- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Key Concepts

- The View From Here

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish?

- About ELT Journal

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Age and the critical period hypothesis

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Christian Abello-Contesse, Age and the critical period hypothesis, ELT Journal , Volume 63, Issue 2, April 2009, Pages 170–172, https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccn072

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In the field of second language acquisition (SLA), how specific aspects of learning a non-native language (L2) may be affected by when the process begins is referred to as the ‘age factor’. Because of the way age intersects with a range of social, affective, educational, and experiential variables, clarifying its relationship with learning rate and/or success is a major challenge.

There is a popular belief that children as L2 learners are ‘superior’ to adults ( Scovel 2000 ), that is, the younger the learner, the quicker the learning process and the better the outcomes. Nevertheless, a closer examination of the ways in which age combines with other variables reveals a more complex picture, with both favourable and unfavourable age-related differences being associated with early- and late-starting L2 learners ( Johnstone 2002 ).

The ‘critical period hypothesis’ (CPH) is a particularly relevant case in point. This is the claim that there is, indeed, an optimal period for language acquisition, ending at puberty. However, in its original formulation ( Lenneberg 1967 ), evidence for its existence was based on the relearning of impaired L1 skills, rather than the learning of a second language under normal circumstances.

Furthermore, although the age factor is an uncontroversial research variable extending from birth to death ( Cook 1995 ), and the CPH is a narrowly focused proposal subject to recurrent debate, ironically, it is the latter that tends to dominate SLA discussions ( García Lecumberri and Gallardo 2003 ), resulting in a number of competing conceptualizations. Thus, in the current literature on the subject ( Bialystok 1997 ; Richards and Schmidt 2002 ; Abello-Contesse et al. 2006), references can be found to (i) multiple critical periods (each based on a specific language component, such as age six for L2 phonology), (ii) the non-existence of one or more critical periods for L2 versus L1 acquisition, (iii) a ‘sensitive’ yet not ‘critical’ period, and (iv) a gradual and continual decline from childhood to adulthood.

It therefore needs to be recognized that there is a marked contrast between the CPH as an issue of continuing dispute in SLA, on the one hand, and, on the other, the popular view that it is an invariable ‘law’, equally applicable to any L2 acquisition context or situation. In fact, research indicates that age effects of all kinds depend largely on the actual opportunities for learning which are available within overall contexts of L2 acquisition and particular learning situations, notably the extent to which initial exposure is substantial and sustained ( Lightbown 2000 ).

Thus, most classroom-based studies have shown not only a lack of direct correlation between an earlier start and more successful/rapid L2 development but also a strong tendency for older children and teenagers to be more efficient learners. For example, in research conducted in the context of conventional school programmes, Cenoz (2003) and Muñoz (2006) have shown that learners whose exposure to the L2 began at age 11 consistently displayed higher levels of proficiency than those for whom it began at 4 or 8. Furthermore, comparable limitations have been reported for young learners in school settings involving innovative, immersion-type programmes, where exposure to the target language is significantly increased through subject-matter teaching in the L2 ( Genesee 1992 ; Abello-Contesse 2006 ). In sum, as Harley and Wang (1997) have argued, more mature learners are usually capable of making faster initial progress in acquiring the grammatical and lexical components of an L2 due to their higher level of cognitive development and greater analytical abilities.

In terms of language pedagogy, it can therefore be concluded that (i) there is no single ‘magic’ age for L2 learning, (ii) both older and younger learners are able to achieve advanced levels of proficiency in an L2, and (iii) the general and specific characteristics of the learning environment are also likely to be variables of equal or greater importance.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1477-4526

- Print ISSN 0951-0893

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Critical Period In Brain Development and Childhood Learning

Charlotte Nickerson

Research Assistant at Harvard University

Undergraduate at Harvard University

Charlotte Nickerson is a student at Harvard University obsessed with the intersection of mental health, productivity, and design.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Key Takeaways

- Critical period is an ethological term that refers to a fixed and crucial time during the early development of an organism when it can learn things that are essential to survival. These influences impact the development of processes such as hearing and vision, social bonding, and language learning.

- The term is most often experienced in the study of imprinting, where it is thought that young birds could only develop an attachment to the mother during a fixed time soon after hatching.

- Neurologically, critical periods are marked by high levels of plasticity in the brain before neural connections become more solidified and stable. In particular, critical periods tend to end when synapses that inhibit the neurotransmitter GABA mature.

- In contrast to critical periods, sensitive periods, otherwise known as “weak critical periods,” happen when an organism is more sensitive than usual to outside factors influencing behavior, but this influence is not necessarily restricted to the sensitive period.

- Scholars have debated the extent to which older organisms can develop certain skills, such as natively-accented foreign languages, after the critical period.

The critical period is a biologically determined stage of development where an organism is optimally ready to acquire some pattern of behavior that is part of typical development. This period, by definition, will not recur at a later stage.

If an organism does not receive exposure to the appropriate stimulus needed to learn a skill during a critical period, it may be difficult or even impossible for that organism to develop certain functions associated with that skill later in life.

This happens because a range of functional and structural elements prevent passive experiences from eliciting significant changes in the brain (Cisneros-Franco et al., 2020).

The first strong proponent of the theory of critical periods was Charles Stockhard (1921), a biologist who attempted to experiment with the effects of various chemicals on the development of fish embryos, though he gave credit to Dareste for originating the idea 30 years earlier (Scott, 1962).

Stockhard’s experiments showed that applying almost any chemical to fish embryos at a certain stage of development would result in one-eyed fish.

These experiments established that the most rapidly growing tissues in an embryo are the most sensitive to any change in conditions, leading to effects later in development (Scott, 1962).

Meanwhile, psychologist Sigmund Freud attempted to explain the origins of neurosis in human patients as the result of early experiences, implying that infants are particularly sensitive to influences at certain points in their lives.

Lorenz (1935) later emphasized the importance of critical periods in the formation of primary social bonds (otherwise known as imprinting) in birds, remarking that this psychological imprinting was similar to critical periods in the development of the embryo.

Soon thereafter, McGraw (1946) pointed out the existence of critical periods for the optimal learning of motor skills in human infants (Scott, 1962).

Example: Infant-Parent Attachment

The concept of critical or sensitive periods can also be found in the domain of social development, for example, in the formation of the infant-parent attachment relationship (Salkind, 2005).

Attachment describes the strong emotional ties between the infant and caregiver, a reciprocal relationship developing over the first year of the child’s life and particularly during the second six months of the first year.

During this attachment period , the infant’s social behavior becomes increasingly focused on the principal caregivers (Salkind, 2005).

The 20th-century English psychiatrist John Bowlby formulated and presented a comprehensive theory of attachment influenced by evolutionary theory.

Bowlby argued that the infant-parent attachment relationship develops because it is important to the survival of the infant and that the period from six to twenty-four months of age is a critical period of attachment.

This coincides with an infant’s increasing tendency to approach familiar caregivers and to be wary of unfamiliar adults. After this critical period, it is still possible for a first attachment relationship to develop, albeit with greater difficulty (Salkind, 2005).

This has brought into question, in a similar vein to language development, whether there is actually a critical development period for infant-caregiver attachment.

Sources debating this issue typically include cases of infants who did not experience consistent caregiving due to being raised in institutions prior to adoption (Salkind, 2005).

Early research into the critical period of attachment, published in the 1940s, reports consistently that children raised in orphanages subsequently showed unusual and maladaptive patterns of social behavior, difficulty in forming close relationships, and being indiscriminately friendly toward unfamiliar adults (Salkind, 2005).

Later, research from the 1990s indicated that adoptees were actually still able to form attachment relationships after the first year of life and also made developmental progress following adoption.

Nonetheless, these children had an overall increased risk of insecure or maladaptive attachment relationships with their adoptive parents. This evidence supports the notion of a sensitive period, but not a critical period, in the development of first attachment relationships (Salkind, 2005).

Mechanisms for Critical Periods

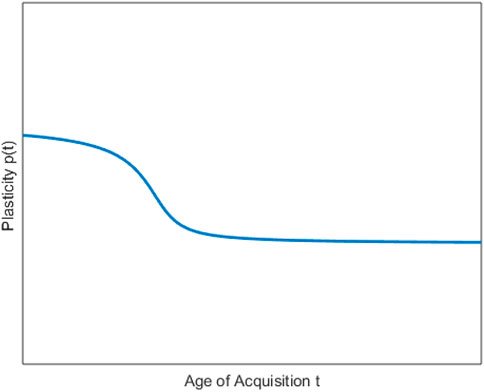

Both genetics and sensory experiences from outside the body shape the brain as it develops (Knudsen, 2004). However, the developmental stage that an organism is in significantly impacts how much the brain can change based on these experiences.

In scientific terms, the brain’s plasticity changes over the course of a lifespan. The brain is very plastic in the early stages of life before many key connections take root, but less so later.

This is why researchers have shown that early experience is crucial for the development of, say, language and musical abilities, and these skills are more challenging to take up in adulthood (Skoe and Kraus, 2013; White et al., 2013; Hartshorne et al., 2018).

As brains mature, the connections in them become more fixed. The brain’s transitions from a more plastic to a more fixed state advantageously allow it to retain new and complex processes, such as perceptual, motor, and cognitive functions (Piaget, 1962).

Children’s gestures, for example, pride and predict how they will acquire oral language skills (Colonnesi et al., 2010), which in turn are important for developing executive functions (Marcovitch and Zelazo, 2009).

However, this formation of stable connections in the brain can limit how the brain’s neural circuitry can be revised in the future. For example, if a young organism has abnormal sensory experiences during the critical period – such as auditory or visual deprivation – the brain may not wire itself in a way that processes future sensory inputs properly (Gallagher et al., 2020).

One illustration of this is the timing of cochlear implants – a prosthesis that restores hearing in some deaf people. Children who receive cochlear implants before two years of age are more likely to benefit from them than those who are implanted later in life (Kral and Eggermont, 2007; Gallagher et al., 2020).

Similarly, the visual deprivation caused by cataracts in infants can cause similar consequences. When cataracts are removed during early infancy, individuals can develop relatively normal vision; however, when the cataracts are not removed until adulthood, this results in substantially poorer vision (Martins Rosa et al., 2013).

After the critical period closes, abnormal sensory experiences have a less drastic effect on the brain and lead to – barring direct damage to the central nervous system – reversible changes (Gallagher et al., 2020). Much of what scientists know about critical periods derives from animal studies , as these allow researchers greater control over the variables that they are testing.

This research has found that different sensory systems, such as vision, auditory processing, and spatial hearing, have different critical periods (Gallagher et al., 2020).

The brain regulates when critical periods open and close by regulating how much the brain’s synapses take up neurotransmitters , which are chemical substances that affect the transmission of electrical signals between neurons.

In particular, over time, synapses decrease their uptake of gamma-aminobutyric acid, better known as GABA. At the beginning of the critical period, outside sources become more effective at influencing changes and growth in the brain.

Meanwhile, as the inhibitory circuits of the brain mature, the mature brain becomes less sensitive to sensory experiences (Gallagher et al., 2020).

Critical Periods vs Sensitive Periods

Critical periods are similar to sensitive periods, and scholars have, at times, used them interchangeably. However, they describe distinct but overlapping developmental processes.

A sensitive period is a developmental stage where sensory experiences have a greater impact on behavioral and brain development than usual; however, this influence is not exclusive to this time period (Knudsen, 2004; Gallagher, 2020). These sensitive periods are important for skills such as learning a language or instrument.

In contrast, A critical period is a special type of sensitive period – a window where sensory experience is necessary to shape the neural circuits involved in basic sensory processing, and when this window opens and closes is well-defined (Gallagher, 2020).

Researchers also refer to sensitive periods as weak critical periods. Some examples of strong critical periods include the development of vision and hearing, while weak critical periods include phenome tuning – how children learn how to organize sounds in a language, grammar processing, vocabulary acquisition, musical training, and sports training (Gallagher et al., 2020).

Critical Period Hypothesis

One of the most notable applications of the concept of a critical period is in linguistics. Scholars usually trace the origins of the debate around age in language acquisition to Penfield and Robert’s (2014) book Speech and Brain Mechanisms.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Penfield was a staunch advocate of early immersion education (Kroll and De Groot, 2009). Nonetheless, it was Lenneberg, in his book Biological Foundations of Language, who coined the term critical period (1967) in describing the language period.

Lennenberg (1967) described a critical period as a period of automatic acquisition from mere exposure” that “seems to disappear after this age.” Scovel (1969) later summarized and narrowed Penfield’s and Lenneberg’s view on the critical period hypothesis into three main claims:

- Adult native speakers can identify non-natives by their accents immediately and accurately.

- The loss of brain plasticity at about the age of puberty accounts for the emergence of foreign accents./li>

- The critical period hypothesis only holds for speech (whether or not someone has a native accent) and does not affect other areas of linguistic competence.

Linguists have since attempted to find evidence for whether or not scientific evidence actually supports the critical period hypothesis, if there is a critical period for acquiring accentless speech, for “morphosyntactic” competence, and if these are true, how age-related differences can be explained on the neurological level (Scovel, 2000).

The critical period hypothesis applies to both first and second-language learning. Until recently, research around the critical period’s role in first language acquisition revolved around findings about so-called “feral” children who had failed to acquire language at an older age after having been deprived of normal input during the critical period.

However, these case studies did not account for the extent to which social deprivation, and possibly food deprivation or sensory deprivation, may have confounded with language input deprivation (Kroll and De Groot, 2009).

More recently, researchers have focused more systematically on deaf children born to hearing parents who are therefore deprived of language input until at least elementary school.

These studies have found the effects of lack of language input without extreme social deprivation: the older the age of exposure to sign language is, the worse its ultimate attainment (Emmorey, Bellugi, Friederici, and Horn, 1995; Kroll and De Groot, 2009).

However, Kroll and De Groot argue that the critical period hypothesis does not apply to the rate of acquisition of language. Adults and adolescents can learn languages at the same rate or even faster than children in their initial stage of acquisition (Slavoff and Johnson, 1995).

However, adults tend to have a more limited ultimate attainment of language ability (Kroll and De Groot, 2009).

There has been a long lineage of empirical findings around the age of acquisition. The most fundamental of this research comes from a series of studies since the late 1970s documenting a negative correlation between age of acquisition and ultimate language mastery (Kroll and De Grott, 2009).

Nonetheless, different periods correspond to sensitivity to different aspects of language. For example, shortly after birth, infants can perceive and discriminate speech sounds from any language, including ones they have not been exposed to (Eimas et al., 1971; Gallagher et al., 2020).

Around six months of age, exposure to the primary language in the infant’s environment guides phonetic representations of language and, subsequently, the neural representations of speech sounds of the native language while weakening those of unused sounds (McClelland et al., 1999; Gallagher et al., 2020).

Vocabulary learning experiences rapid growth at about 18 months of age (Kuhl, 2010).

Critical Evaluation

More than any other area of applied linguistics, the critical period hypothesis has impacted how teachers teach languages. Consequently, researchers have critiqued how important the critical period is to language learning.

For example, several studies in early language acquisition research showed that children were not necessarily superior to older learners in acquiring a second language, even in the area of pronunciation (Olson and Samuels, 1973; Snow and Hoefnagel-Hohle, 1978; Scovel, 2000).

In fact, the majority of researchers at the time appeared to be skeptical about the existence of a critical period, with some explicitly denying its existence.

Counter to one of the primary tenets of Scovel’s (1969) critical period hypothesis, there have been several cases of people who have acquired a second language in adulthood speaking with native accents.

For example, Moyer’s study of highly proficient English-speaking learners of German suggested that at least one of the participants was judged to have native-like pronunciation in his second language (1999), and several participants in Bongaerts (1999) study of highly proficient Dutch speakers of French spoke with accents judged to be native (Scovel, 2000).

Bongaerts, T. (1999). Ultimate attainment in L2 pronunciation: The case of very advanced late L2 learners. Second language acquisition and the critical period hypothesis, 133-159.

Cisneros-Franco, J. M., Voss, P., Thomas, M. E., & de Villers-Sidani, E. (2020). Critical periods of brain development. In Handbook of Clinical Neurolog y (Vol. 173, pp. 75-88). Elsevier.

Colonnesi, C., Stams, G. J. J., Koster, I., & Noom, M. J. (2010). The relation between pointing and language development: A meta-analysis. Developmental Review, 30 (4), 352-366.

Eimas, P. D., Siqueland, E. R., Jusczyk, P., & Vigorito, J. (1971). Speech perception in infants. Science, 171 (3968), 303-306.

Emmorey, K., Bellugi, U., Friederici, A., & Horn, P. (1995). Effects of age of acquisition on grammatical sensitivity: Evidence from on-line and off-line tasks. Applied Psycholinguistics, 16 (1), 1-23.

Knudsen, E. I. (2004). Sensitive periods in the development of the brain and behavior. Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 16 (8), 1412-1425.

Hartshorne, J. K., Tenenbaum, J. B., & Pinker, S. (2018). A critical period for second language acquisition: Evidence from 2/3 million English speakers. Cognition, 177 , 263-277.

Kral, A., & Eggermont, J. J. (2007). What’s to lose and what’s to learn: development under auditory deprivation, cochlear implants and limits of cortical plasticity. Brain Research Reviews, 56(1), 259-269.

Kroll, J. F., & De Groot, A. M. (Eds.). (2009). Handbook of bilingualism: Psycholinguistic approaches . Oxford University Press.

Kuhl, P. K. (2010). Brain mechanisms in early language acquisition. Neuron, 67 (5), 713-727.

Lenneberg, E. H. (1967). The biological foundations of language. Hospital Practice, 2( 12), 59-67.

Lorenz, K. (1935). Der kumpan in der umwelt des vogels. Journal für Ornithologie, 83 (2), 137-213.

Marcovitch, S., & Zelazo, P. D. (2009). A hierarchical competing systems model of the emergence and early development of executive function. Developmental science, 12 (1), 1-18.

McClelland, J. L., Thomas, A. G., McCandliss, B. D., & Fiez, J. A. (1999). Understanding failures of learning: Hebbian learning, competition for representational space, and some preliminary experimental data. Progress in brain research, 121, 75-80.

McGraw, M. B. (1946). Maturation of behavior. In Manual of child psychology. (pp. 332-369). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Moyer, A. (1999). Ultimate attainment in L2 phonology: The critical factors of age, motivation, and instruction. Studies in second language acquisition, 21 (1), 81-108.

Gallagher, A., Bulteau, C., Cohen, D., & Michaud, J. L. (2019). Neurocognitive Development: Normative Development. Elsevier.

Olson, L. L., & Jay Samuels, S. (1973). The relationship between age and accuracy of foreign language pronunciation. The Journal of Educational Research, 66 (6), 263-268.

Penfield, W., & Roberts, L. (2014). Speech and brain mechanisms. Princeton University Press.

Piaget, J. (1962). The stages of the intellectual development of the child. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 26 (3), 120.

Rosa, A. M., Silva, M. F., Ferreira, S., Murta, J., & Castelo-Branco, M. (2013). Plasticity in the human visual cortex: an ophthalmology-based perspective. BioMed research international, 2013.

Salkind, N. J. (Ed.). (2005). Encyclopedia of human development . Sage Publications.

Scott, J. P. (1962). Critical periods in behavioral development. Science, 138 (3544), 949-958.

Scovel, T. (1969). Foreign accents, language acquisition, and cerebral dominance 1. Language learning, 19 (3‐4), 245-253.

Scovel, T. (2000). A critical review of the critical period research. Annual review of applied linguistics, 20 , 213-223.

Skoe, E., & Kraus, N. (2013). Musical training heightens auditory brainstem function during sensitive periods in development. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 622.

Slavoff, G. R., & Johnson, J. S. (1995). The effects of age on the rate of learning a second language. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 17 (1), 1-16.

Snow, C. E., & Hoefnagel-Höhle, M. (1978). The critical period for language acquisition: Evidence from second language learning. Child development, 1114-1128.

Stockard, C. R. (1921). Developmental rate and structural expression: an experimental study of twins,‘double monsters’ and single deformities, and the interaction among embryonic organs during their origin and development. American Journal of Anatomy, 28 (2), 115-277.

White, E. J., Hutka, S. A., Williams, L. J., & Moreno, S. (2013). Learning, neural plasticity and sensitive periods: implications for language acquisition, music training and transfer across the lifespan. Frontiers in systems neuroscience, 7, 90.

Further Information

Related Articles

Child Psychology

Vygotsky vs. Piaget: A Paradigm Shift

Interactional Synchrony

Internal Working Models of Attachment

Learning Theory of Attachment

Stages of Attachment Identified by John Bowlby And Schaffer & Emerson (1964)

Child Psychology , Personality

How Anxious Ambivalent Attachment Develops in Children

- Professional development

- Knowing the subject

- Teaching Knowledge database A-C

Critical period hypothesis

The critical period hypothesis says that there is a period of growth in which full native competence is possible when acquiring a language. This period is from early childhood to adolescence.

The critical period hypothesis has implications for teachers and learning programmes, but it is not universally accepted. Acquisition theories say that adults do not acquire languages as well as children because of external and internal factors, not because of a lack of ability.

Example Older learners rarely achieve a near-native accent. Many people suggest this is due to them being beyond the critical period.

In the classroom A problem arising from the differences between younger learners and adults is that adults believe that they cannot learn languages well. Teachers can help learners with this belief in various ways, for example, by talking about the learning process and learning styles, helping set realistic goals, choosing suitable methodologies, and addressing the emotional needs of the adult learner.

Further links:

https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/how-maximise-language-learning-senior-learners

https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/how-much-do-your-learners-use-english-outside-classroom

Research and insight

Browse fascinating case studies, research papers, publications and books by researchers and ELT experts from around the world.

See our publications, research and insight

Critical Period

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2021

- pp 1588–1590

- Cite this reference work entry

- Yan Wang 3 &

- Jing Guo 3

231 Accesses

Crucial time ; Sensitive period

A maturational stage during the lifespan of an organism in which the organism’s nervous system is especially sensitive to certain environmental stimuli. The organism is more sensitive to environmental stimulation during a critical period than at other times during its life.

Introduction

The phenomenon of critical period was first described by William James ( 1899 ) as “the transitoriness of instincts.” The term “critical period” was proposed by the Austrian ecologist based on his observations that newly hatched poultries, such as chicks and geese, would follow the object, usually their mother, if exposed to within a certain short time after birth.

According to Lorenz, if the young animal was not exposed to the particular stimulus during the “critical period” to learn a given skill or trait, it would become extremely struggling to develop particular behavioral pattern in the later life.

A vast of existing literature has identified the...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Belsky, J., Schlomer, G. L., & Ellis, B. J. (2012). Beyond cumulative risk: Distinguishing harshness and unpredictability as determinants of parenting and early life history strategy. Developmental Psychology, 48 , 662–673.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bowlby, J. (1951). Maternal care and mental health . Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 3, 1–63.

Google Scholar

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. Vol. 1. Attachment . New York: Basic Books.

Doom, J. R., Vanzomeren-Dohm, A. A., & Simpson, J. A. (2016). Early unpredictability predicts increased adolescent externalizing behaviors and substance use: A life history perspective. Development and Psychopathology, 28 , 1505–1516.

Ellis, B. J. (2004). Timing of pubertal maturation in girls: An integrated life history approach. Psychological Bulletin, 130 , 920–958.

Ellis, B. J., & Del Giudice, M. (2014). Beyond allostatic load: Rethinking the role of stress in regulating human development. Developmental and Psychopathology, 26 , 1–20.

Article Google Scholar

Friedmann, N., & Rusou, D. (2015). Critical period for first language: The crucial role of language input during the first year of life. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 35 , 27–34.

Granena, G., & Long, M. H. (2014). Age of onset, length of residence, language aptitude and ultimate L2 attainment in three linguistic domains. Second Language Research, 29 (3), 311–343.

Hubel, D. H., & Wiesel, T. N. (1962). Receptive fields, binocular interaction and functional architecture in the cat’s visual cortex. The Journal of Physiology, 160 (45), 106–154.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hurford, J. R. (1991). The evolution of the critical period for language acquisition. Cognition, 40 (3), 159–201.

James, W. (1899). Talks to teachers on psychology: And to students on some of life’s ideals . Dover Publications 2001. ISBN 0-486-41964-9.

Simpson, J. A., Griskevicius, V., Kuo, A. I.-C., Sung, S., & Collins, W. A. (2012). Evolution, stress and sensitive periods: The influence of unpredictability in early versus late childhood on sex and risky behavior. Developmental Psychology, 48 (3), 674–686.

Susman, E. J. (2006). Psychobiology of persistent antisocial behavior: Stress, early vulnerabilities and the attenuation hypothesis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 30 , 376–389.

Vanhove, J. (2013). Critical evidence: A test of the critical-period hypothesis for second-language acquisition. Psychological Science, 14 (1), 31–38.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Fudan University, Shanghai, China

Yan Wang & Jing Guo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yan Wang .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Oakland University, Rochester, MI, USA

Todd K Shackelford

Viviana A Weekes-Shackelford

Section Editor information

University of Nicosia, Nicosia, Cyprus

Menelaos Apostolou

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Wang, Y., Guo, J. (2021). Critical Period. In: Shackelford, T.K., Weekes-Shackelford, V.A. (eds) Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19650-3_1060

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19650-3_1060

Published : 22 April 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-19649-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-19650-3

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Find Study Materials for

- Explanations

- Business Studies

- Combined Science

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- English literature

- Environmental Science

- Human Geography

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Social Studies

- Browse all subjects

- Textbook Solutions

- Read our Magazine

Create Study Materials

- Flashcards Create and find the best flashcards.

- Notes Create notes faster than ever before.

- Study Sets Everything you need for your studies in one place.

- Study Plans Stop procrastinating with our smart planner features.

- Critical Period

Many of us are exposed to language from birth and we seem to acquire it without even thinking. But what would happen if we were deprived of communication from birth? Would we still acquire language?

Create learning materials about Critical Period with our free learning app!

- Instand access to millions of learning materials

- Flashcards, notes, mock-exams and more

- Everything you need to ace your exams

- 5 Paragraph Essay

- Argumentative Essay

- Cues and Conventions

- English Grammar

- English Language Study

- Essay Prompts

- Essay Writing Skills

- Global English

- History of English Language

- International English

- Key Concepts in Language and Linguistics

- Language Acquisition

- Agrammatism

- Behavioral Theory

- Cognitive Theory

- Constructivism

- Developmental Language Disorder

- Down Syndrome Language

- Functional Basis of Language

- Interactionist Theory

- Language Acquisition Device (LAD)

- Language Acquisition Support System

- Language Acquisition in Children

- Michael Halliday

- Multiword Stage

- One-Word stage

- Specific Language Impairments

- Theories of Language Acquisition

- Two-Word Stage

- Williams Syndrome

- Language Analysis

- Language and Social Groups

- Lexis and Semantics

- Linguistic Terms

- Listening and Speaking

- Multiple Choice Questions

- Research and Composition

- Rhetorical Analysis Essay

- Single Paragraph Essay

- Sociolinguistics

- Summary Text

- Synthesis Essay

- Textual Analysis

The Critical Period Hypothesis states that we would not be able to develop language to a fluent level if we are not exposed to it in the first few years of our lives. Let's have a look at this concept in more detail!

Critical period hypothesis

The Critical Period Hypothesis (CPH) holds that there is a critical time period for a person to learn a new language to a native proficiency. This critical period typically starts at around age two and ends before puberty¹. The hypothesis implies that acquiring a new language after this critical window will be more difficult and less successful.

Critical period in Psychology

The critical period is a key concept within the subject of Psychology. Psychology often has close links with English Language and Linguistics with a key area of study being Language Acquisition .

Critical period Psychology definition

In developmental psychology, the critical period is the maturing stage of a person, where their nervous system is primed and sensitive to environmental experiences. If a person doesn't get the right environmental stimuli during this period, their ability to learn new skills will weaken, affecting many social functions in adult life. If a child passes through a critical period without learning a language, it will be very unlikely for them to gain native fluency in their first language².

During the critical period, a person is primed to acquire new skills because of the brains' neuroplasticity. The connections in the brain, called synapses, are highly receptive to new experiences since they can form new pathways. The developing brain has a high degree of plasticity and gradually becomes less 'plastic' in adulthood.

Critical and sensitive periods

Similar to the critical period, researchers use another term called the 'sensitive period' or 'weak critical period'. The sensitive period is similar to the critical period since it's characterized as a time in which the brain has a high level of neuroplasticity and is quick to form new synapses. The main difference is that the sensitive period is considered to last for a longer time beyond puberty, but the boundaries are not strictly set.

First language acquisition in the critical period

It was Eric Lenneberg in his book Biological Foundations of Language (1967), who first introduced the Critical Period Hypothesis concerning language acquisition. He proposed that learning a language with high-level proficiency can only happen within this period. L anguage acquisition outside of this period is more challenging, making it less likely to achieve native proficiency.

He proposed this hypothesis based on evidence from children with certain childhood experiences that affected their first language ability. More specifically, the evidence was based on these cases:

Deaf children that didn't develop native proficiency in verbal language after puberty .

Children that experienced brain injury had better recovery prospects than adults. It is more likely for children with aphasia to learn a language than it is for adults with aphasia.

Children who were victims of child abuse during early childhood had more difficulties learning the language since they were not exposed to it during the critical period.

Critical period example

An example of the critical period is Genie. Genie, the so-called 'feral child', is a key case study in regard to the critical period and language acquisition.

As a child, Genie was a victim of domestic abuse and social isolation. T his took place from the age of 20 months until 13 years old. During this period, she didn't speak to anyone and rarely had any interaction with other people. This meant that she wasn't able to develop adequate language skills.

When authorities discovered her, she could not speak. Over a few months, she acquired some language skills with direct teaching but the process was quite slow. Although her vocabulary grew over time, she had difficulty learning basic grammar and maintaining conversations.

The scientists that worked with her concluded that because she wasn't able to learn a language during the critical period, she wouldn't be able to achieve full competency in language for the rest of her life. Although she made clear improvements in her ability to speak, her speech still had a lot of abnormalities, and she had difficulty with social interaction .

The case of Genie supports Lenneberg 's theory to an extent. However, academics and researchers still argue about this topic. Some scientists claim that Genie's development was disrupted because of the inhumane and traumatic treatment she suffered as a child, which caused her inability to learn a language.

Second language acquisition in the critical period

The Critical Period Hypothesis can be applied in the context of second language acquisition. It applies to adults or children who have fluency in their first language and try to learn a second language.

The main point of evidence given for the CPH for second language acquisition is assessing older learners' ability to grasp a second language compared to children and adolescents. A general trend that can be observed is that younger learners grasp a complete command over the language compared to their older counterparts³.

Although there may be examples where adults achieve very good proficiency in a new language, they usually retain a foreign accent which isn't common with younger learners. Retaining a foreign accent is usually because of the function that the neuromuscular system plays in the pronunciation of speech.

Adults are unlikely to attain a native accent since they are beyond the critical period to learn new neuromuscular functions. With all this being said, there are special cases of adults who achieve near-native proficiency in all aspects of a second language. For this reason, researchers have found it tricky to distinguish between correlation and causation.

Some have argued that the critical period doesn't apply to second language acquisition. Instead of age being the main factor, other elements such as the effort put in, the learning environment, and time spent learning have a more significant influence on the learner's success.

Critical Period - Key takeaways

- The critical period is said to take place in adolescence, typically from 2 years old until puberty.

- The brain has a higher level of neuroplasticity during the critical period, which allows new synaptic connections to form.

- Eric Lenneberg introduced the hypothesis in 1967.

- The case of Genie, the feral child, offered direct evidence in support of the CPH.

- The difficulty adult learners have in learning a second language is used to support the CPH.

1. Kenji Hakuta et al, Critical Evidence: A Test of the Critical-Period Hypothesis for Second-Language Acquisition, 2003 .

2. Angela D. Friederici et al, Brain signatures of artificial language processing: Evidence challenging the critical period hypothesis, 2002 .

3. Birdsong D. , Second Language Acquisition and the Critical Period Hypothesis. Routledge, 1999 .

Flashcards inCritical Period 52

Eric Lenneberg was born in ________ in 1921.

How are adolescents more capable of learning a new language than adults?

The brain of adolescents has a higher level of neuroplasticity since they are still in the critical period.

What field of linguistics did Lenneberg play a major role in?

Biolinguistics

At university, Lenneberg studied:

Why was Genie unable to develop native proficiency in her first language?

She didn’t have the opportunity to develop basic language skills during the critical period.

True or False? Adults are unable to develop native proficiency in a second language.

False. It is more difficult, but adults can still develop full proficiency in a second language.

Learn with 52 Critical Period flashcards in the free Vaia app

We have 14,000 flashcards about Dynamic Landscapes.

Already have an account? Log in

Frequently Asked Questions about Critical Period

What a critical periods?

The critical time for a person to learn a new language with native proficiency.

What happens during the critical period?

The brain is more neuroplastic during this period, making it easier for a person to learn a new skill.

How long is the critical period?

The common period for the critical period is from 2 years old until puberty. Although academics differ slightly on the age range for the critical period.

What is the critical period hypothesis?

The Critical Period Hypothesis (CPH) holds that there is a critical time period for a person to learn a new language to a native proficiency.

What is critical period example

An example of the critical period is Genie the 'feral child'. Genie was isolated from birth and was not exposed to language in her first 13 years of life. Once she was rescued, she was able to grow her vocabulary, however, she did not acquire a native level of fluency in terms of grammar. Her case supports the critical period hypothesis but it is also important to remember the effect of her inhumane treatment on her ability to learn language.

Test your knowledge with multiple choice flashcards

Join the Vaia App and learn efficiently with millions of flashcards and more!

Keep learning, you are doing great.

Vaia is a globally recognized educational technology company, offering a holistic learning platform designed for students of all ages and educational levels. Our platform provides learning support for a wide range of subjects, including STEM, Social Sciences, and Languages and also helps students to successfully master various tests and exams worldwide, such as GCSE, A Level, SAT, ACT, Abitur, and more. We offer an extensive library of learning materials, including interactive flashcards, comprehensive textbook solutions, and detailed explanations. The cutting-edge technology and tools we provide help students create their own learning materials. StudySmarter’s content is not only expert-verified but also regularly updated to ensure accuracy and relevance.

Vaia Editorial Team

Team Critical Period Teachers

- 7 minutes reading time

- Checked by Vaia Editorial Team

Study anywhere. Anytime.Across all devices.

Create a free account to save this explanation..

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

By signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of Vaia.

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Join over 22 million students in learning with our Vaia App

The first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

- Flashcards & Quizzes

- AI Study Assistant

- Study Planner

- Smart Note-Taking

Privacy Overview

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Critical Period Hypothesis in Second Language Acquisition: A Statistical Critique and a Reanalysis

Jan vanhove.

Department of Multilingualism, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland

Analyzed the data: JV. Wrote the paper: JV.

Associated Data

In second language acquisition research, the critical period hypothesis ( cph ) holds that the function between learners' age and their susceptibility to second language input is non-linear. This paper revisits the indistinctness found in the literature with regard to this hypothesis's scope and predictions. Even when its scope is clearly delineated and its predictions are spelt out, however, empirical studies–with few exceptions–use analytical (statistical) tools that are irrelevant with respect to the predictions made. This paper discusses statistical fallacies common in cph research and illustrates an alternative analytical method (piecewise regression) by means of a reanalysis of two datasets from a 2010 paper purporting to have found cross-linguistic evidence in favour of the cph . This reanalysis reveals that the specific age patterns predicted by the cph are not cross-linguistically robust. Applying the principle of parsimony, it is concluded that age patterns in second language acquisition are not governed by a critical period. To conclude, this paper highlights the role of confirmation bias in the scientific enterprise and appeals to second language acquisition researchers to reanalyse their old datasets using the methods discussed in this paper. The data and R commands that were used for the reanalysis are provided as supplementary materials.

Introduction

In the long term and in immersion contexts, second-language (L2) learners starting acquisition early in life – and staying exposed to input and thus learning over several years or decades – undisputedly tend to outperform later learners. Apart from being misinterpreted as an argument in favour of early foreign language instruction, which takes place in wholly different circumstances, this general age effect is also sometimes taken as evidence for a so-called ‘critical period’ ( cp ) for second-language acquisition ( sla ). Derived from biology, the cp concept was famously introduced into the field of language acquisition by Penfield and Roberts in 1959 [1] and was refined by Lenneberg eight years later [2] . Lenneberg argued that language acquisition needed to take place between age two and puberty – a period which he believed to coincide with the lateralisation process of the brain. (More recent neurological research suggests that different time frames exist for the lateralisation process of different language functions. Most, however, close before puberty [3] .) However, Lenneberg mostly drew on findings pertaining to first language development in deaf children, feral children or children with serious cognitive impairments in order to back up his claims. For him, the critical period concept was concerned with the implicit “automatic acquisition” [2, p. 176] in immersion contexts and does not preclude the possibility of learning a foreign language after puberty, albeit with much conscious effort and typically less success.

sla research adopted the critical period hypothesis ( cph ) and applied it to second and foreign language learning, resulting in a host of studies. In its most general version, the cph for sla states that the ‘susceptibility’ or ‘sensitivity’ to language input varies as a function of age, with adult L2 learners being less susceptible to input than child L2 learners. Importantly, the age–susceptibility function is hypothesised to be non-linear. Moving beyond this general version, we find that the cph is conceptualised in a multitude of ways [4] . This state of affairs requires scholars to make explicit their theoretical stance and assumptions [5] , but has the obvious downside that critical findings risk being mitigated as posing a problem to only one aspect of one particular conceptualisation of the cph , whereas other conceptualisations remain unscathed. This overall vagueness concerns two areas in particular, viz. the delineation of the cph 's scope and the formulation of testable predictions. Delineating the scope and formulating falsifiable predictions are, needless to say, fundamental stages in the scientific evaluation of any hypothesis or theory, but the lack of scholarly consensus on these points seems to be particularly pronounced in the case of the cph . This article therefore first presents a brief overview of differing views on these two stages. Then, once the scope of their cph version has been duly identified and empirical data have been collected using solid methods, it is essential that researchers analyse the data patterns soundly in order to assess the predictions made and that they draw justifiable conclusions from the results. As I will argue in great detail, however, the statistical analysis of data patterns as well as their interpretation in cph research – and this includes both critical and supportive studies and overviews – leaves a great deal to be desired. Reanalysing data from a recent cph -supportive study, I illustrate some common statistical fallacies in cph research and demonstrate how one particular cph prediction can be evaluated.

Delineating the scope of the critical period hypothesis

First, the age span for a putative critical period for language acquisition has been delimited in different ways in the literature [4] . Lenneberg's critical period stretched from two years of age to puberty (which he posits at about 14 years of age) [2] , whereas other scholars have drawn the cutoff point at 12, 15, 16 or 18 years of age [6] . Unlike Lenneberg, most researchers today do not define a starting age for the critical period for language learning. Some, however, consider the possibility of the critical period (or a critical period for a specific language area, e.g. phonology) ending much earlier than puberty (e.g. age 9 years [1] , or as early as 12 months in the case of phonology [7] ).

Second, some vagueness remains as to the setting that is relevant to the cph . Does the critical period constrain implicit learning processes only, i.e. only the untutored language acquisition in immersion contexts or does it also apply to (at least partly) instructed learning? Most researchers agree on the former [8] , but much research has included subjects who have had at least some instruction in the L2.

Third, there is no consensus on what the scope of the cp is as far as the areas of language that are concerned. Most researchers agree that a cp is most likely to constrain the acquisition of pronunciation and grammar and, consequently, these are the areas primarily looked into in studies on the cph [9] . Some researchers have also tried to define distinguishable cp s for the different language areas of phonetics, morphology and syntax and even for lexis (see [10] for an overview).

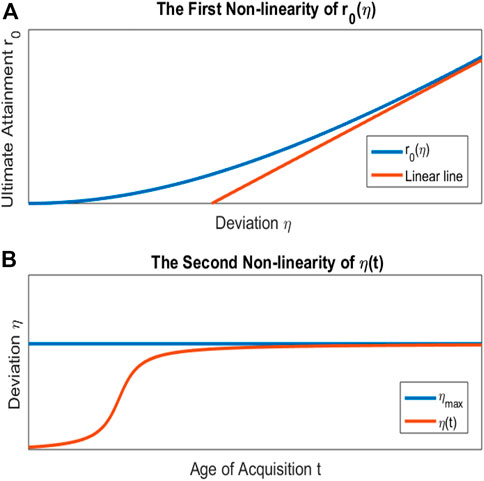

Fourth and last, research into the cph has focused on ‘ultimate attainment’ ( ua ) or the ‘final’ state of L2 proficiency rather than on the rate of learning. From research into the rate of acquisition (e.g. [11] – [13] ), it has become clear that the cph cannot hold for the rate variable. In fact, it has been observed that adult learners proceed faster than child learners at the beginning stages of L2 acquisition. Though theoretical reasons for excluding the rate can be posited (the initial faster rate of learning in adults may be the result of more conscious cognitive strategies rather than to less conscious implicit learning, for instance), rate of learning might from a different perspective also be considered an indicator of ‘susceptibility’ or ‘sensitivity’ to language input. Nevertheless, contemporary sla scholars generally seem to concur that ua and not rate of learning is the dependent variable of primary interest in cph research. These and further scope delineation problems relevant to cph research are discussed in more detail by, among others, Birdsong [9] , DeKeyser and Larson-Hall [14] , Long [10] and Muñoz and Singleton [6] .

Formulating testable hypotheses

Once the relevant cph 's scope has satisfactorily been identified, clear and testable predictions need to be drawn from it. At this stage, the lack of consensus on what the consequences or the actual observable outcome of a cp would have to look like becomes evident. As touched upon earlier, cph research is interested in the end state or ‘ultimate attainment’ ( ua ) in L2 acquisition because this “determines the upper limits of L2 attainment” [9, p. 10]. The range of possible ultimate attainment states thus helps researchers to explore the potential maximum outcome of L2 proficiency before and after the putative critical period.

One strong prediction made by some cph exponents holds that post- cp learners cannot reach native-like L2 competences. Identifying a single native-like post- cp L2 learner would then suffice to falsify all cph s making this prediction. Assessing this prediction is difficult, however, since it is not clear what exactly constitutes sufficient nativelikeness, as illustrated by the discussion on the actual nativelikeness of highly accomplished L2 speakers [15] , [16] . Indeed, there exists a real danger that, in a quest to vindicate the cph , scholars set the bar for L2 learners to match monolinguals increasingly higher – up to Swiftian extremes. Furthermore, the usefulness of comparing the linguistic performance in mono- and bilinguals has been called into question [6] , [17] , [18] . Put simply, the linguistic repertoires of mono- and bilinguals differ by definition and differences in the behavioural outcome will necessarily be found, if only one digs deep enough.

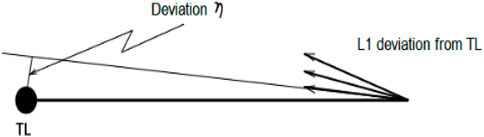

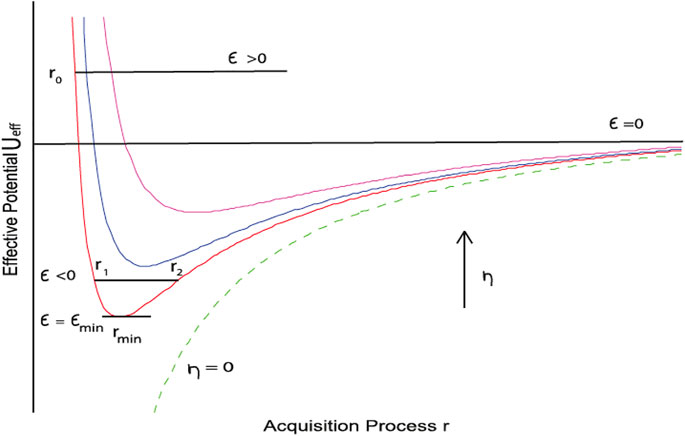

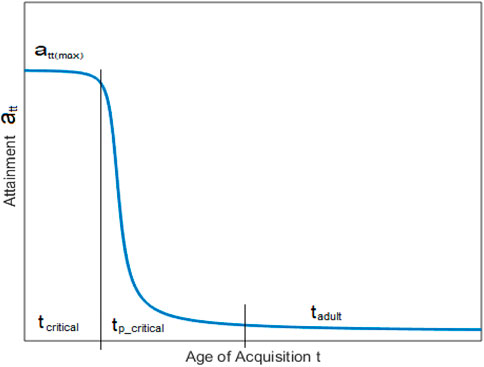

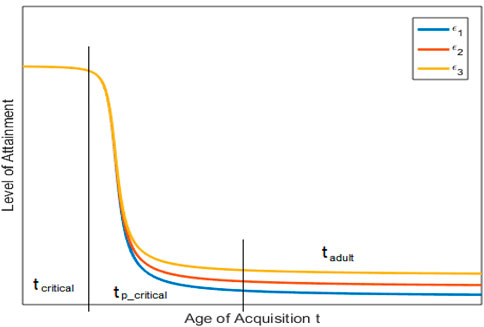

A second strong prediction made by cph proponents is that the function linking age of acquisition and ultimate attainment will not be linear throughout the whole lifespan. Before discussing how this function would have to look like in order for it to constitute cph -consistent evidence, I point out that the ultimate attainment variable can essentially be considered a cumulative measure dependent on the actual variable of interest in cph research, i.e. susceptibility to language input, as well as on such other factors like duration and intensity of learning (within and outside a putative cp ) and possibly a number of other influencing factors. To elaborate, the behavioural outcome, i.e. ultimate attainment, can be assumed to be integrative to the susceptibility function, as Newport [19] correctly points out. Other things being equal, ultimate attainment will therefore decrease as susceptibility decreases. However, decreasing ultimate attainment levels in and by themselves represent no compelling evidence in favour of a cph . The form of the integrative curve must therefore be predicted clearly from the susceptibility function. Additionally, the age of acquisition–ultimate attainment function can take just about any form when other things are not equal, e.g. duration of learning (Does learning last up until time of testing or only for a more or less constant number of years or is it dependent on age itself?) or intensity of learning (Do learners always learn at their maximum susceptibility level or does this intensity vary as a function of age, duration, present attainment and motivation?). The integral of the susceptibility function could therefore be of virtually unlimited complexity and its parameters could be adjusted to fit any age of acquisition–ultimate attainment pattern. It seems therefore astonishing that the distinction between level of sensitivity to language input and level of ultimate attainment is rarely made in the literature. Implicitly or explicitly [20] , the two are more or less equated and the same mathematical functions are expected to describe the two variables if observed across a range of starting ages of acquisition.

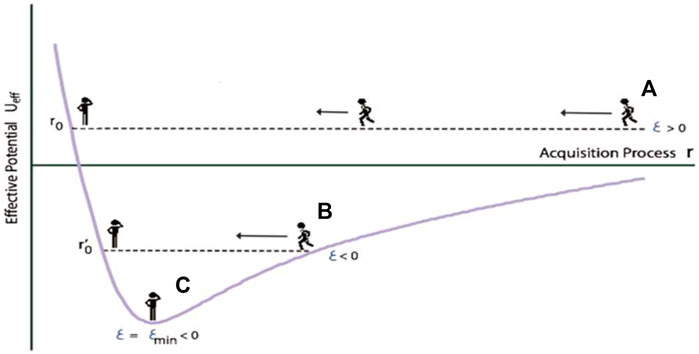

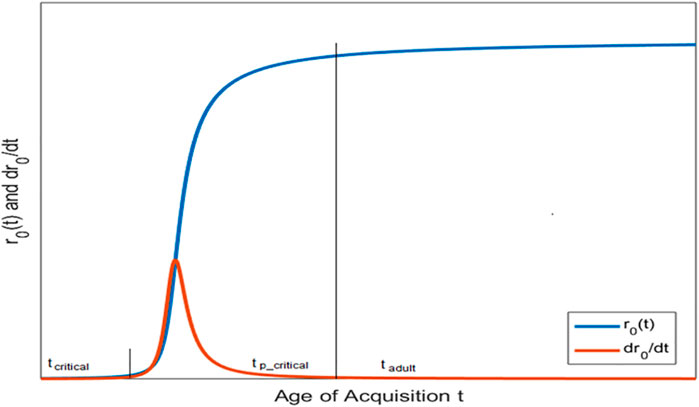

But even when the susceptibility and ultimate attainment variables are equated, there remains controversy as to what function linking age of onset of acquisition and ultimate attainment would actually constitute evidence for a critical period. Most scholars agree that not any kind of age effect constitutes such evidence. More specifically, the age of acquisition–ultimate attainment function would need to be different before and after the end of the cp [9] . According to Birdsong [9] , three basic possible patterns proposed in the literature meet this condition. These patterns are presented in Figure 1 . The first pattern describes a steep decline of the age of onset of acquisition ( aoa )–ultimate attainment ( ua ) function up to the end of the cp and a practically non-existent age effect thereafter. Pattern 2 is an “unconventional, although often implicitly invoked” [9, p. 17] notion of the cp function which contains a period of peak attainment (or performance at ceiling), i.e. performance does not vary as a function of age, which is often referred to as a ‘window of opportunity’. This time span is followed by an unbounded decline in ua depending on aoa . Pattern 3 includes characteristics of patterns 1 and 2. At the beginning of the aoa range, performance is at ceiling. The next segment is a downward slope in the age function which ends when performance reaches its floor. Birdsong points out that all of these patterns have been reported in the literature. On closer inspection, however, he concludes that the most convincing function describing these age effects is a simple linear one. Hakuta et al. [21] sketch further theoretically possible predictions of the cph in which the mean performance drops drastically and/or the slope of the aoa – ua proficiency function changes at a certain point.

The graphs are based on based on Figure 2 in [9] .

Although several patterns have been proposed in the literature, it bears pointing out that the most common explicit prediction corresponds to Birdsong's first pattern, as exemplified by the following crystal-clear statement by DeKeyser, one of the foremost cph proponents:

[A] strong negative correlation between age of acquisition and ultimate attainment throughout the lifespan (or even from birth through middle age), the only age effect documented in many earlier studies, is not evidence for a critical period…[T]he critical period concept implies a break in the AoA–proficiency function, i.e., an age (somewhat variable from individual to individual, of course, and therefore an age range in the aggregate) after which the decline of success rate in one or more areas of language is much less pronounced and/or clearly due to different reasons. [22, p. 445].

DeKeyser and before him among others Johnson and Newport [23] thus conceptualise only one possible pattern which would speak in favour of a critical period: a clear negative age effect before the end of the critical period and a much weaker (if any) negative correlation between age and ultimate attainment after it. This ‘flattened slope’ prediction has the virtue of being much more tangible than the ‘potential nativelikeness’ prediction: Testing it does not necessarily require comparing the L2-learners to a native control group and thus effectively comparing apples and oranges. Rather, L2-learners with different aoa s can be compared amongst themselves without the need to categorise them by means of a native-speaker yardstick, the validity of which is inevitably going to be controversial [15] . In what follows, I will concern myself solely with the ‘flattened slope’ prediction, arguing that, despite its clarity of formulation, cph research has generally used analytical methods that are irrelevant for the purposes of actually testing it.

Inferring non-linearities in critical period research: An overview

Group mean or proportion comparisons

[T]he main differences can be found between the native group and all other groups – including the earliest learner group – and between the adolescence group and all other groups. However, neither the difference between the two childhood groups nor the one between the two adulthood groups reached significance, which indicates that the major changes in eventual perceived nativelikeness of L2 learners can be associated with adolescence. [15, p. 270].

Similar group comparisons aimed at investigating the effect of aoa on ua have been carried out by both cph advocates and sceptics (among whom Bialystok and Miller [25, pp. 136–139], Birdsong and Molis [26, p. 240], Flege [27, pp. 120–121], Flege et al. [28, pp. 85–86], Johnson [29, p. 229], Johnson and Newport [23, p. 78], McDonald [30, pp. 408–410] and Patowski [31, pp. 456–458]). To be clear, not all of these authors drew direct conclusions about the aoa – ua function on the basis of these groups comparisons, but their group comparisons have been cited as indicative of a cph -consistent non-continuous age effect, as exemplified by the following quote by DeKeyser [22] :

Where group comparisons are made, younger learners always do significantly better than the older learners. The behavioral evidence, then, suggests a non-continuous age effect with a “bend” in the AoA–proficiency function somewhere between ages 12 and 16. [22, p. 448].

The first problem with group comparisons like these and drawing inferences on the basis thereof is that they require that a continuous variable, aoa , be split up into discrete bins. More often than not, the boundaries between these bins are drawn in an arbitrary fashion, but what is more troublesome is the loss of information and statistical power that such discretisation entails (see [32] for the extreme case of dichotomisation). If we want to find out more about the relationship between aoa and ua , why throw away most of the aoa information and effectively reduce the ua data to group means and the variance in those groups?

Comparison of correlation coefficients

Correlation-based inferences about slope discontinuities have similarly explicitly been made by cph advocates and skeptics alike, e.g. Bialystok and Miller [25, pp. 136 and 140], DeKeyser and colleagues [22] , [44] and Flege et al. [45, pp. 166 and 169]. Others did not explicitly infer the presence or absence of slope differences from the subset correlations they computed (among others Birdsong and Molis [26] , DeKeyser [8] , Flege et al. [28] and Johnson [29] ), but their studies nevertheless featured in overviews discussing discontinuities [14] , [22] . Indeed, the most recent overview draws a strong conclusion about the validity of the cph 's ‘flattened slope’ prediction on the basis of these subset correlations:

In those studies where the two groups are described separately, the correlation is much higher for the younger than for the older group, except in Birdsong and Molis (2001) [ = [26] , JV], where there was a ceiling effect for the younger group. This global picture from more than a dozen studies provides support for the non-continuity of the decline in the AoA–proficiency function, which all researchers agree is a hallmark of a critical period phenomenon. [22, p. 448].

In Johnson and Newport's specific case [23] , their correlation-based inference that ua levels off after puberty happened to be largely correct: the gjt scores are more or less randomly distributed around a near-horizontal trend line [26] . Ultimately, however, it rests on the fallacy of confusing correlation coefficients with slopes, which seriously calls into question conclusions such as DeKeyser's (cf. the quote above).

It can then straightforwardly be deduced that, other things equal, the aoa – ua correlation in the older group decreases as the ua variance in the older group increases relative to the ua variance in the younger group (Eq. 3).

Lower correlation coefficients in older aoa groups may therefore be largely due to differences in ua variance, which have been reported in several studies [23] , [26] , [28] , [29] (see [46] for additional references). Greater variability in ua with increasing age is likely due to factors other than age proper [47] , such as the concomitant greater variability in exposure to literacy, degree of education, motivation and opportunity for language use, and by itself represents evidence neither in favour of nor against the cph .

Regression approaches

Having demonstrated that neither group mean or proportion comparisons nor correlation coefficient comparisons can directly address the ‘flattened slope’ prediction, I now turn to the studies in which regression models were computed with aoa as a predictor variable and ua as the outcome variable. Once again, this category of studies is not mutually exclusive with the two categories discussed above.

In a large-scale study using self-reports and approximate aoa s derived from a sample of the 1990 U.S. Census, Stevens found that the probability with which immigrants from various countries stated that they spoke English ‘very well’ decreased curvilinearly as a function of aoa [48] . She noted that this development is similar to the pattern found by Johnson and Newport [23] but that it contains no indication of an “abruptly defined ‘critical’ or sensitive period in L2 learning” [48, p. 569]. However, she modelled the self-ratings using an ordinal logistic regression model in which the aoa variable was logarithmically transformed. Technically, this is perfectly fine, but one should be careful not to read too much into the non-linear curves found. In logistic models, the outcome variable itself is modelled linearly as a function of the predictor variables and is expressed in log-odds. In order to compute the corresponding probabilities, these log-odds are transformed using the logistic function. Consequently, even if the model is specified linearly, the predicted probabilities will not lie on a perfectly straight line when plotted as a function of any one continuous predictor variable. Similarly, when the predictor variable is first logarithmically transformed and then used to linearly predict an outcome variable, the function linking the predicted outcome variables and the untransformed predictor variable is necessarily non-linear. Thus, non-linearities follow naturally from Stevens's model specifications. Moreover, cph -consistent discontinuities in the aoa – ua function cannot be found using her model specifications as they did not contain any parameters allowing for this.

Using data similar to Stevens's, Bialystok and Hakuta found that the link between the self-rated English competences of Chinese- and Spanish-speaking immigrants and their aoa could be described by a straight line [49] . In contrast to Stevens, Bialystok and Hakuta used a regression-based method allowing for changes in the function's slope, viz. locally weighted scatterplot smoothing ( lowess ). Informally, lowess is a non-parametrical method that relies on an algorithm that fits the dependent variable for small parts of the range of the independent variable whilst guaranteeing that the overall curve does not contain sudden jumps (for technical details, see [50] ). Hakuta et al. used an even larger sample from the same 1990 U.S. Census data on Chinese- and Spanish-speaking immigrants (2.3 million observations) [21] . Fitting lowess curves, no discontinuities in the aoa – ua slope could be detected. Moreover, the authors found that piecewise linear regression models, i.e. regression models containing a parameter that allows a sudden drop in the curve or a change of its slope, did not provide a better fit to the data than did an ordinary regression model without such a parameter.

To sum up, I have argued at length that regression approaches are superior to group mean and correlation coefficient comparisons for the purposes of testing the ‘flattened slope’ prediction. Acknowledging the reservations vis-à-vis self-estimated ua s, we still find that while the relationship between aoa and ua is not necessarily perfectly linear in the studies discussed, the data do not lend unequivocal support to this prediction. In the following section, I will reanalyse data from a recent empirical paper on the cph by DeKeyser et al. [44] . The first goal of this reanalysis is to further illustrate some of the statistical fallacies encountered in cph studies. Second, by making the computer code available I hope to demonstrate how the relevant regression models, viz. piecewise regression models, can be fitted and how the aoa representing the optimal breakpoint can be identified. Lastly, the findings of this reanalysis will contribute to our understanding of how aoa affects ua as measured using a gjt .

Summary of DeKeyser et al. (2010)

I chose to reanalyse a recent empirical paper on the cph by DeKeyser et al. [44] (henceforth DK et al.). This paper lends itself well to a reanalysis since it exhibits two highly commendable qualities: the authors spell out their hypotheses lucidly and provide detailed numerical and graphical data descriptions. Moreover, the paper's lead author is very clear on what constitutes a necessary condition for accepting the cph : a non-linearity in the age of onset of acquisition ( aoa )–ultimate attainment ( ua ) function, with ua declining less strongly as a function of aoa in older, post- cp arrivals compared to younger arrivals [14] , [22] . Lastly, it claims to have found cross-linguistic evidence from two parallel studies backing the cph and should therefore be an unsuspected source to cph proponents.

The authors set out to test the following hypotheses:

- Hypothesis 1: For both the L2 English and the L2 Hebrew group, the slope of the age of arrival–ultimate attainment function will not be linear throughout the lifespan, but will instead show a marked flattening between adolescence and adulthood.

- Hypothesis 2: The relationship between aptitude and ultimate attainment will differ markedly for the young and older arrivals, with significance only for the latter. (DK et al., p. 417)

Both hypotheses were purportedly confirmed, which in the authors' view provides evidence in favour of cph . The problem with this conclusion, however, is that it is based on a comparison of correlation coefficients. As I have argued above, correlation coefficients are not to be confused with regression coefficients and cannot be used to directly address research hypotheses concerning slopes, such as Hypothesis 1. In what follows, I will reanalyse the relationship between DK et al.'s aoa and gjt data in order to address Hypothesis 1. Additionally, I will lay bare a problem with the way in which Hypothesis 2 was addressed. The extracted data and the computer code used for the reanalysis are provided as supplementary materials, allowing anyone interested to scrutinise and easily reproduce my whole analysis and carry out their own computations (see ‘supporting information’).

Data extraction

In order to verify whether we did in fact extract the data points to a satisfactory degree of accuracy, I computed summary statistics for the extracted aoa and gjt data and checked these against the descriptive statistics provided by DK et al. (pp. 421 and 427). These summary statistics for the extracted data are presented in Table 1 . In addition, I computed the correlation coefficients for the aoa – gjt relationship for the whole aoa range and for aoa -defined subgroups and checked these coefficients against those reported by DK et al. (pp. 423 and 428). The correlation coefficients computed using the extracted data are presented in Table 2 . Both checks strongly suggest the extracted data to be virtually identical to the original data, and Dr DeKeyser confirmed this to be the case in response to an earlier draft of the present paper (personal communication, 6 May 2013).

Results and Discussion

Modelling the link between age of onset of acquisition and ultimate attainment.

I first replotted the aoa and gjt data we extracted from DK et al.'s scatterplots and added non-parametric scatterplot smoothers in order to investigate whether any changes in slope in the aoa – gjt function could be revealed, as per Hypothesis 1. Figures 3 and and4 4 show this not to be the case. Indeed, simple linear regression models that model gjt as a function of aoa provide decent fits for both the North America and the Israel data, explaining 65% and 63% of the variance in gjt scores, respectively. The parameters of these models are given in Table 3 .

The trend line is a non-parametric scatterplot smoother. The scatterplot itself is a near-perfect replication of DK et al.'s Fig. 1.

The trend line is a non-parametric scatterplot smoother. The scatterplot itself is a near-perfect replication of DK et al.'s Fig. 5.

To ensure that both segments are joined at the breakpoint, the predictor variable is first centred at the breakpoint value, i.e. the breakpoint value is subtracted from the original predictor variable values. For a blow-by-blow account of how such models can be fitted in r , I refer to an example analysis by Baayen [55, pp. 214–222].

Solid: regression with breakpoint at aoa 18 (dashed lines represent its 95% confidence interval); dot-dash: regression without breakpoint.

Solid: regression with breakpoint at aoa 18 (dashed lines represent its 95% confidence interval); dot-dash (hardly visible due to near-complete overlap): regression without breakpoint.

Solid: regression with breakpoint at aoa 16 (dashed lines represent its 95% confidence interval); dot-dash: regression without breakpoint.

Solid: regression with breakpoint at aoa 6 (dashed lines represent its 95% confidence interval); dot-dash (hardly visible due to near-complete overlap): regression without breakpoint.