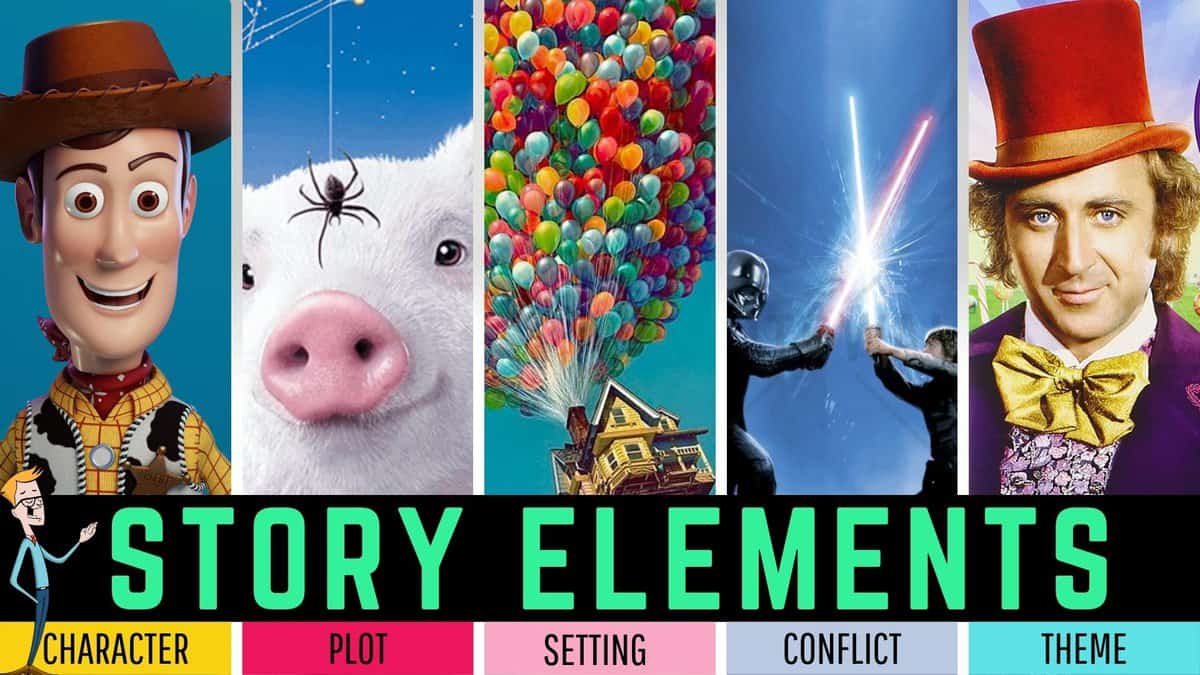

AN EXCELLENT VIDEO TUTORIAL ON STORY ELEMENTS

Tone refers to how the theme is treated in a work. Two works may have the same theme, but each may adopt a different tone in dealing with that theme. For example, the tone of a text can be serious, comical, formal, informal, gloomy, joyful, sarcastic, or sentimental, to name but eight.

The tone that the writer adopts influences how the reader reads that text. It informs how the reader will feel about the characters and events described.

Tone helps to create the mood of the piece and gives life to the story as a whole.

PRACTICE ACTIVITY: TONE

Find examples of texts that convey each of the eight tones listed above: serious, comical, formal, informal, gloomy, joyful, sarcastic, and sentimental. Give three examples from each text that convey that specific tone. The examples can be drawn from direct quotations of the narrative or dialogue or a commentary on the structure of the text.

Conclusion:

Though the essential elements of literature are few in number, they can take a lifetime to master. The more experience a student gains in creating and analyzing texts regarding these elements, the more adept they will become in their use.

Time invested in this area will reap rich rewards regarding the skill with which a student can craft a text and the level of enjoyment and meaning they can derive from their reading.

Time well spent, for sure.

TEACHING RESOURCES

Other great articles related to elements of literature.

7 ways to write great Characters and Settings | Story Elements

Teaching The 5 Story Elements: A Complete Guide for Teachers & Students

Short Story Writing for Students and Teachers

beginner's guide to literary analysis

Understanding literature & how to write literary analysis.

Literary analysis is the foundation of every college and high school English class. Once you can comprehend written work and respond to it, the next step is to learn how to think critically and complexly about a work of literature in order to analyze its elements and establish ideas about its meaning.

If that sounds daunting, it shouldn’t. Literary analysis is really just a way of thinking creatively about what you read. The practice takes you beyond the storyline and into the motives behind it.

While an author might have had a specific intention when they wrote their book, there’s still no right or wrong way to analyze a literary text—just your way. You can use literary theories, which act as “lenses” through which you can view a text. Or you can use your own creativity and critical thinking to identify a literary device or pattern in a text and weave that insight into your own argument about the text’s underlying meaning.

Now, if that sounds fun, it should , because it is. Here, we’ll lay the groundwork for performing literary analysis, including when writing analytical essays, to help you read books like a critic.

What Is Literary Analysis?

As the name suggests, literary analysis is an analysis of a work, whether that’s a novel, play, short story, or poem. Any analysis requires breaking the content into its component parts and then examining how those parts operate independently and as a whole. In literary analysis, those parts can be different devices and elements—such as plot, setting, themes, symbols, etcetera—as well as elements of style, like point of view or tone.

When performing analysis, you consider some of these different elements of the text and then form an argument for why the author chose to use them. You can do so while reading and during class discussion, but it’s particularly important when writing essays.

Literary analysis is notably distinct from summary. When you write a summary , you efficiently describe the work’s main ideas or plot points in order to establish an overview of the work. While you might use elements of summary when writing analysis, you should do so minimally. You can reference a plot line to make a point, but it should be done so quickly so you can focus on why that plot line matters . In summary (see what we did there?), a summary focuses on the “ what ” of a text, while analysis turns attention to the “ how ” and “ why .”

While literary analysis can be broad, covering themes across an entire work, it can also be very specific, and sometimes the best analysis is just that. Literary critics have written thousands of words about the meaning of an author’s single word choice; while you might not want to be quite that particular, there’s a lot to be said for digging deep in literary analysis, rather than wide.

Although you’re forming your own argument about the work, it’s not your opinion . You should avoid passing judgment on the piece and instead objectively consider what the author intended, how they went about executing it, and whether or not they were successful in doing so. Literary criticism is similar to literary analysis, but it is different in that it does pass judgement on the work. Criticism can also consider literature more broadly, without focusing on a singular work.

Once you understand what constitutes (and doesn’t constitute) literary analysis, it’s easy to identify it. Here are some examples of literary analysis and its oft-confused counterparts:

Summary: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” the narrator visits his friend Roderick Usher and witnesses his sister escape a horrible fate.

Opinion: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Poe uses his great Gothic writing to establish a sense of spookiness that is enjoyable to read.

Literary Analysis: “Throughout ‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ Poe foreshadows the fate of Madeline by creating a sense of claustrophobia for the reader through symbols, such as in the narrator’s inability to leave and the labyrinthine nature of the house.

In summary, literary analysis is:

- Breaking a work into its components

- Identifying what those components are and how they work in the text

- Developing an understanding of how they work together to achieve a goal

- Not an opinion, but subjective

- Not a summary, though summary can be used in passing

- Best when it deeply, rather than broadly, analyzes a literary element

Literary Analysis and Other Works

As discussed above, literary analysis is often performed upon a single work—but it doesn’t have to be. It can also be performed across works to consider the interplay of two or more texts. Regardless of whether or not the works were written about the same thing, or even within the same time period, they can have an influence on one another or a connection that’s worth exploring. And reading two or more texts side by side can help you to develop insights through comparison and contrast.

For example, Paradise Lost is an epic poem written in the 17th century, based largely on biblical narratives written some 700 years before and which later influenced 19th century poet John Keats. The interplay of works can be obvious, as here, or entirely the inspiration of the analyst. As an example of the latter, you could compare and contrast the writing styles of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Edgar Allan Poe who, while contemporaries in terms of time, were vastly different in their content.

Additionally, literary analysis can be performed between a work and its context. Authors are often speaking to the larger context of their times, be that social, political, religious, economic, or artistic. A valid and interesting form is to compare the author’s context to the work, which is done by identifying and analyzing elements that are used to make an argument about the writer’s time or experience.

For example, you could write an essay about how Hemingway’s struggles with mental health and paranoia influenced his later work, or how his involvement in the Spanish Civil War influenced his early work. One approach focuses more on his personal experience, while the other turns to the context of his times—both are valid.

Why Does Literary Analysis Matter?

Sometimes an author wrote a work of literature strictly for entertainment’s sake, but more often than not, they meant something more. Whether that was a missive on world peace, commentary about femininity, or an allusion to their experience as an only child, the author probably wrote their work for a reason, and understanding that reason—or the many reasons—can actually make reading a lot more meaningful.

Performing literary analysis as a form of study unquestionably makes you a better reader. It’s also likely that it will improve other skills, too, like critical thinking, creativity, debate, and reasoning.

At its grandest and most idealistic, literary analysis even has the ability to make the world a better place. By reading and analyzing works of literature, you are able to more fully comprehend the perspectives of others. Cumulatively, you’ll broaden your own perspectives and contribute more effectively to the things that matter to you.

Literary Terms to Know for Literary Analysis

There are hundreds of literary devices you could consider during your literary analysis, but there are some key tools most writers utilize to achieve their purpose—and therefore you need to know in order to understand that purpose. These common devices include:

- Characters: The people (or entities) who play roles in the work. The protagonist is the main character in the work.

- Conflict: The conflict is the driving force behind the plot, the event that causes action in the narrative, usually on the part of the protagonist

- Context : The broader circumstances surrounding the work political and social climate in which it was written or the experience of the author. It can also refer to internal context, and the details presented by the narrator

- Diction : The word choice used by the narrator or characters

- Genre: A category of literature characterized by agreed upon similarities in the works, such as subject matter and tone

- Imagery : The descriptive or figurative language used to paint a picture in the reader’s mind so they can picture the story’s plot, characters, and setting

- Metaphor: A figure of speech that uses comparison between two unlike objects for dramatic or poetic effect

- Narrator: The person who tells the story. Sometimes they are a character within the story, but sometimes they are omniscient and removed from the plot.

- Plot : The storyline of the work

- Point of view: The perspective taken by the narrator, which skews the perspective of the reader

- Setting : The time and place in which the story takes place. This can include elements like the time period, weather, time of year or day, and social or economic conditions

- Symbol : An object, person, or place that represents an abstract idea that is greater than its literal meaning

- Syntax : The structure of a sentence, either narration or dialogue, and the tone it implies

- Theme : A recurring subject or message within the work, often commentary on larger societal or cultural ideas

- Tone : The feeling, attitude, or mood the text presents

How to Perform Literary Analysis

Step 1: read the text thoroughly.

Literary analysis begins with the literature itself, which means performing a close reading of the text. As you read, you should focus on the work. That means putting away distractions (sorry, smartphone) and dedicating a period of time to the task at hand.

It’s also important that you don’t skim or speed read. While those are helpful skills, they don’t apply to literary analysis—or at least not this stage.

Step 2: Take Notes as You Read

As you read the work, take notes about different literary elements and devices that stand out to you. Whether you highlight or underline in text, use sticky note tabs to mark pages and passages, or handwrite your thoughts in a notebook, you should capture your thoughts and the parts of the text to which they correspond. This—the act of noticing things about a literary work—is literary analysis.

Step 3: Notice Patterns

As you read the work, you’ll begin to notice patterns in the way the author deploys language, themes, and symbols to build their plot and characters. As you read and these patterns take shape, begin to consider what they could mean and how they might fit together.

As you identify these patterns, as well as other elements that catch your interest, be sure to record them in your notes or text. Some examples include:

- Circle or underline words or terms that you notice the author uses frequently, whether those are nouns (like “eyes” or “road”) or adjectives (like “yellow” or “lush”).

- Highlight phrases that give you the same kind of feeling. For example, if the narrator describes an “overcast sky,” a “dreary morning,” and a “dark, quiet room,” the words aren’t the same, but the feeling they impart and setting they develop are similar.

- Underline quotes or prose that define a character’s personality or their role in the text.

- Use sticky tabs to color code different elements of the text, such as specific settings or a shift in the point of view.

By noting these patterns, comprehensive symbols, metaphors, and ideas will begin to come into focus.

Step 4: Consider the Work as a Whole, and Ask Questions

This is a step that you can do either as you read, or after you finish the text. The point is to begin to identify the aspects of the work that most interest you, and you could therefore analyze in writing or discussion.

Questions you could ask yourself include:

- What aspects of the text do I not understand?

- What parts of the narrative or writing struck me most?

- What patterns did I notice?

- What did the author accomplish really well?

- What did I find lacking?

- Did I notice any contradictions or anything that felt out of place?

- What was the purpose of the minor characters?

- What tone did the author choose, and why?

The answers to these and more questions will lead you to your arguments about the text.

Step 5: Return to Your Notes and the Text for Evidence

As you identify the argument you want to make (especially if you’re preparing for an essay), return to your notes to see if you already have supporting evidence for your argument. That’s why it’s so important to take notes or mark passages as you read—you’ll thank yourself later!

If you’re preparing to write an essay, you’ll use these passages and ideas to bolster your argument—aka, your thesis. There will likely be multiple different passages you can use to strengthen multiple different aspects of your argument. Just be sure to cite the text correctly!

If you’re preparing for class, your notes will also be invaluable. When your teacher or professor leads the conversation in the direction of your ideas or arguments, you’ll be able to not only proffer that idea but back it up with textual evidence. That’s an A+ in class participation.

Step 6: Connect These Ideas Across the Narrative

Whether you’re in class or writing an essay, literary analysis isn’t complete until you’ve considered the way these ideas interact and contribute to the work as a whole. You can find and present evidence, but you still have to explain how those elements work together and make up your argument.

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay

When conducting literary analysis while reading a text or discussing it in class, you can pivot easily from one argument to another (or even switch sides if a classmate or teacher makes a compelling enough argument).

But when writing literary analysis, your objective is to propose a specific, arguable thesis and convincingly defend it. In order to do so, you need to fortify your argument with evidence from the text (and perhaps secondary sources) and an authoritative tone.

A successful literary analysis essay depends equally on a thoughtful thesis, supportive analysis, and presenting these elements masterfully. We’ll review how to accomplish these objectives below.

Step 1: Read the Text. Maybe Read It Again.

Constructing an astute analytical essay requires a thorough knowledge of the text. As you read, be sure to note any passages, quotes, or ideas that stand out. These could serve as the future foundation of your thesis statement. Noting these sections now will help you when you need to gather evidence.

The more familiar you become with the text, the better (and easier!) your essay will be. Familiarity with the text allows you to speak (or in this case, write) to it confidently. If you only skim the book, your lack of rich understanding will be evident in your essay. Alternatively, if you read the text closely—especially if you read it more than once, or at least carefully revisit important passages—your own writing will be filled with insight that goes beyond a basic understanding of the storyline.

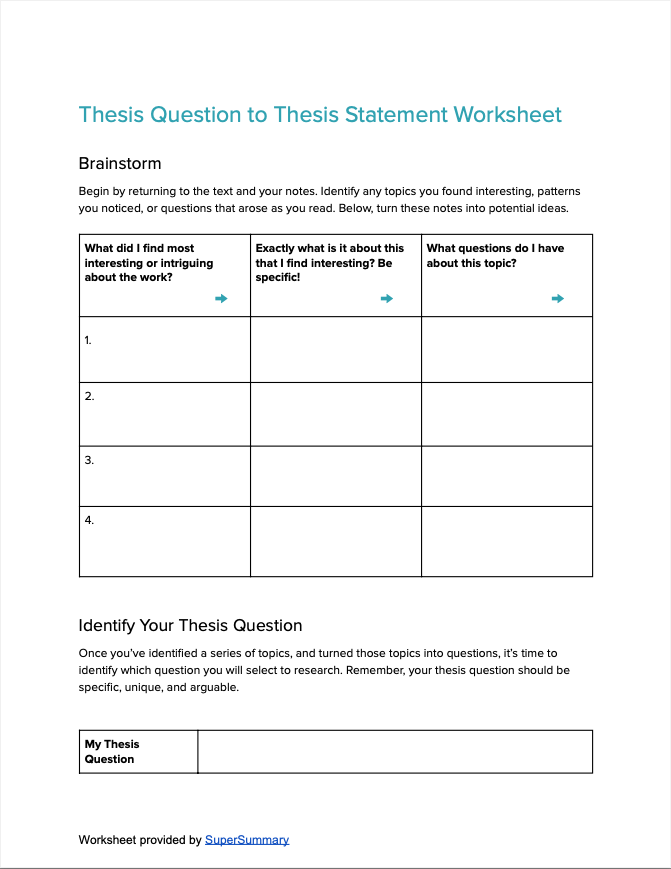

Step 2: Brainstorm Potential Topics

Because you took detailed notes while reading the text, you should have a list of potential topics at the ready. Take time to review your notes, highlighting any ideas or questions you had that feel interesting. You should also return to the text and look for any passages that stand out to you.

When considering potential topics, you should prioritize ideas that you find interesting. It won’t only make the whole process of writing an essay more fun, your enthusiasm for the topic will probably improve the quality of your argument, and maybe even your writing. Just like it’s obvious when a topic interests you in a conversation, it’s obvious when a topic interests the writer of an essay (and even more obvious when it doesn’t).

Your topic ideas should also be specific, unique, and arguable. A good way to think of topics is that they’re the answer to fairly specific questions. As you begin to brainstorm, first think of questions you have about the text. Questions might focus on the plot, such as: Why did the author choose to deviate from the projected storyline? Or why did a character’s role in the narrative shift? Questions might also consider the use of a literary device, such as: Why does the narrator frequently repeat a phrase or comment on a symbol? Or why did the author choose to switch points of view each chapter?

Once you have a thesis question , you can begin brainstorming answers—aka, potential thesis statements . At this point, your answers can be fairly broad. Once you land on a question-statement combination that feels right, you’ll then look for evidence in the text that supports your answer (and helps you define and narrow your thesis statement).

For example, after reading “ The Fall of the House of Usher ,” you might be wondering, Why are Roderick and Madeline twins?, Or even: Why does their relationship feel so creepy?” Maybe you noticed (and noted) that the narrator was surprised to find out they were twins, or perhaps you found that the narrator’s tone tended to shift and become more anxious when discussing the interactions of the twins.

Once you come up with your thesis question, you can identify a broad answer, which will become the basis for your thesis statement. In response to the questions above, your answer might be, “Poe emphasizes the close relationship of Roderick and Madeline to foreshadow that their deaths will be close, too.”

Step 3: Gather Evidence

Once you have your topic (or you’ve narrowed it down to two or three), return to the text (yes, again) to see what evidence you can find to support it. If you’re thinking of writing about the relationship between Roderick and Madeline in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” look for instances where they engaged in the text.

This is when your knowledge of literary devices comes in clutch. Carefully study the language around each event in the text that might be relevant to your topic. How does Poe’s diction or syntax change during the interactions of the siblings? How does the setting reflect or contribute to their relationship? What imagery or symbols appear when Roderick and Madeline are together?

By finding and studying evidence within the text, you’ll strengthen your topic argument—or, just as valuably, discount the topics that aren’t strong enough for analysis.

Step 4: Consider Secondary Sources

In addition to returning to the literary work you’re studying for evidence, you can also consider secondary sources that reference or speak to the work. These can be articles from journals you find on JSTOR, books that consider the work or its context, or articles your teacher shared in class.

While you can use these secondary sources to further support your idea, you should not overuse them. Make sure your topic remains entirely differentiated from that presented in the source.

Step 5: Write a Working Thesis Statement

Once you’ve gathered evidence and narrowed down your topic, you’re ready to refine that topic into a thesis statement. As you continue to outline and write your paper, this thesis statement will likely change slightly, but this initial draft will serve as the foundation of your essay. It’s like your north star: Everything you write in your essay is leading you back to your thesis.

Writing a great thesis statement requires some real finesse. A successful thesis statement is:

- Debatable : You shouldn’t simply summarize or make an obvious statement about the work. Instead, your thesis statement should take a stand on an issue or make a claim that is open to argument. You’ll spend your essay debating—and proving—your argument.

- Demonstrable : You need to be able to prove, through evidence, that your thesis statement is true. That means you have to have passages from the text and correlative analysis ready to convince the reader that you’re right.

- Specific : In most cases, successfully addressing a theme that encompasses a work in its entirety would require a book-length essay. Instead, identify a thesis statement that addresses specific elements of the work, such as a relationship between characters, a repeating symbol, a key setting, or even something really specific like the speaking style of a character.

Example: By depicting the relationship between Roderick and Madeline to be stifling and almost otherworldly in its closeness, Poe foreshadows both Madeline’s fate and Roderick’s inability to choose a different fate for himself.

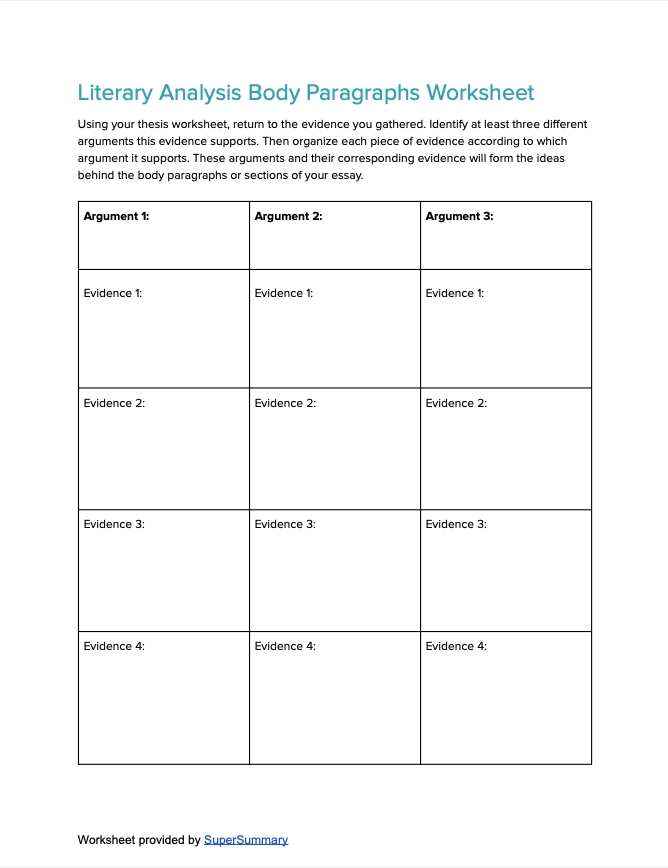

Step 6: Write an Outline

You have your thesis, you have your evidence—but how do you put them together? A great thesis statement (and therefore a great essay) will have multiple arguments supporting it, presenting different kinds of evidence that all contribute to the singular, main idea presented in your thesis.

Review your evidence and identify these different arguments, then organize the evidence into categories based on the argument they support. These ideas and evidence will become the body paragraphs of your essay.

For example, if you were writing about Roderick and Madeline as in the example above, you would pull evidence from the text, such as the narrator’s realization of their relationship as twins; examples where the narrator’s tone of voice shifts when discussing their relationship; imagery, like the sounds Roderick hears as Madeline tries to escape; and Poe’s tendency to use doubles and twins in his other writings to create the same spooky effect. All of these are separate strains of the same argument, and can be clearly organized into sections of an outline.

Step 7: Write Your Introduction

Your introduction serves a few very important purposes that essentially set the scene for the reader:

- Establish context. Sure, your reader has probably read the work. But you still want to remind them of the scene, characters, or elements you’ll be discussing.

- Present your thesis statement. Your thesis statement is the backbone of your analytical paper. You need to present it clearly at the outset so that the reader understands what every argument you make is aimed at.

- Offer a mini-outline. While you don’t want to show all your cards just yet, you do want to preview some of the evidence you’ll be using to support your thesis so that the reader has a roadmap of where they’re going.

Step 8: Write Your Body Paragraphs

Thanks to steps one through seven, you’ve already set yourself up for success. You have clearly outlined arguments and evidence to support them. Now it’s time to translate those into authoritative and confident prose.

When presenting each idea, begin with a topic sentence that encapsulates the argument you’re about to make (sort of like a mini-thesis statement). Then present your evidence and explanations of that evidence that contribute to that argument. Present enough material to prove your point, but don’t feel like you necessarily have to point out every single instance in the text where this element takes place. For example, if you’re highlighting a symbol that repeats throughout the narrative, choose two or three passages where it is used most effectively, rather than trying to squeeze in all ten times it appears.

While you should have clearly defined arguments, the essay should still move logically and fluidly from one argument to the next. Try to avoid choppy paragraphs that feel disjointed; every idea and argument should feel connected to the last, and, as a group, connected to your thesis. A great way to connect the ideas from one paragraph to the next is with transition words and phrases, such as:

- Furthermore

- In addition

- On the other hand

- Conversely

Step 9: Write Your Conclusion

Your conclusion is more than a summary of your essay's parts, but it’s also not a place to present brand new ideas not already discussed in your essay. Instead, your conclusion should return to your thesis (without repeating it verbatim) and point to why this all matters. If writing about the siblings in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” for example, you could point out that the utilization of twins and doubles is a common literary element of Poe’s work that contributes to the definitive eeriness of Gothic literature.

While you might speak to larger ideas in your conclusion, be wary of getting too macro. Your conclusion should still be supported by all of the ideas that preceded it.

Step 10: Revise, Revise, Revise

Of course you should proofread your literary analysis essay before you turn it in. But you should also edit the content to make sure every piece of evidence and every explanation directly supports your thesis as effectively and efficiently as possible.

Sometimes, this might mean actually adapting your thesis a bit to the rest of your essay. At other times, it means removing redundant examples or paraphrasing quotations. Make sure every sentence is valuable, and remove those that aren’t.

Other Resources for Literary Analysis

With these skills and suggestions, you’re well on your way to practicing and writing literary analysis. But if you don’t have a firm grasp on the concepts discussed above—such as literary devices or even the content of the text you’re analyzing—it will still feel difficult to produce insightful analysis.

If you’d like to sharpen the tools in your literature toolbox, there are plenty of other resources to help you do so:

- Check out our expansive library of Literary Devices . These could provide you with a deeper understanding of the basic devices discussed above or introduce you to new concepts sure to impress your professors ( anagnorisis , anyone?).

- This Academic Citation Resource Guide ensures you properly cite any work you reference in your analytical essay.

- Our English Homework Help Guide will point you to dozens of resources that can help you perform analysis, from critical reading strategies to poetry helpers.

- This Grammar Education Resource Guide will direct you to plenty of resources to refine your grammar and writing (definitely important for getting an A+ on that paper).

Of course, you should know the text inside and out before you begin writing your analysis. In order to develop a true understanding of the work, read through its corresponding SuperSummary study guide . Doing so will help you truly comprehend the plot, as well as provide some inspirational ideas for your analysis.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction

You’ve been assigned a literary analysis paper—what does that even mean? Is it like a book report that you used to write in high school? Well, not really.

A literary analysis essay asks you to make an original argument about a poem, play, or work of fiction and support that argument with research and evidence from your careful reading of the text.

It can take many forms, such as a close reading of a text, critiquing the text through a particular literary theory, comparing one text to another, or criticizing another critic’s interpretation of the text. While there are many ways to structure a literary essay, writing this kind of essay follows generally follows a similar process for everyone

Crafting a good literary analysis essay begins with good close reading of the text, in which you have kept notes and observations as you read. This will help you with the first step, which is selecting a topic to write about—what jumped out as you read, what are you genuinely interested in? The next step is to focus your topic, developing it into an argument—why is this subject or observation important? Why should your reader care about it as much as you do? The third step is to gather evidence to support your argument, for literary analysis, support comes in the form of evidence from the text and from your research on what other literary critics have said about your topic. Only after you have performed these steps, are you ready to begin actually writing your essay.

Writing a Literary Analysis Essay

How to create a topic and conduct research:.

Writing an Analysis of a Poem, Story, or Play

If you are taking a literature course, it is important that you know how to write an analysis—sometimes called an interpretation or a literary analysis or a critical reading or a critical analysis—of a story, a poem, and a play. Your instructor will probably assign such an analysis as part of the course assessment. On your mid-term or final exam, you might have to write an analysis of one or more of the poems and/or stories on your reading list. Or the dreaded “sight poem or story” might appear on an exam, a work that is not on the reading list, that you have not read before, but one your instructor includes on the exam to examine your ability to apply the active reading skills you have learned in class to produce, independently, an effective literary analysis.You might be asked to write instead or, or in addition to an analysis of a literary work, a more sophisticated essay in which you compare and contrast the protagonists of two stories, or the use of form and metaphor in two poems, or the tragic heroes in two plays.

You might learn some literary theory in your course and be asked to apply theory—feminist, Marxist, reader-response, psychoanalytic, new historicist, for example—to one or more of the works on your reading list. But the seminal assignment in a literature course is the analysis of the single poem, story, novel, or play, and, even if you do not have to complete this assignment specifically, it will form the basis of most of the other writing assignments you will be required to undertake in your literature class. There are several ways of structuring a literary analysis, and your instructor might issue specific instructions on how he or she wants this assignment done. The method presented here might not be identical to the one your instructor wants you to follow, but it will be easy enough to modify, if your instructor expects something a bit different, and it is a good default method, if your instructor does not issue more specific guidelines.You want to begin your analysis with a paragraph that provides the context of the work you are analyzing and a brief account of what you believe to be the poem or story or play’s main theme. At a minimum, your account of the work’s context will include the name of the author, the title of the work, its genre, and the date and place of publication. If there is an important biographical or historical context to the work, you should include that, as well.Try to express the work’s theme in one or two sentences. Theme, you will recall, is that insight into human experience the author offers to readers, usually revealed as the content, the drama, the plot of the poem, story, or play unfolds and the characters interact. Assessing theme can be a complex task. Authors usually show the theme; they don’t tell it. They rarely say, at the end of the story, words to this effect: “and the moral of my story is…” They tell their story, develop their characters, provide some kind of conflict—and from all of this theme emerges. Because identifying theme can be challenging and subjective, it is often a good idea to work through the rest of the analysis, then return to the beginning and assess theme in light of your analysis of the work’s other literary elements.Here is a good example of an introductory paragraph from Ben’s analysis of William Butler Yeats’ poem, “Among School Children.”

“Among School Children” was published in Yeats’ 1928 collection of poems The Tower. It was inspired by a visit Yeats made in 1926 to school in Waterford, an official visit in his capacity as a senator of the Irish Free State. In the course of the tour, Yeats reflects upon his own youth and the experiences that shaped the “sixty-year old, smiling public man” (line 8) he has become. Through his reflection, the theme of the poem emerges: a life has meaning when connections among apparently disparate experiences are forged into a unified whole.

In the body of your literature analysis, you want to guide your readers through a tour of the poem, story, or play, pausing along the way to comment on, analyze, interpret, and explain key incidents, descriptions, dialogue, symbols, the writer’s use of figurative language—any of the elements of literature that are relevant to a sound analysis of this particular work. Your main goal is to explain how the elements of literature work to elucidate, augment, and develop the theme. The elements of literature are common across genres: a story, a narrative poem, and a play all have a plot and characters. But certain genres privilege certain literary elements. In a poem, for example, form, imagery and metaphor might be especially important; in a story, setting and point-of-view might be more important than they are in a poem; in a play, dialogue, stage directions, lighting serve functions rarely relevant in the analysis of a story or poem.

The length of the body of an analysis of a literary work will usually depend upon the length of work being analyzed—the longer the work, the longer the analysis—though your instructor will likely establish a word limit for this assignment. Make certain that you do not simply paraphrase the plot of the story or play or the content of the poem. This is a common weakness in student literary analyses, especially when the analysis is of a poem or a play.

Here is a good example of two body paragraphs from Amelia’s analysis of “Araby” by James Joyce.

Within the story’s first few paragraphs occur several religious references which will accumulate as the story progresses. The narrator is a student at the Christian Brothers’ School; the former tenant of his house was a priest; he left behind books called The Abbot and The Devout Communicant. Near the end of the story’s second paragraph the narrator describes a “central apple tree” in the garden, under which is “the late tenant’s rusty bicycle pump.” We may begin to suspect the tree symbolizes the apple tree in the Garden of Eden and the bicycle pump, the snake which corrupted Eve, a stretch, perhaps, until Joyce’s fall-of-innocence theme becomes more apparent.

The narrator must continue to help his aunt with her errands, but, even when he is so occupied, his mind is on Mangan’s sister, as he tries to sort out his feelings for her. Here Joyce provides vivid insight into the mind of an adolescent boy at once elated and bewildered by his first crush. He wants to tell her of his “confused adoration,” but he does not know if he will ever have the chance. Joyce’s description of the pleasant tension consuming the narrator is conveyed in a striking simile, which continues to develop the narrator’s character, while echoing the religious imagery, so important to the story’s theme: “But my body was like a harp, and her words and gestures were like fingers, running along the wires.”

The concluding paragraph of your analysis should realize two goals. First, it should present your own opinion on the quality of the poem or story or play about which you have been writing. And, second, it should comment on the current relevance of the work. You should certainly comment on the enduring social relevance of the work you are explicating. You may comment, though you should never be obliged to do so, on the personal relevance of the work. Here is the concluding paragraph from Dao-Ming’s analysis of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest.

First performed in 1895, The Importance of Being Earnest has been made into a film, as recently as 2002 and is regularly revived by professional and amateur theatre companies. It endures not only because of the comic brilliance of its characters and their dialogue, but also because its satire still resonates with contemporary audiences. I am still amazed that I see in my own Asian mother a shadow of Lady Bracknell, with her obsession with finding for her daughter a husband who will maintain, if not, ideally, increase the family’s social status. We might like to think we are more liberated and socially sophisticated than our Victorian ancestors, but the starlets and eligible bachelors who star in current reality television programs illustrate the extent to which superficial concerns still influence decisions about love and even marriage. Even now, we can turn to Oscar Wilde to help us understand and laugh at those who are earnest in name only.

Dao-Ming’s conclusion is brief, but she does manage to praise the play, reaffirm its main theme, and explain its enduring appeal. And note how her last sentence cleverly establishes that sense of closure that is also a feature of an effective analysis.

You may, of course, modify the template that is presented here. Your instructor might favour a somewhat different approach to literary analysis. Its essence, though, will be your understanding and interpretation of the theme of the poem, story, or play and the skill with which the author shapes the elements of literature—plot, character, form, diction, setting, point of view—to support the theme.

Academic Writing Tips : How to Write a Literary Analysis Paper. Authored by: eHow. Located at: https://youtu.be/8adKfLwIrVk. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

BC Open Textbooks: English Literature Victorians and Moderns: https://opentextbc.ca/englishliterature/back-matter/appendix-5-writing-an-analysis-of-a-poem-story-and-play/

Literary Analysis

The challenges of writing about english literature.

Writing begins with the act of reading . While this statement is true for most college papers, strong English papers tend to be the product of highly attentive reading (and rereading). When your instructors ask you to do a “close reading,” they are asking you to read not only for content, but also for structures and patterns. When you perform a close reading, then, you observe how form and content interact. In some cases, form reinforces content: for example, in John Donne’s Holy Sonnet 14, where the speaker invites God’s “force” “to break, blow, burn and make [him] new.” Here, the stressed monosyllables of the verbs “break,” “blow” and “burn” evoke aurally the force that the speaker invites from God. In other cases, form raises questions about content: for example, a repeated denial of guilt will likely raise questions about the speaker’s professed innocence. When you close read, take an inductive approach. Start by observing particular details in the text, such as a repeated image or word, an unexpected development, or even a contradiction. Often, a detail–such as a repeated image–can help you to identify a question about the text that warrants further examination. So annotate details that strike you as you read. Some of those details will eventually help you to work towards a thesis. And don’t worry if a detail seems trivial. If you can make a case about how an apparently trivial detail reveals something significant about the text, then your paper will have a thought-provoking thesis to argue.

Common Types of English Papers Many assignments will ask you to analyze a single text. Others, however, will ask you to read two or more texts in relation to each other, or to consider a text in light of claims made by other scholars and critics. For most assignments, close reading will be central to your paper. While some assignment guidelines will suggest topics and spell out expectations in detail, others will offer little more than a page limit. Approaching the writing process in the absence of assigned topics can be daunting, but remember that you have resources: in section, you will probably have encountered some examples of close reading; in lecture, you will have encountered some of the course’s central questions and claims. The paper is a chance for you to extend a claim offered in lecture, or to analyze a passage neglected in lecture. In either case, your analysis should do more than recapitulate claims aired in lecture and section. Because different instructors have different goals for an assignment, you should always ask your professor or TF if you have questions. These general guidelines should apply in most cases:

- A close reading of a single text: Depending on the length of the text, you will need to be more or less selective about what you choose to consider. In the case of a sonnet, you will probably have enough room to analyze the text more thoroughly than you would in the case of a novel, for example, though even here you will probably not analyze every single detail. By contrast, in the case of a novel, you might analyze a repeated scene, image, or object (for example, scenes of train travel, images of decay, or objects such as or typewriters). Alternately, you might analyze a perplexing scene (such as a novel’s ending, albeit probably in relation to an earlier moment in the novel). But even when analyzing shorter works, you will need to be selective. Although you might notice numerous interesting details as you read, not all of those details will help you to organize a focused argument about the text. For example, if you are focusing on depictions of sensory experience in Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale,” you probably do not need to analyze the image of a homeless Ruth in stanza 7, unless this image helps you to develop your case about sensory experience in the poem.

- A theoretically-informed close reading. In some courses, you will be asked to analyze a poem, a play, or a novel by using a critical theory (psychoanalytic, postcolonial, gender, etc). For example, you might use Kristeva’s theory of abjection to analyze mother-daughter relations in Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved. Critical theories provide focus for your analysis; if “abjection” is the guiding concept for your paper, you should focus on the scenes in the novel that are most relevant to the concept.

- A historically-informed close reading. In courses with a historicist orientation, you might use less self-consciously literary documents, such as newspapers or devotional manuals, to develop your analysis of a literary work. For example, to analyze how Robinson Crusoe makes sense of his island experiences, you might use Puritan tracts that narrate events in terms of how God organizes them. The tracts could help you to show not only how Robinson Crusoe draws on Puritan narrative conventions, but also—more significantly—how the novel revises those conventions.

- A comparison of two texts When analyzing two texts, you might look for unexpected contrasts between apparently similar texts, or unexpected similarities between apparently dissimilar texts, or for how one text revises or transforms the other. Keep in mind that not all of the similarities, differences, and transformations you identify will be relevant to an argument about the relationship between the two texts. As you work towards a thesis, you will need to decide which of those similarities, differences, or transformations to focus on. Moreover, unless instructed otherwise, you do not need to allot equal space to each text (unless this 50/50 allocation serves your thesis well, of course). Often you will find that one text helps to develop your analysis of another text. For example, you might analyze the transformation of Ariel’s song from The Tempest in T. S. Eliot’s poem, The Waste Land. Insofar as this analysis is interested in the afterlife of Ariel’s song in a later poem, you would likely allot more space to analyzing allusions to Ariel’s song in The Waste Land (after initially establishing the song’s significance in Shakespeare’s play, of course).

- A response paper A response paper is a great opportunity to practice your close reading skills without having to develop an entire argument. In most cases, a solid approach is to select a rich passage that rewards analysis (for example, one that depicts an important scene or a recurring image) and close read it. While response papers are a flexible genre, they are not invitations for impressionistic accounts of whether you liked the work or a particular character. Instead, you might use your close reading to raise a question about the text—to open up further investigation, rather than to supply a solution.

- A research paper. In most cases, you will receive guidance from the professor on the scope of the research paper. It is likely that you will be expected to consult sources other than the assigned readings. Hollis is your best bet for book titles, and the MLA bibliography (available through e-resources) for articles. When reading articles, make sure that they have been peer reviewed; you might also ask your TF to recommend reputable journals in the field.

Harvard College Writing Program: https://writingproject.fas.harvard.edu/files/hwp/files/bg_writing_english.pdf

In the same way that we talk with our friends about the latest episode of Game of Thrones or newest Marvel movie, scholars communicate their ideas and interpretations of literature through written literary analysis essays. Literary analysis essays make us better readers of literature.

Only through careful reading and well-argued analysis can we reach new understandings and interpretations of texts that are sometimes hundreds of years old. Literary analysis brings new meaning and can shed new light on texts. Building from careful reading and selecting a topic that you are genuinely interested in, your argument supports how you read and understand a text. Using examples from the text you are discussing in the form of textual evidence further supports your reading. Well-researched literary analysis also includes information about what other scholars have written about a specific text or topic.

Literary analysis helps us to refine our ideas, question what we think we know, and often generates new knowledge about literature. Literary analysis essays allow you to discuss your own interpretation of a given text through careful examination of the choices the original author made in the text.

ENG134 – Literary Genres Copyright © by The American Women's College and Jessica Egan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, the 9 literary elements you'll find in every story.

General Education

The AP Literature exam is designed to test your ability to analyze literature. That means you'll have to know how to use analytical tools, like literary elements, to uncover the meaning of a text.

Because literary elements are present in every piece of literature (really!), they're a good place to start when it comes to developing your analytical toolbox. In this article, we'll give you the literary element definition, explain how a literary element is different from a literary device, and look at the top nine literary elements you need to know before taking the AP Literature exam.

So let's get started!

What Are Literary Elements?

Take a minute and imagine building a house. (Stick with us, here.) What are some of the things that you would absolutely have to include in order to make a house? Some of those non-negotiable elements are a roof, walls, a kitchen, and a bathroom. If you didn't have these elements, you wouldn't have a house. Heck, you might not even have a building!

A literary element's definition is pretty similar. Literary elements are the things that all literature—whether it's a news article, a book, or a poem— absolutely have to have. Just like a house, the elements might be arranged slightly differently...but at the end of the day, they're usually all present and accounted for. Literary elements are the fundamental building blocks of writing, and they play an important role in helping us write, read, and understand literature.

You might even say that literary elements are the DNA of literature.

How Is a Literary Element Different From a Literary Device?

But wait! You've also learned about literary device (sometimes called literary techniques), which writers use to create literature!

So what makes a literary element different from a literary device?

Let's go back to our house metaphor for a second. If literary elements are the must-have, cannot-do-without parts of a house, then literary devices are the optional decor. Maybe you like a classic style (a trope !), or perhaps you're more of an eclectic kind of person (a conceit )! Just because you decorate your house like a crazy person doesn't make it any less of a house. It just means you have a...unique personal style.

Literary devices are optional techniques that writers pick and choose from to shape the style, genre, tone, meaning, and theme of their works . For example, literary devices are what make Cormac McCarthy's western novel, Blood Meridian , so different from Matt McCarthy's medical memoir, The Real Doctor Will See You Shortly . Conversely, literary elements—especially the elements that qualify both works as "books"—are what keep them shelved next to each other at Barnes & Noble. They're the non-negotiable things that make both works "literature."

Top 9 Literary Elements List (With Examples!)

Now let's take a more in-depth look at the most common elements in literature. Each term in the literary elements list below gives you the literary element definition and an example of how the elements work.

#1: Language

The most important literary element is language. Language is defined as a system of communicating ideas and feelings through signs, sounds, gestures, and/or marks. Language is the way we share ideas with one another, whether it's through speech, text, or even performance!

All literature is written in a recognizable language, since one of literature's main goals is sharing ideas, concepts, and stories with a larger audience. And since there are over 6,900 distinct languages in the world , that means literature exists in tons of different linguistic forms, too. (How cool is that?!)

Obviously, in order to read a book, you need to understand the language it's written in. But language can also be an important tool in understanding the meaning of a book, too. For instance, writers can combine languages to help readers better understand the characters, setting, or even tone. Here's an example of how Cherrie Moraga combines English and Spanish in her play, Heroes and Saints :

Look into your children's faces. They tell you the truth. They are our future. Pero no tendremos ningún futuro si seguimos siendo víctimas.

Moraga's play is about the plight of Hispanic migrant workers in the United States. By combining English and Spanish throughout the play, Moraga helps readers understand her characters and their culture better.

The plot of a work is defined as the sequence of events that occurs from the first line to the last. In other words, the plot is what happens in a story.

All literature has a plot of some kind. Most long-form literature, like a novel or a play, follows a pretty typical plot structure, also known as a plot arc. This type of plot has six elements:

- Beginning/Exposition: This is the very beginning of a story. During the exposition, authors usually introduce the major characters and settings to the reader.

- Conflict: Just like in real life, the conflict of a story is the problem that the main characters have to tackle. There are two types of conflict that you'll see in a plot. The major conflict is the overarching problem that characters face. Minor conflicts, on the other hands, are the smaller obstacles characters have to overcome to resolve the major conflict.

- Rising Action: Rising action is literally everything that happens in a story that leads up to the climax of the plot. Usually this involves facing and conquering minor conflicts, which is what keeps the plot moving forward. More importantly, writers use rising action to build tension that comes to a head during the plot's climax.

- Climax: The climax of the plot is the part of the story where the characters finally have to face and solve the major conflict. This is the "peak" of the plot where all the tension of the rising action finally comes to a head. You can usually identify the climax by figuring out which part of the story is the moment where the hero will either succeed or totally fail.

- Falling Action: Falling action is everything that happens after the book's climax but before the resolution. This is where writers tie up any loose ends and start bringing the book's action to a close.

- Resolution/Denouement: This is the conclusion of a story. But just because it's called a "resolution" doesn't mean every single issue is resolved happily—or even satisfactorily. For example, the resolution in Romeo and Juliet involves (spoiler alert!) the death of both main characters. This might not be the kind of ending you want, but it is an ending, which is why it's called the resolution!

If you've ever read a Shakespearean play, then you've seen the plot we outlined above at work. But even more contemporary novels, like The Hunger Games , also use this structure. Actually, you can think of a plot arc like a story's skeleton!

But what about poems, you ask? Do they have plots? Yes! They tend to be a little less dense, but even poems have things that happen in them.

Take a look at "Do not go gentle into that good night" by Dylan Thomas . There's definitely stuff happening in this poem: specifically, the narrator is telling readers not to accept death without a fight. While this is more simple than what happens in something like The Lord of the Rings , it's still a plot!

The mood of a piece of literature is defined as the emotion or feeling that readers get from reading the words on a page. So if you've ever read something that's made you feel tense, scared, or even happy...you've experienced mood firsthand!

While a story can have an overarching mood, it's more likely that the mood changes from scene to scene depending on what the writer is trying to convey. For example, the overall mood of a play like Romeo and Juliet may be tragic, but that doesn't mean there aren't funny, lighthearted moments in certain scenes.

Thinking about mood when you read literature is a great way to figure out how an author wants readers to feel about certain ideas, messages, and themes . These lines from "Still I Rise" by Maya Angelou are a good example of how mood impacts an idea:

You may cut me with your eyes, You may kill me with your hatefulness, But still, like air, I'll rise.

What are the emotions present in this passage? The first three lines are full of anger, bitterness, and violence, which helps readers understand that the speaker of the poem has been terribly mistreated. But despite that, the last line is full of hope. This helps Angelou show readers how she won't let others' actions—even terrible ones—hold her back.

#4: Setting

Have you ever pictured yourself in living in the Gryffindor dormitories at Hogwarts? Or maybe you've wished you could attend the Mad Hatter's tea party in Wonderland. These are examples of how settings—especially vivid ones—capture readers' imaginations and help a literary world come to life.

Setting is defined simply as the time and location in which the story takes place. The setting is also the background against which the action happens. For example, Hogwarts becomes the location, or setting, where Harry, Hermione, and Ron have many of their adventures.

Keep in mind that longer works often have multiple settings. The Harry Potter series, for example, has tons of memorable locations, like Hogsmeade, Diagon Alley, and Gringotts. Each of these settings plays an important role in bringing the Wizarding World to life.

The setting of a work is important because it helps convey important information about the world that impact other literary elements, like plot and theme. For example, a historical book set in America in the 1940s will likely have a much different atmosphere and plot than a science fiction book set three hundred years in the future. Additionally, some settings even become characters in the stories themselves! For example, the house in Edgar Allen Poe's short story, "The Fall of the House of Usher," becomes the story's antagonist . So keep an eye out for settings that serve multiple functions in a work, too.

All literary works have themes, or central messages, that authors are trying to convey. Sometimes theme is described as the main idea of a work...but more accurately, themes are any ideas that appear repeatedly throughout a text. That means that most works have multiple themes!

All literature has themes because a major purpose of literature is to share, explore, and advocate for ideas. Even the shortest poems have themes. Check out this two line poem, "My life has been the poem I would have writ," from Henry David Thoreau :

But I could not both live and utter it.

When looking for a theme, ask yourself what an author is trying to teach us or show us through their writing. In this case, Thoreau is saying we have to live in the moment, and living is what provides the material for writing.

#6: Point of View

Point of view is the position of the narrator in relationship to the plot of a piece of literature . In other words, point of view is the perspective from which the story is told.