Are peaceful protests more effective than violent ones?

- Search Search

As unrest erupts across the world after the killing of a Black man, George Floyd, by a white police officer, even some peaceful protests have descended into chaos, calling into question the efficacy of violence when it comes to spurring social change.

“There’s certainly more evidence that peaceful protests are more successful because they build a wider coalition,” says Gordana Rabrenovic , associate professor of sociology and director of the Brudnick Center on Violence and Conflict.

Gordana Rabrenovic is an associate professor of sociology and director of the Brudnick Center on Violence and Conflict. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

Who’s responsible for inciting this violence—the protesters or the police—is another debate entirely. But, Rabrenovic says, one thing is clear: in order for a movement to gain support and inspire lasting change, peace and consensus are essential.

“Violence can scare away your potential allies. You need the people on the sidelines to say, ‘This is my issue, too,’” she says. “For the people who say, ‘All lives matter,’ that’s true, but not all lives are in danger. You need to convince them.”

Still, it’s not always easy, or even feasible, for groups of oppressed people to take this moral high road, Rabrenovic says.

“The system doesn’t work for them,” she says. “They may think the only way to deal with the system is to destroy it.”

Black people in the U.S. are not only three times more likely to be killed by police than white people, but they’re also less likely to be armed than white people during these interactions with police.

For Black people who experience violence at the hands of the people and institutions that are supposed to protect them, the question becomes: “If they use violence, why shouldn’t we use violence?” Rabrenovic says. “They know that violence works, otherwise they wouldn’t use it.”

Exactly how that violence manifests is another matter entirely, but, Rabrenovic says, one thing is almost always true: violence is the spark that ignites the movement.

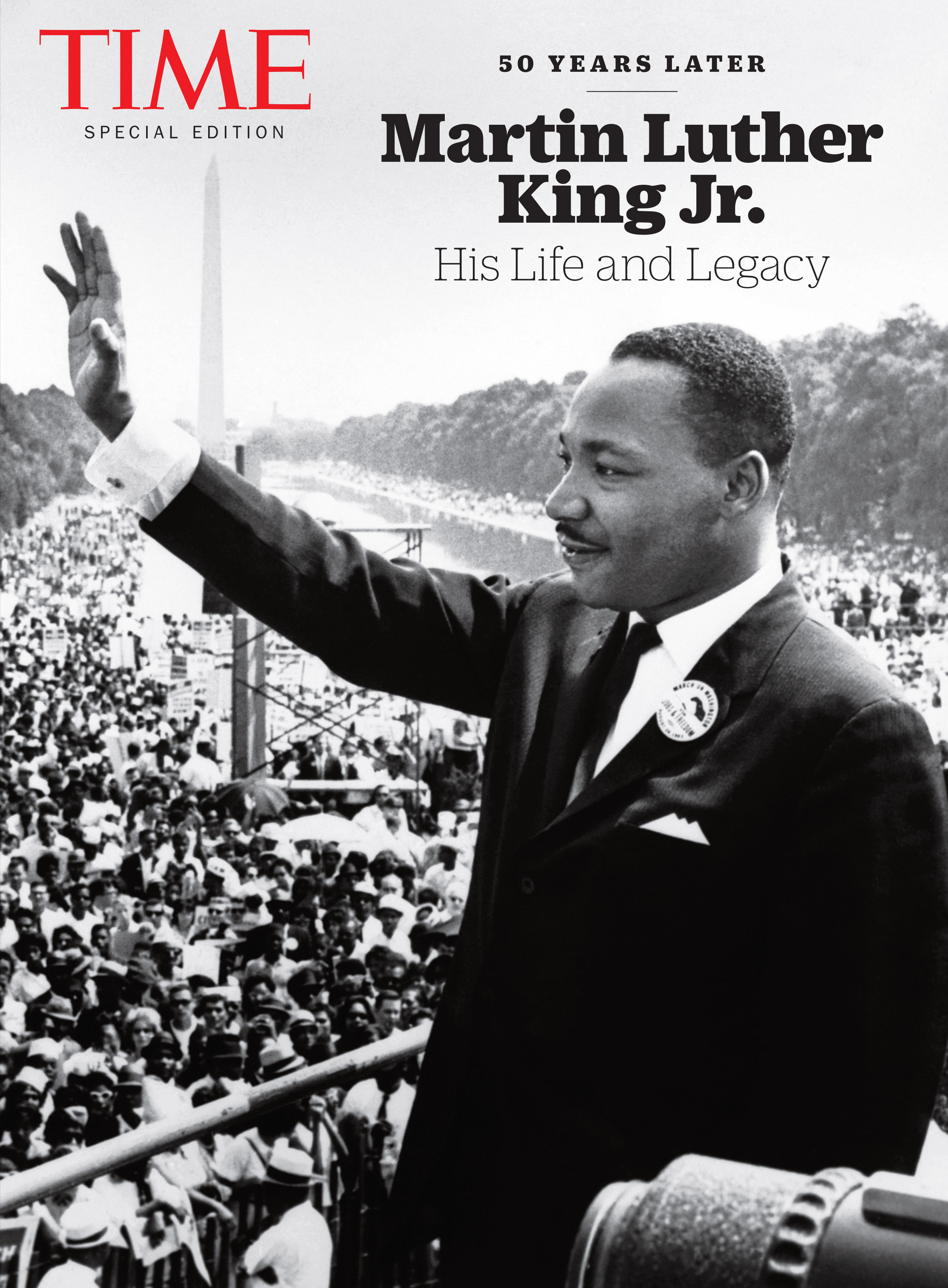

The civil rights movement of the 1960s is one example. The overall ethos of Martin Luther King Jr.’s movement was peace. But the catalyst was violence—hundreds of years of lynchings, lawful inequality, and oppression.

In fact, peace was strategically used during the civil rights movement to emphasize the violence Black people in the U.S. endured. Protesters were intentionally peaceful to prevent any question of who started the violence and whether it was justified. The results were inarguable visuals of peaceful Black protesters being attacked by dogs and beaten by police.

“Even peaceful civil rights movements are violent because it’s violence that motivates people to take action,” Rabrenovic says. Translating a violent history into a peaceful future is the hard part.

“Violence might be the quickest way to achieve your goals, but in order to sustain your victory, you would need to use coercion and have some kind of apparatus in place that keeps people in constant fear of punishment,” she says. “And nobody wants to live like that.”

While the George Floyd protests are a good starting point, the protests alone aren’t enough to sustain an entire movement, Rabrenovic says. “We need to give people other tools.”

Voting is one example. “We need to vote,” she says. “The government is us.”

One could argue that for Black and other disenfranchised people in the U.S., voting seems futile . But Rabrenovic counters, “If voting didn’t work, there wouldn’t be voter suppression.”

“You can’t suppress everyone,” she says. “That’s why it’s important to build a wide coalition, to bring in as many people as you can.”

We can’t keep living with only ourselves in mind. We need each other, she says. And protests are only the beginning.

For media inquiries , please contact [email protected] .

Editor's Picks

Shotspotter improves detection and response to gunfire, but doesn’t reduce crime, northeastern research finds, you may have heard of his boston hot spots, but this restaurateur’s menu includes a finance degree from northeastern, desert locusts’ jaws sharpen themselves, northeastern materials scientist discovers, from the operating room to pediatrics, northeastern co-op says work in spanish medical clinic cemented his career goal, british prime minister rishi sunak has gambled the house on a july election. northeastern experts explain what might be behind his thinking, featured stories, .ngn-magazine__shapes {fill: var(--wp--custom--color--emphasize, #000) } .ngn-magazine__arrow {fill: var(--wp--custom--color--accent, #cf2b28) } ngn magazine fiona howard’s body was collapsing. now she’s a world-ranked dressage rider aiming for the paris paralympics, .ngn-magazine__shapes {fill: var(--wp--custom--color--emphasize, #000) } .ngn-magazine__arrow {fill: var(--wp--custom--color--accent, #cf2b28) } ngn magazine why james corden is looking to use tax breaks to build on barbie’s success and woo more hollywood filming to britain, extremist communities continue to rely on youtube for hosting, but most videos are viewed off-site, northeastern research finds, can scarlett johansson sue openai over its voice assistant northeastern intellectual property law experts weigh in.

Recent Stories

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Footnote leads to exploration of start of for-profit prisons in N.Y.

Should NATO step up role in Russia-Ukraine war?

It’s on Facebook, and it’s complicated

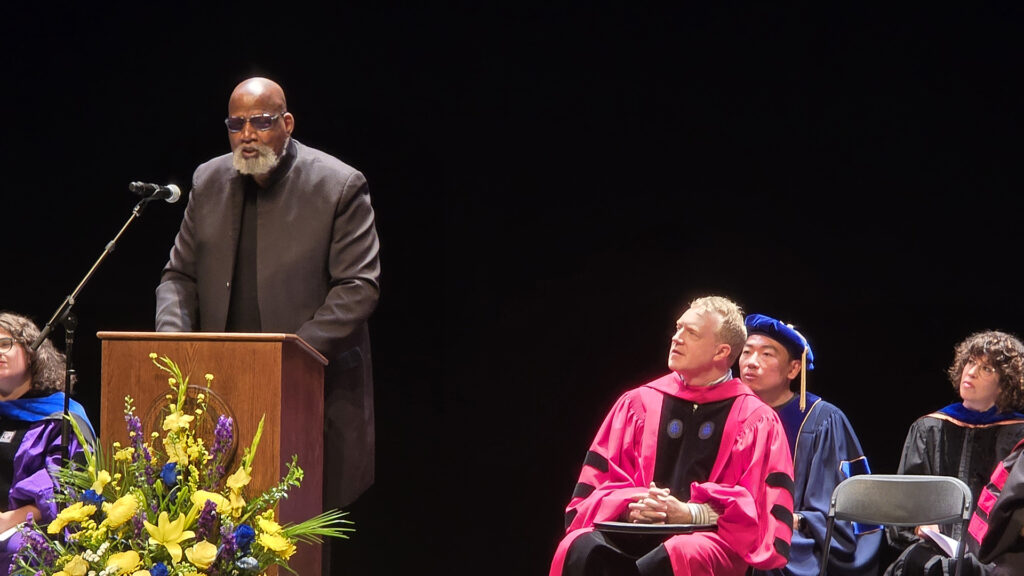

In her book, “Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict,” Harvard Professor Erica Chenoweth explains why civil resistance campaigns attract more absolute numbers of people.

Photo by Hossam el-Hamalawy

Nonviolent resistance proves potent weapon

Michelle Nicholasen

Weatherhead Center Communications

Erica Chenoweth discovers it is more successful in effecting change than violent campaigns

Recent research suggests that nonviolent civil resistance is far more successful in creating broad-based change than violent campaigns are, a somewhat surprising finding with a story behind it.

When Erica Chenoweth started her predoctoral fellowship at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs in 2006, she believed in the strategic logic of armed resistance. She had studied terrorism, civil war, and major revolutions — Russian, French, Algerian, and American — and suspected that only violent force had achieved major social and political change. But then a workshop led her to consider proving that violent resistance was more successful than the nonviolent kind. Since the question had never been addressed systematically, she and colleague Maria J. Stephan began a research project.

For the next two years, Chenoweth and Stephan collected data on all violent and nonviolent campaigns from 1900 to 2006 that resulted in the overthrow of a government or in territorial liberation. They created a data set of 323 mass actions. Chenoweth analyzed nearly 160 variables related to success criteria, participant categories, state capacity, and more. The results turned her earlier paradigm on its head — in the aggregate, nonviolent civil resistance was far more effective in producing change.

The Weatherhead Center for International Affairs (WCFIA) sat down with Chenoweth, a new faculty associate who returned to the Harvard Kennedy School this year as professor of public policy, and asked her to explain her findings and share her goals for future research. Chenoweth is also the Susan S. and Kenneth L. Wallach Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

Erica Chenoweth

WCFIA: In your co-authored book, “ Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict ,” you explain clearly why civil resistance campaigns attract more absolute numbers of people — in part it’s because there’s a much lower barrier to participation compared with picking up a weapon. Based on the cases you have studied, what are the key elements necessary for a successful nonviolent campaign?

CHENOWETH: I think it really boils down to four different things. The first is a large and diverse participation that’s sustained.

The second thing is that [the movement] needs to elicit loyalty shifts among security forces in particular, but also other elites. Security forces are important because they ultimately are the agents of repression, and their actions largely decide how violent the confrontation with — and reaction to — the nonviolent campaign is going to be in the end. But there are other security elites, economic and business elites, state media. There are lots of different pillars that support the status quo, and if they can be disrupted or coerced into noncooperation, then that’s a decisive factor.

The third thing is that the campaigns need to be able to have more than just protests; there needs to be a lot of variation in the methods they use.

The fourth thing is that when campaigns are repressed — which is basically inevitable for those calling for major changes — they don’t either descend into chaos or opt for using violence themselves. If campaigns allow their repression to throw the movement into total disarray or they use it as a pretext to militarize their campaign, then they’re essentially co-signing what the regime wants — for the resisters to play on its own playing field. And they’re probably going to get totally crushed.

In 2006, Erica Chenoweth believed in the strategic logic of armed resistance. Then she was challenged to prove it.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

WCFIA: Is there any way to resist or protest without making yourself more vulnerable?

CHENOWETH: People have done things like bang pots and pans or go on electricity strikes or something otherwise disruptive that imposes costs on the regime even while people aren’t outside. Staying inside for an extended period equates to a general strike. Even limited strikes are very effective. There were limited and general strikes in Tunisia and Egypt during their uprisings and they were critical.

WCFIA: A general strike seems like a personally costly way to protest, especially if you just stop working or stop buying things. Why are they effective?

CHENOWETH: This is why preparation is so essential. Where campaigns have used strikes or economic noncooperation successfully, they’ve often spent months preparing by stockpiling food, coming up with strike funds, or finding ways to engage in community mutual aid while the strike is underway. One good example of that comes from South Africa. The anti-apartheid movement organized a total boycott of white businesses, which meant that black community members were still going to work and getting a paycheck from white businesses but were not buying their products. Several months of that and the white business elites were in total crisis. They demanded that the apartheid government do something to alleviate the economic strain. With the rise of the reformist Frederik Willem de Klerk within the ruling party, South African leader P.W. Botha resigned. De Klerk was installed as president in 1989, leading to negotiations with the African National Congress [ANC] and then to free elections, where the ANC won overwhelmingly. The reason I bring the case up is because organizers in the black townships had to prepare for the long term by making sure that there were plenty of food and necessities internally to get people by, and that there were provisions for things like Christmas gifts and holidays.

WCFIA: How important is the overall number of participants in a nonviolent campaign?

CHENOWETH: One of the things that isn’t in our book, but that I analyzed later and presented in a TEDx Boulder talk in 2013 , is that a surprisingly small proportion of the population guarantees a successful campaign: just 3.5 percent. That sounds like a really small number, but in absolute terms it’s really an impressive number of people. In the U.S., it would be around 11.5 million people today. Could you imagine if 11.5 million people — that’s about three times the size of the 2017 Women’s March — were doing something like mass noncooperation in a sustained way for nine to 18 months? Things would be totally different in this country.

“Countries in which there were nonviolent campaigns were about 10 times likelier to transition to democracies within a five-year period compared to countries in which there were violent campaigns — whether the campaigns succeeded or failed.” Erica Chenoweth

WCFIA: Is there anything about our current time that dictates the need for a change in tactics?

CHENOWETH: Mobilizing without a long-term strategy or plan seems to be happening a lot right now, and that’s not what’s worked in the past. However, there’s nothing about the age we’re in that undermines the basic principles of success. I don’t think that the factors that influence success or failure are fundamentally different. Part of the reason I say that is because they’re basically the same things we observed when Gandhi was organizing in India as we do today. There are just some characteristics of our age that complicate things a bit.

WCFIA: You make the surprising claim that even when they fail, civil resistance campaigns often lead to longer-term reforms than violent campaigns do. How does that work?

CHENOWETH: The finding is that civil resistance campaigns often lead to longer-term reforms and changes that bring about democratization compared with violent campaigns. Countries in which there were nonviolent campaigns were about 10 times likelier to transition to democracies within a five-year period compared to countries in which there were violent campaigns — whether the campaigns succeeded or failed. This is because even though they “failed” in the short term, the nonviolent campaigns tended to empower moderates or reformers within the ruling elites who gradually began to initiate changes and liberalize the polity.

One of the best examples of this is the Kefaya movement in the early 2000s in Egypt. Although it failed in the short term, the experiences of different activists during that movement surely informed the ability to effectively organize during the 2011 uprisings in Egypt. Another example is the 2007 Saffron Revolution in Myanmar, which was brutally suppressed at the time but which ultimately led to voluntary democratic reforms by the government by 2012. Of course, this doesn’t mean that nonviolent campaigns always lead to democracies — or even that democracy is a cure-all for political strife. As we know, in Myanmar, relative democratization in the country’s institutions has been accompanied by extreme violence against the Rohingya community there. But it’s important to note that such cases are the exceptions rather than the norm. And democratization processes tend to be much bumpier when they occur after large-scale armed conflict instead of civil resistance campaigns, as was the case in Myanmar.

WCFIA: What are your current projects?

CHENOWETH: I’m still collecting data on nonviolent campaigns around the world. And I’m also collecting data on the nonviolent actions that are happening every day in the United States through a project called the Crowd Counting Consortium , with Jeremy Pressman of the University of Connecticut. It began in 2017, when Jeremy and I were collecting data during the Women’s March. Someone tweeted a link to our spreadsheet, and then we got tons of emails overnight from people writing in to say, “Oh, your number in Portland is too low; our protest hasn’t made the newspapers yet, but we had this many people.” There were the most incredible appeals. There was a nursing home in Encinitas, Calif., where 50 octogenarians organized an indoor women’s march with their granddaughters. Their local news had shot a video of them and they asked to be counted, and we put them in the sheet. People are very active and it’s not part of the broader public discourse about where we are as a country. I think it’s important to tell that story.

This originally appeared on the Weatherhead Center website . Part two of the series is now online.

The artwork, “Love and Revolution,” revolutionary graffiti at Saleh Selim Street on the island of Zamalek, Cairo, was photographed by Hossam el-Hamalawy on Oct. 23, 2011.

Share this article

You might like.

Historian traces 19th-century murder case that brought together historical figures, helped shape American thinking on race, violence, incarceration

National security analysts outline stakes ahead of July summit

‘Spermworld’ documentary examines motivations of prospective parents, volunteer donors who connect through private group page

Six receive honorary degrees

Harvard recognizes educator, conductor, theoretical physicist, advocate for elderly, writer, and Nobel laureate

Everything counts!

New study finds step-count and time are equally valid in reducing health risks

Five alumni elected to the Board of Overseers

Six others join Alumni Association board

Nonviolence

As a theologian, Martin Luther King reflected often on his understanding of nonviolence. He described his own “pilgrimage to nonviolence” in his first book, Stride Toward Freedom , and in subsequent books and articles. “True pacifism,” or “nonviolent resistance,” King wrote, is “a courageous confrontation of evil by the power of love” (King, Stride , 80). Both “morally and practically” committed to nonviolence, King believed that “the Christian doctrine of love operating through the Gandhian method of nonviolence was one of the most potent weapons available to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom” (King, Stride , 79; Papers 5:422 ).

King was first introduced to the concept of nonviolence when he read Henry David Thoreau’s Essay on Civil Disobedience as a freshman at Morehouse College . Having grown up in Atlanta and witnessed segregation and racism every day, King was “fascinated by the idea of refusing to cooperate with an evil system” (King, Stride , 73).

In 1950, as a student at Crozer Theological Seminary , King heard a talk by Dr. Mordecai Johnson , president of Howard University. Dr. Johnson, who had recently traveled to India , spoke about the life and teachings of Mohandas K. Gandhi . Gandhi, King later wrote, was the first person to transform Christian love into a powerful force for social change. Gandhi’s stress on love and nonviolence gave King “the method for social reform that I had been seeking” (King, Stride , 79).

While intellectually committed to nonviolence, King did not experience the power of nonviolent direct action first-hand until the start of the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955. During the boycott, King personally enacted Gandhian principles. With guidance from black pacifist Bayard Rustin and Glenn Smiley of the Fellowship of Reconciliation , King eventually decided not to use armed bodyguards despite threats on his life, and reacted to violent experiences, such as the bombing of his home, with compassion. Through the practical experience of leading nonviolent protest, King came to understand how nonviolence could become a way of life, applicable to all situations. King called the principle of nonviolent resistance the “guiding light of our movement. Christ furnished the spirit and motivation while Gandhi furnished the method” ( Papers 5:423 ).

King’s notion of nonviolence had six key principles. First, one can resist evil without resorting to violence. Second, nonviolence seeks to win the “friendship and understanding” of the opponent, not to humiliate him (King, Stride , 84). Third, evil itself, not the people committing evil acts, should be opposed. Fourth, those committed to nonviolence must be willing to suffer without retaliation as suffering itself can be redemptive. Fifth, nonviolent resistance avoids “external physical violence” and “internal violence of spirit” as well: “The nonviolent resister not only refuses to shoot his opponent but he also refuses to hate him” (King, Stride , 85). The resister should be motivated by love in the sense of the Greek word agape , which means “understanding,” or “redeeming good will for all men” (King, Stride , 86). The sixth principle is that the nonviolent resister must have a “deep faith in the future,” stemming from the conviction that “The universe is on the side of justice” (King, Stride , 88).

During the years after the bus boycott, King grew increasingly committed to nonviolence. An India trip in 1959 helped him connect more intimately with Gandhi’s legacy. King began to advocate nonviolence not just in a national sphere, but internationally as well: “the potential destructiveness of modern weapons” convinced King that “the choice today is no longer between violence and nonviolence. It is either nonviolence or nonexistence” ( Papers 5:424 ).

After Black Power advocates such as Stokely Carmichael began to reject nonviolence, King lamented that some African Americans had lost hope, and reaffirmed his own commitment to nonviolence: “Occasionally in life one develops a conviction so precious and meaningful that he will stand on it till the end. This is what I have found in nonviolence” (King, Where , 63–64). He wrote in his 1967 book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? : “We maintained the hope while transforming the hate of traditional revolutions into positive nonviolent power. As long as the hope was fulfilled there was little questioning of nonviolence. But when the hopes were blasted, when people came to see that in spite of progress their conditions were still insufferable … despair began to set in” (King, Where , 45). Arguing that violent revolution was impractical in the context of a multiracial society, he concluded: “Darkness cannot drive out darkness: only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate: only love can do that. The beauty of nonviolence is that in its own way and in its own time it seeks to break the chain reaction of evil” (King, Where , 62–63).

King, “Pilgrimage to Nonviolence,” 13 April 1960, in Papers 5:419–425 .

King, Stride Toward Freedom , 1958.

King, Where Do We Go from Here , 1967.

- Subscribe to BBC Science Focus Magazine

- Previous Issues

- Future tech

- Everyday science

- Planet Earth

- Newsletters

Peaceful protests: Are non-violent demonstrations an effective way to achieve change?

From Extinction Rebellion to anti-government protests, many demonstrations rely on peaceful tactics to achieve their goals. But are nonviolent campaigns the best way to raise public awareness of a cause?

In August 2018, 15-year-old Greta Thunberg sat in front of the Swedish parliament building to protest for greater action on the climate crisis. She wanted the government to pledge to reduce carbon emissions.

A month later, on the day before the Swedish general election, Greta announced that she would continue to strike every Friday until the country’s policy changed. Her slogan was FridaysForFuture, which went on to represent the global school’s strike for climate.

Read more about protesting:

- Take a trip back to 1970 when Earth Day was first held

- Dean Burnett: You could forgive a teenager for looking at the wider adult world, and saying 'it’s really up to us now'

Now, a year later, students and adults around the world have joined strikes for FridaysForFuture , as well as the UK-based organisation Extinction Rebellion . XR, as they’re widely known, began around the same time as Greta’s first strikes, and are a group of nonviolent protesters who want to communicate, and stop, the threat of mass extinction by climate change.

XR’s first act of civil disobedience was in October 2018, when a crowd of 1,500 gathered in Parliament Square. In the following weeks, they blocked bridges and glued themselves to the gates of Buckingham Palace. Through the disruption, they wanted to bring attention to the climate emergency.

In the 12 months since that first protest, the movement has grown to see 150,000 people on the XR mailing list. There are 156 different countries with at least one XR rebel, with groups in Australia, the USA and Ghana, to name just a few.

Roger Hallam, one of the XR founders, claims to have been inspired by the 2011 book Why Civil Resistance Works . The book’s co-authors, Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan, collected and analysed data on over 300 violent and nonviolent major political campaigns in the last decade.

They found that nonviolent campaigns had been twice as effective as the violent campaigns: they succeeded about 53 per cent of time compared to 25 per cent for an armed resistance. This success of civil resistance is the backbone of the XR movement – any action attributed to the organisation must be nonviolent, and being arrested is not a requirement of getting involved.

Stephan is now a director of the Program on Nonviolent Action at the US Institute of Peace. She notes that a campaign cannot just be a one-off protest, it has to be a sustained sequence of actions – not just protests – to have any chance at success.

“Some of the most powerful tactics in nonviolent resistance can be refusing to buy products or ‘stay at homes’ – non-cooperation with the status quo,” says Stephan. “We don’t claim that nonviolent resistance always works,” she stresses. But both in terms of immediate and longer-term impacts, nonviolent resistance seemed to produce more positive and beneficial results.

A democracy initiated by a nonviolent movement was less likely to fall back into civil war, for example. In the 2011 Arab Spring, several countries had anti-government protests. Nonviolent street demonstrations in one of these countries, Tunisia, led to the overthrowing of the president and eventually democratisation of the country.

Read more about climate change:

- Can planting billions of trees help tackle climate change?

- Do we really know what climate change will do to our planet?

Stephan’s co-author Erica Chenoweth took their research further and found that no regime or incumbent leader had remained in power when at least 3.5 per cent of the population had participated in active protest . That’s not to say success is guaranteed when a movement attracts 3.5 per cent of a population. “Of course, it’s sustained participation over time, keeping people actively involved, that’s needed,” explains Stephan.

So how does a campaign attract people and then keep them engaged?

Psychologist David Halpern , director of government partner The Behavioural Insights Team, likens the dissemination of an idea to the adoption of an innovation, or piece of new technology.

The same way mobile phones have spread from an elite few to become a part of everyone’s daily lives, the uptake of an idea within society follows a set pattern. The pattern was suggested by Everett M. Rogers in his book Diffusion of Innovations .

- Subscribe to the Science Focus Podcast on these services: Acast , iTunes , Stitcher , RSS , Overcast

First, there are innovators, the ones who champion something from day one. These then influence ‘early adopters’, people who are “considered by many to be ‘the individual to check with’ before adopting a new idea,” writes Rogers. These in turn influence the majority, then finally, the ‘laggards’ – “those who tend to be suspicious of innovations and of change agents.”

Greta Thunberg is an example of an innovator, says Halpern. “She personifies a lot of this.She’s persistent and authentic. One of the things that undermines a message is if you yourself are not consistent. Then people will just view you as hypocritical. She embodies it.”

Key to the adoption of an idea is the ability to recruit past the innovators and early adopters. “The protests that grow to scale are able to recruit people. And if you get that wrong, you won’t get your early majority assembled,” says Halpern.

In the climate movement, it’s the younger generation who are the early adopters. “Teenagers are almost wired to be contrary, to be a bit rebellious,” notes Halpern. “They are able to recruit and persuade the more reluctant older folks.”

Elements of a protest can dissuade people on the fence from joining a movement, though. “We’re built to absorb information which supports our prior beliefs,” explains Halpern.

This means that if you were sceptical about climate change and were then met with angry protestors blocking your route to work, you’ll ‘asymmetrically absorb’ this information and it’ll give you an excuse not to adopt.

Read more from Reality Check:

- The Amazon rainforest: could it become a desert?

- Carbon offsetting: a solution to flying emissions, or just passing the buck?

- Has Blue Planet II had an impact on plastic pollution?

But not everyone has to be completely on board for a movement to work. The early adopters just need to influence the majority enough.

“[The majority] might not be thinking ‘I’m prepared to go to extraordinary lengths to change my lifestyle’ but they create a critical mass such that you get adoption of electric vehicles, smart meters, etc,” says Halpern.

With the number of people joining both XR and FridaysForFuture growing, what can we expect to see next?

In Stephan and Chenoweth’s research for Why Civil Resistance Works, they found that the average time for a nonviolent campaign to achieve its goals was three years.

“Three years was for maximalist campaigns with major political goals, which is not to say the climate movement will take any shorter or longer, but there are different variables and different mechanisms of change,” explains Stephan.

“It’s hard to put a timeline on it. But scientists demonstrate that time is running out [for climate action].”

Stephan and Chenoweth found that the average duration for violent campaigns was three times that of nonviolent. “Oftentimes people will say ‘nonviolence isn’t working, we need to take up arms to win more quickly!’ but there’s not a lot of evidence that that is the case.”

Stephan says she has friends and colleagues who are involved with the protests and will probably show up herself for some of the Washington, D.C. portion of the strikes.

“Certainly, the youth face [of the movement] is really powerful,” she says. “It’s gotten lots of new and different people involved and actively engaged in what is probably the most pressing issue certainly of my generation.”

- This article was first published on 27 September 2019

Visit the BBC's Reality Check website at bit.ly/reality_check_ or follow them on Twitter @BBCRealityCheck

Follow Science Focus on Twitter , Facebook , Instagram and Flipboard

Share this article

Science journalist and author

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookies policy

- Code of conduct

- Magazine subscriptions

- Manage preferences

Martin Luther King and Gandhi Weren’t the Only Ones Inspired By Thoreau’s ‘Civil Disobedience’

Thoreau’s essay became a cornerstone of 20th-century protest

Kat Eschner

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3d/40/3d40e9b0-f8f1-4f1c-8aaa-65669306345f/civil-wr.jpg)

Henry David Thoreau was born on this day 200 years ago. A few decades later, aged 32, he wrote an essay that fundamentally influenced twentieth-century protest.

"Civil Disobedience," originally titled "Resistance to Civil Government," was written after Thoreau spent a night in the unsavory confines of the Concord, Massachusetts jail–an activity likely to inspire anyone to civil disobedience. The cause of his incarceration was something which the philosopher found to be equally galling: he hadn’t paid his poll tax , a regular tax that everyone had to pay, in six years.

But Thoreau wasn’t just shirking. “He withheld the tax to protest the existence of slavery and what he saw as an imperialistic war with Mexico,” writes the Library of Congress. He was released when a relative paid the tax for him, and went on to write the eminently quotable essay that included the line “Under a government which imprisons any unjustly, the true place for a just man is also a prison.”

While another line in the essay–"I heartily accept the motto, ‘That government is best which governs least’”–is also well known, it was his line of thinking about justice, when he argued that conscience can be a higher authority than government, that stuck with civil-rights leaders Martin Luther King and Mohandas Gandhi.

“Thoreau was the first American to define and use civil disobedience as a means of protest,” Brent Powell wrote for the magazine of the Organization of American Historians. He began the tradition of non-violent protest that King is best known for continuing domestically. But there was an intermediary in their contact: Gandhi, who said that Thoreau’s ideas “greatly influenced” his ideas about protest.

But it wasn’t just these famous figures who rallied around Thoreau’s battle cry, writes Thoreau Society member Richard Lenat: the essay “ has more history than many suspect,” he writes.

Thoreau’s ideas about civil disobedience were first spread in the late 1900s by Henry Salt, an English social reformer who introduced them to Gandhi . And Russian author Leo Tolstoy was important to spreading those ideas in continental Europe, wrote literature scholar Walter Harding.

“During World War II, many of the anti-Nazi resisters, particularly in Denmark, adopted Thoreau’s essay as a manual of arms and used it very effectively,” he writes.

In America, anarchists like Emma Goldman used Thoreau’s tactics to oppose the World War I draft, he writes, and those tactics were used again by World War II-era pacificists. But it wasn’t until King came along that the essay became truly prominent in the U.S., Harding wrote. Vietnam War protestors also came to use its ideas, and others.

Despite this later global influence, writes Harding, Thoreau was “ignored in his own lifetime.” It’s not even known exactly who paid his taxes for him, wrote scholar Barbara L. Packer. In an interview 50 years after the incident, the writer’s jailer recalled that he had just reached home for the evening when a messenger told him that a woman, wearing a veil, had appeared with “Mr. Thoreau’s tax.”

“Unwilling to go to the trouble of unlocking the prisoners he had just locked up, [the jailer] waited till morning to release Thoreau–who, he remembered, was ‘mad as the devil when I turned him loose,'” Packer wrote.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

Kat Eschner | | READ MORE

Kat Eschner is a freelance science and culture journalist based in Toronto.

Why Martin Luther King Jr.’s Lessons About Peaceful Protests Are Still Relevant

The following feature is excerpted from TIME Martin Luther King, Jr.: His Life and Legacy , available at retailers and at the Time Shop

Revolutions tend to be measured in blood. From Lexington and the Bastille to the streets of Algiers, the toll on a repressed people seeking freedom is steep. But what does it take for a people to absorb degrading insults, physical attack and political repression in hopes that their oppressors will see the error in their ways? For Martin Luther King Jr. , it was a dream.

Over the course of a decade, King became synonymous with nonviolent direct action as he worked to overturn systemic segregation and racism across the southern United States. The civil rights movement formed the guidebook for a new era of protest. Whether it be responding to wars or protesting an unpopular administration at home, or the “color revolutions” across Europe and elsewhere overseas, the legacy of moral victory begetting actual change has been borne out time and again. The movement’s enduring influence is a far cry from its humble beginnings.

In March 1956, 90 defendants stood in wait in an aging Greek-revival courthouse in Montgomery, Ala. They faced the same charge: an obscure, decades-old anti-union law making it a misdemeanor to plot to interfere with a company’s business “without a just cause or legal excuse.” Their offense? Boycotting the city’s buses.

Step Into History: Learn how to experience the 1963 March on Washington in virtual reality

Young, old and from all walks of life—24 were clergymen—what united them was their dark skin and their act of quiet rebellion. First to face the judge was Martin Luther King Jr., 27, the youthful pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery. Almost four months earlier, a black seamstress named Rosa Parks had sparked a boycott of the city’s privately owned bus services after she was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white patron. Within days, the Montgomery Improvement Association was formed to organize private carpools to compete with the buses. King, who had moved to the city only two years earlier, was quickly elected its leader.

For 381 days, thousands of black residents trudged through chilling rain and oppressive heat, ignoring buses as they passed by. They endured death threats, violence and legal prosecution. King’s home was bombed. But instead of responding in kind, the members of the movement took to the pews, praying and rallying in churches in protest of the discrimination they suffered. In the courthouse, 31 testified to the harassment they endured on the city’s segregated buses, not so much a legal strategy as a moral one. Unsurprisingly in a city whose white–supremacist “White Citizens’ Council” membership skyrocketed after the boycott, King was found guilty and jailed for two weeks. As he said later, “It was the crime of joining my people in a non-violent protest against injustice.”

The boycott ended on Dec. 20, 1956, after the Supreme Court ruled that the racial segregation of buses was unconstitutional. But the enduring victory of Montgomery belonged not to the lawyers but to King and his fellow pastors—and the tens of thousands who followed them. Their protest shone a spotlight on the absurd lengths (enforcing an arcane and rarely invoked law) to which an entrenched power would go to protect a system designed to rob citizens of their worth solely because of their skin color.

“The strong man is the man who will not hit back, who can stand up for his rights and yet not hit back,” King told thousands of Montgomery Improvement Association supporters at the city’s Holt Street Baptist Church on Nov. 14, 1956. The black citizens of Montgomery would demonstrate their humanity while victims of a broken society. Nonviolence was the “testing point” of the burgeoning civil rights movement, King explained. “If we as Negroes succumb to the temptation of using violence in our struggle, unborn generations will be the recipients of a long and bitter night of—a long and desolate night of bitterness. And our only legacy to the future will be an endless reign of meaningless chaos.”

King had made the plight of the nation’s oppressed black citizens too plain to ignore, and it was a sharp blow to the “Christian conscience” of the white South. “They’ve become tortured souls,” Baptist minister William Finlator of Raleigh, N.C., told TIME then of his colleagues. “King has been working on the guilt conscience of the South. If he can bring us to contrition, that is our hope.”

Read more: John Lewis: Why Getting Into Trouble Is Necessary to Make Change

King became the symbol of nonviolent protest that had come to the fore in Montgomery. Inundated with speaking requests and interviews, and beset by threats of violence, King become a national celebrity both for what he accomplished and how. “Our use of passive resistance in Montgomery,” King told TIME, “is not based on resistance to get rights for ourselves, but to achieve friendship with the men who are denying us our rights, and change them through friendship and a bond of Christian understanding before God.”

On Jan. 10, 1957, weeks after black residents returned to unsegregated buses in the Alabama capital, King convened a gathering at the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, the church where his father preached and that he would later lead. He invited influential civil rights activists, like strategist Bayard Rustin and organizer Ella Baker, and prominent black ministers from across the South to discuss how to expand the nonviolent resistance movement. After weeks of discussions, they formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), a confederation of civil rights groups across the South, with King at the helm, that would go on to spread his philosophy.

Central to the SCLC’s mission was the notion that the Montgomery model could be replicated across the segregated South, to strike a blow against the entire Jim Crow system, which entrenched racial division in law and practice. But it wasn’t an easy sell. As the SCLC worked to recruit black churches and ministers, the organization faced real concerns of retaliation—both physical and economic—against those who signed on. Some doubted the method of nonviolent protest, believing the courts would eventually provide for integration. Others, especially younger groups, called for more-aggressive efforts.

But by 1960, nonviolent protests were sweeping across the South. In just one week in April, hundreds of black students were arrested as young people sat in and picketed segregated stores and diners from Nashville, Tenn., to Greensboro, N.C. Yet progress was painfully slow. In Savannah, Ga., the white mayor, Lee Mingledorff, demanded that the city council outlaw unlicensed picketing. “I don’t especially care if it’s constitutional or not,” he said. There were even more arrests, but the protests tired before achieving change.

The following year’s efforts were hardly more effective. A summer of Freedom Rides —in which black and white activists would jointly challenge segregation on buses—resulted in thousands of arrests and dozens of incidents of violence against demonstrators. But Jim Crow held. Groups consisting of younger and more impatient activists, like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Congress of Racial Equality, shifted strategy, borrowing the lessons of Montgomery. In late 1961, the SNCC and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People targeted the heavily segregated city of Albany, Ga., with boycotts and sit-ins. The SCLC and King joined the effort, and in July 1962 King was jailed.

Days later, King was quietly bailed out and ejected from prison by Albany police chief Laurie Pritchett, who had studied the nonviolence protest method and released King to undermine it. In other cities, violence by police against peaceful demonstrators brought outcry and sympathy. But Pritchett met nonviolence with nonviolence. Within weeks, the protest fizzled out. For King, Albany was largely a failure, and his takeaway was for the movement to better pick its spots.

That place was Birmingham, Ala., “probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States,” King would say. Racially motivated bombings against blacks had earned the city the nickname “Bombingham,” and many of its majority-black residents were denied all but the most menial jobs—if they could find work at all. Unlike in Albany, where the goal had been to desegregate the city, in Birmingham King focused on the downtown shopping district. And unlike in Albany, he had a foil of the first degree: Birmingham’s commissioner of public safety, Eugene “Bull” Connor. Connor told TIME in 1963 that the city “ain’t gonna segregate no niggers and whites together in this town.”

The tactics changed too. While there were sit-ins and kneel-ins and demonstrations, the SCLC also encouraged an economic boycott of the city. Birmingham’s economic heart, its shopping district, was crippled when black residents refused to shop in segregated stores. Boycott organizers patrolled the streets to shame black residents into toeing the line. The protests were designed to force a crisis point, and Connor only aided the effort. When business took down “Whites Only” signs, the avowed racist threatened to pull their licenses. On Good Friday, King was jailed for his 13th time for more than a week. Using the margins of scrap paper smuggled into his cell, King drafted his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” among the clearest representations of his philosophy.

“Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue,” King wrote. “It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored.”

Children provided the movement with some of its most powerful images, and the SCLC and King encouraged students to skip school to join sit-ins and marches. On May 2, the Children’s Crusade saw the arrest of hundreds of students in Birmingham, some under the age of 10, who sang and prayed as they awaited arrest. The New York Times compared the scene to a “school picnic” as they were transported to the city’s jail by every available city vehicle. Within hours, the prison was at capacity, filled with hundreds of school-age children.

Unbowed, Connor changed tactics, and the next day he deployed fire hoses and police dogs against a peaceful protest march in the downtown business district. The images, some of the most grotesque and iconic of the era, dominated nightly news broadcasts and national newspapers and magazines nationwide. In Washington, lawmakers took up the issue of civil rights legislation with renewed vigor. President John F. Kennedy said the day’s events were “so much more eloquently reported by the news camera than by any number of explanatory words,” calling the scene “shameful.”

In a paralyzed Birmingham, more than 2,000 people had been arrested, with officials turning the state fairgrounds into a makeshift holding area. The fire department bucked Connor’s orders to redeploy its hoses against demonstrators. The city’s chamber of commerce pleaded for talks, even as political leaders were steadfast in their commitment to Jim Crow. By May 8, the white business leaders had acceded to most of King’s demands, promising to desegregate diner counters, rest-rooms and water fountains within 90 days.

It was far from total victory, but King had something more important: the attention of an outraged and rapt nation. The legacy of the water cannons and dogs, of callused feet and imprisoned children, would be incarnated in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act and the Twenty-Fourth Amendment, which banned poll taxes. Montgomery and Birmingham also formed the script for peaceably countering injustice in a nation founded on protest. From antiwar protests during Vietnam to Occupy Wall Street and beyond, King’s commitment to nonviolent protest lives on.

Imprisoned in Birmingham Jail, King wrote in praise of those nonviolently demonstrating outside “for their sublime courage, their willingness to suffer and their amazing discipline in the midst of great provocation. One day the South will recognize its real heroes.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Javier Milei’s Radical Plan to Transform Argentina

- The New Face of Doctor Who

- How Private Donors Shape Birth-Control Choices

- What Happens if Trump Is Convicted ? Your Questions, Answered

- The Deadly Digital Frontiers at the Border

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 31 Most Anticipated Movies of Summer 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

The Power of Peaceful Protests

From the Salt Marches to the Montgomery Bus Boycott, history is littered with examples of peaceful protests having a powerful and lasting impact; shaping the world to become a fairer, freer and more peaceful place.

In recent weeks, over 50 demonstrations occurred across the United Kingdom, focussed on a broad range of issues ranging from environmental concerns to rising living costs 1 .

While driven by different triggers and motivations, these instances are not unique. The last few years have seen an increasing prevalence of demonstrations related to civil liberties and human rights. New technologies and social movements have enabled campaigns to gain traction and spread globally, encouraging their potential to become hugely influential.

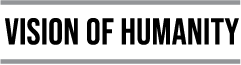

Despite this, the latest Global Peace Index highlights a number of worrying trends. Violent demonstrations have risen by almost 50% since 2008. During this period, 126 countries deteriorated in their violent demonstrations score, compared to only 22 countries improving.

Positive Peace is defined as the attitudes, institutions and structures that create and sustain peaceful societies. While the other domains have improved since 2008, the attitudes domain has deteriorated by 1.8%, demonstrating a clear link between Positive Peace and the global trend in violent demonstrations.

Impact of peaceful protests

Building consensus is a critically important part of ensuring movements maintain momentum. The use of violence in a protest movement risks undermining that consensus and can alienate those who would otherwise support a cause. An example of this consensus building can be seen with the Salt Marches of the Indian Independence Movement.

Led by Mahatma Gandhi in 1930, during the height of Britain’s colonial occupation of India, dozens of activists marched over 240 miles to collect salt from the Arabian sea to protest a law preventing Indians from buying or selling salt in the country. This act of resistance was met with a crackdown from the British authorities, leading to the imprisonment of 60,000 people. That a peaceful protest was met with such a response drew publicity for the Indian Independence movement, garnering support from all over the world. This event was a significant turning point, triggering widespread civil disobedience that eventually led to India gaining its independence in 1947. The actions of Gandhi and his peers also heavily influenced the American civil rights movement.

Furthermore, the use of non-violence does not necessarily mean taking to the streets in protest. Techniques such as boycotts and strikes can be equally effective ways of making a change. Economic disinvestment and boycotts of South African goods, for example, played a key role in helping to end apartheid. In 1955 perhaps the most famous coordinated peaceful boycott occurred, Montgomery Bus Boycott. African-American activist Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white passenger on the racially segregated public transport system in Alabama. This triggered a 13-month mass boycott of public transportation by protesters, which had an enormous financial impact. The protest ended with the US Supreme Court ruling the policy of segregation unconstitutional, a watershed moment in the civil rights movement.

While mass boycotts are effective, even protests with a small number of participants can communicate messages and achieve change. Research suggests that it only requires 3.5% of the population to engage in non-violent resistance for these movements to be effective 2 . One such example was the infamous Black Power Salute at the 1968 Summer Olympics. After winning medals in the 200m sprint, African-American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists while wearing black gloves during the American national anthem. This powerful message was seen around the world, drawing attention to the civil rights movement in America.

More recently, in 2018, 15 year-old Swedish school student Greta Thunberg decided to sit outside the Swedish parliament for three weeks. She held a sign reading “School Strike for Climate” to protest her government’s response to the growing climate emergency. What began with an individual protest by one teenager, triggered student-led protests all over the world and became part of a global movement against climate change. Thunberg’s activism has given her a platform, through which she has inspired millions. Thunberg’s actions and the actions of the 1968 Olympians show how it is possible, even for individuals, to make an enormous impact and inspire change.

The wave of aggressive anti-protest laws

While the impact and influence of protests and demonstrations continue to grow, this is being met with a wave of aggressive legislative restrictions, policies and responses designed to limit their effectiveness.

For example, 93% of the protests against racial injustice in the United States in the wake of the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer were peaceful; however, the narrative around the protests was that they were largely violent demonstrations and as such triggered an excessive police response 3 .

In Sri Lanka, which ranked 90 on the Global Peace Index (GPI), the new government responded to protests with the widespread use of draconian emergency regulations. These laws granted the authorities sweeping powers to suppress protests and detain and punish activists 4 . The rise in demonstrations, and the violent crackdown, will likely be reflected in Sri Lanka’s ranking in next year’s GPI.

The United Kingdom ranked 34 on the GPI, has also recently strengthened its anti-protest laws; granting the authorities greater power to disrupt and limit protests, particularly those such as the Extinction Rebellion 5 . Furthermore, a number of territories within Australia (ranked 27 on the GPI) have recently passed anti-protest laws granting authorities more powers to specifically target non-violent environmental protesters 6 .

In their early days, digital tools such as social media played a key role as a tool for mobilisation. However, increasingly they are being weaponised by authoritarian states and used as a tool to quell protests and identify protesters.

As can be seen with the violent crackdowns on protests security forces often carry out – protests, demonstrations and social movements are not without their challenges. More often than not, the establishment does not support change and protesters are often vilified as well as legislated against.

Non-violent resistance is approximately ten times more likely to lead to democratisation than violent resistance

The expansion of legal restrictions and obstacles to protest presents a growing challenge to non-violent resistance. Despite this, non-violent resistance remains an incredibly effective tool for triggering substantial, supported and long-lasting social change. The research suggests that non-violent resistance is approximately 10 times more likely to lead to democratisation than violent resistance 2 .

Peaceful protests are a way for ordinary people to have their voices heard. Inherent power imbalances in society can result in people feeling marginalised and disenfranchised. Non-violent civil movements can offer anyone the opportunity to become involved and have a voice.

Between climate-related threats, widespread conflict and displacement, and increasing food insecurity, the challenges facing the world are complex and innumerable. Time and again, the power of peaceful protest has been proven as a tool to meet these challenges and make a positive change.

The interconnected and globalised world in which we live enables movements and ideas to spread, despite the many challenges they face. It is this power that continues to drive activists to the streets to pursue change.

1. ‘It’s scary – things are escalating fast’: protesters fill UK streets to highlight climate crisis and cost of living | Protest | The Guardian

2. Why nonviolent resistance beats violent force in effecting social, political change – Harvard Gazette

3. 93% of Black Lives Matter Protests Have Been Peaceful: Report | Time

4. Sri Lanka: Heightened Crackdown on Dissent | Human Rights Watch

5. What is the Police and Crime Bill and how will it change protests? – BBC News

6. Victorian and Tasmanian governments under fire for laws that target environmental protesters | Environment | The Guardian

Jerome Gavin

Jerome is studying a Masters of International Security at the University of Sydney, specialising in Peace and Conflict studies.

Vision of Humanity

Vision of Humanity is brought to you by the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), by staff in our global offices in Sydney, New York, The Hague, Harare and Mexico. Alongside maps and global indices, we present fresh perspectives on current affairs reflecting our editorial philosophy.

RELATED POSTS

Civil Unrest

How does positive peace affect protest movements.

What can Positive Peace tell us about social movements and civil resistance campaigns?

Global Peace Index

Peacefulness declines to lowest level in 15 years.

June 15 2022, Today marks the launch of the 16th edition of the Global Peace Index from the international think-tank the Institute for Economics &...

RELATED RESOURCES

January 2022

Positive peace report 2022.

Analysing the factors that sustain peace.

Global Peace Index 2022

Measuring peace in a complex world.

Never miss a report, event or news update.

Subscribe to the Vision Of Humanity mailing list

- Email address *

- Future Trends (Weekly)

- VOH Newsletter (Weekly)

- IEP & VOH Updates (Irregular)

- Consent * I accept the above information will be used to contact me. *

- HISTORY & CULTURE

- RACE IN AMERICA

2020 is not 1968: To understand today’s protests, you must look further back

The conflicts of 2020 aren’t just a repeat of past troubles; they’re a new development in the American fight for racial equality.

Coming together in opposition to police brutality and the death of George Floyd, protesters stand together in the streets of New York City on June 4, 2020.

The 1960s Black Power activist formerly known as H. Rap Brown once said that “violence is as American as cherry pie.”

Over the last two weeks, more than a thousand protests —most of them peaceful, though some devolved into violence—have swept across America caused by outrage over the death of George Floyd, recorded as a Minneapolis police officer pressed a knee to his neck for nearly nine minutes while Floyd was handcuffed and lying face down. Floyd was one of approximately 1,100 people killed annually by police use of force in the United States in recent years, according to data compiled by Fatal Encounters , a nonprofit that tracks police-involved deaths since 2000. A disproportionate number of the people killed, like Floyd, are African American.

Casting their eyes to the past, observers search for comparisons to today’s uprisings in the chaos of 1968. But the roots of 2020’s events go far deeper into the last hundred years of American history, which were punctuated by race riots, massacres, and clashes between the police and African Americans. Starting in 1919, three major waves of nationwide uprisings in the 20th century shed light on how the fight for racial equality has grown, how it’s changed, and what has stayed the same.

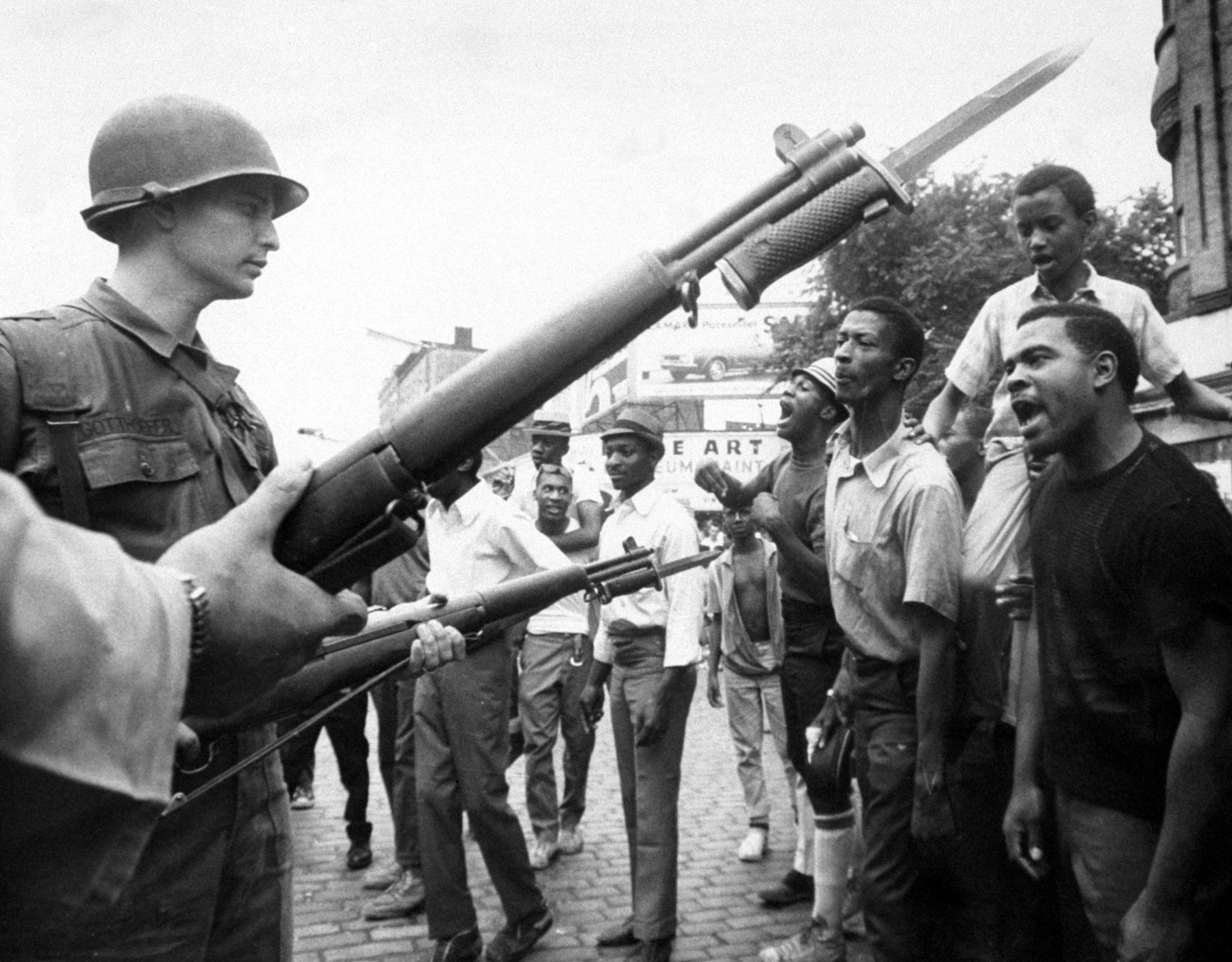

In July 1967, the beating of a black cab driver by white police officers began a six-day riot in Newark, New Jersey, leading to the deployment of the National Guard.

More than 50 years later, protesters take to the streets of New York with raised fists, signs, and cell phones to speak out against the death of George Floyd at the hands of a police officer.

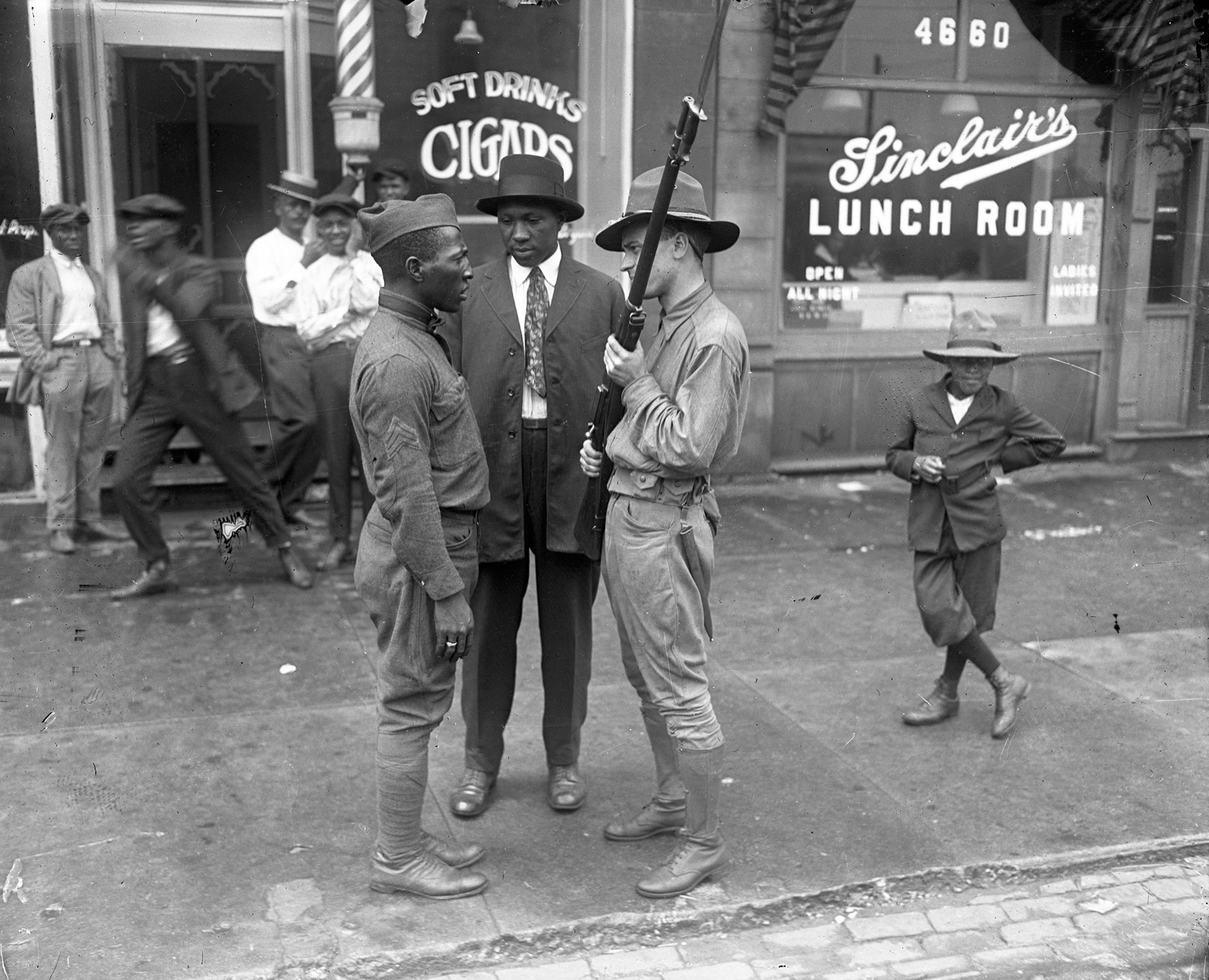

The first wave came in the early 20th century, culminating in the so-called Red Summer of 1919, when the country was recovering from World War I, bitterly divided by racial and gender tensions and anti-immigration fervor, and ravaged by the deadly Spanish flu epidemic. That year, dozens of violent racial clashes played out with ferocity in at least 25 places including small towns such as Elaine, Arkansas, and Bisbee, Arizona, and in big cities, including Omaha, Nebraska, Chicago, Illinois, and Washington, D.C. During this first wave, hundreds of thousands of African Americans were moving north in what came to be known as the Great Migration , seeking jobs created by wartime spending and fleeing the violence and oppression in the former Confederacy.

In 1921, white mobs, with the complicity of local police, torched Tulsa, Oklahoma’s black business district , known as “Black Wall Street,” killing about 300 people and leaving nearly all of the city’s black population homeless. In most of these massacres and riots, the police turned a blind eye to white violence and instead arrested African Americans for defending themselves.

Tensions between whites and African American World War I veterans was one of the the underlying causes of the Red Summer of 1919; in Chicago, the state militia was called in to police the riots.

The Chicago 1919 Race Riot was one of the Red Summer’s most devastating; lasting for 13 days, it left 38 people dead and 537 injured. In this image, an armed white mob pursue an African American man.

During the riot, whites set fire to scores of African American homes, leaving more than a thousand people homeless.

In response to these brutal tactics, African Americans invested energy in building up civil rights organizations in the 1920s and 1930s. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909, expanded its nationwide campaign for racial justice, creating one of the largest mass-membership organizations in the country, with 500,000 members by 1945. Millions of African Americans—in both the urban North and the rural South—gravitated toward organizations that promoted racial pride and self-determination, most notably the United Negro Improvement Association, led by Marcus Garvey. Empowered by the right to vote (a right denied to blacks through voter suppression across most of the South), African Americans in northern cities began to exercise their electoral clout.

For Hungry Minds

Fighting fascism abroad, racism at home.

The second mass wave of protest and racial violence came during the disruptive years of the Depression and World War II. In 1941, when civil rights and labor leader A. Philip Randolph threatened a March on Washington to demand that the federal government open up defense jobs to African Americans, President Franklin Roosevelt succumbed to the pressure and signed an order creating the Committee on Fair Employment Practices. The hypocrisy of racism in a country that was fighting a world war for democracy fueled anger among many African Americans, unleashing one of the most intense periods of black political organizing and white opposition ever.

In a second wave of the Great Migration, hundreds of thousands of black workers moved north and west during the war, finding jobs in aircraft factories and shipyards. Newspapers serving African American communities, led by the Pittsburgh Courier , publicized racial discrimination and violence and launched the “Double V” campaign for victory against fascism abroad and against white supremacy at home.

In August 1944 protesters marched in support of the Philadelphia Transit Company's decision to allow black men to drive trolleys after white employees went on strike. Many supporters called on African American's experiences in World War II: "We drive tanks. Why not trolleys?"

On June 21, a white mob riots and overturns a car. For about 24 hours in June 1943, Detroit, Michigan experienced one of the second wave's worst race riots, resulting in the deaths of 25 blacks (17 of whom were killed by police) and 9 whites.

During the Detroit Race Riots, a member of the surrounding white crowd attacks a black man in police custody.

In Mobile, Alabama and Detroit in 1943, whites fearful of rising black militancy and competition for jobs and housing rampaged through black neighborhoods and attacked black workers, a reprise of what had happened in the 1919 Red Summer. More than 240 race riots broke out that year throughout the United States. African Americans were not the only targets; the same year, in Los Angeles, white mobs angry about a new racial threat attacked young Mexican American men. In all of these cities, the police swept in, taking the side of white rioters.

During and after World War II, African Americans actively protested—both peacefully and violently—against racism and police brutality. New York’s City’s Harlem neighborhood was a hotbed of civil rights activism. In August 1943, after a white police officer shot Private Robert Bandy, an African American soldier on leave, angry crowds of blacks outraged at police brutality broke shop windows and clashed with law enforcement officials. In wartime Birmingham, Alabama , African Americans resisted second-class treatment on the city’s buses, clashing with white drivers, passengers, and police. In 1943 and 1944, civil rights activists in Chicago staged sit-ins at restaurants that refused to serve blacks. Those protests snowballed into a nationwide movement between the war and the mid-1960s.

The turbulent Sixties

Fueled by growth of the civil rights movement, a third and enormous wave of urban uprisings swept the country between 1963 and 1968. The protests grew out of decades of grassroots organizing against racial segregation and discrimination in employment, housing, transportation, and commerce, both in the North and the South.

In 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference marched in Birmingham, Alabama, demanding the desegregation of department stores, restaurants, public restrooms, and drinking fountains. In a violent show of force, Birmingham Commissioner of Public Safety Eugene “Bull” Connor infamously ordered police officers and firefighters to turn guard dogs and fire hoses on nonviolent protestors, many of them schoolchildren. In retaliation for the brutality, angry local blacks calling for self-defense rampaged through the city’s business district. When peaceful demonstrations did not get the desired results and law enforcement officials used force to suppress dissent, protestors often turned to more disruptive tactics.

Pointed bayonets and looming tanks menace protesters in the Memphis Sanitation Workers' Strike on March 28, 1968. Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. would travel to Tennessee in support of the strike on April 3. King would be assassinated the following day.

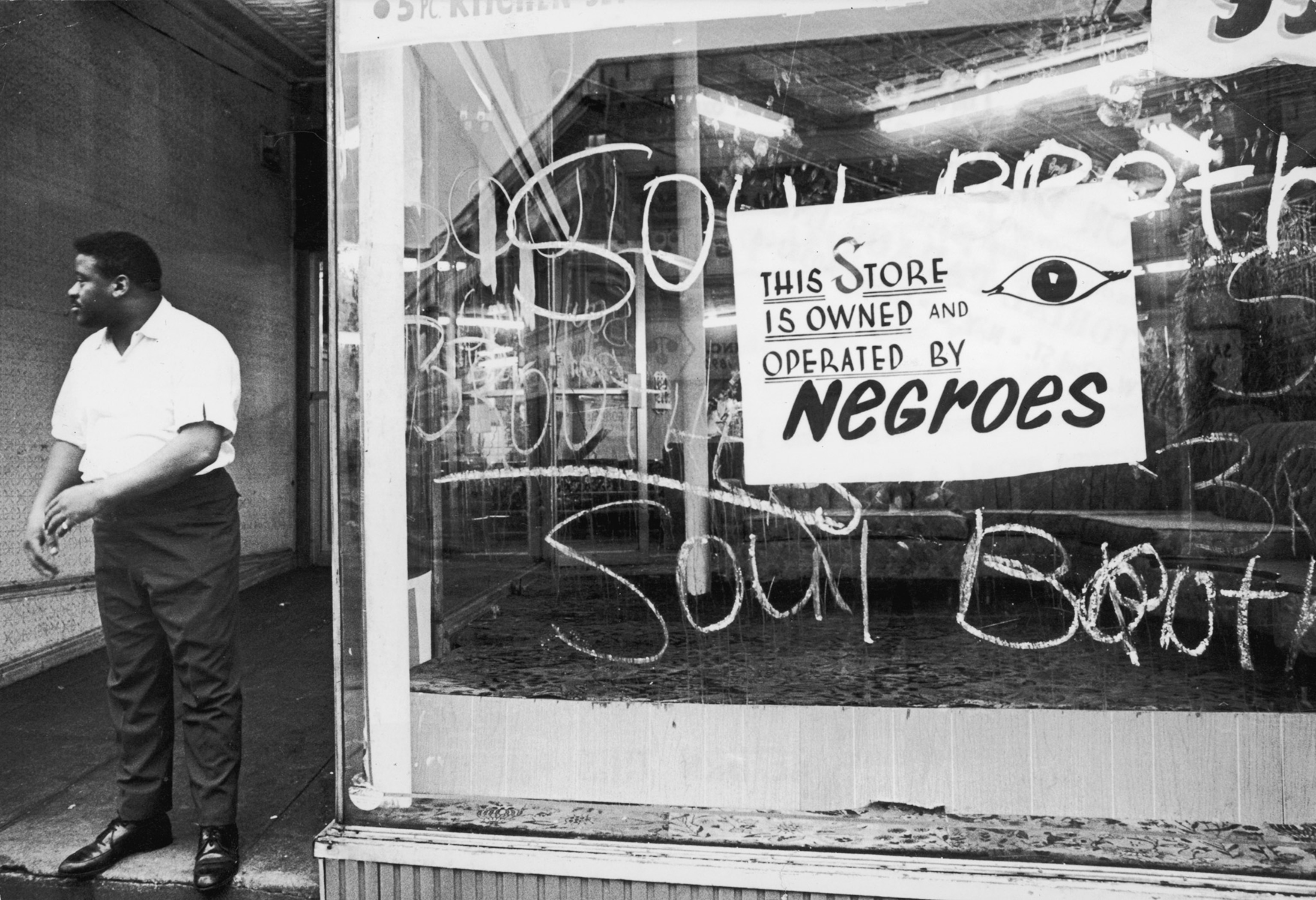

During the Newark Race Riots in July 1967, African American businesspeople, like this store owner, appealed to racial solidarity to protect their businesses from looting.

Peaceful protests, like this one in Birmingham, Alabama, were met with a violent police responses. In 1963 water cannons were fired on young African Americans during a protest against segregation, organized by Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth.

It was a pattern that would be repeated hundreds of times over the next several years, drawing energy from the rising Black Power movement, which called for black pride, self-defense against racist attacks, and self-determination. Philadelphia, Harlem, and Rochester burned in 1964; Los Angeles in 1965; and Chicago and other cities in 1966, culminating in the “Long Hot Summer” of July 1967, when 163 cities erupted in collective violence over police brutality and indifference to black suffering.

African Americans burned and looted stores and faced violent retribution on the part of big cities’ nearly all-white police forces. In Newark, New Jersey, 34 people died, 23 of them at the hands of the police. In Detroit, 43 people died, most of them shot by some 17,000 police, National Guard, and military troops sent to put down the rebellion. In April 1968, sorrow and fury over Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination turned to uprisings in which more than 100 cities were burned.

The 1960s uprisings differed from their precursors in 1919 and 1943. The later demonstrations—both nonviolent and disruptive—were led by African Americans, unlike the race riots in Chicago, Tulsa, Detroit, and Los Angeles that were instigated by white mobs. In the 1960s, almost all looting and burning happened in African American neighborhoods, targeting mostly white-owned local shops accused of overcharging black customers for inferior goods. Some whites joined in vandalizing stores, but the crowds and the business districts affected were overwhelmingly black.

The only whites out on the streets in sizeable numbers were law enforcement officials, who fueled the flames of discontent by beating and shooting protestors. Many white Americans—including presidential candidates Richard M. Nixon and George Wallace—cheered the police. Those who were more sympathetic to black protesters included prominent members of the blue-ribbon, bipartisan Kerner Commission, established by President Lyndon B, Johnson to investigate the causes of the 1960s uprisings. Its 11 members, including the nation’s only black U.S. Senator, Edward Brooke (R-Mass), and NAACP Executive Director Roy Wilkins, published a bestselling report that concluded that for many blacks, “police have come to symbolize white power, white racism, and white repression.”

You May Also Like

MLK and Malcolm X only met once. Here’s the story behind an iconic image.

These Black transgender activists are fighting to ‘simply be’

What was the Stonewall uprising?

Changing face of protest.

In the decades that followed 1968, outbreaks of protest and conflict were more geographically isolated, but their causes and fury foreshadowed the events of 2020. In 1992, mass protests and riots exploded in Los Angeles after the acquittal of white police officers who were captured on video brutally beating black motorist Rodney King. Twenty years later, the deaths of more African Americans at the hands of police ignited public outrage, mass protests, and sometimes attacks on white-owned businesses. Activists around the country loosely banded together in the Black Lives Matter movement, founded in 2013 by Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi in response to the acquittal of a Florida man who fatally shot an unarmed 17-year-old black student, Trayvon Martin, who was visiting relatives in a gated community. The coalition uses protests, social media, and publicity to shine a bright light on police violence against African Americans.

Since George Floyd's death on May 25, 2020, protests have spread from Minneapolis, the site of Floyd's death, to all 50 states and around the world. Kingmil Miceus is among those protesting in Nyack, New York.

2020’s uprisings resemble those of 1919, 1943, and 1968 in certain respects: They grow out of simmering hatreds seeded by the long, festering history of white violence and police brutality against African Americans that has taken hundreds of lives of per year , including Floyd, Breonna Taylor , and Ahmaud Arbery , three of the most recent victims. Most of 2020’s protests have been peaceful, early reports have found , with a fraction becoming violent.

But more than ever before, today’s demonstrations are markedly interracial—African American, Asian American, Latinx, and white faces, covered by masks to prevent the spread of COVID-19, appear in city centers, blockaded across bridges and highways, and gathered in front of the White House. It suggests a new phase of opposition that is uniting groups who did not have much in common for most of American history. In cases where conflicts have erupted, those assaulted, tear-gassed, or shot with rubber bullets are of all races.

In Minneapolis shortly after Floyd's death, police fired tear gas at protesters outside the 3rd Police Precinct. Like protests in the past, violence and looting have erupted out of some of 2020's protests.

In New York City, anger has been directed at chain stores and the city's wealthier neighborhoods, a marked change from the riots of decades past.

The geography of violence and looting looks different in 2020 as well. Clashes of the past happened mostly in black neighborhoods; today, they have often started and spread to wealthy downtowns and suburban shopping malls. Looters have gone after local shops and global chains in wealthy neighborhoods such as Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, Soho in New York, and Buckhead in Atlanta. We can’t yet wholly grasp the significance of demonstrators spraying graffiti that say both “Black Lives Matter” and “Eat the Rich” but amidst soaring unemployment and ongoing racial injustice, we might be seeing something that is both old and new.

Protests in past decades often saw people of different races on different sides. In 2020, protesters of different races, who wear masks as a caution against COVID-19, rally together in New York City on June 1, 2020.

The solidarity of today’s protesters transcends the bloody racial divides of the past and may be a springboard for more sweeping reforms. George Floyd’s death has sparked a global movement, with statues of slaveowners being torn down from Bristol, England to Richmond, Virginia ; anti-police protestors taking the knee from Seattle to Rio de Janeiro and Rome; and U.S. public officials debating whether to defund or rebuild their police forces from the ground up.

It remains to be seen if the uprisings of 2020 will resolve the long-standing issues of racial injustice fought again and again on America’s streets, but when many races march together rather than face off, the arc of history may be bending toward justice again.

Related Topics

- AFRICAN AMERICANS

- CIVIL RIGHTS

10 million enslaved Americans' names are missing from history. AI is helping identify them.

Harriet Tubman, the spy: uncovering her secret Civil War missions

Who was Martin Luther King, Jr.?

The surprisingly subversive history of mini golf

Meet the 5 iconic women being honored on new quarters in 2024

- Paid Content

- Environment

- Photography

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- World Heritage

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Why Protests Are Necessary, Even When They Inconvenience People

This is a conversation I’ve seen before, and it has only escalated in recent months. It’s a conversation that has happened for years when it comes to protests for racial justice and other critical human rights issues, and it has made its way to climate conversation too. When Extinction Rebellion protesters began glueing themselves to public transport, or spraying buildings with fake blood. When kids start missing school, or organising en masse and challenging leaders. The words vary, but the general idea stays the same: why are they inconveniencing innocent people? Why are they blocking roads? Why don’t they let people do their job? Of course we should do something about injustice, but we don’t want to be an idiot about it.

Well, I decided it was time to address and examine these things a little more, because I imagine this conversation will happen a lot in the coming weeks. To save myself the time of having this conversation on repeat, and hopefully to help you too, I’m writing an explanation here.

So today let’s talk about the idea of civility .

Civility doesn’t mean what you think it means

When we have arguments about methods of protest, civility is a word that comes up a lot. When we think of the word civility, most of us will think of the modern definition, which is about politeness and courtesy. The idea is that protest movements like Extinction Rebellion aren’t civil, because they aren’t courteous and considerate of innocent bystanders, usually by disrupting their commutes by doing things like blocking roads. I understand this argument; of course it’s frustrating to be caught up in something when you aren’t the one that caused it.

However, it’s also important to recognise that the call for protestors to be more civil is also a fundamental misunderstanding of the word. Here’s a little etymology:

“‘Civitas’ is a juridical and political construct that Greco-Roman antiquity bequeathed to Western civilization. In Latin, it meant ‘city,’ in the sense of city-state, the body politic, the commonwealth. Consequently, ‘civilitas’—which became ‘civility’ in English—was the conduct becoming citizens in good standing, willing to give of themselves for the good of the city,”… “Building on the notion of ‘civilitas,’ here is a possible definition of civility for our times: The civil person is someone who cares for his or her community and who looks at others with a benevolent disposition rooted in the belief that their claim to well being and happiness is as valid as his or her own.”

We associate civility with being polite, but at its heart civility is deeply concerned with justice. To be civil is to care for your community, for your neighbour, for people you don’t know. To be civil is to be concerned with true equality, which means one must also to be invested in the work of dismantling racism, homophobia, the patriarchy, ableism, economic inequality, corruption, persecution of Indigenous peoples, violence and more. Advocating for the environment is fundamental to these issues because the marginalised are the first to be hurt by climate breakdown .

We know that polite dialogue alone does not create change, because marginalised communities have been talking about these issues for decades , their voices largely ignored . Oppressed people are already hurt by climate breakdown both globally and locally , and so the notion of what it means to be a good citizen must evolve with this knowledge.

Because civility is concerned with morality and with fighting for the rights and quality of life for all, and because there is an urgent need to protect the most vulnerable in our society, this cannot and does not always look like politeness.