“Anthony and Cleopatra” by William Shakespeare Essay

Introduction.

Shakespeare’s plays are commonly with the illusion and deception inherent in the medium of theatre itself, from plays-within-plays to the complications arising from a boy actor playing a girl dressed up as a boy, and by analogy. The theatre then become the world and states of altered reality was the regular element of Shakespeare’s plays. They may be minor alterations, such as those induced by love (Antony in Anthony and Cleopatra). They may be expressed in other-worldly spirits, be they a Puck or an Ariel, they may be symbolic – dreams, sleep, the moon, or the contrast between the wilderness or the wood and the urban city or court. They may depict major alterations of behavior, such as madness, real or feigned.

Anthony and Cleopatra

‘Anthony and Cleopatra’ is a Shakespearian play about two lovers; Anthony, a leader of Rome and Cleopatra, the Queen Of Egypt. The main themes of the play are love and duty as well as betrayal and guilt, the play is written in old English and mainly everyday language. Numerous characters including Enobarbus and Cleopatra, commit betrayal in the play, much imagery is used including the symbolism of God, nature, and water to present its themes, Enobarbus is a loyal friend of Anthony’s until he realizes that Anthony is an unreliable leader, at which point he deserts him, to go to Ceasar. Enobarbus is so overwhelmed with guilt that he takes his own life. The imagery and use of figurative language in his suicide shows his deep feelings of regret.

The play effectively presents the issue of betrayal and guilt by using imagery and showing the extreme effects it can have, Guilt can overwhelm a person so much that they can simply not live with themselves and it shows that cleopetra must have had a lot of love for Anthony, the two lovers and their love, or lack there of, between them. It would be correct to add though that Cleopatra is the dominating presence in the play, however, Cleopatra, Antony and Enobarbus have tragic elements of grandeur, nobility, fateful misjudgments and a fall from the heights as well as other less important qualities. (Shakespeare 157)

The play is repeatedly of different kinds and categories of a drama, Cleopatra tells Antony that, if he truly loves her, he should tell her how much he loves her. Antony responds by telling Cleopatra that professed love has very little value. Antony’s negligent behavior costs him dearly back in Rome.The irony of this situation is that Antony has neglected his soldierly duties for Rome due to the fact that he arrived in Egypt and fell in love with Cleopatra. This is a remarkable beginning to the play because it indicates that, although Antony and Cleopatra are lovers, they either do not actually love each other, or they are too doubtful to declare their love to one another.

Cleopatra as a symbol of Women

The way the audience in Elizabethan times would have viewed her hitting the messenger would also have been very different to ours. To the Elizabethan audience a woman hitting a messenger especially a male messenger would have been outrageous behavior but in our day and age we still see this is unacceptable but it doesn’t really shock us very much. After this incident, Cleopatra was full of guilt that she could not live with herself. This imagery uses nature to symbolize her feelings of wanting to escape her pain and guilt by death, Cleopatra ends up killing herself by making an asp bite her on the breast.

Cleopatra has this same fate after her betrayal, she is also against Anthony. This terrible act of betrayal leads to Anthony’s suicide; as he could not live without Cleopatra, she sends a message saying that she was dead, after being annoyed that he accused her of betrayal, ‘go tell him I have slain myself’. The way that we as modern readers respond to the character of Cleopatra is very different than the way the Elizabethan audience would have responded because although there had been a woman on the throne, they still were shocked by women with power and rights. We do not view her as harshly as Elizabethans because we are now used to women with power, and now that more and more women are getting powerful jobs they now have equal status as men. (Shakespeare 189)

Cleopatra in her “Infinite Variety” Manifests Essential Femininity

The characters of Antony and Cleopatra seem rather childish at times and yet they are older than the characters of Romeo and Juliet. Antony and Cleopatra loved each other however it did not seem in the way that one thinks of as one would in a traditional notion of love. She can act as if a child one minute, and a temptress the next. Before Antony killed himself Cleopatra lied about her death because she did not want to face an upset Antony. Enobarbus says of her that “the age cannot wither her, nor custom stale/ Her Infinite Variety, other women cloy/ the appetites they feed; but she makes hungry/ where most she satisfies” (Shakespeare 199).

Cleopatra is dramatic in her emotions, and is often very theatrical in her reactions and in her rule, her childish actions and deception are what creates the precondition for Antony’s suicide and eventually her own.

Enobarbus is like the rest of the Romans believe Cleopatra is a temptress and is making Antony disregard his duties in the scene on the barge, however, not everyone in the play views Cleopatra as a manipulative woman, one of the most famous lines which is used to describe Cleopatra is spoken by Enobarbus when he says ‘Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale her infinite variety'(Shakespeare 215).

This in my opinion shows that even though Enobarbus knows Cleopatra is taking Antony away from his duties he recognizes why Antony feels so strongly towards her and can also sympathize with this, Enobarbus describes her in a very different way to that which we would think that he views her. He uses words to describe her like ‘love-sick’ and ‘amorous’, and even goes so far as to compare her to the goddess ‘Venus’. I think here that Shakespeare isn’t making her out to be either tragic heroine or ‘triple- turned whore’ but more of a temptress than anything else, to lots of people including Caesar and Enobarbus Cleopatra is very intriguing (Shakespeare 215).

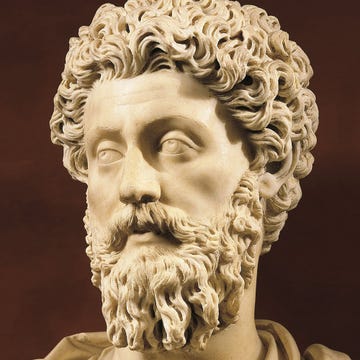

Analysis of Marc Antony

We see also the way Antony treats Cleopatra and the way he feels towards her change throughout the course of the play. The ultimate sacrifice that Cleopatra makes for Antony is at the end of the play when she doesn’t join Caesar, but instead kills herself to be with her true love, but we have to think is this to be with Antony or to escape humiliation? From the start when he considers her almost as a thing for him to entertain him when he is away from home through until he sees her not only as a mistress but also as someone whom he loves. At all points throughout the play, like the way she goes into battle just to see Antony, how she forgives him when he is dying, how she doesn’t really respect him or his obligation to duty. All show us that the character of Cleopatra is portrayed to the audience as not always good, even when he is away for a short period of time she misses him greatly. By the end of the play we can see that she genuinely cares for Antony and can’t live without him. (Shakespeare 233)

Marc Antony – Self-Deluded Lover

There are times throughout the play when Antony does think that she isn’t treating him well and in one instance calls her a ‘foul Egyptian’, then later on, he refers to her as ‘triple-turned whore’ although this is when Antony is at his lowest so there is question whether he really meant it. Romans see Cleopatra as a temptress who is taking away their leader and they know this will lead to the downfall of their army, however in this instance I felt that Cleopatra had betrayed Antony but that was only because like Antony we did not know the truth about what had really happened.

After the battle of Actium when Antony appears to a defeated man, he says the that he alone and isolated in the world that he has drifted away from his way for ever, it is not the appeal of suicide that overpowers him but the burden of his loyalty to Cleopatra.I think that as the main character Shakespeare wants us to side with Antony and view Cleopatra more as a ‘triple-turned whore’ although this makes us feel more sympathetic towards her. In the end it seems that cleopetra is to be blamed because the reason Antony kills himself is because of her and the reason of the dispute between him and Caesar is her. (Shakespeare 245)

In spite of the fact that i am a female, I am drawn to Antony for his loyalty and blind trust that he shows Cleopetra, while she is very conniving and manipulative, this nature of hers ultimately leads to Antony’s death. Antony’s character draws sympathy and gives me a feeling that he never truly knew Cleopetra, and never tried to explore her personality. It also helps me realise that men are much more strainghtforward, while women, though not conniving like Cleopetra, are more complex and have several facets to their personalities that cannot be deciphered by men as was the case of Antony.

In conclusion, in the play Antony and Cleopatra, Caesar has possesses all of the power and control whether it is manipulative, sexual, or political, Cleopatra is in love with Antony and he is in love with her, Cleopetra thinks that killing herself is the ultimate sacrifice she can make to show her love and commitment. She is always doing things to try and make him like her more or to make him jealous, although this is the case Antony and Cleopatra are the characters who end up having the decisive power which stops Caesar from having crucial political and military power over Rome, as it can be seen that Cleopetra in fact is a remarkable woman, who matured before her time. I believe that she is not a ‘Triple-turned whore’ but definitely a tragic heroine. Antony on the other had gains most of his power through the use of strategic thinking which links to the inspiration of military power, she dies in order to be with the man she loved, and if we review the play we see that although a lot of the time her actions are not very honorable to Antony, we but her actions cannot be questioned, because she loved him dearly and for this she eventually committed suicide. Through her reign came beauty, mystery, love, hate, passion, all things that being human and being part of humanity makes her intreguiging and facinating.

Shakespeare, William. Antony and Cleopatra (Cambridge School Shakespeare), Paperback, ISBN: 0-521-44584-1 / 978-0-521-44584-9, Cambridge University Press, 1994, p157-256.

- “Legend of Good Women” by Geoffrey Chaucer

- “Since Cleopatra Died” by Neil Powell

- Queen Elizabeth I and Cleopatra as Female Leaders

- "The Piano Lesson" by August Wilson

- "Metamorphoses" by Zimmerman: The Main Idea of the Play

- "Six Characters in Search of an Author" by Luigi Pirandello

- World Literature. Oedipus the King by Sophocles

- Exploring Diverse Perspectives on Shakespeare's Othello: A Comprehensive Analysis

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, December 18). “Anthony and Cleopatra” by William Shakespeare. https://ivypanda.com/essays/anthony-and-cleopatra-by-william-shakespeare/

"“Anthony and Cleopatra” by William Shakespeare." IvyPanda , 18 Dec. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/anthony-and-cleopatra-by-william-shakespeare/.

IvyPanda . (2021) '“Anthony and Cleopatra” by William Shakespeare'. 18 December.

IvyPanda . 2021. "“Anthony and Cleopatra” by William Shakespeare." December 18, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/anthony-and-cleopatra-by-william-shakespeare/.

1. IvyPanda . "“Anthony and Cleopatra” by William Shakespeare." December 18, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/anthony-and-cleopatra-by-william-shakespeare/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "“Anthony and Cleopatra” by William Shakespeare." December 18, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/anthony-and-cleopatra-by-william-shakespeare/.

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Drama Criticism › Analysis of William Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra

Analysis of William Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on July 26, 2020 • ( 0 )

Antony and Cleopatra is the definitive tragedy of passion, and in it the ironic and heroic themes, the day world of history and the night world of passion, expand into natural forces of cosmological proportions.

—Northrup Frye, “The Tailors of the Earth: The Tragedy of Passion,” in Fools of Time: Studies in Shakespearean Tragedy

Among William Shakespeare’s great tragedies, Antony and Cleopatra is the anomaly. Written around 1607, following the completion of the sequence of tragedies that began with Hamlet and concluded with Macbeth , Antony and Cleopatra stands in marked contrast from them in tone, theme, and structure. For his last great tragedy, Shakespeare returned to his first, Romeo and Juliet . Like it, Antony and Cleopatra is a love story that ends in a double suicide; however, the lovers here are not teenagers, but the middle-aged Antony and Cleopatra whose battle between private desires and public responsibilities is played out with world domination in the balance. Having raised adolescent love to the level of tragic seriousness in Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare here dramatizes a love story on a massive, global scale. If Hamlet , Othello, King Lear , and Macbeth conclude with the prescribed pity and terror, Anthony and Cleopatra ends very differently with pity and triumph, as the title lovers, who have lost the world, enact a kind of triumphant marriage in death. Losing everything, they manage to win much more by choosing love over worldly power. Antony and Cleopatra is the last in a series of plays, beginning with Romeo and Juliet and including Troilus and Cressida and Othello, that explores the connection between love and tragedy. It also can be seen as the first of the playwright’s final series of romances, followed by Cymbeline, The Winter’s Tale, and The Tempest in which love eventually triumphs over every obstacle. Antony and Cleopatra is therefore a peculiar tragedy of affirmation, setting the dominant tone of Shakespeare’s final plays.

Structurally, as well, Antony and Cleopatra is exceptional. Ranging over the Mediterranean world from Egypt to Rome to Athens, Sicily, and Syria, the play has 44 scenes, more than twice the average number in Shakespeare’s plays. The effect is a dizzying rush of events, approximating the method of montage in film. Shakespeare’s previous tragedies were constructed around a few major scenes. Here there are so many entrances and exits, so many shifts of locations and incidents that Samuel Johnson condemned the play as a mere string of episodes “produced without any art of connection or care of disposition.” Later critics have discovered the play’s organizing principle in its thematic contrast between Rome and Egypt, supported by an elaborate pattern of images, contrasts, and juxtapositions. There is still, however, disagreement over issues of Shakespeare’s methods and intentions in Antony and Cleopatra . Critic Howard Felperin has suggested that the play “creates an ambiguity of effect and response unprecedented even within Shakespeare’s work.” The critical debate turns on how to interpret Antony and Cleopatra , perhaps the most complex, contradictory, and fascinating characters Shakespeare ever created.

Antony and Cleopatra picks up where Julius Caesar left off. Four years after Caesar’s murder, an alliance among Octavius, Julius Caesar’s grandnephew; Mark Antony; and the patrician politician Lepidus has put down the conspiracy led by Brutus and Cassius and resulted in a division of the Roman world among them. Antony, given the eastern sphere of the empire to rule, is now in Alexandria, where he has fallen in love with the Egyptian queen Cleopatra. Enthralled, Antony has ignored repeated summonses to return to Rome to attend to his political responsibilities. By pursuing his desires instead, in the words of his men, Antony, “the triple pillar of the world,” has been “transform’d into a strumpet’s fool.” The play immediately establishes a dominant thematic contrast between Rome and Egypt that represents two contrasting worldviews and value systems. Rome is duty, rationality, and the practical world of politics; Egypt, embodied by its queen, is private needs, sensual pleasure, and revelry. The play’s tragedy stems from the irreconcilable division between the two, represented in the play’s two major movements: Antony’s abandoning Cleopatra and Egypt for Rome and his duties and his subsequent defection back to them. Antony’s lieutenant Enobarbus functions in the play as Antony’s conscience, whose sexual cynicism stands in contrast to the love-drenched Egyptian court.

Antony is forced to take action when he learns that his wife, Fulvia, who started a rebellion against Octavius, has died, and that Sextus Pompey, son of Pompey the Great, is claiming his right to power by harrying Octavius on the seas. His resolve to return to Rome to take up his duties there displeases Cleopatra, and they engage in a back-and-forth lover’s exchange of insults, avowals of love, and jealous recriminations and, ultimately, a mutual awareness of Antony’s dilemma in trying to reconcile his personal desires with his political responsibilities. Antony comforts Cleopatra by saying:

Our separation so abides and flies, That thou residing here, goes yet with me; And I hence fleeting, here remain with thee.

The second act begins in the house of Sextus Pompey, who gauges the weakness of the three triumvirs, especially Antony, whom he hopes will continue to be distracted by Cleopatra: “Let witchcraft join with beauty, lust with both, / Tie up the libertine in a field of feasts.” In the house of Lepidus, a quarrel between Antony and Octavius over Fulvia’s rebellion and Antony’s irresponsibility threatens to sever the bond between them. Agrippa, Octavius’s general, suggests a marriage between Antony and Octavius’s sister, Octavia. Antony agrees to the marriage as a political necessity, for the good of Rome and to patch up the quarrel. After Antony and Octavius leave to visit Octavia, Enobarbus tells Agrippa and Maecenas, another follower of Octavius, about the splendors of Egypt and Cleopatra’s remarkable allure. Maecenas remarks sadly that, because of the marriage, “Now Antony / Must leave her utterly.” Enobarbus, despite his cynicism, understands Cleopatra’s powerful attractiveness and disagrees:

Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale Her infinite variety. Other women cloy The appetites they feed, but she makes hungry Where most she satisfies.

Enobarbus’s remarks make clear that the alliance between Antony and Octavius will be short lived, setting both on a collision course.

After his marriage Antony consults an Egyptian soothsayer, who predicts Octavius’s rise and counsels Antony to return to Egypt:

Nobel, courageous, high, unmatchable, Where Caesar’s is not. But near him thy ange l Becomes afeard, as being o’erpowered. Therefore Make space enough between you.

.Angrily dismissing the soothsayer, Antony nevertheless agrees with his analysis, recognizing that “I’th’ East my pleasure lies.” Before Antony leaves for Egypt, however, the triumvirs and rebels meet on Pompey’s galley for a night of drinking and feasting following negotiations. Antony’s capacity for raucous merrymaking shows the self-indulgence that will lead to his downfall, while Octavius’s sobriety, if puritanical and passionless, nevertheless bespeaks an iron will and determination that eventually will insure his victory over his rivals.

As the third act begins, Ventidius, another of Antony’s commanders, has conquered the Parthians, a victory for which he diplomatically plans to let Antony take credit. Antony, now in Athens with Octavia, learns that Octavius has slandered him and is warring against Pompey. The alliance between the two triumvirs, as well as Antony’s control over his own forces, is further threatened when Antony discovers that Octavius has imprisoned Lepidus to solidify his position and that one of his officers has murdered Pompey. Octavia returns to Rome to try to repair the breach between husband and brother. There, Octavius tells her that Antony has returned to Egypt and convinces her that Antony is not only unfaithful but is preparing for war: “He hath given his empire / Up to a whore.” Octavius responds by preparing to engage Antony in battle at Actium. In Egypt Enobarbus fails to convince Cleopatra not to take part in the battle, and the lovers also discount Enorbarbus’s logical reasons for fighting Octavius on land rather than sea. This decision is partly due to Octavius’s challenge: He dares Antony to meet him in a naval engagement. Cleopatra claims, “I have sixty sails. Octavius none better,” and Antony is unable to resist either Octavius’s challenge or Cleopatra’s bravado. At Actium a sickened Enobarbus watches as Cleopatra’s ships turn tail and flee, and a despairing, shame-filled Antony follows her “like a doting mallard” with his ships. Cleopatra apologizes to Antony for the retreat, and he forgives her, but when Antony sees Octavius’s ambassador kissing Cleopatra’s hand and her cordial behavior toward him, he becomes enraged, berating Cleopatra and ordering the messenger Thidias to be whipped. Again the couple are reconciled, and Antony decides to stake all on another battle. Enobarbus, however, has had enough of Antony’s clouded judgment and makes plans to desert him and join Octavius.

In the fourth act Octavius scoffs at Antony’s challenge to meet him in a duel and prepares for war with confidence, knowing that many of his rival’s men have defected to him. When Antony learns of Enobarbus’s desertion he forgives his friend and generously sends his treasure to him. Enobarbus reacts to Antony’s magnanimity with remorse and dies desiring Antony’s forgiveness. Antony scores an initial victory over Octavius, but in a later sea battle and on land in the Egyptian desert, Antony’s army is routed. Enraged, Antony blames Cleopatra and accuses her of betraying him. Terrified by his anger, Cleopatra seeks refuge in her monument and plots to regain Antony’s affection by send-ing word to him that she has slain herself. Her plan disastrously misfires when the news shames Antony into taking his own life:

I will o’ertake thee, Cleopatra, and Weep for my pardon. So it must be, for now All length is torture; since the torch is out, Lie down and stray no farther.

He orders his servant Eros to stab him, but Eros takes his own life instead to prevent carrying out the order. Antony then falls upon his sword and when he is told that Cleopatra is still alive, asks to be taken to her in a final acknowledgment that his life and happiness are inextricably bound to her. Just before he dies Antony offers his own eulogy at the end of his long struggle between desire and duty:

The miserable change now at my end Lament nor sorrow at; but please your thoughts In feeding them with those my former fortunes Wherein I liv’d the greatest prince o’ th’ world, The noblest; and do now not basely die, Not cowardly put off my helmet to My countryman— a Roman by a RomanValiantly vanquish’d.

In the fifth act Octavius hears of Antony’s death and mourns the passing of a great warrior before moving to procure his spoils: Cleopatra. He sends word that she has nothing to fear from him, but Cleopatra tries to stab herself to prevent the Roman soldiers from taking her prisoner and is stopped. When Dolabella, one of Octavius’s lieutenants, attempts to placate her, she accuses him of lying, and he admits that Octavius plans to display her as his conquest in Rome. Octavius arrives, promising to treat her well if she complies with his wishes while ominously threatening her destruction if she follows “Antony’s course.” Pretending compliance, Cleopatra says of Octavius to her attendants when he departs: “He words me, girls, he words me, that I should not / Be noble to myself.” Sending for a basket of figs containing poisonous snakes, Cleopatra prepares herself for death:

Give me my robe, put on my crown, I have Immortal longings in me. Now no more The juice of Egypt’s grace shall moist this lip.

Stage-managing her own end, Cleopatra anticipates joining Antony as his worthy wife:

. . . Methinks I hear Antony call. I see him rouse himself To praise my noble act. I hear him mock The luck of Caesar, which the gods give men To excuse their after wrath. Husband, I come. Now to that name my courage prove my title!

Placing one of the snakes at her breast, Cleopatra dies. When Octavius returns, he speaks admiringly of her:

Bravest at the last, She levell’d at our purposes, and being royal, Took her own way.

Implying by his words an envy of Antony and Cleopatra ’s passion and eminence, Octavius commands:

She shall be buried by her Antony; No grave upon the earth shall clip in it A pair so famous. High events as these Strike those that make them; and their story is No less in pity than his glory which Brought them to be lamented.

In the contest with Rome, Egypt must lose. Desire is no match against cold calculation for worldly power. Human frailty cannot survive an iron will, and yet the play makes its case that despite all the contradictions and clear character imperfections in Antony and Cleopatra, with all their willful self-indulgence, their love trumps all. By the manner of their going and the human values they ultimately assert, Antony and Cleopatra leave an immense emptiness by their death. Octavius wins, but the world loses by their passing. Shakespeare stages an argument on behalf of what makes us human, even at the cost of an empire. His lovers rise to the tragic occasion for a concluding triumph befitting a magnanimous warrior and a queen of “infinite variety.”

Antony and Cleopatra Oxford Lecture by Prof. Emma Smith

Antony and Cleopatra PDF (1MB)

Share this:

Categories: Drama Criticism , Literature

Tags: Analysis Of William Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra , Antony and Cleopatra Analysis , Antony and Cleopatra Criticism , Antony and Cleopatra Essay , Antony and Cleopatra Guide , Antony and Cleopatra Lecture , Antony and Cleopatra PDF , Antony and Cleopatra Summary , Antony and Cleopatra Themes , Bibliography Of William Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra , Character Study Of William Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra , Criticism Of William Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra , ELIZABEHAN POETRY AND PROSE , Essays Of William Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra , Literary Criticism , Notes Of William Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra , Plot Of William Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra , Simple Analysis Of William Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra , Study Guides Of William Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra , Summary Of William Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra , Synopsis Of William Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra , Themes Of William Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra

Related Articles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You are using an outdated browser. This site may not look the way it was intended for you. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

London School of Journalism

- Tel: +44 (0) 20 7432 8140

- [email protected]

- Student log in

Search courses

English literature essays, the tragic in william shakespeare's antony and cleopatra.

by Isabelle Vignier

His captain's heart, Which in the scuffles of great fights hath burst The buckles on his breast, reneges all temper And is become the bellows and the fan To cool a gipsy's lust.

Antony and Cleopatra seems to have a special place in Shakespeare's works because it is at a crossroad between two types of play. It clearly belongs to what are generally called the 'Roman' plays, along with Coriolanus and Julius Caesar . But it is also considered a tragedy. The importance of history in the play cannot be denied, especially where it is compared to Shakespeare's 'great' tragedies such as Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet . But one might wonder what is specifically tragic in Antony and Cleopatra , and what can be said about the tragic in a play which is so different from the other tragedies. It is clear that the notion of 'tragic' in the everyday sense is not necessarily the same as the notion of 'tragedy', which is a philosophical notion whose definition depends on which philosophic system one takes into account. In this article I shall take the term tragic in its literary and dramatic sense and try to define its main characteristics. Taking into account a wide corpus of plays, from Antiquity as well as from France and England, we can detect several constant features that can define the tragic. A tragedy usually shows a character that is outstanding by his rank or/and inner abilities, falling into misfortune as a result of fate, and because of an error or a weakness for which he is not really responsible. Several tragic elements can be detected in Antony and Cleopatra . First, we find characters that have high rank because they are outstanding figures; we also see a tragic situation because from the beginning of the play we see no hope of a happy ending. In the end, even if it is hard to see a transcendence in action, the play shows a failure of human freedom, a determinism in the character's fate that can be considered as the essence of tragic. The heroes of Antony and Cleopatra have high rank and ability because they are above the level of common people. This is a general characteristic in tragedies. Tragic heroes are extraordinary specimens of mankind. They can be remarkable for their intelligence (as is Oedipus, the main character of Oedipus Rex by Sophocles), their cruelty (like Medea, in the eponymous tragedy by Seneca), or their nobleness in mind, (like Caesar in Cinna by Corneille). Very often the tragic hero is from royal blood. Antony, in Shakespeare's play as well as in Roman history, is a military leader of incredible power, intelligence and courage. Caesar himself shows his esteem for him when he reproaches him for his present moral decay:

If Cleopatra does not have such a strong moral sense, she is remarkable for her royal rank - she is the last queen of Egypt - her beauty, her intelligence and her audacity. Enobarbus quotes the episode of her being brought to Antony in a carpet. Last but not least, her sense of honour and dignity gives her a special nobleness that is typically tragic. Although she fears death - which is why she flees from the sea battle - she'd rather kill herself than be exposed to Caesar's triumph. Cleopatra, even if she shows weakness and unpleasant traits, stands apart from other women. Even Octavia, who possesses all the typical Roman virtues, cannot compete with her. Barely married to her, Antony comes back to the Egyptian queen. Cleopatra and Antony are a mythic couple. A tragic hero is usually outstanding, but not perfect. He/she is unwittingly guilty of some fault that makes him somehow deserve the disaster that happens to him. This view was put forward by the first theoretician of drama, Aristotle, and elucidated by Racine, in the XVIIth century:

This view is exemplified in the character of Antony. One cannot deny that his love for Cleopatra is a weakness and even a fault. His passion makes him forget his duty, his honour as a soldier. He leaves the battle against Caesar because of Cleopatra, and he is an unfaithful husband to Fulvia and Octavia. On Cleopatra's advice he decides to fight at sea although his chances would be much better on land. On the other hand, his passion is not voluntary. He tries to resist it - by marrying Octavia, he tries to give politics a higher priority than love - but fails. As a result, the spectator - or reader - cannot but feel compassion for him, even if he more or less 'deserved' his terrible end. Cleopatra, even if many traits of hers are unpleasant (she mistreats the unfortunate messenger who announces the marriage of Antony and Octavia, and she is particularly mean to her rival) deserves our compassion too. Shakespeare creates in her a character that is much more likely to awaken pity than the Cleopatra described in Plutarch, the main source of the play. According to an article from Josette Hérou, 'Antony and Cleopatra: sources and influences' (2000) [1] although Shakespeare followed very carefully the historical events described by Plutarch, he took some liberties with his source, especially in the treatment of Cleopatra's character. Plutarch describes her as a woman without scruples, manipulative, ready to do anything to keep her throne. To her, Antony was nothing more than a puppet she had to seduce for political reasons. She did not care about his person but only about his power. In Shakespeare's play, she is truly in love with Antony. When he is away, she asks for mandragora, 'That (she) might sleep out this great gap of time', while 'My Antony is away' (Act I, scene V). We do not see any reason why she should feign in the presence of Charmian. This true passion makes us sympathise with her. Another characteristic feature of tragic heroes is that their personal fate is always linked to the destiny of a community. Their unhappiness is not merely a domestic catastrophe, but concerns many people. This is particularly clear when heroes have a political role, which is very often the case, especially in Greek tragedies. But even when the heroes are not sovereigns or leaders, their fates have an impact on community life. In Romeo and Juliet the two young heroes are of noble origin and their deaths is what eventually seals reconciliation between their families. In Antony and Cleopatra , this characteristic is particularly obvious: nothing less than the future of the Roman Empire - that is to say, the whole world for Romans of the time - is at stake. The rivalry between Caesar and Antony is a tragedy for Rome, since it leads to civil war. Antony's death is of great consequence for the Roman Empire: 'The death of Antony / Is not a single doom, in the name lay / A moiety of the world' (Act V, scene I) says Caesar as he hears about his rival's suicide. The fall of Cleopatra is also the fall of Egypt, which becomes eventually a part of the Roman Empire. By killing herself, Cleopatra does not only save her honour and dignity, but also the dignity of her nation. The fates of tragic heroes and heroines arouses compassion and terror, 'which are the true effects of tragedy (Racine, 1674, Preface of Iphigénie en Aulide). But the situation itself shows tragic features, because from the start of the play we see the characters in a deadlock. There is no hope for a happy ending. We have a situation such as described by Christian Biet in his definition of tragic: 'Les valeurs de l'homme tragique sont irréalisables, contradictoires et aucun compromis n'est possible, ni aucun choix qui puisse déboucher sur une situation heureuse ou harmonieuse'. (1997) 'The values of the tragic man are unrealisable and conflicting and no compromise can be made, nor any choice that might lead to a happy or harmonious situation'. Antony's two great passions: his ambition and his love for Cleopatra, are fundamentally impossible to reconcile. From the first verse of the play, we see that Cleopatra is not accepted by Antony's soldiers, she is shown as incompatible with his honour. Philo begins the play by complaining about the general's moral decline:

The contrast between the greatness of Antony and the unworthiness of his love is shortly stressed again: Antony is 'The triple pillar of the world transform'd/ Into a strumpet's fool'. This passion is shown as unworthy, and we see that it is dangerous since it causes Antony to make serious strategic mistakes and lose a decisive battle against Caesar. It also makes him neglect his new wife Octavia, which breaks the brief reconciliation between the two rivals. A solution to the problem might be for Antony to give up Cleopatra, but to do so is not in his power and would not make him happy: 'I'th'East my pleasure lies' (Act II, scene III) he says soon after his wedding with Octavia. The love between Antony and Cleopatra is tragic because there is no way it could make them happy. If the conflict in Antony himself cannot be resolved, the political conflict cannot but have a bloody end. Antony, Caesar and Pompey are in a struggle for power and the party organised by Pompey to seal reconciliation does not fool the spectator. After Pompey's death, the struggle between Caesar and Mark Antony is inevitable. Two men of such outstanding capacity and ambition cannot be satisfied with a half of the world each. Caesar sums up the situation after Antony's death:

Antony's death is fortunate for Caesar - from a strictly political point of view - but that does not stop him from weeping for Antony, whom he esteemed and perhaps even loved: 'my brother, my competitor' he says. The merciless conflict is tragic because no one is to blame for it. The two characters try not to fight each other, but they cannot escape their own nature. Neither of them is the 'good' or the 'bad' one. A situation where characters have no other choice than fighting each other, without one being more innocent than the other, is typically tragic. This aspect of tragedy is wonderfully expressed by the French dramatic author Jean Anouilh in his play Antigone (1944), in a passage spoken by the Chorus:

Caesar cannot be held responsible for Cleopatra's death either. It is true that he, 'though he be honourable' as Dolabella says (Act V, scene II) intends to lead the queen in triumph, which would be a great humiliation for her. But he does not really have a choice: not using the Egyptian queen to enhance his triumph would be a political mistake. In this situation, Caesar and Cleopatra both do what they have to do in their respective situations. As a fallen queen, Cleopatra does not have any other possibility than death. If the conflict between the two leaders is inevitable, so is the decline of a country, and a civilisation. The independence of Egypt is doomed from the beginning of the play. Cleopatra tries to preserve it but she has no chance. The love between Antony and the queen of Egypt may seem to offer some hope, but the submission of one nation to another is as inevitable as the victory of one of the two competitors. When Antony leads the battle by sea, it is because of his passion for Cleopatra; she makes him defend her country: 'I made these wars for Egypt', he says, believing himself betrayed by the queen (Act IV, scene XIV). As soon as Antony has lost, Cleopatra has no political power and has to submit herself to the master of Rome. The ambassador explains to Caesar, even before Antony's death:

The tragic in Antony and Cleopatra is partially that the situation is from the beginning a knot that can only be undone by the death of some characters, and even of a country as an independent nation. No compromise can be found that would satisfy everyone. That makes for an important feature of tragedy - an insoluble conflict between the hero and his environment. But the main characteristic of tragic remains the fatum, a determinism that does not allow the heroes to be masters of their own lives. We know from the beginning that the end has to be disastrous, but do we really see how it is going to end? The length of the play, the numerous incidents in it (Antony's marriage with Octavia, the battle won by Caesar, Enobarbus's suicide, the death of Pompey, the false announcement of Cleopatra's death) make it difficult to see a logical chain of events in the play and therefore a determinism. As Christian Biet explains: 'La définition minimale du tragique serait peut-être la suivante: est tragique tout ce qui relève du fatum, de la nécessité, et qui met radicalement en échec la liberté humaine, qui pourtant s'exerce' (1997). 'The minimum definition of what tragic is might be the following: tragic is anything that belongs to fatum, to necessity, and makes human freedom radically fail, although it is indeed exerted'. We do not hear (as we do in Classical tragedy) about gods pursuing vengeance against one of the protagonists, but nevertheless we can see elements of a determinism that does not let the hero master his fate. The first is the irresistible violence of passion, that Antony cannot resist, and against which his free will fails. Antony is perfectly aware that his passion for Cleopatra wrongs him: 'These strong Egyptian fetters I must break,/ Or lose myself in dotage' (Act I, scene II). He tries to escape the power she has on him, to use his freedom to be himself again. His marriage with Octavia shows this: he is not compelled to marry her, but shows enthusiasm for the idea: 'I am not married, Caesar: let me hear / Agrippa further speak' (Act II, scene II). This is an attempt to make use of liberty that fails. According to Lepidus, Antony simply cannot change his nature:

The determinism that works in the play is more psychological than transcendental. Antony is not only the victim of his own nature: his will also fails against the power of Cleopatra. This power is only human, but is no less mighty for that. It seems that Cleopatra is so cunning and attractive that there was absolutely no possibility for Antony to resist her once she had set her mind to seduce him. Enobarbus - who, interestingly, does not particularly like Cleopatra - gives a description of the queen the first time Antony saw her that clearly presents her as irresistible:

In the same scene, Enobarbus says that Cleopatra is a women a man cannot get tired of:

When Antony fails in his military duty by following Cleopatra, who flees the sea battle, he confesses that he could not have acted differently. Cleopatra's power on him is so strong it was impossible for him to resist it:

As Oedipus, who commits the most terrible crimes (killing his father, marrying his mother) without knowing it, and all typical tragic heroes, Antony is guilty, but not responsible. Antony and Cleopatra also seem to have to submit to a force than makes Caesar inevitably triumphant. Here again, it is more about a psychological determinism than about the traditional will of gods. Early in Act II, the winner of the struggle for Roman power is foretold, since we hear the Soothsayer predicting to Antony that he has no chance to win against Caesar:

Caesar's victory may not be written in the stars, but it is ineluctable because he is a winner, he has a quasi supernatural luck. Of course, the Soothsayer might have been bribed by Caesar to discourage Antony (the hypothesis has often been put forward), but the latter recognises himself the veracity of the prediction:

- Aristotle: Poetics

- Matthew Arnold

- Margaret Atwood: Bodily Harm and The Handmaid's Tale

- Margaret Atwood 'Gertrude Talks Back'

- Jonathan Bayliss

- Lewis Carroll, Samuel Beckett

- Saul Bellow and Ken Kesey

- John Bunyan: The Pilgrim's Progress and Geoffrey Chaucer: The Canterbury Tales

- T S Eliot, Albert Camus

- Castiglione: The Courtier

- Kate Chopin: The Awakening

- Joseph Conrad: Heart of Darkness

- Charles Dickens

- John Donne: Love poetry

- John Dryden: Translation of Ovid

- T S Eliot: Four Quartets

- William Faulkner: Sartoris

- Henry Fielding

- Ibsen, Lawrence, Galsworthy

- Jonathan Swift and John Gay

- Oliver Goldsmith

- Graham Greene: Brighton Rock

- Thomas Hardy: Tess of the d'Urbervilles

- Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Scarlet Letter

- Ernest Hemingway

- Jon Jost: American independent film-maker

- James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Will McManus

- James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Ian Mackean

- James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Ben Foley

- Carl Gustav Jung

- Jamaica Kincaid, Merle Hodge, George Lamming

- Rudyard Kipling: Kim

- D. H. Lawrence: Women in Love

- Henry Lawson: 'Eureka!'

- Machiavelli: The Prince

- Jennifer Maiden: The Winter Baby

- Ian McEwan: The Cement Garden

- Toni Morrison: Beloved and Jazz

- R K Narayan's vision of life

- R K Narayan: The English Teacher

- R K Narayan: The Guide

- Brian Patten

- Harold Pinter

- Sylvia Plath and Alice Walker

- Alexander Pope: The Rape of the Lock

- Jean Rhys: Wide Sargasso Sea. Charlotte Bronte: Jane Eyre: Doubles

- Jean Rhys: Wide Sargasso Sea. Charlotte Bronte: Jane Eyre: Symbolism

- Shakespeare: Twelfth Night

- Shakespeare: Hamlet

- Shakespeare: Shakespeare's Women

- Shakespeare: Measure for Measure

- Shakespeare: Antony and Cleopatra

- Shakespeare: Coriolanus

- Shakespeare: The Winter's Tale and The Tempest

- Sir Philip Sidney: Astrophil and Stella

- Edmund Spenser: The Faerie Queene

- Tom Stoppard

- William Styron: Sophie's Choice

- William Wordsworth

- William Wordsworth and Lucy

- Studying English Literature

- The author, the text, and the reader

- What is literary writing?

- Indian women's writing

- Renaissance tragedy and investigator heroes

- Renaissance poetry

- The Age of Reason

- Romanticism

- New York! New York!

- Alice, Harry Potter and the computer game

- The Spy in the Computer

- Photography and the New Native American Aesthetic

Website navigation

A Modern Perspective: Antony and Cleopatra

By Cynthia Marshall

Near the end of Antony and Cleopatra, the captive Cleopatra muses about her dead lover: “I dreamt there was an emperor Antony. / O, such another sleep, that I might see / But such another man” ( 5.2.93 –95 ) . Disregarding repeated attempts by Caesar’s follower Dolabella to interrupt her rapturous description, Cleopatra finally asks him, “Think you there was, or might be, such a man / As this I dreamt of?” to which he replies, “Gentle madam, no” ( 5.2.115 –17 ) . In a realistic sense, Dolabella’s answer is correct: Cleopatra has spoken of Antony as a Herculean figure who strides the seas scattering islands like coins, a figure of mythic proportion. Yet the force of Cleopatra’s imaginative act, the vivid quality of her dream, suggests a limitation in Dolabella’s technical accuracy. This exchange, testing both the status of heroes and the visionary capacity of lovers, is indicative of the play’s preoccupations as well as its method of considering them. By repeatedly featuring conflicts between different points of view, Antony and Cleopatra functions not simply as tragedy, history, or Liebestod ( a story of a couple dying for love ) but as an inquiry into the historical, political, philosophical, and aesthetic grounds on which any story might be staged in the theater.

Because ancient Rome served as a model for Shakespeare’s English culture, Antony and Cleopatra presumes an audience with some prior knowledge of Roman history. It dramatizes events from 40 BCE, when Rome was ruled by the uneasy triumvirate of Mark Antony, Octavius Caesar, and Lepidus ( established after the assassination of Julius Caesar ) , to 30 BCE, when the civil war that culminated in Octavius Caesar’s defeat of Mark Antony at Actium destroyed the triumvirate. But if Antony and Cleopatra continues in a chronological sense from where Julius Caesar left off, it exhibits a strikingly different attitude toward its historical material. While the earlier play focuses on disputes internal to Roman rule, the later one is concerned with the politics of a vast empire spanning the Mediterranean. The arguments in Julius Caesar center on questions of political philosophy and civic duty, but in Antony and Cleopatra these issues are complicated by attention to spheres of erotic experience and family life that we now think of as private. A telling example of this transformation of attitude between the two plays is Cleopatra’s reference to Antony’s “sword Philippan” ( 2.5.27 ) ; previously used at the battle of Philippi, which concludes Julius Caesar, it is here employed by Cleopatra in erotic play with an Antony dressed in her “tires and mantles” ( 2.5.26 ) . Antony and Cleopatra was written much later in Shakespeare’s career than Julius Caesar , and in Antony and Cleopatra Shakespeare goes much further in probing beneath the surface of historical narrative and in questioning the terms on which heroic reputations were based than he had in earlier English or Roman history plays. Accordingly, the play has posed problems of generic classification and of response, for Antony and Cleopatra defies much of what we have come to associate with either a history play or a heroic tragedy: Antony shares the spotlight with Cleopatra, the point of view is uncertain, and heroic virtue is in scant supply. Even the play’s structure, with its profusion of short scenes, its elimination of staged battles, and its extension for an entire act after the hero’s death, challenges traditional notions of dramatic tragedy.

Like most of the characters in Antony and Cleopatra, Shakespeare uses the past to measure the significance of present events. Yet in this play he suggests that access to history is compromised not only by the viewer’s belatedness but also by limitation of perspective and by the reliability of sources: witness Cleopatra’s success in compelling from the messenger a personally flattering account of Octavia ( 3.3 ) . Moreover, Shakespeare seems peculiarly aware of the extent to which historical narratives are shaped by myths and legends. Much as Plutarch, whose Life of Marcus Antonius served as the main source for Antony and Cleopatra, attempted to differentiate between myth and history while including both in his treatment of Noble Grecians and Romans, so Shakespeare offers mythic invocation alongside a chastening skepticism. Octavius Caesar nostalgically invokes the warrior Antony of bygone days who could “drink / The stale of horses” and feed on “strange flesh” ( 1.4.70 –71, 77 ) . Philo, in the speech that opens the play, compares Antony as a “triple pillar of the world” to “plated Mars” ( 1.1.13 , 4 ) . For Octavius and Philo, as for the other Romans in the play, Antony’s descent from his former glory to the embarrassing spectacle of his passion for Cleopatra plays out another myth, that of sexual temptation and its destructive results, familiar from the tale of Hercules and Omphale. Antony himself frequently subscribes to this myth, lamenting his temptation to “lose [him]self in dotage” and resolving to break free from the clutches of his “enchanting queen” ( 1.2.129 , 143 ) . But a comparison between Antony’s moments of despondency and his equally strong exhilaration in happy moments with Cleopatra—“Let Rome in Tiber melt and the wide arch / Of the ranged empire fall. Here is my space” ( 1.1.38 –39 ) —especially as his passion is echoed and continued in her words, suggests that the romantic myth of transcendent love may be the strongest one the play has to offer. Nevertheless, if Shakespeare can be said to endorse the legendary love of Antony and Cleopatra, his method of doing so is distinctly odd: the love affair plays against a chorus of doubtful voices intent on puncturing the stability or accuracy of any enshrined romance.

This contrast of viewpoints is built on the play’s central structural principle, a binary opposition between Rome and Egypt. The play’s Rome, on the one hand, is a predominantly male social order encouraging individual discipline, valor, and devotion to the state. Egypt, on the other hand, is a looser society valuing sensual and emotional pleasure. By juxtaposing these two settings, Shakespeare highlights the cultural contrast. He also uses the opposition to create complicated patterns of judgment by positioning some of his characters as commentator figures. Philo and Demetrius in 1.1 , or Scarus and Canidius in 3.10 , offer Roman value judgments on Antony’s Egyptian escapades; yet Enobarbus appreciates Cleopatra and Egyptian life and thus becomes a challenging conveyor of culture for the other Romans. Early in the play, another commentator, the Soothsayer, advises Antony that he will never thrive near Octavius. As Janet Adelman points out, questioning and judgment are central to the play’s structure. 1

As critics have responded to the play, Rome has traditionally been the winner in the implicit contest between Roman and Egyptian values. Bernard Beckerman notes how the audience is initially “invited to see events with Roman eyes, eyes that rarely see anything but the imperfections of Egypt.” 2 Looking through Roman eyes has in fact led some readers to scorn the play altogether; for instance, George Bernard Shaw objected to giving “sexual infatuation” a tragic treatment it scarcely warranted. 3 Many have judged Cleopatra a manipulative, self-serving temptress or femme fatale; some have endorsed the enraged Antony’s charge that she is a whore ( 4.12.15 ) . But recent critical paradigms have made it possible to view the play through more or less Egyptian eyes, celebrating the feminine values exemplified by Cleopatra and the realm in which she reigns. Hélène Cixous, for instance, praises the “ardor” and “passion” of “she who is incomprehensible.” 4 Although Cixous’ praise is definitely for Cleopatra as a woman, the positive valuation she gives to incomprehensibility signals a breakdown of the opposition between Rome and Egypt. Cixous and other contemporary thinkers show that the either/or logic of binarism is itself a typically “Roman” pattern. Or to put their argument another way, Cleopatra’s “infinite variety” ( 2.2.277 ) deconstructs an oppositional logic. Her femininity is not the logical opposite of Antony’s masculinity but a disruptive counterpart that throws gender norms into question. Understood in these terms, Egypt does not so much contrast with Rome as reveal the limitations of Roman rule. Thus Shakespeare’s portrayal of the relationship between Cleopatra and Antony, and of that between Egypt and Rome, illustrates what Jacques Derrida calls différance, the logic through which two terms are caught in irresolvable dependency on one another.

As a great encounter between West and East as well as a great love story, Antony and Cleopatra enacts a basic pattern of colonialism. Shakespeare draws on a network of stereotypes when he shows orderly, ambitious Roman conquerors confronting exotically decadent, emotional Egyptian subjects. Given the enormous indebtedness of Shakespeare’s culture to the Roman world—Rome offered models for English politics, mythology, literature, architecture—one might expect the play firmly to endorse the Western system of values. That this does not quite happen is partly the result of the reiterated ironies against “the boy Caesar” ( 3.13.21 ) , dismissed by Cleopatra as “paltry” in his pursuit of dominion, since “Not being Fortune, he’s but Fortune’s knave” ( 5.2.2 –3 ) . The play largely supports Cleopatra’s assessment: Octavius is rigidly militaristic and chillingly manipulative. ( Although the Romans regularly used marriage to foster political alliances, Octavius’ bartering of his sister is disconcertingly set against the passion between Antony and Cleopatra. ) In marked contrast to the title characters, Octavius not only lacks a personal dimension but appears simple-minded in his understanding of human affairs. He admits only a single aspect of Antony, measuring him as a heroic soldier fallen from honor to become “th’ abstract of all faults,” “not more manlike / Than Cleopatra” ( 1.4.10 , 5 -6 ) . That Antony has lost his former heroism is as true, of course, as Dolabella’s denial that Cleopatra’s dream man ever existed. Yet few who read or see the play sympathetically would want to limit their assessments to the ones these Romans voice. Reassuringly familiar as the terms of Octavius’ moral opprobrium and Dolabella’s realism may be, the play offers pleasures beyond them. Neither love nor imagination will square with Roman virtue, and in pursuing these two themes Shakespeare subverts a victory of Roman over Egyptian values. Perhaps he was appealing to an English audience aware that their country was once a colonial “other” to Rome.

As a character, Antony embodies the opposition between Roman and Egyptian value systems; his story enacts the collapse of that opposition. He spans the worlds of West and East geographically, appearing in numerous settings in the course of the play’s action, and he is torn between competing loyalties. After temporarily securing his political alliance with Octavius through marriage to Octavia, Antony abandons her, saying “though I make this marriage for my peace, / I’ th’ East my pleasure lies” ( 2.3.45 –46 ) . Officially representing a dominating Rome in Egypt, Antony has ( to the dismay of his Roman partners ) “gone native,” adopting the mores of his conquered territory. As Dympna Callaghan points out, a tendency to become the other is part of Antony’s character. 5 Fighting against barbarians, he reportedly endured “more / Than savages could suffer” ( 1.4.69 –70 ) ; governing a luxuriously decadent territory, he immerses himself in sensuality. Cleopatra delights in Antony’s complexity, praising his “well-divided disposition” ( 1.5.62 ) , his “heavenly mingle” ( 69 ) . For her, appreciating his value is a matter of perspective: “Though he be painted one way like a Gorgon, / The other way ’s a Mars” ( 2.5.144 –45 ) . For Antony himself, however, the internalization of antithetical values becomes disturbingly disintegrative. He is repeatedly “robbed” of his sword ( 4.14.28 , 5.1.29 ) , first by Cleopatra, later by Dercetus—an emblem of his loss of masculinity. Masculine identity, by Roman standards, requires a coherency and stability that Antony’s passion for Cleopatra dissolves, and as a result he shames himself, most memorably by following Cleopatra’s ships at the battle of Actium. Caught between the rival demands to maintain Roman authority and to pursue his ardor for Cleopatra, he feels torn apart and compares himself to a shape in the clouds, feeling he “cannot hold this visible shape” ( 4.14.18 ) . Even the heroic suicide that would offer a final image of cohesion eludes him; he falls on his sword like a “bridegroom” running into “a lover’s bed” ( 4.14.120 –21 ) , and survives to utter the dismaying question “Not dead?” ( 4.14.124 ) . Although he claims to die “a Roman by a Roman / Valiantly vanquished” ( 4.15.66 –67 ) , we are given the image of a lover’s rather than a hero’s death.

Antony’s decline clearly can be understood in moral terms as a fall away from Roman grace, but Shakespeare complicates this interpretation. Antony, more than Cleopatra, is the play’s central object of interest and desire: his Roman partners as well as his Egyptian lover yearn for his presence and attentions. In Antony, Shakespeare illustrates Plutarch’s remark that “the soul of a lover lived in another body, and not in his own.” 6 Antony’s melancholic recognition that he does not own or control his existence undermines the oppositional morality that produces heroic paradigms. It also deconstructs the logic of colonialism, whereby a conquering power eclipses another culture and/or set of values. Antony instead becomes uncomfortably aware of the interpenetration of self and other in the various spheres of love, politics, and ethics.

Watching the play or thinking about it as drama, one realizes that theater too is able to break down established differences by encouraging emotional and imaginative connections. The complex interplay of voices and viewpoints in Antony and Cleopatra requires us to do something more difficult than merely choosing sides in a moral debate. We are asked to participate in shifting judgments—to follow Enobarbus, for instance, when he is compelled by his disenchantment to abandon Antony, only to be devastated by his captain’s generous response to his betrayal. “Be a child o’ th’ time” ( 2.7.117 ) Antony advises the fastidious Octavius Caesar, and the play likewise solicits our imaginative involvement. Yet the spectacles to which we attend are riddled with comments that puncture the presented illusion. Cleopatra’s reference to the actor who will “boy [her] greatness” ( 5.2.267 ) famously complicates her final defiance of Caesar. Similarly, her remark on lifting Antony’s body to her monument—“Here’s sport indeed. How heavy weighs my lord!” ( 4.15.38 ) —bizarrely compounds the meanings of sport and heaviness, calling a theater audience’s attention to the sheer physical challenges of the scene being staged. A queen who can win admiration while hopping through the street clearly understands the seductive power of surprising mixtures of tone. Like a modern film star intent on maintaining her fans’ fascination, Cleopatra defies an analysis measuring truth and sincerity, but she is anything but shallow. In her most profound moments, she reminds us of how devotion and delight can merge with sheer playfulness. Rather than asking viewers to suspend their disbelief, Antony and Cleopatra features characters who disbelieve their own presentations of experience and who somehow are all the more compelling for it. Shakespeare scours received myths with skepticism, and then audaciously presents them for his audience’s admiring participation.

In acknowledging the flux of temporality, Antony’s advice to “be a child o’ th’ time” implicitly points to the difficulty of representing historical events in a world of change. Shakespeare leaves unanswered questions about motivations and meaning instead of offering his version of the illustrious love affair as definitive. Moreover, the play effectively counters received history: even though Octavius Caesar was the acknowledged victor of the story, defeating Antony to become emperor of Rome, the play’s final act presents not his triumph but Cleopatra’s. With superb poise she stages her own death, collapsing time to become again the queen who first met Antony at Cydnus and merging death into new life ( “Dost thou not see my baby at my breast, / That sucks the nurse asleep?” [ 5.2.368 –69] ) . She achieves a magnificence that leaves Caesar looking like an “ass / Unpolicied” ( 5.2.364 –65 ) . In their final moments, both Antony and Cleopatra refer to an afterlife—“Where souls do couch on flowers, we’ll hand in hand” ( 4.14.61 ) ; “Husband, I come!” ( 5.2.342 ) —although the play presents no sustained belief system to support these images of reunion. Instead, it offers theatrical apotheosis as the “new heaven, new Earth” ( 1.1.18 –19 ) necessary to demonstrate Antony’s and Cleopatra’s love.

Shakespeare returns in this play to a theme of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the capacity of erotic imagination to transform ordinary experience. But where the lovers of the earlier play were in the directive power of love juices, the mature lovers Antony and Cleopatra are fully conscious of devoting themselves to eros and of altering the course of history with their actions. Antony and Cleopatra make a claim for love as a force that dissolves established barriers, even established identities. Staging their story, Shakespeare makes a similar claim for theater.

- Janet Adelman, The Common Liar: An Essay on “Antony and Cleopatra” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973), p. 14.

- Bernard Beckerman, “Past the Size of Dreaming,” in Twentieth Century Interpretations of “Antony and Cleopatra,” ed. Mark Rose (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1977), p. 102.

- George Bernard Shaw, “Three Plays for Puritans,” in The Complete Prefaces of Bernard Shaw (London: Paul Hamlyn, 1965), p. 749.

- Hélène Cixous, The Newly Born Woman , trans. Betsy Wing (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986), p. 126.

- Dympna Callaghan, “Representing Cleopatra in the Post-colonial Moment,” in Antony and Cleopatra , ed. Nigel Wood, Theory in Practice (Buckingham, [Bucks.]: Open University Press, 1996), pp. 58–59.

- Plutarch, The Life of Marcus Antonius , in Narrative and Dramatic Sources of Shakespeare , ed. Geoffrey Bullough (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1964), 5:301.

Stay connected

Find out what’s on, read our latest stories, and learn how you can get involved.

Antony and Cleopatra's Legendary Love Story

Antony first met Cleopatra when she was 'still a girl and inexperienced'

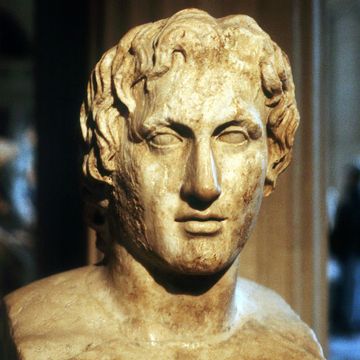

Their love story had started over 10 years earlier when both were in their prime. Cleopatra was the divine Ptolemaic ruler of prosperous Egypt – brilliant, silver-tongued, charming, scholarly and the richest person in the Mediterranean. Politician and soldier Antony, supposedly descended from Hercules, was “broad-shouldered, bull-necked, ridiculously handsome, with a thick head of curls and aquiline features.”

Boisterous, mirthful, moody and lustful, Antony had been a favorite of Caesar . In the wake of Caesar’s assassination, Antony formed an uneasy Triumvirate in 43 BC with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus and Caesar’s nephew Octavian to rule the sprawling Roman Republic. Antony was put in charge of the Empire’s rowdy Eastern territories.

In 41 BC, Antony sent for Cleopatra while he was staying in the magnificent city of Tarsus, near the coast of what is now Turkey. He had first met Cleopatra in Rome when she had been the young mistress of his mentor Caesar (the two had a son Caesarion). But Antony was meeting a very evolved Cleopatra. Caesar “had known her when she was still a girl and inexperienced in affairs,” the Greek writer and philosopher Plutarch wrote , “but she was going to visit Antony at the very time when women have the most brilliant beauty and are at the acme of intellectual power.”

Cleopatra wooed Antony 10 years later, making him lose 'his head to her like a young man'

Aware of Antony’s love of spectacle – and of Rome’s interest in her riches – Cleopatra orchestrated an entrance into Tarsus designed to awe Antony and his cohorts. According to Stacy Shiff’s Cleopatra: A Life , she sailed into the city in an “explosion of color” underneath billowing purple sails:

She reclined beneath a gold-spangled canopy, dressed as Venus in a painting, while beautiful young boys, like painted Cupids, stood at her sides and fanned her. Her fairest maids were likewise dressed as sea nymphs and graces, some steering at the rudder, some working at the ropes. Wondrous odors from countless incense-offerings diffused themselves along the river-banks.

The pageantry worked. “The moment he saw her, Antony lost his head to her like a young man,” he Greek historian Appian wrote. Cleopatra was not done – throwing extravagant parties and dinners for the Romans, flaunting her riches by giving away all the furniture, jewels and hangings from the soirees. She drank and sparred with Antony, who “was ambitious to surpass her in splendor and elegance,” throwing his own parties that never quite lived up to hers.

Though it appears their attraction was genuine, it was also politically savvy “and…thought to harmonize well with the matters at hand.” As Schiff notes, Antony needed Cleopatra to fund his military endeavors in the East and Cleopatra needed him for protection, to expand her power and assert the rights of her son Caesarion, Caesar’s true heir.

The powerful rulers had a playful relationship

Antony soon followed Cleopatra to Alexandria, which was experiencing an artistic, cultural and scholarly renaissance under their Queen. The two powerful rulers often behaved like college students, forming a drinking society they called the Society of the Inimitable Livers. “The members entertained one another daily in turn, with an extravagance of expenditure beyond measure or belief,” Plutarch explained .

The new couple also loved to tease each other. One legend has it that at one party, Cleopatra bet Antony she could spend 10 million sesterces on one banquet. According to the Roman chronicler Pliny the Elder :

She ordered the second course to be served. In accordance with previous instructions, the servants placed in front of her only a single vessel containing vinegar. She took one earing off, and dropped the pearl in the vinegar, and when it wasted away, she swallowed it.

Another time, Antony, the masterful athletic soldier, was frustrated as he fumbled with a fishing rod during a riparian entertainment. “Leave the fishing rod, General, to us,” Cleopatra joked. “Your prey are cities, kingdoms and continents.”

Antony left a pregnant Cleopatra to go to Rome, married another woman, but they eventually reunited

Antony was soon off to Rome to report on his triumphs. In his absence – by 40 BC –Cleopatra gave birth to their twins, Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene. That same year Antony married another intelligent dynamo – Octavian’s sister Octavia. Seemingly happy in his new marriage, Antony and Cleopatra did not meet for three and a half years, until the lovers reunited in Antioch, the capital of Syria in 37 BC.

The two picked up right where they left off, even issuing currency engraved with both their faces. In Antioch, Antony met his twins for the first time and bestowed large swaths of land on their mother. “As of 37, Cleopatra ruled over nearly the entire eastern Mediterranean coast, from what is today eastern Libya, in Africa, north through Israel, Lebanon, and Syria, to southern Turkey, excepting only slivers of Judaea," Schiff writes.

For the next two years, the couple would often travel together, as Antony’s military and administrative exploits took them all over the Mediterranean. It was during this period that Antony’s military prowess began to falter, causing him to lose thousands of men. Of course, instead of the blame being placed on Antony’s rash, bull-headed decisions, Plutarch would blame the failures on Cleopatra:

So eager was he to spend the winter with her that he began the war before the proper time and managed everything confusedly. He was not master of his own faculties, but, as if he were under the influence of certain drugs or of magic rites, was ever looking eagerly towards her, and thinking more of his speedy return than of conquering the enemy.

The couple staged 'The Donations of Alexandria' against Octavian

However, Antony’s fortunes were briefly reversed when he successfully conquered the kingdom of Armenia. In the fall of 34 BC, he triumphantly returned to Alexandria, where the Armenian royal family was paraded in chains. Reunited with Cleopatra, “the two most magnificent people in the world” staged an event that came to be known as “The Donations of Alexandria.” According to Schiff:

In the open court of the complex that fall day the Alexandrians discovered another silver platform, on which stood two massive golden thrones. Mark Antony occupied one. Addressing her as the “New Isis,” he invited Cleopatra to join him on the other. She appeared in the full regalia of that goddess, a pleated, lustrously striped chiton, its fringed edge reaching to her ankles. On her head she may have worn a traditional tripartite crown or one of cobras with a vulture cap. By one account Antony dressed as Dionysus, in a gold-embroidered gown and high Greek boots… Cleopatra’s children occupied four smaller thrones at the couple’s feet. In his husky voice Antony addressed the assembled multitude.

In an intentional provocation to Octavian, Antony distributed lands to his and Cleopatra’s children, making it abundantly clear that their family was the dynasty of the East.

For Octavian, this was a bridge too far. In 33 BC, the Triumvirate disbanded. The next year, Antony divorced Octavia. All pretenses of partnership and friendship between the two men were over. Shortly after the divorce, Octavian declared war on Antony’s true partner – Cleopatra.

Still, their power was no match for the Roman army

For all of Cleopatra’s riches, and the couple’s combined military prowess, they were no match for the Roman army. As Octavian and his forces closed in on Alexandria, the lovers continued their decadent parties, although they now called their drinking society “Companions to the Death.” Longtime advisors deserted, as did much of Antony’s army. While Antony was off battling Octavian’s forces, Cleopatra busied herself building a new “temple to Isis,” which she called her mausoleum. According to Schiff:

Into the mausoleum she heaped gems, jewelry, works of art, coffers of gold, royal robes, stores of cinnamon and frankincense, necessities to her, luxuries to the rest of the world. With those riches went as well a vast quantity of kindling. Were she to disappear, the treasure of Egypt would disappear with her. The thought was a torture to Octavian .

Cleopatra staged a fake suicide, resulting in Antony's own death...and Cleopatra ingesting poison

It also appears that Cleopatra was secretly negotiating with Octavian, unbeknownst to Antony. Always the more level-headed and strategic of the two, Cleopatra no doubt saw that Antony was doomed – but their children might not be. She had word sent to Antony that she had killed herself, knowing that he would soon follow. She was right. According to Plutarch, when Antony was told of his partner’s death, he uttered the immortal words:

O Cleopatra, I am not distressed to have lost you, for I shall straightaway join you; but I am grieved that a commander as great as I should be found to be inferior to a woman in courage.

After his attempted suicide, a distraught Cleopatra had Antony brought to her. Seeing what she had done, she was heartbroken but resolute. After Antony breathed his last, Cleopatra fought on, attempting to negotiate with Octavian. But all hope was lost, and Cleopatra snuck poison (or in some versions an asp) past Octavian’s guards. When Octavian realized what had happened, he sent soldiers to bust into the temple. There they found Cleopatra dead, her two attendants, Charmion and Iras, near death. According to Schiff:

Charmion was clumsily attempting to right the diadem around Cleopatra’s forehead. Angrily one of Octavian’s men exploded: “A fine deed this, Charmion!” She had just the energy to offer a parting shot. With a tartness that would have made her mistress proud, she managed, “It is indeed most fine, and befitting the descendant of so many kings,” before collapsing in a heap, at her queen’s side.

With Cleopatra’s death, Egypt became part of the Roman Empire. Caesarion was murdered, while Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene and Ptolemy Philadelphus were brought to Rome to be raised by Octavia. Her victorious brother erased all traces of the once glorious couple, but he did make one concession. Honoring her last request, he had Cleopatra and Antony buried side by side.

Napoleon Bonaparte

Queen Elizabeth II

Marcus Aurelius

Pontius Pilate

Maria Theresa

Alexander the Great

Nicholas II

Kaiser Wilhelm

Kublai Khan

Join Now to View Premium Content

GradeSaver provides access to 2360 study guide PDFs and quizzes, 11007 literature essays, 2769 sample college application essays, 926 lesson plans, and ad-free surfing in this premium content, “Members Only” section of the site! Membership includes a 10% discount on all editing orders.

Essays on Antony and Cleopatra

The portrayal of the relationship between antony and cleopatra by shakespeare, duty and desire in antony and cleopatra, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

The Role of Enobarbus in Shakespeare’s "Antony and Cleopatra"

Exploring the use of imagery by shakespeare in antony and cleopatra, foreshadowing cleopatra's betrayal in "antony and cleopatra" by shakespeare, a theme of clashing duty and desire in antony and cleopatra, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Shakespeare’s Depiction of True Loyalty in Antony and Cleopatra

Antony and cleopatra act 2 analysis: character development, from calamity to real life: shakespeare’s ‘antony and cleopatra’ and samuel johnson, steadfast stoicism in antony and cleopatra, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

Instances Where Stagecraft Has Been Employed in Antony and Cleopatra

Controversy and parallelism in antony and cleopatra, literary explication of virginia woolf’s william shakespeare, controversial victory: does caesar realize complete triumph, cleopatra as a mere snippet for a monarch, act 3 scene 11 analysis: actium and the new outlook on antony, western versus eastern values in antony and cleopatra, duality in minor characters: antony and cleopatra act 1, the soldiers with horns, the mutable and puzzling nature of cleopatra as presented by shakespeare, love and power in shakespeare's antony and cleopatra, the roles of captain wentworth and cleopatra in jane austen’s persuasion and shakespeare’s antony and cleopatra, relevant topics.

- Macbeth Ambition

- A Raisin in The Sun

- Romeo and Juliet

- Hamlet Theme

- Death of a Salesman

- Macbeth Guilt

- Doctor Faustus

- As You Like It

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Antony responds by telling Cleopatra that professed love has very little value. Antony's negligent behavior costs him dearly back in Rome.The irony of this situation is that Antony has neglected his soldierly duties for Rome due to the fact that he arrived in Egypt and fell in love with Cleopatra. This is a remarkable beginning to the play ...

Structurally, as well, Antony and Cleopatra is exceptional. Ranging over the Mediterranean world from Egypt to Rome to Athens, Sicily, and Syria, the play has 44 scenes, more than twice the average number in Shakespeare's plays.The effect is a dizzying rush of events, approximating the method of montage in film. Shakespeare's previous tragedies were constructed around a few major scenes.

After Antony's death at the end of Act IV, Cleopatra says to her handmaiden Charmian that "Our lamp is spent" and concludes "Come we have no friend/But resolution and the briefest end" (IV, xv, ll ...

He brings charges against Lepidus, denies Antony his spoils from Pompey's defeat, and seizes cities in the eastern Roman colonies that Antony rules. The play's emphasis, however, is on those whom Caesar defeats: Antony and his wealthy Egyptian ally, Queen Cleopatra. The play does not sugarcoat Antony and Cleopatra's famous love affair ...