Essay on Pirates

Students are often asked to write an essay on Pirates in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Pirates

Who were pirates.

Pirates were people who attacked ships at sea. Long ago, they searched for treasure and took it by force. They lived a life of adventure and danger, sailing across oceans.

Pirate Ships

Pirate ships were their homes. These ships were fast and easy to steer. Pirates used them to chase and rob other ships. They had flags with skull designs.

Pirate Life

Life as a pirate was tough. They had strict rules and shared everything. Pirates worked together but could be punished for breaking rules.

Famous Pirates

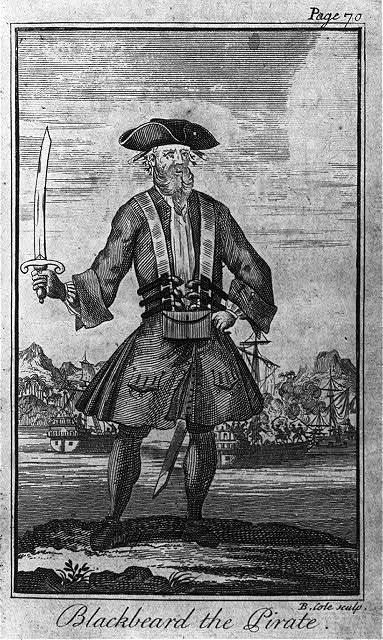

Some pirates became famous, like Blackbeard and Anne Bonny. Stories and movies often tell about their wild lives and treasure hunts.

250 Words Essay on Pirates

Pirates were sailors who attacked other ships and stole from them. They lived many years ago, and their stories are still famous today. They sailed the seas, looking for boats to rob, and they didn’t follow the rules. Pirates are known for their love of treasure, especially gold and jewels.

The Pirate Ship

The pirate ship was their home and their way to travel across the ocean. It was also their main tool for attacking other ships. These ships were fast and could move quickly to catch up with the ships they wanted to steal from. The most famous pirate flag had a skull and bones on it. When other sailors saw this flag, they knew pirates were coming.

Being a pirate was not easy. The sea was often rough, and the work was hard. Pirates had to be strong and brave. They also had to be good at working as a team to sail their ship and fight battles. Sometimes, they would get hurt or even lose their lives while trying to take over other ships.

Pirates in Stories

In books and movies, pirates are often shown as exciting and adventurous. They search for hidden treasure and explore unknown islands. Even though they were not good people, their stories can be thrilling. We should remember that real pirates were thieves and could be very dangerous. But in stories, they take us on wild adventures across the seas.

500 Words Essay on Pirates

Pirates were sailors who attacked other ships and stole from them. They lived many years ago, mostly during a time we call the ‘Golden Age of Piracy,’ which was between the 1650s and the 1730s. These sea robbers would take gold, silver, and other valuable things from the ships they captured. They sailed in their own ships, often with skull and crossbones flags, which were known as the Jolly Roger.

Pirate Ships and Life at Sea

Pirate ships were not like the big navy ships of countries. They were often smaller and faster, which helped them catch up to the ships they wanted to rob. Life on a pirate ship was tough. Pirates had to deal with storms, get food and fresh water, and keep the ship in good shape. Unlike navy sailors, pirates had their own rules and chose their own leaders. The captain had to be strong and smart to keep the crew happy.

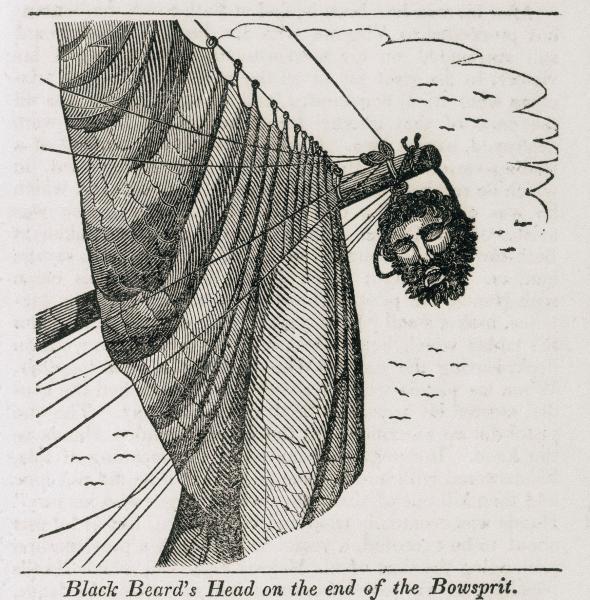

Some pirates became very famous and are still talked about today. Blackbeard, whose real name was Edward Teach, was known for his fearsome look and for putting slow-burning fuses in his beard during battles to scare his enemies. Anne Bonny and Mary Read were women who dressed as men to become pirates, which was rare because most pirates were men. These famous pirates are often shown in movies and books, making them seem exciting and adventurous.

The Pirate Code

Pirates had their own set of rules called the ‘Pirate Code.’ These rules decided how they would share the stolen goods and how they should treat each other. If someone broke the rules, they could be left on an island or punished in other ways. The Pirate Code was not the same on every ship, but it helped keep order among a group of people who were often seen as outlaws.

The End of the Golden Age of Piracy

Piracy became less common when countries started to fight back more strongly against pirates. They sent out navy ships to chase and capture them. Also, as trade between countries grew, it became more important to keep the seas safe for merchant ships. By the 1730s, many of the famous pirates were caught or had stopped being pirates, which marked the end of the Golden Age of Piracy.

Pirates in Popular Culture

Today, pirates are often shown in movies, books, and TV shows. They are usually shown as exciting and daring characters, searching for treasure and having adventures. This picture of pirates is more fun and less scary than what real pirates were like. But it’s important to remember that real pirates were thieves at sea and could be very dangerous.

In conclusion, pirates have a rich history that is both interesting and a bit scary. They were thieves on the sea, living by their own rules and often causing trouble for ships carrying valuable goods. While the Golden Age of Piracy is long over, the stories of pirates continue to capture the imaginations of people everywhere, especially in movies and books.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Honey

- Essay on Picnic At Beach

- Essay on Hong Kong Disneyland

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Divisions and Offices

- Grants Search

- Manage Your Award

- NEH's Application Review Process

- Professional Development

- Grantee Communications Toolkit

- NEH Virtual Grant Workshops

- Awards & Honors

- American Tapestry

- Humanities Magazine

- NEH Resources for Native Communities

- Search Our Work

- Office of Communications

- Office of Congressional Affairs

- Office of Data and Evaluation

- Budget / Performance

- Contact NEH

- Equal Employment Opportunity

- Human Resources

- Information Quality

- National Council on the Humanities

- Office of the Inspector General

- Privacy Program

- State and Jurisdictional Humanities Councils

- Office of the Chair

- NEH-DOI Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Partnership

- NEH Equity Action Plan

- GovDelivery

A Lot of What Is Known about Pirates Is Not True, and a Lot of What Is True Is Not Known.

The pirate next door..

Howard Pyle / DoverPictura

In 1701, in Middletown, New Jersey, Moses Butterworth languished in a jail, accused of piracy. Like many young men based in England or her colonies, he had joined a crew that sailed the Indian Ocean intent on plundering ships of the Muslim Mughal Empire. Throughout the 1690s, these pirates marauded vessels laden with gold, jewels, silk, and calico on pilgrimage toward Mecca. After achieving great success, many of these men sailed back into the Atlantic via Madagascar to the North American seaboard, where they quietly disembarked in Charleston, Philadelphia, New Jersey, New York City, Newport, and Boston, and made themselves at home.

When Butterworth was captured, he admitted to authorities that he had served under the notorious Captain William Kidd, arriving with him in Boston before making his way to New Jersey. This would seem quite damning. Governor Andrew Hamilton and his entourage rushed to Monmouth County Court to quickly try Butterworth for his crimes. But the swashbuckling Butterworth was not without supporters.

In a surprising turn of events, Samuel Willet, a local leader, sent a drummer, Thomas Johnson, to sound the alarm and gather a company of men armed with guns and clubs to attack the courthouse. One report estimated the crowd at over a hundred furious East Jersey residents. The shouts of the men, along with the “Drum beating,” made it impossible to examine Butterworth and ask him about his financial and social relationships with the local Monmouth gentry.

Armed with clubs, locals Benjamin and Richard Borden freed Butterworth from the colonial authorities. “Commanding ye Kings peace to be keept,” the judge and sheriff drew their swords and injured both Bordens in the scuffle. Soon, however, the judge and sheriff were beaten back by the crowd, which succeeded in taking Butterworth away. The mob then seized Hamilton, his followers, and the sheriff, taking them prisoner in Butterworth’s place.

A witness claimed this was not a spontaneous uprising but “a Design for some Considerable time past,” as the ringleaders had kept “a pyratt in their houses and threatened any that will offer to seize him.”

Governor Hamilton had felt that his life was in danger. Had the Bordens been killed in the melee, he said, the mob would have murdered him. As it was, he was confined for four days until Butterworth was free and clear.

Jailbreaks and riots in support of alleged pirates were common throughout the British Empire during the late seventeenth century. Local political leaders openly protected men who committed acts of piracy against powers that were nominally allied or at peace with England. In large part, these leaders were protecting their own hides: Colonists wanted to prevent depositions proving that they had harbored pirates or purchased their goods. Some of the instigators were fathers-in-law of pirates.

There were less materialist reasons, too, why otherwise upstanding members of the community rebelled in support of sea marauders. Many colonists feared that crack-downs on piracy masked darker intentions to impose royal authority, set up admiralty courts without juries of one’s peers, or even force the establishment of the Anglican Church. Openly helping a pirate escape jail was also a way of protesting policies that interfered with the trade in bullion, slaves, and luxury items such as silk and calico from the Indian Ocean.

These repeated acts of rebellion against royal authorities in support of men who had committed blatant criminal acts inspired me to spend about ten years researching pirates, work that resulted in my book, Pirate Nests and the Rise of the British Empire, 1570–1740 . In it, I analyzed the rise and fall of international piracy from the perspective of colonial hinterlands, from the inception of England’s burgeoning empire to its administrative consolidation. While traditionally depicted as swashbuckling adventurers on the high seas, pirates played a crucial role on land, contributing to the commercial development and economic infrastructure of port towns in colonial America.

Pirates could be found in nearly every Atlantic port city. But only particular locations became known as “pirate nests,” a pejorative term used by royalists and customs officials. Many of the most notorious pirates began their careers in these ports. Others established even deeper ties by settling in these cities and becoming respected members of the local elite. Instead of the snarling drunken fiends that parade through children’s books, these pirates spent their booty on pigs and chickens, hoping to live a more placid and financially secure life on land.

I was wholly uninterested in piracy as a child. I never dressed as a pirate on Halloween or even read pirate books. I went to graduate school at Harvard, intending to write about fatherhood in early America. In my third year, I presented to colleagues a 30-page essay that I hoped would be a chapter of my dissertation.

The paper was about William Harris, one of the first settlers of Rhode Island, who accumulated a massive estate through shrewd business tactics and slick legal dealings. A Puritan, Harris styled himself as an Abraham of the New World who would people a New Canaan. He composed a will that went to seven generations. In 1680, however, the elderly man was sailing toward London when Algerian pirates captured his vessel.

In the central market of the great walled city of Algiers, Harris was sold into slavery to a wealthy merchant. The once powerful man sent pitiful letters to Rhode Island, begging friends to ransom him and asking his wife to sell parts of his estate. He pleaded, “If you fail me of the said sum and said time it is most like to be the loss of my life, he [my captor] is so Cruel and Covetous. I live on bread and water.” After nearly two years of abject slavery, Harris became one of the lucky few to be ransomed. He made his way back to London, where, after a few weeks on Christian land, the exhausted patriarch died.

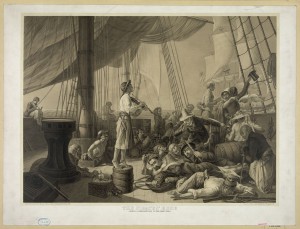

The Anglo-Dutch fleet in the Bay of Algiers, which thrived on an economy of piracy in the 17th century.

Wikimedia / Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The Algiers episode was marginal to my larger points about fatherhood. But, as the discussion went around the room, all that anyone wanted to talk about was pirates. This was a few years before Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl became a worldwide sensation. One colleague working on Atlantic families had noticed that locals in South Carolina seemed strangely unsurprised when pirates came ashore in the 1680s. Another colleague came upon a pirate who arrived in Newport in the 1690s, bought land, settled down, and became a customs official. This more-than-passing interest in pirates, as opposed to fathers, left me quite concerned. I had already taken my qualifying exams. I knew nothing about piracy. And since few scholars had written about piracy, I assumed it was not an important topic. Yet there it was, boarding the ship of my research agenda without permission.

Distraught, I cut a deal with my adviser that I would spend a month in the archives, examining government records and official correspondences to find out more. Sure enough, pirates were everywhere. But they were not who we thought they were. They were not anarchistic, antisocial maniacs. At least not in the seventeenth century. Like Moses Butterworth, many were welcome in colonial communities. They married local women, and bought land and livestock. Pirate James Brown even married the daughter of the governor of Pennsylvania and was appointed to the Pennsylvania House of Assembly.

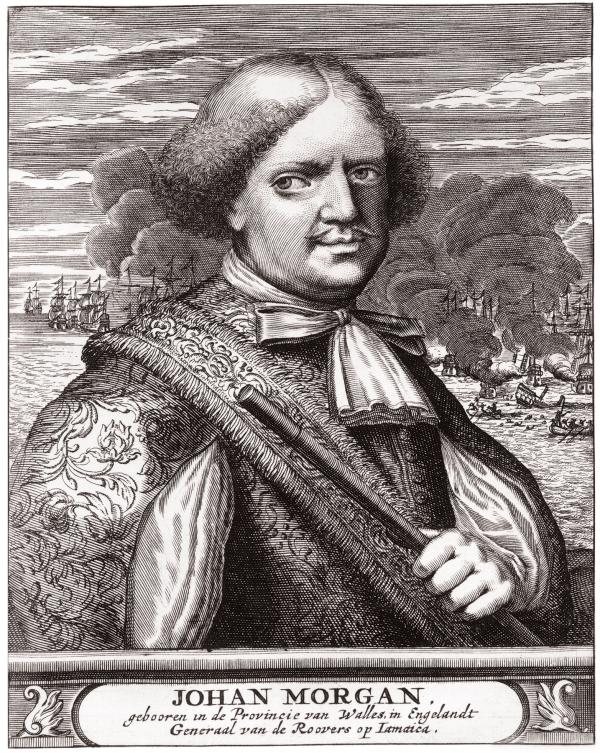

Notorious buccaneer Sir Henry Morgan, shown in a Dutch engraving, raided Spain's Caribbean colonies from his base in Jamaica.

Private collection / Bridgeman Images

Pirates, it seemed, could be civil, neighborly, and law-abiding. Why hadn’t this been noticed before? I chalk it up to specialization. By focusing so closely on their own areas of expertise, historians had overlooked how piracy permeated colonial life.

Piracy has not achieved its rightful place in the narrative of American history precisely because it was so familiar to the people of the English-speaking world of the seventeenth century. In the early days of the colonies, pirate attacks were considered a commonplace, inevitable feature of the maritime world, and noted only as entertaining asides. The prevalence of piracy in children’s stories and blockbuster movies has likely also made it difficult for historians to study the topic without romanticism. This was where my childhood disinterest in piracy paid off. I embarked on my research as a historian rather than as a fan.

Historians and fiction writers alike have portrayed pirates as inherently removed from civilized society. Hubert Deschamps in his 1949 Les pirates à Madagascar voiced what has become a standard trope: “[Pirates] were a unique race, born of the sea and of a brutal dream, a free people, detached from other human societies and from the future, without children and without old people, without homes and without cemeteries, without hope but not without audacity, a people for whom atrocity was a career choice and death a certitude of the day after tomorrow.” Seventeenth-century lawyers defined pirates, in the words of Admiralty judge Sir Leoline Jenkins, as hostis humani generis , or “Enemies not of one Nation or of one Sort of People only, but of all mankind.” Since pirates lacked the legal protection of any prince, nation, or body of law, “Every Body is commissioned and is to be armed against them, as against Rebels and Traytors, to subdue and root them out.”

Contemporary historians have tended to use pirates for their own ends, depicting them as rebels against convention. Their pirates critique early modern capitalism and challenge oppressive sexual norms. They are cast as proto-feminists or supporters of homosocial utopias. They challenge oppressive social hierarchies by flaunting social graces or wearing flamboyant clothing above their social stations. They subvert oppressive notions of race, citing the presence of black crew members as evidence of race blindness. Moses Butterworth, however, did none of these things.

A pirate faces hanging by the River Thames in the eighteenth century.

Private collection / Peter Newark Historical Pictures / Bridgeman Images

The true rebels were leaders like Samuel Willet, establishment figures on land who led riots against crown authority. It was the higher reaches of colonial society, from governors to merchants, who supported global piracy, not some underclass or proto proletariat.

Popular culture has invested heavily in the image of pirates as anarchists who speak in colorful language and dress in attire recognizable to any five-year-old. In fact, what we imagine pirates to look and sound like matches only one decade of history: 1716 to 1726. Before that, piracy consisted of a spectrum of activities from the heroic to the maniacal. Many historians, like many pirate fans, write about piracy as a static phenomenon. This is the basis of popular events like International Talk Like a Pirate Day (September 19) or the costume worn by Jack Sparrow. When asked if these common tropes are true, I give a typical historian’s answer: It depends on when and where.

For the period before the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, it makes more sense to talk about a sailor who commits piracy, rather than an actual “pirate.” Imagine a ten-year-old boy caught stealing candy from the store. If he learned his lesson, it would be ludicrous to call him a “thief” when he reached adulthood. If he goes on to get a PhD and becomes a respectable historian, it makes more sense to call him “professor.” Certainly there were flamboyant captains of legendary status who would never consider legitimate commerce as a way of life. But most sought one large prize and hoped to use their plunder to join the middling to upper echelons of colonial society.

One reason piracy was often an act or a phase, and not a way of life, was simply because humans have not evolved to live on the sea. The sea is a hostile place, offering few of the pleasures of terrestrial society. Pirates needed to clean and repair their ships, collect wood and water, gather crews, obtain paperwork, fence their goods, or obtain sexual gratification. Simply put, what is the value of silver and gold in the middle of the ocean? Why would someone risk his life in a hostile maritime world if there was no chance he could actually spend his booty?

“A Merry Life and a Short One” was not the motto of most pirates of the late seventeenth century. Until the 1710s, English pirates almost always had somewhere to go to spend their money, either for a few days or to settle down for good. The British National Archives holds a petition from 48 wives of known pirates, begging the crown to pardon their husbands so they could return home to care for their families. Returning to London was not an option for most sea rovers, but a life in the American colonies offered the closest proxy.

Robert Rich, Second Earl of Warwick, who was instrumental to the development of the American colonies and commanded a fleet of privateers, was painted by Anthony van Dyck around 1632.

© Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY

Support of piracy on the peripheries of the British Empire dates to the first forays of English sea captains overseas. Pirate Nests begins in Elizabethan England with the active protection of piracy by port communities in Devon and Cornwall. The ascension of James I coincided with the migration of a plunder economy from England to farther shores. Puritan communities in Ireland, and soon the fledgling colonies of Jamestown, Bermuda, New Plymouth, and Boston all supported illicit sea marauders. Upon the conquest of Jamaica in 1655, Port Royal became a renowned pirate nest, led by Henry Morgan, whose attacks against the Spanish were defended by the colony’s governor and council. By the 1680s, pirates who plundered along the Spanish Main or in the “South Sea” coasts of Chile and Peru dropped anchor in the North American colonies. In the 1690s, men like Moses Butterworth joined crews heading out of colonial ports to the Indian Ocean, basing themselves on the island of Madagascar.

English pirate Mary Reed, who dressed as a man, reveals herself to a victim.

Private collection / DoverPictura

Beginning in 1696, support for piracy was threatened by Parliament’s efforts to reform the legal and political administration of the colonies. Initial attempts to better regulate the colonies faced heated resistance like the riot that sprang Moses Butterworth in 1701. Royal officials battled with colonial elites over control of their court system, choice of governors, economic policies, and other issues. But the transformation of law, politics, economics, and even popular culture in a relatively brief period of time soon persuaded landed colonists of the long-term benefits of legal trade over the short-term boom of the pirate market. After being sprung from jail, Moses Butterworth eventually headed to Newport, where, in 1704, he captained a sloop that sailed alongside a man-of-war in pursuit of runaway English sailors. The former pirate had turned pirate-hunter.

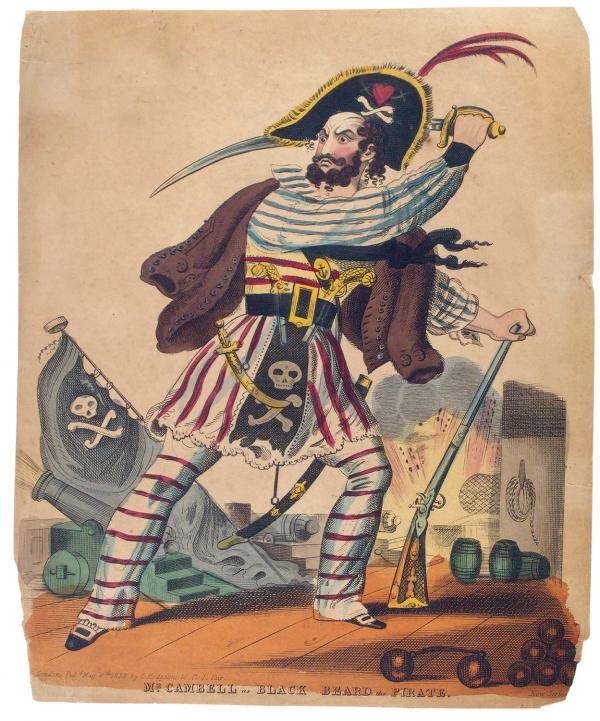

Edward Teach, better known as Blackbeard, has inspired the depiction of pirates in fiction, film, and on stage.

New York Public Library / Art Resource, NY

The expansion of commercial trade, particularly the slave trade, cemented a colonial social order increasingly threatened by instability at sea and less tolerant of social mobility on land. This change in attitudes led to the period we call the “War on Pirates”—roughly 1716 to 1726—and the advent of sea marauders who, with little hope of ever resettling on land, attacked their own nation. This is the era of characters like Blackbeard (Edward Teach), Bartholomew Roberts, and female pirates Anne Bonny and Mary Read, colorful rebels who lived dangerously and fit the legend. Where for centuries pirates had sailed under the flags of their own nations or of foreign princes, they now sailed—and were hanged under—flags of their own construction. No longer welcomed by the colonial elite, outlaw vessels were routed from shores that once harbored pirate nests. In 1718 and 1723, the ports of Newport, Rhode Island, and Charleston, South Carolina, tried and hanged crews of 23 and 26 pirates, respectively, the two largest mass executions not involving a slave insurrection in colonial America. As a result, by the late 1720s the pirate scourge had largely abated.

Mark G. Hanna is associate professor of history at the University of California–San Diego and the founding associate director of the UCSD Institute of Arts and Humanities. He received an NEH research fellowship that supported his work on Pirate Nests and the Rise of the British Empire, 1570–1740 , which won the 2016 Frederick Jackson Turner Award from the Organization of American Historians and the 2016 John Ben Snow Prize from the North American Conference on British Studies.

SUBSCRIBE FOR HUMANITIES MAGAZINE PRINT EDITION Browse all issues Sign up for HUMANITIES Magazine newsletter

The Pirate’s Life at Sea

Author: Cindy Vallar

We harbor romantic ideas about life aboard a wooden ship, but Doctor Samuel Johnson once wrote, “No man will be a sailor who has contrivance enough to get himself into a jail; for being in a ship is being in jail with the chance of being drowned…. A man in jail has more room, better food, and commonly better company.”1 His words painted a far closer image to reality, for a mariner’s life was anything but comfortable. He lived belowdecks in dim, cramped, and filthy quarters. Rats and cockroaches abounded in the bowels of the ship. Privacy was nonexistent, especially aboard a pirate ship where two hundred men might inhabit a world measuring one hundred twenty by forty feet. Within the pages of Five Naval Journals 1789-1817, an anonymous sailor said, “On the same deck with me…slept between five and six hundred men; and the ports being necessarily closed from evening to morning, the heat in this cavern of only six feet high, and so entirely filled with human bodies, was overpowering.”2

Bathroom facilities were primitive. Rotting provisions, bilgewater, and unwashed bodies made the air rank. A storm meant days of dampness after it passed. Headroom between decks posed problems for taller men. Captain Rotheram of the HMS Bellerophon, whose gun deck headroom measured five feet eight inches, surveyed his crew and found they averaged five feet five inches in height.3

According to a sailor named Barrow, “There are no men under the sun that fare harder and get their living more hard and that are so abused on all sides as we poor seamen…so I could wish no young man to betake himself to this calling unless he had good friends to put him in place or supply his wants, for he shall find a great deal more to his sorrow than I have writ.”4 For these reasons most sailors were in their mid-twenties, having gone to sea much earlier. Whether pirate or seaman, they had to have stamina and dexterity that older men no longer possessed. They also spent from three months to several years away from home.

Added to these problems were the dangers inherent in a sailor’s life. He might plummet to his death while working the sails high above the deck. He might fall overboard, in which case the ship rarely returned for him and few sailors knew how to swim. Plus there was the danger of sharks in tropical waters. Then there was the danger of fire or shipwreck. Also, the dull routine that was the norm between the sighting of sail and boarding a prize, numbed sailors’ minds. Accidents and natural disasters certainly claimed sailors’ lives, as did sea fights, but men were far more likely to succumb to disease than anything else. Scurvy, dysentery, tuberculosis, typhus, smallpox, malaria, and yellow fever killed half of all seamen. According to David Cordingly, “It has been calculated that during the wars against Revolutionary and Napoleonic France of 1793 to 1815 approximately 100,000 British seamen died. Of this number 1.5 per cent died in battle, 12 per cent died in shipwrecks or similar disasters, 20 per cent died from shipboard or dockside accidents, and no less than 65 per cent died from disease.”5

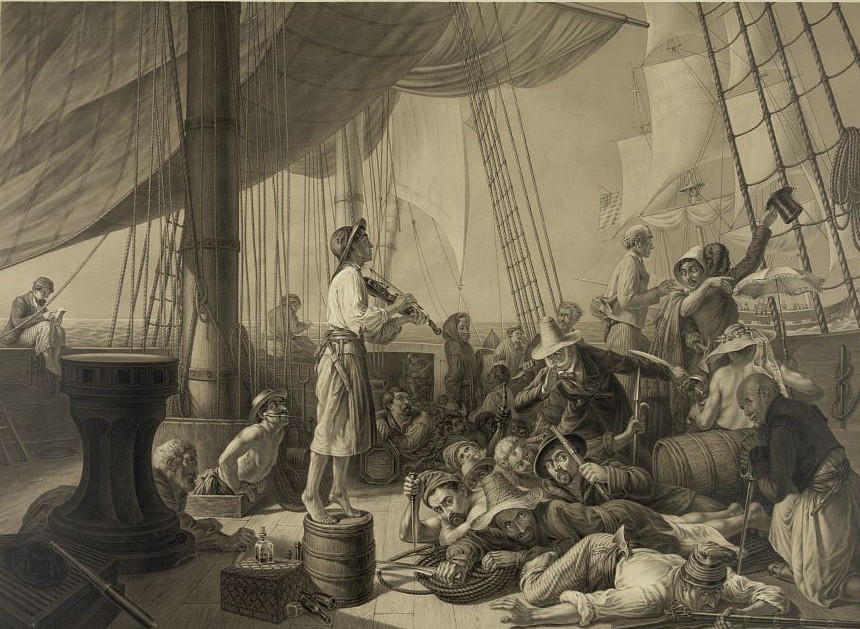

Drinking water, stored in kegs, turned foul and sailors were sometimes forced to drink this water. More often, though, they drank rum or grog rather than the brandy and wine that officers imbibed. Pirates, on the other hand, drank a mixture of rum, water, sugar, and nutmeg; rumfustian, which blended raw eggs with sugar, sherry, gin, and beer; and sherry, brandy, and port. The two most common foods sailors ate were salted meat and hard tack. The former might be kept in barrels for years before use. The latter was oftentimes invested with weevils. In the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic period, seamen ate a rather bland and routine diet. On Mondays they ate cheese and duff (flour pudding), Tuesdays and Saturdays boiled beef, Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays dried peas and duff. On Sundays they were served dried pork and Figgy Dowdy or a similar treat. Supper consisted of leftovers from dinner, a biscuit, and a pint of grog. In contrast, on 14 August 1781, a rear-admiral served twelve dinners one meal that included: boiled ducks smothered with onions, roast goose, tarts, beaten butter, potatoes, French beans, whipped cream, fruit fritters, bacon, apple pie, boiled fowl, carrots and turnips, albacore, Spanish fritters, boiled beef, and roast mutton.6

It mattered not whether the salted meat and fish turned rancid. It wasn’t thrown away. “Merchants and owners of ships are grown to such a pass nowadays…for when they send a ship out for a voyage they will put no more victuals or drink in the ship than will just serve so many days, and if they have to be a little longer in this passage and meet with cross winds, then the poor men’s bellies must be pinched for it, and be put to shorten their allowance.”7

To restock their provisions, pirates stole from the ships they seized. They also supplemented their diets with dolphins, albacore tuna, and other varieties of fish. One particular food was the green turtle. They “are extremely good to eat--the flesh very sweet and the fat green and delicious. This fat is so penetrating that when you have eaten nothing but turtle flesh for three or four weeks, your shirt becomes so greasy from sweat you can squeeze the oil out and your limbs are weighed down with it.”8 They enjoyed salamagundi, which resembled a chef’s salad. Marinated bits of fish, turtle, and meat were combined with herbs, palm hearts, spiced wine, and oil, then served with hard-boiled eggs, pickled onions, cabbage, grapes, and olives. Pirates also ate yams, plantains, pineapples, papayas, and other fruits and vegetables indigenous to the tropics.

When their provisions ran scarce, pirates did resort to extreme measures. Charlotte de Berry’s crew purportedly ate two slaves and her husband. In 1670, Sir Henry Morgan’s crew ate their leather satchels. According to written accounts, they cut the leather into strips. After soaking these, they beat and rubbed the leather with stones to tenderize them. They scraped off the hair, then roasted or grilled the strips before cutting them into bite-size pieces.

Another aspect of life at sea involved sailors’ leisure time. Whether pirate or not, they enjoyed many of the same activities, only the amount differed, particularly where drink was concerned. While gambling did occur, it wasn’t conducive to harmony amongst the men, and even the pirates included it as an intolerable infraction in their articles of agreement. Chewing tobacco, scrimshaw, and embroidery were popular pastimes. They also spun yarns about fearsome ghosts and goblins. When pirates boarded a prize, musicians were among the most sought after sailors enlisted into the ranks of the pirates, whether they joined willingly or were forced, because pirates loved entertainment.

Why did sailors take the extra risk of going on the account? Piracy offered a number of advantages, not the least of which was freedom from the harsh discipline suffered in the Royal Navy or aboard a merchantman. Pirates rarely flogged their mates, and while marooning and death were severe forms of punishment, they never endured six hundred lashes, swallowing cockroaches or iron bolts to learn a lesson. Nor would a pirate captain dare to cut out an eye as happened to Richard Desbrough.9 Life on land was equally fraught with cruel punishments, for use of the thumbscrew, pillory, and branding iron were still in use. “Children as young as seven, both boys and girls, were hanged. …[I]n 1698, Parliament had passed a law that the theft of good, worth more than five shillings, rated the death penalty.”10

When a sea captain refused to join his crew, one pirate said, “Damn ye, you are a sneaking puppy and so are all those who will submit to be governed by laws which rich men have made for their own security, for the cowardly whelps have not the courage otherwise to defend what they got by their knavery. But damn ye altogether. Damn them for a pack of craft rascals, and you, who serve them, for a parcel of hen-hearted numbskulls. They vilify us, the scoundrels do, then there is only this difference, they rob the poor under the cover of law, forsooth, and we plunder the rich under the protection of our own courage; had ye not better make one of use, than sneak after the arses of those villains for employment?”11

Aside from freedom, the financial rewards were far greater as a pirate than as a legitimate sailor, especially since pirates shared their plunder more equitably than privateers or the navy did. Gold, silver, silks, spices, timber, and a variety of other commodities made lucrative prizes. A privateer in the early seventeenth century might receive £10, the wages of most sailors for one year. A pirate, on the other hand, had the potential of earning up to £4,000 in a year, although he rarely held onto his ill-gotten gains for long. In 1695, Captain Avery and his men captured the Gunsway, and netted about £1,000 each. In 1721, pirates under John Taylor and Oliver la Buze netted £875,000 after seizing a Portuguese East Indiaman.

Even so, not all sailors turned pirate when their ships were taken. Captain William Snelgrave spent time as a captive of Howell Davis. He published an account of his experiences in 1734. His descriptions of pirate life weren’t complimentary. “[T]he execrable Oaths and Blasphemies I heard among the Ship’s Company, shocked me to such a degree, that in Hell its self I thought there could not be worse; for though many Seafaring Men are given to swearing and taking God’s name in vain, yet I could not have imagined, human Nature could ever so far degenerate, as to talk in the manner those abandoned Wretches did.”12 “They hoisted upon Deck a great many half-Hogsheads of Claret, and French Brandy; knocked their Heads out, and dipped cans and bowls into them to drink out of: And in their Wantonness threw full Buckets of each sort upon one another. As soon as they had emptied what was on the Deck, they hoisted up more: and in the evening washed the Decks with what remained in the Casks. As to bottled Liquor of many sorts, they made such havoc of it, that in a few days they had not one Bottle left: For they would not give themselves the trouble of drawing the Cork out, but nicked the Bottles, as they called it, that is, struck their necks off with a Cutlace; by which means one in three was generally broke: Neither was there any Cask-liquor left in a short time, but a little brandy. As to Eatables, such as Cheeses, Butter, Sugar, and many other things, they were as soon gone. For the Pirates being all in a drunken Fit, which held as long as the Liquor lasted, no care was taken by any one to prevent this Destruction….”13

Pirates, however, saw life from a different perspective. While some regretted going on the account, most laughed in the face of death. All sailors knew they might die before a voyage ended, and pirates weighed past experiences against the promise of wealth beyond their wildest dreams. Even though few attained such wealth, they still opted for freedom and potential riches. Perhaps Bartholomew Roberts best summed up their philosophy. “In honest service there is thin rations, low wages and hard labour; in this [service], plenty and satiety, pleasure and ease, liberty and power; and who would not balance creditor on this side, when all the hazard that is run for it, at worse, is only a sour look or two at choking. No, a merry life and a short one shall be my motto.”14

Endnotes: 1 Rediker, Marcus. Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea (1987), page 258. 2 Patrick O’Brian’s Navy (2003), page 87. 3 Cordingly, David. The Billy Ruffian (2003), page 209. 4 Gill, Anton. The Devil’s Mariner (1997), page 75. 5 Cordingly, page 165. 6 Blake, Nicholas, and Richard Lawrence. The Illustrated Companion to Nelson’s Navy (2000), page 99. 7 Gill, page 77. 8 Exquemelin, Alexander O.. Buccaneers of America (1969), page 73. 9 Ibid, page 79. 10 Zacks, Richard. The Pirate Hunter (2002), page 357. 11 Gill, pages 79-80. 12 Breverton, Terry. Black Bart Roberts (2004), page 29. 13 Ibid., page 35. 14 Gill, page 80.

By Tim Hayburn

Philadelphia, like many cities throughout the Atlantic world, encountered a new threat in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries from pirates who raided the numerous merchant vessels in the region. Several historians have labeled this era as the golden age of piracy. Pirates also remained active after 1730, using the city as a staging ground, especially during conflicts such as the Revolutionary War. While Pennsylvania authorities sought to end piracy throughout the colonial and early national periods, their policy appears ambivalent as they sometimes extended leniency toward pirates rather than confront them with the full force of the law.

Pirates were outlaws on the sea who attacked all ships, regardless of their nation of origin. They plagued shipping routes, which had at times a devastating effect on trade in Philadelphia. Many pirates first served as privateers, who were employed by nations such as England as alternatives or in addition to a formal navy during times of war. Privateers received a letter of marque, or commission, to raid enemy ships. When the conflicts came to an end, however, many of the privateers became pirates, continuing to rob ships of their cargoes, which the pirates shared.

Soon after Philadelphia’s founding, the city’s growing population and economic importance attracted pirates who threatened the region’s thriving trade. Piracy offered local sailors the opportunity to earn higher profits and benefits that they would not receive on merchant or naval vessels. Life on board pirate ships tended to be much more democratic than on other ships as pirates could even depose an unpopular captain and discipline was much more lax.

Pirates regularly operated around the Delaware River by the late seventeenth century, which fueled fears about the safety of the local waterways. In 1699, the colony arrested four men believed to serve under the notorious pirate Captain William Kidd (c. 1645-1701) . The Pennsylvania Assembly enacted several statutes to prevent pirates from moving freely in society and to keep others from collaborating with them. Some merchants in the Delaware Valley willingly tolerated piracy, however, because of its economic benefits. Pirates spent their booty freely in port cities such as Philadelphia and contributed to the region’s economic development. William Markham (1635-1704), Pennsylvania’s deputy governor, even allegedly received a bribe from the pirate John Avery (1659-c. 1696), who raided ships throughout the Indian Ocean and was subject to an English manhunt. Markham’s relationship with Avery extended beyond simply accepting a bribe as he also allowed one of his daughters to marry the infamous pirate captain.

Piracy continued to be a major concern for many merchants in the early 1700s, despite the unofficial toleration of some officials and the potential benefits of piracy for some segments of the Delaware Valley economy. Lieutenant Governor William Keith (1669-1749) issued a warrant for the arrest of Edward Teach (c. 1680-1718), better known as Blackbeard, for his attacks on merchant ships. Keith feared that Blackbeard maintained contact with former pirates, who now lived in Philadelphia and aided him in his raids against Philadelphia’s merchants. The local newspaper provided periodic reports of pirate activity in the Philadelphia region by the early 1720s. Pirates even managed to prevent ships from leaving Philadelphia for an entire week in 1722. The Pennsylvania Assembly sought to eliminate property crimes such as robbery by making them subject to capital punishment, which could be used in cases against pirates.

A Trial for Piracy

Perhaps because local authorities realized the financial contribution of pirates to the region, Philadelphia witnessed only one trial for piracy in the first half of the eighteenth century. In 1730, English sailors serving on board a Portuguese ship mutinied and became pirates before finally being arrested and condemned to death in Philadelphia. During an era when pirates could hope for little mercy, four of these condemned pirates surprisingly received a pardon from Pennsylvania authorities after their ringleader escaped. Indeed, many Philadelphians may have supported pirates, as testimony in a 1718 case alleged that Pennsylvania merchants provided pirates with ammunition and supplies.

After 1730, piracy ceased to be a major problem for Philadelphia although privateers occasionally disrupted the city’s shipping. Both colonial officials and the British government sought to reduce the threat of piracy. The Revolutionary War, however, allowed for a resurgence of pirates by the 1780s. When the Continental Congress employed privateers to supplement its meager naval forces, several crews turned to piracy. Local newspapers complained about these “villains” who disrupted the Revolutionary War effort, but Pennsylvania’s courts condemned only four men for piracy in the 1780s. One condemned pirate was even sentenced to have his body gibbeted to deter other potential pirates. Nevertheless, Pennsylvania’s government again surprisingly opted for leniency in his case as well as most of the other condemned pirates and executed only one convicted pirate during this time.

By the 1790s, the Pennsylvania legislature removed piracy from the list of capital crimes. Cases of piracy declined into the nineteenth century. The state did witness several cases of piracy in the early nineteenth century, but applied the death penalty only in cases in which the pirates committed murder as well. Indeed, in 1837, convicted pirate James Moran was the last individual publicly executed in Pennsylvania for any crime. Although Philadelphia merchants could occasionally fall victim to pirates in other corners of the globe such as the Mediterranean Sea, piracy ceased to be a major concern in the Delaware Valley, thus ending Pennsylvania’s ambivalent policy towards piracy as well.

Tim Hayburn received his doctorate in Colonial American History from Lehigh University.

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Captain Kidd in New York Harbor

Library of Congress

This romanticized view of pirate life is what drove many young sailors to become pirates. Many pirates were former sailors in the Royal Navy during the War of the Spanish Succession (or Queen Anne’s War, 1701-1713). At the close of the war Britain no longer needed the many sailors it had impressed into service, and after the war fired many sailors. Lack of work drove men who had no other skills to become sailors on merchant vessels, or pirates. For many, piracy was their last hope to make a living, and some dreamed to strike it rich, like Captain Kidd in this painting.

In 1699, the Pennsylvania colony arrested four men believed to serve under Kidd.

Edward Teach, better known as Blackbeard, was an infamous pirate who operated across the Atlantic coast of North America and the Caribbean between 1716 and 1718. There was speculation he was a privateer for the British Royal Navy during the War of the Spanish Succession (also known as Queen Anne’s War), but he was eventually hunted down and killed by a British naval force under the command of Lieutenant Robert Maynard.

Earlier, Pennsylvania Lieutenant Governor William Keith issued a warrant for the arrest of Blackbeard for his attacks on merchant ships. Keith feared that Blackbeard maintained contact with former pirates who lived in Philadelphia and aided him in his raids against Philadelphia’s merchants.

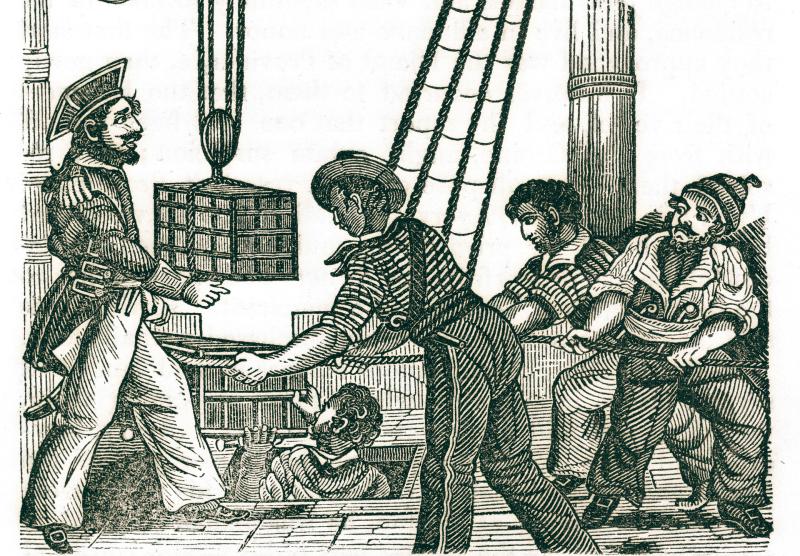

The Pirate's Ruse

This work is a nineteenth-century interpretation of pirates attempting to lure in a ship so they can board it. While pirate ships in many cases were armed with naval cannons, it was bad for business to use them. A damaged or sunk ship made it harder or impossible to steal the valuable items on the ship, or the ship itself. Instead, pirates lured a merchant ship, or naval vessel, close to their own, using tactics such as flying the flag (or colors) of a friendly nation and appearing harmless. When the prize they were seeking to plunder came close, they raised their pirate colors and boarded the enemy vessel, fighting the crew in close quarters.

Pirate Troubadors

Good-humored pirates sing sea shanties during the annual pirate day at Fort Mifflin. The Delaware River fort's early history included defending Philadelphia from pirates. The singers are members of the Sea Dogs, a New Jersey-based band and pirate/privateer reenactment group. (Photograph by Donald D. Groff for the Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia)

Related Topics

- Philadelphia and the World

Time Periods

- Capital of the United States Era

- American Revolution Era

- Colonial Era

- Center City Philadelphia

- Privateering

Related Reading

Hayburn, Timothy. “Who Should Die?: The Evolution of Capital Punishment in Pennsylvania, 1681-1794.” Ph.D. diss., Lehigh University, 2011.

Linebaugh, Peter and Marcus Rediker. The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic . Boston: Beacon Press, 2000.

Mervine, William M. “Pirates and Privateers in the Delaware Bay and River.” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 32, no. 4 (1908): 459-470.

Rediker, Marcus. Villains of All Nations: Atlantic Pirates in the Golden Age . Boston: Beacon Press, 2004.

Sellin, Thorsten, “The Philadelphia Gibbet Iron.” Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science 46, no. 1 (1955): 11-25.

Related Collections

Courts of Oyer and Terminer and General Goal Delivery, Court Papers, 1757-1761, 1763, 1765-1766, 1778-1782, 1786-1787, Records of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, RG-33, Pennsylvania State Archives , 350 North Street, Harrisburg, Pa.

Courts of Oyer and Terminer and General Goal Delivery, General Gaol Delivery Dockets, 1778-1828, Records of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, RG-33, Pennsylvania State Archives , 350 North Street, Harrisburg, Pa.

Related Places

Philadelphia History Museum , 15 S. Seventh Street, Philadelphia. (This museum possesses the gibbet that was supposed to have been used in 1780.)

Independence Seaport Museum , Penn’s Landing, Philadelphia.

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- 45-foot ship to tell story of the American Revolution (WHYY, July 31, 2016)

- Top Earning Pirates of All Times (Forbes, September 18, 2008)

- On Front Street, Digging Through Time (Hidden City Philadelphia, October 17, 2012)

Connecting the Past with the Present, Building Community, Creating a Legacy

The Golden Age of Piracy

Though pirates have existed since ancient times, the Golden Age of piracy was in the 17th and early 18th centuries. During this time more than 5000 pirates were said to be at sea.

Throughout history there have been people willing to rob others transporting goods on the water. These people, known as pirates, mainly targeted ships, though some also launched attacks on coastal towns.

Many of the most famous pirates had a terrifying reputation, and they advertised this by flying gruesome flags, including the 'Jolly Roger' with its picture of skull and crossbones. Captives were famously made to ‘walk the plank’ – though this doesn’t appear to have been as common in reality as in fiction; in fact, it's likely that most victims of piracy were just thrown overboard.

Pirates have existed since ancient times – they threatened the trading routes of ancient Greece, and seized cargoes of grain and olive oil from Roman ships. The most far-reaching pirates in early medieval Europe were the Vikings.

Thousands of pirates were active between 1650 and 1720, and these years are sometimes known as the 'Golden Age’ of piracy. Famous pirates from this period include Henry Morgan, William 'Captain' Kidd, 'Calico' Jack Rackham, Bartholomew Roberts and the fearsome Blackbeard (Edward Teach). Though this Golden Age came to an end in the 18th century, piracy still exists today in some parts of the world, especially the South China Seas.

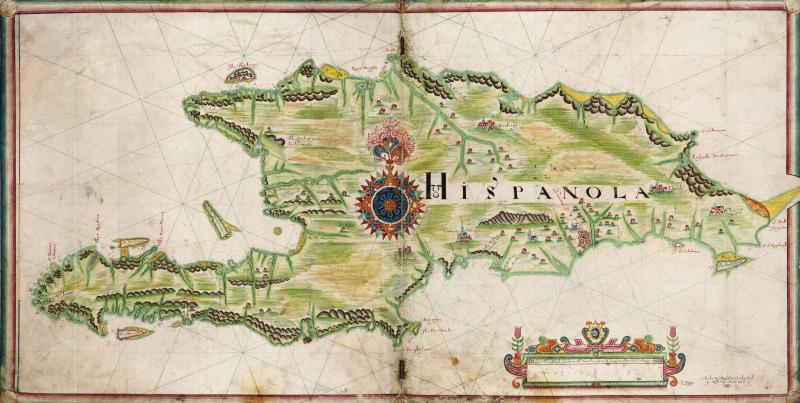

Pirates of the Caribbean

The explorer Christopher Columbus established contact between Europe and the lands that were later named America at the end of the 15th century. As he was working for the Spanish monarchy, these 'new lands' were claimed by the Spanish, who soon discovered them to be a rich source of silver, gold and gems.

From the 16th century, large Spanish ships, called galleons, began to sail back to Europe, loaded with precious cargoes that pirates found impossible to resist. So many pirate attacks were made that galleons were forced to sail together in fleets with armed vessels for protection. As Spanish settlers set up new towns on Caribbean islands and the American mainland, these too came under pirate attack.

Corsairs, buccaneers and privateers

Corsairs were pirates who operated in the Mediterranean Sea between the 15th and 18th centuries. Muslim corsairs, such as the Barbarossa (red beard) brothers, had bases along North Africa’s Barbary Coast, while Christian corsairs were based on the island of Malta. Both used to swoop down on their targets in oar-powered boats called galleys, to carry off sailors and passengers. Unless these unfortunates were rich enough to pay a ransom, they were sold as slaves.

Buccaneers lived on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola and its tiny turtle-shaped neighbour, Tortuga, in the 17th century. At first they lived as hunters, but later the governors of Caribbean islands paid the buccaneers to attack Spanish treasure ships. Although raids began in this way, with official backing, the buccaneers gradually became out of control, attacking any ship they thought carried valuable cargo, whether it belonged to an enemy country or not. The buccaneers had become true pirates.

Privateers, meanwhile, were privately owned (rather than navy) ships armed with guns, operating in times of war. The Admiralty issued them with 'letters of marque' that allowed them to capture merchant vessels without being charged with piracy.

Why did pirates become pirates?

In England there was social disruption. Smaller farmers were forced off the land by ruthless landowners and smaller tradesmen were challenged by larger businesses. These displaced people flocked to urban areas looking for work or poor relief.

In London especially there was overcrowding and unemployment and funds for the poor could not meet the need. People had to shift for themselves. Distressed people weren't simply worse off, they had no hope of making a better life. Piracy tempted poor seamen because it offered them the chance to take more control of their lives.

In an age when few people travelled and young men might have to work seven-year apprenticeships before they could make an independent living, many were tempted to go to sea anyway, though the life was a tough one.

Adolescents who longed to escape could get a job on a sailing ship before they were fully grown: agility was needed as much as brute strength.

Yet ordinary seamen toiled for modest wages and were subject to strict discipline. In contrast, piracy not only offered them a chance to get rich quick but also a rare opportunity to exert a degree of power over others

More about pirates

The life and times of a pirate

Letters of marque

The real pirates of the Caribbean

Infamous pirates

Jack Sparrow, Long John Silver and Captain Hook

Bringing pirates to justice

Shop our selection of pirate-themed books

The image of the pirate never fails to capture the imagination. Browse our range of publications to inform and entertain

Grim Life Cursed Real Pirates of Caribbean

What was life really like for an early 18th-century pirate? A world of staggering violence and poverty, constant danger, and almost inevitable death.

Pirates have been figures of fascination and fear for centuries. The most famous buccaneers have been shrouded in legend and folklore for so long that it's almost impossible to distinguish between myth and reality.

Hollywood movies—filled with buried treasures, eye patches, and the Jolly Roger—depict pirate life as a swashbuckling adventure.

In the latest flick, Disney's Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl, which sails into theaters today, the pirate hero, played by Johnny Depp, is a lovable rogue.

But what was life really like for an early 18th-century pirate? The answer: pretty grim. It was a world of staggering violence and poverty, constant danger, and almost inevitable death.

The life of a pirate was never as glorious and exciting as depicted in the movies, said David Moore, curator of nautical archaeology at the North Carolina Maritime Museum in Beaufort. "Life at sea was hard and dangerous, and interspersed with life-threatening storms or battles. There was no air conditioning, ice for cocktails, or clean sheets aboard the typical pirate ship."

While the period from the late 1600s to the early 1700s is usually referred to as the "Golden Age of Piracy," the practice existed long before Blackbeard and other famous pirates struck terror in the hearts of merchant seamen along the Eastern Seaboard and Caribbean. And it exists today, primarily in the South China Sea and along the African coast.

For Hungry Minds

Valuable loot.

One of the earliest and most high profile incidents of piracy occurred when a band of pirates captured Julius Caesar, the Roman emperor-to-be, in the Greek islands. Instead of throwing him overboard, as they did with most victims, the pirates held Caesar for ransom for 38 days.

When the money finally arrived, Caesar was let go. When he returned to port, Caesar immediately fitted a squadron of ships and set sail in pursuit of the pirates. The criminals were quickly caught and brought back to the mainland, where they were hanged.

It's no coincidence that piracy came to flourish in the Caribbean and along America's Eastern Seaboard during piracy's heyday. Traffic was busy and merchant ships were easy pickings.

Although pirates would search the ship's cabins for gold and silver, the main loot consisted of cargo such as grain, molasses, and kegs of rum. Sometimes pirates stole the ships as well as the cargo.

Neither Long John Silver nor Captain Hook actually existed, but the era produced many other infamous pirates, including William Kidd, Charles Vane, Sam Bellamy, and two female pirates, Anne Bonny and Mary Read.

The worst and perhaps cruelest pirate of them all was Captain Edward Teach or Thatch, better known as "Blackbeard." Born in Britain before 1690, he first served on a British privateer based in Jamaica. Privateers were privately owned, armed ships hired by the British government to attack and plunder French and Spanish ships during the war.

After the war, Blackbeard simply continued the job. He soon became captain of one of the ships he had stolen, Queen Anne's Revenge, and set up base in North Carolina, then a British colony, from where he preyed on ships traveling the American coast.

Tales of his cruelty are legendary. Women who didn't relinquish their diamond rings simply had their fingers hacked off. Blackbeard even shot one of his lieutenants so that "he wouldn't forget who he was."

Still, the local townspeople tolerated Blackbeard because they liked to buy the goods he stole, which were cheaper than imported English goods. The colony's ruling officials turned a blind eye to Blackbeard's violent business.

You May Also Like

These pirates left the Caribbean behind—and stole the biggest booty ever

These treasure-hunting pirates already came from riches

Irish Claddagh rings have an unexpected history—it involves pirates.

It wasn't until Alexander Spotswood, governor of neighboring Virginia, sent one of his navy commanders to kill Blackbeard that his reign finally came to an end in 1718.

True or False

The most famous pirates may not have been the most successful. "The reason many of them became famous was because they were captured and tried before an Admiralty court," said Moore. "Many of these court proceedings were published, and these pirates' exploits became legendary. But it's the ones who did not get caught who were the most successful in my book."

Treasure Island, by Robert Louis Stevenson, may be the most famous pirate story. But the most important real-life account of pirate life is probably a 1724 book called A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates, by Captain Charles Johnson.

The tome depicts in gruesome detail the lives and exploits of the most famous pirates of that time. Much of it reads as a first-hand account by someone who sailed with the pirates, and many experts believe Johnson was actually Daniel Defoe, the author of Robinson Crusoe, which was published in 1719.

What is not in doubt is the book's commercial success at the time and the influence it had on generations of writers and filmmakers who adopted elements of his stories in creating the familiar pirate image.

So what part of the movie pirate is true and what is merely Hollywood fiction? What about, for example, the common practice of forcing victims to "walk the plank"?

"Not true," said Cori Convertito, assistant curator of education at the Mel Fisher Maritime Museum in Key West, Florida, which is putting on a piracy exhibit this October called "Reefs, Wrecks and Rascals." (The pirates' favorite form of punishment was to tie their victims to the boat with a length of rope, toss them overboard, and drag them under the ship, a practice known as "keel hauling.")

Sadly, buried treasures—and the ubiquitous treasure maps—are also largely a myth. "Pirates took their loot to notorious pirate hang-outs in Port Royal and Tortuga," said Convertito. "Pirates didn't bury their money. They blew it as soon they could on women and booze."

Eye Patches, Peg Legs, and Parrots

On the other hand, pirate flags, commonly referred to as the Jolly Roger, were indeed present during the Golden Age. And victims were often marooned on small islands by pirates. Eye patches and peg legs were also undoubtedly worn by pirates, and some kept parrots as pets.

Some pirates even wore earrings, not as a fashion statement, but because they believed they prevented sea sickness by applying pressure on the earlobes.

In the new movie Pirates of the Caribbean, prisoners facing execution can invoke a special code, which stipulates that the pirate cannot kill him or her without first consulting the pirate captain.

Indeed pirates did follow codes. These varied from ship to ship, often laying out how plundered loot should be divided or what punishment should be meted out for bad behavior.

But Jack Sparrow, Johnny Depp's hero, probably wouldn't have lasted very long among real pirates. In the movie, he will do anything possible to avoid a fight, something real-life pirates rarely did.

The endless sword duels, a big part of all pirate movies, probably happened on occasion. But real-life encounters were often far more bloody and brutal, with men hacking at each other with axes and cutlasses.

In one legendary account, a notorious pirate, trying to find out where a village had hidden its gold, tied two villagers to trees, facing each other, and then cut out one person's heart and fed it to the other.

As Captain Johnson wrote in his book:

In the commonwealth of pirates, he who goes the greatest length or wickedness is looked upon with a kind of envy amongst them, as a person of a more extraordinary gallantry, and is thereby entitled to be distinguished by some post, and if such a one has but courage, he must certainly be a great man.

Related Topics

Where did pirates spend their booty?

Forget 'walking the plank.' Pirate portrayals—from Blackbeard to Captain Kidd—are more fantasy than fact.

Ahoy! It's the real pirates of the Caribbean—and the Carolinas

Queen Elizabeth I's favorite pirate was an English hero, but his career has a dark side

Pirates once swashbuckled across the ancient Mediterranean

- Environment

- Paid Content

- Photography

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Utility Menu

Samuel Diener

Expository writing 20. “a pirate’s life for me”: legends of buccaneers at sea (harvard writing program), semester: , offered: .

In this course, we will read (and watch!) some of the best-known stories about pirates in the age of sail. We’ll explore both the myths and realities of these infamous outlaws, and ask why their crimes were treated so uniquely: sometimes the stateless “villains of all nations,” society’s most wanted criminals; sometimes celebrated for their daring, or even seen as patriotic heroes. We’ll also consider what work stories about pirates do in our culture. The “wooden world” of the ship’s decks offers a space for thinking about how communities are made. It is a space where state violence is enacted and ideas of criminality are formed. It is also a space where norms and perceptions about gender, sexuality, race, and class can be re-imagined in new ways. But does this translate into subversive potential? Or are tales of life at sea just places where society can make castaways of its own inner demons? And, perhaps most strangely of all, how do the murderous escapades of society’s villains become the stuff of Disney rides and cartoons for children? In other words: why are pirates "fun"?

We’ll begin the class with some stories of real-life pyrates, both men and women, from the Golden Age of Caribbean piracy that were collected by the pilloried, exiled, and nine-times-imprisoned opposition journalist Nathaniel Mist in his bestselling General History of the Pyrates. We’ll examine the rhetoric of these tales and think about the way they are told and the political and social “work” they do. Then, in the second unit of the class, we’ll read the most famous fictional tale of piracy, Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, and think about the role it (and stories like it) played in reshaping the pirate’s modern myth as one of boyhood and masculinity. In the class’s final weeks, we’ll look at some film and popular culture and consider the ongoing life of the legends of piracy today.

c/o Department of English

12 Quincy St., Cambridge, MA 02138

(he/him/his)

10 Facts About Pirates

Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

- Caribbean History

- History Before Columbus

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Central American History

- South American History

- Mexican History

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- Ph.D., Spanish, Ohio State University

- M.A., Spanish, University of Montana

- B.A., Spanish, Penn State University

The so-called “Golden Age of Piracy” lasted from about 1700 to 1725. During this time, thousands of people turned to piracy as a way to make a living. It is known as the “Golden Age” because conditions were perfect for pirates to flourish, and many of the individuals we associate with piracy, such as Blackbeard , “Calico Jack” Rackham , and “Black Bart” Roberts , were active during this time. Here are 10 things you maybe did not know about these ruthless sea bandits.

Pirates Rarely Buried Treasure

Some pirates buried treasure—most notably Captain William Kidd , who was at the time heading to New York to turn himself in and try to clear his name—but most never did. There were reasons for this. First of all, most of the loot gathered after a raid or attack was quickly divided up among the crew, who would rather spend it than bury it. Secondly, much of the “treasure” consisted of perishable goods like fabric, cocoa, food, or other things that would quickly become ruined if buried. The persistence of this legend is partly due to the popularity of the classic novel “Treasure Island,” which includes a hunt for buried pirate treasure .

Their Careers Didn't Last Long

Most pirates didn’t last very long. It was a tough line of work: many were killed or injured in battle or in fights amongst themselves, and medical facilities were usually non-existent. Even the most famous pirates , such as Blackbeard or Bartholomew Roberts, only were active in piracy for a couple of years. Roberts, who had a successful career as a pirate , was only active from 1719 to 1722.

They Had Rules and Regulations

If all you ever did was watch pirate movies, you’d think that being a pirate was easy: no rules other than to attack rich Spanish galleons, drink rum and swing around in the rigging. In reality, most pirate crews had a code that all members were required to acknowledge or sign. These rules included punishments for lying, stealing, or fighting on board. Pirates took these articles very seriously and punishments could be severe.

They Didn't Walk the Plank

Sorry, but this one is another myth. There are a couple of tales of pirates walking the plank well after the “Golden Age” ended, but little evidence to suggest that this was a common punishment before then. Not that pirates didn’t have effective punishments, mind you. Pirates who committed an infraction could be marooned on an island, whipped, or even “keel-hauled,” a vicious punishment in which a pirate was tied to a rope and then thrown overboard: he was then dragged down one side of the ship, under the vessel, over the keel and then back up the other side. Ship bottoms were usually covered with barnacles, which often resulted in very serious injuries in these situations.

A Good Pirate Ship Had Good Officers

A pirate ship was more than a boatload of thieves, killers, and rascals. A good ship was a well-run machine, with officers and a clear division of labor. The captain decided where to go and when, and which enemy ships to attack. He also had absolute command during battle. The quartermaster oversaw the ship’s operations and divided up the loot. There were other positions, including boatswain, carpenter, cooper, gunner, and navigator. Success on a pirate ship depended on these men carrying out their tasks efficiently and supervising those under their command.

The Pirates Didn't Limit Themselves to the Caribbean

The Caribbean was a great place for pirates: there was little or no law, there were plenty of uninhabited islands for hideouts, and many merchant vessels passed through. But the pirates of the “Golden Age” did not only work there. Many crossed the ocean to stage raids off the west coast of Africa, including the legendary “Black Bart” Roberts. Others sailed as far as the Indian Ocean to work the shipping lanes of southern Asia: it was in the Indian Ocean that Henry “Long Ben” Avery made one of the biggest scores ever: the rich treasure ship Ganj-i-Sawai.

There Were Women Pirates

It was extremely rare, but women did occasionally strap on a cutlass and pistol and take to the seas. The most famous examples were Anne Bonny and Mary Read , who sailed with “Calico Jack” Rackham in 1719. Bonny and Read dressed as men and reportedly fought just as well (or better than) their male counterparts. When Rackham and his crew were captured, Bonny and Read announced that they were both pregnant and thus avoided being hanged along with the others.

Piracy Was Better Than the Alternatives

Were pirates desperate men who could not find honest work? Not always: many pirates chose the life, and whenever a pirate stopped a merchant ship, it was not uncommon for a handful of merchant crewmen to join the pirates. This was because “honest” work at sea consisted of either merchant or military service, both of which featured abominable conditions. Sailors were underpaid, routinely cheated of their wages, beaten at the slightest provocation, and often forced to serve. It should surprise no one that many would willingly choose the more humane and democratic life on board a pirate vessel.

They Came From All Social Classes

Not all of the Golden Age pirates were uneducated thugs who took up piracy because they lacked a better way to make a living. Some of them came from higher social classes as well. William Kidd was a decorated sailor and very wealthy man when he set out in 1696 on a pirate-hunting mission: he turned pirate shortly thereafter. Another example is Major Stede Bonnet , who was a wealthy plantation owner in Barbados before he outfitted a ship and became a pirate in 1717: some say he did it to get away from a nagging wife.

Not All Pirates Were Criminals

During wartime, nations would often issue Letters of Marque and Reprisal, which allowed ships to attack enemy ports and vessels. Usually, these ships kept the plunder or shared some of it with the government that had issued the letter. These men were called “privateers,” and the most famous examples were Sir Francis Drake and Captain Henry Morgan . These Englishmen never attacked English ships, ports, or merchants and were considered great heroes by the common folk of England. The Spanish, however, considered them pirates.

- The Pirate Hunters

- The Golden Age of Piracy

- Famous Pirate Flags

- Real-Life Pirates of the Caribbean

- Understanding Pirate Treasure

- Biography of John 'Calico Jack' Rackham, Famed Pirate

- Pirates: Truth, Facts, Legends and Myths

- Famous Pirate Ships

- Biography of Mary Read, English Pirate

- Facts About Anne Bonny and Mary Read, Fearsome Female Pirates

- The History and Culture of Pirate Ships

- 5 Successful Pirates of the "Golden Age of Pirates"

- The 10 Best Pirate Attacks in History

- Pirate Crew: Positions and Duties

- Biography of Anne Bonny, Irish Pirate and Privateer

- Biography of Stede Bonnet, the Gentleman Pirate

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

“Well-Behaved Pirates Seldom Make History: A Reevaluation of English Piracy in the Golden Age” In Governing the Sea in the Early Modern Era, Edited by Peter C. Mancall and Carole Shammas

Related Papers

Nathan Petch

The word “pirate” stems from the Classical Greek word “peirates”, which means an attempt or attack. Some scholars have defined it as “violent maritime predation” or “the indiscriminate taking of property with violence”, whereas others have focussed on the economy to understand it as “tribute taking”, “commerce raiding”, or as “a business”. There is substantial debate between maritime historians regarding the main representations of and motives for piracy. Rediker’s Marxist and bottom-up interpretation has inevitably caused controversy, following on from that surrounding historian Eric Hobsbawm with his suggestion of “social banditry” some decades earlier. Several historians, such as Dawdy & Bonni and Curtis, have supported Rediker’s view on piracy as social banditry. According to them, it was an ideologically-driven undertaking that directly challenged the ways of the society from which they had excepted themselves. Many others on the other hand have either criticised or contradicted Rediker’s assertion. Starkey has argued in favour of economic factors as being the main motive for pirates, and that there were “cycles” with this phenomenon. This essay considers the “Golden Age” of piracy – lasting roughly from the start of the eighteenth century until 1730 – and its Atlantic theatre. Overall, it seems that piracy was not social banditry – as suggested by Rediker, but rather a response to economic factors.

Martin Mares

This work analyses the public perception of the role of privateers and their transition to pirates and examines both negative and positive outcomes in various areas like diplomacy, international trade, legal, racial and gender issues. The entire topic is examined through various cases of pirates including Bartholomew Roberts, Sir Henry Morgan, Thomas Tew, William Kid, Jack Rackham, Stede Bonnet, Edward Teach, Samuel Bellamy, Mary Read, Anne Bony or Henry Avery as well as historical records including letters, trials and pamphlets. Further, this essay discusses an interesting development of piracy from state-funded expeditions into utterly illegal activity driven by various reasons. Particularly the transition between legal, semi-legal and illicit separates England and Great Britain (from 1707 onwards) from other colonial powers such as France, Spain or Dutch. Despite the fact that they all issued privateering licenses and therefore they had to face similar problems connected to privateering, the outburst of piracy in the case of England was so dangerous that England (Great Britain) during the late 17th and early 18th century was called a “nation of pirates”. Hence, this work analyses both legal and practical actions against pirates in British colonies and their effectiveness after 1715. The last part of this essay is dedicated to piracy regarding an alternative way of life for disadvantaged social groups in the 17th and 18th century and contemporary negative or positive portrayal of piracy. The role of liberated “Negroe” and “Mullato” slaves is also examined throu

Pirates, Slaves, and Profligate Rogues: Sailing Under the Jolly Roger in the Black Atlantic

Victoria Barnett-Woods

The age of piracy in the Atlantic world spanned nearly a century, beginning in 1650 and ending in the late 1720s. The rise of Atlantic piracy coincides with the rise of the increasing maritime trade, particularly with the establishment of the transatlantic slave trade between the African continent and the American colonies. There are multiple accounts of pirate ships that have attacked slavers along the littoral states of either side of the Atlantic. In these moments of piratical enterprise, the “thieves and robbers” of enslaved Africans themselves become themselves the victims of robbery and violence. Also, in these moments, the very embodiment of liberation (the pirate) encounters the distillation of oppression and disenfranchisement (the enslaved). This chapter will discuss the significance of these encounters through the lenses of both transatlantic commerce and the human condition. At the intersection of piracy and the slave trade, there are dozens of stories to be told, and with their telling in this chapter, a new vision of the maritime world demonstrates what it may cost to truly be free. In a series of case studies, this chapter will examine an arc of Atlantic piracy during its golden age. I will establish piratical views toward the enslaved with a close reading of Dampier’s New Voyage Round the World specifically focusing on his time on the Bachelor’s Delight (1697), to then discuss the accounts of four pirate captains at the height of piracy’s “golden age.” These men—Hoar, Kidd, Roberts, and Teach—all gained significant notoriety during their exploits, but also represent the ways in which pirate captains viewed men of African descent within their framework of being “gentlemen of fortune.” For Bartholomew Roberts, for example, one-third of his crew was composed of formerly enslaved men. Both Hoar and Kidd, with unique visions of the capacity of the formerly enslaved, had black men as their Quartermaster-- one of the most critical administrative positions of any vessel. The stories of these men and pirates will be at the heart of this discussion, hopefully illuminating the raw and powerful intersection of trade, slavery, and freedom on the high seas in the early eighteenth century.

Claire Jowitt

This contribution focuses on a particular group of maritime agents in Shakespeare’s plays, namely pirates, and the cultural-political questions they raise.

Voces Novae

Bijan Kazerooni

In September 1717, King George I issued a royal proclamation calling for the suppression of piracy and offered amnesty for those individuals who would abandon their ways. For decades, pirates were the scourge of the Atlantic, committing the most heinous acts of robbery, murder, and terror at sea. The result of the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) and the Whig Ascendancy in 1715 placed Britain in the prime opportunity to expand its commercial markets while its imperial rivals attempted to recover from war. This study explores the relationship between the campaign against pirates and state building by examining the British government’s efforts of publicizing its anti-piracy campaign through books, newspapers, and pamphlets in order to affirm state power that maintained the Whig Oligarchy. I argue that the discursive formation of piracy emerging in the public sphere reveals the state’s exercise of power in reclaiming political dominance over both the center and periphery. Pirates threatened the relationship between Britain and its colonies. Discourse became the principle means of changing the subjectivity of piracy, which influenced how the inhabitants of colonial communities came to regard pirates. By altering the piratical subject position—from legitimized marauders to criminal others—Britain would force the alignment of political values and customs between the periphery with the metropole, thereby, moving in the direction of realizing its larger goals of further imperial expansion.