Patient Case #1: 27-Year-Old Woman With Bipolar Disorder

- Theresa Cerulli, MD

- Tina Matthews-Hayes, DNP, FNP, PMHNP

Custom Around the Practice Video Series

Experts in psychiatry review the case of a 27-year-old woman who presents for evaluation of a complex depressive disorder.

EP: 1 . Patient Case #1: 27-Year-Old Woman With Bipolar Disorder

Ep: 2 . clinical significance of bipolar disorder, ep: 3 . clinical impressions from patient case #1, ep: 4 . diagnosis of bipolar disorder, ep: 5 . treatment options for bipolar disorder, ep: 6 . patient case #2: 47-year-old man with treatment resistant depression (trd), ep: 7 . patient case #2 continued: novel second-generation antipsychotics, ep: 8 . role of telemedicine in bipolar disorder.

Michael E. Thase, MD : Hello and welcome to this Psychiatric Times™ Around the Practice , “Identification and Management of Bipolar Disorder. ”I’m Michael Thase, professor of psychiatry at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Joining me today are: Dr Gustavo Alva, the medical director of ATP Clinical Research in Costa Mesa, California; Dr Theresa Cerulli, the medical director of Cerulli and Associates in North Andover, Massachusetts; and Dr Tina Matthew-Hayes, a dual-certified nurse practitioner at Western PA Behavioral Health Resources in West Mifflin, Pennsylvania.

Today we are going to highlight challenges with identifying bipolar disorder, discuss strategies for optimizing treatment, comment on telehealth utilization, and walk through 2 interesting patient cases. We’ll also involve our audience by using several polling questions, and these results will be shared after the program.

Without further ado, welcome and let’s begin. Here’s our first polling question. What percentage of your patients with bipolar disorder have 1 or more co-occurring psychiatric condition? a. 10%, b. 10%-30%, c. 30%-50%, d. 50%-70%, or e. more than 70%.

Now, here’s our second polling question. What percentage of your referred patients with bipolar disorder were initially misdiagnosed? Would you say a. less than 10%, b. 10%-30%, c. 30%-50%, d. more than 50%, up to 70%, or e. greater than 70%.

We’re going to go ahead to patient case No. 1. This is a 27-year-old woman who’s presented for evaluation of a complex depressive syndrome. She has not benefitted from 2 recent trials of antidepressants—sertraline and escitalopram. This is her third lifetime depressive episode. It began back in the fall, and she described the episode as occurring right “out of the blue.” Further discussion revealed, however, that she had talked with several confidantes about her problems and that she realized she had been disappointed and frustrated for being passed over unfairly for a promotion at work. She had also been saddened by the unusually early death of her favorite aunt.

Now, our patient has a past history of ADHD [attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder], which was recognized when she was in middle school and for which she took methylphenidate for adolescence and much of her young adult life. As she was wrapping up with college, she decided that this medication sometimes disrupted her sleep and gave her an irritable edge, and decided that she might be better off not taking it. Her medical history was unremarkable. She is taking escitalopram at the time of our initial evaluation, and the dose was just reduced by her PCP [primary care physician]from 20 mg to 10 mg because she subjectively thought the medicine might actually be making her worse.

On the day of her first visit, we get a PHQ-9 [9-item Patient Health Questionnaire]. The score is 16, which is in the moderate depression range. She filled out the MDQ [Mood Disorder Questionnaire] and scored a whopping 10, which is not the highest possible score but it is higher than 95% of people who take this inventory.

At the time of our interview, our patient tells us that her No. 1 symptom is her low mood and her ease to tears. In fact, she was tearful during the interview. She also reports that her normal trouble concentrating, attributable to the ADHD, is actually substantially worse. Additionally, in contrast to her usual diet, she has a tendency to overeat and may have gained as much as 5 kg over the last 4 months. She reports an irregular sleep cycle and tends to have periods of hypersomnolence, especially on the weekends, and then days on end where she might sleep only 4 hours a night despite feeling tired.

Upon examination, her mood is positively reactive, and by that I mean she can lift her spirits in conversation, show some preserved sense of humor, and does not appear as severely depressed as she subjectively describes. Furthermore, she would say that in contrast to other times in her life when she’s been depressed, that she’s actually had no loss of libido, and in fact her libido might even be somewhat increased. Over the last month or so, she’s had several uncharacteristic casual hook-ups.

So the differential diagnosis for this patient included major depressive disorder, recurrent unipolar with mixed features, versus bipolar II disorder, with an antecedent history of ADHD. I think the high MDQ score and recurrent threshold level of mixed symptoms within a diagnosable depressive episode certainly increase the chances that this patient’s illness should be thought of on the bipolar spectrum. Of course, this formulation is strengthened by the fact that she has an early age of onset of recurrent depression, that her current episode, despite having mixed features, has reverse vegetative features as well. We also have the observation that antidepressant therapy has seemed to make her condition worse, not better.

Transcript Edited for Clarity

Dr. Thase is a professor of psychiatry at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Dr. Alva is the medical director of ATP Clinical Research in Costa Mesa, California.

Dr. Cerulli is the medical director of Cerulli and Associates in Andover, Massachusetts.

Dr. Tina Matthew-Hayes is a dual certified nurse practitioner at Western PA Behavioral Health Resources in West Mifflin, Pennsylvania.

An Update on Early Intervention in Psychotic Disorders

Blue Light, Depression, and Bipolar Disorder

The 2024 APA Annual Meeting: Sunday, May 5

Four Myths About Lamotrigine

The Week in Review: April 1-5

FDA Approves Fanapt for Mixed, Manic Episodes Associated With Bipolar I Disorder

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 07 July 2021

Assessment of suicide attempt and death in bipolar affective disorder: a combined clinical and genetic approach

- Eric T. Monson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8552-8300 1 ,

- Andrey A. Shabalin 1 ,

- Anna R. Docherty 1 ,

- Emily DiBlasi 1 ,

- Amanda V. Bakian ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6805-1160 1 , 2 ,

- Qingqin S. Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4182-4535 3 ,

- Douglas Gray 1 , 4 ,

- Brooks Keeshin 1 , 5 ,

- Sheila E. Crowell 1 , 6 , 7 ,

- Niamh Mullins ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8021-839X 8 , 9 ,

- Virginia L. Willour 10 &

- Hilary Coon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8877-5446 1 , 11 , 12

Translational Psychiatry volume 11 , Article number: 379 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

16k Accesses

9 Citations

72 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Bipolar disorder

- Comparative genomics

Bipolar disorder (BP) suicide death rates are 10–30 times greater than the general population, likely arising from environmental and genetic risk factors. Though suicidal behavior in BP has been investigated, studies have not addressed combined clinical and genetic factors specific to suicide death. To address this gap, a large, harmonized BP cohort was assessed to identify clinical risk factors for suicide death and attempt which then directed testing of underlying polygenic risks. 5901 individuals of European ancestry were assessed: 353 individuals with BP and 2498 without BP who died from suicide (BPS and NBPS, respectively) from a population-derived sample along with a volunteer-derived sample of 799 individuals with BP and a history of suicide attempt (BPSA), 824 individuals with BP and no prior attempts (BPNSA), and 1427 individuals without several common psychiatric illnesses per self-report (C). Clinical and subsequent directed genetic analyses utilized multivariable logistic models accounting for critical covariates and multiple testing. There was overrepresentation of diagnosis of PTSD (OR = 4.9, 95%CI: 3.1–7.6) in BPS versus BPSA, driven by female subjects. PRS assessments showed elevations in BPS including PTSD (OR = 1.3, 95%CI:1.1–1.5, versus C), female-derived ADHD (OR = 1.2, 95%CI:1.1–1.4, versus C), and male insomnia (OR = 1.4, 95%CI: 1.1–1.7, versus BPSA). The results provide support from genetic and clinical standpoints for dysregulated traumatic response particularly increasing risk of suicide death among individuals with BP of Northern European ancestry. Such findings may direct more aggressive treatment and prevention of trauma sequelae within at-risk bipolar individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Dissecting clinical heterogeneity of bipolar disorder using multiple polygenic risk scores

Key subphenotypes of bipolar disorder are differentially associated with polygenic liabilities for bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and major depressive disorder

Clinical and genetic validity of quantitative bipolarity

Introduction.

Suicidal behavior, which can be defined in many ways, is here defined as behaviors that include suicide attempt and death by suicide [ 1 ]. Prior suicide attempt is consistently one of the strongest predictors of eventual death by suicide [ 2 , 3 ]. However, the vast majority of individuals that attempt suicide will not die by suicide. Only ~2.8% of individuals with at least one prior suicide attempt die by suicide [ 4 ]. Despite this, existing research on suicidal behavior primarily focuses on the evaluation of suicide attempt under the assumption that attempt acts as an adequate proxy for suicide death. Distinguishing factors important to suicide attempt versus suicide death will be crucial to the implementation of effective interventions to those most likely to die.

Patients with bipolar disorder (BP) have high rates of suicide attempt (30–50%) and death (15–20%) [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. The rates for attempt and death are approximately twice those seen for major depression [ 5 , 8 ] and the rate of death is greater than in any disorder except schizophrenia [ 9 ]. These features suggest potential elevation of biological risk of suicide specific to BP. For this study, we leveraged the largest cohort of population-ascertained suicide decedents available, representing over 7000 individuals collected over two decades in the state of Utah [ 10 ]. The majority of these subjects have genetic data available via array genotyping. Electronic health records (EHRs) of these subjects allowed for the identification of 353 individuals with BP who died by suicide. In addition to this unique sample, we utilized a large array-genotyped NIMH Genetics Initiative sample ( N = 3050) including individuals with diagnosed BP, with and without a history of suicide attempt, and a comparison group that was screened for several common psychiatric illnesses via self-report [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Together, these cohorts allowed a comprehensive study of clinical and hypothesis-driven genetic risk factors for suicide death in bipolar disorder and allowed for differentiation of risk factors between attempt and death.

Materials and methods

Sample selection.

Two distinct sample sets were utilized. The first was composed of >7000 population-ascertained individuals who died from suicide from the Utah Suicide Genetics Research Study (USGRS). These samples were collected through a collaboration with the Utah Medical Examiner’s office and have been securely linked to electronic health record (EHR) information via the Utah Population Database (UPDB), a statewide data resource of demographic and health information ( https://healthcare.utah.edu/huntsmancancerinstitute/research/updb ). Because the study design involved analysis of EHR followed by hypothesis-driven analyses of polygenic risk, a subset of 2851 suicide deaths with screened genome-wide genotyping data and who were linked to existing EHR data (see supplementary methods) were retained. Inpatient and ambulatory EHRs were obtained from Utah providers covering approximately 85% of the state, though they may not represent all health records for each individual. After EHR linking, identifying data were stripped before providing data to the research team; suicide cases were referenced by anonymous IDs. The individuals selected for this study had at least one prior diagnostic code for bipolar disorder (specifically bipolar I or bipolar NOS). EHR were also screened for schizophrenia diagnoses and these Individuals were removed from the BP group to increase the probability of diagnostic homogeneity. All individuals excluded from diagnosis in the BP suicide death group were also excluded from the non-BP suicide deaths to ensure that no known BP diagnoses (including diagnoses of cyclothymia, manic depressive disorder, and bipolar II) would be present within the non-BP suicide death group. A total of 353 individuals with BP who died from suicide (referred to as “BPS”) and 2498 individuals without a diagnosis of BP who died from suicide (referred to as “NBPS”) from Utah were included in the analyses. This sample represents the single largest known genotyped sample of BP suicide deaths and, in a post-hoc evaluation of power, was predicted to have 80% power to identify a clinical diagnostic difference between suicide death and comparison groups with an odds ratio of 1.7 as calculated via the UCSF online sample size calculator [ 15 ].

The second set of individuals was composed of a pre-existing de-identified genotyped dataset derived from the NIMH genetics initiative bipolar GWAS [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 16 ] with a history of bipolar I or schizoaffective, bipolar type diagnoses as determined by formal evaluation and best-estimate diagnosis meeting criteria from the DSM-IIIR [ 17 ] or DSM-IV [ 18 ]. These individuals were selected for having complete clinical information from interview evaluation (individuals with missing information were excluded from this study). It is noted that interviews did not systematically evaluate for all included diagnoses, and that information from collected medical records and family informants that were used to support diagnoses were not available for all subjects (see Supplementary materials for more specific details of collected subject data). Individuals with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and a history one or more suicide attempts ( N = 799, referred to as “BPSA”) and individuals with a diagnosis of BP and no history of prior suicide attempt ( N = 824, referred to as “BPNSA”) were selected for inclusion in the study with diagnostic and historical data being obtained via the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS v4) [ 19 ]. A comparison group of individuals who were screened for several common psychiatric disorders via self-report [ 14 ] were also included ( N = 1427, referred to as “C”). Briefly, screened illnesses excluded at the time of sample construction included major depression, psychosis, and bipolar disorder [ 12 ]. This sample has been described elsewhere (including acquisition and quality control efforts), noting that informed consent and appropriate IRB approval for all involved subjects was obtained in the original studies [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ].

Utah suicide decedent DNAs were extracted from whole blood, and were genotyped using the Illumina Infinium PsychArray ( https://www.illumina.com/products/by-type/microarray-kits/infinium-psycharray.html ) as described elsewhere [ 10 ]. DNAs from the NIMH BP and control populations were extracted from lymphoblastoid cell lines maintained at the NIMH DNA Repository (Infinite biologics, Rutgers RUCDR, https://www.rucdr.org/ ), and were genotyped using the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 ( https://www.thermofisher.com/us/en/home/life-science/microarray-analysis/affymetrix.html ) and processed as previously described [ 12 , 16 , 20 ,]. Shared high-quality called variants from both platforms were combined and imputed via the Michigan Imputation Server [ 21 ] to a total of 7 437 997 high quality imputed variants. Extensive quality control steps, including assessment for ancestry and relatedness, were utilized to prepare this sample for analysis (see Supplementary methods ). Due to sensitivity of polygenic risk scores to ancestry effects, this study focused only on individuals of >90% European ancestry.

Analysis of sample characteristics

Statistical evaluation of the distribution of sex, age, education level, and clinical categories across all comparison groups were evaluated by chi-square (sex, education, clinical categories) or ANOVA (age).

Analyses of clinical data

Five clinical diagnostic categories were constructed from available diagnoses based on consensus of M.D./Ph.D.-level clinicians (E.M., B.K., A.D.) for all subjects with full details within the Supplementary methods and Supplementary Table S1 . Briefly, these categories represented non-traumatic anxiety disorders, behavioral disorders, personality disorders, eating disorders, and PTSD. The primary clinical analysis compared BPS, BPSA, and BPNSA within these categories.

All clinical categories were also secondarily evaluated to determine if observed effects were specific to BPS. NBPS were compared with BPS for these assessments.

All clinical analyses utilized logistic multivariable regression in R [ 22 ] accounting for age, sex, and education level. All variables were derived from single, independent measures for each subject. It was also noted that BPS had considerably more clinical diagnoses, on average, than NBPS, necessitating the inclusion of a clinical diagnosis count covariate within analyses comparing these groups. Effect size estimates were calculated via adjusted odds ratio from each model. Correction for multiple testing of 15 primary and 30 sex-specific clinical analyses utilized the Benjamini–Hochberg method with a false discovery rate of 0.05.

Analyses of genetic data

PRS calculations of several phenotypes, selected via significant clinical analysis results, were generated from 9 GWAS datasets (19 PRS total). Summary GWAS data arose from meta-analyses with publicly available summary statistics for ADHD [ 23 , 24 ], anxiety [ 25 ], insomnia [ 26 ], PTSD [ 27 ], suicide attempt [ 28 ], and neuroticism [ 29 ]. Many of these sets included summary statistics for population subsets, including male- and female-only analyses, referred to here as “sex-derived” sets, which were also analyzed. Suicide death PRS was calculated from the USGRS suicide death GWAS using a cross-validation approach described elsewhere [ 10 ]. Suicide attempt in bipolar disorder PRS were calculated from published Psychiatric Genomic Consortium data [ 28 ] with all overlapping study subjects removed. PRS calculations were conducted using PRSice 2.0 [ 30 ] with a p -value threshold of 1.0 as described in the Supplemental note. All PRS were standardized to Z-scores prior to statistical analysis.

Pairwise comparisons of BPS, BPSA, BPNSA, and C utilized multivariable logistic regression models in R [ 22 ], accounting for age, sex, and the first 10 principal components to control for residual ancestry effects. As with the clinical variables and covariates, all variables were obtained from independent measures without duplication. PRS measures were evaluated to have similar variance across groups during assessment and as visualized in plots. Effect size estimates were calculated by adjusted odds ratio from each model. Correction for multiple testing of 114 primary and 204 sex-specific PRS analyses utilized Benjamini–Hochberg calculations with a false discovery rate of 0.05.

Sample evaluation

Sample demographics, including frequency of comorbid diagnoses within the defined clinical categories and statistical evaluation of the distribution across the groups for each demographic are outlined in Table 1 . It is noted that the groups varied from one another significantly, but particularly striking differences can be appreciated in the sex distribution of each group. These differences are consistent with expectations that more males than females die from suicide, and more females than males attempt suicide [ 31 ]. However, it is notable that the excess of male deaths was significantly lower in BPS when compared to NBPS (62.0% of BPS being male versus 79.5% of NBPS being male, OR = 0.42, 95%CI = 0.33–0.53; X 2 = 54.1, P = 1.9 × 10 –13 ).

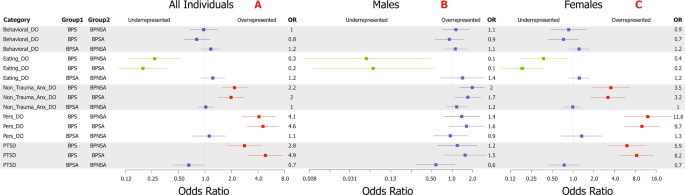

Clinical analyses of BPS, BPSA, and BPNSA

Complete results can be viewed within Supplementary Tables S2 and S3 with odds ratios and confidence intervals displayed in Fig. 1 . All results are corrected for multiple testing and covariates. BPS versus BPSA showed overrepresentation for diagnoses of PTSD (OR = 4.9, 95%CI = 3.1–7.6; P = 6.0 × 10 −11 ), personality disorders (OR = 4.6, 95%CI = 3.0–7.0; P = 2.2 × 10 −11 ; noting the caveat discussed in the limitations), and non-traumatic anxiety disorders (OR = 2.0, 95%CI = 1.4–2.8; P = 1.3 × 10 −4 ). Eating disorder diagnoses were significantly reduced within BPS versus BPSA (OR = 0.2, 95%CI = 0.1–0.4; P = 2.2 × 10 −6 ). No comparisons were significant between BPSA and BPNSA.

Forest plot distribution of corrected odds ratios of the primary clinical category comparisons (with 95% confidence interval represented by whiskers) within all individuals ( A ), males ( B ), and females ( C ). Labeling of comparison groups is as follows: BPS = individuals with bipolar disorder who died by suicide, BPSA = individuals with bipolar disorder who have a history of one or more suicide attempts, and BPNSA = individuals with bipolar disorder who have no history of a suicide attempt. Significant results are colored with overrepresentation shown in red and underrepresentation in green. Non-significant results are shown in blue. Results were corrected for multiple testing via the Benjamini–Hochberg method with an FDR of 0.05 for a total of 15 tests in the primary analysis ( A ) and 30 in the sex-specific analyses ( B , C ) and for critical covariates.

Secondary sex-specific results are shown in Fig. 1 B and C . Females strongly drove overrepresentations of PTSD (OR = 8.2, 95%CI = 4.7–14.4; P = 3.4 × 10 −11 ), personality disorder (OR = 9.7, 95%CI = 5.5–17.4; P = 4.5 × 10 −13 ), and non-traumatic anxiety disorder (OR = 3.2, 95%CI = 1.7–5.7; P = 6.1 × 10 −4 ) in BPS versus BPSA. Females also drove the reduced rate of eating disorder diagnoses in BPS versus BPSA (OR = 0.2, 95%CI = 0.1–0.4; P = 1.1 × 10 −5 ). Though male BPS versus male BPSA showed nominal overrepresentation of non-traumatic anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and PTSD, none of these results survived correction for multiple testing.

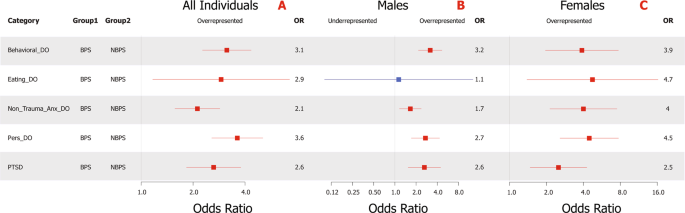

Clinical analysis of BPS versus NBPS

Comparisons are shown in Fig. 2 with complete results in Supplementary Tables S4 and S5 . Even after correction for medical record completeness and years of education, BPS were elevated versus NBPS for all comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, including within sex-specific analyses (except for the male eating disorders comparison). The strongest elevations were noted within personality disorders (OR = 3.6, 95%CI = 2.6–5.1; P = 9.1 × 10 −13 ) and behavioral disorders (OR = 3.1, 95%CI = 2.3–4.3; P = 1.3 × 10 −11 ). In addition, findings show similar effect sizes within the sex-specific comparisons (Fig. 2 B and C ), regardless of sex, though all diagnoses were seen at higher frequencies within females, both within the BPS and NBPS.

Forest plot distribution of corrected odds ratios of the suicide-only clinical category comparisons (with 95% confidence interval represented by whiskers) within all subjects ( A ), male subjects ( B ), and female subjects ( C ). Labeling of comparison groups is as follows: BPS = individuals with bipolar disorder who died by suicide and NBPS = individuals without a diagnosis of bipolar disorder who died from suicide. Significant results are colored with overrepresentation shown in red and underrepresentation in green. Non-significant results are shown in blue. Results were corrected for multiple testing via the Benjamini–Hochberg method with an FDR of 0.05 for a total of 5 tests in the primary analysis ( A ) and 10 in the sex-specific analyses ( B , C ) and for critical covariates.

Genetic risk analysis across BPS, BPSA, BPNSA, and C

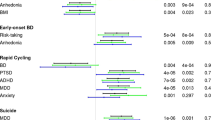

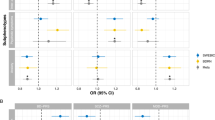

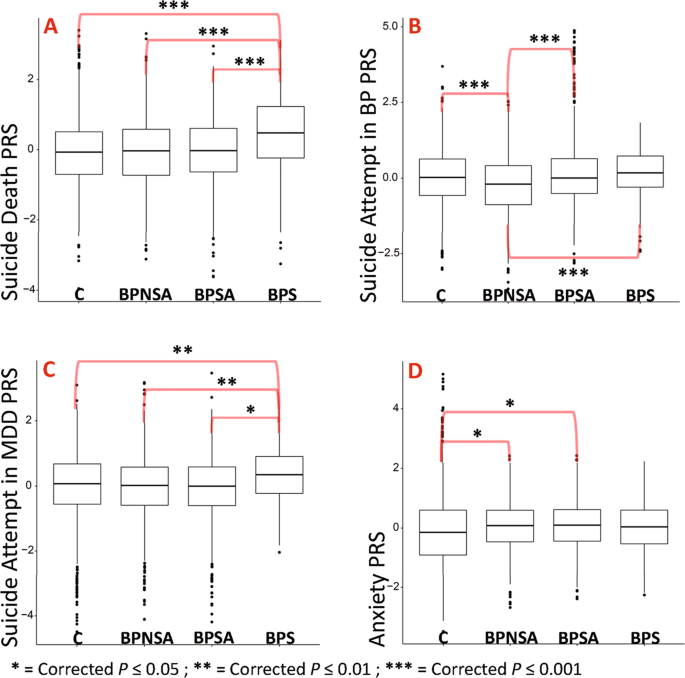

See Figs. 3 and 4 with full results in Supplementary Tables S6 and S7 .

Suicide attempt in MDD and BP and suicide death PRS.

Suicide death PRS (Fig. 3A ) was elevated in BPS versus BPSA (OR = 1.6, 95%CI = 1.4–1.9; P = 7.8 × 10 −10 ). Suicide attempt in BP PRS (Fig. 3B ) showed elevations in BPS versus BPNSA (OR = 1.5, 95%CI = 1.3–1.8; P = 1.9 × 10 −6 ) and BPSA versus BPNSA (OR = 1.5, 95%CI = 1.3–1.6; P = 1.1 × 10 −11 ). Suicide attempt in BP was also reduced in BPNSA versus C (OR = 0.7, 95%CI = 0.7–0.8; P = 4.2 × 10 −8 ). PRS for suicide attempt within major depressive disorder (Fig. 3C ) was elevated in BPS compared with all comparison groups, including versus BPSA (OR = 1.3, 95%CI = 1.1–1.6; P = 1.8 × 10 −2 ).

Anxiety, and neuroticism PRS.

Anxiety (Fig. 3D ; OR = 1.2, 95%CI = 1.1–1.3, P = 1.8 × 10 −2 ) and neuroticism (worry subcluster, not shown; OR = 1.2, 95%CI = 1.1–1.3, P = 6.0 × 10 −3 ) showed elevated PRS in BPSA versus C. Notably, PRS for anxiety and neuroticism also showed either significant or nominal elevation in BPS, BPSA, and BPNSA versus C, and ad-hoc comparisons of BPS, BPSA, and BPNSA combined into a single comparison group versus C showed P = 5.6 × 10 –5 for anxiety and 3.8 × 10 −4 for neuroticism.

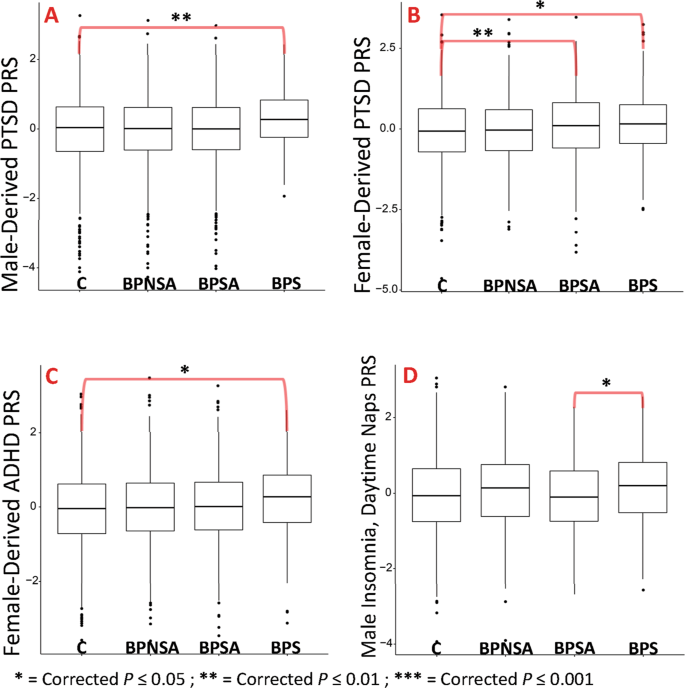

PTSD and behavioral PRS.

The PTSD GWAS published summary statistics for males, females, and all subjects [ 27 ]. All-subject (not shown; OR = 1.3, 95%CI = 1.1–1.5, P = 7.8 × 10 −3 ) and male-derived PTSD PRS (Fig. 4A ; OR = 1.3, 95%CI = 1.1–1.5, P = 8.0 × 10 −3 ) were elevated within BPS versus C. Female-derived PTSD PRS (Fig. 4B ), however, was elevated in both BPSA versus C (OR = 1.2, 95%CI = 1.1–1.3, P = 3.6 × 10 −3 ) and BPS versus C (OR = 1.2, 95%CI = 1.1–1.4, P = 2.5 × 10 −2 ). None of these comparisons remained significant in sex-specific analyses, but effect sizes were similar.

Female-derived ADHD PRS (Fig. 4C ) was elevated within BPS versus C (OR = 1.2, 95%CI = 1.1–1.4, P = 2.0 × 10 −2 ).

Sex-specific PRS.

Sex-specific PRS analyses (Supplementary Table S7 ) generally reproduced findings with similar effect sizes in both sexes, but often did not survive correction for multiple testing in the setting of smaller comparison groups. One new finding was identified, however: male-specific polygenic risk for insomnia (daytime napping subgroup, Fig. 4D ) was elevated in BPS versus BPSA with OR = 1.4, 95%CI = 1.1–1.7, P = 4.3 × 10 −2 .

BPS versus NBPS PRS.

PRS analyses of BPS versus NBPS (Supplementary Tables S8 – S9 ) showed no significant differences between groups, including within sex-specific analyses.

Box plot representations of the top findings from polygenic risk score association testing. Each plot represents comparison group ( x -axis) versus standardized polygenic risk score for the given phenotype ( y -axis). A Suicide death PRS. B Suicide attempt in bipolar disorder PRS. C Suicide attempt in MDD PRS. D Anxiety PRS. Comparison group definitions: BPS = individuals with bipolar disorder who died by suicide, BPSA = individuals with bipolar disorder who have a history of one or more suicide attempts, BPNSA = individuals with bipolar disorder who have no history of a suicide attempt, and C = comparison individuals without several common psychiatric illnesses per self-report [ 14 ]. Selected results shown; all displayed results have been corrected for multiple testing (Benjamini–Hochberg method with FDR of 0.05 correcting for 114 tests for all displayed results) and account for critical covariates. All shown results arose from evaluating all subjects (male and female).

Box plot representations of the top findings from polygenic risk score association testing. Each plot represents comparison group ( x -axis) versus standardized polygenic risk score for the given phenotype ( y -axis). A Male-derived PTSD PRS. B Female-derived PTSD PRS. C Female-derived ADHD PRS. D Male only (sex-specific) insomnia (daytime napping subgroup) PRS. Comparison group definitions: BPS = individuals with bipolar disorder who died by suicide, BPSA = individuals with bipolar disorder who have a history of one or more suicide attempts, BPNSA = individuals with bipolar disorder who have no history of a suicide attempt, and C = comparison individuals without several common psychiatric illnesses per self-report [ 14 ]. Selected results shown; all displayed results have been corrected for multiple testing (Benjamini–Hochberg method with FDR of 0.05 correcting for 114 tests for A – C and 204 tests for D ) and account for critical covariates. Note that sex-derived refers to PRS calculated based on weighted results from the given sex in the original GWAS. All results were evaluated from all (male and female) subjects in the current study with the exception of D , which was an evaluation of only males.

Suicide attempt is often used as a proxy for suicide death and, as such, frequently serves as the primary phenotype within studies of suicide. Suicide attempts and deaths, however, are separate groups that overlap. The unique resource of the USGRS dataset allowed more thorough exploration of suicide death within BP, identifying several potentially important clinical and genetic associations that may aid in identifying and differentiating those at highest risk for suicide attempt and death.

The role of trauma and its enduring effects in suicidal behavior

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to identify combined clinical and genetic evidence of factors that may distinguish risk for suicide death from attempt in BP. Specifically, PTSD and personality disorder diagnoses were strongly elevated in BPS versus BPSA. In addition, clinically informed genetic analyses identified elevated polygenic risk for PTSD in BPS. Trauma, and subsequent response, is a common factor in these findings. A history of trauma is required for PTSD [ 32 ] and is correlated with a more severe course [ 33 ] with an increased risk for suicidal behavior in BP [ 34 , 35 ]. Trauma is also frequently present in personality disorders [ 32 ] which are associated with suicidal behavior [ 36 ] and often comorbid with PTSD [ 37 ].

Such findings may also provide unifying support for the role of stress response pathways such as the hypothalamic pituitary axis (HPA) [ 38 ]. Prior evidence suggests that genetic disruption of the HPA-axis may interact with trauma/severe stress exposure to increase risk for suicide attempt [ 39 ]. This study provides novel evidence that traumatic disruption may increase risk of death from suicide. Indeed, recent evidence has arisen that early-life traumatic exposure in the setting of elevated polygenic risk for BP is significantly correlated with an increase in suicide attempts [ 40 ]. Taken together, the clinical and genetic findings of this study support the long-standing stress-diathesis model for suicidal behavior in BP [ 41 ], and specifically extend those findings to risk for suicide death.

Data from this study also demonstrate potentially important sex-related differences, with trauma-related diagnoses being driven by female BPS. In contrast, males and female BPS demonstrate relatively equal effects within polygenic risk for PTSD. This suggests potential differences in care seeking or clinical presentation in males that may not lead to the same diagnoses. BPS also showed elevated male- and female-derived PTSD PRS, but BPSA was only significantly associated with the female-derived PTSD PRS. This may indicate that genetic loci that interact with certain types of trauma, such as military trauma exposures identified within males of the PTSD GWAS [ 27 ], may be more closely associated with suicide death risk than attempt.

Finally, the clinical evaluation of BPS versus NBPS showed a striking overrepresentation of comorbid diagnoses, particularly trauma-associated diagnoses, but polygenic risk comparison yielded no significant findings. It is possible that genetic liability among BPS and NBPS is similar, but patients diagnosed with BP may receive additional clinical evaluation leading to identification of comorbid diagnoses such as PTSD.

Other potential risk factors

The clinically directed genetic analyses generated novel correlations of ADHD and insomnia polygenic risk in BPS versus C. ADHD diagnosis was also overrepresented in BPS versus NBPS. ADHD has been shown to be correlated with suicidal behavior [ 42 ] and may increase risk when comorbid with BP [ 43 ]. Together, ADHD and BP could be theorized to increase risk for “impulsive aggression”, a potentially important risk factor for suicidal behavior [ 44 ]. Insomnia has also been correlated with increased suicide behavior risk [ 45 ] and may be an important predictive factor for the presence of comorbid disease, such as PTSD [ 46 ]. It is notable that in comparing BPS to NBPS, 44.8% versus 18.3% of females and 28.4% versus 13.2% of males had a concurrent diagnosis of insomnia, respectively. This suggests that female BPS are more frequently diagnosed with insomnia despite a male-driven genetic finding, which may indicate sex-specific differences in diagnosis or care seeking.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Among these is modest sample size, though the assessed sample of BPS is the largest known sample of its kind. Also, replication is currently not possible as no comparable BPS sample is currently known to exist. Though not the focus of this study, efforts are also underway to collect larger BPSA and BPNSA samples with clinical data to allow more effective comparisons of these groups.

The use of two distinct cohorts introduced several potential limitations. Different genotyping arrays led to a limited number of overlapping variants, somewhat limiting the efficacy of imputation and PRS calculation. In addition, population ascertainment differed substantially: a general population sample (USGRS) versus an assembled research sample (NIMH), both with strengths but potentially biased comparisons. For example, the USGRS samples were not evaluated with a comprehensive diagnostic interview, potentially missing important comorbidities and weakening current associations. It must also be noted that diagnoses within a population sample arise only through individuals seeking clinical encounters and are less likely to represent every diagnosis an individual might have. This leads to a high likelihood that individuals with undiagnosed BP may be present within NBPS, potentially weakening comparisons between these groups. Conversely, the NIMH sample represents voluntary cohorts that may not adequately reflect the general population, but who were rigorously assessed by multiple providers via a consistent, extensive questionnaire to provide best estimate diagnoses. Despite this rigorous evaluation, however, all potentially relevant comorbidities, and particularly the personality disorders other than antisocial personality disorder, were not systematically evaluated as part of the core questionnaire, being identified through family informant, medical records, and early life trauma evaluation which were not available for all subjects. Indeed, it was noted that <1% of BP individuals within the NIMH cohort were diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, though a recent meta-analysis of the frequency of comorbid borderline personality disorder in bipolar disorder predicted an average of 21.6% [ 47 ], suggesting that many diagnoses may have been missed in this cohort. Finally, the evaluation of only Northern European subjects limits the generalizability of this study and was necessitated by a limited number of samples from other ethnicities. Ongoing efforts to collect a larger, more diverse, and cohesive sample are underway. Despite these inherent challenges, however, it is notable that the comparison of such datasets is necessitated by the relative rarity of these phenotypes (particularly suicide death) and is supported by evidence of a convergent finding within clinical and genetic data evaluations of prior trauma as a potential factor in suicide death risk in BP, illustrating the potential power of this complimentary approach.

This study represents the first large-scale evaluation of suicide death in BP to utilize a combined clinical and genetic approach. In identifying converging evidence of factors specifically associated with suicide death, particularly prior trauma and its associated phenotypes, this study provides potentially tractable targets for future evaluation and indicates the need to specifically collect and evaluate individuals who have died from suicide to best characterize risk factors for this preventable outcome. Findings may serve to improve current screening measures for suicide death risk and, ultimately, help reduce death by suicide.

Turecki G, Brent DA, Gunnell D, O'Connor RC, Oquendo MA, Pirkis J, et al. Suicide and suicide risk. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:74. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0121-0.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Owens D, Horrocks J, House A. Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm. Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:193–9. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.181.3.193.

Bostwick JM, Pabbati C, Geske JR, McKean AJ. Suicide attempt as a risk factor for completed suicide: even more lethal than we knew. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:1094–100. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15070854.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hawton K, Fagg J. Suicide, and other causes of death, following attempted suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;152:359–66. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.152.3.359.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Valtonen H, Suominen K, Mantere O, Leppämäki S, Arvilommi P, Isometsä ET. Suicidal ideation and attempts in bipolar I and II disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1456–62.

Article Google Scholar

Gonda X, Pompili M, Serafini G, Montebovi F, Campi S, Dome P, et al. Suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder: epidemiology, characteristics and major risk factors. J Affect Disord. 2012;143:16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.04.041.

Miller JN, Black DW. Bipolar disorder and suicide: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22:6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-020-1130-0.

Chen YW, Dilsaver SC. Lifetime rates of suicide attempts among subjects with bipolar and unipolar disorders relative to subjects with other Axis I disorders. Biol. psychiatry. 1996;39:896–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3223(95)00295-2.

Yeh HH, Westphal J, Hu Y, Peterson EL, Williams LK, Prabhakar D, et al. Diagnosed mental health conditions and risk of suicide mortality. Psychiatr. Serv. 2019;70:750–7. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800346.

Docherty AR, Shabalin AA, DiBlasi E, Monson E, Mullins N, Adkins DE, et al. Genome-wide association study of suicide death and polygenic prediction of clinical antecedents. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177:917–27. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.19101025.

Genomic survey of bipolar illness in the NIMH genetics initiative pedigrees: a preliminary report. Am J Med. Genet. 1997;74:227–37.

Smith EN, Bloss CS, Badner JA, Barrett T, Belmonte PL, Berrettini W, et al. Genome-wide association study of bipolar disorder in European American and African American individuals. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:755–63. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2009.43.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

McMahon FJ, Akula N, Schulze TG, Muglia P, Tozzi F, Detera-Wadleigh SD, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies a risk locus for major mood disorders on 3p21.1. Nat Genet. 2010;42:128–31. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.523.

Sanders AR, Levinson DF, Duan J, Dennis JM, Li R, Kendler KS, et al. The Internet-based MGS2 control sample: self report of mental illness. Am. J. psychiatry. 2010;167:854–65. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09071050.

Kohn MA, S. J. Sample Size Calculators , 2021, https://sample-size.net/sample-size-proportions/ .

Willour VL, Seifuddin F, Mahon PB, Jancic D, Pirooznia M, Steele J, et al. A genome-wide association study of attempted suicide. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:433–44. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2011.4.

American Psychiatric Association. Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-III . American Psychiatric Association; 1982.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic criteria from DSM-IV . The Association; 1994.

Nurnberger JI Jr, Blehar MC, Kaufmann CA, York-Cooler C, Simpson SG, Harkavy-Friedman J, et al. Diagnostic interview for genetic studies. Rationale, unique features, and training. NIMH Genetics Initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:849–59. discussion 863-844.

Smith EN, Koller DL, Panganiban C, Szelinger S, Zhang P, Badner JA, et al. Genome-wide association of bipolar disorder suggests an enrichment of replicable associations in regions near genes. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002134. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002134.

Das S, Forer L, Schönherr S, Sidore C, Locke AE, Kwong A, et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1284–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3656.

R: A Language and Environment for Statisitcal Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2020).

Martin J, Walters RK, Demontis D, Mattheisen M, Lee SH, Robinson E, et al. A genetic investigation of sex bias in the prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;83:1044–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.11.026.

Demontis D, Walters RK, Martin J, Mattheisen M, Als TD, Agerbo E, et al. Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat Genet. 2019;51:63–75. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0269-7.

Otowa T, Hek K, Lee M, Byrne EM, Mirza SS, Nivard MG, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of anxiety disorders. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:1391–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2015.197.

Jansen PR, Watanabe K, Stringer S, Skene N, Bryois J, Hammerschlag AR, et al. Genome-wide analysis of insomnia in 1,331,010 individuals identifies new risk loci and functional pathways. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:394–403. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0333-3.

Nievergelt CM, Maihofer AX, Klengel T, Atkinson EG, Chen CY, Choi KW, et al. International meta-analysis of PTSD genome-wide association studies identifies sex- and ancestry-specific genetic risk loci. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4558. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12576-w.

Mullins N, Bigdeli TB, Børglum AD, Coleman J, Demontis D, Mehta D, et al. GWAS of suicide attempt in psychiatric disorders and association with major depression polygenic risk scores. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176:651–60. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18080957.

Nagel M, Jansen PR, Stringer S, Watanabe K, de Leeuw CA, Bryois J, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for neuroticism in 449,484 individuals identifies novel genetic loci and pathways. Nat Genet. 2018;50:920–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0151-7.

Euesden J, Lewis CM, O’Reilly PF. PRSice: polygenic risk score software. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1466–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu848.

Schrijvers DL, Bollen J, Sabbe BG. The gender paradox in suicidal behavior and its impact on the suicidal process. J Affect Disord. 2012;138:19–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.050.

American Psychiatric Association. & American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 . 5th edn, American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

Etain B, Aas M, Andreassen OA, Lorentzen S, Dieset I, Gard S, et al. Childhood trauma is associated with severe clinical characteristics of bipolar disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:991–8. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13m08353.

Schaffer A, Isometsä ET, Azorin JM, Cassidy F, Goldstein T, Rihmer Z, et al. A review of factors associated with greater likelihood of suicide attempts and suicide deaths in bipolar disorder: Part II of a report of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force on Suicide in Bipolar Disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:1006–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415594428.

Park, YM, Shekhtman, T, Kelsoe, JR. Effect of the Type and Number of Adverse Childhood Experiences and the Timing of Adverse Experiences on Clinical Outcomes in Individuals with Bipolar Disorder. Brain Sci. 2020;10: https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10050254 .

Hawton, K & Heeringen, K v. The International Handbook of Suicide and Attempted Suicide . Wiley; 2000.

Jowett S, Karatzias T, Albert I. Multiple and interpersonal trauma are risk factors for both post-traumatic stress disorder and borderline personality disorder: a systematic review on the traumatic backgrounds and clinical characteristics of comorbid post-traumatic stress disorder/borderline personality disorder groups versus single-disorder groups. Psychol Psychother. 2020;93:621–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12248.

Jokinen J, Nordstrom P. HPA axis hyperactivity and attempted suicide in young adult mood disorder inpatients. J Affect Disord. 2009;116:117–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.10.015.

Guillaume S, Perroud N, Jollant F, Jaussent I, Olié E, Malafosse A, et al. HPA axis genes may modulate the effect of childhood adversities on decision-making in suicide attempters. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:259–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.10.014.

Wilcox HC, Fullerton JM, Glowinski AL, Benke K, Kamali M, Hulvershorn LA, et al. Traumatic stress interacts with bipolar disorder genetic risk to increase risk for suicide attempts. J Am Acad Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2017;56:1073–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.09.428.

van Heeringen K, Mann JJ. The neurobiology of suicide. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70220-2.

Furczyk K, Thome J. Adult ADHD and suicide. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2014;6:153–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-014-0150-1.

Lan WH, Bai YM, Hsu JW, Huang KL, Su TP, Li CT, et al. Comorbidity of ADHD and suicide attempts among adolescents and young adults with bipolar disorder: a nationwide longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2015;176:171–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.02.007.

Brent DA, Mann JJ. Family genetic studies, suicide, and suicidal behavior. Am J Med Genet Part C, Semin Med Genet. 2005;133C:13–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.30042.

McCall WV, Black CG. The link between suicide and insomnia: theoretical mechanisms. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15:389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-013-0389-9.

Wright KM, Britt TW, Bliese PD, Adler AB, Picchioni D, Moore D. Insomnia as predictor versus outcome of PTSD and depression among Iraq combat veterans. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67:1240–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20845.

Fornaro M, Orsolini L, Marini S, De Berardis D, Perna G, Valchera A, et al. The prevalence and predictors of bipolar and borderline personality disorders comorbidity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;195:105–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.040.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the American Foundation of Suicide Prevention (AFSP) BSG-1-005-18 (VW and HC); the National Institute of Mental Health, R01MH122412 (HC), R01MH123489 (HC), R01MH123619 (AD), the Clark Tanner Foundation (HC and EM), and the Utah Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health (HC). Processing of Utah suicide samples was done with assistance from the GCRC M01-RR025764 from the National Center for Research Resources. Genotyping of these samples was done with support from Janssen Research & Development, LLC to the University of Utah. We thank the University of Utah psychiatry residency research track for their support. Partial support for all datasets within the Utah Population Database was provided by the University of Utah Huntsman Cancer Institute. We thank the staff of the Utah Office of the Medical Examiner for their work in making the collection of samples from suicide deaths possible. Please see the Supplementary materials and methods for full NIMH sample acknowledgement.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychiatry & Huntsman Mental Health Institute, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

Eric T. Monson, Andrey A. Shabalin, Anna R. Docherty, Emily DiBlasi, Amanda V. Bakian, Douglas Gray, Brooks Keeshin, Sheila E. Crowell & Hilary Coon

Department of Family and Preventative Medicine, Division of Public Health, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

Amanda V. Bakian

Neuroscience Therapeutic Area, Janssen Research and Development, Titusville, NJ, USA

Qingqin S. Li

VISN 19 Rocky Mountain MIRECC, George E. Wahlen VA Medical Center, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

Douglas Gray

Department of Pediatrics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

Brooks Keeshin

Department of Psychology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

Sheila E. Crowell

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

Department of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, NY, USA

Niamh Mullins

Department of Genetics and Genomic Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, NY, USA

Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA

Virginia L. Willour

Department of Biomedical Informatics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

Hilary Coon

Division of Genetic Epidemiology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Eric T. Monson .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

Dr. Qingqin Li is an investigator at Janssen Research, LLC. No other conflicts of interest or financial disclosures are reported by any of the other authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Online supplement, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Monson, E.T., Shabalin, A.A., Docherty, A.R. et al. Assessment of suicide attempt and death in bipolar affective disorder: a combined clinical and genetic approach. Transl Psychiatry 11 , 379 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01500-w

Download citation

Received : 01 February 2021

Revised : 18 June 2021

Accepted : 23 June 2021

Published : 07 July 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01500-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Integrating summary information from many external studies with population heterogeneity and a study of covid-19 pandemic impact on mental health of people with bipolar disorder.

- Peisong Han

- Melvin G. McInnis

Statistics in Biosciences (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Allkins S Perinatal mental health support in the UK. Br J Midwifery. 2023; 31:(9) https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2023.31.9.485

Bergink V, Rasgon N, Wisner K Postpartum psychosis: madness, mania, and melancholia in motherhood. Am J Psychiatry. 2016; 173:(12)1179-1188 https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16040454

Huang YC, Chen HH, Yeh ML, Chung YC Case studies combined with or without concept maps improve critical thinking in hospital-based nurses: a randomized-controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012; 49:(6)747-754 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.01.008

Saving lives, improving mothers' care: core report: lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland confidential enquiries into maternal deaths and morbidity 2018–20. 2022. https//www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/maternal-report-2022/MBRRACE-UK_Maternal_MAIN_Report_2022_v10.pdf

McAllister-Williams RH, Baldwin DS, Cantwell R British association for psychopharmacology consensus guidance on the use of psychotropic medication preconception, in pregnancy and postpartum. J Psychopharmacol. 2017; 31:(5)519-552 https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881117699361

Munk-Olsen T, Lui X, Viktorin A Maternal and infant outcomes associated with Lithium use in pregnancy: an international collaborative meta-analysis of six cohort studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018; 5:(8)644-645 https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30180-9

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bipolar disorder: assessment and management. 2020. https//www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185/chapter/Introduction

National Mental Health Division. Specialist perinatal mental health services; a model of care for Ireland. 2017. https//www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/4/mental-healthservices/specialist-perinatal-mental-health

NHS. Pan-London perinatal mental health networks pre-birth planning: best practice toolkit for perinatal mental health services. 2019. https//www.transformationpartnersinhealthandcare.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Pre-birth-planning-guidance-for-Perinatal-Mental-Health-Networks.pdf

Noonan M, Doody O, Jomeen J, Galvin R Midwives' perceptions and experiences of caring for women who experience perinatal mental health problems: an integrative review. Midwifery. 2017; 45:56-71 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2016.12.010

O'Hare MF, Manning E, O'Herlihy CCork: Hackett Retrographics; 2015

Peirson L, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Mowat D Building capacity for evidence informed decision making in public health: a case study of organizational change. BMC Public Health. 2012; 12:(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-137

Ritter PS, Marx C, Bauer M, Lepold K, Pfennig A The role of disturbed sleep in the early recognition of bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Bipolar Disorders. 2011; 13:(3)227-237 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00917.x

Rosso G, Umberto GA, Di Salvo G Lithium prophylaxis during pregnancy and the postpartum period in women with lithium-responsive bipolar I disorder. Arch Womens Mental Health. 2016; 19:(2)429-432 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0601-0

Spinelli MG Postpartum psychosis: detection of risk and management. Am J Psychiatry. 2009; 166:(4)405-408 https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08121899

Wesseloo R, Kamperman AM, Munk-Olsen T, Pop VJM, Kushner SA, Bergink V Risk of postpartum relapse in bipolar disorder and postpartum psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2016; 173:(2)117-127 https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15010124

Kathleen's journey: improving mental health outcomes for women with bipolar affective disorder

Pauline Walsh

Health Service Executive, Ireland

View articles · Email Pauline

Margaret Graham

Department of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Limerick

View articles

Mas Mahady Mohamad

Health Service Executive, Ireland; School of Medicine, University of Limerick

For most women, pregnancy and the postpartum period are times of great joy and expectation. However, for women with a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder, there is an exceptionally high risk of deterioration in their mental health. There is the real possibility of developing postpartum psychosis, possibly requiring acute psychiatric admission and being separated from their baby. This can have devastating consequences for a woman, her baby, the family and society. Multiple services/disciplines across primary, secondary and tertiary care settings need to work together to enhance outcomes for these women. In Ireland, a relatively new collaborative way of working is emerging, as specialist perinatal mental health teams are developed. This case review aims to illustrate the complexities of and potential in collaborative team working to support a woman with a pre-existing a mental health disorder, and her family, during pregnancy. This was done through a specialist perinatal mental health teams collaboration co-ordinated by a clinical nurse specialist.

The British Journal of Midwifery's September editorial, ‘perinatal mental health support in the UK’ ( Allkins, 2023 ), highlighted the need to support women with mental health problems during pregnancy. This article focuses on a collaborative approach to supporting a woman with a pre-existing mental health condition.

The development of perinatal mental health services in Ireland is guided by their counterparts internationally, particularly in the NHS. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence ( NICE, 2020 ) stated that the population risk for bipolar affective disorder is approximately 1%. Nevertheless, for women who have a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder, there can be significant impact on both the individual and their family. The condition is characterised by periods of depression and periods of hypomania or mania; in some instances there can be features of both depression and mania during the one episode. Common symptoms associated with these mood changes are listed in Table 1 .

Source: NICE, 2020

A systematic review by Wesseloo et al (2016) established that for women with a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder, there was a relapse risk for 1 in 3 women in the postpartum period. These women were more likely to require inpatient psychiatric admission than women with any other psychiatric diagnosis, including schizophrenia. Ireland has no mother and baby unit ( National Mental Health Division, 2017 ). Therefore, unfortunately, for women with bipolar affective disorder who require inpatient treatment, there is a possibility that they may be admitted to a general adult psychiatry ward, most likely without their baby.

Women with bipolar affective disorder are at increased risk of developing postpartum psychosis, a severe and potentially life-threatening condition for both mother and baby. Approximately 5% of women affected by postpartum psychosis end their life by suicide and 4% commit infanticide ( Spinelli, 2009 ). As a result of the severity of postpartum psychosis and the increased risk to the life of the mother and her baby, all healthcare professionals need to be aware of the symptoms of the condition, in order to identify women who are more at risk of developing it. An estimated 134 women in Ireland experience postpartum psychosis each year, although it is thought this number under-represents the true incidence rates, because of challenges around how diagnoses are reported and recorded in different areas. ( National Mental Health Division, 2017 ).

Interdisciplinary working in perinatal mental health

Given the statistics related to women with bipolar affective disorder, promoting interdisciplinary mental health services is critical across the perinatal period ( Knight et al, 2022 ). The specialist perinatal mental health services, and specifically the clinical nurse specialist, have key roles and responsibilities in the care of women with bipolar affective disorder, which often require them to provide and co-ordinate shared care. The clinical nurse specialist's responsibilities include patient focus, patient advocacy, education and training. The principles of care for pregnant women with bipolar affective disorder include co-ordination across services, with clear responsibilities for each distinct time period outlined ( NICE, 2020 ).

As registered advanced nurse practitioners are introduced to perinatal mental health services in Ireland, it is anticipated that leading and co-ordinating episodes of care for such vulnerable women falls in the remit of registered advanced nurse practitioner. Clinical case reviews have proved valuable in nursing; researchers such as Huang et al (2012) found that they can inform nurses’ decision-making skills during episodes of complex care. Raising midwives’ awareness of risk factors and presentations for mental illness enhances confidence when caring for these women (Noonan et al, 2018). This approach requires healthcare professionals to work in close collaboration and is illustrated though Kathleen's journey, organised around a clinical case study framework ( Box 1 ). Permission was sought from the women involved in this case review, and ‘Kathleen’ is a pseudonym.

Box 1.Case and backgroundKathleen (pseudonym) is a 33-year-old woman, recently married and in her first pregnancy. She lives with her husband and parents, and works 30 hours/week in the family business. She has a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder, type 1, since the age of 19 years. She has experienced depressive episodes, which featured significant and life-threatening self-harm episodes. During other episodes of depression, she has experienced psychotic symptoms. She has experienced several episodes of hypomania and one episode of mania. Kathleen has been hospitalised for her safety on eight occasions, with one of these admissions being on an involuntary basis. The duration of the admissions ranged from 2 weeks to 4 months. Her last admission was 7 years ago. In the past 7 years, she has remained stable on a pharmacological regime, including lithium 1000mg/day. She planned a pregnancy with her husband but did not discuss this with her adult mental health team and was not offered the pre-conception assessment service from the local specialist perinatal mental health team. Physically, her pregnancy was uncomplicated until approximately 28/40 weeks, when she developed gestational diabetes, which was managed with diet and lifestyle moderations.

Kathleen's journey demonstrating interdisciplinary working

Prior to becoming pregnant, Kathleen was actively engaged with a community mental health team, with attendance every 3 months for review and monitoring of lithium plasma levels. She had not been offered or requested any preconception mental health assessment. When Kathleen became pregnant (discovered at 5/40 weeks) and informed her community mental health team, they immediately linked with the specialist perinatal mental health team to arrange an urgent pharmacological regime review.

Midwifery and obstetric care was under the consultant obstetrician who leads care for women with severe and enduring mental illness. A joint clinic is run with the specialist perinatal mental health team and Kathleen attended both clinics within 3 days of initial contact.

Kathleen was initially assessed by the perinatal consultant psychiatrist and a full history was taken. Specific attention was given to her prescription of lithium (1000 mg/day). This was a long-term prescription since her acute episodes of mania and depression. Once stabilised on this medication 7 years ago, with good quality of life, she experienced no readmissions or relapses, returned to work, started a relationship and became pregnant. However, some studies have associated lithium with a slight increase in birth defects, most commonly cardiac defects, so careful consideration of this medication was needed. Munk-Olsen et al (2018) reported no association between lithium and birth defects. Pharmacological decisions during pregnancy are guided by the British Association for Psychopharmacology's ( McAllister-Williams et al, 2017 ) consensus guidance on the use of psychotropic medication preconception, in pregnancy and postpartum. These guidelines highlight the need to balance the risks to the fetus versus the potential risks/benefits of the medication for the mother, and to consider the risks associated with relapse or untreated perinatal mental illness ( Table 2 ). It was decided that reducing Kathleen's lithium dose could potentially lead to relapse and the risk factors associated with managing an acute episode while pregnant were considered.

Adapted from: McAllister-Williams et al (2017)

Kathleen was advised that her lithium levels would be reviewed or monitored monthly for the first and second trimester, as plasma levels tend to decrease from as early as 6/40 weeks, which could potentially result in sub-therapeutic plasma levels, most likely requiring an increase in lithium ( Rosso et al, 2016 ). At this stage, Kathleen was referred to the clinical nurse specialist in the specialist perinatal mental health team, with the expectation of developing a therapeutic alliance and commencing engagement regarding the pre-birth planning meeting. It was expected that they would work together to develop plans to maintain mental stability, and provide early intervention if any deterioration occurred in mental state during the pregnancy and postpartum periods. Available parenting supports in the local community were explored, and it was decided that the appropriate referrals would be made later in the pregnancy.

Pre-birth planning meeting

A pre-birth planning meeting is a valuable mechanism, bringing together key healthcare professionals with women and their families to plan care for the remainder of pregnancy, hospital admission and the postpartum period ( NHS, 2019 ). Pre-birth planning meetings generally occur around 32/40 weeks and a copy of the minutes from this meeting is kept by all professionals involved. A copy was also held by Kathleen, in her case.

The clinical nurse specialist facilitated Kathleen to outline her mental health history, her early warning signs of relapse and the supports she had available to her. Kathleen's self-efficacy was encouraged and supported to facilitate her to tell her story and be an active participant in her plan of care. The meeting included Kathleen and her husband, the clinical nurse specialist, perinatal consultant psychiatrist and the registrar from the specialist perinatal mental health team. The community mental health nurse, who was familiar with Kathleen and engaged in her care, attended on behalf of the community mental health team. Both the consultant obstetrician and registrar attended, as well as midwives from the antenatal clinic, and the antenatal, labour and postnatal wards. Kathleen's GP and public health nurse were also in attendance. The meeting therefore included professionals across primary, secondary and tertiary services, encompassing obstetrics, mental health and public health services.

This meeting followed the format outlined by the NHS (2019) pre-birth planning: best practice toolkit for perinatal mental health services. One major early warning sign and potential trigger for deterioration of Kathleen's mental state was reduced or disturbed sleep. Kathleen described a relapse pattern where she may be overstimulated, and have difficulty initiating sleep and falling into a deep sleep. This would have a negative impact on her mood and could potentially be a prodrome for a manic episode ( Ritter et al, 2011 ). The risk of postpartum deterioration was discussed in terms of the potential risks to herself and the baby, as well as risks from others to Kathleen. She had a significant history of deliberate self-harm via a potentially lethal method, as well as risks associated with her character, as when she was manic, she behaved in a way that was not in keeping with her personality.

Kathleen's strengths and protective factors were outlined, which included her concordance with the pharmacological regime, the 7-year period of being mentally stable and her engagement with both the specialist perinatal mental health team and community mental health team. Kathleen lived with her husband and parents, who were all supportive towards her in terms of her emotional and physical wellbeing.

The specifics of Kathleen's care for each stage of pregnancy and postpartum were discussed, and key care commitments were made ( Table 3 ).

As is often true for complex cases, some aspects could not be predicted. Kathleen was diagnosed with gestational diabetes, which was well controlled. However, around 38/40 weeks, her blood sugars became harder to regulate. Baby size for gestational age was large and the decision was taken to plan induction. When it began, a lithium level revealed her plasma level was climbing to potentially toxic levels. This necessitated an abrupt withdrawal of lithium while Kathleen was in labour,, with commencement of intravenous fluids to increase hydration and reduce the potential for toxicity. To counter the abrupt withdrawal of lithium, a low dose of an anti-psychotic, Olanzapine, was prescribed.

Kathleen delivered a healthy baby boy 16 hours after induction began and while she did miss some sleep, the Olanzapine aided sleep the following night. Lithium was recommenced on day 1 postpartum, at the pre-pregnancy dose of 1000mg/day with daily lithium level monitoring. Kathleen was facilitated with a quiet single room with less stimulation, her baby was fed overnight, and she was facilitated with increased visiting from her husband and daily reviews by both the obstetric and specialist perinatal mental health team. Her baby was reviewed by the neonatology team, who reported the baby as healthy and well. Kathleen was discharged on day 6 postpartum and was mentally well and stable, having not experiencing any fluctuations in mood.

During each day of admission, the specialist perinatal mental health team liaised with, and provided guidance and support to, midwives on the wards. These midwives were well placed to observe subtle changes in mental state and were informed of what symptoms to look for and the potential impact of any changes to mental state. This specific protected time between the specialist perinatal mental health team and ward midwives facilitated collaboration between the different disciplines, enabling a sharing of knowledge and experience.

Kathleen's outcome was what every mother hopes for; she left the hospital with both herself and her baby healthy and happy. She continues to be mentally well, now 18 weeks’ postpartum. Given the high risk of relapse and the significant potential for a postpartum psychosis, she attributes this outcome to the ‘safety net’ provided by the professionals involved. In this case, individual members of the team worked well together. Different mental health teams provided shared care in a way that was not familiar to them. The obstetric and mental health teams worked side by side, developing and adjusting care plans as required, providing robust care to Kathleen. Midwives in the hospital, and community services engaged with each other, developing new relationships and respect for each other's roles and practices. Community colleagues, such as the public health nurse and GP, engaged with the specialist perinatal mental health, community mental health and obstetric teams in a way that was not familiar to them. All interdisciplinary professionals working in their own fields came together for a common goal, to give Kathleen the best chance to avoid relapse. Kathleen and her family did not experience the trauma of a postpartum relapse.

Conclusions

Pregnancy and the postpartum period are a special time for a woman's life. Women who have enduring severe mental health issues, such as bipolar affective disorder, require support during such a vulnerable time. Women with bipolar affective disorder have the potential to become seriously mentally ill, with possibly devastating consequences for women, babies, families and society in general. As professionals, it is our responsibility to develop our services and respond to meet the needs of these women. This case review demonstrates that when services collaborate, outcomes for vulnerable perinatal women are improved. Discussing Kathleen's journey illustrates the clinical and organisational collaboration with women and their partners during this high-risk time. The case review strives to promote discussion of the complexities surrounding the perinatal health needs and support for women and their families.

‘My baby is 18 weeks old now. I am mentally well and stable. Having all the right mental health and obstetric supports in place supported me to become the mother I hoped and dreamed I would be’ Kathleen

Education and support for midwives is essential in continuing to promote quality care with women with complex needs. It is critical to increase knowledge of the mental healthcare needs of this vulnerable cohort of women among midwives and obstetricians, and similarly for mental health practitioners to increase their understanding of pregnancy and its potential impacts on a woman's mental health.

- When services are open to new ways of working, great work can be done for the benefit of women.

- Pre-birth planning meetings are an essential means of bringing many services together to form a strong safety net for vulnerable populations of women, such as those with bipolar affective disorder.

- Most professionals in healthcare have a goal to achieve good outcomes for patients; bringing together like-minded professionals for the benefit of the patient is a positive experience for all involved.

CPD reflective questions

- Is engaging in this way of team working a new concept?

- What would you foresee these challenges to working in this way?

- What are the potential benefits of working in this way?

- Could you envision working in this way within your healthcare setting?

- How do you think Kathleen felt at the pre-birth planning meeting? In terms of discussing her mental health history and planning for the future?

- Open access

- Published: 15 May 2024

The clinical significance of emotional urgency in bipolar disorder: a scoping review

- Wen Lin Teh 1 , 2 ,

- Sheng Yeow Si 3 ,

- Jianlin Liu 1 ,

- Mythily Subramaniam 1 &

- Roger Ho 2 , 4

BMC Psychology volume 12 , Article number: 273 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

179 Accesses

Metrics details

Emotional urgency, defined as a trait concept of emotion-based impulsivity, is at least moderately associated with general psychopathology. However, its clinical significance and associations with clinically relevant features of bipolar disorder remain unclear. This scoping review aims address this gap by determining the extent of evidence in this niche scope of study.

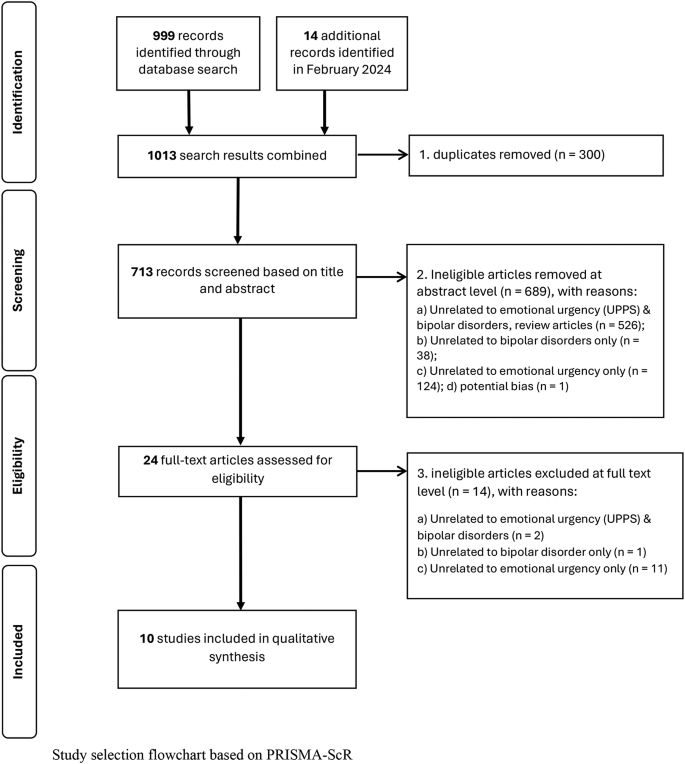

Evidence of between-group differences of positive and negative urgency, its associations with mood severity, and all peripheral associations related to illness and psychosocial outcomes were synthesized based on PRISMA checklists and guidelines for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR).

Electronic databases were searched for articles published between January 2001 and January 2024. A total of 1013 entries were gathered, and a total of 10 articles were included in the final selection after the removal of duplicates and ineligible articles.

Differences in urgency scores between bipolar disorder and healthy controls were large (Cohen’s d ranged from 1.77 to 2.20). Negative urgency was at least moderately associated with overall trauma, emotional abuse, neglect, suicide ideation, neuroticism, and irritable/cyclothymic temperament, whereas positive urgency was at least moderately associated with various aspects of aggression and quality of life. Positive but not negative urgency was associated with quality of life in bipolar disorder.

Large between-group differences found for emotional urgency in bipolar disorder imply large clinical significance. Emotional urgency was associated with worse clinical features and outcomes. Given the high clinical heterogeneity of the disorder, emotional urgency may be an important phenotype indicative of greater disorder severity.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD), which encompasses primarily bipolar I and II disorders, is a subcategory of mood disorders that is characterized by episodes of mania and depression causing significant dysfunction. A diagnosis of bipolar II disorder requires at least one depressive episode and a hypomanic episode, whereas a diagnosis of bipolar I requires only a manic episode [ 1 , 2 ], though, research has shown that that the majority of individuals with bipolar I (94.2%) do report having experienced at least one depressive episode [ 3 ]. High mortality, disease burden, poor psychosocial functioning, and well-being, are several adverse outcomes associated with bipolar disorders [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ].