Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Definition and Purpose of Abstracts

An abstract is a short summary of your (published or unpublished) research paper, usually about a paragraph (c. 6-7 sentences, 150-250 words) long. A well-written abstract serves multiple purposes:

- an abstract lets readers get the gist or essence of your paper or article quickly, in order to decide whether to read the full paper;

- an abstract prepares readers to follow the detailed information, analyses, and arguments in your full paper;

- and, later, an abstract helps readers remember key points from your paper.

It’s also worth remembering that search engines and bibliographic databases use abstracts, as well as the title, to identify key terms for indexing your published paper. So what you include in your abstract and in your title are crucial for helping other researchers find your paper or article.

If you are writing an abstract for a course paper, your professor may give you specific guidelines for what to include and how to organize your abstract. Similarly, academic journals often have specific requirements for abstracts. So in addition to following the advice on this page, you should be sure to look for and follow any guidelines from the course or journal you’re writing for.

The Contents of an Abstract

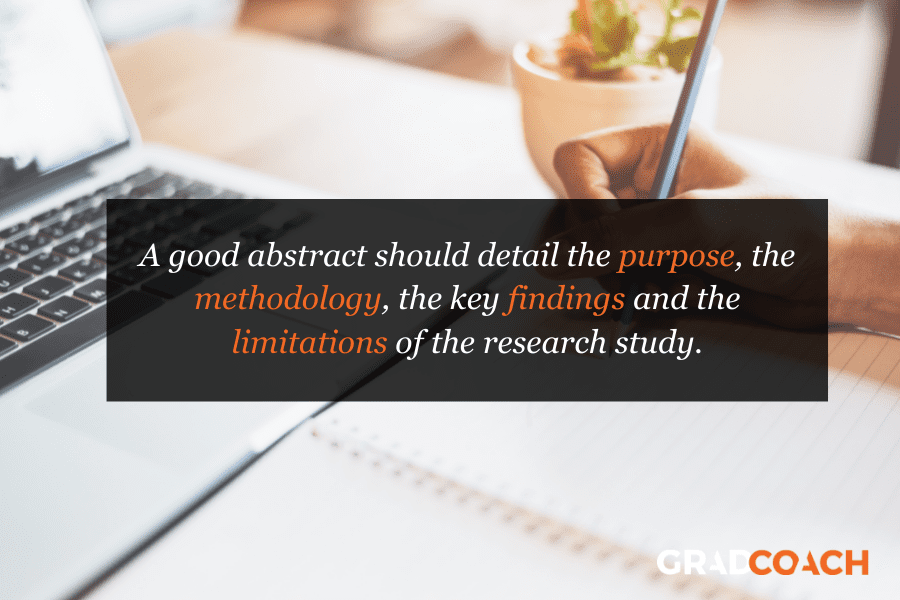

Abstracts contain most of the following kinds of information in brief form. The body of your paper will, of course, develop and explain these ideas much more fully. As you will see in the samples below, the proportion of your abstract that you devote to each kind of information—and the sequence of that information—will vary, depending on the nature and genre of the paper that you are summarizing in your abstract. And in some cases, some of this information is implied, rather than stated explicitly. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , which is widely used in the social sciences, gives specific guidelines for what to include in the abstract for different kinds of papers—for empirical studies, literature reviews or meta-analyses, theoretical papers, methodological papers, and case studies.

Here are the typical kinds of information found in most abstracts:

- the context or background information for your research; the general topic under study; the specific topic of your research

- the central questions or statement of the problem your research addresses

- what’s already known about this question, what previous research has done or shown

- the main reason(s) , the exigency, the rationale , the goals for your research—Why is it important to address these questions? Are you, for example, examining a new topic? Why is that topic worth examining? Are you filling a gap in previous research? Applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data? Resolving a dispute within the literature in your field? . . .

- your research and/or analytical methods

- your main findings , results , or arguments

- the significance or implications of your findings or arguments.

Your abstract should be intelligible on its own, without a reader’s having to read your entire paper. And in an abstract, you usually do not cite references—most of your abstract will describe what you have studied in your research and what you have found and what you argue in your paper. In the body of your paper, you will cite the specific literature that informs your research.

When to Write Your Abstract

Although you might be tempted to write your abstract first because it will appear as the very first part of your paper, it’s a good idea to wait to write your abstract until after you’ve drafted your full paper, so that you know what you’re summarizing.

What follows are some sample abstracts in published papers or articles, all written by faculty at UW-Madison who come from a variety of disciplines. We have annotated these samples to help you see the work that these authors are doing within their abstracts.

Choosing Verb Tenses within Your Abstract

The social science sample (Sample 1) below uses the present tense to describe general facts and interpretations that have been and are currently true, including the prevailing explanation for the social phenomenon under study. That abstract also uses the present tense to describe the methods, the findings, the arguments, and the implications of the findings from their new research study. The authors use the past tense to describe previous research.

The humanities sample (Sample 2) below uses the past tense to describe completed events in the past (the texts created in the pulp fiction industry in the 1970s and 80s) and uses the present tense to describe what is happening in those texts, to explain the significance or meaning of those texts, and to describe the arguments presented in the article.

The science samples (Samples 3 and 4) below use the past tense to describe what previous research studies have done and the research the authors have conducted, the methods they have followed, and what they have found. In their rationale or justification for their research (what remains to be done), they use the present tense. They also use the present tense to introduce their study (in Sample 3, “Here we report . . .”) and to explain the significance of their study (In Sample 3, This reprogramming . . . “provides a scalable cell source for. . .”).

Sample Abstract 1

From the social sciences.

Reporting new findings about the reasons for increasing economic homogamy among spouses

Gonalons-Pons, Pilar, and Christine R. Schwartz. “Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” Demography , vol. 54, no. 3, 2017, pp. 985-1005.

![abstract example in qualitative research “The growing economic resemblance of spouses has contributed to rising inequality by increasing the number of couples in which there are two high- or two low-earning partners. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the topic under study (the “economic resemblance of spouses”). This sentence also implies the question underlying this research study: what are the various causes—and the interrelationships among them—for this trend?] The dominant explanation for this trend is increased assortative mating. Previous research has primarily relied on cross-sectional data and thus has been unable to disentangle changes in assortative mating from changes in the division of spouses’ paid labor—a potentially key mechanism given the dramatic rise in wives’ labor supply. [Annotation for the previous two sentences: These next two sentences explain what previous research has demonstrated. By pointing out the limitations in the methods that were used in previous studies, they also provide a rationale for new research.] We use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to decompose the increase in the correlation between spouses’ earnings and its contribution to inequality between 1970 and 2013 into parts due to (a) changes in assortative mating, and (b) changes in the division of paid labor. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The data, research and analytical methods used in this new study.] Contrary to what has often been assumed, the rise of economic homogamy and its contribution to inequality is largely attributable to changes in the division of paid labor rather than changes in sorting on earnings or earnings potential. Our findings indicate that the rise of economic homogamy cannot be explained by hypotheses centered on meeting and matching opportunities, and they show where in this process inequality is generated and where it is not.” (p. 985) [Annotation for the previous two sentences: The major findings from and implications and significance of this study.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-1.png)

Sample Abstract 2

From the humanities.

Analyzing underground pulp fiction publications in Tanzania, this article makes an argument about the cultural significance of those publications

Emily Callaci. “Street Textuality: Socialism, Masculinity, and Urban Belonging in Tanzania’s Pulp Fiction Publishing Industry, 1975-1985.” Comparative Studies in Society and History , vol. 59, no. 1, 2017, pp. 183-210.

![abstract example in qualitative research “From the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s, a network of young urban migrant men created an underground pulp fiction publishing industry in the city of Dar es Salaam. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the context for this research and announces the topic under study.] As texts that were produced in the underground economy of a city whose trajectory was increasingly charted outside of formalized planning and investment, these novellas reveal more than their narrative content alone. These texts were active components in the urban social worlds of the young men who produced them. They reveal a mode of urbanism otherwise obscured by narratives of decolonization, in which urban belonging was constituted less by national citizenship than by the construction of social networks, economic connections, and the crafting of reputations. This article argues that pulp fiction novellas of socialist era Dar es Salaam are artifacts of emergent forms of male sociability and mobility. In printing fictional stories about urban life on pilfered paper and ink, and distributing their texts through informal channels, these writers not only described urban communities, reputations, and networks, but also actually created them.” (p. 210) [Annotation for the previous sentences: The remaining sentences in this abstract interweave other essential information for an abstract for this article. The implied research questions: What do these texts mean? What is their historical and cultural significance, produced at this time, in this location, by these authors? The argument and the significance of this analysis in microcosm: these texts “reveal a mode or urbanism otherwise obscured . . .”; and “This article argues that pulp fiction novellas. . . .” This section also implies what previous historical research has obscured. And through the details in its argumentative claims, this section of the abstract implies the kinds of methods the author has used to interpret the novellas and the concepts under study (e.g., male sociability and mobility, urban communities, reputations, network. . . ).]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-2.png)

Sample Abstract/Summary 3

From the sciences.

Reporting a new method for reprogramming adult mouse fibroblasts into induced cardiac progenitor cells

Lalit, Pratik A., Max R. Salick, Daryl O. Nelson, Jayne M. Squirrell, Christina M. Shafer, Neel G. Patel, Imaan Saeed, Eric G. Schmuck, Yogananda S. Markandeya, Rachel Wong, Martin R. Lea, Kevin W. Eliceiri, Timothy A. Hacker, Wendy C. Crone, Michael Kyba, Daniel J. Garry, Ron Stewart, James A. Thomson, Karen M. Downs, Gary E. Lyons, and Timothy J. Kamp. “Lineage Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Proliferative Induced Cardiac Progenitor Cells by Defined Factors.” Cell Stem Cell , vol. 18, 2016, pp. 354-367.

![abstract example in qualitative research “Several studies have reported reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes; however, reprogramming into proliferative induced cardiac progenitor cells (iCPCs) remains to be accomplished. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence announces the topic under study, summarizes what’s already known or been accomplished in previous research, and signals the rationale and goals are for the new research and the problem that the new research solves: How can researchers reprogram fibroblasts into iCPCs?] Here we report that a combination of 11 or 5 cardiac factors along with canonical Wnt and JAK/STAT signaling reprogrammed adult mouse cardiac, lung, and tail tip fibroblasts into iCPCs. The iCPCs were cardiac mesoderm-restricted progenitors that could be expanded extensively while maintaining multipo-tency to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells in vitro. Moreover, iCPCs injected into the cardiac crescent of mouse embryos differentiated into cardiomyocytes. iCPCs transplanted into the post-myocardial infarction mouse heart improved survival and differentiated into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells. [Annotation for the previous four sentences: The methods the researchers developed to achieve their goal and a description of the results.] Lineage reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs provides a scalable cell source for drug discovery, disease modeling, and cardiac regenerative therapy.” (p. 354) [Annotation for the previous sentence: The significance or implications—for drug discovery, disease modeling, and therapy—of this reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-3.png)

Sample Abstract 4, a Structured Abstract

Reporting results about the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis, from a rigorously controlled study

Note: This journal requires authors to organize their abstract into four specific sections, with strict word limits. Because the headings for this structured abstract are self-explanatory, we have chosen not to add annotations to this sample abstract.

Wald, Ellen R., David Nash, and Jens Eickhoff. “Effectiveness of Amoxicillin/Clavulanate Potassium in the Treatment of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children.” Pediatrics , vol. 124, no. 1, 2009, pp. 9-15.

“OBJECTIVE: The role of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS) in children is controversial. The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of high-dose amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate in the treatment of children diagnosed with ABS.

METHODS : This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Children 1 to 10 years of age with a clinical presentation compatible with ABS were eligible for participation. Patients were stratified according to age (<6 or ≥6 years) and clinical severity and randomly assigned to receive either amoxicillin (90 mg/kg) with potassium clavulanate (6.4 mg/kg) or placebo. A symptom survey was performed on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 20, and 30. Patients were examined on day 14. Children’s conditions were rated as cured, improved, or failed according to scoring rules.

RESULTS: Two thousand one hundred thirty-five children with respiratory complaints were screened for enrollment; 139 (6.5%) had ABS. Fifty-eight patients were enrolled, and 56 were randomly assigned. The mean age was 6630 months. Fifty (89%) patients presented with persistent symptoms, and 6 (11%) presented with nonpersistent symptoms. In 24 (43%) children, the illness was classified as mild, whereas in the remaining 32 (57%) children it was severe. Of the 28 children who received the antibiotic, 14 (50%) were cured, 4 (14%) were improved, 4(14%) experienced treatment failure, and 6 (21%) withdrew. Of the 28children who received placebo, 4 (14%) were cured, 5 (18%) improved, and 19 (68%) experienced treatment failure. Children receiving the antibiotic were more likely to be cured (50% vs 14%) and less likely to have treatment failure (14% vs 68%) than children receiving the placebo.

CONCLUSIONS : ABS is a common complication of viral upper respiratory infections. Amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate results in significantly more cures and fewer failures than placebo, according to parental report of time to resolution.” (9)

Some Excellent Advice about Writing Abstracts for Basic Science Research Papers, by Professor Adriano Aguzzi from the Institute of Neuropathology at the University of Zurich:

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Abstract Writing: A Step-by-Step Guide With Tips & Examples

Table of Contents

Introduction

Abstracts of research papers have always played an essential role in describing your research concisely and clearly to researchers and editors of journals, enticing them to continue reading. However, with the widespread availability of scientific databases, the need to write a convincing abstract is more crucial now than during the time of paper-bound manuscripts.

Abstracts serve to "sell" your research and can be compared with your "executive outline" of a resume or, rather, a formal summary of the critical aspects of your work. Also, it can be the "gist" of your study. Since most educational research is done online, it's a sign that you have a shorter time for impressing your readers, and have more competition from other abstracts that are available to be read.

The APCI (Academic Publishing and Conferences International) articulates 12 issues or points considered during the final approval process for conferences & journals and emphasises the importance of writing an abstract that checks all these boxes (12 points). Since it's the only opportunity you have to captivate your readers, you must invest time and effort in creating an abstract that accurately reflects the critical points of your research.

With that in mind, let’s head over to understand and discover the core concept and guidelines to create a substantial abstract. Also, learn how to organise the ideas or plots into an effective abstract that will be awe-inspiring to the readers you want to reach.

What is Abstract? Definition and Overview

The word "Abstract' is derived from Latin abstractus meaning "drawn off." This etymological meaning also applies to art movements as well as music, like abstract expressionism. In this context, it refers to the revealing of the artist's intention.

Based on this, you can determine the meaning of an abstract: A condensed research summary. It must be self-contained and independent of the body of the research. However, it should outline the subject, the strategies used to study the problem, and the methods implemented to attain the outcomes. The specific elements of the study differ based on the area of study; however, together, it must be a succinct summary of the entire research paper.

Abstracts are typically written at the end of the paper, even though it serves as a prologue. In general, the abstract must be in a position to:

- Describe the paper.

- Identify the problem or the issue at hand.

- Explain to the reader the research process, the results you came up with, and what conclusion you've reached using these results.

- Include keywords to guide your strategy and the content.

Furthermore, the abstract you submit should not reflect upon any of the following elements:

- Examine, analyse or defend the paper or your opinion.

- What you want to study, achieve or discover.

- Be redundant or irrelevant.

After reading an abstract, your audience should understand the reason - what the research was about in the first place, what the study has revealed and how it can be utilised or can be used to benefit others. You can understand the importance of abstract by knowing the fact that the abstract is the most frequently read portion of any research paper. In simpler terms, it should contain all the main points of the research paper.

What is the Purpose of an Abstract?

Abstracts are typically an essential requirement for research papers; however, it's not an obligation to preserve traditional reasons without any purpose. Abstracts allow readers to scan the text to determine whether it is relevant to their research or studies. The abstract allows other researchers to decide if your research paper can provide them with some additional information. A good abstract paves the interest of the audience to pore through your entire paper to find the content or context they're searching for.

Abstract writing is essential for indexing, as well. The Digital Repository of academic papers makes use of abstracts to index the entire content of academic research papers. Like meta descriptions in the regular Google outcomes, abstracts must include keywords that help researchers locate what they seek.

Types of Abstract

Informative and Descriptive are two kinds of abstracts often used in scientific writing.

A descriptive abstract gives readers an outline of the author's main points in their study. The reader can determine if they want to stick to the research work, based on their interest in the topic. An abstract that is descriptive is similar to the contents table of books, however, the format of an abstract depicts complete sentences encapsulated in one paragraph. It is unfortunate that the abstract can't be used as a substitute for reading a piece of writing because it's just an overview, which omits readers from getting an entire view. Also, it cannot be a way to fill in the gaps the reader may have after reading this kind of abstract since it does not contain crucial information needed to evaluate the article.

To conclude, a descriptive abstract is:

- A simple summary of the task, just summarises the work, but some researchers think it is much more of an outline

- Typically, the length is approximately 100 words. It is too short when compared to an informative abstract.

- A brief explanation but doesn't provide the reader with the complete information they need;

- An overview that omits conclusions and results

An informative abstract is a comprehensive outline of the research. There are times when people rely on the abstract as an information source. And the reason is why it is crucial to provide entire data of particular research. A well-written, informative abstract could be a good substitute for the remainder of the paper on its own.

A well-written abstract typically follows a particular style. The author begins by providing the identifying information, backed by citations and other identifiers of the papers. Then, the major elements are summarised to make the reader aware of the study. It is followed by the methodology and all-important findings from the study. The conclusion then presents study results and ends the abstract with a comprehensive summary.

In a nutshell, an informative abstract:

- Has a length that can vary, based on the subject, but is not longer than 300 words.

- Contains all the content-like methods and intentions

- Offers evidence and possible recommendations.

Informative Abstracts are more frequent than descriptive abstracts because of their extensive content and linkage to the topic specifically. You should select different types of abstracts to papers based on their length: informative abstracts for extended and more complex abstracts and descriptive ones for simpler and shorter research papers.

What are the Characteristics of a Good Abstract?

- A good abstract clearly defines the goals and purposes of the study.

- It should clearly describe the research methodology with a primary focus on data gathering, processing, and subsequent analysis.

- A good abstract should provide specific research findings.

- It presents the principal conclusions of the systematic study.

- It should be concise, clear, and relevant to the field of study.

- A well-designed abstract should be unifying and coherent.

- It is easy to grasp and free of technical jargon.

- It is written impartially and objectively.

What are the various sections of an ideal Abstract?

By now, you must have gained some concrete idea of the essential elements that your abstract needs to convey . Accordingly, the information is broken down into six key sections of the abstract, which include:

An Introduction or Background

Research methodology, objectives and goals, limitations.

Let's go over them in detail.

The introduction, also known as background, is the most concise part of your abstract. Ideally, it comprises a couple of sentences. Some researchers only write one sentence to introduce their abstract. The idea behind this is to guide readers through the key factors that led to your study.

It's understandable that this information might seem difficult to explain in a couple of sentences. For example, think about the following two questions like the background of your study:

- What is currently available about the subject with respect to the paper being discussed?

- What isn't understood about this issue? (This is the subject of your research)

While writing the abstract’s introduction, make sure that it is not lengthy. Because if it crosses the word limit, it may eat up the words meant to be used for providing other key information.

Research methodology is where you describe the theories and techniques you used in your research. It is recommended that you describe what you have done and the method you used to get your thorough investigation results. Certainly, it is the second-longest paragraph in the abstract.

In the research methodology section, it is essential to mention the kind of research you conducted; for instance, qualitative research or quantitative research (this will guide your research methodology too) . If you've conducted quantitative research, your abstract should contain information like the sample size, data collection method, sampling techniques, and duration of the study. Likewise, your abstract should reflect observational data, opinions, questionnaires (especially the non-numerical data) if you work on qualitative research.

The research objectives and goals speak about what you intend to accomplish with your research. The majority of research projects focus on the long-term effects of a project, and the goals focus on the immediate, short-term outcomes of the research. It is possible to summarise both in just multiple sentences.

In stating your objectives and goals, you give readers a picture of the scope of the study, its depth and the direction your research ultimately follows. Your readers can evaluate the results of your research against the goals and stated objectives to determine if you have achieved the goal of your research.

In the end, your readers are more attracted by the results you've obtained through your study. Therefore, you must take the time to explain each relevant result and explain how they impact your research. The results section exists as the longest in your abstract, and nothing should diminish its reach or quality.

One of the most important things you should adhere to is to spell out details and figures on the results of your research.

Instead of making a vague assertion such as, "We noticed that response rates varied greatly between respondents with high incomes and those with low incomes", Try these: "The response rate was higher for high-income respondents than those with lower incomes (59 30 percent vs. 30 percent in both cases; P<0.01)."

You're likely to encounter certain obstacles during your research. It could have been during data collection or even during conducting the sample . Whatever the issue, it's essential to inform your readers about them and their effects on the research.

Research limitations offer an opportunity to suggest further and deep research. If, for instance, you were forced to change for convenient sampling and snowball samples because of difficulties in reaching well-suited research participants, then you should mention this reason when you write your research abstract. In addition, a lack of prior studies on the subject could hinder your research.

Your conclusion should include the same number of sentences to wrap the abstract as the introduction. The majority of researchers offer an idea of the consequences of their research in this case.

Your conclusion should include three essential components:

- A significant take-home message.

- Corresponding important findings.

- The Interpretation.

Even though the conclusion of your abstract needs to be brief, it can have an enormous influence on the way that readers view your research. Therefore, make use of this section to reinforce the central message from your research. Be sure that your statements reflect the actual results and the methods you used to conduct your research.

Good Abstract Examples

Abstract example #1.

Children’s consumption behavior in response to food product placements in movies.

The abstract:

"Almost all research into the effects of brand placements on children has focused on the brand's attitudes or behavior intentions. Based on the significant differences between attitudes and behavioral intentions on one hand and actual behavior on the other hand, this study examines the impact of placements by brands on children's eating habits. Children aged 6-14 years old were shown an excerpt from the popular film Alvin and the Chipmunks and were shown places for the item Cheese Balls. Three different versions were developed with no placements, one with moderately frequent placements and the third with the highest frequency of placement. The results revealed that exposure to high-frequency places had a profound effect on snack consumption, however, there was no impact on consumer attitudes towards brands or products. The effects were not dependent on the age of the children. These findings are of major importance to researchers studying consumer behavior as well as nutrition experts as well as policy regulators."

Abstract Example #2

Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. The abstract:

"The research conducted in this study investigated the effects of Facebook use on women's moods and body image if the effects are different from an internet-based fashion journal and if the appearance comparison tendencies moderate one or more of these effects. Participants who were female ( N = 112) were randomly allocated to spend 10 minutes exploring their Facebook account or a magazine's website or an appearance neutral control website prior to completing state assessments of body dissatisfaction, mood, and differences in appearance (weight-related and facial hair, face, and skin). Participants also completed a test of the tendency to compare appearances. The participants who used Facebook were reported to be more depressed than those who stayed on the control site. In addition, women who have the tendency to compare appearances reported more facial, hair and skin-related issues following Facebook exposure than when they were exposed to the control site. Due to its popularity it is imperative to conduct more research to understand the effect that Facebook affects the way people view themselves."

Abstract Example #3

The Relationship Between Cell Phone Use and Academic Performance in a Sample of U.S. College Students

"The cellphone is always present on campuses of colleges and is often utilised in situations in which learning takes place. The study examined the connection between the use of cell phones and the actual grades point average (GPA) after adjusting for predictors that are known to be a factor. In the end 536 students in the undergraduate program from 82 self-reported majors of an enormous, public institution were studied. Hierarchical analysis ( R 2 = .449) showed that use of mobile phones is significantly ( p < .001) and negative (b equal to -.164) connected to the actual college GPA, after taking into account factors such as demographics, self-efficacy in self-regulated learning, self-efficacy to improve academic performance, and the actual high school GPA that were all important predictors ( p < .05). Therefore, after adjusting for other known predictors increasing cell phone usage was associated with lower academic performance. While more research is required to determine the mechanisms behind these results, they suggest the need to educate teachers and students to the possible academic risks that are associated with high-frequency mobile phone usage."

Quick tips on writing a good abstract

There exists a common dilemma among early age researchers whether to write the abstract at first or last? However, it's recommended to compose your abstract when you've completed the research since you'll have all the information to give to your readers. You can, however, write a draft at the beginning of your research and add in any gaps later.

If you find abstract writing a herculean task, here are the few tips to help you with it:

1. Always develop a framework to support your abstract

Before writing, ensure you create a clear outline for your abstract. Divide it into sections and draw the primary and supporting elements in each one. You can include keywords and a few sentences that convey the essence of your message.

2. Review Other Abstracts

Abstracts are among the most frequently used research documents, and thousands of them were written in the past. Therefore, prior to writing yours, take a look at some examples from other abstracts. There are plenty of examples of abstracts for dissertations in the dissertation and thesis databases.

3. Avoid Jargon To the Maximum

When you write your abstract, focus on simplicity over formality. You should write in simple language, and avoid excessive filler words or ambiguous sentences. Keep in mind that your abstract must be readable to those who aren't acquainted with your subject.

4. Focus on Your Research

It's a given fact that the abstract you write should be about your research and the findings you've made. It is not the right time to mention secondary and primary data sources unless it's absolutely required.

Conclusion: How to Structure an Interesting Abstract?

Abstracts are a short outline of your essay. However, it's among the most important, if not the most important. The process of writing an abstract is not straightforward. A few early-age researchers tend to begin by writing it, thinking they are doing it to "tease" the next step (the document itself). However, it is better to treat it as a spoiler.

The simple, concise style of the abstract lends itself to a well-written and well-investigated study. If your research paper doesn't provide definitive results, or the goal of your research is questioned, so will the abstract. Thus, only write your abstract after witnessing your findings and put your findings in the context of a larger scenario.

The process of writing an abstract can be daunting, but with these guidelines, you will succeed. The most efficient method of writing an excellent abstract is to centre the primary points of your abstract, including the research question and goals methods, as well as key results.

Interested in learning more about dedicated research solutions? Go to the SciSpace product page to find out how our suite of products can help you simplify your research workflows so you can focus on advancing science.

The best-in-class solution is equipped with features such as literature search and discovery, profile management, research writing and formatting, and so much more.

But before you go,

You might also like.

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

- Our History

- The Council

- Verna Wright Prize

- The Secretariat

- Key Documents and Policies

- 2024 Conference

- Abstract Submission Guidance 2024

- Past Conferences

- Past Keynote Speakers

- Courses and Lectures

- Co-Hosted Events

- External Events

- Research – Presenting Abstracts

- Research Projects

- Research Links

- Research Councils

- Qualitative Research Abstracts

- Fellowships, Studentships and Awards

- Published Abstracts

- Training Awards

- General Links

- Professional Organisations

- University and Research Vacancies

- Newsletters

- Council Reports and Society Forms

- SRR Membership

- Symposia Presentations

- Members Newsletter

- Business Minutes

- Search for:

GUIDANCE ON SUBMISSION OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH ABSTRACTS

General guidance

Authors should refer to the general information and guidelines contained in the Society’s “Guidance for Submission of Abstracts”. The general guidance therein applies to qualitative research abstracts. This includes the maximum permitted limit of 250 words, and the instruction that abstracts should be structured. In keeping with all submissions to the Society, subsequent presentation must reflect and elaborate on the abstract. Research studies or findings not referred to in the abstract should not be presented.

This document contains specific guidance on the content of qualitative research abstracts.

How guidance on content is to be applied by authors and Council.

Council recognises that the nature of qualitative research makes its comprehensive communication within short abstracts a challenge. Therefore, whilst the key areas to be included within abstracts are set out below, it is recognised that emphasis on each area will vary in different cases, and that not every listed sub-area will be covered. Certain elements are likely to receive greater attention at the time of presentation than within the abstract. In particular, presentation of the paper should include sufficient empirical data to allow judgement of the conclusions drawn.

Content of abstracts

- Research question/objective and design: clear statement of the research question/objective and its relevance. Methodological or theoretical perspectives should be clearly outlined.

- Population and sampling: who the subjects were and what sampling strategies were used .

- Methods of data collection: clear exposition of data collection: access, selection, method of collection, type of data, relationship of researcher to subjects/setting (what data were collected, from where/whom, by whom)

- Quality of data and analysis: strategies to enhance quality of data analysis e.g. triangulation, respondent validation; and to enhance validity e.g. attention to negative cases, consideration of alternative explanations, team analysis, peer review panels

- Application of critical thinking to analysis: attention to the influence of the researcher on data collected and on analysis. Critical approach to the status of data collected

- Theoretical and empirical context: evidence that design and analysis take into account and add to previous knowledge

- Conclusions: justified in relation to data collected, sufficient original data presented to substantiate interpretations, reasoned consideration of transferability to groups/settings beyond those studied

Username or email address *

Password *

Remember me Log in

Lost your password?

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper Abstract – Writing Guide and Examples

Research Paper Abstract – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Paper Abstract

Research Paper Abstract is a brief summary of a research pape r that describes the study’s purpose, methods, findings, and conclusions . It is often the first section of the paper that readers encounter, and its purpose is to provide a concise and accurate overview of the paper’s content. The typical length of an abstract is usually around 150-250 words, and it should be written in a concise and clear manner.

Research Paper Abstract Structure

The structure of a research paper abstract usually includes the following elements:

- Background or Introduction: Briefly describe the problem or research question that the study addresses.

- Methods : Explain the methodology used to conduct the study, including the participants, materials, and procedures.

- Results : Summarize the main findings of the study, including statistical analyses and key outcomes.

- Conclusions : Discuss the implications of the study’s findings and their significance for the field, as well as any limitations or future directions for research.

- Keywords : List a few keywords that describe the main topics or themes of the research.

How to Write Research Paper Abstract

Here are the steps to follow when writing a research paper abstract:

- Start by reading your paper: Before you write an abstract, you should have a complete understanding of your paper. Read through the paper carefully, making sure you understand the purpose, methods, results, and conclusions.

- Identify the key components : Identify the key components of your paper, such as the research question, methods used, results obtained, and conclusion reached.

- Write a draft: Write a draft of your abstract, using concise and clear language. Make sure to include all the important information, but keep it short and to the point. A good rule of thumb is to keep your abstract between 150-250 words.

- Use clear and concise language : Use clear and concise language to explain the purpose of your study, the methods used, the results obtained, and the conclusions drawn.

- Emphasize your findings: Emphasize your findings in the abstract, highlighting the key results and the significance of your study.

- Revise and edit: Once you have a draft, revise and edit it to ensure that it is clear, concise, and free from errors.

- Check the formatting: Finally, check the formatting of your abstract to make sure it meets the requirements of the journal or conference where you plan to submit it.

Research Paper Abstract Examples

Research Paper Abstract Examples could be following:

Title : “The Effectiveness of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Treating Anxiety Disorders: A Meta-Analysis”

Abstract : This meta-analysis examines the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in treating anxiety disorders. Through the analysis of 20 randomized controlled trials, we found that CBT is a highly effective treatment for anxiety disorders, with large effect sizes across a range of anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder. Our findings support the use of CBT as a first-line treatment for anxiety disorders and highlight the importance of further research to identify the mechanisms underlying its effectiveness.

Title : “Exploring the Role of Parental Involvement in Children’s Education: A Qualitative Study”

Abstract : This qualitative study explores the role of parental involvement in children’s education. Through in-depth interviews with 20 parents of children in elementary school, we found that parental involvement takes many forms, including volunteering in the classroom, helping with homework, and communicating with teachers. We also found that parental involvement is influenced by a range of factors, including parent and child characteristics, school culture, and socio-economic status. Our findings suggest that schools and educators should prioritize building strong partnerships with parents to support children’s academic success.

Title : “The Impact of Exercise on Cognitive Function in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis”

Abstract : This paper presents a systematic review and meta-analysis of the existing literature on the impact of exercise on cognitive function in older adults. Through the analysis of 25 randomized controlled trials, we found that exercise is associated with significant improvements in cognitive function, particularly in the domains of executive function and attention. Our findings highlight the potential of exercise as a non-pharmacological intervention to support cognitive health in older adults.

When to Write Research Paper Abstract

The abstract of a research paper should typically be written after you have completed the main body of the paper. This is because the abstract is intended to provide a brief summary of the key points and findings of the research, and you can’t do that until you have completed the research and written about it in detail.

Once you have completed your research paper, you can begin writing your abstract. It is important to remember that the abstract should be a concise summary of your research paper, and should be written in a way that is easy to understand for readers who may not have expertise in your specific area of research.

Purpose of Research Paper Abstract

The purpose of a research paper abstract is to provide a concise summary of the key points and findings of a research paper. It is typically a brief paragraph or two that appears at the beginning of the paper, before the introduction, and is intended to give readers a quick overview of the paper’s content.

The abstract should include a brief statement of the research problem, the methods used to investigate the problem, the key results and findings, and the main conclusions and implications of the research. It should be written in a clear and concise manner, avoiding jargon and technical language, and should be understandable to a broad audience.

The abstract serves as a way to quickly and easily communicate the main points of a research paper to potential readers, such as academics, researchers, and students, who may be looking for information on a particular topic. It can also help researchers determine whether a paper is relevant to their own research interests and whether they should read the full paper.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Research Paper Title – Writing Guide and Example

Research Paper Introduction – Writing Guide and...

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 3. The Abstract

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

An abstract summarizes, usually in one paragraph of 300 words or less, the major aspects of the entire paper in a prescribed sequence that includes: 1) the overall purpose of the study and the research problem(s) you investigated; 2) the basic design of the study; 3) major findings or trends found as a result of your analysis; and, 4) a brief summary of your interpretations and conclusions.

Writing an Abstract. The Writing Center. Clarion University, 2009; Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper. The Writing Center, University of Wisconsin, Madison; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-first Century . Oxford, UK: Chandos Publishing, 2010;

Importance of a Good Abstract

Sometimes your professor will ask you to include an abstract, or general summary of your work, with your research paper. The abstract allows you to elaborate upon each major aspect of the paper and helps readers decide whether they want to read the rest of the paper. Therefore, enough key information [e.g., summary results, observations, trends, etc.] must be included to make the abstract useful to someone who may want to examine your work.

How do you know when you have enough information in your abstract? A simple rule-of-thumb is to imagine that you are another researcher doing a similar study. Then ask yourself: if your abstract was the only part of the paper you could access, would you be happy with the amount of information presented there? Does it tell the whole story about your study? If the answer is "no" then the abstract likely needs to be revised.

Farkas, David K. “A Scheme for Understanding and Writing Summaries.” Technical Communication 67 (August 2020): 45-60; How to Write a Research Abstract. Office of Undergraduate Research. University of Kentucky; Staiger, David L. “What Today’s Students Need to Know about Writing Abstracts.” International Journal of Business Communication January 3 (1966): 29-33; Swales, John M. and Christine B. Feak. Abstracts and the Writing of Abstracts . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2009.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types of Abstracts

To begin, you need to determine which type of abstract you should include with your paper. There are four general types.

Critical Abstract A critical abstract provides, in addition to describing main findings and information, a judgment or comment about the study’s validity, reliability, or completeness. The researcher evaluates the paper and often compares it with other works on the same subject. Critical abstracts are generally 400-500 words in length due to the additional interpretive commentary. These types of abstracts are used infrequently.

Descriptive Abstract A descriptive abstract indicates the type of information found in the work. It makes no judgments about the work, nor does it provide results or conclusions of the research. It does incorporate key words found in the text and may include the purpose, methods, and scope of the research. Essentially, the descriptive abstract only describes the work being summarized. Some researchers consider it an outline of the work, rather than a summary. Descriptive abstracts are usually very short, 100 words or less. Informative Abstract The majority of abstracts are informative. While they still do not critique or evaluate a work, they do more than describe it. A good informative abstract acts as a surrogate for the work itself. That is, the researcher presents and explains all the main arguments and the important results and evidence in the paper. An informative abstract includes the information that can be found in a descriptive abstract [purpose, methods, scope] but it also includes the results and conclusions of the research and the recommendations of the author. The length varies according to discipline, but an informative abstract is usually no more than 300 words in length.

Highlight Abstract A highlight abstract is specifically written to attract the reader’s attention to the study. No pretense is made of there being either a balanced or complete picture of the paper and, in fact, incomplete and leading remarks may be used to spark the reader’s interest. In that a highlight abstract cannot stand independent of its associated article, it is not a true abstract and, therefore, rarely used in academic writing.

II. Writing Style

Use the active voice when possible , but note that much of your abstract may require passive sentence constructions. Regardless, write your abstract using concise, but complete, sentences. Get to the point quickly and always use the past tense because you are reporting on a study that has been completed.

Abstracts should be formatted as a single paragraph in a block format and with no paragraph indentations. In most cases, the abstract page immediately follows the title page. Do not number the page. Rules set forth in writing manual vary but, in general, you should center the word "Abstract" at the top of the page with double spacing between the heading and the abstract. The final sentences of an abstract concisely summarize your study’s conclusions, implications, or applications to practice and, if appropriate, can be followed by a statement about the need for additional research revealed from the findings.

Composing Your Abstract

Although it is the first section of your paper, the abstract should be written last since it will summarize the contents of your entire paper. A good strategy to begin composing your abstract is to take whole sentences or key phrases from each section of the paper and put them in a sequence that summarizes the contents. Then revise or add connecting phrases or words to make the narrative flow clearly and smoothly. Note that statistical findings should be reported parenthetically [i.e., written in parentheses].

Before handing in your final paper, check to make sure that the information in the abstract completely agrees with what you have written in the paper. Think of the abstract as a sequential set of complete sentences describing the most crucial information using the fewest necessary words. The abstract SHOULD NOT contain:

- A catchy introductory phrase, provocative quote, or other device to grab the reader's attention,

- Lengthy background or contextual information,

- Redundant phrases, unnecessary adverbs and adjectives, and repetitive information;

- Acronyms or abbreviations,

- References to other literature [say something like, "current research shows that..." or "studies have indicated..."],

- Using ellipticals [i.e., ending with "..."] or incomplete sentences,

- Jargon or terms that may be confusing to the reader,

- Citations to other works, and

- Any sort of image, illustration, figure, or table, or references to them.

Abstract. Writing Center. University of Kansas; Abstract. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Abstracts. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Borko, Harold and Seymour Chatman. "Criteria for Acceptable Abstracts: A Survey of Abstracters' Instructions." American Documentation 14 (April 1963): 149-160; Abstracts. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Hartley, James and Lucy Betts. "Common Weaknesses in Traditional Abstracts in the Social Sciences." Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 60 (October 2009): 2010-2018; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-first Century. Oxford, UK: Chandos Publishing, 2010; Procter, Margaret. The Abstract. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Riordan, Laura. “Mastering the Art of Abstracts.” The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 115 (January 2015 ): 41-47; Writing Report Abstracts. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing Abstracts. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-First Century . Oxford, UK: 2010; Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper. The Writing Center, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Writing Tip

Never Cite Just the Abstract!

Citing to just a journal article's abstract does not confirm for the reader that you have conducted a thorough or reliable review of the literature. If the full-text is not available, go to the USC Libraries main page and enter the title of the article [NOT the title of the journal]. If the Libraries have a subscription to the journal, the article should appear with a link to the full-text or to the journal publisher page where you can get the article. If the article does not appear, try searching Google Scholar using the link on the USC Libraries main page. If you still can't find the article after doing this, contact a librarian or you can request it from our free i nterlibrary loan and document delivery service .

- << Previous: Research Process Video Series

- Next: Executive Summary >>

- Last Updated: Apr 24, 2024 10:51 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write an Abstract

Expedite peer review, increase search-ability, and set the tone for your study

The abstract is your chance to let your readers know what they can expect from your article. Learn how to write a clear, and concise abstract that will keep your audience reading.

How your abstract impacts editorial evaluation and future readership

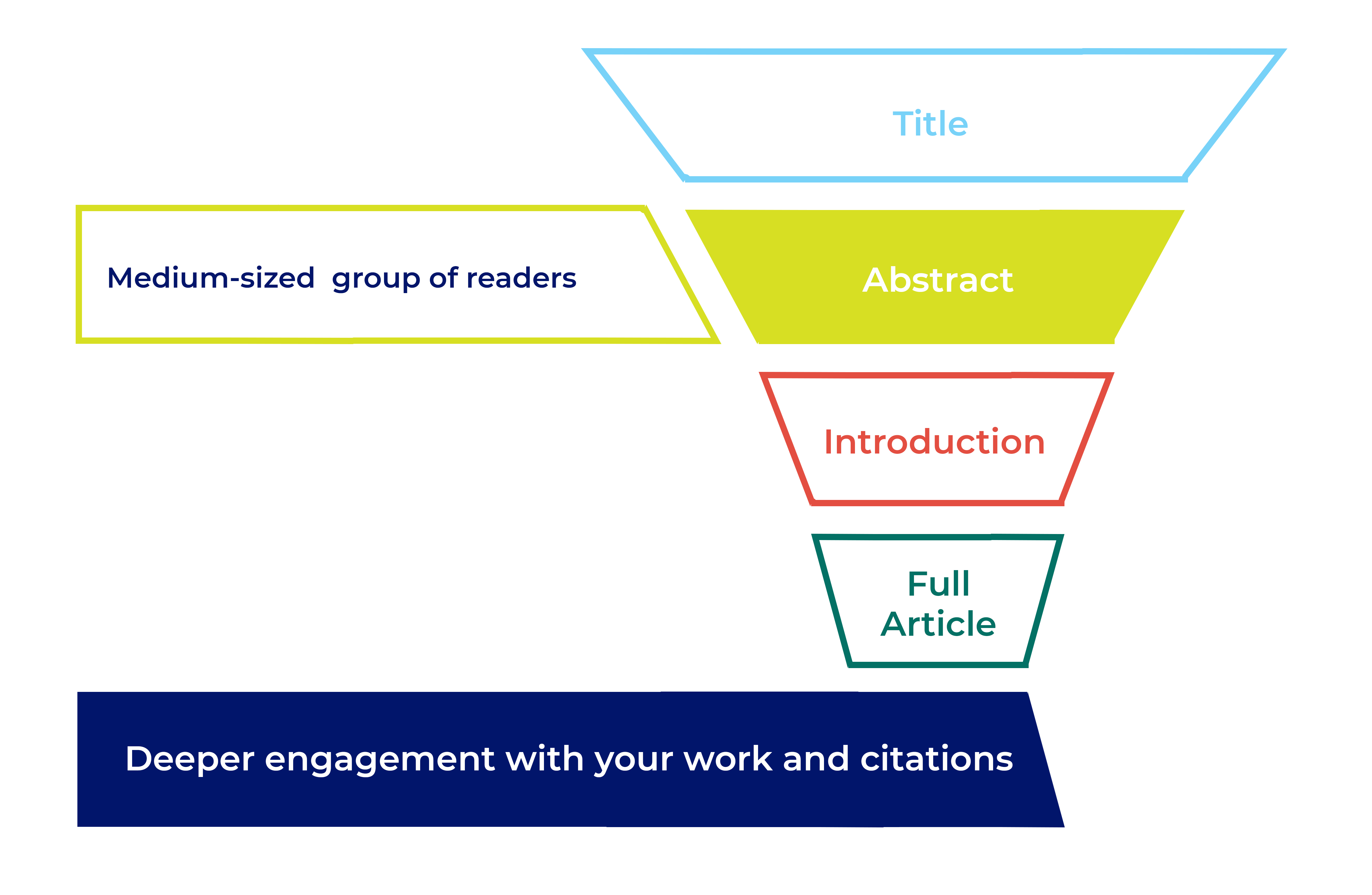

After the title , the abstract is the second-most-read part of your article. A good abstract can help to expedite peer review and, if your article is accepted for publication, it’s an important tool for readers to find and evaluate your work. Editors use your abstract when they first assess your article. Prospective reviewers see it when they decide whether to accept an invitation to review. Once published, the abstract gets indexed in PubMed and Google Scholar , as well as library systems and other popular databases. Like the title, your abstract influences keyword search results. Readers will use it to decide whether to read the rest of your article. Other researchers will use it to evaluate your work for inclusion in systematic reviews and meta-analysis. It should be a concise standalone piece that accurately represents your research.

What to include in an abstract

The main challenge you’ll face when writing your abstract is keeping it concise AND fitting in all the information you need. Depending on your subject area the journal may require a structured abstract following specific headings. A structured abstract helps your readers understand your study more easily. If your journal doesn’t require a structured abstract it’s still a good idea to follow a similar format, just present the abstract as one paragraph without headings.

Background or Introduction – What is currently known? Start with a brief, 2 or 3 sentence, introduction to the research area.

Objectives or Aims – What is the study and why did you do it? Clearly state the research question you’re trying to answer.

Methods – What did you do? Explain what you did and how you did it. Include important information about your methods, but avoid the low-level specifics. Some disciplines have specific requirements for abstract methods.

- CONSORT for randomized trials.

- STROBE for observational studies

- PRISMA for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Results – What did you find? Briefly give the key findings of your study. Include key numeric data (including confidence intervals or p values), where possible.

Conclusions – What did you conclude? Tell the reader why your findings matter, and what this could mean for the ‘bigger picture’ of this area of research.

Writing tips

The main challenge you may find when writing your abstract is keeping it concise AND convering all the information you need to.

- Keep it concise and to the point. Most journals have a maximum word count, so check guidelines before you write the abstract to save time editing it later.

- Write for your audience. Are they specialists in your specific field? Are they cross-disciplinary? Are they non-specialists? If you’re writing for a general audience, or your research could be of interest to the public keep your language as straightforward as possible. If you’re writing in English, do remember that not all of your readers will necessarily be native English speakers.

- Focus on key results, conclusions and take home messages.

- Write your paper first, then create the abstract as a summary.

- Check the journal requirements before you write your abstract, eg. required subheadings.

- Include keywords or phrases to help readers search for your work in indexing databases like PubMed or Google Scholar.

- Double and triple check your abstract for spelling and grammar errors. These kind of errors can give potential reviewers the impression that your research isn’t sound, and can make it easier to find reviewers who accept the invitation to review your manuscript. Your abstract should be a taste of what is to come in the rest of your article.

Don’t

- Sensationalize your research.

- Speculate about where this research might lead in the future.

- Use abbreviations or acronyms (unless absolutely necessary or unless they’re widely known, eg. DNA).

- Repeat yourself unnecessarily, eg. “Methods: We used X technique. Results: Using X technique, we found…”

- Contradict anything in the rest of your manuscript.

- Include content that isn’t also covered in the main manuscript.

- Include citations or references.

Tip: How to edit your work

Editing is challenging, especially if you are acting as both a writer and an editor. Read our guidelines for advice on how to refine your work, including useful tips for setting your intentions, re-review, and consultation with colleagues.

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Neurol Res Pract

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

Loraine busetto.

1 Department of Neurology, Heidelberg University Hospital, Im Neuenheimer Feld 400, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany

Wolfgang Wick

2 Clinical Cooperation Unit Neuro-Oncology, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany

Christoph Gumbinger

Associated data.

Not applicable.

This paper aims to provide an overview of the use and assessment of qualitative research methods in the health sciences. Qualitative research can be defined as the study of the nature of phenomena and is especially appropriate for answering questions of why something is (not) observed, assessing complex multi-component interventions, and focussing on intervention improvement. The most common methods of data collection are document study, (non-) participant observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. For data analysis, field-notes and audio-recordings are transcribed into protocols and transcripts, and coded using qualitative data management software. Criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, sampling strategies, piloting, co-coding, member-checking and stakeholder involvement can be used to enhance and assess the quality of the research conducted. Using qualitative in addition to quantitative designs will equip us with better tools to address a greater range of research problems, and to fill in blind spots in current neurological research and practice.

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of qualitative research methods, including hands-on information on how they can be used, reported and assessed. This article is intended for beginning qualitative researchers in the health sciences as well as experienced quantitative researchers who wish to broaden their understanding of qualitative research.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as “the study of the nature of phenomena”, including “their quality, different manifestations, the context in which they appear or the perspectives from which they can be perceived” , but excluding “their range, frequency and place in an objectively determined chain of cause and effect” [ 1 ]. This formal definition can be complemented with a more pragmatic rule of thumb: qualitative research generally includes data in form of words rather than numbers [ 2 ].

Why conduct qualitative research?

Because some research questions cannot be answered using (only) quantitative methods. For example, one Australian study addressed the issue of why patients from Aboriginal communities often present late or not at all to specialist services offered by tertiary care hospitals. Using qualitative interviews with patients and staff, it found one of the most significant access barriers to be transportation problems, including some towns and communities simply not having a bus service to the hospital [ 3 ]. A quantitative study could have measured the number of patients over time or even looked at possible explanatory factors – but only those previously known or suspected to be of relevance. To discover reasons for observed patterns, especially the invisible or surprising ones, qualitative designs are needed.

While qualitative research is common in other fields, it is still relatively underrepresented in health services research. The latter field is more traditionally rooted in the evidence-based-medicine paradigm, as seen in " research that involves testing the effectiveness of various strategies to achieve changes in clinical practice, preferably applying randomised controlled trial study designs (...) " [ 4 ]. This focus on quantitative research and specifically randomised controlled trials (RCT) is visible in the idea of a hierarchy of research evidence which assumes that some research designs are objectively better than others, and that choosing a "lesser" design is only acceptable when the better ones are not practically or ethically feasible [ 5 , 6 ]. Others, however, argue that an objective hierarchy does not exist, and that, instead, the research design and methods should be chosen to fit the specific research question at hand – "questions before methods" [ 2 , 7 – 9 ]. This means that even when an RCT is possible, some research problems require a different design that is better suited to addressing them. Arguing in JAMA, Berwick uses the example of rapid response teams in hospitals, which he describes as " a complex, multicomponent intervention – essentially a process of social change" susceptible to a range of different context factors including leadership or organisation history. According to him, "[in] such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn. Critics who use it as a truth standard in this context are incorrect" [ 8 ] . Instead of limiting oneself to RCTs, Berwick recommends embracing a wider range of methods , including qualitative ones, which for "these specific applications, (...) are not compromises in learning how to improve; they are superior" [ 8 ].

Research problems that can be approached particularly well using qualitative methods include assessing complex multi-component interventions or systems (of change), addressing questions beyond “what works”, towards “what works for whom when, how and why”, and focussing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation [ 7 , 9 – 12 ]. Using qualitative methods can also help shed light on the “softer” side of medical treatment. For example, while quantitative trials can measure the costs and benefits of neuro-oncological treatment in terms of survival rates or adverse effects, qualitative research can help provide a better understanding of patient or caregiver stress, visibility of illness or out-of-pocket expenses.

How to conduct qualitative research?

Given that qualitative research is characterised by flexibility, openness and responsivity to context, the steps of data collection and analysis are not as separate and consecutive as they tend to be in quantitative research [ 13 , 14 ]. As Fossey puts it : “sampling, data collection, analysis and interpretation are related to each other in a cyclical (iterative) manner, rather than following one after another in a stepwise approach” [ 15 ]. The researcher can make educated decisions with regard to the choice of method, how they are implemented, and to which and how many units they are applied [ 13 ]. As shown in Fig. 1 , this can involve several back-and-forth steps between data collection and analysis where new insights and experiences can lead to adaption and expansion of the original plan. Some insights may also necessitate a revision of the research question and/or the research design as a whole. The process ends when saturation is achieved, i.e. when no relevant new information can be found (see also below: sampling and saturation). For reasons of transparency, it is essential for all decisions as well as the underlying reasoning to be well-documented.

Iterative research process

While it is not always explicitly addressed, qualitative methods reflect a different underlying research paradigm than quantitative research (e.g. constructivism or interpretivism as opposed to positivism). The choice of methods can be based on the respective underlying substantive theory or theoretical framework used by the researcher [ 2 ].

Data collection

The methods of qualitative data collection most commonly used in health research are document study, observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups [ 1 , 14 , 16 , 17 ].

Document study

Document study (also called document analysis) refers to the review by the researcher of written materials [ 14 ]. These can include personal and non-personal documents such as archives, annual reports, guidelines, policy documents, diaries or letters.

Observations

Observations are particularly useful to gain insights into a certain setting and actual behaviour – as opposed to reported behaviour or opinions [ 13 ]. Qualitative observations can be either participant or non-participant in nature. In participant observations, the observer is part of the observed setting, for example a nurse working in an intensive care unit [ 18 ]. In non-participant observations, the observer is “on the outside looking in”, i.e. present in but not part of the situation, trying not to influence the setting by their presence. Observations can be planned (e.g. for 3 h during the day or night shift) or ad hoc (e.g. as soon as a stroke patient arrives at the emergency room). During the observation, the observer takes notes on everything or certain pre-determined parts of what is happening around them, for example focusing on physician-patient interactions or communication between different professional groups. Written notes can be taken during or after the observations, depending on feasibility (which is usually lower during participant observations) and acceptability (e.g. when the observer is perceived to be judging the observed). Afterwards, these field notes are transcribed into observation protocols. If more than one observer was involved, field notes are taken independently, but notes can be consolidated into one protocol after discussions. Advantages of conducting observations include minimising the distance between the researcher and the researched, the potential discovery of topics that the researcher did not realise were relevant and gaining deeper insights into the real-world dimensions of the research problem at hand [ 18 ].

Semi-structured interviews

Hijmans & Kuyper describe qualitative interviews as “an exchange with an informal character, a conversation with a goal” [ 19 ]. Interviews are used to gain insights into a person’s subjective experiences, opinions and motivations – as opposed to facts or behaviours [ 13 ]. Interviews can be distinguished by the degree to which they are structured (i.e. a questionnaire), open (e.g. free conversation or autobiographical interviews) or semi-structured [ 2 , 13 ]. Semi-structured interviews are characterized by open-ended questions and the use of an interview guide (or topic guide/list) in which the broad areas of interest, sometimes including sub-questions, are defined [ 19 ]. The pre-defined topics in the interview guide can be derived from the literature, previous research or a preliminary method of data collection, e.g. document study or observations. The topic list is usually adapted and improved at the start of the data collection process as the interviewer learns more about the field [ 20 ]. Across interviews the focus on the different (blocks of) questions may differ and some questions may be skipped altogether (e.g. if the interviewee is not able or willing to answer the questions or for concerns about the total length of the interview) [ 20 ]. Qualitative interviews are usually not conducted in written format as it impedes on the interactive component of the method [ 20 ]. In comparison to written surveys, qualitative interviews have the advantage of being interactive and allowing for unexpected topics to emerge and to be taken up by the researcher. This can also help overcome a provider or researcher-centred bias often found in written surveys, which by nature, can only measure what is already known or expected to be of relevance to the researcher. Interviews can be audio- or video-taped; but sometimes it is only feasible or acceptable for the interviewer to take written notes [ 14 , 16 , 20 ].

Focus groups

Focus groups are group interviews to explore participants’ expertise and experiences, including explorations of how and why people behave in certain ways [ 1 ]. Focus groups usually consist of 6–8 people and are led by an experienced moderator following a topic guide or “script” [ 21 ]. They can involve an observer who takes note of the non-verbal aspects of the situation, possibly using an observation guide [ 21 ]. Depending on researchers’ and participants’ preferences, the discussions can be audio- or video-taped and transcribed afterwards [ 21 ]. Focus groups are useful for bringing together homogeneous (to a lesser extent heterogeneous) groups of participants with relevant expertise and experience on a given topic on which they can share detailed information [ 21 ]. Focus groups are a relatively easy, fast and inexpensive method to gain access to information on interactions in a given group, i.e. “the sharing and comparing” among participants [ 21 ]. Disadvantages include less control over the process and a lesser extent to which each individual may participate. Moreover, focus group moderators need experience, as do those tasked with the analysis of the resulting data. Focus groups can be less appropriate for discussing sensitive topics that participants might be reluctant to disclose in a group setting [ 13 ]. Moreover, attention must be paid to the emergence of “groupthink” as well as possible power dynamics within the group, e.g. when patients are awed or intimidated by health professionals.

Choosing the “right” method

As explained above, the school of thought underlying qualitative research assumes no objective hierarchy of evidence and methods. This means that each choice of single or combined methods has to be based on the research question that needs to be answered and a critical assessment with regard to whether or to what extent the chosen method can accomplish this – i.e. the “fit” between question and method [ 14 ]. It is necessary for these decisions to be documented when they are being made, and to be critically discussed when reporting methods and results.