On a mission to end educational inequality for young people everywhere.

ZNotes Education Limited is incorporated and registered in England and Wales, under Registration number: 12520980 whose Registered office is at: Docklands Lodge Business Centre, 244 Poplar High Street, London, E14 0BB. “ZNotes” and the ZNotes logo are trademarks of ZNotes Education Limited (registration UK00003478331).

Case Study: Warsaw Ghetto

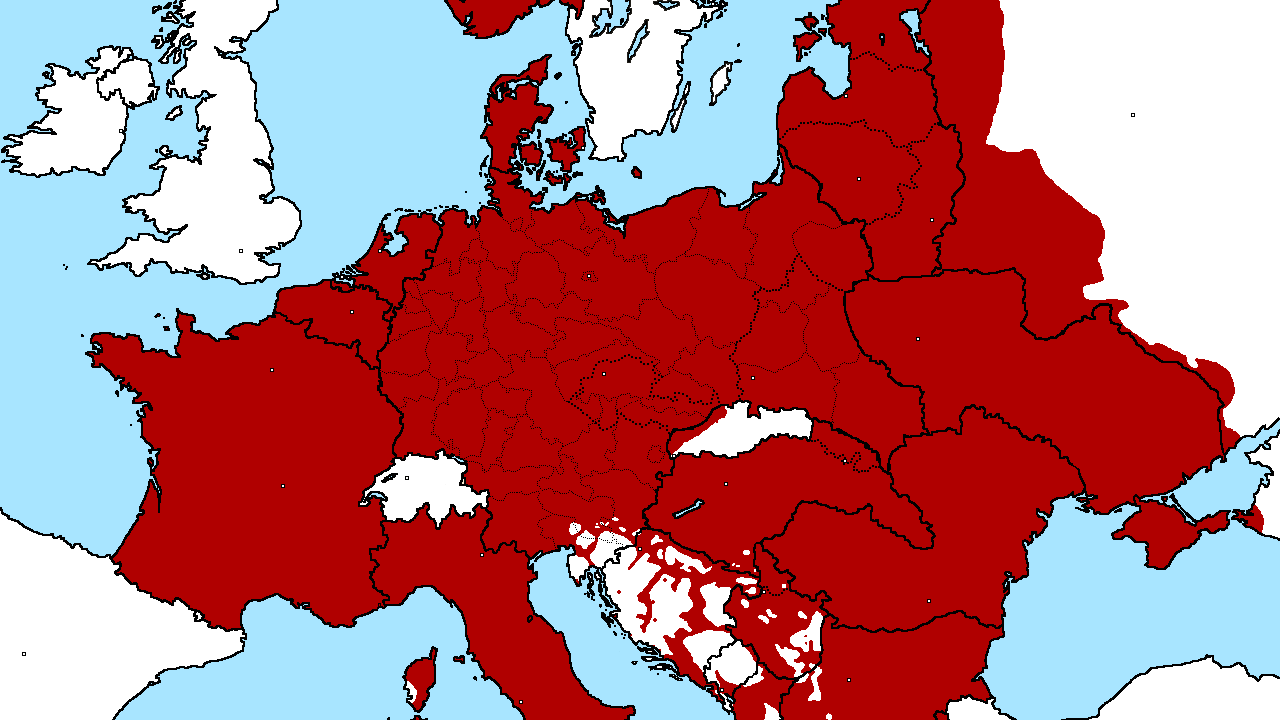

This map shows the boundaries of the Warsaw Ghetto, where 400,000 people were incarcerated. It was published by the Yiddish Scientific Institute in 1944.

Courtesy of The Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.

This excerpt from 7 November 1939 is taken from Hans Frank’s diary. Hans Frank was the leader of the General Government. This was an area of Poland that was controlled by Germany after invasion in September 1939. The diary shows notes from a meeting between high ranking Nazis, and states that a special ghetto ‘has to be established for the Jews’ in Warsaw.

This document is a translation used in the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials.

Prior to the Second World War, Warsaw was the capital of Poland. The city had 1.3 million inhabitants, of which 380,567 were Jewish. This was the largest Jewish community in Europe at the time.

The Nazis occupied Warsaw on 29 September 1939, four weeks after invading Poland. The Jewish population in Warsaw had grown following orders from Heydrich to concentrate Jews in cities and towns, but a ghetto was not decreed until 12 October 1940.

The ghetto was segregated from the rest of the population by a wall and sealed on 15 November 1940. Jewish policemen guarded the inside of the wall, and Nazi and Polish officers patrolled the outside. Only those with special permits could leave the ghetto. Over 400,000 people were imprisoned.

Conditions inside the Warsaw Ghetto

Once the ghetto had been sealed, food quickly became scarce. Here a woman is pictured shopping at the ghetto market.

Photographer unknown.

Due to the scarcity of food, smuggling became common. To get food into the ghetto smugglers would scale the walls using ladders, use connecting buildings, the sewers, or workers who regularly entered and left the ghetto.

Living conditions in the ghetto were poor, with limited sanitation, medicine, and space.

Children suffered harsh circumstances in the Warsaw Ghetto. Here, two children are pictured huddling on the pavement.

Conditions inside the Warsaw Ghetto were very poor. An average of over seven people shared each room. Whilst the Jewish Council administered the ghetto, they did so at the jurisdiction of the Nazis. The Warsaw Jewish Council was led by its chairman, Adam Czerniaków .

From the outset, rations for food were minimal and starvation was common. Rations were initially set at approximately 800 calories a day – less than half of the daily recommended allowance for women (2000 calories per day) and men (2500 calories per day). The rations consisted of bread, potatoes, and ersatz fat. In attempts to supplement their diets, ghetto inhabitants organised a thriving black market where goods could be exchanged for food.

Smuggling food into the ghetto became a common survival method. Children often wriggled through the sewers to enter the city outside of the ghetto and sneak food back in. Others paid off Nazi gate guards, and some even climbed the 10ft wall. Some of those outside the ghetto also used the inhabitants’ unfortunate circumstances to their advantage, importing food and medicine into the ghetto to the highest bidder.

Almost a year prior to the establishment of the ghetto, on 26 October 1939, forced labour was made compulsory for all Jewish men and boys aged 14 – 60. This was extended to men and boys aged 12-60 in January 1940. Some Jews managed to keep their jobs following ghettoisation in Warsaw, but most were made unemployed.

As the war effort continued, the need for cheap, and preferably free, labour increased. The Nazis increasingly turned to utilising the incarcerated Jews for forced labour such as construction work. By the summer of 1940, the Jewish Council in Warsaw was asked to supply lists of able-bodied Jewish men to work in labour camps. Failure to supply the amount of men asked for resulted in random round-ups of Jewish men in the streets. Conditions in the camps were abysmal , and workers sent there would often die as a result of the lethal conditions, or return back to the ghetto scarred by their experiences. Workers were not paid for their efforts.

With over 400,000 people crowded into an area of 1.3 square miles, hygiene immediately became an issue in the ghetto. Many homes did not have access to running water. Soap was sparse and of poor quality. In addition to this, there were just five public bath houses, serving approximately 17,000 people a month.

Janusz Korczak

Janusz Korczak was a well-known Polish Jewish teacher, doctor, and children’s author based in Warsaw. Korczak studied medicine at the University of Warsaw before serving in both the Russo-Japanese War and the First World War as a military doctor. Between 1911 and 1912 Korczak set up and led an orphanage in Warsaw for Jewish children.

In 1940, following the German invasion of Poland, the orphanage was moved into the area designated to be the Warsaw Ghetto. Despite the terrible conditions, Korczak worked tirelessly to ensure the children had adequate food and social activities.

Over the next few years, Korczak was repeatedly offered opportunities by underground resistance groups to escape the ghetto, but he refused to abandon the children in the orphanage. In the first week of August 1942, the Nazis came to the orphanage to collect the 200 children who were still housed there. Korczak insisted that he would accompany them. Korczak and the children were marched to the Umschlagplatz , the deportation point of the ghetto, and sent together to their deaths at the Treblinka extermination camp.

Korczak pictured with children from his orphanage.

Culture in the Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto had several bars where inhabitants could, if they had spare time and money, go to momentarily escape their circumstances. This picture was taken in a bar in 1940.

Whilst conditions in the ghetto were extremely difficult, some inhabitants were determined to continue cultural aspects of their previous life.

Despite education being banned at almost all levels, there were schools throughout the ghetto. Adults could also attend seminars and lectures , often led by those at the top of their field, such as Professor Hirszfeld , a prominent bacteriologist who led lectures for medical students. Until 1942, Jewish book stores also operated in the ghetto.

There were also several theatres which showed plays, as well as artists, musicians, bands and writers, who published covertly.

From 15 January 1941, inhabitants of the ghetto could also send and receive post through the Warsaw Post Office based in the ghetto. Post was unreliable and could be temporarily suspended. It was also censored and could only be sent to neutral countries not at war with Germany. Despite these challenges, the postal service meant that inhabitants could receive food packages from relatives in Poland or abroad, and spread the word about the poor conditions there, albeit using indirect language or drawings.

Resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto

Emanuel Ringelblum (1900-1944) was the founder of an underground archive compiled within the Warsaw Ghetto. This book was written by Ringelblum and documents life within the ghetto. In 1943, Ringelblum, his wife and their son went into hiding. A year later, they were denounced, captured and shot inside the Warsaw Pawiak prison.

A portrait of Emanuel Ringelblum. Date and place unknown.

Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain].

Jews in the ghetto resisted Nazi rule and the conditions imposed on them in different ways.

Perhaps the most common form of resistance took place in the form of smuggling basic supplies over, under or through the ghetto walls. Estimates suggest that between 80 – 97.5% of the total food intake of all inhabitants entered the ghetto this way. Without this form of resistance, thousands more people would have died from starvation.

Others Jews imprisoned in the ghetto resisted the Nazis by continuing to take part in religious activities and holidays, despite these often being banned. Participants were subject to extreme punishments if caught. An example of this religious resistance in the ghetto was the group prayers held in secret at the house of Rabbi Szapiro .

Similarly, some set up schools, despite the ban on education for Jews. Others created or attended other cultural activities, such as plays, exhibitions, cabaret performances, and cafés with live music.

The historian Emanuel Ringelblum , in collaboration with others such as Rachel Auerbach , resisted Nazi rule from within the ghetto by creating an archive documenting the Nazi crimes. Ringelblum’s collection became known as the Oyneg Shabes archive. Facing the threat of deportation to Treblinka extermination camp , Oyneg Shabes buried their extensive collection in milk cans and metal boxes to prevent the archive from falling into the hands of the Nazis. After the war, some of this record was dug up and rediscovered.

Some Jews also physically resisted the Nazi rule. The most largest and most significant case of armed resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto was the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943 .

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

This report was prepared by SS Commander General Jürgen Stroop detailing the events of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising for Himmler. Here, Stroop describes the difficulty initially faced by the SS and Gestapo, and some of the resistance and fighting methods used by the Jews.

This photograph was taken as part of the Stroop Report in May 1943. It shows Jews being forcibly removed from a bunker following the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Following their removal, it is likely that these Jews were deported to Treblinka extermination camp and murdered.

This photograph also features as part of the Stroop Report. Here, German troops are pictured sweeping through the Warsaw Ghetto in May 1943.

Following the armed resistance in January 1943, Himmler sent this order to tear down and destroy the Warsaw Ghetto.

Following the order from Himmler, and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the ghetto was destroyed and reduced to rubble.

On 22 July 1942, the Jewish Council of Warsaw published a Nazi notice to the ghetto, stating that almost all of its inhabitants would be deported to camps in the east, regardless of age or gender. Mass deportations began, and by 12 September 1942 approximately 300,000 of the ghetto’s inhabitants had been deported to the Treblinka extermination camp or murdered. Roughly 50,000 people remained in the ghetto.

When the deportations halted in September, the utter despair felt by many Jews throughout the mass deportations hardened into growing resistance. As the historian Emanuel Ringelblum , who was incarcerated in the ghetto, noted ‘it seems to me that people will no longer go to the slaughter like lambs. They want the enemy to pay dearly for their lives. They’ll fling themselves at them with knives, staves, coal gas…they’ll not allowed themselves to be seized in the street, for they know that work camp means death these days’ [ The Journal of Emanuel Ringelblum, Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto, Jacob Sloan (ed.) (McGraw-Hill Book Company, USA, 1958), p.326].

Inhabitants of the ghetto had heard rumours of the extermination camps operating in the east, and many guessed what fate awaited them. Determined not to be taken to their deaths, preparations were made to resist the Germans should any more deportations take place. These preparations were led by a variety of resistance groups, such as the Jewish Combat Organisation and Jewish Military Union .

At 6am on 18 January 1943, deportations from the ghetto were resumed. As the Germans began to gather Jews, the remaining inhabitants in the ghetto surprised the Nazis by defying orders, hiding, and putting up an armed resistance. Several Nazi soldiers were injured, and, by 21 January 1943, the deportations ceased. Between 5000 and 6500 Jews were taken to be deported to camps in the east.

Following this resistance, Jews built bunkers and hideouts for a defensive battle, assuming that the Nazis would soon retaliate. They continued to collect weapons and bullets through connections with the Polish underground, and prepared for an attack.

On 19 April 1943, the Nazis began their attack, led by SS General Jürgen Stroop. Within fifteen minutes, Jewish fighters retaliated , many with handmade weapons, initially forcing the German troops to retreat on the first day.

The Nazis changed tact, and slowly destroyed the ghetto, building by building, forcing Jews remaining in hiding to appear or be killed. 27 days after the initial April attack, on 16 May 1943, the uprising was crushed by the Nazis, and the ghetto destroyed. The 42,000 survivors of the uprising were deported to concentration camps and extermination camps in the east.

While the uprising ultimately failed, it was an extremely significant display of resistance from Jews in Warsaw. It delayed the Germans timeline of deportations, and inspired other resistance movements across the German-occupied areas.

The Stroop Report

SS General Jürgen Stroop (26 September 1895 – 6 March 1952) was the Nazi commander in charge of crushing the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

After the Uprising had been defeated, Stroop wrote an official account from the Nazis perspective. This became known as the Stroop Report. The report was 125 pages long and also contained several photographs of the Uprising. Three official copies of the report were produced, one for Heinrich Himmler , one for Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger , and one for Stroop himself.

The photographs within the report show several scenes from the Uprising, from the violent ways in which Jews were removed from their hiding places, to how buildings in the ghetto were set on fire and destroyed.

These photographs have since become widely recognisable images of Nazi atrocities.

Despite this, most of the Jews depicted in the photographs remain unknown. The Nazi photographer(s) who took the photographs also remain uncertain. The Nazi officers depicted in the photographs are also mainly unidentified (with the exception of Josef Blösche).

Continue to next topic

Case Study: Theresienstadt Ghetto

What happened in may.

On 10 May 1933, university students supported by the Nazi Party instigated book burnings of blacklisted authors across Germany.

On 1 May 1935, the German government issued a ban on all organisations of the Jehovah's Witnesses. Image courtesy of USHMM.

On 10 May 1940, German forces invaded the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and Luxembourg.

On 29 May 1942, the German authorities in France passed a law requiring Jews to wear the Star of David.

On 16 May 1944, inmates of the Gypsy camp in Auschwitz resisted the SS guards attempting to liquidate the camp.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

HISTORY Gr. 11 Unit 7 Case Study - Nazi Germany Part 3

- The concept of genocide

- Stages 1-7 of Stanton’s 10 Stages of Genocide

- The preparation for the genocide of the Jews of Europe (the Holocaust)

Continuing with case study Nazi Germany this unit deals with the concept of genocide. We look at stages 1-7 of Stanton’s Ten Stages of Genocide and the prelude to the genocide of the Jews of Europe (the Holocaust).

Do you have an educational app, video, ebook, course or eResource?

Contribute to the Western Cape Education Department's ePortal to make a difference.

Home Contact us Terms of Use Privacy Policy Western Cape Government © 2024. All rights reserved.

Genocide Studies Program

Between the ascension of the Nazi regime to power in Germany in 1933 and the defeat of the German army in 1945, over six million civilians perished at the hands of German forces, their military allies, and their civilian associates. The word “Holocaust,” with Greek roots meaning “destruction of life by fire” and a common translation of the Hebrew word “Shoah,” is nearly universally understood to refer to these events.

The murderous effort rested on an ideology of racial superiority and aspirations of racial “purity.” Jews were by far the largest component of the victims. Roma and Sinti (both commonly – but sometimes derogatorily – referred to as “Gypsies”) were also targeted, as were the physically disabled, the mentally disabled, and members of several religious minorities. Political opponents, as well as Slavic and Russian civilians, were also murdered in large quantities, although whether these mass atrocities constituted part of a genocide is less certain.

The Holocaust unfolded over time. When the Nazi regime came to power, it was already imbued with an ideology of racial ideology – which happened to comport with its own sense of it political enemies. It began establishing concentration camps shortly after coming to power. The regime also systematically discriminated against Jews (and other groups it perceived to be racially inferior) in the economic, political, and civic realms. November 1938 pogroms known as “Kristallnacht” demonstrated that the German police would tolerate (and, indeed, encourage) violence against Jews and their property. Once World War II broke out the following year, the German government expanded its concentration camp system, and soon converted them into an infrastructure for mass killing. Meanwhile, an even greater number of Jews and other civilians would be killed outside of the camps, either through the Nazi SS Einsatzgroppen (mobile paramilitary units) or the actions of Nazi supporters on either side of the front lines in Eastern Europe.

The Holocaust is undoubtedly the seminal event for the field of genocide studies. Even as scholars examine new and different cases from a variety of perspectives, the foundation of the field lies in effort to understand the organization, behavior, and psychology of different actors – those who killed, those who stood by, those who perished, those who attempted to help, and those who survived – the Holocaust. Many of the field’s most important scholars continue to address these issues today.

A central component of the Genocide Studies Program has been Dr. Dori Laub’s study of trauma among Holocaust victims, which makes extensive use of Yale University’s Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies.

Videotestimony Pilot Study of Psychiatrically Hospitalized Holocaust Survivors

Principal Investigator: Dori Laub , MD, Deputy Director (Trauma Studies), Genocide Studies Program. For more details please visit the Traumatic Psychosis: A Videotestimony Research Project website.

The purpose of this research is to systematically assess the effects and potential psychotherapeutic benefits of reconstructing traumatic Holocaust experiences. The reconstruction of the history of personal trauma were conducted through the creation of a videotaped testimony and a multi-disciplinary analysis of the testimony. This study addressed two hypotheses:

- Is massive psychic trauma related to chronic severe mental illness with psychotic decompensation that leads to either chronic hospitalization or multiple psychiatric hospitalizations?

- Does a therapeutic intervention such as video testimony that helps build a narrative for the traumatic experience and gives it a coherent expression help in alleviating its symptoms and changing its course? May these changes be attributed to direct intervention (through the occurrence of the testimonial event itself), or through indirect intervention (through the impact on treatment planning, involvement with family members or the survivor community, or the knowledge that the videotaped testimony will be made available to others)?

A 1993 examination of approximately 5,000 long-term psychiatric inpatients in Israel identified about 900 Holocaust survivors. These patients were not treated as unique: trauma-related illnesses were neglected in diagnosis and decades-long treatment. Evaluation by the Israeli Ministry of Health concluded some 300 of them no longer required inpatient psychiatric hospitalization; specialized hostels (similar to nursing homes) were established on the premises of three psychiatric hospitals. We hypothesize that many of these patients could have avoided lengthy if not life-long psychiatric hospitalizations, had they been able or enabled by their treaters and by society at large to more openly share their severe persecution history. Instead, their traumatic experiences remain encapsulated, causing the survivor to lead a double life: a robot-like semblance to normality with incessant haunting by nightmares and flashbacks. Attention to the particular features of these patients traumatic experiences is of particular importance in the rehabilitation and the re-evaluation of these patients whose initial hospitalization and diagnoses long predate more recent theoretical developments and clinical formulations (e.g., differential diagnosis of PTSD, testimony as therapy).

Phase II of the videotestimony study which is now underway, consists of an in-depth analysis of the videotexts by an interdisciplinary team of experts, in order to define the unique features of the traumatic psychotic disorder these patients most likely suffer from.

The Slave Labor Video Testimony Project

The Foundation for “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future” has organized an international project to collect 550 video and audio testimonies from former forced and slave laborers in the German “Third Reich.” Ex-laborers from 25 different countries, mostly in Eastern Europe, are being interviewed. The project requested the GSP’s Trauma Project to conduct 20 videotestimonies with Jewish Holocaust Survivors in the United States. The names of these survivors were obtained through the Fortunoff Video Archive and through the Connecticut Child Survivor Organization. After proper preparation, the videotestimonies were filmed on the European PAL format and on the American NTSC format, in parallel with professional audiotaping. The testimonies were all given in English and lasted between two and four hours. All subjects also filled out a symptom checklist PCL-9 for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, which will be repeated within a year of their testimony to see whether the testimonial event has brought about possible symptom changes and symptomotology.

The twenty videotestimonies, taken in Dr. Laub’s office in New Haven, Connecticut, have all been completed and transcribed and translated into German. The PAL videocassettes were sent to an audio visual lab in Israel to be transferred to an enhanced BETA format. After that enhancement, they were shipped to Hagen University in Ludenscheid, Germany, which coordinates this international study, along with their translated transcripts and the consent forms, as well as summaries. They were also sent to the Foundation for “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future.” This project has created a substantial database, useful for future historical, psychological and linguistic studies, for which definite funding is needed.

Dori Laub, Presentations 2005-2011

Live revision! Join us for our free exam revision livestreams Watch now →

Reference Library

Collections

- See what's new

- All Resources

- Student Resources

- Assessment Resources

- Teaching Resources

- CPD Courses

- Livestreams

Study notes, videos, interactive activities and more!

History news, insights and enrichment

Currated collections of free resources

Browse resources by topic

- All History Resources

Resource Selections

Currated lists of resources

Edexcel GCSE: Weimar and Nazi Germany 1918-1939

Last updated 3 Jan 2020

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

Here are a comprehensive collection of short study notes and interactive revision resources for the Weimar and Nazi Germany 1918-1939 (Option 31) unit of the Edexcel GCSE History course.

RECOMMENDED REVISION GUIDE FOR EDEXCEL GCSE HISTORY: WEIMAR & NAZI GERMANY (1918-39)

We recommend that students taking Edexcel GCSE History: Weimar and Nazi Germany 1918-1939 use the following revision guide which also includes practice exam questions.

Revision Guide for Edexcel GCSE History: Weimar & Nazi Germany (1918-39)

Study Notes for Key Topic 1: The Weimar Republic 1918-1929

Origins of the weimar republic - the first world war.

Study Notes

Origins of the Weimar Republic - Kaiser Wilhelm II

Creating the weimar republic, the national assembly of the weimar republic, the weimar constitution, strengths of the weimar constitution, weaknesses of the weimar constitution, political parties of the weimar republic, the treaty of versailles (1919), challenges to the weimar republic from the left, challenges to the weimar republc from the right, the spartacist revolt (1919), the freikorps, the kapp putsch (1920), french occupation of the ruhr (1923), political violence in germany between 1919-1923, hyperinflation in germany in 1923, effects of hyperinflation in germany in 1923, the rentenmark & gustav stresemann, the dawes plan (1924), the young plan (1929), the locarno pact (1925), the league of nations, the kellogg-briand pact (1928), stresemann and domestic politics in germany, living standards in the weimar republic (1924-29), women in the weimar republic (1924-29), culture and architecture in the weimar republic (1924-29), study notes for key topic 2: hitler’s rise to power 1919-1933, hitler's early life, creating the nazi party, hitler & drexler's 25 point programme, leading nazis during hitler's rise to power, the sa (sturmabteilung), hitler takes total control of the nazi party (1922), the munich putsch (1923), causes of the munich putsch, consequences of the munich putsch, hitler & the nazi party - the lean ("wilderness") years from 1924-1928, reorganising the nazi party, bamberg conference (1926), wall street crash and germany (1929), effect of the crash in germany, bruning's failure to cope with unemployment, increasing support for extreme parties in germany in the early 1930's, reasons for the increase in support for the nazis, german presidential election (1932), bruning's resignation, von papen's chancellorship, schleicher's chancellorship, hitler's steps to the chancellorship, study notes for key topic 3: nazi control and dictatorship 1933-1939, opposition to the nazis, the reichstag fire, the enabling act, the nazi police state, the ss (schutzstaffel), the sd (sicherheitsdienst), the gestapo, concentration camps, the nazis and the legal system, nazis & the catholic church, the national reich church, nazi propaganda, the nazis and the media, party rallies, the berlin olympics, opposition from the young, removing opposition, night of the long knives, the death of president hindenburg, martin niemoller, religious opposition, swing youth, edelweiss pirates, study notes for key topic 4: life in nazi germany 1933-1939, culture in nazi germany, architecture in nazi germany, music and film in nazi germany, literature in nazi germany, kristallnacht, nuremberg laws, persecution of the jews, treatment of the disabled, the treatment of homosexuals, treatment of gypsies and roma, treatment of slavs, anti-semitism, the beauty of labour, strength through joy, the german labour front, hiding the level of unemployment, national labour service, reducing unemployment, conformity in nazi germany, the german women's enterprise, the nazis and views on women, young people and the nazis, the nazis, women and employment, the nazis, women and the family, education in nazi germany, league of german maidens, the hitler youth, revision activities for germany 1918-1939, gcse: nazi germany - 'loose change' revision activity.

Quizzes & Activities

Germany 1918-1939 - 'Clear the Deck' Revision Activity

Gcse: germany (1918-39) - growth in support for the nazis 1929-1932 (revision quiz), gcse: germany (1918-39) - the munich putsch and the lean years 1923-29 (revision quiz), gcse: germany (1918-39) - early development of the nazi party 1920-22 (revision quiz), gcse: germany (1918-39) - recovery of the weimar republic (revision quiz), gcse: germany (1918-39) - changes in society 1918-29 (revision quiz), gcse: germany (1918-39) - origins of the weimar republic (revision quiz), gcse: germany (1918-39) - early challenges to the weimar republic 1919-23 (revision quiz), gcse: key events in weimar and nazi germany (1918-39) - "keepy-uppy" revision activity, our subjects.

- › Criminology

- › Economics

- › Geography

- › Health & Social Care

- › Psychology

- › Sociology

- › Teaching & learning resources

- › Student revision workshops

- › Online student courses

- › CPD for teachers

- › Livestreams

- › Teaching jobs

Boston House, 214 High Street, Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, LS23 6AD Tel: 01937 848885

- › Contact us

- › Terms of use

- › Privacy & cookies

© 2002-2024 Tutor2u Limited. Company Reg no: 04489574. VAT reg no 816865400.

CBSE Class 9 History Notes Chapter 3 - Nazism and the Rise of Hitler

Nazism and the Rise of Hitler Chapter 3 of CBSE Class 9 History discusses the rise of Hitler and the politics of Nazism, the children and women in Nazi Germany, schools and concentration camps. It further highlights the facts related to Nazism and how they denied various minorities a right to live, anti-Jewish feelings, and a battle against democracy and socialism. History notes of CBSE Class 9 Chapter 3 are easily understandable and cover most of the concepts engagingly. With the help of these CBSE Class 9 History notes , students can master all the topics given in the chapter. These notes are prepared by subject experts and are well-structured. Students can quickly grasp important concepts and also retain them for a more extended period.

- Chapter 1 The French Revolution

- Chapter 2 Socialism In Europe and The Russian Revolution

- Chapter 4 Forest Society and Colonialism

- Chapter 5 Pastoralists In The Modern World

CBSE Class 9 History Notes Chapter 3 – Nazism and the Rise of Hitler

Birth of the weimar republic.

In the early years of the twentieth century, Germany fought the First World War (1914-1918) alongside the Austrian Empire and against the Allies (England, France and Russia.). All resources of Europe were drained out because of the war. Germany occupied France and Belgium. But, unfortunately, the Allies, strengthened by the US entry in 1917, won, defeating Germany and the Central Powers in November 1918. At Weimar, the National Assembly met and established a democratic constitution with a federal structure. In the German Parliament, deputies were elected on the basis of equal and universal votes cast by all adults, including women. Germany lost its overseas colonies. The War Guilt Clause held Germany responsible for the war and the damages the Allied countries suffered. The Allied armies occupied Rhineland in the 1920s.

The Effects of the War

The entire continent was devastated by the war, both psychologically and financially. The war of guilt and national humiliation was carried by the Republic, which was financially crippled by being forced to pay compensation. Socialists, Catholics and Democrats supported the Weimar Republic, and they were mockingly called the ‘November criminals’. The First World War left a deep imprint on European society and polity. Soldiers are placed above civilians, but unfortunately, soldiers live a miserable life. Democracy was a young and fragile idea which could not survive the instabilities of interwar Europe.

Political Radicalism and Economic Crises

The Weimar Republic’s birth coincided with the revolutionary uprising of the Spartacist League on the pattern of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. They crushed the uprising with the help of a war veterans organisation called Free Corps. Communists and Socialists became enemies. Political radicalisation was heightened by the economic crisis of 1923. Germany refused to pay, and the French occupied its leading industrial area, Ruhr, to claim their coal. The image of Germans carrying cartloads of currency notes to buy a loaf of bread was widely publicised, evoking worldwide sympathy. This crisis came to be known as hyperinflation, a situation when prices rise phenomenally high.

The Years of Depression

The years between 1924 and 1928 saw some stability. The support of short-term loans was withdrawn when the Wall Street Exchange crashed in 1929. The Great Economic Depression started, and over the next three years, between 1929 and 1932, the national income of the USA fell by half. The economy of Germany was the worst hit. Workers became jobless and went on streets with placards saying, ‘Willing to do any work’. Youths indulged themselves in criminal activities. The middle class and small businessmen were filled with the fear of proletarianisation, anxiety of being reduced to the ranks of the working class or unemployment. Politically also, the Weimar Republic was fragile. The Weimar Constitution, due to some inherent defects, made it unstable and vulnerable to dictatorship. One inherent defect was proportional representation. Another defect was Article 48, which gave the President the powers to impose emergency, suspend civil rights and rule by decree.

Hitler’s Rise to Power

Hilter rose to power. He was born in 1889 in Austria and spent his youth in poverty. In the First World War, he enrolled on the army, acted as a messenger in the front, became a corporal, and earned medals for bravery. Hitler joined a small group called the German Workers’ Party in 1919. He took over the organisation and renamed it the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, which later came to be known as the Nazi Party. In 1923, he planned to seize control of Bavaria, march to Berlin and capture power. During the Great Depression, Nazism became a mass movement. After 1929, banks collapsed, businesses shut down, workers lost their jobs, and the middle classes were threatened with destitution. In such a situation, Nazi propaganda stirred hopes of a better future.

Hitler was a powerful speaker, and his words moved people. In his speech, he promised to build a strong nation, undo the injustice of the Versailles Treaty and restore the dignity of the German people. He also promised employment for those looking for work and a secure future for the youth. He promised to remove all foreign influences and resist all foreign ‘conspiracies’ against Germany. Hitler started following a new style of politics, and his followers held big rallies and public meetings to demonstrate support. According to the Nazi propaganda, Hitler was called a messiah, a saviour, and someone who had arrived to deliver people from their distress.

The Destruction of Democracy

President Hindenburg offered the Chancellorship, on 30 January 1933, the highest position in the cabinet of ministers, to Hitler. The Fire Decree of 28 February 1933 suspended civic rights like freedom of speech, press and assembly that had been guaranteed by the Weimar Constitution. On 3 March 1933, the famous Enabling Act was passed, which established a dictatorship in Germany. The state took control over the economy, media, army and judiciary. Apart from the already existing regular police in a green uniform and the SA or the Storm Troopers, these included the Gestapo (secret state police), the SS (the protection squads), criminal police and the Security Service (SD).

Reconstruction

Economic recovery was assigned to the economist Hjalmar Schacht by Hitler, who aimed at full production and full employment through a state-funded work-creation programme. This project produced the famous German superhighways and the people’s car, the Volkswagen. Hitler ruled out the League of Nations in 1933, reoccupied the Rhineland in 1936, and integrated Austria and Germany in 1938 under the slogan, One people, One empire and One leader. Schacht advised Hitler against investing hugely in rearmament as the state still ran on deficit financing.

The Nazi Worldview

Nazis are linked to a system of belief and a set of practices. According to their ideology, there was no equality between people but only a racial hierarchy. The racism of Hitler was borrowed from thinkers like Charles Darwin and Herbert Spencer. The argument of the Nazis was simple: the strongest race would survive, and the weak ones would perish. The Aryan race was the finest who retained its purity, became stronger and dominated the world. The other aspect of Hitler’s ideology related to the geopolitical concept of Lebensraum, or living space. Hitler intended to extend German boundaries by moving eastwards to concentrate all Germans geographically in one place.

Establishment of the Racial State

Nazis came into power and quickly began to implement their dream of creating an exclusive racial community of pure Germans. They wanted a society of ‘pure and healthy Nordic Aryans’. Under the Euthanasia Programme, Helmuth’s father had condemned to death many Germans who were considered mentally or physically unfit. Germany occupied Poland and parts of Russia captured civilians and forced them to work as slave labour. Jews remained the worst sufferers in Nazi Germany. Hitler hated Jews based on pseudoscientific theories of race. From 1933 to 1938, the Nazis terrorised, pauperised and segregated the Jews, compelling them to leave the country.

The Racial Utopia

Genocide and war became two sides of the same coin. Poland was divided, and much of north-western Poland was annexed to Germany.

People of Poland were forced to leave their homes and properties. Members of the Polish intelligentsia were murdered in large numbers, and Polish children who looked like Aryans were forcibly snatched from their mothers and examined by ‘race experts’.

Youth in Nazi Germany

Hitler was interested in the youth of the country. Schools were cleansed and purified. Germans and Jews were not allowed to sit or play together. In the 1940s, Jews were taken to the gas chambers. Introduction of racial science to justify Nazi ideas of race. Children were taught to be loyal and submissive, hate Jews and worship Hitler. Youth organisations were responsible for educating German youth in ‘the spirit of National Socialism’. At the age of 14, boys had to join the Nazi youth organisation where they were taught to worship war, glorify aggression and violence, condemn democracy, and hate Jews, communists, Gypsies and all those categorised as ‘undesirable’. Later, they joined the Labour Service at the age of 18 and served in the armed forces and entered one of the Nazi organisations. In 1922, the Youth League of the Nazis was founded.

The Nazi Cult of Motherhood

In Nazi Germany, children were told women were different from men. Boys were taught to be aggressive, masculine and steel-hearted and girls were told to become good mothers and rear pure-blooded Aryan children. Girls had to maintain the purity of the race, distance themselves from Jews, look after their homes and teach their children Nazi values. But all mothers were not treated equally. Honours Crosses were awarded to those who encouraged women to produce more children. Bronze cross for four children, silver for six and gold for eight or more. Women who maintained contact with Jews, Poles and Russians were paraded through the town with shaved heads, blackened faces and placards hanging around their necks announcing, ‘I have sullied the honour of the nation’.

The Art of Propaganda

Nazis termed mass killings as special treatment, the final solution (for the Jews), euthanasia (for the disabled), selection and disinfection. ‘Evacuation’ meant deporting people to gas chambers. Gas chambers were labelled as ‘‘disinfection areas’, and looked like bathrooms equipped with fake showerheads. Nazi ideas were spread through visual images, films, radio, posters, catchy slogans and leaflets. Orthodox Jews were stereotyped and marked and were referred to as vermin, rats and pests. The Nazis made equal efforts to appeal to all the different sections of the population. They sought to win their support by suggesting that Nazis alone could solve all their problems.

Ordinary People and the Crimes Against Humanity

People started seeing the world through Nazi eyes and spoke their Nazi language. They felt hatred and anger against Jews and genuinely believed Nazism would bring prosperity and improve general well-being. Pastor Niemoeller protested an uncanny silence amongst ordinary Germans against brutal and organised crimes committed in the Nazi empire. Charlotte Beradt’s book called ‘The Third Reich of Dreams’ describes how Jews themselves began believing in the Nazi stereotypes about them.

Knowledge about the Holocaust

The war ended and Germany was defeated. While Germans were preoccupied with their own plight, the Jews wanted the world to remember the atrocities and sufferings they had endured during the Nazi killing operations – also called the Holocaust. When they lost the war, the Nazi leadership distributed petrol to its functionaries to destroy all incriminating evidence available in offices.

Students can go through Geography, History, Political Science and Economics notes by visiting the CBSE Class 9 Social Science page at BYJU’S. Keep learning and stay tuned for further updates on CBSE and other competitive exams.

Frequently Asked Questions on CBSE Class 9 History Notes Chapter 3 Nazism and the Rise of Hitler

What are the main features of nazism.

Nazism is a form of fascism which incorporates fervent antisemitism, anti-communism, scientific racism, and the use of eugenics into its creed.

Who was Hitler?

Hitler was the leader of the Nazi Party (from 1920/21) and chancellor (Kanzler) and Führer of Germany (1933–45).

What is a racial group?

Racial groups are populations of people based on their genealogy, skin colour and physical traits.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

- Nazi Germany (1933-1945)

Second edition by S. Jonathan Wiesen, Pamela Swett First edition by Richard Breitman

Introduction

- S. Jonathan Wiesen

- Pamela Swett

This volume on Nazi Germany offers a variety of primary sources to students, educators, and other researchers. In working with a time period that has been documented extensively, we editors were able to put together a wealth of materials that lend themselves to classroom use, independent or guided primary-source research, and general interest reading. The selected themes—from foreign policy to consumer culture to racial policy—provide access to a diversity of experiences and developments that are too often reduced to a singular focus on Hitler and his genocidal policies. Teachers, students, and other users will discover images, documents, videos, and audio clips that will spark debates about power structures in the Third Reich, Nazi Germany’s relationship with other countries, and the experiences and behaviors of Germans from all walks of life—women and men, industrial workers, farmers, middle-class consumers, the architects of racial legislation, and those (such as Jews, leftists, sexual and gender minorities, Roma, disabled people, and “asocials”) whom the regime labeled as unwelcome and as a threat to the so-called “people’s community” [ Volksgemeinschaft ]. The selected sources, together with the accompanying abstracts, will hopefully inspire users to explore other historical materials, on the web or in the library.

1. Studying Nazi Germany

There is a tremendous body of scholarship on National Socialism, and our editorial goal was to reproduce materials—some well-known, some new—that provide a basic overview of this twelve-year period, while also pointing to novel and provocative avenues of thinking. With those aims in mind, we editors had to contend with the overwhelming scholarly and public interest in National Socialism, which made choosing a limited number of sources difficult. The Nazi era is one of the most documented in history: a quick search for “Hitler” in the German National Library [ Deutsche Nationalbibliothek ] catalogue produces over 16,000 results; in the Library of Congress catalogue, the terms “Nazi” and “National Socialism” yield around 9,000 titles each. Even accounting for some overlap, this is an astronomical number of published sources. In addition, public and scholarly interest in this period, which peaked initially during World War II and in the immediate postwar period, only to wane somewhat in the 1950s and 1960s, has increased again over the last few decades. A great source for gauging such trends is the Google Ngram Viewer ( https://books.google.com/ngrams ), which allows users to track the appearance of certain of keywords in books over long stretches of time. What we learn is that since the late 1970s, there has been a remarkably steady increase in books with “Nazi” in the title and, since the 1990s, publications specifically with “Hitler” in the title.

What is a scholar or student to do with this near obsession with the Third Reich, manifested in, for example, the widespread tongue-in-cheek reference to the History Channel as the “Hitler Channel” and the coining of the term “Godwin’s Law”? The latter “rule” indicates that the longer an internet discussion thread continues (and one can extend this to other forums and public debates), the more likely it is that someone will bring up Hitler—as a way of attacking another person or shutting down conversation, or as an attempt to derive historical parallels that would presumably guide individuals and policymakers away from unwise decisions.

Adding to this challenge is a part scholarly, part public debate about whether the years of National Socialism occupy an outsized place in German history and in modern history more broadly. [1] After all, this volume covers the shortest period of time in the German History and Documents and Images (GHDI) website. The twelve years of the Third Reich can be contrasted to some earlier chronological volumes that encompass around 150 years each. The Weimar Germany volume is rather short as well—fourteen years—and while this period after World War I has received plenty of attention from scholars, it is nowhere near as well researched as the Nazi era. Questioning the omnipresence of Nazi history can be an important exercise for scholars who are trying to encourage students to balance research agendas, discover continuities in history, and think in a long-term manner that doesn’t privilege recent history or the history of atrocities. But it can also serve as a controversial political rallying point: take, for instance, the 2017 German parliamentary election season, when far right candidates pointed to what they saw as an almost masochistic obsession with the twelve years of Nazism, implicitly and explicitly calling on Germans to pull back on teaching and memorializing the Third Reich and its victims.

Students and teachers should be aware of these discussions, for they prompt important questions regarding the sources in this website. What kinds of issues do Adolf Hitler, the Nazi police state, and the lives of people in Nazi Germany pose to students, scholars, and the public today? What do these documents reveal about political decisions, individual choices, and historical causality during a period that still serves as the paradigm of state terror and genocide? What is unique about Nazi Germany, and which features of the Third Reich reflect longer, global trends? In light of these questions, we editors have tried to place the events of 1933–1945 in a broader context whenever possible—providing references to prior periods in German history and presenting a critical appraisal of the significance of the Nazi years in our source abstracts. We obviously take the position that the Nazi period deserves concentrated attention—that it provokes timely questions about ideology, conformity, free will, and modernity—which are essential to the study of history and critical for trying to understand today’s world.

2. How to Use these Sources

When it was announced that the GHI Washington was updating the GHDI website, we editors encountered enthusiastic reactions. Some students and colleagues were happy to see the site expanded with additional sources that reflect contemporary discussions about National Socialism. Others were excited about enhanced opportunities for students to engage in digital humanities research. On the latter note, we understand that while some will come to this site with a high level of digital literacy, others will have had less experience navigating online primary-source collections. We therefore encourage users to approach the sources in flexible ways, whether by clicking around and working with a few documents and images, or by reviewing the whole site. Some students will use the sources to map ideas and keywords through flowcharts and timelines; others will simply learn to approach primary sources more critically. This is not a digital archive, and students will likely consult not only this collection but also a number of other websites for primary sources, such as newspaper archives and other collections related to Nazi propaganda or the Holocaust. With this in mind, we tried to offer a representative sample of sources from the Nazi period. Of course, this strategy has its own problems. For example: what counts as “representative”? The experience of a Jew who has just lost his or her livelihood differs from that of an “Aryan” German enjoying improved access to consumer goods in the late 1930s. And each Jewish or non-Jewish German in this period had different encounters with the regime, different levels of optimism and pessimism about the course of politics, and different financial resources at his or her disposal.

We have tried to present multiple perspectives, but there will always be gaps, especially as students and teachers look for sources that address specific topics. Those interested in military strategy during World War II, for example, will find that the collection devotes less attention to battlefield tactics than to the experiences of those soldiers on the Eastern front, or in Africa, who confronted the brutality of warfare or engaged in ethnic cleansing. We encourage users to take a textual, visual, audio, or video source that they find interesting and pull on its thread both within the volume and beyond the GHDI collection. For example, when one encounters declarations of confidence in early February 1933 that Hitler’s tenure as chancellor would be short-lived—much like his predecessors’—the reader might then go to the Chicago Tribune or the London Times to read what journalists abroad were predicting in early 1933. Did the same flawed assumptions about Hitler being “boxed in” by more mainstream politicians exist beyond Germany’s borders? Students, we have found, are often captivated by headlines announcing events as they played out, be it a newspaper editorial about the 1936 Berlin Olympics or a New York Times article from November 10, 1938, the day after Kristallnacht , reporting that “violent anti-Jewish demonstrations broke out all over Berlin early this morning.” [2]

Thus, we hope that these sources will not only provide “data” for students but also cultivate an excitement about doing original research and feeling history as it was lived. We encourage students to discuss biases in a source, to consider how we editors may have privileged certain types of documents and images over others (e.g. is there too much about the importance of propaganda in the Third Reich? Too little on the experience of non-Germans under occupation?), and to ask whether a certain source supports or challenges common assumptions about a topic. We also invite users to consider how best to use the various types of sources. How do we get beyond seeing the images as mere illustrations and read them critically as historical sources? [3] How does listening to the era’s popular music help us better understand life in Nazi Germany? [4] People often come to a site like this thinking they know a lot about National Socialism. Perhaps we can push against some long-held assumptions or introduce new themes.

Let us offer one more word about the structure of the site and one caveat. First, the editors have added to rather than replaced the excellent documents from the first edition of GHDI’s Nazi Germany volume; thus, the reader might find an abundance of documents or images on a particular topic that reflects the earlier and/or current editors’ particular interests, like the 1944 bomb plot against Hitler or propaganda and consumer politics. In other words, some themes simply get more attention than others, as is the case with any source collection. Second, teachers, students, and general readers must be acutely aware of the presence of neo-Nazi websites as they move from GHDI to other online sources. Search engines are much better than they used to be in devising algorithms that push white supremacy websites lower down the results list when one types in “Nazi Germany.” And, to be sure, students might want to access these sites for their own research into neo-Nazism. But the wide exploitation of Nazi history for tendentious and sometimes hateful reasons demands that everyone approach Nazi-themed sites with extra scrutiny and with an awareness that not all information on the internet is equally reliable.

3. Key Themes

Rather than offering a chronological summary of the Third Reich or a preview of the individual sources, which are already accompanied by abstracts, our goal in this portion of the introduction is to highlight a few themes that run through this volume and to point users toward productive avenues of thinking. When the first edition of GHDI was launched, this volume offered a number of “top-down” perspectives. That is to say, the collection tended to emphasize the importance of Hitler and his policymakers, the apparatus of terror they created, declarations from the regime, and Nazi foreign policy in the run up to and during the Second World War. In studying a dictatorship, these perspectives are fundamental, and we have maintained them. However, the original site also contained fewer—albeit excellent—diary entries and other reflections by people who experienced the Third Reich “from below,” and we have tried to amplify this “bottom up” approach in this edition. Some historians have struggled with how to fit the everyday life of Germans into their discussions of a regime based on intimidation. How does one balance glimpses into the prosaic existence of most Germans—working, shopping, vacationing, and spending time with family—with the realities that Nazi Germany was an extraordinarily invasive regime that regulated considerable aspects of public and private life? [5] Indeed, in planning this new edition of GHDI, we editors initially considered adding a separate chapter called “Everyday Life.” But we quickly encountered the problem that any such isolated chapter would be arbitrary. For each chapter—on racial policy, police control, resistance and rescue, or the Holocaust —needed to highlight the lived experiences of Germans and other Europeans under a dictatorship. Therefore, within each chapter we expanded the number of sources by and about “ordinary” Germans. We suggest, however, that students and teachers talk about these challenges. Does “everyday life” mean “normal life”? What counted as “normal” during these years—or in any political setting—and is it possible to make generalizations when so many Germans were shut out of society, politics, the military, and the economy for ideological reasons during the 1930s and 1940s? Does a focus on everyday life shift too much attention away from the top-down apparatus of persecution? How did people live with what one historian has referred to as a “split consciousness,” which allowed Germans to support or tolerate a brutal regime and to proceed with their daily (often joyful) rituals, as if the regime’s crimes did not exist? [6]

Another theme running through the selected sources is racism, and it too reflects a larger debate in the field of German history. To what extent was Nazi Germany a “racial state,” to invoke the title of an important book in the field? [7] In other words, how much did Hitler and top Nazi leaders’ obsession with Jews and other racial and biological “inferiors” guide their policies and define life in the Third Reich? To what extent did other considerations and realities—such as the raw desire for power, the focus on economic recovery, and the manifestation of different forms of non-racialized prejudice (such as portraying Jews as economic exploiters as much as racial inferiors)—define the Nazi years? One may also ask how unique Nazi Germany was in isolating and persecuting minorities. While recognizing the unprecedented industrialized murder of Jews and other populations, historians also see modes of thinking and forms of segregation that were found in other racist regimes, like the American South and South Africa. In other words, we may ask whether the Nazis built a “racial state” par excellence—with political and social life revolving around antisemitism and the biological health of the Volk —or whether Nazi Germany was more complex in its goals and more similar to other regimes than we would like to acknowledge?

Another theme raised by the featured sources is one that, again, scholars are asking themselves: How modern was the Third Reich? For many years, historians and the general public tended to view the Nazi movement as fundamentally backward looking—calling for a return to a glorious Germanic past, pushing women into their traditionally confined domestic sphere, and retreating into a world defined by “blood and soil.” There is no question that this depiction captures some of the realities of Nazi ideology and life in the Third Reich. We can point to countless retrograde gender policies and numerous jeremiads against the corrupting influence of modern art, Hollywood, and other forms of “Jewish modernity”; we have included several sources on these themes. Indeed, Hitler aimed to erase from Germany the corrupting influence of “degenerate” and overtly “modern” forms of cultural and social expression and return the nation to a putatively pre-modern period of völkisch purity. And yet, we now have a more complicated picture, one of a leader and a regime that embraced modern forms of propaganda and media and of a populace that enjoyed the fruits of modern consumer culture, such as cinema, radio, music, and motorized travel. One historian has characterized National Socialist ideology as “reactionary modernism,” reflecting the movement’s regressive ideological goals and the modern means it employed to attain them. [8] Others emphasize that “the Nazis” cannot be reduced to a monolithic group with a single view of modernity or any social or cultural issue. Our sources on film, leisure, advertising, and mechanized war and genocide should prompt students to think through this question of how modern Germany was in the 1930s and early 1940s. Why might this question matter? Does the “modernity” of the Third Reich mean that life during the Nazi years shared familiar features that we would easily recognize in other countries at the time and even today? If the Nazis were “moderns,” then what does that say about the role of science, medicine, and the media in paving the way for the Nazi dictatorship and its crimes?

The final theme emerging from the selected sources might be referred to as the “coercion and consent” debate. Many students come to the study of Nazi Germany with the assumption that the average German who was not branded as an outsider was brainwashed into supporting the schemes of ideologues like Hitler, Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, and SS leader Heinrich Himmler. There is also the attendant view that, under the Nazi dictatorship, Germans lost their ability to resist, speak out against the regime’s policies, or exercise free will. If they weren’t the passive victims of a propaganda blitz, as this theory goes, then Germans were at the very least coerced into supporting Hitler’s brutal aims. It is not surprising that many students, scholars, and the general public have subscribed to some version of this “coercion” thesis. This approach, drawn from older theories of totalitarianism, is common in cable television documentaries, which often highlight Hitler’s worldview and the oppressive aspects of the Nazi state. But people also adhere to this view because there is good evidence for certain aspects of it. The Nazi regime was a violent police state that presided over a network of what grew to be hundreds of concentration and death camps. It threatened to punish critics of the regime with prison time or death, and it militarized large aspects of society. Finally, it indoctrinated Germany’s youth in racialized thinking and encouraged neighbors to denounce each other to the authorities. [9]

And yet scholarship has revealed that there is more to the story. From the early days of the Third Reich until well into the war, there was widespread support for the regime, and this support was not simply the product of coercion. The featured sources prompt one to question where coercion ends and consent begins. As fawning letters to Hitler testify, the Führer was highly popular for much of the Third Reich, with Germans buying into the “Hitler myth” that their leader was almost god-like in his ability to right the wrongs of the past and usher in a new era of greatness for their country. [10] Likewise, it took the work of millions of German citizens to put Nazi visions of a racially pure society into place. Of course, not everyone bore the same level of responsibility, and people acted out of a variety of motives—whether outright support for the regime, fear of the police or Gestapo, or a sense of detachment from the larger architecture of racial policies; “doing your job” in an authoritarian regime does not necessarily mean embracing that regime. In contrast, however, there were also people who resisted the Nazi regime, often to their own detriment, and there were even soldiers who refrained from engaging in genocide. [11] Some of them were executed for their actions; others were simply reassigned to new tasks. Issues of consent and coercion, resistance and complicity are extremely complex. We hope that the broad range of responses to the dictatorship and its crimes presented here will encourage users to ask tough questions like: it is realistic to expect most Germans to have acted with the same level of civil courage as the relatively small number who took action against the state?

The reality is that Hitler was both a popular politician who offered rapid economic recovery and territorial adjustments to a people beaten down by the Great War and economic depression, and a politician who inspired fear, conformity, and distress about the extent of his bellicose policies. Coercion and consent are not mutually exclusive in a dictatorship. Support for National Socialism could be combined with disapproval of specific policies. Loyalty to the Nazi cause and the war effort could be twinned with disapproval of brutal racism. Nationalism, belief in the Führer , concern for loved ones on the battlefield—a constellation of emotions and commitments can exist in a setting where top-down violence and fear of stepping out of line is widespread. The sources in this volume speak to these complexities. The Third Reich still attracts so much attention because it compels us to think through the nature of individual consent, the power of the state, the ability of demagogues to win over the public, and the dangers of watching rapid social and political change uncritically.

Germans could not predict the future. We have the benefit of hindsight, knowing that the Third Reich ended with bombed out cities, refugees clogging roads, and tens of millions of dead combatants and civilians. We must maintain some sensitivity to the voices of those who, at the time, simply tried to lead their lives without endangering themselves and their families. But we must also recognize the consequences of apathy, indifference, and fear, as well as the reality that many Germans knew of, approved of, and contributed to the brutality that suffused the Third Reich and that reveals itself in so many ways in the featured sources.

S. Jonathan Wiesen and Pamela Swett

Grade 11 – Unit 8

Grade 11 Learners

Table of Contents

About this unit.

The Cape Town Holocaust & Genocide Centre is pleased to offer a series of eight (8) units covering the following Grade 11 CAPS topic: Ideas of Race in the late 19th and 20th Centuries – What were the consequences when pseudoscientific ideas of Race became integral to government policies and legislation in the 19th and 20th centuries?

Case studies: Australia and the indigenous Australians; Nazi Germany and the Holocaust.

Unit 8 Case Study: Nazi Germany Part 4

In this unit you will learn about the following: - Stages 8-10 of Stanton’s 10 Stages of Genocide - The genocide of the Jews of Europe (the Holocaust) - The connection between this history and democratic South Africa

Graad 11 Leerling

Inhoudsopgawe

Oor hierdie eenheid.

Die Cape Town Holocaust & Genocide Centre is opgewonde om die 8 eenhede van die Graad 11 KABV (CAPS) aan te bied soos volg: Idees van Ras in die laat 19de en 20ste eeu – Wat was die gevolge toe die pseudo-wetenskaplike idees van Ras ‘n integrale deel van regeringsbeleid en wetgewing gevorm het in die 19de en 20ste eeu?

Eenheid 8 Gevalle studie: Nazi-Duitsland Deel 4

In hierdie eenheid sal jy oor die volgende leer: - Stadiums 8-10 van Stanton se 10 Stadiums van Volksmoorde - The volksmoord op die Jode van Europa (die Holocaust) - Die verbintenis van dié geskiedenis en demokratiese Suid-Afrika

Share with a friend

No comments.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Privacy Overview

- Advisory Board

- Announcements

- Participant Observations

- Site Updates

- Field Notes

- Comprehensive

- Generative Texts

- Archival Developments

- Clio’s Fancy

- Submissions

- Back Issues

- Working Group

Socio-Cultural Anthropology under Hitler: An Introduction to Four Case Studies from Vienna

Note to readers: This introduction seeks to draw attention to the three-volume collection examining Socio-Cultural Anthropology in Vienna during the Nazi period (1938-1945) , recently published in German and edited by Andre Gingrich and Peter Rohrbacher . The editors’ essay below is followed by brief essays in English based on a selection of chapters by Katja Geisenhainer, Lisa Gottschall , Gabriele Anderl, Ildikó Cazan-Simányi , Reinhold Mittersakschmöller, and Peter Rohrbacher. We thank the editors and authors for making their work available in this way, as a joint effort by our “Clio’s Fancy” and “Field Notes” sections, and invite readers to follow up with the complete work.– HAR editors.

Elaborating and interpreting anthropology’s history under Nazism is not only a continuing ethical, moral, and political obligation for the field today. It also represents a set of complex challenges in many of its empirical, methodological, and conceptual dimensions, open to debate and reflection by interested laypersons and experts in the relevant languages, regions, and periods but also from all other fields of anthropology and history as well. Through the present introduction to four case examples from Vienna, the authors seek to contribute to these debates by pointing out the relevance of well-researched archival evidence within sound methodological contexts. This is the indispensable prerequisite for advancing further debates and related research.

To a considerable extent, when Hitler’s party came to power in early 1933, socio-cultural anthropology ( Völkerkunde ) was institutionally separate from biological anthropology ( Humanbiologie or Physische Anthropologie ) at most museums and university institutes in Germany. This was also true for Austria after the “ Anschluss ” (“union,” or annexation) of March 1938. As a consequence of the Anschluss , Vienna became the second largest academic site in the “Third Reich.” Its institutional landscape for Völkerkunde included (as of the late 1920s) a university institute, a museum, a missionary educational center (since 1906), subdivisions in Vienna’s Academy of Sciences (after 1914), and the Anthropological Society of Vienna (as of 1870). In terms of size and institutional diversity, case studies from Vienna can therefore be taken as good indicators for how socio-cultural anthropology was carried out under Hitler and in exile: who profited from its practices, who stood by, and who suffered and resisted. All of these questions need to be raised and explored, but many of them cannot yet be fully answered.

Like elsewhere in the “Third Reich,” individual researchers and students were persecuted for “racial” and/or political reasons within Vienna’s institutions of socio-cultural anthropology. Entire institutions and research directions were dissolved or marginalized if they followed research orientations in conflict with Nazi priorities. What remained as quasi-legitimate socio-cultural anthropology under the Nazis was pushed, with considerable support by those involved, into research programs conspicuously connected to Nazi ideological priorities for German supremacist racism, for winning the war when it broke out, and for collaborating in practical activities serving the regime’s political agenda. What remained of socio-cultural anthropology under Nazi dictatorship contained as its core elements some prominent trends in (German) historical diffusionism in Vienna as elsewhere, the emerging networks of (German) functionalism (in Vienna until mid-1939), and local variants of a proto-structuralism outside Vienna. All of these directions were informed by varying versions of biological racism. Obvious intersections and parallels between the directions promoted as quasi-legitimate under the Nazis, and dominant paradigms in western socio-cultural anthropology after 1945 require further analysis and reflection, as one of us has pointed out (Gingrich 2010).

Socio-cultural anthropology under Hitler took on a radical agenda in its practical and empirical dimensions: addressing the (print and radio) media was one important element, while reaching out to the public through spectacular colonial and imperial museum exhibits and lectures was another. Pursuing “embedded” research in combat zones for army or espionage units was actively promoted, for example during Rommel’s North Africa campaign. Providing professional reviews to Himmler on how to promote SS justifications of annihilation and murder in East Europe was part of socio-cultural anthropologists’ “applied” routine. Last but not least, the publication of entertaining and bestselling books on exotic societies and their bizarre habits contributed—after passing censorship—to a prevailing sense of a smiling public normality so important to the regime under Joseph Goebbels. Behind the scenes, meanwhile, the SS engaged PhD candidates and young post-docs from socio-cultural anthropology and neighboring fields in the humanities to carry out enquiries among Jewish families who were about to be murdered and to do secret fieldwork in prison camps, both among gypsy families before they were deported to death camps and among POWs from Africa or Asia before they perished in forced labor or were recruited as “volunteers” to the SS or the Wehrmacht.

In Vienna, the new Nazi regime after 1938 quickly disbanded the Catholic missionary unit of St. Gabriel, and dismissed all senior representatives with explicit sympathies for an independent Austrian state. At the Museum of Ethnology, the old director with pro-German sympathies was able to hold on to his position because members of a previously clandestine Nazi cell now gained an official voice. At the University-based anthropology institute, the Nazi party member Hermann Baumann became the new director until 1945, with an aim to re-orientate the institute according to the Reich’s colonial interests in Africa. While the regime prepared for war and mass persecutions, Himmler installed and promoted a new research unit with socio-cultural anthropology on its central agenda in his notorious, elite research organization, the SS- Ahnenerbe (“ancestral heritage”). By contrast, the record of resistance among socio-cultural anthropologists is less disappointing than often assumed. In Vienna, this ranged from conservative anti-Nazi patriots to clandestine communists, many of them supporting the formation of the underground organization, O5 (where “5” stands for “e,” and “Oe” represents “Ö,” the first letter of the German word for Austria). In exile, several socio-cultural anthropologists supported local resistance groups in occupied Austria or they supported their British and US hosts’ war efforts.

These and many other details are presented and discussed by twenty-eight authors in our three recently published co-edited volumes: Völkerkunde zur NS-Zeit aus Wien (1938-1945): Institutionen, Biographien und Praktiken in Netzwerken (Gingrich and Rohrbacher 2021). Though this work is appearing in German, its topics will be of considerable interest to many readers internationally. We are therefore publishing four brief vignettes here, adapted from chapters in the three volumes, to introduce English readers to some of the work’s major themes and the wide variety of its examples. In keeping with the focus of “Clio’s Fancy” and the importance of neglected archives for this research, each piece also highlights the dispersed documents and collections which have allowed these stories to be told.

In her text, “ Marginalized in Central European Anthropology and Persecuted as a Jew: The Case of Marianne Schmidl ,” author Katja Geisenhainer (U Frankfurt/U Vienna) presents the example of a pioneer of mathematical anthropology and a cultural-historical expert in studying sub-Saharan basket weaving. She shows how this almost forgotten but brilliant scholar was persecuted and murdered by the Nazis. Schmidl was never able to complete her main research project on African basket weaving. Surviving family members’ memories and correspondence are the primary sources in this study.

“ Assisting in the Holocaust: Pro-Nazi Anthropologists from Vienna in Occupied Poland (1940–1944) ” by Lisa Gottschall (U Vienna) scrutinizes the activities of a largely unknown and forgotten doctoral graduate from Vienna’s Völkerkunde institute who prepared early measurements among the Jewish resident population around Kraków, before they were sent into that city’s ghetto. Parallel to that, he and two female colleagues were crucial to the Nazi “documentation” of Jewish residents on Tarnów’s main square, right before several hundred of them were deported into the death camps. The text presents a vivid example of the Nazis’ recruitment of ambitious junior anthropologists into their deadly schemes, and how some of their plans relied to an extent on new institutions, such as the IDO (Institute for German Studies in the East) in this case, which was set up after the dissolution of the Jagiellonian University.

Gabriele Anderl, Ildikó Cazan-Simányi, and Reinhold Mittersakschmöller are a team of freelance and museum staff authors in Vienna; their essay, “ Rivalries with Fatal Consequences ,” addresses an enduring competition during the Nazi period between two Indonesia specialists at Vienna’s Ethnology Museum. Indonesia had strategic importance for the Nazis, both as a recent colony of their Japanese allies and in view of Dutch source materials for research. One of the two contenders was Frederic M. Schnitger, an internationally widely read Dutch author with a partially Chinese Java background; his rival, a less qualified, local female party mentee, made accusations which led to Schnitger being sent to die in a concentration camp. The key sources here are museum archives and Gestapo files.

The contribution by Peter Rohrbacher (Austrian Academy of Sciences), “ A Priest in the Resistance: Father Wilhelm Schmidt and His Alliances in World War II ,” shows how Wilhelm Schmidt—a Catholic priest and missionary who founded the Vienna School of Ethnology—worked from exile in Switzerland, with covert support by the Vatican and British SOE, to sponsor Austrian defectors from the Wehrmacht who re-organized as anti-Nazi guerilla groups. This study draws upon the discovery of Schmidt’s day-to-day notebook from 1943-45.

These four diverse vignettes seek to attract readers’ interest to the relevant chapters in the three volumes, and to encourage further relevant research on the theme at large. The authors are grateful to the editors at HAR for their support and assistance in making this set of contributions possible.

Other essays from this collection:

Katja Geisenhainer, “Marginalized in Central European Anthropology and Persecuted as a Jew: The Case of Marianne Schmidl.”

Lisa Gottschall, “Assisting in the Holocaust: Pro-Nazi Anthropologists from Vienna in Occupied Poland (1940–1944).”

Gabriele Anderl, Ildikó Cazan-Simányi and Reinhold Mittersakschmöller, “Rivalries with Fatal Consequences.”

Peter Rohrbacher, “A Priest in the Resistance: Father Wilhelm Schmidt and His Alliances in World War II .”

Gingrich, Andre. 2010. “Alliances and Avoidance: British Interactions with German-speaking Anthropologists, 1933–1953.” In Culture Wars: Context, Models, and Anthropologists’ Accounts , edited by Deborah James, Evelyn Plaice, and Christina Toren, 19-31. Oxford and New York: Berghahn.

Gingrich, Andre, and Peter Rohrbacher, eds. 2021. Völkerkunde zur NS-Zeit aus Wien (1938-1945): Institutionen, Biographien und Praktiken in Netzwerken . Veröffentlichungen zur Sozialanthropologie 27, 3 volumes. Vienna: Verlag der ÖAW. https://verlag.oeaw.ac.at/produkt/voelkerkunde-zur-ns-zeit-aus-wien-1938-1945/99200565

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .