Research report guide: Definition, types, and tips

Last updated

5 March 2024

Reviewed by

From successful product launches or software releases to planning major business decisions, research reports serve many vital functions. They can summarize evidence and deliver insights and recommendations to save companies time and resources. They can reveal the most value-adding actions a company should take.

However, poorly constructed reports can have the opposite effect! Taking the time to learn established research-reporting rules and approaches will equip you with in-demand skills. You’ll be able to capture and communicate information applicable to numerous situations and industries, adding another string to your resume bow.

- What are research reports?

A research report is a collection of contextual data, gathered through organized research, that provides new insights into a particular challenge (which, for this article, is business-related). Research reports are a time-tested method for distilling large amounts of data into a narrow band of focus.

Their effectiveness often hinges on whether the report provides:

Strong, well-researched evidence

Comprehensive analysis

Well-considered conclusions and recommendations

Though the topic possibilities are endless, an effective research report keeps a laser-like focus on the specific questions or objectives the researcher believes are key to achieving success. Many research reports begin as research proposals, which usually include the need for a report to capture the findings of the study and recommend a course of action.

A description of the research method used, e.g., qualitative, quantitative, or other

Statistical analysis

Causal (or explanatory) research (i.e., research identifying relationships between two variables)

Inductive research, also known as ‘theory-building’

Deductive research, such as that used to test theories

Action research, where the research is actively used to drive change

- Importance of a research report

Research reports can unify and direct a company's focus toward the most appropriate strategic action. Of course, spending resources on a report takes up some of the company's human and financial resources. Choosing when a report is called for is a matter of judgment and experience.

Some development models used heavily in the engineering world, such as Waterfall development, are notorious for over-relying on research reports. With Waterfall development, there is a linear progression through each step of a project, and each stage is precisely documented and reported on before moving to the next.

The pace of the business world is faster than the speed at which your authors can produce and disseminate reports. So how do companies strike the right balance between creating and acting on research reports?

The answer lies, again, in the report's defined objectives. By paring down your most pressing interests and those of your stakeholders, your research and reporting skills will be the lenses that keep your company's priorities in constant focus.

Honing your company's primary objectives can save significant amounts of time and align research and reporting efforts with ever-greater precision.

Some examples of well-designed research objectives are:

Proving whether or not a product or service meets customer expectations

Demonstrating the value of a service, product, or business process to your stakeholders and investors

Improving business decision-making when faced with a lack of time or other constraints

Clarifying the relationship between a critical cause and effect for problematic business processes

Prioritizing the development of a backlog of products or product features

Comparing business or production strategies

Evaluating past decisions and predicting future outcomes

- Features of a research report

Research reports generally require a research design phase, where the report author(s) determine the most important elements the report must contain.

Just as there are various kinds of research, there are many types of reports.

Here are the standard elements of almost any research-reporting format:

Report summary. A broad but comprehensive overview of what readers will learn in the full report. Summaries are usually no more than one or two paragraphs and address all key elements of the report. Think of the key takeaways your primary stakeholders will want to know if they don’t have time to read the full document.

Introduction. Include a brief background of the topic, the type of research, and the research sample. Consider the primary goal of the report, who is most affected, and how far along the company is in meeting its objectives.

Methods. A description of how the researcher carried out data collection, analysis, and final interpretations of the data. Include the reasons for choosing a particular method. The methods section should strike a balance between clearly presenting the approach taken to gather data and discussing how it is designed to achieve the report's objectives.

Data analysis. This section contains interpretations that lead readers through the results relevant to the report's thesis. If there were unexpected results, include here a discussion on why that might be. Charts, calculations, statistics, and other supporting information also belong here (or, if lengthy, as an appendix). This should be the most detailed section of the research report, with references for further study. Present the information in a logical order, whether chronologically or in order of importance to the report's objectives.

Conclusion. This should be written with sound reasoning, often containing useful recommendations. The conclusion must be backed by a continuous thread of logic throughout the report.

- How to write a research paper

With a clear outline and robust pool of research, a research paper can start to write itself, but what's a good way to start a research report?

Research report examples are often the quickest way to gain inspiration for your report. Look for the types of research reports most relevant to your industry and consider which makes the most sense for your data and goals.

The research report outline will help you organize the elements of your report. One of the most time-tested report outlines is the IMRaD structure:

Introduction

...and Discussion

Pay close attention to the most well-established research reporting format in your industry, and consider your tone and language from your audience's perspective. Learn the key terms inside and out; incorrect jargon could easily harm the perceived authority of your research paper.

Along with a foundation in high-quality research and razor-sharp analysis, the most effective research reports will also demonstrate well-developed:

Internal logic

Narrative flow

Conclusions and recommendations

Readability, striking a balance between simple phrasing and technical insight

How to gather research data for your report

The validity of research data is critical. Because the research phase usually occurs well before the writing phase, you normally have plenty of time to vet your data.

However, research reports could involve ongoing research, where report authors (sometimes the researchers themselves) write portions of the report alongside ongoing research.

One such research-report example would be an R&D department that knows its primary stakeholders are eager to learn about a lengthy work in progress and any potentially important outcomes.

However you choose to manage the research and reporting, your data must meet robust quality standards before you can rely on it. Vet any research with the following questions in mind:

Does it use statistically valid analysis methods?

Do the researchers clearly explain their research, analysis, and sampling methods?

Did the researchers provide any caveats or advice on how to interpret their data?

Have you gathered the data yourself or were you in close contact with those who did?

Is the source biased?

Usually, flawed research methods become more apparent the further you get through a research report.

It's perfectly natural for good research to raise new questions, but the reader should have no uncertainty about what the data represents. There should be no doubt about matters such as:

Whether the sampling or analysis methods were based on sound and consistent logic

What the research samples are and where they came from

The accuracy of any statistical functions or equations

Validation of testing and measuring processes

When does a report require design validation?

A robust design validation process is often a gold standard in highly technical research reports. Design validation ensures the objects of a study are measured accurately, which lends more weight to your report and makes it valuable to more specialized industries.

Product development and engineering projects are the most common research-report examples that typically involve a design validation process. Depending on the scope and complexity of your research, you might face additional steps to validate your data and research procedures.

If you’re including design validation in the report (or report proposal), explain and justify your data-collection processes. Good design validation builds greater trust in a research report and lends more weight to its conclusions.

Choosing the right analysis method

Just as the quality of your report depends on properly validated research, a useful conclusion requires the most contextually relevant analysis method. This means comparing different statistical methods and choosing the one that makes the most sense for your research.

Most broadly, research analysis comes down to quantitative or qualitative methods (respectively: measurable by a number vs subjectively qualified values). There are also mixed research methods, which bridge the need for merging hard data with qualified assessments and still reach a cohesive set of conclusions.

Some of the most common analysis methods in research reports include:

Significance testing (aka hypothesis analysis), which compares test and control groups to determine how likely the data was the result of random chance.

Regression analysis , to establish relationships between variables, control for extraneous variables , and support correlation analysis.

Correlation analysis (aka bivariate testing), a method to identify and determine the strength of linear relationships between variables. It’s effective for detecting patterns from complex data, but care must be exercised to not confuse correlation with causation.

With any analysis method, it's important to justify which method you chose in the report. You should also provide estimates of the statistical accuracy (e.g., the p-value or confidence level of quantifiable data) of any data analysis.

This requires a commitment to the report's primary aim. For instance, this may be achieving a certain level of customer satisfaction by analyzing the cause and effect of changes to how service is delivered. Even better, use statistical analysis to calculate which change is most positively correlated with improved levels of customer satisfaction.

- Tips for writing research reports

There's endless good advice for writing effective research reports, and it almost all depends on the subjective aims of the people behind the report. Due to the wide variety of research reports, the best tips will be unique to each author's purpose.

Consider the following research report tips in any order, and take note of the ones most relevant to you:

No matter how in depth or detailed your report might be, provide a well-considered, succinct summary. At the very least, give your readers a quick and effective way to get up to speed.

Pare down your target audience (e.g., other researchers, employees, laypersons, etc.), and adjust your voice for their background knowledge and interest levels

For all but the most open-ended research, clarify your objectives, both for yourself and within the report.

Leverage your team members’ talents to fill in any knowledge gaps you might have. Your team is only as good as the sum of its parts.

Justify why your research proposal’s topic will endure long enough to derive value from the finished report.

Consolidate all research and analysis functions onto a single user-friendly platform. There's no reason to settle for less than developer-grade tools suitable for non-developers.

What's the format of a research report?

The research-reporting format is how the report is structured—a framework the authors use to organize their data, conclusions, arguments, and recommendations. The format heavily determines how the report's outline develops, because the format dictates the overall structure and order of information (based on the report's goals and research objectives).

What's the purpose of a research-report outline?

A good report outline gives form and substance to the report's objectives, presenting the results in a readable, engaging way. For any research-report format, the outline should create momentum along a chain of logic that builds up to a conclusion or interpretation.

What's the difference between a research essay and a research report?

There are several key differences between research reports and essays:

Research report:

Ordered into separate sections

More commercial in nature

Often includes infographics

Heavily descriptive

More self-referential

Usually provides recommendations

Research essay

Does not rely on research report formatting

More academically minded

Normally text-only

Less detailed

Omits discussion of methods

Usually non-prescriptive

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.2: Overview of the Research Process

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 26219

- Anol Bhattacherjee

- University of South Florida via Global Text Project

So how do our mental paradigms shape social science research? At its core, all scientific research is an iterative process of observation, rationalization, and validation. In the observation phase, we observe a natural or social phenomenon, event, or behavior that interests us. In the rationalization phase, we try to make sense of or the observed phenomenon, event, or behavior by logically connecting the different pieces of the puzzle that we observe, which in some cases, may lead to the construction of a theory. Finally, in the validation phase, we test our theories using a scientific method through a process of data collection and analysis, and in doing so, possibly modify or extend our initial theory. However, research designs vary based on whether the researcher starts at observation and attempts to rationalize the observations (inductive research), or whether the researcher starts at an ex ante rationalization or a theory and attempts to validate the theory (deductive research). Hence, the observation-rationalization-validation cycle is very similar to the induction-deduction cycle of research discussed in Chapter 1.

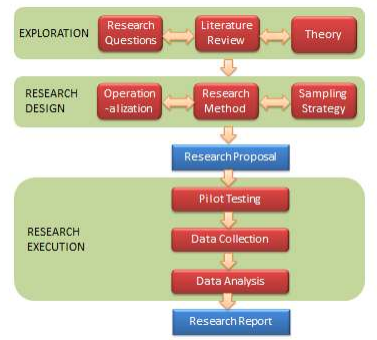

Most traditional research tends to be deductive and functionalistic in nature. Figure 3.2 provides a schematic view of such a research project. This figure depicts a series of activities to be performed in functionalist research, categorized into three phases: exploration, research design, and research execution. Note that this generalized design is not a roadmap or flowchart for all research. It applies only to functionalistic research, and it can and should be modified to fit the needs of a specific project.

The first phase of research is exploration . This phase includes exploring and selecting research questions for further investigation, examining the published literature in the area of inquiry to understand the current state of knowledge in that area, and identifying theories that may help answer the research questions of interest.

The first step in the exploration phase is identifying one or more research questions dealing with a specific behavior, event, or phenomena of interest. Research questions are specific questions about a behavior, event, or phenomena of interest that you wish to seek answers for in your research. Examples include what factors motivate consumers to purchase goods and services online without knowing the vendors of these goods or services, how can we make high school students more creative, and why do some people commit terrorist acts. Research questions can delve into issues of what, why, how, when, and so forth. More interesting research questions are those that appeal to a broader population (e.g., “how can firms innovate” is a more interesting research question than “how can Chinese firms innovate in the service-sector”), address real and complex problems (in contrast to hypothetical or “toy” problems), and where the answers are not obvious. Narrowly focused research questions (often with a binary yes/no answer) tend to be less useful and less interesting and less suited to capturing the subtle nuances of social phenomena. Uninteresting research questions generally lead to uninteresting and unpublishable research findings.

The next step is to conduct a literature review of the domain of interest. The purpose of a literature review is three-fold: (1) to survey the current state of knowledge in the area of inquiry, (2) to identify key authors, articles, theories, and findings in that area, and (3) to identify gaps in knowledge in that research area. Literature review is commonly done today using computerized keyword searches in online databases. Keywords can be combined using “and” and “or” operations to narrow down or expand the search results. Once a shortlist of relevant articles is generated from the keyword search, the researcher must then manually browse through each article, or at least its abstract section, to determine the suitability of that article for a detailed review. Literature reviews should be reasonably complete, and not restricted to a few journals, a few years, or a specific methodology. Reviewed articles may be summarized in the form of tables, and can be further structured using organizing frameworks such as a concept matrix. A well-conducted literature review should indicate whether the initial research questions have already been addressed in the literature (which would obviate the need to study them again), whether there are newer or more interesting research questions available, and whether the original research questions should be modified or changed in light of findings of the literature review. The review can also provide some intuitions or potential answers to the questions of interest and/or help identify theories that have previously been used to address similar questions.

Since functionalist (deductive) research involves theory-testing, the third step is to identify one or more theories can help address the desired research questions. While the literature review may uncover a wide range of concepts or constructs potentially related to the phenomenon of interest, a theory will help identify which of these constructs is logically relevant to the target phenomenon and how. Forgoing theories may result in measuring a wide range of less relevant, marginally relevant, or irrelevant constructs, while also minimizing the chances of obtaining results that are meaningful and not by pure chance. In functionalist research, theories can be used as the logical basis for postulating hypotheses for empirical testing. Obviously, not all theories are well-suited for studying all social phenomena. Theories must be carefully selected based on their fit with the target problem and the extent to which their assumptions are consistent with that of the target problem. We will examine theories and the process of theorizing in detail in the next chapter.

The next phase in the research process is research design . This process is concerned with creating a blueprint of the activities to take in order to satisfactorily answer the research questions identified in the exploration phase. This includes selecting a research method, operationalizing constructs of interest, and devising an appropriate sampling strategy.

Operationalization is the process of designing precise measures for abstract theoretical constructs. This is a major problem in social science research, given that many of the constructs, such as prejudice, alienation, and liberalism are hard to define, let alone measure accurately. Operationalization starts with specifying an “operational definition” (or “conceptualization”) of the constructs of interest. Next, the researcher can search the literature to see if there are existing prevalidated measures matching their operational definition that can be used directly or modified to measure their constructs of interest. If such measures are not available or if existing measures are poor or reflect a different conceptualization than that intended by the researcher, new instruments may have to be designed for measuring those constructs. This means specifying exactly how exactly the desired construct will be measured (e.g., how many items, what items, and so forth). This can easily be a long and laborious process, with multiple rounds of pretests and modifications before the newly designed instrument can be accepted as “scientifically valid.” We will discuss operationalization of constructs in a future chapter on measurement.

Simultaneously with operationalization, the researcher must also decide what research method they wish to employ for collecting data to address their research questions of interest. Such methods may include quantitative methods such as experiments or survey research or qualitative methods such as case research or action research, or possibly a combination of both. If an experiment is desired, then what is the experimental design? If survey, do you plan a mail survey, telephone survey, web survey, or a combination? For complex, uncertain, and multifaceted social phenomena, multi-method approaches may be more suitable, which may help leverage the unique strengths of each research method and generate insights that may not be obtained using a single method.

Researchers must also carefully choose the target population from which they wish to collect data, and a sampling strategy to select a sample from that population. For instance, should they survey individuals or firms or workgroups within firms? What types of individuals or firms they wish to target? Sampling strategy is closely related to the unit of analysis in a research problem. While selecting a sample, reasonable care should be taken to avoid a biased sample (e.g., sample based on convenience) that may generate biased observations. Sampling is covered in depth in a later chapter.

At this stage, it is often a good idea to write a research proposal detailing all of the decisions made in the preceding stages of the research process and the rationale behind each decision. This multi-part proposal should address what research questions you wish to study and why, the prior state of knowledge in this area, theories you wish to employ along with hypotheses to be tested, how to measure constructs, what research method to be employed and why, and desired sampling strategy. Funding agencies typically require such a proposal in order to select the best proposals for funding. Even if funding is not sought for a research project, a proposal may serve as a useful vehicle for seeking feedback from other researchers and identifying potential problems with the research project (e.g., whether some important constructs were missing from the study) before starting data collection. This initial feedback is invaluable because it is often too late to correct critical problems after data is collected in a research study.

Having decided who to study (subjects), what to measure (concepts), and how to collect data (research method), the researcher is now ready to proceed to the research execution phase. This includes pilot testing the measurement instruments, data collection, and data analysis.

Pilot testing is an often overlooked but extremely important part of the research process. It helps detect potential problems in your research design and/or instrumentation (e.g., whether the questions asked is intelligible to the targeted sample), and to ensure that the measurement instruments used in the study are reliable and valid measures of the constructs of interest. The pilot sample is usually a small subset of the target population. After a successful pilot testing, the researcher may then proceed with data collection using the sampled population. The data collected may be quantitative or qualitative, depending on the research method employed.

Following data collection, the data is analyzed and interpreted for the purpose of drawing conclusions regarding the research questions of interest. Depending on the type of data collected (quantitative or qualitative), data analysis may be quantitative (e.g., employ statistical techniques such as regression or structural equation modeling) or qualitative (e.g., coding or content analysis).

The final phase of research involves preparing the final research report documenting the entire research process and its findings in the form of a research paper, dissertation, or monograph. This report should outline in detail all the choices made during the research process (e.g., theory used, constructs selected, measures used, research methods, sampling, etc.) and why, as well as the outcomes of each phase of the research process. The research process must be described in sufficient detail so as to allow other researchers to replicate your study, test the findings, or assess whether the inferences derived are scientifically acceptable. Of course, having a ready research proposal will greatly simplify and quicken the process of writing the finished report. Note that research is of no value unless the research process and outcomes are documented for future generations; such documentation is essential for the incremental progress of science.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Section 1- Evidence-based practice (EBP)

Chapter 6: Components of a Research Report

Components of a research report.

Partido, B.B.

Elements of research report

The research report contains four main areas:

- Introduction – What is the issue? What is known? What is not known? What are you trying to find out? This sections ends with the purpose and specific aims of the study.

- Methods – The recipe for the study. If someone wanted to perform the same study, what information would they need? How will you answer your research question? This part usually contains subheadings: Participants, Instruments, Procedures, Data Analysis,

- Results – What was found? This is organized by specific aims and provides the results of the statistical analysis.

- Discussion – How do the results fit in with the existing literature? What were the limitations and areas of future research?

Formalized Curiosity for Knowledge and Innovation Copyright © by partido1. All Rights Reserved.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

A Beginner's Guide to Starting the Research Process

When you have to write a thesis or dissertation , it can be hard to know where to begin, but there are some clear steps you can follow.

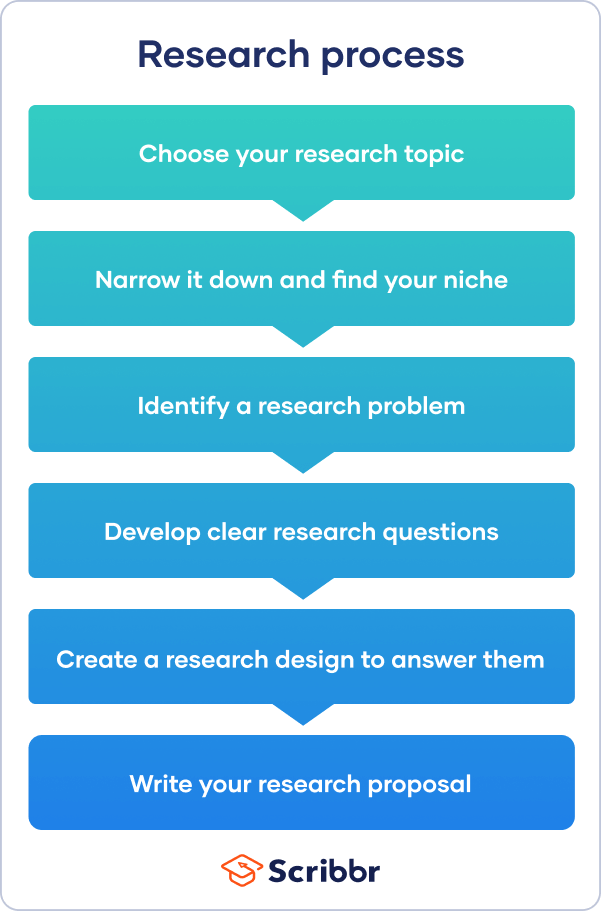

The research process often begins with a very broad idea for a topic you’d like to know more about. You do some preliminary research to identify a problem . After refining your research questions , you can lay out the foundations of your research design , leading to a proposal that outlines your ideas and plans.

This article takes you through the first steps of the research process, helping you narrow down your ideas and build up a strong foundation for your research project.

Table of contents

Step 1: choose your topic, step 2: identify a problem, step 3: formulate research questions, step 4: create a research design, step 5: write a research proposal, other interesting articles.

First you have to come up with some ideas. Your thesis or dissertation topic can start out very broad. Think about the general area or field you’re interested in—maybe you already have specific research interests based on classes you’ve taken, or maybe you had to consider your topic when applying to graduate school and writing a statement of purpose .

Even if you already have a good sense of your topic, you’ll need to read widely to build background knowledge and begin narrowing down your ideas. Conduct an initial literature review to begin gathering relevant sources. As you read, take notes and try to identify problems, questions, debates, contradictions and gaps. Your aim is to narrow down from a broad area of interest to a specific niche.

Make sure to consider the practicalities: the requirements of your programme, the amount of time you have to complete the research, and how difficult it will be to access sources and data on the topic. Before moving onto the next stage, it’s a good idea to discuss the topic with your thesis supervisor.

>>Read more about narrowing down a research topic

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

So you’ve settled on a topic and found a niche—but what exactly will your research investigate, and why does it matter? To give your project focus and purpose, you have to define a research problem .

The problem might be a practical issue—for example, a process or practice that isn’t working well, an area of concern in an organization’s performance, or a difficulty faced by a specific group of people in society.

Alternatively, you might choose to investigate a theoretical problem—for example, an underexplored phenomenon or relationship, a contradiction between different models or theories, or an unresolved debate among scholars.

To put the problem in context and set your objectives, you can write a problem statement . This describes who the problem affects, why research is needed, and how your research project will contribute to solving it.

>>Read more about defining a research problem

Next, based on the problem statement, you need to write one or more research questions . These target exactly what you want to find out. They might focus on describing, comparing, evaluating, or explaining the research problem.

A strong research question should be specific enough that you can answer it thoroughly using appropriate qualitative or quantitative research methods. It should also be complex enough to require in-depth investigation, analysis, and argument. Questions that can be answered with “yes/no” or with easily available facts are not complex enough for a thesis or dissertation.

In some types of research, at this stage you might also have to develop a conceptual framework and testable hypotheses .

>>See research question examples

The research design is a practical framework for answering your research questions. It involves making decisions about the type of data you need, the methods you’ll use to collect and analyze it, and the location and timescale of your research.

There are often many possible paths you can take to answering your questions. The decisions you make will partly be based on your priorities. For example, do you want to determine causes and effects, draw generalizable conclusions, or understand the details of a specific context?

You need to decide whether you will use primary or secondary data and qualitative or quantitative methods . You also need to determine the specific tools, procedures, and materials you’ll use to collect and analyze your data, as well as your criteria for selecting participants or sources.

>>Read more about creating a research design

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Finally, after completing these steps, you are ready to complete a research proposal . The proposal outlines the context, relevance, purpose, and plan of your research.

As well as outlining the background, problem statement, and research questions, the proposal should also include a literature review that shows how your project will fit into existing work on the topic. The research design section describes your approach and explains exactly what you will do.

You might have to get the proposal approved by your supervisor before you get started, and it will guide the process of writing your thesis or dissertation.

>>Read more about writing a research proposal

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

More interesting articles

- 10 Research Question Examples to Guide Your Research Project

- How to Choose a Dissertation Topic | 8 Steps to Follow

- How to Define a Research Problem | Ideas & Examples

- How to Write a Problem Statement | Guide & Examples

- Relevance of Your Dissertation Topic | Criteria & Tips

- Research Objectives | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Fishbone Diagram? | Templates & Examples

- What Is Root Cause Analysis? | Definition & Examples

What is your plagiarism score?

Research process. Reporting results of the research

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Family Medicine, Ohio State University, Columbus 43210.

- PMID: 1999805

- DOI: 10.7547/87507315-81-2-93

The preparation of a manuscript to report a research project is the final stage of the research process. Recommendations are made in this article related to preparing to write, getting started, guarding against problems and frustrations by making early decisions, and developing each component of the manuscript. This article is the last in a series of six on the research process, in which the collective purpose has been to offer guidance regarding the spectrum of skills required to produce quality research reports.

- Manuscripts as Topic

- Publishing*

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: Comprehensive Search

- Get Started

- Exploratory Search

- Where to Search

- How to Search

Grey Literature

- What about errata and retractions?

- Eligibility Screening

- Critical Appraisal

- Data Extraction

- Synthesis & Discussion

- Assess Certainty

- Share & Archive

A comprehensive search is a systematic effort to find all available evidence to answer your specific question(s).

The validity and usefulness of a synthesis hinges, in part, on a high-quality comprehensive search. Like all the other stages of a systematic review and/or meta-analysis, the process itself should be replicable .

We cover this content across four subtabs:

(A) Where to Search | (B) How to Search | (C) Grey Literature | (D) What about errata and retractions?

Reporting Guideline for Searching

PRISMA-S is a reporting guideline for the search strategy . It should be used in conjunction with a systematic review and/or meta-analysis reporting guideline (e.g., PRISMA). Using this guideline will help you ensure "each component of a search is completely reported and...reproducible".

This section of our Library Guide is informed by the PRISMA-S Reporting Guideline.

Overview of Comprehensive Searching

What are you searching for.

First identify the type of material that can answer your question - this may already be part of your eligibility criteria . For most research questions, you will likely need at least peer-reviewed empirical research.

Peer-Reviewed Empirical Research

In some cases, it may make sense to only include peer-reviewed research, or even a specific type of research like randomized controlled trials. Peer-reviewed research should be located systematically so that the search is replicable and comprehensiveness can be reasonably justified. Therefore, a comprehensive search for peer-reviewed literature takes place primarily in academic journal databases. The where and how to search sections of this guide are primarily focused on searching in academic databases to find peer-reviewed research.

In other cases, grey literature may be required to properly answer a question. Grey literature is a broad term that varies across discipline . Some common examples of grey literature include unpublished research, conference proceedings, government publications, social media content, blogs, newspapers, datasets, etc. Grey literature can rudimentarily be defined as anything that is not peer-reviewed, empirical research .

Because of this variation, finding grey lit in a systematic, transparent, and replicable manner can be challenging. Where you search will vary based on what kind of grey lit you're looking for - how you search will vary based on the options available within the interface or database. However, it is important to document your search terms and process to be as systematic, transparent, and replicable as possible.

Where to search?

Once you've identified what kind of material you're looking for, you can identify where to search. This will include academic journal databases at a minimum. Check out the Where to search tab for more!

How to search?

The design of your search strategy will depend on what you're looking for and where you're looking. Check out the How to search tab for more!

Methodological Guidance

- Health Sciences

- Animal, Food Sciences

- Social Sciences

- Environmental Sciences

Cochrane Handbook - Part 2: Core Methods

Chapter 4: Searching and Selecting Studies provides guidance for both the search and screening/review (link)

- 4.2.1 Role of information specialist/librarian

- 4.2.2 Minimizing bias

- 4.2.3 Studies versus reports of studies

- 4.3.1 Bibliographic databases

- 4.3.2 Ongoing studies and unpublished data sources

- 4.3.3 Trials registers and trials results registers

- 4.3.4 Regulatory agency sources and clinical study reports

- 4.3.5 Other sources

- 4.4.1 Introduction to search strategies

- 4.4.2 Structure of a search strategy

- 4.4.3 Sensitivity versus precision

- 4.4.4 Controlled vocabulary and text words

- 4.4.5 Language , date , and document format

- 4.4.7 Search filters

- 4.4.6 Identifying fraudulent studies, other retracted publications, errata , and comments

- 4.4.8 Peer review of search strategies

- 4.4.9 Alerts

- 4.4.10 Timing of searches

- 4.4.11 When to stop searching

- 4.5 Documenting and reporting the search process

SYREAF Protocols

Step 2: conducting a search.

Conducting systematic reviews of intervention questions I: Writing the review protocol, formulating the question and searching the literature. O’Connor AM, Anderson KM, Goodell CK, Sargeant JM. Zoonoses Public Health. 2014 Jun;61 Suppl 1:28-38. doi: 10.1111/zph.12125. PMID: 24905994

Technical Manual for Performing Electronic Literature Searches in Food and Feed Safety.

Campbell - MECCIR

C19 + C24. Planning the search ( protocol )

C25. Searching specialist bibliographic databases ( protocol )

C26. Searching for different types of evidence ( protocol )

C27. Searching trials registers ( protocol )

C28. Searching for grey literature ( protocol )

C29. Searching within other reviews ( protocol )

C30. Searching reference lists ( protocol )

C31. Searching by contacting relevant individuals and organizations ( protocol )

C32 Structuring search strategies for bibliographic databases ( review / final manuscript )

C33. Developing search strategies for bibliographic databases ( review / final manuscript )

C34. Using search filters ( review / final manuscript )

C35. Restricting database searches ( protocol & review / final manuscript )

C36. Documenting the search process ( review / final manuscript )

C37. Rerunning searches ( review / final manuscript )

C38. Incorporating findings from rerun searches ( review / final manuscript )

C48. Obtaining unpublished data ( protocol & review / final manuscript )

" Searching for Studies ", the Campbell information retrieval guide

CEE - Guidelines and Standards for Evidence synthesis in Environmental Management

Section 5. conducting a search.

Key CEE Standards for Conduct and Reporting

5.2 Conducting the Search

5.3 Managing References and Recording the Search

5.4 Updating and Amending Searches

Reporting in Protocol and Final Manuscript

- Final Manuscript

In the Protocol | PRISMA-P

Describe all intended information sources (item 9).

...such as electronic databases, contact with study authors, trial registers or other grey literature sources...with planned dates of coverage

Present draft of search strategy (Item 10)

Having a search strategy peer reviewed may help to increase its comprehensiveness or decrease yield where search terminology is unnecessarily broad.

In the Final Manuscript | PRISMA

Information sources (item 6), essential items:.

- Specify the date when each source (such as database, register, website, organisation) was last searched or consulted.

- If bibliographic databases were searched, specify for each database its name (such as MEDLINE, CINAHL), the interface or platform through which the database was searched (such as Ovid, EBSCOhost), and the dates of coverage (where this information is provided).

- If study registers (such as ClinicalTrials.gov), regulatory databases (such as Drugs@FDA), and other online repositories (such as SIDER Side Effect Resource) were searched, specify the name of each source and any date restrictions that were applied.

- If websites , search engines , or other online sources were browsed or searched , specify the name and URL (uniform resource locator) of each source.

- If organisations or manufacturers were contacted to identify studies, specify the name of each source.

- If individuals were contacted to identify studies, specify the types of individuals contacted (such as authors of studies included in the review or researchers with expertise in the area).

- If reference lists were examined, specify the types of references examined (such as references cited in study reports included in the systematic review, or references cited in systematic review reports on the same or a similar topic).

- If cited or citing reference searched (also called backwards and forward citation searching) were conducted, specify the bibliographic details of the reports to which citation searching was applied, the citation index or platform used (such as Web of Science), and the date the citation searching was done.

- If journals or conference proceedings were consulted, specify the names of each source, the dates covered and how they were searched (such as handsearching or browsing online).

Present the full search strategies (Item 7)

- Provide the full line by line search strategy as run in each database with a sophisticated interface (such as Ovid), or the sequence of terms that were used to search simpler interfaces, such as search engines or websites.

- Describe any limits applied to the search strategy (such as date or language) and justify these by linking back to the review’s eligibility criteria.

- If published approaches such as search filters designed to retrieve specific types of records (for example, filter for randomised trials) or search strategies from other systematic reviews , were used, cite them. If published approaches were adapted —for example, if existing search filters were amended— note the changes made .

- If natural language processing or text frequency analysis tools were used to identify or refine keywords, synonyms, or subject indexing terms to use in the search strategy, specify the tool(s) used.

- If a tool was used to automatically translate search strings for one database to another, specify the tool used.

- If the search strategy was validated —for example, by evaluating whether it could identify a set of clearly eligible studies—report the validation process used and specify which studies were included in the validation set.

- If the search strategy was peer reviewed , report the peer review process used and specify any tool used, such as the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) checklist.

- If the search strategy structure adopted was not based on a PICO-style approach, describe the final conceptual structure and any explorations that were undertaken to achieve it (for example, use of a multi-faceted approach that uses a series of searches, with different combinations of concepts, to capture a complex research question, or use of a variety of different search approaches to compensate for when a specific concept is difficult to define).

Database Name (Item 1)

Name each individual database searched, stating the platform for each...There is no single database that is able to provide a complete and accurate list of all studies...

Multi-Database Searching (Item 2)

If databases were searched simultaneously on a single platform, state the name of the platform, listing all of the databases searched...

Study Registries (Item 3)

List any study registries searched...study registries allow researchers to locate ongoing clinical trials and studies that may have gone unpublished

Online Resources and Browsing (Item 4)

Describe any online or print source purposefully searched or browsed (e.g., tables of contents, print conference proceedings, web sites), and how this was done...

Web search engines and specific websites

"... l ist all websites searched, along with their corresponding web address ...if authors used a general search engine , authors should declare whether steps were taken to reduce personalization bias ...if review teams choose to review a limited set of results , it should be noted in the text, along with the rationale..."

Conference proceedings:

"...authors must specify the conference names , the dates of conferences included, and the method used to search the proceedings (i.e., browsing print abstract books or using an online source)..."

General browsing:

"When purposefully browsing, describe any method used , the name of the journal or other source, and the time frame covered by the search, if applicable..."

Citation Searching (Item 5)

...can be complicated to describe, but the explanation should clearly state the database used...and describe any other methods used. Authors also must cite the “base” article(s) that citation searching was performed upon, either for examining cited or citing articles...

Personal Contact (Item 6)

Contact methods may vary widely ...may include personal contact, web forms, email mailing lists, mailed letters, social media contacts, or other methods...[which are] inherently difficult to reproduce , [so] researchers should attempt to give as much detail as possible ...

Other Methods (Item 7)

... declare that the method was used , even if it may not be fully replicable...[include] other additional information sources or search methods used in the methods section and in any supplementary materials...

Full Search Strategies (Item 8)

It is important to document and report the search strategy exactly as run , typically by copying and pasting the search strategy directly as entered into the search platform...repeat the database or resource name , database platform or web address , and other details necessary to clearly describe the resource....Report the full search strategy in supplementary materials as described above. Describe and link to the location of the supplementary materials in the methods section.

Limits and Restrictions (Item 9)

...report any limits or restrictions used or that no limits were used in the abstract, methods section, and in any supplementary materials, including the full search strategies (Item 8)...[and] the justification for any limits used...

Search Filters (Item 10)

...cite any search filter used in the methods section and describe adaptations made to any filter. Include the copied and pasted details of any search filter used or adapted for use as part of the full search strategy (Item 8)...

Prior Work (Item 11)

Sometimes, authors adapt or reuse [previously published search strategies] for different systematic reviews...it is appropriate to cite the original publication(s) consulted.

Updates (Item 12)

If there are no changes in information sources and/or search syntax (Table 2 ), it is sufficient to indicate the date the last search was run in the methods section and in the supplementary materials. If there are any changes in information sources and/or search syntax, the changes should be indicated (e.g., different set of databases, changes in search syntax, date restrictions) in the methods section... explain why these changes were made... If authors use email alerts or other methods to update searches, these methods can be briefly described by indicating the method used , the frequency of any updates, the name of the database(s) used ...Report the methods used to update the searches in the methods section and the supplementary materials, as described above.

Dates of Searches (Item 13)

... date of the last search of the primary information sources used...the time frame during which searches were conducted...the initial and/or last update search date with each complete search strategy in the supplementary materials...

Peer Review (Item 14)

Describe the use of peer review in the methods section.

Total Records (Item 15)

...report the total number of references retrieved from all sources, including updates...[such that] if a reader tries to duplicate a search from a systematic review, one would expect to retrieve nearly the same results when limiting to the timeframe in the original review...

Deduplication (Item 16)

...describe [the method] and cite any software or technique used...if duplicates were removed manually , authors should include a description ...

In the PRISMA Flowchart

Search Summary Table

In addition to the items required by PRISMA and PRISMA-S, Bethel, Rogers, and Abbot (2021) recommend including a search summary table "containing the details of which databases were searched , which supplementary search methods were used, and where the included articles were found."

[Bethel, Rogers, and Abbot (2021) Search Summary Table Template ]

We host two workshops each fall on advanced and comprehensive searching approaches, check out our latest recordings !

- << Previous: Protocol

- Next: Where to Search >>

- Last Updated: Apr 12, 2024 12:41 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.vt.edu/SRMA

Introduction to Systematic Reviews

In this guide.

- Introduction

- Lane Research Services

- Types of Reviews

- Systematic Review Process

- Protocols & Guidelines

- Data Extraction and Screening

- Resources & Tools

- Systematic Review Online Course

What is a Systematic Review?

Knowledge synthesis is a term used to describe the method of synthesizing results from individual studies and interpreting these results within the larger body of knowledge on the topic. It requires highly structured, transparent and reproducible methods using quantitative and/or qualitative evidence. Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, scoping reviews, rapid reviews, narrative syntheses, practice guidelines, among others, are all forms of knowledge syntheses. For more information on types of reviews, visit the "Types of Reviews" tab on the left.

A systematic review varies from an ordinary literature review in that it uses a comprehensive, methodical, transparent and reproducible search strategy to ensure conclusions are as unbiased and closer to the truth as possible. The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions defines a systematic review as:

"A systematic review attempts to identify, appraise and synthesize all the empirical evidence that meets pre-specified eligibility criteria to answer a given research question. Researchers conducting systematic reviews use explicit methods aimed at minimizing bias, in order to produce more reliable findings that can be used to inform decision making [...] This involves: the a priori specification of a research question; clarity on the scope of the review and which studies are eligible for inclusion; making every effort to find all relevant research and to ensure that issues of bias in included studies are accounted for; and analysing the included studies in order to draw conclusions based on all the identified research in an impartial and objective way." ( Chapter 1: Starting a review )

What are systematic reviews? from Cochrane on Youtube .

- Next: Lane Research Services >>

- Last Updated: Nov 1, 2023 2:50 PM

- URL: https://laneguides.stanford.edu/systematicreviews

- Open access

- Published: 30 July 2022

Paper 4: a review of reporting and disseminating approaches for rapid reviews in health policy and systems research

- Shannon E. Kelly ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5520-6095 1 , 2 ,

- Jessie McGowan 1 ,

- Kim Barnhardt 3 &

- Sharon E. Straus 4

Systematic Reviews volume 11 , Article number: 152 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

2659 Accesses

3 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Transparent reporting of rapid reviews enables appropriate use of research findings and dissemination strategies can strengthen uptake and impact for the targeted knowledge users, including policy-makers and health system managers. The aim of this literature review was to understand reporting and dissemination approaches for rapid reviews and provide an overview in the context of health policy and systems research.

A literature review and descriptive summary of the reporting and disseminating approaches for rapid reviews was conducted, focusing on available guidance and methods, considerations for engagement with knowledge users, and optimizing dissemination. MEDLINE, PubMed, Google scholar, as well as relevant websites and reference lists were searched from January 2017 to March 2021 to identify the relevant literature with no language restrictions. Content was abstracted and charted.

The literature review found limited guidance specific to rapid reviews. Building on the barriers and facilitators to systematic review use, we provide practical recommendations on different approaches and methods for reporting and disseminating expedited knowledge synthesis considering the needs of health policy and systems knowledge users. Reporting should balance comprehensive accounting of the research process and findings with what is “good enough” or sufficient to meet the requirements of the knowledge users, while considering the time and resources available to conduct a review. Typical approaches may be used when planning the dissemination of rapid review findings; such as peer-reviewed publications or symposia and clear and ongoing engagement with knowledge users in crafting the messages is essential so they are appropriately tailored to the target audience. Consideration should be given to providing different products for different audiences. Dissemination measures and bibliometrics are also useful to gauge impact and reach.

Conclusions

Limited guidance specific to the reporting and dissemination of rapid reviews is available. Although approaches to expedited synthesis for health policy and systems research vary, considerations for the reporting and dissemination of findings are pertinent to all.

Peer Review reports

A systematic review uses explicit and systematic methods to identify, select, critically appraise, and extract and analyze data from relevant research [ 1 ]. However, this is not always possible, and the need for timely evidence syntheses often necessitates the use of methodological compromises. Rapid review is a type of knowledge synthesis with similar components to the systematic review process but uses simplified methods and an accelerated approach to produce information to meet this need for timeliness [ 2 ]. These changes in a rapid evidence product may differ according to the needs of the end-user, the producer, and other variables. For research to be valuable to knowledge users (i.e., individuals who may use review findings to make a decision), it must be reported clearly and transparently. Given the methodological tailoring of rapid reviews, which helps to expedite the review timeline, it is important that reporting reflect protocol-driven decisions, processes, and findings. This enables uptake and appropriate use of research findings across a variety of knowledge users [ 3 ].

Rapid reviews are often requested or commissioned directly by health system decision-makers, a feature, which strengthens their usability to influence local health systems by directly addressing and informing urgent policy issues or questions [ 4 , 5 ]. Findings from rapid reviews are often contextualized to a particular health system setting in response to objectives specified by a knowledge-user, which increases usefulness for decision-making. Although approaches to rapid review for health policy and systems research may vary, the general considerations for reporting and disseminating evidence syntheses findings likely apply to all [ 5 ]. These considerations may also reflect the range of ways that individuals prefer to consume knowledge, from detailed reports to higher level briefs or plain language summaries.

Reporting is an important part of research synthesis. Guidance can be found from the Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research (EQUATOR) Network [ 6 ], who maintain a collection of up-to-date reporting tools and information to support the reporting guidelines to improve the quality of research publications. However, reporting is often done poorly or inadequately [ 7 ]. There is evidence that evidence syntheses fail to consider the needs of end-users or fail to provide enough detail to allow stakeholders to determine whether the findings are meaningful or trustworthy [ 7 , 8 ]. Similarly, one of the most challenging tasks facing evidence producers is translating research findings into accepted practice, which requires tailored dissemination and adoption, and often considerable effort [ 9 ]. Dissemination involves communicating research results for a specific or targeted audience, with the goal of maximizing both uptake and impact [ 3 ]. Although strides have been made in enhancing researchers’ understanding of the importance of dissemination and effective dissemination strategies, there has been limited research on the impact of various strategies [ 10 ]. The aim of this literature review was to summarize reporting and dissemination approaches specific to rapid reviews and to provide an overview in the context of health policy and systems research.

We conducted a broad literature review to describe current knowledge available to inform reporting and disseminating approaches for rapid reviews. Although this is not a systematic review, the general overview of our methods process supports good practice and transparency.

Eligibility criteria

We defined a rapid review as a knowledge synthesis product that uses components from the systematic review process which are simplified or omitted to produce information in a short period of time [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. We included peer-reviewed and agency-produced publications focused on or addressing reporting and disseminating approaches for rapid evidence products.

Information sources and search strategy

We searched PubMed, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar (first 100 records) using keywords (e.g., rapid review, expedited synthesis, time factors) broadly representing the range of nomenclature associated with rapid evidence products [ 2 , 14 ]. Any study design, including other narrative or descriptive articles, were considered. Other relevant literature was identified by searching the reference lists of key rapid review literature [ 2 , 11 , 12 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Websites of known rapid review producers [ 15 , 17 ] identified in these publications were also consulted. No language restrictions were applied. Searches were originally conducted in January 2017 and were updated in July 2019 and March 2021. All retrieved records were screened by a single reviewer (SK).

Data elements and charting process

Salient content relevant to the reporting or dissemination of rapid reviews were captured and entered in Microsoft Excel by a single reviewer (SK) and discussed with the other reviewers.

Data synthesis

We descriptively summarized results while focusing on health policy and systems research to capture available guidance and methods, and considerations for engagement with knowledge users.

Several peer-reviewed articles relevant to rapid review which were located and examined for content relevant to reporting and dissemination or application to health policy and systems research [ 4 , 5 , 8 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. In these records, we found limited guidance specific to rapid review reporting and dissemination; therefore, we used our existing knowledge and experience of known barriers and facilitators to systematic review use [ 27 ] to suggest key elements of format and content to consider when drafting a rapid review report [ 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ]. Similarly, few articles directly addressed the dissemination of rapid evidence products. As such, we describe and discuss typical approaches for planning the dissemination of research using a rapid review lens [ 3 , 10 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ].

Goals of research reporting and dissemination

Clear, complete, and transparent reporting supports and encourages constructive and useful uptake of any research product [ 33 ]. For evidence syntheses, including rapid reviews, reporting enables and promotes understanding of research results and contributes to the appropriate use of research findings by a variety of knowledge users, including policy-makers and health system administrators [ 7 ]. Given the methodological tailoring of rapid reviews often employed by evidence producers to shorten the review timeline, it is important that reporting accounts for all protocol-driven decisions, processes, and findings, which may influence their interpretation [ 14 ].

Research results should be communicated and presented through a planned and tailored dissemination process [ 40 ]. Consideration should be given to the wider settings where the research will be received and to the target audiences, with the overall goal of supporting and maximizing both uptake and impact [ 18 ]. Dissemination activities and tools are customized by considering the significance of the findings, dissemination goals, target audiences, and anticipated impact or influence of the rapid review. In particular, an intersectionality lens should be used when developing the dissemination approach from engagement of the relevant audiences through to development of key messages and delivery strategies [ 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 ]. Intersectionality explores the social factors (e.g., age, education, gender identity) and their interaction with compounding power structures (e.g., education systems) and forms of discrimination (e.g., racism, ageism).

Guidance and methods for reporting rapid reviews

Core principles of reporting knowledge syntheses.

Inadequate or unclear reporting can potentially reduce the utility of a knowledge synthesis product if the knowledge users do not have enough information to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the synthesis process and/or the results [ 28 ]. Regardless of methods used for a rapid review, maintaining research integrity depends upon a few core principles to guide the processes of conducting the review and preparing its report [ 4 ]. Knowledge users are interested in both the findings of the review and its methods. Like other knowledge synthesis approaches, authors must limit reporting bias, by ensuring the protocol and any amendments are included in the final report [ 29 , 30 ]. In general, authors of a rapid review should follow a few core principles (Table 1 ): work from a protocol, use clear language , focus on reproducibility , and summarize strengths and weaknesses of the approach , take knowledge user needs into consideration. If these basic principles are not adhered to, the knowledge user may lack adequate information to determine the reliability or validity of the review as a guide to decision-making. When methods are not described in acceptable detail, or when study findings are presented vaguely, selectively, and/or incompletely, the findings may be unusable [ 33 ]. This is wasteful for both the evidence producer and the knowledge user, and the health system, from a resource perspective [ 7 ]. Where an organization follows a common methodological approach for a suite of offered rapid evidence products, standardized methods may not always be fully reported in report; however, links to methodological documentation should be provided [ 20 ].

Rapid reviews are frequently commissioned by a knowledge user to inform a specific decision [ 11 , 25 ]. Therefore, understanding the reporting requirements of the knowledge user is essential to tailor the rapid review to the knowledge users needed. The knowledge user is likely to be an integral part of the research process, from defining the scope and setting the research question to finalizing the results. As such, they should also be included in the reporting process. Time spent discussing reporting requirements and expectations in advance will help to limit the time required for subsequent revisions and increase utility of the final report. The rapid review report should be tailored to the needs of the knowledge users, while balancing timelines and available resources. Reporting should balance comprehensive accounting of the research process and findings with what is “good enough” or sufficient to meet the requirements of the knowledge users (and/or other stakeholders if important) [ 12 ].

Special considerations for rapid reviews of health policy and systems research

Health policy and systems research often involves the assessment of complex interventions. Rapid reviews in this field may describe multifaceted or context-specific interventions that may be investigated through a variety of study designs (e.g., controlled before-and-after, interrupted time series, qualitative, or mixed methods studies) [ 5 ]. This complexity, and any difficulties encountered during the review process as a result, must be carefully described in the research report, keeping in mind that a wide variety of stakeholders may be interested in the results.

Strategies for reporting rapid evidence products have not been evaluated in comparative studies [ 5 ]. As with any knowledge synthesis, reporting for rapid reviews of health policy and systems research should be as comprehensive as possible within the time frame for review completion [ 12 , 14 ].

Reporting checklists and guidelines

Reporting guidelines exist to ensure that research reports contain enough information about the work to make it usable, appraisable, and replicable [ 28 ]. Reporting of the rapid review approach and tailoring of the methodology are often inadequate [ 2 , 14 , 17 ]. Details on knowledge user involvement are reported in less than 50% of reports [ 25 ]. A detailed assessment of the reporting quality of published rapid reviews, using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement, also found the reporting to be of poor quality across the included rapid reviews [ 14 ]. This assessment found that key decisions in review process and conduct are often presented with insufficient detail or omitted completely. Several publications have noted gaps in the reporting of essential methodological items. For example, many rapid reviews fail to mention the use of a protocol [ 2 ], which conflicts with a report that over 90% of organizations producing rapid reviews write and use a protocol [ 17 ]. Reporting is often brief or truncated, and methods may be reported in documentation separate from the rapid review report itself [ 20 ]. Other items noted in the literature as being poorly reported are the study screening and data collection processes, definitions of study eligibility, methods of assessing risk of bias in or across studies, processes used for syntheses, and limitations in the review process [ 14 ].

The literature search located only one tool that provides any reporting guidance specific to rapid reviews: a checklist presented developed by Abrami and colleagues [ 18 ]. This checklist reminds authors to provide explanations in key decision areas, and recommends reporting the research question, inclusion criteria, search strategies, inter-rater agreement (if applicable during study identification, calculation of effects, and/or coding of study features), outcome extraction, study features, analysis, interpretation and implications, cautions and limitations, and conclusions. However, the checklist omits several key areas that are worth noting: use of a protocol, inclusion of a structured abstract, explicit identification of the report as a rapid review, internal or external peer review of the review, and critical appraisal of the information included in the review and the types of information sought (e.g., reviews, quantitative or qualitative studies, or other types of research).

To ensure that reporting is complete and transparent, future exploration of reporting (and conduct) guidelines specific to rapid reviews is warranted. Other guidelines and checklists are relevant to rapid reviews, although they focus on the reporting of systematic reviews, such as the PRISMA statement [ 29 , 47 ]. An extension to PRISMA specific to rapid reviews is currently under development [ 19 ]. As there is only a brief published protocol available to-date, it remains unclear if the PRISMA extension for rapid reviews provide guidance specific to health policy and systems reviews. The PRISMA-P extension endeavors to facilitate the reporting of review protocols, which also may be useful to rapid review authors when developing their protocol [ 29 , 30 ]. Guidance from the Cochrane Rapid Reviews methods Group is specific to the conduct of rapid reviews of interventions and contains no specific reporting or dissemination advice [ 48 ]. Other similar organization-specific guidance is available (e.g., manual of the Joanna Briggs Institute [ 49 ]); however, this guidance is general and not specific to rapid review. In addition, individual groups or organizations may have internal reporting guidelines or standards. It may be helpful for review authors to check the websites of rapid review producers to see examples of templates and key features [ 15 , 17 ].

The PRISMA checklist provides a starting point for items to be included in a rapid review report (with certain adjustments specific to the context, such as having the title identify the study as a rapid review, rather than a systematic review). However, it may be more helpful to use the reporting items listed in Table 2 , which include some of the PRISMA items but are tailored specifically to rapid reviews. These items may be applicable, depending on the rapid review approach used [ 4 ].

Dissemination of rapid review findings

Dissemination involves the communication of rapid review findings to specific target audiences, across or within settings, and the tailoring of the knowledge to make it usable to the intended stakeholders [ 3 ]. Dissemination may be considered “active” (i.e., efforts using specific strategies and channels) or “passive” (no effort or natural uncontrolled spread) [ 39 ]. Little information on passive dissemination specific to rapid review exists. Active approaches are preferred for research dissemination since passive strategies are generally seen as ineffective [ 39 ]. Here, we describe typical active dissemination activities undertaken by researchers with a lens on health policy and systems research as there is a paucity of literature related to the specific dissemination of rapid review reports.

Before starting the dissemination process, consider your goal and what the intention of the dissemination process is. A goal can be either for dissemination only (i.e., to share your review results with other researchers, funders, policy-makers, or members of the public), or it can be to promote uptake and implementation (i.e., to inform or influence decision-making) [ 3 , 9 , 40 , 50 ]. Where the goal is dissemination only , it is important to identify the targets of the research. These could include researchers, practitioners, policy-makers, patients, and their caregivers or citizens. This will, in turn, inform a targeted active dissemination strategy. A strategy may include presentations at meetings, publications in peer-reviewed publications, or production and sharing of policy briefs, infographics, media releases or social media posts, for example. Preprints (i.e., unvetted versions of research papers) posted to dedicated servers (e.g., medRxiv) provide a platform to enable quick dissemination of rapid review findings [ 51 ]. Other fast dissemination mechanisms could also be considered (e.g., Open Science Framework, Zonodo) when more immediate dissemination is indicated [ 50 ]. Review authors also need to consider how to engage with policy-makers and other types of decision-makers, such as through knowledge exchange events, to share their research results.

If the goal is to promote uptake and implementation , the specific information needs or requests of all knowledge users should guide all dissemination activities. Although the dissemination strategy should focus on meeting the needs of the primary knowledge user, review authors may also consider that if one knowledge user has asked a question, it is likely of interest to others. Review authors may target the primary knowledge user and/or they may also contextualize findings for a broader target audience. Discussion of implementation endeavors and research dissemination frameworks (e.g., Knowledge-to-Action Cycle, the Ottawa Model of Research Use, and the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, and Behaviour [COM-B] model) is beyond the scope of this literature review, although a number of relevant publications are available for further information [ 3 , 27 , 32 , 35 , 40 , 52 , 53 ].

Knowledge translation strategies are universally translatable to all forms of research, yet some considerations may be unique to rapid reviews of health policy and systems research. Research into the dissemination of rapid reviews is extremely limited. Two studies of rapid review producers [ 15 , 17 ] identified variation in research dissemination approaches and tools. In some cases, public dissemination activities may be extremely limited. For example, organizations may choose to post a summary paragraph describing the research, without disseminating a full report [ 15 ]. Most rapid review producers (about 70%) chose to disseminate their reports beyond the commissioning individual or body [ 17 ]. In deciding the dissemination strategy, influencing factors that have been cited include need for permission from the requester, legal implications or sensitivity of the topic, and type of approach used for the rapid review.