Breech Position: What It Means if Your Baby Is Breech

Medical review policy, latest update:.

Medically reviewed for accuracy.

What does it mean if a baby is breech?

What are the different types of breech positions, what causes a baby to be breech, recommended reading, how can you tell if your baby is in a breech position, what does it mean to turn a breech baby, how can you turn a breech baby, how does labor usually start with a breech baby.

If your cervix dilates too slowly, if your baby doesn’t move down the birth canal steadily or if other problems arise, you’ll likely have a C-section. Talk your options over with your practitioner now to be prepared. Remember that though you may feel disappointed things didn’t turn out exactly as you envisioned, these feelings will melt away once your bundle of joy safely enters the world.

Updates history

Jump to your week of pregnancy, trending on what to expect, signs of labor, pregnancy calculator, ⚠️ you can't see this cool content because you have ad block enabled., top 1,000 baby girl names in the u.s., top 1,000 baby boy names in the u.s., braxton hicks contractions and false labor.

- Pregnancy Classes

Breech Births

In the last weeks of pregnancy, a baby usually moves so his or her head is positioned to come out of the vagina first during birth. This is called a vertex presentation. A breech presentation occurs when the baby’s buttocks, feet, or both are positioned to come out first during birth. This happens in 3–4% of full-term births.

What are the different types of breech birth presentations?

- Complete breech: Here, the buttocks are pointing downward with the legs folded at the knees and feet near the buttocks.

- Frank breech: In this position, the baby’s buttocks are aimed at the birth canal with its legs sticking straight up in front of his or her body and the feet near the head.

- Footling breech: In this position, one or both of the baby’s feet point downward and will deliver before the rest of the body.

What causes a breech presentation?

The causes of breech presentations are not fully understood. However, the data show that breech birth is more common when:

- You have been pregnant before

- In pregnancies of multiples

- When there is a history of premature delivery

- When the uterus has too much or too little amniotic fluid

- When there is an abnormally shaped uterus or a uterus with abnormal growths, such as fibroids

- The placenta covers all or part of the opening of the uterus placenta previa

How is a breech presentation diagnosed?

A few weeks prior to the due date, the health care provider will place her hands on the mother’s lower abdomen to locate the baby’s head, back, and buttocks. If it appears that the baby might be in a breech position, they can use ultrasound or pelvic exam to confirm the position. Special x-rays can also be used to determine the baby’s position and the size of the pelvis to determine if a vaginal delivery of a breech baby can be safely attempted.

Can a breech presentation mean something is wrong?

Even though most breech babies are born healthy, there is a slightly elevated risk for certain problems. Birth defects are slightly more common in breech babies and the defect might be the reason that the baby failed to move into the right position prior to delivery.

Can a breech presentation be changed?

It is preferable to try to turn a breech baby between the 32nd and 37th weeks of pregnancy . The methods of turning a baby will vary and the success rate for each method can also vary. It is best to discuss the options with the health care provider to see which method she recommends.

Medical Techniques

External Cephalic Version (EVC) is a non-surgical technique to move the baby in the uterus. In this procedure, a medication is given to help relax the uterus. There might also be the use of an ultrasound to determine the position of the baby, the location of the placenta and the amount of amniotic fluid in the uterus.

Gentle pushing on the lower abdomen can turn the baby into the head-down position. Throughout the external version the baby’s heartbeat will be closely monitored so that if a problem develops, the health care provider will immediately stop the procedure. ECV usually is done near a delivery room so if a problem occurs, a cesarean delivery can be performed quickly. The external version has a high success rate and can be considered if you have had a previous cesarean delivery.

ECV will not be tried if:

- You are carrying more than one fetus

- There are concerns about the health of the fetus

- You have certain abnormalities of the reproductive system

- The placenta is in the wrong place

- The placenta has come away from the wall of the uterus ( placental abruption )

Complications of EVC include:

- Prelabor rupture of membranes

- Changes in the fetus’s heart rate

- Placental abruption

- Preterm labor

Vaginal delivery versus cesarean for breech birth?

Most health care providers do not believe in attempting a vaginal delivery for a breech position. However, some will delay making a final decision until the woman is in labor. The following conditions are considered necessary in order to attempt a vaginal birth:

- The baby is full-term and in the frank breech presentation

- The baby does not show signs of distress while its heart rate is closely monitored.

- The process of labor is smooth and steady with the cervix widening as the baby descends.

- The health care provider estimates that the baby is not too big or the mother’s pelvis too narrow for the baby to pass safely through the birth canal.

- Anesthesia is available and a cesarean delivery possible on short notice

What are the risks and complications of a vaginal delivery?

In a breech birth, the baby’s head is the last part of its body to emerge making it more difficult to ease it through the birth canal. Sometimes forceps are used to guide the baby’s head out of the birth canal. Another potential problem is cord prolapse . In this situation the umbilical cord is squeezed as the baby moves toward the birth canal, thus slowing the baby’s supply of oxygen and blood. In a vaginal breech delivery, electronic fetal monitoring will be used to monitor the baby’s heartbeat throughout the course of labor. Cesarean delivery may be an option if signs develop that the baby may be in distress.

When is a cesarean delivery used with a breech presentation?

Most health care providers recommend a cesarean delivery for all babies in a breech position, especially babies that are premature. Since premature babies are small and more fragile, and because the head of a premature baby is relatively larger in proportion to its body, the baby is unlikely to stretch the cervix as much as a full-term baby. This means that there might be less room for the head to emerge.

Want to Know More?

- Creating Your Birth Plan

- Labor & Birth Terms to Know

- Cesarean Birth After Care

Compiled using information from the following sources:

- ACOG: If Your Baby is Breech

- William’s Obstetrics Twenty-Second Ed. Cunningham, F. Gary, et al, Ch. 24.

- Danforth’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Ninth Ed. Scott, James R., et al, Ch. 21.

BLOG CATEGORIES

- Can I get pregnant if… ? 3

- Child Adoption 19

- Fertility 54

- Pregnancy Loss 11

- Breastfeeding 29

- Changes In Your Body 5

- Cord Blood 4

- Genetic Disorders & Birth Defects 17

- Health & Nutrition 2

- Is it Safe While Pregnant 54

- Labor and Birth 65

- Multiple Births 10

- Planning and Preparing 24

- Pregnancy Complications 68

- Pregnancy Concerns 62

- Pregnancy Health and Wellness 149

- Pregnancy Products & Tests 8

- Pregnancy Supplements & Medications 14

- The First Year 41

- Week by Week Newsletter 40

- Your Developing Baby 16

- Options for Unplanned Pregnancy 18

- Paternity Tests 2

- Pregnancy Symptoms 5

- Prenatal Testing 16

- The Bumpy Truth Blog 7

- Uncategorized 4

- Abstinence 3

- Birth Control Pills, Patches & Devices 21

- Women's Health 34

- Thank You for Your Donation

- Unplanned Pregnancy

- Getting Pregnant

- Healthy Pregnancy

- Privacy Policy

Share this post:

Similar post.

Episiotomy: Advantages & Complications

Retained Placenta

What is Dilation in Pregnancy?

Track your baby’s development, subscribe to our week-by-week pregnancy newsletter.

- The Bumpy Truth Blog

- Fertility Products Resource Guide

Pregnancy Tools

- Ovulation Calendar

- Baby Names Directory

- Pregnancy Due Date Calculator

- Pregnancy Quiz

Pregnancy Journeys

- Partner With Us

- Corporate Sponsors

- Third Trimester

- Labor & Delivery

What Does It Mean to Have a Breech Baby?

You’re almost full term and the finish line is approaching, when suddenly your OB or midwife informs you that baby is breech—plot twist! If baby is in a breech position, it means their feet or bottom is pointed toward your cervix rather than their head. You’ve just encountered an early example of a universal truth in parenting: Few things ever go as perfectly as you planned.

A breech birth often means a c-section delivery is in store for you, and that can feel disappointing and worrisome, especially if you’ve been hoping to deliver vaginally. Deep breath— you may still have options; your doctor will talk you through everything well before the big day comes. In the meantime, it’s helpful to get a better grasp on all things breech baby. Want to know how to tell if baby is breech, what the position means for your pregnancy, how it affects delivery and ways your doctor (and you!) can try to turn baby? Read on for the full lowdown.

What Is a Breech Baby?

In the last few weeks of pregnancy, most babies move in the womb so that their heads are facing down, positioned to come out of the vagina first during delivery. But if baby is breech, their head is not approaching the birth canal; rather, it’s their feet or bottom that’s poised to come out first.

Types of breech positions

There are three different types of breech positions, according to the American Pregnancy Association :

- Complete. Baby’s buttocks are pointing down and legs are crossed beneath it

- Frank. Baby’s bottom is positioned down and legs are pointed up toward the head

- Footling. Baby has one leg pointed toward the cervix, poised to deliver before the rest of their body. “There’s also a double footling breech, where the baby’s feet and legs are facing down toward the cervix,” says Elizabeth Deckers , MD, director of the maternal quality and safety program at Hartford HealthCare.

Baby could also be in a transverse lie position (occasionally referred to as a transverse breech position). This means that they’re horizontal across the uterus instead of vertical.

What percentage of babies are breech?

According to the American Pregnancy Association, approximately 1 out of every 25 full-term births involves a baby in a breech position. That means roughly 4 percent of babies have their bottom and/or feet pointed down toward the birth canal.

Why a Breech Position Can Be a Concern

Your doctor won’t be too concerned if baby is in a breech position throughout most of your pregnancy. In fact, it’s likely that at some point in your second or early third trimester, baby will be breech. At this early stage, though, baby is smaller and has more room to move around and turn, notes Deckers.

As baby grows and your due date nears, a breech position becomes slightly more concerning. For starters, there’s some evidence linking a breech presentation—and its tendency to reduce the amount of space in the womb—with hip dysplasia , a condition where the ball and socket joint of baby’s hip doesn’t properly form.

Your doctor or midwife may raise a red flag if baby is in breech position at 36 weeks or later. At this point, they’ll probably start talking about the potential need for a c-section. “Vaginal breech delivery is no longer commonly done in the US because about 20 years ago there was a large, well-designed trial that showed there was more risk to the fetus of going through a vaginal breech delivery versus being born by a c-section,” says Deckers. The trial showed that breech babies born vaginally were more likely to have fetal fractures and a harder time getting out of the birth canal, says Amber Samuel , MD, medical director of Obstetrix Maternal-Fetal Medicine Specialists of Houston. Deckers reiterates this, noting that most babies in the US identified as breech will be born via c-section, as doctors “believe it’s safer in the short run for baby.”

What Causes a Breech Pregnancy?

Don’t beat yourself up or worry that you did something wrong in pregnancy to put baby into a breech position. The truth is there’s usually no rhyme or reason to explain baby’s breech presentation, says Samuel. That said, if you have a uterine anomaly, where your uterus is wider at the top or generally more narrow, it may play a role, she says. “If the shape is abnormal, some babies get stuck,” she says. Having too much amniotic fluid around baby might also be a potential factor.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) lists other factors that might contribute to baby being breech: you’ve been pregnant before, you’re expecting twins or multiples, you have placenta previa (where your placenta is covering part of your uterine opening) or baby is preterm . Suffice it to say, though, that these potential breech baby causes are out of your control.

How to Tell If Baby Is Breech

You might be able to detect that baby is breech if you feel them kick low near your cervix or feel their head under your ribs, says Deckers. Samuel notes that some moms who’ve had babies before are really good at determining how and where they’re positioned.

Doctors gauge baby’s position by placing their hands on different parts of your belly to feel where fetal parts are, a technique known as Leopold’s maneuvers, explains Samuel. They may also perform a cervical exam to see if they can feel any presenting parts. Sometime around 36 or 37 weeks, they’ll confirm baby’s position with an ultrasound.

What to Expect from a Breech Pregnancy

You may not know if or when baby is in a breech position. Earlier on in your pregnancy, when they’re smaller and have more room in the womb, they may flip all around; roughly 20 percent of babies are breech at 28 weeks, says Samuel. If you discover that your little acrobat is breech at this stage, don’t panic; there’s still more than enough time for them to flip into the preferred position (and then possibly do a few more rotations).

Are breech babies more painful to carry?

The good news: Breech presentation doesn’t typically cause discomfort or pain during pregnancy, Samuel says. Pain is more likely related to “prior scar tissue, the size of your baby and your pregnancy history,” she adds.

What to Expect from a Breech Delivery

There is a possibility for a vaginal breech birth under the right circumstances. Deckers notes that you may be a candidate if baby is in a frank or complete breech presentation and your pelvic structure is adequate for vaginal birth—and if your hospital has guidelines in place for a planned vaginal breech delivery. Unfortunately, the risk of the umbilical cord falling through the cervix is too high with a double footling breech; there’s also a higher risk that baby will get stuck during delivery, which can cause birth asphyxia. Of course, you’ll also want to ensure that your doctor has a lot of experience with vaginal breech delivery and that your hospital will allow it.

If baby is in a breech position beyond 36 weeks and your doctor feels that a vaginal birth is too risky, they’ll likely recommend that you allow them to try turning baby— more on that soon . If that’s not successful, you’ll be scheduled for a c-section, says Samuel.

Having twins where one is breech changes the game a little too. If the baby that’s poised to come out first is breech, you’ll have to deliver via c-section, says Deckers. But if the first baby is head down and second is not, you and your OB have three options: deliver both via c-section; deliver the first baby vaginally and then attempt to turn the second one to deliver vaginally (if it’s unsuccessful, you’ll proceed with a c-section) or deliver the first vaginally and then do a breech extraction of the second baby (your OB will reach inside to grasp baby’s feet and pull them down.)

“The ability to do a safe breech extraction depends on the gestational age of the babies, how well the mother and babies are tolerating labor, the size of the babies and a provider with experience in performing this procedure,” says Deckers.

How to Turn a Breech Baby

Many parents want to have a vaginal birth; what’s more, they know that a c-section is a major surgery with inherent risks. To that end, before scheduling a c-section, most doctors will suggest trying an external cephalic version (ECV), which is an attempt to turn baby from the outside.

First you’ll be given medication to relax your uterus; don’t worry, your doctor will continually monitor baby. “One hand elevates the fetal breech out of the pelvis and you push up and away from the pelvis,” says Samuel. “The other hand is on the back of baby’s head to induce them to turn over—it looks like an aggressive belly massage.”

Your doctor will push baby forward before attempting a backward roll. “You can tell pretty early into it whether it’s going to work or not—some babies are ready to flip, some aren’t,” says Samuel. “We try not to struggle too much with it.”

External cephalic versions are successful roughly 58 percent of the time, says Deckers, although there’s always the chance that baby will flip back to breech on their own. If the turning is successful and you’re at 39 weeks, you can choose to be induced. If it didn’t work, you’ll be scheduled for a c-section. ECVs should only be performed in hospitals equipped to perform emergency c-sections ; risks of the procedure, which are rare, include bleeding from the placenta, rupture of membranes and going into labor, says Samuel.

It’s also worth noting that not every mom is a candidate for an EVC. If you’re having multiples or there’s a problem with placental position, an EVC is too risky, according to the ACOG.

Safe ways to try to turn a breech baby at home

If you prefer to try to make things happen on your own, there are a few things you can do to help turn a breech baby from the comfort of your home. Deckers notes, though, that research on DIY techniques hasn’t provided strong enough evidence to prove that they really work.

A little bit of gentle prenatal yoga may help. One pose to practice? Deckers says some moms try “a head down/knee-to-chest position.” You can also assume a few different sleeping positions to turn a breech baby: “Mothers can try positional things like elevating your pelvis,” she says. Finally, Deckers mentions two Eastern medicine techniques that many moms actively seek out: acupuncture and moxibustion, a therapy that involves waving burning dried plant bundles over specific parts of the body to encourage baby to turn on their own. These methods have been long used, but she points out that the efficacy of these methods haven’t been proven in trials, so “the data isn’t compelling enough to say this is something you should do.”

What to Expect for a Breech Baby After Birth

If baby is presenting breech and you and your doctor decide to move forward with a vaginal delivery, there are some potential complications to be aware of that could ultimately affect baby’s health and well being.

It’s possible for baby’s head or shoulders to get wedged against your pelvic bones; a prolapsed umbilical cord could also decrease blood flow and cut off baby’s oxygen supply, explains the ACOG. That said, even a planned c-section comes with its own set of risks.

Welcoming a healthy baby into the world is the ultimate goal, regardless of how they’re delivered. Interestingly, babies who’ve been in breech presentation and are delivered via c-section tend to have nicely shaped heads because there’s none of the swelling and other head-shifting changes that occur in babies delivered through the birth canal, notes Deckers.

Do breech babies have problems later in life?

Sometimes babies who were breech have issues with their hips, as having one or both legs extended in a partially straight position rather than crossed can prevent a baby’s hip socket from developing properly. If your child was breech, Deckers recommends following up with your pediatrician.

Having a breech baby was probably not in your original birth plan. Your stubborn little one may turn before their grand debut, or they may—quite literally—put their foot down and refuse to budge. Either way, talk to your doctor about any concerns. And remember, the good news is that baby is coming soon, either way!

Please note: The Bump and the materials and information it contains are not intended to, and do not constitute, medical or other health advice or diagnosis and should not be used as such. You should always consult with a qualified physician or health professional about your specific circumstances.

Plus, more from The Bump:

What to Expect During Your C-Section Recovery

The Best Prenatal Poses for Better Sleep

How to Care for Your C-Section Scar

Elizabeth Deckers , MD, is the director of the maternal quality and safety program at Hartford HealthCare. She received her medical degree from the University of Connecticut School of Medicine in Farmington.

Amber Samuel , MD, is the medical director of Obstetrix Maternal-Fetal Medicine Specialists of Houston. She earned her medical degree at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas.

American Pregnancy Association, Breech Presentation

Lancet, Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group , October 2000

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), If Your Baby Is Breech

Learn how we ensure the accuracy of our content through our editorial and medical review process .

Navigate forward to interact with the calendar and select a date. Press the question mark key to get the keyboard shortcuts for changing dates.

Next on Your Reading List

- about Merck

- Merck Careers

Fetal Presentation, Position, and Lie (Including Breech Presentation)

- Key Points |

Abnormal fetal lie or presentation may occur due to fetal size, fetal anomalies, uterine structural abnormalities, multiple gestation, or other factors. Diagnosis is by examination or ultrasonography. Management is with physical maneuvers to reposition the fetus, operative vaginal delivery , or cesarean delivery .

Terms that describe the fetus in relation to the uterus, cervix, and maternal pelvis are

Fetal presentation: Fetal part that overlies the maternal pelvic inlet; vertex (cephalic), face, brow, breech, shoulder, funic (umbilical cord), or compound (more than one part, eg, shoulder and hand)

Fetal position: Relation of the presenting part to an anatomic axis; for transverse presentation, occiput anterior, occiput posterior, occiput transverse

Fetal lie: Relation of the fetus to the long axis of the uterus; longitudinal, oblique, or transverse

Normal fetal lie is longitudinal, normal presentation is vertex, and occiput anterior is the most common position.

Abnormal fetal lie, presentation, or position may occur with

Fetopelvic disproportion (fetus too large for the pelvic inlet)

Fetal congenital anomalies

Uterine structural abnormalities (eg, fibroids, synechiae)

Multiple gestation

Several common types of abnormal lie or presentation are discussed here.

Transverse lie

Fetal position is transverse, with the fetal long axis oblique or perpendicular rather than parallel to the maternal long axis. Transverse lie is often accompanied by shoulder presentation, which requires cesarean delivery.

Breech presentation

There are several types of breech presentation.

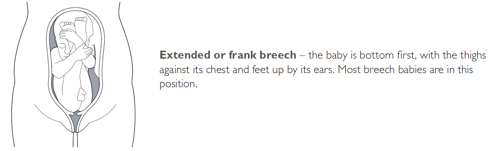

Frank breech: The fetal hips are flexed, and the knees extended (pike position).

Complete breech: The fetus seems to be sitting with hips and knees flexed.

Single or double footling presentation: One or both legs are completely extended and present before the buttocks.

Types of breech presentations

Breech presentation makes delivery difficult ,primarily because the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge. Having a poor dilating wedge can lead to incomplete cervical dilation, because the presenting part is narrower than the head that follows. The head, which is the part with the largest diameter, can then be trapped during delivery.

Additionally, the trapped fetal head can compress the umbilical cord if the fetal umbilicus is visible at the introitus, particularly in primiparas whose pelvic tissues have not been dilated by previous deliveries. Umbilical cord compression may cause fetal hypoxemia.

Predisposing factors for breech presentation include

Preterm labor

Uterine abnormalities

Fetal anomalies

If delivery is vaginal, breech presentation may increase risk of

Umbilical cord prolapse

Birth trauma

Perinatal death

Face or brow presentation

In face presentation, the head is hyperextended, and position is designated by the position of the chin (mentum). When the chin is posterior, the head is less likely to rotate and less likely to deliver vaginally, necessitating cesarean delivery.

Brow presentation usually converts spontaneously to vertex or face presentation.

Occiput posterior position

The most common abnormal position is occiput posterior.

The fetal neck is usually somewhat deflexed; thus, a larger diameter of the head must pass through the pelvis.

Progress may arrest in the second phase of labor. Operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery is often required.

Position and Presentation of the Fetus

If a fetus is in the occiput posterior position, operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery is often required.

In breech presentation, the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge, which can cause the head to be trapped during delivery, often compressing the umbilical cord.

For breech presentation, usually do cesarean delivery at 39 weeks or during labor, but external cephalic version is sometimes successful before labor, usually at 37 or 38 weeks.

- Cookie Preferences

Copyright © 2024 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.

- Getting Pregnant

- Registry Builder

- Baby Products

- Birth Clubs

- See all in Community

- Ovulation Calculator

- How To Get Pregnant

- How To Get Pregnant Fast

- Ovulation Discharge

- Implantation Bleeding

- Ovulation Symptoms

- Pregnancy Symptoms

- Am I Pregnant?

- Pregnancy Tests

- See all in Getting Pregnant

- Due Date Calculator

- Pregnancy Week by Week

- Pregnant Sex

- Weight Gain Tracker

- Signs of Labor

- Morning Sickness

- COVID Vaccine and Pregnancy

- Fetal Weight Chart

- Fetal Development

- Pregnancy Discharge

- Find Out Baby Gender

- Chinese Gender Predictor

- See all in Pregnancy

- Baby Name Generator

- Top Baby Names 2023

- Top Baby Names 2024

- How to Pick a Baby Name

- Most Popular Baby Names

- Baby Names by Letter

- Gender Neutral Names

- Unique Boy Names

- Unique Girl Names

- Top baby names by year

- See all in Baby Names

- Baby Development

- Baby Feeding Guide

- Newborn Sleep

- When Babies Roll Over

- First-Year Baby Costs Calculator

- Postpartum Health

- Baby Poop Chart

- See all in Baby

- Average Weight & Height

- Autism Signs

- Child Growth Chart

- Night Terrors

- Moving from Crib to Bed

- Toddler Feeding Guide

- Potty Training

- Bathing and Grooming

- See all in Toddler

- Height Predictor

- Potty Training: Boys

- Potty training: Girls

- How Much Sleep? (Ages 3+)

- Ready for Preschool?

- Thumb-Sucking

- Gross Motor Skills

- Napping (Ages 2 to 3)

- See all in Child

- Photos: Rashes & Skin Conditions

- Symptom Checker

- Vaccine Scheduler

- Reducing a Fever

- Acetaminophen Dosage Chart

- Constipation in Babies

- Ear Infection Symptoms

- Head Lice 101

- See all in Health

- Second Pregnancy

- Daycare Costs

- Family Finance

- Stay-At-Home Parents

- Breastfeeding Positions

- See all in Family

- Baby Sleep Training

- Preparing For Baby

- My Custom Checklist

- My Registries

- Take the Quiz

- Best Baby Products

- Best Breast Pump

- Best Convertible Car Seat

- Best Infant Car Seat

- Best Baby Bottle

- Best Baby Monitor

- Best Stroller

- Best Diapers

- Best Baby Carrier

- Best Diaper Bag

- Best Highchair

- See all in Baby Products

- Why Pregnant Belly Feels Tight

- Early Signs of Twins

- Teas During Pregnancy

- Baby Head Circumference Chart

- How Many Months Pregnant Am I

- What is a Rainbow Baby

- Braxton Hicks Contractions

- HCG Levels By Week

- When to Take a Pregnancy Test

- Am I Pregnant

- Why is Poop Green

- Can Pregnant Women Eat Shrimp

- Insemination

- UTI During Pregnancy

- Vitamin D Drops

- Best Baby Forumla

- Postpartum Depression

- Low Progesterone During Pregnancy

- Baby Shower

- Baby Shower Games

Breech, posterior, transverse lie: What position is my baby in?

Fetal presentation, or how your baby is situated in your womb at birth, is determined by the body part that's positioned to come out first, and it can affect the way you deliver. At the time of delivery, 97 percent of babies are head-down (cephalic presentation). But there are several other possibilities, including feet or bottom first (breech) as well as sideways (transverse lie) and diagonal (oblique lie).

Fetal presentation and position

During the last trimester of your pregnancy, your provider will check your baby's presentation by feeling your belly to locate the head, bottom, and back. If it's unclear, your provider may do an ultrasound or an internal exam to feel what part of the baby is in your pelvis.

Fetal position refers to whether the baby is facing your spine (anterior position) or facing your belly (posterior position). Fetal position can change often: Your baby may be face up at the beginning of labor and face down at delivery.

Here are the many possibilities for fetal presentation and position in the womb.

Medical illustrations by Jonathan Dimes

Head down, facing down (anterior position)

A baby who is head down and facing your spine is in the anterior position. This is the most common fetal presentation and the easiest position for a vaginal delivery.

This position is also known as "occiput anterior" because the back of your baby's skull (occipital bone) is in the front (anterior) of your pelvis.

Head down, facing up (posterior position)

In the posterior position , your baby is head down and facing your belly. You may also hear it called "sunny-side up" because babies who stay in this position are born facing up. But many babies who are facing up during labor rotate to the easier face down (anterior) position before birth.

Posterior position is formally known as "occiput posterior" because the back of your baby's skull (occipital bone) is in the back (posterior) of your pelvis.

Frank breech

In the frank breech presentation, both the baby's legs are extended so that the feet are up near the face. This is the most common type of breech presentation. Breech babies are difficult to deliver vaginally, so most arrive by c-section .

Some providers will attempt to turn your baby manually to the head down position by applying pressure to your belly. This is called an external cephalic version , and it has a 58 percent success rate for turning breech babies. For more information, see our article on breech birth .

Complete breech

A complete breech is when your baby is bottom down with hips and knees bent in a tuck or cross-legged position. If your baby is in a complete breech, you may feel kicking in your lower abdomen.

Incomplete breech

In an incomplete breech, one of the baby's knees is bent so that the foot is tucked next to the bottom with the other leg extended, positioning that foot closer to the face.

Single footling breech

In the single footling breech presentation, one of the baby's feet is pointed toward your cervix.

Double footling breech

In the double footling breech presentation, both of the baby's feet are pointed toward your cervix.

Transverse lie

In a transverse lie, the baby is lying horizontally in your uterus and may be facing up toward your head or down toward your feet. Babies settle this way less than 1 percent of the time, but it happens more commonly if you're carrying multiples or deliver before your due date.

If your baby stays in a transverse lie until the end of your pregnancy, it can be dangerous for delivery. Your provider will likely schedule a c-section or attempt an external cephalic version , which is highly successful for turning babies in this position.

Oblique lie

In rare cases, your baby may lie diagonally in your uterus, with his rump facing the side of your body at an angle.

Like the transverse lie, this position is more common earlier in pregnancy, and it's likely your provider will intervene if your baby is still in the oblique lie at the end of your third trimester.

Was this article helpful?

What to know if your baby is breech

What's a sunny-side up baby?

What happens to your baby right after birth

How your twins’ fetal positions affect labor and delivery

BabyCenter's editorial team is committed to providing the most helpful and trustworthy pregnancy and parenting information in the world. When creating and updating content, we rely on credible sources: respected health organizations, professional groups of doctors and other experts, and published studies in peer-reviewed journals. We believe you should always know the source of the information you're seeing. Learn more about our editorial and medical review policies .

Ahmad A et al. 2014. Association of fetal position at onset of labor and mode of delivery: A prospective cohort study. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology 43(2):176-182. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23929533 Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Gray CJ and Shanahan MM. 2019. Breech presentation. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448063/ Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Hankins GD. 1990. Transverse lie. American Journal of Perinatology 7(1):66-70. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2131781 Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Medline Plus. 2020. Your baby in the birth canal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002060.htm Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Where to go next

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

- Labor & Delivery

What Causes Breech Presentation?

Learn more about the types, causes, and risks of breech presentation, along with how breech babies are typically delivered.

What Is Breech Presentation?

Types of breech presentation, what causes a breech baby, can you turn a breech baby, how are breech babies delivered.

FatCamera/Getty Images

Toward the end of pregnancy, your baby will start to get into position for delivery, with their head pointed down toward the vagina. This is otherwise known as vertex presentation. However, some babies turn inside the womb so that their feet or buttocks are poised to be delivered first, which is commonly referred to as breech presentation, or a breech baby.

As you near the end of your pregnancy journey, an OB-GYN or health care provider will check your baby's positioning. You might find yourself wondering: What causes breech presentation? Are there risks involved? And how are breech babies delivered? We turned to experts and research to answer some of the most common questions surrounding breech presentation, along with what causes this positioning in the first place.

During your pregnancy, your baby constantly moves around the uterus. Indeed, most babies do somersaults up until the 36th week of pregnancy , when they pick their final position in the womb, says Laura Riley , MD, an OB-GYN in New York City. Approximately 3-4% of babies end up “upside-down” in breech presentation, with their feet or buttocks near the cervix.

Breech presentation is typically diagnosed during a visit to an OB-GYN, midwife, or health care provider. Your physician can feel the position of your baby's head through your abdominal wall—or they can conduct a vaginal exam if your cervix is open. A suspected breech presentation should ultimately be confirmed via an ultrasound, after which you and your provider would have a discussion about delivery options, potential issues, and risks.

There are three types of breech babies: frank, footling, and complete. Learn about the differences between these breech presentations.

Frank Breech

With frank breech presentation, your baby’s bottom faces the cervix and their legs are straight up. This is the most common type of breech presentation.

Footling Breech

Like its name suggests, a footling breech is when one (single footling) or both (double footling) of the baby's feet are in the birth canal, where they’re positioned to be delivered first .

Complete Breech

In a complete breech presentation, baby’s bottom faces the cervix. Their legs are bent at the knees, and their feet are near their bottom. A complete breech is the least common type of breech presentation.

Other Types of Mal Presentations

The baby can also be in a transverse position, meaning that they're sideways in the uterus. Another type is called oblique presentation, which means they're pointing toward one of the pregnant person’s hips.

Typically, your baby's positioning is determined by the fetus itself and the shape of your uterus. Because you can't can’t control either of these factors, breech presentation typically isn’t considered preventable. And while the cause often isn't known, there are certain risk factors that may increase your risk of a breech baby, including the following:

- The fetus may have abnormalities involving the muscular or central nervous system

- The uterus may have abnormal growths or fibroids

- There might be insufficient amniotic fluid in the uterus (too much or too little)

- This isn’t your first pregnancy

- You have a history of premature delivery

- You have placenta previa (the placenta partially or fully covers the cervix)

- You’re pregnant with multiples

- You’ve had a previous breech baby

In some cases, your health care provider may attempt to help turn a baby in breech presentation through a procedure known as external cephalic version (ECV). This is when a health care professional applies gentle pressure on your lower abdomen to try and coax your baby into a head-down position. During the entire procedure, the fetus's health will be monitored, and an ECV is often performed near a delivery room, in the event of any potential issues or complications.

However, it's important to note that ECVs aren't for everyone. If you're carrying multiples, there's health concerns about you or the baby, or you've experienced certain complications with your placenta or based on placental location, a health care provider will not attempt an ECV.

The majority of breech babies are born through C-sections . These are usually scheduled between 38 and 39 weeks of pregnancy, before labor can begin naturally. However, with a health care provider experienced in delivering breech babies vaginally, a natural delivery might be a safe option for some people. In fact, a 2017 study showed similar complication and success rates with vaginal and C-section deliveries of breech babies.

That said, there are certain known risks and complications that can arise with an attempt to deliver a breech baby vaginally, many of which relate to problems with the umbilical cord. If you and your medical team decide on a vaginal delivery, your baby will be monitored closely for any potential signs of distress.

Ultimately, it's important to know that most breech babies are born healthy. Your provider will consider your specific medical condition and the position of your baby to determine which type of delivery will be the safest option for a healthy and successful birth.

ACOG. If Your Baby Is Breech .

American Pregnancy Association. Breech Presentation .

Gray CJ, Shanahan MM. Breech Presentation . [Updated 2022 Nov 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-.

Mount Sinai. Breech Babies .

Takeda J, Ishikawa G, Takeda S. Clinical Tips of Cesarean Section in Case of Breech, Transverse Presentation, and Incarcerated Uterus . Surg J (N Y). 2020 Mar 18;6(Suppl 2):S81-S91. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1702985. PMID: 32760790; PMCID: PMC7396468.

Shanahan MM, Gray CJ. External Cephalic Version . [Updated 2022 Nov 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-.

Fonseca A, Silva R, Rato I, Neves AR, Peixoto C, Ferraz Z, Ramalho I, Carocha A, Félix N, Valdoleiros S, Galvão A, Gonçalves D, Curado J, Palma MJ, Antunes IL, Clode N, Graça LM. Breech Presentation: Vaginal Versus Cesarean Delivery, Which Intervention Leads to the Best Outcomes? Acta Med Port. 2017 Jun 30;30(6):479-484. doi: 10.20344/amp.7920. Epub 2017 Jun 30. PMID: 28898615.

Related Articles

What happens if your baby is breech?

Babies often twist and turn during pregnancy, but most will have moved into the head-down (also known as head-first) position by the time labour begins. However, that does not always happen, and a baby may be:

- bottom first or feet first (breech position)

- lying sideways (transverse position)

Bottom first or feet first (breech baby)

If your baby is lying bottom or feet first, they are in the breech position. If they're still breech at around 36 weeks' gestation, the obstetrician and midwife will discuss your options for a safe delivery.

Turning a breech baby

If your baby is in a breech position at 36 weeks, you'll usually be offered an external cephalic version (ECV). This is when a healthcare professional, such as an obstetrician, tries to turn the baby into a head-down position by applying pressure on your abdomen. It's a safe procedure, although it can be a bit uncomfortable.

Giving birth to a breech baby

If an ECV does not work, you'll need to discuss your options for a vaginal birth or caesarean section with your midwife and obstetrician.

If you plan a caesarean and then go into labour before the operation, your obstetrician will assess whether it's safe to proceed with the caesarean delivery. If the baby is close to being born, it may be safer for you to have a vaginal breech birth.

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) website has more information on what to expect if your baby is still breech at the end of pregnancy .

The RCOG advises against a vaginal breech delivery if:

- your baby's feet are below its bottom – known as a "footling breech"

- your baby is larger or smaller than average – your healthcare team will discuss this with you

- your baby is in a certain position – for example, their neck is very tilted back, which can make delivery of the head more difficult

- you have a low-lying placenta (placenta praevia)

- you have pre-eclampsia

Lying sideways (transverse baby)

If your baby is lying sideways across the womb, they are in the transverse position. Although many babies lie sideways early on in pregnancy, most turn themselves into the head-down position by the final trimester.

Giving birth to a transverse baby

Depending on how many weeks pregnant you are when your baby is in a transverse position, you may be admitted to hospital. This is because of the very small risk of the umbilical cord coming out of your womb before your baby is born (cord prolapse). If this happens, it's a medical emergency and the baby must be delivered very quickly.

Sometimes, it's possible to manually turn the baby to a head-down position, and you may be offered this.

But, if your baby is still in the transverse position when you approach your due date or by the time labour begins, you'll most likely be advised to have a caesarean section.

Video: My baby is breech. What help will I get?

In this video, a midwife describes what a breech position is and what can be done if your baby is breech.

Page last reviewed: 1 November 2023 Next review due: 1 November 2026

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

- Management of breech presentation

Evidence review M

NICE Guideline, No. 201

National Guideline Alliance (UK) .

- Copyright and Permissions

Review question

What is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy?

Introduction

Breech presentation of the fetus in late pregnancy may result in prolonged or obstructed labour with resulting risks to both woman and fetus. Interventions to correct breech presentation (to cephalic) before labour and birth are important for the woman’s and the baby’s health. The aim of this review is to determine the most effective way of managing a breech presentation in late pregnancy.

Summary of the protocol

Please see Table 1 for a summary of the Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome (PICO) characteristics of this review.

Summary of the protocol (PICO table).

For further details see the review protocol in appendix A .

Methods and process

This evidence review was developed using the methods and process described in Developing NICE guidelines: the manual 2014 . Methods specific to this review question are described in the review protocol in appendix A .

Declarations of interest were recorded according to NICE’s conflicts of interest policy .

Clinical evidence

Included studies.

Thirty-six randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were identified for this review.

The included studies are summarised in Table 2 .

Three studies reported on external cephalic version (ECV) versus no intervention ( Dafallah 2004 , Hofmeyr 1983 , Rita 2011 ). One study reported on a 4-arm trial comparing acupuncture, sweeping of fetal membranes, acupuncture plus sweeping, and no intervention ( Andersen 2013 ). Two studies reported on postural management versus no intervention ( Chenia 1987 , Smith 1999 ).

Seven studies reported on ECV plus anaesthesia ( Chalifoux 2017 , Dugoff 1999 , Khaw 2015 , Mancuso 2000 , Schorr 1997 , Sullivan 2009 , Weiniger 2010 ). Of these studies, 1 study compared ECV plus anaesthesia to ECV plus other dosages of the same anaesthetic ( Chalifoux 2017 ); 4 studies compared ECV plus anaesthesia to ECV only ( Dugoff 1999 , Mancuso 2000 , Schorr 1997 , Weiniger 2010 ); and 2 studies compared ECV plus anaesthesia to ECV plus a different anaesthetic ( Khaw 2015 , Sullivan 2009 ).

Ten studies reported ECV plus a β2 receptor agonist ( Brocks 1984 , Fernandez 1997 , Hindawi 2005 , Impey 2005 , Mahomed 1991 , Marquette 1996 , Nor Azlin 2005 , Robertson 1987 , Van Dorsten 1981 , Vani 2009 ). Of these studies, 5 studies compared ECV plus a β2 receptor agonist to ECV plus placebo ( Fernandez 1997 , Impey 2005 , Marquette 1996 , Nor Azlin 2005 , Vani 2009 ); 1 study compared ECV plus a β2 receptor agonist to ECV alone ( Robertson 1987 ); and 4 studies compared ECV plus a β2 receptor agonist to no intervention ( Brocks 1984 , Hindawi 2005 , Mahomed 1991 , Van Dorsten 1981 ).

One study reported on ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker versus ECV plus placebo ( Kok 2008 ). Two studies reported on ECV plus β2 receptor agonist versus ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker ( Collaris 2009 , Mohamed Ismail 2008 ). Four studies reported on ECV plus a µ-receptor agonist ( Burgos 2016 , Liu 2016 , Munoz 2014 , Wang 2017 ), of which 3 compared against ECV plus placebo ( Liu 2016 , Munoz 2014 , Wang 2017 ) and 1 compared to ECV plus nitrous oxide ( Burgos 2016 ).

Four studies reported on ECV plus nitroglycerin ( Bujold 2003a , Bujold 2003b , El-Sayed 2004 , Hilton 2009 ), of which 2 compared it to ECV plus β2 receptor agonist ( Bujold 2003b , El-Sayed 2004 ) and compared it to ECV plus placebo ( Bujold 2003a , Hilton 2009 ). One study compared ECV plus amnioinfusion versus ECV alone ( Diguisto 2018 ) and 1 study compared ECV plus talcum powder to ECV plus gel ( Vallikkannu 2014 ).

One study was conducted in Australia ( Smith 1999 ); 4 studies in Canada ( Bujold 2003a , Bujold 2003b , Hilton 2009 , Marquette 1996 ); 2 studies in China ( Liu 2016 , Wang 2017 ); 2 studies in Denmark ( Andersen 2013 , Brocks 1984 ); 1 study in France ( Diguisto 2018 ); 1 study in Hong Kong ( Khaw 2015 ); 1 study in India ( Rita 2011 ); 1 study in Israel ( Weiniger 2010 ); 1 study in Jordan ( Hindawi 2005 ); 5 studies in Malaysia ( Collaris 2009 , Mohamed Ismail 2008 , Nor Azlin 2005 , Vallikkannu 2014 , Vani 2009 ); 1 study in South Africa ( Hofmeyr 1983 ); 2 studies in Spain ( Burgos 2016 , Munoz 2014 ); 1 study in Sudan ( Dafallah 2004 ); 1 study in The Netherlands ( Kok 2008 ); 2 studies in the UK ( Impey 2005 , Chenia 1987 ); 9 studies in US ( Chalifoux 2017 , Dugoff 1999 , El-Sayed 2004 , Fernandez 1997 , Mancuso 2000 , Robertson 1987 , Schorr 1997 , Sullivan 2009 , Van Dorsten 1981 ); and 1 study in Zimbabwe ( Mahomed 1991 ).

The majority of studies were 2-arm trials, but there was one 3-arm trial ( Khaw 2015 ) and two 4-arm trials ( Andersen 2013 , Chalifoux 2017 ). All studies were conducted in a hospital or an outpatient ward connected to a hospital.

See the literature search strategy in appendix B and study selection flow chart in appendix C .

Excluded studies

Studies not included in this review with reasons for their exclusions are provided in appendix K .

Summary of clinical studies included in the evidence review

Summaries of the studies that were included in this review are presented in Table 2 .

Summary of included studies.

See the full evidence tables in appendix D and the forest plots in appendix E .

Quality assessment of clinical outcomes included in the evidence review

See the evidence profiles in appendix F .

Economic evidence

A systematic review of the economic literature was conducted but no economic studies were identified which were applicable to this review question.

A single economic search was undertaken for all topics included in the scope of this guideline. See supplementary material 2 for details.

Economic studies not included in this review are listed, and reasons for their exclusion are provided in appendix K .

Summary of studies included in the economic evidence review

No economic studies were identified which were applicable to this review question.

Economic model

No economic modelling was undertaken for this review because the committee agreed that other topics were higher priorities for economic evaluation.

Evidence statements

Clinical evidence statements, comparison 1. complementary therapy versus control (no intervention), critical outcomes, cephalic presentation in labour.

No evidence was identified to inform this outcome.

Method of birth

Caesarean section.

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=204) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and control (no intervention) on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.74 (95% CI 0.38 to 1.43).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=200) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture plus membrane sweeping and control (no intervention) on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.29 (95% CI 0.73 to 2.29).

Admission to SCBU/NICU

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=204) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and control (no intervention) on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.19 (95% CI 0.02 to 1.62).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=200) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture plus membrane sweeping and control (no intervention) on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.40 (0.08 to 2.01).

Fetal death after 36 +0 weeks gestation

Infant death up to 4 weeks chronological age, important outcomes, apgar score <7 at 5 minutes.

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=204) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and control (no intervention) on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.32 (95% CI 0.01 to 7.78).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=200) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture plus membrane sweeping and control (no intervention) on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.33 (0.01 to 8.09).

Birth before 39 +0 weeks of gestation

Comparison 2. complementary therapy versus other treatment.

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=207) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and membrane sweeping on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.64 (95% CI 0.34 to 1.22).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=204) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and acupuncture plus membrane sweeping on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.57 (95% CI 0.30 to 1.07).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=203) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture plus membrane sweeping and membrane sweeping on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.13 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.94).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=207) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and membrane sweeping on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.33 (95% CI 0.03 to 3.12).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=204) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and acupuncture plus membrane sweeping on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.48 (95% CI 0.04 to 5.22).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=203) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture plus membrane sweeping and membrane sweeping on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.69 (95% CI 0.12 to 4.02).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=207) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and membrane sweeping on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.02 to 0.02).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=204) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and acupuncture plus membrane sweeping on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.02 to 0.02).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=203) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture plus membrane sweeping and membrane sweeping on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.02 to 0.02).

Comparison 3. ECV versus no ECV

- Moderate quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=680) showed that there is clinically important difference favouring ECV over no ECV on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.83 (95% CI 1.53 to 2.18).

Cephalic vaginal birth

- Very low quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=740) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV over no ECV on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.67 (95% CI 1.20 to 2.31).

Breech vaginal birth

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=680) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV and no ECV on breech vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.29 (95% CI 0.03 to 2.84).

- Very low quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=740) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV and no ECV on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.52 (95% CI 0.23 to 1.20).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=60) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV and no ECV on admission to SCBU//NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.50 (95% CI 0.14 to 1.82).

- Very low evidence from 3 RCTs (N=740) showed that there is no statistically significant difference between ECV and no ECV on fetal death after 36 +0 weeks gestation in pregnant women with breech presentation: Peto OR 0.29 (95% CI 0.05 to 1.73) p=0.18.

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV and no ECV on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: Peto OR 0.28 (95% CI 0.04 to 1.70).

Comparison 4. ECV + Amnioinfusion versus ECV only

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=109) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus amnioinfusion and ECV alone on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.74 (95% CI 0.74 to 4.12).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=109) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus amnioinfusion and ECV alone on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.95 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.19).

Comparison 5. ECV + Anaesthesia versus ECV only

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=210) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus anaesthesia and ECV alone on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.16 (95% CI 0.56 to 2.41).

- Very low quality evidence from 5 RCTs (N=435) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus anaesthesia and ECV alone on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.16 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.74).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=108) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus anaesthesia and ECV alone on breech vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.33 (95% CI 0.04 to 3.10).

- Very low quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=263) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus anaesthesia and ECV alone on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.76 (95% CI 0.42 to 1.38).

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=69) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus anaesthesia over ECV alone on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: MD −1.80 (95% CI −2.53 to −1.07).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=126) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus anaesthesia and ECV alone on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.03).

Comparison 6. ECV + Anaesthesia versus ECV + Anaesthesia

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.13 (95% CI 0.73 to 1.74).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=119) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 7.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.81 (95% CI 0.53 to 1.23).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 10mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.96 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.50).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=95) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 0.05mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.69 (95% CI 0.37 to 1.28).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=119) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 7.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.81 (95% CI 0.53 to 1.23).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 10mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.96 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.50).

- Very low evidence from 1 RCT (N=119) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 7.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 10mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.19 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.79).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.92 (95% CI 0.68 to 1.24).

- Very low evidence from 1 RCT (N=119) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 7.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.08 (95% CI 0.78 to 1.50).

- Very low evidence from 1 RCT (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 10mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.94 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.28).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=119) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 7.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.17 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.61).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 10mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.03 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.37).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=119) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 7.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 10mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.88 (95% CI 0.64 to 1.20).

Comparison 7. ECV + β2 agonist versus Control (no intervention)

- Moderate quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=256) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus β2 agonist over control (no intervention) on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 4.83 (95% CI 3.27 to 7.11).

- Very low quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=265) showed that there no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and control (no intervention) on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 2.03 (95% CI 0.22 to 19.01).

- Very low quality evidence from 4 RCTs (N=513) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus β2 agonist over control (no intervention) on breech vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.38 (95% CI 0.20 to 0.69).

- Low quality evidence from 4 RCTs (N=513) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus β2 agonist over control (no intervention) on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.53 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.67).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=48) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and control (no intervention) on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.08 to 0.08).

- Very low quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=208) showed that there is no statistically significant difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and control (no intervention) on fetal death after 36 +0 weeks gestation in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD −0.01 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.01) p=0.66.

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=208) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and control (no intervention) on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: Peto OR 0.80 (95% CI 0.31 to 2.10).

Comparison 8. ECV + β2 agonist versus ECV only

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=172) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV only on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.32 (95% CI 0.67 to 2.62).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=58) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV only on breech vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.75 (95% CI 0.22 to 2.50).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=172) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV only on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.79 (95% CI 0.27 to 2.28).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=114) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV only on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.00 (95% CI 0.21 to 4.75).

Comparison 9. ECV + β2 agonist versus ECV + Placebo

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=146) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus placebo on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.54 (95% CI 0.24 to 9.76).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=125) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus placebo on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.27 (95% CI 0.41 to 3.89).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=227) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus placebo on breech vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.00 (95% CI 0.33 to 2.97).

- Low quality evidence from 4 RCTs (N=532) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus placebo on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.81 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.92)

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=146) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus placebo on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.78 (95% CI 0.17 to 3.63).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=124) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus placebo on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.03).

Comparison 10. ECV + Ca 2+ channel blocker versus ECV + Placebo

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=310) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus placebo on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.13 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.48).

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=310) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus placebo on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.90 (95% CI 0.73 to 1.12).

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=310) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus placebo on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.11 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.40).

- High quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=310) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus placebo on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: MD −0.20 (95% CI −0.70 to 0.30).

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=310) showed that there is no statistically significant difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus placebo on fetal death after 36 +0 weeks gestation in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.01 to 0.01) p=1.00.

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=310) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus placebo on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: Peto OR 0.52 (95% 0.05 to 5.02).

Comparison 11. ECV + Ca2+ channel blocker versus ECV + β2 agonist

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=90) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus β2 agonist over ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.62 (95% CI 0.39 to 0.98).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=126) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus β2 agonist on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.26 (95% CI 0.55 to 2.89).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=132) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus β2 agonist over ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.42 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.91).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=176) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus β2 agonist on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: Peto OR 0.53 (95% CI 0.05 to 5.22).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=176) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus β2 agonist on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.03).

Comparison 12. ECV + µ-receptor agonist versus ECV only

- High quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=80) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV alone on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.00 (95% CI 0.80 to 1.24).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=80) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV alone on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.00 (95% CI 0.42 to 2.40).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=126) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV alone on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.03).

Comparison 13. ECV + µ-receptor agonist versus ECV + Placebo

Cephalic vaginal birth after successful ecv.

- High quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=98) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus placebo on cephalic vaginal birth after successful ECV in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.00 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.17).

Caesarean section after successful ECV

- Low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=98) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus placebo on caesarean section after successful ECV in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.97 (95% CI 0.33 to 2.84).

Breech vaginal birth after unsuccessful ECV

- High quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=186) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus µ-receptor agonist over ECV plus placebo on breech vaginal birth after unsuccessful ECV in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.10 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.53).

Caesarean section after unsuccessful ECV

- Moderate quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=186) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus placebo on caesarean section after unsuccessful ECV in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.19 (95% CI 1.09 to 1.31).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=137) showed that there is no statistically significant difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus placebo on fetal death after 36 +0 weeks gestation in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.03) p=1.00.

Comparison 14. ECV + µ-receptor agonist versus ECV + Anaesthesia

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=92) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus anaesthesia on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.04 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.29).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=212) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus anaesthesia on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.90 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.34).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=129) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus anaesthesia on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 2.30 (95% CI 0.21 to 24.74).

- Low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=255) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus anaesthesia on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.02 to 0.02).

Comparison 15. ECV + Nitric oxide donor versus ECV + Placebo

- Very low quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=224) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus nitric oxide donor and ECV plus placebo on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.13 (95% CI 0.59 to 2.16).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=99) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus nitric oxide donor and ECV plus placebo on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.78 (95% CI 0.49 to 1.22).

- Low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=125) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus nitric oxide donor and ECV plus placebo on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.83 (95% CI 0.68 to 1.01).

Comparison 16. ECV + Nitric oxide donor versus ECV + β2 agonist

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=74) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus nitric oxide donor on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.56 (95% CI 0.29 to 1.09).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=97) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus nitric oxide donor and ECV plus β2 agonist on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.98 (95% CI 0.47 to 2.05).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=59) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus nitric oxide donor and ECV plus β2 agonist on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.07 (95% CI 0.73 to 1.57).

Comparison 17. ECV + Talcum powder versus ECV + Gel