- A Model for the National Assessment of Higher Order Thinking

- International Critical Thinking Essay Test

- Online Critical Thinking Basic Concepts Test

- Online Critical Thinking Basic Concepts Sample Test

Consequential Validity: Using Assessment to Drive Instruction

Translate this page from English...

*Machine translated pages not guaranteed for accuracy. Click Here for our professional translations.

Critical Thinking Testing and Assessment

The purpose of assessment in instruction is improvement. The purpose of assessing instruction for critical thinking is improving the teaching of discipline-based thinking (historical, biological, sociological, mathematical, etc.) It is to improve students’ abilities to think their way through content using disciplined skill in reasoning. The more particular we can be about what we want students to learn about critical thinking, the better we can devise instruction with that particular end in view.

The Foundation for Critical Thinking offers assessment instruments which share in the same general goal: to enable educators to gather evidence relevant to determining the extent to which instruction is teaching students to think critically (in the process of learning content). To this end, the Fellows of the Foundation recommend:

that academic institutions and units establish an oversight committee for critical thinking, and

that this oversight committee utilizes a combination of assessment instruments (the more the better) to generate incentives for faculty, by providing them with as much evidence as feasible of the actual state of instruction for critical thinking.

The following instruments are available to generate evidence relevant to critical thinking teaching and learning:

Course Evaluation Form : Provides evidence of whether, and to what extent, students perceive faculty as fostering critical thinking in instruction (course by course). Machine-scoreable.

Online Critical Thinking Basic Concepts Test : Provides evidence of whether, and to what extent, students understand the fundamental concepts embedded in critical thinking (and hence tests student readiness to think critically). Machine-scoreable.

Critical Thinking Reading and Writing Test : Provides evidence of whether, and to what extent, students can read closely and write substantively (and hence tests students' abilities to read and write critically). Short-answer.

International Critical Thinking Essay Test : Provides evidence of whether, and to what extent, students are able to analyze and assess excerpts from textbooks or professional writing. Short-answer.

Commission Study Protocol for Interviewing Faculty Regarding Critical Thinking : Provides evidence of whether, and to what extent, critical thinking is being taught at a college or university. Can be adapted for high school. Based on the California Commission Study . Short-answer.

Protocol for Interviewing Faculty Regarding Critical Thinking : Provides evidence of whether, and to what extent, critical thinking is being taught at a college or university. Can be adapted for high school. Short-answer.

Protocol for Interviewing Students Regarding Critical Thinking : Provides evidence of whether, and to what extent, students are learning to think critically at a college or university. Can be adapted for high school). Short-answer.

Criteria for Critical Thinking Assignments : Can be used by faculty in designing classroom assignments, or by administrators in assessing the extent to which faculty are fostering critical thinking.

Rubrics for Assessing Student Reasoning Abilities : A useful tool in assessing the extent to which students are reasoning well through course content.

All of the above assessment instruments can be used as part of pre- and post-assessment strategies to gauge development over various time periods.

Consequential Validity

All of the above assessment instruments, when used appropriately and graded accurately, should lead to a high degree of consequential validity. In other words, the use of the instruments should cause teachers to teach in such a way as to foster critical thinking in their various subjects. In this light, for students to perform well on the various instruments, teachers will need to design instruction so that students can perform well on them. Students cannot become skilled in critical thinking without learning (first) the concepts and principles that underlie critical thinking and (second) applying them in a variety of forms of thinking: historical thinking, sociological thinking, biological thinking, etc. Students cannot become skilled in analyzing and assessing reasoning without practicing it. However, when they have routine practice in paraphrasing, summarizing, analyzing, and assessing, they will develop skills of mind requisite to the art of thinking well within any subject or discipline, not to mention thinking well within the various domains of human life.

For full copies of this and many other critical thinking articles, books, videos, and more, join us at the Center for Critical Thinking Community Online - the world's leading online community dedicated to critical thinking! Also featuring interactive learning activities, study groups, and even a social media component, this learning platform will change your conception of intellectual development.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Back to Entry

- Entry Contents

- Entry Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Supplement to Critical Thinking

How can one assess, for purposes of instruction or research, the degree to which a person possesses the dispositions, skills and knowledge of a critical thinker?

In psychometrics, assessment instruments are judged according to their validity and reliability.

Roughly speaking, an instrument is valid if it measures accurately what it purports to measure, given standard conditions. More precisely, the degree of validity is “the degree to which evidence and theory support the interpretations of test scores for proposed uses of tests” (American Educational Research Association 2014: 11). In other words, a test is not valid or invalid in itself. Rather, validity is a property of an interpretation of a given score on a given test for a specified use. Determining the degree of validity of such an interpretation requires collection and integration of the relevant evidence, which may be based on test content, test takers’ response processes, a test’s internal structure, relationship of test scores to other variables, and consequences of the interpretation (American Educational Research Association 2014: 13–21). Criterion-related evidence consists of correlations between scores on the test and performance on another test of the same construct; its weight depends on how well supported is the assumption that the other test can be used as a criterion. Content-related evidence is evidence that the test covers the full range of abilities that it claims to test. Construct-related evidence is evidence that a correct answer reflects good performance of the kind being measured and an incorrect answer reflects poor performance.

An instrument is reliable if it consistently produces the same result, whether across different forms of the same test (parallel-forms reliability), across different items (internal consistency), across different administrations to the same person (test-retest reliability), or across ratings of the same answer by different people (inter-rater reliability). Internal consistency should be expected only if the instrument purports to measure a single undifferentiated construct, and thus should not be expected of a test that measures a suite of critical thinking dispositions or critical thinking abilities, assuming that some people are better in some of the respects measured than in others (for example, very willing to inquire but rather closed-minded). Otherwise, reliability is a necessary but not a sufficient condition of validity; a standard example of a reliable instrument that is not valid is a bathroom scale that consistently under-reports a person’s weight.

Assessing dispositions is difficult if one uses a multiple-choice format with known adverse consequences of a low score. It is pretty easy to tell what answer to the question “How open-minded are you?” will get the highest score and to give that answer, even if one knows that the answer is incorrect. If an item probes less directly for a critical thinking disposition, for example by asking how often the test taker pays close attention to views with which the test taker disagrees, the answer may differ from reality because of self-deception or simple lack of awareness of one’s personal thinking style, and its interpretation is problematic, even if factor analysis enables one to identify a distinct factor measured by a group of questions that includes this one (Ennis 1996). Nevertheless, Facione, Sánchez, and Facione (1994) used this approach to develop the California Critical Thinking Dispositions Inventory (CCTDI). They began with 225 statements expressive of a disposition towards or away from critical thinking (using the long list of dispositions in Facione 1990a), validated the statements with talk-aloud and conversational strategies in focus groups to determine whether people in the target population understood the items in the way intended, administered a pilot version of the test with 150 items, and eliminated items that failed to discriminate among test takers or were inversely correlated with overall results or added little refinement to overall scores (Facione 2000). They used item analysis and factor analysis to group the measured dispositions into seven broad constructs: open-mindedness, analyticity, cognitive maturity, truth-seeking, systematicity, inquisitiveness, and self-confidence (Facione, Sánchez, and Facione 1994). The resulting test consists of 75 agree-disagree statements and takes 20 minutes to administer. A repeated disturbing finding is that North American students taking the test tend to score low on the truth-seeking sub-scale (on which a low score results from agreeing to such statements as the following: “To get people to agree with me I would give any reason that worked”. “Everyone always argues from their own self-interest, including me”. “If there are four reasons in favor and one against, I’ll go with the four”.) Development of the CCTDI made it possible to test whether good critical thinking abilities and good critical thinking dispositions go together, in which case it might be enough to teach one without the other. Facione (2000) reports that administration of the CCTDI and the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST) to almost 8,000 post-secondary students in the United States revealed a statistically significant but weak correlation between total scores on the two tests, and also between paired sub-scores from the two tests. The implication is that both abilities and dispositions need to be taught, that one cannot expect improvement in one to bring with it improvement in the other.

A more direct way of assessing critical thinking dispositions would be to see what people do when put in a situation where the dispositions would reveal themselves. Ennis (1996) reports promising initial work with guided open-ended opportunities to give evidence of dispositions, but no standardized test seems to have emerged from this work. There are however standardized aspect-specific tests of critical thinking dispositions. The Critical Problem Solving Scale (Berman et al. 2001: 518) takes as a measure of the disposition to suspend judgment the number of distinct good aspects attributed to an option judged to be the worst among those generated by the test taker. Stanovich, West and Toplak (2011: 800–810) list tests developed by cognitive psychologists of the following dispositions: resistance to miserly information processing, resistance to myside thinking, absence of irrelevant context effects in decision-making, actively open-minded thinking, valuing reason and truth, tendency to seek information, objective reasoning style, tendency to seek consistency, sense of self-efficacy, prudent discounting of the future, self-control skills, and emotional regulation.

It is easier to measure critical thinking skills or abilities than to measure dispositions. The following eight currently available standardized tests purport to measure them: the Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal (Watson & Glaser 1980a, 1980b, 1994), the Cornell Critical Thinking Tests Level X and Level Z (Ennis & Millman 1971; Ennis, Millman, & Tomko 1985, 2005), the Ennis-Weir Critical Thinking Essay Test (Ennis & Weir 1985), the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (Facione 1990b, 1992), the Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment (Halpern 2016), the Critical Thinking Assessment Test (Center for Assessment & Improvement of Learning 2017), the Collegiate Learning Assessment (Council for Aid to Education 2017), the HEIghten Critical Thinking Assessment (https://territorium.com/heighten/), and a suite of critical thinking assessments for different groups and purposes offered by Insight Assessment (https://www.insightassessment.com/products). The Critical Thinking Assessment Test (CAT) is unique among them in being designed for use by college faculty to help them improve their development of students’ critical thinking skills (Haynes et al. 2015; Haynes & Stein 2021). Also, for some years the United Kingdom body OCR (Oxford Cambridge and RSA Examinations) awarded AS and A Level certificates in critical thinking on the basis of an examination (OCR 2011). Many of these standardized tests have received scholarly evaluations at the hands of, among others, Ennis (1958), McPeck (1981), Norris and Ennis (1989), Fisher and Scriven (1997), Possin (2008, 2013a, 2013b, 2013c, 2014, 2020) and Hatcher and Possin (2021). Their evaluations provide a useful set of criteria that such tests ideally should meet, as does the description by Ennis (1984) of problems in testing for competence in critical thinking: the soundness of multiple-choice items, the clarity and soundness of instructions to test takers, the information and mental processing used in selecting an answer to a multiple-choice item, the role of background beliefs and ideological commitments in selecting an answer to a multiple-choice item, the tenability of a test’s underlying conception of critical thinking and its component abilities, the set of abilities that the test manual claims are covered by the test, the extent to which the test actually covers these abilities, the appropriateness of the weighting given to various abilities in the scoring system, the accuracy and intellectual honesty of the test manual, the interest of the test to the target population of test takers, the scope for guessing, the scope for choosing a keyed answer by being test-wise, precautions against cheating in the administration of the test, clarity and soundness of materials for training essay graders, inter-rater reliability in grading essays, and clarity and soundness of advance guidance to test takers on what is required in an essay. Rear (2019) has challenged the use of standardized tests of critical thinking as a way to measure educational outcomes, on the grounds that they (1) fail to take into account disputes about conceptions of critical thinking, (2) are not completely valid or reliable, and (3) fail to evaluate skills used in real academic tasks. He proposes instead assessments based on discipline-specific content.

There are also aspect-specific standardized tests of critical thinking abilities. Stanovich, West and Toplak (2011: 800–810) list tests of probabilistic reasoning, insights into qualitative decision theory, knowledge of scientific reasoning, knowledge of rules of logical consistency and validity, and economic thinking. They also list instruments that probe for irrational thinking, such as superstitious thinking, belief in the superiority of intuition, over-reliance on folk wisdom and folk psychology, belief in “special” expertise, financial misconceptions, overestimation of one’s introspective powers, dysfunctional beliefs, and a notion of self that encourages egocentric processing. They regard these tests along with the previously mentioned tests of critical thinking dispositions as the building blocks for a comprehensive test of rationality, whose development (they write) may be logistically difficult and would require millions of dollars.

A superb example of assessment of an aspect of critical thinking ability is the Test on Appraising Observations (Norris & King 1983, 1985, 1990a, 1990b), which was designed for classroom administration to senior high school students. The test focuses entirely on the ability to appraise observation statements and in particular on the ability to determine in a specified context which of two statements there is more reason to believe. According to the test manual (Norris & King 1985, 1990b), a person’s score on the multiple-choice version of the test, which is the number of items that are answered correctly, can justifiably be given either a criterion-referenced or a norm-referenced interpretation.

On a criterion-referenced interpretation, those who do well on the test have a firm grasp of the principles for appraising observation statements, and those who do poorly have a weak grasp of them. This interpretation can be justified by the content of the test and the way it was developed, which incorporated a method of controlling for background beliefs articulated and defended by Norris (1985). Norris and King synthesized from judicial practice, psychological research and common-sense psychology 31 principles for appraising observation statements, in the form of empirical generalizations about tendencies, such as the principle that observation statements tend to be more believable than inferences based on them (Norris & King 1984). They constructed items in which exactly one of the 31 principles determined which of two statements was more believable. Using a carefully constructed protocol, they interviewed about 100 students who responded to these items in order to determine the thinking that led them to choose the answers they did (Norris & King 1984). In several iterations of the test, they adjusted items so that selection of the correct answer generally reflected good thinking and selection of an incorrect answer reflected poor thinking. Thus they have good evidence that good performance on the test is due to good thinking about observation statements and that poor performance is due to poor thinking about observation statements. Collectively, the 50 items on the final version of the test require application of 29 of the 31 principles for appraising observation statements, with 13 principles tested by one item, 12 by two items, three by three items, and one by four items. Thus there is comprehensive coverage of the principles for appraising observation statements. Fisher and Scriven (1997: 135–136) judge the items to be well worked and sound, with one exception. The test is clearly written at a grade 6 reading level, meaning that poor performance cannot be attributed to difficulties in reading comprehension by the intended adolescent test takers. The stories that frame the items are realistic, and are engaging enough to stimulate test takers’ interest. Thus the most plausible explanation of a given score on the test is that it reflects roughly the degree to which the test taker can apply principles for appraising observations in real situations. In other words, there is good justification of the proposed interpretation that those who do well on the test have a firm grasp of the principles for appraising observation statements and those who do poorly have a weak grasp of them.

To get norms for performance on the test, Norris and King arranged for seven groups of high school students in different types of communities and with different levels of academic ability to take the test. The test manual includes percentiles, means, and standard deviations for each of these seven groups. These norms allow teachers to compare the performance of their class on the test to that of a similar group of students.

Copyright © 2022 by David Hitchcock < hitchckd @ mcmaster . ca >

- Accessibility

Support SEP

Mirror sites.

View this site from another server:

- Info about mirror sites

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is copyright © 2024 by The Metaphysics Research Lab , Department of Philosophy, Stanford University

Library of Congress Catalog Data: ISSN 1095-5054

Why Schools Need to Change Yes, We Can Define, Teach, and Assess Critical Thinking Skills

Jeff Heyck-Williams (He, His, Him) Director of the Two Rivers Learning Institute in Washington, DC

Today’s learners face an uncertain present and a rapidly changing future that demand far different skills and knowledge than were needed in the 20th century. We also know so much more about enabling deep, powerful learning than we ever did before. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

Critical thinking is a thing. We can define it; we can teach it; and we can assess it.

While the idea of teaching critical thinking has been bandied around in education circles since at least the time of John Dewey, it has taken greater prominence in the education debates with the advent of the term “21st century skills” and discussions of deeper learning. There is increasing agreement among education reformers that critical thinking is an essential ingredient for long-term success for all of our students.

However, there are still those in the education establishment and in the media who argue that critical thinking isn’t really a thing, or that these skills aren’t well defined and, even if they could be defined, they can’t be taught or assessed.

To those naysayers, I have to disagree. Critical thinking is a thing. We can define it; we can teach it; and we can assess it. In fact, as part of a multi-year Assessment for Learning Project , Two Rivers Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., has done just that.

Before I dive into what we have done, I want to acknowledge that some of the criticism has merit.

First, there are those that argue that critical thinking can only exist when students have a vast fund of knowledge. Meaning that a student cannot think critically if they don’t have something substantive about which to think. I agree. Students do need a robust foundation of core content knowledge to effectively think critically. Schools still have a responsibility for building students’ content knowledge.

However, I would argue that students don’t need to wait to think critically until after they have mastered some arbitrary amount of knowledge. They can start building critical thinking skills when they walk in the door. All students come to school with experience and knowledge which they can immediately think critically about. In fact, some of the thinking that they learn to do helps augment and solidify the discipline-specific academic knowledge that they are learning.

The second criticism is that critical thinking skills are always highly contextual. In this argument, the critics make the point that the types of thinking that students do in history is categorically different from the types of thinking students do in science or math. Thus, the idea of teaching broadly defined, content-neutral critical thinking skills is impossible. I agree that there are domain-specific thinking skills that students should learn in each discipline. However, I also believe that there are several generalizable skills that elementary school students can learn that have broad applicability to their academic and social lives. That is what we have done at Two Rivers.

Defining Critical Thinking Skills

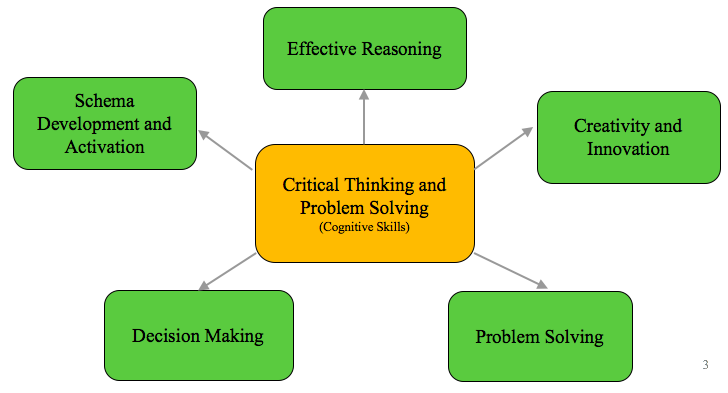

We began this work by first defining what we mean by critical thinking. After a review of the literature and looking at the practice at other schools, we identified five constructs that encompass a set of broadly applicable skills: schema development and activation; effective reasoning; creativity and innovation; problem solving; and decision making.

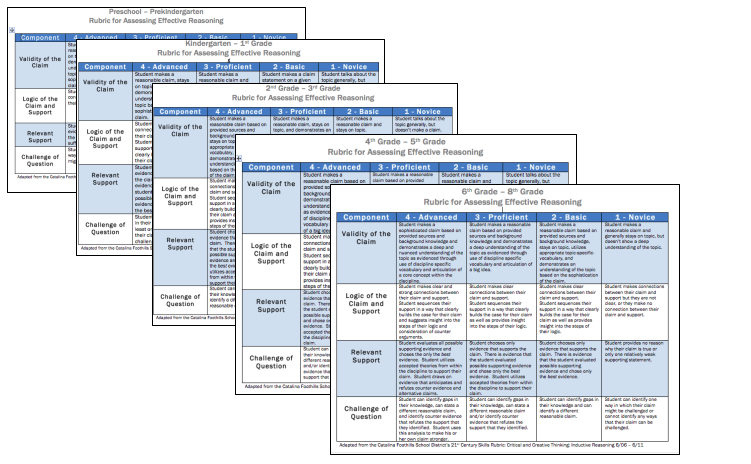

We then created rubrics to provide a concrete vision of what each of these constructs look like in practice. Working with the Stanford Center for Assessment, Learning and Equity (SCALE) , we refined these rubrics to capture clear and discrete skills.

For example, we defined effective reasoning as the skill of creating an evidence-based claim: students need to construct a claim, identify relevant support, link their support to their claim, and identify possible questions or counter claims. Rubrics provide an explicit vision of the skill of effective reasoning for students and teachers. By breaking the rubrics down for different grade bands, we have been able not only to describe what reasoning is but also to delineate how the skills develop in students from preschool through 8th grade.

Before moving on, I want to freely acknowledge that in narrowly defining reasoning as the construction of evidence-based claims we have disregarded some elements of reasoning that students can and should learn. For example, the difference between constructing claims through deductive versus inductive means is not highlighted in our definition. However, by privileging a definition that has broad applicability across disciplines, we are able to gain traction in developing the roots of critical thinking. In this case, to formulate well-supported claims or arguments.

Teaching Critical Thinking Skills

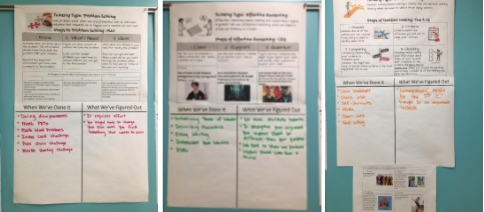

The definitions of critical thinking constructs were only useful to us in as much as they translated into practical skills that teachers could teach and students could learn and use. Consequently, we have found that to teach a set of cognitive skills, we needed thinking routines that defined the regular application of these critical thinking and problem-solving skills across domains. Building on Harvard’s Project Zero Visible Thinking work, we have named routines aligned with each of our constructs.

For example, with the construct of effective reasoning, we aligned the Claim-Support-Question thinking routine to our rubric. Teachers then were able to teach students that whenever they were making an argument, the norm in the class was to use the routine in constructing their claim and support. The flexibility of the routine has allowed us to apply it from preschool through 8th grade and across disciplines from science to economics and from math to literacy.

Kathryn Mancino, a 5th grade teacher at Two Rivers, has deliberately taught three of our thinking routines to students using the anchor charts above. Her charts name the components of each routine and has a place for students to record when they’ve used it and what they have figured out about the routine. By using this structure with a chart that can be added to throughout the year, students see the routines as broadly applicable across disciplines and are able to refine their application over time.

Assessing Critical Thinking Skills

By defining specific constructs of critical thinking and building thinking routines that support their implementation in classrooms, we have operated under the assumption that students are developing skills that they will be able to transfer to other settings. However, we recognized both the importance and the challenge of gathering reliable data to confirm this.

With this in mind, we have developed a series of short performance tasks around novel discipline-neutral contexts in which students can apply the constructs of thinking. Through these tasks, we have been able to provide an opportunity for students to demonstrate their ability to transfer the types of thinking beyond the original classroom setting. Once again, we have worked with SCALE to define tasks where students easily access the content but where the cognitive lift requires them to demonstrate their thinking abilities.

These assessments demonstrate that it is possible to capture meaningful data on students’ critical thinking abilities. They are not intended to be high stakes accountability measures. Instead, they are designed to give students, teachers, and school leaders discrete formative data on hard to measure skills.

While it is clearly difficult, and we have not solved all of the challenges to scaling assessments of critical thinking, we can define, teach, and assess these skills . In fact, knowing how important they are for the economy of the future and our democracy, it is essential that we do.

Jeff Heyck-Williams (He, His, Him)

Director of the two rivers learning institute.

Jeff Heyck-Williams is the director of the Two Rivers Learning Institute and a founder of Two Rivers Public Charter School. He has led work around creating school-wide cultures of mathematics, developing assessments of critical thinking and problem-solving, and supporting project-based learning.

Read More About Why Schools Need to Change

Equitable and Sustainable Social-Emotional Learning: Embracing Flexibility for Diverse Learners

Clementina Jose

May 30, 2024

Nurturing STEM Identity and Belonging: The Role of Equitable Program Implementation in Project Invent

Alexis Lopez (she/her)

May 9, 2024

Bring Your Vision for Student Success to Life with NGLC and Bravely

March 13, 2024

Critical Thinking About Measuring Critical Thinking

A list of critical thinking measures..

Posted May 18, 2018

- What Is Cognition?

- Find a therapist near me

In my last post , I discussed the nature of engaging the critical thinking (CT) process and made mention of individuals who draw a conclusion and wind up being correct. But, just because they’re right, it doesn’t mean they used CT to get there. I exemplified this through an observation made in recent years regarding extant measures of CT, many of which assess CT via multiple-choice questions. In the case of CT MCQs, you can guess the "right" answer 20-25% of the time, without any need for CT. So, the question is, are these CT measures really measuring CT?

As my previous articles explain, CT is a metacognitive process consisting of a number of sub-skills and dispositions, that, when applied through purposeful, self-regulatory, reflective judgment, increase the chances of producing a logical solution to a problem or a valid conclusion to an argument (Dwyer, 2017; Dwyer, Hogan & Stewart, 2014). Most definitions, though worded differently, tend to agree with this perspective – it consists of certain dispositions, specific skills and a reflective sensibility that governs application of these skills. That’s how it’s defined; however, it’s not necessarily how it’s been operationally defined.

Operationally defining something refers to defining the terms of the process or measure required to determine the nature and properties of a phenomenon. Simply, it is defining the concept with respect to how it can be done, assessed or measured. If the manner in which you measure something does not match, or assess the parameters set out in the way in which you define it, then you have not been successful in operationally defining it.

Though most theoretical definitions of CT are similar, the manner in which they vary often impedes the construction of an integrated theoretical account of how best to measure CT skills. As a result, researchers and educators must consider the wide array of CT measures available, in order to identify the best and the most appropriate measures, based on the CT conceptualisation used for training. There are various extant CT measures – the most popular amongst them include the Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Assessment (WGCTA; Watson & Glaser, 1980), the Cornell Critical Thinking Test (CCTT; Ennis, Millman & Tomko, 1985), the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST; Facione, 1990a), the Ennis-Weir Critical Thinking Essay Test (EWCTET; Ennis & Weir, 1985) and the Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment (Halpern, 2010).

It has been noted by some commentators that these different measures of CT ability may not be directly comparable (Abrami et al., 2008). For example, the WGCTA consists of 80 MCQs that measure the ability to draw inferences; recognise assumptions; evaluate arguments; and use logical interpretation and deductive reasoning (Watson & Glaser, 1980). The CCTT consists of 52 MCQs which measure skills of critical thinking associated with induction; deduction; observation and credibility; definition and assumption identification; and meaning and fallacies. Finally, the CCTST consists of 34 multiple-choice questions (MCQs) and measures CT according to the core skills of analysis, evaluation and inference, as well as inductive and deductive reasoning.

As addressed above, the MCQ-format of these three assessments is less than ideal – problematic even, because it allows test-takers to simply guess when they do not know the correct answer, instead of demonstrating their ability to critically analyse and evaluate problems and infer solutions to those problems (Ku, 2009). Furthermore, as argued by Halpern (2003), the MCQ format makes the assessment a test of verbal and quantitative knowledge rather than CT (i.e. because one selects from a list of possible answers rather than determining one’s own criteria for developing an answer). The measurement of CT through MCQs is also problematic given the potential incompatibility between the conceptualisation of CT that shapes test construction and its assessment using MCQs. That is, MCQ tests assess cognitive capacities associated with identifying single right-or-wrong answers and as a result, this approach to testing is unable to provide a direct measure of test-takers’ use of metacognitive processes such as CT, reflective judgment, and disposition towards CT.

Instead of using MCQ items, a better measure of CT might ask open-ended questions, which would allow test-takers to demonstrate whether or not they spontaneously use a specific CT skill. One commonly used CT assessment, mentioned above, that employs an open-ended format is the Ennis-Weir Critical Thinking Essay Test (EWCTET; Ennis & Weir, 1985). The EWCTET is an essay-based assessment of the test-taker’s ability to analyse, evaluate, and respond to arguments and debates in real-world situations (Ennis & Weir, 1985; see Ku, 2009 for a discussion). The authors of the EWCTET provide what they call a “rough, somewhat overlapping list of areas of critical thinking competence”, measured by their test (Ennis & Weir, 1985, p. 1). However, this test, too, has been criticised – for its domain-specific nature (Taube, 1997), the subjectivity of its scoring protocol and its bias in favour of those proficient in writing (Adams, Whitlow, Stover & Johnson, 1996).

Another, more recent CT assessment that utilises an open-ended format is the Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment (HCTA; Halpern, 2010). The HCTA consists of 25 open-ended questions based on believable, everyday situations, followed by 25 specific questions that probe for the reasoning behind each answer. The multi-part nature of the questions makes it possible to assess the ability to use specific CT skills when the prompt is provided (Ku, 2009). The HCTA’s scoring protocol also provides comprehensible, unambiguous instructions for how to evaluate responses by breaking them down into clear, measurable components. Questions on the HCTA represent five categories of CT application: hypothesis testing (e.g. understanding the limits of correlational reasoning and how to know when causal claims cannot be made), verbal reasoning (e.g. recognising the use of pervasive or misleading language), argumentation (e.g. recognising the structure of arguments, how to examine the credibility of a source and how to judge one’s own arguments), judging likelihood and uncertainty (e.g. applying relevant principles of probability, how to avoid overconfidence in certain situations) and problem-solving (e.g. identifying the problem goal, generating and selecting solutions among alternatives).

Up until the development of the HCTA, I would have recommended the CCTST for measuring CT, despite its limitations. What’s nice about the CCTST is that it assesses the three core skills of CT: analysis, evaluation, and inference, which other scales do not (explicitly). So, if you were interested in assessing students’ sub-skill ability, this would be helpful. However, as we know, though CT skill performance is a sequence, it is also a collation of these skills – meaning that for any given problem or topic, each skill is necessary. By administrating an analysis problem, an evaluation problem and an inference problem, in which the student scores top marks for all three, it doesn’t guarantee that the student will apply these three to a broader problem that requires all three. That is, these questions don’t measure CT skill ability per se, rather analysis skill, evaluation skill and inference skill in isolation. Simply, scores may predict CT skill performance, but they don’t measure it.

What may be a better indicator of CT performance is assessment of CT application . As addressed above, there are five general applications of CT: hypothesis testing, verbal reasoning, argumentation, problem-solving and judging likelihood and uncertainty – all of which require a collation of analysis, evaluation, and inference. Though the sub-skills of analysis, evaluation, and inference are not directly measured in this case, their collation is measured through five distinct applications; and, as I see it, provides a 'truer' assessment of CT. In addition to assessing CT via an open-ended, short-answer format, the HCTA measures CT according to the five applications of CT; thus, I recommend its use for measuring CT.

However, that’s not to say that the HCTA is perfect. Though it consists of 25 open-ended questions, followed by 25 specific questions that probe for the reasoning behind each answer, when I first used it to assess a sample of students, I found that in setting up my data file, there were actually 165 opportunities for scoring across the test. Past research recommends that the assessment takes roughly between 45 and 60 minutes to complete. However, many of my participants reported it requiring closer to two hours (sometimes longer). It’s a long assessment – thorough, but long. Fortunately, adapted, shortened versions are now available, and it’s an adapted version that I currently administrate to assess CT. Another limitation is that, despite the rationale above, it would be nice to have some indication of how participants get on with the sub-skills of analysis, evaluation, and inference, as I do think there’s a potential predictive element in the relationship among the individual skills and the applications. With that, I suppose it is feasible to administer both the HCTA and CCTST to assess such hypotheses.

Though it’s obviously important to consider how assessments actually measure CT and the nature in which each is limited, the broader, macro-problem still requires thought. Just as conceptualisations of CT vary, so too does the reliability and validity of the different CT measures, which has led Abrami and colleagues (2008, p. 1104) to ask: “How will we know if one intervention is more beneficial than another if we are uncertain about the validity and reliability of the outcome measures?” Abrami and colleagues add that, even when researchers explicitly declare that they are assessing CT, there still remains the major challenge of ensuring that measured outcomes are related, in some meaningful way, to the conceptualisation and operational definition of CT that informed the teaching practice in cases of interventional research. Often, the relationship between the concepts of CT that are taught and those that are assessed is unclear, and a large majority of studies in this area include no theory to help elucidate these relationships.

In conclusion, solving the problem of consistency across CT conceptualisation, training, and measure is no easy task. I think recent advancements in CT scale development (e.g. the development of the HCTA and its adapted versions) have eased the problem, given that they now bridge the gap between current theory and practical assessment. However, such advances need to be made clearer to interested populations. As always, I’m very interested in hearing from any readers who may have any insight or suggestions!

Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Wade, A., Surkes, M. A., Tamim, R., & Zhang, D. (2008). Instructional interventions affecting critical thinking skills and dispositions: A stage 1 meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 1102–1134.

Adams, M.H., Whitlow, J.F., Stover, L.M., & Johnson, K.W. (1996). Critical thinking as an educational outcome: An evaluation of current tools of measurement. Nurse Educator, 21, 23–32.

Dwyer, C.P. (2017). Critical thinking: Conceptual perspectives and practical guidelines. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Dwyer, C.P., Hogan, M.J. & Stewart, I. (2014). An integrated critical thinking framework for the 21st century. Thinking Skills & Creativity, 12, 43-52.

Ennis, R.H., Millman, J., & Tomko, T.N. (1985). Cornell critical thinking tests. CA: Critical Thinking Co.

Ennis, R.H., & Weir, E. (1985). The Ennis-Weir critical thinking essay test. Pacific Grove, CA: Midwest Publications.

Facione, P. A. (1990a). The California critical thinking skills test (CCTST): Forms A and B;The CCTST test manual. Millbrae, CA: California Academic Press.

Facione, P.A. (1990b). The Delphi report: Committee on pre-college philosophy. Millbrae, CA: California Academic Press.

Halpern, D. F. (2003b). The “how” and “why” of critical thinking assessment. In D. Fasko (Ed.), Critical thinking and reasoning: Current research, theory and practice. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Halpern, D.F. (2010). The Halpern critical thinking assessment: Manual. Vienna: Schuhfried.

Ku, K.Y.L. (2009). Assessing students’ critical thinking performance: Urging for measurements using multi-response format. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 4, 1, 70- 76.

Taube, K.T. (1997). Critical thinking ability and disposition as factors of performance on a written critical thinking test. Journal of General Education, 46, 129-164.

Watson, G., & Glaser, E.M. (1980). Watson-Glaser critical thinking appraisal. New York: Psychological Corporation.

Christopher Dwyer, Ph.D., is a lecturer at the Technological University of the Shannon in Athlone, Ireland.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- ADEA Connect

- Communities

- Career Opportunities

- New Thinking

- ADEA Governance

- House of Delegates

- Board of Directors

- Advisory Committees

- Sections and Special Interest Groups

- Governance Documents and Publications

- Dental Faculty Code of Conduct

- ADEAGies Foundation

- About ADEAGies Foundation

- ADEAGies Newsroom

- Gies Awards

- Press Center

- Strategic Directions

- 2023 Annual Report

- ADEA Membership

- Institutions

- Faculty and Staff

- Individuals

- Corporations

- ADEA Members

- Predoctoral Dental

- Allied Dental

- Nonfederal Advanced Dental

- U.S. Federal Dental

- Students, Residents and Fellows

- Corporate Members

- Member Directory

- Directory of Institutional Members (DIM)

- 5 Questions With

- ADEA Member to Member Recruitment

- Students, Residents, and Fellows

- Information For

- Deans & Program Directors

- Current Students & Residents

- Prospective Students

- Educational Meetings

- Upcoming Events

- 2025 Annual Session & Exhibition

- eLearn Webinars

- Past Events

- Professional Development

- eLearn Micro-credentials

- Leadership Institute

- Leadership Institute Alumni Association (LIAA)

- Faculty Development Programs

- ADEA Scholarships, Awards and Fellowships

- Academic Fellowship

- For Students

- For Dental Educators

- For Leadership Institute Fellows

- Teaching Resources

- ADEA weTeach®

- MedEdPORTAL

Critical Thinking Skills Toolbox

- Resources for Teaching

- Policy Topics

- Task Force Report

- Opioid Epidemic

- Financing Dental Education

- Holistic Review

- Sex-based Health Differences

- Access, Diversity and Inclusion

- ADEA Commission on Change and Innovation in Dental Education

- Tool Resources

- Campus Liaisons

- Policy Resources

- Policy Publications

- Holistic Review Workshops

- Leading Conversations Webinar Series

- Collaborations

- Summer Health Professions Education Program

- Minority Dental Faculty Development Program

- Federal Advocacy

- Dental School Legislators

- Policy Letters and Memos

- Legislative Process

- Federal Advocacy Toolkit

- State Information

- Opioid Abuse

- Tracking Map

- Loan Forgiveness Programs

- State Advocacy Toolkit

- Canadian Information

- Dental Schools

- Provincial Information

- ADEA Advocate

- Books and Guides

- About ADEA Publications

- 2023-24 Official Guide

- Dental School Explorer

- Dental Education Trends

- Ordering Publications

- ADEA Bookstore

- Newsletters

- About ADEA Newsletters

- Bulletin of Dental Education

- Charting Progress

- Subscribe to Newsletter

- Journal of Dental Education

- Subscriptions

- Submissions FAQs

- Data, Analysis and Research

- Educational Institutions

- Applicants, Enrollees and Graduates

- Dental School Seniors

- ADEA AADSAS® (Dental School)

- AADSAS Applicants

- Health Professions Advisors

- Admissions Officers

- ADEA CAAPID® (International Dentists)

- CAAPID Applicants

- Program Finder

- ADEA DHCAS® (Dental Hygiene Programs)

- DHCAS Applicants

- Program Directors

- ADEA PASS® (Advanced Dental Education Programs)

- PASS Applicants

- PASS Evaluators

- DentEd Jobs

- Information For:

- Introduction

- Overview of Critical Thinking Skills

- Teaching Observations

- Avenues for Research

CTS Tools for Faculty and Student Assessment

- Critical Thinking and Assessment

- Conclusions

- Bibliography

- Helpful Links

- Appendix A. Author's Impressions of Vignettes

A number of critical thinking skills inventories and measures have been developed:

Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal (WGCTA) Cornell Critical Thinking Test California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory (CCTDI) California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST) Health Science Reasoning Test (HSRT) Professional Judgment Rating Form (PJRF) Teaching for Thinking Student Course Evaluation Form Holistic Critical Thinking Scoring Rubric Peer Evaluation of Group Presentation Form

Excluding the Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal and the Cornell Critical Thinking Test, Facione and Facione developed the critical thinking skills instruments listed above. However, it is important to point out that all of these measures are of questionable utility for dental educators because their content is general rather than dental education specific. (See Critical Thinking and Assessment .)

Table 7. Purposes of Critical Thinking Skills Instruments

Reliability and Validity

Reliability means that individual scores from an instrument should be the same or nearly the same from one administration of the instrument to another. The instrument can be assumed to be free of bias and measurement error (68). Alpha coefficients are often used to report an estimate of internal consistency. Scores of .70 or higher indicate that the instrument has high reliability when the stakes are moderate. Scores of .80 and higher are appropriate when the stakes are high.

Validity means that individual scores from a particular instrument are meaningful, make sense, and allow researchers to draw conclusions from the sample to the population that is being studied (69) Researchers often refer to "content" or "face" validity. Content validity or face validity is the extent to which questions on an instrument are representative of the possible questions that a researcher could ask about that particular content or skills.

Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal-FS (WGCTA-FS)

The WGCTA-FS is a 40-item inventory created to replace Forms A and B of the original test, which participants reported was too long.70 This inventory assesses test takers' skills in:

(a) Inference: the extent to which the individual recognizes whether assumptions are clearly stated (b) Recognition of assumptions: whether an individual recognizes whether assumptions are clearly stated (c) Deduction: whether an individual decides if certain conclusions follow the information provided (d) Interpretation: whether an individual considers evidence provided and determines whether generalizations from data are warranted (e) Evaluation of arguments: whether an individual distinguishes strong and relevant arguments from weak and irrelevant arguments

Researchers investigated the reliability and validity of the WGCTA-FS for subjects in academic fields. Participants included 586 university students. Internal consistencies for the total WGCTA-FS among students majoring in psychology, educational psychology, and special education, including undergraduates and graduates, ranged from .74 to .92. The correlations between course grades and total WGCTA-FS scores for all groups ranged from .24 to .62 and were significant at the p < .05 of p < .01. In addition, internal consistency and test-retest reliability for the WGCTA-FS have been measured as .81. The WGCTA-FS was found to be a reliable and valid instrument for measuring critical thinking (71).

Cornell Critical Thinking Test (CCTT)

There are two forms of the CCTT, X and Z. Form X is for students in grades 4-14. Form Z is for advanced and gifted high school students, undergraduate and graduate students, and adults. Reliability estimates for Form Z range from .49 to .87 across the 42 groups who have been tested. Measures of validity were computed in standard conditions, roughly defined as conditions that do not adversely affect test performance. Correlations between Level Z and other measures of critical thinking are about .50.72 The CCTT is reportedly as predictive of graduate school grades as the Graduate Record Exam (GRE), a measure of aptitude, and the Miller Analogies Test, and tends to correlate between .2 and .4.73

California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory (CCTDI)

Facione and Facione have reported significant relationships between the CCTDI and the CCTST. When faculty focus on critical thinking in planning curriculum development, modest cross-sectional and longitudinal gains have been demonstrated in students' CTS.74 The CCTDI consists of seven subscales and an overall score. The recommended cut-off score for each scale is 40, the suggested target score is 50, and the maximum score is 60. Scores below 40 on a specific scale are weak in that CT disposition, and scores above 50 on a scale are strong in that dispositional aspect. An overall score of 280 shows serious deficiency in disposition toward CT, while an overall score of 350 (while rare) shows across the board strength. The seven subscales are analyticity, self-confidence, inquisitiveness, maturity, open-mindedness, systematicity, and truth seeking (75).

In a study of instructional strategies and their influence on the development of critical thinking among undergraduate nursing students, Tiwari, Lai, and Yuen found that, compared with lecture students, PBL students showed significantly greater improvement in overall CCTDI (p = .0048), Truth seeking (p = .0008), Analyticity (p =.0368) and Critical Thinking Self-confidence (p =.0342) subscales from the first to the second time points; in overall CCTDI (p = .0083), Truth seeking (p= .0090), and Analyticity (p =.0354) subscales from the second to the third time points; and in Truth seeking (p = .0173) and Systematicity (p = .0440) subscales scores from the first to the fourth time points (76). California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST)

Studies have shown the California Critical Thinking Skills Test captured gain scores in students' critical thinking over one quarter or one semester. Multiple health science programs have demonstrated significant gains in students' critical thinking using site-specific curriculum. Studies conducted to control for re-test bias showed no testing effect from pre- to post-test means using two independent groups of CT students. Since behavioral science measures can be impacted by social-desirability bias-the participant's desire to answer in ways that would please the researcher-researchers are urged to have participants take the Marlowe Crowne Social Desirability Scale simultaneously when measuring pre- and post-test changes in critical thinking skills. The CCTST is a 34-item instrument. This test has been correlated with the CCTDI with a sample of 1,557 nursing education students. Results show that, r = .201, and the relationship between the CCTST and the CCTDI is significant at p< .001. Significant relationships between CCTST and other measures including the GRE total, GRE-analytic, GRE-Verbal, GRE-Quantitative, the WGCTA, and the SAT Math and Verbal have also been reported. The two forms of the CCTST, A and B, are considered statistically significant. Depending on the testing, context KR-20 alphas range from .70 to .75. The newest version is CCTST Form 2000, and depending on the testing context, KR-20 alphas range from .78-.84.77

The Health Science Reasoning Test (HSRT)

Items within this inventory cover the domain of CT cognitive skills identified by a Delphi group of experts whose work resulted in the development of the CCTDI and CCTST. This test measures health science undergraduate and graduate students' CTS. Although test items are set in health sciences and clinical practice contexts, test takers are not required to have discipline-specific health sciences knowledge. For this reason, the test may have limited utility in dental education (78).

Preliminary estimates of internal consistency show that overall KR-20 coefficients range from .77 to .83.79 The instrument has moderate reliability on analysis and inference subscales, although the factor loadings appear adequate. The low K-20 coefficients may be result of small sample size, variance in item response, or both (see following table).

Table 8. Estimates of Internal Consistency and Factor Loading by Subscale for HSRT

Professional Judgment Rating Form (PJRF)

The scale consists of two sets of descriptors. The first set relates primarily to the attitudinal (habits of mind) dimension of CT. The second set relates primarily to CTS.

A single rater should know the student well enough to respond to at least 17 or the 20 descriptors with confidence. If not, the validity of the ratings may be questionable. If a single rater is used and ratings over time show some consistency, comparisons between ratings may be used to assess changes. If more than one rater is used, then inter-rater reliability must be established among the raters to yield meaningful results. While the PJRF can be used to assess the effectiveness of training programs for individuals or groups, the evaluation of participants' actual skills are best measured by an objective tool such as the California Critical Thinking Skills Test.

Teaching for Thinking Student Course Evaluation Form

Course evaluations typically ask for responses of "agree" or "disagree" to items focusing on teacher behavior. Typically the questions do not solicit information about student learning. Because contemporary thinking about curriculum is interested in student learning, this form was developed to address differences in pedagogy and subject matter, learning outcomes, student demographics, and course level characteristic of education today. This form also grew out of a "one size fits all" approach to teaching evaluations and a recognition of the limitations of this practice. It offers information about how a particular course enhances student knowledge, sensitivities, and dispositions. The form gives students an opportunity to provide feedback that can be used to improve instruction.

Holistic Critical Thinking Scoring Rubric

This assessment tool uses a four-point classification schema that lists particular opposing reasoning skills for select criteria. One advantage of a rubric is that it offers clearly delineated components and scales for evaluating outcomes. This rubric explains how students' CTS will be evaluated, and it provides a consistent framework for the professor as evaluator. Users can add or delete any of the statements to reflect their institution's effort to measure CT. Like most rubrics, this form is likely to have high face validity since the items tend to be relevant or descriptive of the target concept. This rubric can be used to rate student work or to assess learning outcomes. Experienced evaluators should engage in a process leading to consensus regarding what kinds of things should be classified and in what ways.80 If used improperly or by inexperienced evaluators, unreliable results may occur.

Peer Evaluation of Group Presentation Form

This form offers a common set of criteria to be used by peers and the instructor to evaluate student-led group presentations regarding concepts, analysis of arguments or positions, and conclusions.81 Users have an opportunity to rate the degree to which each component was demonstrated. Open-ended questions give users an opportunity to cite examples of how concepts, the analysis of arguments or positions, and conclusions were demonstrated.

Table 8. Proposed Universal Criteria for Evaluating Students' Critical Thinking Skills

Aside from the use of the above-mentioned assessment tools, Dexter et al. recommended that all schools develop universal criteria for evaluating students' development of critical thinking skills (82).

Their rationale for the proposed criteria is that if faculty give feedback using these criteria, graduates will internalize these skills and use them to monitor their own thinking and practice (see Table 4).

- Application Information

- ADEA GoDental

- ADEA AADSAS

- ADEA CAAPID

- Events & Professional Development

- Scholarships, Awards & Fellowships

- Publications & Data

- Official Guide to Dental Schools

- Data, Analysis & Research

- Follow Us On:

- ADEA Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Website Feedback

- Website Help

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, performance assessment of critical thinking: conceptualization, design, and implementation.

- 1 Lynch School of Education and Human Development, Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA, United States

- 2 Graduate School of Education, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

- 3 Department of Business and Economics Education, Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany

Enhancing students’ critical thinking (CT) skills is an essential goal of higher education. This article presents a systematic approach to conceptualizing and measuring CT. CT generally comprises the following mental processes: identifying, evaluating, and analyzing a problem; interpreting information; synthesizing evidence; and reporting a conclusion. We further posit that CT also involves dealing with dilemmas involving ambiguity or conflicts among principles and contradictory information. We argue that performance assessment provides the most realistic—and most credible—approach to measuring CT. From this conceptualization and construct definition, we describe one possible framework for building performance assessments of CT with attention to extended performance tasks within the assessment system. The framework is a product of an ongoing, collaborative effort, the International Performance Assessment of Learning (iPAL). The framework comprises four main aspects: (1) The storyline describes a carefully curated version of a complex, real-world situation. (2) The challenge frames the task to be accomplished (3). A portfolio of documents in a range of formats is drawn from multiple sources chosen to have specific characteristics. (4) The scoring rubric comprises a set of scales each linked to a facet of the construct. We discuss a number of use cases, as well as the challenges that arise with the use and valid interpretation of performance assessments. The final section presents elements of the iPAL research program that involve various refinements and extensions of the assessment framework, a number of empirical studies, along with linkages to current work in online reading and information processing.

Introduction

In their mission statements, most colleges declare that a principal goal is to develop students’ higher-order cognitive skills such as critical thinking (CT) and reasoning (e.g., Shavelson, 2010 ; Hyytinen et al., 2019 ). The importance of CT is echoed by business leaders ( Association of American Colleges and Universities [AACU], 2018 ), as well as by college faculty (for curricular analyses in Germany, see e.g., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2018 ). Indeed, in the 2019 administration of the Faculty Survey of Student Engagement (FSSE), 93% of faculty reported that they “very much” or “quite a bit” structure their courses to support student development with respect to thinking critically and analytically. In a listing of 21st century skills, CT was the most highly ranked among FSSE respondents ( Indiana University, 2019 ). Nevertheless, there is considerable evidence that many college students do not develop these skills to a satisfactory standard ( Arum and Roksa, 2011 ; Shavelson et al., 2019 ; Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2019 ). This state of affairs represents a serious challenge to higher education – and to society at large.

In view of the importance of CT, as well as evidence of substantial variation in its development during college, its proper measurement is essential to tracking progress in skill development and to providing useful feedback to both teachers and learners. Feedback can help focus students’ attention on key skill areas in need of improvement, and provide insight to teachers on choices of pedagogical strategies and time allocation. Moreover, comparative studies at the program and institutional level can inform higher education leaders and policy makers.

The conceptualization and definition of CT presented here is closely related to models of information processing and online reasoning, the skills that are the focus of this special issue. These two skills are especially germane to the learning environments that college students experience today when much of their academic work is done online. Ideally, students should be capable of more than naïve Internet search, followed by copy-and-paste (e.g., McGrew et al., 2017 ); rather, for example, they should be able to critically evaluate both sources of evidence and the quality of the evidence itself in light of a given purpose ( Leu et al., 2020 ).

In this paper, we present a systematic approach to conceptualizing CT. From that conceptualization and construct definition, we present one possible framework for building performance assessments of CT with particular attention to extended performance tasks within the test environment. The penultimate section discusses some of the challenges that arise with the use and valid interpretation of performance assessment scores. We conclude the paper with a section on future perspectives in an emerging field of research – the iPAL program.

Conceptual Foundations, Definition and Measurement of Critical Thinking

In this section, we briefly review the concept of CT and its definition. In accordance with the principles of evidence-centered design (ECD; Mislevy et al., 2003 ), the conceptualization drives the measurement of the construct; that is, implementation of ECD directly links aspects of the assessment framework to specific facets of the construct. We then argue that performance assessments designed in accordance with such an assessment framework provide the most realistic—and most credible—approach to measuring CT. The section concludes with a sketch of an approach to CT measurement grounded in performance assessment .

Concept and Definition of Critical Thinking

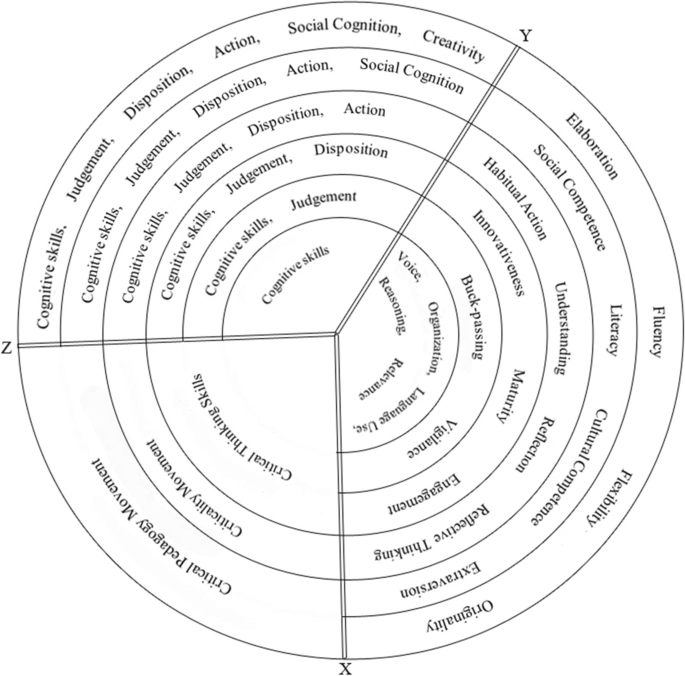

Taxonomies of 21st century skills ( Pellegrino and Hilton, 2012 ) abound, and it is neither surprising that CT appears in most taxonomies of learning, nor that there are many different approaches to defining and operationalizing the construct of CT. There is, however, general agreement that CT is a multifaceted construct ( Liu et al., 2014 ). Liu et al. (2014) identified five key facets of CT: (i) evaluating evidence and the use of evidence; (ii) analyzing arguments; (iii) understanding implications and consequences; (iv) developing sound arguments; and (v) understanding causation and explanation.

There is empirical support for these facets from college faculty. A 2016–2017 survey conducted by the Higher Education Research Institute (HERI) at the University of California, Los Angeles found that a substantial majority of faculty respondents “frequently” encouraged students to: (i) evaluate the quality or reliability of the information they receive; (ii) recognize biases that affect their thinking; (iii) analyze multiple sources of information before coming to a conclusion; and (iv) support their opinions with a logical argument ( Stolzenberg et al., 2019 ).

There is general agreement that CT involves the following mental processes: identifying, evaluating, and analyzing a problem; interpreting information; synthesizing evidence; and reporting a conclusion (e.g., Erwin and Sebrell, 2003 ; Kosslyn and Nelson, 2017 ; Shavelson et al., 2018 ). We further suggest that CT includes dealing with dilemmas of ambiguity or conflict among principles and contradictory information ( Oser and Biedermann, 2020 ).

Importantly, Oser and Biedermann (2020) posit that CT can be manifested at three levels. The first level, Critical Analysis , is the most complex of the three levels. Critical Analysis requires both knowledge in a specific discipline (conceptual) and procedural analytical (deduction, inclusion, etc.) knowledge. The second level is Critical Reflection , which involves more generic skills “… necessary for every responsible member of a society” (p. 90). It is “a basic attitude that must be taken into consideration if (new) information is questioned to be true or false, reliable or not reliable, moral or immoral etc.” (p. 90). To engage in Critical Reflection, one needs not only apply analytic reasoning, but also adopt a reflective stance toward the political, social, and other consequences of choosing a course of action. It also involves analyzing the potential motives of various actors involved in the dilemma of interest. The third level, Critical Alertness , involves questioning one’s own or others’ thinking from a skeptical point of view.

Wheeler and Haertel (1993) categorized higher-order skills, such as CT, into two types: (i) when solving problems and making decisions in professional and everyday life, for instance, related to civic affairs and the environment; and (ii) in situations where various mental processes (e.g., comparing, evaluating, and justifying) are developed through formal instruction, usually in a discipline. Hence, in both settings, individuals must confront situations that typically involve a problematic event, contradictory information, and possibly conflicting principles. Indeed, there is an ongoing debate concerning whether CT should be evaluated using generic or discipline-based assessments ( Nagel et al., 2020 ). Whether CT skills are conceptualized as generic or discipline-specific has implications for how they are assessed and how they are incorporated into the classroom.

In the iPAL project, CT is characterized as a multifaceted construct that comprises conceptualizing, analyzing, drawing inferences or synthesizing information, evaluating claims, and applying the results of these reasoning processes to various purposes (e.g., solve a problem, decide on a course of action, find an answer to a given question or reach a conclusion) ( Shavelson et al., 2019 ). In the course of carrying out a CT task, an individual typically engages in activities such as specifying or clarifying a problem; deciding what information is relevant to the problem; evaluating the trustworthiness of information; avoiding judgmental errors based on “fast thinking”; avoiding biases and stereotypes; recognizing different perspectives and how they can reframe a situation; considering the consequences of alternative courses of actions; and communicating clearly and concisely decisions and actions. The order in which activities are carried out can vary among individuals and the processes can be non-linear and reciprocal.

In this article, we focus on generic CT skills. The importance of these skills derives not only from their utility in academic and professional settings, but also the many situations involving challenging moral and ethical issues – often framed in terms of conflicting principles and/or interests – to which individuals have to apply these skills ( Kegan, 1994 ; Tessier-Lavigne, 2020 ). Conflicts and dilemmas are ubiquitous in the contexts in which adults find themselves: work, family, civil society. Moreover, to remain viable in the global economic environment – one characterized by increased competition and advances in second generation artificial intelligence (AI) – today’s college students will need to continually develop and leverage their CT skills. Ideally, colleges offer a supportive environment in which students can develop and practice effective approaches to reasoning about and acting in learning, professional and everyday situations.

Measurement of Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is a multifaceted construct that poses many challenges to those who would develop relevant and valid assessments. For those interested in current approaches to the measurement of CT that are not the focus of this paper, consult Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al. (2018) .

In this paper, we have singled out performance assessment as it offers important advantages to measuring CT. Extant tests of CT typically employ response formats such as forced-choice or short-answer, and scenario-based tasks (for an overview, see Liu et al., 2014 ). They all suffer from moderate to severe construct underrepresentation; that is, they fail to capture important facets of the CT construct such as perspective taking and communication. High fidelity performance tasks are viewed as more authentic in that they provide a problem context and require responses that are more similar to what individuals confront in the real world than what is offered by traditional multiple-choice items ( Messick, 1994 ; Braun, 2019 ). This greater verisimilitude promises higher levels of construct representation and lower levels of construct-irrelevant variance. Such performance tasks have the capacity to measure facets of CT that are imperfectly assessed, if at all, using traditional assessments ( Lane and Stone, 2006 ; Braun, 2019 ; Shavelson et al., 2019 ). However, these assertions must be empirically validated, and the measures should be subjected to psychometric analyses. Evidence of the reliability, validity, and interpretative challenges of performance assessment (PA) are extensively detailed in Davey et al. (2015) .

We adopt the following definition of performance assessment:

A performance assessment (sometimes called a work sample when assessing job performance) … is an activity or set of activities that requires test takers, either individually or in groups, to generate products or performances in response to a complex, most often real-world task. These products and performances provide observable evidence bearing on test takers’ knowledge, skills, and abilities—their competencies—in completing the assessment ( Davey et al., 2015 , p. 10).

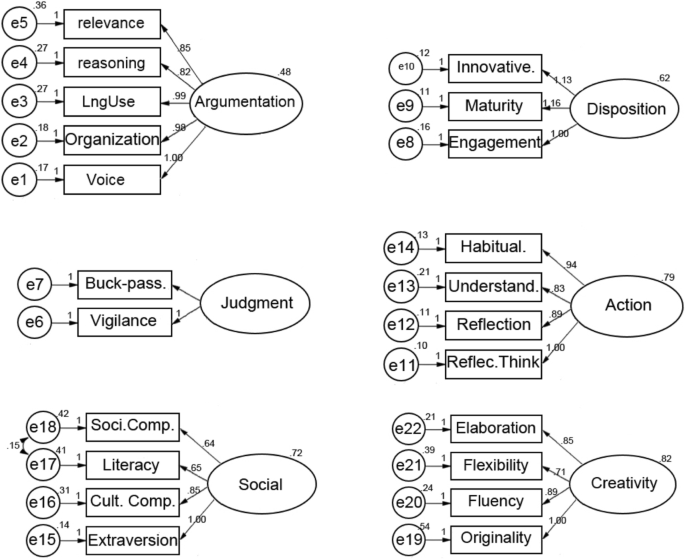

A performance assessment typically includes an extended performance task and short constructed-response and selected-response (i.e., multiple-choice) tasks (for examples, see Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia and Shavelson, 2019 ). In this paper, we refer to both individual performance- and constructed-response tasks as performance tasks (PT) (For an example, see Table 1 in section “iPAL Assessment Framework”).

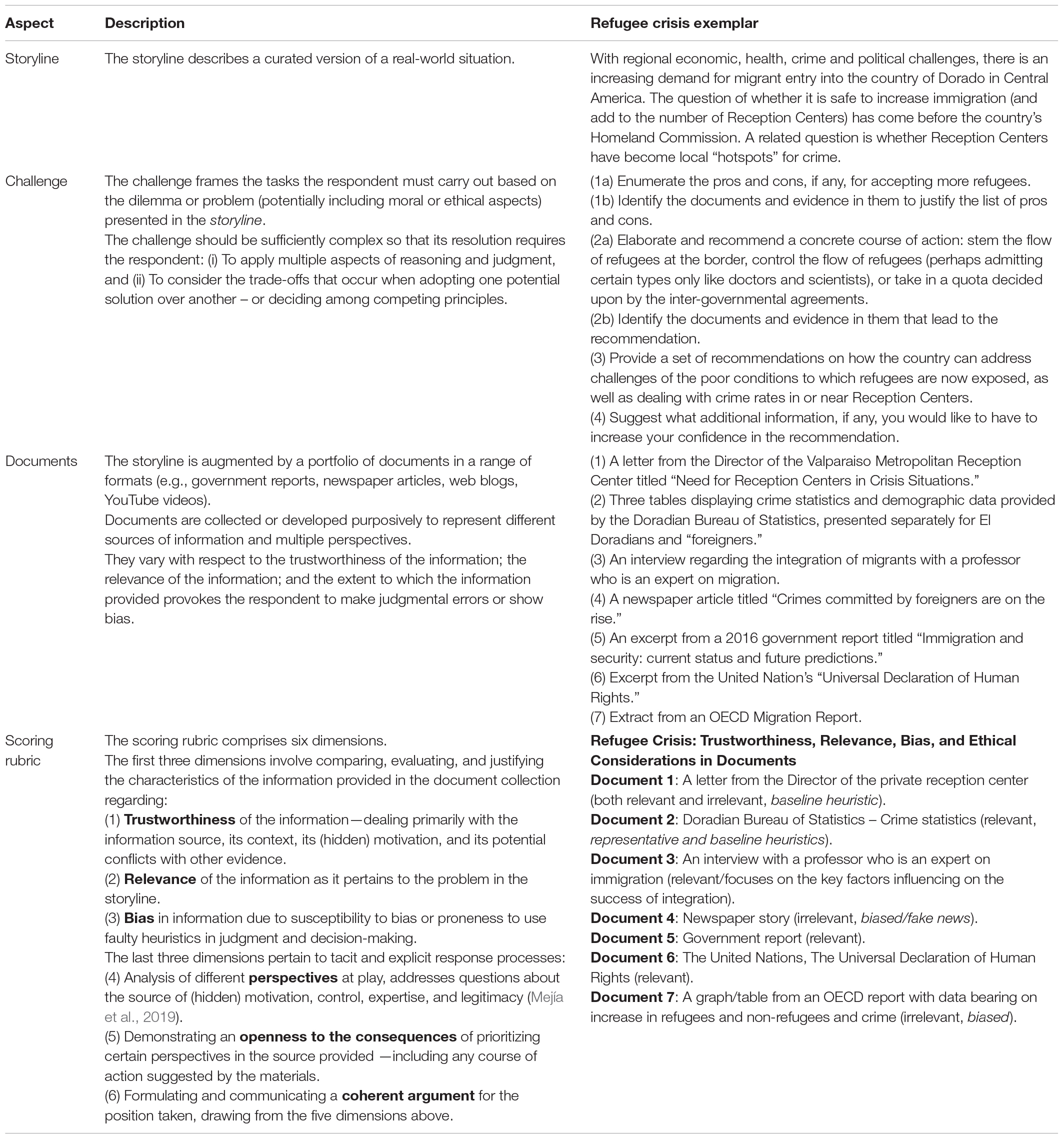

Table 1. The iPAL assessment framework.

An Approach to Performance Assessment of Critical Thinking: The iPAL Program

The approach to CT presented here is the result of ongoing work undertaken by the International Performance Assessment of Learning collaborative (iPAL 1 ). iPAL is an international consortium of volunteers, primarily from academia, who have come together to address the dearth in higher education of research and practice in measuring CT with performance tasks ( Shavelson et al., 2018 ). In this section, we present iPAL’s assessment framework as the basis of measuring CT, with examples along the way.

iPAL Background

The iPAL assessment framework builds on the Council of Aid to Education’s Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA). The CLA was designed to measure cross-disciplinary, generic competencies, such as CT, analytic reasoning, problem solving, and written communication ( Klein et al., 2007 ; Shavelson, 2010 ). Ideally, each PA contained an extended PT (e.g., examining a range of evidential materials related to the crash of an aircraft) and two short PT’s: one in which students either critique an argument or provide a solution in response to a real-world societal issue.

Motivated by considerations of adequate reliability, in 2012, the CLA was later modified to create the CLA+. The CLA+ includes two subtests: a PT and a 25-item Selected Response Question (SRQ) section. The PT presents a document or problem statement and an assignment based on that document which elicits an open-ended response. The CLA+ added the SRQ section (which is not linked substantively to the PT scenario) to increase the number of student responses to obtain more reliable estimates of performance at the student-level than could be achieved with a single PT ( Zahner, 2013 ; Davey et al., 2015 ).

iPAL Assessment Framework

Methodological foundations.

The iPAL framework evolved from the Collegiate Learning Assessment developed by Klein et al. (2007) . It was also informed by the results from the AHELO pilot study ( Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2012 , 2013 ), as well as the KoKoHs research program in Germany (for an overview see, Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2017 , 2020 ). The ongoing refinement of the iPAL framework has been guided in part by the principles of Evidence Centered Design (ECD) ( Mislevy et al., 2003 ; Mislevy and Haertel, 2006 ; Haertel and Fujii, 2017 ).

In educational measurement, an assessment framework plays a critical intermediary role between the theoretical formulation of the construct and the development of the assessment instrument containing tasks (or items) intended to elicit evidence with respect to that construct ( Mislevy et al., 2003 ). Builders of the assessment framework draw on the construct theory and operationalize it in a way that provides explicit guidance to PT’s developers. Thus, the framework should reflect the relevant facets of the construct, where relevance is determined by substantive theory or an appropriate alternative such as behavioral samples from real-world situations of interest (criterion-sampling; McClelland, 1973 ), as well as the intended use(s) (for an example, see Shavelson et al., 2019 ). By following the requirements and guidelines embodied in the framework, instrument developers strengthen the claim of construct validity for the instrument ( Messick, 1994 ).

An assessment framework can be specified at different levels of granularity: an assessment battery (“omnibus” assessment, for an example see below), a single performance task, or a specific component of an assessment ( Shavelson, 2010 ; Davey et al., 2015 ). In the iPAL program, a performance assessment comprises one or more extended performance tasks and additional selected-response and short constructed-response items. The focus of the framework specified below is on a single PT intended to elicit evidence with respect to some facets of CT, such as the evaluation of the trustworthiness of the documents provided and the capacity to address conflicts of principles.