- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- African Literatures

- Asian Literatures

- British and Irish Literatures

- Latin American and Caribbean Literatures

- North American Literatures

- Oceanic Literatures

- Slavic and Eastern European Literatures

- West Asian Literatures, including Middle East

- Western European Literatures

- Ancient Literatures (before 500)

- Middle Ages and Renaissance (500-1600)

- Enlightenment and Early Modern (1600-1800)

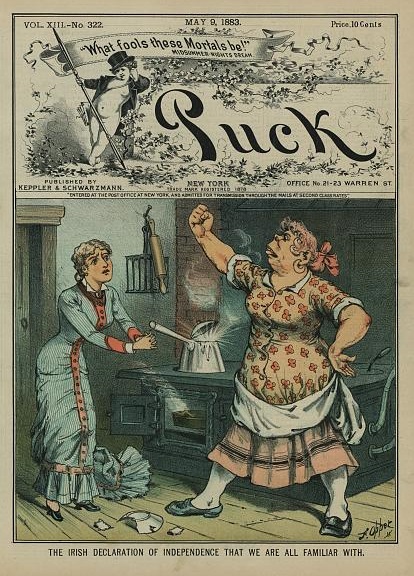

- 19th Century (1800-1900)

- 20th and 21st Century (1900-present)

- Children’s Literature

- Cultural Studies

- Film, TV, and Media

- Literary Theory

- Non-Fiction and Life Writing

- Print Culture and Digital Humanities

- Theater and Drama

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Appropriation.

- Julie Sanders Julie Sanders School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics, Newcastle University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.1049

- Published online: 29 July 2019

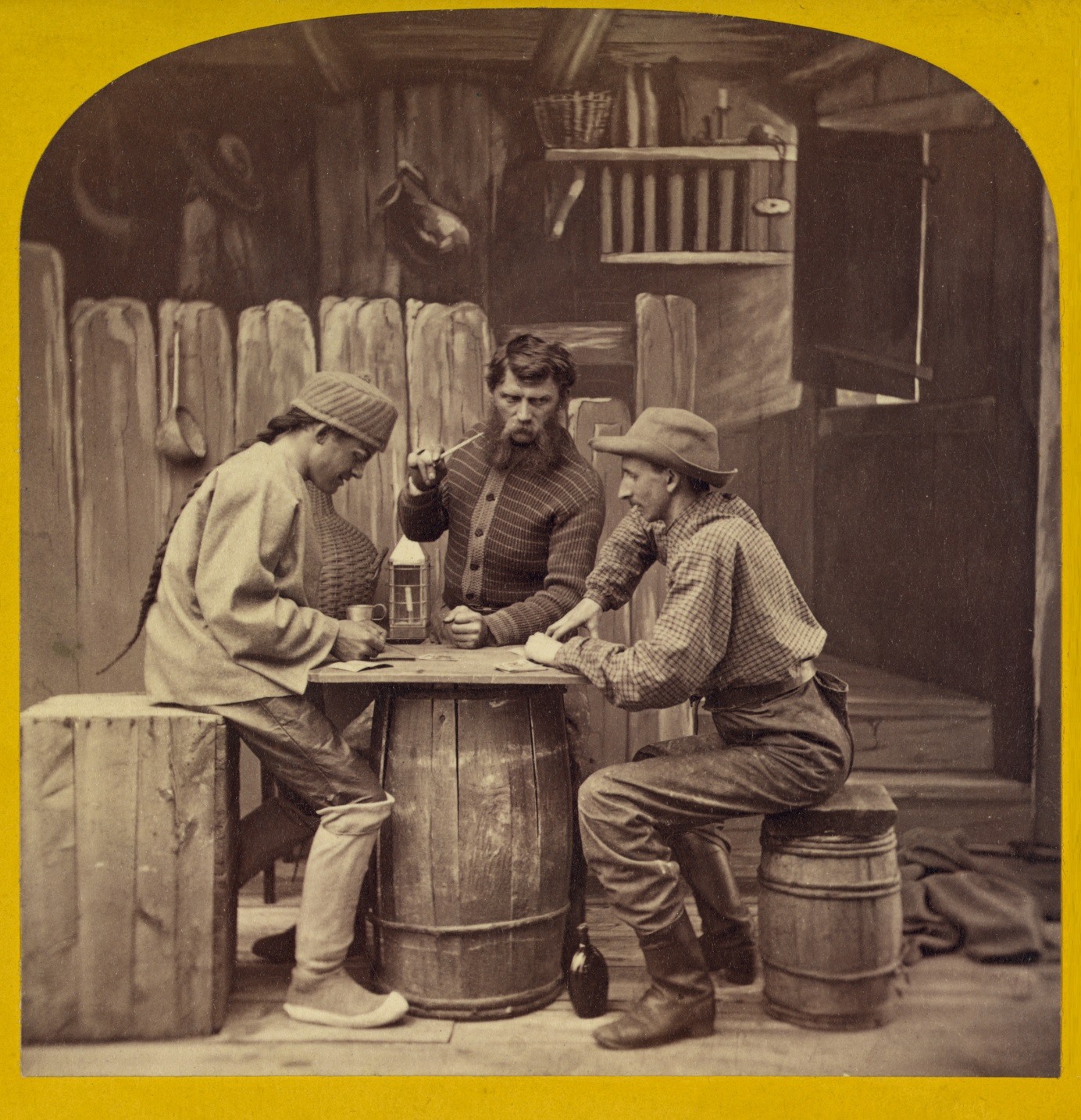

Literary texts have long been understood as generative of other texts and of artistic responses that stretch across time and culture. Adaptation studies seeks to explore the cultural contexts for these afterlives and the contributions they make to the literary canon. Writers such as William Shakespeare and Charles Dickens were being adapted almost as soon as their work emerged on stage or in print and there can be no doubt that this accretive aspect to their writing ensures their literary survival. Adaptation is, then, both a response to, a reinforcer of, and a potential shaper of canon and has had particular impact as a process through the multimedia and global affordances of the 20th century onwards, from novels to theatre, from poetry to music, and from film to digital content. The aesthetic pleasure of recognizing an “original” referenced in a secondary version can be considered central to the cultural power of literature and the arts.

Appropriation as a concept though moves far beyond intertextuality and introduces ideas of active critical commentary, of creative re-interpretation and of “writing back” to the original. Often defined in terms of a hostile takeover or possession, both the theory and practice of appropriation have been informed by the activist scholarship of postcolonialism, poststructuralism, feminism, and queer theory. Artistic responses can be understood as products of specific cultural politics and moments and as informed responses to perceived injustices and asymmetries of power. The empowering aspects of re-visionary writing, that has seen, for example, fairytales reclaimed for female protagonists, or voices returned to silenced or marginalized individuals and communities, through reconceived plots and the provision of alternative points of view, provide a predominantly positive history. There are, however, aspects of borrowing and appropriation that are more problematic, raising ethical questions about who has the right to speak for or on behalf of others or indeed to access, and potentially rewrite, cultural heritage.

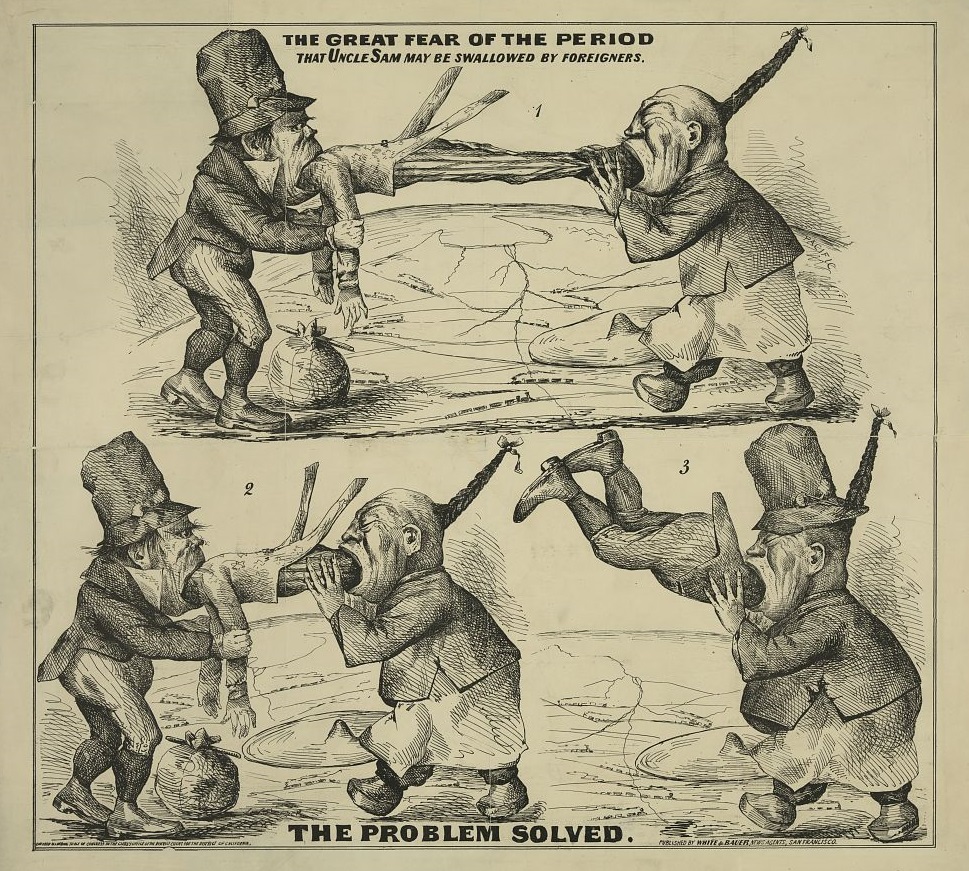

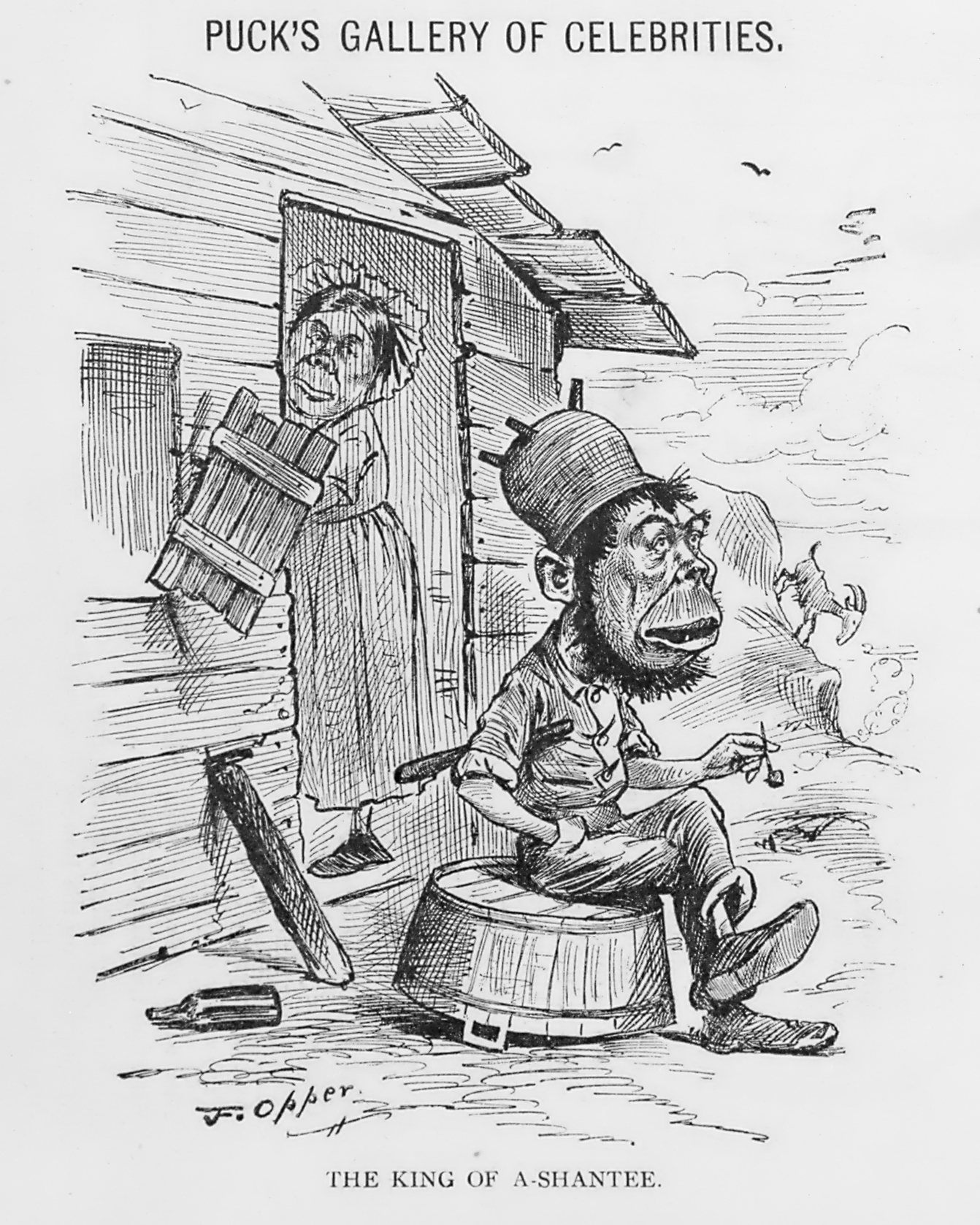

There has been debate in the arena of intercultural performance about the “right” of Western theatre directors to embed aspects of Asian culture into their work and in a number of highly controversial examples, the “right” of White artists to access the cultural references of First Nation or Black Asian and Minority Ethnic communities has been contested, leading in extreme cases to the agreed destruction of artworks. The concept of “cultural appropriation” poses important questions about the availability of artforms across cultural boundaries and about issues of access and inclusion but in turn demands approaches that perform cultural sensitivity and respect the question of provenance as well as intergenerational and cross-cultural justice.

- intertextuality

- cultural appropriation

- intercultural performance

- postcolonial

- remediation

- interdisciplinarity

- point of view

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Literature. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 17 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.180.204]

- 81.177.180.204

Character limit 500 /500

McCombs School of Business

- Español ( Spanish )

Videos Concepts Unwrapped View All 36 short illustrated videos explain behavioral ethics concepts and basic ethics principles. Concepts Unwrapped: Sports Edition View All 10 short videos introduce athletes to behavioral ethics concepts. Ethics Defined (Glossary) View All 58 animated videos - 1 to 2 minutes each - define key ethics terms and concepts. Ethics in Focus View All One-of-a-kind videos highlight the ethical aspects of current and historical subjects. Giving Voice To Values View All Eight short videos present the 7 principles of values-driven leadership from Gentile's Giving Voice to Values. In It To Win View All A documentary and six short videos reveal the behavioral ethics biases in super-lobbyist Jack Abramoff's story. Scandals Illustrated View All 30 videos - one minute each - introduce newsworthy scandals with ethical insights and case studies. Video Series

Concepts Unwrapped UT Star Icon

Appropriation & Attribution

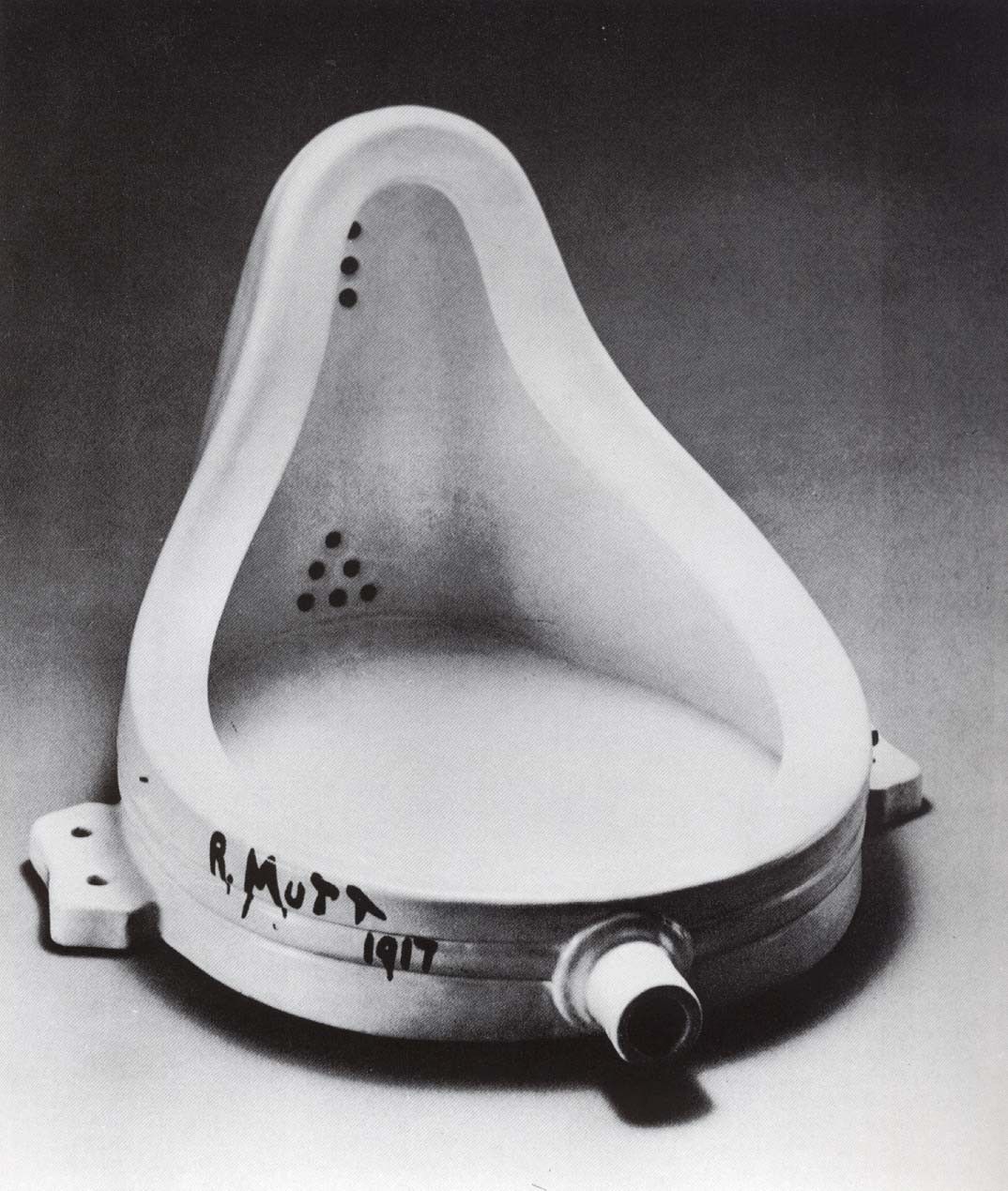

Attribution is giving credit where credit is due. Appropriation is the complex borrowing of ideas, images, symbols, sounds, and identity from others.

Discussion Questions

1. What is the relationship between attribution and appropriation? How are they similar? How are they different?

2. The video acknowledges that artistic progress may not be possible without incorporating important developments from the past. Do you agree? Why or why not?

3. How can artists use others’ creative works in an ethical manner? When is appropriation unethical?

4. Case law suggests that someone cannot claim intellectual property rights after throwing away the original work. Do you agree with this position? Why or why not?

5. Have you ever pirated or copied works protected by copyright? What harms did you cause? Do you feel you were ethically justified to do so? Why or why not?

6. Think of an example of something you consider to be a “rip-off” and something you think is an innovative repurposing of another’s work. What makes them different? Could your conclusions be shaped by your own interests?

7. Fair use is a doctrine that allows for limited use of copyrighted materials without acquiring permission, for purposes such as teaching, journalism, parody, or critique. Do you agree with these parameters? Are there other instances that should constitute fair use?

8. According to the terms and conditions of YouTube, the company says it may use any works uploaded as it chooses, but will not claim credit for creation of the piece. Do you think this is ethically permissible? Why or why not? Would you feel comfortable with YouTube using a video you created in an advertisement for the company?

Case Studies

Blurred Lines of Copyright

Marvin Gaye’s Estate won a lawsuit against Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams for the hit song “Blurred Lines,” which had a similar feel to one of his songs.

Appropriating “Hope”

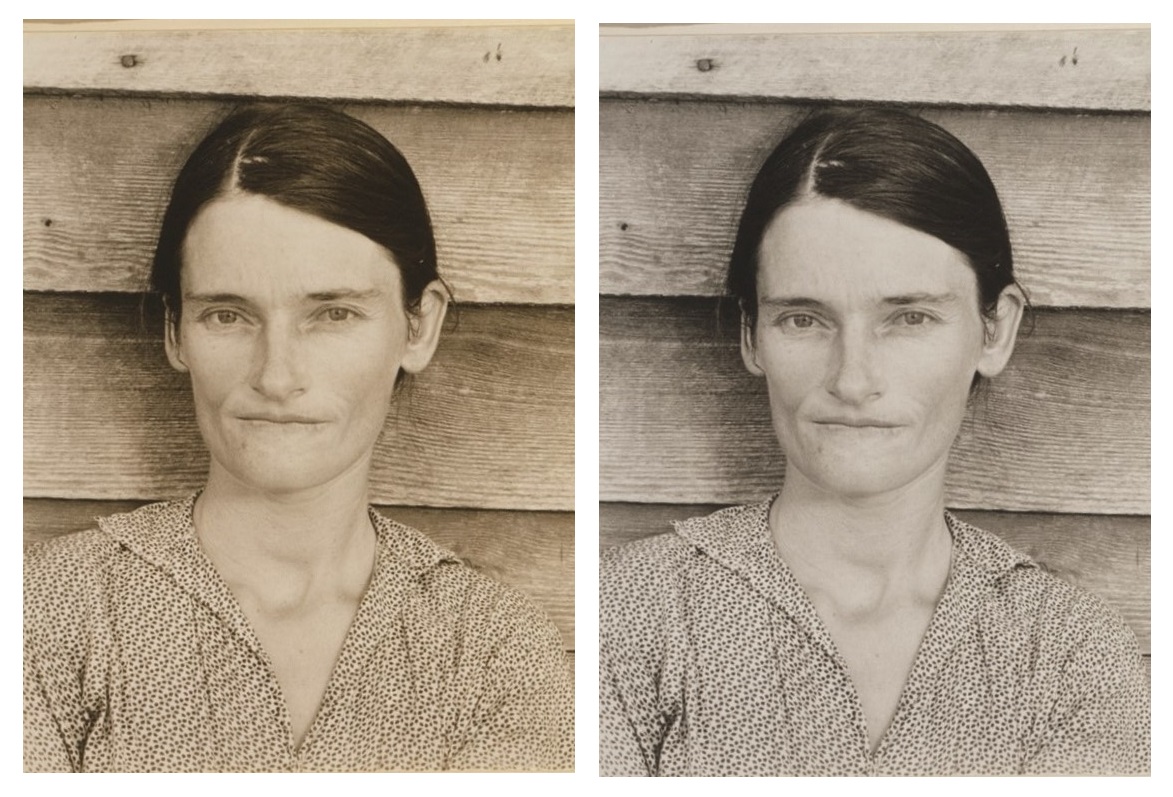

Fairey’s portrait of Barack Obama raised debate over the extent to which an artist can use and modify another’s artistic work, yet still call it one’s own.

Christina Fallin: “Appropriate Culturation?”

After Fallin posted a picture of herself wearing a Plain’s headdress on social media, uproar emerged over cultural appropriation and Fallin’s intentions.

Teaching Notes

This video introduces the general ethics concepts of appropriation and attribution. Attribution is giving credit where credit is due. Appropriation is the complex borrowing of ideas, images, symbols, sounds, and identity from others.

Cultural appropriation is the use of elements of one culture by another culture, such as music, dress, imagery, or behavior and ceremony. To learn more about this in relation to stereotypes and media representations watch Representation .

Issues of artistic and intellectual attribution are often related to copyright laws and intellectual property policies. For a better understanding of the relationship between law and ethics, watch Legal Rights & Ethical Responsibilities .

Appropriating or using others’ work without proper attribution can cause reputational and financial harm, among others. To learn more about various types of harm, watch Causing Harm .

The case studies covered on this page explore issues of cultural appropriation, artistic appropriation, and legal and artistic attribution. “Christina Fallin: “Appropriate Culturation?”” examines the intentions of a musician after she posted a controversial picture on social media and was criticized of cultural appropriation. “Appropriating “Hope”” details the trial over Shepard Fairey’s portrait of Barack Obama and the extent to which an artist can use and modify another’s artistic work. ““Blurred Lines” of Copyright” examines the legal debates over proper attribution in the Marvin Gaye Estate’s lawsuit against Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams.

Terms defined in our ethics glossary that are related to the video and case studies include: diffusion of responsibility, integrity, justice, morals, self-serving bias, and values.

For more information on concepts covered in this and other videos, as well as activities to help think through these concepts, see Deni Elliott’s workbook Ethical Challenges: Building an Ethics Toolkit , which may be downloaded for free as a PDF. This workbook explores what ethics is and what it means to be ethical, offering readers a variety of exercises to identify their own values and reason through ethical conflicts.

Additional Resources

Askegaard, Søren, and Giana M. Eckhardt. 2012. “Glocal Yoga: Re-appropriation in the Indian Consumptionscape.” Marketing Theory 12 (1): 45-60.

Berson, Josh. 2010. “Intellectual Property and Cultural Appropriation.” Reviews in Anthropology 39 (3): 201-228.

Craig, David. 2006. “Description and Attribution.” In The Ethics of the Story: Using Narrative Techniques Responsibly in Journalism . Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing.

Lessig, Lawrence. 2008. Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy . New York: The Penguin Press.

Luke, Belinda, and Kate Kearins. 2012. “Attribution of Words versus Attribution of Responsibilities: Academic Plagiarism and University Practice.” Organization 19 (6): 881-889.

Merryman, John Henry, Albert E. Elsen, and Stephen K. Urice. 2014. Law, Ethics, and the Visual Arts . Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands: Kluwer Law International.

Ursin, Reanna A. 2014. “Cultural Appropriation for Mainstream Consumption: The Musical Adaptation of Dessa Rose .” Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature 47 (1): 91-109.

Young, James O., and Conrad G. Brunk (Editors). 2009. The Ethics of Cultural Appropriation . Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Transcript of Narration

Written and Narrated by

Deni Elliott , Ph.D., M.A. Department of Journalism & Media Studies College of Arts and Sciences The University of South Florida at St. Petersburg

“As young children, we learned that everyone has the right to control the use of their property. Keep it, share it, give it away; it seemed that simple. But as adults, we find ourselves trying to navigate through physical and virtual worlds, where issues of intellectual property and ownership are much more complex. Much of what is ethical and unethical in the area of intellectual property has to do with following the law. While laws governing appropriation and attribution are struggling to keep up and add clarity in our rapidly evolving world, ethical analysis can help guide the way.

Attribution means giving credit where credit is due. In theory, the author of any published work has a right to control how his or her intellectual property is used. But in practice, most people click agree when signing on to websites such as YouTube without ever being aware that they’re signing over their rights to their material to the corporation that owns the site.

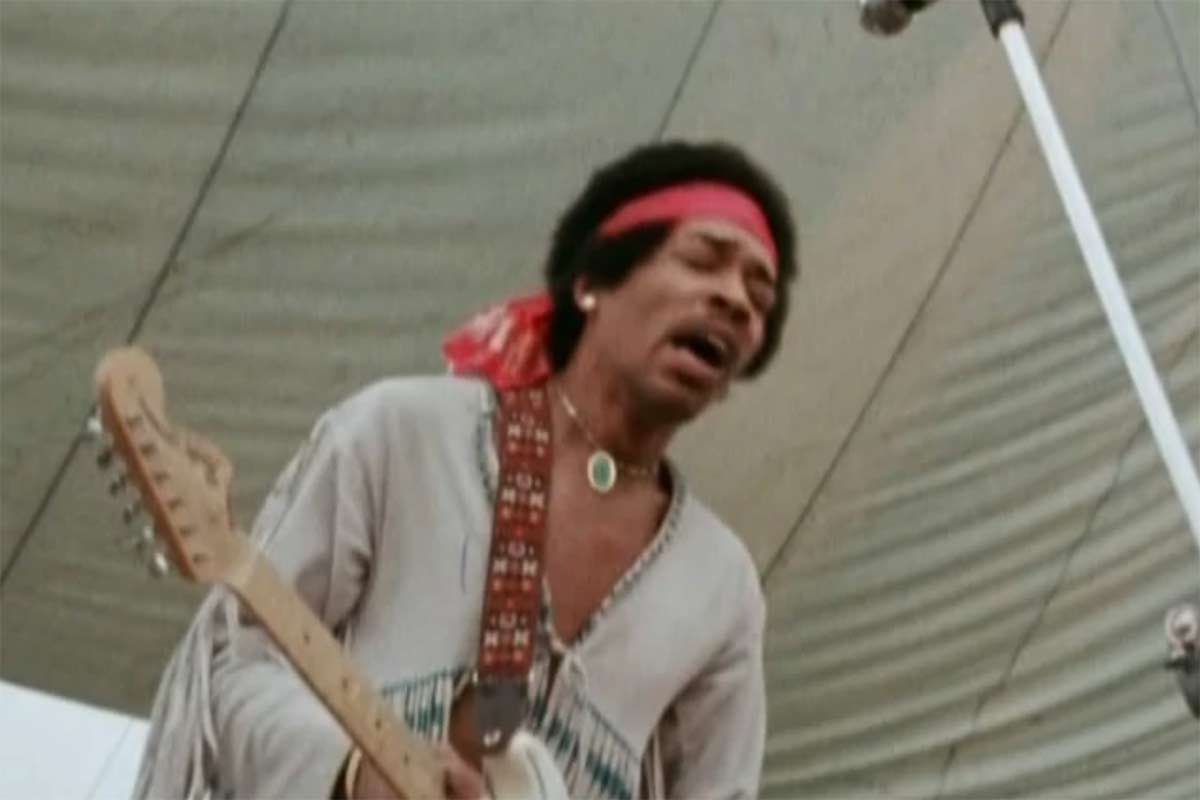

We all know that we’re not supposed to plagiarize our papers. But what about artists or musicians who learn their craft by copying famous predecessors? Would we call that stealing? Or influence?

Music professor and computer scientist David Cope created a computer program that produces “original” compositions in the style of Mozart or Bach, for instance, but it’s not. Two CDs have been produced and sold with no legal action taken because the copyrights to the individual works expired long ago.

In another case, Composer John Oswald created sound collages, using samples of previously recorded works. He claimed that the sound collages were original compositions. He listed all his sources, but did not get permissions to use them. Record companies filed lawsuits, and ultimately, unsold copies of his albums were destroyed.

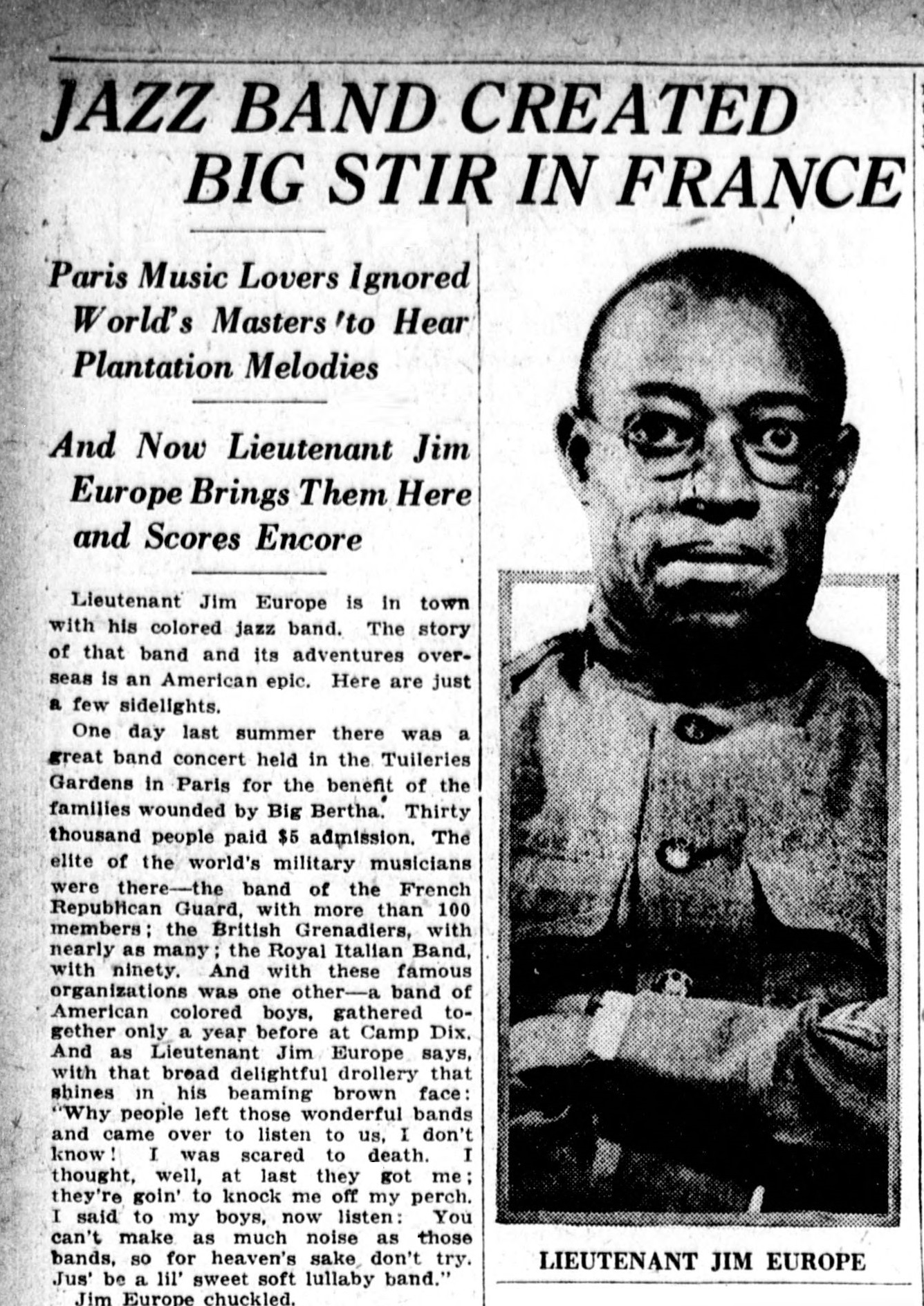

Ethically speaking, using others’ intellectual property for one’s own gain without permission is stealing. But appropriation is more complex. Appropriation can mean borrowing ideas, images, symbols, sounds and identity from others. Many would argue that progress in art, music, and architecture wouldn’t even be possible without incorporating important artistic developments of the past.

Sometimes appropriation is ethically permissible and other times not. For example, many of our government buildings and banks have appropriated ancient Greek architectural features, such as columns and capitals, to project images we associate with democracy, wealth, and freedom. On the other hand, controversial instances of cultural appropriation abound, such as the NFL’s use of Native American symbols like the logo for the Washington Redskins.

When it comes to appropriation and attribution, the laws may still be murky, but ethical behavior doesn’t have to be. If what you want to use doesn’t belong to you, then use it only in ways that the owner permits. If it’s impossible to ask for permission, then ask yourself how you would want the creation to be used or attributed if it were your own. And if ownership itself is the subject of debate, then the use should be subjected to a systematic moral analysis to determine what harms the appropriation might cause and whether they are justified.”

Stay Informed

Support our work.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- BSA Prize Essays

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish with BJA?

- About The British Journal of Aesthetics

- About the British Society of Aesthetics

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 2. categories of cultural appropriation, 3. what is minor literature, 4. intertextuality and appropriation, 5. the ethics and aesthetics of cultural appropriation.

- < Previous

The Ethics and Aesthetics of Intertextual Writing: Cultural Appropriation and Minor Literature

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Paul Haynes, The Ethics and Aesthetics of Intertextual Writing: Cultural Appropriation and Minor Literature, The British Journal of Aesthetics , Volume 61, Issue 3, July 2021, Pages 291–306, https://doi.org/10.1093/aesthj/ayab001

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Cultural appropriation, as both concept and practice, is a hugely controversial issue. It is of particular importance to the arts because creativity is often found at the intersection of cultural boundaries. Much of the popular discourse on cultural appropriation focusses on the commercial use of indigenous or marginalized cultures by mainstream or dominant cultures. There is, however, growing awareness that cultural appropriation is a complicated issue encompassing cultural exchange in all its forms. Creativity emerging from cultural interdependence is far from a reciprocal exchange. This insight indicates that ethical and political implications are at stake. Consequently, the arts are being examined with greater attention in order to assess these implications. This article will focus on appropriation in literature, and examine the way appropriative strategies are being used to resist dominant cultural standards. These strategies and their implications will be analyzed through the lens of Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of minor literature.

Any genre is never more interesting than when being broken in some way…not what the story is about but its very existence. ( Moore, 2017 )

Both words in the phrase ‘cultural appropriation’ are ideologically loaded, which is further intensified as they become merged into a single concept. This concept is controversial and fundamentally political—as, indeed, is culture itself.

Culture is necessarily shared. It is also continually undergoing transformation, not least through relationships with other cultures or in addressing alternative values to those on which it is structured (see Kulchyski, 1997 ; Matthes, 2016 ; Kramvig and Flemmen, 2019 ). The implications for neatly defining culture are clear:

[T]he definition of culture has a contested history. Not only do cultures change over time, influenced by economic and political forces, climatic and geographic changes, and the importation of ideas, but the very notion of culture itself also is dynamically changing over time and space – the product of ongoing human interaction. This means that we accept the term as ambiguous and suggestive rather than as analytically precise. ( Baldwin et al., 2008 , p. 23)

The interaction of practices and values from different cultures is, therefore, never a neutral process. Drawing out the ethical and political implications of cultural exchange is thus a challenge. This challenge has been addressed in a number of ways, including categorizing different types of exchange ( Rogers, 2006 ), categorizing the object of exchange ( Young, 2000 , 2005 ) or identifying types of ethical consequences of cultural exchange practices themselves ( Heyd, 2003 ). This article will take a different approach and evaluate cultural exchange within the arts along a fault-line that divides exchange practices between i) appropriation that serves the interests of existing cultural inequalities and ii) appropriative practices used to challenge existing modes of dominance. The focus of the evaluation will be literature—in particular, the ethics and aesthetics of intertextual writing as identified through the lens of minor literature, a concept developed by Deleuze and Guattari (1986) . The insights obtained by using the minor literature concept will help to enrich the concept of cultural appropriation and assess its ethical implications. In particular, it helps to clarify the relevance of status, advantage and opportunity as being asymmetrical features of cultural exchange, and it can be applied to identify strategies to address these asymmetries. Evaluating appropriative strategies within a variety of intertextual literary settings will thus enable these insights to be examined and applied to other cases. Before this evaluation can commence, the notion of cultural appropriation needs to be examined in a little more detail.

Cultural appropriation can be approached in different ways. The variety of different practices classified as instances of cultural appropriation means that stipulating a definition is problematic (see Jackson, 2019 ). Helene Shugart (1997) observes that appropriation occurs when features perceived to belong to a specific culture are used to further the interest of those not sharing that cultural heritage:

Any instance in which a group borrows or imitates the strategies of another—even when the tactic is not intended to deconstruct or distort the other’s meanings and experiences—thus would constitute appropriation. ( Shugart, 1997 , pp. 210–211)

Expanding on this definition is helpful in positioning the concept at this initial stage. In this way, if culture is defined (even if imprecisely) in terms of the complex network of practices, knowledge and beliefs that emerge and are shared through social interaction (see Baldwin et al., 2008 , pp. 23–24), then cultural appropriation can thus be characterized as an unauthorized use or imitation of characteristics, symbols, artefacts, genres, rituals or technologies derived from these networks, but removed from their cultural setting and original purpose (see also Rogers, 2006). Characterized this way, a number of relevant themes and practices can be identified—although as an emerging concept, presenting a systematic approach to these themes and practices presents a challenge. Peter Kulchyski warns of attempting to apply an exhaustive or systematic schematic of categories or instances (Kulchyski, 1997); nevertheless, there are some common themes of relevance to the arts, including the following categories: cross-cultural aesthetic appreciation ( Heyd, 2003 ); the fictional (re)production of marginalized voices ( Moraru, 2000 ); appropriation in popular visual culture ( Wetmore, 2000 ); reciprocal creative exchange ( Sinkoff, 2000 ; Goldstein-Gidoni, 2003 ; Dong-Hoo, 2006 ); transculturation in the arts ( Lionnet, 1992 ) and performance and protest ( Hoyes, 2004 ; Galindo and Medina, 2009 ; Carriger, 2018 ). The article will return to some of these topics shortly but will firstly address attempts to provide structure to the patterns observed within this diversity.

Richard Rogers (2006) has developed a framework with which to position the concept of cultural appropriation based on four categories: exchange, dominance, exploitation and transculturation. The different categories are used to evaluate the ethics of different types of cultural exchange and are constituted by social, political and economic contexts such as considerations of power relations between cultures, hegemonic concerns, resistance and the hybrid nature of cultural development. Cultural exchange is characterized by reciprocal cultural influence in the absence of specific differences in power relations. Cultural dominance occurs when features derived from a dominant culture are imposed on individuals from a subordinate culture. Cultural exploitation occurs when people from a dominant culture take or imitate features or entities from a subordinate culture without permission or without providing compensation. Finally, transculturation is categorized as a hybridization of different cultural elements from multiple sources, particularly where the product of the relationship represents a new cultural form.

Rogers describes the logic and relevance of these categories in detail (see Rogers, 2006 , pp. 479–497), providing a helpful series of archetypes to assess the conditions that predetermine exchange relationships. Despite these strengths, this approach has its limitations, particularly in relation to the arts. Rogers’ assumption of the operation of a binary structure of power as a force of cultural imposition (or the evasion of ‘fair compensation’) both simplifies the systemic aspects of power, and risks presenting culture in an essentialist or reified way. As a framework, it is powerful in assessing explicitly commercial relationships but less insightful in evaluating more nuanced creativity emerging within cultural exchange.

A contrasting approach is to place less emphasis on the nature of the cultural encounter and more on the entities enabled or exchanged through the cross-cultural encounter. The framework developed by James Young, for example, distinguishes between different classes of entities appropriated. Young identifies five categories (material appropriation; non-material appropriation; stylistic appropriation; motif appropriation and subject appropriation). In contrast with Rogers’ approach, Young’s categories focus more explicitly on themes relevant to artistic production. Material appropriation involves transferring ownership of a tangible object from members of one culture (those creating the entity) to members of another culture (those appropriating the entity). Non-material appropriation occurs through the reproduction of non-tangible works by members of another culture. Stylistic appropriation occurs when members of one culture use stylistic elements used by or in common with the works of another culture. Motif appropriation occurs when the influence of another culture is considerable in creating a new work rather than the new work being created in the same style as the works of that culture. Subject appropriation concerns cases when members of one culture represent members or aspects of another culture ( Young, 2000 , pp. 302–303). The framework is further enhanced by considering the offensiveness of contrasting examples and mitigated by factors such as context, social value and freedom of expression. The strength of Young’s categorization is to give clarity to the many different ways in which exchange risks being objectionable, particularly in the creation and circulation of artistic technique, art and artefacts, and in the broader context of authenticity, representation, cultural heritage and intellectual property rights. Young’s approach is also limited by this focus. By exposing the conditions relevant to the framing of cultural appropriation, Young’s categorization also demonstrates the inadequacy of attempting to unify the multiplicity of cultural encounters and boundaries (and the commodification of cultural content) through the reception of typically dissonant or totemic artefacts. Focussing on exceptional exchange patterns (hawking/hoarding stolen relics, stylistic plagiarism, stereotyping, carnivalesque profanation, etc.) means Young’s approach fails to focus on the more pressing implications of cultural exchange and broader issues, such as racism or rights based on heritage (see, for example, Heyd, 2003 ; Jackson, 2019 , pp. 1–9). In addition, Young’s way of framing cultural interaction reveals exactly the type of appropriative representation—for example, addressing who determines consent or which individuals are authentically ‘insiders’—that it was invoked to question (see Matthes, 2016 ). It also assumes a discourse of victimhood that is both oversimplified and ‘justifiably unacceptable to many indigenous people’ ( Cuthbert, 1998 , p. 257).

A third approach to categorize forms of appropriation and exchange is presented by Thomas Heyd (2003) . Heyd’s focus has the potential to offer additional insight relevant to this article, as it is derived from research on art and aesthetics ( Heyd, 2003 , p. 37). Heyd emphasizes the need to distinguish between three categories of risk that occur with acts of appropriation. The first risk is moral and occurs when appropriation is unauthorized and threatens the income or rights of disadvantaged or indigenous groups or artists. The second risk is cognitive and occurs when a different value context is imposed on a creative process that threatens the authenticity of the cultural artefacts (and culture) appropriated. The third risk is ontological and occurs through a misrepresented portrayal of the culture producing the appropriated entities, which ultimately threatens their cultural identity. (see Heyd, 2003 , pp. 37–38). There is, however, a fourth risk—one with which Heyd seems unaware, but for which his approach is complicit. This is the risk of defining the creativity of artists in terms of their heritage, namely interpreting a work of art by an artist from a marginalized culture predominantly in terms of their marginalized status irrespective of its relevance to their art . This deterministic coupling of creativity to heritage is problematic for a variety of reasons. The most obvious objection is that it limits the creative work to an imposed standard, often in terms of a stereotypical representation of its marginalized origin, or dictating the criteria for authenticity. The disqualification of Genevieve Nnaji’s film Lionheart from the 2020 Academy Awards ‘International Feature Film’ category for having insufficient Igbo dialogue (and too much English) exemplifies this final point well, regardless that the film reflects an authentic contextual use of different languages for business purposes in Nigeria, which is itself a prominent theme of the film ( Whitten, 2019 ). Viewed in terms of the authenticity that such creativity ‘owes’ to its marginalized cultural patterns additionally removes the potential for the intended subversion of such standards. Removing opportunities to resist or subvert prevailing standards is another aspect of cultural domination, appropriating or closing down ‘strategies of discourse and public performances of culture beyond the stultifying binaries of right/wrong or appreciation/appropriation’ ( Carriger, 2018 , pp. 165), strategies examined later in this article.

An alternative approach is to address the growing body of case studies that present the scope of cultural appropriation in its broadest form and position them in terms of how they reproduce or resist forms of cultural dominance. This will also help to identify strategies—such as performance, redeployment, learning, engagement or re-identification—able to serve the purpose of resistance or subversion, or to produce lines of flight to address marginalization, exclusion, invisibility and powerlessness. What potentially unites such examples is that they might serve to provide evidence of the operation of cultural expropriation —not merely to resist cultural domination or address establishments of power, but to develop mechanisms of cultural innovation available to empower even the most marginalized of social groups. For this reason, there is the need for a revised perspective that distinguishes between processes of cultural appropriation and strategies of cultural expropriation, and to explain their relevance and implications. To do so, the article will now turn to this theme and attempt to redefine the relationship underpinning the revised perspective in terms of Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of minor literature.

To answer the question that Deleuze and Guattari ask—‘What is minor literature?’—is to address the broader questions implied by the powers of becoming that it reveals. More specifically, the minor literature concept will address the question of how to construct a form of writing from a language that is not one’s own. In order to address the challenges implied by cultural appropriation, the minor literature concept will also need to be linked to the aesthetic and ethical contexts for which cultural narratives, myths and representation are key themes—issues to be examined in the final section of this article. To address this topic and make these connections more explicit, it will be helpful to begin with Deleuze and Guattari’s framing of the distinction between minoritarian and majoritarian, through which the minor literature concept is positioned.

Minoritarian in this sense is not an indicator of (numerical) minority or ethnic minority but is characterized in its difference with an embodiment or approximation of a standard that defines a majority. It is this difference from the abstract (majority-serving) standard that separates, and sets apart, the minority. Majority assumes a state of power and domination as the standard measure ( Deleuze and Guattari, 1988 , p. 105). An example of such a standard is the requirement of membership of the Académie Française in order to create ‘official’ academic art in late nineteenth-century France. Membership offered prestige and a position, but required adherence to its conventions (encompassing majority, i.e. White, male, elitist, values). Such faithfulness to these conventions produced art now perceived to be conservative, bourgeois, contrived and lacking in innovation. In a similar way, in adhering to prevailing conventions, the majoritarian character is a constant and homogeneous system. In this regard, majority is expressive of identity (i.e. inert and invariable). This is in contrast with minorities, which serve as subsystems dependent on, but invisible within, the system. Minoritarian, in this sense, is seen by Deleuze and Guattari as ‘a potential, creative and created, becoming’ ( Deleuze and Guattari, 1988 , pp. 105–106). To operationalize this relationship, Deleuze and Guattari go beyond a majority/minority duality, adding a third category or state: ‘becoming-minor’—namely a creative process of becoming different or diverging from the abstract standard that defines majority.

Minor literature emerges from this conceptual relationship. For Deleuze and Guattari, creativity in literature extends its authority through a minoritarian mode. Minor literature does not attempt to meet the standard but instead attempts to subvert or revise the standard: ‘minor no longer designates specific literatures but the revolutionary conditions for every literature within the heart of what is called great (or established) literature’ ( Deleuze and Guattari, 1986 , pp. 17–18). In this regard, all great literature is minor literature to the extent that it creates its own standard. The example of Franz Kafka is used to illustrate the point. Kafka was a Czech and a Jew who wrote in German—a language that, although foreign to his being, was also a channel for the creation of identity. For Deleuze and Guattari, Kafka was a great writer because he wrote without a standard view of the interpersonal problems of people. In this way, Kafka’s work does not represent an established identity, but is prefigurative in giving a voice to that which is not given: a ‘people to come’—that is, a people whose identity is a work in progress, in a state of creation and transformation.

In conceptualizing the contours of minor literature, Deleuze and Guattari identify three key characteristics: the deterritorialization of language, the connection of the individual to a political immediacy and the collective assemblage of annunciation. ( Deleuze and Guattari, 1986 , p. 18). Examples from literature will help to unpack these features, and these will be assembled and discussed in Section 4. Before this, a small number of observations should suffice as an introduction to the theme.

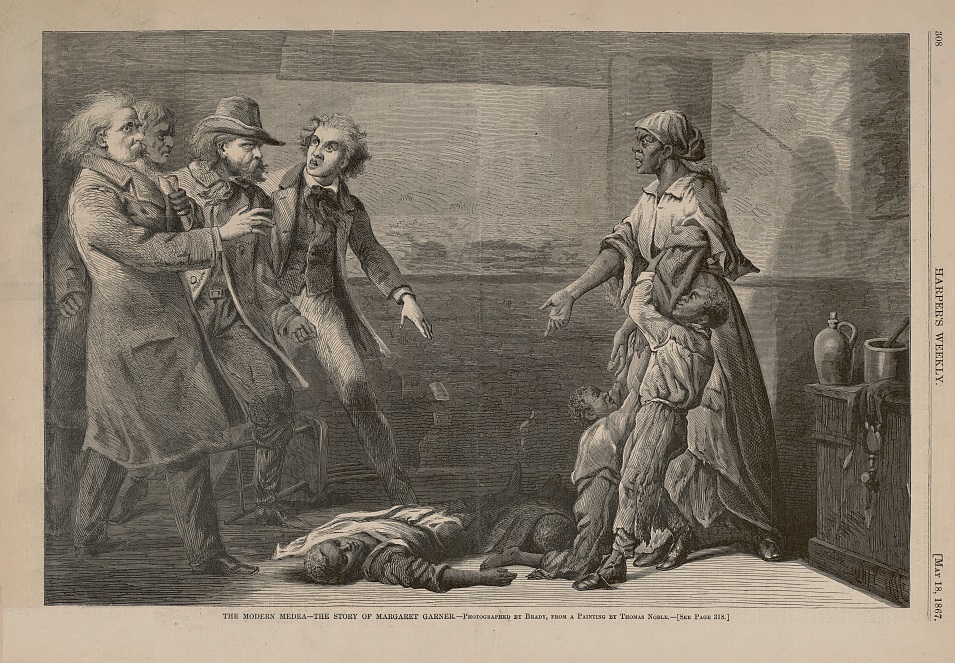

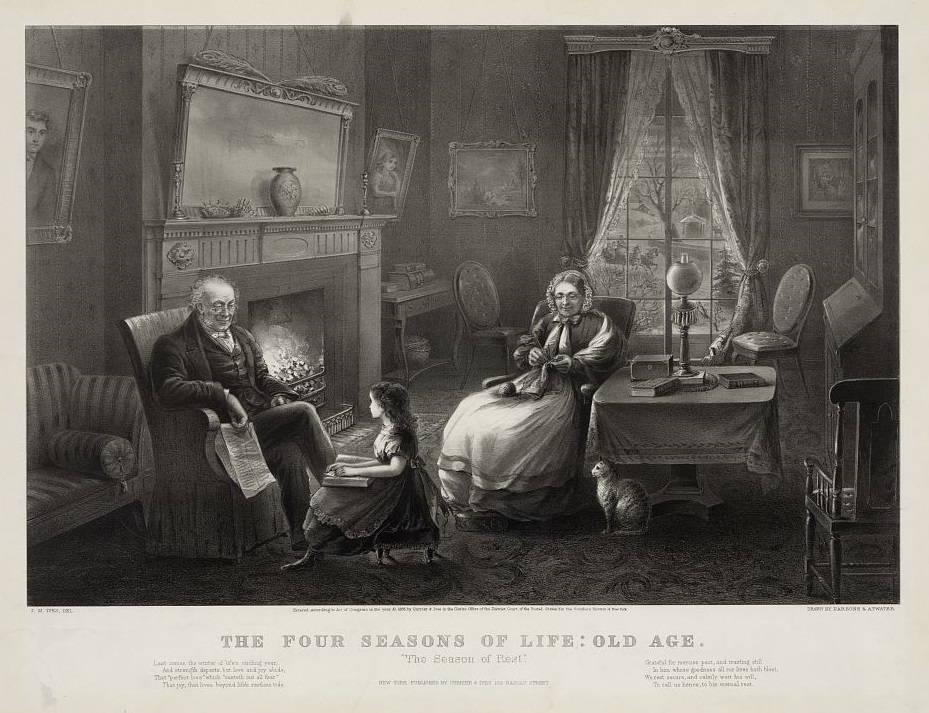

The characteristics of minor literature can be contrasted with those of major literature. A major literature works within a set of literary and discursive standards in order to foreground and narrate the way individual concerns join with other individual concerns within a social environment. These conventions, as much as the social and political setting, remain in the background. The storyline might be anchored in a specific location, but in major literature, this setting serves as the context to explore the subjective experience and relationships developed between the cast of characters we encounter. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin ( 1852 ) will serve as an example of major literature. The novel conforms to its epoch’s conventions of a well-written, structurally sophisticated and emotionally engaging story. The social setting of the novel is mid nineteenth-century Southern USA, defined by the condition of slavery. The novel’s theme is the immorality of slavery, but the narrative structure itself focusses primarily on the relationships between the Shelby family, the St. Clare family, their slaves and their experiences as these relationships change. The novel expresses its anti-slavery narrative through conventional tropes, literary devices and stock characters (cruel slave trader, enlightened slave owner, Uncle Tom, etc.) in a way that appealed to the sensibilities of its predominantly White, Christian readership.

In contrast, minor literature is concerned with the social ‘assemblages’ themselves, which are comprised not merely of characters but also include other equally important entities. Deleuze and Guattari conceptualize this in three ways, particularly with reference to minor literature as a reversal of the conventional interpretation of storytelling. Firstly, this is done by presenting a perspective that is usually invisible or suppressed as the central focus while, at the same time, conventionally dominant codes are handled as though they were alien or unfamiliar. The second way this is achieved is through a reversal of emphasis, specifically in the sense that the cast of characters express social and political forces, and these forces themselves are the subject(s) of the performance. Finally, this is approached by thinking of authorship as the adoption of collective value: the writer does not conform to literary conventions and genres, but instead expresses the collective sentiments of the socio-political reality of the character’s setting.

While these characteristics are almost by definition genre-defying, an example of an approach to literature that combines these features is that of intertextuality. Such writings, irrespective of other qualities they may possess, can be appreciated in enriching, modifying and creating hybrid distortions to the narrative that, in turn, produce that which is not already recognized, suggesting new avenues of becoming and new questions yet to be addressed. In an example to be examined further in the following section, Ishmael Reed’s 1976 novel Flight to Canada illustrates minor literature characteristics, and does so through in a deliberate—and intertextual—contrast with the major literature features of Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin . Flight to Canada examines how American culture narrates the history of the American Civil War. Reed uses real and fictional events from the 1850s and 1860s—including characters appropriated from Stowe’s novel and the corresponding historical figures inspiring them, coupled with the narrator’s world of the 1970s—to satirize this narrative. Conceptualized in this way, it becomes clearer why intertextuality as minor literature plays a potentially important role: such literature is a type of appropriation that resists ethical and aesthetic dominance in order to explore the possibilities of new standards. The following sections will unpack the characteristics of minor literature and exemplify this argument in more detail.

The concept of minor literature is relevant here because of the changing nature of production promotion, exchange and consumption of literature. There is little need to rehearse the argument that social media platforms are changing the way information circulates with implications for the changing nature of the production and consumption of text. The point of most relevance here is that the means and circulation of writing are immense and, by implication, access to culturally specific myths, stories and history, the diversity of styles, approaches to aesthetics and authorship available has expanded. If, in addition, there are a limited number of distinctive plotlines feeding into Western literature (see, for example, Booker, 2004 ), then this diversity is typically channelled through a rather limited set of tropes but one potentially enriched by engaging with non-Western writing or storytelling traditions. Appropriating or adapting a pre-existing location and accompanying set of characters offers different degrees of engagement with the original material and includes a variety of strategies: détournement, fan fiction, honkadori, pastiche, transmedia and type-scene, to name a few. Each is appropriative in taking an existing story or narrative device and using it as the basis of a new story or a continuation or hybridization of the original. Using a strategy of appropriation enables issues to be elaborated and extended because other aspects of the story are already developed or the individuals established. In this way, the voices repeated within intertextual work repeat to transform the work: thus repeating the power of difference, the conditions from which the original work emerged. The work appropriates, but its transformation could equally embody an expropriation, as defined earlier.

As conceptualized this way, the focus of appropriation is to make visible the complex bonds between characters and entities within the story’s social settings that are otherwise overlooked. This is not simply a matter of replacing one voice for another, but of creating a hybrid voice. Such hybrid voices alter the text by eliciting a diversity of styles, pushing back against dominant conventions and questioning the very defining features of literary success. Consequently, this facet of minor literature also implies the emergence of new approaches to literary aesthetics, politics and ethics, as Lev Grossman suggests: ‘[Breaking down walls] used to be the work of the avant garde, but in many ways fanfiction has stepped in to take on that role. If the mainstream has been slow to honor it, well, that’s usually the fate of aesthetic revolutions’ ( Grossman, 2013 : xiii). This does not mean that minor literature can be reduced to features of intertextuality, nor that minor literature is necessarily intertextual. Instead, examining intertextual literature through the lens of minor literature can distinguish acts of appropriation in terms of ethical responsibility, offer opportunities for challenging political dominance and contribute to improved aesthetic transparency by challenging the aesthetic standards that support culturally dominant conventions. Once established, this approach can be applied more specifically to examine other forms of cultural appropriation.

To illustrate this insight a little more, some of the features of appropriation in literature will need to be examined. To provide some exemplification and further insights into the cultural aspects of such appropriation, the notion of intertextuality will be used to illustrate the three key characteristics of minor literature introduced in the previous section.

The first characteristic presented by Deleuze and Guattari describes minor literature as the case in which ‘language is affected with a high coefficient of deterritorialization’ ( Deleuze and Guattari, 1986 , p. 16). Consequently, invisible or otherwise suppressed perspectives become repositioned as the point of emphasis and, as such, are able to challenge dominant codes and conventions, which, as a result, become rendered as foreign or incoherent.

While there is a diversity of motives, styles and modes of expression to be found within intertextual literature, a key theme is that of reversal of foreground/background. Returning to Ishmael Reed’s 1976 novel Flight to Canada will help to illustrate this characteristic, as the flight itself is both literally and figuratively a deterritorialization. In the novel, Reed addresses the way Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin appropriates the narrative framework of Josiah Henson’s autobiography ( Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave ) ( Henson, 1849 ) by reappropriating the story to its rightful owners, the former slaves themselves. Stowe’s novel rescued Henson’s account of his life from obscurity, but at the cost of distortion and sensationalism serving the codes, conventions and expectations of a predominantly White readership, as expressed through the lens of its White characters. Reed’s corrective is a counter-distortion of history by telling Henson’s story from the slave’s perspective but using deliberate anachronism and combining real and fictitious events in ways that reverse expectations and use literature itself for the purpose of liberation. In the novel, the lives of powerful and notable historical individuals (Lincoln, Jefferson Davis, Stowe, for example) are fictionalized, being presented as stereotypical figures, incoherent drunks and trite dupes for the reader’s ridicule, while the characters representing Henson, the slaves and slave descendants he encountered in his life are given depth and insightfulness, particularly in voicing their reflections on the historical conditions for emancipation.

In reflecting on a very different approach to reappropriation, Françoise Lionnet’s view that Francophone women novelists of colour offer insights into ‘border zones’ of culture provides another example of this first characteristic ( Lionnet, 1992 ). Examples of the deterritorialization of language are demonstrated by Lionnet’s observation that at the periphery of cultural discourses is a heteroglossia, a hybrid language that is a site of creative resistance to dominant conceptual paradigms. The creative literary practices that are employed by writers of African heritage occupying these border zones reveal, for Lionnet, processes of adaptation, appropriation and contestation, which shape identity in colonial and postcolonial contexts. The established conventions of storytelling found in the literature of the colonial power are invoked by postcolonial border-zone writings, often for the purpose of being subverted, in particular: ‘to delegitimate the cultural hegemony of “French” culture over “Francophone” realities’ ( Lionnet, 1992 , p. 116).

The second characteristic identified by Deleuze and Guattari is that minor literature emphasizes social and political forces rather than focussing primarily on individual concerns joined with other individual concerns charted through a series of personal experiences, as is the case with major literature. Instead, Deleuze and Guattari make the following observation concerning this second characteristic: ‘its cramped spaces forces each individual intrigue to connect immediately to politics. The individual concern thus becomes all the more necessary, indispensable, magnified because a whole other story is vibrating within it’ ( Deleuze and Guattari, 1986 , p. 17).

Jean Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) offers a useful illustration of such political immediacy. In the novel Rhys interweaves feminist and postcolonial argument within an intertextual plot derived from, and intertwined with, Charlotte Brontë’s novel Jane Eyre (1874). Rhys’ novel tells the story of Bertha Mason (under her real name Antoinette Cosway) from the character’s point of view. The story begins with an account of her childhood in Jamaica and recounts her honeymoon and unhappy marriage to Edward Rochester. The story charts her emigration to England and ultimately her confinement to ‘the attic’ of Thornfield Hall. The main character is, in many ways, the mirror of Jane Eyre but, as a Creole woman having lost her wealth and position in society and in a fragile state of mental health, is one that can be seen as having developed through an explicit engagement with the (political) forces of patriarchy, colonialism, racism, displacement, assimilation and slavery. It is within the cramped space shaped by these political forces that the madness of Bertha can be recognized and explained, and which confine her as much as her husband’s servants tasked with keeping her prisoner at Thornfield Hall. In a similar way, Hanan al-Shaykh’s One Thousand and One Nights: A Retelling ( 2011 ) and David Henry Hwang’s play M. Butterfly ( 1993 ) develop intertextual strategies to (re)appropriate stories and characters that have been refracted through orientalist retelling. Through the use of hybrid postcolonial cultural principles, each author shapes intertextual narratives with which to explore and oppose the social and political forces of dominance associated with cultural imperialism. Both al-Shaykh and Hwang, like Rhys, also used their texts to reappropriate from their source literature a series of mythologies with which to undermine the conservative values still present in ‘decolonized’ cultures. These myths become political forces to challenge discrimination and the exclusion of disadvantaged groups, such as women and LGBT communities, in their respective cultures.

The third defining characteristic of minor literature is that it affords the taking on of collective value. It is worth quoting at length from Deleuze and Guattari to clarify what this implies:

Indeed, precisely because talent isn’t abundant in a minor literature, there are no possibilities for an individuated enunciation that would belong to this or that ‘master’ and that could be separated from a collective enunciation. Indeed scarcity of talent is in fact beneficial and allows the concept of something other than a literature of masters; what each author says individually already constitutes a common action, and what he or she says or does is necessarily political, even if others are not in agreement. ( Deleuze and Guattari, 1986 , p. 17)

Intertextual literature is a type of writing for which the notion of talent varies according to the themes, styles and objectives that characterize the relationship between the new work and the canonical work. As derivative works, there are already the conditions for a collective enunciation, albeit perhaps a sense that is marginal, but it is equally a condition of great literature in forging ‘the means for another consciousness and another sensibility’ ( Deleuze and Guattari, 1986 , p. 17). In examining the conditions for great literature, Claire Colebrook, in her introduction to Deleuze and Guattari, uses James Joyce’s Dublin to illustrate this third aspect of minor literature, a Dublin Joyce portrays (in both Dubliners and Ulysses ; 2000a , 2000b ) through themes, techniques and characters appropriated from Homer’s Odyssey :

Joyce’s Dubliners repeats the voices of Dublin, not in order to stress their timelessness, but to disclose their fractured or machine-like quality – the way in which words and phrases become meaningless, dislocated and mutated through absolute deterritorialisation. What Joyce repeats is the power of difference. ( Colebrook, 2002 , p. 119)

Colebrook explains that Joyce’s Dublin is a (colonially appropriated) territory formed from the language of religious moralism and a bourgeois commercialism such that when ‘free-indirect style frees language from its ownership by any subject of enunciation, we can see the flow of language itself, its production of sense and nonsense, its virtual and creative power’ ( Colebrook, 2002 , p. 114). Colebrook’s observation is a useful illustration of this third characteristic of minor literature because, in avoiding any conformity to existing genres and their techniques and traditions, and instead expressing collective sentiments of a relocated territory, Joyce is able to recount and provide navigation points to track the social assemblages that the characters shape from an otherwise ordinary day in Dublin in 1904. The collective value embodied within the territory is thus further reinforced through parallels and echoes with the ten-year odyssey of Odysseus in his world.

Joyce appropriates, but not to repeat Hellenic cultural values. Instead, he repeats—renews—the power of difference from which Homer’s original story was created. It is also no coincidence that Homer, in providing the first written versions of sophisticated storytelling of its type, also provides scope for the first sophisticated intertextual literature, each disclosing the power of Homer’s epic to transform. These include Virgil’s Aeneid , which presents a narrative of the Trojan War and its consequences from the point of view of the vanquished (and their place in Rome’s founding myth) and Euripides’ play Trojan Women , an account of the events of the Trojan War from the point of view of female characters. Homer’s text continues to afford the repetition of difference, from Derek Walcott’s Omeros ( 1990 ), a postcolonial reworking of Homer relocated to the Caribbean, to Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls ( 2018 ) and Madeline Miller’s Circe , ( 2018 ), which like Euripides’ before them, portray the Trojan War from the perspective and experience of Homer’s (minor) female characters.

Taken collectively, these characteristics illustrate the potential for appropriative strategies to be implemented in the service of emancipatory storytelling, in particular by repurposing other cultural values. In this way—and unlike major literature, which remains attached to the service of power—storytelling as minor literature gives a voice, a collective value, and it recognizes the political and social conditions shaping its characters that, in turn, serves to rouse its readers. This observation that appropriation from other cultures can be liberating for marginal voices complicates many lines of critique used to denounce cultural appropriation as a unified practice. It is, however, also a powerful strategy, particularly in repurposing and disarming the language and values used to marginalize and exclude other cultural perspectives, as will be presented in the following sections. Examining the ethical and aesthetic consequences implied by the rethinking of literary works through the minor literature lens will therefore provide insight into distinguishing between cultural appropriation and cultural expropriation. This distinction is of particular relevance for examining creativity emerging from multiple cultural influences and in the broader debates concerning cultural exchange within the arts. It is to this theme that the article will now turn.

Creativity within the arts often involves engaging with an aesthetic cosmopolitan appreciation of culture, often in a way that perceives itself to be ‘morally responsible and aesthetically discerning’ ( Rings, 2019 , p. 161). Within this context, the use of appropriative strategies to further artistic creativity can be analyzed in many ways, but the lens of minor literature helps in focussing on clarifying different ethical and aesthetic implications related to the different approaches that define the cultural encounter.

Using this lens enables a distinction to be applied to strategies of intercultural engagement based on the implications of exchange: appropriation (or misappropriation) includes instances in which characteristic narratives, techniques, symbols and artefacts are taken or imitated in a way that diminishes the original sources. In contrast, expropriation includes the act of repurposing narratives, techniques, symbols and artefacts in ways designed to enhance the original or provide benefits for the common good. While these features are only part of the defining characteristics of these concepts, when prefixed with the word ‘cultural’, the difference is as contrasting as it is useful. Thus, cultural appropriation represents an unauthorized use or imitation of characteristics, techniques, and so on, from their cultural setting in a way that risks diminishing their cultural source and compromising their purpose. Cultural expropriation, in contrast, is an attempt to provide a broader access to cultural resources and spaces that have provided value for privileged beneficiaries so that others may experience these benefits in a way that has the potential to be mutually enhancing. As a pursuit of majoritarian interest, cultural appropriation preserves existing aesthetic standards, which benefit vested interests. Cultural expropriation, as exemplified by practices of minor literature, helps to question these standards, drawing attention to, or indeed challenging, the conditions that maintain vested interests and provide more opportunities for aesthetic pluralism, ultimately opening up the possibility of new standards of literature.

The minor literature paradigm also emphasizes that the ethical and aesthetic implications of cultural appropriation are interdependent, as are the implications of cultural expropriation. Appropriation and expropriation are not neutral processes; exchange is always dependent on factors beyond the immediate goals of the transaction or encounter. Instances of appropriation predominantly serving majoritarian interests are thus both ethically and aesthetically implicated. This is because exploiting cultural products developed by marginalized groups to serve the interests of dominant social groups reshapes them according to the logic of the commodity form (see Kulchyski, 1997 , p. 617). In this form, ownership is stripped from those with fewest resources, value is extracted and, rather than recognition and reconciliation, coercion is used to define (and impose) ethical and aesthetic standards. These standards might welcome or appreciate otherwise excluded female or minority ethnic artists and writers, but they do so, perhaps for tokenistic reasons, in the interest of the values determined by the dominant culture. In conforming to this logic, minority cultures can be mined or harvested in ways that support the interest of established power relations because the work of art derives its value not from its role as a cultural intermediary or its mode of communication, or in cultivating cultural appreciation, but as a circulating commodity.

In contrast, instances of expropriation occur when creativity associated with marginal cultures or dominated social groups is produced in accordance with cultural resources developed by dominant social groups in order to challenge the standards that maintain and legitimize such cultural dominance. The ethical and aesthetic implications are interdependent because, by addressing exclusion and inequality, this form of engagement provides opportunities for re-examining existing aesthetic standards, as exemplified by recent attempts to ‘decolonize’ the arts curriculum (see, for example, Prinsloo, 2016 ).

Additionally, the cultural appropriation/expropriation division is an important distinction that helps to position different aspects of cultural exchange. A majoritarian usage involves taking ownership of cultural phenomena without questioning the image or essence of its own sense of cultural identity. It expresses extensive multiplicity in that adding more instances does not change the nature of its identity. For example, European and American art of the past century owes a debt to non-Western cultural sources; however, the resulting Western art, as artistic creation, derives its value in being captured and filtered by ‘gate keepers’ and ‘arbiters of taste’ serving European and American cultural measures, namely the aesthetic frameworks and foundations that match/reduce the art work to established criteria, determining which artefacts are to be accepted as ‘fitting’ works of art and through which markets they are to be consumed. As Baudrillard observes:

Modern art wishes to be negative, critical, innovative and a perpetual surpassing, as well as immediately (or almost) assimilated, accepted, integrated, consumed. One must surrender to the evidence: art no longer contests anything, if it ever did … it never disturbs the order, which is also its own. ( Baudrillard, 2019 , p. 103)

In contrast, a minoritarian usage expresses intensive multiplicity—that is, it does not just match features already established, but each additional example alters the composition of the group. In this way, minoritarian practices will take cultural artefacts, practices, content or styles and use them in ways that help to shape the possibilities of their identity and make connections, which in turn shape other identities. For example, intertextual writing, such as Reed’s Flight to Canada discussed earlier or indeed fan fiction, expropriate the characters of a canonical work and insert them into novel relationships so that new aspects of identity or its setting can be elaborated and extended beyond its established world. In this way, the voices repeated within the intertextual work are not those of the author of the original or the derivative work, but are intermediaries, (re)writing the literary event that opens up new possibilities for the reader (see Attridge, 2004 , 2010 ). The voices of intertextual works repeat much that is ‘canon’ in order to transform it: repeating the power of difference by repeating the conditions from which the original work emerged, as the Joyce/Homer example demonstrates.

Such writing also subverts the logic of established ethical and aesthetic standards, undermining both the logic of the commodity and the conventions of categorizing talent. It does so by blurring market boundaries and disrupting market forces: much of this writing, as exemplified by fan fiction, is exchanged free of charge and often circulates in draft form or otherwise incomplete and frequently disseminated anonymously (or pseudonymously). In appropriating from established literature, such work often defies copyright and asserts its existence not by appealing to criteria established by literary criticism but by justifying its relevance in customizing and ‘supplementing’ established works. Indeed, it often defines itself in terms of its opposition to the values or implicit assumptions insinuated or implied within the original work. It is in this regards a ‘dangerous supplement’—‘It adds only to replace. It intervenes or insinuates itself in-the-place-of; if it fills, it is as if one fills a void’ ( Derrida, 1976 , p. 145) but as writer Joss Whedon observes: ‘Art isn’t your pet—it’s your kid. It grows up and talks back to you’ ( Whedon, 2012 ).

Focussing on the beneficiaries of appropriative practices is a useful device in ensuring that standards, both ethical and aesthetic, are reviewed so that intercultural engagement becomes an opportunity to enhance appreciation of perspectives derived from a variety of cultures and to enrich artistic creation. The negative issues identified with cultural appropriation cannot be addressed by majoritarian strategies such as tokenism, patronizing encouragement or quotas to refresh an otherwise pre-established artistic canon. Minoritarian approaches, such as expropriation or cultural/artistic transculturation are required to reflect an appropriate measure of responsibility and cultural awareness in defining an inclusive, meritocratic, creative, engaging and critical approach to artistic creation—namely a conception of the arts that contests and disturbs the order, reclaiming this role for the avant garde once more.

al-Shaykh , H . ( 2011 ). One thousand and one nights: A retelling . London : Bloomsbury .

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Attridge , D . ( 2004 ). The singularity of literature . London : Routledge .

Attridge , D . ( 2010 ). ‘The singular events of literature’ . British Journal of Aesthetics , 50 , pp. 81 – 84 .

Baldwin , J. , Faulkner , S. and Hecht , M . ( 2008 ). ‘A moving target: The illusive definition of culture’, in Baldwin , J. R. , Faulkner , S. , Hecht , M. L. and Lindsley , S. L. (eds), Redefining culture: Perspective across the disciplines . Mahwah : Lawrence Erlbaum Associates , pp. 3 – 26 .

Barker , P . ( 2018 ). The silence of the girls . London : Hamilton .

Baudrillard , J . ( 2019 ). For a critique of the political economy of the sign . London : Verso Books .

Booker , C . ( 2004 ). The seven basic plots: Why we tell stories . London : A&C Black .

Carriger , M. L . ( 2018 ). ‘No “thing to wear”: A brief history of kimono and inappropriation from Japonisme to kimono protests’ . Theatre Research International , 43 , pp. 165 – 184 .

Colebrook , C . ( 2002 ). Gilles Deleuze . London : Routledge .

Cuthbert , D . ( 1998 ). ‘Beg, borrow or steal: The politics of cultural appropriation’ . Postcolonial Studies: Culture, Politics, Economy , 1 , pp. 257 – 262 .

Deleuze , G. and Guattari , F . ( 1986 ). Kafka: Towards a minor literature . Minneapolis, MN : University of Minnesota Press .

Deleuze , G. and Guattari , F . ( 1988 ). A thousand plateaus . London : Athlone .

Derrida , J . ( 1976 ). Of grammatology . Baltimore, MD : Johns Hopkins Press .

Dong-Hoo , L . ( 2006 ). ‘Transnational media consumption and cultural identity’ . Asian Journal of Women’s Studies , 12 , pp. 64 – 87 .

Galindo , R. and Medina , C . ( 2009 ). ‘Cultural appropriation, performance, and agency in Mexicana parent involvement’ . Journal of Latinos and Education , 8 , pp. 312 – 331 .

Goldstein-Gidoni , O . ( 2003 ). ‘Producers of “Japan” in Israel: Cultural appropriation in a non-colonial context’ . Journal of Anthropology Museum of Ethnography , 68 , pp. 365 – 390 .

Grossman , L . ( 2013 ). ‘Foreward’, in Jamison , A. (ed), Why fanfiction is taking over the world . Dallas, TX : Smart Pop , pp. xi – xiv .

Heyd , T . ( 2003 ). ‘Rock art aesthetics and cultural appropriation’ . The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism , 61 , pp. 37 – 46 .

Henson , J. ( 1849 ). The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave . Boston : Phelps .

Homer ( 2003 ). The Odyssey . London : Penguin Classics .

Hoyes , C . ( 2004 ). ‘Here Comes the Brides’ March: Cultural appropriation and Latina activism’ . Columbia Journal of Gender and Law , 13 , pp. 328 – 353 .

Hwang , D. H . ( 1993 ). M. Butterfly. New York : Penguin .

Jackson , L. M . ( 2019 ). White negroes: When cornrows were in vogue and other thoughts on cultural appropriation. Boston : Beacon Press .

Joyce , J. ( 2000a ). Dubliners . London : Penguin Classics .

Joyce , J. ( 2000b ). Ulysses . London : Penguin Classics .

Kramvig , B. and Flemmen , A. B . ( 2019 ). ‘Turbulent indigenous objects: Controversies around cultural appropriation and recognition of difference’ . Journal of Material Culture , 24 , pp. 64 – 82 .

Kulchyski , P . ( 1997 ). ‘From appropriation to subversion: Aboriginal cultural production in the age of postmodernism’ . American Indian Quarterly , 21 , pp. 605 – 620 .

Lionnet , F . ( 1992 ). ‘“Logiques métisses”: Cultural appropriation and postcolonial representations’ . College Literature , 19 , pp. 100 – 120 .

Matthes , E. H . ( 2016 ). ‘Cultural appropriation without cultural essentialism?’ . Social Theory and Practice , 42 , pp. 343 – 366 .

Miller , M . ( 2018 ). Circe . London : Bloomsbury .

Moore , A . ( 2017 ). Stewart Lee in conversation with Alan Moore #contentprovider. [video] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iytGHs4Nga0 [ Accessed: 1 December 2019 ].

Moraru , C . ( 2000 ). ‘“Dancing to the typewriter”: Rewriting and cultural appropriation in flight to Canada’ . Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction , 41 , pp. 99 – 113 .

Prinsloo , E. H . ( 2016 ). ‘The role of the humanities in decolonising the academy’ . Arts and Humanities in Higher Education , 15 , pp. 164 – 168 .

Reed , I . ( 1976 ). Flight to Canada . New York : Random House .

Rings , M . ( 2019 ). ‘Aesthetic cosmopolitanism and the challenge of the exotic’ . British Journal of Aesthetics , 59 , pp. 161 – 178 .

Rogers , R. A . ( 2006 ). ‘From cultural exchange to transculturation: A review and reconceptualization of cultural appropriation’ . Communication Theory, 16 , pp. 474 – 503 .

Shugart , H. A . ( 1997 ). ‘Counterhegemonic acts: Appropriation as a feminist rhetorical strategy’ . Quarterly Journal of Speech , 83 , pp. 210 – 229 .

Sinkoff , N . ( 2000 ). ‘Benjamin Franklin in Jewish Eastern Europe: Cultural appropriation in the age of the enlightenment’ . Journal of the History of Ideas , 61 , pp. 133 – 152 .

Stowe , H. B. ( 1852 ). Uncle Tom's Cabin . London : Cassell .

Walcott , D . ( 1990 ) Omeros . Glasgow : Harper Collins .

Wetmore , K. J . ( 2000 ). ‘The tao of Star Wars, or, cultural appropriation in a galaxy far, far away’ . Studies in Popular Culture , 23 , pp. 91 – 106 .

Whedon , J . ( 2012 ). I am Joss Whedon: Ask me anything ’. Reddit . Available at: https://www.reddit.com/r/IAmA/comments/s2uh1/i_am_joss_whedon_ama/c4ao0m1/ ( Accessed: 20 December 2019 ).

Whitten , S . ( 2019 ). ‘ Nigeria’s ‘Lionheart’ disqualified for international film Oscar over predominantly English dialogue - but Nigeria’s official language is English’ . CNBC . Available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2019/11/05/nigerias-lionheart-disqualified-for-international-feature-oscar.html?&qsearchterm=lionheart ( Accessed: 4 September 2020 ).

Young , J. O . ( 2000 ). ‘The ethics of cultural appropriation’ . The Dalhousie Review , 80 , pp. 301 – 316 .

Young , J. O . ( 2005 ). ‘Profound offence and cultural appropriation’ . The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism , 63 , pp. 135 – 146 .

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-2842

- Print ISSN 0007-0904

- Copyright © 2024 British Society of Aesthetics

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Understanding adaptation and appropriation in art and literature

Please log in to save materials. Log in

- EPUB 3 Student View

- PDF Student View

- Thin Common Cartridge

- Thin Common Cartridge Student View

- SCORM Package

- SCORM Package Student View

- 1 - Terms and objectives

- 2 - It's a reading rainbow

- 3 - King Kong and the mysteries of Pittsburgh

- 4 - Declaration and adaptation: At play in democracy

- 5 - Gangster films

- 6 - Independent practice

- View all as one page

Terms and objectives

If the goal is to teach students to read and write like writers, then they need to read and write like writers, which means they have to be constantly taking texts apart and examining them and then rearranging and reinventing them in new ways. They kind of do this when they interact online with social media. Memes and Gifs do this, but often time, the humor is not explained--the sign is not taken apart and distilled.

The lessons and activities included here revolve around the following terms. Other terms might also be necessary for students to learn the language of analyzing adaptations and appropriations. The skills here are useful in AP and general education classes, as well as in language art electives such as Creative Writing and Film Studies.

The cited terms are from Julie Sanders' book Adaptation and Appropriation . Her book is about 160 pages long. I encountered it in graduate school, and it is definitely worth a gander. (All apologies: the word gander is pedantic, as is the word pedantic.)

Objective

Students will be able to discuss and analyze how literature and art often borrow, adapt, and appropriate the ideas, forms, and styles of earliear artists, genres, and movements. Such skills are important for not only helping students appreciate writing as art but in helping them find pathways toward their own creative output. These are the ideas and skills that help writers become apprentices.

Genre: a category of artistic composition, as in music or literarture, characterized by similarities in form, style, or subject matter. Genre theory is a structuralist approach ot interpreting literature that treats each genre as a mechanized system in need of particular parts (tropes and conventions)

Convention(s): The rules of a particular genre. These rules act as indicators or signs that a piece of a literature belongs to a particular genre. Indicators include but are not limited to: phrases, themes, quotations, explanations, archetypes, stereotypes, and situations that serve similar functions within a genre. When particular indicators defy convention, the result is often ironic.

Homage: Similar to parody, but the intention is to honor more so than to mock. It's a tip of the cap to those whose art was influential to the art being created (or invented) in the present moment.

Pastiche: A work of art that is an imitation in style and structure of other art. Think of it as a collage.

Appropriation: Appropriation occurs when art essentially lifts a stylistic component or convention from a particular genre or work but "affects a more decisive journey away from the informing source into a wholly new cultural product and domain" (Sanders 26).

Adaptation: Adaptation occurs when a text "signals a relationship with an informing sourcetext or original" (26). Methods of adaptation include: transposition, commentary, analogue.

It's a reading rainbow

In his book Mythologies, Roland Barthes writes:

The reduction of reading to consumption is obviously responsible for the 'boredom' that many people feel when confronting the modern ('unreadable') text, or the avant- garde movie or painting: to suffer from boredom. means that one cannot produce the text, play it, open it out, make it go.

I don't understand everything Barthes says, but I do latch onto the word "play" here and the idea that a text has something to " make it go." This activity, hopefully, invites students to start doing so (although I've found that to keep them doing this requires constant creative work on behalf of the teacher throughout the year).

Opening questions

-What is a door?

-What is a reading rainbow?

(Keep in mind here the answers don't really matter as long as students try, and a teacher can tell a lot about a student who is or isn't willing to entertain the small, simple questions.)

Adaptation versus appropriation

Provide students with Julie Sanders' definitions for the two terms.

Have students watch the 1967 performance by The Doors on The Ed Sullivan Show . Hopefully, the experience is weird for them. The Doors were anachronistic and weird then, and they're even more so today. After watching the performance, have students discuss their reactions, ask questions, etc., but keep in mind the goal is not to have them really understand or appreciate The Doors. The goal is for the performance to be in their memory banks, to be part of a reservoir of random pop culture moments.

Have students watch the opening credits fo the PBS show Reading Rainbow. Go with the original version . Have students discuss and react just as you did with the performance by The Doors.

Finally, have students watch Jimmy Fallon singing the theme song from Reading Rainbow while impersonating Jim Morrison from The Doors. Here is where the work begins because what Fallon does here is take the supposed innocence and morality of children's literature and subverted it with the presence of a Jim Morrison caricature and all that The Doors and the 1960s counterculture represented or embodied. Is this performance an act of appropriation or adaptation? Have students support their answers with Julie Sanders' definitions. Have them consider qualifying their position.

Obviously, the source materials here are dated, and as the Fallon text slips more and more into the past, other examples may have to be gleaned from the cultural zeitgeist. Thank goodness we have the internet!

King Kong and the mysteries of Pittsburgh

Have students watch scenes from the 1933 version of King Kong, specifically the scene where Kong climbs the Empire State Building. Have students brainstorm subjects, topics, and themes this scene (or any other scenes) communicate to modern audiences. Does the film communicate the same concerns and fears and ideas to contemporary audience members as it did to audiences in the 1930s? This could be done as an informal discussion or as a journal entry.

Have students read the climactic chase scene from Michael Chabon's 1988 debut novel The Mysteries of Pittsburgh. (I believe the scene in question can be found in the book's twenty-second chapter: "The Beast That Ate Cleveland.") Have students discuss (or have them provide written answers) where they assess whether the chapter is an homage to or a parody of King Kong. Is it an adaptation or an appropriation? What's the purpose? What are the significances? How can the relationship between the two texts be interpreted? Is the connection between the chapter and the movie simply interesting or is it vital for understanding the text?

Other Chabon texts to consider

- The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay (2000) shares some amazing relationships with comic books and Orson Welles' Citizen Kane. The book is probably too long and dense for most high schoolers to deal with in a calendar school year, but it can be excerpted.

- The Yiddish Policemen's Union (2007) begins by announcing itself as belonging to a particular genre. How does it do this?

- The essays in Chabon's Maps and Legends: Reading and Writing Along the Borderlands are especially useful to these kinds of discussions.

Declaration and adaptation: At play in democracy

The following sources could be used to demonstrate a more serious side to Barthes' idea of how texts "play." Past documents inform present documents. Values and laws from one time period shape and interact with values and laws from another time period. Tracing the concepts (and quite literally the terminology) of 'happiness,' 'property,' 'freedom,' 'liberty,' and 'independence' in the following documents can be tedious work that pay dividends by the end of the year in terms of how students can start to perceive the long arc of an idea.

Excerpt Plato's "The Allegory of the Cave" from The Republic. Have students annotate the text or complete dialectical journals. Have students draw or construct models of the text. Discuss the differences between the text's purpose and its significances. Guide students through a close reading of the text's transition from allegory to politics. Guide students through a close reading of passage's conclusion. These are all options.

Locate a brief text where John Locke discusses the individual's relationship with 'property.' I have often used passages from John Dunn's Locke: A Very Short Introduction for doing so. Have students discuss his possible meanings and its consequences. Have students place Locke's ideas in relation to Plato's, specifically Plato's admonishment of concrete, physical wealth.