- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Preparation and Procedures Involved in Gender Affirmation Surgeries

If you or a loved one are considering gender affirmation surgery , you are probably wondering what steps you must go through before the surgery can be done. Let's look at what is required to be a candidate for these surgeries, the potential positive effects and side effects of hormonal therapy, and the types of surgeries that are available.

Gender affirmation surgery, also known as gender confirmation surgery, is performed to align or transition individuals with gender dysphoria to their true gender.

A transgender woman, man, or non-binary person may choose to undergo gender affirmation surgery.

The term "transexual" was previously used by the medical community to describe people who undergo gender affirmation surgery. The term is no longer accepted by many members of the trans community as it is often weaponized as a slur. While some trans people do identify as "transexual", it is best to use the term "transgender" to describe members of this community.

Transitioning

Transitioning may involve:

- Social transitioning : going by different pronouns, changing one’s style, adopting a new name, etc., to affirm one’s gender

- Medical transitioning : taking hormones and/or surgically removing or modifying genitals and reproductive organs

Transgender individuals do not need to undergo medical intervention to have valid identities.

Reasons for Undergoing Surgery

Many transgender people experience a marked incongruence between their gender and their assigned sex at birth. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has identified this as gender dysphoria.

Gender dysphoria is the distress some trans people feel when their appearance does not reflect their gender. Dysphoria can be the cause of poor mental health or trigger mental illness in transgender people.

For these individuals, social transitioning, hormone therapy, and gender confirmation surgery permit their outside appearance to match their true gender.

Steps Required Before Surgery

In addition to a comprehensive understanding of the procedures, hormones, and other risks involved in gender-affirming surgery, there are other steps that must be accomplished before surgery is performed. These steps are one way the medical community and insurance companies limit access to gender affirmative procedures.

Steps may include:

- Mental health evaluation : A mental health evaluation is required to look for any mental health concerns that could influence an individual’s mental state, and to assess a person’s readiness to undergo the physical and emotional stresses of the transition.

- Clear and consistent documentation of gender dysphoria

- A "real life" test : The individual must take on the role of their gender in everyday activities, both socially and professionally (known as “real-life experience” or “real-life test”).

Firstly, not all transgender experience physical body dysphoria. The “real life” test is also very dangerous to execute, as trans people have to make themselves vulnerable in public to be considered for affirmative procedures. When a trans person does not pass (easily identified as their gender), they can be clocked (found out to be transgender), putting them at risk for violence and discrimination.

Requiring trans people to conduct a “real-life” test despite the ongoing violence out transgender people face is extremely dangerous, especially because some transgender people only want surgery to lower their risk of experiencing transphobic violence.

Hormone Therapy & Transitioning

Hormone therapy involves taking progesterone, estrogen, or testosterone. An individual has to have undergone hormone therapy for a year before having gender affirmation surgery.

The purpose of hormone therapy is to change the physical appearance to reflect gender identity.

Effects of Testosterone

When a trans person begins taking testosterone , changes include both a reduction in assigned female sexual characteristics and an increase in assigned male sexual characteristics.

Bodily changes can include:

- Beard and mustache growth

- Deepening of the voice

- Enlargement of the clitoris

- Increased growth of body hair

- Increased muscle mass and strength

- Increase in the number of red blood cells

- Redistribution of fat from the breasts, hips, and thighs to the abdominal area

- Development of acne, similar to male puberty

- Baldness or localized hair loss, especially at the temples and crown of the head

- Atrophy of the uterus and ovaries, resulting in an inability to have children

Behavioral changes include:

- Aggression

- Increased sex drive

Effects of Estrogen

When a trans person begins taking estrogen , changes include both a reduction in assigned male sexual characteristics and an increase in assigned female characteristics.

Changes to the body can include:

- Breast development

- Loss of erection

- Shrinkage of testicles

- Decreased acne

- Decreased facial and body hair

- Decreased muscle mass and strength

- Softer and smoother skin

- Slowing of balding

- Redistribution of fat from abdomen to the hips, thighs, and buttocks

- Decreased sex drive

- Mood swings

When Are the Hormonal Therapy Effects Noticed?

The feminizing effects of estrogen and the masculinizing effects of testosterone may appear after the first couple of doses, although it may be several years before a person is satisfied with their transition. This is especially true for breast development.

Timeline of Surgical Process

Surgery is delayed until at least one year after the start of hormone therapy and at least two years after a mental health evaluation. Once the surgical procedures begin, the amount of time until completion is variable depending on the number of procedures desired, recovery time, and more.

Transfeminine Surgeries

Transfeminine is an umbrella term inclusive of trans women and non-binary trans people who were assigned male at birth.

Most often, surgeries involved in gender affirmation surgery are broken down into those that occur above the belt (top surgery) and those below the belt (bottom surgery). Not everyone undergoes all of these surgeries, but procedures that may be considered for transfeminine individuals are listed below.

Top surgery includes:

- Breast augmentation

- Facial feminization

- Nose surgery: Rhinoplasty may be done to narrow the nose and refine the tip.

- Eyebrows: A brow lift may be done to feminize the curvature and position of the eyebrows.

- Jaw surgery: The jaw bone may be shaved down.

- Chin reduction: Chin reduction may be performed to soften the chin's angles.

- Cheekbones: Cheekbones may be enhanced, often via collagen injections as well as other plastic surgery techniques.

- Lips: A lip lift may be done.

- Alteration to hairline

- Male pattern hair removal

- Reduction of Adam’s apple

- Voice change surgery

Bottom surgery includes:

- Removal of the penis (penectomy) and scrotum (orchiectomy)

- Creation of a vagina and labia

Transmasculine Surgeries

Transmasculine is an umbrella term inclusive of trans men and non-binary trans people who were assigned female at birth.

Surgery for this group involves top surgery and bottom surgery as well.

Top surgery includes :

- Subcutaneous mastectomy/breast reduction surgery.

- Removal of the uterus and ovaries

- Creation of a penis and scrotum either through metoidioplasty and/or phalloplasty

Complications and Side Effects

Surgery is not without potential risks and complications. Estrogen therapy has been associated with an elevated risk of blood clots ( deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary emboli ) for transfeminine people. There is also the potential of increased risk of breast cancer (even without hormones, breast cancer may develop).

Testosterone use in transmasculine people has been associated with an increase in blood pressure, insulin resistance, and lipid abnormalities, though it's not certain exactly what role these changes play in the development of heart disease.

With surgery, there are surgical risks such as bleeding and infection, as well as side effects of anesthesia . Those who are considering these treatments should have a careful discussion with their doctor about potential risks related to hormone therapy as well as the surgeries.

Cost of Gender Confirmation Surgery

Surgery can be prohibitively expensive for many transgender individuals. Costs including counseling, hormones, electrolysis, and operations can amount to well over $100,000. Transfeminine procedures tend to be more expensive than transmasculine ones. Health insurance sometimes covers a portion of the expenses.

Quality of Life After Surgery

Quality of life appears to improve after gender-affirming surgery for all trans people who medically transition. One 2017 study found that surgical satisfaction ranged from 94% to 100%.

Since there are many steps and sometimes uncomfortable surgeries involved, this number supports the benefits of surgery for those who feel it is their best choice.

A Word From Verywell

Gender affirmation surgery is a lengthy process that begins with counseling and a mental health evaluation to determine if a person can be diagnosed with gender dysphoria.

After this is complete, hormonal treatment is begun with testosterone for transmasculine individuals and estrogen for transfeminine people. Some of the physical and behavioral changes associated with hormonal treatment are listed above.

After hormone therapy has been continued for at least one year, a number of surgical procedures may be considered. These are broken down into "top" procedures and "bottom" procedures.

Surgery is costly, but precise estimates are difficult due to many variables. Finding a surgeon who focuses solely on gender confirmation surgery and has performed many of these procedures is a plus. Speaking to a surgeon's past patients can be a helpful way to gain insight on the physician's practices as well.

For those who follow through with these preparation steps, hormone treatment, and surgeries, studies show quality of life appears to improve. Many people who undergo these procedures express satisfaction with their results.

Bizic MR, Jeftovic M, Pusica S, et al. Gender dysphoria: Bioethical aspects of medical treatment . Biomed Res Int . 2018;2018:9652305. doi:10.1155/2018/9652305

American Psychiatric Association. What is gender dysphoria? . 2016.

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people . 2012.

Tomlins L. Prescribing for transgender patients . Aust Prescr . 2019;42(1): 10–13. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2019.003

T'sjoen G, Arcelus J, Gooren L, Klink DT, Tangpricha V. Endocrinology of transgender medicine . Endocr Rev . 2019;40(1):97-117. doi:10.1210/er.2018-00011

Unger CA. Hormone therapy for transgender patients . Transl Androl Urol . 2016;5(6):877-884. doi:10.21037/tau.2016.09.04

Seal LJ. A review of the physical and metabolic effects of cross-sex hormonal therapy in the treatment of gender dysphoria . Ann Clin Biochem . 2016;53(Pt 1):10-20. doi:10.1177/0004563215587763

Schechter LS. Gender confirmation surgery: An update for the primary care provider . Transgend Health . 2016;1(1):32-40. doi:10.1089/trgh.2015.0006

Altman K. Facial feminization surgery: current state of the art . Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg . 2012;41(8):885-94. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2012.04.024

Therattil PJ, Hazim NY, Cohen WA, Keith JD. Esthetic reduction of the thyroid cartilage: A systematic review of chondrolaryngoplasty . JPRAS Open. 2019;22:27-32. doi:10.1016/j.jpra.2019.07.002

Top H, Balta S. Transsexual mastectomy: Selection of appropriate technique according to breast characteristics . Balkan Med J . 2017;34(2):147-155. doi:10.4274/balkanmedj.2016.0093

Chan W, Drummond A, Kelly M. Deep vein thrombosis in a transgender woman . CMAJ . 2017;189(13):E502-E504. doi:10.1503/cmaj.160408

Streed CG, Harfouch O, Marvel F, Blumenthal RS, Martin SS, Mukherjee M. Cardiovascular disease among transgender adults receiving hormone therapy: A narrative review . Ann Intern Med . 2017;167(4):256-267. doi:10.7326/M17-0577

Hashemi L, Weinreb J, Weimer AK, Weiss RL. Transgender care in the primary care setting: A review of guidelines and literature . Fed Pract . 2018;35(7):30-37.

Van de grift TC, Elaut E, Cerwenka SC, Cohen-kettenis PT, Kreukels BPC. Surgical satisfaction, quality of life, and their association after gender-affirming aurgery: A follow-up atudy . J Sex Marital Ther . 2018;44(2):138-148. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2017.1326190

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Gender confirmation surgeries .

American Psychological Association. Transgender people, gender identity, and gender expression .

Colebunders B, Brondeel S, D'Arpa S, Hoebeke P, Monstrey S. An update on the surgical treatment for transgender patients . Sex Med Rev . 2017 Jan;5(1):103-109. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2016.08.001

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

Error bars represent 95% CIs. GAS indicates gender-affirming surgery.

Percentages are based on the number of procedures divided by number of patients; thus, as some patients underwent multiple procedures the total may be greater than 100%. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

eTable. ICD-10 and CPT Codes of Gender-Affirming Surgery

eFigure. Percentage of Patients With Codes for Gender Identity Disorder Who Underwent GAS

Data Sharing Statement

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Wright JD , Chen L , Suzuki Y , Matsuo K , Hershman DL. National Estimates of Gender-Affirming Surgery in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(8):e2330348. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.30348

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

National Estimates of Gender-Affirming Surgery in the US

- 1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, New York

- 2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles

Question What are the temporal trends in gender-affirming surgery (GAS) in the US?

Findings In this cohort study of 48 019 patients, GAS increased significantly, nearly tripling from 2016 to 2019. Breast and chest surgery was the most common class of procedures performed overall; genital reconstructive procedures were more common among older individuals.

Meaning These findings suggest that there will be a greater need for clinicians knowledgeable in the care of transgender individuals with the requisite expertise to perform gender-affirming procedures.

Importance While changes in federal and state laws mandating coverage of gender-affirming surgery (GAS) may have led to an increase in the number of annual cases, comprehensive data describing trends in both inpatient and outpatient procedures are limited.

Objective To examine trends in inpatient and outpatient GAS procedures in the US and to explore the temporal trends in the types of GAS performed across age groups.

Design, Setting, and Participants This cohort study includes data from 2016 to 2020 in the Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample and the National Inpatient Sample. Patients with diagnosis codes for gender identity disorder, transsexualism, or a personal history of sex reassignment were identified, and the performance of GAS, including breast and chest procedures, genital reconstructive procedures, and other facial and cosmetic surgical procedures, were identified.

Main Outcome Measures Weighted estimates of the annual number of inpatient and outpatient procedures performed and the distribution of each class of procedure overall and by age were analyzed.

Results A total of 48 019 patients who underwent GAS were identified, including 25 099 (52.3%) who were aged 19 to 30 years. The most common procedures were breast and chest procedures, which occurred in 27 187 patients (56.6%), followed by genital reconstruction (16 872 [35.1%]) and other facial and cosmetic procedures (6669 [13.9%]). The absolute number of GAS procedures rose from 4552 in 2016 to a peak of 13 011 in 2019 and then declined slightly to 12 818 in 2020. Overall, 25 099 patients (52.3%) were aged 19 to 30 years, 10 476 (21.8%) were aged 31 to 40, and 3678 (7.7%) were aged12 to 18 years. When stratified by the type of procedure performed, breast and chest procedures made up a greater percentage of the surgical interventions in younger patients, while genital surgical procedures were greater in older patients.

Conclusions and Relevance Performance of GAS has increased substantially in the US. Breast and chest surgery was the most common group of procedures performed. The number of genital surgical procedures performed increased with increasing age.

Gender dysphoria is characterized as an incongruence between an individual’s experienced or expressed gender and the gender that was assigned at birth. 1 Transgender individuals may pursue multiple treatments, including behavioral therapy, hormonal therapy, and gender-affirming surgery (GAS). 2 GAS encompasses a variety of procedures that align an individual patient’s gender identity with their physical appearance. 2 - 4

While numerous surgical interventions can be considered GAS, the procedures have been broadly classified as breast and chest surgical procedures, facial and cosmetic interventions, and genital reconstructive surgery. 2 , 4 Prior studies 2 - 7 have shown that GAS is associated with improved quality of life, high rates of satisfaction, and a reduction in gender dysphoria. Furthermore, some studies have reported that GAS is associated with decreased depression and anxiety. 8 Lastly, the procedures appear to be associated with acceptable morbidity and reasonable rates of perioperative complications. 2 , 4

Given the benefits of GAS, the performance of GAS in the US has increased over time. 9 The increase in GAS is likely due in part to federal and state laws requiring coverage of transition-related care, although actual insurance coverage of specific procedures is variable. 10 , 11 While prior work has shown that the use of inpatient GAS has increased, national estimates of inpatient and outpatient GAS are lacking. 9 This is important as many GAS procedures occur in ambulatory settings. We performed a population-based analysis to examine trends in GAS in the US and explored the temporal trends in the types of GAS performed across age groups.

To capture both inpatient and outpatient surgical procedures, we used data from the Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample (NASS) and the National Inpatient Sample (NIS). NASS is an ambulatory surgery database and captures major ambulatory surgical procedures at nearly 2800 hospital-owned facilities from up to 35 states, approximating a 63% to 67% stratified sample of hospital-owned facilities. NIS comprehensively captures approximately 20% of inpatient hospital encounters from all community hospitals across 48 states participating in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), covering more than 97% of the US population. Both NIS and NASS contain weights that can be used to produce US population estimates. 12 , 13 Informed consent was waived because data sources contain deidentified data, and the study was deemed exempt by the Columbia University institutional review board. This cohort study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology ( STROBE ) reporting guideline.

We selected patients of all ages with an International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision ( ICD-10 ) diagnosis codes for gender identity disorder or transsexualism ( ICD-10 F64) or a personal history of sex reassignment ( ICD-10 Z87.890) from 2016 to 2020 (eTable in Supplement 1 ). We first examined all hospital (NIS) and ambulatory surgical (NASS) encounters for patients with these codes and then analyzed encounters for GAS within this cohort. GAS was identified using ICD-10 procedure codes and Common Procedural Terminology codes and classified as breast and chest procedures, genital reconstructive procedures, and other facial and cosmetic surgical procedures. 2 , 4 Breast and chest surgical procedures encompassed breast reconstruction, mammoplasty and mastopexy, or nipple reconstruction. Genital reconstructive procedures included any surgical intervention of the male or female genital tract. Other facial and cosmetic procedures included cosmetic facial procedures and other cosmetic procedures including hair removal or transplantation, liposuction, and collagen injections (eTable in Supplement 1 ). Patients might have undergone procedures from multiple different surgical groups. We measured the total number of procedures and the distribution of procedures within each procedural group.

Within the data sets, sex was based on patient self-report. The sex of patients in NIS who underwent inpatient surgery was classified as either male, female, missing, or inconsistent. The inconsistent classification denoted patients who underwent a procedure that was not consistent with the sex recorded on their medical record. Similar to prior analyses, patients in NIS with a sex variable not compatible with the procedure performed were classified as having undergone genital reconstructive surgery (GAS not otherwise specified). 9

Clinical variables in the analysis included patient clinical and demographic factors and hospital characteristics. Demographic characteristics included age at the time of surgery (12 to 18 years, 19 to 30 years, 31 to 40 years, 41 to 50 years, 51 to 60 years, 61 to 70 years, and older than 70 years), year of the procedure (2016-2020), and primary insurance coverage (private, Medicare, Medicaid, self-pay, and other). Race and ethnicity were only reported in NIS and were classified as White, Black, Hispanic and other. Race and ethnicity were considered in this study because prior studies have shown an association between race and GAS. The income status captured national quartiles of median household income based of a patient’s zip code and was recorded as less than 25% (low), 26% to 50% (medium-low), 51% to 75% (medium-high), and 76% or more (high). The Elixhauser Comorbidity Index was estimated for each patient based on the codes for common medical comorbidities and weighted for a final score. 14 Patients were classified as 0, 1, 2, or 3 or more. We separately reported coding for HIV and AIDS; substance abuse, including alcohol and drug abuse; and recorded mental health diagnoses, including depression and psychoses. Hospital characteristics included a composite of teaching status and location (rural, urban teaching, and urban nonteaching) and hospital region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West). Hospital bed sizes were classified as small, medium, and large. The cutoffs were less than 100 (small), 100 to 299 (medium), and 300 or more (large) short-term acute care beds of the facilities from NASS and were varied based on region, urban-rural designation, and teaching status of the hospital from NIS. 8 Patients with missing data were classified as the unknown group and were included in the analysis.

National estimates of the number of GAS procedures among all hospital encounters for patients with gender identity disorder were derived using discharge or encounter weight provided by the databases. 15 The clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients undergoing GAS were reported descriptively. The number of encounters for gender identity disorder, the percentage of GAS procedures among those encounters, and the absolute number of each procedure performed over time were estimated. The difference by age group was examined and tested using Rao-Scott χ 2 test. All hypothesis tests were 2-sided, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

A total of 48 019 patients who underwent GAS were identified ( Table 1 ). Overall, 25 099 patients (52.3%) were aged 19 to 30 years, 10 476 (21.8%) were aged 31 to 40, and 3678 (7.7%) were aged 12 to 18 years. Private insurance coverage was most common in 29 064 patients (60.5%), while 12 127 (25.3%) were Medicaid recipients. Depression was reported in 7192 patients (15.0%). Most patients (42 467 [88.4%]) were treated at urban, teaching hospitals, and there was a disproportionate number of patients in the West (22 037 [45.9%]) and Northeast (12 396 [25.8%]). Within the cohort, 31 668 patients (65.9%) underwent 1 procedure while 13 415 (27.9%) underwent 2 procedures, and the remainder underwent multiple procedures concurrently ( Table 1 ).

The overall number of health system encounters for gender identity disorder rose from 13 855 in 2016 to 38 470 in 2020. Among encounters with a billing code for gender identity disorder, there was a consistent rise in the percentage that were for GAS from 4552 (32.9%) in 2016 to 13 011 (37.1%) in 2019, followed by a decline to 12 818 (33.3%) in 2020 ( Figure 1 and eFigure in Supplement 1 ). Among patients undergoing ambulatory surgical procedures, 37 394 (80.3%) of the surgical procedures included gender-affirming surgical procedures. For those with hospital admissions with gender identity disorder, 10 625 (11.8%) of admissions were for GAS.

Breast and chest procedures were most common and were performed for 27 187 patients (56.6%). Genital reconstruction was performed for 16 872 patients (35.1%), and other facial and cosmetic procedures for 6669 patients (13.9%) ( Table 2 ). The most common individual procedure was breast reconstruction in 21 244 (44.2%), while the most common genital reconstructive procedure was hysterectomy (4489 [9.3%]), followed by orchiectomy (3425 [7.1%]), and vaginoplasty (3381 [7.0%]). Among patients who underwent other facial and cosmetic procedures, liposuction (2945 [6.1%]) was most common, followed by rhinoplasty (2446 [5.1%]) and facial feminizing surgery and chin augmentation (1874 [3.9%]).

The absolute number of GAS procedures rose from 4552 in 2016 to a peak of 13 011 in 2019 and then declined slightly to 12 818 in 2020 ( Figure 1 ). Similar trends were noted for breast and chest surgical procedures as well as genital surgery, while the rate of other facial and cosmetic procedures increased consistently from 2016 to 2020. The distribution of the individual procedures performed in each class were largely similar across the years of analysis ( Table 3 ).

When stratified by age, patients 19 to 30 years had the greatest number of procedures, 25 099 ( Figure 2 ). There were 10 476 procedures performed in those aged 31 to 40 years and 4359 in those aged 41 to 50 years. Among patients younger than 19 years, 3678 GAS procedures were performed. GAS was less common in those cohorts older than 50 years. Overall, the greatest number of breast and chest surgical procedures, genital surgical procedures, and facial and other cosmetic surgical procedures were performed in patients aged 19 to 30 years.

When stratified by the type of procedure performed, breast and chest procedures made up the greatest percentage of the surgical interventions in younger patients while genital surgical procedures were greater in older patients ( Figure 2 ). Additionally, 3215 patients (87.4%) aged 12 to 18 years underwent GAS and had breast or chest procedures. This decreased to 16 067 patients (64.0%) in those aged 19 to 30 years, 4918 (46.9%) in those aged 31 to 40 years, and 1650 (37.9%) in patients aged 41 to 50 years ( P < .001). In contrast, 405 patients (11.0%) aged 12 to 18 years underwent genital surgery. The percentage of patients who underwent genital surgery rose sequentially to 4423 (42.2%) in those aged 31 to 40 years, 1546 (52.3%) in those aged 51 to 60 years, and 742 (58.4%) in those aged 61 to 70 years ( P < .001). The percentage of patients who underwent facial and other cosmetic surgical procedures rose with age from 9.5% in those aged 12 to 18 years to 20.6% in those aged 51 to 60 years, then gradually declined ( P < .001). Figure 2 displays the absolute number of procedure classes performed by year stratified by age. The greatest magnitude of the decline in 2020 was in younger patients and for breast and chest procedures.

These findings suggest that the number of GAS procedures performed in the US has increased dramatically, nearly tripling from 2016 to 2019. Breast and chest surgery is the most common class of procedure performed while patients are most likely to undergo surgery between the ages of 19 and 30 years. The number of genital surgical procedures performed increased with increasing age.

Consistent with prior studies, we identified a remarkable increase in the number of GAS procedures performed over time. 9 , 16 A prior study examining national estimates of inpatient GAS procedures noted that the absolute number of procedures performed nearly doubled between 2000 to 2005 and from 2006 to 2011. In our analysis, the number of GAS procedures nearly tripled from 2016 to 2020. 9 , 17 Not unexpectedly, a large number of the procedures we captured were performed in the ambulatory setting, highlighting the need to capture both inpatient and outpatient procedures when analyzing data on trends. Like many prior studies, we noted a decrease in the number of procedures performed in 2020, likely reflective of the COVID-19 pandemic. 18 However, the decline in the number of procedures performed between 2019 and 2020 was relatively modest, particularly as these procedures are largely elective.

Analysis of procedure-specific trends by age revealed a number of important findings. First, GAS procedures were most common in patients aged 19 to 30 years. This is in line with prior work that demonstrated that most patients first experience gender dysphoria at a young age, with approximately three-quarters of patients reporting gender dysphoria by age 7 years. These patients subsequently lived for a mean of 23 years for transgender men and 27 years for transgender women before beginning gender transition treatments. 19 Our findings were also notable that GAS procedures were relatively uncommon in patients aged 18 years or younger. In our cohort, fewer than 1200 patients in this age group underwent GAS, even in the highest volume years. GAS in adolescents has been the focus of intense debate and led to legislative initiatives to limit access to these procedures in adolescents in several states. 20 , 21

Second, there was a marked difference in the distribution of procedures in the different age groups. Breast and chest procedures were more common in younger patients, while genital surgery was more frequent in older individuals. In our cohort of individuals aged 19 to 30 years, breast and chest procedures were twice as common as genital procedures. Genital surgery gradually increased with advancing age, and these procedures became the most common in patients older than 40 years. A prior study of patients with commercial insurance who underwent GAS noted that the mean age for mastectomy was 28 years, significantly lower than for hysterectomy at age 31 years, vaginoplasty at age 40 years, and orchiectomy at age 37 years. 16 These trends likely reflect the increased complexity of genital surgery compared with breast and chest surgery as well as the definitive nature of removal of the reproductive organs.

This study has limitations. First, there may be under-capture of both transgender individuals and GAS procedures. In both data sets analyzed, gender is based on self-report. NIS specifically makes notation of procedures that are considered inconsistent with a patient’s reported gender (eg, a male patient who underwent oophorectomy). Similar to prior work, we assumed that patients with a code for gender identity disorder or transsexualism along with a surgical procedure classified as inconsistent underwent GAS. 9 Second, we captured procedures commonly reported as GAS procedures; however, it is possible that some of these procedures were performed for other underlying indications or diseases rather than solely for gender affirmation. Third, our trends showed a significant increase in procedures through 2019, with a decline in 2020. The decline in services in 2020 is likely related to COVID-19 service alterations. Additionally, while we comprehensively captured inpatient and ambulatory surgical procedures in large, nationwide data sets, undoubtedly, a small number of procedures were performed in other settings; thus, our estimates may underrepresent the actual number of procedures performed each year in the US.

These data have important implications in providing an understanding of the use of services that can help inform care for transgender populations. The rapid rise in the performance of GAS suggests that there will be a greater need for clinicians knowledgeable in the care of transgender individuals and with the requisite expertise to perform GAS procedures. However, numerous reports have described the political considerations and challenges in the delivery of transgender care. 22 Despite many medical societies recognizing the necessity of gender-affirming care, several states have enacted legislation or policies that restrict gender-affirming care and services, particularly in adolescence. 20 , 21 These regulations are barriers for patients who seek gender-affirming care and provide legal and ethical challenges for clinicians. As the use of GAS increases, delivering equitable gender-affirming care in this complex landscape will remain a public health challenge.

Accepted for Publication: July 15, 2023.

Published: August 23, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.30348

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License . © 2023 Wright JD et al. JAMA Network Open .

Corresponding Author: Jason D. Wright, MD, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, 161 Fort Washington Ave, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10032 ( [email protected] ).

Author Contributions: Dr Wright had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Wright, Chen.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Wright.

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Wright, Chen.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Wright, Suzuki.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Wright reported receiving grants from Merck and personal fees from UpToDate outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 2 .

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Elective surgeries were postponed during the coronavirus outbreak. But my gender-affirming surgery isn't optional — it's lifesaving.

- I'm a reporter for Business Insider who is male and nonbinary. I was worried that my upcoming gender-affirming surgery will be canceled because of the coronavirus outbreak.

- In March, Governor Cuomo called on health systems to stop performing elective procedures in New York state because hospitals are overwhelmed with patients.

- My gender-affirming surgery is considered "elective." However, if my surgery is postponed, it will have a severe impact on my mental and physical health.

- Visit Business Insider's homepage for more stories .

Sign up here to receive updates on all things Gender at Work.

[EDITOR'S NOTE: When this story was originally published in March, elective surgeries had been canceled. As part of New York's statewide reopening plan, Gov. Andrew Cuomo has allowed elective surgeries to resume in New York City, according to New York Post ]

I took the subway two weeks ago to one of the few transgender healthcare centers in New York City to retrieve my last psychological letter for gender-affirming surgery.

Yet, when I arrived at the center in Manhattan, the psychiatrist wasn't there. I was told she was adhering to the state's mandates and began social distancing.

Outside the office, it was a ghost town.

The streets that are normally filled with halal trucks and people selling knockoff purses were nearly empty. And then there was me: a guy who left his house and essentially risked coming in contact with coronavirus for no reason.

This was one of the last letters I need for Medicaid to begin approving my gender-affirming procedure — more simply known as bottom surgery. Without these letters, my health insurance will not deem the surgery "medically necessary." And as a result, I will not be able to afford it.

This happened soon after the US Surgeon General requested that health systems consider pausing elective surgeries . Last week, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo ordered that medical centers pause elective surgeries . What's more, a staff member at the health center warned me that because of the outbreak my surgery could be postponed.

I am not alone: Transgender and nonbinary people face many barriers when it comes to finding access to gender-affirming healthcare. In 2015, the US Transgender Survey found that one-third of trans and nonbinary people face discrimination at the doctor's office. Their findings also show that 33% of trans people postponed medical care because of the cost.

On the other hand, research shows gender confirmation surgeries improve the overall mental health and wellbeing of trans and nonbinary people .

Related stories

For many people, when they hear "elective surgery" they assume cosmetic surgeries. I've waited nearly a year for SRS and now the growing coronavirus pandemic is threatening to take it away.

Trans and nonbinary people face barriers in healthcare

I am scheduled to have bottom surgery or metoidioplasty in July 2020, but because of the delay in elective procedures, it's likely that my pre-op appointment and surgery will be rescheduled. Before then I've had to go through a number of psychological evaluations to be deemed "sane" for the procedure.

According to national trans health guidelines from WPATH (The World Professional Association of Transgender Health), trans and nonbinary patients who want bottom surgery must have gender dysphoria, have their mental illnesses under control, receive hormone replacement therapy for a year, and live consistently as their gender (whether male, female, or nonbinary). Also, you need letters from a doctor, psychiatrist, and counselor that prove this procedure is medically necessary.

Not only do we face strict requirements for treatment, but this system is backlogged with patients. Last September, I called Mount Sinai's Transgender Health Clinic, was put on a waitlist, and then scheduled for my first appointment in November.

At the appointment, I didn't make the weight requirement. All transgender and nonbinary patients are required to have a BMI of 33. At the time, my BMI was closer to 34. Business Insider has previously reported that BMI is an outdated system that doesn't measure body fat. According to health experts, physicians can yield a more accurate result of your health by measuring your waist circumference .

Yet, the facility did not allow me to schedule surgery until I lost the weight. I lost 10 pounds through a crash diet. Hours before I graduated from the Craig Newmark School of Journalism, I weighed in at Mount Sinai's Transgender Health Clinic. Then, I had my first consultation with the doctor in January.

I also faced bias from mental health counselors who could write a letter. The first therapist I went to for a letter for bottom surgery told me she didn't feel comfortable advocating for me to get surgery. So, I had to look elsewhere. And my former psychiatrist who is covered under Medicaid calls me "Mrs." at every appointment, despite knowing I am male. Therefore, receiving a letter from him was not an option. Now, social distancing has delayed me even further. To this day, I have not received a letter.

The surgery isn't elective — it's lifesaving

In August of 2018, a doctor officially diagnosed me with gender dysphoria, the debilitating distress I feel because of a disconnect between my brain and how the world perceives my body. Since then, I've received treatment through hormone replacement therapy or injecting my stomach every week with testosterone. This has relieved a lot of my symptoms, such as depression and anxiety.

Much of my dysphoria comes from not feeling socially included in male spaces. On a day-to-day basis, this means finding another bathroom at work because there are no open stalls. At a former internship and graduate school, this meant people intentionally calling me by my dead pronouns and grouping me in with "women" or "ladies."

It's only recently that I've started to be read as male in public (for example, grocery store cashiers calling me sir, people on the street calling me brother and guy). While this is a relief, it's also scary. I avoid public gyms because I fear the potential violence and stigma I'll face in the men's locker. Receiving this surgery as soon as possible will allow me to avoid potential violence and live my life safely.

Now, I am waiting for a call from my surgeon's office on whether or not my surgery and pre-op appointment will be rescheduled or canceled. Bottom surgery is one of the final steps I'm taking in my gender transition. Most of my legal documents are male. My mail is addressed to "Mr. Tatyana Bellamy-Walker" and I have an "M" on my driver's license, social security records, and birth certificate.

And although transgender people are banned from the US military, I managed to be registered into the US Selective Service System, a military draft system for all males under the age of 26.

Yet, somehow, the pandemic is becoming my latest obstacle to participating in public life.

This story was originally published on March 30, 2020.

Watch: What it's like to be a 'deathcare' worker collecting bodies during the coronavirus pandemic

- Main content

- For Journalists

- News Releases

- Latest Releases

- News Release

Age restriction lifted for gender-affirming surgery in new international guidelines

'Will result in the need for parental consent before doctors would likely perform surgeries'

Media Information

- Release Date: September 16, 2022

Media Contacts

Kristin Samuelson

- (847) 491-4888

- Email Kristin

- Expert can speak to transgender peoples’ right to bodily autonomy, how guidelines affect insurance coverage, how the U.S. gender regulations compare to other countries, more

CHICAGO --- The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) today today announced its updated Standards of Care and Ethical Guidelines for health professionals. Among the updates is a new suggestion to lift the age restriction for youth seeking gender-affirming surgical treatment, in comparison to previous suggestion of surgery at 17 or older.

Alithia Zamantakis (she/her), a member of the Institute of Sexual & Gender Minority Health at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, is available to speak to media about the new guidelines. Contact Kristin Samuelson at [email protected] to schedule an interview.

“Lifting the age restriction will greatly increase access to care for transgender adolescents, but will also result in the need for parental consent for surgeries before doctors would likely perform them,” said Zamantakis, a postdoctoral fellow at Northwestern, who has researched trans youth and resilience. “Additionally, changes in age restriction are not likely to change much in practice in states like Alabama, Arkansas, Texas and Arizona, where gender-affirming care for youth is currently banned.”

Zamantakis also can speak about transgender peoples’ right to bodily autonomy, how guidelines affect insurance coverage and how U.S. gender regulations compare to other countries.

Guidelines are thorough but WPATH ‘still has work to do’

“The systematic reviews conducted as part of the development of the standards of care are fantastic syntheses of the literature on gender-affirming care that should inform doctors' work,” Zamantakis said. “They are used by numerous providers and insurance companies to determine who gets access to care and who does not.

“However, WPATH still has work to do to ensure its standards of care are representative of the needs and experiences of all non-cisgender people and that the standards of care are used to ensure that individuals receive adequate care rather than to gatekeep who gets access to care. WPATH largely has been run by white and/or cisgender individuals. It has only had three transgender presidents thus far, with Marci Bower soon to be the second trans woman president.

“Future iterations of the standards of care must include more stakeholders per committee, greater representation of transgender experts and stakeholders of color, and greater representation of experts and stakeholders outside the U.S.”

Transgender individuals’ right to bodily autonomy

“WPATH does not recommend prior hormone replacement therapy or ‘presenting’ as one's gender for a certain period of time for surgery for nonbinary people, yet it still does for transgender women and men,” Zamantakis said. “The reality is that neither should be requirements for accessing care for people of any gender.

“The recommendation of requiring documentation of persistent gender incongruence is meant to prevent regret. However, it's important to ask who ultimately has the authority to determine whether individuals have the right to make decisions about their bodily autonomy that they may or may not regret? Cisgender women undergo breast augmentation regularly, which is not an entirely reversible procedure, yet they are not required to have proof of documented incongruence. It is assumed that if they regret the surgery, they will learn to cope with the regret or will have an additional surgery. Transgender individuals also deserve the right to bodily autonomy and ultimately to regret the decisions they make if they later do not align with how they experience themselves.”

- Reconstructive Procedures

Gender Confirmation Surgeries Transgender-Specific Facial, Top and Bottom Procedures

What surgical options are available to transgender and gender non-conforming patients? Gender confirmation surgeries, also known as gender affirmation surgeries, are performed by a multispecialty team that typically includes board-certified plastic surgeons. The goal is to give transgender individuals the physical appearance and functional abilities of the gender they know themselves to be. Listed below are many of the available procedures for transwomen (MTF) and transmen (FTM) to aid in their journey.

Facial Feminization Surgery

Transfeminine top surgery, transfeminine bottom surgery, facial masculinization surgery, transmasculine top surgery, transmasculine bottom surgery, on the blog.

Facial feminization surgery is a combination of procedures designed to soften the facial features and feminize the face. There are many procedures that are available to feminize the face.

- Facial feminization surgery improves gender dysphoria in trans women Josef Hadeed, MD, FACS

- The impact of COVID-19 on gender dysphoria patients Cristiane Ueno, MD

On The Vlog

Facial feminization surgery is always tailored to the individual, but as ASPS member Justine Lee, MD, PhD, explains there are general characteristics such as hairline, brow bones, cheeks and jawline that many patients note and plastic surgeons plan for.

- Gender Affirmation Top Surgery with Dr. Julie Hansen

Find Your Surgeon

Patient care center, before & after photos.

Video Gallery

3d animations, patient safety.

It’s time to stop describing lifesaving health care as “elective”

Labels like “nonessential” are getting in the way of urgent treatments and surgeries. There’s a better way.

by Andréa Becker

Emily Lipstein lived with 10 years of debilitating, unexplained chronic pain before she finally received a diagnosis — endometriosis — and was scheduled for excision surgery . But when the pandemic hit, her surgery was deemed nonessential and indefinitely postponed.

“It felt like everything I’d been looking forward to with my health just evaporated into thin air,” Lipstein told Vox. In the months she waited for a rescheduled surgery, she had to pay for an extra MRI scan and experienced mental health issues, for which she was prescribed antidepressants.

Around the start of the Covid-19 pandemic in March 2020, the US federal government told health providers to postpone elective surgeries and “nonessential” medical procedures. These cancellations and delays, which affected everything from hip replacements to cataract surgeries to colonoscopies, were meant to conserve health care resources and minimize exposure to Covid-19. More than 100 hospitals have again resorted to this strategy in recent months because of the delta surge .

For the thousands of people across the country who were and are awaiting important medical care, these indefinite cancellations have been devastating. Experts and patients told Vox that the perceived importance of a given procedure is largely up to interpretation — as well as the whims of local politics.

“The term ‘elective care’ can be misleading,” said Joseph Sakran, a trauma surgeon at Johns Hopkins Hospital who performs both elective and emergency surgeries. Many people may assume that elective surgeries are unnecessary or cosmetic, but doctors use the word to describe pretty much any procedure that can be scheduled in advance . When officials hit pause on huge swaths of the medical system, some patients are forced to “prolong their suffering,” Sakran said.

The term “nonessential” often devalues care for women, LGBTQ people, and the chronically ill, said Virginia Kuulei Berndt, a medical sociologist and professor at Texas A&M University. “Some illnesses are prioritized less than others, and their corresponding treatments are deemed less urgent,” she said.

As a medical sociologist, I research how the binary system of “lifesaving” versus “elective” care is used and abused, and how these categories worsen social inequalities. The current system is supposed to help doctors triage, helping patients in dire need come to the front of the line. But labels have big consequences in health care: They can deem a condition worthy of medical treatment, drastically affect the support insurance companies will offer, and even stigmatize entire identities.

While we continue to hear calls to halt nonessential care, it’s a critical moment to ask: Who decides what counts as essential health care? And what happens when your care is deemed unnecessary? It’s time to move from a binary choice to a model with more tiers, which would capture quality of life and mental health and codify devalued forms of health care as nonnegotiable.

Labels like “nonessential” and “elective” can be inaccurate and misleading

Data shows that more than 90 percent of US surgeries are considered elective or nonessential. Collectively, they bring the nation’s health care system between $48 billion and $64 billion of revenue per year. This is why so many hospital systems struggled financially in the early days of the pandemic: While beds filled with Covid-19 patients, many profitable services ground to a halt.

Yet the definition of essential care has varied not only by health care provider, insurance company, and hospital system, but also by the state, city, or town that a person happens to live in. Some conditions are clearly emergencies, such as a rupturing appendix. But “nonessential” does not necessarily mean something purely cosmetic like a rhinoplasty or tummy tuck. During the pandemic, Sakran said, he has had to postpone surgeries to repair hernias that impede people from comfortably eating or walking.

The logistical difficulty of defining essential care has been “an ongoing challenge for insurance companies,” said Jesse Ehrenfeld, a physician and LGBTQ health advocate who chairs the American Medical Association board of trustees. It “leads to a lot of individual decision-making happening that is inconsistent.”

“The term ‘nonessential’ often devalues care for women, LGBTQ people, and the chronically ill”

Without a widely accepted definition, the focus tends to be on risk of immediate death, while other facets of health aren’t factored into the necessity equation. In some cases, providers, insurance companies, and government agencies have latitude to decide whether a procedure is essential based on cultural beliefs or political agendas.

Insurance companies also ask patients and providers to prove the necessity of a procedure or medication, using a controversial bureaucratic process called prior authorization . Designed as a cost-control tool, this approach adds 16 hours to the work week of the average US physician, according to a study conducted by the American Medical Association. The administrative hassle and wait times can lead to patients giving up on getting the care they need.

Existing categories are failing women, LGBTQ people, and the chronically ill

In the US, access to high-quality care already depends too much on a person’s social status and ability to pay — and when certain care can be deemed nonessential, these gaps in access grow wider.

Leigh Senderowicz, a health demographer at the University of Wisconsin Madison, describes the ambiguity around essential care as “a fissure” that allows groups “to pursue whatever existing agenda they have.” Abortion is one prominent example, said Senderowicz, whose team has researched reproductive autonomy during the pandemic .

While some groups have used the pandemic as a reason to restrict abortion, others pushed for increased access through telemedicine appointments for medication abortion . These groups used the same word to demand very different health policies.

I first grasped the problem with the words “elective” and “nonessential” during research interviews with over 100 hysterectomy patients. Hysterectomy, or the surgical removal of the uterus, is the most common gynecological surgery outside of pregnancy-related issues in the United States. While around 10 percent of hysterectomies are performed to treat cancer and may be classified as emergencies, the overwhelming majority are classified as elective procedures, whether they’re gender-affirming care for trans patients or aim to manage a chronic reproductive illness.

While hysterectomy doesn’t immediately prevent death in these cases, timely access to this surgery can have a vast impact on a patient’s quality of life, mental health, and ability to attend work or school. The reason these procedures are deemed elective is not that they aren’t urgently needed, but that the underlying condition will not immediately kill them. The words “elective” and “nonessential” create additional obstacles when insurance companies reject claims or a hospital blocks a physician from providing a hysterectomy.

- Americans are dying because no hospital will take them

Jordan, a Massachusetts resident who asked to be identified by a pseudonym to protect her privacy, has experienced debilitating chronic pain and bleeding since she was a teenager due to adenomyosis , an illness that impacts the lining of the uterus. Her adenomyosis led her to drop out of college and move in with her parents, and she spends most days managing her symptoms. After years of seeking diagnosis and relief, she found a physician who finally presented a viable solution: hysterectomy.

Then the hospital intervened, Jordan told me, on the grounds that it was an unnecessary sterilization procedure. “The hospital does not see it as medically necessary, despite my surgeon specifically telling them that it was for quality-of-life purposes,” she said. “No, it won’t kill me, it’s a benign disease, but I might kill myself because I have it. And still, they denied it.”

Her doctor even suggested she leave the state, Jordan said, despite its reputation for progressive policies and leading medical care, because hysterectomies are more commonly performed in other regions, such as the South. Many patients won’t have the money or means to travel between states.

Gender-affirming care for trans people is also “viewed by some as unnecessary or low-priority, [resulting] in inequities becoming even more pronounced,” said Jesse Ehrenfeld. For a population that’s already affected by a shortage of specialists and big gaps in research, the nonessential label is an additional obstacle to what Ehrenfeld and other public health experts view as lifesaving care.

Ash, an agender person in Pennsylvania who requested a pseudonym to protect their privacy, for years wanted a hysterectomy to affirm their gender, but said that many doctors deemed it an unnecessary procedure that wouldn’t be covered by insurance. A doctor who finally agreed to the surgery, they added, said it would be easier to get it approved if it was classified as treatment for endometriosis, rather than as part of trans health care.

“He told me, ‘Listen, we’re gonna fill out the paperwork to say ... that you probably have endometriosis,” Ash said, paraphrasing the doctor. “This is what we have to do for insurance.” Their insurance company seemed to classify their hysterectomy as elective or cosmetic, Ash said, and coverage for the procedure seemed to depend on finding a doctor who would misrepresent the reason for the surgery.

When the meaning of a procedure varies so drastically by location and physician, and leads patients and doctors to lie to insurance companies, we should consider overhauling the system.

A new system could classify medical care by its urgency, whether or not it’s an emergency

The current way of defining essential health care is failing many patients. While the current designation is either/or — based on whether a patient is immediately at risk of death — our actual experience of health has many shades and subtleties. Doctors and health officials need to consider the impact of medical care on a person’s quality of life, mental health, and ability to work, as well as the impact on families and communities.

The best alternative to the binary system is a tiered framework, which would group different types of care based on varying degrees of urgency. For example, health systems could adopt three tiers: emergency, intermediate urgency, and routine. In this model, emergencies would still describe risks of imminent death or severe harm — such as a heart attack — and routine cases would refer to primary care, preventative screenings, and genuinely cosmetic procedures.

It’s the middle tier that has the greatest potential to improve and even save lives. This tier includes acute cases that aren’t life-threatening but require attention within 24 hours, such as a broken bone or a wound that needs stitches. But the medical care I’ve described in this article, from trans health care to abortion, also has intermediate urgency: It may increase mortality risk, reduce quality of life, or negatively impact mental health.

While a condition like chronic pain might not pose immediate mortality risk, the daily toll can have detrimental impact on one’s mental health and ability to function across all areas of life and work. In the case of trans patients, there is substantial evidence that access to gender-affirming care, including access to hormone replacement therapy, can save lives by improving mental health and by reducing suicide rates . Research also shows that when people can’t access abortion, their financial, physical, and mental health suffer. These elements of health, in addition to immediate risk of death, are considered in a tiered system of urgency.

This additional category would make it harder for local officials to make sweeping decisions that postpone or cancel a wide range of needed care. A tiered model would work best with proper oversight by public health experts and clear guidance about each type of care, to prevent the devaluation of historically sidelined care as “low urgency” or “routine.”

Without such standardization, Ehrenfeld said, legislative bodies can restrict access to care and put physicians in a bind — making it difficult for them to “act in the best interest of their patients and follow the evidence-based guidelines.” Any system that fails to define what kind of care is nonnegotiable leaves open the possibility of discrimination against stigmatized patients.

The pandemic has laid bare many gaps in the American approach to public health. Some have widened in the past year and a half. But now that we’ve seen the massive impact of delayed and canceled care, we have a big opportunity to fix a longstanding problem. We should change the way we categorize and prioritize different types of health care, and move toward a more holistic understanding of health and well-being.

Kuulei Berndt aptly summarized the problem before us. It’s fixable, as long as we have the will to solve it. “Nonessential does not mean it doesn’t need to happen,” she said. “Elective does not mean superfluous.”

Andréa Becker is a medical sociologist, researcher, and writer. She is a PhD candidate at the CUNY Graduate Center in New York and teaches sociology of health at Lehman College.

Most Popular

Why are whole-body deodorants suddenly everywhere, if trump wins, what would hold him back, take a mental break with the newest vox crossword, what the death of iran’s president could mean for its future, the known unknowns about ozempic, explained, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Politics

Biden promised to defeat authoritarianism. Reality got in the way.

Blood, flames, and horror movies: The evocative imagery of King Charles’s portrait

Why the US built a pier to get aid into Gaza

The controversy over Gaza’s death toll, explained

Bridgerton’s third season is more diverse — and even shallower — than ever

The misleading, wasteful way we measure gas mileage, explained

The Republican Party's man inside the Supreme Court

Why Trump's running mate could be the most important VP pick of our time

Rent control for child care?

Introducing Vox’s next chapter

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Tests & Procedures

- Feminizing surgery

Feminizing surgery, also called gender-affirming surgery or gender-confirmation surgery, involves procedures that help better align the body with a person's gender identity. Feminizing surgery includes several options, such as top surgery to increase the size of the breasts. That procedure also is called breast augmentation. Bottom surgery can involve removal of the testicles, or removal of the testicles and penis and the creation of a vagina, labia and clitoris. Facial procedures or body-contouring procedures can be used as well.

Not everybody chooses to have feminizing surgery. These surgeries can be expensive, carry risks and complications, and involve follow-up medical care and procedures. Certain surgeries change fertility and sexual sensations. They also may change how you feel about your body.

Your health care team can talk with you about your options and help you weigh the risks and benefits.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Available Sexual Health Solutions at Mayo Clinic Store

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Why it's done

Many people seek feminizing surgery as a step in the process of treating discomfort or distress because their gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth. The medical term for this is gender dysphoria.

For some people, having feminizing surgery feels like a natural step. It's important to their sense of self. Others choose not to have surgery. All people relate to their bodies differently and should make individual choices that best suit their needs.

Feminizing surgery may include:

- Removal of the testicles alone. This is called orchiectomy.

- Removal of the penis, called penectomy.

- Removal of the testicles.

- Creation of a vagina, called vaginoplasty.

- Creation of a clitoris, called clitoroplasty.

- Creation of labia, called labioplasty.

- Breast surgery. Surgery to increase breast size is called top surgery or breast augmentation. It can be done through implants, the placement of tissue expanders under breast tissue, or the transplantation of fat from other parts of the body into the breast.

- Plastic surgery on the face. This is called facial feminization surgery. It involves plastic surgery techniques in which the jaw, chin, cheeks, forehead, nose, and areas surrounding the eyes, ears or lips are changed to create a more feminine appearance.

- Tummy tuck, called abdominoplasty.

- Buttock lift, called gluteal augmentation.

- Liposuction, a surgical procedure that uses a suction technique to remove fat from specific areas of the body.

- Voice feminizing therapy and surgery. These are techniques used to raise voice pitch.

- Tracheal shave. This surgery reduces the thyroid cartilage, also called the Adam's apple.

- Scalp hair transplant. This procedure removes hair follicles from the back and side of the head and transplants them to balding areas.

- Hair removal. A laser can be used to remove unwanted hair. Another option is electrolysis, a procedure that involves inserting a tiny needle into each hair follicle. The needle emits a pulse of electric current that damages and eventually destroys the follicle.

Your health care provider might advise against these surgeries if you have:

- Significant medical conditions that haven't been addressed.

- Behavioral health conditions that haven't been addressed.

- Any condition that limits your ability to give your informed consent.

Like any other type of major surgery, many types of feminizing surgery pose a risk of bleeding, infection and a reaction to anesthesia. Other complications might include:

- Delayed wound healing

- Fluid buildup beneath the skin, called seroma

- Bruising, also called hematoma

- Changes in skin sensation such as pain that doesn't go away, tingling, reduced sensation or numbness

- Damaged or dead body tissue — a condition known as tissue necrosis — such as in the vagina or labia

- A blood clot in a deep vein, called deep vein thrombosis, or a blood clot in the lung, called pulmonary embolism

- Development of an irregular connection between two body parts, called a fistula, such as between the bladder or bowel into the vagina

- Urinary problems, such as incontinence

- Pelvic floor problems

- Permanent scarring

- Loss of sexual pleasure or function

- Worsening of a behavioral health problem

Certain types of feminizing surgery may limit or end fertility. If you want to have biological children and you're having surgery that involves your reproductive organs, talk to your health care provider before surgery. You may be able to freeze sperm with a technique called sperm cryopreservation.

How you prepare

Before surgery, you meet with your surgeon. Work with a surgeon who is board certified and experienced in the procedures you want. Your surgeon talks with you about your options and the potential results. The surgeon also may provide information on details such as the type of anesthesia that will be used during surgery and the kind of follow-up care that you may need.

Follow your health care team's directions on preparing for your procedures. This may include guidelines on eating and drinking. You may need to make changes in the medicine you take and stop using nicotine, including vaping, smoking and chewing tobacco.

Because feminizing surgery might cause physical changes that cannot be reversed, you must give informed consent after thoroughly discussing:

- Risks and benefits

- Alternatives to surgery

- Expectations and goals

- Social and legal implications

- Potential complications

- Impact on sexual function and fertility

Evaluation for surgery

Before surgery, a health care provider evaluates your health to address any medical conditions that might prevent you from having surgery or that could affect the procedure. This evaluation may be done by a provider with expertise in transgender medicine. The evaluation might include:

- A review of your personal and family medical history

- A physical exam

- A review of your vaccinations

- Screening tests for some conditions and diseases

- Identification and management, if needed, of tobacco use, drug use, alcohol use disorder, HIV or other sexually transmitted infections

- Discussion about birth control, fertility and sexual function

You also may have a behavioral health evaluation by a health care provider with expertise in transgender health. That evaluation might assess:

- Gender identity

- Gender dysphoria

- Mental health concerns

- Sexual health concerns

- The impact of gender identity at work, at school, at home and in social settings

- The role of social transitioning and hormone therapy before surgery

- Risky behaviors, such as substance use or use of unapproved hormone therapy or supplements

- Support from family, friends and caregivers

- Your goals and expectations of treatment

- Care planning and follow-up after surgery

Other considerations

Health insurance coverage for feminizing surgery varies widely. Before you have surgery, check with your insurance provider to see what will be covered.

Before surgery, you might consider talking to others who have had feminizing surgery. If you don't know someone, ask your health care provider about support groups in your area or online resources you can trust. People who have gone through the process may be able to help you set your expectations and offer a point of comparison for your own goals of the surgery.

What you can expect

Facial feminization surgery.

Facial feminization surgery may involve a range of procedures to change facial features, including:

- Moving the hairline to create a smaller forehead

- Enlarging the lips and cheekbones with implants

- Reshaping the jaw and chin

- Undergoing skin-tightening surgery after bone reduction

These surgeries are typically done on an outpatient basis, requiring no hospital stay. Recovery time for most of them is several weeks. Recovering from jaw procedures takes longer.

Tracheal shave

A tracheal shave minimizes the thyroid cartilage, also called the Adam's apple. During this procedure, a small cut is made under the chin, in the shadow of the neck or in a skin fold to conceal the scar. The surgeon then reduces and reshapes the cartilage. This is typically an outpatient procedure, requiring no hospital stay.

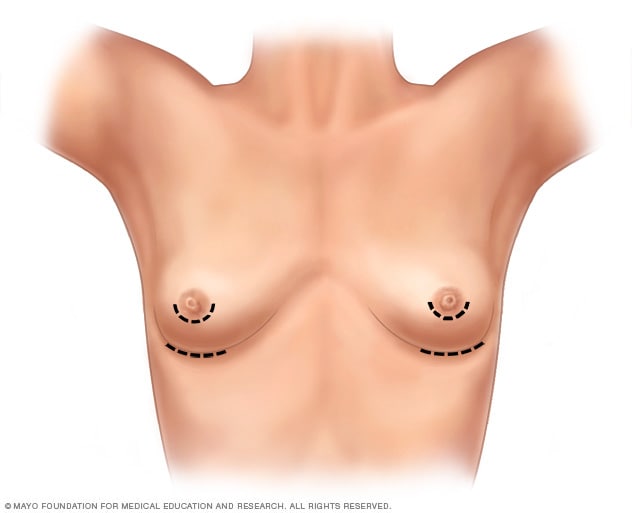

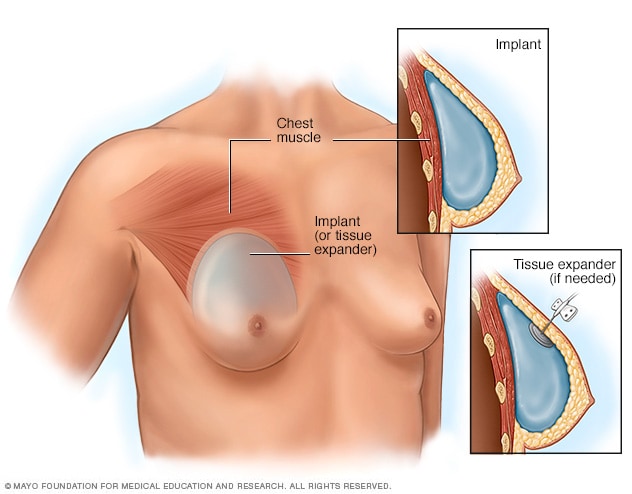

Top surgery

- Breast augmentation incisions

As part of top surgery, the surgeon makes cuts around the areola, near the armpit or in the crease under the breast.

- Placement of breast implants or tissue expanders

During top surgery, the surgeon places the implants under the breast tissue. If feminizing hormones haven't made the breasts large enough, an initial surgery might be needed to have devices called tissue expanders placed in front of the chest muscles.

Hormone therapy with estrogen stimulates breast growth, but many people aren't satisfied with that growth alone. Top surgery is a surgical procedure to increase breast size that may involve implants, fat grafting or both.

During this surgery, a surgeon makes cuts around the areola, near the armpit or in the crease under the breast. Next, silicone or saline implants are placed under the breast tissue. Another option is to transplant fat, muscles or tissue from other parts of the body into the breasts.

If feminizing hormones haven't made the breasts large enough for top surgery, an initial surgery may be needed to place devices called tissue expanders in front of the chest muscles. After that surgery, visits to a health care provider are needed every few weeks to have a small amount of saline injected into the tissue expanders. This slowly stretches the chest skin and other tissues to make room for the implants. When the skin has been stretched enough, another surgery is done to remove the expanders and place the implants.

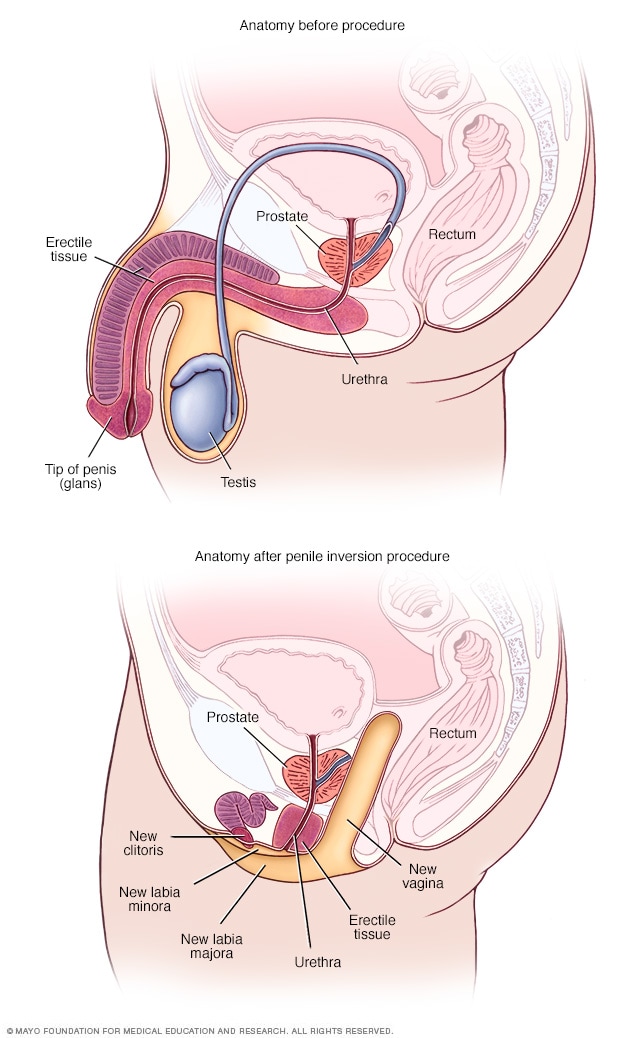

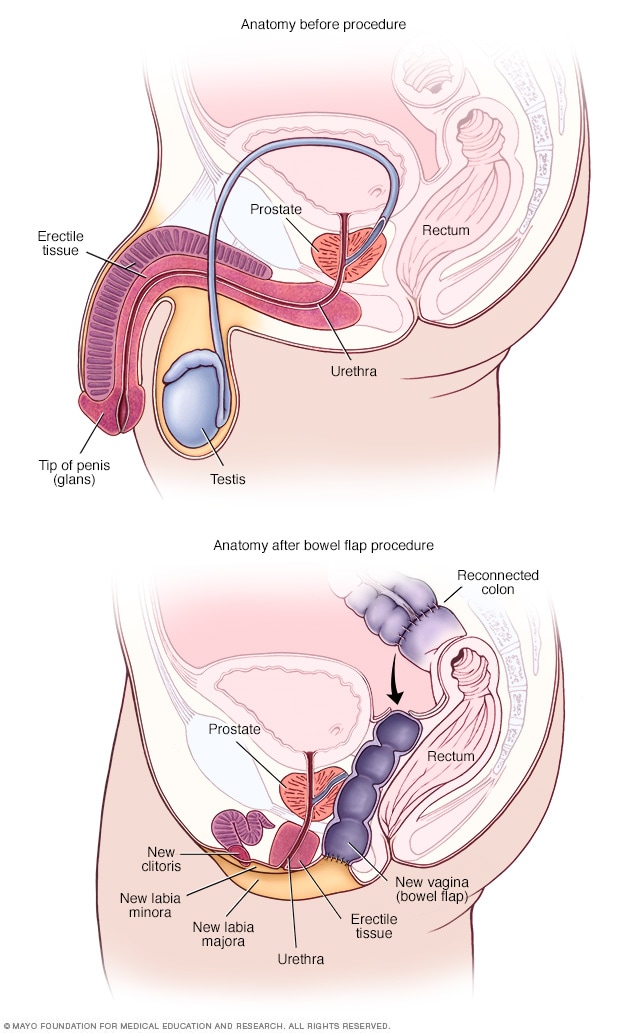

Genital surgery

- Anatomy before and after penile inversion

During penile inversion, the surgeon makes a cut in the area between the rectum and the urethra and prostate. This forms a tunnel that becomes the new vagina. The surgeon lines the inside of the tunnel with skin from the scrotum, the penis or both. If there's not enough penile or scrotal skin, the surgeon might take skin from another area of the body and use it for the new vagina as well.

- Anatomy before and after bowel flap procedure