- futureofwork

The Office of the Future Is Greener, More Social, and Might Even Include Childcare

B efore the pandemic struck, Lucy Jefferson spent nearly £50 ($57) a day commuting from London, where she had moved in 2019, to Birmingham, England where she worked as a product manager at a large U.K. bank. Although it was Jefferson’s choice to relocate 125 miles away, she believed that the 5 a.m. starts and two-and-a-half journey weren’t necessary for her to do her job well. She says the workplace culture encouraged employees to always “look busy” in the office. ”Classic corporate culture.”

When a U.K.-wide COVID-19 lockdown in 2020 forced her employer’s staff to work remotely, Jefferson was able to save time and money working from home. But, frustrated by her employer’s reluctance to guarantee the flexible work model would continue, Jefferson handed in her notice in November 2020. Fast forward nearly two years, she works full time running her own e-commerce brand, Bare Kind, and all of her six employees work remotely. “I haven’t looked back, it’s been amazing,” she says, citing benefits to her mental health—and her bank balance.

Jefferson says her former colleagues tell her it’s now much more common to work from home and as a result, the Birmingham office has lost its former buzz, with some floors no longer in use. This shift in office culture is in no way unique—offices in major U.S. cities are less than half as busy as they used to be, according to data from security provider Kastle Systems. The pandemic forced many companies to shift online, and some employees realized they preferred it. In the U.S., Australia, France, Germany, Japan, and the U.K, 18% of workers aren’t going into the office at all, according to a survey published in July by Future Forum, while patterns of hybrid working have become the norm for nearly half of the workforce.

Meanwhile, business leaders have been twisting themselves in knots over the return of in-person work, which some argue promotes more productivity and collaboration. At times this has created tensions .

Read More: Dropbox Tossed Out the Workplace Rulebook. Here’s How That’s Working

The clash in priorities between employers and workers has come amid record resignations across the workforce around the world. In the U.S., around 4 million workers have been quitting their jobs every month since April 2021, with many citing workplace inflexibility as a key factor. But being in the office could make a difference to their careers. In response to a survey published last month by workplace platform Envoy, 96% of U.S. executives said they were more likely to notice the contribution of employees in the office.

The conundrum for businesses has been getting workers to come back. Some industry leaders are viewing the pandemic disruption and shifting labor market as an opportunity to reconfigure workspaces in a way that prioritizes flexibility, wellbeing, and sustainability—and actually entices employees to travel in. The office may never dominate the world of white-collar work in the way it did pre-pandemic, but innovative designers and bosses are hoping it will add greater value to both their businesses and employees’ lives.

Making workplaces “commute-worthy”

While the new ways of working during the pandemic came as a shock to many businesses, global music streaming platform, Spotify, was well ahead of the curve. Just a month before the U.K. first went into lockdown in March 2020, Spotify unveiled its new London headquarters that would house hundreds of freshly hired employees and one of the company’s largest R&D hubs. Gone were the sea of desks typical of traditional office spaces. Instead, large booths, plush lounge spaces, production studios, and dedicated “listening rooms” gave the space, a “social club” feel, says Sonya Simmonds, Spotify’s global head of workspace design. Although employees initially couldn’t benefit from the new space—situated inside the Grade II listed Art Deco Adelphi Building in the heart of London—during the early months of the pandemic, the building was primed to cater to the blend of remote and in-person work on their return.

“We all felt disappointed not to use the new office and share the new spaces [during lockdown], particularly the stage and listening rooms with artists,” says Simmonds. As workers returned to the offices, it was set up to better suit their needs. Spaces dedicated to wellness provided a welcome getaway for workers dealing with the stresses of the pandemic, Simmonds says. “When we were allowed to return we really appreciated the wellbeing rooms.”

The idea behind the space was “very much based on where we wanted to go in the future,” Simmonds says. In February 2021, Spotify announced a work from anywhere policy, a transition that she says was accelerated, not triggered, by the pandemic. Yet, the company found that staff were still choosing to travel to the London office—the huge variety of spaces within the building offered even greater flexibility than employees’ own homes. In a post-pandemic era, workplaces must be “commute-worthy” for remote workers, says Shane Kelly, principal director at London-based architecture firm TP Bennett, which designed Spotify’s London office. “It’s about creating buildings that offer really collaborative experiences, focused on community and amenity, that you don’t get when you’re engaging remotely,” he says. Following the success of the London HQ, Spotify rolled out the design concept across its global locations.

Read More: How to Ask Your Employer if You Can Work Remotely Permanently

Swiss furniture brand Vitra took the concept of work flexibility one step further, when in spring 2021 it filled its headquarters in Birsfelden, Switzerland with customizable fittings that allow for multiple office configurations. The company’s new range, dubbed “Club Office,” includes modular sofa systems, flexible partitions, and foldable desks that fit together like a puzzle, allowing teams to tailor the work set-up to a variety of needs, moods, and even locations. By letting employees use their own office as a “laboratory” for new design concepts, Club Office fostered flexibility within Vitra’s workforce, says the company’s chief executive, Nora Fehlbaum. “Environments shape our thoughts and feelings,” says Fehlbaum. “This environment signals to stay on your toes, be ready to move.”

Fehlbaum hopes that Vitra’s products will make all workers feel connected to their office environments, even as their companies downsize or shift to co-working spaces. “The Club is the physical environment where a common mission and sense of belonging comes to life,” she says.

Blending the office with the home

Months of isolation during lockdowns around the world made workers appreciate the feeling of belonging to a team and connecting with colleagues—even when working remotely or from their homes. According to recent findings from the WFH research project , a monthly survey run jointly by the University of Chicago, Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Stanford University, the average professional spends more than 40% of their working day interacting with others. With this in mind, Edouard Bettencourt and Malik Lemseffer, founders of French-Moroccan architecture firm Studio BELEM, have focused on designing a space where workers could connect and interact with others within the comfort of their own homes. Their aula modula apartment block design—a Tetris-like system of cube-shaped units with sliding wall panels—incorporates the collaborative elements of an office environment in a residential setting. While the block hasn’t been built yet, the firm says it is in talks with various developers.

With each block arranged around a sunny inner courtyard, the idea is that inhabitants would be encouraged to develop a sense of neighborly community, even while they work from home. “If you work remotely and just stay in your own flat or office all day, you’re going to go crazy not seeing anyone,” says Lemseffer. Creative shared spaces in the building, including shared terraces, co-working rooms, and roof tops, allow residents to network, brainstorm, and celebrate professional milestones—”all the things that can be a little bit harder to do remotely,” he says. At the same time, the architects were keen to contain the intimate living spaces and office units in different rings of the building, to allow residents to switch off from their work as they cross the physical boundary.

The blurring of the home and work environment precipitated by the pandemic forced many businesses to accommodate the unique personal circumstances of each employee. One such accommodation was caregiving responsibilities, as workers had to juggle educating their children while schools were shut or caring for elderly or sick relatives. Research published in June by the Society for Human Research Management found that, even as the pandemic subsides, workers place increasing value on jobs that offer the flexibility to care for family members.

Read More: The Dream of an ‘Internet Country’ That Would Let You Work From Anywhere

Entrepreneur Keltse Bilbao recognized this need before the pandemic when, after relocating to Los Angeles with her husband, she struggled to find a space where she could work on her own projects while being close to her daughter. In 2018, she founded Big and Tiny, a daycare service that provides on-site co-working spaces for parents—one of the first to do so in the U.S. “As a parent, what I wanted was the option to choose,” Bilbao says. “I could spend all day working, or I could have a break and be close to my child.” Big and Tiny has three studios in the U.S.—two in Santa Monica and one in Battery Park, New York City. They combine soundproof study rooms and phone booths, but also common spaces for working parents to socialize and relax.

While the business took a financial hit due to the pandemic—forcing it to shutter a center in Silver Lake, Los Angeles—the shift to remote working meant that more parents needed the service when lockdown restrictions were lifted. The increased demand for family-friendly work spaces led to partnerships with co-working office provider Second Home and mall and office complex Brookfield Place in New York City, with Big and Tiny providing on-site childcare. “These companies were having issues getting their customers back,” says Bilbao, adding that employers partnering with Big and Tiny to offer these workspaces to employees have been able to “differentiate themselves” from rivals whose offices didn’t cater to the demands of modern life.

Sustainability and wellbeing

Months of mask mandates, social distancing and enhanced hygiene practices shifted many people’s understanding of what makes a healthy environment. As poorly ventilated office buildings became potential public health hazards, citizens found respite in outdoor spaces. Simultaneously, the pandemic appears to have heightened public awareness of the climate crisis, according to a survey by Boston Consulting Group, as the effect of human behavior on the natural world, and the risks to humankind, have become more apparent. This shift inspired a new wave of office design that prioritized the wellbeing of both employees and the external environment.

Read More: In Some Workplaces, It’s Now OK Not to Be OK

Turkish architecture practice Salon Alper Derinboğaz made the learnings from the pandemic central to the design of Ecotone, an innovation center at Yıldız Technical University in Istanbul. When construction is completed in late 2023, the transitional space between teaching facilities and a professional academy will be “pandemic resistant,” says the architecture firm’s founder, Alper Derinboğaz, referring to the building’s partially open air design. Istanbul’s mild Mediterranean climate has allowed Derinboğaz to permeate a series of open co-working spaces with outdoor walkways, creating the kind of passive natural ventilation system that the World Health Organization says reduces the transmission risk of airborne viruses. Ecotone’s geothermal heating and cooling system is low emission, while the self-supporting structure—featuring columns resembling stalagmites and stalactites in caves—removes the need to lay intrusive foundations in the land. Fluid, glass-paneled walls and interior foliage allows for greater connection between workers inside the building and nature.

Developing innovative approaches to reducing the office building’s carbon footprint was a priority for Derinboğaz, who notes that the construction industry produces nearly 40% of global carbon emissions. “As architects we really need to find a new way of doing things,” he says. “That’s why we wanted the university’s innovation center to be innovative in its design.”

When it came to choosing architects for an addition to its Geneva campus , the United Nations (U.N.) says it chose London-based firm Skidmore Owings & Merrill (SOM) and Swiss studio Burckhardt+Partner. The architects took an innovative approach designing the 250,000 square foot office space. Completed in November 2021, the building was constructed on the historic Palais des Nations complex of buildings overlooking Lake Geneva, the U.N.’s second largest site after its New York headquarters. Water from the lake is used and recycled to heat and cool the building, eliminating the need for air conditioning units that are expensive to run and harmful to the environment .

According to Kent Jackson, SOM’s lead designer on the project, which the firm said was for a “non-profit humanitarian organization in Geneva,” the impressive surroundings gave the architects a unique opportunity to enhance the building’s design. “We wanted to give every employee [working in the office] a 360 degree view around the natural setting,” he says—floor-to-ceiling windows stand in place of walls. “Who couldn’t be inspired in their work looking at the hillsides, parkland, water, and mountains?”

For many of the companies pursuing new approaches to workspaces, that is the ultimate goal: creating a space to inspire and motivate employees to produce their most innovative work. In an age of increasing flexibility and less emphasis on geographical location, the office space must benefit its inhabitants as much as it does the business. “It’s about going through the whole journey of the build and design process together,” says Spotify’s Simmonds. “Coming out the other end, our staff feel they really have ownership over their office.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- The New Face of Doctor Who

- Putin’s Enemies Are Struggling to Unite

- Women Say They Were Pressured Into Long-Term Birth Control

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- Boredom Makes Us Human

- John Mulaney Has What Late Night Needs

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

9 Trends That Will Shape Work in 2024 and Beyond

- Emily Rose McRae,

- Peter Aykens,

- Kaelyn Lowmaster,

- Jonah Shepp

Looking ahead at a year of continued disruption, employers who successfully navigate these trends will be able to create a competitive advantage.

In 2023, organizations continued to face significant challenges, from inflation to geopolitical turmoil to controversy over DEI and return-to-work policies — and 2024 promises more disruption. Gartner researchers have identified nine key trends, from new and creative employee benefits to the collapse of traditional career paths, that will impact work this year. Employers who successfully navigate these will retain top talent and secure a competitive advantage for themselves.

In 2023, business leaders and organizations continued to contend with major shifts affecting the workplace, including the pressure of inflation on both employer and employee budgets, the emergence of generative AI (GenAI) , geopolitical turmoil, a series of high-profile labor strikes , increased tension over return-to-office (RTO) mandates , a shifting legal and societal landscape for DEI initiatives, the increased impact of climate change , and more.

- Emily Rose McRae is a senior director analyst covering the future of work and workforce transformation, and she leads the talent research initiative for executive leaders. Emily Rose works across all issues related to the future of work, including emerging technologies and their impact on work and the workforce, new employment models, and creating an enterprise-wide future of work strategy.

- Peter Aykens is a distinguished vice president and chief of research for the Gartner HR practice. He is responsible for setting the practice’s research agenda and strategy to address the mission critical priorities of HR leaders, including leadership, talent management, recruiting, diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), total rewards, learning and development, and HR tech.

- Kaelyn Lowmaster is a director of research in the Gartner HR Practice. She focuses on the Future of Work including all areas of future strategy development, with a core emphasis on the impact of emerging technology on work and the workforce.

- Jonah Shepp is a senior principal, research in the Gartner HR practice. He edits the Gartner HR Leaders Monthly journal, covering HR best practices on topics ranging from talent acquisition and leadership to total rewards and the future of work. An accomplished writer and editor, his work has appeared in numerous publications, including New York Magazine , Politico Magazine , GQ , and Slate .

Partner Center

- Book a Speaker

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Vivamus convallis sem tellus, vitae egestas felis vestibule ut.

Error message details.

Reuse Permissions

Request permission to republish or redistribute SHRM content and materials.

What Will the Workplace Look Like in 2025?

The shift to remote work will be among the biggest business trends in the coming years, though it won't be the only lingering effect from the pandemic.

Before the pandemic, General Motors Co. was moving toward giving employees more flexible schedules. However, the coronavirus outbreak threw that effort into overdrive.

In November, the Detroit-based automaker announced it was hiring 3,000 technical employees, the majority of whom will work remotely. The company is offering more full-remote experiences than ever before. Leadership’s confidence to take such a bold step stems from the performance of the teams that are working remotely because of the COVID‑19 pandemic.

“Our workforce was able to meet the new challenges [while working from home] without missing a beat,” says Adam Yeloushan, GM’s human resources executive for global engineering. “We can [work remotely] well. We can do it effectively.”

‘The role of the office has changed. People aren’t going to go back to five days a week. Offices are going to be hubs of innovation and social interaction.’ - Bhushan Sethi

Working from home became a necessary stopgap measure to keep companies running amid the COVID‑19 crisis, but it has evolved into a new business paradigm. Many employees praise their newfound flexibility, while company leaders continue to manage their businesses effectively—and less expensively—even when employees aren’t in the office. Employers also welcome the broader pool of potential job candidates, since remote employees can live anywhere.

“The role of the office has changed,” says Bhushan Sethi, joint global leader, people and organization, at global consulting firm PwC. “People aren’t going to go back to five days a week. Offices are going to be hubs of innovation and social interaction.”

That shift will be among the biggest business trends in the coming years, though it won’t be the only lingering effect from the pandemic. The virus pushed companies to grapple with health and safety issues like they never had before. Not only have they reconfigured workplaces to prevent infection, they have also grappled with how to address the pandemic’s toll on employees’ physical and mental health. Those efforts will continue to better prepare companies for other emergencies.

The killings of George Floyd and others while in police custody and the ensuing protests is the other development from this year that will reverberate through the business community for the foreseeable future. Floyd’s death laid bare the overall inequities in the U.S. and prompted soul-searching in the business sector. Companies have promised to increase diversity within their ranks—especially among executives—and the fulfilling of those pledges is now expected to top corporate agendas.

While the combination of the pandemic and social unrest have led to major new trends, the upheaval has also pushed other long-standing issues, such as environmental concerns, worker activism and rapidly changing technology, to the forefront of C-suite executives’ minds.

These are six major trends that will ripple through companies until at least 2025:

1. More employees will work from home.

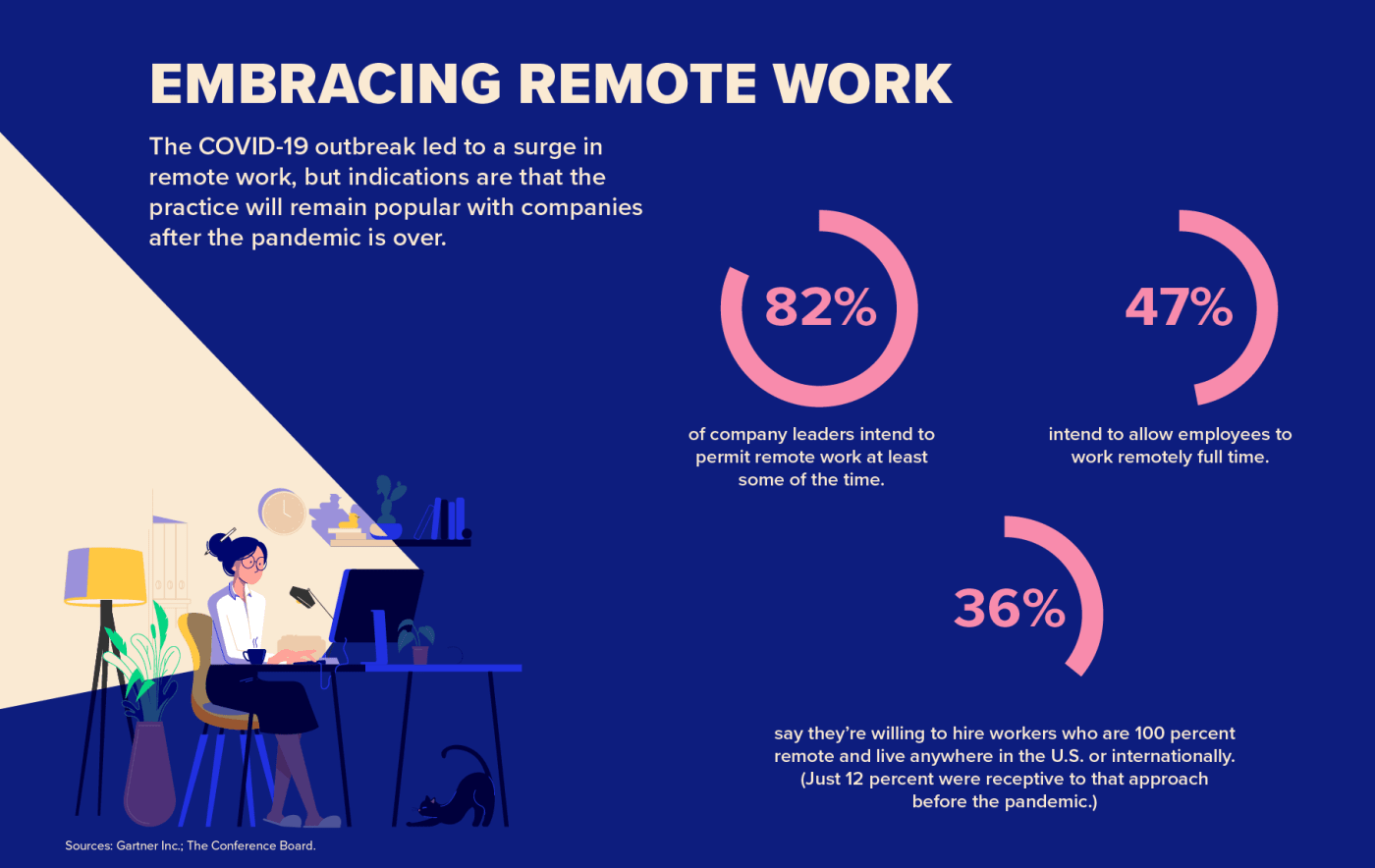

The world should start returning to “normal” in 2021 as the COVID‑19 vaccine is distributed. The new normal won’t include nearly as many office workers commuting daily to a company facility. A large majority—82 percent—of executives say they intend to let employees work remotely at least part of the time, according to a survey by Gartner Inc., a Stamford, Conn.-based research and advisory firm. Nearly half—47 percent—say they will allow employees to work remotely full time.

Meanwhile, 36 percent of companies say they’re willing to hire workers who are 100 percent remote and live anywhere in the U.S. or internationally. Just 12 percent were receptive to that idea before the pandemic, according to The Conference Board, a New York City-based research nonprofit.

Reconfiguring the office for this new scenario is an interesting dilemma for companies. Executives expect that individuals will want more personal space even with a COVID‑19 vaccine available, though businesses will likely reduce their real estate holdings if employees aren’t in the workplace full time. Seventy percent of companies expect to shrink their real estate footprint in the next two years, according to CoreNet Global, a nonprofit organization made up of corporate real estate executives.

Design experts predict that more companies will adopt what is known as “hoteling.” That means employees no longer have assigned seating but locate where there’s space available for the type of tasks they’re working on. Some areas will be earmarked for quiet work while others will be designated for group discussions, for example.

“The workspace needs to be more agile,” says Jamie Feuerborn, director of workplace strategy at New York City-based design firm Ted Moudis Associates. She adds that companies are looking at flexible furnishings, such as desks that can be easily moved and have adjustable privacy panels.

Remote working is not for every company, nor is it without risks. Some jobs require people to be onsite, and surveys have shown that some individuals have had trouble achieving work/life balance while working from home. There’s also a fear that corporate culture and innovation will suffer if co-workers aren’t in the same space.

Sixty-five percent of employers say it has been challenging to maintain morale, and more than one-third say they’re facing difficulties with company culture and worker productivity, according to a survey by the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). Three years ago, IBM, a pioneer of remote work, called most of its off-campus workforce back to the office to improve innovation.

Now it seems that companies are more aware of the pitfalls of a remote workforce and seek to approach remote work with an intention that was lacking in the rushed response to the pandemic. Over the summer, Facebook advertised for a director of remote work, whose responsibilities would include developing strategies and tools to keep the business running no matter where employees are located, and coaching managers on how to adjust to the new remote-work structure. Facebook co-founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg said 50 percent of the company could be working from home within the next five to 10 years.

GM’s Yeloushan says the company can adjust to any issues or problems. “All because we’re doing some things today doesn’t mean we’ll be doing the same tomorrow.”

2. Companies will invest heavily in health, hygiene and safety.

COVID-19 turned a spotlight on worker health and safety in all industries—not just those known for being dangerous—as even people who sat at computers all day landed in intensive care units after contracting the coronavirus. Employees who have returned to their workplaces wear masks, sanitize surfaces and social distance, and some even submit to temperature checks. Those measures are likely to transform into workplace testing protocols, state-of-the-art ventilation systems, and high-tech detection and disinfectant tools.

“We’re assured of having another [pandemic],” says Cristina Banks, director of the Interdisciplinary Center for Healthy Workplaces at the University of California Berkeley School of Public Health. “Our mobility around the world is at the peak, and there’s no stopping the spread. We need to plan for that.”

The planning is already happening. A vast majority of business executives—83 percent—say they expect to hire more people for health and safety roles within the next two years, according to a report by consulting firm McKinsey & Co. It’s the sector that’s predicted to have the most hiring.

‘We’re assured of having another [pandemic]. Our mobility around the world is at the peak, and there’s no stopping the spread. We need to plan for that.’ Cristina Banks

Concerns extend beyond employees’ physical health. The pandemic, the recession and social unrest have caused increased anxiety, depression and stress in the general population. Employers had been increasing their mental health benefits before the COVID‑19 outbreak and are now stepping up even more. Nearly three-quarters (72 percent) of companies plan on improving their mental health offerings next year, according to a survey by PwC.

Many companies have heavily promoted their employee assistance programs, increased the number of paid sessions with mental health counselors for employees while waiving or lowering co-payments, and added more digital tools to help people calm and focus themselves. Some organizations are training managers to spot signs of distress.

“We know that having a strong mental health strategy will be a critical priority,” says Abinue Fortingo, a health management director at Willis Towers Watson. He says employers are combing through claims data to understand how to put together the best plan design.

3. Companies will continue striving to increase diversity, equity and inclusion.

The $8 billion that McKinsey & Co. says companies spend annually on diversity, equity and inclusion programs is not money well spent. White men still occupy 66 percent of C-suite positions and 59 percent of senior vice president posts, according to a study by McKinsey and LeanIn.Org. White women hold the second largest share of such positions, though they lag significantly behind their male counterparts, filling only 19 percent of C-suite jobs and 23 percent of senior vice president spots. Men of color account for 12 percent and 13 percent of such roles, respectively, while women of color hold only 3 percent and 5 percent, respectively.

Such statistics entered the public consciousness in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death, putting more pressure than ever on companies to diversify their ranks.

Some companies are opting to initiate conversations that encourage their employees to talk openly about issues such as racism, sexism, bias and prejudice. Yeloushan says hiring more remote workers will allow GM to tap into a much wider talent pool that will help diversity the workforce.

Meanwhile, in October, Seattle-based coffee company Starbucks said part of its executives’ pay would be based on their ability to build inclusive and diverse teams.

It’s too soon to say if such efforts will spark real change, though there are some positive signs. Eric Ellis, president and chief executive officer of Integrity Development Corp., a West Chester, Ohio-based consulting firm, says the strategy sessions he holds about improving diversity, equity and inclusion now include more CEOs and not just human resource executives. “CEOs are more interested now and putting more pressure on their organizations to change,” he says.

4. Workers will demand better treatment for themselves and their communities from their employers.

Thousands of workers at companies such as McDonald’s, Target and Amazon, as well as at numerous hospitals, staged strikes this year to protest unsafe working conditions amid the pandemic.

Such actions followed two years of employee demonstrations over various issues—though not pay—signaling that employees were expecting more from their employers. Last year, for example, Amazon employees walked out over the company’s climate policies, while Wayfair workers left company facilities over sales of furniture to immigrant detention centers in the U.S.

Overall, work stoppages numbered 25 last year, more than triple the amount in 2017, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

‘People are looking for alternate ways to communicate, and virtual reality is a good fit. It allows a level of interaction that goes beyond voice and video. It’s much more personal.’ T.J. Vitolo

The activity hasn’t reversed the years-long decline in union membership, although that could change. President-elect Biden ran on a pro-labor platform that could translate into the removal of some obstacles to unionization implemented by the Trump administration. Even without more unions, workers—especially younger ones—increasingly expect their employers to take an active role in addressing society’s problems.

“We’re seeing companies have more of a social conscience,” Ellis says. “I think that’s part of the value system of the up-and-coming generation.”

The idea is taking hold. In 2019, the Business Roundtable released a new definition of a corporation and outlined a company’s purpose as extending beyond making profits to considering how its actions affect all stakeholders, including employees, customers and suppliers.

5. Organizations will re-examine how they impact the environment.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a brutal reminder of the ravages of climate change.

The novel coronavirus evolved from a virus common in bats, though it’s unclear how it passed to humans. Experts say deforestation, which pushes animals farther out of their natural habitats, could have been a factor, as it puts animals closer to people. What is known is that climate change is making the death toll worse. A Harvard University study found that a small increase in exposure to air pollution leads to a large increase in COVID‑19-related death rates.

“Businesses found themselves unprepared for COVID,” says Rachel Hodgdon, president of the New York City-based International WELL Building Institute, which has programs to create buildings, interiors and communities that promote health and wellness. The institute recently started a COVID‑19 certification program to help all types of facilities protect against the disease.

To make matters worse, businesses are being buffeted simultaneously by disasters caused by climate change. This year, fires raged on the U.S. West Coast, and hurricanes hit many states, all while the country was fighting the virus.

Having more employees work from home will help the environment as fewer people commute and office buildings use less energy. More action is required, however, and experts expect more companies to hire chief sustainability officers.

Many companies already have such roles, though some practitioners only ensure that their organizations meet basic laws and standards. That won’t cut it anymore, thanks to the greater emphasis on health and the environment. Going forward, chief sustainability officers will be expected to look at their company’s environmental impact on workers, suppliers, customers and communities. “That will all be tied back to the business strategy,” says Anthony Abbatiello, global head of leadership and succession consulting at Russell Reynolds, a New York City-based executive search and consulting firm.

6. Technology’s rapid transformation will continue, forcing companies to rethink how to integrate people with machines.

The pandemic forced employers to adopt more digital and automated solutions practically overnight, as organizations sought to severely limit—or end—human interaction to stop the spread of the coronavirus.

The McKinsey study found that 85 percent of companies accelerated the digitization of their businesses, while 67 percent sped up their use of automation and artificial intelligence. Nearly 70 percent of executives say they plan to hire more people for automation roles, while 45 percent expect to increase hiring for positions involving digital learning and agile working.

One area that’s expected to grow enormously is companies’ use of virtual and augmented reality, as fewer employees work at the same location. Companies are already using these technologies for training, telemedicine and team-building events.

“People are looking for alternate ways to communicate, and virtual reality is a good fit,” says T.J. Vitolo, director and head of XR Labs, a division of New York City-based Verizon Communications Inc. “It allows a level of interaction that goes beyond voice and video. It’s much more personal.”

Robot use boomed during the pandemic, as companies sought to reduce workers’ exposure to the coronavirus. For example, San Diego-based Brain Corp. said use of its robots by U.S. retailers surged 24 percent in the second quarter of 2020 compared to the year before, as companies used the machines for tasks such as cleaning stores.

The increased use of technology will eliminate jobs. That means companies will need to reskill employees to prepare them for new tasks and responsibilities.

“I think reskilling will be the foundation of the new economy,” says Ravin Jesuthasan, a managing director at Willis Towers Watson. “What it’s going to require is a clear understanding of how to get the optimal combination of people and machines.”

Related Articles

A 4-Day Workweek? AI-Fueled Efficiencies Could Make It Happen

The proliferation of artificial intelligence in the workplace, and the ensuing expected increase in productivity and efficiency, could help usher in the four-day workweek, some experts predict.

How One Company Uses Digital Tools to Boost Employee Well-Being

Learn how Marsh McLennan successfully boosts staff well-being with digital tools, improving productivity and work satisfaction for more than 20,000 employees.

Employers Want New Grads with AI Experience, Knowledge

A vast majority of U.S. professionals say students entering the workforce should have experience using AI and be prepared to use it in the workplace, and they expect higher education to play a critical role in that preparation.

HR Daily Newsletter

New, trends and analysis, as well as breaking news alerts, to help HR professionals do their jobs better each business day.

Success title

Success caption

- The Workplace of the Future

Featured in:

© pexel | photos.oliur.com

This article invites you to peer into the future and explore the future workplace , what changes are to be realized in workplaces of the future , an objective consideration of the implications of those changes, and whether we should invite the workplaces of the future with open arms or apprehension .

As time progresses and as we move forward into the unknown, the workforce environment as we know it evolves , just like every other aspect of our lives. So, what does this mean for your organization’s future? What do you think the pacesetters of business in the future will look like? How will they be organized? What kind of machinery will they employ?

We face a future that is driven by evolutionary and revolutionary forces, for example; the invention of the internet recently hit the business world by storm and quickly transformed how business is conducted for good. What other megatrend will be next? How will it reshape our world? Have you considered the potential implications of these sort of changes?

The workplace of the future is going to be extremely different from workplaces as we know them now; workplace transformation does not simply imply the structures of our offices but more specifically how people work.

For example, just a few decades ago, there were very few individuals who worked to the ages of 60-70 but as time progressed, people held on just a little longer to their jobs. We can, therefore, assume that this trend may be stretched further in the future. In addition, as the world continues to become a ‘global village’, businesses have to reconsider their workplace. This is because of the rising demand in more skilled, more flexible, and more dependable employees.

[slideshare id=34096669&doc=whatwillthefutureworkplacelooklikeaspirees14-140429151534-phpapp01&w=710&h=400]

Because of the diversification of employees in the business world today, some businesses have begun to redefine what it means to be considered and employee, what it means to be contracted for a job, and how individuals are compensated by the business. For example, some businesses have started to recognize freelancers as part of their employees.

The future is working towards introduction of new and undocumented elements into workplaces as we know them. The next section attempts to look as far ahead as possible in order to give us an image on what the future workplace will be like.

THE WORKPLACE OF THE FUTURE

Workplace structures.

Set aside rigid corporate hierarchies and imagine free-flowing career paths and ideas. Search the website right now or go to your local library and you will realize just how many books have been written on climbing the corporate ladder. In the future, such books may become outmoded and quite possibly just antique possessions rather than useful tools of information.

One of the changes already affecting workplaces today is the gradual collapse of corporate ladders, where the structure is designed to ensure that only the most loyal employees climb higher and higher in the hierarchy, a promotion at a time. The corporate ladder can be traced all the way back to the industrial revolution, when businesses were structured on economies of scale and rigid hierarchies.

But we are no longer in that era; we are in the digital age and the workforce is as diverse as it has ever been. In fact, it is a surprise that this sort of workplace structure has survived this far in the digital era. This work place diversity coupled with rapid advances in technology has inspired the need for a more flexible work environment. For businesses of the future to maintain a productive workforce, it may be necessary to trim several layers off their hierarchies and adopt more horizontal systems. This will facilitate a better flow of ideas and ease communication between extremely diverse workforce personnel.

Interested in how Adidas sees the future of the workplace ? Watch this video.

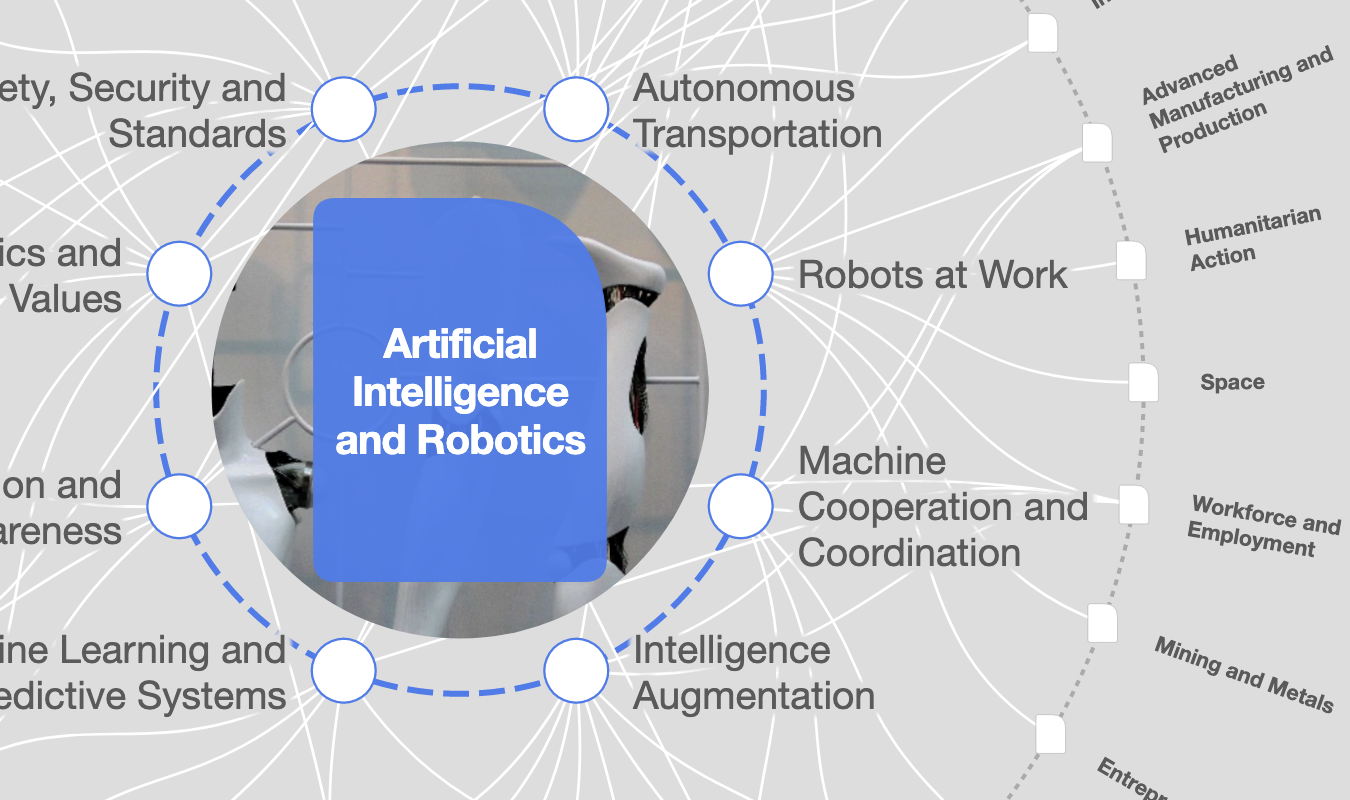

Artificial intelligence

I know it sound like science fiction but the machine is coming. As technology advances, automation of very many functions normally performed by humans has become prevalent. Artificial intelligence is an anticipated reality in the future and it will undoubtedly affect the nature of our workplaces. We are slowly but surely accepting the takeover of machines.

As awesome, progressive, or convenient these innovations appear, they can also be very disadvantageous. These innovations can nullify entire professions and if predictions are correct, the automation of our workplaces in the near future is expected to increase at an unprecedented rate. With such an expeditious rate of growth, artificial intelligence in the workplace might become a reality sooner than you think and its impact may be just as massive as the internet’s.

There is, however, a more positive outlook of this anticipated change. As opposed to assuming that the machines are taking jobs from human beings, we can choose to look at it as being freed in order to perform other more engaging functions. Over the past decade, machines have learnt how to organize immense volumes of data in order to produce actionable information for businesses. The ability to organize and interpret this kind of complex data enables the performance of activities that could not be previously done by businesses. For example, the pinpoint prediction of consumer persona and needs.

However, note that manual tasks are going to be the most affected areas as machines grow to perform more tasks. Robots in manufacturing industries are becoming increasingly mobile, adaptable, and affordable . Additionally, the performance of tasks such as digging, constriction, and basically, activities that would require hand eye coordination are being replaced by these low-cost, efficient, machines

Learn about a new mode of structuring the workplace called holocracy which includes new government principles.

In the future, businesses will be able to monitor employees in a more intimate way. Since the performance of employees directly translates to the performance of the business, workplaces may require employees to wear devices that track their movements at work. This, of course, is not for invasive purposes but it is to enable management to monitor how an employee is feeling, to observe that employees levels of stress, whether they are tired, or are deprived of sleep.

In fact, similar tracking devices are already in use. For example, cheap GPS technologies have already become widespread especially in the field of taxis and courier service providers. Additionally, earpieces are being used to convey instructions to employees in more manual and volatile workplace settings such as manufacturing plants.

Workplace monitoring of employee health is the more unexplored area. This, however, may change in the near future. With the rise in popularity of wearable devices such as Jawbone , which tracks the owner’s exercise, calorie intake, sleep pattern, as well as other health-related aspects, monitoring the state of employees might take a very different turn in the workplaces of the future. According to the research company Gartner, over 2,000 companies around the world offered their employees fitness trackers in the year 2013. It is, therefore, possible that the way monitoring is done in workplaces is already taking a turn.

One might argue that this level of monitoring is unnecessary and a borderline invasion of privacy. However, it is undeniable that the performance at work of any employee is not only influenced by factors found in the workplace; it goes beyond that. There is a direct link between a person’s sleep pattern , exercise routine, stress, and anxiety levels outside of the workplace that will influence their concentration and performance in the workplace.

Additionally, the benefits of this kind of monitoring transcend beyond the workplace and beyond the purpose of offering the business a competitive edge. This form of monitoring will also assist the employees in enhancing their personal wellbeing and not just that of the business.

An example of a business that is a frontrunner in this aspect is the BP Company . BP gives its employees fitness trackers as part of a programme geared at reducing the healthcare costs incurred by employees. For this form of monitoring to be initiated, it would be necessary for the employees to consent that they are comfortable with their employer having such personal and probably sensitive information. Businesses would, in turn, be required to act in good faith and protect their employees’ information from being misused by unauthorized third parties.

As mentioned earlier, the age of retirement has been gradually rising and now people work well over the age of 60 years. This can however be justified by an increase in the global life expectancy at birth by 6 years . As such, if people are going to live longer, it is only logical that other sectors of their lives are going to extend in equal proportion.

Also, the extension of retirement ages may be partially influenced by business’s that will definitely stand to incur additional costs in pension payments if the retirement age is set significantly below the average life expectancy age.

Such trends lead us to believe that the workplace of the future will accommodate even persons of even more advanced ages ; probably ages as high as 75 years. The workplace of the future will release employees gradually as opposed to the abrupt systems for retirement that we have right now. For some employees, this new prospect may be exiting, but it is highly unlikely that many people will want to stay in employment at the age of 70. At this age, most people want to be settled and relaxed without having to go through the hustles of the workplace and the work life.

However, it is important to note that this extension in retirement ages may be quite beneficial to businesses. Older employees have amassed years, if not decades of experience that can be passed on to younger employees, and the longer the elder employees are around the more knowledge will be imparted to the next generation. This will ensure that business never experience an air bubble in terms of their employees’ skill or expertise.

SHOULD WE LOOK FORWARD TO THE WORKPLACE OF THE FUTURE

Human beings are naturally afraid of the unknown. This is a result of millions of years of conditioning geared at preserving our own survival. Anything that we cannot fully understand is perceived as danger and in most cases we run away from it. Nonetheless, let us try to be objective for a moment and consider what the implications of the future changes in workplaces as we know them will be.

The world is experiencing drastic changes in the workplace as we proceed further and further into the future. This does not simply imply transformation of office spaces; it goes beyond that. The future workplace will change how people in workplaces interact and execute duties. The question now lies in whether this transformation is something to look forward to or something to dread.

- Connection . New workplaces, with more horizontal hierarchical setups , will encourage the establishment of both calculated and spontaneous connections between personnel. Breaking down the barriers that exist across all levels in our current workplaces will enhance our business’s services as well as employee performance. Leveraging the diverse perspectives through open communication encouraged by this open workplace setting will result in the formulation of outstanding solutions and ideas in businesses.

- Community. We encounter exceptional people in our workplaces all the time but we rarely ever get time to establish common ground. The workplace of the future will change this and enable people to build long lasting connections with one another. This is because the setting of the future workplaces, with open communication, will blur the line between personal and professional life. In addition to this, delays in retirement will encourage mentorship in the workplace and the creation of ‘father’ and ‘mother’ figures in businesses. With this sort of environment, an atmosphere of family and togetherness will emerge, enabling workers to relate better and ultimately boost their performance.

- Flexibility. The days of single-focus career paths are coming to an end and our future work places will evolve to reflect this new reality. Future workplaces will allow for more agility, accommodating diverse working styles, schedules, and employee needs. For example, freelance working has been gradually becoming accepted in businesses and continues to gain popularity as we march forward into the future.

- Inclusion. Future workplaces will encourage inclusion of workers of all kinds. Whether your concerns involve religion, accessibility, or an unpredictable schedule; workplaces in the future will create environments that support our diverse and unique needs. For example, I have encountered workplaces nowadays that set aside a religious room for their Muslim employees to be able to conduct their routine prayers even while at work. The workplace of the future will include everyone and will enable people to create the kind of careers they want without watering down their individuality.

- Genuine Collaboration. The establishment of a more pleasurable and relaxed work environment will promote creative teamwork that is unlimited by the psychological and structural barriers of workplaces today. This will promote genuine collaboration in the workplace because, when teamwork is encouraged, people get inspired and feel free to come up with creative and out-of-the box solutions and ideas that promote business growth.

- Competitive Edge. The workplace of the future, by creating a new way of working will aid in the modernization of our businesses, attract more clients, and stand out from competition. Through the reinvention of workspaces, businesses will be able to position themselves as market leaders. This is because these businesses will be forward-thinking and will in turn attain the ability to deliver extraordinary employee and consumer experiences. The workplace of the future is not just a new workspace, but a totally new outlook on work.

With this in mind, I think it is safe to say that future workplaces are nothing to be apprehensive about but rather something to really look forward to. Despite the fear that advanced technological interventions might render many of our careers obsolete; the benefits that we will realize will, in all probability, lead to the creation of more creative and engaging roles for the workforce. Therefore, let us not be afraid to walk into the unknown. Let us dare to embrace and immerse ourselves into the future and make it an even more prosperous one.

Despite the immense changes we have realized in our personal lives as a result of technology, our workplaces have retained a structure that is more related to the olden eras than the digital era. Most of us still work in offices that are structured to assign every person a supervisor; structures that deny them autonomy and limit their capacity to be creative or even think for themselves.

This will not be the norm for much longer. The future workplace promises to be less centralized, flexible, and mobile. The only workers who have gotten a taste of the future are freelance employees, and employees of progressive organizations such as Google . The workplace of the future is rapidly being accelerated and drawn closer by giant steps in economic volatility, technology, and the global race for the best employee talent.

Due to workplaces of the future, businesses will realize benefits through an increase in employee productivity, which will lead to better business bottom lines. There is one thing that remains constant in the world we live in; Change. Planning for the changes that will come with the future workplace is not an easy task.

However, being unopposed to change and leaving the past behind will enable us to be front runners in a world of rapidly evolving workplaces and marketplaces. Tiny and gradual measures today taken in an effort to promote easier communication, connectivity, creativity, and personalization at the workplace enable your business to prepare for the workplace of the future and to stand out among thousands if not millions of other businesses as the future approaches.

Image credit: pexel | photos.oliur.com under CC0 License .

Comments are closed.

Related posts

Idea Generation and Problem Solving Using SCAMPER Technique

SCAMPER is a very powerful idea generation and creativity technique. It is an especially useful …

NetBase | Interview with its Chief Innovation Officer & Co-Founder – Michael Osofsky

In Mountain View (CA), we meet Chief Innovation Officer and Co-Founder of NetBase, Michael Osofsky. …

Best Uses of Big Data in Recruiting

Big Data – the collection of larger than average datasets that require unconventional storage, …

408,000 + job opportunities

Not yet a member? Sign Up

join cleverism

Find your dream job. Get on promotion fasstrack and increase tour lifetime salary.

Post your jobs & get access to millions of ambitious, well-educated talents that are going the extra mile.

First name*

Company name*

Company Website*

E-mail (work)*

Login or Register

Password reset instructions will be sent to your E-mail.

David Perell

The Future of Work

Sometimes, it feels like we’re living in a science fiction novel. Robots and sophisticated computer algorithms have workers around the world fearing automation. This widespread distress has contributed to today’s turbulent political environment and specifically, many of the issues that Americans grapple with today.

The digital revolution is a fiercely powerful trend. A World Economic Forum study noted that 65% of students entering primary school today will end up working jobs that don’t exist yet. Yuval Noah Harari, author of Homo Deus : A Brief History of Tomorrow argues that 99 percent of human qualities and abilities are simply redundant for the performance of most modern jobs.

By nature, technological change leads to an exponential rate of change. Automation, speed, globalization, and complexity increase non-linearly over time. The result is an interconnected environment that is seemingly random and complex.

The law of accelerating returns says that human progress moves faster and faster over time. The law states that the rate of technological change doubles every year. Linear thinking has made sense until recently. The natural world changes in a slow and gradual fashion. Humans are biologically fit for a simple world with linear change. The modern world is complex and change is non-linear. We need fresh ways of thinking about the nature of work to succeed in this complex and rapidly evolving new world.

Today, skills that were once relevant for a lifetime are only relevant for decades. Soon, these skills will only be relevant for a few years. Ask anybody who is over the age of 50, and they will tell you that they are overwhelmed by technological advancement. Many of them “just do not get it.” The differences in how generational gaps think, learn and communicate expand every year. An eternal state of chaos and complexity is emerging. This reality of exponential non-linear change challenges the foundational institutions born out of the 20th century — namely education and jobs.

As the rate of change shoots skywards, computers and mobile technologies are uniquely enabled to process and synthesize these paradigm shifts.

How we prepare and respond to these changes will determine our ability to prosper in the 21st century work environment.

This new emerging work environment rewards an entrepreneurial, nimble mindset. Business owners and brand owners are plugging into existing technologies and selling their products to diverse populations around the world. The commoditization of distribution has given rise to global marketplaces that aggregate hundreds of thousands of unique individuals. Geographically limited and remote markets have turned global.

In this new world, people are incentivized to produce customized and diversified work for distinct niche markets. The next decade will give rise to companies and entrepreneurs that can connect with consumers on a more personal level. We are already seeing the end of mainstream, “one size fits markets — examples include razors, music, philanthropy, media, clothing, and cosmetics.

Routine tasks are increasingly being automated by powerful machine learning algorithms or low cost labor around the world. The result is a market that rewards human ingenuity and creativity, making it more possible than ever before to focus on what we, as 21st century workers, “do best.”

Alec Ross, the former Senior Advisor of Innovation for former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton explains how geographical areas are adapting to the 21st century. In his book, Industries of the Future , Ross contrasts attitudes to show how two regions prepared for the 21st century. Ross compared his home state of West Virginia, with 1.8 million citizens, to Estonia, an Eastern European country with fewer than 1.5 million citizens.

The State of West Virginia hung on to coal as its main industry export even as it became automated. The state of Virginia is built on the coal industry in the same way Pittsburg is built on the steel industry, and Detroit for automobiles. In the early 1900s, West Virginia expanded into chemical and plastic production. These were stable industries that provided prosperity to local citizens. For a century, the “Chemical Valley,” which neighbored Charleston, hosted the highest concentration of chemical manufacturers in the United States including Union Carbide, DuPont and Monsanto. However, the end of the 20th century, the economy ceased to flow as these industries collapsed. Machines replaced coal miners and chemical companies relocated their plants to India and Mexico in search of cheap labor and fewer regulations. West Virginia saw a rapid rise in unemployment, degraded infrastructure and cultural distress. From 1960 to 1990, the state capital of Charleston lost 40 percent of its population. By 1988, West Virginia’s unemployment rate was close to double the USA’s national average.

Across the world, the powerful forces of globalization hit manufacturing hubs hardest. Charleston flourished through years of stable economic growth in the early 20th century, only to be hit hard by technologically induced capital and production flight. The downfall of Pittsburgh’s steel sector contributed to rapid migration and a stagnation in job growth. In Detroit, the population declined from 1.8 million to 700,000 as automobile manufacturing jobs moved elsewhere. Manufacturing hubs like Charleston, West Virginia struggled to face a downward turn, while geographical centers that embraced technology advancements thrived into the 21st century.

After regaining independence in 1991, Estonia benefited from a fresh perspective and new ways of thinking about the future. Estonia leaned and stretched into the future through a national embrace of computer science education, digital currencies, and digital transparency. A collective culture of innovation was born. Estonian students learned to code beginning in the first grade, and government services, including voting, were conducted online. These tech-friendly policies had a powerful impact. Estonia now holds the world record of startups per person, yearly tax returns take less than five minutes, and the country enabled startups such as Skype which sold to eBay for $2.6 billion in 2006. These results speak for themselves.

How cities, states, and countries respond to this new rate of change will impact their level of political and economic preparedness for the 21st century landscape. In the same way, how we prepare and adapt to 21st century labor trends will dramatically shape our quality of life. Leaning into the future is the only option. Let’s be like Estonia, not West Virginia.

The industrial revolution brought dramatic acceleration to the economy. Before 1850, connections and communications were local. Most citizens never traveled farther than 50 miles from their original birthplace. They personally knew the farmers that grew their food, they frequented the same merchants that sold their goods, and they wore clothes that were locally manufactured. Most communities were relatively self-sufficient.

The 20th century kick-started globalization. People, products and ideas could travel across the world efficiently and quickly at lower costs. Shipping containers, interstate highways and networked telecommunications infrastructure connected the world and reshaped the playing field. Throughout the latter half of the 20th century, economic and production advancements accelerated GDP growth. The epoch was dominated by multinational corporations, stock market investments and growth, driven by consumerism of the western world. The world was transformed by, advancements in communication technologies, electricity and the automobile.

As Thomas Friedman wrote in his 2005 book, The World is Flat , we are entering a brave new world defined by an unprecedented rate of change. An entirely new and global playing field that will disrupt well-established theories of economics, politics, and work. Friedman says we are entering the third wave of globalization. Globalization 1.0 was spurred by countries and governments while multinational corporations led Globalization 2.0. Now, we are on the brink of Globalization 3.0. This third wave will be defined by complex global supply chains and increased competition. The emerging abilities of individuals and developing countries will reshape the global economic landscape. Due to the competitive nature of this new world, individuals who differentiate themselves will do best.

The rapid pace of technological change has lowered the “half life of skills”, which is the period of time with which existing skills are likely to be superseded by better ones.

Source : Benedict Evans

This photo shows a scene in the movie, The Apartment , a 1960s film featuring a clerk in a large New York insurance company. This office depicts hundreds of workers with telephones, Rolodexes, typewriters and large electro-mechanical calculating machines.

Today, the jobs of most all these workers have been replaced by Excel spreadsheets, laptops, high capacity servers and mobile handheld devices.

In medieval times, skills extended over many centuries. In the industrial economy, skills extended over many generations. Now, skills last less than a career, and very soon, they will last less than a decade. Skills are becoming ephemeral and impermanent. The “half-life of skills” has never been lower and will continue to decrease.

The digital revolution, which took off with the introduction of the iPhone is largely encapsulated by the instant spread of ideas and information, inspired significant workplace changes. With exponential population increases in emerging growth nations, the result is an abundant global supply of low wage workers. Millions of technological jobs have been outsourced. India, Bangladesh, Turkey, Southeast Asia and China have become skilled manufacturing hubs, while the United States has emerged as a hub for design, innovation and new ideas. This is a good thing for people who can adapt to change. However, this trend is a challenge for those who cannot. In the USA and Western Europe, routine tasks, from manufacturing to processing, to accounting to medical procedures, are being automated by robots and intelligence algorithms managed and stored on cloud-based servers. The result in the USA is a climate of labor abundance.

Three recent books on the economies of the future, Industries of the Future , The Future of Professions , and Inventing the Future all came to the same conclusion: robots are taking our jobs and it is going to happen soon. Robots surpass human capabilities on multiple levels. They can work 24 hours per day with more precision at a lower cost. Jeff Bezos, the CEO of Amazon, who purchased a robotics company in 2012, recently stated “it’s hard to overstate how big of an impact robots are going to have on society over the next twenty years.”

Robots are already fulfilling hundreds of thousands of orders every day for Amazon Prime customers. Large robotic arms take care of routine tasks that can be automated. Humans are responsible for cognitive, non-routine tasks that require problem solving and flexibility.

Amazon Robots

We are already seeing the second order effects of globalization reflected in tense political climates around the world. We have seen a backlash from Britain, to Hungary, to the United States. The backlash has come in the form of nationalism, closing borders, and rising political tension. In Britain, the people who voted for Brexit were, disproportionately older, less educated, poorer, and working class. CNN political analyst Fareed Zakaria believes we are seeing the emergence of a new political divide between openness towards globalization and technological change, and national sovereignty and border control.

The new divide is likely to shape Western politics for the next 50 years and will only become stronger due to technological advancements.

We are just beginning to see the ancillary effects of automation. Increasingly ambitious, technically precise, customized tasks require fewer and fewer people. One needs to look no further than Amazon, worth more than $400 billion, with less than 350,000 employees. By contrast, WalMart, a staple of the post World War II boom is valued at $211 billion with over 2.3 million employees worldwide.

The numbers are even more staggering in the software businesses. Blockbuster, formerly a retail giant distributing videos and CD’s from big box retail stores employing 60,000 jobs, gave way to Netflix an online subscription delivery model, employing 2,000 jobs.

The returns for a small cohort of winners are increasing exponentially as companies scale more efficiently at lower costs. Once prestigious work is being displaced by technology. JP Morgan & Chase Co. software automates the tedious and routine interpretation of commercial-loan agreements. These tasks once consumed 360,000 hours of work each year by lawyers and loan officers.

According to some estimates, the changes brought to the global economy in the next two decades could be as impactful as the entire industrial revolution, which took more than a century and a half to materialize. This rapid change marks the advent of increasing complexity, unpredictability and randomness. We must confront reality as it is, not as we wish it were.

Robots and computers far exceed human capabilities when similar processes are repeated multiple times, over and over again. The good news is that creativity and ambition can now be realized like never before. Creative work is more likely to be enjoyable and creatives are less likely to lose their jobs to robots.

The Internet has opened the door for niche businesses that tap into human creativity. Recent guests on my podcast, the North Star , have included some creative talent who stay on top of emerging niche opportunities — stop motion animators, illustrators, and two self-published authors to name a few.

The history of human automation shows us that new and better jobs are created when automation replaces traditional workers. This will continue. As the number of people participating on both the supply side and the demand side of the global market grows, economic opportunity emerges at the edges where algorithms cannot replicate human creativity and only motivated and talented individuals can build their own businesses. Unskilled, soon-to-be commoditized labor is not a great career plan.

The old world, defined by assembly lines and large work environments rewarded manual and routine work. Manpower was everything and workers adopted the 9-to-5 schedule which arose out of the need to coordinate worker hours and facilities uses. An Oxford University research paper concluded that machines will take over nearly half of the work done by all humans.

To date, automation has helped overall standards of living, improved literacy rates, lengthened the average life span, and contributed to falling crime rates. In 1908, it took about 4,800 hours of work to purchase a Model T. Today, the average person has to work about 1,000 hours to buy a car that is much better than the Model T. By 2030, robots won’t just build our cars. Robots will drive them too. They will replace taxi drivers, truck drivers, and train conductors.

The new, emerging world rewards cognitive, non-routine work that reflects a creator’s individuality, which cannot be automated. Even routine knowledge work in the areas of accounting, medicine, and law are becoming automated. Workers in these occupations may be intrinsically motivated to try to advance their careers, while the forces of automation and technological advancements will put them and millions of other general skill and manufacturing workers out of jobs and leave hundreds of companies without a future — if they don’t adapt.

The rapid arrival of new technologies is unpreventable. Humans will compete directly with machines and algorithms that continuously improve and operate 24 hours per day. The world emerges with more connected, complex, non-linear, interrelated, adaptive and spontaneously evolving networks with each passing day, giving humans who conduct cognitive, non-routine, quick to market, high value work a tremendous advantage in the 21st century economy.

To thrive in this new world, we must respond to the rising value of individual creativity and the adaptive power of robotics, personalization, customization and mobile automation which will iterate and evolve at a rapid pace.

Differentiated workers will perform best. They will harness the unique capabilities of the internet and build their careers around the new realities of the modern world. We should build our careers and work styles around the inevitabilities of globalization, abundance, and automation.

- http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/12/19/our-automated-future

- http://www.newsweek.com/2016/12/09/robot-economy-artificial-intelligence-jobs-happy-ending-526467.html

- www.cnn.com/2016/06/27/opinions/western-world-after-brexit-vote-zakaria/

- http://www.economist.com/news/books-and-arts/21685437-why-economic-growth-soared-america-early-20th-century-and-why-it-wont-be

How To Build Your Personal Monopoly

Download a free lesson from my premier program Write of Passage course and uncover your strengths, clearly communicate your value, and start building your reputation online today.

Accelerate Your Career by Writing Online

Write of Passage teaches a step-by-step method for publishing quality content. Learn more .

The Future of Work Should Mean Working Less

By Jonathan Malesic Sept. 23, 2021

- Share full article

Mr. Malesic is a writer and a former academic, sushi chef and parking lot attendant who holds a Ph.D. in religious studies. He is the author of the forthcoming book “ The End of Burnout ,” from which this essay is adapted.

A dozen years ago, my friend Patricia Nordeen was an ambitious academic, teaching at the University of Chicago and speaking at conferences across the country. “Being a political theorist was my entire adult identity,” she told me recently. Her work determined where she lived and who her friends were. She loved it. Her life, from classes to research to hours spent in campus cafes, felt like one long, fascinating conversation about human nature and government.

But then she started getting very sick. She needed spinal fusion surgeries. She had daily migraines. It became impossible to continue her career. She went on disability and moved in with relatives. For three years she had frequent bouts of paralysis. She was eventually diagnosed with a subtype of Ehlers-Danlos syndromes, a group of hereditary disorders that weaken collagen, a component of many sorts of tissue.

“I’ve had to evaluate my core values,” she said, and find a new identity and community without the work she loved. Chronic pain made it hard to write, sometimes even to read. She started drawing, painting and making collages, posting the art on Instagram. She made friends there and began collaborations with them, like a 100-day series of sketchbook pages — abstract watercolors, collages, flower studies — she exchanged with another artist. A project like this allows her to exercise her curiosity. It also “gives me a sense of validation, like I’m part of society,” she said.

Art does not give Patricia the total satisfaction academia did. It doesn’t order her whole life. But for that reason, I see in it an important effort, one every one of us will have to make sooner or later: an effort to prove, to herself and others, that we exist to do more than just work.

We need that truth now, when millions are returning to in-person work after nearly two years of mass unemployment and working from home. The conventional approach to work — from the sanctity of the 40-hour week to the ideal of upward mobility — led us to widespread dissatisfaction and seemingly ubiquitous burnout even before the pandemic. Now, the moral structure of work is up for grabs. And with labor-friendly economic conditions, workers have little to lose by making creative demands on employers. We now have space to reimagine how work fits into a good life.

As it is, work sits at the heart of Americans’ vision of human flourishing. It’s much more than how we earn a living. It’s how we earn dignity: the right to count in society and enjoy its benefits. It’s how we prove our moral character. And it’s where we seek meaning and purpose, which many of us interpret in spiritual terms.

Political, religious and business leaders have promoted this vision for centuries, from Capt. John Smith’s decree that slackers would be banished from the Jamestown settlement to Silicon Valley gurus’ touting work as a transcendent activity . Work is our highest good; “do your job,” our supreme moral mandate.

But work often doesn’t live up to these ideals. In our dissent from this vision and our creation of a better one, we ought to begin with the idea that each one of us has dignity whether we work or not. Your job, or lack of one, doesn’t define your human worth.

This view is simple yet radical. It justifies a universal basic income and rights to housing and health care. It justifies a living wage. It also allows us to see not just unemployment but retirement, disability and caregiving as normal, legitimate ways to live.

When American politicians talk about the dignity of work, like when they argue that welfare recipients must be employed, they usually mean you count only if you work for pay.

The pandemic revealed just how false this notion is. Millions lost their jobs overnight. They didn’t lose their dignity. Congress acknowledged this fact, offering unprecedented jobless benefits: for some, a living wage without having to work.

The idea that all people have dignity before they ever work, or if they never do, has been central to Catholic social teaching for at least 130 years. In that time, popes have argued that jobs ought to fit the capacities of the people who hold them, not the productivity metrics of their employers. Writing in 1891, Pope Leo XIII argued that working conditions, including hours, should be adapted to “the health and strength of the workman.”

Leo mentioned miners as deserving “shorter hours in proportion as their labor is more severe and trying to health.” Today, we might say the same about nurses, or any worker whose ordinary limitations — whether a bad back or a mental health condition — makes an intense eight-hour shift too much to bear. Patricia Nordeen would like to teach again one day, but given her health at the moment, full-time work seems out of the question.

Because each of us is both dignified and fragile, our new vision should prioritize compassion for workers, in light of work’s power to deform their bodies, minds and souls. As Eyal Press argues in his new book, “ Dirty Work ,” people who work in prisons, slaughterhouses and oil fields often suffer moral injury, including post-traumatic stress disorder, on the job. This reality challenges the notion that all work builds character.

Wage labor can harm us in subtle and insidious ways, too. The American ideal of a good life earned through work is “disciplinary,” according to the Marxist feminist political philosopher Kathi Weeks, a professor at Duke and often-cited critic of the modern work ethic. “It constructs docile subjects,” she wrote in her 2011 book, “ The Problem With Work .” Day to day, that means we feel pressure to become the people our bosses, colleagues, clients and customers want us to be. When that pressure conflicts with our human needs and well-being, we can fall into burnout and despair.

To limit work’s negative moral effects on people, we should set harder limits on working hours. Dr. Weeks calls for a six-hour work day with no pay reduction. And we who demand labor from others ought to expect a bit less of people whose jobs grind them down.

In recent years, the public has become more aware of conditions in warehouses and the gig economy. Yet we have relied on inventory pickers and delivery drivers ever more during the pandemic. Maybe compassion can lead us to realize we don’t need instant delivery of everything and that workers bear the often-invisible cost of our cheap meat and oil.

The vision of less work must also encompass more leisure. For a time the pandemic took away countless activities, from dinner parties and concerts to in-person civic meetings and religious worship. Once they can be enjoyed safely, we ought to reclaim them as what life is primarily about, where we are fully ourselves and aspire to transcendence.

Leisure is what we do for its own sake. It serves no higher end. Patricia said that making art is often “meditative” for her. “If I’m trying to draw a plant, I’m really looking at the plant,” she said. “I’m noticing all the different shades of color that maybe I wouldn’t have noticed if I wasn’t drawing it.” Her absorption in the task — the feel of the pen on paper — “puts the pain out of focus.”