Libraries | Research Guides

Technical reports, technical reports: a definition, search engines & databases, multi-disciplinary technical report repositories, topical technical report repositories.

"A technical report is a document that describes the process, progress, or results of technical or scientific research or the state of a technical or scientific research problem. It might also include recommendations and conclusions of the research." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technical_report

Technical reports are produced by corporations, academic institutions, and government agencies at all levels of government, e.g. state, federal, and international. Technical reports are not included in formal publication and distribution channels and therefore fall into the category of grey literature .

- Science.gov Searches over 60 databases and over 2,200 scientific websites hosted by U.S. federal government agencies. Not limited to tech reports.

- WorldWideScience.org A global science gateway comprised of national and international scientific databases and portals, providing real-time searching and translation of globally-dispersed multilingual scientific literature.

- Open Grey System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe, is your open access to 700.000 bibliographical references. more... less... OpenGrey covers Science, Technology, Biomedical Science, Economics, Social Science and Humanities.

- National Technical Reports Library (NTRL) This link opens in a new window The National Technical Reports Library provides indexing and access to a collection of more than two million historical and current government technical reports of U.S. government-sponsored research. Full-text available for 700,000 of the 2.2 million items described. Dates covered include 1900-present.

- Argonne National Lab: Scientific Publications While sponsored by the US Dept of Energy, research at Argonne National Laboratory is wide ranging (see Research Index )

- Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC) The Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC®) has served the information needs of the Defense community for more than 65 years. It provides technical research, development, testing & evaluation information; including but not limited to: journal articles, conference proceedings, test results, theses and dissertations, studies & analyses, and technical reports & memos.

- HathiTrust This repository of books digitized by member libraries includes a large number of technical reports. Search by keywords, specific report title, or identifiers.

- Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (LBNL) LBNL a multiprogram science lab in the national laboratory system supported by the U.S. Department of Energy through its Office of Science. It is managed by the University of California and is charged with conducting unclassified research across a wide range of scientific disciplines.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) NIST is one of the nation's oldest physical science laboratories.

- RAND Corporation RAND's research and analysis address issues that impact people around the world including security, health, education, sustainability, growth, and development. Much of this research is carried out on behalf of public and private grantors and clients.

- TRAIL Technical Report Archive & Image Library Identifies, acquires, catalogs, digitizes and provides unrestricted access to U.S. government agency technical reports. TRAIL is a membership organization . more... less... Majority of content is pre-1976, but some reports after that date are included.

Aerospace / Aviation

- Contrails 20th century aerospace research, hosted at the Illinois Institute of Technology

- Jet Propulsion Laboratory Technical Reports Server repository for digital copies of technical publications authored by JPL employees. It includes preprints, meeting papers, conference presentations, some articles, and other publications cleared for external distribution from 1992 to the present.

- NTRS - NASA Technical Reports Server The NASA STI Repository (also known as the NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS)) provides access to NASA metadata records, full-text online documents, images, and videos. The types of information included are conference papers, journal articles, meeting papers, patents, research reports, images, movies, and technical videos – scientific and technical information (STI) created or funded by NASA. Includes NTIS reports.

Computing Research

- Computing Research Repository

- IBM Technical Paper Archive

- Microsoft Research

- INIS International Nuclear Information System One of the world's largest collections of published information on the peaceful uses of nuclear science and technology.

- Oak Ridge National Laboratory Research Library Primary subject areas covered include chemistry, physics, materials science, biological and environmental sciences, computer science, mathematics, engineering, nuclear technology, and homeland security.

- OSTI.gov The primary search tool for DOE science, technology, and engineering research and development results more... less... over 70 years of research results from DOE and its predecessor agencies. Research results include journal articles/accepted manuscripts and related metadata; technical reports; scientific research datasets and collections; scientific software; patents; conference and workshop papers; books and theses; and multimedia

- OSTI Open Net Provides access to over 495,000 bibliographic references and 147,000 recently declassified documents, including information declassified in response to Freedom of Information Act requests. In addition to these documents, OpenNet references older document collections from several DOE sources.

Environment

- National Service Center for Environmental Publications From the Environmental Protection Agency

- US Army Corp of Engineers (USACE) Digital Library See in particular the option to search technical reports by the Waterways Experiment Station, Engineering Research and Development Center, and districts .

- National Clearinghouse for Science, Technology and the Law (NCSTL) Forensic research at the intersection of science, technology and law.

Transportation

- ROSA-P National Transportation Library Full-text digital publications, datasets, and other resources. Legacy print materials that have been digitized are collected if they have historic, technical, or national significance.

- Last Updated: Jul 13, 2022 11:46 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/techreports

- Research Guides

- University Libraries

- Advanced Research Topics

Technical Reports

- What is a Technical report?

- Find Technical Reports

- Print & Microform Tech Reports in the Library

- Author Profile

What is a Technical Report?

What is a Technical Report?

"A technical report is a document written by a researcher detailing the results of a project and submitted to the sponsor of that project." TRs are not peer-reviewed unless they are subsequently published in a peer-review journal.

Characteristics (TRs vary greatly): Technical reports ....

- may contain data, design criteria, procedures, literature reviews, research history, detailed tables, illustrations/images, explanation of approaches that were unsuccessful.

- may be published before the corresponding journal literature; may have more or different details than its subsequent journal article.

- may contain less background information since the sponsor already knows it

- classified and export controlled reports

- may contain obscure acronyms and codes as part of identifying information

Disciplines:

- Physical sciences, engineering, agriculture, biomedical sciences, and the social sciences. education etc.

Documents research and development conducted by:

- government agencies (NASA, Department of Defense (DoD) and Department of Energy (DOE) are top sponsors of research

- commercial companies

- non-profit, non-governmental organizations

- Educational Institutions

- Issued in print, microform, digital

- Older TRs may have been digitized and are available in fulltext on the Intranet

- Newer TRs should be born digital

Definition used with permission from Georgia Tech. Other sources: Pinelli & Barclay (1994).

- Nation's Report Card: State Reading 2002, Report for Department of Defense Domestic Dependent Elementary and Secondary Schools. U.S. Department of Education Institute of Education Sciences The National Assessment of Educational Progress Reading 2002 The Nation’s

- Study for fabrication, evaluation, and testing of monolayer woven type materials for space suit insulation NASA-CR-166139, ACUREX-TR-79-156. May 1979. Reproduced from the microfiche.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Find Technical Reports >>

- Last Updated: Sep 1, 2023 11:06 AM

- URL: https://tamu.libguides.com/TR

Penn State University Libraries

Technical reports, recognizing technical reports, recommendations for finding technical reports, databases with technical reports, other tools for finding technical reports.

- Direct Links to Organizations with Technical Reports

- Techical report collections at Penn State

- How to Write

Engineering Instruction Librarian

Engineering Librarian

Technical reports describe the process, progress, or results of technical or scientific research and usually include in-depth experimental details, data, and results. Technical reports are usually produced to report on a specific research need and can serve as a report of accountability to the organization funding the research. They provide access to the information before it is published elsewhere. Technical Reports are usually not peer reviewed. They need to be evaluated on how the problem, research method, and results are described.

A technical report citation will include a report number and will probably not have journal name.

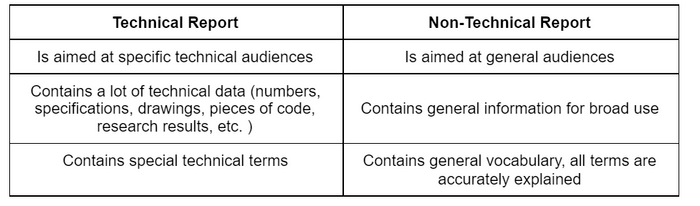

Technical reports can be divided into two general categories:

- Non-Governmental Reports- these are published by companies and engineering societies, such as Lockheed-Martin, AIAA (American Institute of Aeronautical and Astronautics), IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers), or SAE (Society of Automotive Engineers).

- Governmental Reports- the research conducted in these reports has been sponsored by the United States or an international government body as well as state and local governments.

Some technical reports are cataloged as books, which you can search for in the catalog, while others may be located in databases, or free online. The boxes below list databases and online resources you can use to locate a report.

If you’re not sure where to start, try to learn more about the report by confirming the full title or learning more about the publication information.

Confirm the title and locate the report number in NTRL.

Search Google Scholar, the HathiTrust, or WorldCat. This can verify the accuracy of the citation and determine if the technical report was also published in a journal or conference proceeding or under a different report number.

Having trouble finding a report through Penn State? If we don’t have access to the report, you can submit an interlibrary loan request and we will get it for you from another library. If you have any questions, you can always contact a librarian!

- National Technical Reports Library (NTRL) NTRL is the preeminent resource for accessing the latest US government sponsored research, and worldwide scientific, technical, and engineering information. Search by title to determine report number.

- Engineering Village Engineering Village is the most comprehensive interdisciplinary engineering database in the world with over 5,000 engineering journals and conference materials dating from 1884. Has citations to many ASME, ASCE, SAE, and other professional organizations' technical papers. Search by author, title, or report number.

- IEEE Xplore Provides access to articles, papers, reports, and standards from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE).

- ASABE Technical Library Provides access to all of the recent technical documents published by the American Society of Agricultural Engineers.

- International Nuclear Information System (INIS) Database Provides access to nuclear science and technology technical reports.

- NASA Technical Reports Server Contains the searchable NACA Technical Reports collection, NASA Technical Reports collection and NIX collection of images, movies, and videos. Includes the full text and bibliographic records of selected unclassified, publicly available NASA-sponsored technical reports. Coverage: NACA reports 1915-1958, NASA reports since 1958.

- OSTI Technical Reports Full-text of Department of Energy (DOE) funded science, technology, and engineering technical reports. OSTI has replaced SciTech Connect as the primary search tool for Department of Energy (DOE) funded science, technology, and engineering research results. It provides access to all the information previously available in SciTech Connect, DOE Information Bridge, and Energy Citations Database.

- ERIC (ProQuest) Provides access to technical reports and other education-related materials. ERIC is sponsored by the U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences (IES).

- Transportation Research International Documentation (TRID) TRID is a newly integrated database that combines the records from TRB's Transportation Research Information Services (TRIS) Database and the OECD's Joint Transport Research Centre's International Transport Research Documentation (ITRD) Database. TRID provides access to over 900,000 records of transportation research worldwide.

- TRAIL Technical Reports Archive & Image Library Provide access to federal technical reports issued prior to 1975.

- Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC) The largest central resource for Department of Defense and government-funded scientific, technical, engineering, and business related information.

- Correlation Index of Technical Reports (AD-PB Reports) Publication Date: 1958

- Criss-cross directory of NASA "N" numbers and DOD "AD" numbers, 1962-1986

Print indexes to technical reports :

- Government Reports Announcements & Index (1971-1996)

- Government Reports Announcements (1946-1975)

- U.S. Government Research & Development Reports (1965-1971)

- U.S. Government Research Reports (1954-1964)

- Bibliography of Technical Reports (1949-1954)

- Bibliography of Scientific and Industrial Reports (1946-1949)

- Next: Direct Links to Organizations with Technical Reports >>

- Last Updated: Oct 5, 2023 2:56 PM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.psu.edu/techreports

Technical Report: What is it & How to Write it? (Steps & Structure Included)

A technical report can either act as a cherry on top of your project or can ruin the entire dough.

Everything depends on how you write and present it.

A technical report is a sole medium through which the audience and readers of your project can understand the entire process of your research or experimentation.

So, you basically have to write a report on how you managed to do that research, steps you followed, events that occurred, etc., taking the reader from the ideation of the process and then to the conclusion or findings.

Sounds exhausting, doesn’t it?

Well hopefully after reading this entire article, it won’t.

However, note that there is no specific standard determined to write a technical report. It depends on the type of project and the preference of your project supervisor.

With that in mind, let’s dig right in!

What is a Technical Report? (Definition)

A technical report is described as a written scientific document that conveys information about technical research in an objective and fact-based manner. This technical report consists of the three key features of a research i.e process, progress, and results associated with it.

Some common areas in which technical reports are used are agriculture, engineering, physical, and biomedical science. So, such complicated information must be conveyed by a report that is easily readable and efficient.

Now, how do we decide on the readability level?

The answer is simple – by knowing our target audience.

A technical report is considered as a product that comes with your research, like a guide for it.

You study the target audience of a product before creating it, right?

Similarly, before writing a technical report, you must keep in mind who your reader is going to be.

Whether it is professors, industry professionals, or even customers looking to buy your project – studying the target audience enables you to start structuring your report. It gives you an idea of the existing knowledge level of the reader and how much information you need to put in the report.

Many people tend to put in fewer efforts in the report than what they did in the actual research..which is only fair.

We mean, you’ve already worked so much, why should you go through the entire process again to create a report?

Well then, let’s move to the second section where we talk about why it is absolutely essential to write a technical report accompanying your project.

Read more: What is a Progress Report and How to Write One?

Importance of Writing a Technical Report

1. efficient communication.

Technical reports are used by industries to convey pertinent information to upper management. This information is then used to make crucial decisions that would impact the company in the future.

Examples of such technical reports include proposals, regulations, manuals, procedures, requests, progress reports, emails, and memos.

2. Evidence for your work

Most of the technical work is backed by software.

However, graduation projects are not.

So, if you’re a student, your technical report acts as the sole evidence of your work. It shows the steps you took for the research and glorifies your efforts for a better evaluation.

3. Organizes the data

A technical report is a concise, factual piece of information that is aligned and designed in a standard manner. It is the one place where all the data of a project is written in a compact manner that is easily understandable by a reader.

4. Tool for evaluation of your work

Professors and supervisors mainly evaluate your research project based on the technical write-up for it. If your report is accurate, clear, and comprehensible, you will surely bag a good grade.

A technical report to research is like Robin to Batman.

Best results occur when both of them work together.

So, how can you write a technical report that leaves the readers in a ‘wow’ mode? Let’s find out!

How to Write a Technical Report?

When writing a technical report, there are two approaches you can follow, depending on what suits you the best.

- Top-down approach- In this, you structure the entire report from title to sub-sections and conclusion and then start putting in the matter in the respective chapters. This allows your thought process to have a defined flow and thus helps in time management as well.

- Evolutionary delivery- This approach is suitable if you’re someone who believes in ‘go with the flow’. Here the author writes and decides as and when the work progresses. This gives you a broad thinking horizon. You can even add and edit certain parts when some new idea or inspiration strikes.

A technical report must have a defined structure that is easy to navigate and clearly portrays the objective of the report. Here is a list of pages, set in the order that you should include in your technical report.

Cover page- It is the face of your project. So, it must contain details like title, name of the author, name of the institution with its logo. It should be a simple yet eye-catching page.

Title page- In addition to all the information on the cover page, the title page also informs the reader about the status of the project. For instance, technical report part 1, final report, etc. The name of the mentor or supervisor is also mentioned on this page.

Abstract- Also referred to as the executive summary, this page gives a concise and clear overview of the project. It is written in such a manner that a person only reading the abstract can gain complete information on the project.

Preface – It is an announcement page wherein you specify that you have given due credits to all the sources and that no part of your research is plagiarised. The findings are of your own experimentation and research.

Dedication- This is an optional page when an author wants to dedicate their study to a loved one. It is a small sentence in the middle of a new page. It is mostly used in theses.

Acknowledgment- Here, you acknowledge the people parties, and institutions who helped you in the process or inspired you for the idea of it.

Table of contents – Each chapter and its subchapter is carefully divided into this section for easy navigation in the project. If you have included symbols, then a similar nomenclature page is also made. Similarly, if you’ve used a lot of graphs and tables, you need to create a separate content page for that. Each of these lists begins on a new page.

Introduction- Finally comes the introduction, marking the beginning of your project. On this page, you must clearly specify the context of the report. It includes specifying the purpose, objectives of the project, the questions you have answered in your report, and sometimes an overview of the report is also provided. Note that your conclusion should answer the objective questions.

Central Chapter(s)- Each chapter should be clearly defined with sub and sub-sub sections if needed. Every section should serve a purpose. While writing the central chapter, keep in mind the following factors:

- Clearly define the purpose of each chapter in its introduction.

- Any assumptions you are taking for this study should be mentioned. For instance, if your report is targeting globally or a specific country. There can be many assumptions in a report. Your work can be disregarded if it is not mentioned every time you talk about the topic.

- Results you portray must be verifiable and not based upon your opinion. (Big no to opinions!)

- Each conclusion drawn must be connected to some central chapter.

Conclusion- The purpose of the conclusion is to basically conclude any and everything that you talked about in your project. Mention the findings of each chapter, objectives reached, and the extent to which the given objectives were reached. Discuss the implications of the findings and the significant contribution your research made.

Appendices- They are used for complete sets of data, long mathematical formulas, tables, and figures. Items in the appendices should be mentioned in the order they were used in the project.

References- This is a very crucial part of your report. It cites the sources from which the information has been taken from. This may be figures, statistics, graphs, or word-to-word sentences. The absence of this section can pose a legal threat for you. While writing references, give due credit to the sources and show your support to other people who have studied the same genres.

Bibliography- Many people tend to get confused between references and bibliography. Let us clear it out for you. References are the actual material you take into your research, previously published by someone else. Whereas a bibliography is an account of all the data you read, got inspired from, or gained knowledge from, which is not necessarily a direct part of your research.

Style ( Pointers to remember )

Let’s take a look at the writing style you should follow while writing a technical report:

- Avoid using slang or informal words. For instance, use ‘cannot’ instead of can’t.

- Use a third-person tone and avoid using words like I, Me.

- Each sentence should be grammatically complete with an object and subject.

- Two sentences should not be linked via a comma.

- Avoid the use of passive voice.

- Tenses should be carefully employed. Use present for something that is still viable and past for something no longer applicable.

- Readers should be kept in mind while writing. Avoid giving them instructions. Your work is to make their work of evaluation easier.

- Abbreviations should be avoided and if used, the full form should be mentioned.

- Understand the difference between a numbered and bulleted list. Numbering is used when something is explained sequence-wise. Whereas bullets are used to just list out points in which sequence is not important.

- All the preliminary pages (title, abstract, preface..) should be named in small roman numerals. ( i, ii, iv..)

- All the other pages should be named in Arabic numerals (1,2,3..) thus, your report begins with 1 – on the introduction page.

- Separate long texts into small paragraphs to keep the reader engaged. A paragraph should not be more than 10 lines.

- Do not incorporate too many fonts. Use standard times new roman 12pt for the text. You can use bold for headlines.

Proofreading

If you think your work ends when the report ends, think again. Proofreading the report is a very important step. While proofreading you see your work from a reader’s point of view and you can correct any small mistakes you might have done while typing. Check everything from content to layout, and style of writing.

Presentation

Finally comes the presentation of the report in which you submit it to an evaluator.

- It should be printed single-sided on an A4 size paper. double side printing looks chaotic and messy.

- Margins should be equal throughout the report.

- You can use single staples on the left side for binding or use binders if the report is long.

AND VOILA! You’re done.

…and don’t worry, if the above process seems like too much for you, Bit.ai is here to help.

Read more: Technical Manual: What, Types & How to Create One? (Steps Included)

Bit.ai : The Ultimate Tool for Writing Technical Reports

What if we tell you that the entire structure of a technical report explained in this article is already done and designed for you!

Yes, you read that right.

With Bit.ai’s 70+ templates , all you have to do is insert your text in a pre-formatted document that has been designed to appeal to the creative nerve of the reader.

You can even add collaborators who can proofread or edit your work in real-time. You can also highlight text, @mention collaborators, and make comments!

Wait, there’s more! When you send your document to the evaluators, you can even trace who read it, how much time they spent on it, and more.

Exciting, isn’t it?

Start making your fabulous technical report with Bit.ai today!

Few technical documents templates you might be interested in:

- Status Report Template

- API Documentation

- Product Requirements Document Template

- Software Design Document Template

- Software Requirements Document Template

- UX Research Template

- Issue Tracker Template

- Release Notes Template

- Statement of Work

- Scope of Work Template

Wrap up(Conclusion)

A well structured and designed report adds credibility to your research work. You can rely on bit.ai for that part.

However, the content is still yours so remember to make it worth it.

After finishing up your report, ask yourself:

Does the abstract summarize the objectives and methods employed in the paper?

Are the objective questions answered in your conclusion?

What are the implications of the findings and how is your work making a change in the way that particular topic is read and conceived?

If you find logical answers to these, then you have done a good job!

Remember, writing isn’t an overnight process. ideas won’t just arrive. Give yourself space and time for inspiration to strike and then write it down. Good writing has no shortcuts, it takes practice.

But at least now that you’ve bit.ai in the back of your pocket, you don’t have to worry about the design and formatting!

Have you written any technical reports before? If yes, what tools did you use? Do let us know by tweeting us @bit_docs.

Further reads:

How To Create An Effective Status Report?

7 Types of Reports Your Business Certainly Needs!

What is Project Status Report Documentation?

Scientific Paper: What is it & How to Write it? (Steps and Format)

Business Report: What is it & How to Write it? (Steps & Format)

How to Write Project Reports that ‘Wow’ Your Clients? (Template Included)

Business Report: What is it & How to Write it? (Steps & Format)

Internship Cover Letter: How to Write a Perfect one?

Related posts

User guide: how to write an effective one (tips, examples & more), what is project planning: a step by step guide, workflow automation & everything you need to know, client portals: communicate with clients the right way, how to create partnership marketing plan (template included), top 12 ai assistants of 2024 for maximized potential.

About Bit.ai

Bit.ai is the essential next-gen workplace and document collaboration platform. that helps teams share knowledge by connecting any type of digital content. With this intuitive, cloud-based solution, anyone can work visually and collaborate in real-time while creating internal notes, team projects, knowledge bases, client-facing content, and more.

The smartest online Google Docs and Word alternative, Bit.ai is used in over 100 countries by professionals everywhere, from IT teams creating internal documentation and knowledge bases, to sales and marketing teams sharing client materials and client portals.

👉👉Click Here to Check out Bit.ai.

Recent Posts

9 knowledge base mistakes: what you need to know to avoid them, personal user manual: enhance professional profile & team productivity, 9 document management trends every business should know, ai for social media marketing: tools & tactics to boost engagement, a guide to building a client portal for your online course, knowledge management vs document management.

Guide to Technical Reports: What it is and How to Write it

Introduction.

You want to improve the customers’ experience with your products, but your team is too busy creating and/or updating products to write a report.

Getting them ready for the task is another problem you need to overcome.

Who wants to write a technical report on the exact process you just conducted?

Exactly, no one.

Honestly, we get it: you’re supposed to be managing coding geniuses — not writers.

But it's one of those things you need to get it done for sound decision-making and ensuring communication transparency. In many organizations, engineers spend nearly 40 percent of their time writing technical reports.

If you're wondering how to write good technical reports that convey your development process and results in the shortest time possible, we've got you covered.

Let’s start with the basics.

What is a technical report?

A technical report is a piece of documentation developed by technical writers and/or the software team outlining the process of:

- The research conducted.

- How it advances.

- The results obtained.

In layman's terms, a technical report is created to accompany a product, like a manual. Along with the research conducted, a technical report also summarizes the conclusion and recommendations of the research.

The idea behind building technical documentation is to create a single source of truth about the product and including any product-related information that may be insightful down the line.

Industries like engineering, IT, medicine and marketing use technical documentation to explain the process of how a product was created.

Ideally, you should start documenting the process when a product is in development, or already in use. A good technical report has the following elements:

- Functionality.

- Development.

Gone are the days when technical reports used to be boring yawn-inducing dry text. Today, you can make them interactive and engaging using screenshots, charts, diagrams, tables, and similar visual assets.

💡 Related resource: 5 Software Documentation Challenges & How To Overcome Them

Who is responsible for creating reports?

Anyone with a clear knowledge of the industry and the product can write a technical report by following simple writing rules.

It's possible your developers will be too busy developing the product to demonstrate the product development process.

Keeping this in mind, you can have them cover the main points and send off the writing part to the writing team. Hiring a technical writer can also be beneficial, who can collaborate with the development and operations team to create the report.

Why is technical documentation crucial for a business?

If you’re wondering about the benefits of writing a report, here are three reasons to convince you why creating and maintaining technical documentation is a worthy cause.

1. Easy communication of the process

Technical reports give you a more transparent way to communicate the process behind the software development to the upper management or the stakeholders.

You can also show the technical report to your readers interested in understanding the behind the scenes (BTS) action of product development. Treat this as a chance to show value and the methodology behind the same.

🎓 The Ultimate Product Development Checklist

2. Demonstrating the problem & solution

You can use technical documentation tools to create and share assets that make your target audience aware of the problem.

Technical reports can shed more light on the problem they’re facing while simultaneously positioning your product as the best solution for it.

3. Influence upper management decisions

Technical reports are also handy for conveying the product's value and functionality to the stakeholders and the upper management, opening up the communication channel between them and other employees.

You can also use this way to throw light on complex technical nuances and help them understand the jargon better.

Benefits of creating technical reports

The following are some of the biggest benefits of technical documentation:

- Cuts down customer support tickets, enabling users to easily use the product without technical complications.

- Lets you share detailed knowledge of the product's usability and potential, showing every aspect to the user as clearly as possible.

- Enables customer success teams to answer user questions promptly and effectively.

- Creates a clear roadmap for future products.

- Improves efficiency for other employees in the form of technical training.

The 5 types of technical reports

There are not just one but five types of technical reports you can create. These include:

1. Feasibility report

This report is prepared during the initial stages of software development to determine whether the proposed project will be successful.

2. Business report

This report outlines the vision, objectives and goals of the business while laying down the steps needed to crush those goals.

3. Technical specification report

This report specifies the essentials for a product or project and details related to the development and design.

4. Research report

This report includes information on the methodology and outcomes based on any experimentation.

5. Recommendation report

This report contains all the recommendations the DevOps team can use to solve potential technical problems.

The type of technical report you choose depends on certain factors like your goals, the complexity of the product and its requirements.

What are the key elements of a technical report?

Following technical documentation best practices , you want the presented information to be clear and well-organized. Here are the elements (or sections) a typical technical report should have:

This part is simple and usually contains the names of the authors, your company name, logo and so on.

Synopses are usually a couple of paragraphs long, but it sets the scene for the readers. It outlines the problem to be solved, the methods used, purpose and concept of the report.

You can’t just write the title of the project here, and call it a day. This page should also include information about the author, their company position and submission date, among other things. The name and position of the supervisor or mentor is also mentioned here.

The abstract is a brief summary of the project addressed to the readers. It gives a clear overview of the project and helps readers decide whether they want to read the report.

The foreword is a page dedicated to acknowledging all the sources used to write this report. It gives assurance that no part of the report is plagiarized and all the necessary sources have been cited and given credit to.

Acknowledgment

This page is used for acknowledging people and institutions who helped in completing the report.

Table of Contents

Adding a table of contents makes navigating from one section to another easier for readers. It acts as a compass for the structure of the report.

List of illustrations

This part contains all the graphs, diagrams, images, charts and tables used across the report. Ideally, it should have all the materials supporting the content presented in the report.

The introduction is a very crucial part of the project that should specify the context of the project, along with its purpose and objective. Things like background information, scope of work and limitations are discussed under this section.

The body of the report is generally divided into sections and subsections that clearly define the purpose of each area, ideas, purpose and central scope of work.

Conclusion

The conclusion should have an answer to all the questions and arguments made in the introduction or body of the report. It should answer the objectives of the findings, the results achieved and any further observations made.

This part lists the mathematical formulas and data used in the content, following the same order as they were used in the report.

The page cites the sources from which information was taken. Any quotes, graphs and statistics used in your report need to be credited to the original source.

A glossary is the index of all the terms and symbols used in the report.

Bibliography

The bibliography outlines the names of all the books and data you researched to gain knowledge on the subject matter.

How to create your own technical report in 6 simple steps

To create a high-quality technical report, you need to follow these 5 steps.

Step 1: Research

If you’ve taken part in the product development process, this part comes easily. But if you’ve not participated in the development (or are hiring a writer), you need to learn as much about the product as possible to understand it in and out.

While doing your research, you need to think from your target users' perspectives.

- You have to know if they’re tech-savvy or not. Whether they understand industry technicalities and jargon or not?

- What goals do you want to achieve with the report? What do you want the final outcome to look like for your users?

- What do you want to convey using the report and why?

- What problems are you solving with the report, and how are you solving them?

This will help you better understand the audience you’re writing for and create a truly valuable document.

Step 2: Design

You need to make it simple for users to consume and navigate through the report.

The structure is a crucial element to help your users get familiar with your product and skim through sections. Some points to keep in mind are:

- Outlining : Create an outline of the technical report before you start writing. This will ensure that the DevOps team and the writer are on the same page.

- Table of contents : Make it easy for your users to skip to any part of the report they want without scrolling through the entire document.

- Easy to read and understand : Make the report easy to read and define all technical terms, if your users aren’t aware of them. Explain everything in detail, adding as many practical examples and case studies as possible.

- Interactive : Add images, screenshots, or any other visual aids to make the content interactive and engaging.

- Overview : Including a summary of what's going to be discussed in the next sections adds a great touch to the report.

- FAQ section : An underrated part of creating a report is adding a FAQ section at the end that addresses users' objections or queries regarding the product.

Step 3: Write

Writing content is vital, as it forms the body of the report. Ensure the content quality is strong by using the following tips:

- Create a writing plan.

- Ensure the sentence structure and wording is clear.

- Don’t repeat information.

- Explain each and every concept precisely.

- Maintain consistency in the language used throughout the document

- Understand user requirements and problems, and solve them with your content.

- Avoid using passive voice and informal words.

- Keep an eye out for grammatical errors.

- Make the presentation of the report clean.

- Regularly update the report over time.

- Avoid using abbreviations.

Regardless of whether you hire a writer or write the report yourself, these best practices will help you create a great technical report that provides value to the reader.

Step 4: Format

The next step of writing technical reports is formatting.

You can either use the company style guide provided to you or follow the general rules of report formatting. Here is a quick rundown:

1. Page Numbering (excluding cover page, and back covers).

2. Headers.

- Make it self-explanatory.

- Must be parallel in phrasing.

- Avoid “lone headings.”

- Avoid pronouns .

3. Documentation.

- Cite borrowed information.

- Use in-text citations or a separate page for the same.

Step 5: Proofread

Don’t finalize the report for publishing before proofreading the entire documentation.

Our best proofreading advice is to read it aloud after a day or two. If you find any unexplained parts or grammatical mistakes, you can easily fix them and make the necessary changes. You can also consider getting another set of eyes to spot the mistakes you may have missed.

Step 6: Publish

Once your technical report is ready, get it cross-checked by an evaluator. After you get their approval, publish on your website as a gated asset — or print it out as an A4 version for presentation.

Extra Step: Refreshing

Okay, we added an extra step, but hear us out: your job is not finished after hitting publish.

Frequent product updates mean you should also refresh the report every now and then to reflect these changes. A good rule of thumb is to refresh any technical documentation every eight to twelve months and update it with the latest information.

Not only will this eliminate confusion but also ensure your readers get the most value out of the document.

Making successful technical reports with Scribe

How about developing technical reports faster and without the hassle?

With Scribe and Scribe’s newest feature, Pages , you can do just that.

Scribe is a leading process documentation tool that does the documenting for you, pat down to capturing and annotating screenshots. Here's one in action.

Pages lets you compile all your guides, instructions and SOPs in a single document, giving you an elaborate and digital technical report you can share with both customers and stakeholders.

{{banner-default="/banner-ads"}}

Here is a Page showing you how to use Scribe Pages .

Examples of good technical reports

You can use these real-life examples of good technical reports for inspiration and guidance!

- Mediums API Documentation

- Twilio Docs

- The AWS PRD for Container-based Products

Signing off…

Now you know how to write technical documentation , what's next?

Writing your first technical report! Remember, it’s not rocket science. Simply follow the technical writing best practices and the format we shared and you'll be good to go.

Ready to try Scribe?

Related content

- Scribe Gallery

- Help Center

- What's New

- Careers We're Hiring!

- Contact Sales

Technical Reports

Sources for identifying technical reports, what are technical reports, types of reports.

- Government-Based Indexes & Databases

- Subject-Oriented Subscription Databases

For More Help

Chat, email, or schedule a consultation with a subject librarian!

Ask A Librarian

Social Sciences, Public Policy & Government Information Librarian

There are multiple approaches for identifying technical reports, depending on topic; some of these also contain full text for technical reports:

- Technical report indexes and databases (many of these are government-related)

- Some subject-oriented databases index technical reports and other materials in addition to peer-reviewed journal articles.

- Library search box or library catalog for holdings at the UNH Library

- WorldCat for holdings at other libraries (First Search or Books & Media Worldwide)

- References cited in articles

A technical report is a document written by a researcher detailing the results of a project and submitted to the sponsor of that project. Many technical reports are government sponsored with the Department of Energy, NASA, and the Department of Defense among the top sponsors. A number of U.S. Government sponsors now make technical reports available full image via the internet. Some technical reports may be available in paper or on microfiche in the UNH Library.

Although technical reports are very heterogeneous, they tend to possess the following characteristics:

- technical reports may be published before the corresponding journal literature

- content may be more detailed than the corresponding journal literature, although there may be less background information since the sponsor already knows it

- technical reports are usually not peer reviewed unless the report is separately published as journal literature

- classified and export-controlled reports have restricted access

- obscure acronyms and codes are frequently used

Above text (with minor revisions) is used by permission and is from Georgia Tech Library's Technical Reports guide.

- Types of Technical Reports Committee on Scientific and Technical Information (COSATI) definitions for technical reports (source: Rutgers University Libraries Technical Reports guide)

- Next: Government-Based Indexes & Databases >>

- Last Updated: May 15, 2024 10:19 AM

- URL: https://libraryguides.unh.edu/technical-reports

Cookies on our website

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We'd like to set additional cookies to understand how you use our site. And we'd like to serve you some cookies set by other services to show you relevant content.

- Accessibility

- Staff search

- External website

- Schools & services

- Sussex Direct

- Professional services

- Schools and services

- Engineering and Informatics

- Student handbook

- Engineering and Design

- Study guides

Guide to Technical Report Writing

- Back to previous menu

- Guide to Laboratory Writing

School of Engineering and Informatics (for staff and students)

Table of contents

1 Introduction

2 structure, 3 presentation, 4 planning the report, 5 writing the first draft, 6 revising the first draft, 7 diagrams, graphs, tables and mathematics, 8 the report layout, 10 references to diagrams, graphs, tables and equations, 11 originality and plagiarism, 12 finalising the report and proofreading, 13 the summary, 14 proofreading, 15 word processing / desktop publishing, 16 recommended reading.

A technical report is a formal report designed to convey technical information in a clear and easily accessible format. It is divided into sections which allow different readers to access different levels of information. This guide explains the commonly accepted format for a technical report; explains the purposes of the individual sections; and gives hints on how to go about drafting and refining a report in order to produce an accurate, professional document.

A technical report should contain the following sections;

For technical reports required as part of an assessment, the following presentation guidelines are recommended;

There are some excellent textbooks contain advice about the writing process and how to begin (see Section 16 ). Here is a checklist of the main stages;

- Collect your information. Sources include laboratory handouts and lecture notes, the University Library, the reference books and journals in the Department office. Keep an accurate record of all the published references which you intend to use in your report, by noting down the following information; Journal article: author(s) title of article name of journal (italic or underlined) year of publication volume number (bold) issue number, if provided (in brackets) page numbers Book: author(s) title of book (italic or underlined) edition, if appropriate publisher year of publication N.B. the listing of recommended textbooks in section 2 contains all this information in the correct format.

- Creative phase of planning. Write down topics and ideas from your researched material in random order. Next arrange them into logical groups. Keep note of topics that do not fit into groups in case they come in useful later. Put the groups into a logical sequence which covers the topic of your report.

- Structuring the report. Using your logical sequence of grouped ideas, write out a rough outline of the report with headings and subheadings.

N.B. the listing of recommended textbooks in Section 16 contains all this information in the correct format.

Who is going to read the report? For coursework assignments, the readers might be fellow students and/or faculty markers. In professional contexts, the readers might be managers, clients, project team members. The answer will affect the content and technical level, and is a major consideration in the level of detail required in the introduction.

Begin writing with the main text, not the introduction. Follow your outline in terms of headings and subheadings. Let the ideas flow; do not worry at this stage about style, spelling or word processing. If you get stuck, go back to your outline plan and make more detailed preparatory notes to get the writing flowing again.

Make rough sketches of diagrams or graphs. Keep a numbered list of references as they are included in your writing and put any quoted material inside quotation marks (see Section 11 ).

Write the Conclusion next, followed by the Introduction. Do not write the Summary at this stage.

This is the stage at which your report will start to take shape as a professional, technical document. In revising what you have drafted you must bear in mind the following, important principle;

- the essence of a successful technical report lies in how accurately and concisely it conveys the intended information to the intended readership.

During year 1, term 1 you will be learning how to write formal English for technical communication. This includes examples of the most common pitfalls in the use of English and how to avoid them. Use what you learn and the recommended books to guide you. Most importantly, when you read through what you have written, you must ask yourself these questions;

- Does that sentence/paragraph/section say what I want and mean it to say? If not, write it in a different way.

- Are there any words/sentences/paragraphs which could be removed without affecting the information which I am trying to convey? If so, remove them.

It is often the case that technical information is most concisely and clearly conveyed by means other than words. Imagine how you would describe an electrical circuit layout using words rather than a circuit diagram. Here are some simple guidelines;

The appearance of a report is no less important than its content. An attractive, clearly organised report stands a better chance of being read. Use a standard, 12pt, font, such as Times New Roman, for the main text. Use different font sizes, bold, italic and underline where appropriate but not to excess. Too many changes of type style can look very fussy.

Use heading and sub-headings to break up the text and to guide the reader. They should be based on the logical sequence which you identified at the planning stage but with enough sub-headings to break up the material into manageable chunks. The use of numbering and type size and style can clarify the structure as follows;

- In the main text you must always refer to any diagram, graph or table which you use.

- Label diagrams and graphs as follows; Figure 1.2 Graph of energy output as a function of wave height. In this example, the second diagram in section 1 would be referred to by "...see figure 1.2..."

- Label tables in a similar fashion; Table 3.1 Performance specifications of a range of commercially available GaAsFET devices In this example, the first table in section 3 might be referred to by "...with reference to the performance specifications provided in Table 3.1..."

- Number equations as follows; F(dB) = 10*log 10 (F) (3.6) In this example, the sixth equation in section 3 might be referred to by "...noise figure in decibels as given by eqn (3.6)..."

Whenever you make use of other people's facts or ideas, you must indicate this in the text with a number which refers to an item in the list of references. Any phrases, sentences or paragraphs which are copied unaltered must be enclosed in quotation marks and referenced by a number. Material which is not reproduced unaltered should not be in quotation marks but must still be referenced. It is not sufficient to list the sources of information at the end of the report; you must indicate the sources of information individually within the report using the reference numbering system.

Information that is not referenced is assumed to be either common knowledge or your own work or ideas; if it is not, then it is assumed to be plagiarised i.e. you have knowingly copied someone else's words, facts or ideas without reference, passing them off as your own. This is a serious offence . If the person copied from is a fellow student, then this offence is known as collusion and is equally serious. Examination boards can, and do, impose penalties for these offences ranging from loss of marks to disqualification from the award of a degree

This warning applies equally to information obtained from the Internet. It is very easy for markers to identify words and images that have been copied directly from web sites. If you do this without acknowledging the source of your information and putting the words in quotation marks then your report will be sent to the Investigating Officer and you may be called before a disciplinary panel.

Your report should now be nearly complete with an introduction, main text in sections, conclusions, properly formatted references and bibliography and any appendices. Now you must add the page numbers, contents and title pages and write the summary.

The summary, with the title, should indicate the scope of the report and give the main results and conclusions. It must be intelligible without the rest of the report. Many people may read, and refer to, a report summary but only a few may read the full report, as often happens in a professional organisation.

- Purpose - a short version of the report and a guide to the report.

- Length - short, typically not more than 100-300 words

- Content - provide information, not just a description of the report.

This refers to the checking of every aspect of a piece of written work from the content to the layout and is an absolutely necessary part of the writing process. You should acquire the habit of never sending or submitting any piece of written work, from email to course work, without at least one and preferably several processes of proofreading. In addition, it is not possible for you, as the author of a long piece of writing, to proofread accurately yourself; you are too familiar with what you have written and will not spot all the mistakes.

When you have finished your report, and before you staple it, you must check it very carefully yourself. You should then give it to someone else, e.g. one of your fellow students, to read carefully and check for any errors in content, style, structure and layout. You should record the name of this person in your acknowledgements.

Two useful tips;

- Do not bother with style and formatting of a document until the penultimate or final draft.

- Do not try to get graphics finalised until the text content is complete.

- Davies J.W. Communication Skills - A Guide for Engineering and Applied Science Students (2nd ed., Prentice Hall, 2001)

- van Emden J. Effective communication for Science and Technology (Palgrave 2001)

- van Emden J. A Handbook of Writing for Engineers 2nd ed. (Macmillan 1998)

- van Emden J. and Easteal J. Technical Writing and Speaking, an Introduction (McGraw-Hill 1996)

- Pfeiffer W.S. Pocket Guide to Technical Writing (Prentice Hall 1998)

- Eisenberg A. Effective Technical Communication (McGraw-Hill 1992)

Updated and revised by the Department of Engineering & Design, November 2022

School Office: School of Engineering and Informatics, University of Sussex, Chichester 1 Room 002, Falmer, Brighton, BN1 9QJ [email protected] T 01273 (67) 8195 School Office opening hours: School Office open Monday – Friday 09:00-15:00, phone lines open Monday-Friday 09:00-17:00 School Office location [PDF 1.74MB]

Copyright © 2024, University of Sussex

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 The Formal Technical Report

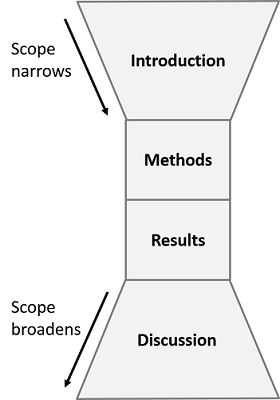

For technical reports, formal and informal, readers are generally most interested in process and results. Clear presentation of results is at least as important as the results themselves; therefore, writing a report is an exercise in effective communication of technical information. Results, such as numerical values, designed systems or graphs by themselves are not very useful. To be meaningful to others, results must be supported by a written explanation describing how results were obtained and what significance they hold, or how a designed system actually functions. Although the person reading the report may have a technical background, the author should assume unfamiliarity with related theory and procedures. The author must consider supplying details that may appear obvious or unnecessary. With practice, the technical report writer learns which details to include.

The formal technical report contains a complete, concise, and well-organized description of the work performed and the results obtained. Any given report may contain all of the sections described in these guidelines or a subset, depending upon the report requirements. These requirements are decided by the author and are based on the audience and expected use of the report. Audience and purpose are important considerations in deciding which sections to include and what content to provide. If the purpose is to chronicle work performed in lab, as is typical for an academic lab report, the audience is typically the professor who assigned the work and the contents usually include detailed lab procedure, clear presentation of results, and conclusions based on the evidence provided. For a technical report, the audience may be colleagues, customers, or decision makers. Knowing the audience and what they are expecting to get out of reading the report is of primary consideration when deciding on sections to include and their contents.

There are certain aspects to all reports that are common regardless of audience and expected usage. Rather than relegate these overarching report-writing considerations to a secondary position, these items are presented before detailing the typical organization and contents for technical reports.

Universal Report-Writing Considerations

The items listed in this section are often overlooked by those new to technical report writing. However, these items set the stage for how a technical report is received which can impact the author, positively or negatively. While in an academic setting, the author’s grade could be impacted. While in a professional setting, it is the author’s career that could be affected. Effective communication can make the difference in career advancement, effective influence on enacting positive change, and propelling ideas from thought to action. The list that follows should become second nature to the technical report writer.

Details to consider that affect credibility:

- Any information in the report that is directly derived or paraphrased from a source must be cited using the proper notation.

- Any information in the report that is directly quoted or copied from a source must be cited using the proper notation.

- Any reference material derived from the web or Internet must come from documentable and credible sources. To evaluate websites critically, begin by verifying the credibility of the author (e.g. – credentials, agency or professional affiliation). Note that peer reviewed materials are generally more dependable sources of information as compared to open source. Peer review involves a community of qualified experts from within a profession who validate the publication of the author. Open source information may be created by non-qualified individuals or agencies which is often not reviewed and/or validated by experts within the field or profession.

- Wikipedia is NOT a credible reference because the information changes over time and authors are not necessarily people with verifiable expertise or credentials.

- Provide an annotated bibliography of all references. Typically, annotations in technical reports indicate what the source was used for and establish the credibility of the source. This is particularly important for sources with credibility issues. However, an annotation can clarify why a source with questionable credibility was used.

- With the increasing availability of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) such as provided by ChatGPT, where GPT stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer, credibility will likely be challenged more frequently and will be more difficult to establish. Generative AI models may provide invalid responses and a knowledgeable reader will pick up on that quickly.

- Make sure to know the consequences if you violate rules provided by your instructor in an academic setting or by your employer in a workplace setting for presenting work by another or by AI as if it were your own (without citation). Additionally, there may be rules on how much of your work can be AI-generated and what annotation you are required to provide when using generative AI. Know the rules and if you can’t find the rules, ASK.

- See Appendix A for information about citing sources and AI-generated content.

Details to consider that affect the professional tone:

- Passive voice: “The circuit resistance will be measured with a digital multimeter”.

- Active voice: “Measure the circuit resistance with a digital multimeter”.

- Avoid using personal pronouns such as “you”, “we”, “our”, “they”, “us” and “I”. Personal pronouns tend to personalize the technical information that is generally objective rather than subjective in nature. The exception is if the work as a whole is meant to instruct than to inform. For example, technical textbooks whose only purpose is to instruct employ personal pronouns.

- Avoid using “it”. When “it” is used, the writing often leads to a lack of clarity for the reader as to what idea/concept “it” is referring to, thus negatively impacting overall clarity of the writing.

- Use correct grammar, punctuation, and spelling. Pay attention to and address spell and grammar check cues from writing software such as Microsoft (MS) Word.

Details to consider that affect the professional appearance:

- All figures and tables must be neatly presented and should be computer generated. Use a computer software package, such as Paint, Multisim, AutoCAD, or SolidWorks, to draw figures. If inserting a full-page figure, insert it so can be read from the bottom or from the right side of the page . ALL figures and tables must fit within or very close to the page margins.

- Generate ALL equations using an equation editor and provide each equation on its own line. Under normal circumstances, there is no reason to embed an equation within a paragraph. Depending on presentation and how many equations are involved, number the equations for easy reference.

- Refer to appendix B for information on how to automatically create a Table of Contents and properly number pages.

- If the report includes an abstract, it should be on an unnumbered page after the title page and before the Table of Contents or it can be included on the title page.

- For all hard copy reports, all pages of the report must be 8 ½“ X 11” in size. Any larger pages must be folded so as to fit these dimensions. HOWEVER, in this day and age, an electronic submission is most common. Keep in mind that with an electronic submission, it is easier to provide an appealing look with color since a color printer is not required.

Details to consider that affect readability:

- Every section and sub-section of the report needs to start with an introductory paragraph that provides the context for the section or sub-section.

- Every figure, graph, table, and equation needs to be introduced to the reader prior to being presented to the reader. This introduction provides the context.

- ALWAYS NUMBER AND PROVIDE A TITLE FOR ALL FIGURES .

- Make sure that the verb used can actually operate on the noun. For example, stating “the goal for this report is to observe …” implies that the report can observe when it is likely that the goal of the work reported on is to make certain observations.

- Check for spelling and grammar errors which are often highlighted with cues by the text editing software. Follow capitalization, punctuation, and indentation norms. Remember to capitalize the names of proprietary items such as licensed software.

- Define acronyms and abbreviations prior to using them.

Finally, always consider carefully the context of information provided. Know your audience. Thoughtfully consider if a statement is clearly supported by the information provided without leaving your reader confused. Remember that by the time you are writing a report, you should know the information inside and out, but your audience is reading your report to learn.

Standard Components of a Formal Technical Report

Technical reports should be organized into sections and are typically in the order described in this section. While this is the recommended order, certain reports may lend themselves to either reordering sections and/or excluding sections.

The format for this page may vary, however, the following information is always included: report title, who the report was prepared for, who the report was prepared by, and the date of submission. This is not a numbered page of the report.

An abstract is a concise description of the report including its purpose and most important results . An abstract should not be longer than half a page, single-spaced, and must not contain figures or make reference to them. Technical authors are generally so focused on results that they neglect to clearly state the purpose for the work. That purpose is derived from the objectives or goals, most commonly provided by the person who assigned the work. In stating the purpose, it is critical to include key words that would be used in a database search since searches of abstracts are commonly used by professionals to find information they need to do their jobs and make important decisions. Results are summarized in the abstract but how much quantitative information is provided varies with report audience and purpose. It is common to include maximum percent error found in the experimental results as compared to theory. Do not use any specific technical jargon, abbreviations, or acronyms. This is not a numbered page of the report.

Table of Contents

Include all the report sections and appendices. Typically, sub-sections are also listed. This is not a numbered page of the report.

The Table of Contents is easy to include if you properly use the power of the software used to generate the report. The Table of Contents can be automatically generated and updated if the author uses built in report headings provided in the styles menu. It is worth the time and effort to learn these tools since their application are ultimately time-savers for report writers. Directions are provided in Appendix B on creating a Table of Contents in MS Word using section headings.

Introduction

The length of the Introduction depends on the purpose but the author should strive for brevity, clarity, and interest. Provide the objective(s) of the work, a brief description of the problem, and how it is to be attacked. Provide the reader with an overview of why the work was performed, how the work was performed, and the most interesting results. This can usually be accomplished with ease if the work has clearly stated objectives.

Additionally, the introduction of a technical report concludes with a description of the sections that follow the Introduction. This is done to help the reader get some more detailed information about what might be found in each of the report sections included in the body of the report (this does not include appendices). This can feel awkward but providing that information is the accepted standard practice across industries.

Be careful not to use specific technical jargon or abbreviations such as using the term “oscope” instead of “oscilloscope”. Also, make sure to define any acronyms or abbreviations prior to using them. For example, in a surveying lab report a student might want to refer to the electronic distance measuring (EDM) device. The first time the device is referred to, spell out what the acronym stands for before using the acronym, as demonstrated in the previous sentence. Apply this practice throughout wherever an acronym or abbreviation is used but not yet defined within the report.

Background Theory

The purpose of this section is to include, if necessary, a discussion of relevant background theory. Include theory needed to understand subsequent sections that either the reading audience does not already comprehend or is tied to the purpose for the work and report. For example, a report on resistor-capacitor electric circuits that includes measurement of phase shift would likely include a theoretical description of phase shift. In deciding what should or should not be included as background theory, consider presenting any material specific to the work being reported on that you had to learn prior to performing the work including theoretical equations used to calculate theoretical values that are compared to measured values. This section may be divided into subsections if appropriate. Keep the discussion brief without compromising on content relevant to understanding and refer the reader to and cite outside sources of information where appropriate.

The purpose of this section is to provide detailed development of any design included in the report. Do not provide a design section if there is no design aspect to the work. Be sure to introduce and describe the design work within the context of the problem statement using sentences; a series of equations without description and context is insufficient. Use citations if you wish to refer the reader to reference material. Divide this section into subsections where appropriate. For example, a project may consist of designing several circuits that are subsequently interconnected; you may choose to treat each circuit design in its own subsection. The process followed to develop the design should be presented as generally as possible then applied using specific numbers for the work performed. Ultimately, the section must provide the actual design tested and include a clear presentation of how that design was developed.

Theoretical Analysis

Although a theoretical analysis might be part of a design, the author needs to decide if that analysis should be included as part of the design section or a separate section. Typically, any theoretical work performed to develop the design would be included in the design section but any theoretical analysis performed on the design would be included in a separate section. Do not provide a theoretical analysis section if the theoretical work is all described as part of background theory and design sections. However, in most cases, a theoretical analysis section is included to provide important details of all analyses performed. Be brief. It is not necessary to show every step; sentences can be used to describe the intermediate steps. Furthermore, if there are many steps, the reader should be directed to an appendix for complete details. Make sure to perform the analysis with the specific numbers for the work performed leading to the theoretical values reported on and compared to experimental values in the results section of the report. Worth repeating: perform the analyses resulting in the numbers that are included as the theoretical values in the results section of the report. Upon reading the results section, the reader should be familiar with the theoretical values presented there because the reader already saw them in this section.

This section varies depending on requirements of the one who assigned the work and the audience. At a minimum, the author discusses the procedure by describing the method used to test a theory, verify a design or conduct a process. Presentation of the procedure may vary significantly for different fields and different audiences, however, for all fields, the author should BE BRIEF and get to the point . Like with any written work, if it is unnecessarily wordy, the reader becomes bored and the author no longer has an audience. Also, the procedure section should never include specific measurements/results, discussion of results, or explanation of possible error sources. Make sure all diagrams provided are numbered, titled, and clearly labeled.

Depending on the situation, there are two likely types of procedure sections. In one case, a detailed procedure may have already been supplied or perhaps it is not desirable to provide a detailed description due to proprietary work. In another case, it might be the author’s job to develop and provide all the detail so work can be duplicated. The latter is more common in academic lab settings. Writing guidelines for these possible procedure sections are provided below.

Procedure Type 1

Use this procedure type if you have been supplied with a detailed procedure describing the steps required to complete the work or detailed procedure is not to be supplied to potential readers (procedure may be proprietary). Briefly describe the method employed to complete the work. This is meant to be a brief procedural description capturing the intention of the work, not the details. The reader may be referred to the appendix for detailed procedure steps. The following list provides considerations for this type of procedure section.

- Example: For measurements made over a range of input settings, provide the actual range without including the details of the specific input settings or order data was taken (unless order affects results).

- If required by the person who assigned the work, include the detailed procedure in the appendix.

- MUST provide detailed diagram(s) of all applicable experimental set-ups (i.e. circuit diagram) that include specific information about the set-up, such as resistor values.

- Provide diagrams and/or pictures that will further assist the reader in understanding the procedural description.

- Provide a details of any work performed for which prescribed steps were not provided and that the author deems necessary for the reader’s comprehension.

- To test the theory of superposition, the circuit shown in Figure 1 is employed. The circuit is constructed on the lab bench and using MultismTM, a circuit simulation software. In both settings, a multimeter is used to measure the output voltage, as shown in Figure 1, for the following three cases: (1) Source 1 on and Source 2 off, (2) Source 1 off and Source 2 on, and (3) both sources on. These measurements are compared to the output voltage derived using theory as described earlier. Refer to the appendix for further detail or procedure.