On The Site

Harvard educational review.

Edited by Maya Alkateb-Chami, Jane Choi, Jeannette Garcia Coppersmith, Ron Grady, Phoebe A. Grant-Robinson, Pennie M. Gregory, Jennifer Ha, Woohee Kim, Catherine E. Pitcher, Elizabeth Salinas, Caroline Tucker, Kemeyawi Q. Wahpepah

Individuals

Institutions.

- Read the journal here

Journal Information

- ISSN: 0017-8055

- eISSN: 1943-5045

- Keywords: scholarly journal, education research

- First Issue: 1930

- Frequency: Quarterly

Description

The Harvard Educational Review (HER) is a scholarly journal of opinion and research in education. The Editorial Board aims to publish pieces from interdisciplinary and wide-ranging fields that advance our understanding of educational theory, equity, and practice. HER encourages submissions from established and emerging scholars, as well as from practitioners working in the field of education. Since its founding in 1930, HER has been central to elevating pieces and debates that tackle various dimensions of educational justice, with circulation to researchers, policymakers, teachers, and administrators.

Our Editorial Board is composed entirely of doctoral students from the Harvard Graduate School of Education who review all manuscripts considered for publication. For more information on the current Editorial Board, please see here.

A subscription to the Review includes access to the full-text electronic archives at our Subscribers-Only-Website .

Editorial Board

2023-2024 Harvard Educational Review Editorial Board Members

Maya Alkateb-Chami Development and Partnerships Editor, 2023-2024 Editor, 2022-2024 [email protected]

Maya Alkateb-Chami is a PhD student at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Her research focuses on the role of schooling in fostering just futures—specifically in relation to language of instruction policies in multilingual contexts and with a focus on epistemic injustice. Prior to starting doctoral studies, she was the Managing Director of Columbia University’s Human Rights Institute, where she supported and co-led a team of lawyers working to advance human rights through research, education, and advocacy. Prior to that, she was the Executive Director of Jusoor, a nonprofit organization that helps conflict-affected Syrian youth and children pursue their education in four countries. Alkateb-Chami is a Fulbright Scholar and UNESCO cultural heritage expert. She holds an MEd in Language and Literacy from Harvard University; an MSc in Education from Indiana University, Bloomington; and a BA in Political Science from Damascus University, and her research on arts-based youth empowerment won the annual Master’s Thesis Award of the U.S. Society for Education Through Art.

Jane Choi Editor, 2023-2025

Jane Choi is a second-year PhD student in Sociology with broad interests in culture, education, and inequality. Her research examines intra-racial and interracial boundaries in US educational contexts. She has researched legacy and first-generation students at Ivy League colleges, families served by Head Start and Early Head Start programs, and parents of pre-K and kindergarten-age children in the New York City School District. Previously, Jane worked as a Research Assistant in the Family Well-Being and Children’s Development policy area at MDRC and received a BA in Sociology from Columbia University.

Jeannette Garcia Coppersmith Content Editor, 2023-2024 Editor, 2022-2024 [email protected]

Jeannette Garcia Coppersmith is a fourth-year Education PhD student in the Human Development, Learning and Teaching concentration at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. A former public middle and high school mathematics teacher and department chair, she is interested in understanding the mechanisms that contribute to disparities in secondary mathematics education, particularly how teacher beliefs and biases intersect with the social-psychological processes and pedagogical choices involved in math teaching. Jeannette holds an EdM in Learning and Teaching from the Harvard Graduate School of Education where she studied as an Urban Scholar and a BA in Environmental Sciences from the University of California, Berkeley.

Ron Grady Editor, 2023-2025

Ron Grady is a second-year doctoral student in the Human Development, Learning, and Teaching concentration at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. His central curiosities involve the social worlds and peer cultures of young children, wondering how lived experience is both constructed within and revealed throughout play, the creation of art and narrative, and through interaction with/production of visual artifacts such as photography and film. Ron also works extensively with educators interested in developing and deepening practices rooted in reflection on, inquiry into, and translation of the social, emotional, and aesthetic aspects of their classroom ecosystems. Prior to his doctoral studies, Ron worked as a preschool teacher in New Orleans. He holds a MS in Early Childhood Education from the Erikson Institute and a BA in Psychology with Honors in Education from Stanford University.

Phoebe A. Grant-Robinson Editor, 2023-2024

Phoebe A. Grant-Robinson is a first year student in the Doctor of Education Leadership(EdLD) program at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Her ultimate quest is to position all students as drivers of their destiny. Phoebe is passionate about early learning and literacy. She is committed to ensuring that districts and school leaders, have the necessary tools to create equitable learning organizations that facilitate the academic and social well-being of all students. Phoebe is particularly interested in the intersection of homeless students and literacy. Prior to her doctoral studies, Phoebe was a Special Education Instructional Specialist. Supporting a portfolio of more than thirty schools, she facilitated the rollout of New York City’s Special Education Reform. Phoebe also served as an elementary school principal. She holds a BS in Inclusive Education from Syracuse University, and an MS in Curriculum and Instruction from Pace University.

Pennie M. Gregory Editor, 2023-2024

Pennie M. Gregory is a second-year student in the Doctor of Education Leadership (EdLD) program at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Pennie was born in Incheon, South Korea and raised in Gary, Indiana. She has decades of experience leading efforts to improve outcomes for students with disabilities first as a special education teacher and then as a school district special education administrator. Prior to her doctoral studies, Pennie helped to create Indiana’s first Aspiring Special Education Leadership Institute (ASELI) and served as its Director. She was also the Capacity Events Director for MelanatED Leaders, an organization created to support educational leaders of color in Indianapolis. Pennie has a unique perspective, having worked with members of the school community, with advocacy organizations, and supporting state special education leaders. Pennie holds an EdM in Education Leadership from Marian University.

Jennifer Ha Editor, 2023-2025

Jen Ha is a second-year PhD student in the Culture, Institutions, and Society concentration at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Her research explores how high school students learn to write personal narratives for school applications, scholarships, and professional opportunities amidst changing landscapes in college access and admissions. Prior to doctoral studies, Jen served as the Coordinator of Public Humanities at Bard Graduate Center and worked in several roles organizing academic enrichment opportunities and supporting postsecondary planning for students in New Haven and New York City. Jen holds a BA in Humanities from Yale University, where she was an Education Studies Scholar.

Woohee Kim Editor, 2023-2025

Woohee Kim is a PhD student studying youth activists’ civic and pedagogical practices. She is a scholar-activist dedicated to creating spaces for pedagogies of resistance and transformative possibilities. Shaped by her activism and research across South Korea, the US, and the UK, Woohee seeks to interrogate how educational spaces are shaped as cultural and political sites and reshaped by activists as sites of struggle. She hopes to continue exploring the intersections of education, knowledge, power, and resistance.

Catherine E. Pitcher Editor, 2023-2025

Catherine is a second-year doctoral student at Harvard Graduate School of Education in the Culture, Institutions, and Society program. She has over 10 years of experience in education in the US in roles that range from special education teacher to instructional coach to department head to educational game designer. She started working in Palestine in 2017, first teaching, and then designing and implementing educational programming. Currently, she is working on research to understand how Palestinian youth think about and build their futures and continues to lead programming in the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem. She holds an EdM from Harvard in International Education Policy.

Elizabeth Salinas Editor, 2023-2025

Elizabeth Salinas is a doctoral student in the Education Policy and Program Evaluation concentration at HGSE. She is interested in the intersection of higher education and the social safety net and hopes to examine policies that address basic needs insecurity among college students. Before her doctoral studies, Liz was a research director at a public policy consulting firm. There, she supported government, education, and philanthropy leaders by conducting and translating research into clear and actionable information. Previously, Liz served as a high school physics teacher in her hometown in Texas and as a STEM outreach program director at her alma mater. She currently sits on the Board of Directors at Leadership Enterprise for a Diverse America, a nonprofit organization working to diversify the leadership pipeline in the United States. Liz holds a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a master’s degree in higher education from the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Caroline Tucker Co-Chair, 2023-2024 Editor, 2022-2024 [email protected]

Caroline Tucker is a fourth-year doctoral student in the Culture, Institutions, and Society concentration at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Her research focuses on the history and organizational dynamics of women’s colleges as women gained entry into the professions and coeducation took root in the United States. She is also a research assistant for the Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery Initiative’s Subcommittee on Curriculum and the editorial assistant for Into Practice, the pedagogy newsletter distributed by Harvard University’s Office of the Vice Provost for Advances in Learning. Prior to her doctoral studies, Caroline served as an American politics and English teaching fellow in London and worked in college advising. Caroline holds a BA in History from Princeton University, an MA in the Social Sciences from the University of Chicago, and an EdM in Higher Education from the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Kemeyawi Q. Wahpepah Co-Chair, 2023-2024 Editor, 2022-2024 [email protected]

Kemeyawi Q. Wahpepah (Kickapoo, Sac & Fox) is a fourth-year doctoral student in the Culture, Institutions, and Society concentration at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Their research explores how settler colonialism is addressed in K-12 history and social studies classrooms in the United States. Prior to their doctoral studies, Kemeyawi taught middle and high school English and history for eleven years in Boston and New York City. They hold an MS in Middle Childhood Education from Hunter College and an AB in Social Studies from Harvard University.

Submission Information

Click here to view submission guidelines .

Contact Information

Click here to view contact information for the editorial board and customer service .

Subscriber Support

Individual subscriptions must have an individual name in the given address for shipment. Individual copies are not for multiple readers or libraries. Individual accounts come with a personal username and password for access to online archives. Online access instructions will be attached to your order confirmation e-mail.

Institutional rates apply to libraries and organizations with multiple readers. Institutions receive digital access to content on Meridian from IP addresses via theIPregistry.org (by sending HER your PSI Org ID).

Online access instructions will be attached to your order confirmation e-mail. If you have questions about using theIPregistry.org you may find the answers in their FAQs. Otherwise please let us know at [email protected] .

How to Subscribe

To order online via credit card, please use the subscribe button at the top of this page.

To order by phone, please call 888-437-1437.

Checks can be mailed to Harvard Educational Review C/O Fulco, 30 Broad Street, Suite 6, Denville, NJ 07834. (Please include reference to your subscriber number if you are renewing. Institutions must include their PSI Org ID or follow up with this information via email to [email protected] .)

Permissions

Click here to view permissions information.

Article Submission FAQ

Submissions, question: “what manuscripts are a good fit for her ”.

Answer: As a generalist scholarly journal, HER publishes on a wide range of topics within the field of education and related disciplines. We receive many articles that deserve publication, but due to the restrictions of print publication, we are only able to publish very few in the journal. The originality and import of the findings, as well as the accessibility of a piece to HER’s interdisciplinary, international audience which includes education practitioners, are key criteria in determining if an article will be selected for publication.

We strongly recommend that prospective authors review the current and past issues of HER to see the types of articles we have published recently. If you are unsure whether your manuscript is a good fit, please reach out to the Content Editor at [email protected] .

Question: “What makes HER a developmental journal?”

Answer: Supporting the development of high-quality education research is a key tenet of HER’s mission. HER promotes this development through offering comprehensive feedback to authors. All manuscripts that pass the first stage of our review process (see below) receive detailed feedback. For accepted manuscripts, HER also has a unique feedback process called casting whereby two editors carefully read a manuscript and offer overarching suggestions to strengthen and clarify the argument.

Question: “What is a Voices piece and how does it differ from an essay?”

Answer: Voices pieces are first-person reflections about an education-related topic rather than empirical or theoretical essays. Our strongest pieces have often come from educators and policy makers who draw on their personal experiences in the education field. Although they may not present data or generate theory, Voices pieces should still advance a cogent argument, drawing on appropriate literature to support any claims asserted. For examples of Voices pieces, please see Alvarez et al. (2021) and Snow (2021).

Question: “Does HER accept Book Note or book review submissions?”

Answer: No, all Book Notes are written internally by members of the Editorial Board.

Question: “If I want to submit a book for review consideration, who do I contact?”

Answer: Please send details about your book to the Content Editor at [email protected].

Manuscript Formatting

Question: “the submission guidelines state that manuscripts should be a maximum of 9,000 words – including abstract, appendices, and references. is this applicable only for research articles, or should the word count limit be followed for other manuscripts, such as essays”.

Answer: The 9,000-word limit is the same for all categories of manuscripts.

Question: “We are trying to figure out the best way to mask our names in the references. Is it OK if we do not cite any of our references in the reference list? Our names have been removed in the in-text citations. We just cite Author (date).”

Answer: Any references that identify the author/s in the text must be masked or made anonymous (e.g., instead of citing “Field & Bloom, 2007,” cite “Author/s, 2007”). For the reference list, place the citations alphabetically as “Author/s. (2007)” You can also indicate that details are omitted for blind review. Articles can also be blinded effectively by use of the third person in the manuscript. For example, rather than “in an earlier article, we showed that” substitute something like “as has been shown in Field & Bloom, 2007.” In this case, there is no need to mask the reference in the list. Please do not submit a title page as part of your manuscript. We will capture the contact information and any author statement about the fit and scope of the work in the submission form. Finally, please save the uploaded manuscript as the title of the manuscript and do not include the author/s name/s.

Invitations

Question: “can i be invited to submit a manuscript how”.

Answer: If you think your manuscript is a strong fit for HER, we welcome a request for invitation. Invited manuscripts receive one round of feedback from Editors before the piece enters the formal review process. To submit information about your manuscript, please complete the Invitation Request Form . Please provide as many details as possible. The decision to invite a manuscript largely depends on the capacity of current Board members and on how closely the proposed manuscript reflects HER publication scope and criteria. Once you submit the form, We hope to update you in about 2–3 weeks, and will let you know whether there are Editors who are available to invite the manuscript.

Review Timeline

Question: “who reviews manuscripts”.

Answer: All manuscripts are reviewed by the Editorial Board composed of doctoral students at Harvard University.

Question: “What is the HER evaluation process as a student-run journal?”

Answer: HER does not utilize the traditional external peer review process and instead has an internal, two-stage review procedure.

Upon submission, every manuscript receives a preliminary assessment by the Content Editor to confirm that the formatting requirements have been carefully followed in preparation of the manuscript, and that the manuscript is in accord with the scope and aim of the journal. The manuscript then formally enters the review process.

In the first stage of review, all manuscripts are read by a minimum of two Editorial Board members. During the second stage of review, manuscripts are read by the full Editorial Board at a weekly meeting.

Question: “How long after submission can I expect a decision on my manuscript?”

Answer: It usually takes 6 to 10 weeks for a manuscript to complete the first stage of review and an additional 12 weeks for a manuscript to complete the second stage. Due to time constraints and the large volume of manuscripts received, HER only provides detailed comments on manuscripts that complete the second stage of review.

Question: “How soon are accepted pieces published?”

Answer: The date of publication depends entirely on how many manuscripts are already in the queue for an issue. Typically, however, it takes about 6 months post-acceptance for a piece to be published.

Submission Process

Question: “how do i submit a manuscript for publication in her”.

Answer: Manuscripts are submitted through HER’s Submittable platform, accessible here. All first-time submitters must create an account to access the platform. You can find details on our submission guidelines on our Submissions page.

Our Best Education Articles of 2020

In February of 2020, we launched the new website Greater Good in Education , a collection of free, research-based and -informed strategies and practices for the social, emotional, and ethical development of students, for the well-being of the adults who work with them, and for cultivating positive school cultures. Little did we know how much more crucial these resources would become over the course of the year during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Now, as we head back to school in 2021, things are looking a lot different than in past years. Our most popular education articles of 2020 can help you manage difficult emotions and other challenges at school in the pandemic, all while supporting the social-emotional well-being of your students.

In addition to these articles, you can also find tips, tools, and recommended readings in two resource guides we created in 2020: Supporting Learning and Well-Being During the Coronavirus Crisis and Resources to Support Anti-Racist Learning , which helps educators take action to undo the racism within themselves, encourage their colleagues to do the same, and teach and support their students in forming anti-racist identities.

Here are the 10 best education articles of 2020, based on a composite ranking of pageviews and editors’ picks.

Can the Lockdown Push Schools in a Positive Direction? , by Patrick Cook-Deegan: Here are five ways that COVID-19 could change education for the better.

How Teachers Can Navigate Difficult Emotions During School Closures , by Amy L. Eva: Here are some tools for staying calm and centered amid the coronavirus crisis.

Six Online Activities to Help Students Cope With COVID-19 , by Lea Waters: These well-being practices can help students feel connected and resilient during the pandemic.

Help Students Process COVID-19 Emotions With This Lesson Plan , by Maurice Elias: Music and the arts can help students transition back to school this year.

How to Teach Online So All Students Feel Like They Belong , by Becki Cohn-Vargas and Kathe Gogolewski: Educators can foster belonging and inclusion for all students, even online.

How Teachers Can Help Students With Special Needs Navigate Distance Learning , by Rebecca Branstetter: Kids with disabilities are often shortchanged by pandemic classroom conditions. Here are three tips for educators to boost their engagement and connection.

How to Reduce the Stress of Homeschooling on Everyone , by Rebecca Branstetter: A school psychologist offers advice to parents on how to support their child during school closures.

Three Ways to Help Your Kids Succeed at Distance Learning , by Christine Carter: How can parents support their children at the start of an uncertain school year?

How Schools Are Meeting Social-Emotional Needs During the Pandemic , by Frances Messano, Jason Atwood, and Stacey Childress: A new report looks at how schools have been grappling with the challenges imposed by COVID-19.

Six Ways to Help Your Students Make Sense of a Divisive Election , by Julie Halterman: The election is over, but many young people will need help understanding what just happened.

Train Your Brain to Be Kinder (video), by Jane Park: Boost your kindness by sending kind thoughts to someone you love—and to someone you don’t get along with—with a little guidance from these students.

From Othering to Belonging (podcast): We speak with john a. powell, director of the Othering & Belonging Institute, about racial justice, well-being, and widening our circles of human connection and concern.

About the Author

Greater good editors.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Science is making anti-aging progress. But do we want to live forever?

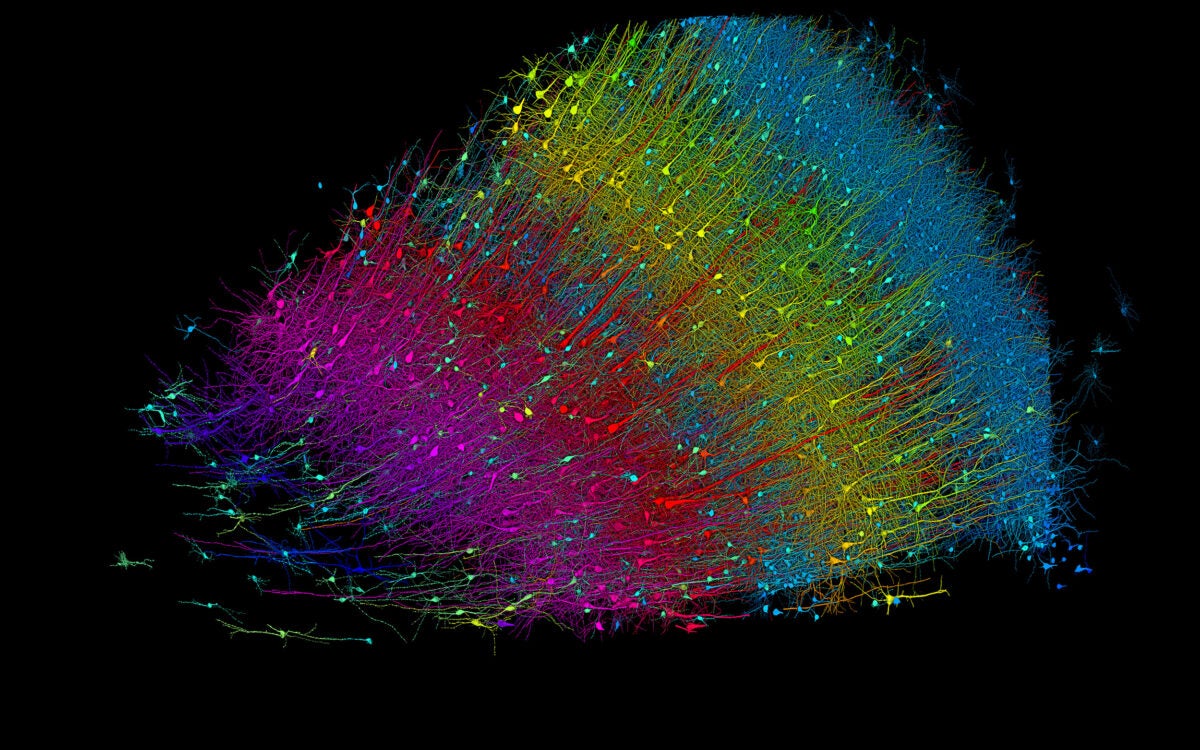

Epic science inside a cubic millimeter of brain

Complex questions, innovative approaches

What is ‘original scholarship’ in the age of ai.

Melissa Dell (from left), Alex Csiszar, and Latanya Sweeney.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Anne J. Manning

Harvard Staff Writer

Symposium considers how technology is changing academia

While moderating a talk on artificial intelligence last week, Latanya Sweeney posed a thought experiment. Picture three to five years from now. AI companies are continuing to scrape the internet for data to feed their large language models. But unlike today’s internet, which is largely human-generated content, most of that future internet’s content has been generated by … large language models.

The scenario is not farfetched considering the explosive growth of generative AI in the last two years, suggested the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and Harvard Kennedy School professor.

Sweeney’s panel was part of a daylong symposium on AI hosted by the FAS last week that considered questions such as: How are generative AI technologies such as ChatGPT disrupting what it means to own one’s work? How can AI be leveraged thoughtfully while maintaining academic and research integrity? Just how good are these large language model-based programs going to get? (Very, very good.)

“Here at the FAS, we’re in a unique position to explore questions and challenges that come from this new technology,” said Hopi Hoekstra , Edgerley Family Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, during her opening remarks. “Our community is full of brilliant thinkers, curious researchers, and knowledgeable scholars, all able to lend their variety of expertise to tackling the big questions in AI, from ethics to societal implications.”

In an all-student panel, philosophy and math concentrator Chinmay Deshpande ’24 compared the present moment to the advent of the internet, and how that revolutionary technology forced academic institutions to rethink how to test knowledge. “Regardless of what we think AI will look like down the line, I think it’s clear it’s starting to have an impact that’s qualitatively similar to the impact of the internet,” Deshpande said. “And thinking about pedagogy, we should think about AI along somewhat similar lines.”

Computer science concentrator and master’s degree student Naomi Bashkansky ’25, who is exploring AI safety issues with fellow students, urged Harvard to provide thought leadership on the implications of an AI-saturated world, in part by offering courses that integrate the basics of large language models into subjects like biology or writing.

Harvard Law School student Kevin Wei agreed.

“We’re not grappling sufficiently with the way the world will change, and especially the way the economy and labor market will change, with the rise of generative AI systems,” Wei said. “Anything Harvard can do to take a leading role in doing that … in discussions with government, academia, and civil society … I would like to see a much larger role for the University.”

The day opened with a panel on original scholarship, co-sponsored by the Mahindra Humanities Center and the Edmond & Lily Safra Center for Ethics . Panelists explored ethics of authorship in the age of instant access to information and blurred lines of citation and copyright, and how those considerations vary between disciplines.

David Joselit , the Arthur Kingsley Professor of Art, Film, and Visual Studies, said challenges wrought by AI have precedent in the history of art; the idea of “authorship” has been undermined in the modern era because artists have often focused on the idea as what counts as the artwork, rather than its physical execution. “It seems to me that AI is a mechanization of that kind of distribution of authorship,” Joselit said. He posed the idea that AI should be understood “as its own genre, not exclusively as a tool.”

Another symposium topic included a review of Harvard Library’s law, information policy, and AI survey research revealing how students are using AI for academic work. Administrators from across the FAS also shared examples of how they are experimenting with AI tools to enhance their productivity. Panelists from the Bok Center shared how AI has been used in teaching this year, and Harvard University Information Technology gave insight into tools it is building to support instructors.

Throughout the ground floor of the Northwest Building, where the symposium took place, was a poster fair keying off final projects from Sweeney’s course “Tech Science to Save the World,” in which students explored how scientific experimentation and technology can be used to solve real-world problems. Among the posters: “Viral or Volatile? TikTok and Democracy,” and “Campaign Ads in the Age of AI: Can Voters Tell the Difference?”

Students from the inaugural General Education class “ Rise of the Machines? ” capped the day, sharing final projects illustrating current and future aspects of generative AI.

Share this article

You might like.

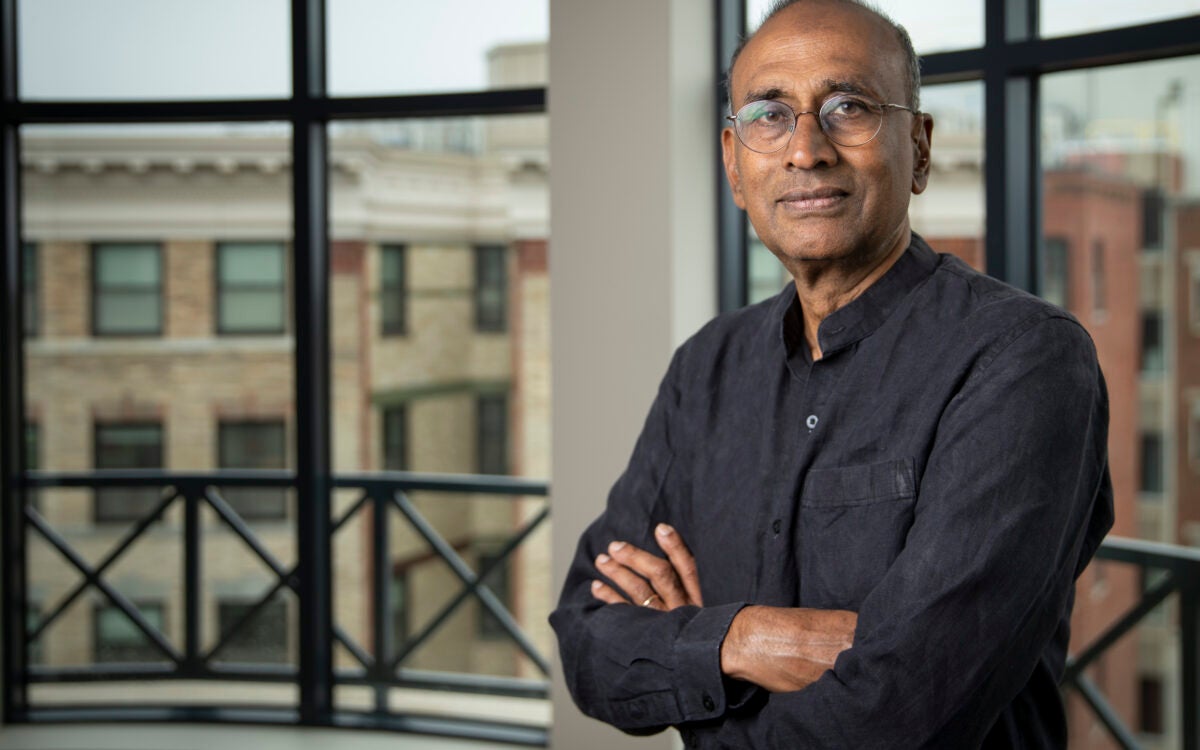

Nobel laureate details new book, which surveys research, touches on larger philosophical questions

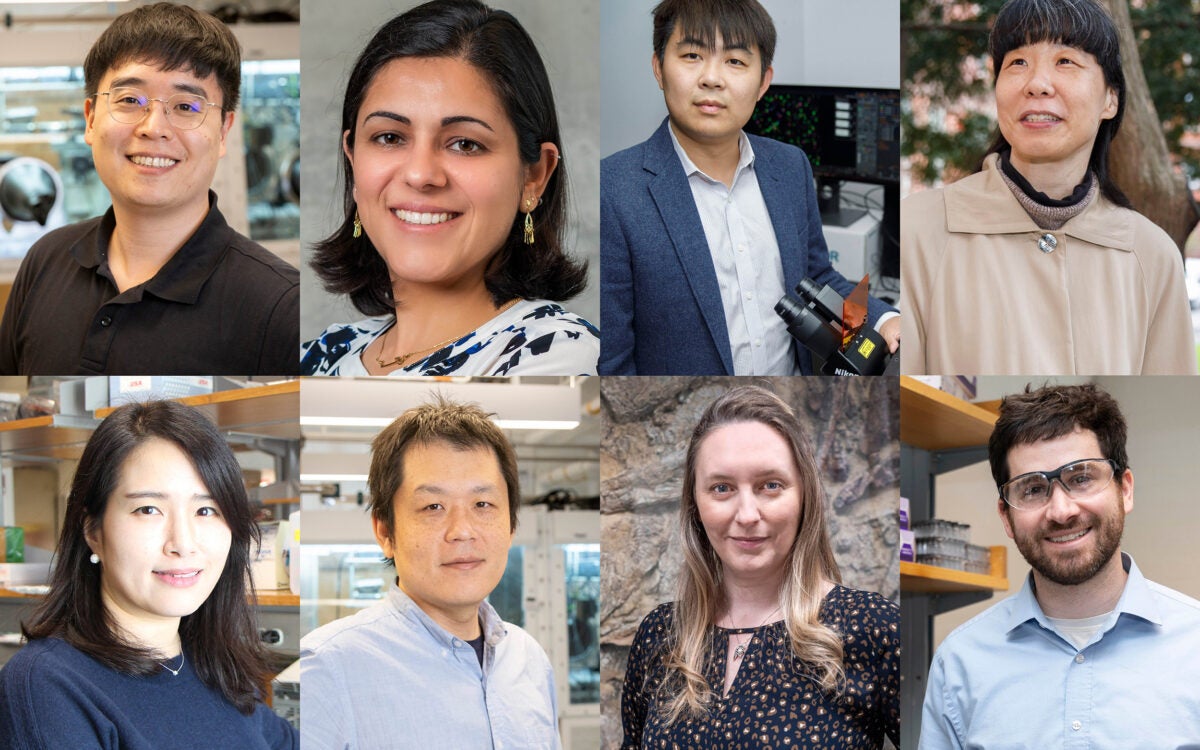

Researchers publish largest-ever dataset of neural connections

Seven projects awarded Star-Friedman Challenge grants

Excited about new diet drug? This procedure seems better choice.

Study finds minimally invasive treatment more cost-effective over time, brings greater weight loss

How far has COVID set back students?

An economist, a policy expert, and a teacher explain why learning losses are worse than many parents realize

Setting a new bar for online higher education

The education sector was among the hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. Schools across the globe were forced to shutter their campuses in the spring of 2020 and rapidly shift to online instruction. For many higher education institutions, this meant delivering standard courses and the “traditional” classroom experience through videoconferencing and various connectivity tools.

The approach worked to support students through a period of acute crisis but stands in contrast to the offerings of online education pioneers. These institutions use AI and advanced analytics to provide personalized learning and on-demand student support, and to accommodate student preferences for varying digital formats.

Colleges and universities can take a cue from the early adopters of online education, those companies and institutions that have been refining their online teaching models for more than a decade, as well as the edtechs that have entered the sector more recently. The latter organizations use educational technology to deliver online education services.

To better understand what these institutions are doing well, we surveyed academic research as well as the reported practices of more than 30 institutions, including both regulated degree-granting universities and nonregulated lifelong education providers. We also conducted ethnographic market research, during which we followed the learning journeys of 29 students in the United States and in Brazil, two of the largest online higher education markets in the world, with more than 3.3 million 1 Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, 2018, nces.ed.gov. and 2.3 million 2 School Census, Censo Escolar-INEP, 2019, ensobasico.inep.gov.br. online higher education students, respectively.

We found that, to engage most effectively with students, the leading online higher education institutions focus on eight dimensions of the learning experience. We have organized these into three overarching principles: create a seamless journey for students, adopt an engaging approach to teaching, and build a caring network (exhibit). In this article, we talk about these principles in the context of programs that are fully online, but they may be just as effective within hybrid programs in which students complete some courses online and some in person.

Create a seamless journey for students

The performance of the early adopters of online education points to the importance of a seamless journey for students, easily navigable learning platforms accessible from any device, and content that is engaging, and whenever possible, personalized. Some early adopters have even integrated their learning platforms with their institution’s other services and resources, such as libraries and financial-aid offices.

1. Build the education road map

In our conversations with students and experts, we learned that students in online programs—precisely because they are physically disconnected from traditional classroom settings—may need more direction, motivation, and discipline than students in in-person programs. The online higher education programs that we looked at help students build their own education road map using standardized tests, digital alerts, and time-management tools to regularly reinforce students’ progress and remind them of their goals.

Brazil’s Cogna Educação, for instance, encourages students to assess their baseline knowledge at the start of the course. 3 Digital transformation: A new culture to shape our future , Kroton 2018 Sustainability Report, Kroton Educacional, cogna.com.br. Such up-front diagnostics could be helpful in highlighting knowledge gaps and pointing students to relevant tools and resources, and may be especially helpful to students who have had unequal educational opportunities. A web-based knowledge assessment allows Cogna students to confirm their mastery of certain parts of a course, which, according to our research, can potentially boost their confidence and allow them to move faster through the course material.

At the outset of a course, leaders in online higher education can help students clearly understand the format and content, how they will use what they learn, how much time and effort is required, and how prepared they are for its demands.

The University of Michigan’s online Atlas platform, for instance, gives students detailed information about courses and curricula, including profiles of past students, sample reports and evaluations, and grade distributions, so they can make informed decisions about their studies. 4 Atlas, Center for Academic Innovation, University of Michigan, umich.edu. Another provider, Pluralsight, shares movie-trailer-style overviews of its course content and offers trial options so students can get a sense of what to expect before making financial commitments.

Meanwhile, some of the online doctoral students we interviewed have access to an interactive timeline and graduation calculator for each course, which help students understand each of the milestones and requirements for completing their dissertations. Breaking up the education process into manageable tasks this way can potentially ease anxiety, according to our interviews with education experts.

2. Enable seamless connections

Students may struggle to learn if they aren’t able to connect to learning platforms. Online higher education pioneers provide a single sign-on through which students can interact with professors and classmates and gain access to critical support services. Traditional institutions considering a similar model should remember that because high-speed and reliable internet are not always available, courses and program content should be structured so they can be accessed even in low-bandwidth situations or downloaded for offline use.

The technology is just one element of creating seamless connections. Since remote students may face a range of distractions, online-course content could benefit them by being more engaging than in-person courses. Online higher education pioneers allow students to study at their own pace through a range of channels and media, anytime and anywhere—including during otherwise unproductive periods, such as while in the waiting room at the doctor’s office. Coursera, for example, invites students to log into a personalized home page where they can review the status of their coursework, complete unfinished lessons, and access recommended “next content to learn” units. Brazilian online university Ampli Pitagoras offers content optimized for mobile devices that allows students to listen to lessons, contact tutors for help, or do quizzes from wherever they happen to be.

Adopt an engaging approach to teaching

The pioneers in online higher education we researched pair the “right” course content with the “right” formats to capture students’ attention. They incorporate real-world applications into their lesson plans, use adaptive learning tools to personalize their courses, and offer easily accessible platforms for group learning.

3. Offer a range of learning formats

The online higher education programs we reviewed incorporate group activities and collaboration with classmates—important hallmarks of the higher education experience—into their mix of course formats, offering both live classes and self-guided, on-demand lessons.

The Georgia Institute of Technology, for example, augments live lessons from faculty members in its online graduate program in data analytics with a collaboration platform where students can interact outside of class, according to a student we interviewed. Instructors can provide immediate answers to students’ questions via the platform or endorse students’ responses to questions from their peers. Instructors at Zhejiang University in China use live videoconferencing and chat rooms to communicate with more than 300 participants, assign and collect homework assignments, and set goals. 5 Wu Zhaohui, “How a top Chinese university is responding to coronavirus,” World Economic Forum, March 16, 2020, weforum.org.

The element of personalization is another area in which online programs can consider upping their ante, even in large student groups. Institutions could offer customized ways of learning online, whether via digital textbook, podcast, or video, ensuring that these materials are high quality and that the cost of their production is spread among large student populations.

Some institutions have invested in bespoke tools to facilitate various learning modes. The University of Michigan’s Center for Academic Innovation embeds custom-designed software into its courses to enhance the experience for both students and professors. 6 “Our mission & principles,” University of Michigan Center for Academic Innovation, ai.umich.edu. The school’s ECoach platform helps students in large classes navigate content when one-on-one interaction with instructors is difficult because of the sheer number of students. It also sends students reminders, motivational tips, performance reviews, and exam-preparation materials. 7 University of Michigan, umich.edu. Meanwhile, Minerva University focuses on a real-time online-class model that supports higher student participation and feedback and has built a platform with a “talk time” feature that lets instructors balance class participation and engage “back-row students” who may be inclined to participate less. 8 Samad Twemlow-Carter, “Talk Time,” Minerva University, minervaproject.com.

4. Ensure captivating experiences

Delivering education on digital platforms opens the potential to turn curricula into engaging and interactive journeys, and online education leaders are investing in content whose quality is on a par with high-end entertainment. Strayer University, for example, has recruited Emmy Award–winning film producers and established an in-house production unit to create multimedia lessons. The university’s initial findings show that this investment is paying off in increased student engagement, with 85 percent of learners reporting that they watch lessons from beginning to end, and also shows a 10 percent reduction in the student dropout rate. 9 Increased student engagement and success through captivating content , Strayer Studios outcomes report, Strayer University, studios.strategiced.com.

Other educators are attracting students not only with high-production values but influential personalities. Outlier provides courses in the form of high-quality videos that feature charismatic Ivy League professors and are shot in a format that reduces eye strain. 10 Outlier online course registration for Calculus I, outlier.org. The course content follows a storyline, and each course is presented as a crucial piece in an overall learning journey.

5. Utilize adaptive learning tools

Online higher education pioneers deliver adaptive learning using AI and analytics to detect and address individual students’ needs and offer real-time feedback and support. They can also predict students’ requirements, based on individuals’ past searches and questions, and respond with relevant content. This should be conducted according to the applicable personal data privacy regulations of the country where the institution is operating.

Cogna Educação, for example, developed a system that delivers real-time, personalized tutoring to more than 500,000 online students, paired with exercises customized to address specific knowledge gaps. 11 Digital transformation , 2018. Minerva University used analytics to devise a highly personalized feedback model, which allows instructors to comment and provide feedback on students’ online learning assignments and provide access to test scores during one-on-one feedback sessions. 12 “Maybe we need to rethink our assumptions about ‘online’ learning,” Minerva University, minervaproject.com. According to our research, instructors can also access recorded lessons during one-on-one sessions and provide feedback on student participation during class.

6. Include real-world application of skills

The online higher education pioneers use virtual reality (VR) laboratories, simulations, and games for students to practice skills in real-world scenarios within controlled virtual environments. This type of hands-on instruction, our research shows, has traditionally been a challenge for online institutions.

Arizona State University, for example, has partnered with several companies to develop a biology degree that can be obtained completely online. The program leverages VR technology that gives online students in its biological-sciences program access to a state-of-the-art lab. Students can zoom in to molecules and repeat experiments as many times as needed—all from the comfort of wherever they happen to be. 13 “ASU online biology course is first to offer virtual-reality lab in Google partnership,” Arizona State University, August 23, 2018, news.asu.edu. Meanwhile, students at Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas are using 3-D games to find innovative solutions to real-world problems—for instance, designing the post-COVID-19 campus experience. 14 Cleofé Vergara, “Learn by playing with Minecraft Education,” Innovación Educativa, July 13, 2021, innovacioneducativa.upc.edu.pe.

Some institutions have expanded the real-world experience by introducing online internships. Columbia University’s Virtual Internship Program, for example, was developed in partnership with employers across the United States and offers skills workshops and resources, as well as one-on-one career counseling. 15 Virtual Internship Program, Columbia University Center for Career Education, columbia.edu.

Create a caring network

Establishing interpersonal connections may be more difficult in online settings. Leading online education programs provide dedicated channels to help students with academic, personal, technological, administrative, and financial challenges and to provide a means for students to connect with each other for peer-to-peer support. Such programs are also using technologies to recognize signs of student distress and to extend just-in-time support.

7. Provide academic and nonacademic support

Online education pioneers combine automation and analytics with one-on-one personal interactions to give students the support they need.

Southern New Hampshire University (SNHU), for example, uses a system of alerts and communication nudges when its digital platform detects low student engagement. Meanwhile, AI-powered chatbots provide quick responses to common student requests and questions. 16 “SNHU turns student data into student success,” Southern New Hampshire University, May 2019, d2l.com. Strayer University has a virtual assistant named Irving that is accessible from every page of the university’s online campus website and offers 24/7 administrative support to students, from recommending courses to making personalized graduation projections. 17 “Meet Irving, the Strayer chatbot that saves students time,” Strayer University, October 31, 2019, strayer.edu.

Many of these pioneer institutions augment that digital assistance with human support. SNHU, for example, matches students in distress with personal coaches and tutors who can follow the students’ progress and provide regular check-ins. In this way, they can help students navigate the program and help cultivate a sense of belonging. 18 Academic advising, Southern New Hampshire University, 2021, snhu.edu. Similarly, Arizona State University pairs students with “success coaches” who give personalized guidance and counseling. 19 “Accessing your success coach,” Arizona State University, asu.edu.

8. Foster a strong community

The majority of students we interviewed have a strong sense of belonging to their academic community. Building a strong network of peers and professors, however, may be challenging in online settings.

To alleviate this challenge, leading online programs often combine virtual social events with optional in-person gatherings. Minerva University, for example, hosts exclusive online events that promote school rituals and traditions for online students, and encourages online students to visit its various locations for in-person gatherings where they can meet members of its diverse, dispersed student population. 20 “Join your extended family,” Minerva University, minerva.edu. SNHU’s Connect social gateway gives online-activity access to more than 15,000 members, and helps them interact within an exclusive university social network. Students can also join student organizations and affinity clubs virtually. 21 SNHU Connect, Southern New Hampshire University, snhuconnect.com.

Getting started: Designing the online journey

Building a distinctive online student experience requires significant time, effort, and investment. Most institutions whose practices we reviewed in this article took several years to understand student needs and refine their approaches to online education.

For those institutions in the early stages of rethinking their online offerings, the following three steps may be useful. Each will typically involve various functions within the institution, including but not necessarily limited to, academic management, IT, and marketing.

The diagnosis could be performed through a combination of focus groups and quantitative surveys, for example. It’s important that participants represent various student segments, which are likely to have different expectations, including young-adult full-time undergraduate students, working-adult part-time undergraduate students, and graduate students. The eight key dimensions outlined above may be helpful for structuring groups and surveys, in addition to self-evaluation of institution performance and potential benchmarks.

- Set a strategic vision for your online learning experience. The vision should be student-centric and link tightly to the institution’s overarching manifesto. The function leaders could evaluate the costs/benefits of each part of the online experience to ensure that the costs are realistic. The online model may vary depending on each school’s market, target audience, and tuition price point. An institution with high tuition, for example, is more likely to afford and provide one-on-one live coaching and student support, while an institution with lower tuition may need to rely more on automated tools and asynchronous interactions with students.

- Design the transformation journey. Institutions should expect a multiyear journey. Some may opt to outsource the program design and delivery to dedicated program-management companies. But in our experience, an increasing number of institutions are developing these capabilities internally, especially as online learning moves further into the mainstream and becomes a source of long-term strategic advantage.

We have found that leading organizations often begin with quick wins that significantly raise student experiences, such as stronger student support, integrated technology platforms, and structured course road maps. In parallel, they begin the incremental redesign of courses and delivery models, often focusing on key programs with the largest enrollments and tapping into advanced analytics for insights to refine these experiences.

Finally, institutions tackle key enabling factors, such as instructor onboarding and online-teaching training, robust technology infrastructure, and advanced-analytics programs that enable the institutions to understand which features of online education are performing well and generating exceptional learning experiences for their students.

The question is no longer whether the move to online will outlive the COVID-19 lockdowns but when online learning will become the dominant means for delivering higher education. As digital transformation accelerates across all industries, higher education institutions will need to consider how to develop their own online strategies.

Felipe Child is a partner in McKinsey’s Bogotá office, Marcus Frank is a senior practice expert in the São Paulo office, Mariana Lef is an associate in the Buenos Aires office, and Jimmy Sarakatsannis is a partner in the Washington, DC, office.

References to specific products, companies, or organizations are solely for information purposes and do not constitute any endorsement or recommendation.

This article was edited by Justine Jablonska, an editor in the New York office.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

How to transform higher-education institutions for the long term

Higher education in the post-COVID world

Reimagining higher education in the United States

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The relationship between education and health: reducing disparities through a contextual approach

Anna zajacova.

Western University

Elizabeth M. Lawrence

University of North Carolina

Adults with higher educational attainment live healthier and longer lives compared to their less educated peers. The disparities are large and widening. We posit that understanding the educational and macro-level contexts in which this association occurs is key to reducing health disparities and improving population health. In this paper, we briefly review and critically assess the current state of research on the relationship between education and health in the United States. We then outline three directions for further research: We extend the conceptualization of education beyond attainment and demonstrate the centrality of the schooling process to health; We highlight the dual role of education a driver of opportunity but also a reproducer of inequality; We explain the central role of specific historical socio-political contexts in which the education-health association is embedded. This research agenda can inform policies and effective interventions to reduce health disparities and improve health of all Americans.

URGENT NEED FOR NEW DIRECTIONS IN EDUCATION-HEALTH RESEARCH

Americans have worse health than people in other high-income countries, and have been falling further behind in recent decades ( 137 ). This is partially due to the large health inequalities and poor health of adults with low education ( 84 ). Understanding the health benefits of education is thus integral to reducing health disparities and improving the well-being of 21 st century populations. Despite tremendous prior research, critical questions about the education-health relationship remain unanswered, in part because education and health are intertwined over the lifespans within and across generations and are inextricably embedded in the broader social context.

We posit that to effectively inform future educational and heath policy, we need to capture education ‘in action’ as it generates and constrains opportunity during the early lifespans of today’s cohorts. First, we need to expand our operationalization of education beyond attainment to consider the long-term educational process that precedes the attainment and its effect on health. Second, we need to re-conceptualize education as not only a vehicle for social success, valuable resources, and good health, but also as an institution that reproduces inequality across generations. And third, we argue that investigators need to bring historical, social and policy contexts into the heart of analyses: how does the education-health association vary across place and time, and how do political forces influence that variation?

During the past several generations, education has become the principal pathway to financial security, stable employment, and social success ( 8 ). At the same time, American youth have experienced increasingly unequal educational opportunities that depend on the schools they attend, the neighborhoods they live in, the color of their skin, and the financial resources of their family. The decline in manufacturing and rise of globalization have eroded the middle class, while the increasing returns to higher education magnified the economic gaps among working adults and families ( 107 ). In addition to these dramatic structural changes, policies that protected the welfare of vulnerable groups have been gradually eroded or dismantled ( 129 ). Together, these changes triggered a precipitous growth of economic and social inequalities in the American society ( 17 ; 106 ).

Unsurprisingly, health disparities grew hand in hand with the socio-economic inequalities. Although the average health of the US population improved over the past decades ( 67 ; 85 ), the gains largely went to the most educated groups. Inequalities in health ( 53 ; 77 ; 99 ) and mortality ( 86 ; 115 ) increased steadily, to a point where we now see an unprecedented pattern: health and longevity are deteriorating among those with less education ( 92 ; 99 ; 121 ; 143 ). With the current focus of the media, policymakers, and the public on the worrisome health patterns among less-educated Americans ( 28 ; 29 ), as well as the growing recognition of the importance of education for health ( 84 ), research on the health returns to education is at a critical juncture. A comprehensive research program is needed to understand how education and health are related, in order to identify effective points of intervention to improve population health and reduce disparities.

The article is organized in two parts. First, we review the current state of research on the relationship between education and health. In broad strokes, we summarize the theoretical and empirical foundations of the education-health relationship and critically assess the literature on the mechanisms and causal influence of education on health. In the second part, we highlight gaps in extant research and propose new directions for innovative research that will fill these gaps. The enormous breadth of the literature on education and health necessarily limits the scope of the review in terms of place and time; we focus on the United States and on findings generated during the rapid expansion of the education-health research in the past 10–15 years. The terms “education” and “schooling” are used interchangeably. Unless we state otherwise, both refer to attained education, whether measured in completed years or credentials. For references, we include prior review articles where available, seminal papers, and recent studies as the best starting points for further reading.

THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN EDUCATION AND HEALTH

Conceptual toolbox for examining the association.

Researchers have generally drawn from three broad theoretical perspectives to hypothesize the relationship between education and health. Much of the education-health research over the past two decades has been grounded in the Fundamental Cause Theory ( 75 ). The FCT posits that social factors such as education are ‘fundamental’ causes of health and disease because they determine access to a multitude of material and non-material resources such as income, safe neighborhoods, or healthier lifestyles, all of which protect or enhance health. The multiplicity of pathways means that even as some mechanisms change or become less important, other mechanisms will continue to channel the fundamental dis/advantages into differential health ( 48 ). The Human Capital Theory (HCT), borrowed from econometrics, conceptualizes education as an investment that yields returns via increased productivity ( 12 ). Education improves individuals’ knowledge, skills, reasoning, effectiveness, and a broad range of other abilities, which can be utilized to produce health ( 93 ). The third approach, the Signaling or Credentialing perspective ( 34 ; 125 ) has been used to explain the observed large discontinuities in health at 12 or 16 years of schooling, typically associated with the receipt of a high school and college degrees, respectively. This perspective views earned credentials as a potent signal about one’s skills and abilities, and emphasizes the economic and social returns to such signals. Thus all three perspectives postulate a causal relationship between education and health and identify numerous mechanisms through which education influences health. The HCT specifies the mechanisms as embodied skills and abilities, FCT emphasizes the dynamism and flexibility of mechanisms, and credentialism identifies social responses to educational attainment. All three theoretical approaches, however, operationalize the complex process of schooling solely in terms of attainment and thus do not focus on differences in educational quality, type, or other institutional factors that might independently influence health. They also focus on individual-level factors: individual attainment, attainment effects, and mechanisms, and leave out the social context in which the education and health processes are embedded.

Observed associations between education and health

Empirically, hundreds of studies have documented “the gradient” whereby more schooling is linked with better health and longer life. A seminal 1973 book by Kitagawa and Hauser powerfully described large differences in mortality by education in the United States ( 71 ), a finding that has since been corroborated in numerous studies ( 31 ; 42 ; 46 ; 109 ; 124 ). In the following decades, nearly all health outcomes were also found strongly patterned by education. Less educated adults report worse general health ( 94 ; 141 ), more chronic conditions ( 68 ; 108 ), and more functional limitations and disability ( 118 ; 119 ; 130 ; 143 ). Objective measures of health, such as biological risk levels, are similarly correlated with educational attainment ( 35 ; 90 ; 140 ), showing that the gradient is not a function of differential reporting or knowledge.

The gradient is evident in men and women ( 139 ) and among all race/ethnic groups ( 36 ). However, meaningful group differences exist ( 60 ; 62 ; 91 ). In particular, education appears to have stronger health effects for women than men ( 111 ) and stronger effects for non-Hispanic whites than minority adults ( 134 ; 135 ) even if the differences are modest for some health outcomes ( 36 ). The observed variations may reflect systematic social differences in the educational process such as quality of schooling, content, or institutional type, as well as different returns to educational attainment in the labor market across population groups ( 26 ). At the same time, the groups share a common macro-level social context, which may underlie the gradient observed for all.

To illustrate the gradient, we analyzed 2002–2016 waves of the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from adults aged 25–64. Figure 1 shows the levels of three health outcomes across educational attainment levels in six major demographic groups predicted at age 45. Three observations are noteworthy. First, the gradient is evident for all outcomes and in all race/ethnic/gender groups. Self-rated health exemplifies the staggering magnitude of the inequalities: White men and women without a high school diploma have about 57% chance of reporting fair or poor health, compared to just 9% for college graduates. Second, there are major group differences as well, both in the predicted levels of health problems, as well as in the education effects. The latter are not necessarily visible in the figures but the education effects are stronger for women and weaker for non-white adults as prior studies showed (table with regression model results underlying the prior statement is available from the authors). Third, an intriguing exception pertains to adults with “some college,” whose health is similar to high school graduates’ in health outcomes other than general health, despite their investment in and exposure to postsecondary education. We discuss this anomaly below.

Predicted Probability of Health Problems

Source: 2002–2016 NHIS Survey, Adults Age 25–64

Pathways through which education impacts health

What explains the improved health and longevity of more educated adults? The most prominent mediating mechanisms can be grouped into four categories: economic, health-behavioral, social-psychological, and access to health care. Education leads to better, more stable jobs that pay higher income and allow families to accumulate wealth that can be used to improve health ( 93 ). The economic factors are an important link between schooling and health, estimated to account for about 30% of the correlation ( 36 ). Health behaviors are undoubtedly an important proximal determinant of health but they only explain a part of the effect of schooling on health: adults with less education are more likely to smoke, have an unhealthy diet, and lack exercise ( 37 ; 73 ; 105 ; 117 ). Social-psychological pathways include successful long-term marriages and other sources of social support to help cope with stressors and daily hassles ( 128 ; 131 ). Interestingly, access to health care, while important to individual and population health overall, has a modest role in explaining health inequalities by education ( 61 ; 112 ; 133 ), highlighting the need to look upstream beyond the health care system toward social factors that underlie social disparities in health. Beyond these four groups of mechanisms that have received the most attention by investigators, many others have been examined, such as stress, cognitive and noncognitive skills, or environmental exposures ( 11 ; 43 ). Several excellent reviews further discuss mechanisms ( 2 ; 36 ; 66 ; 70 ; 93 ).

Causal interpretation of the education-health association

A burgeoning number of studies used innovative approaches such as natural experiments and twin design to test whether and how education causally affects health. These analyses are essential because recommendations for educational policies, programs, and interventions seeking to improve population health hinge on the causal impact of schooling on health outcomes. Overall, this literature shows that attainment, measured mostly in completed years of schooling, has a causal impact on health across numerous (though not all) contexts and outcomes.

Natural experiments take advantage of external changes that affect attainment but are unrelated to health, such as compulsory education reforms that raise the minimum years of schooling within a given population. A seminal 2005 study focused on increases in compulsory education between 1915 and 1939 across US states and found that a year of schooling reduced mortality by 3.6% ( 78 ). A re-analysis of the data indicated that taking into account state-level mortality trends rendered the mortality effects null but it also identified a significant and large causal effect on general health ( 88 ). A recent study of a large sample of older Americans reported a similar pattern: a substantial causal effect of education for self-rated health but not for mortality ( 47 ). School reform studies outside the US have reported compelling ( 122 ) or modest but significant ( 32 ) effects of schooling on health, although some studies have found nonsignificant ( 4 ), or even negative effects ( 7 ) for a range of health outcomes.

Twin design studies compare the health of twins with different levels of education. This design minimizes the influence of family resources and genetic differences in skills and health, especially for monozygotic twins, and thus serves to isolate the effect of schooling. In the US, studies using this design generated robust evidence of a causal effect of education on self-rated health ( 79 ), although some research has identified only modest ( 49 ) or not significant ( 3 ; 55 ) effects for other physical and mental health outcomes. Studies drawing on the large twin samples outside of the US have similarly found strong causal effects for mortality ( 80 ) and health ( 14 ; 16 ; 51 ) but again some analyses yielded no causal effects on health ( 13 ; 83 ) or health behaviors ( 14 ). Beyond our brief overview, readers may wish consult additional comprehensive reviews of the causal studies ( 40 ; 45 ; 89 ).

The causal studies add valuable evidence that educational attainment impacts adult health and mortality, even considering some limitations to their internal validity ( 15 ; 88 ). To improve population health and reduce health disparities, however, they should be viewed as a starting point to further research. First, the findings do not show how to improve the quality of schooling or its quantity for in the aggregate population, or how to overcome systematic intergenerational and social differences in educational opportunities. Second, their findings do take into account contexts and conditions in which educational attainment might be particularly important for health. In fact, the variability in the findings may be attributable to the stark differences in contexts across the studies, which include countries characterized by different political systems, different population groups, and birth cohorts ranging from the late 19 th to late 20 th centuries that were exposed to education at very different stages of the educational expansion process ( 9 ).

TOWARD A SOCIALLY-EMBEDDED UNDERSTANDING OF THE EDUCATION-HEALTH RELATIONSHIP

To date, the extensive research we briefly reviewed above has identified substantial health benefits of educational attainment in most contexts in today’s high-income countries. Still, many important questions remain unanswered. We outline three critical directions to gain a deeper understanding of the education-health relationship with particular relevance for policy development. All three directions shift the education-health paradigm to consider how education and health are embedded in life course and social contexts.

First, nearly universally, the education-health literature conceptualizes and operationalizes education in terms of attainment, as years of schooling or completed credentials. However, attainment is only the endpoint, although undoubtedly important, of an extended and extensive process of formal schooling, where institutional quality, type, content, peers, teachers, and many other individual, institutional, and interpersonal factors shape lifecourse trajectories of schooling and health. Understanding the role of the schooling process in health outcome is relevant for policy because it can show whether interventions should be aimed at increasing attainment, or whether it is more important to increase quality, change content, or otherwise improve the educational process at earlier stages for maximum health returns. Second, most studies have implicitly or explicitly treated educational attainment as an exogenous starting point, a driver of opportunities in adulthood. However, education also functions to reproduce inequality across generations. The explicit recognition of the dual function of education is critical to developing education policies that would avoid unintended consequence of increasing inequalities. And third, the review above indicates substantial variation in the education-health association across different historical and social contexts. Education and health are inextricably embedded in these contexts and analyses should therefore include them as fundamental influences on the education-health association. Research on contextual variation has the potential to identify contextual characteristics and even specific policies that exacerbate or reduce educational disparities in health.

We illustrate the key conceptual components of future research into the education-health relationship in Figure 2 . Important intergenerational and individual socio-demographic factors shape educational opportunities and educational trajectories, which are directly related to and captured in measures of educational attainment. This longitudinal and life course process culminates in educational disparities in adult health and mortality. Importantly, the macro-level context underlies every step of this process, shaping each of the concepts and their relationships.

Enriching the conceptualization of educational attainment

In most studies of the education-health associations, educational attainment is modeled using years of schooling, typically specified as a continuous covariate, effectively constraining each additional year to have the same impact. A growing body of research has substituted earned credentials for years. Few studies, however, have considered how the impact of additional schooling is likely to differ across the educational attainment spectrum. For example, one additional year of education compared to zero years may be life-changing by imparting basic literacy and numeracy skills. The completion of 14 rather than 13 years (without the completion of associated degree) could be associated with better health through the accumulation of additional knowledge and skills as well, or perhaps could be without health returns, if it is associated with poor grades, stigma linked to dropping out of college, or accumulated debt ( 63 ; 76 ). Examining the functional form of the education-health association can shed light on how and why education is beneficial for health ( 70 ). For instance, studies found that mortality gradually declines with years of schooling at low levels of educational attainment, with large discontinuities at high school and college degree attainment ( 56 ; 98 ). Such findings can point to the importance of completing a degree, not just increasing the quantity (years) of education. Examining mortality, however, implicitly focused on cohorts who went to school 50–60 years ago, within very different educational and social contexts. For findings relevant to current education policies, we need to focus on examining more recent birth cohorts.

A particularly provocative and noteworthy aspect of the functional form is the attainment group often identified as “some college:” adults who attended college but did not graduate with a four-year degree. Postsecondary educational experiences are increasingly central to the lives of American adults ( 27 ) and college completion has become the minimum requirement for entry into middle class ( 65 ; 87 ). Among high school graduates, over 70% enroll in college ( 22 ) but the majority never earn a four-year degree ( 113 ). In fact,, the largest education-attainment group among non-elderly US adults comprises the 54 million adults (29% of total) with some college or associate’s degree ( 113 ). However, as in Figure 1 , this group often defies the standard gradient in health. Several recent studies have found that the health returns to their postsecondary investments are marginal at best ( 110 ; 123 ; 142 ; 144 ). This finding should spur new research to understand the outcomes of this large population group, and to glean insights into the health returns to the postsecondary schooling process. For instance, in the absence of earning a degree, is greater exposure to college education in terms of semesters or earned credits associated with better health or not? How do the returns to postsecondary schooling differ across the heterogeneous institutions ranging from selective 4-year to for-profit community colleges? How does accumulated college debt influence both dropout and later health? Can we identify circumstances under which some college education is beneficial for health? Understanding the health outcomes for this attainment group can shed light on the aspects of education that are most important for improving health.

A related point pertains to the reliability and validity of self-reported educational attainment. If a respondent reports 16 completed years of education, for example, are they carefully counting the number of years of enrollment, or is 16 shorthand for “completed college”? And, is 16 years the best indicator of college completion in the current context when the median time to earn a four-year degree exceeds 5 years ( 30 )? And, is longer time in college given a degree beneficial for health or does it signify delayed or disrupted educational pathways linked to weaker health benefits ( 132 )? How should we measure part-time enrollment? As studies begin to adjudicate between the health effects of years versus credentials ( 74 ) in the changing landscape of increasingly ‘nontraditional’ pathways through college ( 132 ), this measurement work will be necessary for unbiased and meaningful analyses. An in-depth understanding may necessitate primary data collection and qualitative studies. A feasible direction available with existing data such as the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97) is to assess earned college credits and grades rather than years of education beyond high school.

As indicated in Figure 2 , beyond a more in-depth usage of the attainment information, we argue that more effective conceptualization of the education-health relationship as a developmental life course process will lead to important findings. For instance, two studies published in 2016 used the NLSY97 data to model how gradual increases in education predict within-individual changes in health ( 39 ; 81 ). Both research teams found that gradual accumulation of schooling quantity over time was not associated with gradual improvements in health. The investigators interpreted the null findings as an absence of causal effects of education on health, especially once they included important confounders (defined as cognitive and noncognitive skills and social background). Alternatively, perhaps the within-individual models did not register health because education is a long-term, developing trajectory that cannot be reduced to point-in-time changes in exposure. Criticisms about the technical aspects of theses studies notwithstanding ( 59 ), we believe that these studies and others like them, which wrestle with the question of how to capture education as a long-term process grounded in the broader social context, and how this process is linked to adult health, are desirable and necessary.

Education as (re)producer of inequality

The predominant theoretical framework for studying education and health focuses on how education increases skills, improves problem-solving, enhances employment prospects, and thus opens access to other resources. In sociology, however, education is viewed not (only) as increasing human capital but as a “sieve more than a ladder” ( 126 ), an institution that reproduces inequality across generations ( 54 ; 65 ; 103 ; 114 ). The mechanisms of the reproduction of inequality are multifarious, encompassing systematic differences in school resources, quality of instruction, academic opportunities, peer influences, or teacher expectations ( 54 ; 114 ; 132 ). The dual role of education, both engendering and constraining social opportunities, has been recognized from the discipline’s inception ( 52 ) and has remained the dominant perspective in sociology of education ( 18 ; 126 ). Health disparities research, which has largely dismissed the this perspective as “specious” ( 93 ), could benefit from pivoting toward this complex sociological paradigm.

As demonstrated in Figure 2 , parental SES and other background characteristics are key social determinants that set the stage for one’s educational experiences ( 20 ; 120 ). These characteristics, however, shape not just attainment, but the entire educational and social trajectories that drive and result in particular attainment ( 21 ; 69 ). Their effects range from the differential quality and experiences in daycare or preschool settings ( 6 ), K-12 education ( 24 ; 136 ), as well as postsecondary schooling ( 5 ; 127 ). As a result of systematically different experiences of schooling over the early life course stratified by parental SES, children of low educated parents are unlikely to complete higher education: over half of individuals with college degrees by age 24 came from families in the top quartile of family income compared to just 10% in the bottom quartile ( 23 ).

Unfortunately, prior research has generally operationalized the differences in educational opportunities as confounders of the education-health association or as “selection bias” to be statistically controlled, or best as a moderating influence ( 10 ; 19 ). Rather than remove the important life course effects from the equation, studies that seek to understand how educational and health differences unfold over the life course, and even across generations could yield greater insight ( 50 ; 70 ). A life course, multigenerational approach can provide important recommendations for interventions seeking to avoid the unintended consequence of increasing disparities. Insofar as socially advantaged individuals are generally better positioned to take advantage of interventions, research findings can be used to ensure that policies and programs result in decreasing, rather than unintentionally widening, educational and health disparities.

Education and health in social context