How to communicate technical information to a non-technical audience

Reading time: about 7 min

Any given project can have a lot of stakeholders, including senior and executive management, employees, stockholders, customers, and so on. These stakeholders are interested in your project, its current status, features and functions, and how it works.

The success or failure of your project might depend on your ability to explain to your stakeholders what the technology in question is, how it is developed and used, and why it will benefit them. It’s important that you get this information right, that you don’t gloss over problem areas, and that the expected outcomes are clear. And if you get buy-in on the project, you’ll have to keep your stakeholders educated, engaged, and up to date on project status.

This might not be as easy as it sounds, especially when you are working with people who have varying degrees of technical knowledge.

So, how do you explain technical concepts to a non-technical audience?

In this article, we will review seven tips that developers, engineers, IT workers, and other technical professionals can use to communicate their ideas more effectively. These can quickly be put into practice in almost any workplace imaginable.

Let’s get started.

1. Know your audience

Before you take any kind of approach, you should think about who your audience is. As you get to know your stakeholders, you’ll get a sense of where they have areas of expertise and the level of their technical knowledge. This way, you won’t waste time explaining stuff they already know or that doesn’t pertain to their role. Is your audience non-techies? Is it a mix of non-technial personnel and fellow technical professionals skilled in other disciplines?

In an audience with different levels of expertise, it’s a balancing act to find the right level of information that is not too simple for more technical team members and is not too complex for those who are less technical. You�’ll want to be thoughtful. It’s best to not give the impression that you are oversimplifying for specific members of your audience.

2. Be attentive to your audience throughout your presentation

Going along with knowing your audience, as you present, be observant of body language and the overall tone of the room. You’ll quickly learn when it’s time to move on and when you need to spend more time on certain information

Whenever you share your technical know-how with a non-technical audience, the goal is to be conversational. Even if you’ve explained the technology dozens of times and know the subject matter inside and out, the people you’re currently talking to might be hearing about it for the first time. Always present with enthusiasm.

3. Incorporate storytelling when sharing technical information

When you have a lot of data or information to share, take time to allow your audience to wrap their heads around your subject, avoiding the urge to cram every detail on a slide and just reading it aloud.

If you’re going to use a slide deck to convey your information, remember that every slide should enhance the presentation and not detract from it. Don’t use boring stock photos or charts that fail to express your message clearly and quickly. Think of each slide in the context of how it will guide your audience along the journey from point A to point B.

As you put together your presentation, always keep your objective or purpose in mind.

To start, what’s the most important takeaway? Are you trying to convince your CMO that no-code platforms for citizen developers will dramatically reduce the product backlog? Or maybe you’re hoping to convince finance that your tech team deserves new equipment? Whatever the situation, storytelling is more persuasive than facts alone.

Stories are effective at planting ideas in the minds of your audience—especially stories told from personal experience. If you don’t have your own relatable or relevant story, use anecdotes taken from recent events or industry publications that fit your needs.

4. Use visuals to explain technical information and processes

Written content and verbal explanations are both essential ways to communicate ideas.

Not surprisingly, many people make regular use of diagrams, models, and other visual presentation techniques to get their point across. If you’re looking for a quick, effective way to visualize and share your content with your organization, there’s Lucidchart.

With its user-friendly templates and interface, you can easily adapt or edit your process workflows to the demands of your non-technical audience. For example, an executive doesn’t necessarily need to review every part of a data flow diagram. They may just want a basic understanding of the structure. With Lucidchart, you can create easy-to-digest diagrams and visuals to share wth stakeholders. Plus, Lucidchart includes Presentation Mode , so you can present the visuals you’ve already put together in Lucidchart without having to transfer anything to a slide deck.

Bonus tip: Lucid Enterprise accounts come with universal canvas , a capability that allows you to seamlessly switch between Lucidchart for diagramming and Lucidspark for whiteboarding . It’s perfect for technical and non-technical teams working together!

Create visuals quickly by using ready-made templates.

5. Avoid technical jargon when possible

The tech world has more than its fair share of technical jargon. Although it may be second nature for you to throw out acronyms like GCP and DBMS, certain terminology may confuse or disengage the less technically savvy members of your audience. Take some time to make sure your audience understands the context of the situation.

If possible, avoid using jargon altogether—it’s typically more effective to say exactly what you mean instead of relying on your audience’s understanding of an acronym. And if there is no better way to say something, you might consider providing a reference guide for any technical acronyms and terms you’ll be using during your presentation or incorporating those definitions into your slides.

6. Focus on impact when explaining technical concepts

Remember, information that might be fascinating to you might not be fascinating (or relevant) to your audience.

When discussing technology, it’s more helpful to highlight what makes it a worthwhile investment rather than how it works. Let’s say, for example, that you were suggesting the adoption of new patching, suppressing, and monitoring protocols for your network. Rather than going on about the latest authentication process technologies, you might focus your discussion on how in 2022, the average cost of a data breach for U.S. businesses was $9.44 million.

Focus on the initiatives and pain points that your audience cares most about, and your interactions will have a much greater impact with executives and other non-technical employees at your organization.

7. Encourage questions

Last but not least, encourage questions throughout your presentation. You might find that some people will nod their heads but not understand what you are saying and are too embarrassed to ask questions. As you go through your presentation, pause and ask, “Are there any questions?” Create an atmosphere where stakeholders feel comfortable asking for clarification and starting conversations.

Explaining things in simple terms is an ongoing practice

Be realistic about how much you can explain to a non-technical audience with a single presentation or interaction. You may need to conduct regular meetings to provide your organization’s non-techies with the in-depth understanding and appreciation they need.

Even if it feels like you’re only making incremental progress, to those who were previously unfamiliar with the technology you share, your efforts may feel like a true revelation.

Lucidchart is the visual workspace where technical professionals can gain visibility into existing tech, plan for the future, and communicate clearly with stakeholders.

About Lucidchart

Lucidchart, a cloud-based intelligent diagramming application, is a core component of Lucid Software's Visual Collaboration Suite. This intuitive, cloud-based solution empowers teams to collaborate in real-time to build flowcharts, mockups, UML diagrams, customer journey maps, and more. Lucidchart propels teams forward to build the future faster. Lucid is proud to serve top businesses around the world, including customers such as Google, GE, and NBC Universal, and 99% of the Fortune 500. Lucid partners with industry leaders, including Google, Atlassian, and Microsoft. Since its founding, Lucid has received numerous awards for its products, business, and workplace culture. For more information, visit lucidchart.com.

Related articles

How to efficiently pull in project stakeholders across teams.

In this blog post, you’ll learn how to identify project stakeholders, why managing stakeholders is important, and how to engage them in your project.

Why team buy-in matters and how to get it

In this article, you will learn why team buy-in matters, and some tips for getting it from your team.

Bring your bright ideas to life.

or continue with

By registering, you agree to our Terms of Service and you acknowledge that you have read and understand our Privacy Policy .

Difference Between Technical and Non-Technical Content Writing

Technical and non-technical content writing is very different. The former has more depth in the quality of the language used and explanations provided, while the latter is more about prioritizing practicality and easy readability. However, both types have their own importance and target audiences.

Technical writing is meant for experts in their field, while non-technical content is usually written for the general audience who aren’t familiar with certain technical terms.

This article will explain the key differences between technical and non-technical content writing. However, let us first have an individual glance over what technical and non-technical content writing means.

What Is Technical Writing?

Technical content can be difficult to write because it requires knowledge of the subject matter and extensive research. Technical writing is not just limited to engineering and scientific fields; any field can have technical documents and manuals if there are products in that domain. Technical writers write about their specific fields of expertise, whereas non-technical writers write about more general topics. Technical content writers may work with engineering, science, programming, or law topics.

Technical content writing requires you to have a deeper knowledge of your industry than just what you see on the surface level. You need to be able to write out processes and procedures as well as explain them in a way that will make sense for your audience.

For example, if you are developing a new app, then the user manual that comes with it becomes technical writing. Similarly, suppose there’s a new technology that’s patented in your country or is an export product. In that case, there will be documents related to the patent application and the machine’s prototype.

So technical writing includes all these things. It can also include anything written for students at the university level who are learning about specific subjects. The writer has to ensure his work is error-free so that students can learn without confusion.

What Is Non-Technical Writing?

Non-technical content writing is any piece of text that isn’t about computers, code, or other technical topics. Non-technical writing can include blog posts, product descriptions, and review articles. A non-technical writer could work in any field, including journalism and copywriting.

For example, let us assume that you are purchasing something online. If you are looking for information about how to use or install your product, then there are certain things that need to be taken into account. You will see entire sentences with no grammatical errors in them; the language has to be easy enough for everyone to understand regardless of their education level, and it should make sense without ambiguity.

This type of writing falls under the category of non-technical writing because it requires good command of vocabulary since most users aren’t experts in fields like engineering or Science. Non-technical content writers may work with marketing, finance, or health care topics.

Difference Between Technical And Non-Technical Content Writing

Technical information is usually more detailed and requires a higher level of understanding on the reader’s part than non-technical information. In most cases, technical information is appropriate only for those in the target industry who need to know specific details about how something works. For this reason, it’s generally not appropriate to use technical language in a blog post unless it’s directed at an audience with high levels of expertise in that area. Many people have a misconception about technical and non-technical content writing services.

Technical Content Writing Example: How Often You Should Change Your Engine Oil?

Processes and procedures are a type of technical writing because it requires you to know what you’re talking about before you put anything down on paper.

Technical content writing would require you to research oil changes for a specific make and model of car as well as explain the process step by step as if someone is performing this task for the first time without any prior knowledge or experience.

This is where understanding your industry really comes in handy; if you were hired to write an article about how often people should change their oil, you should be able to come up with some pretty accurate numbers based on each different scenario which will allow your audience members to know exactly when they should consider changing their oil.

Also, all types of documentation, manuals, etc., come under technical writing.

Non-Technical Content Writing Example: Why Netflix is So Popular?

Non-technical content writing talks about concepts and ideas without any steps to get there or processes required. This type of writing does not require you to know anything outside of the general overview of your industry.

Why Netflix is so popular won’t require any writer to have a profound understanding of technical specifications that someone who is writing on engine oil change will need to have. Technical writers write about their specific fields of expertise, whereas non-technical writers write about more general topics.

Non-Technical Content Writing vs. Technical Content Writing Comparision

Technical content writers may work with topics that include engineering, science, medicine, computer science, engineering, and programming, the law. Non-technical content writers may work with topics like marketing, finance, historical events, opinions, biographies, or personal care. There are many ways to break down the differences between technical and non-technical content writing. Technical content typically consists of a list of instructions, features and benefits, and specifications. Non-technical content is written primarily for your blog readers or a general audience. Non-technical content refers to any type of writing that is not primarily intended for the purpose of conveying information about a commercial product or service (e.g., an article, essay, story, or speech). Depending on your industry and your business type, one type of writer will be more suitable for your needs.

How to Decide Which Type of Writer You Will Be?

There are many factors that go into deciding which type of content writer you will be. While some people may find writing about something they know more rewarding, others may prefer the challenge of writing about a topic they know nothing about. If you’re reading this article and have no idea what type of content writer you want to be, consider these three questions:

1. Do you enjoy technical topics?

2. Are you passionate about what you write about?

3. Do you enjoy non-technical topics?

If you answered yes to all three questions, then it’s likely that technical content would suit your needs best. If any one of them is a “no,” then it’s most likely that non-technical content writing would suit your needs better. The most important thing is to find something that interests and excites you, whether it’s technical or not.

The Final Words

If you are looking to publish research papers, your standards must be different from someone who writes fiction. Different businesses require different types of content writing. Technical writing and non-technical writing both provide businesses to accommodate all types of required content types.

Kanchi is an SEO writer who enjoys creating content. She is a relentless work bee, buzzing with innovative ideas. A cheerful person, a creative mind, and an articulate professional, she believes in taking life one day at a time.

Related Posts:

Writer’s Guidelines for Creating High-Quality Content

Content Writing: Its Origin, History, and Relevance in Modern Context

How to Follow Content Writing Guidelines by Google?

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What It Takes to Give a Great Presentation

- Carmine Gallo

Five tips to set yourself apart.

Never underestimate the power of great communication. It can help you land the job of your dreams, attract investors to back your idea, or elevate your stature within your organization. But while there are plenty of good speakers in the world, you can set yourself apart out by being the person who can deliver something great over and over. Here are a few tips for business professionals who want to move from being good speakers to great ones: be concise (the fewer words, the better); never use bullet points (photos and images paired together are more memorable); don’t underestimate the power of your voice (raise and lower it for emphasis); give your audience something extra (unexpected moments will grab their attention); rehearse (the best speakers are the best because they practice — a lot).

I was sitting across the table from a Silicon Valley CEO who had pioneered a technology that touches many of our lives — the flash memory that stores data on smartphones, digital cameras, and computers. He was a frequent guest on CNBC and had been delivering business presentations for at least 20 years before we met. And yet, the CEO wanted to sharpen his public speaking skills.

- Carmine Gallo is a Harvard University instructor, keynote speaker, and author of 10 books translated into 40 languages. Gallo is the author of The Bezos Blueprint: Communication Secrets of the World’s Greatest Salesman (St. Martin’s Press).

Partner Center

How to Explain Technical Concepts to a Non-Technical Audience

Like it or not, techies are getting pushed out from the backroom to the front lines. Increasingly, you find yourself standing in front of non-technical audiences – customers, C-suite members, finance, cross-functional team members, and other stakeholders – expected to explain tech concepts in simple terms.

Need some help? Here are six proven strategies you can use to communicate tech concepts to a non-technical audience effectively.

Establish relevance upfront

Your audience will be much more receptive to your information if they understand how it will impact them. Sure, you want to explain the process roadmap, but it may be a good idea to begin by explaining the point of arrival.

Preparation is the key here. Do your homework beforehand to understand what will be considered relevant information by the audience, and then craft your presentation to address the what’s-in-it-for-me question upfront and early on in the interaction.

Avoid information overload

While you may have a lot of information to share, cramming every detail down the audience’s throat will not help.

Be selective and keep paring the content. Consider what is essential to the audience. Try and anticipate the questions they will ask. And then, remember to stay focused on the most important and relevant points during the discussion.

Been asked to assess one cybersecurity tool against another in a limited time? Instead of contrasting the technology that powers the tools, focus on how the tools will translate into ROI, risk mitigation, and functionality.

Tell a Story

Everyone loves a good story. So, weave one around your message. Don’t just make a presentation; take the audience on a journey. When planning each slide, see how it will push the presentation’s overall narrative forward.

Incorporate personal anecdotes, examples, and analogies to make your point. If you don’t have any personal stories that relate to the situation, research. Use relatable events to make your case.

Junk the Jargon

The abbreviated terms and domain-specific terminologies that are a second language for you are alien to your audience. You need to ditch the jargon.

Peppering the conversation with lots of technical terms may lead to audience disinterest and disengagement. Instead, try to simplify and explain concepts as much as possible.

If a lot of detail is required, and/or you are unsure about the audience’s technical expertise, distributing a jargon cheat sheet before getting into the presentation/interaction may be a good idea.

Use visuals aids

Why waste half the meeting trying to explain a point when a few pictures can illustrate the point much more quickly.

Visual content is highly effective in communicating technical processes and concepts. As per studies, 65% of people are visual learners. Therefore, visual aids are valuable for helping non-technical audiences understand technical concepts.

Do leverage diagrams, models, and other visual presentation techniques to drive home your point.

Ask for feedback, invite questions

Communication is a two-way street. Along with saying your piece, focus on the audience’s response. Do your listeners have any questions? Are they seem to be following your pace? Look out for implicit cues and seek explicit feedback as well.

Take frequent breaks to invite questions and clarify points. Be respectful of the audience’s technical knowledge limitations.

You also might be interested in

Salary Negotiation 101: How to Get the Pay You Deserve

Reading Time: 3 minutes Introduction In the professional world, salary[...]

Artech and BPO (Business Process Outsourcing) Services

Reading Time: 2 minutes BPOs (Business Process Outsourcing) is an[...]

Selecting Your Managed Service Provider Partner: 8 Key Pointers for Success

Reading Time: 9 minutes The Managed Services market is booming. And how! As per an IDG report[...]

Recent Posts

- Mastering the Art of Professional Communication: A Comprehensive Guide

- The Power of Analytical Skills in Professional Decision-Making and Problem-Solving

- The Comprehensive Guide to Interview Questions and How to Answer Them

- From Employee to Leader: Cultivating Essential Leadership Skills for Career Growth

- Effective Communication: The Job Skill That Accelerates Professional Success

© 2024 · Artech LLC.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Artech Employee Online Forum Policy

USA & Canada

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay connected with the latest from Artech

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

How to Present Data to a Non-Technical Audience

When you?re presenting data analytics or any technical information to a non-technical audience, it can be difficult. You have to think about the components of a good presentation in general, but also how to simplify complex subjects and information and make them resonate with your target audience. If you?re someone who understands data analytics well or is highly technical, it can be especially challenging to know how to make your presentation work for the needs of an audience which is different from you. The following are some presentation tips that can help you in general, but especially with a non-technical audience.

Choose the Right Presentation Software

Presentation software

can make a huge difference in the quality of your presentation, and also how well you?re able to present difficult concepts to your audience in a way they?ll understand. Having a good platform to create and present from within will not only help you engage with non-technical audiences ?it will help you with any presentation for any audience. The following are some features to look for in presentation software.

Comparative Analysis of Two Top Big Data Transfer Services

Fundamentals of c++ programming for data scientists, linux vps management skills for data scientists, how ai is changing data analytics in 2024, data mining helps dropshipping companies discover products.

- Appealing transitions: Transitions are important because you want to keep your audience engaged during these shifts.

- Real-time Co-Authoring: This feature means that if you share your presentation with anyone they?ll have the ability to ask questions and make comments. You should look for a platform that lets you provide varying levels of access to different collaborators.

- Video Conference: If you have video conferences that are part of your presentation software, it makes for a more seamless experience.

Know Your Audience

You may think you know your audience just by having the understanding that they?re non-technical, but that only tells a small part of the story. There can be a lot of variance within that parameter, so work on getting to know your audience not just right before you give your presentation, but when you?re building your presentation.

Data Visualization

Data visualization can be one of the most important components of a presentation, but also one of the most challenging to tailor to the needs of your audience. A few things to consider here include:

- What are the decisions being made by your audience, and what do they already know versus what they need to know? You need to tailor your insights and visualizations directly to helping them make the decisions they?re responsible for.

- How will you break down the text versus the graphics? This day in age, with everyone in a time-crunch, it can be best to aim for 80% graphics compared to 20% text, or at least something close to those estimates.

- Consider giving handouts to complement your presentation. This doesn?t mean copies of the full presentation?those aren?t likely to be very useful. Instead, create handouts that summarize maybe 5 or so of the most important points from your presentation.

What Types of Charts Work Best?

The specific types of charts you implement into a data-based presentation vary depending on your audience, but also the type of information being presented. For example, bar charts tend to work well as a way to show aggregated data and compare data across larger categories. Bar charts also tend to be very digestible for an audience with no technical background. Line charts can be a little more complex, but still workable if your audience isn?t technical. Line charts can be used to show changing values over time. Pie charts aren?t necessarily the best way to show data unless that data adds up to 100%. Pie charts shouldn?t have more than four categories, and they aren?t good for presenting a lot of details. Additionally, there?s not really any reason to use 3D charts. They don?t add value to a presentation, other than they might capture more visual interest.

Tell a Story

When you?re giving a presentation, even if it?s filled with numbers and data, you want to think of yourself as a storyteller. You want to take your findings, and weave them into something cohesive with a beginning, middle, and end. Keep your visualizations simple, and ensure that they work with the story to deliver overall findings. Work on presentations with a logical flow from the beginning to the end, and don?t make your audience come to their own conclusions. Those conclusions are ultimately part of the story you?re telling. Finally, most presentations fall flat because of too much information rather than too little. Go through every slide and make sure that it fits with your story and tells something that your audience absolutely needs to know to understand the story.

Follow us on Facebook

Latest news.

Cloud Technology Changes Role of Soft Skills in Nursing

AI Leads to Breakthroughs in GUI Brainstorming Software

AI Helps Businesses Save Money with Better Financial Management

Gen AI Helps Developers Automate Writing Coding

Stay connected.

Sign in to your account

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Technical VS Non-Technical Content: 3 Key Differences

When it comes to creating content for your website, you have two main options: technical content or non-technical content. But what’s the difference? And which type of content is right for your business? In this blog post, we will discuss the differences between technical vs non-technical content. Also, we will help you decide which type of content is best for your website.

What is non-technical content?

Non-technical content is any content that does not require specialized knowledge or training to understand or write. This can include things like instructions, descriptions about general information. While non-technical content does not require expert knowledge, it still needs to be well written and easy to understand.

To accomplish this, writers of non-technical content must use clear and concise language . They should also avoid using jargon or technical terms that might confuse readers. By keeping these things in mind, writers can ensure that their non-technical content is accessible and informative.

What is technical content?

Technical content is a type of written content that covers a wide range of topics, from software to hardware to engineering. It educates the reader on a particular subject or to provide instructions on how to use a product or service. Also, it explains in simple terms how a system or process works. These allow the reader to make an informed decision while he understands the technicalities.

You can find technical content in a variety of formats. These include HOW-TO guides, manuals, tutorials, online documentation, online manuals, user guides, and blog posts.

While someone might think it might be denser and more difficult to read than other types of writing, it is essential for businesses that want to provide accurate and up-to-date information to their customers. By understanding what technical content is and how it can be used, businesses can ensure that their customers have the information they need to make informed decisions.

Technical Content VS Non-Technical Content: 3 Key Differences

Businesses often need to produce both technical and non-technical content. But what’s the difference between the two, and why does it matter?

There are a few key considerations to keep in mind when determining which type of content is right for your business blog.

The target audience.

If you’re trying to reach readers who are interested already in your field and want to understand, for instance, how products work, then technical content may be more appropriate. If you’re hoping to reach a wider audience with your blog who doesn’t know about your company or products yet, then non-technical content may be more effective.

The information someone wants to communicate.

Technical content is typically more detailed and specific, while non-technical content is more general and broadly focused.

The goals for the content/ blog.

If you’re looking to educate your readers about your products or services, then technical content may be more appropriate. However, if you’re trying to generate leads, then non-technical content may be more effective.

No matter what type of content you choose for your business blog, the most important thing is that it is well-written and informative.

But the process of writing these can show even more differences between the two. Therefore, we recommend you read our article Technical Writing VS Content Writing: The 8 Differences.

The benefits of Publishing technical content on your website

In today’s competitive marketplace, a website is essential for any business that wants to succeed. And while a website can serve many purposes, one of the most important is to provide information about your product or service.

Technical content can help your website visitors understand what you offer and why it is valuable. By including technical information on your website, you can show potential customers that you are an expert in your field. You also can show them that you commit yourself to providing them with the best possible product or service.

In addition, technical content can also help to improve your search engine ranking, making it easier for potential customers to find your website. As a result, including technical content on your website is an essential part of promoting your business online.

The benefits of Publishing non-technical content on your website

In a world where technology is constantly developing, it’s easy to get caught up in the latest trends and forget about the importance of non-technical content. However, there are many good reasons to include non-technical content on your website.

For starters, it helps to humanize your brand and make it more relatable to your audience.

In addition, non-technical content can help to build trust and credibility with your audience by providing valuable information that is not overtly salesy or promotional.

Finally, non-technical content can also serve as a valuable SEO tool, helping you to attract less experienced users, who may eventually be interested in learning more about your products or services, to your site and improve your search engine ranking.

Ultimately, including a mix of technical and non-technical content on your website can help you reach a wider audience and achieve your business goals.

How to know which type of content is right for you?

Technical content is typically more detailed, offering in-depth explanations and instructions. Non-technical content generally can be easier to digest. But which type of content is right for you and your business? Here are three factors to consider:

The type of business you’re in

If you’re in a highly technical field, such as engineering or web development, then technical content is probably a better fit. If you run a more general business, such as a retail store or a restaurant, non-technical content may be just what you need.

The tone of your website

You should consider the tone of your website when deciding between technical and non-technical content. A site with a serious, professional tone will probably benefit from technical content that is straightforward and informative. A site with a more lighthearted tone can get away with non-technical content that is more conversational and even humorous.

Your target audience

Generally, people gear technical content towards people who are already familiar with the subject matter. If you’re targeting beginners or laymen, then non-technical content may be a better choice. Technical content can also be a good option if you want to attract experienced professionals to your site.

In conclusion, technical content vs non-technical content is a matter of preference. It really depends on the type of business you have, your target audience, and the tone of your website, and your target audience. Ultimately, the best way to determine which type of content is right for you is to experiment and see what works best for your business.

Related posts:

- Law Firm SEO Services

- 20 Content Writing Tips For Higher Conversions

- Technical Writing VS Content Writing: The 8 Differences

- What Is Content Writing? Plus 12 Tips For Better Results!

- Technical SEO Company: Your Key to Enhanced Digital Visibility

- The Difference Between SEO and Content Writing

- Technical SEO for Law Firms

- SEO Best Practices

The Ultimate Local SEO Checklist For Law Firms

Ready to Transform Your Law Firm's Online Presence?

Unlock the full potential of your online presence with Inoriseo. Let’s build a strategy that reflects the ambition and expertise of your law firm.

Table of Contents

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

nontechnical

Definition of nontechnical

Examples of nontechnical in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'nontechnical.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

1833, in the meaning defined above

Dictionary Entries Near nontechnical

nonteaching

nontemporal

Cite this Entry

“Nontechnical.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/nontechnical. Accessed 27 May. 2024.

More from Merriam-Webster on nontechnical

Thesaurus: All synonyms and antonyms for nontechnical

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

More commonly misspelled words, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, how to use accents and diacritical marks, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - may 24, flower etymologies for your spring garden, 9 superb owl words, 'gaslighting,' 'woke,' 'democracy,' and other top lookups, 10 words for lesser-known games and sports, games & quizzes.

30,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- Interview /

Non Technical Topics for Group Discussions

- Updated on

- May 22, 2023

Group Discussion (GD) is a common methodology utilised by different types of organizations, be it recruiters or academic institutions in order to assess candidates on their analytical reasoning and thinking capabilities. These discussions are generally conducted to test applicants’ logical reasoning and spontaneity as well as how creatively they can come up with probable arguments for a given topic. While the allotted subject of discussion might vary as per the course or career profile, there are some general topics related to the latest happenings and social issues that might be given for GDs. This blog aims to describe some of the major non technical topics for group discussions that you should definitely know about!

This Blog Includes:

List of non technical topics for presentation, non technical topics for group discussion on environment, general non technical topics, social and political issues , economic issues , how to prepare for non technical topics for group discussions, gd topics on general issues with answers.

For presentations, there is a multitude of non technical topics from diverse fields that you can choose from. To help you with your research, we have curated an extensive list of non technical topics for presentations given below:

- Covid-19 and its Impact on World Economy

- Online Learning: Benefits, Challenges and Opportunities

- Social Media and Social Businesses

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Social Media

- Communication Skills

- Soft Skills

- Climate Change

- Principles of Management

- Marketing Strategy

- Inventory Management

- Social Media

- Classroom Management

- Entrepreneurship

- Logistics Management

- Natural Resources

- Thermal Pollution

- Noise Pollution

- Land Pollution

- Sources of Water

- Operations Management

- Marine Pollution

- Materials Management

- Radioactive Pollution

- International law

- Chromatography

- Air Pollution

- Water Pollution

- Disaster Management

- Child Labour

- Organic Farming

- Impact of Technology on Teaching and Learning

- Internet & Traditional Media

- Sustainable Agriculture

- Food Engineering

- Technology & Medical Science

- Identity Theft

- Cyber Crimes

- Juvenile Justice System

- Impact of Technology in Crime Prevention

- Importance of Sanitation

- Air Quality

- Vehicular Pollution

- Swacch Bharat Mission

- Revival of Groundwater Reservoirs

- Shift to the Renewable Sources of Energy

- Harmful Effects of Blaring Music

- Save Wildlife and Environment

- Cutting of Hills and Clearing of Forests to Level the Land

- Usage of Fossil Fuels in Household Chores

- Effects of Dumping E-waste into Landfills

- Are Dams a Disruption to the Natural Flow of the Rivers?

- Should Burning of Fodder be Made Illegal?

- Deposition of Waste in the Flow of the Rivers

- Should Bursting of Firecrackers be Banned?

Whether it is for group discussion, seminar or classroom presentation, finding technical topics can be quite an arduous task. Before providing you with the titles for GD and Presentation, check out some of the prominent non technical topics you can use for both these purposes:

- Profit is the only motive of business. Take a stand.

- Consumer is king.

- Advances in technology in today’s world – boon or bane?

- Hyper competition has killed the telecom industry.

- Depreciation of rupee: boon/ bane for the economy?

- Criticism – is it good or bad?

- FDI in Retail – Advantages & Disadvantages

- Women’s empowerment leads to social development.

- Online Social Networking is a parallel world. Do you agree?

- Role of media in the digital era.

- Green Technology

- Future of Technology

- Technologies are a core strength of the nation.

- Same-sex marriage

- Driving and restraining forces impact global integration and international marketing.

- What does the future hold for global governance?

- How is Artificial Intelligence changing businesses?

- Social Media & Privacy

- Social Literacy Skills

- Implications of Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 in India

Being aware of the ongoings of the world that surrounds us is crucial for successfully clearing the GD part of your application process. Some of the major social and political issues are listed down to help you gauge the different types of non technical topics you might get:

- Impact of Social Media on the Younger Generation

- Values Exhibited Through the Different Mediums of Art and its Impact

- Brand Frenzy Culture

- Section 377

- Censorship of Art

- Caste Discrimination

- Female Foeticide

- Rapid Population Growth

- Reel Life v/s Real Life

- Role of Physical Fitness

- Equal Rights for Women

- Single Parent

- Child Marriage

- Gender Sensitivity

- Juvenile Crime and Punishment

- Right to Privacy

- Joint Family V/S Nuclear Family

- Co-ed V/s Girls/Boys School Education

- Man-made Environment v/s Natural Environment

- Role of Media in our Society Highlighting the Media Trials

- Importance of a Psychologist in One’s Life

- Importance of Bringing Taboos into the Public Sphere

- Vitality of Being Self-Dependant

- Article 370

- The Thread of Unity That Runs Across All Cultures and Ethnicities

- Should Steps be Taken to Solve the Problem of Students Having to Carry Heavy Bags

- Should Basic Requirements to Become a Politician be Revised?

- Should Mobile Phones be Allowed in Schools?

- What Does a Uniform in an Institution Represent?

Other recurrent debates that happen in GDs are related to economic issues on national as well as global level. Take a look at the following non technical topics for group discussion under the domain of Economics:

- Goods and Services Tax (GS)

- Offshoots of Demonetization

- How safe are Digital Transactions?

- Impact of COVID on Economy

- Economic Reforms

- Would Aadhar be Successful in Replacing the Social Security System?

- Dynamics of the Current Start-up Culture

- Real Estate of India

- Wide Socio-economic Gap

- Economic Reservation

A group discussion usually involves multiple participants (around 5-15) and a moderator who facilitates the whole discussion by allotting the topic, mediating it and regulating it in a way that does not allow much of a deviation. Further, he also plays a role in assessing different candidates and their logical abilities based on their arguments, how they are framed as well as their quick thinking and responses given in a timebound manner.

- When it comes to handling non technical topics, you need to be updated about the recent news developments across the globe.

- Further, you should be able to think on your feet if there are topics given under ‘for’ and ‘against’.

- Let the other person speaks and then give your viewpoints.

- You should not act in a belittling manner or try to act superior because how you say it matters more than what you are saying.

Advantages: Fossil fuels are the most commonly used sources of energy in households and it is also the cheapest and most easily available option. Disadvantages: Fossil fuels are a nonrenewable resource along with being a major source of pollution and global warming .

For: There is an extensive need for land both for increasing agricultural output to feed the rapidly increasing population and for setting up buildings and factories. Thus cutting of hills and clearing forests are necessary. Against: Cutting of hills and clearing forests caused deforestation, which is a leading cause of global warming. Additionally, it can lead to soil erosion, a decline in biodiversity as increased pollution levels in the atmosphere.

Yes: Firecrackers not only cause a lot of air pollution but are also harmful to people with heart ailments due to the noise they produce. No: Bursting firecrackers are a means of celebrating a variety of events such as marriages, victory, new year celebrations etc. It should not be banned but steps can be taken to moderate its use.

Good: Criticism when provided in a constructive manner can help us work on our shortcomings and improve ourselves. Bad: Continuous criticism in a derogatory manner can lower the self-esteem of a person.

Positive: Social media is a great way to not only be connected with your friends and family but also is useful in keeping yourself updated with all the latest news and events. Negative: On the other hand, social media is extensively used to spread fake news which may have many harmful effects. Also, the cases of online harassment and bullying are increasing day by day.

Yes: Mobile phones are a necessity today. Students can contact their families in case of any emergency or accident that might happen. No: Allowing mobile phones in school may lead to a student constantly using it to play games or surf the internet while neglecting their classes

The Future of Banking in India. Rise of Protectionism. Rising heat waves. Celebrity Endorsement of Products. Effect of ChatGPT on Journalism. Biohacking. Thorium for clean unlimited enegry. India-Japan Relations.

A Topic-Based Group Discussion involves assigning a topic to the group and asking the members to discuss it. These subjects could fall into one of four categories: Controversial themes, Knowledge-Based Topics, and Abstract Topics are all examples of such themes.

Observe the Group Discussion Guidelines Key Group Discussion abilities include speaking logically, being audible, presenting your argument clearly, and acting as a leader. Use every opportunity to enter the discussion to further your position. Read through some sample and actual Group Discussion rounds.

Hence, now that you know the major non technical topics for group discussion, you can start jotting down the pointers and gear up towards the ultimate day of your GD. Whether you are a student going through the screening process of an academic institution or a fresher prepping up for the selection rounds, our Leverage Edu experts are here to assist you throughout the preparation process and ensure that you soar smoothly through the journey of actualising your dream career ambitions.

Team Leverage Edu

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Leaving already?

8 Universities with higher ROI than IITs and IIMs

Grab this one-time opportunity to download this ebook

Connect With Us

30,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

September 2024

January 2025

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Non-technical Skills in Healthcare

- Open Access

- First Online: 15 December 2020

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Stavros Prineas 5 ,

- Kathleen Mosier 6 ,

- Claus Mirko 7 &

- Stefano Guicciardi 8 , 9

16 Citations

Non-technical Skills (NTS) are a set of generic cognitive and social skills, exhibited by individuals and teams, that support technical skills when performing complex tasks. Typical NTS training topics include performance shaping factors, planning and preparation for complex tasks, situation awareness, perception of risk, decision-making, communication, teamwork and leadership. This chapter provides a framework for understanding these skills in theory and practice, how they interact, and how they have been applied in healthcare, as well as avenues for future research.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Non-technical Skills for Anesthesia Technician

Development of instruments for assessment of individuals’ and teams’ non-technical skills in healthcare: a critical review

TeamSTEPPS: Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety

- Non-technical skills

- Paratechnical skills

- Patient safety

- Human factors

- Performance shaping factors

- Situation awareness

- Risk perception

- Decision-making

- Communication

1 Introduction

Non-Technical Skills (NTS) can be defined as a constellation of cognitive and social skills, exhibited by individuals and teams, needed to reduce error and improve human performance in complex systems . NTS have been described as generic ‘life-skills’ that can be applied across all technical domains [ 1 ]; they are deemed to be ‘non-technical’, in that they have traditionally resided outside most formal technical education curricula. While the importance of human factors in the performance of technical tasks has been appreciated for over 80 years [ 2 , 3 ], NTS as a formal training system is derived from aviation Crew Resource Management (originally called Cockpit Resource Management). CRM was first adopted by United Airlines in 1981 [ 4 ] after a series of high-profile air crashes in the late 1970s, in which human elements such as poor communication, teamwork and situation awareness were identified as key contributing factors [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. CRM is now fully integrated into all commercial pilot training worldwide; in a constant state of evolution, it is currently in its sixth generation [ 8 ].

In healthcare, it was not until the 1990s that the significance of human factors in patient safety became more widely publicised [ 9 ], coinciding with the rise in medical simulation [ 10 ]. In 1999, an emergency medicine team training project, MedTeams, was launched [ 11 ]. The following year two landmark reports were published within weeks of each other: To Err is Human in the USA [ 12 ] and An Organisation with a Memory in the UK [ 13 ]. These inspired a burgeoning of research into applied human factors in healthcare. Flin pioneered a behavioural marker system known as Anaesthetists’ Non-Technical Skills (ANTS: [ 14 ]), followed by Non-Technical Skills for Surgeons (NOTTS: [ 15 ]). The disciplines of anaesthesia, critical care and surgery remain at the forefront of NTS training in medicine. Several other multidisciplinary clinical NTS frameworks, including the Oxford NOTECHs system [ 16 ] and TeamSTEPPS™ [ 17 ], have also been implemented and studied in real and simulated clinical environments.

As NTS evaluation and/or training systems become increasingly incorporated within undergraduate and postgraduate technical curricula, and specific techniques are developed (especially in communication skills) supported by a growing body of research, a paradox arises: many non-technical skills no longer qualify as being ‘non-technical’. Moreover the term ‘non-technical’ appears to subordinate these skills to their technical counterparts, when in reality the two skill sets are both essential and inseparable, especially during the management of medical crises. In time new terms may be required (e.g. ‘paratechnical’ skills, Clinical Resource Management) to define and describe this group of skills, and to consolidate their true place in the clinician’s armamentarium.

1.1 Practical Overview of NTS Training Topics in Healthcare

The standard NTS training topics are summarised in Table 30.1 and detailed in the rest of this chapter. It is important to recognise that these skills are intertwined not only with the more traditional skills they support, but also with each other. Proficiency in one non-technical skill is, to no small extent, dependent on proficiency in the others. Newer generations of aviation CRM have introduced new topics, e.g. the acquisition of expertise and managing automation. It is foreseeable therefore that these topics will be incorporated into future clinical NTS training programmes.

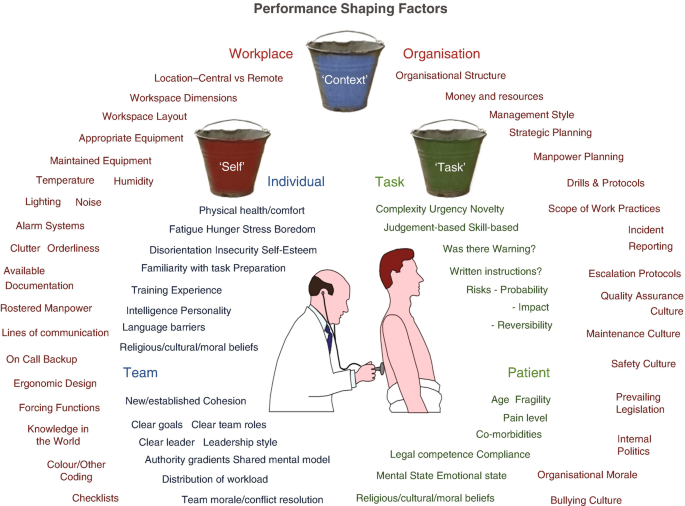

2 Performance Shaping Factors

Most work environments operate on the assumption that adequate training, experience and motivation are enough to ensure successful performance. These prerequisites are necessary but not sufficient, especially in a complex adaptive system such as healthcare. There are many factors that can influence human performance—over long periods of time, from day to day, or in a given moment. Performance Shaping Factors (PSFs) can be classified according to a clinical adaptation of Reason’s ‘Three Buckets’ model [ 18 ] where the traditional categories of ‘task’ (factors inherent to the nature of the task), ‘self’ (internal and personal factors) and ‘context’ (environmental factors) are each sub-divided into ‘task/patient’, ‘individual/team’ and ‘workplace/organisation’ factors, respectively (Fig. 30.1 ).

Performance Shaping Factors. A clinical expansion of Reason’s Three Buckets model

The ability to identify and evaluate PSFs in everyday practice may be a useful skill for frontline clinicians. The Three Buckets model can be applied both prospectively and retrospectively. In 2008, the UK National Patient Safety Agency launched a Foresight Training Resource Pack [ 19 ], based on a simplified version of the Three Buckets model, to help nurses and midwives better foresee clinical risks. This package is currently used in a number of NHS Trusts. As a retrospective incident analysis tool, Contributory Factors Analysis, also known as the ‘London Protocol’ [ 20 ], is based on a similar principle, as is the HEAPS incident analysis tool used in Queensland Health [ 21 ] and other health networks in Australia. A quick Three-Bucket summary can be used to highlight PSFs relevant to cases presented at, e.g. Grand Rounds or M&M meetings.

3 Planning and Preparation Skills

Popular culture is full of references stressing the importance of planning and preparation before performing complex tasks: ‘Be Prepared’, ‘Plan the Dive and Dive the Plan’, ‘Luck favours the prepared’, ‘P to the seventh power’ (‘Prior Preparation and Planning Prevents P—Poor Performance’), etc. In teaching hospital settings, medical and nursing trainees are often asked to perform tasks for which they are ill-prepared. In these efforts they are not only hampered by the opportunistic nature of teaching in clinical settings, but also by the culture of ‘see one, do one, teach one’, a tradition that is counter-intuitive to human-factors thinking and seemingly peculiar (among high-risk endeavours) to medical and nursing education. ‘SODOTO’ training has both critics [ 22 ] and defenders [ 23 ]. Simulation Based Education (SBE) can be used to demonstrate the consequences of poor preparation and planning in a safe setting [ 24 ].

While there are a number of system tools that can help and guide staff (orientation days, checklists, pre-prepared procedural kits, etc.), the question arises as to whether there is a set of definable human competencies/aptitudes that optimise planning and preparing for tasks, and whether this can be taught. The answer to the first part of this question appears to be ‘yes’, in that evaluation of planning, preparation and prioritisation skills are key elements of the ANTS behavioural marker system. These help researchers identify ‘good’ and ‘poor’ task management behaviours in simulated settings, with the highest inter-rater reliability of the four main ANTS categories [ 25 ]. However, the ANTS system is not designed to address how to train practitioners to plan and prepare better.

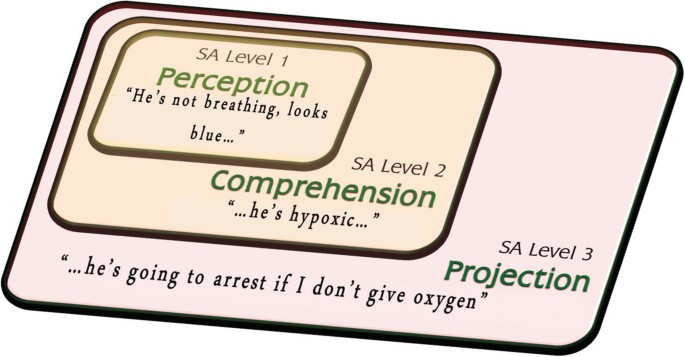

4 Situation Awareness and Perception of Risk

Situation awareness (SA) is defined as ‘the perception of elements in the environment, the comprehension of their meaning in terms of task goals, and the projection of their status in the near future’ [ 26 ]. Perception is essentially being aware of and/or gathering available information relevant to a situation. In a clinical context this correlates with taking a clinical history, examining a patient, reviewing the results of investigations and tests, receiving a handover, conducting a briefing, etc. Comprehension is the ability to form a mental model that makes sense of the available information. In clinical practice, this would be similar to forming a diagnosis, or a differential of diagnoses. Projection is the ability to use an operating mental model of a situation to foresee potential future states, or as clinicians would say, to make a prognosis. A simple example is given in Fig. 30.2 .

Situation Awareness (SA) in a clinical context. (Courtesy of ErroMed, reproduced with permission)

In traditional medical training, these levels of awareness are built upon each other. For example, trainees are (rightly) encouraged to take a history and examine a patient (Level I SA) before venturing a diagnosis (Level II SA). The SBAR/ISBAR communication tool (see below) is a way of serially organising information to facilitate situation awareness between individuals. In real life however, perception, comprehension and projection may not occur in that order. In many emergency situations it is possible, indeed potentially crucial, to prognose the need to resuscitate (Level III) before one has made a complete examination (Level I) or a definitive diagnosis (Level II). This concept of parallel rather than serial cognitive processing of SA is the hallmark of Naturalistic or Recognition-Primed Decision-Making, and a feature of expert cognition [ 27 ], described figuratively as ‘seeing the past, present and future at the same time’ [ 28 ].

In anaesthetic practice, [ 29 ] described a model of ‘distributed situation awareness’, emphasising that during an operation the patient’s condition is constantly being modified by the interventions of the anaesthetist and the surgeon in real time. Thus, in this model, ideal SA is the result of a dynamic and iterative process of regularly scanning the environment, matching one’s mental model with incoming information, modifying the anaesthetist’s plan and actions accordingly, and cycling through this process repeatedly until the patient is safely in the recovery unit.

4.1 ‘Perception of Risk’

When thinking about potential adverse future states, a number of terms— hazard , threat and risk —are often used interchangeably, when they would perhaps be better used to connote overlapping but distinct concepts. A hazard is anything that could potentially go wrong or cause harm, without any qualification of its likelihood or severity. For example, when asked to list the possible complications of central venous catheter insertion, a medical student will often recite a list of early and late complications, subcategorised according to anatomical location, structure type, etc. The student has no direct experience of central line insertion and therefore limited ability to rank this list of hazards according to their likelihood of occurring in routine practice, or what the real impact of each complication would be.

A threat is the subjective perception of a hazard. It is important to recognise, independently of whatever data exists for a given situation, that a number of factors influence the perception of danger, including gender [ 30 ], healthcare role and length of experience [ 31 ], primacy (the disproportionately ‘formative’ impact of early experiences or first impressions: [ 32 ]), recency (the disproportionate impact of most recent experiences: [ 33 ]), whether a person has volunteered to accept the hazard or had the hazard imposed upon them [ 34 ], whether the hazard is familiar or hitherto unknown [ 35 ], whether the effects are immediate or delayed [ 36 ], etc. If, for example, the medical student above, now a resident, were unlucky enough to cause a chylothorax with an early central line insertion, the complication would tend to figure prominently in that resident’s future assessments for a considerable time afterwards, even though in objective terms such a complication is very rare.

Subjective factors influence threat assessments, which in turn can influence clinical decision-making. For example, a Canadian study of the prescribing practices of family physicians treating patients with atrial fibrillation showed that a substantial proportion stopped prescribing warfarin altogether after one of their patients suffered a haemorrhagic stroke, whereas physicians who did not routinely prescribe anticoagulants tended not to change their practice even when one or more of their patients suffered an thromboembolic stroke [ 37 ]. In this case, the negative consequences of electing to intervene (i.e. prescribing) had a greater impact on perception of risk than the negative consequences of electing not to intervene (i.e. not prescribing).

A risk is a calculated evaluation of the likelihood and impact of a hazard, based on objective assessments and measurements rather than subjective interpretation. For example, the same medical student, now a consultant intensivist, might be able to cite a personal log of their last 1000 central line insertions, quote literature reviews on the topic, and assert that the top three risks in their practice are, e.g. infection, pneumothorax and accidental arterial cannulation. This is what Klein [ 28 ] would call seeing the ‘choke points’—another feature of expertise—the ability to identify quickly where the material dangers are in a situation, what actions are more likely to lead to failure, and what actions better ensure success (‘leverage points’).

In light of this, the term ‘perception of risk’ should be approached with a little caution. In the absence of hard data, most of what clinicians call ‘risk assessments’ in day-to-day practice would in large part actually be ‘threat assessments’. Despite the subjective and potentially distorting nature of threat assessments, this is not necessarily a bad thing. Reliable data for a given risk situation often may not exist, let alone be to hand. Moreover, expert clinicians are often called upon to make decisions in urgent and complex situations, and their ‘threat assessments’ are usually better than a novice’s ‘risk assessments’. To understand why and when this might be true (and when it might not be) requires a deeper analysis.

5 Expert Decision-Making

Efficient and accurate decision-making is critical to patient safety—and it is important that the people responsible for making decisions that impact patient safety are as experienced and as expert as possible. Research on expert decision-making in complex, dynamic domains, often referred to as Naturalistic Decision Making (NDM: [ 27 , 38 ]), has demonstrated that the most important step in making a decision in these domains is to accurately assess the situation—identify the problem, formulate a diagnosis, evaluate the risks. Mosier and Fischer [ 39 ] refer to this as the front end of the decision-making process. Once the situation is known, the retrieval of a workable course of action, the back end of the process, is facilitated.

Expertise impacts the decision process in several specific ways. First, expert decision makers exhibit high levels of competence and knowledge within the domain, and have experienced a wide variety of situations, instances, and cases they can draw upon (e.g. [ 40 ]). This means that a current case will often have features that match an event from the expert’s repertoire, facilitating quick and accurate situation assessment. Second, experts see and process information differently than novices do. They can quickly identify critical cues—that is, the subset of information most critical to accurate situation assessment—and attend to or categorise them. This impacts their ability to develop situation awareness and to create an accurate mental model of the situation [ 41 ]. Experts are sensitive to changing values of information and can adapt their mental models to accommodate them [ 42 ]. They may use an iterative process, using feedback from the environment to adjust their actions and incorporate changes resulting from incremental decisions. In healthcare, for example, physicians often monitor results of a treatment to refine their diagnoses [ 43 ]. They also employ strategies to cope with dynamic situations—anticipating developments, prioritising tasks, and making contingency plans—and employ knowledge-based control to address conflicts or contradictions [ 39 , 44 ]. The NDM framework relies heavily on expertise and on intuitive rather than analytical processing, and capitalises on decision makers’ abilities to pattern match, to mentally simulate a course of action, and to use sense-making strategies to improve their understanding of a given situation.

5.1 Metacognition

Experts not only monitor the situation but also how they are thinking and whether it is appropriate for the situation at hand. They critique and correct their diagnosis until they arrive at a satisfactory mental model of the situation, or further processing is too costly [ 45 , 46 ]. They are able to shift strategies when faced with high uncertainty or unmet expectancies, taking an incremental approach or engaging in more analytical processes [ 47 , 48 ]. For example, expert surgeons perform many routine tasks automatically, but ‘slow down’ and engage in effortful processing in preparation for nonroutine events or in response to unexpected events [ 49 ].

Expertise also attunes the decision maker to affect that is in response to critical elements of the task context and that may have significance for their decisions. The affective reaction to a situation—particularly comfort or discomfort—may represent a knowledge-based informational cue for decision-making. For example, when a situation is not recognised as familiar, affective responses such as unease or discomfort (‘something’s not right’) can motivate the expert to engage in more information gathering, or more substantive sense-making processes. Dominguez [ 50 ], for instance, reported that physicians frequently refer to their comfort level while deciding on whether or not to continue with laparoscopic surgery. This function of affect is similar to the role of ‘hunches’ in split-second decision-making.

5.3 Communication and Decision-Making

All individuals involved in ensuring a patient’s safety must function collaboratively as a team. Because healthcare is a dynamic task environment, team members need to respond adaptively to changing conditions. Communication plays a pivotal role in this process [ 51 ], especially in healthcare as team members often perform sequentially and rely on information from the previous shift to guide their decisions and actions. Team members let others in on their reasoning and inform them about their intentions and expectations [ 52 ]. Critically, expert teams ensure common ground and shared mental models by providing feedback [ 53 ], and work to mitigate decision-making and other errors through team-centred communication [ 54 , 55 ].

5.4 Stress and Decision-Making

Stress related to the working conditions is defined by the World Health Organization as the response people may have when presented with work demands and pressures that are not matched to their knowledge and abilities, and which challenge their ability to cope. It occurs in a wide range of circumstances and may have a profound impact on decision-making which, in the medical context, could negatively affect clinical outcomes. Stress-related reductions in cognitive performance (e.g. accuracy, reaction time, attention, memory) resulted in poorer patient safety outcomes such as hospital acquired infections or medication errors [ 56 ].

It is therefore essential to address the causes of stress, which can be found both at the individual and at the organisational level. In the first case, it must be highlighted that medical practice has a solid rational basis made explicit through the clinical reasoning but, given the relationships doctors necessarily build with patients and other professionals, it also entails a strong emotional dimension that must be acknowledged [ 57 ]. Healthcare professionals experience emotions differently, quantitatively and qualitatively, and should be aware of their ‘emotional intelligence’ and trained on their ability to cope and react in case of stressful situations without stigmatisations [ 58 , 59 ].

In the second case, from a system perspective, stressful conditions in the work environment must be identified and possibly mitigated—if not removed—in terms of both contents (working hours, monotony, participation and control) and contexts (job insecurity, teamwork, organisational culture, work-life balance). Doctors are requested to take charge of greater responsibilities and demands, but resources are often limited resulting in risks of overload and burnout. Adequate staffing levels, human-capital investments, respect of working times and cultural changes in the medical organisations with a radical shift from competitiveness to collaboration and teamwork are therefore needed to reduce stress and its consequences [ 60 ].

6 Communication

‘Effective communication’ is recognised as a core non-technical skill [ 17 ], a means to provide knowledge, institute relationships, establish predictable behaviour patterns, and as a vital component for leadership and team coordination [ 61 , 62 ]. It is crucial for delivering high-quality healthcare and has been acknowledged together with effective teamwork as an essential component for patient safety [ 61 , 63 ]. ‘Communication failures’ have long been recognised as a leading cause of unintentional patient harm [ 64 ]. More recently a report of 2587 sentinel medical adverse events, reviewed by the US Joint Commission over a 3-year period, cited ‘communication’ as a contributing factor in over 68% of cases [ 65 ].

However, ‘communication’ is a very broad term; pinning down a practical definition is difficult. In the wider academic literature, communication has been classified according to at least seven distinct philosophical approaches [ 66 ], of which at least two are relevant to non-technical skills training in healthcare: the information engineering (‘cybernetic’) approach and the social construction (‘sociocultural’) approach [ 67 , 68 ]. The first defines communication as the linear transmission of ‘signal packages’ from a ‘transmitter’ to a ‘receiver’ through a medium. The latter emphasises how team communication can create the dynamic context in which people work, implying that communication, rather than a neutral mean, is the primary social process through which a meaningful shared world is built [ 67 ]. There is also the field of ‘semiotics’—the study of signals and the nature of ‘meaning’ itself across different populations, demographics and cultures. These varied perspectives underscore the sociotechnical nature of all healthcare communication.

For the purposes of developing workable patient safety tools (and mindful of this very narrow context), communication can be defined as the transfer of meaning from one person to another [ 69 ]. In teams comprising health professionals with different backgrounds, roles, training and perspectives on care, the main purpose of communication is to facilitate among team members a shared mental model of a situation: the context, the goals, the tasks, the methods to be used, who will do what, etc. (i.e. ‘team situation awareness’). Thus, it is important to recognise that ‘meaning’ is different to ‘information’ or ‘knowledge’, and effective communication therefore depends to some extent on the existing level of situation awareness of individual team members. For example, stating clearly that ‘the patient’s blood pressure is 80/50’ is not per se effective communication of its meaning if the person hearing it does not know that this finding usually represents critical hypotension in an adult.

While effective teamwork requires much more than communication (see below), specific failures in communication can hinder the process of building a shared understanding of the situation between team members, leading to poor performance and errors [ 70 ]. It follows that effective communication in healthcare teams can only be the result of dynamic iterative ‘two-way’ processes that lead to an ‘equilibrium of understanding’ among team members [ 69 ], and which can and must change with the input of new people and new information. Refining these processes can be seen as the basis for developing better ‘communication skills’.

6.1 Specific/Directed/Acknowledged Communication

For ensuring effective team communication two aspects have been highlighted as fundamental [ 71 ]: the sharing of unique information held by team members in face-to-face environments and openness of information in virtual environments [ 72 , 73 ]. To this one can add the implementation of closed-loop communication procedures that acknowledge the receipt of information and clarify any inconsistencies in information interpretation [ 74 ].

The concept of ‘specific/directed/acknowledged’ communication comes from simulation training [ 10 ]. ‘Specific’ refers to speaking clearly and the use of salient unambiguous descriptions, ideally using a ‘controlled vocabulary’ of terms with unique meanings as agreed by a discrete population of practitioners. An obvious example is the ‘military speak’ used in formal mission communications between soldiers, both in Hollywood movies and real life; however it should also be apparent that much of the diagnostic and therapeutic jargon used by clinicians, based mostly on Latin and Greek terminology, is already a form of controlled vocabulary. Specificity is also reflected in a number of other practical ways [ 69 ]:

Using the word ‘right’ only to mean chirality (as in ‘left’ or ‘right’) and avoiding its use to mean ‘Ok’ or ‘correct’ (as in ‘the left leg is the right leg for this operation, right?’)

Using numbers rather than vague terms where applicable (‘the systolic is 200’ rather than ‘the blood pressure’s high’, ‘I should be there in 10–20 min’ versus ‘I’ll be down soon’).

Using the ‘five rights’ convention for prescribing and administering medications: checking the correct drug in the correct dose via the correct route at the correct time for the correct patient [ 75 ]; a convention routinely taught to nurses but not so consistently to doctors.

Recognising and avoiding non-standard and ambiguous clinical abbreviations and acronyms [ 76 ].