Gender and Crime

- First Online: 02 October 2021

Cite this chapter

- Tanay Maiti 3 &

- Lukus Langan 4

653 Accesses

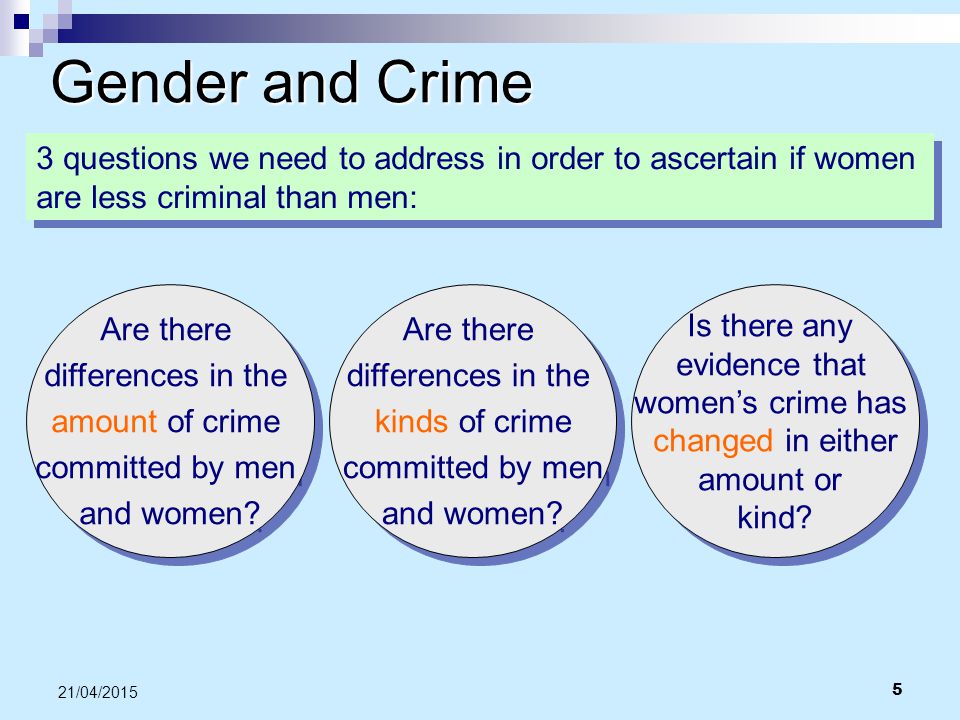

Crime is a heterogeneous social phenomenon and does not merely reflect deviant behaviour that is incompatible with society’s laws. Criminality can be used as a lens through which greater insight into a society’s economic and moral values might be gleaned, but within the field of criminology, there seems to be a dearth of dedicated research into the relationship between gender and criminality. Indeed, gender-specific crimes tend to occur at higher rates within developing, low-, and middle-income countries, where one gender is committing or being victimized more so than another gender for specific crimes. Societal influences and cultural norms, as well as the role of the criminal justice system, undoubtably shape the ways in which women and men are able to be both the victims and the perpetrators of various criminal acts. By improving our understanding of this topic and by collecting further evidence of reliable predictors of criminality, research into the relationship between gender and crime will ideally contribute towards a society that may one day be described as ‘equal’.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Adler, F., & Adler, H. M. (1975). Sisters in crime: The rise of the new female criminal . McGraw-Hill.

Google Scholar

Applin, S., & Messner, S. F. (2015). Her American dream. Feminist Criminology, 10 (1), 36–59.

Article Google Scholar

Archer, J. (2009). Does sexual selection explain human sex differences in aggression? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 32 , 249–311.

Atwell, M. W. (2002). Equal protection of the law? Gender and justice in the United States . Peter Lang.

Bajpai, A. B. (2005). Female criminality in India . Rawat Publications.

Ballinger, A. (2000). Dead woman walking . Ashgate.

Ballinger, A. (2007). Masculinity in the dock: Legal responses to male violence and female retaliation in England and Wales, 1900–1965. Social & Legal Studies, 16 (4), 459–481.

Belknap, J. (2007). The invisible woman: Gender, crime, and justice (3rd ed.). Wadsworth.

Blackwell, B. S., Sellers, C. S., & Schlaupitz, S. M. (2002). A power-control theory of vulnerability to crime and adolescent role exits-revisited. Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, 39 , 199–218.

Campbell, A. (1995). A few good men: Evolutionary psychology and female adolescent aggression. Ethology and Sociobiology, 16 (2), 99–123.

Campbell, A. (2013). The evolutionary psychology of women’s aggression. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 368 (1631), 20130078.

Chesney-Lind, M., & Shelden, R. G. (2014). Girls, delinquency, and juvenile justice (4th ed.). Wiley Inc.

Choudhury, T., & Choudhury, R. (2020). The conversation: Understanding young women’s childhood and its impact on mental health at the university counselling centre. Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Studies, 2 (4), 159–169.

Daly, K., & Chesney-Lind, M. (1988). Feminism and criminology. Justice Quarterly, 5 (4), 497–538.

Daly, M., & Wilson, M. (1988). Homicide (5th ed.). Transaction Publishers.

Darwin, C. (1871). The descent of man and selection in relation to sex . John Murray.

Book Google Scholar

DeLisi, M., & Vaughn, M. G. (2016). Correlates of crime. In A. R. Piqeuro (Ed.), The handbook of criminological theory (pp. 18–36). Wiley.

Dibble, E. R., Goldey, K. L., & van Anders, S. M. (2017). Pair bonding and testosterone in men: Longitudinal evidence for trait and dynamic associations. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 3 , 71–90.

Drèze, J., & Khera, R. (2000). Crime, gender, and society in India: Insights from homicide data. Population and Development Review, 26 (2), 335–352.

Durrant, R. (2019). Evolutionary approaches to understanding crime: Explaining the gender gap in offending. Psychology, Crime & Law, 25 (6), 589–608.

Edwardes, S. M. (1924). Crime in India (reprinted 1988) . Printwell Publishers.

Ellis, L. (1989). Theories of rape: Inquiries into the causes of sexual aggression . Taylor and Francis.

Ellis, L. (2005). A theory explaining biological correlates of criminality. European Journal of Criminology, 2 (3), 287–315.

Gillies, G. E., & McArthur, S. (2010). Estrogen actions in the brain and the basis for differential action in men and women: A case for sex-specific medicines. Pharmacological Reviews, 62 , 155–198.

Goldey, K. L., & van Anders, S. M. (2011). Sexy thoughts: Effects of sexual cognitions on testosterone, cortisol, and arousal in women. Hormones and Behavior, 59 , 754–764.

Gundappa, A., & Rathod, P. B. (2012). Violence against women in India: Preventive measures. Indian Streams Research Journal, 2 (4), 1–4.

Hagan, J., Gillis, A. R., & Simpson, J. (1985). The class structure of gender and delinquency: Toward a power-control theory of common delinquent behavior. American Journal of Sociology, 90 , 1151–1178.

Heidensohn, F. (2010). The deviance of women: A critique and an inquiry. The British Journal of Sociology, 61 (s1), 111–126.

Heirigs, M. H., & Moore, M. D. (2018). Gender inequality and homicide: A cross-national examination. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 42 (4), 273–285.

Islam, M. J., Banarjee, S., & Khatun, N. (2014). Theories of female criminality: A criminological analysis. International Journal of Criminology and Sociological Theory, 7 (1), 1–8.

Iyer, L., et al. (2012). The power of political voice: Women’s political representation and crime in India. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 4 (4), 165–193.

Jacobs, P. A., et al. (1965). Aggressive behavior, mental sub-normality and the XYY male. Nature, 208 (5017), 1351–1352.

Joseph, M. G. C., et al. (2014). Asian passengers’ safety study: The problem of sexual molestation of women on trains and buses in Chennai, India. Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology, 27 (1), 57–74.

Kalokhe, A., et al. (2016). Domestic violence against women in India: A systematic review of a decade of quantitative studies. Global Public Health, 12 (4), 498–513.

Koeppel, M. D. H., Rhineberger-Dunn, G. M., & Mack, K. Y. (2015). Cross-national homicide: A review of the current literature. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 39 (1), 47–85.

Kumari, N. (2009). Socio Economic profile of women prisoners. Language in India: Strength for Today and Bright Home for Tomorrow, 9 (2), 134–259.

Lelaurain, S., et al. (2018). Legitimizing intimate partner violence: The role of romantic love and the mediating effect of patriarchal ideologies. Journal of Interpersonal Violence , Advanced online publication, 886260518818427

Lloyd, A. (1995). Doubly deviant, doubly damned: Society’s treatment of violent women . Penguin Books.

Lodha, P., et al. (2018). Incentives of female offenders in criminal behavior: An Indian perspective. Violence and Gender, 5 (4), 202–208.

Loukaitou-Sideris, A., & Fink, C. (2008). Addressing women’s fear of victimization in transportation settings: A survey of US transit agencies. Urban Affairs Review, 44 (4), 554–587.

Madhurima, N. (2009). Women crime and prisoners Life . Deep and Deep Publishers.

Malik, J. S., & Nadda, A. (2019). A cross-sectional study of gender-based violence against men in the rural area of Haryana, India. Indian Journal of Community Medicine: Official Publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine, 44 (1), 35–38.

McCarthy, B., Hagan, J., & Woodward, T. S. (1999). In the company of women: Structure and agency in a revised power-control theory of gender and delinquency. Criminology, 37 , 761–788.

McEwan, B. S., & Milner, T. A. (2017). Understanding the broad influence of sex hormones and sex differences in the brain. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 95 , 24–39.

Mili, P. M. K., & Cherian, N. S. (2015). Female criminality in India: Prevalence, causes and preventive measures. International Journal of CrimiNal Justice Sciences, 10 (1), 65–76.

Nadda, A., et al. (2018). Study of domestic violence among currently married females of Haryana India. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 40 (60), 534–539.

NCRB (2018). Prison statistics India 2018. Accessed May 15, 2020 from https://ncrb.gov.in//prison-statistics-india-2018 (online)

Nielsen, J., et al. (1973). A psychiatric-psychological study of patients with the XYY syndrome found outside of institutions. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 49 (2), 159–168.

O’Donovan, R., & Völlm, B. (2018). Klinefelter’s syndrome and sexual offending—A literature review. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 28 (2), 132–140.

Oxford, J., Ponzi, D., & Geary, D. C. (2010). Hormonal responses differ when playing violent video games against and ingroup and an outgroup. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31 , 201–209.

Parker, K. F., & Reckdenwald, A. (2008). Women and crime in context: Examining the linkages between patriarchy and female offending across space. Feminist Criminology, 3 (1), 5–24.

Pattanaik, J. K., & Mishra, N. N. (2001). Social change and female criminality in India. Social Change, 31 (3), 103–110.

Peper, J. S., & Dahl, R. E. (2013). Surging hormones: Brain-Behavior interactions during puberty. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22 (2), 134–139.

Phadke, S. (2010). Gendered usage of public spaces: A case study of Mumbai. In: S. Pilot & L. Prabhu (Eds.), The fear that stalks: Gender-Based violence in public spaces (pp. 51–80). New Delhi, India: Zubaan.

Pollak, O. (1950). The Criminality of Women . A.S. Barnes.

Puts, D., Bailey, D. H., & Reno, P. L. (2016). Contest competition in men. In D. M. Buss (Ed.), Handbook of evolutionary psychology (2nd ed., pp. 385–402). Wiley.

Rudd, J. (2001). Dowry-murder. Women’s Studies International Forum, 24 (5), 513–522.

Saxena, R. (1994). Women and crime in India: A study in sociocultural dynamics . South Asia Books.

Sharma, B. R. (1993). Crime and women: A pscyho-diagnostic study of female criminality . Indian Institute of Public Administration.

Sheldon, W. H., Hartl, E. M., & McDermott, E. (1949). Varieties of delinquent youth. An introduction to constitutional psychiatry . Harper and Brothers.

Simon, R. (1975). Women and crime . Lexington Books.

Smart, C. (1976) Women, crime and criminology: A feminist critique . London, UK: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Spohn, C., & Beichner, D. (2000). Is preferential treatment of female offenders a thing of the past? A multisite study of gender, race, and imprisonment. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 11 , 149–184.

Steffensmeier, D. (1980). Sex differences in patterns of adult crime, 1965–77: A review and assessment. Social Forces, 58 , 1080–1108.

Steffensmeier, D., et al. (2005). An assessment of recent trends in girls’ violence using diverse longitudinal sources: Is the gender gap closing? Criminology, 43 , 355–406.

Steffensmeier, D., & Allan, E. (1996). Gender and crime: Toward a gendered theory of female offending. Annual Review of Sociology, 22 (1), 459–487.

Stochholm, K., et al. (2012). Criminality in men with Klinefelter’s syndrome and XYY syndrome: A cohort study. BMJ Open, 2 (1), e000650.

Tripathi, K., Borrion, H., & Belur, J. (2017). Sexual harassment of students on public transport: An exploratory study in Lucknow, India. Crime Prevention and Community Safety, 19 , 240–250.

Ugwu, J., & Britto, S. (2015). Perceptually contemporaneous offenses: Explaining the sex-fear paradox and the crimes that drive male and female fear. Sociological Spectrum, 35 (1), 65–83.

van Anders, S. M. (2010). Chewing gum has large effects on salivary testosterone, estradiol, and secretory immunoglobulin A assays in women and men. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 35 , 305–309.

van Anders, S. M., Tolman, R. M., & Volling, B. L. (2012). Baby cries and nurturance affect testosterone in men. Hormones and Behavior, 61 , 31–36.

Visaria, L. (2000). Violence against women: A field study. Economic & Political Weekly, 35 (20), 1742–1751.

Walby, S. (1990). Theorizing Patriarchy . B. Blackwell.

Warr, M. (1984). Fear of victimization: Why are women and the elderly more afraid? Sociological Science Quarterly, 6 , 681–702.

Warr, M. (1985). Fear of rape among urban women. Social Problems, 32 (3), 238–250.

Whaley, R. B., & Messner, S. F. (2002). Gender equality and gendered homicides. Homicide Studies, 6 (3), 188–210.

WHO. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence . WHO.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychiatry, Jagannath Gupta Institute of Medical Science and Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

Tanay Maiti

Jindal Institute of Behavioural Sciences, O.P. Jindal Global University, Sonipat, Haryana, India

Lukus Langan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Sanjeev P. Sahni

Poulomi Bhadra

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Maiti, T., Langan, L. (2021). Gender and Crime. In: Sahni, S.P., Bhadra, P. (eds) Criminal Psychology and the Criminal Justice System in India and Beyond. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-4570-9_7

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-4570-9_7

Published : 02 October 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-16-4569-3

Online ISBN : 978-981-16-4570-9

eBook Packages : Law and Criminology Law and Criminology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Gender and Crime

Introduction, general overviews.

- Female Offenders

- Gendered Crime Rates

- Girls and Juvenile Delinquency

- Victimization

- Sexual Violence

- Domestic Violence

- Sentencing Female Offenders

- Supervision of Women in the Community

- Incarcerated Women

- Women in Criminal Justice Professions

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Mass Incarceration in the United States and its Collateral Consequences

- Social Construction of Crime

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Consumer Credit and Debt

- Economic Globalization

- Global Inequalities

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Gender and Crime by Francesca Spina LAST REVIEWED: 26 February 2020 LAST MODIFIED: 26 February 2020 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756384-0243

Scholars and practitioners paid little attention to the subject of gender and crime until the 1960s. However, this topic began to gain attention as a result of the political and social changes of the women’s movement, as well as the civil rights movement. Prior to that, men engaging in crime was the norm, and women who engaged in crime were seen as anomalies. Criminology scholars started to think of gender and crime differently, recognizing how the vastness of this topic could lead to opportunities in this previously under-researched area. Researchers began examining issues related to inequality, differences in offending between men and women, and female victims of male violence. In the 21st century, scholars often focus on intersectionality, taking the effects of race/ethnicity, class, sexuality, and other factors into consideration. Furthermore, research on gender and crime also examines the different pathways men and women have into crime. Consequently, it is important to research prevention and treatment programs that address female offenders’ unique needs, including histories of childhood trauma, mental illness, and substance abuse. Finally, as more women are entering the field of criminal justice, research has focused on some of the challenges they face in law enforcement and legal professions.

There are a number of comprehensive textbooks on gender and crime. These books present issues on gender and crime by examining research, policy, and practice. They cover topics such as theories of offending, offending patterns, victimization, justice experiences, women as criminal justice professionals, and juveniles. While each of these textbooks offers a wide variety of topics related to gender and crime, they are each unique. Thurma 2019 examines the influence of female grassroots activists who fought against gendered violence in the 1970s. Belknap 2015 focuses on current issues related to gender in crime such as sex trafficking and stalking, while Chesney-Lind and Pasko 2013 concentrate on narratives to complement their material. Meanwhile, Chesney-Lind and Shelden 2014 focus on issues in gender and crime specific to girls and delinquency, while Mallicoat 2018 devotes much attention to matters related to race and diversity. Furthermore, Barak et al. 2018 emphasize the roles of intersectionality and privilege in the criminal justice system, while Peterson and Panfil 2014 discuss issues that are unique to LGBTQ populations. Finally, Barberet 2014 focuses on international topics related to women and crime, and Thompson and Gibbs 2017 concentrate specifically on deviance.

Barak, Gregg, Paul Leighton, and Allison Cotton. 2018. Class, race, gender, and crime: The social realities of justice in America 5th ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Introduces readers to the correlates of crime (e.g., gender, race, and class), as well as how these factors intersect. The authors discuss the complexity of gender and race in different aspects of the criminal justice system, including law enforcement, the courts, and corrections. They also explore how power and privilege in the United States shape our understanding of crime.

Barberet, Rosemary. 2014. Women, crime and criminal Justice: A global enquiry . New York: Routledge.

This book focuses on international issues related to women and crime. The book discusses global factors related to female offenders, violence against women, and women working in justice-related professions. Topics include globalization, women’s activism, femicide, sex trafficking, and women’s access to justice.

Belknap, Joanne. 2015. The invisible woman: Gender, crime and justice . 4th ed. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning.

Provides an overview of many issues related to crime and justice. It covers female offending, including theories related to their offending, processing women in the system, and incarcerated women. It also discusses gender-based abuse, such as sexual abuse and domestic violence. Finally, this book includes sections on women working in law enforcement, correctional settings, and the courts.

Chesney-Lind, Meda, and Lisa Pasko. 2013. The female offender: Girls, women and crime . 3d ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

This is another comprehensive book looking at offending patterns of women and girls. It discusses girls’ delinquency, girls and violence, as well as girls in the juvenile justice system. Furthermore, it covers trends in women’s crime, sentencing women to prison, and supervising female offenders in the community.

Chesney-Lind, Meda, and Randall Shelden. 2014. Girls, delinquency and juvenile justice . 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

Covers topics specific to girls and delinquency. They discuss the nature and extent of girls’ delinquency, girls who join gangs, and theories related to their delinquency. Moreover, this book also covers pathways to girls’ delinquency, girls and the juvenile justice system, and programs to help girls who have been involved in the system.

Mallicoat, Stacy. 2018. Women, gender and crime: A text/reader . 3d ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Discusses issues of gender and crime by incorporating themes of race and diversity. Topics include theories of victimization, female victimization, women offenders, girls and delinquency, sentencing female offenders, women and the correctional system, and women working in the justice system.

Peterson, Dana, and Vanessa R. Panfil, eds. 2014. Handbook of LGBT communities, crime, and justice . New York: Springer.

LGBTQ populations are under-researched among criminology scholars. This book explores LGBTQ communities and their offending patterns. It also examines their experiences with law enforcement, the courts, and corrections. Discusses topics such as same-sex intimate partner violence, transgender sex workers, transgender correctional policies, LGBT police officers, and bullying LGBT youth.

Thompson, William, and Jennifer Gibbs. 2017. Deviance and deviants: A sociological approach . Malden, MA: John Wiley.

Examines how deviance is defined and constructed, as well as what it means to be a “deviant.” Covers sexual, physical, and mental deviances, in addition to deviant occupations. Topics include substance abuse, suicide, and cyber deviance, among others. Throughout the book, the authors also debunk many myths associated with being deviant.

Thurma, Emily L. 2019. All our trials: Prisons, policing, and the feminist fight to end violence . Champaign: Univ. of Illinois Press.

Focuses on the organizing and influence of female grassroots activists who fought against gendered violence and incarceration in the 1970s. Discusses the activists’ struggles to fight for gender, racial, and economic justice. She uses historical research and narratives to discuss local coalitions and national gatherings that aimed to showcase issues in marginalized communities and to end violence.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Sociology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Actor-Network Theory

- Adolescence

- African Americans

- African Societies

- Agent-Based Modeling

- Analysis, Spatial

- Analysis, World-Systems

- Anomie and Strain Theory

- Arab Spring, Mobilization, and Contentious Politics in the...

- Asian Americans

- Assimilation

- Authority and Work

- Bell, Daniel

- Biosociology

- Bourdieu, Pierre

- Catholicism

- Causal Inference

- Chicago School of Sociology

- Chinese Cultural Revolution

- Chinese Society

- Citizenship

- Civil Rights

- Civil Society

- Cognitive Sociology

- Cohort Analysis

- Collective Efficacy

- Collective Memory

- Comparative Historical Sociology

- Comte, Auguste

- Conflict Theory

- Conservatism

- Consumer Culture

- Consumption

- Contemporary Family Issues

- Contingent Work

- Conversation Analysis

- Corrections

- Cosmopolitanism

- Crime, Cities and

- Cultural Capital

- Cultural Classification and Codes

- Cultural Economy

- Cultural Omnivorousness

- Cultural Production and Circulation

- Culture and Networks

- Culture, Sociology of

- Development

- Discrimination

- Doing Gender

- Du Bois, W.E.B.

- Durkheim, Émile

- Economic Institutions and Institutional Change

- Economic Sociology

- Education and Health

- Education Policy in the United States

- Educational Policy and Race

- Empires and Colonialism

- Entrepreneurship

- Environmental Sociology

- Epistemology

- Ethnic Enclaves

- Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis

- Exchange Theory

- Families, Postmodern

- Family Policies

- Feminist Theory

- Field, Bourdieu's Concept of

- Forced Migration

- Foucault, Michel

- Frankfurt School

- Gender and Bodies

- Gender and Crime

- Gender and Education

- Gender and Health

- Gender and Incarceration

- Gender and Professions

- Gender and Social Movements

- Gender and Work

- Gender Pay Gap

- Gender, Sexuality, and Migration

- Gender Stratification

- Gender, Welfare Policy and

- Gendered Sexuality

- Gentrification

- Gerontology

- Globalization and Labor

- Goffman, Erving

- Historic Preservation

- Human Trafficking

- Immigration

- Indian Society, Contemporary

- Institutions

- Intellectuals

- Intersectionalities

- Interview Methodology

- Job Quality

- Knowledge, Critical Sociology of

- Labor Markets

- Latino/Latina Studies

- Law and Society

- Law, Sociology of

- LGBT Parenting and Family Formation

- LGBT Social Movements

- Life Course

- Lipset, S.M.

- Markets, Conventions and Categories in

- Marriage and Divorce

- Marxist Sociology

- Masculinity

- Mass Incarceration in the United States and its Collateral...

- Material Culture

- Mathematical Sociology

- Medical Sociology

- Mental Illness

- Methodological Individualism

- Middle Classes

- Military Sociology

- Money and Credit

- Multiculturalism

- Multilevel Models

- Multiracial, Mixed-Race, and Biracial Identities

- Nationalism

- Non-normative Sexuality Studies

- Occupations and Professions

- Organizations

- Panel Studies

- Parsons, Talcott

- Political Culture

- Political Economy

- Political Sociology

- Popular Culture

- Proletariat (Working Class)

- Protestantism

- Public Opinion

- Public Space

- Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA)

- Race and Sexuality

- Race and Violence

- Race and Youth

- Race in Global Perspective

- Race, Organizations, and Movements

- Rational Choice

- Relationships

- Religion and the Public Sphere

- Residential Segregation

- Revolutions

- Role Theory

- Rural Sociology

- Scientific Networks

- Secularization

- Sequence Analysis

- Sex versus Gender

- Sexual Identity

- Sexualities

- Sexuality Across the Life Course

- Simmel, Georg

- Single Parents in Context

- Small Cities

- Social Capital

- Social Change

- Social Closure

- Social Control

- Social Darwinism

- Social Disorganization Theory

- Social Epidemiology

- Social History

- Social Indicators

- Social Mobility

- Social Movements

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Networks

- Social Policy

- Social Problems

- Social Psychology

- Social Stratification

- Social Theory

- Socialization, Sociological Perspectives on

- Sociolinguistics

- Sociological Approaches to Character

- Sociological Research on the Chinese Society

- Sociological Research, Qualitative Methods in

- Sociological Research, Quantitative Methods in

- Sociology, History of

- Sociology of Manners

- Sociology of Music

- Sociology of War, The

- Suburbanism

- Survey Methods

- Symbolic Boundaries

- Symbolic Interactionism

- The Division of Labor after Durkheim

- Tilly, Charles

- Time Use and Childcare

- Time Use and Time Diary Research

- Tourism, Sociology of

- Transnational Adoption

- Unions and Inequality

- Urban Ethnography

- Urban Growth Machine

- Urban Inequality in the United States

- Veblen, Thorstein

- Visual Arts, Music, and Aesthetic Experience

- Wallerstein, Immanuel

- Welfare, Race, and the American Imagination

- Welfare States

- Women’s Employment and Economic Inequality Between Househo...

- Work and Employment, Sociology of

- Work/Life Balance

- Workplace Flexibility

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.151.41]

- 185.80.151.41

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

6 Feminist Criminologies’ Contribution to Understandings of Sex, Gender, and Crime

Kerry Carrington is Professor of Law in the School of Justice at Queensland University of Technology.

Jodi Death is a Lecturer in the School of Justice at Queensland University of Technology.

- Published: 01 July 2014

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This essay provides an overview of the contribution of feminist criminologies to an intersectional analysis of sex, gender, and crime. Dozens of scholars have participated in these debates over the past four decades. This essay draws on interviews with ten internationally distinguished scholars to reflect upon the distinctive contributions of feminism to our knowledge about sex, gender, and crime. The essay concludes that feminist work within criminology continues to face a number of lingering challenges in a world where concerns about gender inequality are marginalized; where tensions around the best strategies for change remain contentious; where hard questions about the female capacity to commit violence are avoided; and where a backlash, antifeminist politics distorts the responsibility of feminism for female violence. This essay critically reviews these lingering challenges—locating feminist approaches at the center and not the periphery of advancing knowledge about gender, sex, and crime.

6.1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, feminist criminology has done much to advance our knowledge about the complex intersections among gender, sex, and crime. Early feminist critiques of criminology regarded the discipline’s main problem as its neglect of the female sex; the proposed remedy to the problem was to add “women” to the criminological knowledge bank. However, a subsequent wave of feminist work argued that this was no solution to the male-centric bias of criminology, a discipline that generalized theories of crime from observations of mostly male prisoners and offenders. In the 1990s feminist theorists called for knowledge about women, gender, and crime to be generated from outside what they saw as the hopelessly phallocentric discipline of criminology. In its turn, this approach too was subject to strident internal feminist critique and discredited as woman-centric and essentialist in its concepts and approach to knowledge. A theory based singularly on sex or gender, it was argued, was insufficient to explain the abundance of women of color, indigenous women, and women from impoverished backgrounds who were susceptible to policing, criminalization, and imprisonment. Only by incorporating the tapestry of interconnections among social position, race, ethnicity, location, and gender could the overrepresentation of particular groups of women in the criminal justice system be understood.

Dozens of scholars and activists have participated in these debates over the past four decades. This contribution to this handbook involves interviews with ten distinguished scholars whose contributions to this debate are recognized internationally. Through the commentary provided by these scholars, this essay examines some of the distinctive contributions of feminism to knowledge about sex, gender, and crime, as well as some of the challenges it continues to face in the field of criminology.

Feminist work is characterized by its focus on producing transformative research to improve or reform the criminal justice system; it has led to significant reforms and policies in the criminal justice field, especially in how the victim is treated by that system. This essay reviews a sample of work at the forefront of making these sustained and important contributions. More recently, and within the past decade especially, research on gender and crime has faced a political antifeminist backlash as rising rates of women and girls as perpetrators of crime are recorded internationally. Feminism has been mistakenly blamed by some for these seismic historical changes. Although contested by some, the recorded rise in criminal activity by girls and women provides a number of challenges to feminist criminology in understanding, deconstructing, and explaining why this has occurred. One view is that the narrowing of the gender gap for recorded crimes, especially those relating to interpersonal violence, is an artifact of new forms of policing of and social control over young women in particular. Another view is that young women may indeed have altered their cultural and social behavior and are becoming more violent. A middle option argues that the reasons for the recorded rises in female crime in the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, and Australia are variable and uncertain but probably include a combination of cultural, social, behavioral, and policy responses. This unresolved debate is explored in the last section of the essay.

Feminist work within criminology continues to face a number of lingering challenges, most notably in relation to the struggle to maintain relevance in a world where concerns about gender inequality are marginalized and considered as historical relics, not contemporary issues; where there are ongoing tensions around the best strategies for change as well as difficulties in challenging distorted representations of female crime and violence; and where a backlash, antifeminist politics seeks to discredit explanations that draw a link between sex, gender, and crime. This essay critically reviews these lingering challenges—locating feminist approaches (of which there are many) at the center and not the periphery of advancing knowledge about gender, sex, and crime.

6.2. Methodology

This essay incorporates data gathered from ten internationally renowned scholars in the United Kingdom, Canada, the United States, and Australia. All have strong records of publication and research, held key editorial roles on world-leading criminology journals, received distinguished scholarly awards, and served as editors of prestigious international collections. Each scholar received an e-mail information sheet, consent form, and list of questions. Ten participants responded: Frances Heidensohn (London School of Economics and Political Science, United Kingdom), a pioneer in the study of gender and crime in the 1960s and general editor of the British Journal of Sociology ; Sandra Walklate (Eleanor Rathbone Chair of Sociology, University of Liverpool, United Kingdom), editor of the Routledge Handbook on Victimology and arguably the world’s leading authority in this field; Loraine Gelsthorpe (Cambridge University, United Kingdom), past president of the British Society of Criminology, book review editor for the Howard Journal , and a member of the editorial board of Criminology and Criminal Justice ; Jo Phoenix (Durham University, United Kingdom), director of the Centre for Studies in Sex and Sexuality and book review editor for the British Journal of Criminology; Nicole Rafter (Northeastern University, United States), awarded the American Society of Criminology’s Sutherland Prize for her contribution to gender and justice debates; Molly Dragiewicz (University of Ontario Institute of Technology, Canada), recipient of the 2009 New Scholar Award from the American Society of Criminology’s Division on Women and Crime and the 2012 Young Critical Criminology Scholar Award for her contributions to the study of violence against women; Nancy Wonders (Northern Arizona University, United States), past chair of the American Society of Criminology’s Division on Women and Crime, a member of the editorial board of Feminist Criminology , and a leading author and activist; Ngaire Naffine (University of Adelaide, Australia), professor of law and author of several seminal texts on feminist theory, gender, criminology, and law; Kathy Daly (Griffith University, Australia), former president of the Australian and New Zealand Society of Criminology who, over the past twenty years, has undertaken important research into the intersections among gender, race, and justice both in Australian and US jurisdictions; and Judith Bessant (Queensland University of Technology, Australia), adjunct professor and author of a number of widely read articles and books on the sociology of youth and leading expert on youth justice in Australia. Participants were asked to reflect on a range of issues, including significant developments in feminist and critical criminology, key challenges for feminist criminology, and the highlights of their careers.

Interestingly, few respondents identified themselves as “feminist,” and most had qualms about the label, wanting to avoid the chasm of identity politics. Identity politics and knowledge construction have been thoroughly problematized by post-structuralist theory in particular, so this is hardly surprising. Most preferred their contributions be interpreted in relation to a wider field of scholarship, one that explores the connections among crime, victimization, gender, globalization, and justice and in which gender is an important but not a singular focus. Other participants actively identified with feminist approaches and linked this specifically to an “activist” aspect of their career. These scholars also stressed the links between injustices that affect women as victims or offenders and other harms and social injustices, such as poverty and gendered violence. Nine participants returned their answers to the research questions in writing, via e-mail, and one provided a voice recording that was later transcribed. Responses were thematically analyzed by both authors of this essay (independently and then collectively) and used to inform the analysis in this essay. The aim of this essay is to draw on these considered responses to reflect on the achievements and limitations of feminist criminologies in advancing understanding of sex, gender, and crime.

6.3. Gendering the Study of Crime and Deviance

In a now famous article, Heidensohn (1968 , p. 171) describes the study of gender, women, and deviance “as lonely uncharted seas of human behaviour.” Despite the ubiquitous sex differential apparent in recorded crime and imprisonment rates, she notes how entire bodies of research either persistently overlooked sex differences or marginalized women’s deviance as sexual deviance. These neglects of sex differences, Heidensohn (p. 171) muses, are “particularly interesting to the sociologist of sociology,” a premonition of what later became a preoccupation of feminist criminology: the gender-blindness of criminology. As Miller (2010 , p. 134) points out in her review of this 1968 article, this was one of the first calls for an examination of the “gendered sociology of knowledge.” In response to our survey, Heidensohn elaborates on the context in which she wrote that pioneering article:

When I published my first article in 1968 there was no recognition of gender issues, no attention paid to the sex crime ratio, very little research on women and girls, what there was—was stereotyped and marginal. Familial violence was largely ignored, its gendered nature not considered. All that has altered, thanks to the effects of feminism and the efforts of feminist scholars.

In 1976 Smart undertook the first book-length critique of theories of female crime and deviance. Her painstaking critique of the ideological misrepresentations of sex and gender embedded in biological, psychological, and sociological theories of crime and deviance spawned a new generation of researchers who were more attentive to, and critical of, the gender blindness of deviance theory in both sociology and criminology ( Heidensohn 1985 ). This first wave of feminist scholarship took issue with two main aspects of criminology: first, its omission of women and second, when it did attend to women, its misrepresentation of female offenders as doubly deviant ( Heidensohn 1968 ; Bertrand 1969 ; Klein 1973 ; Adler 1975 ). As Nicole Rafter sums up in response to our questions, “Women were ignored as victims, offenders, and prisoners. The challenge was sexism.” To correct this sexism and gender blindness, these pioneering feminist scholars argued for the inclusion of women in studies of crime and punishment ( Naffine 1987 ; Rafter 2000 ; Mason and Stubbs 2010 ). While this new research aided our understanding of the complexity and patterns of female crime and deviance, it also had notable limitations, as Nancy Wonders points out:

Importantly, early feminists urged a focus on women and girls, drawing attention to their invisibility within the field of criminology. This lead to important research on girls and women, but much of it tended to simply “add women and stir.”

Although they added sex to the analysis of crime and deviance, the early pioneering studies of girls, women, and crime left unchallenged the core assumptions and methodologies of mainstream criminology ( Naffine 1997 ). Feminist research had to do more than just add women to existing criminological frameworks if its objective was to create more sophisticated understandings about gender, sex, and crime. The feminist project had to broaden to include a critique of criminology’s state-based definitions of crime that excluded manifold socially invisible harms to women (such as rape in marriage and domestic violence), of criminology’s inherent phallocentricism in generalizing theories of crime based on observations of men, and of the positivist methodologies that produced this uncritical knowledge ( Allen 1989 ; Cain 1990 ; Young 1992 ; Caulfield and Wonders 1993 ; Green 1993 ; Heidensohn and Rafter 1995 ; Naffine 1997 ).

These 1990s feminist perspectives drew on a deeper skepticism about the phallocentricism engendered by disciplines such as history, the natural sciences, sociology, and criminology. This theoretically informed body of feminist scholarship rejected the positivist research methods and their claims of neutrality that dominated mainstream criminology. Epistemological debates about the relationship between politics and knowledge were and remain topics of dispute in feminist criminology. The main distinctions are drawn between empiricist, standpoint, and poststructuralist feminisms. Feminist empiricism aims to correct the masculine bias of the methodologies of the human sciences but accepts its claims that knowledge can be causal and universal. Standpoint feminist approaches reject outright traditional research methodologies as masculinist and aim to construct feminist ways of knowing through women’s experience ( Stanley and Wise 1983 ), while postmodern and poststructuralist feminisms reject the epistemological assumptions that truth can be impartial, ahistorical, singular, or universal. Consequently, there is no unified feminist perspective but rather a collage of theoretical and methodological influences that draw on sociology, sociolegal studies, cultural studies, post-structuralism, postcolonialism, and neo-Marxism and that have inspired a body of disparate work on gender and crime ( Gelsthorpe 1989 ; Carrington 1994 ; Young 1996 ; Naffine 1997 ). Lorraine Gelsthorpe summarizes the twin intellectual aspirations of feminist criminology in the following way:

I think that there have been two major feminist projects. The first [is] a substantive project which has raised awareness of discrimination, awareness of the complexities of victimhood, and awareness of the distinctive needs of women offenders and victims. The second project is a methodological and epistemological one; here feminist contributions have been to question methodological traditions by focusing on methodological plurality and the importance of deconstructionist approaches.

Feminist standpoint perspectives rejected androcentric and male-centric production of knowledge and sought out methods that allowed alternate voices, women’s voices, to be heard. As such, the primary objectives of standpoint feminisms were to recognize women’s contributions to knowledge development and to facilitate further contributions ( Harding 1986 ). While feminist standpoint perspectives advanced understandings of crime and deviance beyond the gender-neutral or gender-blind boundaries of the criminological canon, they ran into their own conceptual difficulties. This particular feminist methodology, popular in the 1980s and 1990s, tended to universalize women as the “other,” conflate sex with gender, and essentialize understandings of the relationship between sex, gender, and crime ( Rice 1990 ). By solely focusing on the experiences of the female sex—whether as victims or offenders—the historical, cultural, and material diversity of women’s offending and victimization was overlooked ( Gelsthorpe 1989 ). It was too confidently assumed that commonalities shared among the female sex made it possible to analyze women as a singular unitary subject of history ( Allen 1990 ), despite their rich social diversity. That indigenous women, women of color, and women from visible ethnic minorities were persistently overrepresented in prison and before the courts as offenders in the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, and Australia ( Carlen 1983 ; Carrington 1993 ; Rice 1990 ; Daly 1994 ) exposed the folly of feminist standpoint perspectives for fully comprehending the links between gender and crime and the need to develop more complex understandings of identity, for reasons Nancy Wonders explains:

Over the last decade, in particular, many feminists have argued that a focus on gender alone is overly reductionist. Identities intersect in complex ways and the salience of particular identity categories may change over time. As a result of this reality, feminists emphasize the need to consider gender AND race AND ethnicity AND social class AND nationality AND sexual orientation—and to be open to new and emerging identities and forces that shape gendered realities. Within criminology, this has been particularly important given the very different experiences with the justice system, for example, of poor Black women compared with rich white women.

More sophisticated analyses of gender, social identity, and crime meant, as Smart (1990 , p. 83) puts it that, “[f]eminism had to abandon its early frame-work and to start to look for other ways to think which did not subjugate other subjectivities.” Post-structuralist and deconstructionist frameworks emerged that did not insist on a singular set of relationships among gender, sex, deviance, or crime and instead sought to locate their analysis more concretely in the field of power relations. Sex, as a biological category, was no longer conflated with gender, a social construction. The aim of these particular feminist analyses was to deconstruct both the power relations underpinning the truth claims of law and the state’s criminal justice institutions and to expose how social constructions of gender and power shape experiences and responses to crime and deviance ( Smart 1990 ). A rich body of feminist scholarship on intra- and intersexed experiences took root drawing on social constructionist theories of gender and power ( Tauchert 2002 ). Nancy Wonders summarizes the profound significance of these concepts:

Perhaps the most significant contribution feminism has made to criminology and victimology is the addition of the concept of “gender” to our analytic tool kit....The concept of “gender” draws needed attention to broader forces of social stratification, arguing that “gender” is not a natural fact; instead, it is a social construction that exists primarily to privilege one group (men) over another (women).

Feminist criminologies were no longer restricted to the sex-specific “Woman Question.” Their objects of analysis varied widely and began to include social constructions of masculinities, femininities, sexualities, and crime ( Smart 1990 ; Wonders 1996 ; Young 1996 ; Phoenix 2001 ; Phoenix and Oerton 2005 ) and the interaction of sex with other social dimensions such as migration ( Segrave, Milivojevic, and Pickering 2009 ). As Ngaire Naffine highlights in response to our questions, feminist research on gender and crime became an intellectual space for

identifying both “the man question” and “the woman question”: revealing that the main theories of crime and associated research are really about male behaviour and so tend not to be scientifically rigorous, and that interesting and informative features of female behaviour, which have much to tell us about the nature of crime and conformity, have been neglected.

This broad eclectic approach spawned an array of studies on sexual difference, morality, law, language, and the positioning of the “other” ( Threadgold 1993 ; Wonders 2006 ; Hayes, Carpenter, and Dwyer 2011 ) and on intersections among gender, ethnicity, and criminalization ( Daly 1994 ; Maher 1997 ). Nevertheless, considerable challenges to understanding gender, sex, and crime persist, with much contemporary criminological research still just adding the variable sex as an antidote to historical wrongs.

6.4. Gendering the Victim

The past three decades have seen an unprecedented rise in interest in the victim. Feminist research on the invisibility of women’s victimization has required politicians and policymakers to rethink the role and status of the victim in the criminal justice system ( Bessant and Cook 1997 ; Zedner 2003 ; Rock 2005 ; Booth and Carrington 2007 ; Walklate 2007 a , 2007 b ). The feminist activist imperative to create not only awareness of but a better response to victims of gendered crime drove the research agenda of feminist victimology in particular. Molly Dragiewicz, who has undertaken a considerable body of primary research in Canada and the United States on violence against women, argues that

[o]ne of the most important contributions of feminist scholarship to criminology has been in the production of a large, interdisciplinary research literature on violence against women and other forms of gendered violence. This research has been important theoretically and empirically because it has expanded the scope of criminology to include some of the most prevalent and damaging forms of crime. Feminist work in this area has been an essential correction to earlier misogynist and victim blaming studies as well as the lack of attention to women and crime and the gendered nature of crime.

A constellation of quite distinct feminist intellectual legacies and political work began to emerge in the 1970s with the rise of radical feminism, the women’s refuge movement, and demands to make violence a public not a private matter ( Carmody and Carrington 2000 ). Significant and influential works include Dobash and Dobash’s (1979) study of family violence and Russell’s (1975) and Brownmiller’s (1975) provocative analyses of rape. These were followed by Stanko’s (1990) work on everyday violence and Walklate’s (2007 a , 2007 b ) major and ongoing contributions in the United Kingdom, and the work of scholars like DeKeseredy (2011) and Dragiewicz (2009) in Canada and the United States. This research challenged the hidden and privatized nature of violence against women ( Gelsthorpe and Morris 1990 ). Sandra Walklate, a pioneer in this field, describes the contribution of feminist research to understanding the link between gender and victimization as “without question widening the criminological gaze to problematize what counts as crime and where crime occurs.”

Reflecting on the changes observed over her distinguished career, Frances Heidensohn recalls, “It is a huge, radical, game changing move and it is hard now to recall those pre-feminist days.” The game that changed was not only in the academe, which expanded the legitimate concerns for the disciplines of criminology and victimology to include gendered crime, but also in state and community services provided to victims of gendered crime. Feminists as researchers and activists involved on a day-to-day basis with victim advocacy services, community-based movements, and campaigns tended to be impatient for social change, a key ingredient of feminist scholarship as Nancy Wonders highlights:

A common feminist contribution, regardless of perspective, has been the commitment to social change. Using the motto that “the personal is political,” feminists have been important advocates for social change. Change must happen, not just within formal institutions, such as the justice system, but also within our everyday lives...Feminist criminologists typically believe that research should be linked to changes in policy and practice.