- Citation Generator

- Style Guides

- Chicago/Turabian Format

Writing Abstracts for a Literature Review in APA Format

Do you need to know how to write a literature review abstract in APA? You’ve come to the right place. This citation example focuses on abstract writing in an APA format style paper. Learning how to write an abstract in APA is an excellent skill to have, as it helps you develop the ability to summarize the essential points in your paper. In addition to a how-to, you can explore several APA abstract examples including a literature review abstract example.

Types of Research Papers

You may be asked to prepare various kinds of research papers as a student, including:

- Empirical study

- Theory-oriented

- Methodological

A literature review paper is one you’ll be asked to write frequently, as many times, there is not enough time in a class setting to complete extensive research. Therefore, it’s important to know how to create an abstract for your literature review.

What Is an Abstract?

An abstract is a concise summary of the purpose or aim of your research in your APA paper. You’ve probably seen an abstract a time or two when looking at a scholarly journal. These examples of abstracts in APA tell you whether the piece is worth your time to read. Abstracts vary by type but should include:

- research questions, problems, and/or a hypothesis

- research methods

- study results and conclusions

- Recommendations and implications

- critical points of a literature review

The official writing style of the American Psychological Association , APA format is designed for psychology and social science papers. Therefore, abstracts you create in this writing style are for this purpose. Additionally, per the 7th edition of APA writing style, abstracts and keywords are no longer required for student papers, unless required by your teacher.

Abstract Word Limits

The maximum word count for an APA abstract is 250 words. However, your instructor may ask for fewer words or provide you with additional guidance. Some instructors or publications may restrict the word count to 150.

How to Write an Abstract in APA

Since the abstract is a concise summary of your paper, you write it after you have finished your paper. Therefore, you have a clear idea of what to include in this short paragraph. Now, let’s explore the details of how to write and format an abstract for your APA paper.

APA Abstract Format

The abstract page is the second page of your report, right after the title page. This page is numbered 2 on your report.

- On the first line of the page, center the word Abstract in bold. (Do not underline, italicize, or otherwise format the title.)

- On the second line, start your abstract. (Do not indent.)

- Use a readable font like Times New Roman 12-point or Calibri 11-point.

- Write the abstract as a single paragraph.

- Double-space, 1-inch margins on all sides.

Inserting Keywords into an APA Abstract

In today’s digital world, it is vital to think about ways readers can find your work online. Adding keywords at the end of your abstract guides online searches. These keywords need to accurately represent the paper and be specific.

After the abstract paragraph, type Keywords: italicized and indented.

Keywords: digital print, online sources

Abstract Example in APA

This article is an examination of the history of gender demographics in the field of librarianship. The historical development and subsequent “feminization” of librarianship continues to influence the gender wage gap and the disproportionate leadership bias in the field today. This article examines the stereotyping of librarians and the cyclical effect of genderizing the profession. Consideration of current trends and data in librarian demographics demonstrates a consistent decrease in gender diversity, accompanied by a troubling lack of women leaders and executives. Additionally, this article explores options for combating the gender perceptions that negatively impact women in the library and information science fields, including management and negotiation training in graduate programs, increased emphasis on technological skills, and professional organization advocacy.

Keywords : gender, demographics, stereotyping, librarians

How to Write an Abstract for a Literature Review

When writing an abstract for a literature review, you take the same basic approach as you do for a general abstract. However, since you are reviewing other literature on a topic, you have some unique elements, including:

- First, briefly state the research topic and questions.

- Then, using the primary studies in the literature you reviewed, include the participants in the studies and the main results.

- Remember to include the conclusion of your literature review.

- Finally, finish with a sentence about any implications or future research that developed from the research presented in your paper.

Literature Review Abstract Example With Keywords

The future of books and libraries is put into question by the increasing popularity of e-books and the use of computers as text platforms. To anticipate which reading platform—print, e-readers, or computer displays—will dominate in the coming years, recent research and experimental data on the suitability of each reading platform for reading comprehension will be considered, from the perspectives of optical issues, cognition, and metacognition. It will be shown that, while printed books are most conducive to learning from longer, more challenging texts, e-readers and computer displays offer convenience and some distinct advantages to readers in particular situations. This synthesis of current research will be helpful to librarians working in digital and print book purchasing and collection development, as well as those making long-range planning decisions.

Keywords : books, digital books, e-paper, reading comprehension, cognition

Tips for Writing a Literature Review Abstract in APA

Abstracts can be challenging, especially if you are new to the abstract writing game. Get some quick tips to make abstract writing easy.

- Create a rough draft. This ensures you say everything you need to and the fluff can be edited out.

- Check out professional abstracts.

- Get feedback on your abstract.

- Keep it concise. In an abstract, staying in your word count is essential.

Sectioning Your APA Research Paper

In the seventh edition of APA style , a research paper has four sections:

A Crucial Element

Knowing how to write an abstract in APA is a critical part of your school research paper. Thus, you should put a lot of thought into creating your APA abstract and make sure it includes all the required elements. As always, be sure to follow your teacher’s guidance for the length and format of your APA paper and abstract.

Annotated Bibliography Examples

Understanding APA Literature Reviews

FAQ Writing Abstracts for a Literature Review in APA Format

What is an apa abstract example.

An example of an abstract can be found on the second page of an APA paper. The abstract provides a brief break down of the article to help readers to understand how the paper is useful to their research. An abstract example includes a page number, title (Abstract), abstract text, and keywords at the bottom.

How do you write an abstract?

To write an abstract in APA, you want to include the research questions, research methods, types of research included, conclusions, and implications of the research. The abstract is going to be less than 250 words; therefore, it needs to be concise and to the point. To make sure your abstract is concise, you can create a rough draft and edit it down.

How do you write an abstract for APA 7th edition?

To write an abstract in APA 7th edition, you need to include the page number, title abstract in bold, abstract text of fewer than 250 words, and keywords. The abstract text should provide a concise overview of your APA paper, including research questions, hypotheses, study results, and conclusions. Additionally, APA 7 edition student papers do not require an abstract.

What makes a good abstract?

A good abstract in APA is a clear, concise overview of your research paper. It includes the research topic and questions, studies reviewed, conclusions, implications, and research methods. It's less than 250 words and includes keywords at the end.

What are keywords in APA format?

The keywords in an APA format abstract make the abstract easy to search in online databases. Additionally, they provide readers with a quick idea of the general topics covered in the paper. APA abstract keywords are found at the bottom of the paper, and the word "keywords" is indented and in italics.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 4.7 / 5. Vote count: 72

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Putting APA References in Alphabetical Order

Apa citation newspaper article examples, apa style citations for quotes, paraphrasing, and references, 8 apa book reference examples.

How to Write a Literature Review

- Critical analysis

- Sample Literature Reviews

- Scaffold examples for organising Literature Reviews

- Writing an Abstract

- Creating Appendices

- APA Reference Guide

- Library Resources

- Guide References

What is an abstract?

What is an Abstract?

An abstract is a short summary of an article, essay or research findings. A well-written abstract will provide the reader with a brief overview of the entire article, including the article's purpose, methodology and conclusion. An abstract should give the reader enough detail to determine if the information in the article meets their research needs...and it should make them want to read more!

While an abstract is usually anywhere between 150 - 300 words, it is important to always establish with your teacher the desired length of the abstract you are submitting.

This excellent guide from the University of Melbourne is a great snapshot of how to write an abstract.

Here are a few links to some useful abstract examples:

University of New South Wales

University of Wollongong

Michigan State University

- << Previous: Scaffold examples for organising Literature Reviews

- Next: Creating Appendices >>

- Last Updated: Apr 8, 2024 9:14 AM

- URL: https://saintpatricks-nsw.libguides.com/lit_review

How To Write An Abstract For A Literature Review Effectively

Master the art of how to write an abstract for a literature review with this informative guide. Start creating standout abstracts today!

Table of Contents

What Is An Abstract In Literature Review

Purpose of an abstract in a literature review, consider the audience for your abstract, guidelines for writing an abstract for a literature review, general information in an abstract for a literature review, related reading, what are the 5 parts of an abstract, 1. introduction, 5. conclusion, enhanced reading and writing with unriddle's ai-powered tools, how to write an abstract for a literature review, briefly state the research topic and questions, include the participants and main results, conclude the abstract with the conclusion of your literature review, mention implications or future research, complete step-by-step guide on how to use unriddle's ai research tool, interact with documents, automatic relations, citing your sources, writing with ai, chat settings, examples of high-quality abstracts, conclusions, more examples of abstracts for literature reviews, abstract checklist for writing a good review paper, background: setting the stage for your work, aim: what goals do you intend to achieve what gap are you filling, approach: a summary of your methods, results: what are the main findings of your study, conclusions: what are the main conclusions of your research, writing guidelines, read faster & write better with unriddle for free today, ai assistant for efficient research, citation management and text generation, collaborative workspace for enhanced productivity.

- Systematic Literature Review

- Systematic Review Vs Literature Review

- Literature Review Generator

- Thematic Literature Review

- How To Write A Literature Review

- Literature Review Outline Example

- Literature Review Example

- This part points to the applications or wider implications and interpretation scope of the work done.

- It tells the reader the benefits of the findings and how they can be applied.

- It helps the reader to understand the relevance of the paper to their lives, knowledge, and practices.

- This section is crucial to a literature review abstract.

- It is an essential aspect of the abstract and must be clearly stated.

- Unriddle is trusted by thousands of researchers and students, from the classroom to the boardroom.

- Unriddle generates an AI assistant on top of any document so you can quickly find, summarize and understand info. No more endless skimming.

- Unriddle understands the meaning behind your writing and automatically links you to relevant things you’ve read and written about in the past.

- Highlight text and Unriddle will show you the most relevant sources from your library using AI. Never lose a citation again.

- Generate text with AI autocomplete to improve and expand your writing, with all suggestions based on the context of what you're working on.

- Interact with documents via AI so you can quickly find and understand info.

- Then start writing in a new Note and Unriddle will show you relevant content from your library as you type.

- Get started by uploading a document .

- Or read on for the full rundown.

- Model: the machine learning model used to generate responses.

- Temperature: the amount of creative license you give to the AI.

- Max length: the maximum number of words generated in a response.

.jpg&optimizer=image&quality=80&width=280)

- Google Scholar Alternative

- Narrative Literature Review

- How To Write A Scientific Literature Review

- Literature Review Vs Annotated Bibliography

- Paper Digest Literature Review

- Literature Review Abstract Example

- Consensus Ai Tool

- Literature Review Introduction Example

- Review Of Related Literature

- Scientific Literature Review Example

- Dissertation Literature Review Example

- Thesis Literature Review

- Apa Literature Review Format

- Systematic Literature Review Example

- Ai Literature Review Generator

- Literature Review Topics

- Systematic Review Software

- Your abstract should be concise, at most 200 words, and focused.

- The abstract should be written for the audience of this journal: do not assume too much or too little background with the topic.

- Ensure that all of the information found in the abstract also can be found in the body of the paper.

- Ensure that the important information of the paper is found in the abstract.

- Avoid: using the first paragraph of the introduction as an abstract; citations in the abstract; acronyms (but if used, spell them out); referring to figures or tables from the body of the paper; use of the first person; use of words like “new” or “novel,” or phrases like “in this paper,” “we report,” or “will be discussed.”

- Scoping Review Vs Literature Review

- How To Do A Systematic Literature Review

- Literature Review Online Tool

- Methodology For Literature Review

- Best Literature Review Writing Service

- Methods Section Of Literature Review Example

- Scite Ai Assistant

- How To Structure Literature Review

- Chatgpt For Literature Review

- Sources Of Literature Review

Share this post

Ready to take the next big step for your research?

Join 500K+ researchers now

Related posts.

15 Best AI Literature Review Tools

Conducting a literature review? Make your research process easier with these literature review tools designed to enhance your review experience.

Complete Literature Review Example Guides

Stuck on how to write a literature review? These literature review example articles showcase approaches and help guide you in crafting your own.

A Beginner's Guide To Thematic Literature Review

Need help navigating thematic literature reviews? Look no further! This guide breaks down everything you need to know in simple steps.

10 Top-Notch Literature Review Generator Tools

Struggling to organize your literature review? These literature review generator tools can help streamline the process and improve work quality.

Detailed Comparison: Systematic Review vs Literature Review

Systematic review vs literature review. Discover the unique characteristics of each type of review and determine which suits your research needs.

Literature Review Outline Example For Inspiration

Stuck on how to structure your literature review? Get inspired by literature review outline examples that breaks down the key sections for you.

How To Write A Systematic Literature Review In 7 Simple Step

Follow these seven steps to conduct a systematic literature review and gather valuable insights for your research project. Start today!

How To Write A Literature Review In 9 Simple Steps

Need help on how to write a literature review? Follow these 9 simple steps to create a well-structured and comprehensive literature review.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

How do I Write a Literature Review?: #5 Writing the Review

- Step #1: Choosing a Topic

- Step #2: Finding Information

- Step #3: Evaluating Content

- Step #4: Synthesizing Content

- #5 Writing the Review

- Citing Your Sources

WRITING THE REVIEW

You've done the research and now you're ready to put your findings down on paper. When preparing to write your review, first consider how will you organize your review.

The actual review generally has 5 components:

Abstract - An abstract is a summary of your literature review. It is made up of the following parts:

- A contextual sentence about your motivation behind your research topic

- Your thesis statement

- A descriptive statement about the types of literature used in the review

- Summarize your findings

- Conclusion(s) based upon your findings

Introduction : Like a typical research paper introduction, provide the reader with a quick idea of the topic of the literature review:

- Define or identify the general topic, issue, or area of concern. This provides the reader with context for reviewing the literature.

- Identify related trends in what has already been published about the topic; or conflicts in theory, methodology, evidence, and conclusions; or gaps in research and scholarship; or a single problem or new perspective of immediate interest.

- Establish your reason (point of view) for reviewing the literature; explain the criteria to be used in analyzing and comparing literature and the organization of the review (sequence); and, when necessary, state why certain literature is or is not included (scope) -

Body : The body of a literature review contains your discussion of sources and can be organized in 3 ways-

- Chronological - by publication or by trend

- Thematic - organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time

- Methodical - the focusing factor usually does not have to do with the content of the material. Instead, it focuses on the "methods" of the literature's researcher or writer that you are reviewing

You may also want to include a section on "questions for further research" and discuss what questions the review has sparked about the topic/field or offer suggestions for future studies/examinations that build on your current findings.

Conclusion : In the conclusion, you should:

Conclude your paper by providing your reader with some perspective on the relationship between your literature review's specific topic and how it's related to it's parent discipline, scientific endeavor, or profession.

Bibliography : Since a literature review is composed of pieces of research, it is very important that your correctly cite the literature you are reviewing, both in the reviews body as well as in a bibliography/works cited. To learn more about different citation styles, visit the " Citing Your Sources " tab.

- Writing a Literature Review: Wesleyan University

- Literature Review: Edith Cowan University

- << Previous: Step #4: Synthesizing Content

- Next: Citing Your Sources >>

- Last Updated: Aug 22, 2023 1:35 PM

- URL: https://libguides.eastern.edu/literature_reviews

About the Library

- Collection Development

- Circulation Policies

- Mission Statement

- Staff Directory

Using the Library

- A to Z Journal List

- Library Catalog

- Research Guides

Interlibrary Services

- Research Help

Warner Memorial Library

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How To Write A Literature Review - A Complete Guide

Table of Contents

A literature review is much more than just another section in your research paper. It forms the very foundation of your research. It is a formal piece of writing where you analyze the existing theoretical framework, principles, and assumptions and use that as a base to shape your approach to the research question.

Curating and drafting a solid literature review section not only lends more credibility to your research paper but also makes your research tighter and better focused. But, writing literature reviews is a difficult task. It requires extensive reading, plus you have to consider market trends and technological and political changes, which tend to change in the blink of an eye.

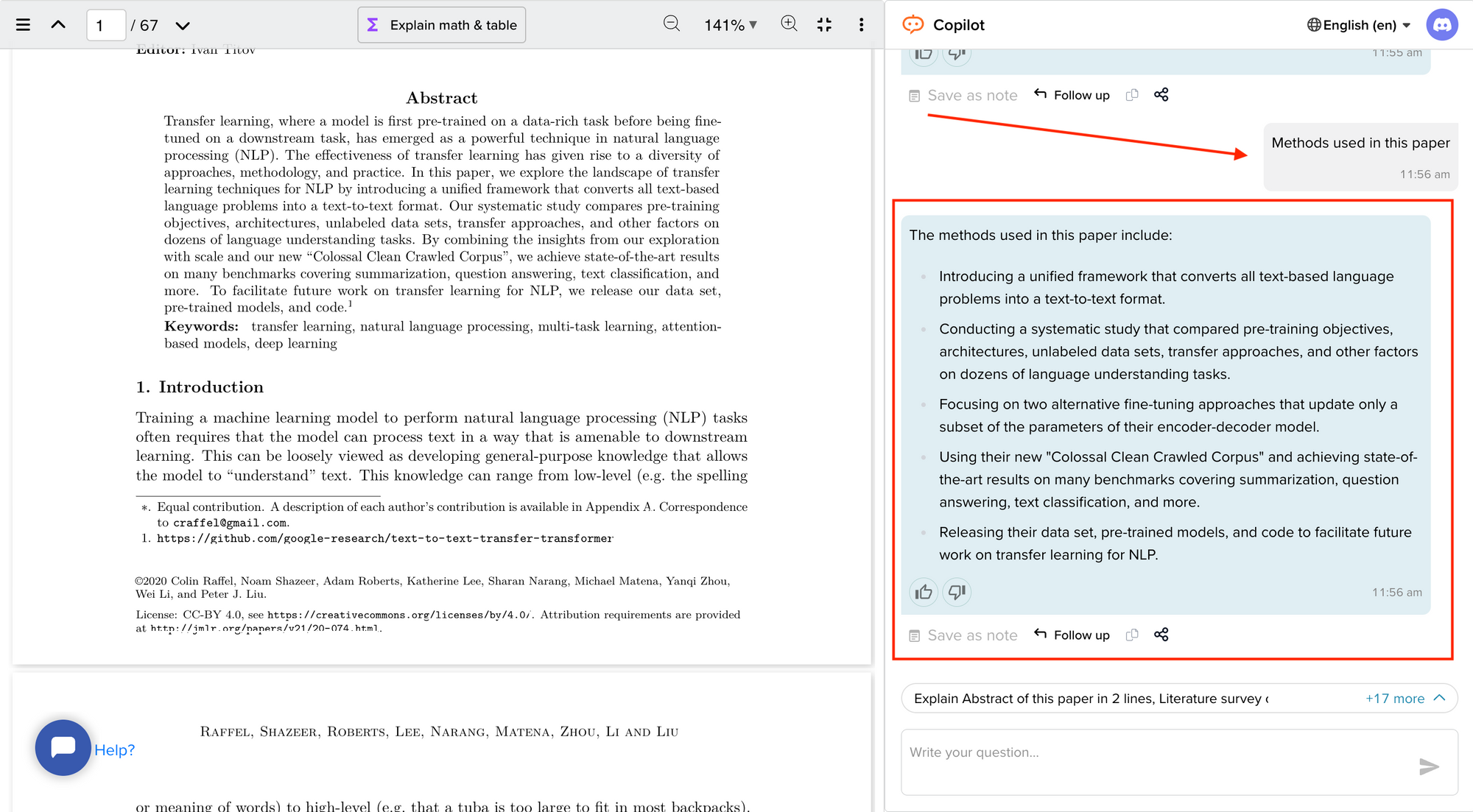

Now streamline your literature review process with the help of SciSpace Copilot. With this AI research assistant, you can efficiently synthesize and analyze a vast amount of information, identify key themes and trends, and uncover gaps in the existing research. Get real-time explanations, summaries, and answers to your questions for the paper you're reviewing, making navigating and understanding the complex literature landscape easier.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore everything from the definition of a literature review, its appropriate length, various types of literature reviews, and how to write one.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a collation of survey, research, critical evaluation, and assessment of the existing literature in a preferred domain.

Eminent researcher and academic Arlene Fink, in her book Conducting Research Literature Reviews , defines it as the following:

“A literature review surveys books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated.

Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have explored while researching a particular topic, and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within a larger field of study.”

Simply put, a literature review can be defined as a critical discussion of relevant pre-existing research around your research question and carving out a definitive place for your study in the existing body of knowledge. Literature reviews can be presented in multiple ways: a section of an article, the whole research paper itself, or a chapter of your thesis.

A literature review does function as a summary of sources, but it also allows you to analyze further, interpret, and examine the stated theories, methods, viewpoints, and, of course, the gaps in the existing content.

As an author, you can discuss and interpret the research question and its various aspects and debate your adopted methods to support the claim.

What is the purpose of a literature review?

A literature review is meant to help your readers understand the relevance of your research question and where it fits within the existing body of knowledge. As a researcher, you should use it to set the context, build your argument, and establish the need for your study.

What is the importance of a literature review?

The literature review is a critical part of research papers because it helps you:

- Gain an in-depth understanding of your research question and the surrounding area

- Convey that you have a thorough understanding of your research area and are up-to-date with the latest changes and advancements

- Establish how your research is connected or builds on the existing body of knowledge and how it could contribute to further research

- Elaborate on the validity and suitability of your theoretical framework and research methodology

- Identify and highlight gaps and shortcomings in the existing body of knowledge and how things need to change

- Convey to readers how your study is different or how it contributes to the research area

How long should a literature review be?

Ideally, the literature review should take up 15%-40% of the total length of your manuscript. So, if you have a 10,000-word research paper, the minimum word count could be 1500.

Your literature review format depends heavily on the kind of manuscript you are writing — an entire chapter in case of doctoral theses, a part of the introductory section in a research article, to a full-fledged review article that examines the previously published research on a topic.

Another determining factor is the type of research you are doing. The literature review section tends to be longer for secondary research projects than primary research projects.

What are the different types of literature reviews?

All literature reviews are not the same. There are a variety of possible approaches that you can take. It all depends on the type of research you are pursuing.

Here are the different types of literature reviews:

Argumentative review

It is called an argumentative review when you carefully present literature that only supports or counters a specific argument or premise to establish a viewpoint.

Integrative review

It is a type of literature review focused on building a comprehensive understanding of a topic by combining available theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence.

Methodological review

This approach delves into the ''how'' and the ''what" of the research question — you cannot look at the outcome in isolation; you should also review the methodology used.

Systematic review

This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research and collect, report, and analyze data from the studies included in the review.

Meta-analysis review

Meta-analysis uses statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects than those derived from the individual studies included within a review.

Historical review

Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, or phenomenon emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and identify future research's likely directions.

Theoretical Review

This form aims to examine the corpus of theory accumulated regarding an issue, concept, theory, and phenomenon. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories exist, the relationships between them, the degree the existing approaches have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested.

Scoping Review

The Scoping Review is often used at the beginning of an article, dissertation, or research proposal. It is conducted before the research to highlight gaps in the existing body of knowledge and explains why the project should be greenlit.

State-of-the-Art Review

The State-of-the-Art review is conducted periodically, focusing on the most recent research. It describes what is currently known, understood, or agreed upon regarding the research topic and highlights where there are still disagreements.

Can you use the first person in a literature review?

When writing literature reviews, you should avoid the usage of first-person pronouns. It means that instead of "I argue that" or "we argue that," the appropriate expression would be "this research paper argues that."

Do you need an abstract for a literature review?

Ideally, yes. It is always good to have a condensed summary that is self-contained and independent of the rest of your review. As for how to draft one, you can follow the same fundamental idea when preparing an abstract for a literature review. It should also include:

- The research topic and your motivation behind selecting it

- A one-sentence thesis statement

- An explanation of the kinds of literature featured in the review

- Summary of what you've learned

- Conclusions you drew from the literature you reviewed

- Potential implications and future scope for research

Here's an example of the abstract of a literature review

Is a literature review written in the past tense?

Yes, the literature review should ideally be written in the past tense. You should not use the present or future tense when writing one. The exceptions are when you have statements describing events that happened earlier than the literature you are reviewing or events that are currently occurring; then, you can use the past perfect or present perfect tenses.

How many sources for a literature review?

There are multiple approaches to deciding how many sources to include in a literature review section. The first approach would be to look level you are at as a researcher. For instance, a doctoral thesis might need 60+ sources. In contrast, you might only need to refer to 5-15 sources at the undergraduate level.

The second approach is based on the kind of literature review you are doing — whether it is merely a chapter of your paper or if it is a self-contained paper in itself. When it is just a chapter, sources should equal the total number of pages in your article's body. In the second scenario, you need at least three times as many sources as there are pages in your work.

Quick tips on how to write a literature review

To know how to write a literature review, you must clearly understand its impact and role in establishing your work as substantive research material.

You need to follow the below-mentioned steps, to write a literature review:

- Outline the purpose behind the literature review

- Search relevant literature

- Examine and assess the relevant resources

- Discover connections by drawing deep insights from the resources

- Structure planning to write a good literature review

1. Outline and identify the purpose of a literature review

As a first step on how to write a literature review, you must know what the research question or topic is and what shape you want your literature review to take. Ensure you understand the research topic inside out, or else seek clarifications. You must be able to the answer below questions before you start:

- How many sources do I need to include?

- What kind of sources should I analyze?

- How much should I critically evaluate each source?

- Should I summarize, synthesize or offer a critique of the sources?

- Do I need to include any background information or definitions?

Additionally, you should know that the narrower your research topic is, the swifter it will be for you to restrict the number of sources to be analyzed.

2. Search relevant literature

Dig deeper into search engines to discover what has already been published around your chosen topic. Make sure you thoroughly go through appropriate reference sources like books, reports, journal articles, government docs, and web-based resources.

You must prepare a list of keywords and their different variations. You can start your search from any library’s catalog, provided you are an active member of that institution. The exact keywords can be extended to widen your research over other databases and academic search engines like:

- Google Scholar

- Microsoft Academic

- Science.gov

Besides, it is not advisable to go through every resource word by word. Alternatively, what you can do is you can start by reading the abstract and then decide whether that source is relevant to your research or not.

Additionally, you must spend surplus time assessing the quality and relevance of resources. It would help if you tried preparing a list of citations to ensure that there lies no repetition of authors, publications, or articles in the literature review.

3. Examine and assess the sources

It is nearly impossible for you to go through every detail in the research article. So rather than trying to fetch every detail, you have to analyze and decide which research sources resemble closest and appear relevant to your chosen domain.

While analyzing the sources, you should look to find out answers to questions like:

- What question or problem has the author been describing and debating?

- What is the definition of critical aspects?

- How well the theories, approach, and methodology have been explained?

- Whether the research theory used some conventional or new innovative approach?

- How relevant are the key findings of the work?

- In what ways does it relate to other sources on the same topic?

- What challenges does this research paper pose to the existing theory

- What are the possible contributions or benefits it adds to the subject domain?

Be always mindful that you refer only to credible and authentic resources. It would be best if you always take references from different publications to validate your theory.

Always keep track of important information or data you can present in your literature review right from the beginning. It will help steer your path from any threats of plagiarism and also make it easier to curate an annotated bibliography or reference section.

4. Discover connections

At this stage, you must start deciding on the argument and structure of your literature review. To accomplish this, you must discover and identify the relations and connections between various resources while drafting your abstract.

A few aspects that you should be aware of while writing a literature review include:

- Rise to prominence: Theories and methods that have gained reputation and supporters over time.

- Constant scrutiny: Concepts or theories that repeatedly went under examination.

- Contradictions and conflicts: Theories, both the supporting and the contradictory ones, for the research topic.

- Knowledge gaps: What exactly does it fail to address, and how to bridge them with further research?

- Influential resources: Significant research projects available that have been upheld as milestones or perhaps, something that can modify the current trends

Once you join the dots between various past research works, it will be easier for you to draw a conclusion and identify your contribution to the existing knowledge base.

5. Structure planning to write a good literature review

There exist different ways towards planning and executing the structure of a literature review. The format of a literature review varies and depends upon the length of the research.

Like any other research paper, the literature review format must contain three sections: introduction, body, and conclusion. The goals and objectives of the research question determine what goes inside these three sections.

Nevertheless, a good literature review can be structured according to the chronological, thematic, methodological, or theoretical framework approach.

Literature review samples

1. Standalone

2. As a section of a research paper

How SciSpace Discover makes literature review a breeze?

SciSpace Discover is a one-stop solution to do an effective literature search and get barrier-free access to scientific knowledge. It is an excellent repository where you can find millions of only peer-reviewed articles and full-text PDF files. Here’s more on how you can use it:

Find the right information

Find what you want quickly and easily with comprehensive search filters that let you narrow down papers according to PDF availability, year of publishing, document type, and affiliated institution. Moreover, you can sort the results based on the publishing date, citation count, and relevance.

Assess credibility of papers quickly

When doing the literature review, it is critical to establish the quality of your sources. They form the foundation of your research. SciSpace Discover helps you assess the quality of a source by providing an overview of its references, citations, and performance metrics.

Get the complete picture in no time

SciSpace Discover’s personalized suggestion engine helps you stay on course and get the complete picture of the topic from one place. Every time you visit an article page, it provides you links to related papers. Besides that, it helps you understand what’s trending, who are the top authors, and who are the leading publishers on a topic.

Make referring sources super easy

To ensure you don't lose track of your sources, you must start noting down your references when doing the literature review. SciSpace Discover makes this step effortless. Click the 'cite' button on an article page, and you will receive preloaded citation text in multiple styles — all you've to do is copy-paste it into your manuscript.

Final tips on how to write a literature review

A massive chunk of time and effort is required to write a good literature review. But, if you go about it systematically, you'll be able to save a ton of time and build a solid foundation for your research.

We hope this guide has helped you answer several key questions you have about writing literature reviews.

Would you like to explore SciSpace Discover and kick off your literature search right away? You can get started here .

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. how to start a literature review.

• What questions do you want to answer?

• What sources do you need to answer these questions?

• What information do these sources contain?

• How can you use this information to answer your questions?

2. What to include in a literature review?

• A brief background of the problem or issue

• What has previously been done to address the problem or issue

• A description of what you will do in your project

• How this study will contribute to research on the subject

3. Why literature review is important?

The literature review is an important part of any research project because it allows the writer to look at previous studies on a topic and determine existing gaps in the literature, as well as what has already been done. It will also help them to choose the most appropriate method for their own study.

4. How to cite a literature review in APA format?

To cite a literature review in APA style, you need to provide the author's name, the title of the article, and the year of publication. For example: Patel, A. B., & Stokes, G. S. (2012). The relationship between personality and intelligence: A meta-analysis of longitudinal research. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(1), 16-21

5. What are the components of a literature review?

• A brief introduction to the topic, including its background and context. The introduction should also include a rationale for why the study is being conducted and what it will accomplish.

• A description of the methodologies used in the study. This can include information about data collection methods, sample size, and statistical analyses.

• A presentation of the findings in an organized format that helps readers follow along with the author's conclusions.

6. What are common errors in writing literature review?

• Not spending enough time to critically evaluate the relevance of resources, observations and conclusions.

• Totally relying on secondary data while ignoring primary data.

• Letting your personal bias seep into your interpretation of existing literature.

• No detailed explanation of the procedure to discover and identify an appropriate literature review.

7. What are the 5 C's of writing literature review?

• Cite - the sources you utilized and referenced in your research.

• Compare - existing arguments, hypotheses, methodologies, and conclusions found in the knowledge base.

• Contrast - the arguments, topics, methodologies, approaches, and disputes that may be found in the literature.

• Critique - the literature and describe the ideas and opinions you find more convincing and why.

• Connect - the various studies you reviewed in your research.

8. How many sources should a literature review have?

When it is just a chapter, sources should equal the total number of pages in your article's body. if it is a self-contained paper in itself, you need at least three times as many sources as there are pages in your work.

9. Can literature review have diagrams?

• To represent an abstract idea or concept

• To explain the steps of a process or procedure

• To help readers understand the relationships between different concepts

10. How old should sources be in a literature review?

Sources for a literature review should be as current as possible or not older than ten years. The only exception to this rule is if you are reviewing a historical topic and need to use older sources.

11. What are the types of literature review?

• Argumentative review

• Integrative review

• Methodological review

• Systematic review

• Meta-analysis review

• Historical review

• Theoretical review

• Scoping review

• State-of-the-Art review

12. Is a literature review mandatory?

Yes. Literature review is a mandatory part of any research project. It is a critical step in the process that allows you to establish the scope of your research, and provide a background for the rest of your work.

But before you go,

- Six Online Tools for Easy Literature Review

- Evaluating literature review: systematic vs. scoping reviews

- Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review

- Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Writing a Literature Review

Hundreds of original investigation research articles on health science topics are published each year. It is becoming harder and harder to keep on top of all new findings in a topic area and – more importantly – to work out how they all fit together to determine our current understanding of a topic. This is where literature reviews come in.

In this chapter, we explain what a literature review is and outline the stages involved in writing one. We also provide practical tips on how to communicate the results of a review of current literature on a topic in the format of a literature review.

7.1 What is a literature review?

Literature reviews provide a synthesis and evaluation of the existing literature on a particular topic with the aim of gaining a new, deeper understanding of the topic.

Published literature reviews are typically written by scientists who are experts in that particular area of science. Usually, they will be widely published as authors of their own original work, making them highly qualified to author a literature review.

However, literature reviews are still subject to peer review before being published. Literature reviews provide an important bridge between the expert scientific community and many other communities, such as science journalists, teachers, and medical and allied health professionals. When the most up-to-date knowledge reaches such audiences, it is more likely that this information will find its way to the general public. When this happens, – the ultimate good of science can be realised.

A literature review is structured differently from an original research article. It is developed based on themes, rather than stages of the scientific method.

In the article Ten simple rules for writing a literature review , Marco Pautasso explains the importance of literature reviews:

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications. For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively. Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests. Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read. For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way (Pautasso, 2013, para. 1).

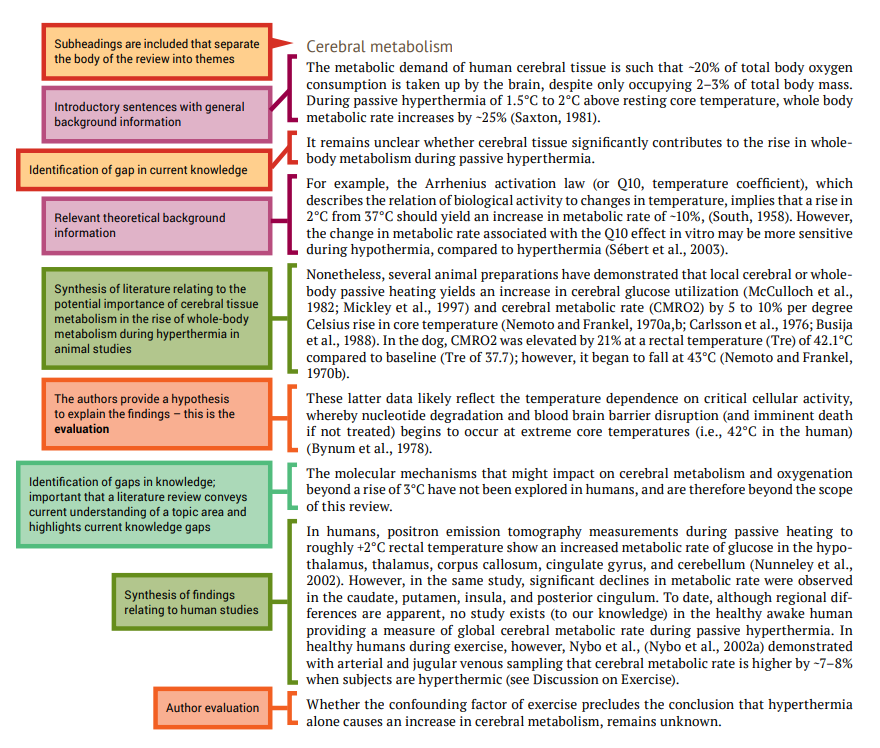

An example of a literature review is shown in Figure 7.1.

Video 7.1: What is a literature review? [2 mins, 11 secs]

Watch this video created by Steely Library at Northern Kentucky Library called ‘ What is a literature review? Note: Closed captions are available by clicking on the CC button below.

Examples of published literature reviews

- Strength training alone, exercise therapy alone, and exercise therapy with passive manual mobilisation each reduce pain and disability in people with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review

- Traveler’s diarrhea: a clinical review

- Cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric disorders: literature review and research recommendations for global mental health epidemiology

7.2 Steps of writing a literature review

Writing a literature review is a very challenging task. Figure 7.2 summarises the steps of writing a literature review. Depending on why you are writing your literature review, you may be given a topic area, or may choose a topic that particularly interests you or is related to a research project that you wish to undertake.

Chapter 6 provides instructions on finding scientific literature that would form the basis for your literature review.

Once you have your topic and have accessed the literature, the next stages (analysis, synthesis and evaluation) are challenging. Next, we look at these important cognitive skills student scientists will need to develop and employ to successfully write a literature review, and provide some guidance for navigating these stages.

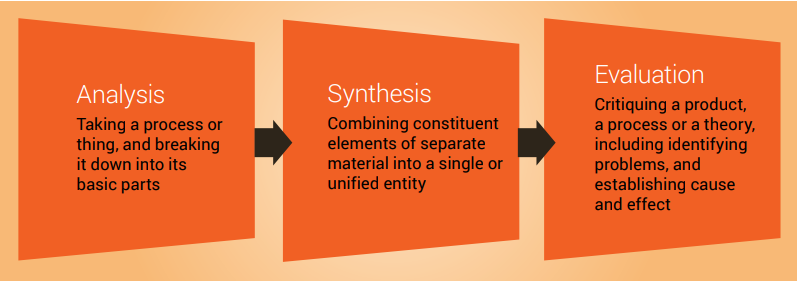

Analysis, synthesis and evaluation

Analysis, synthesis and evaluation are three essential skills required by scientists and you will need to develop these skills if you are to write a good literature review ( Figure 7.3 ). These important cognitive skills are discussed in more detail in Chapter 9.

The first step in writing a literature review is to analyse the original investigation research papers that you have gathered related to your topic.

Analysis requires examining the papers methodically and in detail, so you can understand and interpret aspects of the study described in each research article.

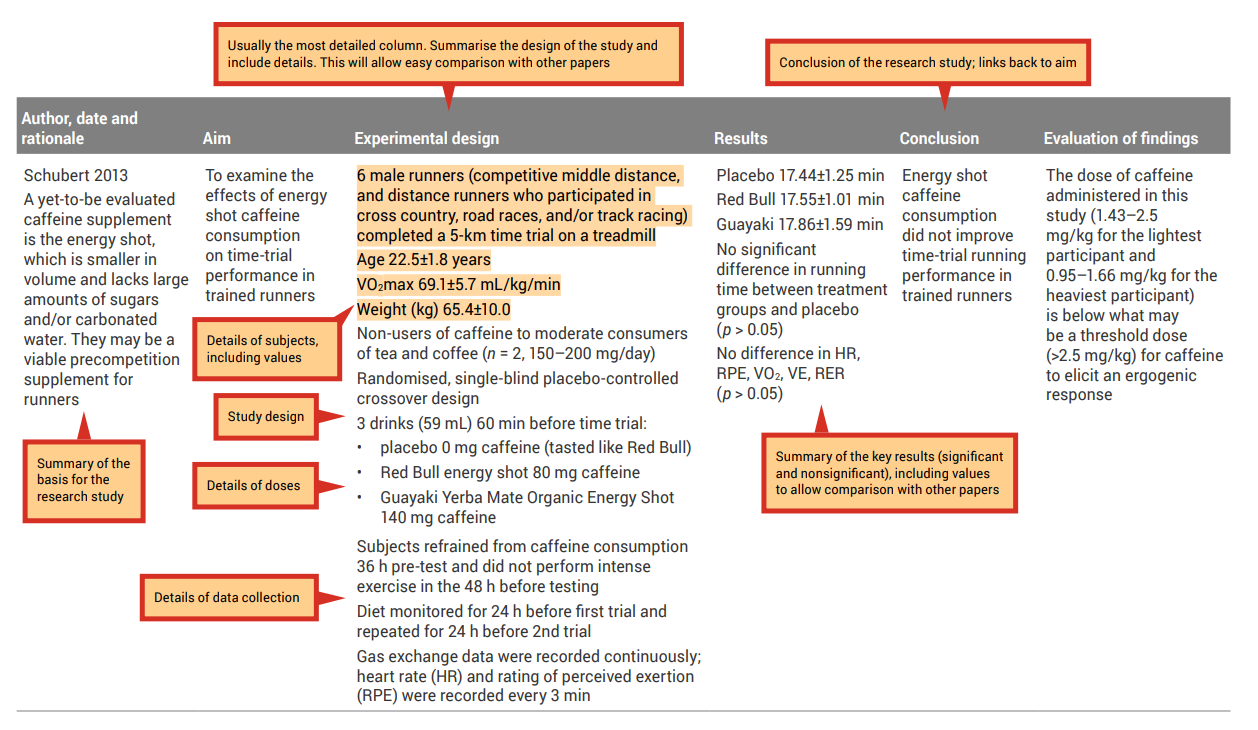

An analysis grid is a simple tool you can use to help with the careful examination and breakdown of each paper. This tool will allow you to create a concise summary of each research paper; see Table 7.1 for an example of an analysis grid. When filling in the grid, the aim is to draw out key aspects of each research paper. Use a different row for each paper, and a different column for each aspect of the paper ( Tables 7.2 and 7.3 show how completed analysis grid may look).

Before completing your own grid, look at these examples and note the types of information that have been included, as well as the level of detail. Completing an analysis grid with a sufficient level of detail will help you to complete the synthesis and evaluation stages effectively. This grid will allow you to more easily observe similarities and differences across the findings of the research papers and to identify possible explanations (e.g., differences in methodologies employed) for observed differences between the findings of different research papers.

Table 7.1: Example of an analysis grid

Table 7.3: Sample filled-in analysis grid for research article by Ping and colleagues

Source: Ping, WC, Keong, CC & Bandyopadhyay, A 2010, ‘Effects of acute supplementation of caffeine on cardiorespiratory responses during endurance running in a hot and humid climate’, Indian Journal of Medical Research, vol. 132, pp. 36–41. Used under a CC-BY-NC-SA licence.

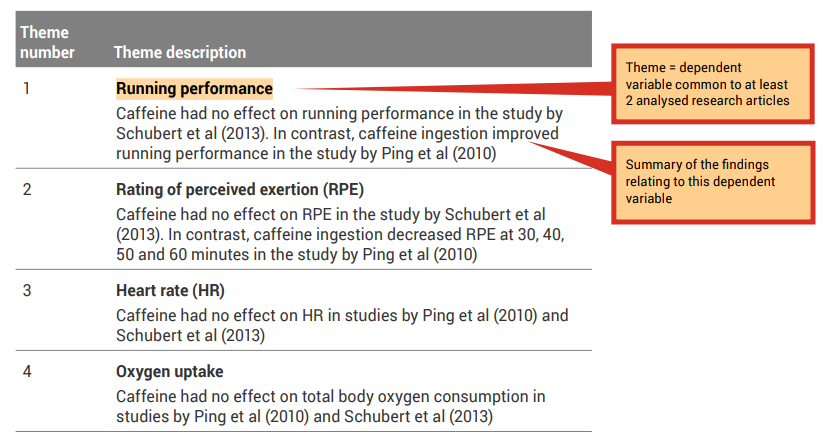

Step two of writing a literature review is synthesis.

Synthesis describes combining separate components or elements to form a connected whole.

You will use the results of your analysis to find themes to build your literature review around. Each of the themes identified will become a subheading within the body of your literature review.

A good place to start when identifying themes is with the dependent variables (results/findings) that were investigated in the research studies.

Because all of the research articles you are incorporating into your literature review are related to your topic, it is likely that they have similar study designs and have measured similar dependent variables. Review the ‘Results’ column of your analysis grid. You may like to collate the common themes in a synthesis grid (see, for example Table 7.4 ).

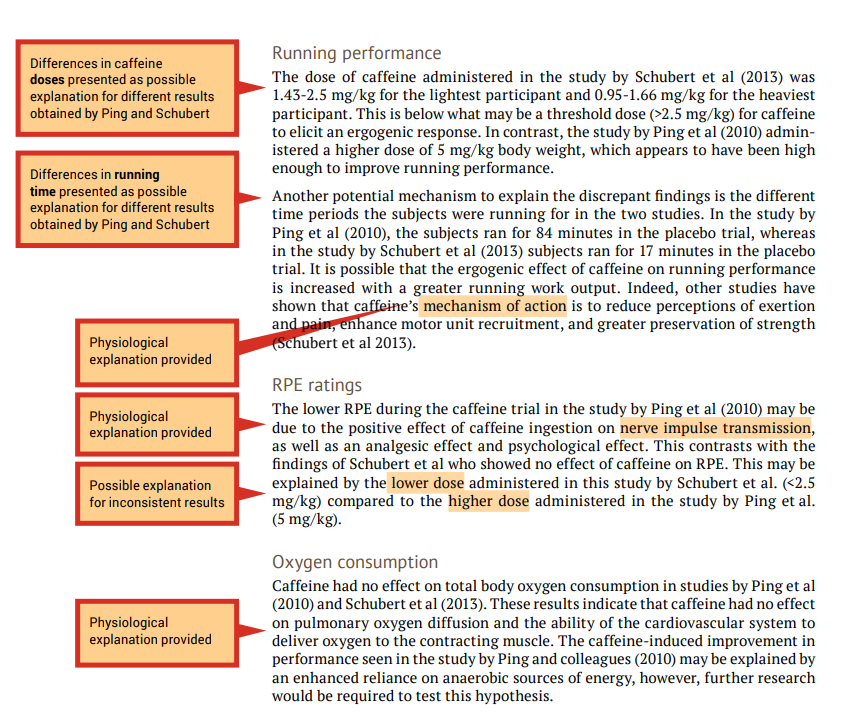

Step three of writing a literature review is evaluation, which can only be done after carefully analysing your research papers and synthesising the common themes (findings).

During the evaluation stage, you are making judgements on the themes presented in the research articles that you have read. This includes providing physiological explanations for the findings. It may be useful to refer to the discussion section of published original investigation research papers, or another literature review, where the authors may mention tested or hypothetical physiological mechanisms that may explain their findings.

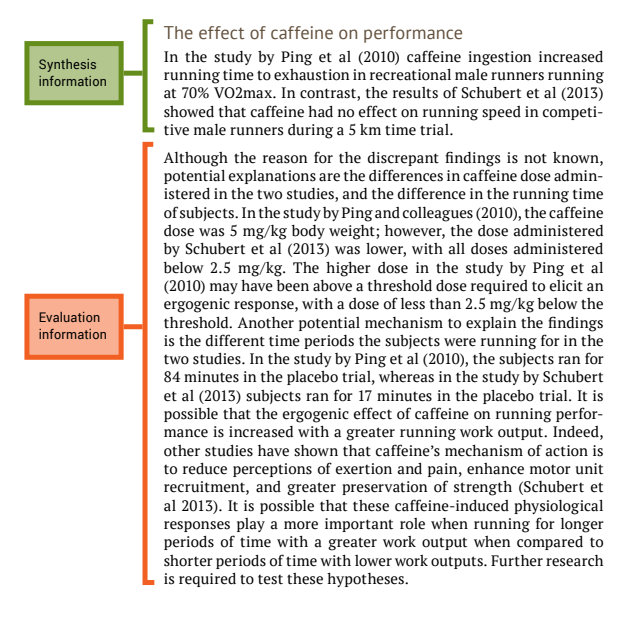

When the findings of the investigations related to a particular theme are inconsistent (e.g., one study shows that caffeine effects performance and another study shows that caffeine had no effect on performance) you should attempt to provide explanations of why the results differ, including physiological explanations. A good place to start is by comparing the methodologies to determine if there are any differences that may explain the differences in the findings (see the ‘Experimental design’ column of your analysis grid). An example of evaluation is shown in the examples that follow in this section, under ‘Running performance’ and ‘RPE ratings’.

When the findings of the papers related to a particular theme are consistent (e.g., caffeine had no effect on oxygen uptake in both studies) an evaluation should include an explanation of why the results are similar. Once again, include physiological explanations. It is still a good idea to compare methodologies as a background to the evaluation. An example of evaluation is shown in the following under ‘Oxygen consumption’.

7.3 Writing your literature review

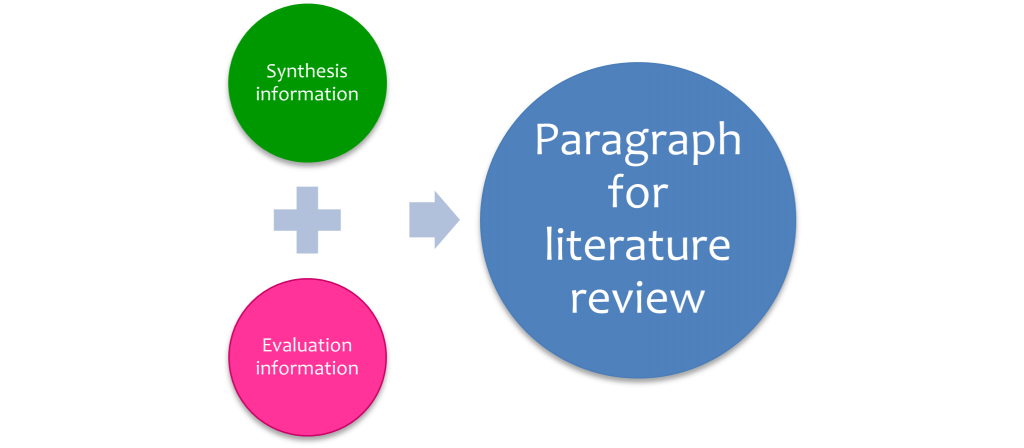

Once you have completed the analysis, and synthesis grids and written your evaluation of the research papers , you can combine synthesis and evaluation information to create a paragraph for a literature review ( Figure 7.4 ).

The following paragraphs are an example of combining the outcome of the synthesis and evaluation stages to produce a paragraph for a literature review.

Note that this is an example using only two papers – most literature reviews would be presenting information on many more papers than this ( (e.g., 106 papers in the review article by Bain and colleagues discussed later in this chapter). However, the same principle applies regardless of the number of papers reviewed.

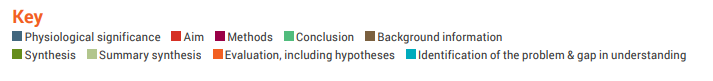

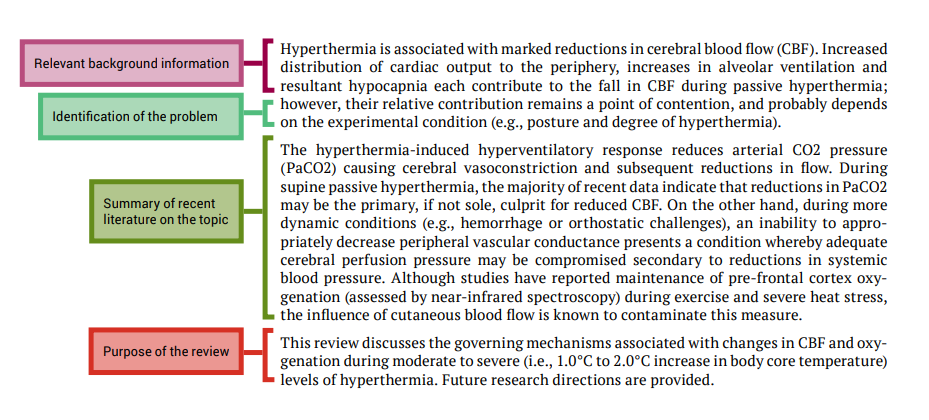

The next part of this chapter looks at the each section of a literature review and explains how to write them by referring to a review article that was published in Frontiers in Physiology and shown in Figure 7.1. Each section from the published article is annotated to highlight important features of the format of the review article, and identifies the synthesis and evaluation information.

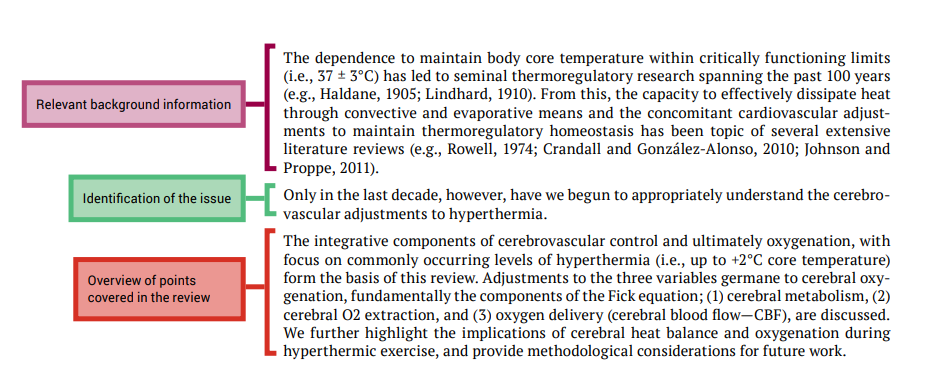

In the examination of each review article section we will point out examples of how the authors have presented certain information and where they display application of important cognitive processes; we will use the colour code shown below:

This should be one paragraph that accurately reflects the contents of the review article.

Introduction

The introduction should establish the context and importance of the review

Body of literature review

The reference section provides a list of the references that you cited in the body of your review article. The format will depend on the journal of publication as each journal has their own specific referencing format.

It is important to accurately cite references in research papers to acknowledge your sources and ensure credit is appropriately given to authors of work you have referred to. An accurate and comprehensive reference list also shows your readers that you are well-read in your topic area and are aware of the key papers that provide the context to your research.

It is important to keep track of your resources and to reference them consistently in the format required by the publication in which your work will appear. Most scientists will use reference management software to store details of all of the journal articles (and other sources) they use while writing their review article. This software also automates the process of adding in-text references and creating a reference list. In the review article by Bain et al. (2014) used as an example in this chapter, the reference list contains 106 items, so you can imagine how much help referencing software would be. Chapter 5 shows you how to use EndNote, one example of reference management software.

Click the drop down below to review the terms learned from this chapter.

Copyright note:

- The quotation from Pautasso, M 2013, ‘Ten simple rules for writing a literature review’, PLoS Computational Biology is use under a CC-BY licence.

- Content from the annotated article and tables are based on Schubert, MM, Astorino, TA & Azevedo, JJL 2013, ‘The effects of caffeinated ‘energy shots’ on time trial performance’, Nutrients, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 2062–2075 (used under a CC-BY 3.0 licence ) and P ing, WC, Keong , CC & Bandyopadhyay, A 2010, ‘Effects of acute supplementation of caffeine on cardiorespiratory responses during endurance running in a hot and humid climate’, Indian Journal of Medical Research, vol. 132, pp. 36–41 (used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence ).

Bain, A.R., Morrison, S.A., & Ainslie, P.N. (2014). Cerebral oxygenation and hyperthermia. Frontiers in Physiology, 5 , 92.

Pautasso, M. (2013). Ten simple rules for writing a literature review. PLoS Computational Biology, 9 (7), e1003149.

How To Do Science Copyright © 2022 by University of Southern Queensland is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Definition and Purpose of Abstracts

An abstract is a short summary of your (published or unpublished) research paper, usually about a paragraph (c. 6-7 sentences, 150-250 words) long. A well-written abstract serves multiple purposes:

- an abstract lets readers get the gist or essence of your paper or article quickly, in order to decide whether to read the full paper;

- an abstract prepares readers to follow the detailed information, analyses, and arguments in your full paper;

- and, later, an abstract helps readers remember key points from your paper.

It’s also worth remembering that search engines and bibliographic databases use abstracts, as well as the title, to identify key terms for indexing your published paper. So what you include in your abstract and in your title are crucial for helping other researchers find your paper or article.

If you are writing an abstract for a course paper, your professor may give you specific guidelines for what to include and how to organize your abstract. Similarly, academic journals often have specific requirements for abstracts. So in addition to following the advice on this page, you should be sure to look for and follow any guidelines from the course or journal you’re writing for.

The Contents of an Abstract

Abstracts contain most of the following kinds of information in brief form. The body of your paper will, of course, develop and explain these ideas much more fully. As you will see in the samples below, the proportion of your abstract that you devote to each kind of information—and the sequence of that information—will vary, depending on the nature and genre of the paper that you are summarizing in your abstract. And in some cases, some of this information is implied, rather than stated explicitly. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , which is widely used in the social sciences, gives specific guidelines for what to include in the abstract for different kinds of papers—for empirical studies, literature reviews or meta-analyses, theoretical papers, methodological papers, and case studies.

Here are the typical kinds of information found in most abstracts:

- the context or background information for your research; the general topic under study; the specific topic of your research

- the central questions or statement of the problem your research addresses

- what’s already known about this question, what previous research has done or shown

- the main reason(s) , the exigency, the rationale , the goals for your research—Why is it important to address these questions? Are you, for example, examining a new topic? Why is that topic worth examining? Are you filling a gap in previous research? Applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data? Resolving a dispute within the literature in your field? . . .

- your research and/or analytical methods

- your main findings , results , or arguments

- the significance or implications of your findings or arguments.

Your abstract should be intelligible on its own, without a reader’s having to read your entire paper. And in an abstract, you usually do not cite references—most of your abstract will describe what you have studied in your research and what you have found and what you argue in your paper. In the body of your paper, you will cite the specific literature that informs your research.

When to Write Your Abstract

Although you might be tempted to write your abstract first because it will appear as the very first part of your paper, it’s a good idea to wait to write your abstract until after you’ve drafted your full paper, so that you know what you’re summarizing.

What follows are some sample abstracts in published papers or articles, all written by faculty at UW-Madison who come from a variety of disciplines. We have annotated these samples to help you see the work that these authors are doing within their abstracts.

Choosing Verb Tenses within Your Abstract

The social science sample (Sample 1) below uses the present tense to describe general facts and interpretations that have been and are currently true, including the prevailing explanation for the social phenomenon under study. That abstract also uses the present tense to describe the methods, the findings, the arguments, and the implications of the findings from their new research study. The authors use the past tense to describe previous research.

The humanities sample (Sample 2) below uses the past tense to describe completed events in the past (the texts created in the pulp fiction industry in the 1970s and 80s) and uses the present tense to describe what is happening in those texts, to explain the significance or meaning of those texts, and to describe the arguments presented in the article.

The science samples (Samples 3 and 4) below use the past tense to describe what previous research studies have done and the research the authors have conducted, the methods they have followed, and what they have found. In their rationale or justification for their research (what remains to be done), they use the present tense. They also use the present tense to introduce their study (in Sample 3, “Here we report . . .”) and to explain the significance of their study (In Sample 3, This reprogramming . . . “provides a scalable cell source for. . .”).

Sample Abstract 1

From the social sciences.

Reporting new findings about the reasons for increasing economic homogamy among spouses

Gonalons-Pons, Pilar, and Christine R. Schwartz. “Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” Demography , vol. 54, no. 3, 2017, pp. 985-1005.

![how to write abstract literature review “The growing economic resemblance of spouses has contributed to rising inequality by increasing the number of couples in which there are two high- or two low-earning partners. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the topic under study (the “economic resemblance of spouses”). This sentence also implies the question underlying this research study: what are the various causes—and the interrelationships among them—for this trend?] The dominant explanation for this trend is increased assortative mating. Previous research has primarily relied on cross-sectional data and thus has been unable to disentangle changes in assortative mating from changes in the division of spouses’ paid labor—a potentially key mechanism given the dramatic rise in wives’ labor supply. [Annotation for the previous two sentences: These next two sentences explain what previous research has demonstrated. By pointing out the limitations in the methods that were used in previous studies, they also provide a rationale for new research.] We use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to decompose the increase in the correlation between spouses’ earnings and its contribution to inequality between 1970 and 2013 into parts due to (a) changes in assortative mating, and (b) changes in the division of paid labor. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The data, research and analytical methods used in this new study.] Contrary to what has often been assumed, the rise of economic homogamy and its contribution to inequality is largely attributable to changes in the division of paid labor rather than changes in sorting on earnings or earnings potential. Our findings indicate that the rise of economic homogamy cannot be explained by hypotheses centered on meeting and matching opportunities, and they show where in this process inequality is generated and where it is not.” (p. 985) [Annotation for the previous two sentences: The major findings from and implications and significance of this study.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-1.png)

Sample Abstract 2

From the humanities.

Analyzing underground pulp fiction publications in Tanzania, this article makes an argument about the cultural significance of those publications

Emily Callaci. “Street Textuality: Socialism, Masculinity, and Urban Belonging in Tanzania’s Pulp Fiction Publishing Industry, 1975-1985.” Comparative Studies in Society and History , vol. 59, no. 1, 2017, pp. 183-210.

![how to write abstract literature review “From the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s, a network of young urban migrant men created an underground pulp fiction publishing industry in the city of Dar es Salaam. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the context for this research and announces the topic under study.] As texts that were produced in the underground economy of a city whose trajectory was increasingly charted outside of formalized planning and investment, these novellas reveal more than their narrative content alone. These texts were active components in the urban social worlds of the young men who produced them. They reveal a mode of urbanism otherwise obscured by narratives of decolonization, in which urban belonging was constituted less by national citizenship than by the construction of social networks, economic connections, and the crafting of reputations. This article argues that pulp fiction novellas of socialist era Dar es Salaam are artifacts of emergent forms of male sociability and mobility. In printing fictional stories about urban life on pilfered paper and ink, and distributing their texts through informal channels, these writers not only described urban communities, reputations, and networks, but also actually created them.” (p. 210) [Annotation for the previous sentences: The remaining sentences in this abstract interweave other essential information for an abstract for this article. The implied research questions: What do these texts mean? What is their historical and cultural significance, produced at this time, in this location, by these authors? The argument and the significance of this analysis in microcosm: these texts “reveal a mode or urbanism otherwise obscured . . .”; and “This article argues that pulp fiction novellas. . . .” This section also implies what previous historical research has obscured. And through the details in its argumentative claims, this section of the abstract implies the kinds of methods the author has used to interpret the novellas and the concepts under study (e.g., male sociability and mobility, urban communities, reputations, network. . . ).]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-2.png)

Sample Abstract/Summary 3

From the sciences.

Reporting a new method for reprogramming adult mouse fibroblasts into induced cardiac progenitor cells

Lalit, Pratik A., Max R. Salick, Daryl O. Nelson, Jayne M. Squirrell, Christina M. Shafer, Neel G. Patel, Imaan Saeed, Eric G. Schmuck, Yogananda S. Markandeya, Rachel Wong, Martin R. Lea, Kevin W. Eliceiri, Timothy A. Hacker, Wendy C. Crone, Michael Kyba, Daniel J. Garry, Ron Stewart, James A. Thomson, Karen M. Downs, Gary E. Lyons, and Timothy J. Kamp. “Lineage Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Proliferative Induced Cardiac Progenitor Cells by Defined Factors.” Cell Stem Cell , vol. 18, 2016, pp. 354-367.