Crafting Authentic Anxiety Descriptions in Writing: A Comprehensive Guide

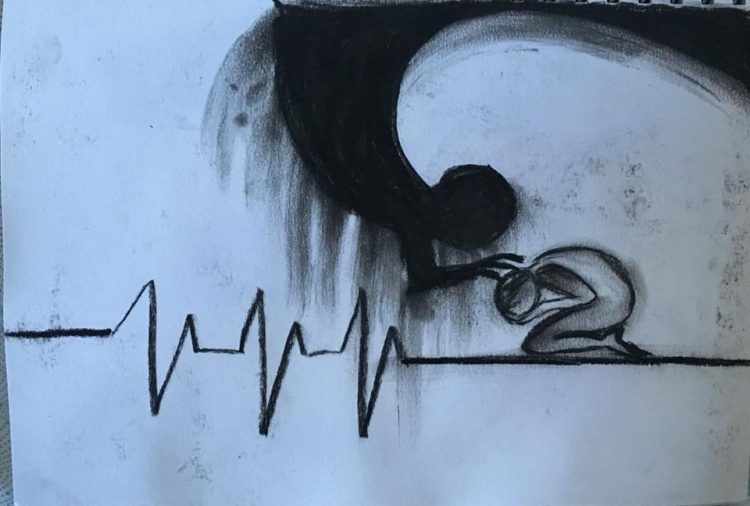

Putting emotions into words can be a tough task, especially when it’s something as complex as anxiety. You’ve likely been there, staring at a blank page, trying to capture the essence of a feeling that’s as elusive as it is powerful.

Writing about anxiety isn’t just about stating the facts. It’s about painting a picture that resonates with readers, making them feel what you’re trying to convey. This article will guide you through the process, providing you with the tools and techniques you need to accurately and effectively describe anxiety in your writing.

Stay with us as we delve into the intricacies of anxiety, exploring its various facets and how to best articulate them. By the end, you’ll be equipped to write about anxiety in a way that’s both authentic and compelling.

Understanding Anxiety

Before diving into how to describe anxiety in your writing, it’s crucial to understand what anxiety really is . Anxiety isn’t just a sense of worry or unease. It’s a complex beast, laced with multi-faceted layers, seeping into different corners of a person’s life and mind.

Anxiety doesn’t strike only in dramatic moments. Often, it’s a quiet monster – subtly showing up in mundane daily tasks. It creeps up when you’re making a cup of coffee, checking emails, or performing any of the countless tasks that may seem ordinary to others but may feel like a mountain to you when you’re dealing with anxiety. It catches you unawares, often when least expected.

Let’s look at some key points that are the hallmarks of anxiety. These are not the only symptoms but are common experiences for many dealing with anxiety. This understanding will help you while describing it in your writing.

- Excessive worry : Chronic and persistent worry about everyday situations.

- Restlessness : A feeling of being “on edge” or “unable to sit still”.

- Easily fatigued : A constant state of tiredness, regardless of physical exertion.

- Irritability : Quick to react or get angry over trivial issues.

- Sleep issues : Difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep.

Exploring these traits will help you inject authenticity into your portrayal of characters grappling with anxiety. It’s not about painting a dramatic image. It’s more about weaving these everyday experiences into your narrative. Your characters aren’t always trembling with fear.

Sometimes, your characters are just tired, irritable, or struggling to sleep. Sometimes, they’re caught in a vortex of relentless worry that clings even in the quietest moments. This closer look into the heart of anxiety will enable you to paint a picture that’s as real as it is raw.

In the following sections, we’ll delve deeper into practical techniques to describe anxiety effectively in your writing.

The Complexity of Emotions

Diving deeper into the quandary of describing anxiety in writing, you’ll encounter the larger picture – The Complexity of Emotions. Emotions aren’t easily boxed into specific labels. They’re intricate, layered, and often interrelated, transforming the task of tracing the contours of anxiety into a nuanced endeavor.

When writing about anxiety, you aren’t just detailing a singular emotion. Often, it’s a web of feelings like uneasiness, apprehension, dread, and more. Not only that, it’s about the physical sensations accompanying those feelings – a quickened heartbeat, a pit in the stomach, or tense muscles. This level of detail will enhance your depiction of anxiety, making it feel relatable and real.

However, let’s bring it to this premise: everyone experiences anxiety differently. A situation that makes one person anxious might not cause the same reaction in someone else. This is where subjectivity comes into play. The key isn’t to depict anxiety as how you presume others feel it; rather, it’s about illustrating how your characters experience it from their subjective perspective.

For instance, if a character fears public speaking, his anxiety might manifest as a racing heartbeat and a feeling of impending doom before stepping onto the stage. Conversely, if a different character fears abandonment, her anxiety could be demonstrated through insomnia ridden nights and a constant state of worry about her loved ones leaving her.

Let’s look at this from another angle: the perception or interpretation of anxiety is just as critical. Your character’s apprehension at being alone in a dark alley might seem ludicrous to another character who thrives in solitude and quiet. This contrast offers a compelling angle to your narrative, infusing it with multiple layers of understanding and empathy.

Remember, writing about anxiety means delving into its complexities and subtleties. It’s about reflecting its varying manifestations, implicating its physical and emotional aspects, and acknowledging its subjective nature. Appreciate the intricacies and present them to your readers, allowing them to empathize with your characters’ emotional journey.

Conveying Anxiety through Words

This journey takes a well-choreographed dance between the writer’s mind and their writing tool to portray the multifaceted nature of anxiety. When you’re doing this, it’s essential not to shy away from the dizzying mix of feelings, thoughts, and physical sensations associated with anxiety.

Diving right into the specifics, show, don’t just tell , is a critical rule to keep in mind here. Telling a reader that your character is anxious provides them with a foundational understanding. However, it’s showing them the churning stomach, the racing thoughts, the trembling hands, and the tight chest that really lures them in into empathizing with the character’s state of mind. Your narrative should aim to let a reader experience the anxiety alongside your character.

Let’s consider how word choice can play a significant role. Think about how you can utilize verbs, adjectives, and adverbs to your advantage. For example, instead of simply writing “he was anxious”, why not paint a more vivid picture? “His eyes darted around the room nervously, hands trembling like leaves buffeted by the autumn wind, heart pounding as if trying to break free from his chest.” This provides a deeper, more intimate view into the character’s emotional state.

Additionally, metaphors and similes are handy tools. Using these can create imagery that resonates with readers, allowing them to understand the severity and overwhelming nature of anxiety. Comparisons can make an abstract concept more tangible.

Nevertheless, it’s crucial to remember that anxiety isn’t a one-size-fits-all experience. It varies greatly from person to person. To authentically depict this reality, you should vary your descriptions, tailoring them to your unique characters’ perspectives and experiences. Crafting these descriptive details might take some time and thought, but this intricate process is what will make your narrative relatable and believable.

In the end, the purpose of conveying anxiety through words is to breathe life into your writing. Seamless integration of realistic descriptions can make your narrative more compelling, pulling the reader more in-depth into your story. But keep in mind, even if there’s no perfect way to pen anxiety, your aim should be to create a picture that’s authentic, relatable, and resonant. Let your characters’ anxiety be as nuanced and complex as it is in real life. Write with empathy and let your words reflect the reality of those struggling with anxiety.

Using Vivid Descriptions

You’ve grasped the concept, now let’s delve deeper into how to execute those vivid descriptions that truly capture the essence of anxiety. Remember, your aim isn’t just to tell your readers about anxiety – you want them to feel it, see it, and derive a true understanding of what it means.

Begin by honing in on the physical sensations that often accompany anxiety. How does an anxious person feel? Does their heart pound like a bass drum? Does their skin erupt with cold sweat, shivers cascading down their spine? Does it feel like a concrete slab pressing on the chest? These physiological responses are universal, and therefore, by incorporating them into your writing, it makes the depiction of anxiety more relatable.

Next, you must invest thought into the mental aspect of anxiety. It’s as vital as the physical, if not more. What goes on in an anxious mind? Is it a whirling maelstrom of worries, a ticking time bomb of impending doom, or an incessant echo of negative thoughts? Don’t hesitate to use powerful metaphors and similes. They draw readers into the character’s mind, allowing them to experience their llived reality.

Remember the uniqueness of your character . Each person experiences anxiety differently. Link these descriptions to aspects of their life. Tailor the depiction of anxiety to suit your character’s background, personality, and predicament. A brave firefighter will perceive anxiety differently from a timid teenager. Ensure your descriptions reflect this variation.

Creating an Emotional Connection

You’re not just writing about anxiety; you’re aiming to create an emotional bond between your reader and your characters. Authenticity in your description is the key to achieving this.

Empathy is what you’re striving to evoke. Place yourself in your characters’ shoes and dig deep into their emotions and psychological state. This immersion will provide you with genuine and compelling descriptions. But how can you craft such vivid portrayals?

Make it Personal

Being personal doesn’t mean that you have to share your own experiences explicitly. It means transforming universal feelings of anxiety into unique character-experienced emotions and events. It’s about understanding that each character’s anxieties are unique to them.

So, imagine your character: What are their fears, what are their triggers? Now, mold those elements into your narrative.

Show, Don’t Tell

The well-trodden advise, “show, don’t tell,” definitely holds validity here. Instead of stating your character is anxious, show it. Make your reader feel the character’s heartbeat quicken, their palms get sweaty, let them hear the rush of confused thoughts.

Making use of strategic metaphors and similes here will allow your reader to visualize and empathize with your character’s experience.

Highlight the Contrast

Animate the difference between the character’s calm state and anxious state. This will make the portrayal of anxiety drastic and hard-hitting. Drawing this contrast will underline the real impact of anxiety, capturing reader’s attention and creating a lasting impression.

Remember, the goal is not to simply describe an anxious state but to make your reader feel it, empathize with it, and understand it through your character’s perspective. The more real your portrayal, the deeper the emotional connection will be.

You’ve learned the art of describing anxiety in writing. You now understand the power of authenticity, the importance of personalizing your character’s fears, and the effectiveness of showing rather than telling. You’ve grasped the significance of sensory details and strategic use of metaphors and similes. Remember, contrasting calm with anxiety can create a lasting impression. Now it’s your turn to bring anxiety to life in your writing, making your reader feel and understand it from your character’s perspective. The journey may be challenging, but the result is worth it. Your writing will be more relatable, more engaging, and more impactful. So, go ahead, apply these insights and watch your characters come alive on the page.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can an author establish an emotional bond between readers and characters.

Authors can build an emotional bond by creating genuine descriptions of the characters’ emotional states, particularly their anxieties. This can be done by understanding each character’s unique fears and triggers, and presenting these emotions authentically.

What is the role of authenticity in writing about a character’s anxiety?

Authenticity is crucial in writing about a character’s anxiety. Realistic and relatable descriptions can evoke empathy in the reader, making them connect more deeply with the character’s experiences.

What is the significance of personalized descriptions in showcasing a character’s anxiety?

Personalized descriptions add depth to the character’s anxiety, making it uniquely theirs. By exploring the character’s individual fears and triggers, the descriptions can lead to a more profound reader’s understanding.

How can sensory details and metaphors enhance the description of a character’s anxiety?

By showing rather than telling, authors can utilize sensory details and strategic metaphors to vividly illustrate the character’s anxiety. Such devices can help readers virtually “feel” the anxiety, leading to a more immersive reading experience.

Why is it important to contrast a character’s calm state with their anxious state?

Contrasting a calm state with an anxious one helps to underscore the intensity of the anxiety. This contrast also helps create a lasting impression on the reader about the character’s emotional journey.

Related Posts

DUA For Anxiety

How to Treat High Functioning Anxiety

Editor’s Note: In this interview on writing anxiety, instructor Giulietta Nardone describes what creative writing anxiety is, what causes it, and—most importantly—how to get over writing anxiety.

What is writing anxiety?

There are many people who would like to start writing, or to take a writing class, but they never get started because the critical voice that lives in their head—which we all have—tells them they’re not good enough to write, that no one wants to hear what they want to say. So they don’t bother.

People with writing anxiety might even get physical symptoms if they try to write, or to over-edit: perspiring, trembling, shortness of breath, pacing, and so on.

What is the opposite of writing anxiety?

I would say enthusiasm, excitement, exploration: knowing you want to dive in, and feeling free about that. A good feeling.

What causes writing anxiety?

I believe these things start when we’re quite young, and I would trace it to in our educational system, where things are right or wrong. I once taught a tween, and we did a creative writing exercise. After it was done, she wanted to know if she had the right answer.

That’s kind of the opposite thing from what you need to be a writer. You need to explore, and you don’t know what the right answer is when you start, because the right answer is the right answer for you .

I believe these things start when we’re quite young, and I would trace it to in our educational system, where things are right or wrong. That’s kind of the opposite from what you need to be a writer.

Creative writing is about exploring: going through the different layers of your life, of your memory, coming up with something that you want said. And if you’re suffering from perfectionism, which is very common, it can be difficult. I’ve worked with people who would never finish a project, because they had to be perfect. Most of my stories, even the ones I’ve had published, I don’t think were perfect.

I think too, people are afraid to fail, what they label as failure. There isn’t really such thing—again, it’s just about exploration. It’s getting things off your chest, learning about yourself. Sometimes people heal through writing. There are so many reasons to start writing. You’ve got to give yourself permission to start.

What experiences have you had with writing anxiety in your own writing?

For myself, an example is not writing but public speaking. When I was in college, I kept changing majors, because I was terrified to give a presentation. If I’d walk into a class and if giving a presentation was on the syllabus, I’d leave.

I knew I had to get over it by taking a speech class.

I was terrified. It took me a while to sign up for it—“I don’t want to do this.” Then I did sign up for it. The thing I feared in my life ended up being the best thing that ever happened to me. I keep saying, “What would have happened if I didn’t sign up?” Many years later, I wrote an essay about taking the class, and sold it to the college where I took the class. I got a lot of good feedback from people with similar fears.

There’s a continuum of fear when it comes to writing. Maybe you start, and then there’s a fear to finish, or a fear to send it out.

I work privately with writers, and a lot of writers are afraid to finish their stories and then send them out. There’s a continuum of fear when it comes to writing. Maybe you start, and then there’s a fear to finish, or a fear to send it out.

On that topic: my first essay in the Boston Globe was something I wanted for a long time. They accepted my essay, I went and got the Sunday paper, opened and read it, and thought, “This is horrible. No one can read this.” It was way too personal. I wanted to drive around and grab every Globe and shred it. Then one of my friends caught me and said, “I saw your essay. It was great.” So writing anxiety happens with writers who are getting published too.

How do you recommend writers work with writing anxiety?

Write. It may sound contrarian, but you have to do the thing you’re afraid of.

Write. You have to do the thing you’re afraid of. You’ve got to start—that’s the tough part.

That’s always hard for me. I was afraid to hike into a canyon, so I went to Bryce Canyon with my husband and I took little baby steps the whole way down. I made it down and it was really beautiful, and I was glad I did it. I think I could do the Grand Canyon.

So just write. Hopefully take a class, with some guidance. You’ve got to start. The tough part is to start.

What can you tell us about your new course, Overcome Writing Anxiety: Boost Your Storytelling Confidence in Four Short Weeks! ?

This is a supportive, gentle program to get folks writing. They want to learn to trust each other, and most importantly trust themselves. We’re going to start short, with poetry, and then go a little longer with some flash fiction, and then creative nonfiction, maybe a short memoir. But we’re not going to write these long missives, so that no one gets frightened or overwhelmed.

We’ll be building up people’s courage every week. It’ll be fun and functional. I put it together influenced a little bit by a talk by Dr. Seuss. I love Dr. Seuss’s books, so I set it up with a Dr. Seuss lilt. I wanted it to be fun like Dr. Seuss. He was also very brave with his writing and his illustrations.

https://writers.com/classes/overcome-writing-anxiety-and-write-with-confidence

I see it as an inspirational program where you can build up your writing courage, and leave with some stories you may want to share with your family and friends. People will leave much more brave. And this is writing, but you can apply what you learned to other things: painting or singing or dance, whatever. I make myself do that all the time, and I’m always glad I do: I’ve done some great things just jumping right in.

I would like people who are feeling reluctant about writing to take a chance and join us. In my experience, it’s the risks we don’t take that can make us feel incomplete. It’s about getting comfortable taking risks, so you can do a lot of the things in life that you want to do, but you’re kind of keeping yourself from doing.

Looking for more practical guidance on tackling writing anxiety? See instructor Dennis Foley ‘s advice on the topic .

Frederick Meyer

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Writing Anxiety

What this handout is about.

This handout discusses the situational nature of writer’s block and other writing anxiety and suggests things you can try to feel more confident and optimistic about yourself as a writer.

What are writing anxiety and writer’s block?

“Writing anxiety” and “writer’s block” are informal terms for a wide variety of apprehensive and pessimistic feelings about writing. These feelings may not be pervasive in a person’s writing life. For example, you might feel perfectly fine writing a biology lab report but apprehensive about writing a paper on a novel. You may confidently tackle a paper about the sociology of gender but delete and start over twenty times when composing an email to a cute classmate to suggest a coffee date. In other words, writing anxiety and writers’ block are situational (Hjortshoj 7). These terms do NOT describe psychological attributes. People aren’t born anxious writers; rather, they become anxious or blocked through negative or difficult experiences with writing.

When do these negative feelings arise?

Although there is a great deal of variation among individuals, there are also some common experiences that writers in general find stressful.

For example, you may struggle when you are:

- adjusting to a new form of writing—for example, first year college writing, papers in a new field of study, or longer forms than you are used to (a long research paper, a senior thesis, a master’s thesis, a dissertation) (Hjortshoj 56-76).

- writing for a reader or readers who have been overly critical or demanding in the past.

- remembering negative criticism received in the past—even if the reader who criticized your work won’t be reading your writing this time.

- working with limited time or with a lot of unstructured time.

- responding to an assignment that seems unrelated to academic or life goals.

- dealing with troubling events outside of school.

What are some strategies for handling these feelings?

Get support.

Choose a writing buddy, someone you trust to encourage you in your writing life. Your writing buddy might be a friend or family member, a classmate, a teacher, a colleague, or a Writing Center tutor. Talk to your writing buddy about your ideas, your writing process, your worries, and your successes. Share pieces of your writing. Make checking in with your writing buddy a regular part of your schedule. When you share pieces of writing with your buddy, use our handout on asking for feedback .

In his book Understanding Writing Blocks, Keith Hjortshoj describes how isolation can harm writers, particularly students who are working on long projects not connected with coursework (134-135). He suggests that in addition to connecting with supportive individuals, such students can benefit from forming or joining a writing group, which functions in much the same way as a writing buddy. A group can provide readers, deadlines, support, praise, and constructive criticism. For help starting one, see our handout about writing groups .

Identify your strengths

Often, writers who are experiencing block or anxiety have a worse opinion of their own writing than anyone else! Make a list of the things you do well. You might ask a friend or colleague to help you generate such a list. Here are some possibilities to get you started:

- I explain things well to people.

- I get people’s interest.

- I have strong opinions.

- I listen well.

- I am critical of what I read.

- I see connections.

Choose at least one strength as your starting point. Instead of saying “I can’t write,” say “I am a writer who can …”

Recognize that writing is a complex process

Writing is an attempt to fix meaning on the page, but you know, and your readers know, that there is always more to be said on a topic. The best writers can do is to contribute what they know and feel about a topic at a particular point in time.

Writers often seek “flow,” which usually entails some sort of breakthrough followed by a beautifully coherent outpouring of knowledge. Flow is both a possibility—most people experience it at some point in their writing lives—and a myth. Inevitably, if you write over a long period of time and for many different situations, you will encounter obstacles. As Hjortshoj explains, obstacles are particularly common during times of transition—transitions to new writing roles or to new kinds of writing.

Think of yourself as an apprentice.

If block or apprehension is new for you, take time to understand the situations you are writing in. In particular, try to figure out what has changed in your writing life. Here are some possibilities:

- You are writing in a new format.

- You are writing longer papers than before.

- You are writing for new audiences.

- You are writing about new subject matter.

- You are turning in writing from different stages of the writing process—for example, planning stages or early drafts.

It makes sense to have trouble when dealing with a situation for the first time. It’s also likely that when you confront these new situations, you will learn and grow. Writing in new situations can be rewarding. Not every format or audience will be right for you, but you won’t know which ones might be right until you try them. Think of new writing situations as apprenticeships. When you’re doing a new kind of writing, learn as much as you can about it, gain as many skills in that area as you can, and when you finish the apprenticeship, decide which of the skills you learned will serve you well later on. You might be surprised.

Below are some suggestions for how to learn about new kinds of writing:

- Ask a lot of questions of people who are more experienced with this kind of writing. Here are some of the questions you might ask: What’s the purpose of this kind of writing? Who’s the audience? What are the most important elements to include? What’s not as important? How do you get started? How do you know when what you’ve written is good enough? How did you learn to write this way?

- Ask a lot of questions of the person who assigned you a piece of writing. If you have a paper, the best place to start is with the written assignment itself. For help with this, see our handout on understanding assignments .

- Look for examples of this kind of writing. (You can ask your instructor for a recommended example). Look, especially, for variation. There are often many different ways to write within a particular form. Look for ways that feel familiar to you, approaches that you like. You might want to look for published models or, if this seems too intimidating, look at your classmates’ writing. In either case, ask yourself questions about what these writers are doing, and take notes. How does the writer begin and end? In what order does the writer tell things? How and when does the writer convey their main point? How does the writer bring in other people’s ideas? What is the writer’s purpose? How is that purpose achieved?

- Read our handouts about how to write in specific fields or how to handle specific writing assignments.

- Listen critically to your readers. Before you dismiss or wholeheartedly accept what they say, try to understand them. If a reader has given you written comments, ask yourself questions to figure out the reader’s experience of your paper: What is this reader looking for? What am I doing that satisfies this reader? In what ways is this reader still unsatisfied? If you can’t answer these questions from the reader’s comments, then talk to the reader, or ask someone else to help you interpret the comments.

- Most importantly, don’t try to do everything at once. Start with reasonable expectations. You can’t write like an expert your first time out. Nobody does! Use the criticism you get.

Once you understand what readers want, you are in a better position to decide what to do with their criticisms. There are two extreme possibilities—dismissing the criticisms and accepting them all—but there is also a lot of middle ground. Figure out which criticisms are consistent with your own purposes, and do the hard work of engaging with them. Again, don’t expect an overnight turn-around; recognize that changing writing habits is a process and that papers are steps in the process.

Chances are that at some point in your writing life you will encounter readers who seem to dislike, disagree with, or miss the point of your work. Figuring out what to do with criticism from such readers is an important part of a writer’s growth.

Try new tactics when you get stuck

Often, writing blocks occur at particular stages of the writing process. The writing process is cyclical and variable. For different writers, the process may include reading, brainstorming, drafting, getting feedback, revising, and editing. These stages do not always happen in this order, and once a writer has been through a particular stage, chances are they haven’t seen the last of that stage. For example, brainstorming may occur all along the way.

Figure out what your writing process looks like and whether there’s a particular stage where you tend to get stuck. Perhaps you love researching and taking notes on what you read, and you have a hard time moving from that work to getting started on your own first draft. Or once you have a draft, it seems set in stone and even though readers are asking you questions and making suggestions, you don’t know how to go back in and change it. Or just the opposite may be true; you revise and revise and don’t want to let the paper go.

Wherever you have trouble, take a longer look at what you do and what you might try. Sometimes what you do is working for you; it’s just a slow and difficult process. Other times, what you do may not be working; these are the times when you can look around for other approaches to try:

- Talk to your writing buddy and to other colleagues about what they do at the particular stage that gets you stuck.

- Read about possible new approaches in our handouts on brainstorming and revising .

- Try thinking of yourself as an apprentice to a stage of the writing process and give different strategies a shot.

- Cut your paper into pieces and tape them to the wall, use eight different colors of highlighters, draw a picture of your paper, read your paper out loud in the voice of your favorite movie star….

Okay, we’re kind of kidding with some of those last few suggestions, but there is no limit to what you can try (for some fun writing strategies, check out our online animated demos ). When it comes to conquering a block, give yourself permission to fall flat on your face. Trying and failing will you help you arrive at the thing that works for you.

Celebrate your successes

Start storing up positive experiences with writing. Whatever obstacles you’ve faced, celebrate the occasions when you overcome them. This could be something as simple as getting started, sharing your work with someone besides a teacher, revising a paper for the first time, trying out a new brainstorming strategy, or turning in a paper that has been particularly challenging for you. You define what a success is for you. Keep a log or journal of your writing successes and breakthroughs, how you did it, how you felt. This log can serve as a boost later in your writing life when you face new challenges.

Wait a minute, didn’t we already say that? Yes. It’s worth repeating. Most people find relief for various kinds of anxieties by getting support from others. Sometimes the best person to help you through a spell of worry is someone who’s done that for you before—a family member, a friend, a mentor. Maybe you don’t even need to talk with this person about writing; maybe you just need to be reminded to believe in yourself, that you can do it.

If you don’t know anyone on campus yet whom you have this kind of relationship with, reach out to someone who seems like they could be a good listener and supportive. There are a number of professional resources for you on campus, people you can talk through your ideas or your worries with. A great place to start is the UNC Writing Center. If you know you have a problem with writing anxiety, make an appointment well before the paper is due. You can come to the Writing Center with a draft or even before you’ve started writing. You can also approach your instructor with questions about your writing assignment. If you’re an undergraduate, your academic advisor and your residence hall advisor are other possible resources. Counselors at Counseling and Wellness Services are also available to talk with you about anxieties and concerns that extend beyond writing.

Apprehension about writing is a common condition on college campuses. Because writing is the most common means of sharing our knowledge, we put a lot of pressure on ourselves when we write. This handout has given some suggestions for how to relieve that pressure. Talk with others; realize we’re all learning; take an occasional risk; turn to the people who believe in you. Counter negative experiences by actively creating positive ones.

Even after you have tried all of these strategies and read every Writing Center handout, invariably you will still have negative experiences in your writing life. When you get a paper back with a bad grade on it or when you get a rejection letter from a journal, fend off the negative aspects of that experience. Try not to let them sink in; try not to let your disappointment fester. Instead, jump right back in to some area of the writing process: choose one suggestion the evaluator has made and work on it, or read and discuss the paper with a friend or colleague, or do some writing or revising—on this or any paper—as quickly as possible.

Failures of various kinds are an inevitable part of the writing process. Without them, it would be difficult if not impossible to grow as a writer. Learning often occurs in the wake of a startling event, something that stirs you up, something that makes you wonder. Use your failures to keep moving.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Hjortshoj, Keith. 2001. Understanding Writing Blocks . New York: Oxford University Press.

This is a particularly excellent resource for advanced undergraduates and graduate students. Hjortshoj writes about his experiences working with university students experiencing block. He explains the transitional nature of most writing blocks and the importance of finding support from others when working on long projects.

Rose, Mike. 1985. When a Writer Can’t Write: Studies in Writer’s Block and Other Composing-Process Problems . New York: Guilford.

This collection of empirical studies is written primarily for writing teachers, researchers, and tutors. Studies focus on writers of various ages, including young children, high school students, and college students.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

BRYN DONOVAN

tell your stories, love your life

- Writing Inspiration

- Semi-Charmed Life

- Reading & Research

- Works In Progress.

Master List of Ways to Describe Fear

People have been asking me for this list for such a long time! If you write horror, suspense, mystery, or any kind of fiction with a scary scenes, you need to know how to describe fear.

This list can get you started. It’s a lot of phrases describing fear, including physical reactions, physical sensations, facial expressions, and other words you can use in your novel or in other creative writing.

I’ve included some that can work for uneasiness or anxiety, but most of these are for real terror. You can alter them to fit your sentence or your story, and they’ll likely inspire you to come up with your own descriptions.

Bookmark or pin this page for your reference—it might save you a lot of time in the future. I’ll probably add to it now and again!

fear paralyzed him

his terror mounted with every step

she fought a rising panic

fear tormented her

her heart was uneasy

her heart leaped into her throat

his heart hammered in his chest

his heart pounded

terror stabbed his heart

his heart jumped

her heart lurched

a fear that almost unmanned him

his body shook with fear

she trembled inside

he suppressed a shiver

panic surged through him

her fear spiked

he was in a complete state of panic

she could feel nothing but blind terror

his legs were wobbly with fear

she sweated with fear

his hands were cold and clammy

she was weighed down by dread

dread twisted in her gut

his stomach clenched

fear fluttered in her stomach

her belly cramped

he felt like he might throw up

she was sick with fear

she was frightened down to the soles of her shoes

he was icy with panic

her body went cold with dread

raw panic was in her voice

her voice was thick with fear

his voice was edged with fear

terror thundered down on him

fear caught her in its jaws

fear clawed up her throat

terror sealed her throat

fear gripped her throat

his throat tightened

then she knew real terror was

he was frantic with fear

she was half mad with terror

the color drained from her face

his face was ashen

she blanched

dread gnawed at his insides

dread had been growing in him all day

fresh terror reared up within her

fear choked him

terror stole her words

he was mute with horror

her voice was numb with shock

his voice was shrill with terror

her defiant words masked her fear

her body felt numb

his blood froze in his veins

terror coursed through her veins

fear throbbed inside her

his panic fueled him

adrenaline pumped through his body

adrenaline crashed through her

fear pulsed through him

her scalp prickled

the hairs on the back of her neck stood up

his mouth went dry

his bones turned to jelly

her bones turned to water

she froze with horror

he didn’t dare to move

terror struck her

he was too frightened to lift her head

she was too frightened to scream

his mouth was open in a silent scream

he cringed with fear

she cowered

he shrank back in fear

she flinched

a bolt of panic hit her

terror streaked through him

her terror swelled

his panic increased

anxiety eclipsed his thoughts

panic flared in her eyes

his eyes were wild with terror

her eyes darted from left to right

she feared to close her eyes

he lay awake in a haze of fear

she walked on in a fog of fear

his eyes widened with alarm

she tried to hide her fear

he struggled to conceal his shock

fear crept up her spine

fear trickled down her spine

panic seized his brain

she felt a flash of terror

fear took hold of him

fear flooded through her being

she ordered a drink to drown the panic

he arranged and re-arranged the items on his desk

a nameless dread engulfed him

I bet you came up with other ideas as you were reading!

For more writing lists, check out my book Master Lists for Writers , if you don’t have it yet! A lot of writers use it to make writing go faster, especially when it comes to descriptions.

And if you’re not following the blog already, sign up below—I share lots of writing resources. Thanks so much for reading, and happy writing!

Related Posts

Share this:

30 thoughts on “ master list of ways to describe fear ”.

Thank you, Bryn. I can certainly use this list as I go through and clean up my novel. There are some places that need a stronger element of fear.

Hi Bonnie! So glad this was coming at the right time! 🙂

Love the book and the above list! Thank you for taking the time to compile all of it. So appreciated!

Oh thank you! I’m so glad you like it!

I just love your lists. I often refer to them when I’m stuck. That book is right next to the dictionary and thesaurus when I write.

I’m so glad you like them, Erin! I’m honored. 🙂

I was searching for the perfect list to describe fear. I stumbled across your blog and I am glad that I did, you literally saved my butt out there!!? I got an A* because of you ! Thankyou!!❤❤

Aww, I’m so glad to hear this! 🙂

Thanks for compiling this list. Much needed.

Aw thanks, Ezekiel! So glad you like it!

What a terrifying, fantastical list. Thank you, Bryn

Haha, thanks, Bryan! When I read back over it, I did feel a little creeped out. 🙂

I have a scene coming up that this will be perfect for. Thank you for sharing. Bookmarking now!

Hi Sarah! So glad it’ll be useful! Sounds like you have an exciting scene coming up 🙂

- Pingback: How to Write a Novel: Resources - MultiTalented Writers

This is a great list! Thank you, Bryn.

Wow! When I read it, I was SO / COMPLETELY creeped out!???

Ha! You know what, when I make these lists, I always start feeling the emotions, too!

I’m thankful for your help. It is great to see these lists. Many blessings ❤️

I have been a bibliophile since long, but never before did I read so many blogs in a sequence. I am really amazed to have found them.Thanks a ton . Superb work .

You saved my life ! Thank you a lot ???

So glad to hear that! Happy writing 🙂

Thanks… It’s good to know tath someone is making life easier for those interested in writing.

ohhh ,how grateful i am for this list it will come in handy so thankyou

- Pingback: Master List of Actions That Show Fear

Thank you so much for this list! It is exactly what I was looking for. I ordered the book 🙂

Thanks for ordering the book, Laila. I hope you like it! And glad this list worked for you!

This is an amazing list. I saw in your other comment that you have a book…?

I wanted to tell you that I often return to this page when I am stumped coming up with a way to write some specific reaction. Sometimes I just use one of the ideas you offer directly, and other times something here gives me an idea I riff off of to create something new. Thank you so much for compiling this list!

I riffed this time (last line): “Still feeling the sadness of Manzoa’s fate and wondering what this place was and why he was here, Goff cautiously walked over to the desk. A quill still wet with thick black ink rested next to a sheet of parchment filled with writing in a language he couldn’t read. Crude drawings made with heavy strokes were set within the words. Some of them were disturbing — a bleeding hand cut open with a knife and a person floating lifeless below a ghoul with black eyes poised to attack. He stared at the words, hoping that just like when he traveled back in time to Monstraxen, he would be able to understand them. As he stared, the ink on the page disappeared like water soaking into a sponge. A spider of panic crawled up his spine.”

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from BRYN DONOVAN

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

How to Describe Worry in Writing

By: Author Paul Jenkins

Posted on Published: July 4, 2022 - Last updated: January 5, 2024

Categories Writing , Creativity , Filmmaking , Storytelling

It can be difficult to write about a worried character. They don’t always show their worries on the surface and may not even know what’s going on themselves. But that doesn’t mean you can’t create a believable and compelling character who worries all the time. In this post, we’ll show you the best way to create a worried character and how to make them feel real to your readers in your creative writing.

Characters Are Worried for a Reason – Give Readers a Glimpse

When writing about a character who worries, it’s important to give your readers some insight into why they worry. Otherwise, the worry may come across as unfounded or irrational.

So how do you describe worry in a way that’s both believable and understandable?

One way is to focus on the physical sensations of worry. This includes things like a racing heart, sweaty palms, or butterflies in the stomach. These physical reactions can be triggered by a variety of things, such as anticipation of a future event or memories of a past event.

- By describing the physical sensations of worry, you can help your readers understand and sympathize with your character’s inner turmoil.

- Another way to describe worry is to focus on the thought process itself. What goes through someone’s mind when they feel anxious or stressed? Often, worry is based on irrational thoughts or fears. This can mean thinking an upcoming event is catastrophic or thinking about a past mistake. By showing how these thoughts contribute to the feelings of worry, you can help your readers understand the person’s mental state.

Show How the Character’s Worry Impacts Their Actions

All characters face worry or stress in their lives, and these worries can greatly affect the way they think, speak, and act. As a writer, it’s important to capture this sense of worry in your writing to create fully developed and believable characters.

One way to show how worry affects a character is through their thoughts. A character who worries may be thinking about it constantly, even when she should be focusing on something else.

In their mind, thoughts circle around the worst-case scenario, or they replay past events over and over again, trying to find a clue as to what went wrong. This preoccupation with worry can lead to insomnia, anxiety, and depression.

Another way to show how worry affects a person is through their words. A worried person may speak faster than usual, or they may stumble over their words and stutter.

They may also have difficulty concentrating on a conversation and may digress and worry in the middle of a sentence.

In addition, a person who worries may blurt out things they wouldn’t normally say – they may say something that gives too much away, or they may make a raunchy joke. This kind of behavior says a lot about a character’s personality and state of mind.

Characters who worry often worry about what if.

- What if I’m not good enough?

- What if I’m not prepared?

- What if I fail?

This way of thinking leads to a sense of fear and unease that can be conveyed by both the person’s thoughts and actions. Social anxiety can be a big part of what is going on.

For example, a person who’s worried about an upcoming exam might be pacing, biting their nails, or having difficulty concentrating. By showing how worry affects a character’s thoughts, words, and actions, you can give readers a deeper understanding of the character’s motivations and fears.

Plus, this attention to detail can help make the story more believable and realistic.

Show the Character’s Innermost Thoughts and Fears About Their Worry

When you’re writing about worry, it’s important to portray the character’s innermost thoughts and fears.

One way to do this is to use descriptive language.

For example, instead of simply saying, “ I’m worried about the upcoming exam ,” the person might say, “ I’m scared about the upcoming exam. What if I fail it? Then I’ll never graduate. ” This wording helps build a picture of the person’s emotional state and allows readers to empathize with their fears.

It’s also important to show how the person is dealing with her worries. Does she try to distract herself? Does she allow the worries to consume her? A person may deal with their worries in a variety of ways, such as excessive drinking, drug use, or long, hot showers.

By showing both the emotion itself and the character’s reaction to it, you can give readers a deeper understanding of what their worries feel like.

Body language can be a powerful way to show fear and anxiety. Shaking hands, for example, can convey a sense of fear or foreboding. Hunched shoulders, furrowed brows, pacing, and clenched fists are also signs of worry. A clenched jaw and teeth grinding are also signs of stress.

Inner monologs can reveal a person’s deepest fears and worries. Finally, thoughts about the future can show how a person’s worries affect their decisions.

One way to show a character’s innermost thoughts and fears is to have them keep a diary, as was done brilliantly in Bridget Jones’s Diary , for example.

Worry in the Eyes

When you’re writing about characters who’re worried, it can be helpful to describe their eyes. This is because the eyes are often a telltale sign of worry, stress, or anxiety.

For example, someone who’s worried may look around the room with wide eyes, trying to see all possible dangers.

Or the pupils may be dilated, making the eyes appear larger than usual.

Also, the person may blink more often than usual to prevent their eyes from drying out from stress.

Eyebrows may be drawn together and the skin between them may be wrinkled.

Another way to show worry is squinted eyes. This can convey suspicion or alertness as if the person is trying to assess a situation or a person.

With anxiety symptoms like this, you can help readers understand how the person is feeling and why they’re behaving in certain ways.

Worry in the Voice

One way to show that a character is worried is through their dialog. Concerned characters often speak quickly, use filler words, or stumble over their words as a vocal mirror of their negative thoughts.

You can also have them stumble over their words or hesitate in the middle of a sentence. Another way to show worry in the voice is to have the character’s pitch rise, either because they’re panicking or because they’re trying to sound more convincing.

Finally, you can make the character’s voice tremble or quiver as an anxious thought crosses their mind, which expresses both fear and uncertainty.

You Need the Backstory

It’s important that you know the backstory well in your writing process. This is because worry usually arises from some kind of conflict or problem.

To portray worry convincingly in your writing, you need to be able to show how the conflict or problem has affected your character.

- What’s at stake?

- What’s your character’s goal?

- And what’s she afraid of losing?

Here are some things to keep in mind as you flesh out the backstory of a character who’s worried:

- How did the conflict or problem arise?

- What’s the cause of the character’s stress?

- What’re the consequences of failure?

- What’s your character’s greatest fear?

Answering these questions will help you create a well-rounded and believable character who’s real concerns. If you know the backstory well, you can write about worry in a way that’s relatable and compelling.

What Worry Feels Like Inside

Here’s how someone might describe being worried:

Some days it’s hard to focus on anything but worry. It’s like a storm cloud hovering over your head, casting a shadow over everything else in your life.

When you worry, it feels like your mind is stuck in a loop of anxious thoughts. You feel tense and nervous, or you feel like you can’t focus on anything else. Your heart might be racing and you might start to sweat. You might even feel like you’re going to throw up or have a panic attack.

All of these physical symptoms can make it hard for you to think clearly or calm down. Worry can also affect your sleep, so you end up feeling not only anxious but exhausted.

Worry is all-consuming and can’t be shaken off. Your stomach is in knots and you can barely catch your breath.

Every little sound feels like it’s multiplying tenfold, and you can’t sit still. You pace back and forth, rock back and forth, or wrap your hair around your finger obsessively.

You might even start picking at your skin or biting your nails.

All you can think about is what could go wrong and how disastrous the consequences could be.

It can feel like your thoughts are spinning out of control. You may feel like you can’t turn your brain off.

It’s a stressful way to live, but it’s hard to see a way out when worry has such a tight grip on you.

Mastering Emotional Description Through Personal Insight

A crucial element in expressing emotions effectively in writing, such as conveying worry, lies in tapping into your emotional experiences. The best way to capture the essence of an emotion authentically is by understanding it intimately; one of the most effective methods to achieve this is through journaling. Regularly analyzing and articulating your feelings in a journal, you develop a deeper understanding and a more nuanced vocabulary for expressing emotions.

To assist you in this reflective practice, we recommend exploring “ Deep Journal Prompts ” from Brilliantio. These prompts are designed to guide you into a profound exploration of your emotional landscape, helping you articulate and understand complex feelings like worry, joy, frustration, and more. This deep self-exploration can significantly enhance your ability to describe these emotions in your writing.

Alternatively, for those looking to make journaling a consistent daily practice, “ 365 Journal Prompts ” offers a prompt for each day of the year, covering a wide range of emotions and scenarios. This can be an excellent way to ensure a varied and comprehensive exploration of your emotional experiences over time.

Incorporating these journaling practices into your routine not only aids in personal growth but also equips you with the tools to describe emotions more vividly and authentically in your writing.

How to Describe Fear in Writing (21 Best Tips + Examples)

The ability to evoke fear can heighten the tension in your narratives, making your characters more relatable and your stories more gripping.

But how do you do it?

Here’s how to describe fear in writing:

Describe fear in writing by understanding the type of fear, its intensity, and expressing it through body language, speech patterns, thoughts, feelings, setting, pace, and sensory description. Use metaphors, symbols, contrast, relatable fears, and personal experiences for a vivid portrayal.

In this guide, you’ll learn everything you need to know about how to describe fear in writing.

21 Elements to Describe Fear in Writing

Table of Contents

When writing about fear in stories or screenplays, there are 21 elements you need to consider.

Here is a list of those crucial elements of fear:

- Type of Fear

- Body Language

- Speech Patterns

- Use of Metaphors and Similes

- Sensory Description

- Relatability

- Anticipation

- The Unknown

- Personal Experiences

- Internal and External Conflict

- Character Development

- Word Choices

- Repercussions

Next, we’ll dive deeper into each element so that you fully understand what it is and how to apply it to your story.

Tip 1: Get to Know the Type of Fear

Understanding the type of fear your character is experiencing can make a huge difference in your writing.

Fear comes in various forms such as phobias, existential fear, traumatic fear, or even something as simple as a sudden surprise.

Knowing the difference will help you convey the emotion accurately and realistically.

Example: Fear of heights (acrophobia) would involve dizziness, a feeling of being unbalanced, and terror of looking down. On the other hand, existential fear, like the dread of death, would lead to more internal thoughts, panic, and a profound sense of despair.

Tip 2: Depict the Intensity

The intensity of fear varies from person to person and situation to situation.

Your character could be slightly uncomfortable, petrified, or somewhere in between.

Describing the intensity of the fear helps set the tone and mood for your scene.

Example: A mild unease could be something like, “There was a nagging sensation in the pit of her stomach.” As for absolute terror, try something like, “His heart pounded like a wild drum, every cell in his body screaming in terror.”

Tip 3: Use Body Language

Actions often tell more than words do.

Displaying your character’s fear through their body language can help your reader visualize the situation and empathize with the character’s feelings.

Example: A scared character might tremble, perspire excessively, or even exhibit signs of hyperventilation. “She stood frozen, her whole body shaking like a leaf in the wind, her breath coming out in short, ragged gasps.”

Tip 4: Alter Speech Patterns

Fear can greatly influence a person’s speech.

A scared character might stutter, ramble, or even lose the ability to speak entirely.

This can be an effective way to demonstrate their fear without explicitly stating it.

Example: “I-I don’t know w-what y-you’re talking about,” he stuttered, his voice barely above a whisper.”

Tip 5: Dive into Thoughts

A character’s thoughts provide insight into their mental state.

This can be a great tool for conveying fear, as it allows you to delve into their deepest insecurities and worries.

Example: “What if the car breaks down in the middle of nowhere? What if nobody finds me? What if this is the end?” His mind was a whirlwind of terrifying possibilities.

Tip 6: Express Feelings

Directly stating a character’s feelings can make the narrative more immediate and intense.

However, avoid overusing this method as it can become monotonous and lose impact.

Example: “A wave of fear washed over him, a fear so raw and powerful that it threatened to consume him whole.”

Tip 7: Use Metaphors and Similes

Metaphors and similes are useful tools to intensify your narrative and paint a vivid picture of fear in your reader’s mind.

Just be sure not to overuse them.

Instead, apply them strategically throughout your story when they can make the biggest impact.

Example: “His fear was a wild beast, unchecked and unfettered, tearing through the barriers of his mind.”

Tip 8: Control the Pace

When a character experiences fear, their perception of time can change.

Use pacing to mirror this altered perception.

Quick, short sentences can reflect a fast-paced scene of intense fear, while long, drawn-out sentences can portray a slow, creeping dread.

Example: “His heart raced. Sweat trickled down his brow. His hands shook. He was out of time.” Versus, “A dread, slow and cruel, crept up her spine, making every second feel like an eternity.”

Tip 9: Sensory Description

Involve the reader’s senses.

Make them hear the character’s thumping heart, feel their cold sweat, see their trembling hands.

The more sensory detail, the more immersive the experience.

Example: “The air turned frigid around him, his heart pounded in his ears, the acrid smell of fear filled his nostrils.”

Tip 10: Symbolism

Symbols can add depth to your story.

A symbol associated with fear can subconsciously create unease in your reader.

The smell of damp earth, the taste of fear-induced bile, or the touch of a cold wind can heighten your depiction of fear.

Example: A character may associate a certain perfume smell with a traumatic event, stirring fear every time they smell it.

Tip 11: Contrast

Adding a contrast between what a character expects and what actually happens can surprise both your character and reader, creating fear.

Additionally, such a contrast can throw a character off balance, making them more vulnerable.

This vulnerability can, in tandem, intensify the fear.

Example: A character walking into their home expecting a warm welcome, only to find a burglar instead.

Tip 12: Setting

A well-described setting can set the mood and increase the fear factor.

A dark alley, an abandoned house, or even a graveyard can make a scene scarier.

Consider, for instance, the prickling sensation of fear that crawls up your reader’s spine as your character walks down a gloomy, deserted alleyway.

Example: “The hallway was dimly lit, the floorboards creaked underfoot, and an eerie silence hung in the air.”

Tip 13: Timing

Timing is everything.

A sudden fright or a fear that gradually builds over time can significantly impact the level of fear.

Unexpected scares can send a jolt of fear, while prolonged dread can create a suspenseful horror.

Example: “As she turned the corner, a figure lunged at her” versus “She had the unsettling feeling of being watched for the past week.”

Tip 14: Relatability

Fear becomes more intense when it’s something your reader can relate to.

A fear of failure, of losing loved ones, or of public speaking can be quite effective.

Common fears such as public speaking, rejection, or loss can elicit a stronger emotional response.

Example: “The prospect of speaking in front of the crowd filled him with a fear so intense, it felt as though he was drowning.”

Tip 15: Anticipation

The fear of the unknown or the anticipation of something bad happening can be more terrifying than the event itself.

Plus, it creates suspense and holds the reader’s attention as they await the inevitable.

Example: “She waited for the results, her heart pounding in her chest. The fear of bad news was almost too much to bear.”

Tip 16: The Unknown

Fear of the unknown is a fundamental aspect of human nature.

Utilize this by keeping the source of fear hidden or unclear. In addition, this uncertainty can mirror the character’s feelings, drawing readers into their experience.

Example: “There was something in the room with him. He could hear it moving, but he couldn’t see it.”

Tip 17: Personal Experiences

Incorporating personal experiences into your narrative can make the fear feel more authentic.

It can also make writing the scene easier for you.

In fact, a scene drawn from your own fears can imbue your writing with raw, genuine emotion.

Example: “Just like when I was a child, the sight of the towering wave sent a ripple of terror through me.”

Tip 18: Internal and External Conflict

Fear can be used to create both internal (fear of failure, rejection) and external conflict (fear of a villain or natural disaster).

Importantly, fear can create a dilemma for your character, adding depth to their personality and complexity to your story.

“ Example: “His fear of disappointing his parents clashed with his fear of failing in his own ambitions.”

Tip 19: Character Development

Fear is a powerful motivator and can be a significant factor in character development.

It can cause a character to grow, reveal their true self, or even hold them back.

Moreover, how a character responds to fear can reveal their true nature or trigger growth, making them more nuanced and relatable.

Example: “Faced with his worst fear, he had two choices — to run and hide, or to fight. It was this moment that shaped him into the brave leader he would become.”

Tip 20: Word Choices

Choosing the right words can drastically alter the atmosphere of a scene.

Descriptive and emotive words can create a more palpable sense of fear. Descriptive and emotive words can help create a vivid, terrifying scene that lingers in your reader’s mind.

Example: “The eerie silence was shattered by a gut-wrenching scream.”

Tip 21: Repercussions

Fear often leads to consequences.

Showing the aftermath of fear — a character’s regret, relief, or trauma — can deepen your story’s impact.

Also, it allows for an exploration of the character’s coping mechanisms and resilience, adding another layer to their personality.

Example: “After the incident, every shadow made her jump, every noise made her heart race. Fear had left a lasting mark on her.”

Here is a video on how to describe fear in writing:

30 Words to Describe Fear

If you want to know how to describe fear in writing, you’ll need the right words:

Here is a list of good words to write about fear:

- Apprehensive

- Intimidated

- Creeped-out

- Trepidatious

30 Phrases to Describe Fear

Here are phrases to help you describe, fear, terror, and more in your writing:

- Paralyzed with fear

- Fear gripped her

- Heart pounding in terror

- Overcome with fright

- Sweating bullets

- Shaking like a leaf

- Frozen in fear

- Sick with dread

- A sinking feeling of fear

- Stomach tied in knots

- Hands trembling with fear

- Fear crawled up her spine

- Fear etched in his eyes

- Terror washed over her

- A cold sweat broke out

- Goosebumps of fear

- Fear stole his breath away

- Chilled to the bone

- The shadow of fear

- Consumed by fear

- Fear clenched at her heart

- Felt a wave of panic

- Heart raced with anxiety

- Fear prickled at the back of her neck

- Jumping at shadows

- Staring fear in the face

- Scream stuck in her throat

- Cornered by fear

- Sweat of fear

- A gust of terror

3 Full Fear Examples (3 Paragraphs)

Now, let’s look at three full examples of describing fear.

In the pit of her stomach, a sinking feeling of dread formed, icy tendrils of fear slithering into her veins.

Her heart pounded against her ribcage like a desperate prisoner, her breath hitched in her throat.

The alley was darker than she remembered, every shadow a potential threat.

The deafening silence, broken only by the distant hoot of an owl and her own shaky breaths, seemed to press against her eardrums. She was consumed by fear, every instinct screaming at her to run.

He stood petrified at the edge of the forest, the ominous blackness seeming to swallow up the faint moonlight.

Fear gripped him, a visceral entity that stole his breath and froze his blood.

The whispering wind through the trees sounded like ghostly warnings, making his skin prickle. He was acutely aware of his thundering heartbeat, the shaky dampness of his palms, the dryness in his mouth.

An unsettling shiver ran down his spine, and he knew without a shadow of doubt that stepping into the forest meant facing his worst nightmares.

Her hands shook as she held the envelope, her name written in a familiar scrawl.

An overwhelming sense of dread filled her as she slowly slid her finger under the seal, breaking it open.

The silence in the room was oppressive, the ticking of the clock deafening in its persistence.

She unfolded the letter, her eyes scanning the words written in haste. As she read, her fear gave way to a cold realization. Fear had been replaced by an emotion even worse – utter despair.

Final Thoughts: How to Describe Fear in Writing

Fear looks very different on different characters and in different stories.

The more specifically you create fear in your stories, often the better.

When you need to describe other things in your writing – from love to mountains and more – check out our other writing guides on this site.

Related Posts:

- How to Describe Love in Writing (21 Best Tips + Examples)

- How to Describe a Face in Writing (21 Best Tips + Examples)

- How To Describe a Panic Attack in Writing (Ultimate Guide)

- How to Describe Mountains in Writing (21 Tips & Examples)

The Biology of Fear (NIH)

For the love of Literature

How To Write A Realistic Panic Attack: 22 Tips With Written Examples.

For many writers, describing a situation or writing a scene they have no experience over is really hard. Many of them get the symptoms wrong, some get the details wrong and some have no idea what their character should be feeling. So, I devised a list to help anyone who is looking to write a realistic panic attack and has no idea how to describe it in your writings.

Panic attacks are involuntary reactions of your body to intense fear and distress. Its symptoms vary from person to person and there are no exact symptoms that are felt by everyone, however some common examples are nausea, dizziness, trouble breathing etc. Similarly, its triggers are also specific to the person having it and are diverse.

How to describe the triggers of a panic attack:

In order to describe a panic attack, you need to be aware of what can trigger a panic attack. Some of the common triggers you can use to write a realistic panic attack are:

- Death of a loved one

- Loss of a job

- Loss of a friend

- Stress from the parents

- Public humiliation

- Life-threatening situations

- Going on stage or in speaking in front of a crowd

These are the most common and intense example of what situations can cause a panic attack. However, more sensitive people can panic as a result of anything as small as an argument with their friends or not getting the top position in the class.

While writing your character, be sure how sensitive your character is before creating a trigger situation for him/her to panic.

How to write realistic symptoms of a panic attack:

Now we move on the task of describing a situation while our character is having a panic attack. Before writing the symptoms your character is feeling, remember that panic attacks occur suddenly.

- If your character gets a panic attack for the first time, he/she can easily confuse it with a heart attack and panic even more.

Writing example:

Marjorie felt like she was having a heart attack . Her breathing was labored and her palms felt sweating. She felt it would burst, her heart. She couldn’t think anything, only that her chest might get crushed any minute and her heart might burst open. “Oh lord”, she prayed, “just save me this once.”

- Panic attacks can cause un-triggered crying and hysterics.

- Some people shake uncontrollably while having a panic attack.

She wanted to text her mother back but she couldn’t. The news had made her sweaty. She was feeling like her life was running out of her. Her body felt so weak. Her fingers! She looked at them. They were shaking uncontrollably. Trying to catch her breath, she tried to type but to no avail. Her hands weren’t following her brain.

- Some people have cold sweats while panicking.

- Dry mouth or dry throat is also a sign that you are having a panic attack.

- Some people feel like their windpipe is clogged up while panicking.

She was trying to breathe but she couldn’t. Someone was clutching her throat, stopping her from taking full breaths. But there was no one, she was alone. Tears started trickling down her eyes as she realized this might be the end for her.

- Nausea and dizziness are often experienced during a panic attack.

- Heart rate picks up while someone is panicking.

She felt her heart beating seventy miles an hour, faster than that maybe. “Oh lord”, she thought to herself, “my heart is beating faster than a running cheetah.” She tried to think herself into humor but there was nothing humorous about the situation. What if her heart broke her ribcage?!

Since the symptoms are diverse, I have tried to mention the most common ones which are associated with a panic attack and will help the readers to grasp quickly what your character is going through.

How to describe a situation where someone is dealing with a person having a panic attack:

Dealing with people who are experiencing a panic attack is not easy, especially if you have had no history or previous knowledge about them. Your one small mistake might just infuriate the panicking person even more and increase the intensity of the attack. In order to write this situation correctly, you need to know the following things:

- Telling someone to calm down doesn’t help in panic attacks. It’s better to ask the person what they want you to do exactly to help them ease out.

So while describing the panic attack in your writing you can go something like:

Ava cared about her friend Marjorie. And Ava had seen many panic attacks of her own over the years. She knew she had to be calm for her friend. So she asked Marjorie whose eyes were bloodshot now, calmly, “What would you like me to do for you?”

- Diverting the attention to something else can help the person calm down. You can either talk about stuff they like or ask them questions to keep them engaged. They may have a hard time answer but eventually, their brain will start focusing on answering the question and they will calm down.

- Make the person having a panic attack breathe in their fists.

“Good, now make a fist”, she told Marjorie. She saw her do as told, though shakily. Good, her friend was listening at least. “Now breathe in”, she performed an inward motion with her hands. “And out,” she breathed out with Marjorie.

- Counting backwards can engage your brain and stop the panic attack very soon so whichever character is dealing with the panic attack can make your character count backwards with him/her.

Some other facts about panic attacks you can use:

These are a few other facts that can be used while describing a panic attack. They can be used to create well-crafted scenes of panic attacks that readers who get them can actually relate to.

- People who get panic attacks run from public gatherings if they feel like getting them. It’s a shame for them to get it in front of their friends and family mostly.

Marjorie felt like she would panic. She didn’t want to do it in public, especially not in front of her new friends. They would never understand. She knew she had to get out of there fast. Or everyone will just make fun of her.

- Panic attacks can’t be controlled.

Angela asked her to control it. “Marjorie”, she said, “this is a big moment. You can’t ruin it by panicking right now. Think of me, okay. Please. Do it for me.”

Marjorie wanted to. Angela didn’t know how much she wanted to. But of course, she couldn’t. She had no control over it whatsoever.

So this is it! Now go on and write that scene of yours. It’s time to impress your readers.

If you like to add in anything that will help the readers describe a panic attack realistically, just comment below and I’ll see whether it needs to be added.

You may also like How to Overcome Writer’s Block by just reading if you are having trouble writing.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

2 thoughts on “ How To Write A Realistic Panic Attack: 22 Tips With Written Examples. ”

This was so helpful, Thank you!!!!

I was looking for how to show anxiety (besides the thoughts going around in circles) this is insanely good, thank you! You know, that must have been a panic attack those years ago I was over stressed and this crushing pain in my chest on the left side that went in my shoulder, and it hurt so much I started to shake. You really do think you’re having a heart attack!

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Fearful Whispers: Crafting Descriptions of Fear in Creative Writing

My name is Debbie, and I am passionate about developing a love for the written word and planting a seed that will grow into a powerful voice that can inspire many.

Have you ever found yourself so immersed in a chilling novel that you couldn’t help but feel a shiver crawl up your spine? Or stumbled upon a short story that left you with a lingering sense of unease long after you closed its pages? It’s the power of fear, intricately woven within the tapestry of the written word, that has the ability to captivate readers and keep them yearning for more. Crafting descriptions of fear is an art that takes both finesse and creativity, allowing writers to summon emotions that stimulate the senses and send our imaginations into overdrive. In this article, we’ll explore the intricacies of fear-inspired writing, diving deep into the realm of fearful whispers, and uncovering the secrets to crafting spine-chilling descriptions that will haunt your readers long after they’ve put down your work. So, grab your pens and prepare to delve into the chilling labyrinth of fear that lies within creative writing.

– Understanding the Power of Fear in Creative Writing

Understanding the power of fear in creative writing, physical sensations:, – crafting vivid imagery: describing fearful environments and atmospheres, – tapping into the senses: painting fear through descriptive language, – portraying fear through characters: facial expressions, body language, and dialogue, – utilizing narrative techniques: building suspense and tension in fearful moments, utilizing narrative techniques: building suspense and tension in fearful moments, – transforming fear into art: balancing descriptions and reader imagination, – mastering the art of fear: tips and tricks for conveying authentic emotions, mastering the art of fear: tips and tricks for conveying authentic emotions, frequently asked questions, insights and conclusions.

When it comes to creative writing, fear is a force that holds incredible power. It has the ability to captivate readers, ignite their imaginations, and keep them on the edge of their seats. Fear is a powerful emotion that can be harnessed to create intense and memorable stories. Here’s a closer look at why fear is such a potent tool in the world of creative writing: