Why education is the key to development

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Børge Brende

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Infrastructure is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, infrastructure.

Education is a human right. And, like other human rights, it cannot be taken for granted. Across the world, 59 million children and 65 million adolescents are out of school . More than 120 million children do not complete primary education.

Behind these figures there are children and youth being denied not only a right, but opportunities: a fair chance to get a decent job, to escape poverty, to support their families, and to develop their communities. This year, decision-makers will set the priorities for global development for the next 15 years. They should make sure to place education high on the list.

The deadline for the Millennium Development Goals is fast approaching. We have a responsibility to make sure we fulfill the promise we made at the beginning of the millennium: to ensure that boys and girls everywhere complete a full course of primary schooling.

The challenge is daunting. Many of those who remain out of school are the hardest to reach, as they live in countries that are held back by conflict, disaster, and epidemics. And the last push is unlikely to be accompanied by the double-digit economic growth in some developing economies that makes it easier to expand opportunities.

Nevertheless, we can succeed. Over the last 15 years, governments and their partners have shown that political will and concerted efforts can deliver tremendous results – including halving the number of children and adolescents who are out of school. Moreover, most countries are closing in on gender parity at the primary level. Now is the time to redouble our efforts to finish what we started.

But we must not stop with primary education. In today’s knowledge-driven economies, access to quality education and the chances for development are two sides of the same coin. That is why we must also set targets for secondary education, while improving quality and learning outcomes at all levels. That is what the Sustainable Development Goal on education, which world leaders will adopt this year, aims to do.

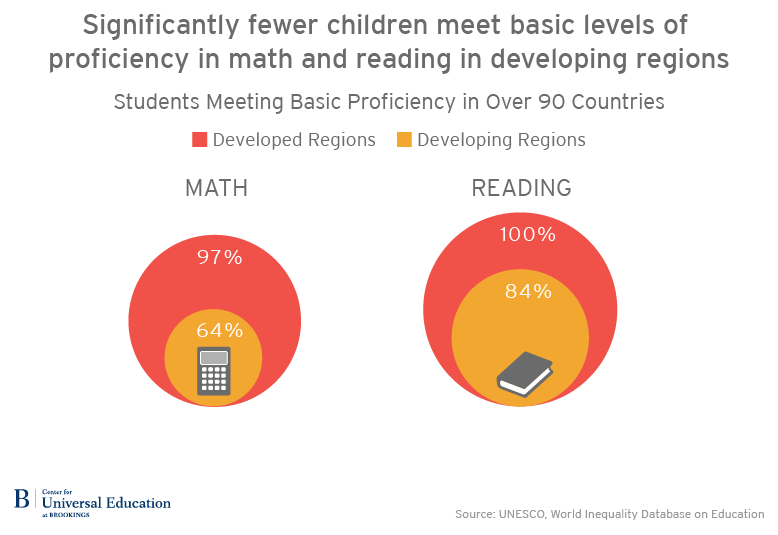

Addressing the fact that an estimated 250 million children worldwide are not learning the basic skills they need to enter the labor market is more than a moral obligation. It amounts to an investment in sustainable growth and prosperity. For both countries and individuals, there is a direct and indisputable link between access to quality education and economic and social development.

Likewise, ensuring that girls are not kept at home when they reach puberty, but are allowed to complete education on the same footing as their male counterparts, is not just altruism; it is sound economics. Communities and countries that succeed in achieving gender parity in education will reap substantial benefits relating to health, equality, and job creation.

All countries, regardless of their national wealth, stand to gain from more and better education. According to a recent OECD report , providing every child with access to education and the skills needed to participate fully in society would boost GDP by an average 28% per year in lower-income countries and 16% per year in high-income countries for the next 80 years.

Today’s students need “twenty-first-century skills,” like critical thinking, problem solving, creativity, and digital literacy. Learners of all ages need to become familiar with new technologies and cope with rapidly changing workplaces.

According to the International Labour Organization, an additional 280 million jobs will be needed by 2019. It is vital for policymakers to ensure that the right frameworks and incentives are established so that those jobs can be created and filled. Robust education systems – underpinned by qualified, professionally trained, motivated, and well-supported teachers – will be the cornerstone of this effort.

Governments should work with parent and teacher associations, as well as the private sector and civil-society organizations, to find the best and most constructive ways to improve the quality of education. Innovation has to be harnessed, and new partnerships must be forged.

Of course, this will cost money. According to UNESCO, in order to meet our basic education targets by 2030, we must close an external annual financing gap of about $22 billion. But we have the resources necessary to deliver. What is lacking is the political will to make the needed investments.

This is the challenge that inspired Norway to invite world leaders to Oslo for a Summit on Education for Development , where we can develop strategies for mobilizing political support for increasing financing for education. For the first time in history, we are in the unique position to provide education opportunities for all, if only we pull together. We cannot miss this critical opportunity.

To be sure, the responsibility for providing citizens with a quality education rests, first and foremost, with national governments. Aid cannot replace domestic-resource mobilization. But donor countries also have an important role to play, especially in supporting least-developed countries. We must reverse the recent downward trend in development assistance for education, and leverage our assistance to attract investments from various other sources. For our part, we are in the process of doubling Norway’s financial contribution to education for development in the period 2013-2017.

Together, we need to intensify efforts to bring the poorest and hardest to reach children into the education system. Education is a right for everyone. It is a right for girls, just as it is for boys. It is a right for disabled children, just as it is for everyone else. It is a right for the 37 million out-of-school children and youth in countries affected by crises and conflicts. Education is a right regardless of where you are born and where you grow up. It is time to ensure that the right is upheld.

This article is published in collaboration with Project Syndicate . Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter .

Author: Erna Solberg is Prime Minister of Norway. Børge Brende is Norway’s Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Image: Students attend a class at the Oxford International College in Changzhou. REUTERS/Aly Song.

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Economic Growth .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Migration is a global strategic asset. We must not undermine it

Marie McAuliffe

May 29, 2024

We asked chief economists about the state of the global economy. Here's what they said

Chief economists explore geoeconomic complexities and new drivers of growth: ‘Several opportunities exist’

Spencer Feingold

'Cautious optimism': Here's what chief economists think about the state of the global economy

Aengus Collins and Kateryna Karunska

How countries are redefining their bioeconomy for the future

Faisal Khan, Megan Palmer and Matthew Chang

May 28, 2024

What is needed for inclusive and sustainable global economic growth? Four leaders share their thoughts

Liam Coleman

May 24, 2024

Introduction

This paper addresses the topic of education and its importance in the development of a country. The topic will be explored and the argument considered in the following manner. First, there will be a definition of the words education and development . Second, will briefly consider a country where the education system has yielded positive results; the country that will be considered is Germany. Third, the paper will examine what happens when a country does not invest in the education of its citizens; the country considered will be Afghanistan. The thesis presented in this paper is the following: It is not possible for a country to be classified as a developed nation unless the educational system is an important part of the country’s domestic policy.

This topic was researched by reading peer-reviewed journals and grey literature about education , sociology , and, political science . The search terms used were the following search terms: ‘education development’ ; ‘education success’ ; ‘Germany education’ ; ‘Ireland education’ ; ‘Canada education’ ; ‘social impact education’ ; and, ‘economic impact education’ .

Definitions

While lengthy, the following definitions are worth considering in answering the thesis of this paper. There are various definitions of the word education , but pertinent to this paper is that used when looking at the focus of education. Cohen (2006) note that simply focusing on linguistics plus mathematical literacy is not enough, but “…that research-based social, emotional, ethical, and academic educational guidelines can predictably pro- mote the skills, knowledge, and dispositions that provide the foundation for the capacity to love, work, and be an active community member” (Cohen 202). In other words, education is not a mechanical, rote learning academic process, but is a system that is holistic and inclusive of other disciplines, thereby producing a student, at the end of the process, who is well placed to take his/her position as a responsible member of society.

When we consider the meaning of the word development, the words of Alkire (2010) perhaps best illustrates the relationship between education and development: “People are the real wealth of a nation. The basic objective of development is to create an enabling environment for people to live long, healthy and creative lives” (Alkire 2). In other words, the ability to enable an environment that lets individuals live their lives that are beneficial. When these lived lives become mutually beneficial, a nation is born. Carayannis, Pirzadeh and Popescu (2012) in looking at how best to define the nation-state, references Guehenno who states that “…[a nation] … bind[s] together the citizens of a nation … [and] is the product of a unique combination of historical factors, and can never be reduced to a single dimension, whether social, religious, or racial …[what] bring people together …[is] the memory of what they have been” (Carayannis, Pirzadeh and Popescu 8). Essentially, the latter point binds the argument that communities are driven by relationships that are bound by shared history and experiences. Communities need education to be the binding force that supports and creates a nation of people driven by common aspirations and goals. Without an education, it is not possible for a nation to hold itself together successfully.

Successful Education Practices

One particular nation comes to mind as an example of how education is used to build the success that allows a nation to develop economically. Germany has an education system that is bound tightly to the economic needs of the country’s success. From childhood, students are accessed and steered into courses and programs for which they have the skills, and these skills are directed into the industrial and economic need of the country. The result is that Germany is one of the most envied educational systems and one of the most envied economies. In reference to development, the German government notes that the country’s “development cooperation takes its lead from the concept of lifelong learning. Education does not stop after the first graduation certificate … People of every age must be given the opportunity to learn and develop. Education never ends” (BMZ 4). This concept of education as an element of social, cultural and, ultimately, nation building, is not uniquely Germany, but Germany has created a system that is responsive to its economic needs. Kotthoff (2011) describes the challenges in the German education system as tensions between selectivity vs. comprehensiveness; equity vs. excellence; and, academic subject knowledge vs. the didactic teaching skills of the educational professionals (Kotthoff 30; 38; 46; 55). In other words, there are constant priorities that need to be balanced in order to maintain an educational system that is responsive to the needs of the country. German evidence of success is found in the manner in which the vocational arm of the educational system, ensures work for students. Upon completing vocational schools and then completing training contracts, there is usually a job. German industries “pro-actively select the work on offer .. ensuring the system’s popularity for decades and [it] underpinned the rise and rise of the German manufacturing sector” (Hirst).

When Education is Not a Priority

A country where education is not a priority is Afghanistan. In Afghanistan, the political unrest of 30-40 years ago produced a social and political system that resulted in almost 30 years of war. During this time, education was not a priority, particularly for women. Women were either not educated or given minimal education. The result was the primary caregiver in the household raising children, but being unable to even help these children learn the basic elements of literacy. While not the sole cause, this practice of limited education enabled a political and religious fundamentalism that threw the country back to almost medieval standards. Since the American led Allied intervention of Afghanistan, in spite of many ongoing difficulties, schools are being built, some girls are able to acquire an education, and the country is slowly emerging for the medieval warfare that has plagued it for many decades (Human Rights Watch).

To conclude, the above arguments support the thesis of this paper. The thesis is that it is not possible for a country to be classified as a developed nation unless the educational system is an important part of the country’s domestic policy. The examples of the impact of education on two countries with histories of devastating wars, Germany and Afghanistan, support this argument. Where a nation has proactively engaged its educational policy in support of the country’s economic development, there is success. Germany, in spite of the terrible history of wars in the twentieth century, reinvented itself through education. Whether or not Afghanistan can do the same thing remains to be seen. The evidence in Afghanistan suggests that the changes in that country have been significant since the American led intervention. Non-governmental organizations and national governments around the world have poured money and resources into the country, since that time, in an effort to stem the political and social regression of that nation. There have been changes, some of them small, but provision of education for the girls of Afghanistan is one of the positive outcomes of the intervention. This may put Afghanistan back on the road to independent nationhood one day. Germany was able to recover from the ravages of the Second World War. It is possible that through education Afghanistan will be able do so as well.

Works Cited

Alkire, S. “Human Development: Definitions, Critiques, and Related Concepts.” 2010.

Bundesministerium fur wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung. Vocational educataion and training in German development policy, BMZ Strategy Paper 8 . BMZ, Division Education. Berlin: Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperationa nd Development, 2012.

Carayannis, E., A. Pirzadeh and D. Popescu. Institutional Learning and Knowledge Transfer Across Epistemic Communities . Vol. 13. Springer, 2012.

Cohen, J. “Social, Emotional, Ethical, and Academic Education: Creating a Climate for Learning, Participation in Democracy, and Well-Being.” harvard educational Review 76.2 (2006).

Hirst, T. What is the secret of Germany’s success? 11 July 2014. 24 October 2017. <https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2014/07/germany-economic-success-world-cup/>.

Human Rights Watch. “I won’t be a Doctor, and one day you’ll be sick”: Girl’s Access to Education in Afghanistan . 17 October 2017. 24 October 2017. <https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/10/17/i-wont-be-doctor-and-one-day-youll-be-sick/girls-access-education-afghanistan>.

Kotthoff, H. “Between Excellence and Equity: The Case of the German Education System.” Revista Española de Educación Comparada 18 (2011): 27-60.

INSTANT PRICE

Get an instant price. no signup required.

We respect your privacy and confidentiality!

Share the excitement and get a 15% discount

Introduce your friends to The Uni Tutor and get rewarded when they order!

Refer Now >

FREE Resources

- APA Citation Generator

- Harvard Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- MLA Referencing Generator

- Oscola Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- Turabian Citation Generator

New to this Site? Download these Sample Essays

- Corporate Law Thesis

- Political Philosophy

- Legal Writing Rules

- Sample Philosophy Thesis

Send me free samples >

How The Order Process Works

- Order Your Work Online

- Tell us your specific requirements

- Pay for your order

- An expert will write your work

- You log in and download your work

- Order Complete

Amazing Offers from The Uni Tutor Sign up to our daily deals and don't miss out!

Contact Us At

- e-mail: info@theunitutor.com

- tel: +44 20 3286 9122

Brought to you by SiteJabber

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2002-2024 - The Uni Tutor - Custom Essays. 10347001, info@theunitutor.com, +44 20 3286 9122 , All Rights Reserved. - Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy

The Uni Tutor : We are a company registered in the United Kingdom. Registered Address London, UK , London , England , EC2N 1HQ

Why education matters for economic development

Harry a. patrinos.

Senior Adviser, Education

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

The World Bank Group is the largest financier of education in the developing world, working in 94 countries and committed to helping them reach SDG4: access to inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning opportunities for all by 2030.

Education is a human right, a powerful driver of development, and one of the strongest instruments for reducing poverty and improving health, gender equality, peace, and stability. It delivers large, consistent returns in terms of income, and is the most important factor to ensure equity and inclusion.

For individuals, education promotes employment, earnings, health, and poverty reduction. Globally, there is a 9% increase in hourly earnings for every extra year of schooling . For societies, it drives long-term economic growth, spurs innovation, strengthens institutions, and fosters social cohesion. Education is further a powerful catalyst to climate action through widespread behavior change and skilling for green transitions.

Developing countries have made tremendous progress in getting children into the classroom and more children worldwide are now in school. But learning is not guaranteed, as the 2018 World Development Report (WDR) stressed.

Making smart and effective investments in people’s education is critical for developing the human capital that will end extreme poverty. At the core of this strategy is the need to tackle the learning crisis, put an end to Learning Poverty , and help youth acquire the advanced cognitive, socioemotional, technical and digital skills they need to succeed in today’s world.

In low- and middle-income countries, the share of children living in Learning Poverty (that is, the proportion of 10-year-old children that are unable to read and understand a short age-appropriate text) increased from 57% before the pandemic to an estimated 70% in 2022.

However, learning is in crisis. More than 70 million more people were pushed into poverty during the COVID pandemic, a billion children lost a year of school , and three years later the learning losses suffered have not been recouped . If a child cannot read with comprehension by age 10, they are unlikely to become fluent readers. They will fail to thrive later in school and will be unable to power their careers and economies once they leave school.

The effects of the pandemic are expected to be long-lasting. Analysis has already revealed deep losses, with international reading scores declining from 2016 to 2021 by more than a year of schooling. These losses may translate to a 0.68 percentage point in global GDP growth. The staggering effects of school closures reach beyond learning. This generation of children could lose a combined total of US$21 trillion in lifetime earnings in present value or the equivalent of 17% of today’s global GDP – a sharp rise from the 2021 estimate of a US$17 trillion loss.

Action is urgently needed now – business as usual will not suffice to heal the scars of the pandemic and will not accelerate progress enough to meet the ambitions of SDG 4. We are urging governments to implement ambitious and aggressive Learning Acceleration Programs to get children back to school, recover lost learning, and advance progress by building better, more equitable and resilient education systems.

Last Updated: Mar 25, 2024

The World Bank’s global education strategy is centered on ensuring learning happens – for everyone, everywhere. Our vision is to ensure that everyone can achieve her or his full potential with access to a quality education and lifelong learning. To reach this, we are helping countries build foundational skills like literacy, numeracy, and socioemotional skills – the building blocks for all other learning. From early childhood to tertiary education and beyond – we help children and youth acquire the skills they need to thrive in school, the labor market and throughout their lives.

Investing in the world’s most precious resource – people – is paramount to ending poverty on a livable planet. Our experience across more than 100 countries bears out this robust connection between human capital, quality of life, and economic growth: when countries strategically invest in people and the systems designed to protect and build human capital at scale, they unlock the wealth of nations and the potential of everyone.

Building on this, the World Bank supports resilient, equitable, and inclusive education systems that ensure learning happens for everyone. We do this by generating and disseminating evidence, ensuring alignment with policymaking processes, and bridging the gap between research and practice.

The World Bank is the largest source of external financing for education in developing countries, with a portfolio of about $26 billion in 94 countries including IBRD, IDA and Recipient-Executed Trust Funds. IDA operations comprise 62% of the education portfolio.

The investment in FCV settings has increased dramatically and now accounts for 26% of our portfolio.

World Bank projects reach at least 425 million students -one-third of students in low- and middle-income countries.

The World Bank’s Approach to Education

Five interrelated pillars of a well-functioning education system underpin the World Bank’s education policy approach:

- Learners are prepared and motivated to learn;

- Teachers are prepared, skilled, and motivated to facilitate learning and skills acquisition;

- Learning resources (including education technology) are available, relevant, and used to improve teaching and learning;

- Schools are safe and inclusive; and

- Education Systems are well-managed, with good implementation capacity and adequate financing.

The Bank is already helping governments design and implement cost-effective programs and tools to build these pillars.

Our Principles:

- We pursue systemic reform supported by political commitment to learning for all children.

- We focus on equity and inclusion through a progressive path toward achieving universal access to quality education, including children and young adults in fragile or conflict affected areas , those in marginalized and rural communities, girls and women , displaced populations, students with disabilities , and other vulnerable groups.

- We focus on results and use evidence to keep improving policy by using metrics to guide improvements.

- We want to ensure financial commitment commensurate with what is needed to provide basic services to all.

- We invest wisely in technology so that education systems embrace and learn to harness technology to support their learning objectives.

Laying the groundwork for the future

Country challenges vary, but there is a menu of options to build forward better, more resilient, and equitable education systems.

Countries are facing an education crisis that requires a two-pronged approach: first, supporting actions to recover lost time through remedial and accelerated learning; and, second, building on these investments for a more equitable, resilient, and effective system.

Recovering from the learning crisis must be a political priority, backed with adequate financing and the resolve to implement needed reforms. Domestic financing for education over the last two years has not kept pace with the need to recover and accelerate learning. Across low- and lower-middle-income countries, the average share of education in government budgets fell during the pandemic , and in 2022 it remained below 2019 levels.

The best chance for a better future is to invest in education and make sure each dollar is put toward improving learning. In a time of fiscal pressure, protecting spending that yields long-run gains – like spending on education – will maximize impact. We still need more and better funding for education. Closing the learning gap will require increasing the level, efficiency, and equity of education spending—spending smarter is an imperative.

- Education technology can be a powerful tool to implement these actions by supporting teachers, children, principals, and parents; expanding accessible digital learning platforms, including radio/ TV / Online learning resources; and using data to identify and help at-risk children, personalize learning, and improve service delivery.

Looking ahead

We must seize this opportunity to reimagine education in bold ways. Together, we can build forward better more equitable, effective, and resilient education systems for the world’s children and youth.

Accelerating Improvements

Supporting countries in establishing time-bound learning targets and a focused education investment plan, outlining actions and investments geared to achieve these goals.

Launched in 2020, the Accelerator Program works with a set of countries to channel investments in education and to learn from each other. The program coordinates efforts across partners to ensure that the countries in the program show improvements in foundational skills at scale over the next three to five years. These investment plans build on the collective work of multiple partners, and leverage the latest evidence on what works, and how best to plan for implementation. Countries such as Brazil (the state of Ceará) and Kenya have achieved dramatic reductions in learning poverty over the past decade at scale, providing useful lessons, even as they seek to build on their successes and address remaining and new challenges.

Universalizing Foundational Literacy

Readying children for the future by supporting acquisition of foundational skills – which are the gateway to other skills and subjects.

The Literacy Policy Package (LPP) consists of interventions focused specifically on promoting acquisition of reading proficiency in primary school. These include assuring political and technical commitment to making all children literate; ensuring effective literacy instruction by supporting teachers; providing quality, age-appropriate books; teaching children first in the language they speak and understand best; and fostering children’s oral language abilities and love of books and reading.

Advancing skills through TVET and Tertiary

Ensuring that individuals have access to quality education and training opportunities and supporting links to employment.

Tertiary education and skills systems are a driver of major development agendas, including human capital, climate change, youth and women’s empowerment, and jobs and economic transformation. A comprehensive skill set to succeed in the 21st century labor market consists of foundational and higher order skills, socio-emotional skills, specialized skills, and digital skills. Yet most countries continue to struggle in delivering on the promise of skills development.

The World Bank is supporting countries through efforts that address key challenges including improving access and completion, adaptability, quality, relevance, and efficiency of skills development programs. Our approach is via multiple channels including projects, global goods, as well as the Tertiary Education and Skills Program . Our recent reports including Building Better Formal TVET Systems and STEERing Tertiary Education provide a way forward for how to improve these critical systems.

Addressing Climate Change

Mainstreaming climate education and investing in green skills, research and innovation, and green infrastructure to spur climate action and foster better preparedness and resilience to climate shocks.

Our approach recognizes that education is critical for achieving effective, sustained climate action. At the same time, climate change is adversely impacting education outcomes. Investments in education can play a huge role in building climate resilience and advancing climate mitigation and adaptation. Climate change education gives young people greater awareness of climate risks and more access to tools and solutions for addressing these risks and managing related shocks. Technical and vocational education and training can also accelerate a green economic transformation by fostering green skills and innovation. Greening education infrastructure can help mitigate the impact of heat, pollution, and extreme weather on learning, while helping address climate change.

Examples of this work are projects in Nigeria (life skills training for adolescent girls), Vietnam (fostering relevant scientific research) , and Bangladesh (constructing and retrofitting schools to serve as cyclone shelters).

Strengthening Measurement Systems

Enabling countries to gather and evaluate information on learning and its drivers more efficiently and effectively.

The World Bank supports initiatives to help countries effectively build and strengthen their measurement systems to facilitate evidence-based decision-making. Examples of this work include:

(1) The Global Education Policy Dashboard (GEPD) : This tool offers a strong basis for identifying priorities for investment and policy reforms that are suited to each country context by focusing on the three dimensions of practices, policies, and politics.

- Highlights gaps between what the evidence suggests is effective in promoting learning and what is happening in practice in each system; and

- Allows governments to track progress as they act to close the gaps.

The GEPD has been implemented in 13 education systems already – Peru, Rwanda, Jordan, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Mozambique, Islamabad, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Sierra Leone, Niger, Gabon, Jordan and Chad – with more expected by the end of 2024.

(2) Learning Assessment Platform (LeAP) : LeAP is a one-stop shop for knowledge, capacity-building tools, support for policy dialogue, and technical staff expertise to support student achievement measurement and national assessments for better learning.

Supporting Successful Teachers

Helping systems develop the right selection, incentives, and support to the professional development of teachers.

Currently, the World Bank Education Global Practice has over 160 active projects supporting over 18 million teachers worldwide, about a third of the teacher population in low- and middle-income countries. In 12 countries alone, these projects cover 16 million teachers, including all primary school teachers in Ethiopia and Turkey, and over 80% in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Vietnam.

A World Bank-developed classroom observation tool, Teach, was designed to capture the quality of teaching in low- and middle-income countries. It is now 3.6 million students.

While Teach helps identify patterns in teacher performance, Coach leverages these insights to support teachers to improve their teaching practice through hands-on in-service teacher professional development (TPD).

Our recent report on Making Teacher Policy Work proposes a practical framework to uncover the black box of effective teacher policy and discusses the factors that enable their scalability and sustainability.

Supporting Education Finance Systems

Strengthening country financing systems to mobilize resources for education and make better use of their investments in education.

Our approach is to bring together multi-sectoral expertise to engage with ministries of education and finance and other stakeholders to develop and implement effective and efficient public financial management systems; build capacity to monitor and evaluate education spending, identify financing bottlenecks, and develop interventions to strengthen financing systems; build the evidence base on global spending patterns and the magnitude and causes of spending inefficiencies; and develop diagnostic tools as public goods to support country efforts.

Working in Fragile, Conflict, and Violent (FCV) Contexts

The massive and growing global challenge of having so many children living in conflict and violent situations requires a response at the same scale and scope. Our education engagement in the Fragility, Conflict and Violence (FCV) context, which stands at US$5.35 billion, has grown rapidly in recent years, reflecting the ever-increasing importance of the FCV agenda in education. Indeed, these projects now account for more than 25% of the World Bank education portfolio.

Education is crucial to minimizing the effects of fragility and displacement on the welfare of youth and children in the short-term and preventing the emergence of violent conflict in the long-term.

Support to Countries Throughout the Education Cycle

Our support to countries covers the entire learning cycle, to help shape resilient, equitable, and inclusive education systems that ensure learning happens for everyone.

The ongoing Supporting Egypt Education Reform project , 2018-2025, supports transformational reforms of the Egyptian education system, by improving teaching and learning conditions in public schools. The World Bank has invested $500 million in the project focused on increasing access to quality kindergarten, enhancing the capacity of teachers and education leaders, developing a reliable student assessment system, and introducing the use of modern technology for teaching and learning. Specifically, the share of Egyptian 10-year-old students, who could read and comprehend at the global minimum proficiency level, increased to 45 percent in 2021.

In Nigeria , the $75 million Edo Basic Education Sector and Skills Transformation (EdoBESST) project, running from 2020-2024, is focused on improving teaching and learning in basic education. Under the project, which covers 97 percent of schools in the state, there is a strong focus on incorporating digital technologies for teachers. They were equipped with handheld tablets with structured lesson plans for their classes. Their coaches use classroom observation tools to provide individualized feedback. Teacher absence has reduced drastically because of the initiative. Over 16,000 teachers were trained through the project, and the introduction of technology has also benefited students.

Through the $235 million School Sector Development Program in Nepal (2017-2022), the number of children staying in school until Grade 12 nearly tripled, and the number of out-of-school children fell by almost seven percent. During the pandemic, innovative approaches were needed to continue education. Mobile phone penetration is high in the country. More than four in five households in Nepal have mobile phones. The project supported an educational service that made it possible for children with phones to connect to local radio that broadcast learning programs.

From 2017-2023, the $50 million Strengthening of State Universities in Chile project has made strides to improve quality and equity at state universities. The project helped reduce dropout: the third-year dropout rate fell by almost 10 percent from 2018-2022, keeping more students in school.

The World Bank’s first Program-for-Results financing in education was through a $202 million project in Tanzania , that ran from 2013-2021. The project linked funding to results and aimed to improve education quality. It helped build capacity, and enhanced effectiveness and efficiency in the education sector. Through the project, learning outcomes significantly improved alongside an unprecedented expansion of access to education for children in Tanzania. From 2013-2019, an additional 1.8 million students enrolled in primary schools. In 2019, the average reading speed for Grade 2 students rose to 22.3 words per minute, up from 17.3 in 2017. The project laid the foundation for the ongoing $500 million BOOST project , which supports over 12 million children to enroll early, develop strong foundational skills, and complete a quality education.

The $40 million Cambodia Secondary Education Improvement project , which ran from 2017-2022, focused on strengthening school-based management, upgrading teacher qualifications, and building classrooms in Cambodia, to improve learning outcomes, and reduce student dropout at the secondary school level. The project has directly benefited almost 70,000 students in 100 target schools, and approximately 2,000 teachers and 600 school administrators received training.

The World Bank is co-financing the $152.80 million Yemen Restoring Education and Learning Emergency project , running from 2020-2024, which is implemented through UNICEF, WFP, and Save the Children. It is helping to maintain access to basic education for many students, improve learning conditions in schools, and is working to strengthen overall education sector capacity. In the time of crisis, the project is supporting teacher payments and teacher training, school meals, school infrastructure development, and the distribution of learning materials and school supplies. To date, almost 600,000 students have benefited from these interventions.

The $87 million Providing an Education of Quality in Haiti project supported approximately 380 schools in the Southern region of Haiti from 2016-2023. Despite a highly challenging context of political instability and recurrent natural disasters, the project successfully supported access to education for students. The project provided textbooks, fresh meals, and teacher training support to 70,000 students, 3,000 teachers, and 300 school directors. It gave tuition waivers to 35,000 students in 118 non-public schools. The project also repaired 19 national schools damaged by the 2021 earthquake, which gave 5,500 students safe access to their schools again.

In 2013, just 5% of the poorest households in Uzbekistan had children enrolled in preschools. Thanks to the Improving Pre-Primary and General Secondary Education Project , by July 2019, around 100,000 children will have benefitted from the half-day program in 2,420 rural kindergartens, comprising around 49% of all preschool educational institutions, or over 90% of rural kindergartens in the country.

In addition to working closely with governments in our client countries, the World Bank also works at the global, regional, and local levels with a range of technical partners, including foundations, non-profit organizations, bilaterals, and other multilateral organizations. Some examples of our most recent global partnerships include:

UNICEF, UNESCO, FCDO, USAID, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: Coalition for Foundational Learning

The World Bank is working closely with UNICEF, UNESCO, FCDO, USAID, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation as the Coalition for Foundational Learning to advocate and provide technical support to ensure foundational learning. The World Bank works with these partners to promote and endorse the Commitment to Action on Foundational Learning , a global network of countries committed to halving the global share of children unable to read and understand a simple text by age 10 by 2030.

Australian Aid, Bernard van Leer Foundation, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Canada, Echida Giving, FCDO, German Cooperation, William & Flora Hewlett Foundation, Conrad Hilton Foundation, LEGO Foundation, Porticus, USAID: Early Learning Partnership

The Early Learning Partnership (ELP) is a multi-donor trust fund, housed at the World Bank. ELP leverages World Bank strengths—a global presence, access to policymakers and strong technical analysis—to improve early learning opportunities and outcomes for young children around the world.

We help World Bank teams and countries get the information they need to make the case to invest in Early Childhood Development (ECD), design effective policies and deliver impactful programs. At the country level, ELP grants provide teams with resources for early seed investments that can generate large financial commitments through World Bank finance and government resources. At the global level, ELP research and special initiatives work to fill knowledge gaps, build capacity and generate public goods.

UNESCO, UNICEF: Learning Data Compact

UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank have joined forces to close the learning data gaps that still exist and that preclude many countries from monitoring the quality of their education systems and assessing if their students are learning. The three organizations have agreed to a Learning Data Compact , a commitment to ensure that all countries, especially low-income countries, have at least one quality measure of learning by 2025, supporting coordinated efforts to strengthen national assessment systems.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS): Learning Poverty Indicator

Aimed at measuring and urging attention to foundational literacy as a prerequisite to achieve SDG4, this partnership was launched in 2019 to help countries strengthen their learning assessment systems, better monitor what students are learning in internationally comparable ways and improve the breadth and quality of global data on education.

FCDO, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: EdTech Hub

Supported by the UK government’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), in partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the EdTech Hub is aimed at improving the quality of ed-tech investments. The Hub launched a rapid response Helpdesk service to provide just-in-time advisory support to 70 low- and middle-income countries planning education technology and remote learning initiatives.

MasterCard Foundation

Our Tertiary Education and Skills global program, launched with support from the Mastercard Foundation, aims to prepare youth and adults for the future of work and society by improving access to relevant, quality, equitable reskilling and post-secondary education opportunities. It is designed to reframe, reform, and rebuild tertiary education and skills systems for the digital and green transformation.

Bridging the AI divide: Breaking down barriers to ensure women’s leadership and participation in the Fifth Industrial Revolution

Common challenges and tailored solutions: How policymakers are strengthening early learning systems across the world

Compulsory education boosts learning outcomes and climate action

Areas of focus.

Data & Measurement

Early Childhood Development

Financing Education

Foundational Learning

Fragile, Conflict & Violent Contexts

Girls’ Education

Inclusive Education

Skills Development

Technology (EdTech)

Tertiary Education

Initiatives

- Show More +

- Tertiary Education and Skills Program

- Service Delivery Indicators

- Evoke: Transforming education to empower youth

- Global Education Policy Dashboard

- Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel

- Show Less -

Collapse and Recovery: How the COVID-19 Pandemic Eroded Human Capital and What to Do About It

BROCHURES & FACT SHEETS

Flyer: Education Factsheet - May 2024

Publication: Realizing Education's Promise: A World Bank Retrospective – August 2023

Flyer: Education and Climate Change - November 2022

Brochure: Learning Losses - October 2022

STAY CONNECTED

Human Development Topics

Around the bank group.

Find out what the Bank Group's branches are doing in education

Global Education Newsletter - April 2024

What's happening in the World Bank Education Global Practice? Read to learn more.

Human Capital Project

The Human Capital Project is a global effort to accelerate more and better investments in people for greater equity and economic growth.

Impact Evaluations

Research that measures the impact of education policies to improve education in low and middle income countries.

Education Videos

Watch our latest videos featuring our projects across the world

Additional Resources

Education Finance

Higher Education

Digital Technologies

Education Data & Measurement

Education in Fragile, Conflict & Violence Contexts

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

The Role of Education in Development

- First Online: 30 August 2019

Cite this chapter

- Tristan McCowan 6

Part of the book series: Palgrave Studies in Global Higher Education ((PSGHE))

1784 Accesses

1 Citations

Understanding the role of education in development is highly complex, on account of the slippery nature of both concepts, and the multifaceted relationship between them. This chapter provides a conceptual exploration of these relationships, laying the groundwork for the rest of the book. First, it assesses the role of education as a driver of development, including aspects of economic growth, basic needs and political participation. Second, it looks at the constitutive perspective, involving education as national status, human right and human development. Finally, it assesses the ‘other face’ of education and its negative impacts, as well as the specificities of higher education in relation to other levels.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Almond, G., & Verba, S. (1963). The civic culture: Political attitudes and democracy five nations . London: Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Becker, G. S. (1962, October). Investment in human capital: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 70 (Suppl.), 9–49.

Article Google Scholar

Beckett, K. (2011). R. S. Peters and the concept of education. Educational Theory, 61 (3), 239–255.

Bengtsson, S., Barakat, B., & Muttarak, R. (2018). The role of education in enabling the sustainable development agenda . London: Routledge.

Boni, A., Lopez-Fogues, A., & Walker, M. (2016). Higher education and the post 2015 agenda: A contribution from the human development approach. Journal of Global Ethics, 12 (1), 17–28.

Google Scholar

Boni, A., & Walker, M. (2013). Human development and capabilities: Re-imagining the university of the twenty-first century . London: Routledge.

Boni, A., & Walker, M. (2016). Universities and global human development: Theoretical and empirical insights for social change . London: Routledge.

Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (1976). Schooling in capitalist America: Educational reform and the contradictions of economic life . New York: Basic Books.

Bush, K., & Saltarelli, D. (2000). The two faces of education in ethnic conflict . Paris: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre.

Brundtland Commission. (1987). Our common future (Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bynner, J., Dolton, P., Feinstein, L., Makepiece, G., Malmberg, L., & Woods, L. (2003). Revisiting the benefits of higher education: A report by the Bedford Group for Lifecourse and Statistical Studies, Institute of Education . Bristol: Higher Education Funding Council for England.

Castells, M. (1994). The university system: Engine of development in the new world economy. In J. Salmi & A. Verspoor (Eds.), Revitalizing higher education (pp. 14–40). Oxford: Pergamon.

Coleman, J. S., Campbell, E. Q., Hobson, C. F., McPartland, J., Mood, A. M., Weinfeld, F. D., et al. (1966). Equality of educational opportunity . Washington, DC: U. S. Office of Education.

Dewey, J. (1966 [1916]). Democracy and education . New York: MacMillan.

Diamond, J. M. (1997). Guns germs and steel: The fate of human societies . New York: W. W. Norton.

Fraser, N. (1998). From redistribution to recognition? Dilemmas of justice in a ‘post-socialist’ age. In A. Philipps (Ed.), Feminism and politics . New York: Oxford University Press.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed . London: Penguin Books.

Garrod, N., & Macfarlane, B. (2009). Challenging boundaries: Managing the integration of post-secondary education . Abingdon: Routledge.

Giroux, H., & McLaren, P. (1986). Teacher education and the politics of engagement: The case for democratic schooling. Harvard Educational Review, 56 (3), 213–240.

Green, A. (1990). Education and state formation: the rise of education systems in England, France and the USA . London: Macmillan.

Hanushek, E. (2013). Economic growth in developing countries: The role of human capital. Economics of Education Review, 73, 204–212.

Hanushek, E., & Woessmann, L. (2008). The role of cognitive skills in economic development. Journal of Economic Literature, 46 (3), 607–668.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom . London: Routledge.

Huntington, S., & Nelson, J. (1976). No easy choice: Political participation in developing countries . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Klees, S. J. (2016). Human capital and rates of return: Brilliant ideas or ideological dead ends? Comparative Education Review, 60 (4), 644–672.

Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22 (1), 3–42.

Luescher-Mamashela, T. M., Kiiru, S., Mattes, R., Mwollo-ntallima, A., Ng’ethe, N., & Romo, M. (2011). The university in Africa and democratic citizenship: Hothouse or training ground? Wynberg: Centre for Higher Education Transformation.

Mamdani, M. (2018). The African university. London Review of Books, 40 (14), 29–32.

Marginson, S. (2016). The worldwide trend to high participation higher education: Dynamics of social stratification in inclusive systems. Higher Education, 72, 413–434.

Marginson, S. (2017). Limitations of human capital theory. Studies in Higher Education, 44 (2), 287–301.

Martin, C. (2018). Political authority, personal autonomy and higher education. Philosophical Inquiry in Education, 25 (2), 154–170.

Mazrui, A. A. (1975). The African university as a multinational corporation: Problems of penetration and dependency. Harvard Educational Review, 45, 198.

McCowan, T. (2004). The growth of private higher education in Brazil: Implications for equity and quality. Journal of Education Policy, 19 (4), 453–472.

McCowan, T. (2009). Rethinking citizenship education: A curriculum for participatory democracy . London: Continuum.

McCowan, T. (2013). Education as a human right: Principles for a universal entitlement to learning . London: Bloomsbury.

McCowan, T. (2015). Theories of development. In T. McCowan & E. Unterhalter (Eds.), Education and international development: An introduction . London: Bloomsbury.

McCowan, T., Ananga, E., Oanda, I., Sifuna, D., Ongwenyi, Z., Adedeji, S., et al. (2015). Students in the driving seat: Young people’s views on higher education in Africa (Research Report). Manchester: British Council.

McGrath, S. (2010). The role of education in development: An educationalist’s response to some recent work in development economics. Comparative Education, 46, 237–253.

McGrath, S. (2014). The post-2015 debate and the place of education in development thinking. International Journal of Educational Development, 39, 4–11.

McMahon, W. W. (2009). Higher learning, greater good . Baltimore: John Hopkins Press.

Milbrath, L., & Goel, M. (1977). Political participation: How and why do people get involved in politics? (2nd ed.). Chicago: Rand McNally College.

Milton, S. (2019). Syrian higher education during conflict: Survival, protection, and regime security. International Journal of Educational Development, 64, 38–47.

Milton, S., & Barakat, S. (2016). Higher education as the catalyst of recovery in conflict-affected societies. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 14 (3), 403–421.

Mincer, J. (1981). Human capital and economic growth (Working Paper 80). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w0803.pdf .

Newman, J. H. (1947 [1852]). The idea of the university: Defined and illustrated . London: Longmans, Green.

Novelli, M., & Lopez Cardozo, M. (2008). Conflict, education and the global south: New critical directions. International Journal of Educational Development, 28 (4), 473–488.

Nussbaum, M. (2000). Women and human development: The capabilities approach . Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Oketch, M. O., McCowan, T., & Schendel, R. (2014). The impact of tertiary education on development: A rigorous literature review . London: Department for International Development.

Parsons, S., & Bynner, J. (2002). Basic skills and political and community participation: Findings from a study of adults born in 1958 and 1970 . London: Basic Skills Agency.

Perkin, H. (2007). History of universities. In J. J. F. Forest & P. G. Altbach (Eds.), International handbook of higher education (pp. 159–206). Dordrecht: Springer.

Peters, R. S. (1966). Ethics and education . London: George Allen and Unwin.

Pherali, T., & Lewis, A. (2019). Developing global partnerships in higher education for peacebuilding: A strategy for pathways to impact. Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00367-7 .

Prakash, M. S., & Esteva, G. (2008). Escaping education: Living as learning in grassroots cultures (2nd ed.). New York: Peter Lang.

Rist, G. (2002). The history of development: From western origins to global faith . London: Zed Books.

Robertson, S. (2016). Piketty, capital and education: A solution to, or problem in, rising social inequalities? British Journal of Sociology of Education, 37 (6), 823–835.

Romer, P. M. (1986). Increasing returns and long-run growth. The Journal of Political Economy, 94 (5), 1002–1037.

Sachs, J. D. (2008). Common wealth: Economics . New York: Penguin Press.

Santos, B. de S. (2015). Epistemologies of the south: Justice against epistemicide . New York: Routledge.

Schultz, T. W. (1961). Investment in human capital. American Economic Review, 51, 1–17.

Sen, A. (1992). Inequality re-examined . Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sen, A. (1999a). Development as freedom . New York: Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (1999b). Democracy as a universal value. Journal of Democracy, 10 (3), 3–17.

Smith, A., & Vaux, T. (2003). Education, conflict and international development . London: DFID.

Stewart, F. (1985). Planning to meet basic needs . London: Macmillan.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2007). Making globalization work . London: Allen Lane.

Streeten, P. (1977). The basic features of a basic needs approach to development. International Development Review, 3, 8–16.

Takayama, K., Sriprakash, A., & Connell, R. (2015). Rethinking Knowledge production and circulation in comparative and international education: Southern theory, postcolonial perspectives, and alternative epistemologies. Comparative Education Review , 59 (1), v–viii.

Tilak, J. B. G. (2003). Higher education and development in Asia. Journal of Educational Planning and Administration, 17 (2), 151–173.

Tomaševski, K. (2001). Human rights obligations: Making education available, accessible, acceptable and adaptable. Right to Education Primers No. 3. Gothenburg: Novum Grafiska.

Unterhalter, E. (2003). The capabilities approach and gendered education: An examination of South African complexities. Theory and Research in Education, 1 (1), 7–22.

Willis, P. (1978). Learning to Labour: How working class kids get working class jobs . Aldershot Gower: Saxon House/Teakfield.

Winch, C. (2006). Graduate attributes and changing conceptions of learning. In P. Hager & S. Holland (Eds.), Graduate attributes, learning and employability (pp. 67–89). Dordrecht: Springer.

Wolff, J., & de-Shalit, A. (2013). On fertile functionings: A response to Martha Nussbaum. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 14(1), 161–165.

World Bank. (1999). Knowledge for development. World Development Report. New York: Oxford University Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

UCL Institute of Education, London, UK

Tristan McCowan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tristan McCowan .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

McCowan, T. (2019). The Role of Education in Development. In: Higher Education for and beyond the Sustainable Development Goals. Palgrave Studies in Global Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19597-7_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19597-7_2

Published : 30 August 2019

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-19596-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-19597-7

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Transforming lives through education

Transforming education to change our world

UNESCO provides global and regional leadership on all aspects of education from pre-school to higher education and throughout life. It works through its Member States and brings together governments, the private sector and civil society to strengthen education systems worldwide in order to deliver quality education for all. As a thought leader it publishes landmark reports and data for policy-makers, implements programmes on the ground from teacher training to emergency responses and establishes and monitors norms and standards for all to guide educational developments.

Right to education in a ruined world

Southern Italy, 1950. Three children are huddled around a makeshift desk made out of reclaimed wood, scribbling in their notebooks. The classroom has an earthen floor and roughly clad walls. The children’s clothes are ragged. They are wearing home-made slippers because shoes and the money to buy them are rare commodities in the war-ravaged south.

Although World War II ended five years earlier, the scars of conflict are still visible in this black and white photo from a report commissioned by UNESCO from legendary photojournalist David Seymour.

At the time when the photograph was taken, less than half of Italy’s population could read and write and just a third completed primary school. 70 years later, these children’s grandchildren enjoy an over 99% literacy rate. In the wake of the war, UNESCO led a major education campaign in Europe to respond to the education crisis, to rebuild links between people and to strengthen democracy and cultural identities after years of conflict. The emphasis then was on the fundamental learning skill of literacy.

Immediately after World War two UNESCO led a major education campaign in Europe to respond to the education crisis, fix and rebuild links between people and strengthen cultural identities after years of conflict. David Seymour’s images show the extent of the fight against illiteracy led by the post-war Italian government and non-governmental organisations backed by UNESCO.

Looking back at the deprived surroundings Seymour captured in his photo essay, one can see the extent of success. Seventy-one years later, those children’s grandchildren enjoy a 99.16 per cent literacy rate.

Similar programmes were held across the globe, for instance in devastated Korea where UNESCO led a major education textbook production programme in the 1950s. Several decades after, the former Secretary-General of the United Nations and Korean citizen Ban Ki-Moon expressed the importance of such a programme for the country's development:

The flowering of literacy

In a Korea devastated by war and where UNESCO led a major education textbook production programme in the 1950s, one student, Ban Ki-Moon, now Former Secretary-General of the United Nations, saw the world open up to him through the pages of a UNESCO textbook. Several decades after, he expressed the importance of such a programme for his country's development on the world stage.

Reaching the remote villages perched atop the Andes in Peru during the early 1960s wasn’t without its challenges for UNESCO’s technical assistance programme to bring literacy to disadvantaged communities. While Peru’s economy was experiencing a prolonged period of expansion, not all Peruvians were able to benefit from this growth which was limited to the industrialised coast. Instead, Andes communities were grappling with poverty, illiteracy and depopulation.

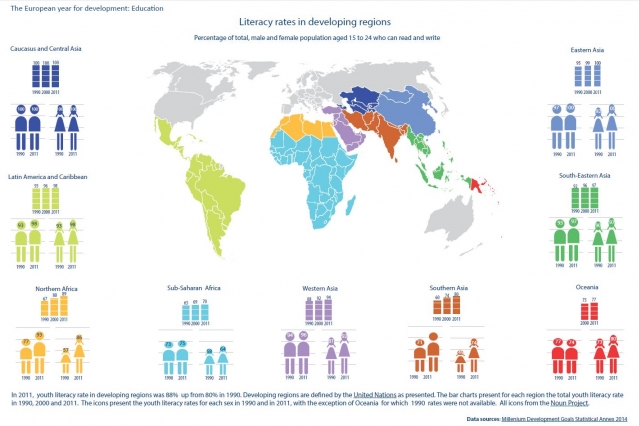

Today, the number of non-literate youths and adults around the world has decreased dramatically, while the global literacy rate for young people aged 15-24 years has reached 92 %. These astonishing successes reflect improved access to schooling for younger generations.

Photojournalist Paul Almasy has left us the poignant image of a barefoot older man while he’s deciphering a newspaper thanks to his newfound literacy skills.

The classroom at the UNESCO mission in Chinchera, in the Andean highlands of Peru, had allowed the old man to discover the world beyond his tiny village.

However, there are still huge obstacles to overcome. Data from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics shows that 617 million children and adolescents worldwide are not achieving minimum proficiency levels in reading and mathematics. Since the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015 it is still the case that globally more than 450 million children - six out of 10 - have failed to gain basic literacy skills by the age of 10. And beyond literacy programmes, massive investments in skills for work and life, teacher training, and education policies are needed in a world that is changing ever faster.

Global priorities

Africa, home to the world’s youngest population, is not on track to achieve the targets of SDG 4. Sub-Saharan Africa alone is expected to account for 25% of the school-age population by 2030, up from 12% in 1990, yet it remains the region with the highest out-of-school rates. Girls are more likely to be permanently excluded from education than boys. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated inequalities, with 89% of learners not having access to computers and 82% lacking internet access to benefit from distance learning. The lack of trained teachers further jeopardizes progress towards SDG4: pre-pandemic only 64% of whom were trained at the primary level and 58% at the lower secondary level.

As part of its Priority Africa Flagship 2022 – 2029 , UNESCO has launched Campus Africa: Reinforcing Higher Education in Africa with the objective to build integrated, inclusive, and quality tertiary education systems and institutions, for the development of inclusive and equitable societies on the continent.

Gender

There are immense gender gaps when it comes to access, learning achievement and education, most often at the expense of girls and women. It is estimated that some 127 million girls are out of school around the world. For many girls and women around the world, the classroom remains an elusive, often forbidden space. UNESCO monitors the educational rights of girls and women around the world and shares information on the legal progress toward securing the right to education for women in all countries. Despite important progress in recent decades, the right to education is still far from being a reality for many girls and women. Discriminatory practices stand in the way of girls and women fully exercising their right to participate in, complete, and benefit from education. And while girls have difficulty with access, boys face increasing challenges, and particularly disengagement , from education at later stages. Globally only 88 men are enrolled in tertiary education for every 100 women. In 73 countries, fewer boys than girls are enrolled in upper-secondary education.

UNESCO's Her Atlas analyzes the legal frameworks of nearly 200 states to track which laws are enabling---or inhibiting---the right to education for girls and women. This interactive world map uses a color-coded scoring system to monitor 12 indicators of legal progress towards gender equality in the right to education.

Monitoring the right to education for girls and women

What makes me proud is that soon I will finish building a new house. I have already been able to buy a cow and I will soon be able to have another pond

Madagascar’s coastal Atsinanana region is known for its lush rainforests and fish breeding.

The country has a young population, but only one out of three children can complete primary education. Among those who are able to finish primary school, only 17% have minimum reading skills, while just a fifth of them have basic maths competencies. Once they leave school, children face a precarious labour market and unstable jobs, just like their parents.

Natacha Obienne is only 21 years old, but she is already in charge of a small fish farm, a career that is usually pursued by men. As one of the many out-of-school women in her area, she was able to set up her own business after vocational training taught her the basics of financial management and entrepreneurship, as well as the practicalities of breeding fish.

She understood that fish feeding depends on the temperature of the water. If it’s well managed, a higher number of fish is produced. ‘I immediately applied everything I learnt’ she says.

The classroom she attended changed the course of her life and she hopes other young people will follow in her footsteps.

I no longer depend on my parents and I am financially independent

She’s not alone. Around 3,000 youths in Madagascar have been trained since the start of the UNESCO-backed programme, some of whom have set up their own business and achieved financial independence. Education was the best way to ease people's emancipation.

Like Emma Claudia, 25, who after her vocational training started a restaurant with just a baking tray and a saucepan.

What does my family think? They are surprised and amazed by my evolution because I haven’t been able to complete my studies. I don’t have any school diplomas.

While Natacha and Emma Claudia have been able to transform their world through education, millions of children out of school around the world are still denied that dream.

Discrimination against girls remains widespread and nearly one billion adults, mostly women, are illiterate. The lack of qualified teachers and learning materials continues to be the reality in too many schools.

Challenging these obstacles is getting harder as the world grapples with the acceleration of climate change, the emergence of digitization and artificial intelligence, and the increasing exclusion and uncertainty brought by the Covid-19 pandemic.

We resumed school a while ago and it’s been stressful. We are trying to retrieve what we lost during quarantine, the worst thing about not being in school is the number of things you miss. Learning behind a screen and learning in person are incomparable.

Aicha is lucky to be able to continue her education. Her country has the highest rate of out-of-school children in the world – 10.5 million – and nearly two-thirds are women. To compound the problem, Nigeria’s northern states suffer from the violence that targets education.

In Russia, too, Alexander and his school friends had to cope with virtual learning and the lack of interactions.

All Russian students were moved to online studying. Needless to say, it was a rough year for all of us, several friends were struggling with depressive moods. They were missing their friends and teachers. So did I.

To protect their right to education during this unprecedented disruption and beyond, UNESCO has launched the Global Education Coalition , a platform for collaboration and exchange that brings together more than 175 countries from the UN family, civil society, academia and the private sector to ensure that learning never stops.

Building skills where they are most needed

Crouched over a pedal-powered sewing machine, Harikala Buda looks younger than her 30 years. Her slim fingers fold a cut of turquoise brocade before deftly pushing it under the needle mechanism.

Harikala lives in rural Nepal, where many villagers, particularly women, don’t have access to basic education. Women like Harikala rely on local community UNESCO-supported learning centres to receive literacy and tailoring skills. In a country where 32% of people over 15 are illiterate, particularly women and those living in rural areas, education is the only route to becoming self-reliant.

I have saved a small amount. My husband’s income goes towards running the house, mine is saved. We must save today to secure our children’s future

Having access to a classroom is the first step to creating a better world for the student, the student’s children and the student’s community. This is a lesson that matters a lot to

Kalasha Khadka Khatri, a 30-year-old Nepali mother. She grew up in a family of 21, with no option to go to school. Two of her children didn’t survive infancy because she was unable to pay for medical treatment. After acquiring sewing skills at her local community learning centre, Kalasha can now provide for her family.

Harikala and Kalasha were able to learn their skills through the support of the UNESCO’s Capacity Development for Education Programme (CapED), an initiative that operates in some 26 least-developed and fragile countries.

Reimagining the future of education

As the world slowly recovers after the COVID-19 crisis, 244 million children and youth worldwide are still out of school. And a 2022 survey by UNESCO, UNICEF, World Bank and OECD finds that one quarter of countries have yet to collect information on children who have and have not returned to school since the pandemic started.

Rebuilding how and where we learn requires policy advice, stronger education legislation, funds mobilisation, advocacy, targeted programme implementation based on sound analysis, statistics and global information sharing. Quality education also calls for the teaching of skills far beyond literacy and maths, including critical thinking against fake news in the digital era, living in harmony with nature and the ethics of artificial intelligence, to name a few of the critical skills needed in the 21st century.

UNESCO captured the debate around the futures of education in its landmark report from 2022 entitled Reimagining our futures together: A new social contract for education.

The Transformative Education Summit , that took place during the United Nations General Assembly in September 2022, as well as the Pre-Summit hosted by UNESCO to forge new approaches to education after the COVID-19 crisis, address the toughest bottlenecks to achieving SDG 4 and inspire young people to lead a global movement for education. World leaders committed to put education at the top of the political agenda. UNESCO has been mobilizing and consulting all stakeholders and partners to galvanize the transformation of every aspect of learning. UNESCO launched a number of key initiatives such as expanding public digital learning, making education responsive to the climate and environmental emergency, and improving access for crisis-affected children and youth.

The two children sitting at their makeshift desk in Italy in 1950 could not have imagined what a modern learning space might look like or how a modern curriculum or the tools and teacher training to deliver it might have been thought out and shaped to offer them the most from education. They could not have imagined the global drive to ensure that everyone was given a chance to learn throughout life. The only thing that has not changed since the photo was taken is the fact that education remains a fundamental and universal human right that can change the course of a life. To the millions still living in conditions of poverty, exclusion displacement and violence it opens a door to a better future.

Explore all the work and expertise of UNESCO in education

Related items.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception