Deliberative Democracy : Essays on Reason and Politics

James Bohman is Danforth Professor of Philosophy at Saint Louis University. He is the author, editor, or translator of many books.

William Rehg is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Saint Louis University. He is the translator of Jürgen Habermas's Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy (1996) and the coeditor of Deliberative Democracy: Essays on Reason and Politics and Pluralism (1997) and The Pragmatic Turn: The Transformation of Critical Theory (2001), all published by the MIT Press.

Ideals of democratic participation and rational self-government have long informed modern political theory. As a recent elaboration of these ideals, the concept of deliberative democracy is based on the principle that legitimate democracy issues from the public deliberation of citizens. This remarkably fruitful concept has spawned investigations along a number of lines. Areas of inquiry include the nature and value of deliberation, the feasibility and desirability of consensus on contentious issues, the implications of institutional complexity and cultural diversity for democratic decision making, and the significance of voting and majority rule in deliberative arrangements.The anthology opens with four key essays—by Jon Elster, Jürgen Habermas, Joshua Cohen, and John Rawls—that helped establish the current inquiry into deliberative models of democracy. The nine essays that follow represent the latest efforts of leading democratic theorists to tackle various problems of deliberative democracy. All the contributions address tensions that arise between reason and politics in a democracy inspired by the ideal of achieving reasoned agreement among free and equal citizens. Although the authors approach the topic of deliberation from different perspectives, they all aim to provide a theoretical basis for a more robust democratic practice.

Contributors James Bohman, Thomas Christiano, Joshua Cohen, Jon Elster, David Estlund, Gerald F. Gaus, Jürgen Habermas, James Johnson, Jack Knight, Frank I. Michelman, John Rawls, Henry S. Richardson, Iris Marion Young

- Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

Deliberative Democracy : Essays on Reason and Politics Edited by: James Bohman, William Rehg https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.001.0001 ISBN (electronic): 9780262268936 Publisher: The MIT Press Published: 1997

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Table of Contents

- [ Front Matter ] Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0020 Open the PDF Link PDF for [ Front Matter ] in another window

- Acknowledgments Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0001 Open the PDF Link PDF for Acknowledgments in another window

- Introduction Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0002 Open the PDF Link PDF for Introduction in another window

- 1: The Market and the Forum: Three Varieties of Political Theory By Jon Elster Jon Elster Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0004 Open the PDF Link PDF for 1: The Market and the Forum: Three Varieties of Political Theory in another window

- 2: Popular Sovereignty as Procedure By Jürgen Habermas Jürgen Habermas Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0005 Open the PDF Link PDF for 2: Popular Sovereignty as Procedure in another window

- 3: Deliberation and Democratic Legitimacy By Joshua Cohen Joshua Cohen Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0006 Open the PDF Link PDF for 3: Deliberation and Democratic Legitimacy in another window

- 4: The Idea of Public Reason By John Rawls John Rawls Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0007 Open the PDF Link PDF for 4: The Idea of Public Reason in another window

- 5: How Can the People Ever Make the Laws? A Critique of Deliberative Democracy By Frank I. Michelman Frank I. Michelman Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0009 Open the PDF Link PDF for 5: How Can the People Ever Make the Laws? A Critique of Deliberative Democracy in another window

- 6: Beyond Fairness and Deliberation: The Epistemic Dimension of Democratic Authority By David Estlund David Estlund Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0010 Open the PDF Link PDF for 6: Beyond Fairness and Deliberation: The Epistemic Dimension of Democratic Authority in another window

- 7: Reason, Justification, and Consensus: Why Democracy Can’t Have It All By Gerald F. Gaus Gerald F. Gaus Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0011 Open the PDF Link PDF for 7: Reason, Justification, and Consensus: Why Democracy Can’t Have It All in another window

- 8: The Significance of Public Deliberation By Thomas Christiano Thomas Christiano Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0012 Open the PDF Link PDF for 8: The Significance of Public Deliberation in another window

- 9: What Sort of Equality Does Deliberative Democracy Require? By Jack Knight , Jack Knight Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar James Johnson James Johnson Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0013 Open the PDF Link PDF for 9: What Sort of Equality Does Deliberative Democracy Require? in another window

- 10: Deliberative Democracy and Effective Social Freedom: Capabilities, Resources, and Opportunities By James Bohman James Bohman Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0014 Open the PDF Link PDF for 10: Deliberative Democracy and Effective Social Freedom: Capabilities, Resources, and Opportunities in another window

- 11: Democratic Intentions By Henry S. Richardson Henry S. Richardson Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0015 Open the PDF Link PDF for 11: Democratic Intentions in another window

- 12: Difference as a Resource for Democratic Communication By Iris Marion Young Iris Marion Young Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0016 Open the PDF Link PDF for 12: Difference as a Resource for Democratic Communication in another window

- 13: Procedure and Substance in Deliberative Democracy By Joshua Cohen Joshua Cohen Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0017 Open the PDF Link PDF for 13: Procedure and Substance in Deliberative Democracy in another window

- Contributors Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0018 Open the PDF Link PDF for Contributors in another window

- Index Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0019 Open the PDF Link PDF for Index in another window

- Open Access

A product of The MIT Press

Mit press direct.

- About MIT Press Direct

Information

- Accessibility

- For Authors

- For Customers

- For Librarians

- Direct to Open

- Media Inquiries

- Rights and Permissions

- For Advertisers

- About the MIT Press

- The MIT Press Reader

- MIT Press Blog

- Seasonal Catalogs

- MIT Press Home

- Give to the MIT Press

- Direct Service Desk

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Statement

- Crossref Member

- COUNTER Member

- The MIT Press colophon is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Philosophical Perspectives on Democracy in the 21st Century

- © 2014

- Ann E. Cudd 0 ,

- Sally J. Scholz 1

Department of Philosophy, University of Kansas, Lawrence, USA

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

Department of Philosophy, Villanova University, Villanova, USA

- Considers reasons for the current political polarization in American politics, offering possible resolutions

- Orients the reader to contemporary issues in democratic theory and practice

- Deals with the effects of misinformation on social policy formation in democratic societies

- Debates the equally timely issue of economic inequality in democracy, considering principles and practical effects of capitalist property rights, taxation, and campaign finance law?

- Includes supplementary material: sn.pub/extras

Part of the book series: AMINTAPHIL: The Philosophical Foundations of Law and Justice (AMIN, volume 5)

24k Accesses

15 Citations

11 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

About this book

This work offers a timely philosophical analysis of fundamental principles of democracy and the meaning of democracy today. It explores the influence of big money and capitalism on democracy, the role of information and the media in democratic elections, and constitutional issues that challenge democracy in the wake of increased threats to privacy since 2001 and in light of the Citizens United decision of the US Supreme Court.

It juxtaposes alternate positions from experts in law and philosophy and examines the question of legitimacy, as well as questions about the access to information, the quality of information, the obligations to attain epistemic competence among the electorate, and the power of money.

Drawing together different political perspectives, as well as a variety of disciplines, this collection allows readers the opportunity to compare different and opposing moral and political solutions that both defend and transform democratic theory and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: Perspectives on Democracy

On the Concept and Practice of Democracy in Late-Modern Mass Conditions: An Oakeshottian Update

Introduction: Democracy in Times of Crises

- Conceptual Poverty as a Cause of Political Polarization

- Corporate Political Speech

- Democracy & Economic Inequality

- Democracy and the Information Problem

- Democracy as Social Myth

- Democracy in the 21st Century

Democracy, Capitalism, and the Influence of Big Money

- Democracy: A Paradox of Rights

- Democratic Decisions

- Distinctions in Democratic Equality

- Epistocracy

- Group Identification

- Is Justice under Welfare State Captitalism?

Journalists as Purveyors of Partial Truths

- Judicial Review and Its Compatibility with Democracy

- Mass Democracy in a Postfactual Market Society

- Meaning of Democracy

- Motivated Reasoning

- Pragmatic Democracy

- Precarious Democracy in the U.S.

- Representative Democracy

- Republics, Passions, & Protections

- Social Segregation, Complacency, & Democracy

- Spread of Democracy as a Manifestation of Progress

- Taxation in the American Republic

Two Visions of Democracy

Table of contents (17 chapters), front matter, philosophical perspectives on democracy in the twenty-first century: introduction.

- Ann E. Cudd, Sally J. Scholz

The Meaning of Democracy

Democracy: a paradox of rights.

- Emily R. Gill

Rights and the American Constitution: The Issue of Judicial Review and Its Compatibility with Democracy

Democracy as a social myth.

- Richard T. De George

The Current Polarization

Political polarization and the markets vs. government debate.

- Stephen Nathanson

- Richard Barron Parker

Proportional Representation, the Single Transferable Vote, and Electoral Pragmatism

- Richard Nunan

The Problem of Democracy in the Context of Polarization

- Imer B. Flores

Is Justice Possible Under Welfare State Capitalism?

- Steven P. Lee

Rawls on Inequality, Social Segregation and Democracy

Mass democracy in a postfactual market society: citizens united and the role of corporate political speech.

- F. Patrick Hubbard

A Tsunami of Filthy Lucre: How the Decisions of the SCOTUS Imperil American Democracy

- Jonathan Schonsheck

Democracy and Economic Inequality

- Alistair M. Macleod

Democratic Decisions and the (Un)Informed Public

Epistocracy within public reason.

- Jason Brennan

- Russell W. Waltz

From the book reviews:

Editors and Affiliations

Ann E. Cudd

Sally J. Scholz

Bibliographic Information

Book Title : Philosophical Perspectives on Democracy in the 21st Century

Editors : Ann E. Cudd, Sally J. Scholz

Series Title : AMINTAPHIL: The Philosophical Foundations of Law and Justice

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02312-0

Publisher : Springer Cham

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law , Philosophy and Religion (R0)

Copyright Information : Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014

Hardcover ISBN : 978-3-319-02311-3 Published: 18 December 2013

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-319-34518-5 Published: 27 August 2016

eBook ISBN : 978-3-319-02312-0 Published: 03 December 2013

Series ISSN : 1873-877X

Series E-ISSN : 2351-9851

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : VIII, 246

Number of Illustrations : 2 b/w illustrations

Topics : Political Philosophy , Theories of Law, Philosophy of Law, Legal History , Political Science , Social Policy , Philosophy of Law , Communication Studies

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Stanford University

Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law is housed in the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies

Philosophy, Politics, Democracy: Selected Essays

- Joshua Cohen

Over the past twenty years, Joshua Cohen has explored the most controversial issues facing the American public: campaign finance and political equality, privacy rights and robust public debate, hate speech and pornography, and the capacity of democracies to address important practical problems. In this highly anticipated volume, Cohen draws on his work in these diverse topics to develop an argument about what he calls, following John Rawls, "democracy's public reason." He rejects the conventional idea that democratic politics is simply a contest for power, and that philosophical argument is disconnected from life. Political philosophy, he insists, is part of politics, and its job is to contribute to the public reasoning about what we ought to do.

At the heart of Cohen's normative vision for our political life is an ideal of democracy in which citizens and their representatives deliberate about the requirements of justice and the common good. It is an idealistic picture, but also firmly grounded in the debates and struggles in which Cohen has been engaged over nearly three decades. Philosophy, Politics, Democracy explores these debates and considers their implications for the practice of democratic politics.

- Shopping Cart

Advanced Search

- Browse Our Shelves

- Best Sellers

- Digital Audiobooks

- Featured Titles

- New This Week

- Staff Recommended

- Reading Lists

- Upcoming Events

- Ticketed Events

- Science Book Talks

- Past Events

- Video Archive

- Online Gift Codes

- University Clothing

- Goods & Gifts from Harvard Book Store

- Hours & Directions

- Newsletter Archive

- Frequent Buyer Program

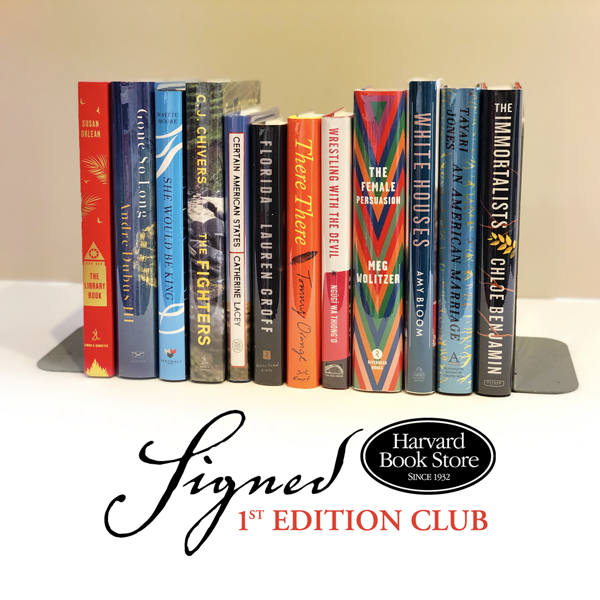

- Signed First Edition Club

- Signed New Voices in Fiction Club

- Off-Site Book Sales

- Corporate & Special Sales

- Print on Demand

- All Our Shelves

- Academic New Arrivals

- New Hardcover - Biography

- New Hardcover - Fiction

- New Hardcover - Nonfiction

- New Titles - Paperback

- African American Studies

- Anthologies

- Anthropology / Archaeology

- Architecture

- Asia & The Pacific

- Astronomy / Geology

- Boston / Cambridge / New England

- Business & Management

- Career Guides

- Child Care / Childbirth / Adoption

- Children's Board Books

- Children's Picture Books

- Children's Activity Books

- Children's Beginning Readers

- Children's Middle Grade

- Children's Gift Books

- Children's Nonfiction

- Children's/Teen Graphic Novels

- Teen Nonfiction

- Young Adult

- Classical Studies

- Cognitive Science / Linguistics

- College Guides

- Cultural & Critical Theory

- Education - Higher Ed

- Environment / Sustainablity

- European History

- Exam Preps / Outlines

- Games & Hobbies

- Gender Studies / Gay & Lesbian

- Gift / Seasonal Books

- Globalization

- Graphic Novels

- Hardcover Classics

- Health / Fitness / Med Ref

- Islamic Studies

- Large Print

- Latin America / Caribbean

- Law & Legal Issues

- Literary Crit & Biography

- Local Economy

- Mathematics

- Media Studies

- Middle East

- Myths / Tales / Legends

- Native American

- Paperback Favorites

- Performing Arts / Acting

- Personal Finance

- Personal Growth

- Photography

- Physics / Chemistry

- Poetry Criticism

- Ref / English Lang Dict & Thes

- Ref / Foreign Lang Dict / Phrase

- Reference - General

- Religion - Christianity

- Religion - Comparative

- Religion - Eastern

- Romance & Erotica

- Science Fiction

- Short Introductions

- Technology, Culture & Media

- Theology / Religious Studies

- Travel Atlases & Maps

- Travel Lit / Adventure

- Urban Studies

- Wines And Spirits

- Women's Studies

- World History

- Writing Style And Publishing

Philosophy, Politics, Democracy: Selected Essays

Over the past twenty years, Joshua Cohen has explored the most controversial issues facing the American public: campaign finance and political equality, privacy rights and robust public debate, hate speech and pornography, and the capacity of democracies to address important practical problems. In this highly anticipated volume, Cohen draws on his work in these diverse topics to develop an argument about what he calls, following John Rawls, “democracy’s public reason.” He rejects the conventional idea that democratic politics is simply a contest for power, and that philosophical argument is disconnected from life. Political philosophy, he insists, is part of politics, and its job is to contribute to the public reasoning about what we ought to do. At the heart of Cohen’s normative vision for our political life is an ideal of democracy in which citizens and their representatives deliberate about the requirements of justice and the common good. It is an idealistic picture, but also firmly grounded in the debates and struggles in which Cohen has been engaged over nearly three decades. Philosophy, Politics, Democracy explores these debates and considers their implications for the practice of democratic politics.

There are no customer reviews for this item yet.

Classic Totes

Tote bags and pouches in a variety of styles, sizes, and designs , plus mugs, bookmarks, and more!

Shipping & Pickup

We ship anywhere in the U.S. and orders of $75+ ship free via media mail!

Noteworthy Signed Books: Join the Club!

Join our Signed First Edition Club (or give a gift subscription) for a signed book of great literary merit, delivered to you monthly.

Harvard Square's Independent Bookstore

© 2024 Harvard Book Store All rights reserved

Contact Harvard Book Store 1256 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138

Tel (617) 661-1515 Toll Free (800) 542-READ Email [email protected]

View our current hours »

Join our bookselling team »

We plan to remain closed to the public for two weeks, through Saturday, March 28 While our doors are closed, we plan to staff our phones, email, and harvard.com web order services from 10am to 6pm daily.

Store Hours Monday - Saturday: 9am - 11pm Sunday: 10am - 10pm

Holiday Hours 12/24: 9am - 7pm 12/25: closed 12/31: 9am - 9pm 1/1: 12pm - 11pm All other hours as usual.

Map Find Harvard Book Store »

Online Customer Service Shipping » Online Returns » Privacy Policy »

Harvard University harvard.edu »

- Clubs & Services

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Home ›

- Reviews ›

Understanding Liberal Democracy: Essays in Political Philosophy

Nicholas Wolterstorff, Understanding Liberal Democracy: Essays in Political Philosophy , Terence Cuneo (ed.), Oxford University Press, 2012, 385pp., $65.00 (hbk), ISBN 9780199558957.

Reviewed by Kelly Sorensen, Ursinus College

Public reason liberalism -- the form of liberalism defended by Rawls, Larmore, Audi, Gaus, Rorty, Nussbaum, and to some degree Habermas -- usually requires citizens to publicly discuss and vote based on only those reasons that pass some sort of test that sifts away religious and comprehensive non-religious reasons. In the public sphere, those with such views are required by the role of citizenship to shape up or shut up -- "shape up" in the sense of offering instead reasons that can or could be shared by all other citizens. Nicholas Wolterstorff argues that public reason liberalism is a dead end, and defends instead what he takes to be a more defensible form of liberalism ("equal political voice liberalism"). His book is fresh and compelling, and an important contribution to political philosophy.

This is a collection of mostly new essays: nine appear for the first time. The remaining six are lightly edited for coherence with the new material. Ten concern public reason liberalism. The rest take up the nature of rights (extending the account that Wolterstorff has been developing in his recent books Justice: Rights and Wrongs and Justice in Love ), the nature and source of citizens' political obligations to the state, and other issues in political philosophy.

What motivates public reason liberalism's restrictions on the reasons citizens can express and vote on? One factor is fairness, a second pluralism, and a third a certain kind of realism about pluralism's persistence. Rawls says that we can expect "a pluralism of comprehensive doctrines, including both religious and nonreligious doctrines . . . as the natural outcome of the activities of human reason under enduring free institutions". This pluralism is "not seen as a disaster" (Political Liberalism (PL), xxiv), but it does raise concerns regarding a fourth factor, the stability of a liberal polity over time. Public reason liberalism sees religious comprehensive views in particular as "not admitting of compromise" and "expansionist" (Rawls), and even "conversation-stopping" and "dangerous" (Rorty). Because of these factors, public reason liberalism says, when it comes to publicly advocating for coercive legislation and voting, a citizen should restrict herself to reasons that she believes all capable adult fellow citizens do endorse or would endorse if they were (variously) better informed, more rational, drawing on a shared fund of premises that are freestanding and neutral with respect to controversial elements of comprehensive views, and so on.

Among Wolterstorff's arguments against public reason liberalism are the following. First, public reason liberalism actually is not realistic enough. One's capable adult fellow citizens clearly do not universally endorse the same reasons. So public reason liberalism has to idealize -- it has to imagine what reasons capable adult fellow citizens would endorse if they met certain hypothetical conditions, with the presumption that a consensus or convergence about these reasons would emerge. The hypothetical conditions vary from one brand of public reason liberalism to another. Suppose the conditions are full information and full rationality. Realistically, why think public reason liberalism is in a position to confidently say what reasons emerge from that idealization, and to say that there would be a consensus about them? Why think disagreement about these reasons will disappear under idealization? We can ask the same of Rawlsian idealization, which is laxer but still unrealistically strong: why think there would be consensus about what processes -- processes of rationally arriving at a set of judgments -- are themselves reasonable? So public reason liberalism is not realistic enough: we are stuck with pluralism, and we cannot idealize our way out of it.

Second, public reason liberalism is paternalistic and patronizing, despite its lip service to respect. Suppose Jones favors some policy on religious reasons that do not qualify as public reasons. Smith, a fan of public reason liberalism, is stuck with telling Jones, "You shouldn't express your reasons in public discussion, and you shouldn't vote on them. Here instead are the kinds of reasons that count -- reasons you would endorse if you were not under-informed and rationally impaired." Jones will of course find this condescending and patronizing. Even if Smith chooses more diplomatic words, public reason liberalism still entails a paternalistic and patronizing view of Jones. It's no surprise if Jones resents such an entailment about his reasons and whether he should express them and vote on them, and that resentment is a problem for the stability that Smith and public reason liberals ostensibly treasure.

A third argument from Wolterstorff is that public reason liberalism cannot consistently get what it wants anyway. Suppose Jones has a religious conviction that he should base his political views on his religious convictions. Jones listens to the arguments and objections of others with different views, but is unconvinced. He is like a Kantian listening to consequentialist arguments: he refuses to think that way. On the one hand, public reason liberals might seem to tell Jones to refrain from public discussion and voting. But on the other hand, that is "not what they should say, given their position as a whole" (100). Public reason liberalism gives citizens a prima facie duty to restrict themselves to public reasons, but in Jones's case that duty is outweighed by what he takes to be an " ultima facie " duty to appeal to his religious reasons. Public reason liberals will have to accept that Jones should reject their "public reason imperative." So public reason liberalism seems to leave Jones free to publicly debate and to vote based on his religious convictions after all -- the very result that most public reason liberals were attempting to avoid! So it is not possible for public reason liberals, on their own terms, to declare religious reasons inappropriate for public political discourse. There is a tension internal to the theory here.

A related fourth argument concludes that public reason liberalism asks too much of some religious believers. It entails that a piece of coercive legislation's legitimacy depends on Jones having, or counterfactually having, reasons in favor of the legislation that are good and decisive for Jones, the coerced subject. For at least some public reason liberals, it is not enough that Jones knows of public reasons that support the same legislation as his religious reasons; rather, the public reasons must be those on the basis of which Jones actually speaks and votes (36, 80, and 282). But this asks too much, Wolterstorff says. It asks Jones to let non-religious reasons trump his religious reasons when he speaks publicly and goes to the polls.

Fifth, public reason liberalism may caricature religious believers, insofar as it implies that believers are unwilling to go beyond the claim that "God told me that it's wrong so it's wrong." Interestingly, Wolterstorff turns here to qualitative empirical data. In the public discussion in Oregon in the 1990s about a physician-assisted suicide initiative, a leading account reports no such appeals by religious believers. Instead, public discussion in Oregon was characterized by a plurality of more substantive and contentful religious reasons, and also importantly, a plurality of secular reasons (not the supposed universal counterfactual shared premises that public reason liberalism inevitably resorts to).

Sixth, public reason liberalism may also caricature other varieties of liberal democratic engagement. Suppose we turn for a moment from policy deliberation and decision, the favored turf of public reason liberalism, to real-world grassroots organizing. In Maywood, California, city council members instituted an unusually onerous penalty for car drivers without a license: $1200 and a 30-day impound for the car. Towing companies were large donors to the city councilors' campaign funds. The law hit undocumented workers especially hard. Community members and community organizers attempted to use reasons -- public reasons -- to persuade the city council to change the law. That failed. Public reason liberalism seems stuck with the view that people in Maywood at that point should have backed off and shut up. Instead, acting under a plurality of reasons and emotions, including moral outrage, they ran a media campaign to call attention to the city council's corruption, and they registered more voters, until finally the city council members were voted out of office. Public reason liberalism is ill-equipped to theorize about real, non-well-ordered societies like, usually, our own.

These are only brief samples of Wolterstorff's arguments. He offers more sophisticated and detailed versions of these and other arguments when he engages with the specifics of individual theories of Rawls, Rorty, Gaus, Audi, Habermas, and others.

Wolterstorff calls his alternative form of liberal democracy "equal political voice liberalism," and he thinks it better accounts for the "governing idea" found in the longer historical tradition of liberalism, before public reason liberalism seized the spotlight in recent decades. There are two key aspects of equal political voice liberalism. First, citizens speak and vote within a constitutional context -- a context of classic civil liberties, such as freedom of speech, freedom of religious exercise, and freedom of association. Certain fundamental changes in law are appropriately "off the table" in this context of constitutional limits. Second, citizens are to speak and vote with an equal political voice. Intimidation and bullying are out; but otherwise, Wolterstorff's view puts no restrictions on the kinds of reasons to which citizens can appeal in public discussion and voting. That's it: we talk, using whatever reasons we want, religious and non-religious, comprehensive or otherwise, and then we vote. Anyone who wants to persuade others will, as a practical matter, find herself quoting reasons that will appeal to her opponents; but there is no requirement that she restrict herself to some special set of reasons. After the vote, there will be winners and losers. The losers will experience the winners' legislation as coercive. But to have expected otherwise is utopian. And Wolterstorff claims to have uncovered a variety of ways that public reason liberalism leans toward the utopian, despite its putative acceptance of pluralism, realism, and worries about stability.

As to the six issues above, Wolterstorff claims that equal political voice liberalism comes off better. First, it makes no unrealistic claim that, counterfactually, citizens' views on legislation would match some imagined consensus or convergence. Second, it is more respectful and less patronizing to citizens, because it does not tell them that their own reasons are epistemically inadequate. Third, it lets citizens speak and act on their own reasons without internal tension in the theory; and fourth, it does not demand that alien reasons be substituted and decisive. Fifth, the view does not caricature the reasons that people with comprehensive views tend to offer. Sixth, it is not myopic about varieties of democratic engagement -- there is policy deliberation and decision, but there is also broad-based organizing, movement organizing, and protest. Equal political voice liberalism better accounts for what happened in Oregon and in Maywood.

Wolterstorff's equal political voice liberalism does issue some "shape up" talk of its own. While designed to make broader room for religious reasons in the public square, it is not compatible with every religious perspective. Wolterstorff's liberalism does ask thinkers like Egyptian scholar Sayyid Qutb to endorse the constitutional context of liberal democracy and its commitment to not favoring any particular religious tradition. For Wolterstorff, "to affirm the liberal democratic polity is to put the shape of our life together at the mercy of votes in which the infidel has an equal voice with the believer" (295).

A mood of non-utopianism hangs over the book, but Wolterstorff is neither resigned nor pessimistic. Unlike dour critics such as MacIntyre, he loves liberal democracy. He agrees with public reason liberals that pluralism is ineradicable, but claims that there is more respect, more stability, and more positive endorsement of the system, when citizens speak and vote with an equal voice in a context of fundamental constitutional limits.

Equal political voice liberalism seems straightforward and simple, and it certainly has many attractions. Wolterstorff not only puts public reason liberals on the hot seat, but also sketches an alternative that captures important planks of the liberal democratic tradition. But consider a few concerns.

First, equal political voice liberalism seems to assume that after discussing and voting and grassroots organizing, there will be winners and losers, but that often enough the winners will be losers on other matters and the losers will in turn be winners (294). I take it this claim is supposed to address familiar concerns about stability. But it would be utopian to think that this happens often enough. It is easy to imagine places where the losers are very often repeat losers, because a majority persists there that sees little need to engage minority interlocutors. Depending on the place, the repeat losers could either be secular minorities or religious minorities. Wolterstorff will claim otherwise, but the best form of public reason liberalism might have more resources to address this worry than equal political voice liberalism.

Second, the book does not make clear whether Wolterstorff would consider an issue like state-authorized gay marriage to be part of the constitutional context, properly understood, and so part of the basic civil liberties that are "off the table" for democratic alteration by vote, or instead to be up for public discussion and a vote. From his discussion of the Oregon physician-assisted suicide case, we might think Wolterstorff would go for the latter, but personal correspondence indicates that he believes the former. In any case, even more specificity about what is off the table and what is on would be good.

Third, maybe things are not so bleak for public reason liberals, if they up their game and amend certain claims. Consider what we might call aspirational public reason liberalism. This theory is "aspirational" in three distinct ways. First, aspirational public reason liberalism asks citizens to aspire to offer reasons that are more general and broadly held than their own particular comprehensive-view-based reasons. But unlike the forms of liberalism that Wolterstorff's first argument addresses, it does not rely on the idea of a universal consensus or convergence about public reasons. Second, aspirational public reason liberalism does not require or demand that citizens restrict themselves to these more general public reasons, but it does ask them to aspire to offer them. Citizens do nothing forbidden or wrongful if they articulate religious or other comprehensive view reasons, but they fulfill the role of citizen well if they also offer more general reasons -- reasons that speak to a broader swath of fellow citizens. A third aspiration concerns the place of these more general reasons among the citizen's individual motives: aspirational public reason liberalism says that these more general reasons need not be decisive for the citizen when she speaks and votes. We might also add a Rawlsian scope restriction: these aspirations apply to "most cases of constitutional essentials and matters of basic justice" (PL, xxi), not necessarily to all matters of public discussion.

I believe this form of public reason liberalism survives most of Wolterstorff's objections. It leaves room for many of his key points, including realism about the nature of lived citizenship and public activism, and also openness to religious comprehensive views as historically a fecund source of generalizable moral insight. It preserves many of the attractions of public reason liberalism as well, including an ideal of the role of citizen and the role's coercive power that encourages robust respect for other members of the polity. Consider Rawls's claim that "Public reason sees the office of citizen with its duty of civility as analogous to that of judgeship with its duty of deciding cases" (PL, liii). The citizen who fulfills her office well will aspire to articulate reasons that go beyond her personal reasons -- a good citizen will do this not, as Wolterstorff's equal political voice liberalism says, on a mere practical and rhetorical basis; and a good citizen will do this even when she is part of a repeat-winner majority, when on Wolterstorff's view there is no practical reason for her to do so. [1] The judge/citizen analogy may not be as tight as Rawls seems to think: the role of judge comes with heavy demands of neutrality, while citizens face less onerous aspirations. In any case, it's worth noting, as Wolterstorff does, that in the 1995 introduction to the paperback edition of PL, Rawls does begin to soften. He says there that he now believes that reasons based on comprehensive doctrines "may be introduced in public reason at any time, provided that in due course public reasons, given by a reasonable political conception, are presented sufficient to support whatever the comprehensive doctrines are introduced to support" (PL, xlix). This isn't yet aspirational public reason liberalism, but it begins to point in that direction.

Whether or not public reason liberalism can be patched up in this or other ways, Wolterstorff's essays certainly reveal important undigested entailments in the standard view. This really is an excellent book.

Nearly half the book takes up other topics, and I regret that I have not managed to discuss them. For instance, Wolterstorff's discussion of privacy rights is particularly important. Take the case of J. Edgar Hoover's spying on Martin Luther King, Jr. Hoover secretly taped King's personal conversations and sex life. Suppose for a moment that King never knew of the privacy invasions, and so made no decisions in light them; suppose Hoover made the recordings for his own prurient enjoyment. (In fact, the FBI did try to blackmail King with these materials, as David Garrow's biography of King indicates. Wolterstorff notes this in one place (223), but not in another (326).) Standard accounts usually try to explain rights violations in terms of constriction of the rights holder's normative agency, or of his freedom of opinion and action. But in the imagined case, King's normative agency was not so affected. Still, his rights clearly were violated. Standard accounts of rights cannot adequately explain the wrongfulness of privacy violation, or the depth of the wrongness of rape, and are accordingly deficient.

Another chapter concerns the nature and source of the political authority of the state -- the state's authority to issue binding directives to its citizens. This issue, long a mainstay in political philosophy, largely dropped out of discussion a few decades ago. Wolterstorff resurrects it and offers an interesting new account.

Wolterstorff's prose and thinking are clear. The book would work well in an upper-level undergraduate or graduate course on liberalism . [2]

[1] In personal correspondence, Wolterstorff says that he does believe that citizens are under a moral demand to engage others, although a failure to so engage is not a violation of the governing idea of liberal democracy.

[2] My thanks to Nick Wolterstorff and Apryl Martin for their feedback on an earlier version of this review.

- Utility Menu

Michael J. Sandel

Anne t. and robert m. bass professor of government, public philosophy: essays on morality in politics.

“Michael Sandel…believes that liberal appeals to individual rights and to the broad values of fairness and equality make a poor case for the progressive case, both as a matter of strategy and as a matter of principle. The country and the Democratic party would be better off, he thinks, if progressives made more of an effort to inspire the majority to adopt their vision of the common good and make it the democratic ground for public policy and law… Anyone concerned over the political success of conservatism in recent years must be interested in this critical analysis.” — Thomas Nagel , The New York Review of Books

“Two messages for progressives sear like bullets through Sandel’s collection of essays. Firstly,…inevitable disagreement about the nature of the good society calls for progressives to engage with controversial moral questions—not to try to avoid them…. Secondly, by seeking to justify egalitarianism in individualistic, rights-based terms, Rawlsian liberals neglect cultivating the citizenship, solidarity and community on which liberty and equality depend…. In recapturing a moral voice for the liberal-left, it is Sandel who seems to offer a more persuasive way forward.” – Graeme Cook, Public Policy Research

“Michael Sandel is one of the most prominent American political philosophers of the post-Rawlsian era…. No doubt liberals will feel discomforted by Sandel’s critiques of individualism, but the critiques have force and must be engaged; they cannot be dismissed as anti-liberal conservatism…. The text can be seen as a call to arms, most directly addressed to the American centre left, to try to win back the arena of values from the right.” – Philip A. Quadrio, Journal of Religious History

“Michael Sandel’s Public Philosophy: Essays on Morality in Politics provides a glimpse into the most influential and best-known debates in Anglo-American political philosophy of the last generation…. This text also provides a wide-ranging introduction to Sandel’s work in political theory and its link to the domain of everyday politics.” – Aaron Cooley, International Journal of Philosophical Studies

“Harvard political theorist Michael Sandel is among the most respected and nuanced of contemporary commentators on American liberalism…. Despite their disparate subjects, the essays cohere amazingly well, visiting from different angles the question of whether including moral and religious concepts in American political discourse is at odds with liberal goods and ideals…. Sandel’s academic essays engage difficult concepts lucidly and even handedly, and his consistently provocative popular commentaries not only discuss the importance of substantive public philosophy, they exemplify it, raising the level of our political and moral discourse in a supremely accessible manner.” – Timothy M. Renick , Religious Studies Review

“[Sandel] explains that our living in a pluralist society with differing moral ideals does not inhibit our discussion of issues like abortion and stem-cell research but instead helps us resolve them by looking at what it means to live ‘a good life.’ This thought-provoking book will be valuable to the general reader as well as scholars.” — Scott Duimstra , Library Journal

“ Public Philosophy stands an integral text in the quest for recovering, and rediscovering, an ethically and morally responsible citizenry and political system.” – Jay M. Hudkins, Rhetoric & Public Affairs

“This new volume, which collects articles previously published between 1983 and 2004, provides a valuable overview of what Sandel calls his ‘public philosophy’… His arguments are broad-ranging, lucid, and sincere in their concern for our current public maladies. As such, they demand attention and engagement…. [Sandel] seeks to recover a politics rooted in the common good and the virtues necessary for broader and deeper civic engagement.” — William Lund , Social Theory and Practice

“No matter what your politics are, you will find Michael Sandel’s Public Philosophy exciting, invigorating, discerning and encouraging. Conservatives will discover a liberalism they didn’t know existed: profoundly concerned with responsibility, community and the importance of individual virtue. Liberals and Democrats who know their side needs an engaging public philosophy will find its bricks and mortar, its contours and basic principles, right here in these pages. To a political debate that is too often dispiriting and sterile, Sandel has offered a brilliant and badly needed antidote.” — E.J. Dionne, Jr ., syndicated columnist, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, professor at Georgetown University

“Michael Sandel can always be counted on to write with elegance and intelligence about important things. Whether you agree or not, you cannot ignore his arguments. We need all the sane voices we can get in the public square and Sandel’s is one of the sanest.” — Jean Bethke Elshtain , The University of Chicago Divinity School

“Michael Sandel is one of the world’s best known and most influential political theorists. He is unusual for the range of practical ethical issues that he has addressed: life, death, sports, religion, commerce, and more. These essays are lucid, pointed, often highly subtle and revealing. Sandel has something important and worthwhile to say about every topic he addresses.” — Stephen Macedo , Princeton University

Recent Publications

- Michael Sandel: ‘The energy of Brexiteers and Trump is born of the failure of elites'

- The Moral Economy of Speculation: Gambling, Finance, and the Common Good

- Market Reasoning as Moral Reasoning: Why Economists Should Re-engage with Political Philosophy

- What Isn’t for Sale?

- What Money Can't Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets

- Obama and Civic Idealism

Professor Herman Cappelen

Chair Professor of Philosophy at the University of Hong Kong

The Concept of Democracy: An Essay on Conceptual Amelioration and Abandonment

Oxford University Press, 2023

Abstract of The Concept of Democracy [+]

If we don't know what the words 'democracy' and 'democratic' mean, then we don't know what democracy is. This book defends a radical view: these words mean nothing and should be abandoned. The argument for Abolitionism is simple: those terms are defective and we can easily do better, so let's get rid of them. According to the abolitionist, the switch to alternative devices would be a significant communicative, cognitive, and political advance.

The first part of the book presents a general theory of abandonment: the conditions under which language should be abandoned. The rest of the book applies this general theory to the case of 'democracy' and 'democratic'. Cappelen shows that 'democracy' and 'democratic' are semantically, pragmatically, and communicatively defective.

Abolitionism is not all gloom and doom. It also contains a message of good cheer: we have easy access to conceptual devices that are more effective than 'democracy'. We can do better. These alternative linguistic devices will enable us to ask better questions, provide genuinely fruitful answers, and have more rational discussions. Moreover, those questions and answers better articulate the communicative and cognitive aims of those who use empty terms like 'democracy' and 'democratic'.

Table of Contents [+]

- Preface & Acknowledgements

- Part I: A Theory of Abandonment

- Introduction

- Arguments for Abandonment

- Abandonment compared to Elimination, Reduction, Replacement, and Amelioration

- Abandonment and Communication

- Part II: Some Data about 'Democracy'

- The Ordinary Notion of 'Democracy': Methodological Preamble

- OSome Data about 'Democracy' and 'Democratic'

- Part III: Abandonment of 'Democracy'?

- Problems with 'Democracy'

- Better than 'Democracy': A Chapter of Good Cheers

- Consequences of Abandoning 'Democracy'

- Part IV: Democracy Ameliorated

- Ameliorations of 'Democracy'

- Verbal Disputes about 'Democracy's

- Part V: Efforts to Defend Democracy

- Objections and Replies

- Bibliography

Making AI Intelligible: Philosophical Foundations

Herman Cappelen and Josh Dever Oxford University Press, 2021

Abstract of Making AI Intelligible [+]

Can humans and artificial intelligences share concepts and communicate? Making AI Intelligible shows that philosophical work on the metaphysics of meaning can help answer these questions. Herman Cappelen and Josh Dever use the externalist tradition in philosophy to create models of how AIs and humans can understand each other. In doing so, they illustrate ways in which that philosophical tradition can be improved.

The questions addressed in the book are not only theoretically interesting, but the answers have pressing practical implications. Many important decisions about human life are now influenced by AI. In giving that power to AI, we presuppose that AIs can track features of the world that we care about (for example, creditworthiness, recidivism, cancer, and combatants). If AIs can share our concepts, that will go some way towards justifying this reliance on AI. This ground-breaking study offers insight into how to take some first steps towards achieving Interpretable AI.

- PART I: INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

- Alfred (The Dismissive Sceptic): Philosophers, Go Away!

- PART II: A PROPOSAL FOR HOW TO ATTRIBUTE CONTENT TO AI

- Terminology: Aboutness, Representation, and Metasemantics

- Our Theory: De-Anthropocentrized Externalism

- Application: The Predicate 'High Risk'

- Application: Names and the Mental Files Framework

- Application: Predication and Commitment

- Four Concluding Thoughts

Making AI Intelligible is available as Open Access from OUP here .

Reviews of Making AI Intelligible [+]

- 'Making AI Intelligible is a thought-provoking overview of the resources available in the contemporary philosophy of language, and their potential application to the interpretation of AI systems. ... One intriguing conclusion drawn by the authors is not then that modern philosophy of language is ill-suited for AI systems, but that it must overcome its admittedly anthropocentric bias in order to better grasp the nature of content.' — Paul Dicken in Los Angeles Review of Books

- 'Making AI Intelligible begins an original, creative, and ambitious project, which contributes both to the scientist's search for alternative methods to make sense of a phenomenon, as well as the philosopher's search for her own blind spots.' — Nikhil Mahant in The Philosophical Quarterly

Listen to New Books Network Podcast on Making AI Intelligible .

Making AI Intelligible can be ordered at Amazon.co.uk .

Conceptual Engineering and Conceptual Ethics

Edited by Alexis Burgess , Herman Cappelen and David Plunkett Oxford University Press, 2019

Conceptual Engineering and Conceptual Ethics is available as Open Access from OUP here .

Fixing Language: An Essay on Conceptual Engineering

Oxford University Press, 2018

Reviews of Fixing Language [+]

- 'Herman Cappelen’s Fixing Language is a fascinating book, chock-full of provocative arguments, on what is fast becoming a (the?) central topic in metaphilosophy: conceptual engineering. It is an important book – one I very highly recommend. It sets the stage for what will be an exciting metaphilosophical debate over the prospects for conceptual engineering in the years to come. ... the book is remarkable for its extensive critical engagement with the work of others, and for its coverage of a dizzying array of issues related to its main theme. As advertised, it's a book about conceptual engineering, but also, and in some cases, equally, it’s a book about metasemantics, verbal disputes, the history of analytic philosophy, meaning change, externalism, inconsistent concepts, generic language, metaphor, slurs, feminist philosophy and contextualism. And that's a partial list.' — Max Deutsch in Analysis

- '... the past few years have seen an explosion of work that is described by its authors as "conceptual engineering"; and Cappelen bears no small share of the responsibility for this. ... I would recommend Fixing Language to anyone interested in meaning and philosophical methodology. This is not only because of the interest of the various ideas Cappelen discusses under the umbrella of the Austerity Framework, but also because of the many acute criticisms of alternative views.' — Derek Ball in Mind

- 'In this lovely and important book, Herman Cappelen organizes and contributes to a rapidly growing literature involving the idea that a, or perhaps the, central role of philosophy is the improvement of concepts. The paramount virtue of his own "austerity" account is that it neither makes improving human beings seem unrealistically easy, nor misconstrues arguments about the world's facts (including the facts about what ought to be the case) as a pointless contest of what middle-era Richard Rorty used to call "vocabularies." ... we should never forget Russell's moving conclusion to The Problems of Philosophy , where he argues that humility is one of the two (along with a heightened sense of the possible) epistemic/moral goods produced by proper reflection on Western philosophy's successes and failures. Anyone sensitive to Russell's wisdom will at least be open to finding Cappelen's intervention in these debates dispositive.' — Jon Cogburn in Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- '...clear and rigorous ... engaging and thought-provoking ... it identifies some of the key issues that any future theory of conceptual engineering will have to address, and offers thought-provoking answers to all of them. Grappling with Cappelen's answers will surely help to bring the meta-philosophical debate about conceptual engineering to a new level.' — Steffen Koch in Logical Analysis and History of Philosophy

Fixing Language can be ordered at Amazon.co.uk .

Contemporary Introductions to Philosophy of Language

- Bad Language (2019) - Puzzles of Reference (2018) - Context and Communication (2017)

Herman Cappelen and Josh Dever Oxford University Press, 2016-2019

Japanese translation of Bad Language is available at Keiso Shobo .

The Oxford Handbook of Philosophical Methodology

Edited by Herman Cappelen, Tamar Gendler and John Hawthorne Oxford University Press, 2016

Reviews of The Oxford Handbook of Philosophical Methodology [+]

- 'All of the contributions contain interesting and thought-provoking material. There is no better place than this volume for graduate students and professional philosophers to get a sophisticated introduction to recent debates about philosophical methods.' — Matthew C. Haug in Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

The Oxford Handbook of Philosophical Methodology is available at Amazon.com .

Liberating Content

Herman Cappelen and Ernest Lepore Oxford University Press, 2015

Liberating Content is available at Amazon.com .

Reviews of Liberating Content [+]

- 'These papers are lively and provocative, dense with arguments that readers will want to assess and respond to.' and '... reading through these papers together is a stimulating and rewarding exercise.' — Curtis Brown in Analysis

The Inessential Indexical: On the Philosophical Insignificance of Perspective and the First Person

Herman Cappelen and Josh Dever Oxford University Press, 2013

Google Preview is available here .

Reviews of The Inessential Indexical [+]

- 'This is a brave and fascinating book in terms of how it takes on a long-standing and largely unchallenged tradition. The book succeeds in its stated aim to show that arguments put forward in favour of essential indexicality are often shallow, border on the rhetorical, and that the notion of "perspective" probably has little philosophical mileage ... a positive synthetic vision [is] beautifully articulated in the final chapter ... according to which "all information is objective information and is used indifferently as such": our "view of the world is not primarily a view from a perspective"; "our beliefs and desires are 'organized around the world' rather than 'around us' ... ".' — W. Hinzen in Mind

- 'This crisp, lean, and tightly argued study deserves the attention of anyone interested in the topics of indexicality, perspective, and the first person ... My prediction is that this fine book will significantly advance the debate about the place of perspective and indexicality in human thought and action.' — Tomis Kapitan in Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- 'In addition to being clear and careful, it presents a fresh perspective on an important topic in philosophy of language, philosophy of mind, and action theory. ... Defenders of essential indexicality should welcome this book as an opportunity to sharpen their arguments and clarify their views.' — P. Atkins in Analysis

The Inessential Indexical is available at Amazon.com .

Philosophy without Intuitions

Oxford University Press, 2012

The first chapter is available here .

Reviews of Philosophy without Intuitions [+]

- 'This is an engaging and exciting book ... Whether one is convinced by its conclusion or not, Philosophy Without Intutions represents a clear jolt to contemporary metaphilosophical orthodoxy. It is a vivid and powerful call for philosophers to examine their assumptions about philosophy. Anyone interested in the role of intuitions in philosophy or the proper description of contemporary philosophical practice will benefit from studying it.' — Jonathan Ichikawa in International Journal for Philosophical Studies

- 'If you're interested in the role of intuitions in philosophy, you need to read this book. Even if you're not particularly concerned by this metaphilosophical issue you would probably still benefit from reading this book, for it may well convince you to change the way in which you articulate your arguments and interpret other authors. Cappelen has made an excellent contribution to the ongoing debate over the importance of intuitions in philosophy.' — Stephen Ingram in Metaphilosophy

- 'Experimental results on the variability and intra-personal instability of philosophical intuitions have recently sparked a lively methodological debate about the reliability of the philosophical method. In his new book, Herman Cappelen argues that this entire debate is misguided. The reason is simple: philosophers don’t rely on intuitions, so there is no reason for philosophers to worry about their reliability. Cappelen’s case for this claim amounts to one of the most original and well-argued contributions to recent discussions about philosophical methodology. His book should be essential reading for anyone interested in the debate.' — Kristoffer Ahlstorm-Vij in Philosophical Quarterly

- 'wonderfully clear ... this is a well-argued, interesting book, challenging contemporary metaphilosophy fundamentally; I highly recommend it.' — Daniel Cohnitz in Disputatio

- 'In this imaginative book, Herman Cappelen challenges two key orthodoxies: that philosophers, as a matter of fact, rely upon intuitions in their everyday practice; and that it is legitimate for them to do so. What he wants is a philosophy purged of intuition-talk, since he believes such talk is idle when we consider how contemporary philosophers actually proceed in dealing with philosophical problems....this is a thought-provoking book that explores important questions about how philosophical research proceeds and, indeed, what philosophical progress might look like. Any future methodological work in philosophy that makes substantive use of the idea of intuitions needs to respond to Cappelen's challenges.' — Adrian Walsh in Australasian Journal of Philosophy (92(1), p.183)

Symposia on Philosophy without Intuitions [+]

- John Bengson (' How Philosophers use Intuition and 'Intuition' ')

- David Chalmers (' Intuitions in Philosophy: A Minimal Defense ')

- Brian Weatherson (' Centrality and Marginalisation ')

- Precis of Philosophy without Intuitions

- Socratic Knowledge and its Role in Philosophy: Reply to Weatherson

- Philosophy without Minimal Intuitions: Reply to Chalmers

- An Enormous Mistake: Experimental Philosophy: Reply to Weinberg

- On the interpretation of 'Intuition'-talk in Naming and Necessity: Reply to Bengson

- Paul Boghossian ('Cappelen on Intuitions')

- Brit Brogaard (' Intuitions and Intellectual Seemings ')

- Mark Richard ('Analysis and Intuitions')

- Twin Earth and Intuitions: Reply to Boghossian

- Intuitions and Intellectual Seemings: Reply to Brogaard

- Conceptual Structure, Indeterminacy, and Intuitions: Reply to Richard

More on Philosophy without Intuitions [+]

- Interview from New Books in Philosophy .

- Boghossian and Cappelen on Philosophy without Intuitions, at UCD on YouTube.

Related work [+]

- X-Phi Without Intuitions? , forthcoming in Anthony Booth and Darrell Rowbottom, eds., Intuition , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Philosophy without Intuitions is available at Amazon.com .

Assertion: New Philosophical Essays

Edited by Jessica Brown and Herman Cappelen Oxford University Press, 2010

Reviews of Assertion [+]

- '... this book is really a terrific contribution to the field and both authors and editors are to be commended for breaking new ground on this very important speech act. The collection is full of fresh, interesting insights and clear arguments that will provide many a philosopher with a deeply explored dialectic to work within. If I were to teach a (graduate) class on assertion, many if not all of these essays would be required reading.' — Adam Sennet in Analysis Reviews (2013, 73.1, 177-180)

Assertion is available at Amazon.com .

Relativism and Monadic Truth

Herman Cappelen and John Hawthorne Oxford University Press, 2009

Reviews of Relativism and Monadic Truth [+]

- 'Relativism and Monadic Truth is a work full of philosophical insights, combined with theoretical ingenuity and dexterity in application ... Their book will drive forward research in the field for some time to come, and is therefore essential lreading for those working in the philosophy of language.' — Brian Ball in Logical Analysis and the History of Philosophy (13, 148-155)

- 'Relativism and Monadic Truth is an eminently readable book. The pace is fast, the style is witty, a wealth of interesting issues are raised in only 148 pages. Some of these issues are cursorily treated, but this is intentional. The idea is to create the impression that there are overwhelmingly many pieces of evidence, some strong, others more speculative, but all pointing in the same direction: Truth is monadic, propositions are true or false simpliciter ... both specialists and a philosophically interested general audience may be inspired by it, or provoked by it, to undertake a deeper scrutiny of the charms of simplicity.' — Alexander Almer and Dag Westerstahl in Linguistics and Philosophy (2010, 33, 37–50)

Symposia on Relativism and Monadic Truth [+]

- Philosophical Studies Symposium (Peter Lasersohn, John MacFarlane ( "Simplicity Made Difficult" ), Mark Richard).

- Analysis Symposium (Michael Glanzberg, Scott Soames ( "True At" ), Brian Weatherson ( "No Royal Road to Relativism" )).

- Author-Meets-Critic Session, 2010 APA Central Division meeting. Critics: Andy Egan, Ernest Lepore, Scott Soames, Adam Sennet.

Relativism and Monadic Truth is available at Amazon.com .

Language Turned on Itself: The Semantics and Pragmatics of Metalinguistic Discourse

Herman Cappelen and Ernest Lepore Oxford University Press, 2007

Read more: Oxford University Press

Reviews of Language Turned on Itself [+]

- 'It is particularly gratifying to have this lively compact monograph by Herman Cappelen and Ernie Lepore ... With their usual flair C&L explain why we should study quotation; they lay out the leading issues in the literature; they criticize prior theories, including the demonstrative theory they are so well known for; they introduce a new version of the identity-function theory; and they offer a valuable essay on an unduly neglected topic in philosophy of language, that of the metaphysics of signs.' — Paul Sakain in Protosociology

Language Turned on Itself is available at Amazon.com .

Insensitive Semantics: A Defense of Semantic Minimalism and Speech Act Pluralism

Herman Cappelen and Ernest Lepore Blackwell Publishers, 2004

Reviews of Insensitive Semantics [+]

- 'Overall, this is an excellent book. It sets a standard for clarity and explicitness of argumentation that few philosophical works equal. Cappelen and Lepore’s insights into debates concerning context sensitivity are many and profound. The challenges they set before contextualists of all kinds should set the terms of debate for some time to come.' — Daniel Bonevac in Philosophical Books (2008, 157-161)

- 'This is a book of considerable importance, which deals with a topic currently at the center of research in the philosophy of language. As a result, Insensitive Semantics has been and will continue to be widely discussed This book pushes the discussion of context–sensitivity forward in new and useful directions. Read it and learn from it.' — Rob Stainton in Journal of Linguistics

Symposia on Insensitive Semantics [+]

- Mind & Language Symposium . Replies by Ann Bezuidenhout, Steven Gross, Francois Recanati, Zoltan Szabo and Charles Travis.

- Philosophy and Phenomenological Research Symposium . Replies by Kent Bach, John Hawthorne, Kepa Korta & John Perry, and Rob Stainton.

More on Insensitive Semantics [+]

- Context Sensitivity and Semantic Minimalism: New Essays on Semantics and Pragmatics (Oxford University Press, 2007, Preyer and Peter (eds)). Collection of 14 essays discussing Insensitive Semantics.

Insensitive Semantics is available at Amazon.com .

Chinese Translation of Insensitive Semantics is available at Yilin.com and Amazon.cn .

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

- A fall quarter course uses Ancient Athens as a case study to explore practical and philosophical questions about how democracy functions.

- For ancient Athenians, political participation was intertwined with leading an ethical life; being part of a well-run society was seen as essential to human flourishing.

- At the heart of the decision-making process was the “demos” – the Greek word for people – and the “kratos” – the Greek word for rule.

- Knowing they would be called upon to deal with difficult issues had a profound effect on the way Athenian citizens related with the world around them.

With over 4 billion citizens in some 65 countries participating in an election in 2024, the year is being heralded as a historic period – and test – for democracy . In a winter quarter course at Stanford, students examined another important time for self-government: the fifth century BCE, when democracy first emerged.

Each week, Stanford political scientist and classicist Josiah Ober conjured what political life was like in the Greek city-state of Athens to the mix of undergraduate, graduate, and postdoctoral students taking POLISCI 231A: Democracy Ancient and Modern: From Politics to Political Theory . Ober drew on texts by contemporary Greek historians and political theorists who focus on ancient democracy to explore with students some of the issues ancient Athenians grappled with as they put self-government into practice.

For Ober, who has studied ancient and modern political thought for over four decades, ancient Athens makes for an interesting case study for students and scholars to examine how democracy functions and the different forms this mode of government can take.

In a winter quarter course, political scientist and classicist Josiah Ober teaches students about the foundations of democracy. | Andrew Brodhead

“It gives you these possibilities of the different ways democracy could be done,” said Ober, the Markos & Eleni Kounalakis Chair in Honor of Constantine Mitsotakis in the School of Humanities and Sciences . “History gives you some advantages to test a political theory and find out if it could possibly work.”

Other ways to do democracy

In running their democracy, ancient Athenians did many things differently that students considered closely throughout the course.

For one, the political life of its citizens was incredibly active.

Unlike the American system of representative democracy, where citizens vote for elected officials to represent their concerns in government, rule in Ancient Greece was direct: Participation was not a choice but a civic duty.

For ancient Athenians, being political was intertwined with leading an ethical life: Being part of a well-run society was seen as essential to human flourishing.

As Ober explained, by the time an Athenian citizen was 30 years old, it was highly likely they had already participated in the Assembly – the governing body where 5,000 or 6,000 citizens regularly met to vote on important issues of the day – or even served on the Council, a group of 500 citizens randomly chosen by lottery to serve 10-month terms to help set the Assembly’s agenda (ancient Athenians frequently drew on lotteries to distribute civic responsibilities among its citizens; in the U.S., they are scarcely used – the only thing close is jury duty).

For Athenian citizens, knowing they would be called upon to deal with difficult issues and decisions – like whether to go to war – had a profound effect on the way they related with the world around them.

“The way in which Athenians conducted their lives was highly influenced by the fact that they were going to have some real responsibility for their community,” Ober said. “When an Athenian went to the Assembly and voted for war, he was sending himself to war.”

Democracy isn’t something that is inherent or is going to be given to you. It’s something that you need to work at.” Cameron Adams, ’24 Senior majoring in political science

At the heart of the Assembly’s decision-making process was the “demos” – the Greek word for people – and the “kratos” – the Greek word for rule (the etymological root of democracy comes from these two words).

In a class seminar devoted to deliberation, Ober described how the citizen Assembly made decisions and how those decisions represented the will of the demos, the collective judgment of the people about the best available course of action. The class then discussed some of the tensions that arise when conceptualizing a large, diverse population as a monolithic entity.

They also debated questions about accountability. If the decisions made by the Assembly were that of the demos, did that mean that individuals were no longer responsible for the decisions they contributed to making? Which raised another question: What does a democracy look like when officials are accountable to the people, but “the people” are accountable to no one?

Tackling complex questions like these – which are political, philosophical, and practical in nature – formed the basis of many of the students’ discussions.

For Michael Thomas, a second-year PhD student who took the course, examining how the ancient Greeks approached civic engagement and education has made him think about what could happen if American society did something similar.

Michael Thomas is a second-year PhD student in the Department of Political Science. | Andrew Brodhead

“We ask ourselves a lot about how to do democratic education and a great deal of it for the Greeks was by doing, such as governing through the Assembly and holding office,” Thomas said. “I think people would feel more committed to democracy if they experienced it in their own lives through participating in collective action.”

Learning from limitations

But not everyone in ancient Athens was able to participate in political life.

Excluded from the franchise were women and slaves – not too dissimilar to the limitations America’s Founding Fathers set when they wrote the Declaration of Independence, Constitution, and the Bill of Rights in the late 18th century.

For political science major Cameron Adams, ’24, learning how Athenians restricted democratic participation has helped them better understand barriers in American democracy.

“We modeled our democracy after Athenian democracy, which was flawed, so it makes sense that our system is flawed,” said Adams, who took two of the courses Ober taught in winter quarter.

I think people would feel more committed to democracy if they experienced it in their own lives through participating in collective action.” Michael Thomas Second-year PhD student in the Department of Political Science

Even with a series of reforms in the 20th century that expanded and protected U.S. voting rights to include women and people of color, there are still groups of Americans today who are ineligible to participate in an election. For example, people with a criminal conviction may be blocked from voting in their state. People have also become disenfranchised by being forced to face long wait times at polling stations or not being provided enough places to vote .

While learning how ancient Athenians grappled with who was and was not able to participate in democratic life, Adams considered contemporary problems like these. One essay Adams read that they found particularly relevant examined the ways in which women and slaves in ancient Athens found ways to speak out against the injustices they faced.

“It illuminates that democracy isn’t something that is inherent or is going to be given to you,” Adams said. “It’s something that you need to work at.”

30,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

Essay on Democracy in 100, 300 and 500 Words

- Updated on

- Jan 15, 2024

The oldest account of democracy can be traced back to 508–507 BCC Athens . Today there are over 50 different types of democracy across the world. But, what is the ideal form of democracy? Why is democracy considered the epitome of freedom and rights around the globe? Let’s explore what self-governance is and how you can write a creative and informative essay on democracy and its significance.

Today, India is the largest democracy with a population of 1.41 billion and counting. Everyone in India above the age of 18 is given the right to vote and elect their representative. Isn’t it beautiful, when people are given the option to vote for their leader, one that understands their problems and promises to end their miseries? This is just one feature of democracy , for we have a lot of samples for you in the essay on democracy. Stay tuned!

Can you answer these questions in under 5 minutes? Take the Ultimate GK Quiz to find out!

This Blog Includes:

What is democracy , sample essay on democracy (100 words), sample essay on democracy (250 to 300 words), sample essay on democracy for upsc (500 words).

Democracy is a form of government in which the final authority to deliberate and decide the legislation for the country lies with the people, either directly or through representatives. Within a democracy, the method of decision-making, and the demarcation of citizens vary among countries. However, some fundamental principles of democracy include the rule of law, inclusivity, political deliberations, voting via elections , etc.

Did you know: On 15th August 1947, India became the world’s largest democracy after adopting the Indian Constitution and granting fundamental rights to its citizens?

Must Explore: Human Rights Courses for Students

Must Explore: NCERT Notes on Separation of Powers in a Democracy