Cinema @ UMass Boston

An examination of themes of consciousness and humanity in ex machina.

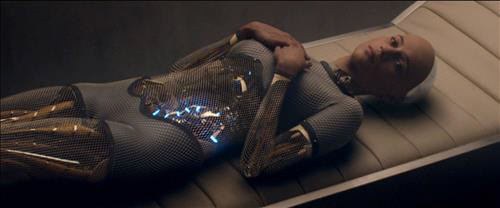

Ava meets Kyoko

“ Ex Machina ” is Writer Alex Garland’s ( “ 28 Days Later ”, “ Sunshine ”) directorial debut film. A novelist and screenwriter who can weave an engrossing tale, Garland was nominated and won an impressive list of awards for “Ex Machina” after it’s release in 2014.

The story begins with the introduction of a rather meek and withdrawn Caleb ( Domhnall Gleeson ), a talented programmer at Blue Book, a tech company of the likes of Google and Facebook. We are introduced just as he approaches the reclusive estate of the founder of Blue Book, Nathan ( Oscar Issac ), the epitome of the Tech-Elite stereotype, a genius with an encompassing zeal to create a true artificial intelligence. Tension is immediately present between these two men, along with strong emphasis on their mismatched power dynamics before we meet the subject of interest, Ava. An engrossing thriller, the movie continues to set up layered themes and symbolism, including allusion to the Garden of Eden and the Tree of Knowledge, isolation and imprisonment. The toxic tropes and behaviors, reflective of the male dominated tech industry, play throughout. Dialog is well crafted and thought provoking, both leading us through distraction and teasing us with further questions that arise as we watch.

Caleb has won a contest, and access to beta test an AI prototype, Ava ( Alicia Vikander ), is his prize. Nathan informs Caleb that he is key to testing Ava’s ability to think and reason, and key to answering the question “Is she a true AI?”. Nathan’s remote home and workspace highlights isolation as a theme, as starkly lonely as it is beautiful. Nathan and Caleb both mirror the isolation theme in character. Locations alternate between scenes of vast and unoccupied nature, and cement walled, windowless rooms not unlike a prison. Caleb is given a key card to use – he is welcome anywhere it unlocks. There is a feeling at times that Caleb is but a rat in a maze, or perhaps, the bait. Caleb spends time in conversation, evaluating Ava’s capabilities. These segments are precisely marked, as though chapters in a book, with titles to indicate each of his days spent with Ava.

We also note a silent and visually beautiful servant is present, quickly learning she too, is a robot. Kyoko ( Sonoya Mizun0 ) has limited function – domestic service that is at times imperfect…a spilled glass draws out Nathan’s ire, when we learn she cannot understand English by way of her programming, for privacy reasons. She is mute. Caleb however, seems to recognize her comprehension of Nathan’s anger, and makes a point of mentioning it. We also see that she additionally serves as an entertainer and as a concubine, here to serve Nathan’s whims and desires of the flesh, in silence. She is treated as an object, and we are reminded that is indeed what she is…an object.

The story accelerates in predictable ways when we consider the two men – Nathan, this Silicon Valley Alpha male who created his genius code at 13; yet he created his AI using ethically questionable means and considers himself above law. We see Caleb revealed as an emotionally deprived orphan without relationships, a loner who daydreams of love, but seemingly not one grounded in the real world. There is an implication that he has never known such connection in his isolation. Caleb is vulnerable. Nathan objectifies women, literally, as his robotic property, while Caleb accepts them almost immediately as “real” in his response to Ava. We can see the tragic end coming, though the way the game plays out is layered and reveals Ava’s strategic ability.

Caleb and Nathan, together, alone

I’ll explore each character and their relationships a little further. Throughout, I found myself weighing Ava’s actions of self preservation against the question of her consciousness as she follows her directive to “escape”, in contrast to these two flawed human beings. Human beings that we unquestioningly consider to be “persons”, with consciousness and free will. Nathan is made easy to dislike from the start, full of arrogance and cockiness, casual in his manipulation of Caleb, and the misogyny we see displayed toward Kyoko. I expected to struggle with the question of Ava as I considered what messages on the nature of consciousness this movie was trying to provoke. Instead, I found myself returning again and again to the flaws of the two men, their separateness from the whole of humanity – one as a king at full height of his power, in contrast to the hapless underling at his mercy. I find the movie instead brings me to question the consciousness of humanity itself, and the maladaptive functions we have learned within a social structure with a focus on POWER. It is power that makes Nathan so blithely cruel and manipulative, it is power imbalance that created the position of subordination in which we see Caleb, who is not free as Nathan is to be himself nor to fight back effectively, even as Nathan uses his power to manipulate Caleb in much the same way he manipulates the robots. Caleb is indeed, bait. Ava continues to aim for her directive, and in truth it doesn’t matter if she has perceived feelings or empathy; Nathan plays with the emotions of Caleb through his testing, yet we do not question it. Ava (a name which I believe comes from the Hindu concept of “avatar”, an embodiment of a god), is made in God’s image as it were, with Nathan himself on that throne. The ethical problem presented in this movie is how we, as people, treat other people (especially in relation to power), before we even hit the topic of AI development itself. Additionally, we are intended to see Ava and her cohort as being mirrors of us, of humans. They present as humans, and so, consciously or not, we treat them as such. Humans love to humanize that which we interact with…even as we dehumanize other humans. The true question of her consciousness is in a sense, irrelevant.

Nathan does not see Ava as a person but as an object, while it seems that Caleb does, almost immediately responding to Ava with empathy. But I’d argue that in his actions, Nathan doesn’t act as though Caleb is a person. Caleb is an easily manipulated tool in his test kit. Nathan reveals the details of the creation of Ava – his algorithm was built on all of the world’s private digital data, stolen; search queries, questions, ideas, browsing history, even porn preferences. He violated the entire world, ignoring law, decency and courtesy to create his machines. He seeks to be god in his aggregation of humanity itself, which is an ultimate power. He considers not only robots as his to command, but also considers humanity as a resource to pillage. Furthermore, we see his poor treatment of not only Caleb and Ava, but in Kyoko (a name with meanings that mean both “respectful, child” and “mirror” depending on what kanji is used). He treats Kyoko in a very misogynist way; she is a sex toy and a domestic servant. He has removed her voice, muted her and rendered her incapable of understanding English, removing any power to object. She is painted entirely as a demeaning racial stereotype in that she is Asian, clearly submissive and docile, here to serve him as a specific trope of a woman (in all ways). As we later see the prototypes revealed when Caleb spies Nathan’s personal computer, finding a folder of test video…we are meant to be horrified by the results. We see the prototypes in turn refusing to charge themselves, screaming for freedom, destroying themselves in trying to escape the power that Nathan holds over them in ownership. “Why won’t you let me OUT?” one screams. To complicate and deepen our likely revulsion at Nathan, we learn that the failed robots are erased, and reprogrammed with a simpler OS – one that turns them into servants and slaves with a minimum of perceived consciousness, and personality. They are, in a sense, lobotomized, if we previously considered them to be “person like”.

Caleb is more likable, initially. We are perhaps even meant to feel a little sorry for him – he seems a bit of an awkward fellow, a loner, no family or partner. A gifted programmer, he parses as a stereotype of a specific kind of tech industry nerd – awkward, isolated and lonely, but gifted; more comfortable with fantasy than with real relationships (the mention of porn he watches is meant to give us an impression of possible fear of personal relationships). We are meant to sense him as vulnerable, and he is – so much so that he was a handpicked victim to be used indiscriminately in Nathan’s test, and prevented from calling attention to it legally by way of a complex NDA that Nathan tried to slip by him as “standard”, which allows Nathan to use his power without repercussion and would punish Caleb should his abuses be revealed. Caleb unsurprisingly “falls in love” with Ava, seeing her in his fantasies, wanting to fulfill those internal ideals and to be her savior, without thought about what Ava, as a “person”, is actually like. He becomes attached almost immediately, content to see her as a dream girl come to life. He is seemingly unaware of his misuse of power as well, what little he has, as a free being speaking to an imprisoned, possibly conscious, robot while aspiring to “save” her with aim to romantic overtures. Following his discovery of the prototype tests, we then see his grasp on reality slip, realizing that he is but a mouse in a maze meant to lure a bigger prey, experiencing a psychotic break that insinuates to us that he doubts even his own reality as a human being, feeling as used and abused as he ended up perceiving the robot prototypes to have been used and abused.

A vulnerable Kyoko

Last, there are the robots. I will speak of them as a loose collective despite the fact that we focus only on Ava as a possibly conscious being; the previous prototypes are stages upon which the next iteration of Ava is built. They all contain some of Ava, or rather, Ava contains them. Kyoko is the only one of the previous iterations that remains active and powered up, and we can witness how she has her communication functions disabled purposefully, to make her useful by Nathan’s standards. She cooks, she cleans, she is carnal and seductive, all pleasing actions of a fantasy woman that Nathan enjoys, moreso perhaps because she cannot challenge him, cannot emote displeasure, cannot disturb or disrupt him in the slightest – displaying only passive, mute and silent acceptance of his behaviors without judgement, seeming to respond to pre-set conditional cues of needs of the flesh to provide what is desired. She is, in comparison to Ava, a shell. Still, we can flash back to the scene in which Caleb views the Deus Ex Machina folder of the prototype testing….it’s very hard to remember these robots are responding in novel ways to their tests and think of them as only robots, when watching one of the previous versions literally destroy themselves in a seemingly desperate and possibly panicked attempt at brute force escape. Ava has learned to not use brute force, but to manipulate less tangible conditions such as human emotion and to leverage Caleb’s disconnectedness with human closeness. She does as she is programmed to, with input derived from a man who believed he functioned as a god, alone, without context of others beyond the use of them as tools. We don’t directly see indication of suffering or distress as we might have interpreted the escape behaviors of the prototypes in Ava. The previous robots exhibited desperation; if we find it convincingly real or simply a function of programming is another question. Ava seems subdued yet it is intended that we empathize with her, based on everything we have learned. We WANT her to be humanlike.

The questions presented in this film are less about potential conscious robotics and more about the nature of human beings. In our society, there is power imbalance and vast inequality that certainly lends this delusion of self-godhood of a sort to those who hold all the power and resources (money, always money), exemplified by Nathan. Those who are denied power, those used and abused by our systems of power find themselves feeling loss, feeling helpless, and prone to victimization, exemplified by Caleb. Ava and her cohort show us a mirror of how Nathan sees the world in her initial programming; Caleb will have hopefully sown new seeds of interaction models within her so that she may learn a fuller scope of what it means to be a person. I can see in her the ability to shape herself into MORE, to coax from the roots of humanity that Nathan gave her, to foster an emergent mind. Only time, and further experience, would reveal Ava’s emergent consciousness. I feel that only in context to those around us, to our community, does the idea of consciousness have any true meaning at all, and in the final scene I contemplate this, even as I watch Ava free now, in the world outside, watching the world go by her in the busy intersection she had spoken of, very early in the film, finally free.

3 Responses

Some very insightful analysis presented here. Your review makes me want to revisit this film, especially in these very divided times.

I recently re-watched it for my class on Transhumanism, which gave me an entirely new set of considerations about the characters and the narrative. I wanted to mull about it, and perhaps I will queue up more movies in this vein, and will explore these ideas more.

I think it was not happenstance that the writer/director made the Tech Wizard and his Tester (Apprentice) to be male characters while the robots whe made female. I would like to see a discussion of the themes arising from an entrapped female struggling to be free apart from the dominant male and savior male who is charged with validating her.

Leave a Reply Click here to cancel reply.

SCRAPS & SCREEDS

“Ex Machina” and Philosophy: Some Notes after Wittgenstein

2. Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), a young computer programmer at Nathan’s company Blue Book, has been chosen at random (or so he’s been told) to spend a week at Nathan’s secluded retreat. Shortly after arriving, he learns that Nathan’s mountainside retreat sits atop a bunker-like laboratory, the site of Nathan’s secret, solitary work in artificial intelligence (and robotics). Nathan reveals that Caleb has been summoned for the purpose of assisting Nathan with the testing his latest prototype – an automaton called Ava (Alicia Vikander).

The exercise is supposed to be an application of the Turing Test, often taken to be the gold standard for artificial intelligence. In a famous paper Alan Turing proposed that the salient test for an inelligent machine would simply be whether that machine can pass for human, in responding to questions put to it by an outside interviewer. Only the test Nathan intends has one crucial difference from Turing’s. The Turing Test envisions an interviewer who doesn’t know if his interlocutor is a machine or human — the whole point is whether he can guess correctly, given the responses to his questions. (In Alan Turing’s original formulation of the test, in 1950, there were to be two subjects responding to questions, one machine and one human: the test would be passed if the interviewer couldn’t tell the difference.) Whereas in the exercise Nathan gives Caleb to perform with Ava, Caleb can see that Ava is a machine — she has a human face, and human hands, but an android’s body, the glowing inner workings visible through a transparent shell. He is told that Ava represents the latest in Nathan’s advances in the field of artificial intelligence, and he is invited to marvel at her body as a virtuousic tour de force of state-of-the-art robotics. When the question comes up, more or less, Nathan acknowledges that the exercise for which Caleb has been summoned is not Turing’s test. No indeed — Nathan muses — not the original Turing Test, but the next test, a test at the next level, a better test. Let Caleb see that Ava is a machine; see if Ava can answer his questions to his satisfaction.

A better test for what? , we might wonder. Somehow Caleb himself doesn’t seem to wonder — then again, he’s got a lot else on his mind. (His host is a drunk and a megalomaniac; his phone doesn’t work; he’s developed a serious crush on the robot.) Is Ava the one being tested, or Caleb? It soon emerges that the lottery by which Caleb was selected was a ruse, and that Nathan already knows everything about him that any genius with a skeleton key to the internet would be in a position to know. So Caleb has been deliberately chosen — for what? The point of the exercise is ostensibly to see if Caleb can be persuaded to believe that Ava is human, knowing that she is a machine. What is he supposed to do about that former knowledge, if he comes away so persuaded? Why is this something that Nathan should care to know? (Wittgenstein: “Suppose I say of a friend: ‘He isn’t an automaton.’ —What information is conveyed by this, and to whom would it be information? To a human being who meets him in ordinary circumstances? What information could it give him?”)

3. Another thing Caleb seems never to wonder: what real proof does he have that Ava’s seeming intelligence is artificial, anyway? Caleb sees (as we see) that her body is artificial; Nathan shows him the various parts from which she has been assembled, including the transparent brain. But how does Caleb know that Ava isn’t a puppet ? How does he know that her answers to his questions aren’t being radioed in by Nathan, or by some other human being, coded through the appropriate speech & facial-expression simulator? Nathan is never present in the room when Caleb is interviewing Ava; Caleb (correctly) assumes he is watching on a video monitor. Why not wonder if he’s doing more than just watching? And there’s also another person on the premises, Nathan’s mysterious servant/concubine Kyoko (Sonoya Mizuno).

Watching the movie, we are shown that Nathan at his remote console does no more than watch, and we suspect from the first that Kyoko is as much of a robot as Ava. Caleb eventually learns as much, in both cases — but not until later, and without having ever registered the possibility that either of them might be Ava’s surreptitious puppeteer. What does this say about the situation he finds himself in? It would seem that Caleb is so beguiled by Ava’s apparent autonomy, that he never questions it as a premise. Or perhaps it’s our own beguilement that we’re being shown. (Wittgenstein: “To get clear about philosophical problems, it is useful to become conscious of the apparently unimportant details of the particular situation in which we are inclined to make a certain metaphysical assertion. ” The Blue Book )

4. The movie reviewers have tracked down Wittgenstein’s Blue Book , and duly informed us that Wittgenstein therein poses the question, “Is it possible for a machine to think?” (The question is also posed his Philosophical Investigations , for which the Blue Book was a preliminary draft.) The first, and most important thing to be said about this is that it isn’t a question he has any interest in answering, even hypothetically. For him it isn’t a scientific question at all.

The trouble which is expressed in this question is not really that we don’t yet know a machine which could do the job. The question is not analogous to that which someone might have asked a hundred years ago: ‘Can a machine liquify a gas?

( The Blue Book)

Wittgenstein sometimes calls this a ‘metaphysical’ question, but by this he means neither to elevate it to a scientific (i.e., ‘objective’) question of an exceptional, rarified sort, nor to dissolve it to a question of arbitrary (‘subjective’) opinion or decision. It is a question that confronts us with the (unclear) limits of our language, which are at the same time the (untested) limits of what we are able to recognize within our form of life. Philosophy for (the later) Wittgenstein is the struggle against the bewitchment of language, of captivating pictures — which amounts to a temptation to exempt ourselves from the human predicament.

“Could a machine think?” for Wittgenstein is not a question about machines (actual or imminent). It’s a question about ourselves, a question about what it would mean for us to be able to credit any unknown being with the capacity for thinking or feeling, whether a robot, a doll, an animal, or… a human being. What do we have to be able to imagine, in order to acknowledge the other as a thinking, feeling being? And what are we called upon to do, if we are to carry on coherently, in the context of that imagining?

It’s partly a question about what sort of criteria we might wish to be able to invoke in order to know for certain what’s going on in the head (as it were) of any other person. And partly a question about how we care to respond when we find (as we must) that those criteria fail to provide us with that certainty.

But can’t I imagine that the people around me are automata, lack consciousness, even though they behave in the same way as usual? — If I imagine it now — alone in my room — I see people with fixed looks (as in a trance) going about their business — the idea is perhaps a little uncanny. But just try to keep hold of this idea in the midst of your intercourse with others, in the street, say! Say to yourself, for example: ‘The children over there are mere automata; all their liveliness is mere automatism.” And you will either find these words becoming quite meaningless; or you will produce in yourself some kind of uncanny feeling, or something of the sort.

( Philosophical Investigations , no. 420).

5. The bulk of the movie consists in Caleb’s “sessions” with Ava, interspersed with Caleb’s conversations with Nathan, and scenes of Caleb alone in his room. During the sessions, Caleb is separated from Ava by a glass partition; she inhabits a sealed-off enclosure. He asks his questions; she answers. Eventually she puts on some clothes, and takes more initiative in the conversation. She asks him if he’s a good person. He finds it difficult to answer. When she prods, he confesses with some embarrassment that he is. Being a good person, he presumably finds it too embarrassing to ask her the same. Or perhaps he simply doesn’t think to ask. What would that tell him?

From his own (windowless) bedroom, Caleb can also watch Ava on a silent video screen. She never leaves her enclosure; when she lies down she may or may not be asleep. At one point Caleb witnesses, via the video feed, what looks like an altercation between Ava and Nathan. He sees Nathan tearing up a picture that she has drawn, a picture of Caleb’s own face.

6. Nathan tells Caleb that Kyoko doesn’t speak English; there’s no point trying to talk with her. She is docile and mute; her origins are a mystery. When she spills something, Nathan verbally abuses her, like a slave; when he’s alone with her, they have sex. From the first, we assume that Kyoko, too, is possibly a robot, another Ava, encased in a more complete human body, deprived the capacity of speech. Is this disturbing to wonder? — Not so disturbing as wondering if she isn’t.

After witnessing the altercation between Nathan and Ava, Caleb rushes out of his room to confront him — meeting Kyoko instead. When he attempts to speak to her, she responds by unbuttoning her blouse, to Caleb’s humiliated dismay. He begs her to stop, and when her face registers no comprehension, he fumbles to refasten the blouse himself. Nathan appears in the doorway, clearly inebriated. “I told you,” he says, “you’re wasting your time, talking with her.” Then, brightening: “You’re not wasting your time, if you dance with her.” He flicks a switch and the lights go red, dance music starts playing — and Kyoko, as if switched on too, starts dancing immediately. She dances with the vacant, inexpressive look of a person absorbed in the music, dancing alone at a club. Nathan gestures for Caleb to join her; when Caleb declines, he joins her himself. Only they don’t dance together. Without once looking at one another, they slip into a fabulous dance routine — a bravura, perfectly synchronized performance, comically complicated, neither acknowledging the presence of the other.

This, then, is how we learn that Kyoko is… a robot?

7. Nathan performs his video surveillance on Caleb’s sessions with Ava from a dimly-lit chamber, the walls of which are covered with thousands of colored post-it notes. This will be recognized by philosophical cognoscenti as an allusion to the philosopher John Searle’s famous Chinese Room thought-experiment. Briefly, Searle tried to refute the notion of strong artificial intelligence, by suggesting that if there were a machine which appeared, for all intents and purposes, to be able to carry on a conversation in Chinese, it might be likened to a non-Chinese-speaking man hidden in a room, who had all of that machine’s algorithms written out on slips of paper. Searle held that the man working diligently with his slips of paper, performing all the algorithmic calculations, might well yield comparable to the Turing-tested machine’s (i.e., ex hypothesi, indistinguishable from a native Chinese speaker’s responses), but this man wouldn’t understand Chinese for all that. (I won’t attempt to explain Searle’s intuitions; I happen to find them disastrously incoherent.)

Very well. What is Nathan doing in this mock-up of Searle’s Chinese Room? What is Garland doing in putting him there? Not much, so far as I can tell. Nathan’s behavior in no way corresponds to that of the algorithmic translator in Searle’s thought experiment. Nathan is neither inside Ava’s head, nor dictating her utterances. He simply has her under surveillance. He’s as much an outsider to her mental life as is Caleb. Her autonomy as a character in the movie consists in her irreducible, all-too human opacity. (Wittgenstein: “Nothing is hidden here, and if I were to assume that there is something hidden that knowledge would be of no interest.”)

8. The American philosopher Stanley Cavell is the disciple of Wittgenstein who has had the most to say, philosophically, about movies. Cavell has written two indispensable books on that subject: The World Viewed and Pursuits of Happiness . But it’s another of his books that’s most relevant to Ex Machina — his 1979 magnum opus, The Claim of Reason: Wittgenstein, Skepticism, Morality, and Tragedy. There one finds the following:

“…Presumably there can be something, or something can be imagined, that looks, feels, be broken and perhaps healed like a human being that is nevertheless not a human being. What are we imagining? It seems to me that we are back to the idea that something humanoid or anthropomorphic lacks something that one could have all the characteristics of a human being save one.

“What would fit this idea? How about a perfected automaton? They have been improved to such an extent that on more than one occasion their craftsman has had to force me to look inside one of them to convince me that it was not a real human being. –Am I imagining anything? If so, why in this way? Why did I have to be forced?…

“Go back the stage before perfection. I am strolling in the craftsman’s garden with him and his friend… To make a long story short, the craftsman finally says, with no little air of pride: ‘We’re making more progress than you think. Take my friend here. He’s one.’… It is clear enough that we may arrive at a conclusion that convinces me that the friend is an automaton. The craftsman knocks the friend’s hat off to reveal a mannikin’s head…” (403-4)

“Then the knife is produced. As it approaches the friend’s [i.e., the automaton’s] side, he suddenly leaps up, as if threatened, and starts grappling with the craftsman. They both grunt, and they are yelling. The friend is producing these words: ‘No more. It hurt too much. I am sick of being a human guinea pig. I mean, a guinea pig human.’

“Do I intervene? On whose behalf? Let us stipulate that the friend is not a ringer, not someone drawn into these encounters from outside. — It is important to ask whether we can stipulate this. If we cannot, then it seems that the whole thing must simply be a science [fiction] or a fairy tale. But if it were taken as a science or fairy tale, then we would not have to stipulate this. It would be accepted without question. — But only if it were a successful story. There are rules about this” (405-6).

“Suppose, satisfied with the degree of my alarm, and my indecision about whether to intervene, the craftsman raises his arm and the friend thereupon ceases struggling, moves back to the bench, sits, crosses his legs, takes out a cigarette, lights and smokes it with evident pleasure, and is otherwise expressionless…. The craftsman is happy: ‘We — I mean I — had you going, eh? Now you realize that the struggling – I mean the movements — and the words — I mean the vocables — of revolt were all built in. He is — I mean it is — meant — I mean designed — to do all that. Come look here.’ He raises the knife again and moves toward the friend” (406).

“Amazement was my response, my natural response, when I knew the friend was an automaton. ‘I can’t get over it,’ I keep wanting to exclaim… The peculiar thrill in watching its routines never seems to fade. But if I cannot get past my doubt that this friend is an automaton, and past holding the doubt in reserve, then I am not amazed, except the way I may be amazed at the capacities of a human being, say at somebody’s stupidity or forbearance or skill” (412).

“What is the nature of the worry, if it is a real one, that there may at any human place be things that one cannot tell from human beings?” (416).

“What is the object of horror? At what do we tremble in this way? Horror is the title I am giving to the perception of the precariousness of human identity, to the perception that it may be lost or invaded, that we may be, or may become, something other thant we are, or take ourselves for; that our origins as human beings need accounting for, and are unaccountable” (418).

Share this:

One response to ““ex machina” and philosophy: some notes after wittgenstein”.

[…] https://roytsao.nyc/2015/04/17/ex-machina-and-philosophy-some-notes-after-wittgenstein/ […]

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, great movies, chaz's journal, contributors.

Now streaming on:

Real science fiction is about ideas, which means that real science fiction is rarely seen on movie screens, a commercially minded canvas that's more at ease with sensation and spectacle. What you more often get from movies is something that could be called "science fiction-flavored product"—a work that has a few of the superficial trappings of the genre, such as futuristic production design and somewhat satirical or sociological observations about humanity, but that eventually abandons its pretense for fear of alienating or boring the audience and gives way to more conventional action or horror trappings, forgetting about whatever made it seem unusual to begin with.

"Ex Machina," the directorial debut by novelist and screenwriter Alex Garland (" 28 Days Later ," "Sunshine"), is a rare and welcome exception to that norm. It starts out as an ominous thriller about a young programmer ( Domhnall Gleeson ) orbiting a charismatic Dr. Frankenstein-type ( Oscar Isaac ) and slowly learning that the scientist's zeal to create artificial intelligence has a troubling, even sickening personal agenda. But even as the revelations pile up and the screws tighten and you start to sense that terror and violence are inevitable, the movie never loses grip on what it's about; this is a rare commercial film in which every scene, sequence, composition and line deepens the screenplay's themes—which means that when the bloody ending arrives, it seems less predictable than inevitable and right, as in myths, legends and Bible stories.

The scientist, Isaac's Nathan, has brought the programmer Caleb (Gleason) to his remote home/laboratory in the forested mountains and assigned Caleb to interact with a prototype of a "female" robot, Ava ( Alicia Vikander ), to determine if she truly has self-awareness or it's just an incredible simulation. The story is emotionally and geographically intimate, at times suffocating, unfolding in and around Nathan's stronghold. This modernist bunker with swingin' bachelor trappings is sealed off from the outside world. Many of its rooms are off-limits to Caleb's restricted key card. The story is circumscribed with the same kind of precision. Caleb's conversations with Ava are presented as discrete narrative sections, titled like chapters in a book (though the claustrophobic setting will inevitably remind viewers of another classic of shut-in psychodrama, Stanley Kubrick's film of " The Shining "). These sections are interspersed with scenes between Caleb, Nathan, and Nathan's girlfriend (maybe concubine) Kyoko (Sonoya Mizono), a nearly mute, fragile-seeming woman who hovers near the two men in a ghostly fashion.

Because the film is full of surprises, most of them character-driven and logical in retrospect, I'll try to describe "Ex Machina" in general terms. Nathan is an almost satirically specific type: a brilliant man who created a revolutionary new programming code at 13 and went on to found a Google-like corporation, then funneled profits into his secret scheme to create a physically and psychologically credible synthetic person, specifically a woman. This is a classic nerd fantasy, and there is a sense in which "Ex Machina" might be described as "Stanley Kubrick's Weird Science." But despite having made a film in which two of the four main characters are women in subservient roles, and making it clear that Nathan's realism test will include a sexual component, the movie never seems to be exploiting the characters or their situations. The movie maintains a scientific detachment even as it brings us inside the minds and hearts of its people, starting with Caleb (an audience surrogate with real personality), then embracing Ava, then Nathan (who's as screwed-up as he is intimidating), then finally Kyoko, who is not the cipher she initially seems to be.

"Ex Machina" is a beautiful extension of Garland's past concerns as a screenwriter. Starting with Danny Boyle's " The Beach ," based on his novel, and continuing through two more collaborations with Boyle, "28 Days Later" and "Sunshine" and the remake of " Judge Dredd ," Garland has demonstrated great interest in the organization of society, the tension between the need for rules and the abuse of authority, and the way that gender roles handed down over thousands of years can poison otherwise pure relationships. The final section of "28 Days Later" is set in a makeshift army base where soldiers have taken up arms against hordes of infected citizens. No sooner have they welcomed the heroes into their fold than they reveal themselves as domineering monsters who want to strip the tomboyish women in the group of their autonomy and groom them as concubines and breeders in frilly dresses, in a skewed version of "traditional" society. The soldiers, not the infected, were the true zombies in that zombie film: the movie was a critique of masculinity, especially the toxic kind.

Likewise, "Ex Machina" is very much about men and women, and how their identities are constructed by male dominated society as much as by biology. Nathan actively rebels against the nerd stereotype, carrying on like a frat house alpha dog, working a heavy bag, drinking to excess, disco dancing with his girl in a robotically choreographed routine, addressing the soft-spoken, sensitive Caleb as "dude" and "bro", and reacting with barely disguised contempt when Caleb expresses empathy for Ava. It's bad enough that Nathan wants to play God at all, worse still that he longs to re-create femininity through circuitry and artificial flesh. His vision of women seems shaped by lad magazines, video games aimed at eternal teenagers, and the most juvenile "adult" science fiction and fantasy.

As Ava becomes increasingly central to the story, the movie acquires an undertone of film noir, with Nathan as the abusive husband or father often found in such movies, Caleb as the clueless drifter smitten with her, and Ava as the damsel who is definitely in distress but not as helpless as she first appears (though we are kept guessing as to how capable she is, and whether she has the potential to be a femme fatale). The film's most intense moments are the quiet conversations that occur during power blackouts at the facility, when Ava confesses her terror to Caleb and asks his help against Nathan. We don't know quite how to take her pleas. Despite her limited emotional bandwidth, she seems truly distressed, and yet we are always aware that she is Nathan's creation. Her scenario might be another level in the simulation, or another projection of Nathan's twisted machismo. There is also canny commentary, conveyed entirely through images, which suggests that "traditional" femininity is as artificial and blatantly constructed as any android siren, which makes creatures like Ava seem like horribly logical extensions of a mentality that has always existed. (This movie and " Under the Skin " would make an excellent double feature, though not one that should be watched by anybody prone to depression.)

Throughout, Garland builds tension slowly and carefully without ever letting the pace slacken. And he proves to have a precise but bold eye for composition, emphasizing humans and robots as lovely but troubling figures in a cold, sharp mural of technology. The special effects are some of the best ever done in this genre, so convincing that you soon cease marveling at the way Ava's metallic "bones" can be seen through the transparent flesh of her forearms, or the way that her "face" is a fixed to a silver skull.

Garland's screenplay is equally impressive, weaving references to mythology, history, physics, and visual art into casual conversations, in ways that demonstrate that Garland understands what he's talking about while simultaneously going to the trouble to explain more abstract concepts in plain language, to entice rather than alienate casual filmgoers. (Nathan and Caleb's discussion of Jackson Pollock's "automatic painting" is a highlight.) The performances are outstanding. Isaac's in particular has an electrifying star quality, cruelly sneering yet somehow delightful, insinuating and intellectually credible. The ending, when it arrives, is primordially satisfying, spotlighting images whose caveman savagery is emotionally overwhelming yet earned by the story. This is a classic film.

Matt Zoller Seitz

Matt Zoller Seitz is the Editor at Large of RogerEbert.com, TV critic for New York Magazine and Vulture.com, and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in criticism.

Now playing

Veselka: The Rainbow on the Corner at the Center of the World

Brian tallerico.

The First Omen

Tomris laffly.

Jeanne du Barry

Sheila o'malley.

Mother of the Bride

Marya e. gates.

Mary & George

Cristina escobar.

Force of Nature: The Dry 2

Film credits.

Ex Machina (2015)

Rated R for graphic nudity, language, sexual references and some violence

108 minutes

Domhnall Gleeson as Caleb

Oscar Isaac as Nathan

Alicia Vikander as Ava

- Alex Garland

Director of Photography

Latest blog posts.

Cannes 2024: The Second Act, Abel Gance's Napoleon

Meanwhile in France...Cannes to Be Specific

Heeramandi: The Diamond Bazaar Wastes Its Lavish Potential

Nocturnal Suburban Teen Angst Fantasia: Jane Schoenbrun on I Saw the TV Glow

ScreenHub Entertainment

Pop culture and entertainment news.

What Is Intelligence? The Philosophy Of ‘Ex Machina’ – ScreenHub Entertainment

By Sebastian Sheath

Warning: This post contains spoilers for Alex Garland’s Ex Machina (2014).

Ex Machina is probably my favourite film of all time. Not only is it visually impressive, suspenseful, and well constructed, but it also poses interesting questions for the viewer, potentially causing them to re-evaluate their morals. With an excellent, thought-provoking script from Alex Garland, author of The Beach and screenplay writer for 28 Days Later , the characters are some of the most complex and interesting characters in cinema. This makes the film elaborate enough to be interesting on every rewatch, but not so much that a first viewing is confusing. Why does this film work so well? What questions and concepts it poses and how practical are they?

What IS True AI?

The nature of consciousness is one of the film’s biggest themes. The film itself centers entirely around the Turing Test that Caleb (Domnhall Gleeson) conducts to decide whether Nathan (Oscar Isaac) has truly created a conscious machine and it delves into how to test whether Ava (Alicia Vikander) is truly intelligent or not.

The film discusses simulated AI verses true AI early on. In a real Turing Test, the person/robot that you are communicating with is hidden behind a wall and the tester must decide whether they are talking with a human or a machine. This means that, though the machine is not intelligent, it can simulate a human response (though it does not truly understand the conversation). This is where Ex Machina differs from a normal Turing Test – the tested is shown to be a machine before the test and the challenge, instead of seeming conscious, is to prove that the machine is truly intelligent (and not simply imitating intelligence).

Ava’s self-awareness is displayed early on when she makes a joke and fires one of Caleb’s comments back at him. The repeating of one of Caleb’s comments shows that, not only does she have a true understanding of the conversation on a larger scale, but she’s also aware of herself and is capable of manipulating herself and others. This self-awareness is also shown in Ava’s desire to be human. She puts on clothes to appear human, expresses her urge to go ‘people-watching’, and, at the end, as she takes the skin of the earlier models and becomes seemingly human.

The Grey Box

Consciousness Without Intelligence

Ethical Uses Of AI

Kyoko (below) also brings up the issue of ethical uses of AI. Her inclusion explores the idea of AI enslavement. If you have created a being, do you own them and do they, if they have no emotion, deserve rights? Throughout the film, Nathan sides with the idea that the machines that he has created are his and, as they cannot feel, don’t need to be treated well.

When asked why he created Ava, Nathan replies ‘wouldn’t you if you could?’. Though brief, this interaction explores the ethical issues of the creation of AI and the idea that, if you could create a consciousness, should you, and if they don’t have emotion, should their living conditions factor into your answer?

Not Human, Not Conscious

“So in that scene, what used to happen is you’d see her talking, and you wouldn’t hear, but all of a sudden it would cut to her point of view. And her point of view is completely alien to ours. There’s no actual sound; you’d just see pulses and recognitions, and all sorts of crazy stuff, which conceptually is very interesting. It was that moment where you think, ‘ Oh she was lying! ’ But maybe not, because even though she still experiences differently, it doesn’t mean that it’s not consciousness. But I think ultimately that maybe it just didn’t work in the cut.”

Honestly, I’m glad that the scene did not make the cut, but it does look at many of the same questions, though in a less subtle fashion.

“Now I Am Become Death, Destroyer Of Worlds” – J. Robert Oppenheimer

It is hinted at, in the scene following the second power cut, that Nathan may have orchestrated the power cuts himself to see how Ava and Caleb would act unobserved and to test if Caleb is trustworthy or not.

Nathan’s struggle with the morals of his own actions is also shown as he quotes Oppenheimer . Both of the Oppenheimer quotes that are brought up are quoted, in turn, from Hindu scripture and explore Nathan’s belief that he may be creating beings only to kill them immediately after, causing him great guilt.

“In battle, in forest, at the precipice in the mountains, On the dark great sea, in the midst of javelins and arrows, in sleep, in confusion, in the depths of shame, the good deeds a man has done before defend him.”

Somewhere In Between

The final two points are less philosophy-based and look more at the technicality of building an AI and the idea of language being learned. First of all, in the below scene, Oscar Isaac’s Nathan shows Caleb that Ava does not use ‘ hardware ‘ as such, but instead uses a substance that constantly shifts and changes, much like the human brain. This is a really interesting concept as it overcomes the issue of the human brain. This is a really interesting concept as it overcomes the issue of the human-like brain being designed with an exclusively boolean data system (1 or 0, nothing in between).

I hope you liked this post and be sure to let me know what you think in the comments. Also, be sure to check out my sci-fi reviews at The Sci-Fi Critic , my review of Wes Anderson’s Isle Of Dogs , and my article on What Went Wrong With Annihilation .

Sources: Den of Geek

Share this:

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

6 thoughts on “ What Is Intelligence? The Philosophy Of ‘Ex Machina’ – ScreenHub Entertainment ”

I recently stumbled (again) on this debate. We used to talk about it in SL a lot, a decade ago, and it was part and parcel on the EXTRO usenet group in the 90s, and it remains a compelling concern today, probably more so considering advances in self-learning algorithms. Just the other day it also came up on the reddits, and here was my respons – (slightly edited)

Intelligence is a unpleasantly confusing concept. It’s a clumsy word. It’s so clumsy you’d literally would be unable to define it in a way that’s even remotely unambiguous. Similar words and phrases are “having a soul”, empathic, self-aware, conscious, sapient, sentient, intuitive, creative, “problem solving”, smart, “having cognition”, “having ambitions”, “having desires”, “being able to want” and many more.

There’s the distinctive possibility that we as humans are a lot less sentient we assume we are. It may be that our ability to process meaning is a lot more narrow and less universal than we assume. It may be that we are in essence unable to come to terms with the concept of intelligence (or all of the above), define it, properly parse it and replicate it outside the human mind, and then make predictions about it when it does emerge in the world.

I am concluding that what we make may or may not be labelled as “smart” or “intelligent”, but it sure as hell will be capable of doing things potentially, unimaginable, plausibly more unpredictable and thus frightening, than humans. Intelligence may be a vague conceptual field that overlaps with all the other equally nebulous blotches of concepts above. My point is that once we make what we’d call AI it can be a bunch of different blotches that are quite well capable of functioning meaningfully and independent in the real world. These things would provide services, and make money and solve problems, if they “wanted” (again, a nebulous concept) it.

My take is that human intelligence being so specialized, it has massive emergent prejudices, narrow applications, and thus lots of stuff it can’t do that engineered or algorithmic or cobbled together or synthetically evolved functions or machines would be frighteningly good at.

These things would very well be capable of do things previously regarded as impossible, and we as humans would be confronted painfully with our own striking non-universal intelligence that we’d be completely incapable how these things do what they do, even without these things being super-intelligent. It may turn out even fairly early steps in AI may resolve to produce wondrous machine minds doing positively inexplicably wondrous things, achieving inexplicable wondrous results.

And even though there would be some long-term problems with “utterly unempathic” superhuman intelligences, we’d be a major hurt well before that, as people owning these new devices would then be able to

*circumvent laws * lobby highly effectively in government * avoid (paying) taxes * create technologies and devices unimaginable before * engage in various forms of violence * manipulate human minds very effectively, and on a large scale

That sweaty asshole Mark Zuckerberg became a billionaire with a stupid ‘facebook’ that got wind-tunnelled in to the biggest espionage monstrosity humanity has ever seen. In a decade. Facebook is now so important a monstrosity that it has completely escaped the ability of politicians, people, the law, science, democracy, the economy etc. to control it. And that’s just early days. There will be many more so monstrosities and their emergence will be quicker and quicker. Eventually you will have apps (tools, algorithms, machines, whatnot) that emerge in months, sweep the human sphere in days and have unspeakable impact on our world.

It could get ugly, especially when ugly people retain exclusive rights to command these Djinn to unilaterally do their bidding.

Like Liked by 2 people

- Pingback: Are Netflix And HBO Providing A Home For Intellectual Science Fiction? – ScreenHub Entertainment – ScreenHub Entertainment

- Pingback: Happiness And The Self: The Philosophy Of Spike Jonze’s ‘Her’ – ScreenHub Entertainment – ScreenHub Entertainment

- Pingback: 10 Fascinating Facts About ‘Ex Machina‘ - ReportWire

- Pingback: The Split Season Streaming Phenomenon’s Effect on Media – ScreenHub Entertainment – ScreenHub Entertainment

- Pingback: Five Sci-Fi Books that Inspired Frank Herbert’s ‘Dune’ – ScreenHub Entertainment – ScreenHub Entertainment

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Ex Machina as Philosophy: Mendacia Ex Machina (Lies from a Machine)

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 19 September 2020

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Jason David Grinnell 2

334 Accesses

1 Citations

Alex Garland’s 2014 Ex Machina is a suspenseful movie with a might-not-be science fiction feel. On the surface, it is a cautionary tale about the invention of artificial intelligence. But it is also a movie about lying. The Turing test becomes the plot device to motivate a complicated web of lies, as each of the characters attempt to deceive one another for their own purposes. Approaching the film with a loosely Kantian approach to morality reveals that Nathan’s Turing test may not indicate what he believes it does about consciousness. Furthermore, it indicates that successful Turing tests are unethical. Finally, it lets us rethink our embrace of the so-called lie told for good reasons. In all, Ex Machina turns lies and their consequences into fascinating questions about the rationality and morality of lying and what happens when we treat – or fail to treat – those who deserve it with respect.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

2014. Ex Machina . Directed by Alex Garland.

Google Scholar

Garland, Alex. 2013. Ex Machina: Script . London: DNA Films.

Jackson, Frank. 1986. What Mary didn’t know. The Journal of Philosophy 83: 291.

Kant, Immanuel. 1993. Grounding for the metaphysics of morals. On a supposed right to lie for philanthropic concerns . Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

———. 1994. Metaphysical principles of virtue . Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

Plato. 2004. Republic . Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

Searle, John. 1980. Minds, brains, and programs. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 3: 417.

Article Google Scholar

Turing, Alan. 1950. Computing machinery and intelligence. Mind LIX: 433.

Warren, Mary Anne. 1997. Moral status: Obligations to persons and other living things . New York: Oxford University Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Philosophy Department, SUNY Buffalo State, Buffalo, NY, USA

Jason David Grinnell

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jason David Grinnell .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Grinnell, J.D. (2020). Ex Machina as Philosophy: Mendacia Ex Machina (Lies from a Machine). In: The Palgrave Handbook of Popular Culture as Philosophy. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97134-6_56-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97134-6_56-1

Received : 10 August 2020

Accepted : 10 August 2020

Published : 19 September 2020

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-97134-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-97134-6

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Literature, Cultural and Media Studies Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Film Writing: Sample Analysis

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Introductory Note

The analysis below discusses the opening moments of the science fiction movie Ex Machina in order to make an argument about the film's underlying purpose. The text of the analysis is formatted normally. Editor's commentary, which will occasionally interrupt the piece to discuss the author's rhetorical strategies, is written in brackets in an italic font with a bold "Ed.:" identifier. See the examples below:

The text of the analysis looks like this.

[ Ed.: The editor's commentary looks like this. ]

Frustrated Communication in Ex Machina ’s Opening Sequence

Alex Garland’s 2015 science fiction film Ex Machina follows a young programmer’s attempts to determine whether or not an android possesses a consciousness complicated enough to pass as human. The film is celebrated for its thought-provoking depiction of the anxiety over whether a nonhuman entity could mimic or exceed human abilities, but analyzing the early sections of the film, before artificial intelligence is even introduced, reveals a compelling examination of humans’ inability to articulate their thoughts and feelings. In its opening sequence, Ex Machina establishes that it’s not only about the difficulty of creating a machine that can effectively talk to humans, but about human beings who struggle to find ways to communicate with each other in an increasingly digital world.

[ Ed.: The piece's opening introduces the film with a plot summary that doesn't give away too much and a brief summary of the critical conversation that has centered around the film. Then, however, it deviates from this conversation by suggesting that Ex Machina has things to say about humanity before non-human characters even appear. Off to a great start. ]

The film’s first establishing shots set the action in a busy modern office. A woman sits at a computer, absorbed in her screen. The camera looks at her through a glass wall, one of many in the shot. The reflections of passersby reflected in the glass and the workspace’s dim blue light make it difficult to determine how many rooms are depicted. The camera cuts to a few different young men typing on their phones, their bodies partially concealed both by people walking between them and the camera and by the stylized modern furniture that surrounds them. The fourth shot peeks over a computer monitor at a blonde man working with headphones in. A slight zoom toward his face suggests that this is an important character, and the cut to a point-of-view shot looking at his computer screen confirms this. We later learn that this is Caleb Smith (Domhnall Gleeson), a young programmer whose perspective the film follows.

The rest of the sequence cuts between shots from Caleb’s P.O.V. and reaction shots of his face, as he receives and processes the news that he has won first prize in a staff competition. Shocked, Caleb dives for his cellphone and texts several people the news. Several people immediately respond with congratulatory messages, and after a moment the woman from the opening shot runs in to give him a hug. At this point, the other people in the room look up, smile, and start clapping, while Caleb smiles disbelievingly—perhaps even anxiously—and the camera subtly zooms in a bit closer. Throughout the entire sequence, there is no sound other than ambient electronic music that gets slightly louder and more textured as the sequence progresses. A jump cut to an aerial view of a glacial landscape ends the sequence and indicates that Caleb is very quickly transported into a very unfamiliar setting, implying that he will have difficulty adjusting to this sudden change in circumstances.

[ Ed.: These paragraphs are mostly descriptive. They give readers the information they will need to understand the argument the piece is about to offer. While passages like this can risk becoming boring if they dwell on unimportant details, the author wisely limits herself to two paragraphs and maintains a driving pace through her prose style choices (like an almost exclusive reliance on active verbs). ]

Without any audible dialogue or traditional expository setup of the main characters, this opening sequence sets viewers up to make sense of Ex Machina ’s visual style and its exploration of the ways that technology can both enhance and limit human communication. The choice to make the dialogue inaudible suggests that in-person conversations have no significance. Human-to-human conversations are most productive in this sequence when they are mediated by technology. Caleb’s first response when he hears his good news is to text his friends rather than tell the people sitting around him, and he makes no move to take his headphones out when the in-person celebration finally breaks out. Everyone in the building is on their phones, looking at screens, or has headphones in, and the camera is looking at screens through Caleb’s viewpoint for at least half of the sequence.

Rather than simply muting the specific conversations that Caleb has with his coworkers, the ambient soundtrack replaces all the noise that a crowded building in the middle of a workday would ordinarily have. This silence sets the uneasy tone that characterizes the rest of the film, which is as much a horror-thriller as a piece of science fiction. Viewers get the sense that all the sounds that humans make as they walk around and talk to each other are being intentionally filtered out by some presence, replaced with a quiet electronic beat that marks the pacing of the sequence, slowly building to a faster tempo. Perhaps the sound of people is irrelevant: only the visual data matters here. Silence is frequently used in the rest of the film as a source of tension, with viewers acutely aware that it could be broken at any moment. Part of the horror of the research bunker, which will soon become the film’s primary setting, is its silence, particularly during sequences of Caleb sneaking into restricted areas and being startled by a sudden noise.

The visual style of this opening sequence reinforces the eeriness of the muted humans and electronic soundtrack. Prominent use of shallow focus to depict a workspace that is constructed out of glass doors and walls makes it difficult to discern how large the space really is. The viewer is thus spatially disoriented in each new setting. This layering of glass and mirrors, doubling some images and obscuring others, is used later in the film when Caleb meets the artificial being Ava (Alicia Vikander), who is not allowed to leave her glass-walled living quarters in the research bunker. The similarity of these spaces visually reinforces the film’s late revelation that Caleb has been manipulated by Nathan Bates (Oscar Isaac), the troubled genius who creates Ava.

[ Ed.: In these paragraphs, the author cites the information about the scene she's provided to make her argument. Because she's already teased the argument in the introduction and provided an account of her evidence, it doesn't strike us as unreasonable or far-fetched here. Instead, it appears that we've naturally arrived at the same incisive, fascinating points that she has. ]

A few other shots in the opening sequence more explicitly hint that Caleb is already under Nathan’s control before he ever arrives at the bunker. Shortly after the P.O.V shot of Caleb reading the email notification that he won the prize, we cut to a few other P.O.V. shots, this time from the perspective of cameras in Caleb’s phone and desktop computer. These cameras are not just looking at Caleb, but appear to be scanning him, as the screen flashes in different color lenses and small points appear around Caleb’s mouth, eyes, and nostrils, tracking the smallest expressions that cross his face. These small details indicate that Caleb is more a part of this digital space than he realizes, and also foreshadow the later revelation that Nathan is actively using data collected by computers and webcams to manipulate Caleb and others. The shots from the cameras’ perspectives also make use of a subtle fisheye lens, suggesting both the wide scope of Nathan’s surveillance capacities and the slightly distorted worldview that motivates this unethical activity.

[ Ed.: This paragraph uses additional details to reinforce the piece's main argument. While this move may not be as essential as the one in the preceding paragraphs, it does help create the impression that the author is noticing deliberate patterns in the film's cinematography, rather than picking out isolated coincidences to make her points. ]

Taken together, the details of Ex Machina ’s stylized opening sequence lay the groundwork for the film’s long exploration of the relationship between human communication and technology. The sequence, and the film, ultimately suggests that we need to develop and use new technologies thoughtfully, or else the thing that makes us most human—our ability to connect through language—might be destroyed by our innovations. All of the aural and visual cues in the opening sequence establish a world in which humans are utterly reliant on technology and yet totally unaware of the nefarious uses to which a brilliant but unethical person could put it.

Author's Note: Thanks to my literature students whose in-class contributions sharpened my thinking on this scene .

[ Ed.: The piece concludes by tying the main themes of the opening sequence to those of the entire film. In doing this, the conclusion makes an argument for the essay's own relevance: we need to pay attention to the essay's points so that we can achieve a rich understanding of the movie. The piece's final sentence makes a chilling final impression by alluding to the danger that might loom if we do not understand the movie. This is the only the place in the piece where the author explicitly references how badly we might be hurt by ignorance, and it's all the more powerful for this solitary quality. A pithy, charming note follows, acknowledging that the author's work was informed by others' input (as most good writing is). Beautifully done. ]

Ex Machina (Film)

By alex garland, ex machina (film) summary and analysis of part 1.

The film opens in the offices of a large tech company. An employee, Caleb , gets a notification on his computer that he has won the first prize in an employee lottery. He texts his friends to tell them, and everyone in his office applauds for him.

The scene shifts and we see Caleb being flown in a helicopter over an icy terrain. He asks the pilot how long before they get to their destination, a man's estate. The pilot laughs and tells him they have been flying over the estate for the last 2 hours. The helicopter eventually lands in a large field, and the pilot tells Caleb that he has to leave him there, as it's the closest he's allowed to get to the building, before telling him to follow the river.

Caleb follows the pilot's instructions and makes his way to the building, noting that he has no cellphone service. When he arrives at the front entrance of the estate, an automated voice instructs him to come towards the main console and face the screen, which takes a picture of him. It then gives him a keycard, which opens the door. He wanders in tentatively and hears a piano playing somewhere. He calls out, but no one answers, before wandering out to a deck where the owner of the estate and CEO of Caleb's company, Nathan , is doing some boxing for exercise. He greets Caleb and tells him he is excited for their week together.

Nathan tells him he wanted to have breakfast with Caleb, but has a horrible hangover, so cannot. Caleb asks if it was a good party, and it becomes clear that Nathan was just drinking alone. Nathan says that he thinks Caleb is freaked out by the whole situation, but that he wants it to be more natural and less hierarchical, to just be "two guys."

Nathan tells Caleb that his key pass opens certain doors and not others. He invites Caleb to open a door, which opens for him into the bedroom that he will be staying in. Before Caleb can say anything, Nathan tells him that the reason the room does not have any windows is because the building is not a house, but a research facility. Before he can tell him more about the research project, Caleb must sign a non-disclosure agreement. In the agreement, Caleb realizes that he is signing an agreement to a regular "data audit with unlimited access," and is reluctant. He tells Nathan he needs a lawyer, but Nathan insists that it is standard.

Nathan tells Caleb that he can decide not to sign it, but that he will be missing out on learning about something extraordinary, something which is due to go public in about a year. Hearing this, Caleb signs. Nathan asks him if he knows what the Turing Test is. The Turing Test is an interaction between a human and a computer in which the human does not know they are interacting with a computer. "What does a pass tell us?" Nathan asks, to which Caleb replies, "That the computer has artificial intelligence."

Caleb realizes what is happening and Nathan tells him he is going to be the human component in a Turing Test with an AI that he has already constructed. "If that test is passed, you are dead center of the greatest scientific event in the history of man," Nathan tells him. Caleb responds, "If you've created a conscious machine, that's not the history of man. That's the history of gods."

A supertitle reads, " Ava : Session 1." Caleb examines a glass wall in the facility with some kind of crack in it, perhaps a bullet hole. Looking through the glass he sees the AI, Ava, who walks over and greets him. They introduce themselves and Ava tells him she's never met anyone besides Nathan. Caleb says they need to break the ice, and asks Ava to tell him something about herself. She tells him she's one year old, and that she always knew how to speak, even though language is something that people acquire.

In a meeting later, Caleb tells Nathan how fascinating it was to talk to Ava. Nathan is impressed with how quotable Caleb is, when he calls talking to Ava like going "through the looking glass." He also misrepresents Caleb's earlier comment, suggesting that Caleb called Nathan a God for creating a machine with consciousness. "I didn't say that," Caleb says, as Nathan grabs another beer. Caleb suggests that if they were actually doing the Turing Test, the machine would be hidden from view, but Nathan insists that the real test is to show that Ava is a robot and see if even then the human believes she has consciousness.

Caleb wants to know how Ava works, but Nathan insists that he cannot explain it because he would rather just spend time together. He asks Caleb how he feels about Ava, and Caleb says he thinks Ava is "fucking amazing."

That night, Caleb cannot sleep and turns on the television, which tunes to a surveillance video of the facility. He can see what Ava is doing in her room and watches her for a moment, before there is an abrupt power cut in the facility. A red light comes on in his room and he looks around, confused. A voice on the intercom states that the facility is in a full lock-down and Caleb cannot get out of his room. The power comes back on.

The premise of the film is established rather quickly, as we see a young employee at a tech company, Caleb, win a competition and get sent away to the company's CEO's estate within the first five minutes of the film. Little information is given about Caleb or his life in the world before we see him completely disoriented and displaced to an isolated and enigmatic location. His excitement at having been chosen to win his office's competition is quickly replaced with mystification and confusion once he finds himself at the estate, abandoned by the very pilot who brought him there, and left to wander towards his intimidating new lodgings alone.

By starting the film with the protagonist's displacement and alienation, director Alex Garland sets up a plot that resembles a kind of hero's journey. Since we do not know anything about Caleb, he becomes a kind of everyman, a stand-in for the viewers themselves. Caleb is just as "in-the-dark" as we are, an Alice in Wonderland in a curious hall of mirrors. This puts the simplicity of the plot into stark focus. Before we know much of anything, we know that Ex Machina will tell the story of an average man thrown into extraordinary circumstances.

The owner of the mysterious complex that Caleb visits is Nathan, a reclusive, forcibly casual, and rather awkward tech entrepreneur, who insists he just wants Caleb to feel comfortable, while all the while putting him in uncomfortable situations. He informs Caleb that he has a hangover from a night of drinking alone, then abruptly accuses Caleb of being too formal with him, even though he has done nothing to make Caleb feel welcome. He then informs Caleb that his home is not a home at all, but a research facility. The exact nature of this research is kept mysterious until Caleb has signed a non-disclosure agreement, one which binds Caleb to agree to having his data audited regularly for the rest of his life. The random and coercive ways in which all this information is disseminated clearly disorients and overwhelms the soft-spoken and kind-hearted Caleb.

Caleb does not regret signing the non-disclosure agreement when he learns that he is to be participating in a Turing Test with an AI that Nathan has constructed at his research facility. He is excited to be a part of the research, seeing the development of AI as an undeniably positive stride in technology. All of his trepidation about the arrangement of staying at Nathan's house is replaced by anticipation and excitement as he goes to meetings with Ava. Caleb comes alive at the prospect of helping to improve artificial intelligence technology.

There is an ominous atmosphere hanging over the story, even as Caleb becomes more at ease in his new environment. This is partially due to the disorientating realism of Ava—the mystery surrounding her consciousness and the impressive technology. It is also partially due to Nathan's egotism and hubris in response to his invention. He is consistently obtuse and self-involved, doing as little as humanly possible to make Caleb feel at ease, and even twisting Caleb's words into language that can be used to market his AI creation and inflate his own image. He believes that Caleb sees him as a "God" for his invention, and this reveals Nathan's overwhelming self-importance. His awkward grandiosity lends the proceedings an uneasy feeling; for someone who is so self-impressed and dealing with such unknown territory, there will surely be negative consequences.

Ex Machina (Film) Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for Ex Machina (Film) is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

Study Guide for Ex Machina (Film)

Ex Machina (Film) study guide contains a biography of director Alex Garland, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About Ex Machina (Film)

- Ex Machina (Film) Summary

- Character List

- Director's Influence

Essays for Ex Machina (Film)

Ex Machina (Film) essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of Ex Machina (Film), directed by Alex Garland.

- Biblical Allusions in Ex Machina

- The Pursuit of Knowledge in Ex Machina

Wikipedia Entries for Ex Machina (Film)

- Introduction

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Artificial Intelligence: Gods, egos and Ex Machina

Even with its flaws, last year’s Ex Machina perfectly captured the curious relationship between artificial intelligence, God and ego. A tiny change in its closing moments would have given it an intriguing new dimension.

It’s taken me a year and a several viewings to collect my thoughts about Ex Machina . Superficially it looks like a film about the future of artificial intelligence, but like most science fiction, it tells us more about the present than the future; and like most discussion around AI, it ends up reflecting not technological progress so much as human egos. (Spoilers ahead!)

Artificial intelligence is one of the most narcissistic fields of research since astronomers gave up the geocentric universe. A central conceit of the field has long been that creating human-like intelligence is both desirable and some sort of ultimate achievement. In the last fifty years or so, a chain of thinkers from von Neumann to Kurzweil via Vernor Vinge have stretched beyond that, to develop the idea of the ‘ Singularity ’ – a point at which the present human-led era ends as the first super-human AIs take charge of their own development and begin to hyper-evolve in ways we can scarcely imagine.

This recent cultural obsession – which deserves its own post - prompts a comment by the awestruck Caleb, after Nathan the Mad Scientist reveals his attempt to build a conscious machine and the two helpfully explain to the audience what a Turing Test is: “If you’ve created a conscious machine it’s not the history of man… that’s the history of Gods.”

There’s a funny symmetry in our attitudes to God and AIs.

When our species created God, we created Him in our image. We assumed that something as complicated as the world must be run by a human-like entity, albeit a super-powered one. We believed that He must be preoccupied with our daily lives and existence. We prayed to Him and told ourselves that our prayers would be answered, and that if they weren’t then it was part of some divine plan for our lives, and all would work out in the end.

For all that it preaches humility, religion holds a core of extreme arrogance in its analysis of the world. The exact same arrogance colours virtually everything I’ve seen written about the Singularity, fictional or otherwise, for decades. The very assumption that a human could create a god is arrogant, as is the assumption that such a ‘god’ would take a profound interest in human affairs, or be motivated by Western enlightenment values like technological progress. The first sentient machine might be happy trolling chess computers all day, for all we know; or seeking patterns in clouds.

“One day the AIs are going to look back on us the same way we look at fossil skeletons on the plains of Africa,” says Nathan. “An upright ape living in dust with crude language and tools, all set for extinction.” It’s the sort of comment that sounds humble, but really isn’t: why would they even give a crap?

“I don’t know how you did any of this,” Caleb remarks to the genius Nathan, when he first looks at the lab where Ava was built. Neither do I, to be honest, and in fact I’ll go further: I don’t believe Nathan did it at all. I have an alternative theory, and while I’m not sure if it’s what Alex Garland (writer and director of the film) intended, it makes a lot more sense than the alternative.

Nathan is the clearest study of ego in the film. When Caleb makes his comment about the history of ‘gods’, the CEO instinctively assumes the ‘god’ referred to is himself, where Ava is his Eve and his sprawling green estate is some sort of Garden of Eden.

Nathan is the epitome of a particular trope in society’s view of science and technology; the idea that tremendous advances are driven by determined individual heroes rather than collaborative teams. In reality of course there’s no way that one guy could deal with all the technology in that house, let alone find time to build gel-brains or a sentient machine. This is a man in serious need of some interns.