- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 10 August 2020

Non-classical presentation of vitamin D deficiency: a case report

- Mohanad Kamaleldin Mahmoud Ibrahim 1 &

- Mustafa Khidir Mustafa Elnimeiri 2

Journal of Medical Case Reports volume 14 , Article number: 126 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

7351 Accesses

3 Citations

22 Altmetric

Metrics details

Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin; vitamin D is essential to sustain health and it protects against osteoporosis. It is crucial to the human body’s physiology in terms of muscular movement and neurological signal transmission, and to the immune system in defense against invading pathogens.

Case presentation

This was a case of a 26-year-old Sudanese woman who presented with a 2-year history of anosmia, recurrent nasal polyps, back pain, and chronic fatigue. She was diagnosed as having a case of vitamin D deficiency and responded well to treatment.

There is an association between vitamin D deficiency and recurrent allergic nasal conditions.

Peer Review reports

Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin; it is naturally present in some foods and as dietary supplements. It is also produced endogenously through exposure to ultraviolet rays from sunlight. Vitamin D obtained from sun exposure, food, and supplements is biologically inert and must undergo two hydroxylations in the body for activation. The first occurs in the liver and produces 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D), also known as calcidiol. The second occurs in the kidney and forms the physiologically active 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D (1,25(OH) 2 D), also known as calcitriol [ 1 ].

Vitamin D is found in cells throughout the body; vitamin D is essential to sustain health and it protects against osteoporosis. It is crucial to the human body’s physiology in terms of muscular movement and neurological signal transmission, and to the immune system in defense against invading pathogens [ 2 ].

Although there are different methods and criteria for defining vitamin D levels, the criteria Holick proposed have been widely accepted. In this proposal, vitamin D deficiency is defined as blood level of less than 20 ng/ml; insufficiency of vitamin D is defined as blood levels ranging between 20 and 29.9 ng/ml and sufficiency if greater than or equal to 30 ng/ml [ 3 ]. About one billion people globally have vitamin D deficiency and 50% of the population has vitamin D insufficiency. The majority of affected people with vitamin D deficiency are the elderly, obese patients, nursing home residents, and hospitalized patients. Vitamin D deficiency arises from multiple causes including inadequate dietary intake and inadequate exposure to sunlight. Certain malabsorption syndromes such as celiac disease, short bowel syndrome, gastric bypass, some medications and cystic fibrosis may also lead to vitamin D deficiency [ 4 ].

Vitamin D deficiency is now more prevalent than ever and should be screened in high-risk populations. Many conflicting studies now show an association between vitamin D deficiency and cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and neuropsychiatric disorders [ 5 , 6 ].

This was a case of a 26-year-old Sudanese woman, married, who has a 3-year-old boy. This woman presented to our ear, nose, and throat (ENT) department complaining of anosmia for the past 2 years. She had a history of two functional endoscopic sinus surgeries (FESSs) for nasal polyps: the first one was 6 years ago and the second one was 3 years prior to presentation. She complained of being highly sensitive to different irritants including dust, weather change, perfumes, and pets.She also stated that she attended more than three different physicians due to generalized fatigue and getting tired easily after simple daily activity in addition to sleeping for more than 10 hours a day.She attended an orthopedic clinic for unspecified lower back pain that was not related to any type of trauma or physical activity; a lumbosacral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was done and revealed no abnormal findings.She mentioned that she is known to be anxious most of the time and aggressive toward simple reactions from her family members. She had no psychiatric history and was not using any medications.

She was not known to be diabetic or hypertensive or to have any chronic illnesses; she was not on any regular medication. She is a housewife of high socioeconomic status; she is well educated, graduated from dental school with a bachelor’s degree, but currently not employed. She has never consumed tobacco or alcohol; she practiced regular cardio exercises.On examination, she looked healthy, well, not pale or jaundiced. Her pulse rate was 74/minute and her blood pressure was 118/70. Her body mass index (BMI) was 26.8. All systems examinations were normal except for bilateral nasal polyps. Complete blood count (CBC), renal function test (REF), electrolyte, liver function test (LFT), thyroid function test (TFT), urine analysis (general urine test), antinuclear antibody (ANA), and rheumatoid factor (RF) were all normal. An imaging profile included lumbo-sacral MRI, a computed tomography (CT) scan of her sinuses, and electrocardiogram (ECG), which were normal except for bilateral nasal polyps and severe sinusitis that looked allergic to fungi in nature.She underwent FESS surgery to remove the polyps and clean out her sinuses; up to 6 weeks after surgery she used nasal steroids (mometasone furoate 0.005%) two times a day, but her symptoms regarding anosmia were not improved. MRI of her brain and a CT scan of her sinuses were done and both revealed normal features. A vitamin D deficiency was suggested and the laboratory results revealed a low vitamin D level of 7 ng/ml. Treatment with vitamin D supplement was prescribed at 50,000 international units (IU) weekly for 8 weeks and then 1000 IU maintenance dose daily, she was advised to take food rich in vitamin D and get exposed to sunlight for 20 minutes three times a week after the loading dose of supplement. She was at regular follow-up for 6 months; at rates of weekly for the first month, every 2 weeks for the second month, and monthly for the rest of the follow-up period. At each visit, she was assessed with clinical history and examination. It was noticed that the symptoms of tiredness, sleeping, anosmia, and back pain were dramatically improving during that period. At the 6 months follow-up, her blood level of vitamin D was normal, she described her condition as free from all symptoms, and she returned back to normal physical activity.

Discussion and conclusions

This was a non-classical case of vitamin D deficiency of a 26-year-old woman who presented with chronic anosmia and recurrent nasal polyps. She was diagnosed as having a case of vitamin D deficiency and responded well to vitamin D replacement therapy. This case correlated an association between decreased levels of vitamin D and recurrent nasal polyps that led in time to chronic anosmia as a result of chronic high sensitivity reactions triggered by our patient’s autoimmune system. The literature links chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) with asthma and allergic rhinitis, but the cellular and molecular mechanisms that contribute to the clinical symptoms are not fully understood. Sinonasal epithelial cell barrier defects, increased exposure to pathogenic and colonized bacteria, and dysregulation of the host immune system are all thought to play prominent roles in disease pathogenesis [ 7 ].

Despite all the previous surgical and medical interventions over the past 6 years, our patient’s condition did not improve and she still complained of anosmia. A study revealed that this patient was experiencing excessive allergic reactions that led to recurrent nasal polyps. It is well known that classical clinical effects of vitamin D deficiency are bones and musculoskeletal-related disorders, several lines of evidence demonstrate the effects of vitamin D on pro-inflammatory cytokines, regulatory T cells, and immune responses, with a conflicting interpretation of the effects of vitamin D on allergic diseases [ 8 ].

The working diagnosis was suggested in relation to some musculoskeletal symptoms and chronic fatigue especially when the imaging profile for her lower back and all routine investigations were normal. It has been suggested that clinicians should routinely test for hypovitaminosis D in patients with musculoskeletal symptoms, such as bone pain, myalgias, and generalized weakness which might be misdiagnosed as fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue [ 9 ]. The most common causes of anosmia were assessed as well and they were negative, these included sinonasal diseases, post infectious disorder, and post-traumatic disorder, and congenital defects and disorders caused by neurodegenerative disease [ 10 ].

Thus blood level for vitamin D was requested and the results were of low D level.

In the past history of the previous nasal polyps surgeries, our patient noted that there was no anosmia and her main complaints were classic complaints of sinusitis, including sneezing, nasal blockage and headache. Soon after surgery her symptoms improved except for the allergy-related symptoms, despite usage of inhaled steroids spray. She stated that, at the last time, the presentation was different since it was only anosmia, indicating that there was significant inflammation that affected the smell receptors around the olfactory epithelium. After the last nasal polyps and sinuses drainage surgery, the symptoms related to allergic reactions, including chronic sneezing, did not improve for up to 6 weeks and she was still suffering from hyposmia, although that was a fair postoperative period for recovery.

The symptoms of anosmia and sneezing, and other systematic symptoms, gradually started to improve after vitamin D supplements, indicating that the main reason behind her symptoms was vitamin D deficiency. She was followed up for up to 6 months after establishment of vitamin D supplements and at the last follow-up she had a normal sense of smell, and she was free from back pain, fatigue, and allergy-related symptoms.

This was a non-classical presentation as our patient was young and she did not have alkaline phosphatase, calcium, and phosphorus abnormalities [ 11 ] that are expected in cases of vitamin D deficiency.

This case revealed an association between decreased levels of vitamin D and recurrent nasal polyps that led to anosmia as a result of hypersensitive reactions produced by the body’s systems.

Although vitamin D deficiency is prevalent, measurement of serum 25(OH)D level is expensive, and universal screening is not supported. However, vitamin D testing may benefit those at risk for severe deficiency.

It is highly recommended to consider vitamin D deficiency among all patients with unspecified symptoms or in cases of non-diagnosed disorder regardless of the presenting complaint.

In conclusion, there is an association between vitamin D deficiency and recurrent allergic nasal conditions.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps

Computed tomography

Electrocardiogram

Ear, nose, and throat

Functional endoscopic sinus surgery

Body mass index

Complete blood count

Renal function test

Liver function test

Thyroid function test

Antinuclear antibody

Rheumatoid factor

International unit

National Institutes of Health. Vitamin D: fact sheet for health professionals. 2020. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/#en2 . Accessed 10 Apr 2020.

Google Scholar

National Institutes for Health (NIH). Vitamin D fact sheet for consumers. 2019. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-Consumer/ . Accessed 20 Dec 2019.

Kuriacose R, Olive KE. Vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency management. South Med J. 2014;107(2):66–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/SMJ.0000000000000051 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Sizar O, Khare S, Givler A. Vitamin D deficiency. Treasure Island: Stat Pearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532266/ . PMID: 30335299. Accessed 20 Dec 2019.

Wlliam B, Fatme A, Meis M. Targeted 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration measurements and vitamin D 3 supplementation can have important patient and public health benefits. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2020;74:366–76. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-020-0564-0 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Hanmin W, Weiwen C, Dongqing L, Xiaoe Y, Xiaode Z, Nancy O, et al. Vitamin D and chronic diseases. Aging Dis. 2017;8(3):346–53. https://doi.org/10.14336/AD.2016.1021 .

Article Google Scholar

Whitney W, Ropert P, Robert C. Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(04):565–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2016.04.012 .

Thacher TD, Clarke BL. Vitamin D insufficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(1):50–60. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0567 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kennel KA, Drake MT, Hurley DL. Vitamin D deficiency in adults: when to test and how to treat. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(8):752–8. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0138 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sanne B, Elbrich M, Duncan B, Antje W, Veronika S, Joel D, et al. Anosmia: a clinical review. Chem Senses. 2017;42(7):513–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjx025 .

Shikino K, Ikusaka M, Yamashita T. Vitamin D-deficient osteomalacia due to excessive self-restrictions for atopic dermatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2014; https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2014-204558 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Community Medicine and Epidemiology, Faculty of Medicine, Ibn Sina University, Khartoum, Sudan

Mohanad Kamaleldin Mahmoud Ibrahim

Preventive Medicine and Epidemiology, Alneelain University, Khartoum, Sudan

Mustafa Khidir Mustafa Elnimeiri

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MI analyzed and interpreted the findings of the case report and was the major contributor in writing the manuscript. ME reviewed the report and added valuable comments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mohanad Kamaleldin Mahmoud Ibrahim .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical approval was obtained from Albasar Institutional Review Board.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ibrahim, M.K.M., Elnimeiri, M.K.M. Non-classical presentation of vitamin D deficiency: a case report. J Med Case Reports 14 , 126 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-020-02454-1

Download citation

Received : 26 March 2020

Accepted : 08 July 2020

Published : 10 August 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-020-02454-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Vitamin D deficiency

- Nasal polyps

- Chronic fatigability

Journal of Medical Case Reports

ISSN: 1752-1947

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Summary of Recommendation

- USPSTF Assessment of Magnitude of Net Benefit

- Practice Considerations

- Update of Previous USPSTF Recommendation

- Supporting Evidence

- Research Needs and Gaps

- Recommendations of Others

- Article Information

See the Figure for a more detailed summary of the recommendations for clinicians. See the Practice Considerations section for additional information regarding the I statement. USPSTF indicates US Preventive Services Task Force.

USPSTF indicates US Preventive Services Task Force.

US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Grades and Levels of Evidence

- USPSTF Review: Screening for Vitamin D Deficiency in Adults JAMA US Preventive Services Task Force April 13, 2021 This systematic review to support the 2021 US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement on screening for vitamin D deficiency summarizes published evidence on the benefits and harms of screening and interventions for vitamin D deficiency in asymptomatic, community-dwelling adults. Leila C. Kahwati, MD, MPH; Erin LeBlanc, MD, MPH; Rachel Palmieri Weber, PhD; Kayla Giger, BS; Rachel Clark, BA; Kara Suvada, BS; Amy Guisinger, BS; Meera Viswanathan, PhD

- USPSTF 2021 Recommendations on Screening for Asymptomatic Vitamin D Deficiency in Adults JAMA Editorial April 13, 2021 Sherri-Ann M. Burnett-Bowie, MD, MPH; Anne R. Cappola, MD, ScM

- Patient Information: Screening for Vitamin D Deficiency in Adults JAMA JAMA Patient Page April 13, 2021 This JAMA Patient Page summarizes the US Preventive Services Task Force’s 2021 recommendation that current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for vitamin D deficiency in asymptomatic adults (I statement). Jill Jin, MD, MPH

- USPSTF Still Finds Insufficient Evidence to Support Screening for Vitamin D Deficiency JAMA Network Open Editorial April 13, 2021 Erin D. Michos, MD, MHS; Rita R. Kalyani, MD, MHS; Jodi B. Segal, MD, MPH

See More About

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Others Also Liked

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Vitamin D Deficiency in Adults : US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement . JAMA. 2021;325(14):1436–1442. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.3069

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Screening for Vitamin D Deficiency in Adults : US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement

- Editorial USPSTF 2021 Recommendations on Screening for Asymptomatic Vitamin D Deficiency in Adults Sherri-Ann M. Burnett-Bowie, MD, MPH; Anne R. Cappola, MD, ScM JAMA

- Editorial USPSTF Still Finds Insufficient Evidence to Support Screening for Vitamin D Deficiency Erin D. Michos, MD, MHS; Rita R. Kalyani, MD, MHS; Jodi B. Segal, MD, MPH JAMA Network Open

- US Preventive Services Task Force USPSTF Review: Screening for Vitamin D Deficiency in Adults Leila C. Kahwati, MD, MPH; Erin LeBlanc, MD, MPH; Rachel Palmieri Weber, PhD; Kayla Giger, BS; Rachel Clark, BA; Kara Suvada, BS; Amy Guisinger, BS; Meera Viswanathan, PhD JAMA

- JAMA Patient Page Patient Information: Screening for Vitamin D Deficiency in Adults Jill Jin, MD, MPH JAMA

Importance Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin that performs an important role in calcium homeostasis and bone metabolism and also affects many other cellular regulatory functions outside the skeletal system. Vitamin D requirements may vary by individual; thus, no one serum vitamin D level cutpoint defines deficiency, and no consensus exists regarding the precise serum levels of vitamin D that represent optimal health or sufficiency.

Objective To update its 2014 recommendation, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) commissioned a systematic review on screening for vitamin D deficiency, including the benefits and harms of screening and early treatment.

Population Community-dwelling, nonpregnant adults who have no signs or symptoms of vitamin D deficiency or conditions for which vitamin D treatment is recommended.

Evidence Assessment The USPSTF concludes that the overall evidence on the benefits of screening for vitamin D deficiency is lacking. Therefore, the balance of benefits and harms of screening for vitamin D deficiency in asymptomatic adults cannot be determined.

Recommendation The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for vitamin D deficiency in asymptomatic adults. (I statement)

See the Summary of Recommendation figure.

Quiz Ref ID Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin that performs an important role in calcium homeostasis and bone metabolism and also affects many other cellular regulatory functions outside the skeletal system. 1 - 3 Vitamin D requirements may vary by individual; thus, no one serum vitamin D level cutpoint defines deficiency, and no consensus exists regarding the precise serum levels of vitamin D that represent optimal health or sufficiency. According to the National Academy of Medicine, an estimated 97.5% of the population will have their vitamin D needs met at a serum level of 20 ng/mL (49.9 nmol/L) and risk for deficiency, relative to bone health, begins to occur at levels less than 12 to 20 ng/mL (29.9-49.9 nmol/L). 1 , 4 A report based on data from the 2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that 5% of the population 1 year or older had very low 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) levels (<12 ng/mL) and 18% had levels between 12 and 19 ng/mL. 5

Quiz Ref ID The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) concludes that the overall evidence on the benefits of screening for vitamin D deficiency is lacking. Therefore, the balance of benefits and harms of screening for vitamin D deficiency in asymptomatic adults cannot be determined ( Table ).

See the Figure , Table , and eFigure in the Supplement for more information on the USPSTF recommendation rationale and assessment. For more details on the methods the USPSTF uses to determine the net benefit, see the USPSTF Procedure Manual. 6

Quiz Ref ID This recommendation applies to community-dwelling, nonpregnant adults who have no signs or symptoms of vitamin D deficiency, such as bone pain or muscle weakness, or conditions for which vitamin D treatment is recommended. This recommendation focuses on screening (ie, testing for vitamin D deficiency in asymptomatic adults and treating those found to have a deficiency), which differs from USPSTF recommendation statements on supplementation.

Quiz Ref ID Although there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against screening for vitamin D deficiency, several factors are associated with lower vitamin D levels. Low dietary vitamin D intake may be associated with lower 25(OH)D levels. 7 Little or no UV B exposure (eg, because of winter season, high latitude, or sun avoidance) and older age are also associated with an increased risk for low vitamin D levels. 8 - 12 Obesity is associated with lower 25(OH)D levels, 13 and people who are obese have a 1.3- to 2-fold increased risk of being vitamin D–deficient, depending on the threshold used to define deficiency. 8 , 9 , 13 , 14 The exact mechanism for this finding is not completely understood.

Depending on the serum threshold used to define deficiency, the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency is 2 to 10 times higher in non-Hispanic Black persons than in non-Hispanic White persons, likely related to differences in skin pigmentation. 7 - 9 , 14 However, these prevalence estimates are based on total 25(OH)D levels, and controversy remains about whether this is the best measure of vitamin D status among different racial and ethnic groups.

A significant proportion of the variability in 25(OH)D levels among individuals is not explained by the risk factors noted above, which seem to account for only 20% to 30% of the variation in 25(OH)D levels. 11 , 15

Vitamin D deficiency is usually treated with oral vitamin D. There are 2 commonly available forms of vitamin D—vitamin D 3 (cholecalciferol) and vitamin D 2 (ergocalciferol). Both are available as either a prescription medication or an over-the-counter dietary supplement.

The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency varies based on how deficiency is defined. According to data from the 2011 to 2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which used the liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) assay to measure 25(OH)D levels, 5% of the population 1 year or older had very low 25(OH)D levels (<12 ng/mL) and 18% had levels between 12 and 19 ng/mL. 5 (To convert 25[OH]D values to nmol/L, multiply by 2.496.)

In some observational studies, lower vitamin D levels have been associated with risk for fractures, falls, functional limitations, some types of cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, depression, and death. 16 , 17 However, observations of these associations are inconsistent. This inconsistency may be because of different studies using different cutoffs to define a low vitamin D level or because vitamin D requirements and the optimal cutoff that defines a low vitamin D level or vitamin D deficiency may vary by individual or by subpopulation. For example, non-Hispanic Black persons have lower reported rates of fractures 18 despite having increased prevalence of lower vitamin D levels than White persons. 7 - 9 , 14 Further, it is unknown whether these associations are linked to causality.

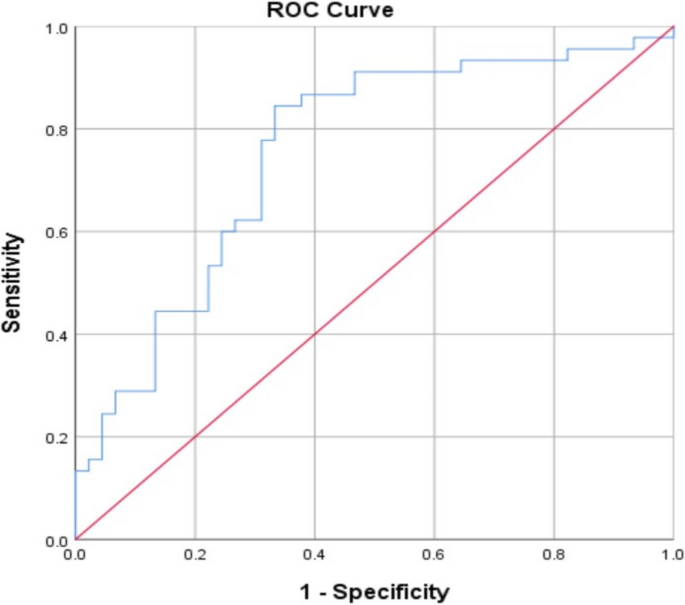

The goal of screening for vitamin D deficiency would be to identify and treat it before associated adverse clinical outcomes occur. Total 25(OH)D level is currently considered the best marker of vitamin D status. 4 , 19 A variety of assays can be used to measure 25(OH)D levels; however, levels can be difficult to measure accurately, and assays may underestimate or overestimate 25(OH)D levels. Additionally, the current evidence is inadequate to determine whether screening for and treatment of asymptomatic low 25(OH)D levels improve clinical outcomes in community-dwelling adults.

Screening may misclassify persons with a vitamin D deficiency because of the uncertainty about the cutoff for defining deficiency and the variability of available testing assays. Misclassification may result in overdiagnosis (leading to nondeficient persons receiving unnecessary treatment) or underdiagnosis (leading to deficient persons not receiving treatment).

Quiz Ref ID A rare but potential harm of treatment with vitamin D is toxicity, which is characterized by marked hypercalcemia as well as hyperphosphatemia and hypercalciuria. However, the 25(OH)D level associated with toxicity (typically >150 ng/mL) 20 is well above the level considered to be sufficient. In general, treatment with oral vitamin D does not seem to be associated with serious harms.

The prevalence of screening for vitamin D deficiency by primary care clinicians in the US has not been well studied. Data suggest that laboratory testing for vitamin D levels has increased greatly over the last several years or longer. One study reported a more than 80-fold increase in Medicare reimbursement volumes for vitamin D testing from 2000 to 2010. 21

The USPSTF has published recommendations on the use of vitamin D supplementation for the prevention of falls 22 and fractures 23 and vitamin supplementation for the prevention of cardiovascular disease or cancer. 24 These recommendations differ from the current recommendation statement in that they address vitamin D supplementation without first determining a patient's vitamin D status (ie, regardless of whether they have a deficiency).

This recommendation updates the 2014 USPSTF recommendation statement on screening for vitamin D deficiency in asymptomatic adults. In 2014, the USPSTF concluded that the evidence was insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for vitamin D deficiency. 25 For the current recommendation statement, the USPSTF again concludes that the evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for vitamin D deficiency in asymptomatic adults.

To update its 2014 recommendation statement, the USPSTF commissioned a systematic review 26 , 27 of the evidence on screening for vitamin D deficiency, including the benefits and harms of screening and early treatment. The review focused on asymptomatic, community-dwelling, nonpregnant adults 18 years or older who do not have clinical signs of vitamin D deficiency or conditions that could cause vitamin D deficiency, or for which vitamin D treatment is recommended, and who were seen in primary care settings.

Total 25(OH)D levels can be measured by both binding and chemical assays. Serum total 25(OH)D levels are difficult to measure accurately, and different immunoassays can lead to underestimation or overestimation of total 25(OH)D levels. 19 LC-MS/MS is considered the reference assay. However, LC-MS/MS is a complicated process and is subject to variation and error, including interference from other chemical compounds. 19

In 2010, the National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements, in collaboration with other organizations, initiated the Vitamin D Standardization Program. 28 , 29 The primary goal of the program has been to promote the standardized measurement of 25(OH)D levels. Most of the trials reviewed for this recommendation precede this standardization program. When previously banked samples have been reassayed using these standardized methods, both upward and downward revisions of 25(OH)D levels have been observed, depending on the original assay that was used. 19 , 30 , 31

The USPSTF found no studies that directly evaluated the benefits of screening for vitamin D deficiency. The USPSTF did find 26 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and 1 nested case-control study that reported on the effectiveness of treatment of vitamin D deficiency (variably defined as a level <20 ng/mL to <31.2 ng/mL) on a variety of health outcomes, including all-cause mortality, fractures, incidence of diabetes, cardiovascular events and cancer, falls, depression, physical function, and infection. 26 , 27

Eight RCTs and 1 nested case-control study reported on all-cause mortality in community-dwelling adults. Study duration ranged from 16 weeks to 7 years. In a pooled analysis of the 8 trials (n = 2006), there was no difference in all-cause mortality in persons randomized to vitamin D treatment compared with controls (relative risk [RR], 1.13 [95% CI, 0.39-3.28]). 26 , 27 In the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Calcium–Vitamin D nested case-control study, there was no association between treatment with vitamin D and calcium and all-cause mortality among participants with baseline vitamin D levels between 14 and 21 ng/mL and among participants with baseline levels less than 14 ng/mL. 32 , 33

Six RCTs reported on fracture outcomes in community-dwelling adults. Study duration ranged from 12 weeks to 7 years. A pooled analysis of the 6 trials (n = 2186) found no difference in the incidence of fractures among those randomized to vitamin D treatment compared with placebo (RR, 0.84 [95% CI, 0.58-1.21]). 26 The USPSTF found only 1 trial reporting on hip fracture in community-dwelling adults. In that study, only 1 hip fracture occurred, leading to a very imprecise effect estimate. 34 In the WHI Calcium–Vitamin D nested case-control study, there was no association between treatment with vitamin D and calcium and clinical fracture or hip fracture incidence. 32

Five RCTs reported on incident diabetes. Study duration ranged from 1 year to 7 years. A pooled analysis of the 5 trials (n = 3356) found no difference in the incidence of diabetes among participants randomized to vitamin D treatment compared with placebo (RR, 0.96 [95% CI, 0.80-1.15]). 26

For several outcomes, the USPSTF found inadequate evidence on the benefit of treatment of asymptomatic vitamin D deficiency. Limitations of the following evidence include few studies reporting certain outcomes and, for some outcomes, variable methods of ascertainment, variable reporting of outcomes, small study size, or short duration of follow-up.

Two trials, the Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial (VITAL) (n = 2001 in trial subgroup) 35 and the Vitamin D Assessment Study (ViDA) (n = 1270 in trial subgroup), 36 reported on cardiovascular events. Both trials observed no statistically significant differences in cardiovascular events between the treatment and placebo groups among the subgroup of participants with serum vitamin D levels less than 20 ng/mL at baseline. VITAL had 5.3 years of follow-up, while the ViDA trial had only 3.3 years of follow-up. The ViDA trial also used a heterogeneous definition of cardiovascular events, which included venous thromboembolism, pulmonary embolism, inflammatory cardiac conditions, arrhythmias, and conduction disorders.

Two trials, VITAL 35 and a post hoc analysis of the ViDA trial, 37 and the WHI nested case-control study 38 , 39 reported on the effect of vitamin D treatment on the incidence of cancer. Both trials reported no difference in cancer incidence between participants randomized to treatment and placebo among the subgroup of participants with serum 25(OH)D levels less than 20 ng/mL at baseline. The ViDA trial had only 3 years of follow-up, which may be a short period to detect an effect on cancer incidence. In the WHI Calcium–Vitamin D nested case-control study, the adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for incident breast or colorectal cancer over 7 years of follow-up did not demonstrate a statistically significant association between exposure to active treatment and incidence of cancer among participants with vitamin D deficiency at baseline. 38 , 39

Nine trials reported fall outcomes in community-dwelling adults. 26 , 27 Some trials reported only falls, others only the number of participants who experienced 1 or more falls (ie, “fallers”), and some trials reported both outcomes. A pooled analysis of 6 trials found no association between vitamin D treatment and number of fallers (RR, 0.90 [95% CI, 0.75-1.08]), while a pooled analysis of 5 trials found a significant association between vitamin D treatment and falls (incidence rate ratio, 0.76 [95% CI, 0.57-0.94]). 26 , 27 However, heterogeneity was high in both analyses, ascertainment methods for falls and fallers were variable across studies, and the variable reporting of falls, fallers, or both outcomes raises the possibility of selective outcome reporting. One trial reported on the incidence of 2 or more falls, a different definition of “fallers” than in the trials included in the pooled analysis above. It found no significant difference between participants randomized to vitamin D or placebo among the subgroup of participants with baseline vitamin D levels less than 12 ng/mL (adjusted OR, 1.03 [95% CI, 0.59-1.79]) or among those with levels between 12 and 20 ng/mL (adjusted OR, 1.13 [95% CI, 0.87-1.48]). 40

Three trials reported depression outcomes. One, VITAL-DEP (Depression Endpoint Prevention), was an ancillary study to the VITAL trial. Among the subgroup of participants with baseline serum vitamin D levels less than 20 ng/mL (n = 1328), there was no difference in the change in Personal Health Questionnaire Depression Scale scores between those randomized to vitamin D compared with placebo over a median follow-up of 5.3 years. 41 The other 2 trials were relatively small and of short duration. Both reported no significant difference in depression measures between vitamin D treatment and placebo. 42 , 43 Two trials reporting on physical functioning measures reported conflicting results. 44 , 45 An unplanned subgroup analysis of 1 trial conducted in persons with impaired fasting glucose found no difference in incidence of a first urinary tract infection in participants with vitamin D deficiency who were treated with vitamin D compared with placebo. 46

As noted, the studies comprising the body of evidence cited above did not uniformly define vitamin D deficiency. Different studies enrolled participants with vitamin D levels that ranged from less than 20 ng/mL to less than 31.2 ng/mL. For those outcomes with sufficient data (mortality, fractures, and falls), findings were similar between studies using a lower threshold and studies using a higher threshold. 26 , 27

The USPSTF found no studies that directly evaluated the harms of screening for vitamin D deficiency. The USPSTF found 36 studies that reported adverse events and harms from treatment with vitamin D (with or without calcium) compared with a control group. The absolute incidence of adverse events varied widely across studies; however, the incidence of total adverse events, such as gastrointestinal symptoms, fatigue, musculoskeletal symptoms, and headaches, and serious adverse events was generally similar between treatment and control groups. In the 10 trials that reported incidence of kidney stones, there was only 1 case. 26 , 27

A draft version of this recommendation statement was posted for public comment on the USPSTF website from September 22, 2020, to October 19, 2020. Some comments requested the USPSTF to evaluate the evidence on or make a recommendation regarding vitamin D supplementation. In response, the USPSTF wants to clarify that this recommendation focuses on screening for vitamin D deficiency. The USPSTF does have separate recommendations that address vitamin D supplementation (ie, providing vitamin D to all persons without testing, and regardless of vitamin D level) for a variety of conditions. 22 - 24 In response to comments, the USPSTF also wants to clarify that this recommendation applies to asymptomatic, community-dwelling adults. It does not apply to persons in institutional or hospital settings, who may have underlying or intercurrent conditions that warrant vitamin D testing or treatment. The USPSTF also wants to clarify that it did not review the emerging evidence on COVID-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, and vitamin D.

More studies are needed that address the following areas:

More research is needed to determine whether total serum 25(OH)D levels are the best measure of vitamin D deficiency and whether the best measure of vitamin D deficiency varies by subgroups defined by race, ethnicity, or sex.

More research is needed to determine the cutoff that defines vitamin D deficiency and whether that cutoff varies by specific clinical outcome or by subgroups defined by race, ethnicity, or sex.

When vitamin D deficiency is better defined, studies on the benefits and harms of screening for vitamin D deficiency will be helpful.

No organization recommends population-based screening for vitamin D deficiency, and the American Society for Clinical Pathology recommends against it. 47 The American Academy of Family Physicians supports the USPSTF 2014 recommendation, which states that there is insufficient evidence to recommend screening the general population for vitamin D deficiency. 48 The Endocrine Society 49 and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists 50 recommend screening for vitamin D deficiency in individuals at risk. The Endocrine Society does not recommend population screening for vitamin D deficiency in individuals not at risk. 49

Corresponding Author: Alex H. Krist, MD, MPH, Virginia Commonwealth University, 830 E Main St, One Capitol Square, Sixth Floor, Richmond, VA 23219 ( [email protected] ).

Accepted for Publication: February 22, 2021.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) members: Alex H. Krist, MD, MPH; Karina W. Davidson, PhD, MASc; Carol M. Mangione, MD, MSPH; Michael Cabana, MD, MA, MPH; Aaron B. Caughey, MD, PhD; Esa M. Davis, MD, MPH; Katrina E. Donahue, MD, MPH; Chyke A. Doubeni, MD, MPH; John W. Epling Jr, MD, MSEd; Martha Kubik, PhD, RN; Li Li, MD, PhD, MPH; Gbenga Ogedegbe, MD, MPH; Douglas K. Owens, MD, MS; Lori Pbert, PhD; Michael Silverstein, MD, MPH; James Stevermer, MD, MSPH; Chien-Wen Tseng, MD, MPH, MSEE; John B. Wong, MD.

Affiliations of The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) members: Fairfax Family Practice Residency, Fairfax, Virginia (Krist); Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond (Krist); Feinstein Institute for Medical Research at Northwell Health, New York, New York (Davidson); University of California, Los Angeles (Mangione); Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, New York (Cabana); Oregon Health & Science University, Portland (Caughey); University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (Davis); University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Donahue); Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota (Doubeni); Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke (Epling Jr); George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia (Kubik); University of Virginia, Charlottesville (Li); New York University, New York, New York (Ogedegbe); Stanford University, Stanford, California (Owens); University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester (Pbert); Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts (Silverstein); University of Missouri, Columbia (Stevermer); University of Hawaii, Honolulu (Tseng); Pacific Health Research and Education Institute, Honolulu, Hawaii (Tseng); Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts (Wong).

Author Contributions: Dr Krist had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The USPSTF members contributed equally to the recommendation statement.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Authors followed the policy regarding conflicts of interest described at https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/conflict-of-interest-disclosures . All members of the USPSTF receive travel reimbursement and an honorarium for participating in USPSTF meetings.

Funding/Support: The USPSTF is an independent, voluntary body. The US Congress mandates that the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) support the operations of the USPSTF.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: AHRQ staff assisted in the following: development and review of the research plan, commission of the systematic evidence review from an Evidence-based Practice Center, coordination of expert review and public comment of the draft evidence report and draft recommendation statement, and the writing and preparation of the final recommendation statement and its submission for publication. AHRQ staff had no role in the approval of the final recommendation statement or the decision to submit for publication.

Disclaimer: Recommendations made by the USPSTF are independent of the US government. They should not be construed as an official position of AHRQ or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Additional Contributions: We thank Howard Tracer, MD (AHRQ), who contributed to the writing of the manuscript, and Lisa Nicolella, MA (AHRQ), who assisted with coordination and editing.

Additional Information: The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) makes recommendations about the effectiveness of specific preventive care services for patients without obvious related signs or symptoms. It bases its recommendations on the evidence of both the benefits and harms of the service and an assessment of the balance. The USPSTF does not consider the costs of providing a service in this assessment. The USPSTF recognizes that clinical decisions involve more considerations than evidence alone. Clinicians should understand the evidence but individualize decision-making to the specific patient or situation. Similarly, the USPSTF notes that policy and coverage decisions involve considerations in addition to the evidence of clinical benefits and harms.

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Everything counts!

How do you read organization’s silence over rise of Nazism?

Got milk? Does it give you problems?

“This is the first direct evidence we have that daily supplementation may reduce AD incidence, and what looks like more pronounced effect after two years of supplementation for vitamin D,” said Karen Costenbader, senior author of the study.

Michele Blackwell/Unsplash

Vitamin D supplements lower risk of autoimmune disease, researchers say

Haley Bridger

BWH Communications

Study of older adults is ‘first direct evidence’ of protection against rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, other conditions

In a new study, investigators from Brigham and Women’s Hospital found the people who took vitamin D, or vitamin D and omega-3 fatty acids, had a significantly lower rate of autoimmune diseases — such as rheumatoid arthritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, autoimmune thyroid disease, and psoriasis — than people who took a placebo.

With their findings published Wednesday in BMJ , the team had tested this in the large-scale vitamin D and omega-3 trial (VITAL), a randomized study which followed participants for approximately five years. Investigators found the people who took vitamin D, or vitamin D and omega-3 fatty acids had a significantly lower rate of AD than people who took a placebo.

“It is exciting to have these new and positive results for nontoxic vitamins and supplements preventing potentially highly morbid diseases,” said senior author Karen Costenbader of the Brigham’s Division of Rheumatology, Inflammation and Immunity. “This is the first direct evidence we have that daily supplementation may reduce AD incidence, and what looks like more pronounced effect after two years of supplementation for vitamin D. We look forward to honing and expanding our findings and encourage professional societies to consider these results and emerging data when developing future guidelines for the prevention of autoimmune diseases in midlife and older adults.”

“Now, when my patients, colleagues, or friends ask me which vitamins or supplements I’d recommend they take to reduce risk of autoimmune disease, I have new evidence-based recommendations for women age 55 years and older and men 50 years and older,” said Costenbader. “I suggest vitamin D 2000 IU a day and marine omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil), 1000 mg a day — the doses used in VITAL.”

VITAL is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled research study of 25,871 men (age 50 and older) and women (age 55 and older) across the U.S., conducted to investigate whether taking daily dietary supplements of vitamin D3 (2000 IU) or omega-3 fatty acids (Omacor fish oil, 1 gram) could reduce the risk for developing cancer, heart disease, and stroke in people who do not have a prior history of these illnesses. Participants were randomized to receive either vitamin D with an omega-3 fatty acid supplement; vitamin D with a placebo; omega-3 fatty acid with a placebo; or placebo only. Prior to the launch of VITAL, investigators determined that they would also look at rates of AD among participants, as part of an ancillary study.

“Given the benefits of vitamin D and omega-3s for reducing inflammation, we were particularly interested in whether they could protect against autoimmune diseases,” said JoAnn Manson, co-author and director of the parent VITAL trial at the Brigham.

Participants answered questionnaires about new diagnoses of diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, autoimmune thyroid disease, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease, with space to write in all other new onset ADs. Trained physicians reviewed patients’ medical records to confirm reported diagnoses.

“Autoimmune diseases are common in older adults and negatively affect health and life expectancy. Until now, we have had no proven way of preventing them, and now, for the first time, we do,” said first author, Jill Hahn, a postdoctoral fellow at the Brigham. “It would be exciting if we could go on to verify the same preventive effects in younger individuals.”

Among patients who were randomized to receive vitamin D, 123 participants in the treatment group and 155 in the placebo group were diagnosed with confirmed AD (22 percent reduction). Among those in the fatty acid arm, confirmed AD occurred in 130 participants in the treatment group and 148 in the placebo group. Supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids alone did not significantly lower incidence of AD, but the study did find evidence of an increased effect after longer duration of supplementation.

The VITAL study included a large and diverse sample of participants, but all participants were older and results may not be generalizable to younger individuals who experience AD earlier in life. The trial also only tested one dose and one formulation of each supplement. The researchers note that longer follow-up may be more informative to assess whether the effects are long-lasting.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health grants R01 AR059086, U01 CA138962, R01 CA138962.

Share this article

You might like.

New study finds step-count and time are equally valid in reducing health risks

Medical historians look to cultural context, work of peer publications in wrestling with case of New England Journal of Medicine

Biomolecular archaeologist looks at why most of world’s population has trouble digesting beverage that helped shape civilization

Glimpse of next-generation internet

Physicists demo first metro-area quantum computer network in Boston

Good genes are nice, but joy is better

Harvard study, almost 80 years old, has proved that embracing community helps us live longer, and be happier

- Alzheimer's disease & dementia

- Arthritis & Rheumatism

- Attention deficit disorders

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Biomedical technology

- Diseases, Conditions, Syndromes

- Endocrinology & Metabolism

- Gastroenterology

- Gerontology & Geriatrics

- Health informatics

- Inflammatory disorders

- Medical economics

- Medical research

- Medications

- Neuroscience

- Obstetrics & gynaecology

- Oncology & Cancer

- Ophthalmology

- Overweight & Obesity

- Parkinson's & Movement disorders

- Psychology & Psychiatry

- Radiology & Imaging

- Sleep disorders

- Sports medicine & Kinesiology

- Vaccination

- Breast cancer

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Colon cancer

- Coronary artery disease

- Heart attack

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- Kidney disease

- Lung cancer

- Multiple sclerosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Ovarian cancer

- Post traumatic stress disorder

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Schizophrenia

- Skin cancer

- Type 2 diabetes

- Full List »

share this!

May 20, 2024

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

reputable news agency

Vitamin D deficiency tied to worse outcomes with early kidney disease

by Lori Solomon

Vitamin D deficiency is associated with increased risks for cardiovascular mortality and chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression in patients with early-stage disease, according to a study published online May 11 in the Journal of Endocrinological Investigation .

Yanhong Lin, from Southern Medical University in Guangzhou, China, and colleagues examined the effects of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) deficiency on cardiovascular mortality and kidney outcomes in patients with early-stage CKD. The analysis included 9,229 adult patients with CKD (stages 1 to 3) from 19 medical centers across China (January 2000 to May 2021).

The researchers found that compared with patients having 25(OH)D ≥20 ng/mL, a there was a significantly higher risk for cardiovascular mortality (hazard ratio, 1.90) and CKD progression (hazard ratio, 2.20) as well as a steeper annual decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate (estimate, −7.87 percent per year) in those with serum 25(OH)D <10 ng/mL.

"In conclusion, 25(OH)D deficiency was common in patients with early-stage CKD," the authors write. "Vitamin D status should be closely monitored in patients with early CKD. Well-designed randomized clinical trials are needed to determine whether timely vitamin D supplementation can prevent cardiovascular events and loss of kidney function in patients with early-stage CKD and 25(OH)D deficiency."

Copyright © 2024 HealthDay . All rights reserved.

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Study: Newborns whose mother spoke in a mix of languages during pregnancy are more sensitive to a range of sound pitches

3 hours ago

Study finds ultraviolet radiation may affect subcutaneous fat regulation, could lead to new obesity treatments

Regular fish oil supplement use might increase first-time heart disease and stroke risk

9 hours ago

Pedestrians may be twice as likely to be hit by electric/hybrid cars as petrol/diesel ones

Study finds jaboticaba peel reduces inflammation and controls blood sugar in people with metabolic syndrome

10 hours ago

Study reveals how extremely rare immune cells predict how well treatments work for recurrent hives

12 hours ago

Researchers find connection between PFAS exposure in men and the health of their offspring

Researchers develop new tool for better classification of inherited disease-causing variants

Specialized weight navigation program shows higher use of evidence-based treatments, more weight lost than usual care

Exercise bouts could improve efficacy of cancer drug

Related stories.

High systemic immune-inflammation index tied to higher mortality with peritoneal dialysis

Sep 22, 2023

Incident CVD, mortality risk heightened for at least one year after COVID-19

Feb 21, 2023

Peritonitis tied to cardiovascular mortality in peritoneal dialysis population

Dec 27, 2022

Tirzepatide improves kidney outcomes in T2DM with increased CV risk

Jun 6, 2022

Remote patient monitoring tied to better dialysis technique survival

Feb 23, 2024

Benefit of ICD attenuated in CKD patients receiving cardiac resynchronization

Sep 25, 2023

Recommended for you

Drug-like inhibitor shows promise in preventing flu

Hope for a cure for visceral leishmaniasis, an often fatal infectious disease

16 hours ago

Matcha mouthwash shown to inhibit bacteria that cause periodontitis

18 hours ago

Let us know if there is a problem with our content

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Medical Xpress in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 20 August 2019

Interventions and public health nutrition

The economic case for prevention of population vitamin D deficiency: a modelling study using data from England and Wales

- M. Aguiar 1 , 2 ,

- L. Andronis 1 , 3 ,

- M. Pallan 1 ,

- W. Högler 4 , 5 &

- E. Frew ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5462-1158 1

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition volume 74 , pages 825–833 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

1829 Accesses

28 Citations

819 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Endocrinology

Vitamin D deficiency (VDD) affects the health and wellbeing of millions worldwide. In high latitude countries such as the United Kingdom (UK), severe complications disproportionally affect ethnic minority groups.

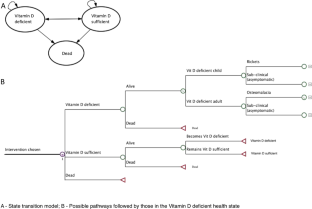

To develop a decision-analytic model to estimate the cost effectiveness of population strategies to prevent VDD.

An individual-level simulation model was used to compare: (I) wheat flour fortification; (II) supplementation of at-risk groups; and (III) combined flour fortification and supplementation; with (IV) a ‘no additional intervention’ scenario, reflecting the current Vitamin D policy in the UK. We simulated the whole population over 90 years. Data from national nutrition surveys were used to estimate the risk of deficiency under the alternative scenarios. Costs incurred by the health care sector, the government, local authorities, and the general public were considered. Results were expressed as total cost and effect of each strategy, and as the cost per ‘prevented case of VDD’ and the ‘cost per Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY)’.

Wheat flour fortification was cost saving as its costs were more than offset by the cost savings from preventing VDD. The combination of supplementation and fortification was cost effective (£9.5 per QALY gained). The model estimated that wheat flour fortification alone would result in 25% fewer cases of VDD, while the combined strategy would reduce the number of cases by a further 8%.

There is a strong economic case for fortifying wheat flour with Vitamin D, alone or in combination with targeted vitamin D3 supplementation.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

251,40 € per year

only 20,95 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Global Perspective of the Vitamin D Status of African-Caribbean Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Official recommendations for vitamin D through the life stages in developed countries

Vitamin d deficiency 2.0: an update on the current status worldwide.

Holick MF. The vitamin D epidemic and its health consequences. J Nutr. 2005;135:2739s–48s. 2005/10/28

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bates B, Lennox A, Prentice A, Bates C, Page P, Nicholson S, et al. National diet and nutrition survey results from years 5 and 6 (combined) of the rolling programme (2012/2013–2013/2014). Public Health Engand and the Food Standards Agency; 2016.

Munns CF, Shaw N, Kiely M, Specker BL, Thacher TD, Ozono K, et al. Global consensus recommendations on prevention and management of nutritional rickets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:394–415. 2016/01/09

Uday S, Fratzl-Zelman N, Roschger P, Klaushofer K, Chikermane A, Saraff V, et al. Cardiac, bone and growth plate manifestations in hypocalcemic infants: revealing the hidden body of the vitamin D deficiency iceberg. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18:183.

Article Google Scholar

Maiya S, Sullivan I, Allgrove J, Yates R, Malone M, Brain C, et al. Hypocalcaemia and vitamin D deficiency: an important, but preventable, cause of life-threatening infant heart failure. Heart. 2008;94:581–4.

Patel JV, Chackathayil J, Hughes EA, Webster C, Lip GY, Gill PS. Vitamin D deficiency amongst minority ethnic groups in the UK: a cross sectional study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:2172–6. 2012/11/13

Uday S, Högler W. Prevention of rickets and osteomalacia in the UK: political action overdue. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103:901–906.

Brown LL, Cohen B, Tabor D, Zappalà G, Maruvada P, Coates PM. The vitamin D paradox in Black Americans: a systems-based approach to investigating clinical practice, research, and public health—expert panel meeting report. BMC Proc. 2018;12:6 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12919-018-0102-4.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Vatanparast H, Nisbet C, Gushulak B. Vitamin D insufficiency and bone mineral status in a population of newcomer children in Canada. Nutrients. 2013;5:1561–72. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23673607 .

Bärebring L, Schoenmakers I, Glantz A, Hulthén L, Jagner Å, Ellis J, et al. Vitamin D status during pregnancy in a multi-ethnic population-representative Swedish cohort. Nutrients. 2016;8:655.

Ramnemark A, Norberg M, Pettersson-Kymmer U, Eliasson M. Adequate vitamin D levels in a Swedish population living above latitude 63 N: the 2009 Northern Sweden MONICA study. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015;74:27963.

Andersson Å, Björk A, Kristiansson P, Johansson G. Vitamin D intake and status in immigrant and native Swedish women: a study at a primary health care centre located at 60 N in Sweden. Food Nutr Res. 2013;57:20089.

Glerup H, Rytter L, Mortensen L, Nathan E. Vitamin D deficiency among immigrant children in Denmark. Eur J Pediatr. 2004;163:272–3.

O’Callaghan KM, Kiely ME. Ethnic disparities in the dietary requirement for vitamin D during pregnancy: considerations for nutrition policy and research. Proc Nutr Soc. 2018;77:164–73.

Spiro A, Buttriss JL. Vitamin D: an overview of vitamin D status and intake in Europe. Nutr Bull. 2014;39:322–50. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4288313/ .

(SACN) SAC on N. Vitamin D and Health. Public Health England; 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/scientific-advisory-committee-on-nutrition .

Uday S, Kongjonaj A, Aguiar M, Tulchinsky T, Högler W. Variations in infant and childhood vitamin D supplementation programmes across Europe and factors influencing adherence. Endocr Connect. 2017;6:667–75. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28924002 .

Bates B, Lennox A, Prentice A, Bates C, Page P, Nicholson S, et al. National diet and nutrition survey results from years 1, 2, 3 and 4 (combined) of the rolling programme (2008/2009 –2011/2012). Public Health Engand and Food Standards Agency; 2014.

Basatemur E, Sutcliffe A. Incidence of hypocalcemic seizures due to vitamin D deficiency in children in the United Kingdom and Ireland. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;100:E91–5.

Julies P, Lynn RM, Pall K, Leoni M, Calder A, Mughal Z, et al. I16 Nutritional rickets presenting to secondary care in children (16 years)—a UK surveillance study. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(Suppl 1):A202 LP–A203. http://adc.bmj.com/content/103/Suppl_1/A202.3.abstract .

Cashman KD, Dowling KG, Skrabakova Z, Gonzalez-Gross M, Valtuena J, De Henauw S, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in Europe: pandemic? Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103:1033–44. 2016/02/13

Darling AL, Hart KH, Macdonald HM, Horton K, Kang’Ombe AR, Berry JL, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in UK South Asian Women of childbearing age: a comparative longitudinal investigation with UK Caucasian women. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:477–88.

Martin CA, Gowda U, Renzaho AMN. The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among dark-skinned populations according to their stage of migration and region of birth: a meta-analysis. Nutrition. 2016;32:21–32.

van der Meer IM, Middelkoop BJC, Boeke AJP, Lips P. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among Turkish, Moroccan, Indian and sub-Sahara African populations in Europe and their countries of origin: an overview. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:1009–21. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3046351/ .

Ginde AA, Liu MC, Camargo CA. Demographic differences and trends of vitamin D insufficiency in the US population, 1988–2004. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:626–32. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3447083/ .

Aguiar M, Andronis L, Pallan M, Högler W, Frew E. Preventing vitamin D deficiency (VDD): a systematic review of economic evaluations. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27:292–301. 2017/02/17

Barton P, Bryan S, Robinson S. Modelling in the economic evaluation of health care: selecting the appropriate approach. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2004;9:110–8.

Davis S, Stevenson M, Tappenden P, Wailoo AJ. NICE DSU Technical Support Document 15: Cost-effectiveness modelling using patient-level simulation. School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR), The University of Sheffield. 2014.

(NICE) NI for H and CE. Developing NICE guidelines: the manual [Internet]. 3rd ed. Process and methods [PMG20]. 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg20/chapter/incorporating-economic-evaluation .

Siebert U, Alagoz O, Bayoumi AM, Jahn B, Owens DK, Cohen DJ, et al. State-transition modeling: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM modeling good research practices task force-3. Value Health. 2012;15:812–20.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) statement. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2013;11:6.

Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1911–30.

Statistics O for N. Census. UK: Data Services Census Support.

Allen RE, Dangour AD, Tedstone AE, Chalabi Z. Does fortification of staple foods improve vitamin D intakes and status of groups at risk of deficiency? A United Kingdom modeling study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102:338–44.

Research NS, Laboratory MRCEW, London UC, School M. National Diet and Nutrition Survey Years 1–6, 2008/09-2013/14 [Internet]. UK Data Services; 2017. https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-6533-7 .

Allen RE. Would fortification of more foods with vitamin D improve vitamin D intakes and status of groups at risk of deficiency in the UK? London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine; 2013.

Limited T FreeD: Vitamin D supplementation in Lewisham; 2014. http://www.therapyaudit.com/media/2015/05/lewisham-casestudy.pdf .

Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, Sherrington C, Gates S, Clemson LM, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub3 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Aguiar M. Decision analytic modelling of the prevention of vitamin D deficiency in England and Wales. Birmingham, UK: University of Birmingham; 2018. http://etheses.bham.ac.uk/8120/ .

Food Standards Agency (FSA). Improving folate intakes of women of reproductive age and preventing neural tube defects: practical issues [Internet]. 2007. http://tna.europarchive.org/20120419000433/http://www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/fsa070604.pdf .

NABIM. Statistics [Internet]; 2014. http://www.nabim.org.uk/statistics .

Roy S, Sherman A, Monari-Sparks MJ, Schweiker O, Hunter K. Correction of low vitamin d improves fatigue: effect of correction of low vitamin D in fatigue study (EViDiF Study). North Am J Med Sci. 2014;6:396–402. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4158648/ .

Santos AS, Guerra-Junior AA, Godman B, Morton A, Ruas CM. Cost-effectiveness thresholds: methods for setting and examples from around the world. Exp Rev Pharm Outcomes Res. 2018;18:277–88.

Google Scholar

Jentink J, van de Vrie-Hoekstra NW, de Jong-van den Berg LT, Postma MJ. Economic evaluation of folic acid food fortification in The Netherlands. Eur J Public Heal. 2008;18:270–4.

Bentley TGK, Weinstein MC, Willett WC, Kuntz KM. A cost-effectiveness analysis of folic acid fortification policy in the United States. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:455–67.

Grosse SD, Berry RJ, Tilford JM, Kucik JE, Waitzman NJ. Retrospective assessment of cost savings from prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:S74–80.

Basatemur E, Hunter R, Horsfall L, Sutcliffe A, Rait G. Costs of vitamin D testing and prescribing among children in primary care. Eur J Pediatr. 2017;176:1405–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28803270 .

Poole CD, Smith J, Davies JS. Cost-effectiveness and budget impact of Empirical vitamin D therapy on unintentional falls in older adults in the UK. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007910.

Del Valle HB, Yaktine AL, Taylor CL, Ross AC. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington (DC), US: National Academies Press; 2011.

Zhang R, Li B, Gao X, Tian R, Pan Y, Jiang Y, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and the risk of cardiovascular disease: dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105:810–9. https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/105/4/810-819/4569717 .

Martineau AR, Jolliffe DA, Hooper RL, Greenberg L, Aloia JF, Bergman P, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i6583 . Accessed 18 Apr 2019.

(IOM) Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington (DC), US: National Academies Press; 2011.

Lindsay A, Benoist B, Dary O, Hurrell R, WHO/FAO. Guidelines on food fortification with micronutrients. Geneva: World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2006.

WHO/FAO. Evaluating the public health significance of micronutrient malnutrition. In: Guidelines on food fortification with micronutrients. Geneva: World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2006. p. 39–92.

Urrutia-Pereira M, Solé D. Vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy and its impact on the fetus, the newborn and in childhood. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2015;33:104–13.

Holick MF. The influence of vitamin D on bone health across the life cycle. J Nutr. 2005;135:2726S–2727S. https://academic.oup.com/jn/article/135/11/2726S/4669897 .

Darnton-Hill I, Webb P, Harvey PWJ, Hunt JM, Dalmiya N, Chopra M, et al. Micronutrient deficiencies and gender: social and economic costs. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:1198S–1205S. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/81.5.1198 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Bivins R. “The English Disease” or “Asian Rickets”? Medical responses to postcolonial immigration. Bull Hist Med. 2007;81:533.

Horton S. The economics of food fortification. J Nutr. 2006;136:1068–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/136.4.1068 .

Filby A, Wood H, Jenks M, Taylor M, Burley V, Barbier M, et al. Examining the cost-effectiveness of moving the healthy start vitamin programme from a targeted to a universal offering: cost-effectiveness systematic review [Internet]. NICE, editor. Vol. July; 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/NICE-guidance/NICE-guidelines/healthy-start-cost-effectiveness-review.pdf .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Dr. Sue Horton, School of Public Health and Health Systems, University of Waterloo, for initial advice on the economics of food fortification. Dr. Helena Pachón, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, for the insights on the practicalities of wheat flour fortification. The team at the Center for Health Economics Research and Evaluation, University Technology Sydney, particularly Dr. Phillip Haywood, as well as Dr. Kim Dalziel, Center for Health Policy, University of Melbourne, for the methodological advice. Smita Hanciles and Gwenda Scott from Lewisham Local Authority, UK, as well as Eleanor McGee from Birmingham Local Authority, UK, for the insights on supplementation alternatives and data access.

This research was funded by the College of Medical and Dental Sciences of the University of Birmingham, through an internal PhD studentship grant.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Applied Health Research, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, B15 2TT, UK

M. Aguiar, L. Andronis, M. Pallan & E. Frew

Collaboration for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, V6T 1Z3, Canada

Population, Evidence and Technologies, Division of Health Sciences, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK

L. Andronis

Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Johannes Kepler University, Linz, A-4040, Austria

Institute of Metabolism and Systems Research, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, B15 2TT, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions