Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

1. Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

2. Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

Find academic papers related to your research topic faster. Try Research on Paperpal

3. Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

4. Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

5. Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

6. Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

Strengthen your literature review with factual insights. Try Research on Paperpal for free!

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Write and Cite as you go with Paperpal Research. Start now for free.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

Whether you’re exploring a new research field or finding new angles to develop an existing topic, sifting through hundreds of papers can take more time than you have to spare. But what if you could find science-backed insights with verified citations in seconds? That’s the power of Paperpal’s new Research feature!

How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Paperpal, an AI writing assistant, integrates powerful academic search capabilities within its writing platform. With the Research feature, you get 100% factual insights, with citations backed by 250M+ verified research articles, directly within your writing interface with the option to save relevant references in your Citation Library. By eliminating the need to switch tabs to find answers to all your research questions, Paperpal saves time and helps you stay focused on your writing.

Here’s how to use the Research feature:

- Ask a question: Get started with a new document on paperpal.com. Click on the “Research” feature and type your question in plain English. Paperpal will scour over 250 million research articles, including conference papers and preprints, to provide you with accurate insights and citations.

- Review and Save: Paperpal summarizes the information, while citing sources and listing relevant reads. You can quickly scan the results to identify relevant references and save these directly to your built-in citations library for later access.

- Cite with Confidence: Paperpal makes it easy to incorporate relevant citations and references into your writing, ensuring your arguments are well-supported by credible sources. This translates to a polished, well-researched literature review.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a good literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses. By combining effortless research with an easy citation process, Paperpal Research streamlines the literature review process and empowers you to write faster and with more confidence. Try Paperpal Research now and see for yourself.

Frequently asked questions

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.

Literature reviews are essential components of academic and research papers, and various strategies can be employed to conduct them effectively. If you want to know how to write a literature review for a research paper, here are four common approaches that are often used by researchers. Chronological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the chronological order of publication. It helps to trace the development of a topic over time, showing how ideas, theories, and research have evolved. Thematic Review: Thematic reviews focus on identifying and analyzing themes or topics that cut across different studies. Instead of organizing the literature chronologically, it is grouped by key themes or concepts, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of various aspects of the topic. Methodological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the research methods employed in different studies. It helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies and allows the reader to evaluate the reliability and validity of the research findings. Theoretical Review: A theoretical review examines the literature based on the theoretical frameworks used in different studies. This approach helps to identify the key theories that have been applied to the topic and assess their contributions to the understanding of the subject. It’s important to note that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, and a literature review may combine elements of more than one approach. The choice of strategy depends on the research question, the nature of the literature available, and the goals of the review. Additionally, other strategies, such as integrative reviews or systematic reviews, may be employed depending on the specific requirements of the research.

The literature review format can vary depending on the specific publication guidelines. However, there are some common elements and structures that are often followed. Here is a general guideline for the format of a literature review: Introduction: Provide an overview of the topic. Define the scope and purpose of the literature review. State the research question or objective. Body: Organize the literature by themes, concepts, or chronology. Critically analyze and evaluate each source. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the studies. Highlight any methodological limitations or biases. Identify patterns, connections, or contradictions in the existing research. Conclusion: Summarize the key points discussed in the literature review. Highlight the research gap. Address the research question or objective stated in the introduction. Highlight the contributions of the review and suggest directions for future research.

Both annotated bibliographies and literature reviews involve the examination of scholarly sources. While annotated bibliographies focus on individual sources with brief annotations, literature reviews provide a more in-depth, integrated, and comprehensive analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. The key differences are as follows:

References

- Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review. Journal of criminal justice education , 24 (2), 218-234.

- Pan, M. L. (2016). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Taylor & Francis.

- Cantero, C. (2019). How to write a literature review. San José State University Writing Center .

Paperpal is an AI writing assistant that help academics write better, faster with real-time suggestions for in-depth language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of research manuscripts enhanced by professional academic editors, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- How Long Should a Chapter Be?

- How to Use Paperpal to Generate Emails & Cover Letters?

6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how to avoid it, you may also like, how to write a high-quality conference paper, how paperpal’s research feature helps you develop and..., how paperpal is enhancing academic productivity and accelerating..., how to write a successful book chapter for..., academic editing: how to self-edit academic text with..., 4 ways paperpal encourages responsible writing with ai, what are scholarly sources and where can you..., how to write a hypothesis types and examples , measuring academic success: definition & strategies for excellence, what is academic writing: tips for students.

The Guide to Thematic Analysis

- What is Thematic Analysis?

- Advantages of Thematic Analysis

- Disadvantages of Thematic Analysis

- Thematic Analysis Examples

- How to Do Thematic Analysis

- Thematic Coding

- Collaborative Thematic Analysis

- Thematic Analysis Software

- Thematic Analysis in Mixed Methods Approach

- Abductive Thematic Analysis

- Deductive Thematic Analysis

- Inductive Thematic Analysis

- Reflexive Thematic Analysis

- Thematic Analysis in Observations

- Thematic Analysis in Surveys

- Thematic Analysis for Interviews

- Thematic Analysis for Focus Groups

- Thematic Analysis for Case Studies

- Thematic Analysis of Secondary Data

- Introduction

What is a thematic literature review?

Advantages of a thematic literature review, structuring and writing a thematic literature review.

- Thematic Analysis vs. Phenomenology

- Thematic vs. Content Analysis

- Thematic Analysis vs. Grounded Theory

- Thematic Analysis vs. Narrative Analysis

- Thematic Analysis vs. Discourse Analysis

- Thematic Analysis vs. Framework Analysis

- Thematic Analysis in Social Work

- Thematic Analysis in Psychology

- Thematic Analysis in Educational Research

- Thematic Analysis in UX Research

- How to Present Thematic Analysis Results

- Increasing Rigor in Thematic Analysis

- Peer Review in Thematic Analysis

Thematic Analysis Literature Review

A thematic literature review serves as a critical tool for synthesizing research findings within a specific subject area. By categorizing existing literature into themes, this method offers a structured approach to identify and analyze patterns and trends across studies. The primary goal is to provide a clear and concise overview that aids scholars and practitioners in understanding the key discussions and developments within a field. Unlike traditional literature reviews , which may adopt a chronological approach or focus on individual studies, a thematic literature review emphasizes the aggregation of findings through key themes and thematic connections. This introduction sets the stage for a detailed examination of what constitutes a thematic literature review, its benefits, and guidance on effectively structuring and writing one.

A thematic literature review methodically organizes and examines a body of literature by identifying, analyzing, and reporting themes found within texts such as journal articles, conference proceedings, dissertations, and other forms of academic writing. While a particular journal article may offer some specific insight, a synthesis of knowledge through a literature review can provide a comprehensive overview of theories across relevant sources in a particular field.

Unlike other review types that might organize literature chronologically or by methodology , a thematic review focuses on recurring themes or patterns across a collection of works. This approach enables researchers to draw together previous research to synthesize findings from different research contexts and methodologies, highlighting the overarching trends and insights within a field.

At its core, a thematic approach to a literature review research project involves several key steps. Initially, it requires the comprehensive collection of relevant literature that aligns with the review's research question or objectives. Following this, the process entails a meticulous analysis of the texts to identify common themes that emerge across the studies. These themes are not pre-defined but are discovered through a careful reading and synthesis of the literature.

The thematic analysis process is iterative, often involving the refinement of themes as the review progresses. It allows for the integration of a broad range of literature, facilitating a multidimensional understanding of the research topic. By organizing literature thematically, the review illuminates how various studies contribute to each theme, providing insights into the depth and breadth of research in the area.

A thematic literature review thus serves as a foundational element in research, offering a nuanced and comprehensive perspective on a topic. It not only aids in identifying gaps in the existing literature but also guides future research directions by underscoring areas that warrant further investigation. Ultimately, a thematic literature review empowers researchers to construct a coherent narrative that weaves together disparate studies into a unified analysis.

Organize your literature search with ATLAS.ti

Collect and categorize documents to identify gaps and key findings with ATLAS.ti. Download a free trial.

Conducting a literature review thematically provides a comprehensive and nuanced synthesis of research findings, distinguishing it from other types of literature reviews. Its structured approach not only facilitates a deeper understanding of the subject area but also enhances the clarity and relevance of the review. Here are three significant advantages of employing a thematic analysis in literature reviews.

Enhanced understanding of the research field

Thematic literature reviews allow for a detailed exploration of the research landscape, presenting themes that capture the essence of the subject area. By identifying and analyzing these themes, reviewers can construct a narrative that reflects the complexity and multifaceted nature of the field.

This process aids in uncovering underlying patterns and relationships, offering a more profound and insightful examination of the literature. As a result, readers gain an enriched understanding of the key concepts, debates, and evolutionary trajectories within the research area.

Identification of research gaps and trends

One of the pivotal benefits of a thematic literature review is its ability to highlight gaps in the existing body of research. By systematically organizing the literature into themes, reviewers can pinpoint areas that are under-explored or warrant further investigation.

Additionally, this method can reveal emerging trends and shifts in research focus, guiding scholars toward promising areas for future study. The thematic structure thus serves as a roadmap, directing researchers toward uncharted territories and new research questions .

Facilitates comparative analysis and integration of findings

A thematic literature review excels in synthesizing findings from diverse studies, enabling a coherent and integrated overview. By concentrating on themes rather than individual studies, the review can draw comparisons and contrasts across different research contexts and methodologies . This comparative analysis enriches the review, offering a panoramic view of the field that acknowledges both consensus and divergence among researchers.

Moreover, the thematic framework supports the integration of findings, presenting a unified and comprehensive portrayal of the research area. Such integration is invaluable for scholars seeking to navigate the extensive body of literature and extract pertinent insights relevant to their own research questions or objectives.

The process of structuring and writing a thematic literature review is pivotal in presenting research in a clear, coherent, and impactful manner. This review type necessitates a methodical approach to not only unearth and categorize key themes but also to articulate them in a manner that is both accessible and informative to the reader. The following sections outline essential stages in the thematic analysis process for literature reviews , offering a structured pathway from initial planning to the final presentation of findings.

Identifying and categorizing themes

The initial phase in a thematic literature review is the identification of themes within the collected body of literature. This involves a detailed examination of texts to discern patterns, concepts, and ideas that recur across the research landscape. Effective identification hinges on a thorough and nuanced reading of the literature, where the reviewer actively engages with the content to extract and note significant thematic elements. Once identified, these themes must be meticulously categorized, often requiring the reviewer to discern between overarching themes and more nuanced sub-themes, ensuring a logical and hierarchical organization of the review content.

Analyzing and synthesizing themes

After categorizing the themes, the next step involves a deeper analysis and synthesis of the identified themes. This stage is critical for understanding the relationships between themes and for interpreting the broader implications of the thematic findings. Analysis may reveal how themes evolve over time, differ across methodologies or contexts, or converge to highlight predominant trends in the research area. Synthesis involves integrating insights from various studies to construct a comprehensive narrative that encapsulates the thematic essence of the literature, offering new interpretations or revealing gaps in existing research.

Presenting and discussing findings

The final stage of the thematic literature review is the discussion of the thematic findings in a research paper or presentation. This entails not only a descriptive account of identified themes but also a critical examination of their significance within the research field. Each theme should be discussed in detail, elucidating its relevance, the extent of research support, and its implications for future studies. The review should culminate in a coherent and compelling narrative that not only summarizes the key thematic findings but also situates them within the broader research context, offering valuable insights and directions for future inquiry.

Gain a comprehensive understanding of your data with ATLAS.ti

Analyze qualitative data with specific themes that offer insights. See how with a free trial.

Conducting a Literature Review

- Getting Started

- Developing a Question

- Searching the Literature

- Identifying Peer-Reviewed Resources

- Managing Results

Analyzing the Literature

- Writing the Review

Need Help? Ask Your librarian!

Evidence synthesis and critical appraisal are two distinct but interrelated processes in the field of evidence-based practice and research. Here's a breakdown of the differences between them:

Critical Appraisal:

- Definition : Critical appraisal involves systematically evaluating the quality, relevance, and validity of research studies or evidence sources. It aims to assess the strengths and weaknesses of individual studies to determine their trustworthiness and applicability to a particular research question or clinical scenario.

- Focus : Critical appraisal focuses on examining the methodology, design, data analysis, and results of research studies. It involves assessing factors such as study design, sample size, bias, confounding variables, statistical methods, and generalizability.

- Purpose : The purpose of critical appraisal is to identify high-quality evidence that can inform decision-making in healthcare practice, policy, or research. It helps researchers and practitioners assess the credibility and reliability of evidence sources and make informed judgments about their use in practice.

Evidence Synthesis:

- Definition : Evidence synthesis involves systematically collecting, analyzing, and integrating evidence from multiple sources to generate new knowledge, insights, or conclusions about a particular topic or research question. It aims to aggregate and synthesize findings from individual studies to produce a comprehensive summary of the available evidence.

- Focus : Evidence synthesis encompasses a variety of methods, including systematic reviews, meta-analyses, scoping reviews, and narrative reviews. It focuses on synthesizing data, findings, and conclusions from multiple studies to provide a comprehensive overview of the evidence base on a particular topic.

- Purpose : The purpose of evidence synthesis is to provide stakeholders with a robust and comprehensive summary of the existing evidence on a particular topic or research question. It helps identify patterns, trends, inconsistencies, and gaps in the literature, informing decision-making, guiding policy development, and identifying future research priorities.

In summary, critical appraisal involves assessing the quality and validity of individual research studies, while evidence synthesis involves aggregating and synthesizing findings from multiple studies to generate new knowledge or insights about a particular topic. While they are distinct processes, they are often conducted sequentially, with critical appraisal informing the selection and inclusion of studies in evidence synthesis. Together, critical appraisal and evidence synthesis play essential roles in evidence-based practice and research,

Synthesizing the Articles

Literature reviews synthesize large amounts of information and present it in a coherent, organized fashion. In a literature review you will be combining material from several texts to create a new text – your literature review.

You will use common points among the sources you have gathered to help you synthesize the material. This will help ensure that your literature review is organized by subtopic, not by source. This means various authors' names can appear and reappear throughout the literature review, and each paragraph will mention several different authors.

When you shift from writing summaries of the content of a source to synthesizing content from sources, there is a number things you must keep in mind:

- Look for specific connections and or links between your sources and how those relate to your thesis or question.

- When writing and organizing your literature review be aware that your readers need to understand how and why the information from the different sources overlap.

- Organize your literature review by the themes you find within your sources or themes you have identified.

You can use a synthesis chart to help keep your sources and main ideas organized. Here are some examples:

- Virginia Commonwealth University Literature Matrix

- Johns Hopkins University Literature Review Matrix

- Writing A Literature Review and Using a Synthesis Matrix Tutorial from NC State University

California State University, Northridge. (2017). Literature Review How-To: Synthesizing Sources. Retrieved from https://libguides.csun.edu/literature-review/synthesis.

Things to Think About

Before you begin to analyze and synthesize the articles you have selected, read quickly through each article to get a sense of what they are about. One way to do this is to read the abstract and the conclusion for each article.

It is also helpful at this stage to begin sorting your articles by type of source; this will help you with the next step in the process. Many papers (but not all) fall into one of two categories:

- Primary source: a report by the original researchers of a study.

- Secondary source: a description or summary of research by somebody other than the original author(s), like a review article.

These are a selection of questions to consider while reading each article selected for your literature review.

Primary Sources:

- Author and Year

- Purpose of Study

- Type of Study

- Data Collection Method

- Major Findings

- Recommendations

- Key thoughts/comments (eg. strengths and weaknesses)

Secondary Sources (ie. reviews)

- Author and year

- Review questions/purpose

- Key definitions

- Review boundaries

- Appraisal criteria

- Synthesis of studies

- Summary/conclusions

Cronin, P., Ryan, F., & Coughlan, M. (2008). Undertaking a literature review: A step-by-step approach. British Journal of Nursing, 17 (1), 38-43. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/2wLeCge .

When Am I Done?

You are done with your literature review synthesis when :

- You are not finding any new ideas,

- When you encounter the same authors repeatedly, and/or

- When you feel that you have a strong understanding of the topic

- << Previous: Managing Results

- Next: Writing the Review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 16, 2024 3:40 PM

- URL: https://libguides.libraries.wsu.edu/litreview

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Lau F, Kuziemsky C, editors. Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet]. Victoria (BC): University of Victoria; 2017 Feb 27.

Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet].

Chapter 9 methods for literature reviews.

Guy Paré and Spyros Kitsiou .

9.1. Introduction

Literature reviews play a critical role in scholarship because science remains, first and foremost, a cumulative endeavour ( vom Brocke et al., 2009 ). As in any academic discipline, rigorous knowledge syntheses are becoming indispensable in keeping up with an exponentially growing eHealth literature, assisting practitioners, academics, and graduate students in finding, evaluating, and synthesizing the contents of many empirical and conceptual papers. Among other methods, literature reviews are essential for: (a) identifying what has been written on a subject or topic; (b) determining the extent to which a specific research area reveals any interpretable trends or patterns; (c) aggregating empirical findings related to a narrow research question to support evidence-based practice; (d) generating new frameworks and theories; and (e) identifying topics or questions requiring more investigation ( Paré, Trudel, Jaana, & Kitsiou, 2015 ).

Literature reviews can take two major forms. The most prevalent one is the “literature review” or “background” section within a journal paper or a chapter in a graduate thesis. This section synthesizes the extant literature and usually identifies the gaps in knowledge that the empirical study addresses ( Sylvester, Tate, & Johnstone, 2013 ). It may also provide a theoretical foundation for the proposed study, substantiate the presence of the research problem, justify the research as one that contributes something new to the cumulated knowledge, or validate the methods and approaches for the proposed study ( Hart, 1998 ; Levy & Ellis, 2006 ).

The second form of literature review, which is the focus of this chapter, constitutes an original and valuable work of research in and of itself ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Rather than providing a base for a researcher’s own work, it creates a solid starting point for all members of the community interested in a particular area or topic ( Mulrow, 1987 ). The so-called “review article” is a journal-length paper which has an overarching purpose to synthesize the literature in a field, without collecting or analyzing any primary data ( Green, Johnson, & Adams, 2006 ).

When appropriately conducted, review articles represent powerful information sources for practitioners looking for state-of-the art evidence to guide their decision-making and work practices ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Further, high-quality reviews become frequently cited pieces of work which researchers seek out as a first clear outline of the literature when undertaking empirical studies ( Cooper, 1988 ; Rowe, 2014 ). Scholars who track and gauge the impact of articles have found that review papers are cited and downloaded more often than any other type of published article ( Cronin, Ryan, & Coughlan, 2008 ; Montori, Wilczynski, Morgan, Haynes, & Hedges, 2003 ; Patsopoulos, Analatos, & Ioannidis, 2005 ). The reason for their popularity may be the fact that reading the review enables one to have an overview, if not a detailed knowledge of the area in question, as well as references to the most useful primary sources ( Cronin et al., 2008 ). Although they are not easy to conduct, the commitment to complete a review article provides a tremendous service to one’s academic community ( Paré et al., 2015 ; Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ). Most, if not all, peer-reviewed journals in the fields of medical informatics publish review articles of some type.

The main objectives of this chapter are fourfold: (a) to provide an overview of the major steps and activities involved in conducting a stand-alone literature review; (b) to describe and contrast the different types of review articles that can contribute to the eHealth knowledge base; (c) to illustrate each review type with one or two examples from the eHealth literature; and (d) to provide a series of recommendations for prospective authors of review articles in this domain.

9.2. Overview of the Literature Review Process and Steps

As explained in Templier and Paré (2015) , there are six generic steps involved in conducting a review article:

- formulating the research question(s) and objective(s),

- searching the extant literature,

- screening for inclusion,

- assessing the quality of primary studies,

- extracting data, and

- analyzing data.

Although these steps are presented here in sequential order, one must keep in mind that the review process can be iterative and that many activities can be initiated during the planning stage and later refined during subsequent phases ( Finfgeld-Connett & Johnson, 2013 ; Kitchenham & Charters, 2007 ).

Formulating the research question(s) and objective(s): As a first step, members of the review team must appropriately justify the need for the review itself ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ), identify the review’s main objective(s) ( Okoli & Schabram, 2010 ), and define the concepts or variables at the heart of their synthesis ( Cooper & Hedges, 2009 ; Webster & Watson, 2002 ). Importantly, they also need to articulate the research question(s) they propose to investigate ( Kitchenham & Charters, 2007 ). In this regard, we concur with Jesson, Matheson, and Lacey (2011) that clearly articulated research questions are key ingredients that guide the entire review methodology; they underscore the type of information that is needed, inform the search for and selection of relevant literature, and guide or orient the subsequent analysis. Searching the extant literature: The next step consists of searching the literature and making decisions about the suitability of material to be considered in the review ( Cooper, 1988 ). There exist three main coverage strategies. First, exhaustive coverage means an effort is made to be as comprehensive as possible in order to ensure that all relevant studies, published and unpublished, are included in the review and, thus, conclusions are based on this all-inclusive knowledge base. The second type of coverage consists of presenting materials that are representative of most other works in a given field or area. Often authors who adopt this strategy will search for relevant articles in a small number of top-tier journals in a field ( Paré et al., 2015 ). In the third strategy, the review team concentrates on prior works that have been central or pivotal to a particular topic. This may include empirical studies or conceptual papers that initiated a line of investigation, changed how problems or questions were framed, introduced new methods or concepts, or engendered important debate ( Cooper, 1988 ). Screening for inclusion: The following step consists of evaluating the applicability of the material identified in the preceding step ( Levy & Ellis, 2006 ; vom Brocke et al., 2009 ). Once a group of potential studies has been identified, members of the review team must screen them to determine their relevance ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ). A set of predetermined rules provides a basis for including or excluding certain studies. This exercise requires a significant investment on the part of researchers, who must ensure enhanced objectivity and avoid biases or mistakes. As discussed later in this chapter, for certain types of reviews there must be at least two independent reviewers involved in the screening process and a procedure to resolve disagreements must also be in place ( Liberati et al., 2009 ; Shea et al., 2009 ). Assessing the quality of primary studies: In addition to screening material for inclusion, members of the review team may need to assess the scientific quality of the selected studies, that is, appraise the rigour of the research design and methods. Such formal assessment, which is usually conducted independently by at least two coders, helps members of the review team refine which studies to include in the final sample, determine whether or not the differences in quality may affect their conclusions, or guide how they analyze the data and interpret the findings ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ). Ascribing quality scores to each primary study or considering through domain-based evaluations which study components have or have not been designed and executed appropriately makes it possible to reflect on the extent to which the selected study addresses possible biases and maximizes validity ( Shea et al., 2009 ). Extracting data: The following step involves gathering or extracting applicable information from each primary study included in the sample and deciding what is relevant to the problem of interest ( Cooper & Hedges, 2009 ). Indeed, the type of data that should be recorded mainly depends on the initial research questions ( Okoli & Schabram, 2010 ). However, important information may also be gathered about how, when, where and by whom the primary study was conducted, the research design and methods, or qualitative/quantitative results ( Cooper & Hedges, 2009 ). Analyzing and synthesizing data : As a final step, members of the review team must collate, summarize, aggregate, organize, and compare the evidence extracted from the included studies. The extracted data must be presented in a meaningful way that suggests a new contribution to the extant literature ( Jesson et al., 2011 ). Webster and Watson (2002) warn researchers that literature reviews should be much more than lists of papers and should provide a coherent lens to make sense of extant knowledge on a given topic. There exist several methods and techniques for synthesizing quantitative (e.g., frequency analysis, meta-analysis) and qualitative (e.g., grounded theory, narrative analysis, meta-ethnography) evidence ( Dixon-Woods, Agarwal, Jones, Young, & Sutton, 2005 ; Thomas & Harden, 2008 ).

9.3. Types of Review Articles and Brief Illustrations

EHealth researchers have at their disposal a number of approaches and methods for making sense out of existing literature, all with the purpose of casting current research findings into historical contexts or explaining contradictions that might exist among a set of primary research studies conducted on a particular topic. Our classification scheme is largely inspired from Paré and colleagues’ (2015) typology. Below we present and illustrate those review types that we feel are central to the growth and development of the eHealth domain.

9.3.1. Narrative Reviews

The narrative review is the “traditional” way of reviewing the extant literature and is skewed towards a qualitative interpretation of prior knowledge ( Sylvester et al., 2013 ). Put simply, a narrative review attempts to summarize or synthesize what has been written on a particular topic but does not seek generalization or cumulative knowledge from what is reviewed ( Davies, 2000 ; Green et al., 2006 ). Instead, the review team often undertakes the task of accumulating and synthesizing the literature to demonstrate the value of a particular point of view ( Baumeister & Leary, 1997 ). As such, reviewers may selectively ignore or limit the attention paid to certain studies in order to make a point. In this rather unsystematic approach, the selection of information from primary articles is subjective, lacks explicit criteria for inclusion and can lead to biased interpretations or inferences ( Green et al., 2006 ). There are several narrative reviews in the particular eHealth domain, as in all fields, which follow such an unstructured approach ( Silva et al., 2015 ; Paul et al., 2015 ).

Despite these criticisms, this type of review can be very useful in gathering together a volume of literature in a specific subject area and synthesizing it. As mentioned above, its primary purpose is to provide the reader with a comprehensive background for understanding current knowledge and highlighting the significance of new research ( Cronin et al., 2008 ). Faculty like to use narrative reviews in the classroom because they are often more up to date than textbooks, provide a single source for students to reference, and expose students to peer-reviewed literature ( Green et al., 2006 ). For researchers, narrative reviews can inspire research ideas by identifying gaps or inconsistencies in a body of knowledge, thus helping researchers to determine research questions or formulate hypotheses. Importantly, narrative reviews can also be used as educational articles to bring practitioners up to date with certain topics of issues ( Green et al., 2006 ).

Recently, there have been several efforts to introduce more rigour in narrative reviews that will elucidate common pitfalls and bring changes into their publication standards. Information systems researchers, among others, have contributed to advancing knowledge on how to structure a “traditional” review. For instance, Levy and Ellis (2006) proposed a generic framework for conducting such reviews. Their model follows the systematic data processing approach comprised of three steps, namely: (a) literature search and screening; (b) data extraction and analysis; and (c) writing the literature review. They provide detailed and very helpful instructions on how to conduct each step of the review process. As another methodological contribution, vom Brocke et al. (2009) offered a series of guidelines for conducting literature reviews, with a particular focus on how to search and extract the relevant body of knowledge. Last, Bandara, Miskon, and Fielt (2011) proposed a structured, predefined and tool-supported method to identify primary studies within a feasible scope, extract relevant content from identified articles, synthesize and analyze the findings, and effectively write and present the results of the literature review. We highly recommend that prospective authors of narrative reviews consult these useful sources before embarking on their work.

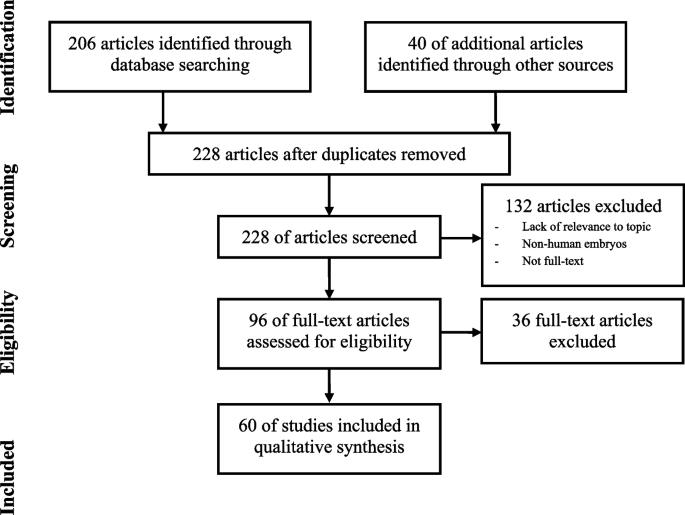

Darlow and Wen (2015) provide a good example of a highly structured narrative review in the eHealth field. These authors synthesized published articles that describe the development process of mobile health ( m-health ) interventions for patients’ cancer care self-management. As in most narrative reviews, the scope of the research questions being investigated is broad: (a) how development of these systems are carried out; (b) which methods are used to investigate these systems; and (c) what conclusions can be drawn as a result of the development of these systems. To provide clear answers to these questions, a literature search was conducted on six electronic databases and Google Scholar . The search was performed using several terms and free text words, combining them in an appropriate manner. Four inclusion and three exclusion criteria were utilized during the screening process. Both authors independently reviewed each of the identified articles to determine eligibility and extract study information. A flow diagram shows the number of studies identified, screened, and included or excluded at each stage of study selection. In terms of contributions, this review provides a series of practical recommendations for m-health intervention development.

9.3.2. Descriptive or Mapping Reviews

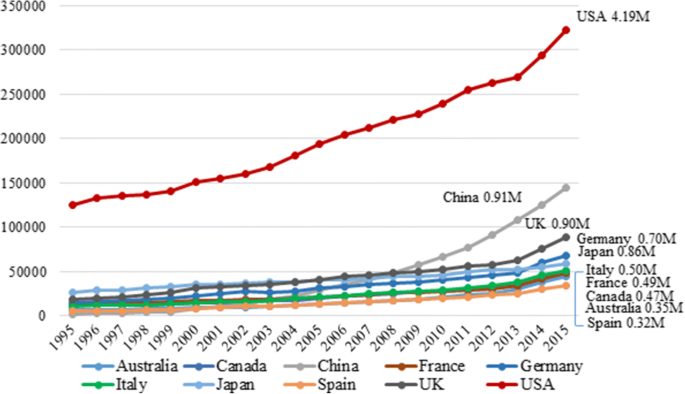

The primary goal of a descriptive review is to determine the extent to which a body of knowledge in a particular research topic reveals any interpretable pattern or trend with respect to pre-existing propositions, theories, methodologies or findings ( King & He, 2005 ; Paré et al., 2015 ). In contrast with narrative reviews, descriptive reviews follow a systematic and transparent procedure, including searching, screening and classifying studies ( Petersen, Vakkalanka, & Kuzniarz, 2015 ). Indeed, structured search methods are used to form a representative sample of a larger group of published works ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Further, authors of descriptive reviews extract from each study certain characteristics of interest, such as publication year, research methods, data collection techniques, and direction or strength of research outcomes (e.g., positive, negative, or non-significant) in the form of frequency analysis to produce quantitative results ( Sylvester et al., 2013 ). In essence, each study included in a descriptive review is treated as the unit of analysis and the published literature as a whole provides a database from which the authors attempt to identify any interpretable trends or draw overall conclusions about the merits of existing conceptualizations, propositions, methods or findings ( Paré et al., 2015 ). In doing so, a descriptive review may claim that its findings represent the state of the art in a particular domain ( King & He, 2005 ).

In the fields of health sciences and medical informatics, reviews that focus on examining the range, nature and evolution of a topic area are described by Anderson, Allen, Peckham, and Goodwin (2008) as mapping reviews . Like descriptive reviews, the research questions are generic and usually relate to publication patterns and trends. There is no preconceived plan to systematically review all of the literature although this can be done. Instead, researchers often present studies that are representative of most works published in a particular area and they consider a specific time frame to be mapped.

An example of this approach in the eHealth domain is offered by DeShazo, Lavallie, and Wolf (2009). The purpose of this descriptive or mapping review was to characterize publication trends in the medical informatics literature over a 20-year period (1987 to 2006). To achieve this ambitious objective, the authors performed a bibliometric analysis of medical informatics citations indexed in medline using publication trends, journal frequencies, impact factors, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) term frequencies, and characteristics of citations. Findings revealed that there were over 77,000 medical informatics articles published during the covered period in numerous journals and that the average annual growth rate was 12%. The MeSH term analysis also suggested a strong interdisciplinary trend. Finally, average impact scores increased over time with two notable growth periods. Overall, patterns in research outputs that seem to characterize the historic trends and current components of the field of medical informatics suggest it may be a maturing discipline (DeShazo et al., 2009).

9.3.3. Scoping Reviews

Scoping reviews attempt to provide an initial indication of the potential size and nature of the extant literature on an emergent topic (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Daudt, van Mossel, & Scott, 2013 ; Levac, Colquhoun, & O’Brien, 2010). A scoping review may be conducted to examine the extent, range and nature of research activities in a particular area, determine the value of undertaking a full systematic review (discussed next), or identify research gaps in the extant literature ( Paré et al., 2015 ). In line with their main objective, scoping reviews usually conclude with the presentation of a detailed research agenda for future works along with potential implications for both practice and research.

Unlike narrative and descriptive reviews, the whole point of scoping the field is to be as comprehensive as possible, including grey literature (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). Inclusion and exclusion criteria must be established to help researchers eliminate studies that are not aligned with the research questions. It is also recommended that at least two independent coders review abstracts yielded from the search strategy and then the full articles for study selection ( Daudt et al., 2013 ). The synthesized evidence from content or thematic analysis is relatively easy to present in tabular form (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Thomas & Harden, 2008 ).

One of the most highly cited scoping reviews in the eHealth domain was published by Archer, Fevrier-Thomas, Lokker, McKibbon, and Straus (2011) . These authors reviewed the existing literature on personal health record ( phr ) systems including design, functionality, implementation, applications, outcomes, and benefits. Seven databases were searched from 1985 to March 2010. Several search terms relating to phr s were used during this process. Two authors independently screened titles and abstracts to determine inclusion status. A second screen of full-text articles, again by two independent members of the research team, ensured that the studies described phr s. All in all, 130 articles met the criteria and their data were extracted manually into a database. The authors concluded that although there is a large amount of survey, observational, cohort/panel, and anecdotal evidence of phr benefits and satisfaction for patients, more research is needed to evaluate the results of phr implementations. Their in-depth analysis of the literature signalled that there is little solid evidence from randomized controlled trials or other studies through the use of phr s. Hence, they suggested that more research is needed that addresses the current lack of understanding of optimal functionality and usability of these systems, and how they can play a beneficial role in supporting patient self-management ( Archer et al., 2011 ).

9.3.4. Forms of Aggregative Reviews

Healthcare providers, practitioners, and policy-makers are nowadays overwhelmed with large volumes of information, including research-based evidence from numerous clinical trials and evaluation studies, assessing the effectiveness of health information technologies and interventions ( Ammenwerth & de Keizer, 2004 ; Deshazo et al., 2009 ). It is unrealistic to expect that all these disparate actors will have the time, skills, and necessary resources to identify the available evidence in the area of their expertise and consider it when making decisions. Systematic reviews that involve the rigorous application of scientific strategies aimed at limiting subjectivity and bias (i.e., systematic and random errors) can respond to this challenge.

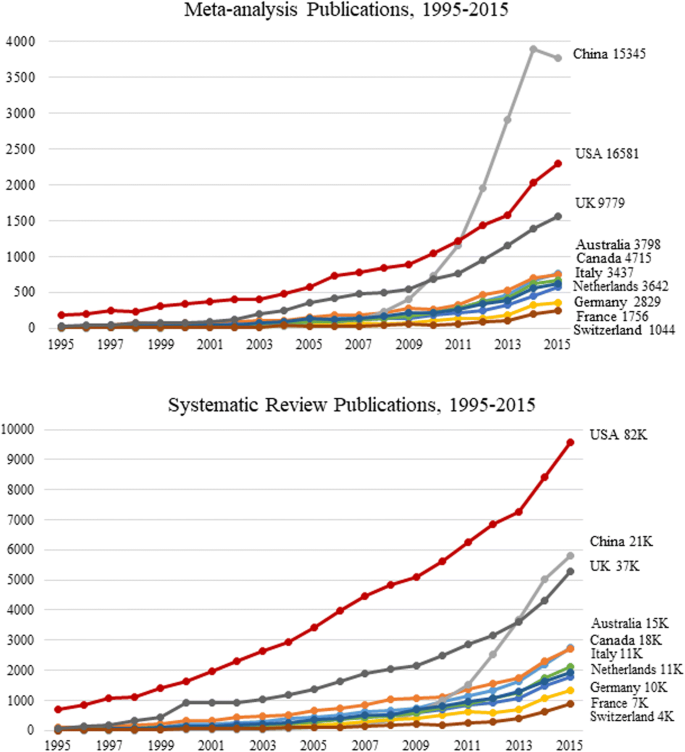

Systematic reviews attempt to aggregate, appraise, and synthesize in a single source all empirical evidence that meet a set of previously specified eligibility criteria in order to answer a clearly formulated and often narrow research question on a particular topic of interest to support evidence-based practice ( Liberati et al., 2009 ). They adhere closely to explicit scientific principles ( Liberati et al., 2009 ) and rigorous methodological guidelines (Higgins & Green, 2008) aimed at reducing random and systematic errors that can lead to deviations from the truth in results or inferences. The use of explicit methods allows systematic reviews to aggregate a large body of research evidence, assess whether effects or relationships are in the same direction and of the same general magnitude, explain possible inconsistencies between study results, and determine the strength of the overall evidence for every outcome of interest based on the quality of included studies and the general consistency among them ( Cook, Mulrow, & Haynes, 1997 ). The main procedures of a systematic review involve:

- Formulating a review question and developing a search strategy based on explicit inclusion criteria for the identification of eligible studies (usually described in the context of a detailed review protocol).

- Searching for eligible studies using multiple databases and information sources, including grey literature sources, without any language restrictions.

- Selecting studies, extracting data, and assessing risk of bias in a duplicate manner using two independent reviewers to avoid random or systematic errors in the process.

- Analyzing data using quantitative or qualitative methods.

- Presenting results in summary of findings tables.

- Interpreting results and drawing conclusions.

Many systematic reviews, but not all, use statistical methods to combine the results of independent studies into a single quantitative estimate or summary effect size. Known as meta-analyses , these reviews use specific data extraction and statistical techniques (e.g., network, frequentist, or Bayesian meta-analyses) to calculate from each study by outcome of interest an effect size along with a confidence interval that reflects the degree of uncertainty behind the point estimate of effect ( Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009 ; Deeks, Higgins, & Altman, 2008 ). Subsequently, they use fixed or random-effects analysis models to combine the results of the included studies, assess statistical heterogeneity, and calculate a weighted average of the effect estimates from the different studies, taking into account their sample sizes. The summary effect size is a value that reflects the average magnitude of the intervention effect for a particular outcome of interest or, more generally, the strength of a relationship between two variables across all studies included in the systematic review. By statistically combining data from multiple studies, meta-analyses can create more precise and reliable estimates of intervention effects than those derived from individual studies alone, when these are examined independently as discrete sources of information.

The review by Gurol-Urganci, de Jongh, Vodopivec-Jamsek, Atun, and Car (2013) on the effects of mobile phone messaging reminders for attendance at healthcare appointments is an illustrative example of a high-quality systematic review with meta-analysis. Missed appointments are a major cause of inefficiency in healthcare delivery with substantial monetary costs to health systems. These authors sought to assess whether mobile phone-based appointment reminders delivered through Short Message Service ( sms ) or Multimedia Messaging Service ( mms ) are effective in improving rates of patient attendance and reducing overall costs. To this end, they conducted a comprehensive search on multiple databases using highly sensitive search strategies without language or publication-type restrictions to identify all rct s that are eligible for inclusion. In order to minimize the risk of omitting eligible studies not captured by the original search, they supplemented all electronic searches with manual screening of trial registers and references contained in the included studies. Study selection, data extraction, and risk of bias assessments were performed independently by two coders using standardized methods to ensure consistency and to eliminate potential errors. Findings from eight rct s involving 6,615 participants were pooled into meta-analyses to calculate the magnitude of effects that mobile text message reminders have on the rate of attendance at healthcare appointments compared to no reminders and phone call reminders.

Meta-analyses are regarded as powerful tools for deriving meaningful conclusions. However, there are situations in which it is neither reasonable nor appropriate to pool studies together using meta-analytic methods simply because there is extensive clinical heterogeneity between the included studies or variation in measurement tools, comparisons, or outcomes of interest. In these cases, systematic reviews can use qualitative synthesis methods such as vote counting, content analysis, classification schemes and tabulations, as an alternative approach to narratively synthesize the results of the independent studies included in the review. This form of review is known as qualitative systematic review.

A rigorous example of one such review in the eHealth domain is presented by Mickan, Atherton, Roberts, Heneghan, and Tilson (2014) on the use of handheld computers by healthcare professionals and their impact on access to information and clinical decision-making. In line with the methodological guidelines for systematic reviews, these authors: (a) developed and registered with prospero ( www.crd.york.ac.uk/ prospero / ) an a priori review protocol; (b) conducted comprehensive searches for eligible studies using multiple databases and other supplementary strategies (e.g., forward searches); and (c) subsequently carried out study selection, data extraction, and risk of bias assessments in a duplicate manner to eliminate potential errors in the review process. Heterogeneity between the included studies in terms of reported outcomes and measures precluded the use of meta-analytic methods. To this end, the authors resorted to using narrative analysis and synthesis to describe the effectiveness of handheld computers on accessing information for clinical knowledge, adherence to safety and clinical quality guidelines, and diagnostic decision-making.

In recent years, the number of systematic reviews in the field of health informatics has increased considerably. Systematic reviews with discordant findings can cause great confusion and make it difficult for decision-makers to interpret the review-level evidence ( Moher, 2013 ). Therefore, there is a growing need for appraisal and synthesis of prior systematic reviews to ensure that decision-making is constantly informed by the best available accumulated evidence. Umbrella reviews , also known as overviews of systematic reviews, are tertiary types of evidence synthesis that aim to accomplish this; that is, they aim to compare and contrast findings from multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses ( Becker & Oxman, 2008 ). Umbrella reviews generally adhere to the same principles and rigorous methodological guidelines used in systematic reviews. However, the unit of analysis in umbrella reviews is the systematic review rather than the primary study ( Becker & Oxman, 2008 ). Unlike systematic reviews that have a narrow focus of inquiry, umbrella reviews focus on broader research topics for which there are several potential interventions ( Smith, Devane, Begley, & Clarke, 2011 ). A recent umbrella review on the effects of home telemonitoring interventions for patients with heart failure critically appraised, compared, and synthesized evidence from 15 systematic reviews to investigate which types of home telemonitoring technologies and forms of interventions are more effective in reducing mortality and hospital admissions ( Kitsiou, Paré, & Jaana, 2015 ).

9.3.5. Realist Reviews

Realist reviews are theory-driven interpretative reviews developed to inform, enhance, or supplement conventional systematic reviews by making sense of heterogeneous evidence about complex interventions applied in diverse contexts in a way that informs policy decision-making ( Greenhalgh, Wong, Westhorp, & Pawson, 2011 ). They originated from criticisms of positivist systematic reviews which centre on their “simplistic” underlying assumptions ( Oates, 2011 ). As explained above, systematic reviews seek to identify causation. Such logic is appropriate for fields like medicine and education where findings of randomized controlled trials can be aggregated to see whether a new treatment or intervention does improve outcomes. However, many argue that it is not possible to establish such direct causal links between interventions and outcomes in fields such as social policy, management, and information systems where for any intervention there is unlikely to be a regular or consistent outcome ( Oates, 2011 ; Pawson, 2006 ; Rousseau, Manning, & Denyer, 2008 ).

To circumvent these limitations, Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey, and Walshe (2005) have proposed a new approach for synthesizing knowledge that seeks to unpack the mechanism of how “complex interventions” work in particular contexts. The basic research question — what works? — which is usually associated with systematic reviews changes to: what is it about this intervention that works, for whom, in what circumstances, in what respects and why? Realist reviews have no particular preference for either quantitative or qualitative evidence. As a theory-building approach, a realist review usually starts by articulating likely underlying mechanisms and then scrutinizes available evidence to find out whether and where these mechanisms are applicable ( Shepperd et al., 2009 ). Primary studies found in the extant literature are viewed as case studies which can test and modify the initial theories ( Rousseau et al., 2008 ).

The main objective pursued in the realist review conducted by Otte-Trojel, de Bont, Rundall, and van de Klundert (2014) was to examine how patient portals contribute to health service delivery and patient outcomes. The specific goals were to investigate how outcomes are produced and, most importantly, how variations in outcomes can be explained. The research team started with an exploratory review of background documents and research studies to identify ways in which patient portals may contribute to health service delivery and patient outcomes. The authors identified six main ways which represent “educated guesses” to be tested against the data in the evaluation studies. These studies were identified through a formal and systematic search in four databases between 2003 and 2013. Two members of the research team selected the articles using a pre-established list of inclusion and exclusion criteria and following a two-step procedure. The authors then extracted data from the selected articles and created several tables, one for each outcome category. They organized information to bring forward those mechanisms where patient portals contribute to outcomes and the variation in outcomes across different contexts.

9.3.6. Critical Reviews

Lastly, critical reviews aim to provide a critical evaluation and interpretive analysis of existing literature on a particular topic of interest to reveal strengths, weaknesses, contradictions, controversies, inconsistencies, and/or other important issues with respect to theories, hypotheses, research methods or results ( Baumeister & Leary, 1997 ; Kirkevold, 1997 ). Unlike other review types, critical reviews attempt to take a reflective account of the research that has been done in a particular area of interest, and assess its credibility by using appraisal instruments or critical interpretive methods. In this way, critical reviews attempt to constructively inform other scholars about the weaknesses of prior research and strengthen knowledge development by giving focus and direction to studies for further improvement ( Kirkevold, 1997 ).

Kitsiou, Paré, and Jaana (2013) provide an example of a critical review that assessed the methodological quality of prior systematic reviews of home telemonitoring studies for chronic patients. The authors conducted a comprehensive search on multiple databases to identify eligible reviews and subsequently used a validated instrument to conduct an in-depth quality appraisal. Results indicate that the majority of systematic reviews in this particular area suffer from important methodological flaws and biases that impair their internal validity and limit their usefulness for clinical and decision-making purposes. To this end, they provide a number of recommendations to strengthen knowledge development towards improving the design and execution of future reviews on home telemonitoring.

9.4. Summary

Table 9.1 outlines the main types of literature reviews that were described in the previous sub-sections and summarizes the main characteristics that distinguish one review type from another. It also includes key references to methodological guidelines and useful sources that can be used by eHealth scholars and researchers for planning and developing reviews.

Typology of Literature Reviews (adapted from Paré et al., 2015).

As shown in Table 9.1 , each review type addresses different kinds of research questions or objectives, which subsequently define and dictate the methods and approaches that need to be used to achieve the overarching goal(s) of the review. For example, in the case of narrative reviews, there is greater flexibility in searching and synthesizing articles ( Green et al., 2006 ). Researchers are often relatively free to use a diversity of approaches to search, identify, and select relevant scientific articles, describe their operational characteristics, present how the individual studies fit together, and formulate conclusions. On the other hand, systematic reviews are characterized by their high level of systematicity, rigour, and use of explicit methods, based on an “a priori” review plan that aims to minimize bias in the analysis and synthesis process (Higgins & Green, 2008). Some reviews are exploratory in nature (e.g., scoping/mapping reviews), whereas others may be conducted to discover patterns (e.g., descriptive reviews) or involve a synthesis approach that may include the critical analysis of prior research ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Hence, in order to select the most appropriate type of review, it is critical to know before embarking on a review project, why the research synthesis is conducted and what type of methods are best aligned with the pursued goals.

9.5. Concluding Remarks

In light of the increased use of evidence-based practice and research generating stronger evidence ( Grady et al., 2011 ; Lyden et al., 2013 ), review articles have become essential tools for summarizing, synthesizing, integrating or critically appraising prior knowledge in the eHealth field. As mentioned earlier, when rigorously conducted review articles represent powerful information sources for eHealth scholars and practitioners looking for state-of-the-art evidence. The typology of literature reviews we used herein will allow eHealth researchers, graduate students and practitioners to gain a better understanding of the similarities and differences between review types.

We must stress that this classification scheme does not privilege any specific type of review as being of higher quality than another ( Paré et al., 2015 ). As explained above, each type of review has its own strengths and limitations. Having said that, we realize that the methodological rigour of any review — be it qualitative, quantitative or mixed — is a critical aspect that should be considered seriously by prospective authors. In the present context, the notion of rigour refers to the reliability and validity of the review process described in section 9.2. For one thing, reliability is related to the reproducibility of the review process and steps, which is facilitated by a comprehensive documentation of the literature search process, extraction, coding and analysis performed in the review. Whether the search is comprehensive or not, whether it involves a methodical approach for data extraction and synthesis or not, it is important that the review documents in an explicit and transparent manner the steps and approach that were used in the process of its development. Next, validity characterizes the degree to which the review process was conducted appropriately. It goes beyond documentation and reflects decisions related to the selection of the sources, the search terms used, the period of time covered, the articles selected in the search, and the application of backward and forward searches ( vom Brocke et al., 2009 ). In short, the rigour of any review article is reflected by the explicitness of its methods (i.e., transparency) and the soundness of the approach used. We refer those interested in the concepts of rigour and quality to the work of Templier and Paré (2015) which offers a detailed set of methodological guidelines for conducting and evaluating various types of review articles.

To conclude, our main objective in this chapter was to demystify the various types of literature reviews that are central to the continuous development of the eHealth field. It is our hope that our descriptive account will serve as a valuable source for those conducting, evaluating or using reviews in this important and growing domain.

- Ammenwerth E., de Keizer N. An inventory of evaluation studies of information technology in health care. Trends in evaluation research, 1982-2002. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2004; 44 (1):44–56. [ PubMed : 15778794 ]