- The Open University

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

The debate on the origins of the First World War

This page was published over 5 years ago. Please be aware that due to the passage of time, the information provided on this page may be out of date or otherwise inaccurate, and any views or opinions expressed may no longer be relevant. Some technical elements such as audio-visual and interactive media may no longer work. For more detail, see how we deal with older content .

Find out more about The Open University's History courses and qualifications

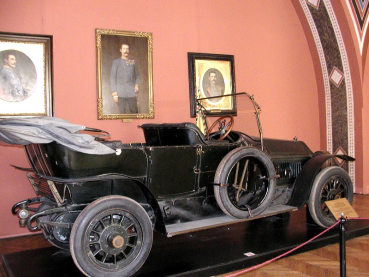

How could the death of one man, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, who was assassinated on 28 June 1914, lead to the deaths of millions in a war of unprecedented scale and ferocity? This is the question at the heart of the debate on the origins of the First World War. Finding the answer to this question has exercised historians for 100 years.

In July 1914, everyone in Europe was convinced they were fighting a defensive war. Governments had worked hard to ensure that they did not appear to be the aggressor in July and August 1914. This was crucial because the vast armies of soldiers that would be needed could not be summoned for a war of aggression.

Socialists, of whom there were many millions by 1914, would not have supported a belligerent foreign policy and could only be relied upon to fight in a defensive war. French and Belgians, Russians, Serbs and Britons were convinced they were indeed involved in a defensive struggle for just aims. Austrians and Hungarians were fighting to avenge the death of Franz Ferdinand.

Germans were convinced that Germany’s neighbours had ‘forced the sword’ into its hands, and they were certain that they had not started the war. But if not they (who had after all invaded Belgium and France in the first few weeks of fighting), then who had caused this war?

The war guilt ruling

For the victors, this was an easy question to answer, and they agreed at the peace conference at Versailles in 1919 that Germany and its allies had been responsible for causing the Great War.

Based on this decision, vast reparation demands were made. This so-called ‘war guilt ruling’ set the tone for the long debate on the causes of the war that followed.

From 1919 onwards, governments and historians engaged with this question as revisionists (who wanted to revise the verdict of Versailles) clashed with anti-revisionists who agreed with the victors’ assessment.

Sponsored by post-war governments and with access to vast amounts of documents, revisionist historians set about proving that the victors at Versailles had been wrong.

Countless publications and documents were made available to prove Germany’s innocence and the responsibility of others.

Arguments were advanced which highlighted Russia’s and France’s responsibility for the outbreak of the war, for example, or which stressed that Britain could have played a more active role in preventing the escalation of the July Crisis.

In the interwar years, such views influenced a new interpretation that no longer highlighted German war guilt, but instead identified a failure in the alliance system before 1914. The war had not been deliberately unleashed, but Europe had somehow ‘slithered into the boiling cauldron of war’, as David Lloyd George famously put it. With such a conciliatory accident theory, Germany was off the hook. A comfortable consensus emerged and lasted all through the Second World War and beyond, by which time the First World War had been overshadowed by an even deadlier conflict.

The Fischer Thesis

The first major challenge to this interpretation was advanced in Germany in the 1960s, where the historian Fritz Fischer published a startling new thesis which threatened to overthrow the existing consensus. Germany, he argued, did have the main share of responsibility for the outbreak of the war. Moreover, its leaders had deliberately unleashed the war in pursuit of aggressive foreign policy aims which were startlingly similar to those pursued by Hitler in 1939.

Backed up by previously unknown primary evidence, this new interpretation exploded the comfortable post-war view of shared responsibility. It made Germany responsible for unleashing not only the Second World War (of this there was no doubt), but also the First - turning Germany’s recent history into one of aggression and conquest.

Many leading German historians and politicians reacted with outrage to Fischer’s claims. They attempted to discredit him and his followers in a public debate of unprecedented ferocity. Some of those arguing about the causes of the war had fought in it, in the conviction they were fighting a defensive war. Little wonder they objected to the suggestion that Germany had deliberately started that conflict.

In time, however, many of Fischer’s ideas became accepted as a new consensus was achieved. Most historians remained unconvinced that war had been decided upon in Germany as early as 1912 (this was one of Fischer’s controversial claims) and then deliberately provoked in 1914.

Many did concede, however, that Germany seemed to have made use of the July Crisis to unleash a war. In the wake of the Fischer controversy, historians also focused more closely on the role of Austria-Hungary in the events that led to war, and concluded that in Vienna, at least as much as in Berlin, the crisis precipitated by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand was seen as a golden opportunity to try and defeat a ring of enemies that seemed to threaten the central powers.

Recent revisions

In recent years this post-Fischer consensus has in turn been revised. Historians have returned to the arguments of the interwar years, focusing for example on Russia’s and France’s role in the outbreak of war, or asking if Britain’s government really did all it could to try and avert the war in 1914. Germany’s and Austria-Hungary’s roles are again deemphasised.

After 100 years of debate, every conceivable interpretation seems to have been advanced, dismissed and then revisited. In some of the most recent publications, even seeking to attribute responsibility, as had so confidently been done at Versailles, is now eschewed.

Is it really the historian’s role to blame the actors of the past, or merely to understand how the war could have occurred? Such doubts did not trouble those who sought to attribute war guilt in 1919 and during much of this long debate, but this question will need to be asked as the controversy continues past the centenary.

After 100 years of arguing about the war’s causes, this long debate is set to continue.

Next: listen to the viewpoints of two leading historians on the causes of the war with our podcast Expert opinion: A debate on the causes of the First World War

This page is part of our collection about the origins of the First World War .

Discover more about the First World War

The origins of the First World War

Take an in-depth look at how Europe ended up fighting a four-year war (1914-1918) on a global scale with this collection on the First World War.

The Somme: The German perspective

How do Germans view the Battle of The Somme? This article explores reactions to the most famous battle of the First World War.

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand

How did a conspiracy to kill Archduke Franz Ferdinand set off a chain of events ending in the First World War? Explore what sparked the July Crisis.

Study a free course

The First World War: trauma and memory

In this free course, The First World War: trauma and memory, you will study the subject of physical and mental trauma, its treatments and its representation. You will focus not only on the trauma experienced by combatants but also the effects of the First World War on civilian populations.

Become an OU student

Ratings & comments, share this free course, copyright information, publication details.

- Originally published: Thursday, 19 December 2013

- Body text - Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 : The Open University

- Image 'The First World War: trauma and memory' - Copyright: © wragg (via iStockPhoto.com)

- Image 'The Somme: The German perspective' - Copyright: BBC

- Image 'The assassination of Franz Ferdinand' - By Alexf (Own work) [ CC-BY-SA-3.0 or GFDL ], via Wikimedia Commons under Creative-Commons license

- Image 'The origins of the First World War' - Copyright free: By Underwood & Underwood. (US War Dept.) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Rate and Review

Rate this article, review this article.

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

For further information, take a look at our frequently asked questions which may give you the support you need.

- Advanced Search

Version 1.0

Last updated 30 november 2016, the historiography of the origins of the first world war.

The debate about the origins of the war remains a vibrant area of historical research. It has been characterised by a number of features. First, from the outset, political concerns shaped the debate, though these preoccupations have become less significant as the war recedes into the past. Second, the debate is international, though with distinct national emphases. This international character owes much to political concerns, but it also reflects how historians work. Third, the debate has contributed to and been shaped by historiographical developments. This article presents these arguments in a narrative of the debate since 1914.

Table of Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Debate during the War

- 3 Between Politics and History: The Interwar Years

- 4 The Impact of the Second World War

- 5 The Fischer Debate

- 6 New Directions and Fragmentation

- 7 The Outbreak of War Revisited after 100 Years

Selected Bibliography

Introduction ↑.

The First World War has come to mark one of the great ruptures in modern history, the handmaiden of, to name but a small number of examples, new forms of literary irony , violence against civilians, and anti-colonial movements . Historians have devoted considerable attention to the origins of this rupture, veering between arguments stressing the long-term characteristics of international politics that led to war and the contingencies of decision-making in the final weeks of peace in 1914. This debate has now lasted over a century, with each consensus proving fragile and short-lived. The multiplicity of actors, the vast range of sources, and competing methodological approaches to international politics ensure the constant renewal of the subject. From the outset, political interests and contemporary affairs have shaped scholarly perspectives. There has been an intensive exchange of research, arguments, and polemics across national borders. The debate about the origins of the war has reflected, but also informed, changing historiographical fashions.

The Debate during the War ↑

Even before the outbreak of the war, leaders understood the political importance of casting responsibility for the war on their future enemies. Mobilising domestic support for a major war required that the conflict be justified as a defensive reaction to foreign aggression. Although sovereign states retained the right to wage war when they wished, in practice there was a narrow band of justifications for war, ruling out the most egregious kinds of aggression. Countenancing the possibility of war, leaders cast their moves as defensive. In Vienna, Oskar von Montlong (1874-1932) , the head of the Press Bureau at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, told the editor of the Reichspost : “We have no plans for conquest, we only want to punish the criminals, and to protect the peace of Europe in the future against such crimes.” Serbian leaders responded, using similar language about criminality and the peace of Europe, to deflect the Austro-Hungarian charge that Serbia harboured a criminal conspiracy. [1] In the final days of the crisis, mobilisation plans subordinated the military advantages of a sudden strike to the political imperatives of justifying a defensive war. The Russian mobilisation on 30 July allowed German leaders to rally different strands of popular opinion, particularly the socialist and trade union movement, to a war of defence against Tsarist autocracy. Raymond Poincaré (1860-1934) , the French president, insisted on keeping troops ten kilometres behind the border so that an inadvertent incident could not sully the government’s claim to its own population and to its British partner, that Germany was the aggressor.

The debate about responsibility was infused with moral claims from the outset, as each side attributed to their enemies the responsibility for violating norms of international politics by waging aggressive war. Foreign ministries issued hastily assembled collections of diplomatic documents, an early example of the assertion that “truth” lay in the archives. [2] Citizens, particularly academics and intellectuals, wrote in defence of their state’s conduct. Without access to the diplomatic documents, scholars interpreted the origins of the war in the context of allegedly long-standing cultural and social differences. Debates about the conduct of war, particularly the early reports of atrocities , and war aims became intertwined with arguments about the responsibility for war. The purpose was to provide from each belligerent’s perspective a seamless account of the war. For example, the claims of Henri Bergson (1859-1941) , the French philosopher, that the war represented a struggle between “civilisation” and “barbarism” accommodated the German violations of Belgian neutrality , the atrocities committed by German troops in Belgium and northern France , and French claims that it was fighting war in defence of right and justice, as well as its own territory. Werner Sombart (1863-1941) explained that all wars resulted from opposing beliefs. The pursuit of power and profit were only the superficial causes of a war that sprang from the conflict between the “merchant”, represented primarily by Britain , and the “hero”, represented by Germany. [3]

Sombart’s work was a response to Allied claims, like those made by Bergson, that the war pitted the “civilised” against the “barbaric”. The Appeal of the 93 , a declaration by leading German intellectuals, began its list of theses by stating, “It is not true that Germany is guilty of causing this war.” The authors dismissed Allied claims that Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) was a modern “Attila”, by emphasising his efforts throughout his reign to preserve peace. [4] Throughout the war, there was an intensive transbelligerent debate. Information flowed relatively easily across the lines. Writers could get hold of pamphlets written by enemy citizens. Speeches of enemy leaders were reprinted in newspapers – if only to serve as a foil for immediate rebuttal of the claims to moral superiority and political moderation. Debates between the belligerents about the origins of the war also took place in neutral spaces, particularly in the United States until its entry into the war in 1917. Delegations of academics toured neutral states. On occasion, the press in neutral states published important material. In 1918, the Swedish paper Politiken published documents written by the former German ambassador to London, Prince Max von Lichnowsky (1860-1928) and designed for a small circle amongst the German elite. Lichnowsky rejected claims that he had failed to understand Sir Edward Grey’s (1862-1933) foreign policy and his testimony underlined the readiness of German leaders to risk British entry into the war. Allied authors happily seized upon these documents to buttress their arguments that German leaders had pursued a reckless course during the July crisis .

Although the to-and-fro between belligerent politicians and scholars about responsibility dominated debate, other academic and political communities contributed novel perspectives. Edmund Dene Morel (1873-1924) and the Union of Democratic Control argued that secret diplomacy was the fundamental cause of the war – and in making this argument they staked their claims for future parliamentary control of foreign policy. In retrospect, the most important contributions to these debates came from Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924) , Bolsheviks, and other socialist opponents of the war. In September 1915, socialist opponents of the war from around Europe gathered at the Swiss town of Zimmerwald . The manifesto, written by a group, including Leon Trotsky (1879-1940) , dismissed the debate about the “immediate responsibility” for the outbreak of the war, maintaining that “one thing is clear: the war, which produced this chaos, is the product of imperialism , of the striving of the capitalist class of each nation to feed their desire for profits through the exploitation of human labour and the natural treasures of the globe.” [5]

Lenin’s writings on the war echoed this interpretation of its origins. He drew on pre-war criticisms of imperialism and the corrupting relationship between capitalism and the state by the British author, J.A. Hobson (1858-1940) , amongst others. Viewing the war as a clash of capitalist imperialist states had obvious political attractions for socialist revolutionaries. It challenged the arguments of socialist supporters of the war that it was waged in defence of the nation. By linking the origins of the war to the suffering of millions, it legitimised Bolshevik demands for dramatic social and political reform. After the Bolsheviks came to power in 1917, they never sought to defend the record of Tsarist foreign policy and published volumes of incriminating primary sources.

In Germany, the Social Democrats , who had supported the war, and the Independent Social Democrats, who had rejected further war credits from 1917 onwards, formed a provisional coalition government after the Kaiser ’s abdication. Although they represented themselves as a clean break from Germany’s imperial regime, the centrality of assigning responsibility for the outbreak of the war in any peace settlement meant they were constrained from a more open account of the origins of the war. The independent socialist Karl Kautsky (1853-1938) , jailed for his opposition to the war, briefly worked on Foreign Office documents about the July crisis, before the provisional government thought better of its folly and appointed two other figures to help, or more accurately to tone down, Kautsky – the pacifist Walter Schücking (1875-1935) and the diplomat Maximilian Montgelas (1860-1938) .

The question of “war guilt” intensified the political stakes in the historical debate. Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles stated:

The article was inserted by the American delegation, with John Foster Dulles (1888-1959) , the future secretary of state, playing a central role in its drafting. The American concept sought to place claims for reparations on a legal basis, rather than the right of victory. Article 231 therefore underpinned key features of the treaty and the wider political design of the post-war order, including reparations and international law . This made the article an obvious target for German attacks. On receiving the draft text of the treaty, the German foreign minister Ulrich von Brockdorff-Rantzau (1869-1928) denounced article 231 (and some others) as the “war guilt clause” and “shame paragraphs”. He changed the meaning of the article from one of legal and political responsibility to one of moral and national honour. He completed the process of fusing moral and political categories, evident in the earliest debates about the origins of the war. This fusion and the high political stakes made historical research into the origins of the war fraught in the 1920s.

Between Politics and History: The Interwar Years ↑

The German Foreign Office established a specialist section ( Referat ) to attack the “war guilt” clause, as part of its efforts to revise the Treaty of Versailles. Historical research in the former belligerent societies served political agendas. Historians were often willing participants in this highly politicised debate about the origins of the war. They gained prestige and funding from their association with major national causes. The German Foreign Office funded journals and lecture tours, particularly in the United States. As importantly, historians often shared the broad views of their respective foreign ministries. And even those who were sceptical of emerging national narratives about the origins of the war still relied heavily upon sources published under the aegis of the foreign ministries.

Publishing massive collections of documents became a central feature of interwar research and debate. In the 1920s, the German Foreign Office published over forty volumes of documents in the series Die Grosse Politik der europäischen Kabinette . A three-man team edited the collection. The series started in the 1870s following the Franco-Prussian War and the volumes became denser as they entered the 20 th century. A concern to downplay German acts of aggression influenced the selection and editing of documents. Some of Wilhelm II’s revealing marginal comments on diplomatic traffic were omitted, while other documents were falsified.

Other states followed suit. Political concerns were at the fore. Pierre de Margerie (1861-1942) , the French ambassador to Berlin, warned Prime Minister Aristide Briand (1862-1932) in 1926 – in the era of Franco-German rapprochement – that France would lose the contest for world opinion unless it followed suit. As in Die Grosse Politik the selection of documents reflected political imperatives. Harold Temperley (1879-1939) , a British historian who worked on the British Documents on the Origins of the War , noted that, “We cannot, of course, tell the whole truth.” [6] The Soviet publication of diplomatic documents was designed to damage the reputations of all the great powers. The lead editor was M.N. Pokrovsky (1868-1932) , one of Russia ’s first Marxist historians. He joined the Bolshevik party after the 1917 revolution and played an influential role in developing education policy. The documents were translated into German – but not into English or French – under the guidance of Otto Hoetzsch (1876-1946) , a leading German expert on Russian politics. Financed by a German loan, four Austrian historians edited eight volumes of Austro-Hungarian diplomatic documents.

The volume of documents in these collections overwhelmed other sources produced in the interwar period. Archives and personal collections of papers were generally inaccessible – or else made public through the publication of memoirs. These publications therefore had considerable weight in shaping the debate over the origins of the war. First, the choice of German and French historians and officials to start the series in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian war pushed the search for the origins back from the immediate context of the July crisis and the years immediately preceding the war. This gave rise to a narrative that emphasised the flaws of the international order, rendering war a likely outcome of decades of great power rivalries. Second, the study of the origins of the war became the study of diplomatic history. Without access to significant materials from other ministries or personal papers, historians generally worked on the assumption that the key decisions were made in the foreign ministries. This downplayed the role of military and economic groups in making foreign policy. Sources for public opinion were available – in 1931 Malcolm Carroll (1893-1959) published his important study of French public opinion and foreign policy – but these were under-utilised. Third, the publication of so many volumes ensured that historians often had access to several accounts of the one event or discussion. The comparison and weighing of different diplomatic sources meshed with the traditional strengths of critical analysis by historians and with the emphasis the profession placed on documents as the repository of historical “truth”.

By the late 1920s, historians were busily digesting the mass of documents. American historians – most prominently Bernadotte Schmitt (1886-1969) , Sidney Fay (1876-1967) , William Langer (1886-1959) , and Harry Elmer Barnes (1889-1968) – were at the fore of the debate. For the first time since the outbreak of the war, historians began to achieve some critical distance from the subject, even if they were working with documentary materials shaped by the political struggles over article 231. Reviewing books by Pierre Renouvin (1893-1974) , a veteran and leading French diplomatic historian, and by Eugen Fischer (1881-1964) , an historian working for the Reichstag’s War Guilt Section, Schmitt suggested that the “debate can be conducted with ample knowledge and good temper”. [7] Renouvin warned against “establishing a dogma”. It was, he declared, “the historian’s task not to fix responsibilities, but rather to furnish explanations and to make clear the circumstances which guided the development of international politics.” [8] Renouvin’s own contribution, La crise européene et la grande guerre , published as part of the series on European history, Peuples et civilisations , held German and Austro-Hungarian leaders primarily responsible for the outbreak of war. Their willingness to risk war and German leaders’ belief in the inevitability of war – rather than the Russian decision to mobilise on 30 July – were decisive in bringing about war. This confirmed his findings in an earlier volume on the July crisis. Renouvin’s style remained remarkably dispassionate, especially given the loss of his left arm, as a result of injuries suffered in April 1917. [9]

The most comprehensive analysis of the origins of the war, written by the former editor of Corriere della Sera , Luigi Albertini (1871-1941) , was published during the Second World War. It represented the culmination of the diplomatic history approach of the interwar years. Supported by Luciano Magrini (1885-1957) , the former foreign correspondent of Corriere della Sera , Albertini’s study dissected minutely individual decisions, which he saw as “the chain of recklessness and error, which brought Europe to catastrophe.” Albertini attributed the “final, definite responsibility” to the German military planners, whose mobilisation plans ensured war, while also castigating the political miscalculations of leaders in Vienna and Berlin, who hoped for localised war but were prepared to risk a general European war. But he did not shy away from criticisms of other leaders – Sergei Sazonov’s (1860-1927) misunderstanding of mobilisation plans or Grey’s failure to warn Germany more clearly about Britain’s likely entry into a European conflict, for example. [10]

Even if historians distanced themselves from politics, the wider political context inevitably shaped questions and perspectives. Some British historians, such as William Dawson (1860-1948) , funded by the German Foreign Office’s War Guilt Section, revised their wartime argument that Prussian militarism was the root cause of the war, and now emphasised the anarchical character of the pre-war order. The shift away from the “German war guilt” thesis was intertwined with international political developments, notably the reintegration of Germany into the international community and appeasement in the late 1920s and 1930s. [11]

The Impact of the Second World War ↑

On 28 May 1940, Philip Noel-Baker (1889-1982) , Labour MP, Olympic medallist, and later Nobel Peace Prize winner, told the House of Commons that

Noel-Baker, a conscientious objector during the First World War, was one of many to make the association between the Nazi regime and Prussian militarism. On 25 February 1947, the Allied Control Council abolished the state of Prussia, “which from the early days has been a bearer of militarism and reaction in Germany”. The aggressive, expansionist foreign and military policies of the Third Reich compelled contemporaries to think anew about the relationship between German domestic politics and the origins of major European wars from the 1860s to the 1940s.

The relationship between academic and political debate is illustrated by two contributions to the debate. The first example is A.J.P. Taylor’s (1906-1990) survey, The Course of German History , completed in September 1944 and published the following year. Taylor, a member of the Labour Party, had written a chapter on the Weimar Republic, part of a “compilation”, as he put it, “to explain to the conquerors what sort of country they were conquering”. The chapter was rejected for its allegedly pessimistic reading of German history, so Taylor responded by writing a full survey. His aim was to locate Adolf Hitler’s (1889-1945) regime within the course of German history. The First World War and its origins became a central part of this narrative. In typically irreverent and suggestive style, Taylor argued that the origins of the war were primarily rooted in the crisis-prone politics of the German Empire after 1906. Foreign policy setbacks – the formation of the Triple Entente between 1904 and 1907 and an over-reliance on the Austro-Hungarian ally – and the increasing fragility of Bismarckian constitutional settlement of 1871 increased the willingness of German leaders to pursue highly risky policies. He disputed that any single person “ruled at Berlin”, but he contended that the elites saw war as a solution to the growing domestic problems. Success in war served domestic agendas, buttressing authoritarian elites against democratic reforms. [13] His masterpiece, The Struggle for Mastery in Europe, 1848-1918 , took a different approach, analysing the international system and paying little attention to domestic pressures, but he concluded that the incompetence of Wilhelm II and Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (1856-1921) and the aggressive ambitions of German generals caused the war.

Of course, the advent of the Second World War could lead to conclusions radically different from Taylor’s. After 1945 German historians faced the task of giving an historical context for the Third Reich, while also renewing German historiographical traditions. The German historian and veteran of the First World War Gerhard Ritter (1888-1967) published Machtstaat und Utopie in 1940, a partially disguised attempt to separate the Nazi regime from its self-proclaimed roots in German history. “How infinitely important a task is it for the historian,” Ritter wrote to Friedrich Meinecke (1862-1954) in September 1946, “to assure the continuity of our historical thought and this to prevent a chaos of political and moral desperation, which could result from the catastrophic and abrupt end of our traditions, and still to possess the necessary flexibility in order to be able to sustain a real new beginning.” [14] Imprisoned between November 1944 and the end of the war, Ritter completed his four-volume history of German militarism in the 1950s and 1960s, but it derived from debates amongst historians between 1933 and 1945 about the place of the Third Reich in German history.

Ritter sought an answer to the question of how the German people, “for centuries the most peaceful in Europe”, had found a leader in Adolf Hitler, “a violent adventurer” and the “destroyer of the old order of Europe”. For Ritter, Hitler represented a perversion of politics, the subordination of politics to war. The roots of the Hitler regime, Ritter suggested, lay in the triumph of military over political considerations, which brought about the destruction of the political order and moral conventions. This process began, according to Ritter, in the late 19 th century, as “military patterns of thinking came to invade the ideology of the middle class”. The Schlieffen Plan, which privileged technical military considerations over what was politically possible, represented the triumph of the military over politics. Ritter criticised Bethmann Hollweg and others for their unquestioning acceptance of the primacy of military necessity over political judgement. While this contributed to the outbreak of war in 1914, he argued that neither German political nor military leaders sought war and dismissed the value of the question of “war guilt”. As the volumes were published after the war, he also saw them as a contribution to the debate about strategy in an age of nuclear war. [15]

Ritter’s broader strategy was to locate the Third Reich within the broad sweep of the growth of modern mass politics in Europe after 1789, while also divorcing the movement from conservative German traditions. While Wilhelm II and Bethmann Hollweg were not fully excused from their follies: they were cast as moderates, overwhelmed by modern militarism before and during the war. Bismarck and the Prussian conservative state were rescued from the opprobrium heaped upon them by the Allies and critical foreign historians, such as Taylor. Within the West German historical profession in the 1950s, the origins of the war lay in the anarchical international system and modern militarism. As continental rivals moved towards cooperation and integration in the early 1950s, a Franco-German Historians’ Commission, including Renouvin and Ritter, recommended that textbooks adopt the interwar interpretation of the origins of the war. [16]

The Fischer Debate ↑

It was in this context that the Fischer controversy broke. Certainly the most passionate debate since the early 1920s, the Fischer controversy was perhaps also the most nationally bounded debate on the origins of the war. Fritz Fischer’s (1908-1999) thesis about German plans to initiate a war and then to pursue expansionist war aims hardly came as a surprise to historians outside the Federal Republic. Before examining the political context and consequences, Fischer’s thesis requires a brief summary. From the time of the infamous War Council meeting in December 1912, he argued, German leaders planned a war of aggression. The drive to war resulted from increasing anxiety amongst German elites about the deterioration of the domestic and international stability of the Empire. Crucially, Fischer argued, German leaders had brought this situation upon themselves. At home, they stalled on constitutional changes, while German isolation in international politics was the result of menacing moves over Morocco and the Balkans after the turn of the century. It was a case of self-encirclement. He showed how military and political leaders prepared for war from late 1912, increasing the size of the army and fostering aggressive nationalist public opinion. This interpretation significantly reduced the interpretive weight placed on the international system. His interpretation derived from a methodological move, from the primacy of foreign policy to the primacy of domestic politics. On this reading, foreign policy was primarily the product of domestic political pressures. Given the importance of the primacy of foreign policy in German historiography, Fischer’s thesis represented an assault on cherished approaches as well as comforting explanations of the origins of the war.

In later works, he elaborated his arguments about the German elites’ failure to introduce constitutional reform and the temptations of an aggressive foreign policy. This was the fundamental driving force of the history of the German nation-state between 1871 and 1945. The implications of this argument were already evident in his books on German war aims and pre-war foreign policy. This account challenged the efforts of Ritter and others to separate the Nazi regime from the continuities of German history. As the title of one of Fischer’s books put, “ Hitler war kein Betriebsunfall ” (“Hitler was no accident”). [17]

Conservative historians, notably Ritter and Egmont Zechlin (1896-1992) , criticised Fischer’s use of sources, his methodological assumptions, and the political consequences of this revisionist account of the origins of the war. They argued that many of the documents could be interpreted in alternative ways. Indeed, complex disputes over the interpretation of the War Council meeting continue to the present day. Although historians on both sides of the debate claimed that documents provided access to historical “truth”, the complex context of each document made singular interpretations difficult. The author’s intentions were also open to interpretation. Wilhelm II’s marginalia could be read either as evidence of his plans for war or of his impulsive tendencies. Ritter criticised Fischer’s methodology. Although his own work had dissected the role of the German military in pre-war politics, he worked from the assumption that foreign policy was a response to international, not domestic political, conditions. The anxieties of German leaders before 1914 were the product of isolation and encirclement, cemented by the Anglo-Russian entente of 1907. Some German historians – and the American Paul Schroeder – argued that the entente powers, in particular Britain, were the most expansionist states in the decades before 1914. In global terms – then an unusual perspective for a scholar of European power politics – the expansion of the British and French Empires made Germany relatively weaker.

The controversy owed much of its febrile atmosphere to the political stakes. Recent research has shown that Fischer had already viewed the conservative German historical profession with suspicion, even contempt, during the 1930s. At this point, Fischer was certainly open to certain Nazi ideas and he was appointed professor of modern history at the University of Hamburg in 1942. The defeat in 1945 and his experience as a prisoner of war had a profound impact on Fischer’s attitude to the study of German history – if not to the dominant conservative, middle-class German historians. “Only now did I become aware of the fateful effects that the tradition of unconditional obedience … had on German history,” he later remarked. [18] Historical research and writing had a national pedagogical purpose; history would instruct the people on the development of the baleful authoritarian tradition in German political culture. Where Ritter and his allies sought to rescue a “useable past”, to use Charles Maier’s term, Fischer sought to press the past into service as a warning, as a call to political and social reform. In this respect, the two camps shared a similar, if negative, goal, namely avoiding a return to a dictatorship.

Conservative German historians, however, charged Fischer with undermining the Federal Republic’s place integration into the Western community of nations and domestic political stability. Not only did they challenge Fischer’s thesis in reviews and the press, but they also sought to hinder planned tours of the United States to promote his work.

By the 1970s, Fischer’s thesis had become the new orthodoxy. The weight of evidence and the clarity of his argument undoubtedly contributed to his success. Yet the success of any historical argument also owes much to wider political and social contexts. Within West German universities, a new generation of graduate students adopted a more critical perspective on German history. They tended to emphasise the long-term continuities that culminated in the Third Reich. Studies of the German Empire were a proxy for engagement with the history of the Nazi past. A new generation of German historians went much further than Fischer in emphasising the domestic roots of the origins of the war. Hans Ulrich Wehler (1931-2014) , based at Bielefeld, was the most prominent of these historians. He introduced new approaches from the social sciences, which saw domestic politics as a struggle between different economic and social groups. Social elites – business people, agrarians, the officer corps, and the mandarin class – forged alliances to retain power and wealth at the expense of workers, peasants, and other social groups. They thwarted constitutional reform. Yet these elite alliances were beset by contradictions. An expansionist imperialist policy offered the elites in the German Empire a means to escape these contradictions and to stifle domestic reform – but at the risk of war. Wehler’s survey of the German Empire traced the origins of the war back to the authoritarian features of Bismarck’s 1871 constitution. Whereas in the interwar period, historians saw in Franco-German antagonism the original flaw of the international system, Wehler and others now located the source of the problems in the German constitution.

Amongst French historians there was a similar change in emphasis, away from the diplomatic history practised by Renouvin in the interwar period towards a greater interest in the economic and social bases of foreign policy. This change, however, had its origins in the application of Fernand Braudel’s research in long-term historical processes to the study of the “forces profondes” of international politics. Between the late 1960s and mid-1970s, Renouvin himself and Jean-Baptiste Duroselle (1917-1994) supervised important works on French imperial expansion, economic relations, and public opinion. Yet their impact on the historiography of the origins of the war was less marked than that of Fischer’s students and the Bielefeld school. In part, the French studies did not deal directly with the political decisions of the July crisis and in part they confirmed existing interpretations that French policy had contributed towards creating the conditions for war, but had not actively sought war. [19]

A second source for Fischer’s success was the support he received in Britain and the United States. His arguments confirmed the general thrust of post-Second World War scholarship on the origins of the war. His engagement with American and British academics was important in inspiring his own criticisms of the methodological assumptions within the German historical profession. Invitations to lecture at universities and the translations of his books gave additional validation to his research. James Joll (1918-1994) , one of the most important post-war British historians of international relations, introduced Fischer’s work to a broad Anglophone audience in the influential journal Past & Present and wrote the preface to the English translation of Der Griff nach der Weltmacht . [20] Joll argued that Fischer’s focus on the domestic political impulses behind foreign policy would lead historians to revisit the foreign policies of other great powers. And they did, broadening the source-base and asking new questions. The works of Zara Steiner on Britain, John Keiger on France, and Dominic Lieven on Russia, published by Macmillan in the series Making of the Twentieth Century offered outstanding interpretations of other nations’ foreign policies before 1914. But one consequence of Fischer’s thesis was that it reinforced the argument that German foreign policy had been the most aggressive and destabilising in Europe before 1914 and that the other powers had reacted defensively to the German challenge. By the late 1970s a new orthodoxy about the origins of the war was established, emphasising the primary responsibility of German leaders for ending peace in Europe and the flawed domestic political development of the German nation-state after 1871.

New Directions and Fragmentation ↑

Although the Fischer thesis remained a source of debate amongst German historians, the erosion of the orthodoxy that had emerged in the 1960s and 1970s had diverse sources, often outside Germany. For example, two British historians, Geoff Eley and David Blackbourn, began to dismantle the Sonderweg thesis. British social historians were not inclined to idealise British historical developments, against which German history could be measured and found wanting. In the immediate term, the questioning of the Sonderweg by social historians had little impact on research in international history. Rather than a full-fronted assault on the Fischer thesis, the cornerstone of the new orthodoxy, changing historical interpretations, emerged across a range of different issues. This reflected the increasing breadth of research into international history, but it also contributed to a fragmentation of the field.

Political developments continued to shape historians’ perspectives. Of course not every changing perspective can be attributed to contemporary political currents. Rarely do historians adopt an openly “presentist” frame of reference for their research. Present debates tend to work in more suggestive ways, opening up new questions rather than providing easy templates. George Kennan’s (1904-2005) well-known characterisation of the First World War as the “seminal catastrophe” of the 20 th century came during the height of the Second Cold War during the 1980s, when fear of nuclear war stalked the world. Political scientists investigated the “cult of the offensive” before 1914, with one eye on the influence of military planners on foreign policy. [21]

Yet the end of the Cold War arguably had a more profound impact, raising new questions. First, the relatively peaceful ending of the Cold War suggested that long-term great power confrontation did not inevitably issue in a general war. Indeed political scientists, such as John Mueller, wrote of the “obsolescence of major war”, which they traced back to the experiences of the First World War. Historians began to ask not why war broke out in 1914, but why and how peace between the great powers had been maintained for over four decades. Holger Afflerbach questioned the argument of his doctoral supervisor, Wolfgang Mommsen (1930-2004) , that political and military leaders viewed war as inevitable. Instead, he and Friedrich Kießling identified a topos of “improbable war”. Questions have their own built-in assumptions. By reframing the question around the preservation of peace, historians have directed their attention to stabilising elements in international politics. This has informed revisionist accounts of a wide range of topics, from the alliance system to popular movements.

Second, the failure of many realist scholars to predict the outcome of the Cold War led international relations theorists to revisit assumptions about international politics. From the early 1990s, scholars developed constructivist approaches to international politics, challenging realist ideas about anarchy, the distribution of power, and the articulation of the national interest. As Alexander Wendt put it neatly, “anarchy is what states make of it”. Tracing the impact of this new departure in international relations scholarship on historical research is difficult for various reasons. Historians have long been aware of the importance of perception and what James Joll called the “unspoken assumptions”. Whereas Joll was primarily interested in how these assumptions shaped individual decisions, notably during the July crisis, the constructivist approach invites historians to consider how understandings of the international system are shared between key actors. It directs attention to the normative environment, adding a further layer to analyses based on power and interest. Although we may see norms as being pro-social – facilitating cooperation and conflict-resolution – certain norms, such as honour, can incentivise violence and war. Explaining the outbreak of war can also involve charting how the normative environment broke down in the final years of peace. [22]

The end of the Cold War accelerated processes of globalisation, which had begun in the 1970s. By the 1990s, historians were busily drafting agendas for global history. The late 19 th and early 20 th centuries offered a rich seam for global historians. On many measures, the world was “more global” in 1913 than in the early 21 st century. Capital flows, trade, migration, and cultural exchange reshaped the world after the American Civil War. Jürgen Osterhammel and Niels Petersson called this the era of “classical globalisation.” [23] Yet globalisation in the early 20 th century produced a puzzle of sorts for historians of international relations. The credo of globalisation theories in the 1990s suggested that growing economic interdependence and cultural exchange made wars – certainly between the major powers – irrational in any sense of material gain or security. Similar arguments had been well rehearsed before 1914 and yet the great powers had gone to war. Kevin O’Rourke and Richard Findlay contend that the First World War brought 19 th century globalisation to an “abrupt end”, but they also suggest that the war was not the result of inherent tensions in the global economy. Rather, the war “still appears as somewhat of a diabolus ex machina ” in their account. [24] Interdependence could produce conflict as well as harmony. Some recent works have begun to tease out the relationship between globalisation and erosion of peace. Sebastian Conrad’s work on German identity and globalisation before 1914 showed how national identity was sometimes strengthened through antagonistic encounters with others in a globalising international system. Nicholas Lambert argues that British naval planners intended to exploit commercial interdependence to bring about Germany’s economic collapse, while Jennifer Siegel has shown how the financial interdependence between Russia and France strengthened the political alliance between the two states. [25]

Since the 1980s historians of British foreign policy have questioned narratives centred on the European balance of power and the German threat to British security. Keith Wilson argued that British decision-makers viewed Russia as the primary threat, privileged the maintenance of empire over the balance of power in Europe, and had a military posture dedicated to imperial defence, not European wars. [26] The historical debate reflected in some ways the broader debate in Britain about its relationship with Europe. Scepticism about British participation in the European project had existed since the end of the Second World War, but during the 1980s this scepticism migrated from the Labour to the Conservative party. Eurosceptics on the right continued to emphasise themes such as the defence of parliamentary sovereignty, but they also sought to present Britain as a global, rather than a European, power. In the late 1990s, Niall Ferguson and John Charmley published two of the most trenchant criticisms of British foreign policy before 1914. Both argued that Britain should have stayed out of the war and that a Europe under German hegemony – the Kaiser’s European Union in Ferguson’s telling phrase – would have been compatible with British interests. According to Charmley, Grey had an unfounded fear of the German Empire, while Ferguson followed Wilson’s argument that Grey appeased Russia to stave off a threat in central Asia – but at the cost of encircling Germany in Europe and creating conditions that made war more likely. [27] Since the 1990s, this argument has rumbled on and has encountered some strong rebuttals. Nonetheless, it has had implications for the broader discussion of the origins of the war, emphasising the relationship between the emerging global balance of power and the anxieties of German leaders who feared the Empire was being relegated to a second-rate European power.

One consequence of Germany’s dominant position amongst the Central Powers was the relative neglect of Austro-Hungarian foreign policy in discussions of the question of the origins of the war. This neglect was compounded by the assumption that the multi-ethnic empire was inevitably doomed to collapse, its foreign policy largely a study in myopia and wishful thinking. Recent historiography has been generous in assessing the stabilising function of the Austro-Hungarian Empire . The ponderous decision-making process and the labyrinthine bureaucracy look less odd as Europeans grapple with the complexities of the European Union. Paradoxically the more positive view of the Austro-Hungarian Empire has gone hand in hand with more sustained criticism of its foreign policy-makers, who overestimated the challenges posed by national minorities. Samuel Williamson – in the Macmillan series mentioned above – argued that leaders in Vienna were responsible for pushing for war in 1914. In other words, German support was essential for the Austro-Hungarian attack on Serbia, but Leopold von Berchtold (1863-1942) , Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf (1852-1925) , and other key figures in Vienna had their own agendas and were not mere pawns in German machinations. [28]

The renewed attention to Austria-Hungary’s foreign policy – at least in English-language surveys of international politics before the war – reflects a shift in historians’ geographical perspectives. Narratives centred on Anglo-German antagonism or the hereditary enmity of the French and Germans were rooted in the wartime experience, but the focus on western European tensions marginalised the fault lines, conflicts, and accommodations in eastern Europe and the Balkans. The violent break-up of Yugoslavia , the expansion of the European Union, tensions between Russia and its neighbours, and the growth of Turkish power in the eastern Mediterranean has reshaped how historians view European history. As historians have integrated research beyond the Western Front into their analyses of the war, international historians now pay more attention to the agency of the Balkan states, the vicissitudes of Ottoman politics, and Russian ambitions in the region – supplementing the work of previous generations of historians, who had examined British, German, and French imperial projects. Sean McMeekin’s work has done much to shift historians’ attention to the conflicts between Russia and the Ottoman Empire , though his claims about Russian responsibility for starting the war have been heavily criticised, notably in Dominic Lieven’s recent thoughtful account. [29] This work also raises broader questions about the normative environment and hierarchies of states in Europe. Mustafa Aksakal’s important study of Ottoman foreign policy on the eve of its entry to the war in November 1914 shows how intellectuals close to the Committee of Union and Progress lost faith in the claims of great powers to uphold international law, while Michael Reynolds examines how geopolitical rivalry and the principle of nationality were mutually constitutive in Russian-Ottoman relations. [30]

Fresh agendas and debates also resulted from new methodological approaches to international history and the opening up of further archival material. The fall of Communist regimes in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union led to the opening up of new archival material. This included the return of archival material about military planning to Germany, which spawned a minor cottage industry centred on the Schlieffen Plan. [31] The rise of cultural history in the 1980s, with its emphasis on language, mentalities, and representation, had much to offer international historians. Equally Joll’s work on unspoken assumptions and constructivist theories of international relations showed that international historians could contribute to the breadth of cultural history. And yet, for various reasons, the fields of international and cultural history remained distant. The fruitful collaboration between military and cultural historians has been followed by valuable cultural history approaches to international relations. These studies may not explain the moment of decision about war and peace – the diplomatic twitch, as David Reynolds puts it – but they deepen our understanding of the complexity of international relations, how power was constructed, and how people imagined the questions and choices they encountered in foreign policy. [32]

The breadth of scholarship produced since the 1970s had not only chipped away at the Fischer thesis; it had also enlarged historians’ understandings of foreign policy making before 1914. The clarity of Fischer’s thesis had less purchase against the background of the evident complexity of international politics. In historiographical terms, this complexity had resulted in the fragmentation of the study of international history. The emphasis on complexity also reflected an understanding of the openness of history, of the possibilities in international politics before 1914. Without a singular thesis to bind together the study of international history, historians engaged each other on more narrow grounds, such as German military planning or British naval policy before 1914.

The Outbreak of War Revisited after 100 Years ↑

The centenary predictably saw a wave of publications, many of which addressed the origins of the war. Two of these works – Christopher Clark’s Sleepwalkers and Thomas Otte’s July crisis – represent the most comprehensive analyses of the outbreak of the war since Albertini’s work. They both combine research across a mass of published primary and archival sources in several languages with a command of the sprawling secondary literature.

Weighing in at well over 500 pages each, the two books offer space for different interpretations of key moments and individuals. Otte is critical of the “recklessness” of statesmen in Vienna, Berlin, and, to a lesser extent, St Petersburg. Leopold von Berchtold, the Habsburg Foreign Minister, and his fellow diplomats at the Ballhausplatz , Otte argues, suffered from “tunnel-vision”, which reduced Austro-Hungarian foreign policy to Balkanpolitik . Otte frequently describes Berlin’s crisis diplomacy as “reckless”, while the Chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, appears as “marginal” in many key decisions. On the other hand, Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary, is a man of action, perspicacious, and committed to peace, even if the foundations of his diplomacy was flawed due to the recklessness and uncompromising stance of others. [33] Clark offers an alternative reading of the crisis. Despite having been charged with ignoring the question of responsibility and claiming to abjure the “finger-jabbing” prosecutorial stance, so common to many histories of the outbreak of the war, he does not shy away from trenchant judgements on key figures. The French president, Raymond Poincaré, discredited the Austro-Hungarian charges against Serbia and dissembled during the final days of peace. Grey, he argues, consistently prioritised the maintenance of the Triple Entente over the peaceful resolution of the crisis, which meant that his string of conference proposals in late July were half-baked, while he also failed to restrain Russian moves, even after its partial mobilisation on 25 July. Meanwhile the Russian decisions for partial and then full mobilisation fuelled the escalation of the crisis, while “the Germans had remained, in military terms, an island of relative calm throughout the crisis”. [34]

Although these differences of interpretation relate to some of the most fundamental debates about the July crisis and suggest a wide gulf between Clark and Otte, in many respects their overarching interpretations have a considerable amount in common. First they both emphasise the contingent character of the July crisis, how the accumulation of individual decisions led to outcomes often at odds with the intentions of the authors of those decisions. Both books, to use Clark’s phrase, are “saturated with agency.” Second, despite the stress on individual decisions, they tend to view the crisis in systemic terms. By emphasising “how” the European powers came to war in 1914, rather than “why”, Clark shifted the focus from the intentions of decision-makers to the impact their decisions had within a tightly ordered international system, eventually sundering the pre-war order. While Otte warns historians against judging decisions against some putative norms of a given international order – the Great Power order of the early 20 th century – his own careful analysis, showing how considerations of alliance, détente, and relative military power shaped assumptions and led to disastrous miscalculation, is an instructive model of how to place individual decisions within a systemic context. Third, both express doubts about the conceiving of the July crisis in terms of national “policies”. In Clark’s view, policy implies a coherence, which was impossible to achieve in the polycratic regimes and porous transnational connections of the era, while Otte repeatedly notes the divisions between military and civilian leaders, even within individual foreign ministries, that hampered the articulation of clear strategies. Again, this reflects Clark’s reframing of the question in terms of “how”, rather than “why”. The historian exploits their vantage point to show how the system operated and collapsed. Perhaps most fundamentally, both agree that no single belligerent or individual should shoulder the bulk of the responsibility for the outbreak of war. Their differences are ones of emphasis and detail.

Whether these books will provide unity to a fragmented field of research remains to be seen. They demonstrate how questions about individual issues in international politics can contribute to the broader debate about the origins of the war. The success of Clark’s book, particularly in Germany, has also aroused a public debate about the origins of the war. His work is often read against that of Fischer, the last high-profile public contribution to the debate in Germany. As ever, contemporary political events lurk in the background. Clark mentions, at various points, the terrorist attacks of 9/11, the Dayton Accord during the Yugoslav Wars, and the crisis in the Euro-zone. The first two are directly related to his argument about the impact of individual moments and contingency on historical processes – the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este (1863-1914) and the ultimatum issued to Serbia. The publication of the German translation coincided with the Euro-crisis, which in turn raised questions about Germany’s position in Europe. History remains inescapable in political debate. For some, Clark’s thesis of shared responsibility between the belligerents for the outbreak of war will give succour to those who want to cast aside Germany’s role in two world wars and adopt a more assertive reading of the national interest. For others, the burden of “war guilt” cripples Berlin’s leadership, damaging European institutions as well as German interests. As new challenges and questions arise in future international politics, it is likely that historians will continue to revisit the origins of the war with new questions and fresh arguments.

William Mulligan, University College Dublin

Section Editor: Annika Mombauer

- ↑ Hantsch, Hugo: Leopold Graf Berchtold, volume 2, Graz 1963, p. 564.

- ↑ This argument draws on Mombauer, Annika: The Fischer Controversy, Documents, and the Truth about the Origins of the First World War, in: Journal of Contemporary History 48/ 2 (2013), pp. 290-314.

- ↑ Sombart, Werner: Händler und Helden. Patriotische Besinnungen, Munich 1915, pp. 3-5.

- ↑ Ungern-Sternberg, Jürgen von: Wolfgang von Ungern-Sternberg, Der Aufruf “An die Kulturwelt”. Das Manifest der 93 und die Anfänge der Kriegspropaganda im Ersten Weltkrieg, Stuttgart 1996, pp. 141-145.

- ↑ Lademacher, Horst (ed.): Die Zimmerwalder Bewegung, The Hague 1967, p. 166.

- ↑ Cited in Wilson, Keith: Introduction: Governments, Historians, and Historical Engineering, in: Wilson, Keith (ed.): Forging the Collective Memory, Berg et al. 1996, p. 17.

- ↑ Schmitt, Bernadotte: The origins of the war, in: Journal of Modern History 1/1 (1929), p. 112.

- ↑ Renouvin, Pierre: How the war came, in: Foreign Affairs (April 1929), p. 384.

- ↑ Renouvin, Pierre: La crise européene et la grande guerre (1904-1918), Paris 1934, pp. 109-117, 181-183; Renouvin, Pierre: Les origines immédiates de la guerre, Paris 1925; on Renouvin, see Duroselle, Jean-Baptiste: Pierre Renouvin et la science politique, in: Revue française de science politique 25/3 (1975), pp. 561-574.

- ↑ Albertini, Luigi: The Origins of the War of 1914, 3 volumes, London 1953, volume 2, pp. 485 and 579.

- ↑ Pogge von Strandmann, Hartmut: Britische Historiker und der Ausbruch des Ersten Weltkrieges, in: Michalka, Wolfgang (ed.): Der Erste Weltkrieg. Wirkung, Wahrnehmung, in: Analyse, Munich 1994, pp. 929-952.

- ↑ “Civil Estimates”, 28 May 1940, vol 361, online: http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1940/may/28/civil-estimates-1940#S5CV0361P0_19400528_HOC_274 (retrieved 8 November 2016).

- ↑ Taylor, A.J.P.: The Course of German History. A Survey of the Development of German History since 1815, London 1962, pp. vii-xi, 176-193.

- ↑ Schwabe, Klaus: Change and Continuity in German Historiography from 1933 into the Early 1950s: Gerhard Ritter (1888–1967), in: Lehmann, Hartmut (ed.): Paths of Continuity: Central European Historiography from 1933 to the 1950s, Cambridge 1994, p. 104.

- ↑ Ritter, Gerhard: The Sword and the Scepter. The Problem of Militarism in Germany, 4 volumes, Coral Gables, Florida 1969, volume 1, pp. 11-13, volume 2, pp. 117, 194-195, 275.

- ↑ Mombauer, Annika: The Origins of the First World War. Controversies and Consensus, London 2002, p. 123.

- ↑ Fischer, Fritz: Hitler war kein Betriebsunfall, Munich 1991.

- ↑ Petzold, Stephan: The Social Making of a Historian: Fritz Fischer’s Distancing from Bourgeois-Conservative Historiography, 1930-1960, in: Journal of Contemporary History 48/2 (2013), p. 284.

- ↑ Renouvin, Pierre: Jean-Baptiste Duroselle, Introduction à l’histoire des relations internationales, Paris 1964; ibid., p. 569.

- ↑ Petzold, Social Making of a Historian 2013, p. 286; Joll, James: The 1914 debate continues: Fritz Fischer and his critics, in: Past & Present 34 (July 1966), pp. 100-113 and Joll’s preface to Fischer, Fritz: Germany’s war aims in the First World War, London 1967.

- ↑ Kennan, George: The decline of Bismarck’s European order. Franco-Russian relations, 1875-1890, Princeton 1981; Snyder, Jack: The ideology of the offensive. Military decision-making and the disasters of 1914, Ithaca 1989.

- ↑ Kießling, Friedrich: Gegen den Großen Krieg. Entspannung in den internationalen Beziehungen 1911-1914, Munich 2002; Reynolds, Michael: Shattering Empires. The Clash and Collapse of the Ottoman and Russian Empires, 1908-1918, Cambridge 2011; Clark, Christopher: Sleepwalkers. How Europe went to war in 1914, London 2012, pp. 240-241; one of the most impressive engagements by an historian with a wide range of international relations theory can be found in Jackson, Peter: Beyond the Balance of Power. France and the Politics of National Security in the Era of the First World War, Cambridge 2013.

- ↑ Osterhammel, Jürgen/Petersson, Niels P.: Globalization. A Short History, Princeton 2009, pp. 81-90.

- ↑ Findlay, Richard/O’Rourke, Kevin: Power and Plenty: Trade, War, and the World Economy in the Second Millennium, Princeton 2007, pp. xxiv–xxv.

- ↑ Conrad, Sebastian: Globalisierung und Nation in Deutschen Kaiserreich, Munich 2006; Lambert, Nicholas: Planning Armageddon. British Economic Warfare and the First World War, Cambridge, MA 2012; Siegel, Jennifer: For Peace and Money. French and British Finance in the Service of the Tsars and Commissars, Oxford 2015.

- ↑ Wilson, Keith: The Policy of the Entente. The Determinants of British Foreign Policy, 1904-1914, Cambridge 1985.

- ↑ Ferguson, Niall: The Pity of War, London 1998; Charmley, John: Splendid Isolation? Britain, the Balance of Power and the Origins of the First World War, London 1999.

- ↑ Watson, Alex: Ring of Steel. Germany and Austria-Hungary at War, 1914-1918, London 2014; Williamson, Samuel: Austria-Hungary and the Origins of the First World War, Basingstoke 1991; Kronenbitter, Günther: Krieg im Frieden. Die Führung der k. u. k. Armee und die Großmachtpolitik Österreich-Ungarns 1906-1914, Munich 2003.

- ↑ McMeekin, Sean: The Russian Origins of the First World War, Cambridge, MA 2011; Lieven, Dominic: Towards the Flame. Empire, War and the End of Tsarist Russia, London 2015.

- ↑ Aksakal, Mustafa: The Ottoman Road to War in 1914. The Ottoman Empire and the First World War, Cambridge 2008; Reynolds, Shattering Empires 2011.

- ↑ Zuber, Terence: Inventing the Schlieffen Plan. German War Planning, 1871-1914, Oxford 2002.

- ↑ Reynolds, David: International History, the Cultural Turn, and the Diplomatic Twitch, in: Cultural & Social History 3/1 (2006), pp. 75-91.

- ↑ Otte, Thomas G.: The July Crisis. The World’s Descent into War, 1914, Cambridge 2014, pp. 43, 169.

- ↑ Clark, Sleepwalkers 2012, pp. 445-449, 493-506, 510.

- Albertini, Luigi: The origins of the war of 1914 , London; New York 1952: Oxford University Press.

- Clark, Christopher M.: The sleepwalkers. How Europe went to war in 1914 , New York 2013: Harper.

- Fischer, Fritz: War of illusions. German policies from 1911 to 1914 , New York 1975: Norton.

- Joll, James: The 1914 debate continues. Fritz Fischer and his critics , in: Past & Present 34, 1966, pp. 100-113.

- Mombauer, Annika: The origins of the First World War. Controversies and consensus , Harlow; New York 2002: Longman.

- Mombauer, Annika: The Fischer controversy, documents and the 'truth' about the origins of the First World War , in: Journal of Contemporary History 48/2, 2013, pp. 290-314.

- Mombauer, Annika (ed.): Special issue. The Fischer controversy after 50 years , in: Journal of Contemporary History 48/2, 2013.

- Mulligan, William: The trial continues. New directions in the study of the origins of the First World War , in: The English Historical Review 129/538, 2014, pp. 639-666.

- Neilson, Keith: 1914. The German war? , in: European History Quarterly 44/3, 2014, pp. 395-418.

- Otte, Thomas: July Crisis. The world's descent into war, summer 1914 , New York 2014: Cambridge University Press.

- Petzold, Stephan: The social making of a historian. Fritz Fischer's distancing from bourgeois-conservative historiography, 1930-60 , in: Journal of Contemporary History 48/2, 2013, pp. 271-289.

- Ritter, Gerhard: The sword and the scepter. The problem of militarism in Germany , volume 2, Coral Gables 1970: University of Miami Press.

- Ritter, Gerhard: The sword and the scepter. The problem of militarism in Germany , volume 3, Coral Gables 1972: University of Miami Press.

- Ritter, Gerhard: The sword and the scepter. The problem of militarism in Germany , volume 4, Coral Gables 1973: University of Miami Press.

- Ritter, Gerhard: The sword and the scepter. The problem of militarism in Germany , volume 1, Coral Gables 1969: University of Miami Press.

- Schwengler, Walter: Völkerrecht, Versailler Vertrag und Auslieferungsfrage. Die Strafverfolgung wegen Kriegsverbrechen als Problem des Friedensschlusses 1919/20 , Stuttgart 1982: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt.

- Wilson, Keith M.: Forging the collective memory. Government and international historians through two World Wars , Providence 1996: Berghahn Books.

Mulligan, William: The Historiography of the Origins of the First World War , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2016-11-30. DOI : 10.15463/ie1418.11016 .

This text is licensed under: CC by-NC-ND 3.0 Germany - Attribution, Non-commercial, No Derivative Works.

Related Articles

External links.

- Search Menu

- Conflict, Security, and Defence

- East Asia and Pacific

- Energy and Environment

- Global Health and Development

- International History

- International Governance, Law, and Ethics

- International Relations Theory

- Middle East and North Africa

- Political Economy and Economics

- Russia and Eurasia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Special Issues

- Virtual Issues

- Reading Lists

- Archive Collections

- Book Reviews

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About International Affairs

- About Chatham House

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Goodbye to all that (again)? The Fischer thesis, the new revisionism and the meaning of the First World War

This is a revised text of the 39th Martin Wight Lecture, given at the University of Sussex on 6 November 2014.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

JOHN C. G. RÖHL, Goodbye to all that (again)? The Fischer thesis, the new revisionism and the meaning of the First World War, International Affairs , Volume 91, Issue 1, January 2015, Pages 153–166, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12191

- Permissions Icon Permissions

What is the truth about the nature of the First World War and why have historians been unable to agree on its origins? The interpretation that no one country was to blame prevailed until the 1960s when a bitter international controversy, sparked by the work of the Hamburg historian Fritz Fischer, arrived at the consensus that the Great War had been a ‘bid for world power’ by imperial Germany and therefore a conflict in which Britain had necessarily and justly engaged. But in this centennial year Fischer's conclusions have in turn been challenged by historians claiming that Europe's leaders all ‘sleepwalked’ into the catastrophe. This article, the text of the Martin Wight Memorial Lecture held at the University of Sussex in November 2014, explores the archival discoveries which underpinned the Fischer thesis of the 1960s and subsequent research, and asks with what justification such evidence is now being set aside by the new revisionism.

One hundred years ago, on 4 August 1914 to be exact, my motherland Great Britain declared war on my fatherland Germany. The German army had invaded neutral Belgium with the intention of crushing first France and then Russia and eliminating both as Great Powers ‘for all imaginable time’, as the German Chancellor von Bethmann Hollweg put it in his September Programme in 1914. Just 25 years later, on 3 September 1939, Britain declared war on Germany a second time when Hitler, hand in glove with Stalin, fell upon Poland, so in effect restoring Germany's 1914 common frontier with Russia in the east.

My Scottish grandfather served in the British Army in the First World War, surviving the sinking of his ship by a German U-boat off the Algerian coast to stand as a Labour candidate for parliament in three general elections in the 1920s. My father was in the Wehrmacht's counter-espionage service, the Abwehr, in Hungary and survived the advance of the Red Army to become the headmaster of a large grammar school in Frankfurt am Main in the American zone. And I did my National Service in the Royal Air Force and was stationed in occupied Germany before going up to Cambridge to read history at Corpus Christi College. Three generations, three survivors of the Anglo-German agony of the first half of the twentieth century. In 1964 I was appointed to the University of Sussex as lecturer in the School of European Studies, whose founding dean was none other than the Olympian figure of Martin Wight, whose distinguished contribution to the study of international relations we are commemorating in this series of lectures. It is perhaps fitting, therefore, that I should have the privilege of giving this talk in Martin Wight's honour on the centenary of the seminal catastrophe of the First World War, the 75th anniversary of the outbreak of war in 1939, and the 25th anniversary of the reunification of a democratic Germany within the framework of a peaceful Europe.

It does not take much imagination to see the First and Second World Wars as two acts in the same drama. The immediate cause of war in 1939 might have been different from that in 1914, but with the German attack on France in May 1940 followed by the invasion of Soviet Russia in June 1941 the similarities between the two conflicts became unmistakable. It was, as General de Gaulle remarked in 1940 in one of his first speeches from London, as if the Schlieffen Plan had been put into operation all over again. In both cases we see a German Reich bent on the conquest of Europe—and the determination of the other nations, led first by Britain, then by the peoples of the ‘bloodlands’ of Eastern Europe and finally by the United States, to resist such subjugation, however terrible the cost. These were no ordinary wars, but, as Winston Churchill observed at the beginning of what rapidly became known as the Great War, ‘a struggle between nations for life or death’. 1

Yet this interpretation has recently been challenged by a wave of revisionism, exemplified by the astronomical success—especially in Germany, where it has sold many hundreds of thousands of copies—of the book The Sleepwalkers by our colleague Christopher Clark. 2 He and the other revisionists largely exonerate the Kaiser's Germany from responsibility for the First World War. While claiming to argue that war broke out by accident, with no one government more at fault than any other, in practice Clark places the blame to a large extent on little Serbia, followed by Russia, France and Britain in that order, presenting Austria-Hungary as doing its genuine best to avoid war and simply omitting altogether the evidence of any German intention to bring the war about.