Dementia Case Study Essay – 3500 words

HEALTH ISSUES FOR OLDER ADULTS.

The Case Study

Previous History: Social

The case study chosen is that of a 74 year old male patient with a history of challenging health issues. John (an assumed name in order to protect the patients identity in accordance with the Code of Professional Conduct as per the Nursing & Midwifery Council, 2006) has been happily married for 54 years and does not have any children. He does belong to a large extended family – he has twelve siblings. He has spent his working life as a plumber. He has been a sociable person enjoying the company of friends and family. Before admission to the Dementia ward he was living with his wife in their family home. His wife is finding it increasingly difficult to deal with John’s behaviour and condition as recently he has become significantly cognitively impaired. On admission, John was clean and tidy and it was obvious that his wife takes very good care of him despite the considerable effort that is required by her. During his stay on the ward John did receive regular visitors and his family and friends showed a great deal of affection for him.

Previous History: Medical

On admission it was noted that John has a long history of ill health.

His main conditions are:

Multi-Infarct Dementia: “MID is a common cause of memory loss in the elderly. MID is caused by multiple strokes (disruption of blood flow to the brain). Disruption of blood flow leads to damaged brain tissue.” (NINDS). This was diagnosed three months ago after John exhibited trademark symptoms such as short term memory loss, confusion, shuffling feet. He also started losing bladder and bowel control. MID is usually found within the 60 – 74 year age group, more often in men than women. A MRI scan showed up this condition.

Cardiac Diverticulitis: a rare congenital heart malformation

Aortic Aneurysm

Hypertension

These conditions cause John great pain and distress. He is currently being administered several pain relieving medications – Morphine, Sevradol, Diclofenic and paracetamol. He also received medication for the hypertension.

John was told 15 months ago that the prognosis for the treatment of his Aortic Aneurysm was not good and it was anticipated that his life expectancy was six months.

The severity of the pain experienced by John results in very aggressive physical and verbal behaviour. This aggression is very difficult for his loved ones to deal with.

He was admitted to the dementia ward for a six week assessment with a view to providing suitable pain relief which could then lessen his challenging behaviour to an extent.

Care assessment

On admission to the ward, John was attended by psychiatric staff who carried out an evaluation on John’s memory. This is known as a Mini Mental State Examination. The MMSE indicates the importance of cognitive stimulation therapy that can be consistently offered to the patient. (Weavers (2007, p.1) (see Appendix 1). The MMSE is a series of questions and tests designed to establish whether a drug treatment would be appropriate. NHS guidelines state that the patient should score 12 points or more out of a maximum of 30 points to be considered for medication. The tests cover orientation to time, registration, naming and reading skills. (Alzheimer’s Society information sheet 436).

John was also assessed in terms of diet and sleep.

The Discomfort Scale-Dementia of the Alzheimers’s Type (DS-DAT) was carried out with John. DS-DAT measures discomfort in elderly patients with dementia who are losing cognitive capacity and communication skills and are increasingly reliant on nursing staff. It was originally conceived to measure discomfort but it can be used to assess pain.

Assessment on John revealed that when he is in pain he is prone to be more aggressive. Staff worked with him to find strategies he could use to alleviate the pain. He received psychological assistance from the Pain Management Specialists. According to research on care of the elderly pain assessment is always an important aspect of what is done to take care of patients with dementia. The pain manifestation in John’s case has been a concern for everyone involved in his care. This is supported by Smith (2005) who says that it is important for healthcare providers to make correct assessment in the treatment of elderly people. There are many deterrents to making correct assessment. The fact that our culture looks at dementia as a disease that is only in the mind and that people with dementia do not experience pain can create a problem because often doctors may not see symptoms as belonging to dementia. Also, as patients begin to lose the ability to understand their internal states, they cannot identify easily “sensations, feelings and experiences” (Smith 2005 p.2). This will also lead to a time when they may not be able to verbalise what they are feeling. When the condition gets to this stage it is important to take care of the comfort needs of the individual. Many healthcare providers assess this by means of a Comfort Checklist. Smith (2005) was able to show professionals that there are several assessment tools that can be used to assess pain levels in patients with dementia.

Kaasalainen (2007) presents another idea of how to assess the pain of patients with dementia by using behaviour observation methods. This literature supports that pain is “underestimated and undertreated” in the older population. Assessment then becomes even more important.

Early pain assessment is important because the patient may start to lose the cognitive ability to let their discomforts be known. A system of behavioural observation would be useful. In order for this to be accurate a system of criteria for behaviour indicators can be set. Some indicators include “rapid blinking and other facial expressions, agitation or aggression, crying or moaning, becoming withdrawn and guarding the body part “

(Kaasalainen, 2007 p.7).

When John starts getting aggressive it can be an indication that he is in pain. “ It is important to find out how patients with dementia communicate about their pain and to determine relevant background information about their pain needs.” McClean (2000) cited in Cunningham (2006) p.5. In order that a full assessment could be made of John and his pain communication and management, he was allocated a nurse to be with him all of the time to achieve an accurate record.

The Discomfort Scale for Patients with Dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type (DS-DAT) previously referred to has been challenged by Kaasalainen (2007). Some of the challenges she stated include:

“ * some of the items measured may be due to other situations and not only dementia.

· the way the tools are scored can be difficult and therefore not easy to use in the clinical setting

· most of the new tools (and other DS-DAT) are in preliminary stages and need more testing

· there is lack of consensus on how pain should be assessed with older adults so verbal reports continue to be used in most situations.

· The concept of discomfort may be due to other facts like infection, hunger, depression or anxiety which means that behavioural observations cannot be the sole basis for giving medication.” (Kaasalainen, 2007 p.8)

Gloth (2001) presented information about pain management in older adults. He stated that it is difficult to make sure that older patients are getting enough medication to manage their pain adequately. Most older patients have at least one chronic condition and take multiple medications which make it harder to tell what they require. For some healthcare providers it becomes more frustrating to make sure the pain is managed properly. Gloth (2001 p.188).

It is important to understand when giving medication that drugs have a different reaction in older adults that they have in younger patients. This must be taken into account when prescribing. When pain is managed well an individual will have ‘secondary gain’ whereby he will feel better and it will help family members stay and visit longer. All of this will help the patient manage his pain. (Gloth 2001 p.189). Gloth (2001) also suggests that clinicians use a variety of methods for pain management including no interventions and alternative therapies where possible.

In the ward the environment is kept as quiet as possible as it is policy not to administer neuroleptic drugs unless really necessary. Pharmacological treatment options are recommended only if behaviour poses an immediate risk to the individual or to others Weaver (2007), McShane et al (1997) cited in Narzarko (2007 p.118) states that researchers have found that people with dementia who are treated with neuroleptic drugs deteriorate more quickly than those who are not treated with such drugs.

Besides having his own individual nursing care, John is offered activities to help him stay as active as possible. It was reported in Jacques et al (2000 p.366) “offering patients the appropriate activity, i.e. Games, exercise, sitting and chatting can reduce boredom and agitation. John responds well to this individual attention and it does have a settling effect. During his working life, John was always working with his hands so he is keen to participate in games and exercise. He does try to engage in social contact with other patients but unfortunately this interaction has not been reciprocated so it has caused him upset and frustration and after a few attempts he now only talks with the nurse caring for him. His physical activity is also hindered by his pain.

John has lost a lot of weight recently so he has been seen regularly by the dietitian who is ensuring that he is eating a healthy nutritional diet. He does have a good appetite.

John’s sleep pattern has been erratic the last several months. “Many people with dementia are restless at night and find it difficult to sleep. Dementia can affect people’s body clocks so that they might get up during the night, get dressed or even go outside. Ensure that the person has enough exercise during the day and that they use the toilet before bed.(Alzheimer’s information sheet 525). John was gently reminded that it was night-time and that he should go back to sleep. A sleep diary was also kept to record the level of restlessness.

There are two types of carers involved in looking after John – those who work within the clinical setting and those family members who must care for a chronically ill family member. The family member is predominately John’s wife.

Rasin and Kautz (2007) carried out a study that focused on caregivers in assisted living facilities. The National Centre for Assisted Living (NCAL) estimates that “42% to 50% of residents in assisted living facilities have dementia and 34% of them exhibit behavioural symptoms of dementia at least once a week.” NCAL (2006) cited in Rasin and Kautz (2007 p.2). They found that caregiver training was different depending on the state in which the individual lived and many were not formally trained to work with dementia patients – instead they received training either on the job or through life experience. The study used focus groups for data collection. Carers said that there were two types of knowledge that caregivers had that were effective in dealing with dementia patients: behavior centred knowledge – knowing recommended approaches to use with specific behavioural symptoms of dementia and person centred knowledge – knowing the residents well enough that they could look beyond the behaviour of the person (Rasin and Kautz. 2007 p.33-34).

They felt that the person centred knowledge was the strongest and most effective in caring for a person with dementia. From this study they made several recommendations for nursing:

· get to know the resident so you can determine what might be causing the disruptive behaviour.

· Giving individualised care for the residents can increase their quality of life.

· Caregivers should be taught how to incorporate patients life stories into their treatment plans to help them understand why the behaviour is being exhibited.

· Caregivers who understand and use person centred knowledge need to be acknowledged (Rasin and Kautz p.36).

A person centred approach was used in John’s treatment. He was encouraged to talk about his past and his wife was able to provide a lot of useful details which allowed John to be seen and treated as a ‘whole person’. It did also allow staff to make sense of some of the behaviour displayed by John.

Hepburn et al (2007) researched another way of effectively educating family members. They looked at a transportable psycho-education program geared towards helping to reduce caregivers stress. Several programs are spotlighted in this article. What they found was that a one to one behaviour management program given by home support team help to reduce the burden on caregivers and help to reduce depression. This program combined education with counselling. With the knowledge given to families, it was possible to delay the hospitalisation of the patient with dementia. (Hepburn et al, p.31-35)

Most caregivers are women, at least partly because it is a role that all women are expected to play in most societies. Doress-Wortens (1994) researched the effects of caregivers’ stress on women who already had multiple roles. They found that the stress in certain types of care giving situations were higher than others – e.g. when the caregiver involved personal care or dealing with a family member with dementia, they tended to experience more stress. A family member who was physically frail and needed minimal help was less stressful. John’s wife stress levels decreased with experience of looking after him – this information was apparent from reading of previous case notes. From this study it was apparent that women handle many different situations and they need coping strategies when they add the care of an ill family member to the set of tasks they perform.

Evaluation:

It is important to evaluate John’s care plan with regard to establishing the best possible attention for him. This has been done with reference to the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellences (2006). According to NICHE (2006) there were 700,000 cases of dementia in the United Kingdom and there are approximately a million caregivers for them. As a result of these figures NICHE provided recommendations for those dealing with patients who have dementia.

NICHE Recommendation 1 : A coordinated and integrated approach between health and social care to treat and care for patients with dementia and carers.

John’s care : John has received the care of a specialist team who are trained to coordinate the day to day assessment and management of his condition. This comprised doctors, nurses, psychiatric team. Each professional provides guidance and support both for John and his family. His wife receives education and assistance with techniques on how to handle his aggression at home. Because she is his main carer at home, she has been given details of support groups where she will be able to get additional advice.

NICHE Recommendation 2 : The needs of carers should be assessed and support should be offered as part of the overall plan.

John’s care : It is important for staff from the dementia ward to offer support and help John’s wife deal with his physical and verbally aggressive behaviour. Caplan, G.A. Et al (2006) states that families need to be given clear information about the disease trajectory , complications of dementia and limited treatment available.

John and his wife have been married for 54 years and have no children. The emotions of the medical prognosis need to be dealt with. Schulz et al (2003) cited in Ouldred and Bryant (2008) has found that the progression of dementia confronts families with difficult decisions and they need to be supported through this difficult period. It is important to receive pre-bereavement counselling which can lead to better adjustment post-bereavement. Bright (2008) researched the quality of elderly care of those who have dementia as they move into end of life situations. He pointed out that palliative care is not as developed for dementia as it is for cancer so levels of care will vary between different geographical regions.

It is difficult for John’s wife to deal with the stress that comes from living with a man she has known for so many years as his life deteriorates. She has been advised where to gain support where needed. Support groups can bring enormous relief and help to deal with some of the challenges of the caring role.

NICHE Recommendation 3 : Memory assessment should be given to all patients with dementia.

John’ care : The Pain Management Team kept close observations using the Abbey Rating Scale and weekly evaluations on John were used to get his pain under control (see attachment 2). Wood (2002) states that the nurse’s role in pain management is vital, therefore, nurses should be fully educated and trained to recognise when patients are in pain.

NICHE Recommendation 4: People with dementia should not be denied services they need because of their age.

John’s care : The dementia ward is staffed by healthcare workers who are trained to work with patients with dementia and there is an understanding of what is required in each situation. This works on the person centred approach. Staff work with John on a regular basis and many get to know him well. The staff can see when he is getting anxious and angry and can intervene as appropriate. As stated by Fitzpatrick and Roberts (2004) healthcare professionals caring for older people require a range of core skills and knowledge, with explicit attention to the principles of patient and family-centred care, promoting autonomy, dignity and respect, along with good communication skills.

In conclusion, there has been a positive outcome after John’s assessment on the dementia ward. Aggressive outbursts are less frequent and this makes a better quality of time for John with his wife, family and friends. He still tries hard to be independent.

Alzheimer’s Society Information sheet 436, 525. Available to download from:

hhtp:/www.alzheimers.org.uk

Bright, L. (2005). Palliative care for people with dementia. Management Matters Available to download from

http:// . [28 March2008}

Bephage, G. (2005). Quality sleep in older people: the nursing care role. British Journal of Nursing. Vol. 14 (4) pp.205-210

Bephage, G. (2007). Care approaches to sleeplessness & dementia. Nursing & Residential Care. Vol. 9 (12) pp. 571-573.

Caplan, G.A., Meller, A., Squires, B., Chan, S., Willet, W. (2006). Advance care planning and hospital in the nursing home. Age Ageing. Vol. 35 (6) pp. 581-585.

Chambers, M. & Conner, S.L. (2002). User-friendly technology to help family carers cope. Journal of Advanced Nursing . Vol. 40 (5) pp. 568-577.

Cook, A.K., Niven, C.A., Downs, M.G. (1999). Assessing the pain of people with cognitive impairment. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry . Vol. 14 (6) pp.421-425.

Cunningham, C. (2006). Managing pain in patients with dementia in hospital. Nursing Standard. Vol. 20 (46) pp.54-59

Doress-Wortes, P.B. (1994). Adding elder care to women’s multiple roles: a critical review of the caregiver stress and multiple roles literatures. Journal of Research . Vol. 31. pp.1-6.

Fitzpatrick, J.M. & Roberts, J.D. (2004). Challenges for care homes: Education and training of healthcare assistants. British Journal of Nursing . Vol. 13 (21) pp.1258-1260

Gloth, F.M. (2001). Pain management in older adults: prevention and treatment. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. Vol. 49 (2) pp.188-199.

Jaques, A. Jackson, G.A. (2000) Understanding Dementia 3 rd ed Churchill, Livingstone, London. pp.235-269, p. 336

Hepburn, K. Lewis, M. Tomatore, J. Sherman, C.W. & Bremner, K.L. (2007). The savvy caregivers program: The demonstrated effectiveness of a transportable dementia caregiver psycho education program. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. (2007)

Vol. 33 pp. 30-37.

Kaasalainen, S. (2007) Pain assessment in older adults with dementia: Using behavioural observation methods in clinical practice. Journal of gerontological Nursing Vol. 33 (6) pp. 6-10

Lewis, M.M. & Trzinski,A. (2006). Counselling older adults with dementia who are dealing with death: Innovative interventions for practitioners. Death Studies . Vol .30 (8)npp. 777-787

National Institute for health and Clinical Excellence (NHS) and Social Care Institute for Excellent (SCIE) (2006) NICE SCIE guidelines to improve care of people with dementia. Available to download from http://www.nice.org.uk/nice/media/pdf/2006-052 [Assessed 13/03/08]

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke NINDS Multi-Infarct Dementia Information Page. Available to download from http:/wwwninds.nih.gov/disorders

Nazarko, L. (2007). Behaviour that challenges: types and treatment. British Journal Of Healthcare Assistants . Vol. 1 (3) pp116-119

Ouldred, E. & Bryant, C. (2008). Dementia Care. Part 3: end-of-life care for people with advanced dementia. British Journal of Nursing. Vol. 17 (5) pp. 308-314

Rasin,J & Kautz, D. (2007). Knowing the resident with dementia: Perspectives of assisted living facility caregivers. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. Vol. 33 (9) pp.30-36.

SA Carers. (2005). Understanding the role of the family carers in healthcare. Available to download from http://www.carers-sa.asn.au/pdf_files . [Assessed 15/03/08]

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (2006) Guideline 86: Management of Patients With Dementia. Edinburgh, SIGN.

Smith, M. (2005). Pain assessment in nonverbal older adults with advanced dementia. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. Vol 41 Available to download from http://www.questia.com

Stokes, G. (2000). Challenging Behaviour In Dementia. A Person Centred Approach. Oxon Winslow-press Ltd. pp.206

Weaver, D. (2007). Behavioural Changes: Dementia & Its interventions. Nursing & Residential Care. Vol. 9 (8) pp. 375-377

Woods, S. (20020. Nursing care & implications for nursing. Nursing Times. Vol. 98 (40) pp. 39-42

Bibliography

Abbey, J. (2004).The Abbey pain scale: a 1-minute numerical indicator for people with end-stage dementia. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. Vol.10 (1) pp6-13

DeWaters, T. & Popovich, J. (2003). An evaluation of clinical tools to measure pain in older people with cognitive impairment. British Journal of Community Nursing. Vol. 8 (5) pp226-234

Dingwall, L. (2007). Medication issues for nursing older people (part 1). Nursing Older People. Vol. 19 (1) pp25-35

Evers, C. (2008). Positive dementia care: taking perspective. Nursing & Residential Care. Vol. 10 (4) pp184-187

Hobson, P. (2008). Understanding dementia: developing person-centred communication. British Journal of Healthcare Assistants. Vol. 2 (4) pp162-164

Kirkwood, T. Dementia Reconsidered: A person comes first. (2004). Open University Press U.K.

- Advanced Life Support

- Endocrinology

- Gastroenterology

- Infectious disease

- Intensive care

- Palliative Care

- Respiratory

- Rheumatology

- Haematology

- Endocrine surgery

- General surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Ophthalmology

- Plastic surgery

- Vascular surgery

- Abdo examination

- Cardio examination

- Neurolo examination

- Resp examination

- Rheum examination

- Vasc exacmination

- Other examinations

- Clinical Cases

- Communication skills

- Prescribing

Dementia case study with questions and answers

Dementia case study with questions and answers

Common dementia exam questions for medical finals, OSCEs and MRCP PACES

The case below illustrates the key features in the assessment of a patient with dementia or undiagnosed memory decline. It works through history, examination and investigations – click on the plus symbols to see the answers to each question

Part 1: Mavis

- Mavis is an 84-year old lady, referred to you in the memory clinic for assessment of memory impairment. She attends in the company of her son and daughter-in-law.

- On the pre-clinic questionnaire her son has reported a severe deterioration in all aspects of her cognition over the past 12 months.

- The patient herself acknowledges that there have been memory problems, but feels it is just her short term memory that is an issue.

Question 1.

- To begin the history, start broadly. Build rapport and establish both the patient’s view on memory impairment (if any) and the family’s (or other collateral history).

- Patient’s (and collateral) view of memory decline

- Biographical history

- Objective view of memory decline (e.g. knowledge of current affairs)

- Impact of memory decline on day-to-day living and hobbies

- Social history, including safety and driving

- General medical history (especially medications)

- See below for details on these…

Question 2.

- Is it for everything or are specific details missed out/glossed over?

- Try to pin down specific details (e.g. names of people/places).

- At what time in chronological order do things start to get hazy?

Question 3.

- If under 12 years this will lead to additional point being awarded on some cognitive tests

- Ask about long term memories, e.g. wedding day or different jobs

- Then move on to more recent memories, e.g. last holiday

Question 4.

- If your patient watches the news/read newspapers on a regular basis, ask them to recount the headlines from the past few days.

- Be sure to look for specifics to prevent your patient masking memory deficiencies with broad statements. For example: “The government are incompetent, aren’t they?!” should be clarified by pinning down exactly why they are incompetent, for example: “Jeremy Hunt”.

- If they like to read, can they recall plotlines from current books or items from magazines?

- If they watch TV, can they recount recent plot lines from soaps, or formats of quiz shows?

Question 5.

- Ask about hobbies and other daily activities, and whether or not these have declined recently.

- If your patient no longer participates in a particular hobby, find out why: is it as a result of a physical impairment (e.g. arthritis making cooking difficult), or as the result of a loss of interest/ability to complete tasks (e.g. no longer able to complete crosswords/puzzles).

- Once you have a good idea of the memory decline itself, begin to ask about other features. Including a social and general medical history.

Question 6.

- Review their social history and current set-up, and also subjective assessments from both patient and family over whether or not the current arrangements are safe and sustainable as they are.

- Previous and ongoing alcohol intake

- Smoking history

- Still driving (and if so, how safe that is considered to be from collateral history)

- Who else is at home

- Any package of care

- Upstairs/downstairs living

- Meal arrangements (and whether weight is being sustained).

- Of all these issues, that of driving is perhaps one of the most important, as any ultimate diagnosis of dementia must be informed (by law) to both the DVLA and also the patient’s insurers. If you feel they are still safe to drive despite the diagnosis, you may be asked to provide a report to the DVLA to support this viewpoint.

Now perform a more generalised history, to include past medical history and – more importantly – a drug history.

Question 7.

- Oxybutynin, commonly used in primary care for overactive bladder (anticholinergic side effects)

- Also see how the medications are given (e.g. Dossett box)

- Are lots of full packets found around the house?

Part 2: The History

On taking a history you have found:

- Mavis was able to give a moderately detailed biographical history, but struggled with details extending as far back as the location of her wedding, and also her main jobs throughout her life.

- After prompting from her family, she was able to supply more information, but it was not always entirely accurate.

- Her main hobby was knitting, and it was noted that she had been able to successfully knit a bobble hat for her great-grand child as recently as last month, although it had taken her considerably longer to complete than it might have done a few years previously, and it was a comparatively basic design compared to what she has been able to create previously.

- She has a few children living in the area, who would frequently pop in with shopping, but there had been times when they arrived to find that she was packed and in her coat, stating that she was “just getting ready to go home again”.

- She had been helping occasionally with the school run, but then a couple of weekends ago she had called up one of her sons – just before she was due to drive over for Sunday lunch – and said that she could not remember how to drive to his house.

- Ever since then, they had confiscated her keys to make sure she couldn’t drive. Although she liked to read the paper every day, she could not recall any recent major news events. Before proceeding to examine her, you note that the GP referral letter has stated that her dementia screen investigations have been completed.

Question 8.

- Raised WCC suggests infection as a cause of acute confusion

- Uraemia and other electrolyte disturbances can cause a persistent confusion.

- Again, to help rule out acute infection/inflammatory conditions

- Liver failure can cause hyperammonaemia, which can cause a persistent confusion.

- Hyper- or hypothyroidism can cause confusion.

- B12 deficiency is an easily missed and reversible cause of dementia.

- This looks for space occupying lesions/hydrocephalus which may cause confusion.

- This can also help to determine the degree of any vascular component of an ultimately diagnosed dementia.

Part 3: Examination

- With the exception of age-related involutional changes on the CT head (noted to have minimal white matter changes/small vessel disease), all the dementia screen bloods are reassuring.

- You next decide to perform a physical examination of Mavis.

Question 9.

- Important physical findings that are of particular relevance to dementia, are looking for other diseases that may have an effect on cognition.

- To look for evidence of stroke – unlikely in this case given the CT head

- Gait (shuffling) and limb movements (tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia)

- Affect is also important here and may also point to underlying depression

- Pay attention to vertical gaze palsy, as in the context of Parkinsonism this may represent a Parkinson plus condition (e.g. progressive supranuclear palsy).

- It is also useful to look at observations including blood pressure (may be overmedicated and at risk of falls from syncope) and postural blood pressure (again, may indicate overmedication but is also associated with Parkinson plus syndromes e.g. MSA)

Part 4: Cognitive Testing

- On examination she is alert and well, mobilising independently around the clinic waiting room area. A neurological examination was normal throughout, and there were no other major pathologies found on a general examination.

- You now proceed to cognitive testing:

Question 10.

- Click here for details on the MOCA

- Click here for details on the MMSE

- Click here for details on the CLOX test

Part 5: Diagnosis

- Mavis scores 14/30 on a MOCA, losing marks throughout multiple domains of cognition.

Question 11.

- Given the progressive nature of symptoms described by the family, the impairment over multiple domains on cognitive testing, and the impact on daily living that this is starting to have (e.g. packing and getting ready to leave her own home, mistakenly believing she is somewhere else), coupled with the results from her dementia screen, this is most likely an Alzheimer’s type dementia .

Question 12.

- You should proceed by establishing whether or not Mavis would like to be given a formal diagnosis, and if so, explain the above.

- You should review her lying and standing BP and ECG, and – if these give no contraindications – suggest a trial of treatment with an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, such as donepezil.

- It is important to note the potential side effects – the most distressing of which are related to issues of incontinence.

- If available, put her in touch with support groups

- Given the history of forgetting routes before even getting into the care, advise the patient that she should stop driving and that they need to inform the DVLA of this (for now, we will skip over the depravation of liberty issues that the premature confiscation of keys performed by the family has caused…)

- The GP should be informed of the new diagnosis, and if there are concerns over safety, review by social services for potential support should be arranged.

- Follow-up is advisable over the next few months to see whether the trial of treatment has been beneficial, and whether side effects have been well-tolerated.

Now click here to learn more about dementia

Perfect revision for medical students, finals, osces and mrcp paces, …or click here to learn about the diagnosis and management of delirium.

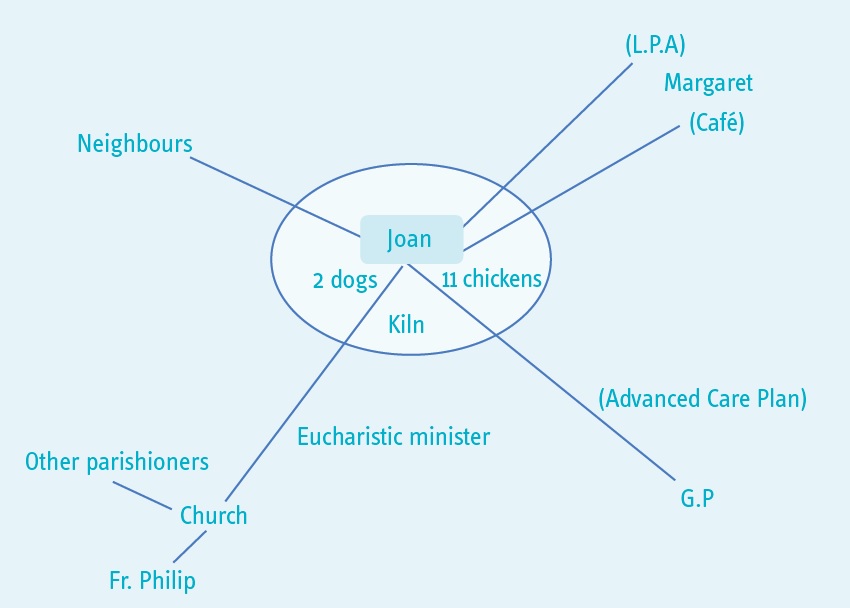

Case study 3: Joan

Download the Full Case Study for Joan PDF file (58KB)

Download the Vignette for Joan PDF file (49KB)

Name: Joan O’Leary

Gender: Female

Ethnicity: White Irish

Religion: Catholic

Disability: dementia with Lewy Bodies

First language: English

Family: estranged and in Ireland

Location: village in South West

Joan lives in a house in a small village. She has lived there for 28 years. She has two dogs and 11 chickens. Joan has always been quite private but is well known in her village. She goes to the nearby town on the bus to church, visits the local shop and community café, and goes away frequently. Joan goes for a long walk with her dogs each day. Joan hadn’t been to her GP for 6 years.

The café owner, Margaret, was worried about Joan. Joan has appeared very forgetful and disorientated. She has been seen in the village wearing her slippers and her neighbours have seen her out late at night with her dogs. Margaret went to Joan’s house and wasn’t allowed in but thought there was quite a strong smell.

Margaret phoned the GP in the village who went round to Joan’s house and persuaded her to have some tests. She has been diagnosed with moderate dementia with Lewy Bodies.

The GP phoned social services and you go out to do an assessment.

Download the Ecogram for Joan PDF file (48KB)

You told me that you didn’t really want to have an assessment. I explained that your GP had asked me to talk to you about what is happening for you at the moment because you have been diagnosed with dementia. You agreed to the assessment but you don’t want to have lots of information about you written down. These are the main things that you were happy for me to know.

At the moment you have capacity to make decisions about whether to have support or not. In the future you may find it more difficult to make decisions or not be able to make a particular decision. We talked about you arranging a lasting power of attorney and also doing an advanced care plan.

What’s important to you?

You said that you are quite a private person. You have two dogs and 11 chickens. You like to walk the dogs, go to the café and go to church in Lyme Regis. You take eggs to the café for Margaret (the owner) to sell.

You are a talented artist and have a small pottery shed and kiln in the garden.

You like to plan trips to different local areas and travel using the bus.

Your family is in Ireland and you haven’t seen them for many years. Your Catholic faith is important to you. You are a Eucharistic minister and you take holy communion to parishioners who can’t get to church.

What’s happening for you at the moment?

Your GP asked me to come and see you because you have been diagnosed with moderate dementia with Lewy Bodies.

You told me that you understand this is similar to Parkinson’s disease. You have noticed that your muscles have been aching and that you are not sleeping well.

The GP explained to me that you might find that you are unsteady at times or have tremors, and you might have some hallucinations, as these are common with this kind of dementia.

Margaret told me that you have been into the village wearing your slippers and that your neighbours have noticed you being out late at night which you agreed is unusual for you. However, you also told me that what you do is your own business. We talked about the risks that are attached to you going out late or not wearing appropriate clothing. You told me that you don’t think it is a problem, as you have always walked a lot and always find your way home. Also you said that you have the dogs with you when you are out and they know their way home. You already used reminders around the house so you said you would put a reminder on the front door to check your coat and shoes.

We talked about how you were managing day to day. You told me that you think you are managing well. However you haven’t been able to put the rubbish out or to clean out the chickens. You also have not been able to clean the bathroom. This is because you sometimes feel dizzy and your arms ache.

What is the impact on you?

You are concerned that people, like me, might start interfering with your life because of your illness.

What would you like to happen in the future?

You said that you want to continue to live in your home, looking after your animals, and doing the things that you currently do. We talked about what you think will happen and you said that you knew you will become less well. If you did need help in the future, you would like to arrange this yourself. We talked about having a personal assistant in the future.

How might we achieve this?

We talked about the importance of you having the right support in the future. You agreed that I could share this assessment with Margaret and your GP so that if you are not well enough to ask for advice or assistance in the future, they can ring the council. You will discuss a lasting power of attorney for finances, and health and care for Margaret. And you will do an advanced care plan with your GP. You will also talk to your GP about any medical support that might be available now, for example memory clinic and help with sleeping.

We also called your Parish Priest, Father Philip, and let him know that you have been diagnosed with dementia. He will ask a parishioner to give you a lift to church if you aren’t able to go on the bus.

You agreed to some help with keeping the animals and putting the rubbish out. Margaret and you will make an advert to put in the café window.

What strengths and support networks do you have to help you?

You said you are a very independent person. You have managed your home and finances for many years. You are managing well despite your illness and have strategies in place for things you might forget. You are active and have wide interests and talents. You also earn money through selling eggs. You contribute to the community through the parish. You are familiar with your local area and are used to travelling around.

You have a good relationship with Margaret, with your parish priest and with your GP. They are all willing and able to offer support.

Social care assessor conclusion

You have recently been diagnosed with dementia. This is starting to have an impact on your life and because of the nature of the illness the impact will increase as time goes on.

You have a lot of strengths to draw on and a good support network. You want to remain independent and, although there are some concerns about how you are managing, these are currently relatively minor and you have identified how to minimise them.

It is important that you plan ahead so that you remain in control of what happens and so that you can continue to achieve what matters to you for as long as possible.

Eligibility decision

You are not currently eligible for care and support under the Care Act 2014 because you can currently manage all day to day activities, apart from needing some help with maintaining your home. However, we have done a care and support plan that says what you will do to get help with the house and to plan for the future.

What’s happening next

See care and support plan .

Download the care and support plan document PDF file (178KB)

- Equal opportunities

- Complaints procedure

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookie policy

- Accessibility

A sample case study: Mrs Brown

On this page, social work report, social work report: background, social work report: social history, social work report: current function, social work report: the current risks, social work report: attempts to trial least restrictive options, social work report: recommendation, medical report, medical report: background information, medical report: financial and legal affairs, medical report: general living circumstances.

This is a fictitious case that has been designed for educative purposes.

Mrs Beryl Brown URN102030 20 Hume Road, Melbourne, 3000 DOB: 01/11/33

Date of application: 20 August 2019

Mrs Beryl Brown (01/11/33) is an 85 year old woman who was admitted to the Hume Hospital by ambulance after being found by her youngest daughter lying in front of her toilet. Her daughter estimates that she may have been on the ground overnight. On admission, Mrs Brown was diagnosed with a right sided stroke, which has left her with moderate weakness in her left arm and leg. A diagnosis of vascular dementia was also made, which is overlaid on a pre-existing diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (2016). Please refer to the attached medical report for further details.

I understand that Mrs Brown has been residing in her own home, a two-story terrace house in Melbourne, for almost 60 years. She has lived alone since her husband died two years ago following a cardiac arrest. She has two daughters. The youngest daughter Jean has lived with her for the past year, after she lost her job. The eldest daughter Catherine lives on the Gold Coast with her family. Mrs Brown is a retired school teacher and she and both daughters describe her as a very private woman who has never enjoyed having visitors in her home. Mrs Brown took much encouragement to accept cleaning and shopping assistance once a week after her most recent admission; however, she does not agree to increase service provision. Jean has Enduring Power of Attorney (EPOA) paperwork that indicates that Mrs Brown appointed her under an EPOA two years ago. She does not appear to have appointed a medical treatment decision maker or any other decision-supporter.

I also understand from conversations with her daughters that Jean and Mrs Brown have always been very close and that there is a history of long-standing conflict between Catherine and Jean. This was exacerbated by the death of their father. Both daughters state they understand the impact of the stroke on their mother’s physical and cognitive functioning, but they do not agree on a discharge destination. Mrs Brown lacks insight into her care needs and says she will be fine once she gets back into her own home. Repeated attempts to discuss options with all parties in the same room have not resulted in a decision that is agreeable to all parties.

Mrs Brown has a history of Alzheimer’s disease; type II diabetes – insulin dependent; hypertension; high cholesterol and osteoarthritis. She has had two recent admissions to hospital for a urinary tract infection and a fall in the context of low blood sugars. She is currently requiring one to two people to assist her into and out of bed and one person with managing tasks associated with post-toilet hygiene. She can walk slowly for short distances with a four-wheel frame with one person to supervise. She benefits from prompting to use her frame; she needs someone to cut her food and to set her up to eat and drink regularly and to manage her medication routine. She requires one person to assist her to manage her insulin twice daily.

The team believe that Mrs Brown’s capacity for functional improvement has plateaued in the last ten days. They recommend that it is in her best interests to be discharged to a residential care setting due to her need for one to two people to provide assistance with the core tasks associated with daily living. Mrs Brown is adamant that she wants to return home to live with Jean who she states can look after her. Jean, who has a history of chronic back pain, has required several admissions to hospital over the past five years, and states she wants to be able to care for her mother at home. Jean states she is reluctant to agree to extra services as her mother would not want this. Her sister Catherine is concerned that Jean has not been coping and states that given this is the third admission to hospital in a period of few months, believes it is now time for her mother to enter residential care. Catherine states that she is very opposed to her mother being discharged home.

Mrs Brown is at high risk of experiencing falls. She has reduced awareness of the left side of her body and her ability to plan and process information has been affected by her stroke. She is now requiring one to two people to assist with all her tasks of daily living and she lacks insight into these deficits. Mrs Brown is also at risk of further significant functional decline which may exacerbate Jean’s back pain. Jean has stated she is very worried about where she will live if her mother is to enter residential care.

We have convened two family meetings with Mrs Brown, both her daughters and several members of the multi-disciplinary team. The outcome of the first meeting saw all parties agree for the ward to provide personalised carer training to Jean with the aim of trialling a discharge home. During this training Jean reported significant pain when transferring her mother from the bed and stated she would prefer to leave her mother in bed until she was well enough to get out with less support.

The team provided education to both Jean and Catherine about the progressive impact of their mother’s multiple conditions on her functioning. The occupational therapist completed a home visit and recommended that the downstairs shower be modified so that a commode can be placed in it safely and the existing dining room be converted into a bedroom for Mrs Brown. Mrs Brown stated she would not pay for these modifications and Jean stated she did not wish to go against her mother’s wishes. The team encouraged Mrs Brown to consider developing a back-up plan and explore residential care options close to her home so that Jean could visit often if the discharge home failed. Mrs Brown and Jean refused to consent to proceed with an Aged Care Assessment that would enable Catherine to waitlist her mother’s name at suitable aged care facilities. We proceeded with organising a trial overnight visit. Unfortunately, this visit was not successful as Jean and Catherine, who remained in Melbourne to provide assistance, found it very difficult to provide care without the use of an accessible bathroom. Mrs Brown remains adamant that she will remain at home. The team is continuing to work with the family to maximise Mrs Brown’s independence, but they believe that it is unlikely this will improve. I have spent time with Jean to explore her adjustment to the situation, and provided her with information on community support services and residential care services. I have provided her with information on the Transition Care Program which can assist families to work through all the logistics. I have provided her with more information on where she could access further counselling to explore her concerns. I have sought advice on the process and legislative requirements from the Office of the Public Advocate’s Advice Service. I discussed this process with the treating team and we decided that it was time to lodge an application for guardianship to VCAT.

The treating team believe they have exhausted all least restrictive alternatives and that a guardianship order is required to make a decision on Mrs Brown’s discharge destination and access to services. The team recommend that the Public Advocate be appointed as Mrs Brown’s guardian of last resort. We believe that this is the most suitable arrangement as her daughters are not in agreement about what is in their mother’s best interests. We also believe that there is a potential conflict of interest as Jean has expressed significant concern that her mother’s relocation to residential care will have an impact on her own living arrangements.

Mrs Brown’s medical history includes Alzheimer’s disease; type II diabetes; hypertension; high cholesterol and osteoarthritis. She was admitted to Hume Hospital on 3 March 2019 following a stroke that resulted in moderate left arm and leg weakness. This admission was the third hospital admission in the past year. Other admissions have been for a urinary tract infection, and a fall in the context hypoglycaemia (low blood sugars), both of which were complicated by episodes of delirium.

She was transferred to the subacute site under my care, a week post her admission, for slow-stream rehabilitation, cognitive assessment and discharge planning.

Mrs Brown was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease by Dr Joanne Winters, Geriatrician, in April 2016. At that time, Mrs Brown scored 21/30 on the Standardised Mini-Mental State Examination (SMMSE). During this admission, Mrs Brown scored 15/30. I have undertaken cognitive assessment and agree with the diagnosis; further cognitive decline has occurred in the context of the recent stroke. There are global cognitive deficits, but primarily affecting memory, attention and executive function (planning, problem solving, mental flexibility and abstract reasoning). The most recent CT-Brain scan shows generalised atrophy along with evidence of the new stroke affecting the right frontal lobe. My assessments suggest moderate to severe mixed Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia.

While able to recall some key aspects of her financial affairs, including the general monetary value of her pension and regular expenses, Mrs Brown was unable to account for recent expenditure (for repairs to her home) or provide an estimate of its value, and had difficulty describing her investments. In addition, I consider that she would be unable to make complex financial decisions due to her level of cognitive impairment. Accordingly, I am of the view that Mrs Brown now lacks capacity to make financial decisions.

Mrs Brown states that she previously made an Enduring Power of Attorney (EPOA) but could no longer recall aspects of the EPOA, such as when it would commence and the nature of the attorney’s powers. Moreover, she confused the EPOA with her will. Her understanding of these matters did not improve with education, and therefore I consider that she no longer has capacity to execute or revoke an EPOA.

Mrs Brown acknowledges that she needs some assistance but lacks insight into the type of assistance that she requires, apart from home help for cleaning and shopping. She does not appreciate her risk of falling. She is unable to get in and out of bed without at least one person assisting her. She frequently forgets to use her gait aid when mobilising and is not able to describe how she would seek help in the event of falling. She is not able to identify or describe how she would manage her blood sugar levels, and this has not improved with education. Accordingly, I consider that she lacks capacity to make decisions about accommodation arrangements and services.

Mrs Brown does not agree with the treating team’s recommendation to move into residential care and maintains her preference to return home. This is in spite of a failed overnight trial at home with both her daughters assisting her. Unfortunately, she was unable to get out of bed to get to the toilet and required two people to assist her to do so in the morning. In light of these matters, and in the context of family disagreement regarding the matter, the team recommends that the Office of the Public Advocate be appointed as a guardian of last resort.

Reviewed 22 July 2022

- Hospitals & health services

- Public hospitals in Victoria

- Patient care

- Ambulance and patient transport

- Non-emergency patient transport

- Non-emergency patient transport review

- NEPT legislation and clinical practice protocols

- Non-emergency patient transport licensing

- NEPT licensing fees

- NEPT services information and guidance

- First Aid Services

- First aid licences

- First aid services information and guidance

- First aid service fees

- Victorian State Trauma System

- Acute medicine

- Emergency care

- Surgical services

- Better at Home

- Critical care

- Hospital in the Home

- Virtual care (Telehealth)

- Perinatal and reproductive services

- Rehabilitation and complex care

- Renal health

- Renal services in Victoria

- Funding for renal services

- Different approaches to haemodialysis

- Specialist clinics

- Access to non-admitted services

- Minimum referral information

- Communication toolkit

- Integrated care

- HealthLinks: Chronic Care

- Community Health Integrated Program (CHIP) guidelines

- Service coordination in Victoria

- Victorian integrated care online resources

- Specialist clinics programs

- Specialist clinics reform

- Specialty diagnostics, therapeutics and programs

- Older people in hospital

- End of life and palliative care in Victoria

- Voluntary assisted dying

- Quality, safety and service improvement

- Planned surgery recovery and reform program

- Digital Health

- Roadmap and Maturity Model

- Standards and guidelines

- Policies and frameworks

- Health Information Sharing Legislation Reform

- My Health Record

- Public hospital accreditation in Victoria

- Credentialing for senior medical staff in Victoria

- Clinical risk management

- Preventing infections in health services

- Healthy choices

- Victorian Perinatal Data Collection

- Rural health

- Improving Access to Primary Care in Rural and Remote Areas Initiative

- Rural x-ray services

- Rural health regions and locations

- Rural and regional medical director role

- Victorian Patient Transport Assistance Scheme

- Rural and isolated practice registered nurses

- Urgent care in regional and rural Victoria

- Private health service establishments

- Private hospitals

- Day procedure centres

- Mobile health services

- Fees for private health service establishments in Victoria

- Design resources for private health service establishments

- Professional standards in private health service establishments

- Legislation updates for private health service establishments

- Complaints about private health service establishments

- Cosmetic procedures

- Guideline for providers of liposuction

- Private hospital funding agreement

- Boards and governance

- About health service boards in Victoria

- Information and education

- Education resources for boards

- Sector leadership

- Data, reporting and analytics

- Health data standards and systems

- Funding, performance and accountability

- Statements of Priorities

- Performance monitoring framework

- Integrity governance framework and assessment tool

- Pricing and funding framework

- Patient fees and charges

- Fees and charges for admitted patients

- Non-admitted patients - fees and charges

- Other services

- Planning and infrastructure

- Sustainability in Healthcare

- Medical equipment asset management framework

- Health system design, service and infrastructure planning

- Complementary service and locality planning

- Primary & community health

- Primary care

- Community pharmacist pilot

- EOI - Victorian Community Pharmacist Statewide Pilot

- Victorian Community Pharmacist Statewide Pilot – Resources for pharmacists

- Emergency Response Planning Tool

- Working with general practice

- Victorian Supercare Pharmacies

- NURSE-ON-CALL

- Priority Primary Care Centres

- Local Public Health Units

- Community health

- Community health services

- Community health pride

- Registration and governance of community health centres

- Community Health Directory

- Community Health Program in Victoria

- Community health population groups

- Dental health

- Access to public dental care services

- Victoria's public dental care fees

- Victoria's public dental care waiting list

- Dental health for SRS residents

- Dental health program reporting

- Smile Squad school dental program

- Maternal and Child Health Service

- Nursery Equipment Program

- Maternal and Child Health Service Framework

- Maternal and Child Health Service resources

- Child Development Information System

- Early parenting centres

- Maternal Child and Health Reporting, Funding and Data

- Baby bundle

- Sleep and settling

- Maternal and Child Health Workforce professional development

- Aboriginal Maternal and Child Health

- Public Dental and Community Health Program funding model review

- Public health

- Women's Health and Wellbeing Program

- Inquiry into Women's Pain

- Inquiry into Women's Pain submissions

- Support groups and programs

- About the program

- Victorian Women's Health Advisory Council

- Cemeteries and crematoria

- Cemetery trust member appointments

- Cemetery search

- Cemeteries and crematoria complaints

- Exhumations

- Governance and finance

- Cemetery grants

- Interments and memorials

- Land and development

- Legislation governing Victorian cemeteries and crematoria

- Cemeteries and crematoria publications

- Repatriations

- Rights of interment

- Medicines and Poisons Regulation

- Patient Schedule 8 treatment permits

- Schedule 8 MDMA and Schedule 8 psilocybine

- Schedule 9 permits for clinical trials

- Documents and forms to print or download

- Legislation and Approvals

- Frequently Asked Questions - Medicines and Poisons Regulation

- Health practitioners

- Licences and permits to possess (& possibly supply) scheduled substances

- Medicinal cannabis

- Pharmacotherapy (opioid replacement therapy)

- Recent updates

- Environmental health

- Improving childhood asthma management in Melbourne's inner west

- Climate and weather, and public health

- Environmental health in the community

- Environmental health in the home

- Environmental health professionals

- Face masks for environmental hazards

- Human health risk assessments

- Lead and human health

- Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)

- Pesticide use and pest control

- Food safety

- Information for community groups selling food to raise funds

- Food businesses

- Food safety information for consumers

- Food regulation in Victoria

- Food safety library

- Food allergens

- Introducing Standard 3.2.2A: Food safety management tools

- Immunisation

- Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) immunisation

- Seasonal influenza vaccine

- Immunisation schedule and vaccine eligibility criteria

- Ordering vaccine

- Immunisers in Victoria

- Immunisation provider information

- Cold chain management

- Adverse events following immunisation reporting

- Vaccine error management

- Vaccination for infants and children

- Vaccination for adolescents

- Vaccination program for adults

- Vaccination for special-risk groups

- Immunisation resources order form

- Victorian coverage rates for Victoria

- Infectious diseases guidelines & advice

- Infection control guidelines

- Disease information and advice

- Advice to the cruise industry: reporting infections

- Notifiable infectious diseases, conditions and micro-organisms

- Notification procedures for infectious diseases

- Infectious diseases surveillance in Victoria

- Germicidal ultraviolet light

- Protecting patient privacy in Victoria

- Population health systems

- Evidence and evaluation

- Health promotion

- Health status of Victorians

- Municipal public health and wellbeing planning

- Population screening

- Cancer screening

- Conditions not screened

- Improving outcomes in under-screened groups

- Infant hearing screening

- Newborn bloodspot screening

- Prenatal screening

- Screening registers

- Preventive health

- Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease prevention

- Eye health promotion

- Injury prevention

- Healthy eating

- Oral health promotion

- Physical activity

- Sexual health

- Sex worker health

- Decriminalisation of sex work

- Automatic mutual recognition

- Domestic smoke detectors

- Lasers, IPL and LED devices for cosmetic treatments and beauty therapy

- Victoria's regulatory framework for radiation

- Radiation newsletter

- Tobacco reforms

- Tobacco reform legislation and regulations

- E-cigarettes and vaping

- Quitting smoking and vaping

- Smoke-free and vape-free areas

- Building entrances

- Children's indoor play centres

- Public hospitals and health centres

- Children's recreational areas

- Playground equipment

- Skate parks

- Swimming pools

- Under-age sporting events

- Enclosed workplaces

- Government buildings

- Learning environments

- Outdoor dining

- Outdoor drinking areas

- Patrolled beaches

- Train platforms and bus and tram shelters

- Under-age music or dance events

- Tobacco and e-cigarette retailers

- Making a report or complaint

- Resources and factsheets

- Alternative water supplies

- Aquatic facilities

- Blue-green algae (cyanobacteria)

- Drinking water in Victoria

- Legionella risk management

- Private drinking water

- Recreational water use and possible health risks

- Water fluoridation

- Chief Health Officer

- About the Chief Health Officer

- Chief Health Officer publications

- Health alerts and advisories

- Mental health

- Mental Health and Wellbeing Act 2022

- Mental Health and Wellbeing Act 2022 Handbook

- Community information

- Mental Health and Wellbeing Act 2022 in your language

- About Victoria's mental health services

- Area-based services

- Statewide and specialist mental health services

- Mental Health Community Support Services

- Support and intervention services

- Language services - when to use them

- Access to mental health services across areas

- Transport for people in mental health services

- Practice and service quality

- Medical Treatment Planning and Decisions Act

- Service quality

- Specialist responses

- Mental health and wellbeing reform

- Reform activity updates

- Priority areas

- Latest news

- Working with consumers and carers

- Consumer and carer engagement

- Consumer and Carer Experience Surveys

- Family support and crisis plans

- Consumer and carer financial support

- Supporting children whose parents have a mental illness

- Supporting parents with a mental illness

- Prevention and promotion

- Early intervention in mental illness

- Mental health promotion in Victoria

- Suicide prevention in Victoria

- Priorities and transformation

- Supporting the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Victorians

- National mental health strategy

- Rights and advocacy

- Making a complaint about a mental health service

- Chief Psychiatrist

- About the Chief Psychiatrist

- Principles in the Mental Health and Wellbeing Act and the Chief Psychiatrist's guidelines

- Obligations under the Mental Health and Wellbeing Act 2022

- Reporting a failure to comply with the Mental Health and Wellbeing Act 2022

- Governance and committees

- Reporting obligations for clinical mental health and wellbeing services

- Mental health and wellbeing support

- Making a complaint and seeking advocacy

- Second psychiatric opinion and process of review by Chief Psychiatrist

- Office of the Chief Psychiatrist's reform activities and news

- Oversight of forensic mental health and wellbeing services

- Resources and reports

- Chief psychiatrist guidelines

- Chief Mental Health Nurse

- About Victoria's Chief Mental Health Nurse

- Best practice

- Reducing restrictive interventions

- Research and reporting

- Mental health performance reports

- Reporting requirements and business rules for clinical mental health services

- Alcohol & drugs

- Alcohol and other drug treatment services

- Overview of Victoria's alcohol and drug treatment system

- Pathways into alcohol and other drugs treatment

- Prevention and harm reduction

- Medically supervised injecting room

- Victoria's Take-Home Naloxone Program

- Community-based AOD treatment services in Victoria

- Residential treatment services

- Mildura statewide alcohol and drug residential treatment service

- Drug rehabilitation plan

- Hospital-based services

- Forensic services

- Pharmacotherapy treatment

- Services for Aboriginal people

- Services for young people

- Statewide and specialist services

- Compulsory treatment

- Family and peer support

- Public intoxication reform

- New public intoxication response services

- Policy, research and legislation

- Alcohol and drug research and data

- Legislation governing alcohol and other drug treatment

- Alcohol and other drug service standards and guidelines

- Alcohol and other drug client charter and resources

- Alcohol and other drug treatment principles

- Service quality and accreditation

- Alcohol and other drug program guidelines

- Maintenance pharmacotherapy

- Specialist Family Violence Advisor capacity building program in mental health and alcohol and other drug services - Victoria

- Alcohol and other drug workforce

- Learning and development

- Alcohol and other drug workforce Minimum Qualification Strategy

- Workforce data and planning

- Funding and reporting for alcohol and other drug services

- Funding of alcohol and other drugs services in Victoria

- Reporting requirements and business rules for alcohol and other drug services

- Drug alerts

- 25C-NBOMe and 4-FA sold as '2C-B'

- Novel stimulants sold as MDMA, cocaine or speed

- Protonitazene sold as ketamine

- High potency benzodiazepine tablets

- MDMA adulterated with PMMA

- 25B-NBOH sold as powdered 'LSD'

- Green 'UPS' pills containing N-ethylpentylone (no MDMA)

- N-ethylpentylone in cocaine

- Ageing & aged care

- Supporting independent living

- Low cost accommodation support programs

- Personal Alert Victoria

- Dementia services

- Victorian Aids and Equipment Program

- Residential aged care services

- Public sector residential aged care services

- Safety and quality in public sector residential aged care

- Physical and social environments

- Emergency preparedness in residential aged care services

- My Aged Care assessment services

- Home and Community Care Program for Younger People

- HACC data reporting

- HACC PYP fees policy and schedule of fees

- Wellbeing and participation

- Age-friendly Victoria

- Healthy ageing

- Seniors participation

- Dementia-friendly environments

- Designing for people with dementia

- Maintaining personal identity

- Personal enjoyment

- Interior design

- Dining areas, kitchens and eating

- Bedrooms and privacy

- Gardens and outdoor spaces

- Assistive technology

- Staff education and support

- Strategies, checklists and tools

- Our Strategic Plan 2023-27

- Our organisation

- Our secretary

- Leadership charter

- Our services

- Our vision and values

- Specialist offices

- Senior officers in health

- Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC)

- Gifts, benefits and hospitality policy

- Information Asset Register

- Health legislation

- Health legislation overview

- Health Complaints legislation

- Health Records Act

- Human Tissue Act 1982

- Public Health and Wellbeing Act 2008

- Voluntary Assisted Dying Act

- Victoria's pandemic management framework

- Independent Pandemic Management Advisory Committee

- Pandemic Order Register

- Our ministers

- Our role in emergencies

- State Health Emergency Response Arrangements

- Emergency type

- Department's responsibilities in emergencies

- Health services’ responsibilities in emergencies

- Aboriginal employment

- Current vacancies

- Employment programs for students and graduates

- Rise program

- Inclusion and diversity at the Department of Health

- Health workforce

- Working in health

- Information sharing and MARAM

- Child Safe Standards

- Regulatory functions

- Reviews of decisions

- Victorian Public Healthcare Awards

- Aboriginal healthcare workers

- Mental health workforce

- Lived and living experience workforces

- Engaging with lived and living experience workforces

- Our workforce, our future

- Nursing and midwifery

- Free nursing and midwifery study

- Additional funding for nursing and midwifery positions

- Becoming a nurse or midwife

- Undergraduate nursing and midwifery scholarships

- Undergraduate student employment programs

- Nursing and midwifery graduates

- Nursing and midwifery graduate sign-on bonus

- Working as a nurse or midwife

- Enrolled nurse to registered nurse transition scholarships

- Support for new nurse practitioners

- Postgraduate scholarships for nurses and midwives

- Nurse practitioners

- Returning to nursing or midwifery

- Refresher pathway for nurses and midwives

- Re-entry pathway scholarships for nurses and midwives

- Nursing and midwifery - legislation and regulation

- Nursing and midwifery program - health sector

- Allied health workforce

- Education and training

- Enterprise agreements

- Worker health and wellbeing

- Working with us

- Grants and programs

- Freedom of Information

- Part II - Information Statements

- Procurement policies

- Protective markings

- Health and medical research

- Sponsorship application information

- Publications

- Annual reports

- Fact sheets

- Strategies, plans and charters

- Policies, standards and guidelines

- Research and reports

- Forms and templates

- Communities

- Designing for Diversity

- Vulnerable children

- Vulnerable children - responsibilities of health professionals

- Identifying and responding to children at risk

- Pathway to good health for children in care

- Older people

- Aboriginal health

- Improving health for Victorians from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds

- Asylum seeker and refugee health in Victoria

- News and media hub

- Media releases

- Health alerts

- Feedback and complaints

- Make a payment

- Fees, charges and penalties subject to automatic indexation

- Our campaigns

Share this page

- Facebook , opens a new window

- X (formerly Twitter) , opens a new window

- LinkedIn , opens a new window

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Gridley K, Brooks J, Birks Y, et al. Improving care for people with dementia: development and initial feasibility study for evaluation of life story work in dementia care. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2016 Aug. (Health Services and Delivery Research, No. 4.23.)

Improving care for people with dementia: development and initial feasibility study for evaluation of life story work in dementia care.

Chapter 10 discussion and conclusions.

- Discussion of findings

Stage 1: literature review and qualitative work

- Both elements of stage 1 showed that LSW is not simple conceptually, nor is it easy to pin down its potential benefits. Personal, temporal and organisational challenges may prevent positive outcomes being achieved, and an individually tailored approach is essential to ensuring maximum benefit for different people at different times.

- The different models of LSW identified in the review and the theories of change that emerged echoed the different purposes of LSW identified in the qualitative work. Is LSW mainly about people preserving their own memories or is it to help staff learn about the person they are working with? Is its aim to improve QoL by reaffirming identity, or by personalising care and responding better to behaviour that challenges?

- We saw these tensions played out in care settings in the survey and in the feasibility study, where the focus was on LSW as a tool for care and for managing behaviour. This does not necessarily make LSW in those settings any less valuable, but it may narrow the scope for benefit. It also raises the question of whether or not the potential personal benefits might be better achieved earlier in the dementia journey, when people with dementia themselves may have more control over the process and final product.

- The experiences of people with dementia, family carers and professionals about good practice in LSW were consistent with messages from the literature review and, together, suggested a set of learning points for good practice (see Conclusions ).

Stage 2: surveys

The survey of services suggests that LSW has spread relatively widely, particularly in hospital assessment settings, albeit to a lesser extent in care homes.

We found wide variation between different services in the type of LSW they did, and in its overall objectives, including involvement of the person with dementia, whether it was past or forward looking and how it was used in the care setting. We saw throughout that these differences may reflect the different places on the dementia care pathway at which the services were located. Settings with an assessment and care planning focus tended to produce life story products that were less dynamic and sometimes designed specifically to capture information to pass on to other care settings. Care homes were more likely to be capturing information to inform everyday care and interactions with the person with dementia.

Across the board, however, the actual use of the life story product was not as common as might be hoped for. Doing LSW is one thing; using it to inform and improve care is clearly another.

The service survey emphasised the role of carers in doing LSW, and the survey of carers gave further detail. Although carers played an important part in services’ LSW, they were unlikely to be trained to do it beforehand. Carers were likely to report heavy involvement and, in some cases, had led the LSW. Again, however, the actual use of the life story by care staff, and even by the person with dementia and carers, was lower than might be expected.

Different models of LSW in the carers’ accounts echoed those found in the review, the qualitative work and the services survey, suggesting again two different types and uses of LSW.

Stage 2: feasibility study process

Our overall conclusion from this stage is that formal evaluation of LSW would be possible only with substantial staffing. Enabling people with dementia (and, to some extent, their family carers) to participate in a meaningful way meant that we used essentially qualitative methods to collect quantitative data. Working with people with dementia requires patience, and there will always be a high risk that data cannot be collected on a given day.

However, working in care homes and hospital wards is, of itself, labour intensive and runs the risk of ‘wasted’ researcher time. Contacting family members and other consultees relies on the goodwill of staff, and carers themselves often have busy/stressful lives and other priorities. Embedding researchers in the care settings is probably the best way to deal with these types of problems.