Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Research disruption during PhD studies and its impact on mental health: Implications for research and university policy

Contributed equally to this work with: Maria Aristeidou, Angela Aristidou

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Institute for Educational Technology, The Open University, Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation UCL School of Management, London, United Kingdom

- Maria Aristeidou,

- Angela Aristidou

- Published: October 18, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291555

- Reader Comments

Research policy observers are increasingly concerned about the impact of the disruption caused by the Covid-19 pandemic on university research. Yet we know little about the effect of this disruption, specifically on PhD students, their mental health, and their research progress. This study drew from survey responses of UK PhD students during the Covid-19 pandemic. We explored evidence of depression and coping behaviour (N = 1780) , and assessed factors relating to demographics, PhD characteristics, Covid-19-associated personal circumstances, and significant life events that could explain PhD student depression during the research disruption (N = 1433) . The majority of the study population (86%) reported a negative effect on their research progress during the pandemic. Results based on eight mental health symptoms (PHQ-8) showed that three in four PhD students experienced significant depression. Live-in children and lack of funding were among the most significant factors associated with developing depression. Engaging in approach coping behaviours (i.e., those alleviating the problem directly) related to lower levels of depression. By assessing the impact of research disruption on the UK PhD researcher community, our findings indicate policies to manage short-term risks but also build resilience in academic communities against current and future disruptions.

Citation: Aristeidou M, Aristidou A (2023) Research disruption during PhD studies and its impact on mental health: Implications for research and university policy. PLoS ONE 18(10): e0291555. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291555

Editor: Yadeta Alemayehu, Mettu University, ETHIOPIA

Received: January 23, 2023; Accepted: August 31, 2023; Published: October 18, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Aristeidou, Aristidou. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The raw dataset on PhD students' patient health questionnaire scale and coping mechanisms is available from the Open Research Data Online (ORDO) database: https://doi.org/10.21954/ou.rd.22794203 .

Funding: This work was supported by the Institute of Educational Technology at The Open University (MA) and the University College London (UCL) School of Management (AA). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The abrupt outbreak in January 2020 and the global proliferation of a novel virus (Covid-19) has created a crisis for many sectors, including the international higher education (HE) sector [ 1 ] that continues during the ‘post-pandemic’ period. A point of particular alarm for HE leaders, policy observers, and governments is the disruption to the typical flow and pace of university research activity. While research related to Covid-19 is still in overdrive, other research was slowed or stopped due to worldwide physical distancing measures to contain the virus’ spread (e.g., sudden campus and laboratory closures, mobility restrictions, stay-at-home orders) [ 2 ]. The resulting ‘drop in research work’ is suggested to have a detrimental impact on the HE sector on the ‘research and innovation pipeline’ [ 3 ], and on ‘research capacity, innovation and research impact’ [ 4 ].

As research and university policies internationally are being (re)shaped at a rapid pace in efforts to meet the challenge of university research disruption [ 5 ], we contribute to academic and policy conversations by examining the effect of the research disruption on the mental health of PhD students. A considerable body of research acknowledges the role of PhD students in the innovation process, in knowledge creation and diffusion (e.g., [ 6 ]) and further posits that the period of one’s PhD program is key to early career success and research productivity (e.g., [ 7 ]). These outcomes, which matter to research policy, have been linked to PhD student mental health [ 8 – 10 ]. In those times of relative stability, research had additionally demonstrated the higher prevalence of mental health issues amongst the PhD student population across research disciplines, as compared to other students within academia [ 9 ] and the general population [ 9 , 11 , 12 ]. In the period since Covid-19 disrupted our social and economic lives, depression levels in the general population have been exacerbated globally [ 13 , 14 ]. These trends suggested that the already high prevalence of poor mental health in PhD students is likely to be further exacerbated during the pandemic. Indeed, as reported in early studies on research students’ experience of the Covid-19 pandemic (e.g., [ 15 ]) and the post-pandemic period (e.g., [ 16 ]) the impact on students’ mental wellbeing has been significant, with students suggesting a number of support measures at institutional and national level.

Ignoring, at this critical moment, the increased likelihood of poor mental health in PhD students may jeopardize research capacity and HE competitiveness for years to come. Therefore, there is a pressing need to identify–within the PhD student population–those whose mental health is more affected by the research disruption, so that policies and assistance can be timelier and more targeted. Additionally, by understanding more clearly the factors that may contribute to poor mental health, and their interrelationships (presented in Methods), policymakers and HE leaders may be better placed to tackle, and ultimately overcome, this and future research disruptions.

Motivated by the current lack of an empirical basis for insights into PhD students’ mental health during the pandemic-induced disruption, we collected survey data contemporaneously during July 2020. Our 1780 survey respondents are PhD students in 94 UK Universities, across the natural and social sciences and across PhD stages. Our study has three objectives: first, to explore mental health prevalence (depression) and coping behaviour in a large-scale representative sample of PhD students in the UK (O1); second, to evaluate the relationships among mental health prevalence and coping behaviour (O2); third, to identify factors that increase the likelihood of poor PhD student mental health during the period of research disruption (O3). Our study extends previous research on mental health in the HE sector by considering the dynamics of severe disruption, as opposed to the dynamics of relative stability, on PhD students’ mental health, performance satisfaction, and coping behaviours.

Background and literature review

Uk phd students’ mental health in times of disruption.

In the UK, there are approximately 100,000 postgraduate students completing doctoral research [ 17 ]. Since 2018, significant government funding has been targeted at developing insights into supporting UK PhD students’ mental health [ 18 ]. Still, with the exception of Byrom et al. [ 11 ], published research on PhD students’ mental health in the UK exhibits the same limitations as the international research: It reflects discipline- or institution-related specificity (e.g., [ 19 ]) or utilizes samples of early career researchers in general (e.g., [ 20 ]).

Early findings on postgraduate research students’ wellbeing during the pandemic showed that only a small proportion of them are in good mental health wellbeing (28%) while the rest demonstrate possible or probable depression or anxiety [ 15 ]. Goldstone and Zhang [ 15 ] further highlight the differences among student groups with, for example, students with disabilities or caring responsibilities or female students having lower levels of mental wellbeing. The post-pandemic findings have been more promising, as only about one in four students were at risk of experiencing mental health issues [ 16 ].

In response to the Covid-19 research disruption, substantive actions have been taken by the HE sector and the UK Government to disseminate approaches deployed by UK universities to support student mental health (e.g., [ 18 ]) and to update mental health frameworks for UK universities (e.g., [ 4 ]), but so far, mitigation activities have been targeting mental health for UK university students broadly, not UK PhD students specifically.

Overcoming the paucity of evidence on UK PhD students’ mental health during the pandemic is a crucial first step to drawing strong conclusions on the prevalence and determinants of mental health issues and ways to mitigate them specific to the PhD population. For example, policy recommendations by UK postgraduate respondents during the pandemic [ 15 ] focused mainly on financial support, such as extensions to their funded period of study and tuition and visa fee support (including waivers to fees). To develop an overarching framework specific to the Objectives of our study, we synthesize insights from the international literature on PhD student mental health conducted in the period before the research disruption.

International research on PhD student mental health in times of relative stability

In the international literature examining mental health specifically for PhD students (see the systematic review in [ 21 ], the issue of mental health for PhD students is acknowledged to be multidimensional and complex [ 10 ]. In this growing research area, some address mental health as an aspect of the broader ‘health’ of the PhD students (e.g., [ 22 ]), some focus on psychological distress [ 23 ], while others take depression as a specific manifestation of distress [ 9 , 24 ]. The latter is particularly interesting because depression within the PhD population in these studies is often assessed with standardised questionnaires (e.g., PHQ, see below) that allow for developing comparative insights. It is also the approach adopted by the only global survey of PhD students’ mental health by Evans et al. [ 12 ], showing that 39% of PhD students report moderate-to-severe depression, significantly more than the general population.

Literature on PhD student’s mental health determinants in times of relative stability

Past literature on PhD students’ mental health offers insights into the determinants of PhD students’ mental health in times of stability, which may help understand the relationships we want to examine between PhD mental health, performance satisfaction and coping in times of research disruption.

First, past studies evidence the influence of PhD students’ personal lives on poor mental health. PhD students with children or with partners are less likely to have or develop psychological distress [ 9 ]. The normalcy of family roles is a much-needed antidote to the known pressures of a PhD program [ 25 ] and might even protect against mental health problems [ 22 , 26 ]. Other aspects of PhD students’ personal lives, such as significant life events (e.g., severe problems in personal relationships or severe illness of the student or someone close to them), have been linked to dissatisfaction with their research progress [ 24 ]. Research progress is defined as students’ perception of their progress in the completion of their degree [ 27 ] and is linked to their mental health. Dissatisfaction is tied to negative outcomes, such as attrition and delay [ 28 ], but also to lower productivity and mental health problems, such as worry, anxiety, exhaustion, and stress [ 29 ]. Related to this, Levecque and colleagues [ 9 ] observed that PhD students expressing a high interest in an academic career are in better mental health than those with no or little interest in remaining in academia.

Second, gender was the key personal factor that emerged as a determinant for mental health in past studies: PhD students who self-identify as female report greater clinical [ 9 , 30 ] and non-clinical problems with their mental health [ 23 , 31 ]. This is explained through the additional pressure women report on their professional and personal lives [ 23 ].

Third, past studies argue that each PhD phase presents PhD students with specific sets of challenges and should thus be explored discreetly in relation to mental health [ 32 ]. Still, the evidence on the link between the PhD phase (or the year of study as a proxy for the PhD phase) and mental health is inconclusive. Barry et al.’s [ 33 ] survey reports no connection between the PhD phase and depression levels in an Australian PhD population. However, Levecque et al. [ 9 ] report high degrees of depression in the early PhD stage of students in Belgium, and a global survey of PhD students across countries and disciplines shows that depression likelihood increases as the PhD program progresses [ 32 ].

Fourth, past research offers strong evidence that financial concerns impact PhD students’ mental health negatively. In a study by El-Ghoroury et al. [ 34 ], 63.9% of PhD students cited debt or financial issues as a cause for poor wellbeing and cited financial constraints as the major barrier to improving their wellness (through social interactions, outside-PhD activities, etc). Even uncertainty about funding was shown to predict poor mental health [ 9 ]. To this end, Geven et al. [ 35 ] explored packages of reforms in a pre-pandemic graduate school programme, including an extension of the grant period, and indicated that such policies can increase students’ completion rates to up to 20%.

Finally, age is not shown to be associated with mental health [ 9 ], but numerous studies found that having children, particularly for female PhD students and in Science-Technology-Engineering-Maths (STEM) disciplines [ 36 ], consistently corresponds with heightened stress [ 37 ]. However, a specific examination of the relationship between children and mental health indicates that PhD students with one or more children in the household showed significantly lower odds of having or developing a common psychiatric disorder [ 9 ]. Further, parenting and, in particular, motherhood during doctorate studies contribute to the development of students’ coping mechanisms that allows them to succeed in a balance in both worlds [ 38 ].

Past research insights into PhD mental health and coping

Past research explored how PhD students may “cope” with stressors and thus mitigate poor mental health [ 39 ]. Studies identify the importance of social interactions (e.g., [ 22 ]); balancing life demands (e.g., [ 16 ]), reaching out for social support (e.g., [ 40 ]) sometimes through peer relationships (e.g., [ 10 , 39 ]); and ‘planning’ (e.g., [ 22 ]); As invaluable as these insights are, drawing comparisons between these findings is difficult because often the identification of coping styles or strategies was not the focus of these studies, making it difficult to draw fine-grained conclusions as to their effect on PhD students’ mental health.

There is, however, a long tradition of research on coping for physiological wellbeing that provides standardised measures for individuals’ coping and their link to mental health [ 41 ]. The most widely used measurement instrument in the literature reviewed is the COPE Inventory, which allows researchers to assess how people cope in a variety of stressful situations, including in HE for students [ 42 – 44 ], making it particularly relevant to the context and sample under investigation in our study of PhD students. Additionally, COPE allows for the identification of consistent ways of coping, which provides predictive validity across a range of situations. Predictive validity is desired when examining the role of coping in relation to mental health. Indeed, multiple studies have linked the COPE measurement to mental health outcomes (e.g., [ 45 , 46 ]), including depression [ 43 ], which is a focus of our study.

Data and methods

Participants.

For the current study, we recruited participants that were active PhD students from March to July 2020 at any stage of their research to take part in an online survey. The survey ran between the 31st of July and the 23rd of August 2020, with the aim of capturing the potential impact of the Covid-19 disruption during the first lockdown on their research progress and mental health. The use of online surveys to assess the scope of mental health problems is particularly appropriate during the Covid-19 outbreak [ 47 ]. The current study has been reviewed by, and received a favourable opinion, from The Open University Human Research Ethics Committee (reference number: HREC/3605/Aristeidou), http://www.open.ac.uk/research/ethics/ . For the recruitment of a diverse audience, we followed a snowball sampling method, forwarding our invitation to PhD student groups in a number of UK-based universities, but also exploited the reach of PhD social media channels and online PhD groups, and we invited academics and respondents to recruit other participants. Vouchers were provided as an incentive for participation to the first 300 respondents. Before completing the survey, the respondents were provided with an online information sheet and were asked to provide their written consent through a digital consent form. They reported their email addresses to be identifiable and contactable for validation, consent issues, potential withdrawal, and incentive processing. The dataset was anonymized on the 30th of August 2020, prior to initiating data analysis.

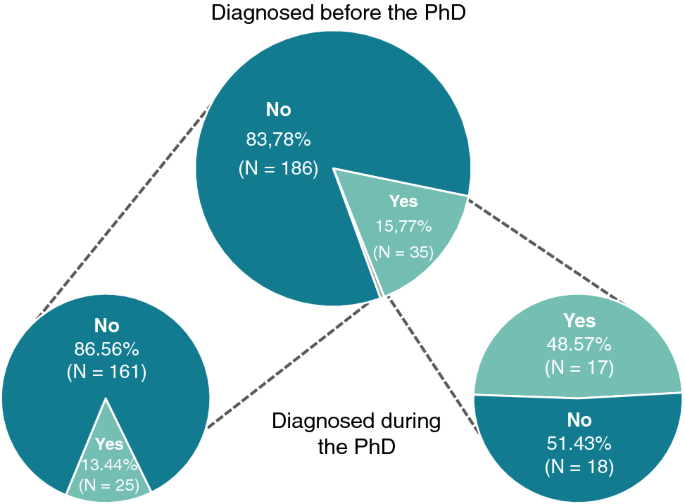

Exclusion criteria included survey respondents who ‘straight-lined’ (chose the same answer option repeatedly), gave inconsistent responses to similar questions, or did not use their institution emails (rendering them unidentifiable). Finally, there were 1790 PhD students in the study from 94 different HE institutions across all four UK nations (England, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales). The majority of the study population (86%) reported that their research progress had been impacted in a negative way. The dataset [ 48 ] included 44.4% male and 55.4% female participants, while the doctoral students in the UK consist of 51% male and 49% female students [ 17 ]. Weighting adjustments were made to correct the sample representativeness. The majority of the survey respondents were 25–34 years old (80.4%), with live-in children (71%). Most respondents (86.7%) were conducting their PhDs full-time, and almost two-thirds (64.4%) were funded by a research council or a charitable body in the UK. At the time of the survey, a large proportion of the survey respondents were in the ‘executing’ phase of their research (i.e., data collection/analysis). Finally, a natural science-related PhD was being pursued by slightly over two-thirds of the respondents (68.8%). According to data sourced from HESA [ 17 ], the likelihood of individuals embarking on a research postgraduate degree at a younger age (such as 18–20) appears to be relatively low. This is evident from the fact that only 90–130 students within this age group register for such programs each year. More details on the demographics and characteristics of the sample can be found in Table 1 and below.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291555.t001

Variables and instruments

Brief cope inventory (bci)..

The BCI [ 49 ] is a 28-item self-report questionnaire designed to measure effective and ineffective ways to cope with a stressful life event, and it is the abbreviated version of the original 60-item COPE inventory developed by [ 42 ]. The BCI has a 4-point Likert scale with options on each item ranging from 0 (I usually do not do this at all) to 3 (I usually do this a lot). Coping in this study is categorised in two overarching coping behaviours, as per Eisenberg et al. [ 50 ]: (a) the approach behaviours that attempt to reduce stress by alleviating the problem directly, which include 12 items related to active coping, positive reframing, planning, acceptance, seeking emotional support, and seeking informational support; and (b) the avoidant coping behaviours that attempt to reduce stress by distancing oneself from the problem, which include 12 items related to denial, substance use, venting, behavioural disengagement, self-distraction, and self-blame. Items that belong to neither overarching behaviour are coping related to humour and religion. These were included in the overall coping score but excluded from the analysis based on the two overarching behaviours. A higher score indicates frequent use of that coping behaviour. Cronbach’s alpha for the BCI was .88. Further, both the approach and avoidant scales have shown very good internal consistency in this sample, with Cronbach’s alpha equal to 0.83 and 0.80, respectively.

Patient health questionnaire eight-item depression scale (PHQ-8).

PHQ-8 [ 57 ] is an eight-item version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). PHQ is a popular measure for assessing depression and is frequently used for PhD mental health (e.g., [ 12 , 51 ]), making it an ideal choice for our study. PHQ-9 has been validated as both a diagnostic and severity measure [ 52 , 53 ] in population-based settings [ 54 ] and self-administered modes [ 55 , 56 ], and it was recently used in a global survey of PhD students’ depression prevalence [ 12 ]. PHQ-8 omits the ninth question that assesses suicidal or self-injurious thoughts, and it was deemed more appropriate for our research because researchers in web-based interviews/surveys are unable to provide adequate interventions remotely. The PHQ-8 items employ a 4-point Likert scale with options on each item ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Then, the scores are summed to give a total score between 0 and 24 points, where 0–4 represent no significant depressive symptoms, 5–9 mild depressive symptoms, 10–13 moderate, 15–19 moderately severe, and 20–24 severe [ 55 ]. Evidence from a large-scale validation study [ 57 ] indicates that a PHQ-8 score ≥ 10 represents clinically significant depression. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for the PHQ-8 was 0.71, indicating a good internal consistency.

Performance satisfaction.

Performance satisfaction is an 8-item self-report scale designed to measure the students’ self-perceived progress in their PhD research, their confidence in being able to finish on time, and their satisfaction. The scale was successfully used in a PhD student well-being study at the university of Groningen [ 24 ] prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. The performance satisfaction 5-point Likert scale responses range from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). The score for each respondent equals the mean score of the 8-item responses. A reliability analysis was carried out on the performance satisfaction scale. Cronbach’s alpha showed the scale to reach acceptable reliability, α = 0.86.

Significant life events Significant Life events is a questionnaire designed to capture whether PhD students had experienced any significant life events in the 12 months prior to the survey. This was successfully used in studying PhD students’ mental health at the university of Groningen [ 24 ] prior to the Covid-19 pandemic research disruption. Events include the death of someone close, severe problems in personal relationships, financial problems, severe illness of oneself or someone close, being in the process of buying a house, getting married, expecting a child, none of these events, and prefer not to say. Significant life events were used as an incident control variable in this study.

Statistical analyses

SPSS (Version 25) was used for statistical analysis. In the first phase, descriptive statistics were used to describe the PHQ-8 Depression and coping behaviours of the sample and the distribution of these three variables among demographics, PhD characteristics, and Covid-19-related circumstances (O1). We used a weighting adjustment for gender to correct the survey representativeness for descriptive analysis; females were given a ‘corrective’ weight of 0.88 and males of 1.15.

In relation to O2, Spearman rank correlations were used to examine the degree of association between all of the 28 coping behaviours and PHQ-8 Depression scores. This finding contributed to our understanding of how individual coping behaviours could relate to lower or higher depressive symptoms.

To assess whether the behaviours significant to our study (i.e., those with a negative or the strongest positive PHQ-8 Depression association) were used more frequently by students of a particular demographic group (O2), we used independent-samples t-test and ANOVA. Before assessing the relationship between our variables, outliers, and groups with a sample size smaller than 15 for each group were removed from the tests (e.g., Gender = other; Funding = partially funded; Likelihood in HE = already employed in academia).

In relation to O3, a binary logistic regression analysis was performed to examine whether Covid-19-related circumstances explain significant depression in PhD students, while controlling for demographics, PhD characteristics, and external incidents. Prior to performing the regression analysis, PHQ-8 Depression score outliers, as well as groups with fewer than 10 events per variable (e.g., gender = other; age = 55–64; Impact reason = mental health), were detected and excluded from the dataset. The dichotomous dependent variable was calculated based on PHQ-8 Depression scores smaller than 10 for non-significant depression, and equal or larger than 10 for significant depression. Associations between Depression in PhD students and the independent variables in our dependency model were estimated using odds ratios (ORs) as produced by the logistic regression procedure in SPSS (Version 25). The ORs were used to explain the strength of the presence or absence of significant depression. Wald tests were used to assess the significance of each predictor. A test of the full model against a constant only model was statistically significant, indicating that the predictors as a set reliably distinguished between PhD students who are having or developing significant depression and those who are not ( Χ 2 (25) = 405.258, p < . 001 ). A Nagelkerke R 2 of .798 indicated a good to substantial relationship between prediction and grouping (68% of variance explained by the proposed model in completion rates). Table 2 presents response percentages about the categorical variables entered in the model, including the two dependent variables (significant depression and non-significant depression).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291555.t002

Exploring depression prevalence and coping behaviours

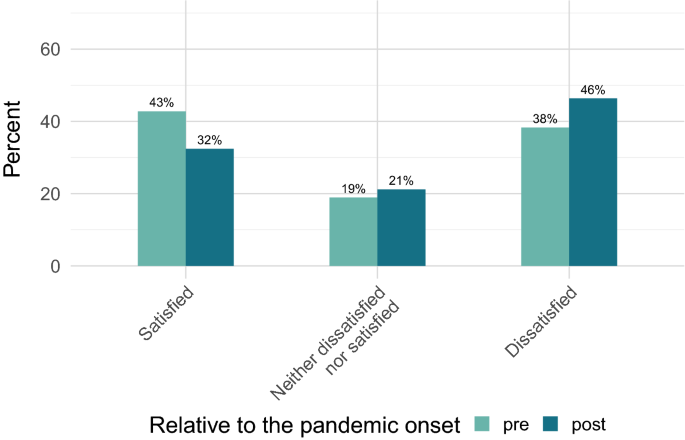

The average PHQ-8 Depression score was 10.13 ( SD = 3.23) on a scale of 0–24 (weighted cases). Importantly, this highlights that the majority of survey respondents are facing moderate depression symptoms ( Fig 1 ). The PHQ-8 item with the highest score, in a range of 0–4, was ‘having trouble to concentrate on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television’ ( M = 1.45; SD = 0.84), and the item with the lowest score was ‘moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed; or the opposite–being so fidgety or restless that have been moving around a lot more than usual’ ( M = 1.10; SD = 0.75). Of the study population, 75% self-reported significant depression (moderate, moderately severe, or severe major).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291555.g001

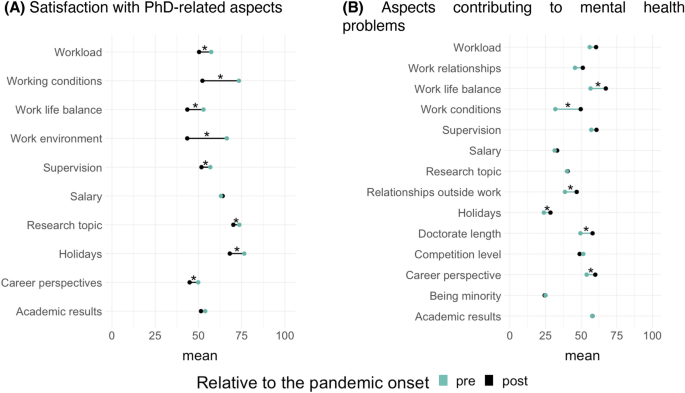

The coping behaviours that the majority of PhD students used in a medium or large amount to overcome the Covid-19 disruption were “accepting the reality of the fact that it has happened” (84%), followed by “thinking hard about what steps to make” (76%) ( Fig 2 ). Both are approaching coping behaviours. Other coping behaviours used to a great extent were “praying or meditating” (73%) , “blaming myself for things that happened” (avoidant) (71%) , and “expressing my negative feelings” (avoidant) (69%). On the other hand, coping behaviours that were used the least were all avoidant ones: “giving up attempting to cope” ( 13%) , “refusing to believe that it has happened” (15%) , “using alcohol or other drugs to make myself feel better” (17%) , and “giving up trying to deal with it” (17%) . Overall, approach coping behaviours were used to a greater extent ( M = 26.43, SD = 5.15) than avoidant coping behaviours ( M = 23.97, SD = 4.90).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291555.g002

The Spearman correlations between coping behaviours and PHQ-8 scores ( Table 3 ), which included outliers, suggested that only two items have significant negative (very weak) associations with depression: Item 15, “getting comfort and understanding from someone” ( r s (1780) = -.107, p < .01); and Item 7, “taking action to try to make the situation better” ( r s (1762) = -.077, p < .01). The majority of the coping behaviours had a significant positive relationship with higher scores in depressive symptoms. The coping behaviours with the largest effect and a moderate to strong association were Item 13, “criticizing myself” ( r s (1762) = .452, p < .01), followed by Item 11 “using alcohol or other drugs to help me go through it” ( r s (1762) = .387, p < .01).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291555.t003

Table 4 shows the relationship among approach and avoidant coping behaviours, and demographics. Our analyses indicated that both approach and avoidant coping behaviours had been significantly used to a greater extent by the female over male PhD students, by students without a live-in partner than those with a live-in partner, and by those without live-in children than those with live-in children. There is no evidence that the students of a particular age group were using avoidant coping more than those of another age group. However, students aged 25–34 were using approach coping behaviours less than other groups, and those aged 45–54 more ( Table 5 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291555.t004

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291555.t005

Our analyses indicated that female PhD students, who had significantly lower PHQ-8 Depression scores, were using Table 3 ‘s Items 15 ( t [1778] = 14.61, p < .001) and Item 7 ( t [480] = 15.11, p < .001) significantly more than male students. Also, those without live-in partners were getting comfort and understanding from someone to a significantly greater extent than those without ( t [702] = 20.09, p < .001). PhD students without live-in children were taking action to try to make the situation better significantly more than those who have them ( t [894] = 25.21, p < .001).

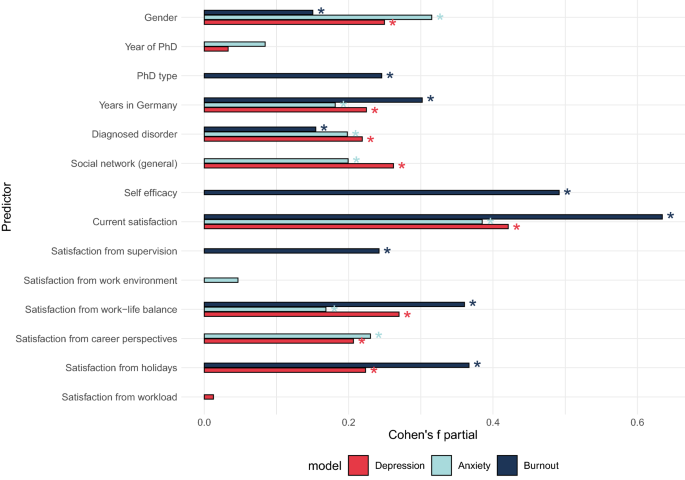

Predictors of depression and relative influence

Covid-19-related circumstances (receiving an extension, impact reasons, and impact results), performance satisfaction, and coping behaviours (approach and avoidant) were entered together as predictors of depression. Demographics (gender, age, live-in partner, and live-in children), PhD characteristics (discipline, PhD phase, PhD mode, funding, interest in HE, and likelihood in HE) and external incidents were used as control variables. Table 6 reports the findings of the analyses.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291555.t006

Prediction success overall was 95.3% (83.1% for not significant depression and 98.0% for significant depression). The Wald criterion demonstrated that not having an extension ( p = .014), having caring responsibilities ( p < .001), and using approach ( p < .001) or avoidant ( p < .001) coping behaviours made significant contributions to prediction. The OR value indicated that in the case that PhD students were not receiving an extension amid the Covid-19 disruption, or they did not know whether they were receiving one yet, they were 5.4 times more likely to experience significant depression. For the impact reason, our findings showed that–compared to those who experienced personal illness–PhD students who had caring responsibilities (e.g., childcare or other) showed slightly lower depressive symptoms (OR = 0.10). The OR for approach and avoidant coping behaviours were 0.13 and 43.73, respectively. This finding indicates that when approach coping is raised by one unit (e.g., +1 to the score), we see evidence for better mental health, while when avoidant coping is raised by one unit, a PhD student is very likely (44 times) to experience significant depression.

Turning to our control variables, PhD students with children in the household and with live-in partners showed significantly higher odds (about 14 and 7 times more, respectively) of having or developing depressive symptoms than those without. The latter can be explained by the fact that 88% of the participants with live-in partners also reported having live-in children. Also, male students were slightly more likely than female students to experience significant depression (with a borderline p-value), but this might be explained by the significantly increased use of coping approaches by female students. This gender-related finding that shows nearly no difference between the two categories slightly differs from Goldstone and Zhang’s model [ 15 ] which highlights a difference between female and male participants’ mental wellbeing. This difference can be explained by the fact that the research instruments used in the two studies were different, as well as the survey period.

Some PhD characteristics that made significant contributions to prediction were the discipline of PhD studies and the interest of students to remain in academia after finishing their PhD projects. The risk of experiencing significant depression in PhD students in social sciences (OR = 9.68) was lower than in students conducting a PhD in natural sciences. In contrast to findings by Levecque et al. [ 9 ], we observed that PhD students expressing a high interest in an academic career were 3.5 times more likely to develop depressive symptoms than those with no or only little interest in remaining in academia. Further, those considering having a high likelihood of remaining in academia were slightly more depressed (OR = 3.73), as well as those who were in the executing phase of their PhD research (OR = 3.33). No differences between funded and self-funded students were detected. Finally, the OR for the external incident variable was 6.13, indicating that for each incident unit (e.g., one more incident), we see evidence for depressive symptoms that are six times worse.

Our study contributes new empirical data and new insights needed to develop knowledge on the effect of university research disruption on the PhD student population. In turn, new knowledge may provide the evidence base for university and research policy.

Exploring mental health and coping behaviours

Our first contribution is to provide empirical estimates for the performance satisfaction, prevalence of mental health problems, and coping behaviours of PhD students during the pandemic-induced research disruption, on the basis of representative data across disciplines and across universities in the UK.

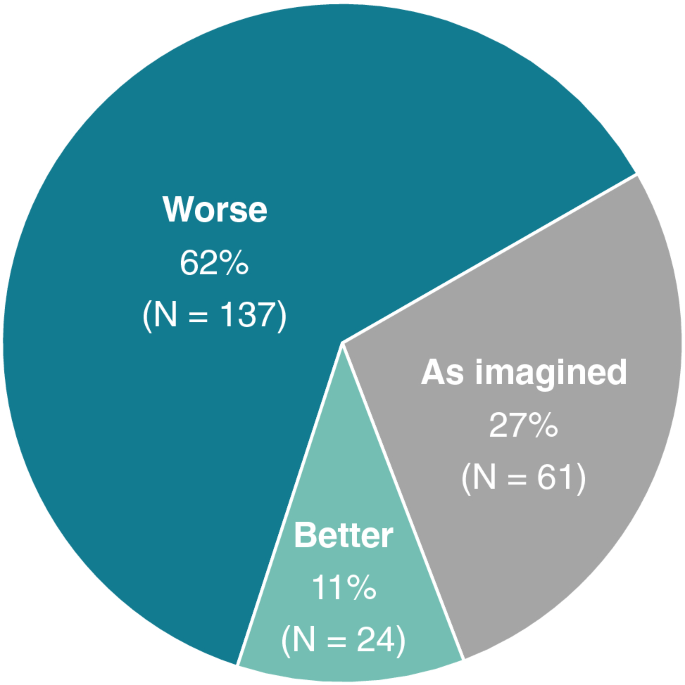

Our findings show that most UK PhD students across universities and disciplines report that their research progress has been affected negatively (86%). By contrast, in pre-pandemic periods, 79% of UK PhD students across Universities and disciplines had indicated excellent research progress [ 11 ]. This shift within the same population is important to reveal because of its potential implications for PhDs’ careers and university research capacity and innovation, as we know that dissatisfaction about the PhD trajectory is tied to negative outcomes such as attrition and delay [ 24 , 28 ], but also to lower productivity [ 58 ].

We found that during the period of severe research disruption caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, 75% of the UK students surveyed from 94 universities and across disciplines self-reported in the moderate-severe range for depression. This is at least three times more compared to the reported prevalence of depression among the general population internationally during the Covid-19 outbreak (16–28%, [ 59 ]). Our findings are also in line with findings in Goldstone and Zhang’s study [ 15 ] on UK postgraduate students’ mental wellbeing during the pandemic, in which 72% of the surveyed students were found to demonstrate possible or probable depression or anxiety.

By adopting widely used standardised questionnaires, our findings provide an accessible benchmark for the comparison with studies that took place among PhD student populations in periods of HE stability (pre-2020), thereby providing the empirical basis to accurately estimate the issue of poor mental health among PhD students during a period of research disruption. Using the same questionnaire as in our survey (PHQ-9) and drawing on a sample of PhD students from multiple universities and across research disciplines, a pre-pandemic global survey reported that 39% of PhD students scored in the moderate-severe range for depression [ 12 ]. Pre-pandemic national surveys of PhD students across institutions and disciplines report similar rates of depression, between 32% (in Belgium, Levecque et al. [ 9 ] and 38% (in the Netherlands, Van der Weijden et al. [ 60 ]. In a pre-pandemic (2018–2019) survey of UK PhD students across 48 universities and disciplines, only 25% reported levels that would indicate probable depression or anxiety [ 11 ]. These comparisons indicate that the prevalence of depression among the UK PhD student population of our study during the pandemic-induced period of research disruption is two-to-three times more than that which was reported in periods of stability for the UK PhD student population, for PhD student populations of other countries, and the global PhD population.

Our findings on PhD students’ mental health and PhD students’ coping advance past literature [ 22 , 23 , 34 ] in two significant ways. First, by using a highly reliable coping measure (COPE), we are able to demonstrate the relationship between coping styles and mental health outcomes in PhD students in a way that allows for comparisons and to build further research in this area. Second, we identify specific coping behaviours amongst the UK PhD students that are associated with lower depression scores and some that have a negative association with depression (i.e., getting comfort and understanding from someone and taking action to try to make the situation better ). Both are ‘coping approach’ behaviours (i.e., attempts to reduce stress by alleviating the problem directly; [ 50 ]). Studies using COPE in other populations have also linked coping-approach behaviours to fewer symptoms of psychological distress [ 45 ], more physical and psychological well-being at work [ 46 ], and an absence of anxiety and depression [ 61 ].

Factors explaining PhD students’ depression

Our second contribution is to explain–within the UK PhD population–whose mental health is more affected by the pandemic-induced research disruption. We find that several factors have a significant impact on PhD students to have or develop mental health issues during a period of research disruption.

Consistent with past research on PhD students’ mental health, our findings reveal the significant influence of their personal lives on poor mental health. The relationships we observed during a period of research disruption, however, differ from those suggested in studies conducted in periods of stability (e.g., [ 9 , 22 , 25 , 26 , 62 ]). We found that PhD students with live-in children or with a live-in partner and PhDs with caring responsibilities are more likely to have or develop significant depression compared to those without. This difference can be explained by the closure of schools that resulted in parents home-schooling their children, a greater demand for devices and the internet in households, and parents going through emotional hardship [ 63 ]. We additionally find six times worse depressive symptoms for each ‘external life incident’ (e.g., childbirth, moving home) that occurred in the PhD students’ lives. A larger number of external incidents were found to be associated with students with live-in partners and students with live-in children, which may explain these as reinforcing negative effects. These new insights explain that–although most of these realities in PhD students’ personal lives existed besides the research disruption—when combined with the research disruption, their mental health can spiral downward.

Our findings also address the role of structural PhD characteristics (PhD discipline and PhD phase) in predicting whether a student might present mental health issues in times of research disruption. We find that in a period of research disruption, the risk of significant depression is higher in the execution phase of the PhD compared to the beginning or extension phases, contrary to Levecque and colleagues’ findings [ 9 ]. Because there is very limited research on the PhD stage and mental health, our findings contribute insights to a broader community of scholars who advocate for the further study of the challenges in each PhD stage discreetly (e.g., [ 32 ]). Furthermore, we find that the risk of experiencing significant depression in PhD students in social sciences was lower than students conducting a PhD in natural sciences. Our survey respondents offered explanations on the role of PhD discipline in mental health during the pandemic in the open text responses. These converge on the fact that natural sciences often require being physically in a laboratory, which is probably unfeasible when university facilities are closed.

In tune with past research on finances and mental health in PhD students [ 9 , 64 ], we found those without funded extensions are more likely to have or develop significant depression (moderate, moderately severe, and severe) compared to those with them. We reveal the size of this association (about 5.5 times more) and link PhD funding extensions to standardized assessments of depression prevalence, thus uniquely providing new evidence for policy scholars.

Implications for research and higher education policy

Our findings show an alarming increase in self-reported depression levels among the UK PhD student population. The long-term mental health impact of Covid-19 may take years to become fully apparent, and managing this impact requires concerted effort not just from the healthcare system at large [ 59 ] but also from the HE sector specifically. With mental illness a cause for PhD student attrition, loss of research capacity and productivity, data from our survey should prompt consideration of immediate intervention strategies.

For research and education policy scholars, our findings contribute directly to the development of evidence-based research and university policies on support for targeted groups of PhD students in times of disruption. Specifically, our findings show that institutional and funder support should not only be in the form of PhD-funded extensions–which are nevertheless shown in our study and other studies (e.g., [ 15 ]) to be very significant. But also, in the form of providing expedited alternatives to the changes evoked by the pandemic for PhD students, such as new and adjusted policies that explicitly consider those PhDs with caring responsibilities, since 77% of our respondents reported that childcare and other caring responsibilities are the reason for dissatisfaction with their PhD progress. If not, the Covid-19 research disruption could erase decades of progress towards equality in academia [ 65 ].

Our main contribution is that we offer insights into how to mitigate mental health consequences for PhD students in times of research disruption. Individual-driven coping behaviours are suggested to be of equal importance to those promoted by the PhD students’ institutions [ 66 ]. In this study, approach coping behaviours were found to associate with lower depression levels, which may eventually contribute to PhD completion. The importance of developing coping mechanisms has also been highlighted in pre-pandemic studies, with, for instance, mothers finding ways to combine academic work and family responsibilities and succeed in both roles [ 38 ]. Still, institutions may play a crucial role in offering training for PhD students on coping and wellbeing through, for instance, a virtual platform to comply with social distancing policies. Such efforts may include mental health support and coping behaviour guidance, so that students are guided on how to successfully deal with disruptions (for example, to avoid avoidant coping behaviours that may lead them to higher levels of depression). Pre-pandemic reforms have previously shown that a well-structured programme and well-timed financial support can facilitate and uphold PhD completion, alongside student efforts [ 35 ]. As the future generation of academics, PhD students would be better equipped to handle the current and future disruptions and better cope with other disruptions in their academic journeys.

Limitations and implications for further research

Although our study has gone some way towards enhancing our understanding of Covid-19-related effects on UK PhD students’ mental health, it is plausible that a number of limitations could have influenced the results obtained. First, while our research attracted a representative number of students from different age groups, PhD modes, phases and funding, there was a very strong presence of students in natural sciences [ 17 ]. Second, as this was a cross-sectional study, we did not follow the UK PhD population longitudinally, and we may not offer insights into the trajectory of the relationships we articulate in our findings. Nevertheless, our adoption of standardized questionnaires allows for a platform for comparisons with past and future research efforts. Third, findings in this survey are based on self-report and may be subject to unconscious biases (e.g., PhD students assessing themselves or the situation inaccurately). Fifth, the research undertaken employed the PHQ-8 with a specific emphasis on assessing aspects related to depression. It is important to acknowledge that while these questionnaires offer valuable insights into depression, they may not comprehensively encompass the broader spectrum of general mental health. Therefore, the findings of the study should be interpreted within the context of its targeted focus on depression, recognizing the potential existence of other dimensions of mental health that were not directly addressed within this research framework. Finally, despite the high percentage of prediction in our findings (80%), additional factors may likely explain variabilities in our study outcomes, such as leadership factors or supervision styles in the 94 UK Universities whose PhD students participated in our survey.

As our study strongly demonstrates, juxtaposing findings from studies conducted during periods of relative HE stability with those conducted during periods of disruption is a fruitful approach for advancing research and university policy. By identifying which insights that would have been invaluable during periods of stability are less so during a period of disruption, scholars can provide significant advancements to existing research and new insights for policy, research and HE leadership.

Conclusions

Our study extends previous research on mental health in the HE sector by considering the dynamics of a severe disruption as opposed to the dynamics of relative stability in PhD mental health and coping behaviours. Drawing on our insights into these interrelationships, we suggest extensions to the literature on PhD students’ mental health, research and university policy. With our findings, HE leaders and policymakers may be better placed to tackle and ultimately overcome this and future research disruptions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the PhD students who committed time for taking part in this study and their responses informed the writing of this paper.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 3. O’Malley B. 180 congressmen support call for US$26bn research support. University World News [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2023 Jan 15]; Available from: https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20200502080814674

- PubMed/NCBI

- 39. Drake KL. Psychology Graduate Student Well-being: The Relationship between Stress, Coping, and Health Outcomes. University of Cincinnati; 2010.

- 40. Pychyl T. Personal projects, subjective well-being and the lives of doctoral students. | CURVE [Internet]. Carleton University; 1995 [cited 2023 Jan 15]. Available from: https://curve.carleton.ca/d330c15c-eeaa-459c-afea-4bf841b7daa0

- 48. Aristeidou M, Aristidou A. PhDMentalHealth_UKDataset [Internet]. The Open University; 2023 [cited 2023 May 10]. Available from: https://ordo.open.ac.uk/articles/dataset/PhDMentalHealth_UKDataset/22794203/0 .

- 65. Malisch JL, Harris BN, Sherrer SM, Lewis KA, Shepherd SL, McCarthy PC, et al. Opinion: In the wake of COVID-19, academia needs new solutions to ensure gender equity [Internet]. Vol. 117, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. National Academy of Sciences; 2020 Jul [cited 2023 Jan 15]. Available from: https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2010636117/-/DCSupplemental .

Managing While and Post-PhD Depression And Anxiety: PhD Student Survival Guide

Embarking on a PhD journey can be as challenging mentally as it is academically. With rising concerns about depression among PhD students, it’s essential to proactively address this issue. How to you manage, and combat depression during and after your PhD journey?

In this post, we explore the practical strategies to combat depression while pursuing doctoral studies.

From engaging in enriching activities outside academia to finding supportive networks, we describe a variety of approaches to help maintain mental well-being, ensuring that the journey towards academic excellence doesn’t come at the cost of your mental health.

How To Manage While and Post-Phd Depression

Why phd students are more likely to experience depression than other students.

The journey of a PhD student is often romanticised as one of intellectual rigour and eventual triumph.

However, beneath this veneer lies a stark reality: PhD students are notably more susceptible to experiencing depression and anxiety.

This can be unfortunately, quite normal in many PhD students’ journey, for several reasons:

Grinding Away, Alone

Imagine being a graduate student, where your day-to-day life is deeply entrenched in research activities. The pressure to consistently produce results and maintain productivity can be overwhelming.

For many, this translates into long hours of isolation, chipping away at one’s sense of wellbeing. The lack of social support, coupled with the solitary nature of research, often leads to feelings of isolation.

Mentors Not Helping Much

The relationship with a mentor can significantly affect depression levels among doctoral researchers. An overly critical mentor or one lacking in supportive guidance can exacerbate feelings of imposter syndrome.

Students often find themselves questioning their capabilities, feeling like they don’t belong in their research areas despite their achievements.

Nature Of Research Itself

Another critical factor is the nature of the research itself. Students in life sciences, for example, may deal with additional stressors unique to their field.

Specific aspects of research, such as the unpredictability of experiments or the ethical dilemmas inherent in some studies, can further contribute to anxiety and depression among PhD students.

Competition Within Grad School

Grad school’s competitive environment also plays a role. PhD students are constantly comparing their progress with peers, which can lead to a mental health crisis if they perceive themselves as falling behind.

This sense of constant competition, coupled with the fear of failure and the stigma around mental health, makes many hesitant to seek help for anxiety or depression.

How To Know If You Are Suffering From Depression While Studying PhD?

If there is one thing about depression, you often do not realise it creeping in. The unique pressures of grad school can subtly transform normal stress into something more insidious.

As a PhD student in academia, you’re often expected to maintain high productivity and engage deeply in your research activities. However, this intense focus can lead to isolation, a key factor contributing to depression and anxiety among doctoral students.

Changes in Emotional And Mental State

You might start noticing changes in your emotional and mental state. Feelings of imposter syndrome, where you constantly doubt your abilities despite evident successes, become frequent.

This is especially true in competitive environments like the Ivy League universities, where the bar is set high. These feelings are often exacerbated by the lack of positive reinforcement from mentors, making you feel like you don’t quite belong, no matter how hard you work.

Lack Of Pleasure From Previously Enjoyable Activities

In doctoral programs, the stressor of overwork is common, but when it leads to a consistent lack of interest or pleasure in activities you once enjoyed, it’s a red flag. This decline in enjoyment extends beyond one’s research and can pervade all aspects of life.

The high rates of depression among PhD students are alarming, yet many continue to suffer in silence, afraid to ask for help or reveal their depression due to the stigma associated with mental health issues in academia.

Losing Social Connections

Another sign is the deterioration of social connections. Graduate student mental health is significantly affected by social support and isolation.

You may find yourself withdrawing from friends and activities, preferring the solitude that ironically feeds into your sense of isolation.

Changes In Appetite And Weight

Changes in appetite and weight can be a significant indicator of depression. As they navigate the demanding PhD study, students might experience fluctuations in their eating habits.

Some may find themselves overeating as a coping mechanism, leading to weight gain. Others might lose their appetite altogether, resulting in noticeable weight loss.

These changes are not just about food; they reflect deeper emotional and mental states.

Such shifts in appetite and weight, especially if sudden or severe, warrant attention as they may signal underlying depression, a common issue in the high-stress environment of PhD studies.

Unhealthy Coping Mechanisms

PhD students grappling with depression often feel immense pressure to excel academically while battling isolation and imposter syndrome. Lacking adequate mental health support, some turn to unhealthy coping mechanisms like substance abuse. These may include:

- Overeating,

- And many more.

These provide temporary relief from overwhelming stress and emotional turmoil. However, such methods can exacerbate their mental health issues, creating a vicious cycle of dependency and further detachment from healthier coping strategies and support systems.

It’s essential for PhD students experiencing depression to recognise these signs and seek professional help. Resources like the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline are very helpful in this regard.

Suicidal Thoughts Or Attempts

Suicidal thoughts or attempts may sound extreme, but they can happen in PhD studies. This is because of the high-pressure environment of PhD studies.

Doctoral students, often grappling with intense academic demands, social isolation, and imposter syndrome, can be susceptible to severe mental health crises.

When the burden becomes unbearable, some may experience thoughts of self-harm or suicide as a way to escape their distress. These thoughts are a stark indicator of deep psychological distress and should never be ignored.

It’s crucial for academic institutions and support networks to provide robust mental health resources and create an environment where students feel safe to seek help and discuss their struggles openly.

How To Prevent From Depression During And After Ph.D?

A PhD student’s experience is often marked by high rates of depression, a concern echoed in studies from universities like the University of California and Arizona State University. If you are embarking on a PhD journey, make sure you are aware of the issue, and develop strategies to cope with the stress, so you do not end up with depression.

Engage With Activities Outside Academia

One effective strategy is engaging in activities outside academia. Diverse interests serve as a lifeline, breaking the monotony and stress of grad school. Some activities you can consider include:

- Social gatherings.

These activities provide a crucial balance. For instance, some students highlighted the positive impact of adopting a pet, which not only offered companionship but also a reason to step outside and engage with the world.

Seek A Supportive Mentor

The role of a supportive mentor cannot be overstated. A mentor who adopts a ‘yes and’ approach rather than being overly critical can significantly boost a doctoral researcher’s morale.

This positive reinforcement fosters a healthier research environment, essential for good mental health.

Stay Active Physically

Physical exercise is another key element. Regular exercise has been shown to help cope with symptoms of moderate to severe depression. It’s a natural stress reliever, improving mood and enhancing overall wellbeing. Any physical workout can work here, including:

- Brisk walking

- Swimming, or

- Gym sessions.

Seek Positive Environment

Importantly, the graduate program environment plays a critical role. Creating a community where students feel comfortable to reveal their depression or seek help is vital.

Whether it’s through formal support groups or informal peer networks, building a sense of belonging and understanding can mitigate feelings of isolation and imposter syndrome.

This may be important, especially in the earlier stage when you look and apply to universities study PhD . When possible, talk to past students and see how are the environment, and how supportive the university is.

Choose the right university with the right support ensures you keep depression at bay, and graduate on time too.

Remember You Have The Power

Lastly, acknowledging the power of choice is empowering. Understanding that continuing with a PhD is a choice, not an obligation. If things become too bad, there is always an option to seek a deferment, pause. You can also quit your studies too.

Work on fixing your mental state, and recover from depression first, before deciding again if you want to take on Ph.D studies again. There is no point continuing to push yourself, only to expose yourself to self-harm, and even suicide.

Wrapping Up: PhD Does Not Need To Ruin You

Combating depression during PhD studies requires a holistic approach. Engaging in diverse activities, seeking supportive mentors, staying physically active, choosing positive environments, and recognising one’s power to make choices are all crucial.

These strategies collectively contribute to a healthier mental state, reducing the risk of depression. Remember, prioritising your mental well-being is just as important as academic success. This helps to ensure you having a more fulfilling and sustainable journey through your PhD studies.

Dr Andrew Stapleton has a Masters and PhD in Chemistry from the UK and Australia. He has many years of research experience and has worked as a Postdoctoral Fellow and Associate at a number of Universities. Although having secured funding for his own research, he left academia to help others with his YouTube channel all about the inner workings of academia and how to make it work for you.

Thank you for visiting Academia Insider.

We are here to help you navigate Academia as painlessly as possible. We are supported by our readers and by visiting you are helping us earn a small amount through ads and affiliate revenue - Thank you!

2024 © Academia Insider

The Savvy Scientist

Experiences of a London PhD student and beyond

PhD Burnout: Managing Energy, Stress, Anxiety & Your Mental Health

PhDs are renowned for being stressful and when you add a global pandemic into the mix it’s no surprise that many students are struggling with their mental health. Unfortunately this can often lead to PhD fatigue which may eventually lead to burnout.

In this post we’ll explore what academic burnout is and how it comes about, then discuss some tips I picked up for managing mental health during my own PhD.

Please note that I am by no means an expert in this area. I’ve worked in seven different labs before, during and after my PhD so I have a fair idea of research stress but even so, I don’t have all the answers.

If you’re feeling burnt out or depressed and finding the pressure too much, please reach out to friends and family or give the Samaritans a call to talk things through.

Note – This post, and its follow on about maintaining PhD motivation were inspired by a reader who asked for recommendations on dealing with PhD fatigue. I love hearing from all of you, so if you have any ideas for topics which you, or others, could find useful please do let me know either in the comments section below or by getting in contact . Or just pop me a message to say hi. 🙂

This post is part of my PhD mindset series, you can check out the full series below:

- PhD Burnout: Managing Energy, Stress, Anxiety & Your Mental Health (this part!)

- PhD Motivation: How to Stay Driven From Cover Letter to Completion

- How to Stop Procrastinating and Start Studying

What is PhD Burnout?

Whenever I’ve gone anywhere near social media relating to PhDs I see overwhelmed PhD students who are some combination of overwhelmed, de-energised or depressed.

Specifically I often see Americans talking about the importance of talking through their PhD difficulties with a therapist, which I find a little alarming. It’s great to seek help but even better to avoid the need in the first place.

Sadly, none of this is unusual. As this survey shows, depression is common for PhD students and of note: at higher levels than for working professionals.

All of these feelings can be connected to academic burnout.

The World Health Organisation classifies burnout as a syndrome with symptoms of:

– Feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; – Increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; – Reduced professional efficacy. Symptoms of burnout as classified by the WHO. Source .

This often leads to students falling completely out of love with the topic they decided to spend years of their life researching!

The pandemic has added extra pressures and constraints which can make it even more difficult to have a well balanced and positive PhD experience. Therefore it is more important than ever to take care of yourself, so that not only can you continue to make progress in your project but also ensure you stay healthy.

What are the Stages of Burnout?

Psychologists Herbert Freudenberger and Gail North developed a 12 stage model of burnout. The following graphic by The Present Psychologist does a great job at conveying each of these.

I don’t know about you, but I can personally identify with several of the stages and it’s scary to see how they can potentially lead down a path to complete mental and physical burnout. I also think it’s interesting that neglecting needs (stage 3) happens so early on. If you check in with yourself regularly you can hopefully halt your burnout journey at that point.

PhDs can be tough but burnout isn’t an inevitability. Here are a few suggestions for how you can look after your mental health and avoid academic burnout.

Overcoming PhD Burnout

Manage your energy levels, maintaining energy levels day to day.

- Eat well and eat regularly. Try to avoid nutritionless high sugar foods which can play havoc with your energy levels. Instead aim for low GI food . Maybe I’m just getting old but I really do recommend eating some fruit and veg. My favourite book of 2021, How Not to Die: Discover the Foods Scientifically Proven to Prevent and Reduce Disease , is well worth a read. Not a fan of veggies? Either disguise them or at least eat some fruit such as apples and bananas. Sliced apple with some peanut butter is a delicious and nutritious low GI snack. Check out my series of posts on cooking nutritious meals on a budget.

- Get enough sleep. It doesn’t take PhD-level research to realise that you need to rest properly if you want to avoid becoming exhausted! How much sleep someone needs to feel well-rested varies person to person, so I won’t prescribe that you get a specific amount, but 6-9 hours is the range typically recommended. Personally, I take getting enough sleep very seriously and try to get a minimum of 8 hours.

A side note on caffeine consumption: Do PhD students need caffeine to survive?

In a word, no!

Although a culture of caffeine consumption goes hand in hand with intense work, PhD students certainly don’t need caffeine to survive. How do I know? I didn’t have any at all during my own PhD. In fact, I wrote a whole post about it .

By all means consume as much caffeine as you want, just know that it doesn’t have to be a prerequisite for successfully completing a PhD.

Maintaining energy throughout your whole PhD

- Pace yourself. As I mention later in the post I strongly recommend treating your PhD like a normal full-time job. This means only working 40 hours per week, Monday to Friday. Doing so could help realign your stress, anxiety and depression levels with comparatively less-depressed professional workers . There will of course be times when this isn’t possible and you’ll need to work longer hours to make a certain deadline. But working long hours should not be the norm. It’s good to try and balance the workload as best you can across the whole of your PhD. For instance, I often encourage people to start writing papers earlier than they think as these can later become chapters in your thesis. It’s things like this that can help you avoid excess stress in your final year.

- Take time off to recharge. All work and no play makes for an exhausted PhD student! Make the most of opportunities to get involved with extracurricular activities (often at a discount!). I wrote a whole post about making the most of opportunities during your PhD . PhD students should have time for a social life, again I’ve written about that . Also give yourself permission to take time-off day to day for self care, whether that’s to go for a walk in nature, meet friends or binge-watch a show on Netflix. Even within a single working day I often find I’m far more efficient when I break up my work into chunks and allow myself to take time off in-between. This is also a good way to avoid procrastination!

Reduce Stress and Anxiety

During your PhD there will inevitably be times of stress. Your experiments may not be going as planned, deadlines may be coming up fast or you may find yourself pushed too far outside of your comfort zone. But if you manage your response well you’ll hopefully be able to avoid PhD burnout. I’ll say it again: stress does not need to lead to burnout!

Everyone is unique in terms of what works for them so I’d recommend writing down a list of what you find helpful when you feel stressed, anxious or sad and then you can refer to it when you next experience that feeling.

I’ve created a mental health reminders print-out to refer to when times get tough. It’s available now in the resources library (subscribe for free to get the password!).

Below are a few general suggestions to avoid PhD burnout which work for me and you may find helpful.

- Exercise. When you’re feeling down it can be tough to motivate yourself to go and exercise but I always feel much better for it afterwards. When we exercise it helps our body to adapt at dealing with stress, so getting into a good habit can work wonders for both your mental and physical health. Why not see if your uni has any unusual sports or activities you could try? I tried scuba diving and surfing while at Imperial! But remember, exercise doesn’t need to be difficult. It could just involve going for a walk around the block at lunch or taking the stairs rather than the lift.

- Cook / Bake. I appreciate that for many people cooking can be anything but relaxing, so if you don’t enjoy the pressure of cooking an actual meal perhaps give baking a go. Personally I really enjoy putting a podcast on and making food. Pinterest and Youtube can be great visual places to find new recipes.

- Let your mind relax. Switching off is a skill and I’ve found meditation a great way to help clear my mind. It’s amazing how noticeably different I can feel afterwards, having not previously been aware of how many thoughts were buzzing around! Yoga can also be another good way to relax and be present in the moment. My partner and I have been working our way through 30 Days of Yoga with Adriene on Youtube and I’d recommend it as a good way to ease yourself in. As well as being great for your mind, yoga also ticks the box for exercise!

- Read a book. I’ve previously written about the benefits of reading fiction * and I still believe it’s one of the best ways to relax. Reading allows you to immerse yourself in a different world and it’s a great way to entertain yourself during a commute.

* Wondering how I got something published in Science ? Read my guide here .

Talk It Through

- Meet with your supervisor. Don’t suffer in silence, if you’re finding yourself struggling or burned out raise this with your supervisor and they should be able to work with you to find ways to reduce the pressure. This may involve you taking some time off, delegating some of your workload, suggesting an alternative course of action or signposting you to services your university offers.

Also remember that facing PhD-related challenges can be common. I wrote a whole post about mine in case you want to cheer yourself up! We can’t control everything we encounter, but we can control our response.

A free self-care checklist is also now available in the resources library , providing ideas to stay healthy and avoid PhD burnout.

Top Tips for Avoiding PhD Burnout

On top of everything we’ve covered in the sections above, here are a few overarching tips which I think could help you to avoid PhD burnout:

- Work sensible hours . You shouldn’t feel under pressure from your supervisor or anyone else to be pulling crazy hours on a regular basis. Even if you adore your project it isn’t healthy to be forfeiting other aspects of your life such as food, sleep and friends. As a starting point I suggest treating your PhD as a 9-5 job. About a year into my PhD I shared how many hours I was working .

- Reduce your use of social media. If you feel like social media could be having a negative impact on your mental health, why not try having a break from it?

- Do things outside of your PhD . Bonus points if this includes spending time outdoors, getting exercise or spending time with friends. Basically, make sure the PhD isn’t the only thing occupying both your mental and physical ife.

- Regularly check in on how you’re feeling. If you wait until you’re truly burnt out before seeking help, it is likely to take you a long time to recover and you may even feel that dropping out is your only option. While that can be a completely valid choice I would strongly suggest to check in with yourself on a regular basis and speak to someone early on (be that your supervisor, or a friend or family member) if you find yourself struggling.

I really hope that this post has been useful for you. Nothing is more important than your mental health and PhD burnout can really disrupt that. If you’ve got any comments or suggestions which you think other PhD scholars could find useful please feel free to share them in the comments section below.

You can subscribe for more content here:

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Related Posts

How to Master Data Management in Research

25th April 2024 27th April 2024

Thesis Title: Examples and Suggestions from a PhD Grad

23rd February 2024 23rd February 2024

How to Stay Healthy as a Student

25th January 2024 25th January 2024

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

PhD students’ mental health is poor and the pandemic made it worse – but there are coping strategies that can help

Senior Lecturer in Technology Enhanced Learning, The Open University

Assistant Professor in Strategy and Entrepreneurship, UCL

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University College London and The Open University provide funding as founding partners of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

A pre-pandemic study on PhD students’ mental health showed that they often struggle with such issues. Financial insecurity and feelings of isolation can be among the factors affecting students’ wellbeing.

The pandemic made the situation worse. We carried out research that looked into the impact of the pandemic on PhD students, surveying 1,780 students in summer 2020. We asked them about their mental health, the methods they used to cope and their satisfaction with their progress in their doctoral study.

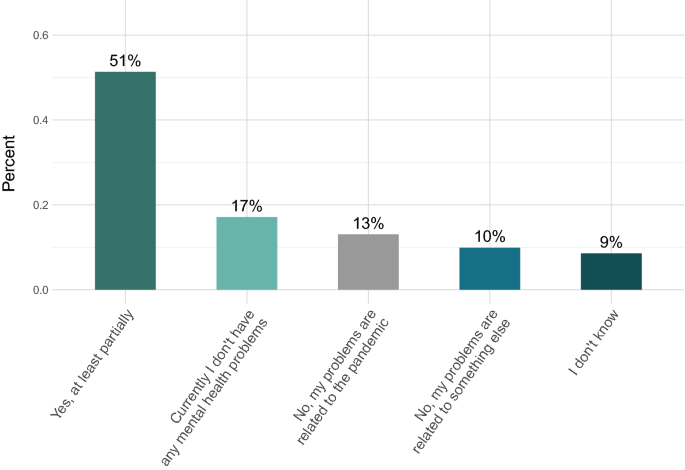

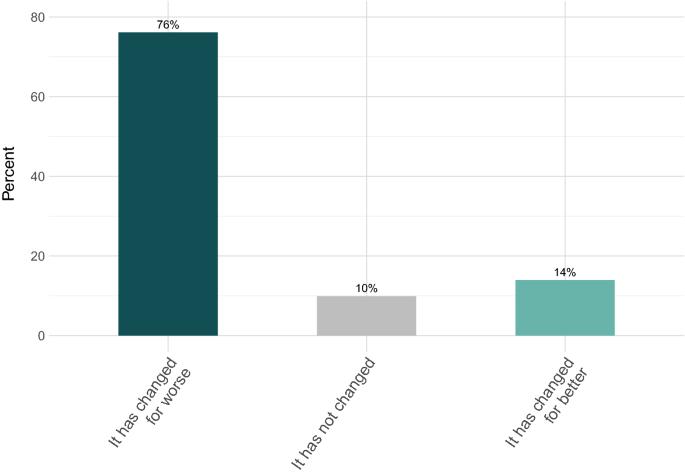

Unsurprisingly, the lockdown in summer 2020 affected the ability to study for many. We found that 86% of the UK PhD students we surveyed reported a negative impact on their research progress.

But, alarmingly, 75% reported experiencing moderate to severe depression. This is a rate significantly higher than that observed in the general population and pre-pandemic PhD student cohorts .

Risk of depression

Our findings suggested an increased risk of depression among those in the research-heavy stage of their PhD – for example during data collection or laboratory experiments. This was in contrast to those in the initial stages, or who were nearing the end of their PhD and writing up their research. The data collection stage was more likely to have been disrupted by the pandemic.

Our research also showed that PhD students with caring responsibilities faced a greatly increased risk of depression. In our our study , we found that PhD students with childcare responsibilities were 14 times more likely to develop depressive symptoms than PhD students without children.

This does align with findings on people in the general UK population with childcare responsibilities during the pandemic. Adults with childcare responsibilities were 1.4 times more likely to develop depression or anxiety compared to their counterparts without children or childcare duties.

It was also interesting to find that PhD students facing the disruption caused by the pandemic who did not receive an extension – extra financial support and time beyond the expected funding period – or were uncertain about whether they would receive an extension at the time of our study, were 5.4 times more likely to experience significant depression.

Our research also used a questionnaire designed to measure effective and ineffective ways to cope with stressful life events. We used this to look at which coping skills – strategies to deal with challenges and difficult situations — used by PhD students were associated with lower depression levels. These “good” strategies included “getting comfort and understanding from someone” and “taking action to try to make the situation better”.

Interestingly, female PhD students, who were slightly less likely than men to experience significant depression, showed a greater tendency to use good coping approaches compared to their counterparts. Specifically, they favoured the above two coping strategies that are associated with lower levels of depression.

On the other hand, certain coping strategies were associated with higher depression levels. Prominent among these were self-critical tendencies and the use of substances like alcohol or drugs to cope with challenging situations.

A supportive environment

Creating a supportive environment is not solely the responsibility of individual students or academic advisors. Universities and funding bodies must play a proactive role in mitigating the challenges faced by PhD students.

By taking proactive steps, universities could create a more supportive environment for their students and help to ensure their success.