Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- How to Write a Results Section | Tips & Examples

How to Write a Results Section | Tips & Examples

Published on August 30, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on July 18, 2023.

A results section is where you report the main findings of the data collection and analysis you conducted for your thesis or dissertation . You should report all relevant results concisely and objectively, in a logical order. Don’t include subjective interpretations of why you found these results or what they mean—any evaluation should be saved for the discussion section .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

How to write a results section, reporting quantitative research results, reporting qualitative research results, results vs. discussion vs. conclusion, checklist: research results, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about results sections.

When conducting research, it’s important to report the results of your study prior to discussing your interpretations of it. This gives your reader a clear idea of exactly what you found and keeps the data itself separate from your subjective analysis.

Here are a few best practices:

- Your results should always be written in the past tense.

- While the length of this section depends on how much data you collected and analyzed, it should be written as concisely as possible.

- Only include results that are directly relevant to answering your research questions . Avoid speculative or interpretative words like “appears” or “implies.”

- If you have other results you’d like to include, consider adding them to an appendix or footnotes.

- Always start out with your broadest results first, and then flow into your more granular (but still relevant) ones. Think of it like a shoe store: first discuss the shoes as a whole, then the sneakers, boots, sandals, etc.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

If you conducted quantitative research , you’ll likely be working with the results of some sort of statistical analysis .

Your results section should report the results of any statistical tests you used to compare groups or assess relationships between variables . It should also state whether or not each hypothesis was supported.

The most logical way to structure quantitative results is to frame them around your research questions or hypotheses. For each question or hypothesis, share:

- A reminder of the type of analysis you used (e.g., a two-sample t test or simple linear regression ). A more detailed description of your analysis should go in your methodology section.

- A concise summary of each relevant result, both positive and negative. This can include any relevant descriptive statistics (e.g., means and standard deviations ) as well as inferential statistics (e.g., t scores, degrees of freedom , and p values ). Remember, these numbers are often placed in parentheses.

- A brief statement of how each result relates to the question, or whether the hypothesis was supported. You can briefly mention any results that didn’t fit with your expectations and assumptions, but save any speculation on their meaning or consequences for your discussion and conclusion.

A note on tables and figures

In quantitative research, it’s often helpful to include visual elements such as graphs, charts, and tables , but only if they are directly relevant to your results. Give these elements clear, descriptive titles and labels so that your reader can easily understand what is being shown. If you want to include any other visual elements that are more tangential in nature, consider adding a figure and table list .

As a rule of thumb:

- Tables are used to communicate exact values, giving a concise overview of various results

- Graphs and charts are used to visualize trends and relationships, giving an at-a-glance illustration of key findings

Don’t forget to also mention any tables and figures you used within the text of your results section. Summarize or elaborate on specific aspects you think your reader should know about rather than merely restating the same numbers already shown.

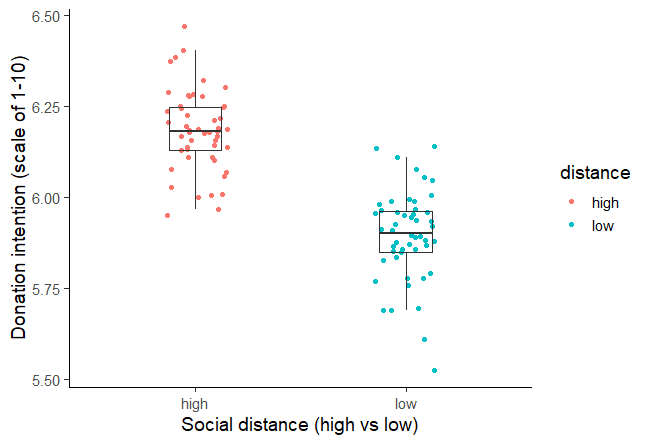

A two-sample t test was used to test the hypothesis that higher social distance from environmental problems would reduce the intent to donate to environmental organizations, with donation intention (recorded as a score from 1 to 10) as the outcome variable and social distance (categorized as either a low or high level of social distance) as the predictor variable.Social distance was found to be positively correlated with donation intention, t (98) = 12.19, p < .001, with the donation intention of the high social distance group 0.28 points higher, on average, than the low social distance group (see figure 1). This contradicts the initial hypothesis that social distance would decrease donation intention, and in fact suggests a small effect in the opposite direction.

Figure 1: Intention to donate to environmental organizations based on social distance from impact of environmental damage.

In qualitative research , your results might not all be directly related to specific hypotheses. In this case, you can structure your results section around key themes or topics that emerged from your analysis of the data.

For each theme, start with general observations about what the data showed. You can mention:

- Recurring points of agreement or disagreement

- Patterns and trends

- Particularly significant snippets from individual responses

Next, clarify and support these points with direct quotations. Be sure to report any relevant demographic information about participants. Further information (such as full transcripts , if appropriate) can be included in an appendix .

When asked about video games as a form of art, the respondents tended to believe that video games themselves are not an art form, but agreed that creativity is involved in their production. The criteria used to identify artistic video games included design, story, music, and creative teams.One respondent (male, 24) noted a difference in creativity between popular video game genres:

“I think that in role-playing games, there’s more attention to character design, to world design, because the whole story is important and more attention is paid to certain game elements […] so that perhaps you do need bigger teams of creative experts than in an average shooter or something.”

Responses suggest that video game consumers consider some types of games to have more artistic potential than others.

Your results section should objectively report your findings, presenting only brief observations in relation to each question, hypothesis, or theme.

It should not speculate about the meaning of the results or attempt to answer your main research question . Detailed interpretation of your results is more suitable for your discussion section , while synthesis of your results into an overall answer to your main research question is best left for your conclusion .

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

I have completed my data collection and analyzed the results.

I have included all results that are relevant to my research questions.

I have concisely and objectively reported each result, including relevant descriptive statistics and inferential statistics .

I have stated whether each hypothesis was supported or refuted.

I have used tables and figures to illustrate my results where appropriate.

All tables and figures are correctly labelled and referred to in the text.

There is no subjective interpretation or speculation on the meaning of the results.

You've finished writing up your results! Use the other checklists to further improve your thesis.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Survivorship bias

- Self-serving bias

- Availability heuristic

- Halo effect

- Hindsight bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

The results chapter of a thesis or dissertation presents your research results concisely and objectively.

In quantitative research , for each question or hypothesis , state:

- The type of analysis used

- Relevant results in the form of descriptive and inferential statistics

- Whether or not the alternative hypothesis was supported

In qualitative research , for each question or theme, describe:

- Recurring patterns

- Significant or representative individual responses

- Relevant quotations from the data

Don’t interpret or speculate in the results chapter.

Results are usually written in the past tense , because they are describing the outcome of completed actions.

The results chapter or section simply and objectively reports what you found, without speculating on why you found these results. The discussion interprets the meaning of the results, puts them in context, and explains why they matter.

In qualitative research , results and discussion are sometimes combined. But in quantitative research , it’s considered important to separate the objective results from your interpretation of them.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, July 18). How to Write a Results Section | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 17, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/results/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a discussion section | tips & examples, how to write a thesis or dissertation conclusion, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Results Section – Writing Guide and Examples

Research Results Section – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Results

Research results refer to the findings and conclusions derived from a systematic investigation or study conducted to answer a specific question or hypothesis. These results are typically presented in a written report or paper and can include various forms of data such as numerical data, qualitative data, statistics, charts, graphs, and visual aids.

Results Section in Research

The results section of the research paper presents the findings of the study. It is the part of the paper where the researcher reports the data collected during the study and analyzes it to draw conclusions.

In the results section, the researcher should describe the data that was collected, the statistical analysis performed, and the findings of the study. It is important to be objective and not interpret the data in this section. Instead, the researcher should report the data as accurately and objectively as possible.

Structure of Research Results Section

The structure of the research results section can vary depending on the type of research conducted, but in general, it should contain the following components:

- Introduction: The introduction should provide an overview of the study, its aims, and its research questions. It should also briefly explain the methodology used to conduct the study.

- Data presentation : This section presents the data collected during the study. It may include tables, graphs, or other visual aids to help readers better understand the data. The data presented should be organized in a logical and coherent way, with headings and subheadings used to help guide the reader.

- Data analysis: In this section, the data presented in the previous section are analyzed and interpreted. The statistical tests used to analyze the data should be clearly explained, and the results of the tests should be presented in a way that is easy to understand.

- Discussion of results : This section should provide an interpretation of the results of the study, including a discussion of any unexpected findings. The discussion should also address the study’s research questions and explain how the results contribute to the field of study.

- Limitations: This section should acknowledge any limitations of the study, such as sample size, data collection methods, or other factors that may have influenced the results.

- Conclusions: The conclusions should summarize the main findings of the study and provide a final interpretation of the results. The conclusions should also address the study’s research questions and explain how the results contribute to the field of study.

- Recommendations : This section may provide recommendations for future research based on the study’s findings. It may also suggest practical applications for the study’s results in real-world settings.

Outline of Research Results Section

The following is an outline of the key components typically included in the Results section:

I. Introduction

- A brief overview of the research objectives and hypotheses

- A statement of the research question

II. Descriptive statistics

- Summary statistics (e.g., mean, standard deviation) for each variable analyzed

- Frequencies and percentages for categorical variables

III. Inferential statistics

- Results of statistical analyses, including tests of hypotheses

- Tables or figures to display statistical results

IV. Effect sizes and confidence intervals

- Effect sizes (e.g., Cohen’s d, odds ratio) to quantify the strength of the relationship between variables

- Confidence intervals to estimate the range of plausible values for the effect size

V. Subgroup analyses

- Results of analyses that examined differences between subgroups (e.g., by gender, age, treatment group)

VI. Limitations and assumptions

- Discussion of any limitations of the study and potential sources of bias

- Assumptions made in the statistical analyses

VII. Conclusions

- A summary of the key findings and their implications

- A statement of whether the hypotheses were supported or not

- Suggestions for future research

Example of Research Results Section

An Example of a Research Results Section could be:

- This study sought to examine the relationship between sleep quality and academic performance in college students.

- Hypothesis : College students who report better sleep quality will have higher GPAs than those who report poor sleep quality.

- Methodology : Participants completed a survey about their sleep habits and academic performance.

II. Participants

- Participants were college students (N=200) from a mid-sized public university in the United States.

- The sample was evenly split by gender (50% female, 50% male) and predominantly white (85%).

- Participants were recruited through flyers and online advertisements.

III. Results

- Participants who reported better sleep quality had significantly higher GPAs (M=3.5, SD=0.5) than those who reported poor sleep quality (M=2.9, SD=0.6).

- See Table 1 for a summary of the results.

- Participants who reported consistent sleep schedules had higher GPAs than those with irregular sleep schedules.

IV. Discussion

- The results support the hypothesis that better sleep quality is associated with higher academic performance in college students.

- These findings have implications for college students, as prioritizing sleep could lead to better academic outcomes.

- Limitations of the study include self-reported data and the lack of control for other variables that could impact academic performance.

V. Conclusion

- College students who prioritize sleep may see a positive impact on their academic performance.

- These findings highlight the importance of sleep in academic success.

- Future research could explore interventions to improve sleep quality in college students.

Example of Research Results in Research Paper :

Our study aimed to compare the performance of three different machine learning algorithms (Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, and Neural Network) in predicting customer churn in a telecommunications company. We collected a dataset of 10,000 customer records, with 20 predictor variables and a binary churn outcome variable.

Our analysis revealed that all three algorithms performed well in predicting customer churn, with an overall accuracy of 85%. However, the Random Forest algorithm showed the highest accuracy (88%), followed by the Support Vector Machine (86%) and the Neural Network (84%).

Furthermore, we found that the most important predictor variables for customer churn were monthly charges, contract type, and tenure. Random Forest identified monthly charges as the most important variable, while Support Vector Machine and Neural Network identified contract type as the most important.

Overall, our results suggest that machine learning algorithms can be effective in predicting customer churn in a telecommunications company, and that Random Forest is the most accurate algorithm for this task.

Example 3 :

Title : The Impact of Social Media on Body Image and Self-Esteem

Abstract : This study aimed to investigate the relationship between social media use, body image, and self-esteem among young adults. A total of 200 participants were recruited from a university and completed self-report measures of social media use, body image satisfaction, and self-esteem.

Results: The results showed that social media use was significantly associated with body image dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem. Specifically, participants who reported spending more time on social media platforms had lower levels of body image satisfaction and self-esteem compared to those who reported less social media use. Moreover, the study found that comparing oneself to others on social media was a significant predictor of body image dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem.

Conclusion : These results suggest that social media use can have negative effects on body image satisfaction and self-esteem among young adults. It is important for individuals to be mindful of their social media use and to recognize the potential negative impact it can have on their mental health. Furthermore, interventions aimed at promoting positive body image and self-esteem should take into account the role of social media in shaping these attitudes and behaviors.

Importance of Research Results

Research results are important for several reasons, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research results can contribute to the advancement of knowledge in a particular field, whether it be in science, technology, medicine, social sciences, or humanities.

- Developing theories: Research results can help to develop or modify existing theories and create new ones.

- Improving practices: Research results can inform and improve practices in various fields, such as education, healthcare, business, and public policy.

- Identifying problems and solutions: Research results can identify problems and provide solutions to complex issues in society, including issues related to health, environment, social justice, and economics.

- Validating claims : Research results can validate or refute claims made by individuals or groups in society, such as politicians, corporations, or activists.

- Providing evidence: Research results can provide evidence to support decision-making, policy-making, and resource allocation in various fields.

How to Write Results in A Research Paper

Here are some general guidelines on how to write results in a research paper:

- Organize the results section: Start by organizing the results section in a logical and coherent manner. Divide the section into subsections if necessary, based on the research questions or hypotheses.

- Present the findings: Present the findings in a clear and concise manner. Use tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data and make the presentation more engaging.

- Describe the data: Describe the data in detail, including the sample size, response rate, and any missing data. Provide relevant descriptive statistics such as means, standard deviations, and ranges.

- Interpret the findings: Interpret the findings in light of the research questions or hypotheses. Discuss the implications of the findings and the extent to which they support or contradict existing theories or previous research.

- Discuss the limitations : Discuss the limitations of the study, including any potential sources of bias or confounding factors that may have affected the results.

- Compare the results : Compare the results with those of previous studies or theoretical predictions. Discuss any similarities, differences, or inconsistencies.

- Avoid redundancy: Avoid repeating information that has already been presented in the introduction or methods sections. Instead, focus on presenting new and relevant information.

- Be objective: Be objective in presenting the results, avoiding any personal biases or interpretations.

When to Write Research Results

Here are situations When to Write Research Results”

- After conducting research on the chosen topic and obtaining relevant data, organize the findings in a structured format that accurately represents the information gathered.

- Once the data has been analyzed and interpreted, and conclusions have been drawn, begin the writing process.

- Before starting to write, ensure that the research results adhere to the guidelines and requirements of the intended audience, such as a scientific journal or academic conference.

- Begin by writing an abstract that briefly summarizes the research question, methodology, findings, and conclusions.

- Follow the abstract with an introduction that provides context for the research, explains its significance, and outlines the research question and objectives.

- The next section should be a literature review that provides an overview of existing research on the topic and highlights the gaps in knowledge that the current research seeks to address.

- The methodology section should provide a detailed explanation of the research design, including the sample size, data collection methods, and analytical techniques used.

- Present the research results in a clear and concise manner, using graphs, tables, and figures to illustrate the findings.

- Discuss the implications of the research results, including how they contribute to the existing body of knowledge on the topic and what further research is needed.

- Conclude the paper by summarizing the main findings, reiterating the significance of the research, and offering suggestions for future research.

Purpose of Research Results

The purposes of Research Results are as follows:

- Informing policy and practice: Research results can provide evidence-based information to inform policy decisions, such as in the fields of healthcare, education, and environmental regulation. They can also inform best practices in fields such as business, engineering, and social work.

- Addressing societal problems : Research results can be used to help address societal problems, such as reducing poverty, improving public health, and promoting social justice.

- Generating economic benefits : Research results can lead to the development of new products, services, and technologies that can create economic value and improve quality of life.

- Supporting academic and professional development : Research results can be used to support academic and professional development by providing opportunities for students, researchers, and practitioners to learn about new findings and methodologies in their field.

- Enhancing public understanding: Research results can help to educate the public about important issues and promote scientific literacy, leading to more informed decision-making and better public policy.

- Evaluating interventions: Research results can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, such as treatments, educational programs, and social policies. This can help to identify areas where improvements are needed and guide future interventions.

- Contributing to scientific progress: Research results can contribute to the advancement of science by providing new insights and discoveries that can lead to new theories, methods, and techniques.

- Informing decision-making : Research results can provide decision-makers with the information they need to make informed decisions. This can include decision-making at the individual, organizational, or governmental levels.

- Fostering collaboration : Research results can facilitate collaboration between researchers and practitioners, leading to new partnerships, interdisciplinary approaches, and innovative solutions to complex problems.

Advantages of Research Results

Some Advantages of Research Results are as follows:

- Improved decision-making: Research results can help inform decision-making in various fields, including medicine, business, and government. For example, research on the effectiveness of different treatments for a particular disease can help doctors make informed decisions about the best course of treatment for their patients.

- Innovation : Research results can lead to the development of new technologies, products, and services. For example, research on renewable energy sources can lead to the development of new and more efficient ways to harness renewable energy.

- Economic benefits: Research results can stimulate economic growth by providing new opportunities for businesses and entrepreneurs. For example, research on new materials or manufacturing techniques can lead to the development of new products and processes that can create new jobs and boost economic activity.

- Improved quality of life: Research results can contribute to improving the quality of life for individuals and society as a whole. For example, research on the causes of a particular disease can lead to the development of new treatments and cures, improving the health and well-being of millions of people.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 7. The Results

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The results section is where you report the findings of your study based upon the methodology [or methodologies] you applied to gather information. The results section should state the findings of the research arranged in a logical sequence without bias or interpretation. A section describing results should be particularly detailed if your paper includes data generated from your own research.

Annesley, Thomas M. "Show Your Cards: The Results Section and the Poker Game." Clinical Chemistry 56 (July 2010): 1066-1070.

Importance of a Good Results Section

When formulating the results section, it's important to remember that the results of a study do not prove anything . Findings can only confirm or reject the hypothesis underpinning your study. However, the act of articulating the results helps you to understand the problem from within, to break it into pieces, and to view the research problem from various perspectives.

The page length of this section is set by the amount and types of data to be reported . Be concise. Use non-textual elements appropriately, such as figures and tables, to present findings more effectively. In deciding what data to describe in your results section, you must clearly distinguish information that would normally be included in a research paper from any raw data or other content that could be included as an appendix. In general, raw data that has not been summarized should not be included in the main text of your paper unless requested to do so by your professor.

Avoid providing data that is not critical to answering the research question . The background information you described in the introduction section should provide the reader with any additional context or explanation needed to understand the results. A good strategy is to always re-read the background section of your paper after you have written up your results to ensure that the reader has enough context to understand the results [and, later, how you interpreted the results in the discussion section of your paper that follows].

Bavdekar, Sandeep B. and Sneha Chandak. "Results: Unraveling the Findings." Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 63 (September 2015): 44-46; Brett, Paul. "A Genre Analysis of the Results Section of Sociology Articles." English for Specific Speakers 13 (1994): 47-59; Go to English for Specific Purposes on ScienceDirect;Burton, Neil et al. Doing Your Education Research Project . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2008; Results. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Results Section. San Francisco Edit; "Reporting Findings." In Making Sense of Social Research Malcolm Williams, editor. (London;: SAGE Publications, 2003) pp. 188-207.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Organization and Approach

For most research papers in the social and behavioral sciences, there are two possible ways of organizing the results . Both approaches are appropriate in how you report your findings, but use only one approach.

- Present a synopsis of the results followed by an explanation of key findings . This approach can be used to highlight important findings. For example, you may have noticed an unusual correlation between two variables during the analysis of your findings. It is appropriate to highlight this finding in the results section. However, speculating as to why this correlation exists and offering a hypothesis about what may be happening belongs in the discussion section of your paper.

- Present a result and then explain it, before presenting the next result then explaining it, and so on, then end with an overall synopsis . This is the preferred approach if you have multiple results of equal significance. It is more common in longer papers because it helps the reader to better understand each finding. In this model, it is helpful to provide a brief conclusion that ties each of the findings together and provides a narrative bridge to the discussion section of the your paper.

NOTE : Just as the literature review should be arranged under conceptual categories rather than systematically describing each source, you should also organize your findings under key themes related to addressing the research problem. This can be done under either format noted above [i.e., a thorough explanation of the key results or a sequential, thematic description and explanation of each finding].

II. Content

In general, the content of your results section should include the following:

- Introductory context for understanding the results by restating the research problem underpinning your study . This is useful in re-orientating the reader's focus back to the research problem after having read a review of the literature and your explanation of the methods used for gathering and analyzing information.

- Inclusion of non-textual elements, such as, figures, charts, photos, maps, tables, etc. to further illustrate key findings, if appropriate . Rather than relying entirely on descriptive text, consider how your findings can be presented visually. This is a helpful way of condensing a lot of data into one place that can then be referred to in the text. Consider referring to appendices if there is a lot of non-textual elements.

- A systematic description of your results, highlighting for the reader observations that are most relevant to the topic under investigation . Not all results that emerge from the methodology used to gather information may be related to answering the " So What? " question. Do not confuse observations with interpretations; observations in this context refers to highlighting important findings you discovered through a process of reviewing prior literature and gathering data.

- The page length of your results section is guided by the amount and types of data to be reported . However, focus on findings that are important and related to addressing the research problem. It is not uncommon to have unanticipated results that are not relevant to answering the research question. This is not to say that you don't acknowledge tangential findings and, in fact, can be referred to as areas for further research in the conclusion of your paper. However, spending time in the results section describing tangential findings clutters your overall results section and distracts the reader.

- A short paragraph that concludes the results section by synthesizing the key findings of the study . Highlight the most important findings you want readers to remember as they transition into the discussion section. This is particularly important if, for example, there are many results to report, the findings are complicated or unanticipated, or they are impactful or actionable in some way [i.e., able to be pursued in a feasible way applied to practice].

NOTE: Always use the past tense when referring to your study's findings. Reference to findings should always be described as having already happened because the method used to gather the information has been completed.

III. Problems to Avoid

When writing the results section, avoid doing the following :

- Discussing or interpreting your results . Save this for the discussion section of your paper, although where appropriate, you should compare or contrast specific results to those found in other studies [e.g., "Similar to the work of Smith [1990], one of the findings of this study is the strong correlation between motivation and academic achievement...."].

- Reporting background information or attempting to explain your findings. This should have been done in your introduction section, but don't panic! Often the results of a study point to the need for additional background information or to explain the topic further, so don't think you did something wrong. Writing up research is rarely a linear process. Always revise your introduction as needed.

- Ignoring negative results . A negative result generally refers to a finding that does not support the underlying assumptions of your study. Do not ignore them. Document these findings and then state in your discussion section why you believe a negative result emerged from your study. Note that negative results, and how you handle them, can give you an opportunity to write a more engaging discussion section, therefore, don't be hesitant to highlight them.

- Including raw data or intermediate calculations . Ask your professor if you need to include any raw data generated by your study, such as transcripts from interviews or data files. If raw data is to be included, place it in an appendix or set of appendices that are referred to in the text.

- Be as factual and concise as possible in reporting your findings . Do not use phrases that are vague or non-specific, such as, "appeared to be greater than other variables..." or "demonstrates promising trends that...." Subjective modifiers should be explained in the discussion section of the paper [i.e., why did one variable appear greater? Or, how does the finding demonstrate a promising trend?].

- Presenting the same data or repeating the same information more than once . If you want to highlight a particular finding, it is appropriate to do so in the results section. However, you should emphasize its significance in relation to addressing the research problem in the discussion section. Do not repeat it in your results section because you can do that in the conclusion of your paper.

- Confusing figures with tables . Be sure to properly label any non-textual elements in your paper. Don't call a chart an illustration or a figure a table. If you are not sure, go here .

Annesley, Thomas M. "Show Your Cards: The Results Section and the Poker Game." Clinical Chemistry 56 (July 2010): 1066-1070; Bavdekar, Sandeep B. and Sneha Chandak. "Results: Unraveling the Findings." Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 63 (September 2015): 44-46; Burton, Neil et al. Doing Your Education Research Project . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2008; Caprette, David R. Writing Research Papers. Experimental Biosciences Resources. Rice University; Hancock, Dawson R. and Bob Algozzine. Doing Case Study Research: A Practical Guide for Beginning Researchers . 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press, 2011; Introduction to Nursing Research: Reporting Research Findings. Nursing Research: Open Access Nursing Research and Review Articles. (January 4, 2012); Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Results Section. San Francisco Edit ; Ng, K. H. and W. C. Peh. "Writing the Results." Singapore Medical Journal 49 (2008): 967-968; Reporting Research Findings. Wilder Research, in partnership with the Minnesota Department of Human Services. (February 2009); Results. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Schafer, Mickey S. Writing the Results. Thesis Writing in the Sciences. Course Syllabus. University of Florida.

Writing Tip

Why Don't I Just Combine the Results Section with the Discussion Section?

It's not unusual to find articles in scholarly social science journals where the author(s) have combined a description of the findings with a discussion about their significance and implications. You could do this. However, if you are inexperienced writing research papers, consider creating two distinct sections for each section in your paper as a way to better organize your thoughts and, by extension, your paper. Think of the results section as the place where you report what your study found; think of the discussion section as the place where you interpret the information and answer the "So What?" question. As you become more skilled writing research papers, you can consider melding the results of your study with a discussion of its implications.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn and Aleksandra Kasztalska. Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

- << Previous: Insiderness

- Next: Using Non-Textual Elements >>

- Last Updated: Apr 16, 2024 10:20 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write the Results/Findings Section in Research

What is the research paper Results section and what does it do?

The Results section of a scientific research paper represents the core findings of a study derived from the methods applied to gather and analyze information. It presents these findings in a logical sequence without bias or interpretation from the author, setting up the reader for later interpretation and evaluation in the Discussion section. A major purpose of the Results section is to break down the data into sentences that show its significance to the research question(s).

The Results section appears third in the section sequence in most scientific papers. It follows the presentation of the Methods and Materials and is presented before the Discussion section —although the Results and Discussion are presented together in many journals. This section answers the basic question “What did you find in your research?”

What is included in the Results section?

The Results section should include the findings of your study and ONLY the findings of your study. The findings include:

- Data presented in tables, charts, graphs, and other figures (may be placed into the text or on separate pages at the end of the manuscript)

- A contextual analysis of this data explaining its meaning in sentence form

- All data that corresponds to the central research question(s)

- All secondary findings (secondary outcomes, subgroup analyses, etc.)

If the scope of the study is broad, or if you studied a variety of variables, or if the methodology used yields a wide range of different results, the author should present only those results that are most relevant to the research question stated in the Introduction section .

As a general rule, any information that does not present the direct findings or outcome of the study should be left out of this section. Unless the journal requests that authors combine the Results and Discussion sections, explanations and interpretations should be omitted from the Results.

How are the results organized?

The best way to organize your Results section is “logically.” One logical and clear method of organizing research results is to provide them alongside the research questions—within each research question, present the type of data that addresses that research question.

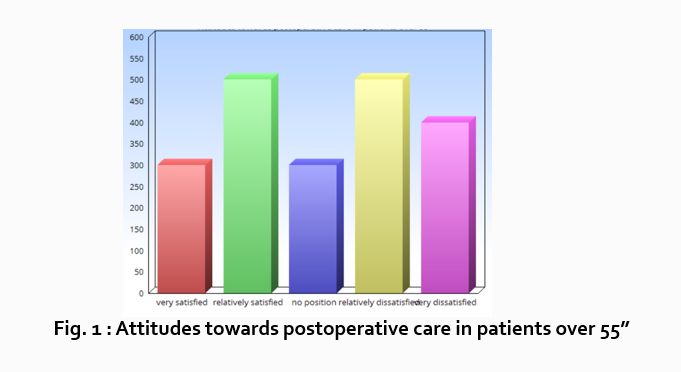

Let’s look at an example. Your research question is based on a survey among patients who were treated at a hospital and received postoperative care. Let’s say your first research question is:

“What do hospital patients over age 55 think about postoperative care?”

This can actually be represented as a heading within your Results section, though it might be presented as a statement rather than a question:

Attitudes towards postoperative care in patients over the age of 55

Now present the results that address this specific research question first. In this case, perhaps a table illustrating data from a survey. Likert items can be included in this example. Tables can also present standard deviations, probabilities, correlation matrices, etc.

Following this, present a content analysis, in words, of one end of the spectrum of the survey or data table. In our example case, start with the POSITIVE survey responses regarding postoperative care, using descriptive phrases. For example:

“Sixty-five percent of patients over 55 responded positively to the question “ Are you satisfied with your hospital’s postoperative care ?” (Fig. 2)

Include other results such as subcategory analyses. The amount of textual description used will depend on how much interpretation of tables and figures is necessary and how many examples the reader needs in order to understand the significance of your research findings.

Next, present a content analysis of another part of the spectrum of the same research question, perhaps the NEGATIVE or NEUTRAL responses to the survey. For instance:

“As Figure 1 shows, 15 out of 60 patients in Group A responded negatively to Question 2.”

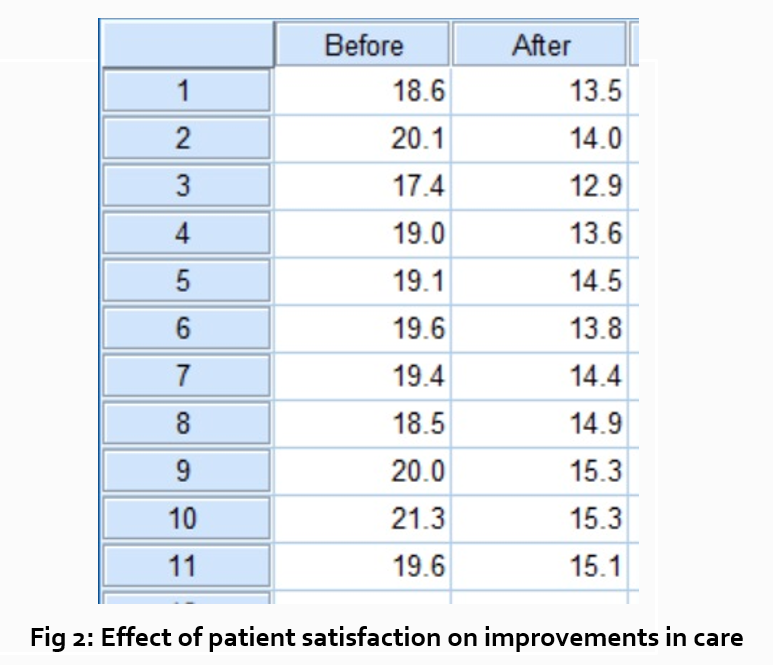

After you have assessed the data in one figure and explained it sufficiently, move on to your next research question. For example:

“How does patient satisfaction correspond to in-hospital improvements made to postoperative care?”

This kind of data may be presented through a figure or set of figures (for instance, a paired T-test table).

Explain the data you present, here in a table, with a concise content analysis:

“The p-value for the comparison between the before and after groups of patients was .03% (Fig. 2), indicating that the greater the dissatisfaction among patients, the more frequent the improvements that were made to postoperative care.”

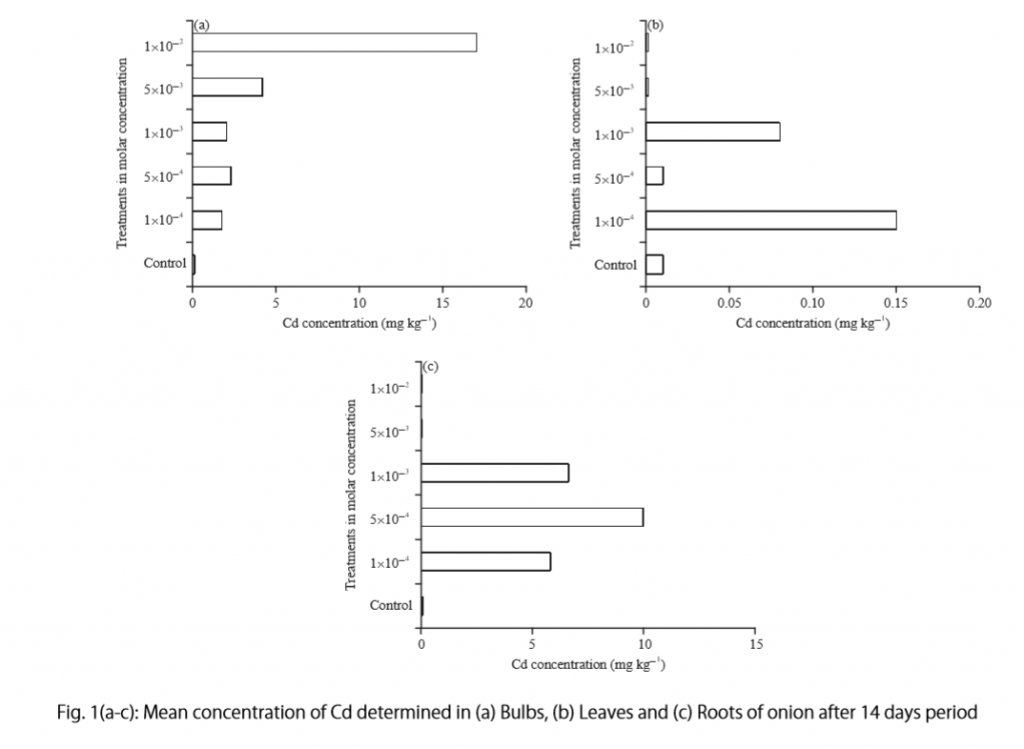

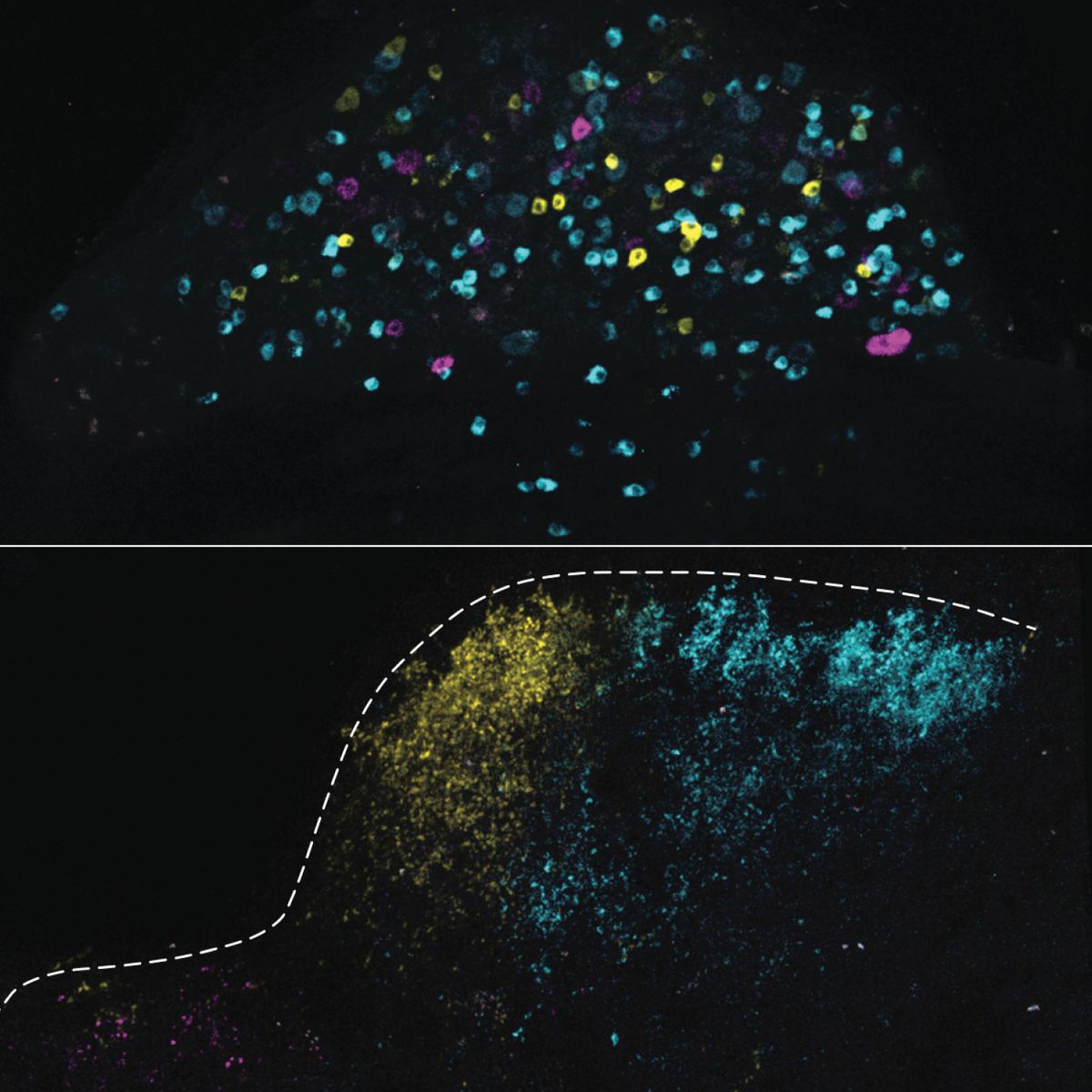

Let’s examine another example of a Results section from a study on plant tolerance to heavy metal stress . In the Introduction section, the aims of the study are presented as “determining the physiological and morphological responses of Allium cepa L. towards increased cadmium toxicity” and “evaluating its potential to accumulate the metal and its associated environmental consequences.” The Results section presents data showing how these aims are achieved in tables alongside a content analysis, beginning with an overview of the findings:

“Cadmium caused inhibition of root and leave elongation, with increasing effects at higher exposure doses (Fig. 1a-c).”

The figure containing this data is cited in parentheses. Note that this author has combined three graphs into one single figure. Separating the data into separate graphs focusing on specific aspects makes it easier for the reader to assess the findings, and consolidating this information into one figure saves space and makes it easy to locate the most relevant results.

Following this overall summary, the relevant data in the tables is broken down into greater detail in text form in the Results section.

- “Results on the bio-accumulation of cadmium were found to be the highest (17.5 mg kgG1) in the bulb, when the concentration of cadmium in the solution was 1×10G2 M and lowest (0.11 mg kgG1) in the leaves when the concentration was 1×10G3 M.”

Captioning and Referencing Tables and Figures

Tables and figures are central components of your Results section and you need to carefully think about the most effective way to use graphs and tables to present your findings . Therefore, it is crucial to know how to write strong figure captions and to refer to them within the text of the Results section.

The most important advice one can give here as well as throughout the paper is to check the requirements and standards of the journal to which you are submitting your work. Every journal has its own design and layout standards, which you can find in the author instructions on the target journal’s website. Perusing a journal’s published articles will also give you an idea of the proper number, size, and complexity of your figures.

Regardless of which format you use, the figures should be placed in the order they are referenced in the Results section and be as clear and easy to understand as possible. If there are multiple variables being considered (within one or more research questions), it can be a good idea to split these up into separate figures. Subsequently, these can be referenced and analyzed under separate headings and paragraphs in the text.

To create a caption, consider the research question being asked and change it into a phrase. For instance, if one question is “Which color did participants choose?”, the caption might be “Color choice by participant group.” Or in our last research paper example, where the question was “What is the concentration of cadmium in different parts of the onion after 14 days?” the caption reads:

“Fig. 1(a-c): Mean concentration of Cd determined in (a) bulbs, (b) leaves, and (c) roots of onions after a 14-day period.”

Steps for Composing the Results Section

Because each study is unique, there is no one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to designing a strategy for structuring and writing the section of a research paper where findings are presented. The content and layout of this section will be determined by the specific area of research, the design of the study and its particular methodologies, and the guidelines of the target journal and its editors. However, the following steps can be used to compose the results of most scientific research studies and are essential for researchers who are new to preparing a manuscript for publication or who need a reminder of how to construct the Results section.

Step 1 : Consult the guidelines or instructions that the target journal or publisher provides authors and read research papers it has published, especially those with similar topics, methods, or results to your study.

- The guidelines will generally outline specific requirements for the results or findings section, and the published articles will provide sound examples of successful approaches.

- Note length limitations on restrictions on content. For instance, while many journals require the Results and Discussion sections to be separate, others do not—qualitative research papers often include results and interpretations in the same section (“Results and Discussion”).

- Reading the aims and scope in the journal’s “ guide for authors ” section and understanding the interests of its readers will be invaluable in preparing to write the Results section.

Step 2 : Consider your research results in relation to the journal’s requirements and catalogue your results.

- Focus on experimental results and other findings that are especially relevant to your research questions and objectives and include them even if they are unexpected or do not support your ideas and hypotheses.

- Catalogue your findings—use subheadings to streamline and clarify your report. This will help you avoid excessive and peripheral details as you write and also help your reader understand and remember your findings. Create appendices that might interest specialists but prove too long or distracting for other readers.

- Decide how you will structure of your results. You might match the order of the research questions and hypotheses to your results, or you could arrange them according to the order presented in the Methods section. A chronological order or even a hierarchy of importance or meaningful grouping of main themes or categories might prove effective. Consider your audience, evidence, and most importantly, the objectives of your research when choosing a structure for presenting your findings.

Step 3 : Design figures and tables to present and illustrate your data.

- Tables and figures should be numbered according to the order in which they are mentioned in the main text of the paper.

- Information in figures should be relatively self-explanatory (with the aid of captions), and their design should include all definitions and other information necessary for readers to understand the findings without reading all of the text.

- Use tables and figures as a focal point to tell a clear and informative story about your research and avoid repeating information. But remember that while figures clarify and enhance the text, they cannot replace it.

Step 4 : Draft your Results section using the findings and figures you have organized.

- The goal is to communicate this complex information as clearly and precisely as possible; precise and compact phrases and sentences are most effective.

- In the opening paragraph of this section, restate your research questions or aims to focus the reader’s attention to what the results are trying to show. It is also a good idea to summarize key findings at the end of this section to create a logical transition to the interpretation and discussion that follows.

- Try to write in the past tense and the active voice to relay the findings since the research has already been done and the agent is usually clear. This will ensure that your explanations are also clear and logical.

- Make sure that any specialized terminology or abbreviation you have used here has been defined and clarified in the Introduction section .

Step 5 : Review your draft; edit and revise until it reports results exactly as you would like to have them reported to your readers.

- Double-check the accuracy and consistency of all the data, as well as all of the visual elements included.

- Read your draft aloud to catch language errors (grammar, spelling, and mechanics), awkward phrases, and missing transitions.

- Ensure that your results are presented in the best order to focus on objectives and prepare readers for interpretations, valuations, and recommendations in the Discussion section . Look back over the paper’s Introduction and background while anticipating the Discussion and Conclusion sections to ensure that the presentation of your results is consistent and effective.

- Consider seeking additional guidance on your paper. Find additional readers to look over your Results section and see if it can be improved in any way. Peers, professors, or qualified experts can provide valuable insights.

One excellent option is to use a professional English proofreading and editing service such as Wordvice, including our paper editing service . With hundreds of qualified editors from dozens of scientific fields, Wordvice has helped thousands of authors revise their manuscripts and get accepted into their target journals. Read more about the proofreading and editing process before proceeding with getting academic editing services and manuscript editing services for your manuscript.

As the representation of your study’s data output, the Results section presents the core information in your research paper. By writing with clarity and conciseness and by highlighting and explaining the crucial findings of their study, authors increase the impact and effectiveness of their research manuscripts.

For more articles and videos on writing your research manuscript, visit Wordvice’s Resources page.

Wordvice Resources

- How to Write a Research Paper Introduction

- Which Verb Tenses to Use in a Research Paper

- How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Paper Title

- Useful Phrases for Academic Writing

- Common Transition Terms in Academic Papers

- Active and Passive Voice in Research Papers

- 100+ Verbs That Will Make Your Research Writing Amazing

- Tips for Paraphrasing in Research Papers

How to Present Results in a Research Paper

- First Online: 01 October 2023

Cite this chapter

- Aparna Mukherjee 4 ,

- Gunjan Kumar 4 &

- Rakesh Lodha 5

632 Accesses

The results section is the core of a research manuscript where the study data and analyses are presented in an organized, uncluttered manner such that the reader can easily understand and interpret the findings. This section is completely factual; there is no place for opinions or explanations from the authors. The results should correspond to the objectives of the study in an orderly manner. Self-explanatory tables and figures add value to this section and make data presentation more convenient and appealing. The results presented in this section should have a link with both the preceding methods section and the following discussion section. A well-written, articulate results section lends clarity and credibility to the research paper and the study as a whole. This chapter provides an overview and important pointers to effective drafting of the results section in a research manuscript and also in theses.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Kallestinova ED (2011) How to write your first research paper. Yale J Biol Med 84(3):181–190

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

STROBE. STROBE. [cited 2022 Nov 10]. https://www.strobe-statement.org/

Consort—Welcome to the CONSORT Website. http://www.consort-statement.org/ . Accessed 10 Nov 2022

Korevaar DA, Cohen JF, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP et al (2016) Updating standards for reporting diagnostic accuracy: the development of STARD 2015. Res Integr Peer Rev 1(1):7

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al (2021) PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n160

Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups | EQUATOR Network. https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/coreq/ . Accessed 10 Nov 2022

Aggarwal R, Sahni P (2015) The results section. In: Aggarwal R, Sahni P (eds) Reporting and publishing research in the biomedical sciences, 1st edn. National Medical Journal of India, Delhi, pp 24–44

Google Scholar

Mukherjee A, Lodha R (2016) Writing the results. Indian Pediatr 53(5):409–415

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Lodha R, Randev S, Kabra SK (2016) Oral antibiotics for community acquired pneumonia with chest indrawing in children aged below five years: a systematic review. Indian Pediatr 53(6):489–495

Anderson C (2010) Presenting and evaluating qualitative research. Am J Pharm Educ 74(8):141

Roberts C, Kumar K, Finn G (2020) Navigating the qualitative manuscript writing process: some tips for authors and reviewers. BMC Med Educ 20:439

Bigby C (2015) Preparing manuscripts that report qualitative research: avoiding common pitfalls and illegitimate questions. Aust Soc Work 68(3):384–391

Article Google Scholar

Vincent BP, Kumar G, Parameswaran S, Kar SS (2019) Barriers and suggestions towards deceased organ donation in a government tertiary care teaching hospital: qualitative study using socio-ecological model framework. Indian J Transplant 13(3):194

McCormick JB, Hopkins MA (2021) Exploring public concerns for sharing and governance of personal health information: a focus group study. JAMIA Open 4(4):ooab098

Groenland -emeritus professor E. Employing the matrix method as a tool for the analysis of qualitative research data in the business domain. Rochester, NY; 2014. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2495330 . Accessed 10 Nov 2022

Download references

Acknowledgments

The book chapter is derived in part from our article “Mukherjee A, Lodha R. Writing the Results. Indian Pediatr. 2016 May 8;53(5):409-15.” We thank the Editor-in-Chief of the journal “Indian Pediatrics” for the permission for the same.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Clinical Studies, Trials and Projection Unit, Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India

Aparna Mukherjee & Gunjan Kumar

Department of Pediatrics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

Rakesh Lodha

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rakesh Lodha .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Retired Senior Expert Pharmacologist at the Office of Cardiology, Hematology, Endocrinology, and Nephrology, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA

Gowraganahalli Jagadeesh

Professor & Director, Research Training and Publications, The Office of Research and Development, Periyar Maniammai Institute of Science & Technology (Deemed to be University), Vallam, Tamil Nadu, India

Pitchai Balakumar

Division Cardiology & Nephrology, Office of Cardiology, Hematology, Endocrinology and Nephrology, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA

Fortunato Senatore

Ethics declarations

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Mukherjee, A., Kumar, G., Lodha, R. (2023). How to Present Results in a Research Paper. In: Jagadeesh, G., Balakumar, P., Senatore, F. (eds) The Quintessence of Basic and Clinical Research and Scientific Publishing. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1284-1_44

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1284-1_44

Published : 01 October 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-99-1283-4

Online ISBN : 978-981-99-1284-1

eBook Packages : Biomedical and Life Sciences Biomedical and Life Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Manuscript Preparation

How to write the results section of a research paper

- 3 minute read

- 57.4K views

Table of Contents

At its core, a research paper aims to fill a gap in the research on a given topic. As a result, the results section of the paper, which describes the key findings of the study, is often considered the core of the paper. This is the section that gets the most attention from reviewers, peers, students, and any news organization reporting on your findings. Writing a clear, concise, and logical results section is, therefore, one of the most important parts of preparing your manuscript.

Difference between results and discussion

Before delving into how to write the results section, it is important to first understand the difference between the results and discussion sections. The results section needs to detail the findings of the study. The aim of this section is not to draw connections between the different findings or to compare it to previous findings in literature—that is the purview of the discussion section. Unlike the discussion section, which can touch upon the hypothetical, the results section needs to focus on the purely factual. In some cases, it may even be preferable to club these two sections together into a single section. For example, while writing a review article, it can be worthwhile to club these two sections together, as the main results in this case are the conclusions that can be drawn from the literature.

Structure of the results section

Although the main purpose of the results section in a research paper is to report the findings, it is necessary to present an introduction and repeat the research question. This establishes a connection to the previous section of the paper and creates a smooth flow of information.

Next, the results section needs to communicate the findings of your research in a systematic manner. The section needs to be organized such that the primary research question is addressed first, then the secondary research questions. If the research addresses multiple questions, the results section must individually connect with each of the questions. This ensures clarity and minimizes confusion while reading.

Consider representing your results visually. For example, graphs, tables, and other figures can help illustrate the findings of your paper, especially if there is a large amount of data in the results.

Remember, an appealing results section can help peer reviewers better understand the merits of your research, thereby increasing your chances of publication.

Practical guidance for writing an effective results section for a research paper

- Always use simple and clear language. Avoid the use of uncertain or out-of-focus expressions.

- The findings of the study must be expressed in an objective and unbiased manner. While it is acceptable to correlate certain findings in the discussion section, it is best to avoid overinterpreting the results.

- If the research addresses more than one hypothesis, use sub-sections to describe the results. This prevents confusion and promotes understanding.

- Ensure that negative results are included in this section, even if they do not support the research hypothesis.

- Wherever possible, use illustrations like tables, figures, charts, or other visual representations to showcase the results of your research paper. Mention these illustrations in the text, but do not repeat the information that they convey.

- For statistical data, it is adequate to highlight the tests and explain their results. The initial or raw data should not be mentioned in the results section of a research paper.

The results section of a research paper is usually the most impactful section because it draws the greatest attention. Regardless of the subject of your research paper, a well-written results section is capable of generating interest in your research.

For detailed information and assistance on writing the results of a research paper, refer to Elsevier Author Services.

- Research Process

Writing a good review article

Why is data validation important in research?

You may also like.

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

The Essentials of Writing to Communicate Research in Medicine

Changing Lines: Sentence Patterns in Academic Writing

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

How to Write an Effective Results Section

Affiliation.

- 1 Rothman Orthopaedics Institute, Philadelphia, PA.

- PMID: 31145152

- DOI: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000845

Developing a well-written research paper is an important step in completing a scientific study. This paper is where the principle investigator and co-authors report the purpose, methods, findings, and conclusions of the study. A key element of writing a research paper is to clearly and objectively report the study's findings in the Results section. The Results section is where the authors inform the readers about the findings from the statistical analysis of the data collected to operationalize the study hypothesis, optimally adding novel information to the collective knowledge on the subject matter. By utilizing clear, concise, and well-organized writing techniques and visual aids in the reporting of the data, the author is able to construct a case for the research question at hand even without interpreting the data.

- Data Analysis

- Peer Review, Research*

- Publishing*

- Sample Size

Organizing Academic Research Papers: 7. The Results

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Executive Summary

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- How to Manage Group Projects

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Essays

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Acknowledgements

The results section of the research paper is where you report the findings of your study based upon the information gathered as a result of the methodology [or methodologies] you applied. The results section should simply state the findings, without bias or interpretation, and arranged in a logical sequence. The results section should always be written in the past tense. A section describing results [a.k.a., "findings"] is particularly necessary if your paper includes data generated from your own research.

Importance of a Good Results Section

When formulating the results section, it's important to remember that the results of a study do not prove anything . Research results can only confirm or reject the research problem underpinning your study. However, the act of articulating the results helps you to understand the problem from within, to break it into pieces, and to view the research problem from various perspectives.

The page length of this section is set by the amount and types of data to be reported . Be concise, using non-textual elements, such as figures and tables, if appropriate, to present results more effectively. In deciding what data to describe in your results section, you must clearly distinguish material that would normally be included in a research paper from any raw data or other material that could be included as an appendix. In general, raw data should not be included in the main text of your paper unless requested to do so by your professor.

Avoid providing data that is not critical to answering the research question . The background information you described in the introduction section should provide the reader with any additional context or explanation needed to understand the results. A good rule is to always re-read the background section of your paper after you have written up your results to ensure that the reader has enough context to understand the results [and, later, how you interpreted the results in the discussion section of your paper].

Bates College; Burton, Neil et al. Doing Your Education Research Project . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2008; Results . The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Structure and Approach

For most research paper formats, there are two ways of presenting and organizing the results .

- Present the results followed by a short explanation of the findings . For example, you may have noticed an unusual correlation between two variables during the analysis of your findings. It is correct to point this out in the results section. However, speculating as to why this correlation exists, and offering a hypothesis about what may be happening, belongs in the discussion section of your paper.

- Present a section and then discuss it, before presenting the next section then discussing it, and so on . This is more common in longer papers because it helps the reader to better understand each finding. In this model, it can be helpful to provide a brief conclusion in the results section that ties each of the findings together and links to the discussion.

NOTE: The discussion section should generally follow the same format chosen in presenting and organizing the results.

II. Content

In general, the content of your results section should include the following elements:

- An introductory context for understanding the results by restating the research problem that underpins the purpose of your study.

- A summary of your key findings arranged in a logical sequence that generally follows your methodology section.

- Inclusion of non-textual elements, such as, figures, charts, photos, maps, tables, etc. to further illustrate the findings, if appropriate.

- In the text, a systematic description of your results, highlighting for the reader observations that are most relevant to the topic under investigation [remember that not all results that emerge from the methodology that you used to gather the data may be relevant].

- Use of the past tense when refering to your results.

- The page length of your results section is guided by the amount and types of data to be reported. However, focus only on findings that are important and related to addressing the research problem.

Using Non-textual Elements

- Either place figures, tables, charts, etc. within the text of the result, or include them in the back of the report--do one or the other but never do both.

- In the text, refer to each non-textual element in numbered order [e.g., Table 1, Table 2; Chart 1, Chart 2; Map 1, Map 2].

- If you place non-textual elements at the end of the report, make sure they are clearly distinguished from any attached appendix materials, such as raw data.

- Regardless of placement, each non-textual element must be numbered consecutively and complete with caption [caption goes under the figure, table, chart, etc.]

- Each non-textual element must be titled, numbered consecutively, and complete with a heading [title with description goes above the figure, table, chart, etc.].

- In proofreading your results section, be sure that each non-textual element is sufficiently complete so that it could stand on its own, separate from the text.

III. Problems to Avoid

When writing the results section, avoid doing the following :

- Discussing or interpreting your results . Save all this for the next section of your paper, although where appropriate, you should compare or contrast specific results to those found in other studies [e.g., "Similar to Smith [1990], one of the findings of this study is the strong correlation between motivation and academic achievement...."].

- Reporting background information or attempting to explain your findings ; this should have been done in your Introduction section, but don't panic! Often the results of a study point to the need to provide additional background information or to explain the topic further, so don't think you did something wrong. Revise your introduction as needed.

- Ignoring negative results . If some of your results fail to support your hypothesis, do not ignore them. Document them, then state in your discussion section why you believe a negative result emerged from your study. Note that negative results, and how you handle them, often provides you with the opportunity to write a more engaging discussion section, therefore, don't be afraid to highlight them.

- Including raw data or intermediate calculations . Ask your professor if you need to include any raw data generated by your study, such as transcripts from interviews or data files. If raw data is to be included, place it in an appendix or set of appendices that are referred to in the text.

- Be as factual and concise as possible in reporting your findings . Do not use phrases that are vague or non-specific, such as, "appeared to be greater or lesser than..." or "demonstrates promising trends that...."

- Presenting the same data or repeating the same information more than once . If you feel the need to highlight something, you will have a chance to do that in the discussion section.

- Confusing figures with tables . Be sure to properly label any non-textual elements in your paper. If you are not sure, look up the term in a dictionary.