We Need to Talk About Books

The picture of dorian gray by oscar wilde [a review].

The Picture of Dorian Gray had a notorious reputation even before it was used against its author, Oscar Wilde, at his trial for gross indecency. Where it may lack originality in its premise, it more than makes up for it in the evocation of the contrasts and contradictions of high and low 19 th century London society.

Basil Hallward and Lord Henry Wotton manage to maintain a friendship despite being very different men. Hallward, a painter, is a man of strong moral convictions but, he fears, weak character. Situations that may lead him astray cause him great anxiety and will usually result in him seeking an escape. Wotton, an aristocrat and a dandy, in contrast, revels in his repute for being a hedonist and a libertine. In fact, Wotton is quite mischievous. Despite the reputation he cultivates, he does not act on his supposed principles. Rather, he enjoys the effect his scandalous remarks have on those around him and prefers to influence others to indulge themselves while he observes the results. Naturally, Hallward finds Wotton antagonising.

‘You are an extraordinary fellow. You never say a moral thing, and you never do a wrong thing. Your cynicism is merely a pose.’

Wotton senses a new opportunity for mischief when he visits Hallward to see his latest work – a full-length portrait of a young man of exceptional personal beauty. Initially, Hallward refuses to reveal the subject’s identity, before telling Wotton about his first encounter with Dorian Gray. Hallward certainly does not want Wotton to meet this man who has affected him so profoundly. It is at that moment that Gray’s arrival is announced.

Lord Henry looked at him. Yes, he was certainly wonderfully handsome, with his finely curved scarlet lips, his frank blue eyes, his crisp gold hair. There was something in his face that made one trust him at once. All the candour of youth was there, as well as all youth’s passionate purity. One felt that he had kept himself unspotted from the world. No wonder Basil Hallward worshipped him.

After being introduced to Gray, Wotton wastes no time to set in motion his usual tricks. Wotton immediately launches into delivering a sermon to the young man all about influences and impulses; sin and temptation; fear, courage and submission.

‘I believe that if one man were to live out his life fully and completely, were to give form to every feeling, expression to every thought, reality to every dream – I believe that the world would gain such a fresh impulse of joy that we would forget all the maladies of [medievalism], and return to the Hellenic ideal – to something finer, richer than the Hellenic ideal, it may be. […] The body sins once, and has done with its sin, for action is a mode of purification. Nothing remains then but the recollection of a pleasure, or the luxury of a regret. The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it. Resist it, and your soul grows sick with longing for the things it has forbidden to itself, with desire for what its monstrous laws have made monstrous and unlawful.’ […] ‘Stop!’, faltered Gray, ‘stop! You bewilder me. I don’t know what to say. There is some answer to you, but I cannot find it.’

Gray, young, somewhat innocent and not very introspective, is impressed by Wotton’s ideas, especially when Wotton warns Gray that his beauty will inevitably fade. When Hallward shows Gray his portrait, Gray is initially joyful at the representation of his beauty, but, remembering what Wotton said, grows resentful. He is even jealous that, while his looks will fade, the painting will remain beautiful and mock him. He wishes their places could be reversed – that his likeness in the painting would age while he remained youthful.

‘How sad it is!’ murmured Dorian Gray, with his eyes still fixed upon his own portrait. ‘How sad it is! I shall grow old, and horrible, and dreadful. It will never be older than this particular day of June…. If it were only the other way! If it were I who was to be always young, and the painting that was to grow old! For that – for that – I would give everything! Yes, there is nothing in the whole world I would not give! I would give my soul for that!’

Under Wotton’s influence, Gray begins taking tentative steps outside his comfort zone and the walls of respectable society. When he cruelly breaks a young woman’s heart, he discovers that his wish has become true – his portrait bears the mark of his cruelty and he does not. Though he is briefly remorseful, Wotton counsels Gray out of his conscience. Gray now feels an unprecedented freedom to follow his desires, to succumb to temptations of sin.

Eternal youth, infinite passion, pleasures subtle and secret, wild joys and wilder sins – he was to have all these things. The portrait was to bear the burden of his shame: that was all.

The Picture of Dorian Gray gets off to a great start. The descriptions of the characters and the locations, which come together in their social gatherings, immerses the reader with its impression of a privileged, elite, social class inhabiting London society of the late nineteenth century. Add to that the endlessly quotable witticisms of Wotton and the morality tale of Gray’s pursuit of vice without consequence, and the reader can be swiftly seduced into this world.

If you were already aware of the outline of the plot, you might assume that it is a fairly straightforward tale but in fact the novel has more complexity and thoughtfulness to it. In particular, I enjoyed some of the contrasts between the characters, major and minor, and how their aspects conflict and conspire. I thought the evolution of Gray’s character was well-worked and thought out. When we first meet Gray, he is very innocent and vulnerable. Once Gray begins his journey from innocence and vulnerability to self-corruption, he grows in confidence and self-assurance and knows his own mind well enough to be outspoken in disagreement. And, original or not, I thought the use of the transforming painting made an interesting literary device.

His unreal and selfish love would yield to some higher influence, would be transformed to some nobler passion, and the portrait that Basil Hallward had painted of him would be a guide to him through life, would be to him what holiness is to some, and conscience to others, and the fear of God to us all. There were opiates for remorse, drugs that could kill the moral sense to sleep. But here was a visible symbol of the degradation of sin. Here was an ever-present sign of the ruin men brought upon their souls.

Though direct, I enjoyed a lot of the narration and some scenes were wonderfully dramatic and will be quite memorable.

Several interesting themes are explored in the novel. There is the superficiality in culture, especially amongst the social elites, and the premium it places on appearances, youthfulness and beauty. Wotton’s hedonistic philosophy, which he contemplates and observes rather than indulges in, is taken to its extremes by Gray who experiences its moral implications. Taken together, these combine to show the reader the error of mistaking appearance for reality, especially when making assumptions of good moral character on members of high society and the good looking.

Sin is a thing that writes itself across a man’s face. It cannot be concealed. People talk sometimes of secret vices. There are no such things. If a wretched man has a vice, it shows itself in the lines of his mouth, the droop of his eyelids, the moulding of his hands even.

There are questions about the role and purpose of art versus the aesthetic ideal. Heredity as destiny is explored as some characters embrace the legacy of the forebears while others seek to escape it. There is also the conflict between the public and private selves and the fantasy of living a double life.

There were a few things I did not enjoy in The Picture of Dorian Gray . Wotton speaks mostly in epigrams which, at first, can be deliciously witty. There are, in fact, far too many clever lines to quote. But I felt that this can soon become tedious and Wotton tiresome.

‘A woman will flirt with anybody in the world as long as other people are looking on.’ ‘How fond you are of saying dangerous things, Harry! […] You are talking scandal Harry, and there is never any basis for scandal.’ ‘The basis of every scandal is an immoral certainty,’ said Lord Henry, lighting a cigarette. ‘You would sacrifice anybody, Harry, for the sake of an epigram.’

Knowing that The Picture of Dorian Gray was Oscar Wilde’s only novel and that it was used as evidence against him at his trial, I had mistakenly assumed that it was written late in his career. In fact, it was published before his major plays, such as Lady Windermere’s Fan and The Importance of Being Earnest , which recycled some of the lines from The Picture of Dorian Gray . The early parts of the novel read a bit like a novel written by a playwright. By that I mean it can be a bit dialogue-heavy and that dialogue is very direct and unsubtle. The reader can effortlessly imagine the scenes taking place on stage. Elsewhere, the novel could have used less subtlety – there are some key exclusions at important plot points.

One of the advantages of reading this Penguin Classics edition is that it includes an appendix of contemporary reviews of The Picture of Dorian Gray which give an impression of the novel’s reception and which I enjoyed reading. Most of the reviews were at least a little negative, some very. Some simply found the story and the writing to be not very good – stupid, vulgar, dull, boring and silly were some of the adjectives of one. But most critique the book for its ‘moral’. Some say the story does have a moral but it is an ‘evil’ one, some say it does not do enough to show a moral preference. Some reinforce their argument by saying that Wilde’s defence of the story’s moral is contrived and inconsistent while others contradict this by saying Wilde dismissed any moral interpretation of the story which they found untenable.

These seem a little exaggerated and unfair. I don’t think works of fiction necessarily need to show moral preference in their telling. Otherwise tragedy has little room to work with. Empathy and judgement of the characters and their actions can be left for the reader to interpret. One wonders if Edgar Allan Poe or Robert Louis Stevenson were similarly critiqued. On the other hand, since critiquing the idea that art should have some moral value or purpose, as opposed to the aesthetic ideal of ‘art for art’s sake’, is one of the points of the novel, such a reaction is probably fitting.

Some included in the selection were a bit more positive though not necessarily for flattering reasons. A review from the Christian Leader enjoyed the unfavourable portrayal of the ‘gilded paganism’ of the era which it likened to the worst excesses of Rome! It also enjoyed the fact that Gray is shown to have been led astray in part by reading a dangerous book.

This edition also contained the Introduction by Peter Ackroyd from an earlier Penguin Classics edition. My main takeaway from this introduction was Ackroyd’s point that London, like Gray, has a double life in the novel; the decadence of London’s exclusive clubs contrasted with its opium dens.

English readers were not accustomed to such a forceful characterisation of their civilisation, and Wilde went even further than this; he mocked both the artistic pretensions and the social morality of the English, and some of the most powerful passages in the novel disclose the grinding poverty and hopelessness against which ‘Society’ turned its face. Wilde, an Irishman, was putting a mirror up to his oppressors – and their shocked reactions would eventually encircle him when he stood in the dock at the Old Bailey.

My main takeaway from reading the new Introduction by Robert Mighall was the message in the novel of a mutual influence between culture and corruption – a point which immediately brought to my mind a modern double life immorality tale – American Psycho. Mighall seems sceptical of how much originality can be attributed to The Picture of Dorian Gray with reason. Tales of double lives, of fatal deals for eternal youth and magical paintings have a long history in ancient mythology and medieval legend – Faust and Narcissus being two that immediately come to mind.

Perhaps if I had kept some of these antecedents in mind while reading The Picture of Dorian Gray , I might have enjoyed it less. But maybe not. I think Wilde does enough to complicate the story with incidents, characters and themes outside of, and diverting to, the main story. If some elements are unoriginal, this is offset by the context of the period setting where the issues of the day are inserted into the story, giving it a point of difference to other iterations. It does have a complicated history, though, with controversy and multiple revisions that can confuse and irritate attempts at a consistent interpretation. For me, The Picture of Dorian Gray joins a very large pile of books that I did enjoy but not tremendously.

Share this:

It’s been years since I read this! Never really felt the need to return to it – one of those stories you know the essence of without heading back to its source.

Like Liked by 1 person

I suppose it doesn’t really have a twist or something that would make you come back with new eyes to go deeper a second time. It might make readers check out some of his other work though. Thanks for sharing

This was one of those unexpected classics. There is really nothing much in it to justify how widespread and well known it became but I suppose whatever was in it was enough to render it one of those classics every child is expected to read at some stage. Also, I never quite understood why it was called picture of Dorian Gray instead of Portrait…

Yes. I think another reason for its endurance is that people like the use of the metaphor of the magic painting to teach the moral. It has an almost Greek tragedy feel to it

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

A Summary and Analysis of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

The Picture of Dorian Gray is Oscar Wilde’s one novel, published originally in 1890 (as a serial) and then in book form the following year. The novel is at once an example of late Victorian Gothic horror and , in some ways, the greatest English-language novel about decadence and aestheticism, or ‘art for art’s sake’.

To show how these themes and movements find their way into the novel, it’s necessary to offer some words of analysis. But before we analyse The Picture of Dorian Gray , it might be worth summarising the plot of the novel.

The Picture of Dorian Gray : summary

The three main characters in The Picture of Dorian Gray are the title character (a beautiful young man), Basil Hallward (a painter), and Lord Henry Wotton (Basil Hallward’s friend).

The novel opens with Basil painting Dorian Gray’s portrait. Lord Henry Wotton takes a shine to the young man, and advises him to be constantly in search of new ‘sensations’ in life. He encourages Dorian to drink deep of life’s pleasures.

When the picture of Dorian is finished, Dorian marvels at how young and beautiful he looks, before wishing that he could always remain as young and attractive while his portrait is the one that ages and decays, rather than the other way around. When he proclaims that he would give his soul to have such a wish granted, it’s as if he has made a pact with the devil.

Basil’s finished portrait is sent to Dorian’s house, while Dorian himself goes out and follows Lord Henry’s advice. He falls head over heels in love with an actress, Sibyl Vane, but when she loses her ability to act well – because, she claims, now she has fallen in love for real she cannot imitate it on the stage – Dorian cruelly discards her. He had fallen in love with her art as an actress, and now she has lost that, she is meaningless to him.

Sibyl takes her own life before Dorian – who has observed a change in his portrait, which looks to have a slightly meaner expression than before – can apologise to her and beg her forgiveness. But Lord Henry consoles Dorian, arguing that Sibyl, in dying young, has given her last beautiful performance.

Dorian, shocked by the change in the portrait, locks it away at the top of his house, in his old schoolroom. Inspired by an immoral ‘yellow book’ which Lord Henry gives to him, Dorian continues to experience all manner of ‘sensations’, no matter how immoral they are. When he next takes a look at the portrait in his attic, he finds an old and evil face, disfigured by sin, staring out at him.

The novel moves forward some thirteen years. Dorian, of course, is still young and fresh-faced, but his portrait looks meaner and older than ever. When Dorian shows the portrait to Basil, who painted it, the artist – who had worshipped Dorian’s beauty when he painted the picture – is shocked and appalled. Dorian stabs Basil to death, before enlisting the help of someone to dispose of the body (this man, horrified by what he has done, will later take his own life).

Dorian slides further into sin and evil, until one day, the brother of the dead actress, Sibyl Vane, bumps into Dorian Gray and intends to exact revenge for his sister’s mistreatment at the hands of Dorian. But when he follows Dorian to the latter’s country estate, he is accidentally shot by one of Dorian’s shooting party.

Dorian becomes intent on reforming his character, hoping that the portrait will start to improve if he behaves better. But when he goes up to look at the painting, he finds that it shows the face of a hypocrite, because even his abstinence from vice was, in its own way, a quest for a new sensation to experience.

Horrified and angered, Dorian plunges a knife into the canvas, but when the servants walk in on him, they find the portrait as it was originally painted, showing Dorian Gray as a youthful man. Meanwhile, on the floor, there is the body of a wrinkled old man with a ‘loathsome’ face.

The Picture of Dorian Gray : analysis

The Picture of Dorian Gray has been analysed as an example of the Gothic horror novel, as a variation on the theme of the ‘double’, and as a narrative embodying some of the key aspects of late nineteenth-century aestheticism and decadence.

Wilde’s skill lies in how he manages to weave these various elements together, creating a modern take on the old Faust story (the German figure Faust sold his soul to the devil, via Mephistopheles) which also, in its depictions of late Victorian sin and vice, may remind readers of another work of fiction published just four years earlier: Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (which we’ve analysed here ).

Indeed, the discovery of the body of Dorian Gray as a wrinkled and horrifically ugly corpse at the end of the novel recalls the discovery of Jekyll/Hyde in Stevenson’s novella.

To find the novel’s value as a book of the aesthetic movement, we need look no further than Wilde’s preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray , in which he states, for instance, that ‘there is no such thing as a moral or immoral book’ (what matters is whether the book is written well or not) and ‘all art is quite useless’ (art shouldn’t change the world: art exists as, and for, itself, and no more).

Lord Henry Wotton is very much the voice of the aesthetic movement in the novel, and many of his pronouncements echo those made by the prominent art critic (under whom Wilde had studied at Oxford), Walter Pater. But whereas Pater talked of ‘new impressions’, Lord Henry (or Wilde, in his novel) took this up a notch, calling for new ‘sensations’.

We tend to speak conveniently of ‘periods’ or ‘movements’ or ‘eras’ in literary history, but these labels aren’t always useful. Both Oscar Wilde and Elizabeth Gaskell, the author of Mary Barton and North and South , were ‘Victorian’ in that they were both writing and publishing their work in Britain during the reign of Queen Victoria (1837-1901).

But whereas Gaskell, writing in the 1840s, 1850s, and 1860s, wrote ‘realist’ novels about the plight of factory workers in northern England, Wilde wrote a fantastical horror story about upper-class men who are able to stay forever young and spotless while their portraits decay in their attic. They’re a world away from each other.

Wilde’s novel is a good example of how later Victorian fiction often turned against the values and approaches favourited by earlier Victorian writers. It was Wilde who, famously, said of the sad ending of Dickens’s The Old Curiosity Shop , which Dickens’s original readers in the 1840s wept buckets over, ‘one must have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell without’ – what, crying?

No. Wilde’s word was ‘laughing’. The overly sentimental style favoured by mid-century novelists like Dickens had given way to a more casual, poised, nonchalant, and detached mode of storytelling.

At the same time, we can overstate the extent to which Wilde’s novel turns its back on earlier Victorian attitudes and values. Despite his statement that there is no such thing as a moral or immoral book, The Picture of Dorian Gray is a highly moral work, as the tale of Faust was. Dorian’s life is destroyed by his commitment to a life of pleasure, even though it entails the destruction of other lives – most notably, Sibyl Vane’s.

Far from being a book that would be denounced from the pulpits by Anglican clergymen for being ‘immoral’, The Picture of Dorian Gray could make for a pretty good moral sermon in itself, albeit one that’s more witty and entertaining than most Christian sermons.

The Picture of Dorian Gray is, at bottom, a novel of surfaces and appearance. We say ‘at bottom’, but that is precisely the point: the novel is, as many critics have commented, all surface. Lord Henry is so taken by the beauty of Dorian Gray that he sets about being a bad influence on him.

Dorian is so taken by the painting of him – a two-dimensional representation of his outward appearance – that he makes his deal with the devil, trading his soul, that thing which represents inner meaning and inner depth, in exchange for remaining youthful on the outside.

Then, when Dorian falls in love, it’s with an actress, not because he loves her but because he loves her performance. When she loses her ability to act, he abandons her. Her name, Sibyl Vane, points up the vanity of acting and the pursuit of skin-deep appearance at the cost if something more substantial, but her first name also acts as a warning: in Greek mythology, the Sibyls made cryptic statements about future events.

But there’s probably a particular Sibyl that Wilde had in mind: the Sibyl at Cumae, who, in Petronius’ scurrilous Roman novel Satyricon (which Wilde would surely have known) and in other stories, was destined to live forever but to age and wither away. She had eternal life, but not eternal youth. Dorian’s own eternal youth comes at a horrible cost: without a soul, all he can do is go in pursuit of new sensations, forever chasing desire yet never attaining true fulfilment.

It will, in the end, destroy him: in lashing out and trying to destroy the truth that stares back at him from his portrait, much as he had destroyed the artist who held up a mirror to his corrupt self, Dorian Gray destroys himself. In the last analysis, as he and his portrait do not exist separately from each other, he must live with himself – and with his conscience – or must die in his vain attempt to close his eyes to who he has really become.

About Oscar Wilde

The life of the Irish novelist, poet, essayist, and playwright Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) is as famous as – perhaps even more famous than – his work. But in a career spanning some twenty years, Wilde created a body of work which continues to be read an enjoyed by people around the world: a novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray ; short stories and fairy tales such as ‘ The Happy Prince ’ and ‘ The Selfish Giant ’; poems including The Ballad of Reading Gaol ; and essay-dialogues which were witty revivals of the Platonic philosophical dialogue.

But above all, it is Wilde’s plays that he continues to be known for, and these include witty drawing-room comedies such as Lady Windermere’s Fan , A Woman of No Importance , and The Importance of Being Earnest , as well as a Biblical drama, Salome (which was banned from performance in the UK and had to be staged abroad). Wilde is also often remembered for his witty quips and paradoxes and his conversational one-liners, which are legion.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

5 thoughts on “A Summary and Analysis of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray”

‘Genius lasts longer than beauty’ – a very appropriate quote from Chapter 1

- Pingback: A Summary and Analysis of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray - Teresa Edmond-Sargeant

- Pingback: 10 of the Best Works by Oscar Wilde – Interesting Literature

The “yellow book”, referred to is probably Huysmans’s A Rebours, which was sold in a yellow jacket. It is not the Yellow Book quarterly (a publication featuring poetry, prose and illustrations from followers of the Aesthetic movement), which came later, and which probably took its title from the reference in Wilde’s novel.

- Pingback: A Summary and Analysis of Oscar Wilde’s ‘The Happy Prince’ – Interesting Literature

Comments are closed.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Frappes and Fiction

Books & Philosophy

Book Review: The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

This book has some of the most long-winded and sesquipedalian (I wanted to use that word so badly) prose I’ve ever read, but I somehow managed to finish it in one afternoon, glued to my Kindle the entire time.

(By the way, anyone else love the irony of the word sesquipedalian? It has to be one of my favorite words for that reason)

About the Book

Title: The Picture of Dorian Gray

Author: Oscar Wilde

Published: 1890

Genre: classics, Gothic/horror

Rating: 5/5 stars

(This book is in the public domain, so you bet I’m going to drop a million quotes in the review)

Book Review

“Sin is a thing that writes itself across a man’s face. It cannot be concealed.”

The Picture of Dorian Gray opens with the introduction of an artist named Basil Howard and his fascination with a young man named… Dorian Gray , whom we are told is very, very (very, very, very) beautiful. (It’s implied that Basil has romantic feelings for Dorian, which is actually what made the book controversial when it was published in 1890.)

When Dorian comes to Basil’s studio to get his portrait painted, he meets Basil’s cynical and slightly evil friend, Lord Henry, who enjoys saying oh-so-clever and casually callous one-liners during every lull in conversation.

“Being natural is simply a pose, and the most irritating pose I know.” – Lord Henry, whom I loved despite the fact that he is the villain…

Lord Henry manages to freak Dorian out about getting old and losing all his beauty, tricking him into unwittingly selling his soul (?) for eternal beauty.

That’s right: Dorian will never grow old; instead, his portrait will bear all of the weight of his life choices. Dorian doesn’t realize this at first, but as he falls deeper into debauchery at the encouragement of Lord Henry, the portrait gradually grows more and more hideous, hidden in Dorian’s attic where no one will ever find it….

“There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.”

I’d been looking forward to reading this book for while. I had seen it on so many lists of “accessible” classics and best-books-of-all-time, so one day I finally went and downloaded it from Project Gutenberg to give it a try myself.

First of all, though it was slightly more on the long-winded side, the writing was great. While there were one or two places where I was almost tempted to skim through the long descriptions of Dorian’s opulent lifestyle and whatever the walls looked like, I couldn’t bring myself to because the language was just so immersive and quite frankly addictive.

There were also a surprising number of funny one-liners (said by Lord Henry, of course). Speaking of Lord Henry, although he is the obvious antagonist, Wilde writes him in such a way that the audience can disturbingly see themselves in him and almost sympathize with him anyway, an aspect of the book that really stuck with me .

One thing that took me out of the story were certain really dramatic and unrealistic situations that were just too over-the-top for me to take seriously. (the whole thing with Dorian’s fanatical crush was… super melodramatic, but that is characteristic of Gothic literature. I think. I’m not going to pretend to be an expert on artistic movements.)

Let’s talk some more about the plot, though. The symbolism of the titular “picture of Dorian Gray” was a fascinating basis for a story, and the book keeps up its momentum through an intense feeling of this-is-not-going-to-end-well. You’re compelled to keep reading, even though it’s obvious that the story isn’t going anywhere good.

The ending was fitting, albeit kind of sudden, but I’m not going to discuss it because this is, after all, a spoiler-free review.

Recommendation:

I would recommend this book to anyone looking to read more classics and anyone in the mood for a contemplative and spooky-ish book.

Read-alikes:

I’m adding a new section to my reviews where I mention other books that remind me of the book I’m reviewing! For this one, I’m going to say it reminded me a lot of Frankenstein by Mary Shelley , and the premise is sort of like The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue by V.E. Schwab , which I haven’t read yet (so don’t hold me to that)

That’s it for today’s review! Have you read The Picture of Dorian Gray ? Do you agree with my points?

Type your email…

Add me on Goodreads!

Share this:

16 comments on “book review: the picture of dorian gray by oscar wilde”.

Gaaah I really need to read this! It sounds incredible, great review! also I for one love the word sesquipedalian

Like Liked by 1 person

thanks! it is a great word

I’ve always thought of classics as hard to read, but for some reason I find myself enjoying them (and that sense of satisfaction once you finish it is incomparable.) Sesquipedalian! I once read an article in the newspaper about Sesquipedalian loquaciousness and I reckon that’s the most new words I’ve learnt at once.

If it’s like The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue by V.E. Schwab I should probably read it soon as I’ve heard that being compared to so many of my favourite books. Also so many characters in books set in the early 20th-century hint at Wilde’s work and read his books so it’s time I pick up one!

Also, those quotes are so lovely! This review totally made me want to read it 🙂 Great job!

Thank you! I’m so glad my review encouraged you to read it. I hope you enjoy it!

I remember reading this book in high school and hating it for some reason. I probably need to red it again now that I’m older. But I love the Dorian character in movies, like in the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen!

You should read it again!

great review! i’ve wanted to read this for so long 😅

You should give it a try!

Wonderful review, Emily! I have not read this book, but now I am quite curious about it. 🙂

Definitely pick it up!

Always one of my favorite books.

- Pingback: You Need To Read These Books!| My 5-Star Favorites of the Year So Far – Frappes and Fiction

- Pingback: May 2021 Wrap-up: Premature Senioritis, Getting Vaccinated and Resetting My Life – Frappes and Fiction

it’s not an easy task you undertake and you seem to be doing it with consistency and commitment. special thanks coming your way to let you know that you’re doing a great service to the tireless authors, writers, readers and the entire fraternity. stick with it. blessings. will be following your posts and hope you follow mine and share a thought sometime.

- Pingback: Rating All 100+ Books I Read in 2021 – Frappes and Fiction

- Pingback: Reflecting on 2021: Blogging Milestones, Reading Stats, and New Year’s Resolutions | 2021 Mega-Wrap-up – Frappes and Fiction

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Editing & Marketing Services

The Picture of Dorian Gray: Book Review

The Picture of Dorian Gray

Author : Oscar Wilde. Published : 1890, Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine. Our Edition : 2015, Alma . Length : 288 Pages. Genre(s) : Classic, Gothic, Thriller. Rating : 5/5. Links : Goodreads | Amazon | Book Depository | Audible

I don’t want to be at the mercy of my emotions. I want to use them, to enjoy them, and to dominate them.

Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray tells the story of Dorian, a young man who is corrupted by his narcissistic society. Once an innocent adolescent, he becomes an obsessive Machiavel who will do whatever it takes to hold onto his youth. He achieves this with the help of Basil, an artist who produces a detailed portrait of Dorian. Upon looking at the portrait, Dorian realises that, although he is young in the painting, he will not stay this way: over time, he will wither and die. In his misery, he cries out, asking the open air whether the portrait c ould age in his place.

His prayer is granted: as the years pass, Dorian grows older, yet no signs of age appear on his body. No lines gather around his features, and his eyes shine just as brightly as they did on the day that Basil painted his portrait. Meanwhile, up in Dorian’s attic, Basil’s portrait sits hidden away. It is the same picture with the same frame, yet its subject has changed. Instead of depicting a glowing youth, it displays a withered, decrepit man. It bears every pain Dorian inflicts on himself, a fact that Dorian takes full advantage of. He follows a path of sin, drinking to excess, spending time in opium dens, and abusing those around him. Yet despite these actions, his face remains pure and youthful. No one blames Dorian for his sins, for how could such a beautiful, innocent-seeming youth commit such atrocities?

Wilde’s novel weaves a dramatic tale of identity, sacrifice, and cruelty. As it considers the underlying principles of human nature, it uncovers our narcissistic habits, exposing our own superficiality, whilst weaving a fantasy tale that aligns itself with gothic imaginative works such as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Bram Stoker’s Dracula .

Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray is not only a story about art: it concerns individuality, materialism, conscience, and pressures regarding a person’s appearance. At least one of these issues is still a big concern today, which is perhaps what makes this novel so interesting. Dorian’s fears about growing older are shared by many of us, including a number of poets . Yet unlike the rest of us, Dorian discovers a way of combating age. Whilst his portrait bears the signs of his crimes, Dorian walks around unscathed, able to beguile, trick, and murder without any hint of cruelty showing on his face.

Of course, many of the themes in this book are based on superficial constructs. There are characters who naturally assume that, because Dorian doesn’t look cruel, he is incapable of cruel actions. Nowadays, such logic can be easily dismissed as foolish, yet it is very real in The Picture of Dorian Gray. Wilde reveals how important our appearances can be to us; Dorian is genuinely terrified of losing his youthful demeanour, even though growing older is a purely superficial transformation, and one that is natural for all of us. The materialism that we associate with modern society fully emerged in the Victorian period; Wilde lived during a time when material possessions passed easily from one hand to another, and The Picture of Dorian Gray comments on this burgeoning commodity culture: Dorian sees his youth as a precious commodity, and although he possesses an assortment of books, jewels, and fine clothes, it is his appearance that he values the most.

Although this novel considers a number of complex themes and ideas, its true beauty arguably does not lie with its content. The story is incredibly dramatic, and is sure to satisfy any reader: there are memorable characters, fascinating plot twists, and an element of the supernatural that adds a layer of mystery to the novel. Yet Wilde’s greatest skill arguably lies with his style of writing. This book is filled with a descriptive language that surpasses all expectations. When you read it, you may just wonder whether you are reading poetry, rather than prose. Wilde has a powerful command over the English language and it is thoroughly reflected in The Picture of Dorian Gray .

This is a novel that will really make you think. Its characters are so boldly imprinted on its pages that they become easy to picture. It raises a lot of questions, but rarely answers them. This results in a sense of mystery that hangs over the narrative, causing readers to question what Wilde really believed, as well as what he intended for his novel. Yet one of Wilde’s core principles is that a books do not have to mean anything. At the beginning of the book, he considers how art can exist for art’s sake. It does not have to mean anything and it does not have to question contemporary ideals. As a result, The Picture of Dorian may not have a true meaning; exists as it is: as an incredible work of literature.

Fever Dream: Book Review

50 Synonyms for "Walk"

Jules_Writes

I’ve never read it but always meant too, maybe one day…

Emily | Literary Edits

Thanks for reading our review, Jules. The Picture of Dorian Gray is certainly worth reading if you can find the time for it; we thoroughly recommend it!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Book Review: The Picture of Dorian Gray

I read this novel on a whim - I had never read any of Wilde before and did not know too much about him as an author apart from the fact he was put on trial and imprisoned during his life. The Picture of Dorian Gray was thoroughly surprising and unexpected. Dorian Gray, at the beginning of the novel, is perceived by Basil Hallward as an individual worth obsessing over, he is infatuated with him and without knowing Dorian yet, the reader is too. But then the reader is introduced to him physically and I realized he isn't all that. He's almost pompous but somehow clever and he's beautiful. Both Basil and his friend Lord Henry Wotton are influenced to see him more positively by that but I think the fact that Dorian is not tangible to the reader allows us to see him for who he truely is. According to Lord Henry, beauty is worth more than genius is, depicting which friend he prefers over the other. I wanted to sympathize with Basil because he was more sensitive than the others and I felt pity for him as I realized he was not a character anyone particularly cared immensely for. I preferred Basil over both Henry and Dorian because Henry's beliefs appeared rather traditionalist and were more controversial than common and the fact that Dorian was supposed to be a character without any fault was already a warning for me. Honestly, from the title, I did not know what direction the novel was going in from any point during the reading. To clear a few things up, Basil is an artist who paints a portrait of Dorian because he appreciates him in a more aesthetic manner than others who enjoy his company but the portrait appears to change into something more demonic as time goes on symbolizing how awful Dorian was becoming as a person. I mean, I needed to stop reading for a few minutes because I could not believe how little Dorian cared for others but I will admit that the absurdity of it all was entertaining. There is a lot of murder in this book which definitely makes the novel more interesting but then I guess I should also mention not get too attached to some characters. Reviewer Grade: 11

critical book reviews

- Oscar Wilde

- Apr 8, 2020

The Picture of Dorian Gray - critical review

I watched a series of lectures about the Supernatural and the evolution of the supernatural, and one key aspect of the course was the 'uncanny' and how it is explored. The idea of the Uncanny was developed by Sigmund Freud in his short essay in 1919. One example that he used in literature that would produce the 'uncanny' feeling was the use of 'the double.' After being really interested in the 'double' in Jane Eyre through the character of Bertha and Jane, I wanted to explore this further. Since particular reference was made to Oscar Wilde's only novel, 'the Picture of Dorian Gray', I thought I would start by reading this. After reading the novel, I watched a series of lectures on the novel and read an article about the characters in the book. The philosophical novel touches on themes of identity, art and its influence, morality and ethics, nature, religion and beauty.

Something I found interesting in the novel was the portrayal of the importance of art, and incorporating aestheticism and the ideas of the Decedent movement. Aestheticism was the rejection of Anglicanism and its moral purpose of art. Instead, it was fascinated by the imagination, individual and personality. It was enveloped by a group of writers, artist and critics and was later called the decedent movement (about 1860-1890s.) It was a series of rebellions against conventional art and the attitudes to it, believing that art shouldn't be a tool for social education or influence morality, but instead have no responsibilities apart from its purpose of being beautiful. 'The Picture of Dorian Gray', then, is ultimately a production of Aestheticism through its focus on both the painting and the mysterious 'yellow book.' It also references theatre, through the character of Sybil Vane, and throughout the entire novel is centred around arts and the beauty of it. Wilde was known as "the high priest of the decedents", and therefore agreed with the movement profoundly, and what struck me in the novel was this movement was carried throughout the book as a warning of the result of art being a gateway to influence and education, the opposite of what the decedent movement was preaching. Dorian's life, ultimately, gets destroyed by different forms of Art. Sybil Vane, who is a character made of up of a collection of Shakespearean characters, is a motif for the theatre and performance. It is portrayed that she is "never" Sybil Vane, and Dorian can't describe her character, only that of the different parts she performs in theatre. When Sybil falls in love with Dorian, she can't act her true love on stage, and this ruins Dorian's affection for her, and leads to their destruction of their relationship and ultimately, Sybil's death. When Sybil dies, he fictionalises it: "if I read all this in a book, Harry, I think I would have wept over it", which further creates her to be a character rather than an individual in reality. Therefore, the love that Dorian has for Sybil is destroyed due to the influence of art, since when it is taken away and the reality of Sybil is revealed, Dorian turns against it. Wilde portrays that if this aspect of art influences an individual too much, it ruins the vision of reality. Dorian falls in love with the characters that Sybil plays, instead of Sybil herself. Furthermore, Dorian Gray is also corrupted by the piece of literature he is given by Lord Henry: the mysterious 'yellow book': 'A rebours', or 'Against Nature' by Joris-Karl Huysman, an important piece of fiction of the Decadent movement in France, published in 1884, which portrayed the superiority of human creativity over logic and the natural world. This book is portrayed to 'poison' Dorian Gray. Furthermore, the painting itself, the most dominate source of art in the book, has corrupting influence over Dorian, and in the end, destroys him. Therefore, the novel seems a cautionary tale in light of the view that art should have a moral responsibility, which the decedent movement were trying to crush. Wilde in his preface of the book said that that the only purpose of art is to have no purpose, except for being beautiful and to entertain our 'intense admiration' and he presents this idea through Lord Henry's statement that "art has no influence upon action". Therefore, the fact the novel shows the opposite of this, in which art has influence over every action, and this leads to destruction, means it becomes a cautionary tale for this idea and the danger of corruption through the influence of art.

Another criticism of society which Wilde included in the novel was the superficial view of beauty. The whole novel is centred around the fact that Dorian would do anything for beauty, including selling his soul for it. This vanity carries on throughout the novel, in which he is transfixed by the painting, even when it is ugly and sinful. His obsession with his appearance links to Ovid's metamorphosis, in which Narcissus falls in love with his reflection, and this leads to his death. This myth is echoed in 'The Picture of Dorian Gray', through Dorian becoming so encapsulated by his image that it leads to him destroying it. The dark vanity that is portrayed in Dorian is shown when the narrator tells us "he himself would stand, with a mirror, in front of the portrait that Basil Hallward had painted of him ... He grew more and more enamoured of his own beauty, more and more interested in the corruption of his soul." Therefore, Wilde takes Narcissus' sense of vanity even further, through Dorian not only being obsessed with the beauty of his appearance, but also the image of his soul and its corruption. This self-obsession is so strong that he cannot prevent it, however hard he tries. The physical placing of the painting in the attic, covered with a blanket, portrays his conscious motive of trying to hide and forget the image, however, the fact he often goes up and looks at it shows his unbreakable obsession with himself, which only increases as his sin becomes more corrupted and his beauty remains immutable. This superficial nature of humanity is also portrayed through other characters, in which assumptions are made about Dorian in which the reader knows are not correct. The irony in the title portrays the difference in interpretations in his character: since the 'picture' that the characters see of his face lead them to misleading conclusions, and the 'picture' that we see through the narrative voice and painting show his true identity. Lady Narborough notes that there is little distinction between appearance and ethics, staying that "you are made to be good - you look so good." Furthermore, Henry is certain on his assumptions of Dorian as he notes that Dorian is a "perfect type", who the world "has always worshipped", confirming "people like you don't commit crimes." Therefore, the fact that peoples assumptions about Dorian are so incorrect conveys the reliance they have on appearance, portraying a superficial world. The only other character that is aware of Dorian's true nature is the reader, through the omniscient narrator's portrayal of Dorian and his true conscience. Therefore, this portrays a disconnection that beauty creates between people: in which appearances create relationships that are completely false and grounded on incorrect hypotheses, and the only person that truly knows Dorian, since we are the only ones to get past the appearance of him, is the reader.

Furthermore, the fact that Dorian contains such juxtaposing natures: his material appearance and his soul displayed on the painting, creates the question of who is more of a person. This conveyed the ideal of dualism, in which the soul and the material body are two natures that make up the whole of a person: therefore each state of Dorian's being: his beautiful appearance and his corrupted soul are only half of his identity. Not only does his attraction to the painting, despite various conscious efforts to hide it from itself, show his vanity and hedonism, but it also portrays that he can't be separated from his soul despite the vision of its corruption and ugliness. This idea uses the Victorian fascination of doubles and the idea of being a stranger to oneself, but Wilde takes it further in that Dorian finds the 'other' side of his nature fascinating and enthralling. The painting is both a double of Dorian and also a double of Basel's original painting. The painting is a visual mirror of the other half of Dorian, in which he can't destroy or escape. The fact, in the end, he does try to destroy it, and ends up destroying himself, portrays that the soul is inescapable from the material body. The fact the painting returns to the beautiful state that Dorian had encapsulated, and the description of Dorian's physicality incorporating the vulgarity of the painting, shows that the soul can live without the body, but the body can't live without the soul. Therefore, the fact the Wilde Gothicises the painting, in which it becomes a character in the novel itself, is a motif for the immortal soul that is inescapable from the body.

Moreover, the use the 'double' is further incorporated in the novel through the two characters of Henry and Basel showing two mutually exclusive attitudes to life, in which Dorian struggles over becoming. Henry is a nihilist and has a pessimistic view on human nature and nature itself. He argues that we have little control over higher forces, in which "good resolutions are useless attempts to interfere with scientific laws. Their result is absolutely nil." He detaches himself from life, incorporating Walter Paitors study of arguing that to become a spectator of one's own life is to escape the suffering of one's life. He believes that intellectual curiosity is the only thing that that is neither futile or destructive and is superior to all else (he "would sacrifice anybody for the sake of an epigram".) In this view of an amoral universe, he incorporates an ethical egoism and uses the ethical system of utilitarianism: in which he pursues pleasure and avoids pain. He bases this on the assumption that the quest for pleasure is natural, also incorporating Bentham's utilitarian view that "nature is governed by two sovereign masters: pain and pleasure." He takes this further in creating sufferings of life into pleasures, creating the idea that reality can not be changed but can be improved in one's head, arguing that "names are everything." Therefore, Henry's cynicism enables him to become a spectator to life, in which he does not get involved with suffering and makes all decisions on the motive of personal pleasure. Some people have argued that Henry sounds like a spokesman for Wilde, however the fact his influence on Dorian is disastrous and his ignorance on Dorian's true nature shows a disconnection with personalism and a criticism on his hedonism. Basel displays the opposite of Henry in his attitude to life and identity. He believes in moral order and justice, and therefore one should live for sympathy. He believes that sin "cannot be concealed" and that God is the only being that can see the soul. He directly criticises the philosophy of Henry when he argues "if one lives for one's self", "one pays a terrible price for doing so." He wants to create art that portrays the union of feeling and form and wants Dorian to use his "wonderful influence ... For good, not for evil." Therefore, Basel portrays a foil to the hedonistic Henry.

Dorian, then, becomes the 'middle man', in which he is fought over by the two ideals. Both characters try to force their philosophy on him and in the end, Dorian's failure is his inability to reconcile the two. In many ways, he tries to use Henry's philosophy and attitude towards life. He decides there is no justice "in the common world of fact the wicked were not punished, nor the good rewarded" and wants to pursue control over his emotions: "I don't want to be at the mercy of my emotions .. I want to dominate them." This control over his reaction to events is also shown when he urges to Basel "if one doesn't talk about a thing, it never happened" and that "the secret of the whole thing is not to realize the situation." He wants, and does at times achieve, the idea of becoming a spectator to one's life: in which he feels Basel's death is compared to the "terrible beauty of a Greek tragedy, a tragedy in which I took a great part, but by which I have not been wounded." Often, the character of Dorian seems to dominate his emotions and detach himself from suffering. However, it is revealed that he cannot fully incorporate this lifestyle and destroy the nature of his conscience through his inability to suppress Basel's attitudes. He conveys that cannot live his life just pursuing pleasures, as "each of us has heaven and hell in him", therefore can't repress the natural form of his being. After rejecting any emotion, remorse or sadness towards the death of Sybil, he later reveals his regret and guilt and feels it is his "duty" to go back to her and "do what is right." Particularly, the word "duty" portrays he does have a sense of belief in eternal justice. The suppression of what Basel represents is further confirmed through the murder of Basel and the destruction of the portrait itself which symbolises the "hell" side of him in his nature. Overall, he can not deny the demands of his superego as well as being unable to repress his passions. He can't combine the two natures of the 19th-century morality in terms of hedonism and stoicism, instinct and consciousness. He is unable to combine the two parts of him to become fully human and confront both his body and soul. Houston A Baker confronted this in "the critic as Artist" through observing that Dorian did not fail through not choosing between the two ideals: conscious and instinct, but he fails to merge them: he cannot combine them and live successfully. He ultimately fails to incorporate his two opposing potential selves that Basel and Henry incorporate.

Something that is difficult to understand in the novel is the moral meaning behind it. There is a lack of justice in the novel, through all characters losing their lives apart from the hedonistic, individualistic and unsympathetic Henry. The moral order that Basel and Sybil preach does not seem to exist in the world of this novel: good and evil actions make no difference to a higher sense of reward and punishment. The narrator has no opinion on the matter, but rather is an omniscient observer of all the characters and their emotions and situations. The fact that the novel is far from the real world, shown from the beginning through all the flowers of different seasons blooming at the same time, portrays that it is a unique portrayal of reality, and so Henry survival in this novel may not be a representation of his survival (symbolising his achievement) in the real world. However, it does have a pessimistic overall tone that justice is not achieved. Overall, however, this may be a moral warning of influence, including the messages of aestheticism. All characters, apart from Henry, are influenced by another thing or being: Sybil by Dorian, Basel by his own painting and Dorian and Dorian by Henry, Basel and art. Henry's survival confirms Henry's view of influence being destructive: "all influence is immoral" since it is to "give him one's own soul", which he goes on to argue the result on the one who was influenced: "his virtues are not real to him. His sins, if there are such as sins, are borrowed. He becomes an echo of someone else's music, an actor of a part that has not written for him." Therefore, the fact that Dorian has been influenced by both Basel and Henry, as well as art, leads him to become a faulty version of the combination of all the different ideals he becomes exposed to, which cannot be actualised in life and therefore leads to his downfall.

Overall, the novel takes on ideas of aestheticism and the Decedent movement which Wilde wanted to portray. The result of influence as destructive is a prominent message of the novel, and overall creates the novel to have such a tragic ending. The juxtaposition of Henry and Basel create a 'double', which Dorian struggles over: and ultimately fails to combine the two opposite philosophies that the two characters convey. Wilde stated that "it (the book) contains much of me in it. Basil Hallward is what I think I am: Lord Henry what the world thinks me: Dorian what I would like to be - in other ages, perhaps", so in a sense, not only do Basel and Henry create the character of Dorian, but the three main Protagonists are also parts of Wilde himself, each conveying different moral messages which he wants to portray.

- Digital Media Help

- Learn at Home | Homework Center

- Meeting and Study Rooms

- Wifi & Wireless Printing

- Log In / Register

- My Library Dashboard

- My Borrowing

- Checked Out

- Borrowing History

- ILL Requests

- My Collections

- For Later Shelf

- Completed Shelf

- In Progress Shelf

- My Suggestions

- My Settings

- Pima County Public Library Blogs

- PimaLib_Teens

Teen book review: The Picture of Dorian Gray

This review was submitted by one of our talented teen virtual volunteers .

Nowadays classics are seen as tired and overused. No one really wants to hear another story about a wealthy white man in the 1800s. However, there is something important to learn from the classics; that’s deeper than the skin color or gender of the character. It’s the plot, the theme. Its why Oscar Wilde and other writers like him in that era wrote their books the way they did.

The Picture of Dorian Gray follows the life of a young boy in the 1890s on the path to insanity.

Basil Hallward, Dorian’s first genuine friend, creates a painting that captivates his soul; while Lord Henry, the man for all the faults of Dorian, enraptures his mind. Whether it be dinner parties, nights at the opera, or life-changing moments at the club, everyone became entangled with Dorian’s beauty. Even in old age, even though he might’ve been the cruelest man alive, at least to him. They still could not take their eyes off of the boy whose face had never touched time.

The beginning of the book starts out with a conversation between Basil Hallward and Lord Henry enjoying a pleasant afternoon in Basil’s Garden. As, the story progresses we learn the complicated yet amusing friendship between the two. Basil, a simplistic painter, looking for the next person to change his life; his art, and Lord Henry; a man that came from wealth who spends his time gorging on all the knowledge passed down from his previous life. Lord Henry stated, “But beauty, real beauty, ends where an intellectual expression begins. Intellect is itself a mode of exaggeration and destroys the harmony of any face.”

Progressing into the book Dorian gets introduced through Basil’s obsession with him, he informs Lord Henry that the young man will come over for another one of his paintings. He warned him not to project onto his innocent and beautiful soul. “Dorian Gray is my dearest friend–Don’t take away from me the one person who gives to my art whatever charm it possesses: my life as an artist depends on him.”, spoke Basil.

This book is an eye-opening journey of how innocence can all pass up in a moment, how time ruins everything beautiful and how wrinkles behind a smile can drive someone’s life. Therefore the picture of Dorian gray shows an altruistic point of view behind friendship, and even behind love. “Men who talked grossly became silent when Dorian Gray entered the room. There was something in the purity of his face that rebuked them. His mere presence seemed to recall to them the memory of innocence that they had tarnished.”, Wilde wrote.

The Picture of Dorian Gray was definitely one of the more enjoyable classics. Usually, this book is seen as a burden because it is attached with homework questions. But as someone who read it with free will, it is pretty enjoyable. Oscar Wilde always had a knack for making characters in a book seem all too real, it’s like you personally know them. Like other great writers in his time, he always knew how to build a world in your imagination. I have never seen a writing style like Wilde and that could be why we study his books the way we do.

Now rating The Picture of Dorian Gray is for sure difficult to do, as it is so controversial. However, on a rating scale of one to five, I would give it a 4.0 to 4.5. Mainly because of the amount of true understanding and effort it takes to read this book. Writing styles are not the same as they used to be, so as someone who isn’t used to a writing style like that, as most of us aren’t. It makes it difficult to understand the book and truly enjoy it. However, the suspense and the world Wilde builds takes over you, which allows you to overlook the complicated language. If you end up reading this book and are only a few chapters in regretting your decision, do stick with it. This book revolutionized my idea of mystery and thrill.

The Picture of Dorian Gray

More by PimaLib_Teens

Teen book review: School's First Day of School

Stories from the digital storytelling bootcamp.

- Health & Wellness

Join the Digital Storytelling Summer Camp!

- Digital Media

- Parents & Families

Discover New Posts

Bringing the aloha spirit to tucson, what do you want to do for a living, on therapy - a q&a with dr. andy bernstein.

Powered by BiblioCommons.

BiblioWeb: webapp04 Version 4.19.0 Last updated 2024/05/07 09:43

- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to 500)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- Investing Books

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Ages Baby-2

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2023

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2023

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2023

- Best Kids' Books of 2023

- Political Novels

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

The Best Fiction Books

The picture of dorian gray, by oscar wilde, recommendations from our site.

“If you wish to participate in the novel, you have to appreciate it in the way that Dorian appreciates cabinets, carpets, tapestries and jewels. Is beauty deceptive or can beauty be a moral guide? Does the novel suggest that if you judge by appearances you’ll be led astray, like the people who think that Dorian can’t be guilty of the crimes that he has committed because he is beautiful? Or does the ending of the novel, in which Dorian magically becomes ugly as he is ‘punished’ for his sins, affirm the link between morality and beauty? You can offer equally convincing readings either way round, but only by discarding half the evidence in the novel. So, it’s a novel that engages with beauty, aesthetics and the idea of what an aesthetic life would be, but it offers no answers.” Read more...

The best books on Oscar Wilde

Sos Eltis , Literary Scholar

“ The Picture of Dorian Gray is now a part of the canon that no one would admit to not having read. Most of us have read it and delighted in its witticisms. It’s hard to imagine, but when Dorian Gray was first published, the book was not well received at all. It was totally panned. It was held against him as being an example of an effete character. It was being serialised by Lippincott’s Magazine , and the serialisation of the novel stopped when it became too inflammatory. One of the reasons why I wanted to recommend this book is that it is an example of literature being used as evidence itself. Most of us know the bones of the situation of Oscar Wilde being put on trial in 1895 – the father of his (homosexual) lover became inflamed and found all kinds of characters to use against him (in court). During his trial, Oscar Wilde had to answer for the attitudes expressed by the characters in The Picture of Dorian Gray .” Read more...

The best books on Sex and Society

Eric Berkowitz , Journalist

Other books by Oscar Wilde

De profundis by oscar wilde, the complete short stories by oscar wilde, the soul of man under socialism by oscar wilde, the happy prince by oscar wilde, the importance of being earnest and other plays by oscar wilde, our most recommended books, middlemarch by george eliot, war and peace by leo tolstoy, jane eyre by charlotte brontë, beloved by toni morrison, the arabian nights or tales of 1001 nights, the talented mr ripley by patricia highsmith.

Support Five Books

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce, please support us by donating a small amount .

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

- Featured Essay The Love of God An essay by Sam Storms Read Now

- Faithfulness of God

- Saving Grace

- Adoption by God

Most Popular

- Gender Identity

- Trusting God

- The Holiness of God

- See All Essays

- Best Commentaries

- Featured Essay Resurrection of Jesus An essay by Benjamin Shaw Read Now

- Death of Christ

- Resurrection of Jesus

- Church and State

- Sovereignty of God

- Faith and Works

- The Carson Center

- The Keller Center

- New City Catechism

- Publications

- Read the Bible

- TGC Pastors

U.S. Edition

- Arts & Culture

- Bible & Theology

- Christian Living

- Current Events

- Faith & Work

- As In Heaven

- Gospelbound

- Post-Christianity?

- TGC Podcast

- You're Not Crazy

- Churches Planting Churches

- Help Me Teach The Bible

- Word Of The Week

- Upcoming Events

- Past Conference Media

- Foundation Documents

- Regional Chapters

- Church Directory

- Global Resourcing

- Donate to TGC

To All The World

The world is a confusing place right now. We believe that faithful proclamation of the gospel is what our hostile and disoriented world needs. Do you believe that too? Help TGC bring biblical wisdom to the confusing issues across the world by making a gift to our international work.

Book Review: The Picture of Dorian Gray

More by trevin.

Warning – Spoilers Follow

Here’s the gist of the book. Dorian Gray is a young man whose physical appearance is handsome and innocent. An aspiring artist paints a beautiful portrait of Dorian. Dorian wishes that he always look like his youthful appearance in the portrait. The wish comes true. Dorian remains the same – youthful and charming, but the portrait begins to transform itself into the image of his soul.

When Dorian embraces a life of hedonism, he uses his good looks and charm to obtain whatever he desires in life. His insensitivity drives a friend to suicide. The evil desires of his heart eventually cause him to murder a friend in cold blood. Over a period of twenty years, Dorian becomes a monster on the inside (reflected by the portrait of his soul) even as he remains youthful and innocent on the outside.

Oscar Wilde’s homosexuality is no secret, and the reader can easily discern certain homosexual overtones in the book (especially at the beginning). Perhaps Wilde’s subtle innuendoes of homosexuality have made his works so appealing to lovers of literature who tend to sympathize and approve of homosexual behavior.

Upon reading Dorian Gray , however, I could not help but notice how the lifestyle of hedonism is so implicitly condemned by the narrative’s outcome. If Dorian’s hedonism includes sexual relationships with men as well as with women (and Wilde does hint at this), then homosexuality comes under the same umbrella as the rest of Dorian’s sinful passions. One can hardly characterize The Picture of Dorian Gray as a pro-homosexual book.

Readers of this blog will find the picture of depravity in Dorian Gray to be intriguing. Throughout the story, Dorian, even in his hedonism, acts in a manner that forces the reader to desire justice and redemption. The book’s end emphasizes the need for punishment and retribution – pointing at death as the wages of sin.

What does the life of unbridled hedonism look like? What does it do to the soul? What happens to the human being who seeks to fulfill his every passion and desire? How does sin affect us physically? Do we age because we sin? These and more are the questions that Oscar Wilde raises in The Picture of Dorian Gray .

written by Trevin Wax © 2008 Kingdom People blog

Trevin Wax is vice president of research and resource development at the North American Mission Board and a visiting professor at Cedarville University. A former missionary to Romania, Trevin is a regular columnist at The Gospel Coalition and has contributed to The Washington Post , Religion News Service , World , and Christianity Today . He has taught courses on mission and ministry at Wheaton College and has lectured on Christianity and culture at Oxford University. He is a founding editor of The Gospel Project, has served as publisher for the Christian Standard Bible, and is currently a fellow for The Keller Center for Cultural Apologetics. He is the author of multiple books, including The Thrill of Orthodoxy , The Multi-Directional Leader , Rethink Your Self , This Is Our Time , and Gospel Centered Teaching . His podcast is Reconstructing Faith . He and his wife, Corina, have three children. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook , or receive his columns via email .

A Sickness in Pursuing Health

Does the Pursuit of Godliness Lead to Self-Righteousness?

Defy the Decay Rate for Worship in the Church

Remember the 4 ‘Alls’ of the Great Commission

Is Your Church Countercultural?

Other Blogs

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

A Close Reading of the ‘Censored’ Passages of The Picture of Dorian Gray

"basil only likes dorian as a friend, we promise".

“There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book,” wrote Oscar Wilde in the preface to the 1891 edition of The Picture of Dorian Gray . “Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.”

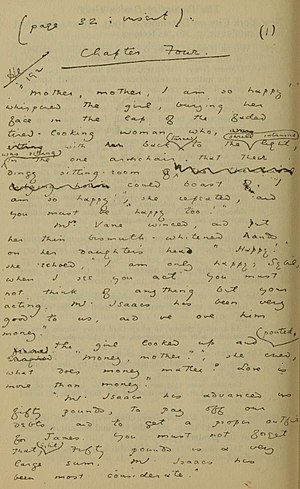

Of course, even as Wilde wrote these words, he knew that the critics did not agree with his assessment. In fact, the entire preface is a protest; a response to the backlash created by the original publication of his now-classic novel. By the time he wrote the above in 1891, The Picture of Dorian Gray had existed in three forms: the original typescript, commissioned by and submitted to J.M. Stoddart, the editor at Lippincott’s , the edited 1890 version published in the magazine (which had also published Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Sign of the Four , earlier that year), and the re-edited and expanded 1891 version, published by Ward, Lock and Company.

That sounds reasonable enough on its face—there can’t be many novelists whose manuscripts were accepted for publication without their editors making any changes, and as I’ve noted before , substantial edits can accompany the leap from magazine publication to book for a variety of reasons. But it seems that most of the changes between these three versions were attempts to make the book more “moral” (that is, less gay) and that they were at least partially enacted, like Wilde’s preface, as a response to the critics, and also as a bulwark against prosecution of Wilde for homosexuality, which was a real danger at the time.

According to Nicholas Frankel , editor of The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition :

When Wilde’s typescript of the novel arrived on [editor J.M.] Stoddart’s desk, he quickly determined that it contained “a number of things which an innocent woman would make an exception to,” as he explained to Craige Lippincott, while assuring his employer that The Picture of Dorian Gray would “not go into the Magazine unless it is proper that it shall.” He further guaranteed Lippincott that he would edit the novel to “make it acceptable to the most fastidious taste.”

The vast majority of Stoddart’s deletions were acts of censorship, bearing on sexual matters of both a homosexual and a heterosexual nature. Much of the material that Stoddart cut makes the homoerotic nature of Basil Hallward’s feelings for Dorian Gray more vivid and explicit than either of the two subsequent published versions, or else it accentuates elements of homosexuality in Dorian Gray’s own make-up. But some of Stoddart’s deletions bear on promiscuous or illicit heterosexuality too—Stoddart deleted references to Dorian’s female lovers as his “mistresses,” for instance—suggesting that Stoddart was worried about the novel’s influence on women as well as men. Stoddart also deleted many passages that smacked of decadence more generally.

Still, according to Nicholas Frankel’s introduction to his uncensored version, Stoddart only cut about 500 words from Wilde’s typescript. Editorial practices were rather different than they are today, and Wilde had no idea about any of the changes until he read his own, less-explicit, piece in the magazine. But it was quickly clear that Stoddart had not gone far enough. The book was roundly criticized and badly reviewed by the British press, who were not only disgusted but offended. In fact, Britain’s biggest bookseller went so far as to remove the offending issue from its bookstalls, citing the fact that Wilde’s story had “been characterized by the press as a filthy one.” Here’s one review , from London’s Daily Chronicle :