Random Assignment in Psychology: Definition & Examples

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

In psychology, random assignment refers to the practice of allocating participants to different experimental groups in a study in a completely unbiased way, ensuring each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any group.

In experimental research, random assignment, or random placement, organizes participants from your sample into different groups using randomization.

Random assignment uses chance procedures to ensure that each participant has an equal opportunity of being assigned to either a control or experimental group.

The control group does not receive the treatment in question, whereas the experimental group does receive the treatment.

When using random assignment, neither the researcher nor the participant can choose the group to which the participant is assigned. This ensures that any differences between and within the groups are not systematic at the onset of the study.

In a study to test the success of a weight-loss program, investigators randomly assigned a pool of participants to one of two groups.

Group A participants participated in the weight-loss program for 10 weeks and took a class where they learned about the benefits of healthy eating and exercise.

Group B participants read a 200-page book that explains the benefits of weight loss. The investigator randomly assigned participants to one of the two groups.

The researchers found that those who participated in the program and took the class were more likely to lose weight than those in the other group that received only the book.

Importance

Random assignment ensures that each group in the experiment is identical before applying the independent variable.

In experiments , researchers will manipulate an independent variable to assess its effect on a dependent variable, while controlling for other variables. Random assignment increases the likelihood that the treatment groups are the same at the onset of a study.

Thus, any changes that result from the independent variable can be assumed to be a result of the treatment of interest. This is particularly important for eliminating sources of bias and strengthening the internal validity of an experiment.

Random assignment is the best method for inferring a causal relationship between a treatment and an outcome.

Random Selection vs. Random Assignment

Random selection (also called probability sampling or random sampling) is a way of randomly selecting members of a population to be included in your study.

On the other hand, random assignment is a way of sorting the sample participants into control and treatment groups.

Random selection ensures that everyone in the population has an equal chance of being selected for the study. Once the pool of participants has been chosen, experimenters use random assignment to assign participants into groups.

Random assignment is only used in between-subjects experimental designs, while random selection can be used in a variety of study designs.

Random Assignment vs Random Sampling

Random sampling refers to selecting participants from a population so that each individual has an equal chance of being chosen. This method enhances the representativeness of the sample.

Random assignment, on the other hand, is used in experimental designs once participants are selected. It involves allocating these participants to different experimental groups or conditions randomly.

This helps ensure that any differences in results across groups are due to manipulating the independent variable, not preexisting differences among participants.

When to Use Random Assignment

Random assignment is used in experiments with a between-groups or independent measures design.

In these research designs, researchers will manipulate an independent variable to assess its effect on a dependent variable, while controlling for other variables.

There is usually a control group and one or more experimental groups. Random assignment helps ensure that the groups are comparable at the onset of the study.

How to Use Random Assignment

There are a variety of ways to assign participants into study groups randomly. Here are a handful of popular methods:

- Random Number Generator : Give each member of the sample a unique number; use a computer program to randomly generate a number from the list for each group.

- Lottery : Give each member of the sample a unique number. Place all numbers in a hat or bucket and draw numbers at random for each group.

- Flipping a Coin : Flip a coin for each participant to decide if they will be in the control group or experimental group (this method can only be used when you have just two groups)

- Roll a Die : For each number on the list, roll a dice to decide which of the groups they will be in. For example, assume that rolling 1, 2, or 3 places them in a control group and rolling 3, 4, 5 lands them in an experimental group.

When is Random Assignment not used?

- When it is not ethically permissible: Randomization is only ethical if the researcher has no evidence that one treatment is superior to the other or that one treatment might have harmful side effects.

- When answering non-causal questions : If the researcher is just interested in predicting the probability of an event, the causal relationship between the variables is not important and observational designs would be more suitable than random assignment.

- When studying the effect of variables that cannot be manipulated: Some risk factors cannot be manipulated and so it would not make any sense to study them in a randomized trial. For example, we cannot randomly assign participants into categories based on age, gender, or genetic factors.

Drawbacks of Random Assignment

While randomization assures an unbiased assignment of participants to groups, it does not guarantee the equality of these groups. There could still be extraneous variables that differ between groups or group differences that arise from chance. Additionally, there is still an element of luck with random assignments.

Thus, researchers can not produce perfectly equal groups for each specific study. Differences between the treatment group and control group might still exist, and the results of a randomized trial may sometimes be wrong, but this is absolutely okay.

Scientific evidence is a long and continuous process, and the groups will tend to be equal in the long run when data is aggregated in a meta-analysis.

Additionally, external validity (i.e., the extent to which the researcher can use the results of the study to generalize to the larger population) is compromised with random assignment.

Random assignment is challenging to implement outside of controlled laboratory conditions and might not represent what would happen in the real world at the population level.

Random assignment can also be more costly than simple observational studies, where an investigator is just observing events without intervening with the population.

Randomization also can be time-consuming and challenging, especially when participants refuse to receive the assigned treatment or do not adhere to recommendations.

What is the difference between random sampling and random assignment?

Random sampling refers to randomly selecting a sample of participants from a population. Random assignment refers to randomly assigning participants to treatment groups from the selected sample.

Does random assignment increase internal validity?

Yes, random assignment ensures that there are no systematic differences between the participants in each group, enhancing the study’s internal validity .

Does random assignment reduce sampling error?

Yes, with random assignment, participants have an equal chance of being assigned to either a control group or an experimental group, resulting in a sample that is, in theory, representative of the population.

Random assignment does not completely eliminate sampling error because a sample only approximates the population from which it is drawn. However, random sampling is a way to minimize sampling errors.

When is random assignment not possible?

Random assignment is not possible when the experimenters cannot control the treatment or independent variable.

For example, if you want to compare how men and women perform on a test, you cannot randomly assign subjects to these groups.

Participants are not randomly assigned to different groups in this study, but instead assigned based on their characteristics.

Does random assignment eliminate confounding variables?

Yes, random assignment eliminates the influence of any confounding variables on the treatment because it distributes them at random among the study groups. Randomization invalidates any relationship between a confounding variable and the treatment.

Why is random assignment of participants to treatment conditions in an experiment used?

Random assignment is used to ensure that all groups are comparable at the start of a study. This allows researchers to conclude that the outcomes of the study can be attributed to the intervention at hand and to rule out alternative explanations for study results.

Further Reading

- Bogomolnaia, A., & Moulin, H. (2001). A new solution to the random assignment problem . Journal of Economic theory , 100 (2), 295-328.

- Krause, M. S., & Howard, K. I. (2003). What random assignment does and does not do . Journal of Clinical Psychology , 59 (7), 751-766.

Related Articles

Research Methodology

Qualitative Data Coding

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

Chapter 6: Experimental Research

6.2 experimental design, learning objectives.

- Explain the difference between between-subjects and within-subjects experiments, list some of the pros and cons of each approach, and decide which approach to use to answer a particular research question.

- Define random assignment, distinguish it from random sampling, explain its purpose in experimental research, and use some simple strategies to implement it.

- Define what a control condition is, explain its purpose in research on treatment effectiveness, and describe some alternative types of control conditions.

- Define several types of carryover effect, give examples of each, and explain how counterbalancing helps to deal with them.

In this section, we look at some different ways to design an experiment. The primary distinction we will make is between approaches in which each participant experiences one level of the independent variable and approaches in which each participant experiences all levels of the independent variable. The former are called between-subjects experiments and the latter are called within-subjects experiments.

Between-Subjects Experiments

In a between-subjects experiment , each participant is tested in only one condition. For example, a researcher with a sample of 100 college students might assign half of them to write about a traumatic event and the other half write about a neutral event. Or a researcher with a sample of 60 people with severe agoraphobia (fear of open spaces) might assign 20 of them to receive each of three different treatments for that disorder. It is essential in a between-subjects experiment that the researcher assign participants to conditions so that the different groups are, on average, highly similar to each other. Those in a trauma condition and a neutral condition, for example, should include a similar proportion of men and women, and they should have similar average intelligence quotients (IQs), similar average levels of motivation, similar average numbers of health problems, and so on. This is a matter of controlling these extraneous participant variables across conditions so that they do not become confounding variables.

Random Assignment

The primary way that researchers accomplish this kind of control of extraneous variables across conditions is called random assignment , which means using a random process to decide which participants are tested in which conditions. Do not confuse random assignment with random sampling. Random sampling is a method for selecting a sample from a population, and it is rarely used in psychological research. Random assignment is a method for assigning participants in a sample to the different conditions, and it is an important element of all experimental research in psychology and other fields too.

In its strictest sense, random assignment should meet two criteria. One is that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to each condition (e.g., a 50% chance of being assigned to each of two conditions). The second is that each participant is assigned to a condition independently of other participants. Thus one way to assign participants to two conditions would be to flip a coin for each one. If the coin lands heads, the participant is assigned to Condition A, and if it lands tails, the participant is assigned to Condition B. For three conditions, one could use a computer to generate a random integer from 1 to 3 for each participant. If the integer is 1, the participant is assigned to Condition A; if it is 2, the participant is assigned to Condition B; and if it is 3, the participant is assigned to Condition C. In practice, a full sequence of conditions—one for each participant expected to be in the experiment—is usually created ahead of time, and each new participant is assigned to the next condition in the sequence as he or she is tested. When the procedure is computerized, the computer program often handles the random assignment.

One problem with coin flipping and other strict procedures for random assignment is that they are likely to result in unequal sample sizes in the different conditions. Unequal sample sizes are generally not a serious problem, and you should never throw away data you have already collected to achieve equal sample sizes. However, for a fixed number of participants, it is statistically most efficient to divide them into equal-sized groups. It is standard practice, therefore, to use a kind of modified random assignment that keeps the number of participants in each group as similar as possible. One approach is block randomization . In block randomization, all the conditions occur once in the sequence before any of them is repeated. Then they all occur again before any of them is repeated again. Within each of these “blocks,” the conditions occur in a random order. Again, the sequence of conditions is usually generated before any participants are tested, and each new participant is assigned to the next condition in the sequence. Table 6.2 “Block Randomization Sequence for Assigning Nine Participants to Three Conditions” shows such a sequence for assigning nine participants to three conditions. The Research Randomizer website ( http://www.randomizer.org ) will generate block randomization sequences for any number of participants and conditions. Again, when the procedure is computerized, the computer program often handles the block randomization.

Table 6.2 Block Randomization Sequence for Assigning Nine Participants to Three Conditions

Random assignment is not guaranteed to control all extraneous variables across conditions. It is always possible that just by chance, the participants in one condition might turn out to be substantially older, less tired, more motivated, or less depressed on average than the participants in another condition. However, there are some reasons that this is not a major concern. One is that random assignment works better than one might expect, especially for large samples. Another is that the inferential statistics that researchers use to decide whether a difference between groups reflects a difference in the population takes the “fallibility” of random assignment into account. Yet another reason is that even if random assignment does result in a confounding variable and therefore produces misleading results, this is likely to be detected when the experiment is replicated. The upshot is that random assignment to conditions—although not infallible in terms of controlling extraneous variables—is always considered a strength of a research design.

Treatment and Control Conditions

Between-subjects experiments are often used to determine whether a treatment works. In psychological research, a treatment is any intervention meant to change people’s behavior for the better. This includes psychotherapies and medical treatments for psychological disorders but also interventions designed to improve learning, promote conservation, reduce prejudice, and so on. To determine whether a treatment works, participants are randomly assigned to either a treatment condition , in which they receive the treatment, or a control condition , in which they do not receive the treatment. If participants in the treatment condition end up better off than participants in the control condition—for example, they are less depressed, learn faster, conserve more, express less prejudice—then the researcher can conclude that the treatment works. In research on the effectiveness of psychotherapies and medical treatments, this type of experiment is often called a randomized clinical trial .

There are different types of control conditions. In a no-treatment control condition , participants receive no treatment whatsoever. One problem with this approach, however, is the existence of placebo effects. A placebo is a simulated treatment that lacks any active ingredient or element that should make it effective, and a placebo effect is a positive effect of such a treatment. Many folk remedies that seem to work—such as eating chicken soup for a cold or placing soap under the bedsheets to stop nighttime leg cramps—are probably nothing more than placebos. Although placebo effects are not well understood, they are probably driven primarily by people’s expectations that they will improve. Having the expectation to improve can result in reduced stress, anxiety, and depression, which can alter perceptions and even improve immune system functioning (Price, Finniss, & Benedetti, 2008).

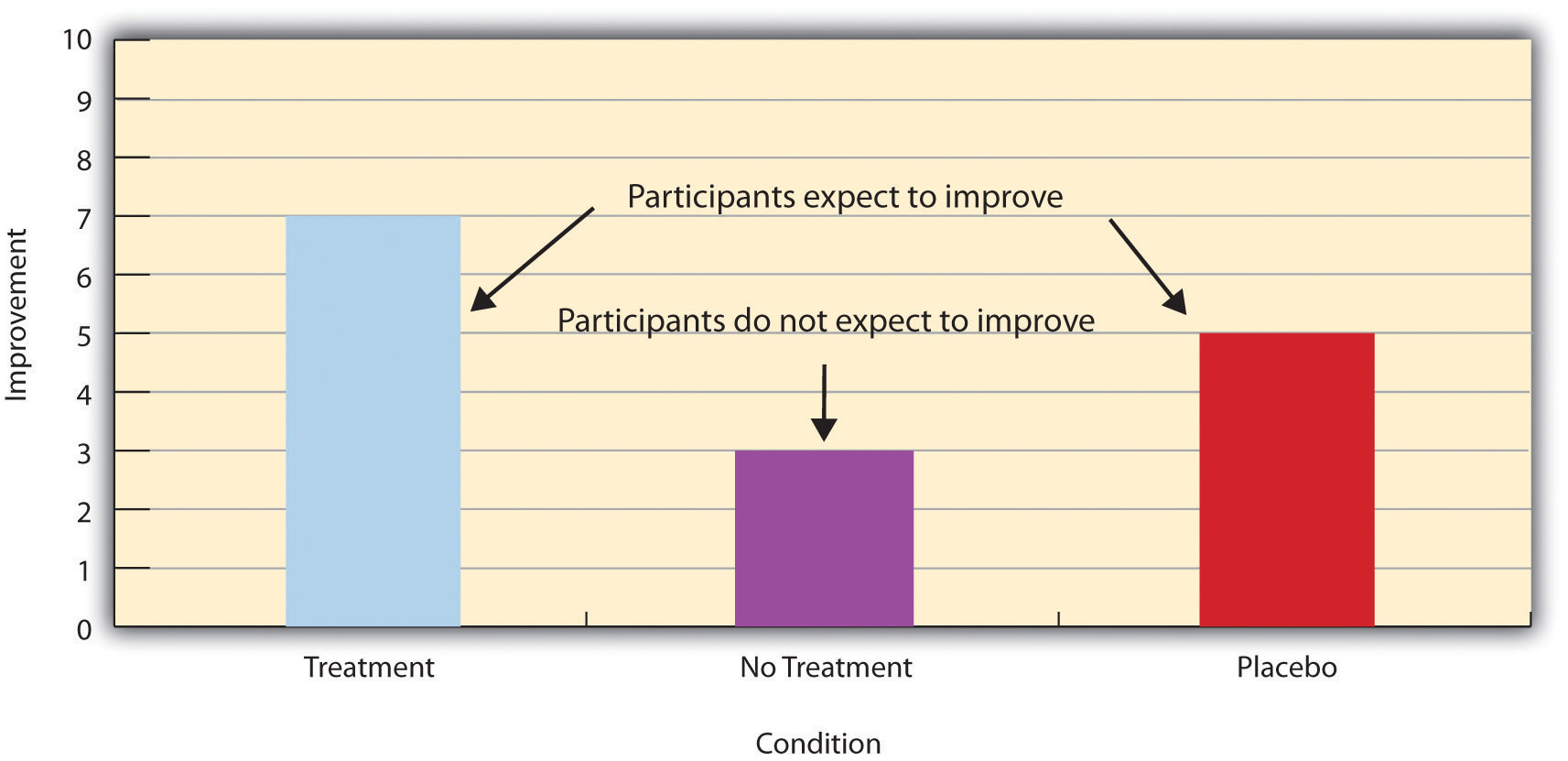

Placebo effects are interesting in their own right (see Note 6.28 “The Powerful Placebo” ), but they also pose a serious problem for researchers who want to determine whether a treatment works. Figure 6.2 “Hypothetical Results From a Study Including Treatment, No-Treatment, and Placebo Conditions” shows some hypothetical results in which participants in a treatment condition improved more on average than participants in a no-treatment control condition. If these conditions (the two leftmost bars in Figure 6.2 “Hypothetical Results From a Study Including Treatment, No-Treatment, and Placebo Conditions” ) were the only conditions in this experiment, however, one could not conclude that the treatment worked. It could be instead that participants in the treatment group improved more because they expected to improve, while those in the no-treatment control condition did not.

Figure 6.2 Hypothetical Results From a Study Including Treatment, No-Treatment, and Placebo Conditions

Fortunately, there are several solutions to this problem. One is to include a placebo control condition , in which participants receive a placebo that looks much like the treatment but lacks the active ingredient or element thought to be responsible for the treatment’s effectiveness. When participants in a treatment condition take a pill, for example, then those in a placebo control condition would take an identical-looking pill that lacks the active ingredient in the treatment (a “sugar pill”). In research on psychotherapy effectiveness, the placebo might involve going to a psychotherapist and talking in an unstructured way about one’s problems. The idea is that if participants in both the treatment and the placebo control groups expect to improve, then any improvement in the treatment group over and above that in the placebo control group must have been caused by the treatment and not by participants’ expectations. This is what is shown by a comparison of the two outer bars in Figure 6.2 “Hypothetical Results From a Study Including Treatment, No-Treatment, and Placebo Conditions” .

Of course, the principle of informed consent requires that participants be told that they will be assigned to either a treatment or a placebo control condition—even though they cannot be told which until the experiment ends. In many cases the participants who had been in the control condition are then offered an opportunity to have the real treatment. An alternative approach is to use a waitlist control condition , in which participants are told that they will receive the treatment but must wait until the participants in the treatment condition have already received it. This allows researchers to compare participants who have received the treatment with participants who are not currently receiving it but who still expect to improve (eventually). A final solution to the problem of placebo effects is to leave out the control condition completely and compare any new treatment with the best available alternative treatment. For example, a new treatment for simple phobia could be compared with standard exposure therapy. Because participants in both conditions receive a treatment, their expectations about improvement should be similar. This approach also makes sense because once there is an effective treatment, the interesting question about a new treatment is not simply “Does it work?” but “Does it work better than what is already available?”

The Powerful Placebo

Many people are not surprised that placebos can have a positive effect on disorders that seem fundamentally psychological, including depression, anxiety, and insomnia. However, placebos can also have a positive effect on disorders that most people think of as fundamentally physiological. These include asthma, ulcers, and warts (Shapiro & Shapiro, 1999). There is even evidence that placebo surgery—also called “sham surgery”—can be as effective as actual surgery.

Medical researcher J. Bruce Moseley and his colleagues conducted a study on the effectiveness of two arthroscopic surgery procedures for osteoarthritis of the knee (Moseley et al., 2002). The control participants in this study were prepped for surgery, received a tranquilizer, and even received three small incisions in their knees. But they did not receive the actual arthroscopic surgical procedure. The surprising result was that all participants improved in terms of both knee pain and function, and the sham surgery group improved just as much as the treatment groups. According to the researchers, “This study provides strong evidence that arthroscopic lavage with or without débridement [the surgical procedures used] is not better than and appears to be equivalent to a placebo procedure in improving knee pain and self-reported function” (p. 85).

Research has shown that patients with osteoarthritis of the knee who receive a “sham surgery” experience reductions in pain and improvement in knee function similar to those of patients who receive a real surgery.

Army Medicine – Surgery – CC BY 2.0.

Within-Subjects Experiments

In a within-subjects experiment , each participant is tested under all conditions. Consider an experiment on the effect of a defendant’s physical attractiveness on judgments of his guilt. Again, in a between-subjects experiment, one group of participants would be shown an attractive defendant and asked to judge his guilt, and another group of participants would be shown an unattractive defendant and asked to judge his guilt. In a within-subjects experiment, however, the same group of participants would judge the guilt of both an attractive and an unattractive defendant.

The primary advantage of this approach is that it provides maximum control of extraneous participant variables. Participants in all conditions have the same mean IQ, same socioeconomic status, same number of siblings, and so on—because they are the very same people. Within-subjects experiments also make it possible to use statistical procedures that remove the effect of these extraneous participant variables on the dependent variable and therefore make the data less “noisy” and the effect of the independent variable easier to detect. We will look more closely at this idea later in the book.

Carryover Effects and Counterbalancing

The primary disadvantage of within-subjects designs is that they can result in carryover effects. A carryover effect is an effect of being tested in one condition on participants’ behavior in later conditions. One type of carryover effect is a practice effect , where participants perform a task better in later conditions because they have had a chance to practice it. Another type is a fatigue effect , where participants perform a task worse in later conditions because they become tired or bored. Being tested in one condition can also change how participants perceive stimuli or interpret their task in later conditions. This is called a context effect . For example, an average-looking defendant might be judged more harshly when participants have just judged an attractive defendant than when they have just judged an unattractive defendant. Within-subjects experiments also make it easier for participants to guess the hypothesis. For example, a participant who is asked to judge the guilt of an attractive defendant and then is asked to judge the guilt of an unattractive defendant is likely to guess that the hypothesis is that defendant attractiveness affects judgments of guilt. This could lead the participant to judge the unattractive defendant more harshly because he thinks this is what he is expected to do. Or it could make participants judge the two defendants similarly in an effort to be “fair.”

Carryover effects can be interesting in their own right. (Does the attractiveness of one person depend on the attractiveness of other people that we have seen recently?) But when they are not the focus of the research, carryover effects can be problematic. Imagine, for example, that participants judge the guilt of an attractive defendant and then judge the guilt of an unattractive defendant. If they judge the unattractive defendant more harshly, this might be because of his unattractiveness. But it could be instead that they judge him more harshly because they are becoming bored or tired. In other words, the order of the conditions is a confounding variable. The attractive condition is always the first condition and the unattractive condition the second. Thus any difference between the conditions in terms of the dependent variable could be caused by the order of the conditions and not the independent variable itself.

There is a solution to the problem of order effects, however, that can be used in many situations. It is counterbalancing , which means testing different participants in different orders. For example, some participants would be tested in the attractive defendant condition followed by the unattractive defendant condition, and others would be tested in the unattractive condition followed by the attractive condition. With three conditions, there would be six different orders (ABC, ACB, BAC, BCA, CAB, and CBA), so some participants would be tested in each of the six orders. With counterbalancing, participants are assigned to orders randomly, using the techniques we have already discussed. Thus random assignment plays an important role in within-subjects designs just as in between-subjects designs. Here, instead of randomly assigning to conditions, they are randomly assigned to different orders of conditions. In fact, it can safely be said that if a study does not involve random assignment in one form or another, it is not an experiment.

There are two ways to think about what counterbalancing accomplishes. One is that it controls the order of conditions so that it is no longer a confounding variable. Instead of the attractive condition always being first and the unattractive condition always being second, the attractive condition comes first for some participants and second for others. Likewise, the unattractive condition comes first for some participants and second for others. Thus any overall difference in the dependent variable between the two conditions cannot have been caused by the order of conditions. A second way to think about what counterbalancing accomplishes is that if there are carryover effects, it makes it possible to detect them. One can analyze the data separately for each order to see whether it had an effect.

When 9 Is “Larger” Than 221

Researcher Michael Birnbaum has argued that the lack of context provided by between-subjects designs is often a bigger problem than the context effects created by within-subjects designs. To demonstrate this, he asked one group of participants to rate how large the number 9 was on a 1-to-10 rating scale and another group to rate how large the number 221 was on the same 1-to-10 rating scale (Birnbaum, 1999). Participants in this between-subjects design gave the number 9 a mean rating of 5.13 and the number 221 a mean rating of 3.10. In other words, they rated 9 as larger than 221! According to Birnbaum, this is because participants spontaneously compared 9 with other one-digit numbers (in which case it is relatively large) and compared 221 with other three-digit numbers (in which case it is relatively small).

Simultaneous Within-Subjects Designs

So far, we have discussed an approach to within-subjects designs in which participants are tested in one condition at a time. There is another approach, however, that is often used when participants make multiple responses in each condition. Imagine, for example, that participants judge the guilt of 10 attractive defendants and 10 unattractive defendants. Instead of having people make judgments about all 10 defendants of one type followed by all 10 defendants of the other type, the researcher could present all 20 defendants in a sequence that mixed the two types. The researcher could then compute each participant’s mean rating for each type of defendant. Or imagine an experiment designed to see whether people with social anxiety disorder remember negative adjectives (e.g., “stupid,” “incompetent”) better than positive ones (e.g., “happy,” “productive”). The researcher could have participants study a single list that includes both kinds of words and then have them try to recall as many words as possible. The researcher could then count the number of each type of word that was recalled. There are many ways to determine the order in which the stimuli are presented, but one common way is to generate a different random order for each participant.

Between-Subjects or Within-Subjects?

Almost every experiment can be conducted using either a between-subjects design or a within-subjects design. This means that researchers must choose between the two approaches based on their relative merits for the particular situation.

Between-subjects experiments have the advantage of being conceptually simpler and requiring less testing time per participant. They also avoid carryover effects without the need for counterbalancing. Within-subjects experiments have the advantage of controlling extraneous participant variables, which generally reduces noise in the data and makes it easier to detect a relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

A good rule of thumb, then, is that if it is possible to conduct a within-subjects experiment (with proper counterbalancing) in the time that is available per participant—and you have no serious concerns about carryover effects—this is probably the best option. If a within-subjects design would be difficult or impossible to carry out, then you should consider a between-subjects design instead. For example, if you were testing participants in a doctor’s waiting room or shoppers in line at a grocery store, you might not have enough time to test each participant in all conditions and therefore would opt for a between-subjects design. Or imagine you were trying to reduce people’s level of prejudice by having them interact with someone of another race. A within-subjects design with counterbalancing would require testing some participants in the treatment condition first and then in a control condition. But if the treatment works and reduces people’s level of prejudice, then they would no longer be suitable for testing in the control condition. This is true for many designs that involve a treatment meant to produce long-term change in participants’ behavior (e.g., studies testing the effectiveness of psychotherapy). Clearly, a between-subjects design would be necessary here.

Remember also that using one type of design does not preclude using the other type in a different study. There is no reason that a researcher could not use both a between-subjects design and a within-subjects design to answer the same research question. In fact, professional researchers often do exactly this.

Key Takeaways

- Experiments can be conducted using either between-subjects or within-subjects designs. Deciding which to use in a particular situation requires careful consideration of the pros and cons of each approach.

- Random assignment to conditions in between-subjects experiments or to orders of conditions in within-subjects experiments is a fundamental element of experimental research. Its purpose is to control extraneous variables so that they do not become confounding variables.

- Experimental research on the effectiveness of a treatment requires both a treatment condition and a control condition, which can be a no-treatment control condition, a placebo control condition, or a waitlist control condition. Experimental treatments can also be compared with the best available alternative.

Discussion: For each of the following topics, list the pros and cons of a between-subjects and within-subjects design and decide which would be better.

- You want to test the relative effectiveness of two training programs for running a marathon.

- Using photographs of people as stimuli, you want to see if smiling people are perceived as more intelligent than people who are not smiling.

- In a field experiment, you want to see if the way a panhandler is dressed (neatly vs. sloppily) affects whether or not passersby give him any money.

- You want to see if concrete nouns (e.g., dog ) are recalled better than abstract nouns (e.g., truth ).

- Discussion: Imagine that an experiment shows that participants who receive psychodynamic therapy for a dog phobia improve more than participants in a no-treatment control group. Explain a fundamental problem with this research design and at least two ways that it might be corrected.

Birnbaum, M. H. (1999). How to show that 9 > 221: Collect judgments in a between-subjects design. Psychological Methods, 4 , 243–249.

Moseley, J. B., O’Malley, K., Petersen, N. J., Menke, T. J., Brody, B. A., Kuykendall, D. H., … Wray, N. P. (2002). A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. The New England Journal of Medicine, 347 , 81–88.

Price, D. D., Finniss, D. G., & Benedetti, F. (2008). A comprehensive review of the placebo effect: Recent advances and current thought. Annual Review of Psychology, 59 , 565–590.

Shapiro, A. K., & Shapiro, E. (1999). The powerful placebo: From ancient priest to modern physician . Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Research Methods in Psychology. Provided by : University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Located at : http://open.lib.umn.edu/psychologyresearchmethods . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

Privacy Policy

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.1: Research Designs

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 32913

- Yang Lydia Yang

- Kansas State University

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Research Designs

In the early 1970’s, a man named Uri Geller tricked the world: he convinced hundreds of thousands of people that he could bend spoons and slow watches using only the power of his mind. In fact, if you were in the audience, you would have likely believed he had psychic powers. Everything looked authentic—this man had to have paranormal abilities! So, why have you probably never heard of him before? Because when Uri was asked to perform his miracles in line with scientific experimentation, he was no longer able to do them. That is, even though it seemed like he was doing the impossible, when he was tested by science, he proved to be nothing more than a clever magician.

When we look at dinosaur bones to make educated guesses about extinct life, or systematically chart the heavens to learn about the relationships between stars and planets, or study magicians to figure out how they perform their tricks, we are forming observations—the foundation of science. Although we are all familiar with the saying “seeing is believing,” conducting science is more than just what your eyes perceive. Science is the result of systematic and intentional study of the natural world. And soical science is no different. In the movie Jerry Maguire , Cuba Gooding, Jr. became famous for using the phrase, “Show me the money!” In education, as in all sciences, we might say, “Show me the data!”

One of the important steps in scientific inquiry is to test our research questions, otherwise known as hypotheses. However, there are many ways to test hypotheses in educational research. Which method you choose will depend on the type of questions you are asking, as well as what resources are available to you. All methods have limitations, which is why the best research uses a variety of methods.

Experimental Research

If somebody gave you $20 that absolutely had to be spent today, how would you choose to spend it? Would you spend it on an item you’ve been eyeing for weeks, or would you donate the money to charity? Which option do you think would bring you the most happiness? If you’re like most people, you’d choose to spend the money on yourself (duh, right?). Our intuition is that we’d be happier if we spent the money on ourselves.

Knowing that our intuition can sometimes be wrong, Professor Elizabeth Dunn (2008) at the University of British Columbia set out to conduct an experiment on spending and happiness. She gave each of the participants in her experiment $20 and then told them they had to spend the money by the end of the day. Some of the participants were told they must spend the money on themselves, and some were told they must spend the money on others (either charity or a gift for someone). At the end of the day she measured participants’ levels of happiness using a self-report questionnaire.

In an experiment, researchers manipulate, or cause changes, in the independent variable , and observe or measure any impact of those changes in the dependent variable . The independent variable is the one under the researcher’s control, or the variable that is intentionally altered between groups. In the case of Dunn’s experiment, the independent variable was whether participants spent the money on themselves or on others. The dependent variable is the variable that is not manipulated at all, or the one where the effect happens. One way to help remember this is that the dependent variable “depends” on what happens to the independent variable. In our example, the participants’ happiness (the dependent variable in this experiment) depends on how the participants spend their money (the independent variable). Thus, any observed changes or group differences in happiness can be attributed to whom the money was spent on. What Dunn and her colleagues found was that, after all the spending had been done, the people who had spent the money on others were happier than those who had spent the money on themselves. In other words, spending on others causes us to be happier than spending on ourselves. Do you find this surprising?

But wait! Doesn’t happiness depend on a lot of different factors—for instance, a person’s upbringing or life circumstances? What if some people had happy childhoods and that’s why they’re happier? Or what if some people dropped their toast that morning and it fell jam-side down and ruined their whole day? It is correct to recognize that these factors and many more can easily affect a person’s level of happiness. So how can we accurately conclude that spending money on others causes happiness, as in the case of Dunn’s experiment?

The most important thing about experiments is random assignment . Participants don’t get to pick which condition they are in (e.g., participants didn’t choose whether they were supposed to spend the money on themselves versus others). The experimenter assigns them to a particular condition based on the flip of a coin or the roll of a die or any other random method. Why do researchers do this? With Dunn’s study, there is the obvious reason: you can imagine which condition most people would choose to be in, if given the choice. But another equally important reason is that random assignment makes it so the groups, on average, are similar on all characteristics except what the experimenter manipulates.

By randomly assigning people to conditions (self-spending versus other-spending), some people with happy childhoods should end up in each condition. Likewise, some people who had dropped their toast that morning (or experienced some other disappointment) should end up in each condition. As a result, the distribution of all these factors will generally be consistent across the two groups, and this means that on average the two groups will be relatively equivalent on all these factors. Random assignment is critical to experimentation because if the only difference between the two groups is the independent variable, we can infer that the independent variable is the cause of any observable difference (e.g., in the amount of happiness they feel at the end of the day).

Here’s another example of the importance of random assignment: Let’s say your class is going to form two basketball teams, and you get to be the captain of one team. The class is to be divided evenly between the two teams. If you get to pick the players for your team first, whom will you pick? You’ll probably pick the tallest members of the class or the most athletic. You probably won’t pick the short, uncoordinated people, unless there are no other options. As a result, your team will be taller and more athletic than the other team. But what if we want the teams to be fair? How can we do this when we have people of varying height and ability? All we have to do is randomly assign players to the two teams. Most likely, some tall and some short people will end up on your team, and some tall and some short people will end up on the other team. The average height of the teams will be approximately the same. That is the power of random assignment!

Other considerations

In addition to using random assignment, you should avoid introducing confounding variables into your experiments. Confounding variables are things that could undermine your ability to draw causal inferences. For example, if you wanted to test if a new happy pill will make people happier, you could randomly assign participants to take the happy pill or not (the independent variable) and compare these two groups on their self-reported happiness (the dependent variable). However, if some participants know they are getting the happy pill, they might develop expectations that influence their self-reported happiness. This is sometimes known as a placebo effect . Sometimes a person just knowing that he or she is receiving special treatment or something new is enough to actually cause changes in behavior or perception: In other words, even if the participants in the happy pill condition were to report being happier, we wouldn’t know if the pill was actually making them happier or if it was the placebo effect—an example of a confound. Even experimenter expectations can influence the outcome of a study. For example, if the experimenter knows who took the happy pill and who did not, and the dependent variable is the experimenter’s observations of people’s happiness, then the experimenter might perceive improvements in the happy pill group that are not really there.

One way to prevent these confounds from affecting the results of a study is to use a double-blind procedure. In a double-blind procedure, neither the participant nor the experimenter knows which condition the participant is in. For example, when participants are given the happy pill or the fake pill, they don’t know which one they are receiving. This way the participants shouldn’t experience the placebo effect, and will be unable to behave as the researcher expects (participant demand). Likewise, the researcher doesn’t know which pill each participant is taking (at least in the beginning—later, the researcher will get the results for data-analysis purposes), which means the researcher’s expectations can’t influence his or her observations. Therefore, because both parties are “blind” to the condition, neither will be able to behave in a way that introduces a confound. At the end of the day, the only difference between groups will be which pills the participants received, allowing the researcher to determine if the happy pill actually caused people to be happier.

Quasi-Experimental Designs

What if you want to study the effects of marriage on a variable? For example, does marriage make people happier? Can you randomly assign some people to get married and others to remain single? Of course not. So how can you study these important variables? You can use a quasi-experimental design . A quasi-experimental design is similar to experimental research, except that random assignment to conditions is not used. Instead, we rely on existing group memberships (e.g., married vs. single). We treat these as the independent variables, even though we don’t assign people to the conditions and don’t manipulate the variables. As a result, with quasi-experimental designs causal inference is more difficult. For example, married people might differ on a variety of characteristics from unmarried people. If we find that married participants are happier than single participants, it will be hard to say that marriage causes happiness, because the people who got married might have already been happier than the people who have remained single.

Because experimental and quasi-experimental designs can seem pretty similar, let’s take another example to distinguish them. Imagine you want to know who is a better professor: Dr. Smith or Dr. Khan. To judge their ability, you’re going to look at their students’ final grades. Here, the independent variable is the professor (Dr. Smith vs. Dr. Khan) and the dependent variable is the students’ grades. In an experimental design, you would randomly assign students to one of the two professors and then compare the students’ final grades. However, in real life, researchers can’t randomly force students to take one professor over the other; instead, the researchers would just have to use the preexisting classes and study them as-is (quasi-experimental design). Again, the key difference is random assignment to the conditions of the independent variable. Although the quasi-experimental design (where the students choose which professor they want) may seem random, it’s most likely not. For example, maybe students heard Dr. Smith sets low expectations, so slackers prefer this class, whereas Dr. Khan sets higher expectations, so smarter students prefer that one. This now introduces a confounding variable (student intelligence) that will almost certainly have an effect on students’ final grades, regardless of how skilled the professor is. So, even though a quasi-experimental design is similar to an experimental design (i.e., it has a manipulated independent variable), because there’s no random assignment, you can’t reasonably draw the same conclusions that you would with an experimental design.

Non-Experimental Studies

When scientists passively observe and measure phenomena it is called non-experimental research. Here, we do not intervene and change behavior, as we do in experiments. In non-experimental research, we identify patterns of relationships, but we usually cannot infer what causes what. Importantly, with non-experimental research, you can examine only two variables at a time, no more and no less.

So, what if you wanted to test whether spending on others is related to happiness, but you don’t have $20 to give to each participant? You could use a non-experimental research — which is exactly what Professor Dunn did, too. She asked people how much of their income they spent on others or donated to charity, and later she asked them how happy they were. Do you think these two variables were related? Yes, they were! The more money people reported spending on others, the happier they were. This indicates a positive correlation!

If generosity and happiness are positively correlated, should we conclude that being generous causes happiness? Similarly, if height and pathogen prevalence are negatively correlated, should we conclude that disease causes shortness? From a correlation alone, we can’t be certain. For example, in the first case it may be that happiness causes generosity, or that generosity causes happiness. Or, a third variable might cause both happiness and generosity, creating the illusion of a direct link between the two. For example, wealth could be the third variable that causes both greater happiness and greater generosity. This is why correlation does not mean causation —an often repeated phrase among psychologists.

One particular type of non-experimental research is the longitudinal study . Longitudinal studies are typically observational in nature. They track the same people over time. Some longitudinal studies last a few weeks, some a few months, some a year or more. Some studies that have contributed a lot to a given topic by following the same people over decades. For example, one study followed more than 20,000 Germans for two decades. From these longitudinal data, psychologist Rich Lucas (2003) was able to determine that people who end up getting married indeed start off a bit happier than their peers who never marry. Longitudinal studies like this provide valuable evidence for testing many theories in social sciences, but they can be quite costly to conduct, especially if they follow many people for many years.

Tradeoffs in Research

Even though there are serious limitations to non-experimental and quasi-experimental research, they are not poor cousins to experiments designs. In addition to selecting a method that is appropriate to the question, many practical concerns may influence the decision to use one method over another. One of these factors is simply resource availability—how much time and money do you have to invest in the research? Often, we survey people even though it would be more precise—but much more difficult—to track them longitudinally. Especially in the case of exploratory research, it may make sense to opt for a cheaper and faster method first. Then, if results from the initial study are promising, the researcher can follow up with a more intensive method.

Beyond these practical concerns, another consideration in selecting a research design is the ethics of the study. For example, in cases of brain injury or other neurological abnormalities, it would be unethical for researchers to inflict these impairments on healthy participants. Nonetheless, studying people with these injuries can provide great insight into human mind (e.g., if we learn that damage to a particular region of the brain interferes with emotions, we may be able to develop treatments for emotional irregularities). In addition to brain injuries, there are numerous other areas of research that could be useful in understanding the human mind but which pose challenges to a true experimental design — such as the experiences of war, long-term isolation, abusive parenting, or prolonged drug use. However, none of these are conditions we could ethically experimentally manipulate and randomly assign people to. Therefore, ethical considerations are another crucial factor in determining an appropriate research design.

Research Methods: Why You Need Them

Just look at any major news outlet and you’ll find research routinely being reported. Sometimes the journalist understands the research methodology, sometimes not (e.g., correlational evidence is often incorrectly represented as causal evidence). Often, the media are quick to draw a conclusion for you. After reading this module, you should recognize that the strength of a scientific finding lies in the strength of its methodology. Therefore, in order to be a savvy producer and/or consumer of research, you need to understand the pros and cons of different methods and the distinctions among them.

Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., & Norton, M. I. (2008). Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science, 319(5870), 1687–1688. doi:10.1126/science.1150952

Lucas, R. E., Clark, A. E., Georgellis, Y., & Diener, E. (2003). Re-examining adaptation and the setpoint model of happiness: Reactions to changes in marital status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 527–539.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Definition of Random Assignment According to Psychology

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

Materio / Getty Images

Random assignment refers to the use of chance procedures in psychology experiments to ensure that each participant has the same opportunity to be assigned to any given group in a study to eliminate any potential bias in the experiment at the outset. Participants are randomly assigned to different groups, such as the treatment group versus the control group. In clinical research, randomized clinical trials are known as the gold standard for meaningful results.

Simple random assignment techniques might involve tactics such as flipping a coin, drawing names out of a hat, rolling dice, or assigning random numbers to a list of participants. It is important to note that random assignment differs from random selection .

While random selection refers to how participants are randomly chosen from a target population as representatives of that population, random assignment refers to how those chosen participants are then assigned to experimental groups.

Random Assignment In Research

To determine if changes in one variable will cause changes in another variable, psychologists must perform an experiment. Random assignment is a critical part of the experimental design that helps ensure the reliability of the study outcomes.

Researchers often begin by forming a testable hypothesis predicting that one variable of interest will have some predictable impact on another variable.

The variable that the experimenters will manipulate in the experiment is known as the independent variable , while the variable that they will then measure for different outcomes is known as the dependent variable. While there are different ways to look at relationships between variables, an experiment is the best way to get a clear idea if there is a cause-and-effect relationship between two or more variables.

Once researchers have formulated a hypothesis, conducted background research, and chosen an experimental design, it is time to find participants for their experiment. How exactly do researchers decide who will be part of an experiment? As mentioned previously, this is often accomplished through something known as random selection.

Random Selection

In order to generalize the results of an experiment to a larger group, it is important to choose a sample that is representative of the qualities found in that population. For example, if the total population is 60% female and 40% male, then the sample should reflect those same percentages.

Choosing a representative sample is often accomplished by randomly picking people from the population to be participants in a study. Random selection means that everyone in the group stands an equal chance of being chosen to minimize any bias. Once a pool of participants has been selected, it is time to assign them to groups.

By randomly assigning the participants into groups, the experimenters can be fairly sure that each group will have the same characteristics before the independent variable is applied.

Participants might be randomly assigned to the control group , which does not receive the treatment in question. The control group may receive a placebo or receive the standard treatment. Participants may also be randomly assigned to the experimental group , which receives the treatment of interest. In larger studies, there can be multiple treatment groups for comparison.

There are simple methods of random assignment, like rolling the die. However, there are more complex techniques that involve random number generators to remove any human error.

There can also be random assignment to groups with pre-established rules or parameters. For example, if you want to have an equal number of men and women in each of your study groups, you might separate your sample into two groups (by sex) before randomly assigning each of those groups into the treatment group and control group.

Random assignment is essential because it increases the likelihood that the groups are the same at the outset. With all characteristics being equal between groups, other than the application of the independent variable, any differences found between group outcomes can be more confidently attributed to the effect of the intervention.

Example of Random Assignment

Imagine that a researcher is interested in learning whether or not drinking caffeinated beverages prior to an exam will improve test performance. After randomly selecting a pool of participants, each person is randomly assigned to either the control group or the experimental group.

The participants in the control group consume a placebo drink prior to the exam that does not contain any caffeine. Those in the experimental group, on the other hand, consume a caffeinated beverage before taking the test.

Participants in both groups then take the test, and the researcher compares the results to determine if the caffeinated beverage had any impact on test performance.

A Word From Verywell

Random assignment plays an important role in the psychology research process. Not only does this process help eliminate possible sources of bias, but it also makes it easier to generalize the results of a tested sample of participants to a larger population.

Random assignment helps ensure that members of each group in the experiment are the same, which means that the groups are also likely more representative of what is present in the larger population of interest. Through the use of this technique, psychology researchers are able to study complex phenomena and contribute to our understanding of the human mind and behavior.

Lin Y, Zhu M, Su Z. The pursuit of balance: An overview of covariate-adaptive randomization techniques in clinical trials . Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45(Pt A):21-25. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2015.07.011

Sullivan L. Random assignment versus random selection . In: The SAGE Glossary of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2009. doi:10.4135/9781412972024.n2108

Alferes VR. Methods of Randomization in Experimental Design . SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2012. doi:10.4135/9781452270012

Nestor PG, Schutt RK. Research Methods in Psychology: Investigating Human Behavior. (2nd Ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2015.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

As previously mentioned, one of the characteristics of a true experiment is that researchers use a random process to decide which participants are tested under which conditions. Random assignation is a powerful research technique that addresses the assumption of pre-test equivalence – that the experimental and control group are equal in all respects before the administration of the independent variable (Palys & Atchison, 2014).

Random assignation is the primary way that researchers attempt to control extraneous variables across conditions. Random assignation is associated with experimental research methods. In its strictest sense, random assignment should meet two criteria. One is that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to each condition (e.g., a 50% chance of being assigned to each of two conditions). The second is that each participant is assigned to a condition independently of other participants. Thus, one way to assign participants to two conditions would be to flip a coin for each one. If the coin lands on the heads side, the participant is assigned to Condition A, and if it lands on the tails side, the participant is assigned to Condition B. For three conditions, one could use a computer to generate a random integer from 1 to 3 for each participant. If the integer is 1, the participant is assigned to Condition A; if it is 2, the participant is assigned to Condition B; and, if it is 3, the participant is assigned to Condition C. In practice, a full sequence of conditions—one for each participant expected to be in the experiment—is usually created ahead of time, and each new participant is assigned to the next condition in the sequence as he or she is tested.

However, one problem with coin flipping and other strict procedures for random assignment is that they are likely to result in unequal sample sizes in the different conditions. Unequal sample sizes are generally not a serious problem, and you should never throw away data you have already collected to achieve equal sample sizes. However, for a fixed number of participants, it is statistically most efficient to divide them into equal-sized groups. It is standard practice, therefore, to use a kind of modified random assignment that keeps the number of participants in each group as similar as possible.

One approach is block randomization. In block randomization, all the conditions occur once in the sequence before any of them is repeated. Then they all occur again before any of them is repeated again. Within each of these “blocks,” the conditions occur in a random order. Again, the sequence of conditions is usually generated before any participants are tested, and each new participant is assigned to the next condition in the sequence. When the procedure is computerized, the computer program often handles the random assignment, which is obviously much easier. You can also find programs online to help you randomize your random assignation. For example, the Research Randomizer website will generate block randomization sequences for any number of participants and conditions ( Research Randomizer ).

Random assignation is not guaranteed to control all extraneous variables across conditions. It is always possible that, just by chance, the participants in one condition might turn out to be substantially older, less tired, more motivated, or less depressed on average than the participants in another condition. However, there are some reasons that this may not be a major concern. One is that random assignment works better than one might expect, especially for large samples. Another is that the inferential statistics that researchers use to decide whether a difference between groups reflects a difference in the population take the “fallibility” of random assignment into account. Yet another reason is that even if random assignment does result in a confounding variable and therefore produces misleading results, this confound is likely to be detected when the experiment is replicated. The upshot is that random assignment to conditions—although not infallible in terms of controlling extraneous variables—is always considered a strength of a research design. Note: Do not confuse random assignation with random sampling. Random sampling is a method for selecting a sample from a population; we will talk about this in Chapter 7.

Research Methods, Data Collection and Ethics Copyright © 2020 by Valerie Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Protection of Random Assignment

- First Online: 14 October 2021

Cite this chapter

- Lynda H. Powell 4 ,

- Peter G. Kaufmann 5 &

- Kenneth E. Freedland 6

544 Accesses

Existence of an alternative explanation for the benefit of a treatment is a confounder. It is a nuisance “passenger” variable that rides along with treatment and undermines the ability to make causal inferences. This chapter focuses on why random assignment is so powerful and should be protected. It presents a history of attempts to answer the question of whether or not a treatment works, and the arrival at random assignment as the best way to make causal inferences about the benefits of a treatment. It defines confounding as an error of interpretation and the essential role of avoiding it by protecting the random assignment. It then goes on to illustrate ways to protect random assignment in the design, conduct, and analyses of a trial, with particular attention to the central role of identifying a patient-centered target population, recruiting it, retaining it, and insuring that all randomized participants are included in the evaluation of trial results.

“Daniel and his three companions were young Israelites who were taken to serve in the palace of the king of Babylon because they were of noble royal family, without physical defect, handsome, versed in wisdom, and competent. Daniel determined he would not defile himself with the King’s food or wine. He asked the overseer: ‘Please test us for 10 days and let us be given some vegetables to eat and water to drink. Then let our appearance be compared to the appearance of youths who are eating the King’s choice food.’ At the end of 10 days, their appearance seemed better and they were fatter than any of the youths who had been eating the King’s food. So the overseer let them continue to eat vegetables and drink water instead of what the king provided.” Bible, Old Testament, Book of Daniel 1:16

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bull JP (1959) The historical development of clinical therapeutic trials. J Chron Dis 10:218–248

PubMed Google Scholar

Armitage P (1982) The role of randomization in clinical trials. Stat Med 1:345–352

Van Helmont JB (1662) Oriatrike or Physik Refined. In Debus AG (1968) The chemical dream of the renaissance. Heffer, London

Google Scholar

Peirce CS, Jastrow J (1884) Fifth memoir: on small differences of sensation. Ntl Acad Sci 3:73–83

Yule G (1924) The function of statistical method in scientific investigation. Industrial Health Research Board Report 28. His Majesty’s Stationery Office, London

Eliot MM (1925) The control of rickets: preliminary discussion of the demonstration in New Haven. JAMA 85:656–663

Hill AB (1952) The clinical trial. New Engl J Med 247:113–119

Hill AB (1953) Observation and experiment. New Engl J Med 248:995–1001

Sinclair HM (1951) Nutritional surveys of population groups. New Engl J Med 245:39–47

Mill JS (1843) A system of logic ratiocinative and inductive. Being a connected view of the principles of evidence and the methods of scientific investigation. Book I. In Robson JM (ed). The collected works of John Stuart Mill (1974). University of Toronto Press, Toronto

Hill AB (1965) The environment and disease: association or causation. Proc Roy Soc Med 58:295–300

Wang D, Bakhai A (2006) Clinical trials: a practical guide to design, analysis, and reporting. Remedica, London

Domanski M, McKinlay S (2009) Successful randomized trials. A handbook for the 21st century. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

Friedman LM, Furberg CD, DeMets D, Reboussin DH, Granger CB (2015) Fundamentals of clinical trials, 5th edn. Springer, Cham

Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL (2008) Modern epidemiology, 3rd edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

Szklo M, Nieto FJ (2019) Epidemiology: beyond the basics, 4th edn. Jones & Bartlett Learning, Burlington

Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Mayrent SL (1987) Epidemiology in medicine. Little Brown, Boston

Susser M (1973) Causal thinking in the health sciences: Concepts and strategies of epidemiology. Oxford University Press, New York

Fisher RA (1951) The design of experiments, 6th edn. Hafner, New York

Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT (2002) Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

Byar DP, Simon RM, Friedewald WT, Schlesselman JJ, DeMets D, Ellenberg JH, Gail MH, Ware JH (1976) Randomized clinical trials--perspectives on some recent ideas. N Engl J Med 295:74–80

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gotzche PC, Devereaux PJ, Elbourne D, Egger M, Altman DG (2010) CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 340:c869. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c869

Mosteller F, Gilbert JP, McPeek B (1980) Reporting standards and research strategies for controlled trials. Control Clin Trials 1:37–58

Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG (1995) Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 273:408–412

CONSORT Group (2010) CONSORT checklist. www.consort-statement.org

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT Group (2010) CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 152:726–732

Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Altman DG, Tunis S, Haynes B, Oxman AD, Moher D, and for the CONSORT and Pragmatic Trials in Healthcare (Practihc) groups (2008) Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ 337:a2390. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a2390

Schulz KF (1995) Subverting randomization in controlled trials. JAMA 274:1456–1458

Kraemer HC (2015) A source of false findings in published research studies: adjusting for covariates. JAMA Psychiatry 72:961–962

Pocock SJ, Assmann SE, Enos LE, Kasten LE (2002) Subgroup analysis, covariate adjustment and baseline comparisons in clinical trial reporting: current practice and problems. Stat Med 21:2917–2930

Schulz KF, Grimes DA, Altman DG, Hayes RJ (1996) Blinding and exclusions after allocation in randomised controlled trials: survey of published parallel group trials in obstetrics and gynaecology. BMJ 312:742–744

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Detry MA, Lewis RJ (2014) The intention-to-treat principle: how to assess the true effect of choosing a medical treatment. JAMA 312:85–86

Freedman B (1987) Equipoise and the ethics of clinical research. N Eng J Med 317:141–145

Green SB, Byar DP (1984) Using observational data from registries to compare treatments: the fallacy of omnimetrics. Stat Med 3:361–373

Hollon SD, Wampold BE (2009) Are randomized controlled trials relevant to clinical practice? Can J Psychiatry 54:637–643

Cook TD, Campbell DT (1979) Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for field settings. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, Marcus AC (2003) Why don’t we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. Am J Public Health 93:1261–1267

Areán PA, Kraemer HC (2013) High-quality psychotherapy research: From conception to piloting to national trials. Oxford University Press, New York

Brownell KD, Wadden TA (1992) Etiology and treatment of obesity: understanding a serious, prevalent, and refractory disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 60:505–517

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC (1992) In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol 47:1102–1114

Hall SM, Tsoh JY, Prochaska JJ, Eisendrath S, Rossi JS, Redding CA, Rosen AB, Meisner M, Humfleet GL, Gorecki JA (2006) Treatment for cigarette smoking among depressed mental health outpatients: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Public Health 96:1808–1814

Prochaska JJ, Hall SE, Delucchi K, Hall SM (2014) Efficacy of initiating tobacco dependence treatment in inpatient psychiatry: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health 104:1557–1565

Prochaska JJ, Hall SE, Hall SM (2009) Stage-tailored tobacco cessation treatment in inpatient psychiatry. Psychiatr Serv 60:848. https://doi:10.1176/appi.ps.60.6.848

Prochaska JJ, Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, Delucchi K, Hall SM (2006) Comparing intervention outcomes in smokers treated for single versus multiple behavioral risks. Health Psychol 25:380–388

The Steering Committee of the Physicians Health Study Research Group (1988) Preliminary report: findings from the aspirin component of the ongoing Physicians’ Health Study. N Engl J Med 318:262–264

Coronary Drug Project Research Group (1980) Influence of adherence to treatment and response of cholesterol on mortality in the Coronary Drug Project. N Engl J Med 303:1038–1041

Adamson J, Cockayne S, Puffer S, Torgerson DJ (2006) Review of randomised trials using the post-randomised consent (Zelen’s) design. Contemp Clin Trials 27:305–319

Fabricatore AN, Wadden TA, Moore RH, Butryn ML, Gravallese EA, Erondu NE, Heymsfield SB, Nguyen AM (2009) Attrition from randomized controlled trials of pharmacological weight loss agents: a systematic review and analysis. Obes Rev 10:333–341

Lang JM (1990) The use of a run-in to enhance compliance. Stat Med 9:87–93