Ten reasons why unions are important

Today, working people in the UK are facing unprecedented attacks on their right to organise, including their right to strike – with the current UK government introducing the most repressive legislation in decades. A new anti-strike law undermines hard won workers’ rights and aims to silence those who challenge the UK government’s broken economic policies.

War on Want is proud to stand in solidarity with workers in the UK and around the world — many of whom face intimidation and retaliation for organising into trade unions.

There are so many reasons why unions are important — here are just ten of them:

1. Unity is strength

Unions enable workers to come together as a powerful, collective voice to communicate with management about their working terms and conditions – and to push for safe, fair and decent work.

Working people need the protection of a union now more than ever. Many employers around the world have tried to divide workers and cut through workers’ rights legislation by shifting the focus away from their own responsibilities towards their workers. Whether by arguing that ‘gig-economy’ workers are self-employed ‘contractors’ rather than employees; or by distancing themselves from the workers in Global South supply chains, who produce the products they profit from.

Global corporations and fashion brands are keen to point to the thousands of jobs they create. However, without ensuring the essential rights of workers are respected and maintained, this is not decent work.

Decent work is about the right to employment to begin with, and that employers should provide a living wage for the employee and the family. It should ensure workplace safety without discrimination and the right of employees to organise as trade unions. Anton Marcus , Joint Secretary of FTZ&GSEU in Sri Lanka

2. Better terms and conditions

Workers who join a trade union are more likely to have better terms and conditions than those who do not, because trade unions negotiate for their members through collective bargaining agreements and protect them from bad management practices.

All aspects of working life should be the subject of discussion and agreement between employers and employees under the protection of a trade union. Trained representatives of the union lead these negotiations on behalf of employees. Unions work constructively with progressive employers to ensure that company changes affecting employees are in the interest of both workers and employer.

3. More holiday

Unions won the right for workers to have paid holidays. The average trade union member in the UK gets over 25% more annual leave a year than a non-unionised worker.

4. Higher wages

You earn more in a unionised workplace. Trade union members in the UK earn on average 10% more than non-unionised members. This is the power of collective bargaining.

While many companies post record profits, workers in the UK are feeling the devastating effects of years of real-term pay decreases and cuts to vital public services. Amid a cost-of-living crisis that is dragging more and more people towards poverty, hundreds of thousands of unionised public sector workers have been left with no alternative but to go on strike.

The UK government should be getting around the table and having meaningful discussions with workers and trade unions to find solutions to the deepening in-work poverty people are facing. Instead, it is undermining the vital role of unions in representing and fighting for the rights of workers.

Strike action is always a last resort — no worker wants to go on strike and lose pay. But throughout history, union-organised strike action has been a crucial tactic for workers in securing fair pay and working conditions.

In 2017, MacDonald’s workers made history when they joined the Bakers, Food and Allied Workers’ Union (BFAWU) and went on strike — the McStrike — for the first time ever. McDonald’s makes billions every year, but it doesn’t pay its fair share of taxes – or its workers living wages. The McStrike industrial action won McDonald’s workers across the UK the biggest pay rise in over ten years.

5. Equal opportunities, and protection against discrimination

Unions fight for equal opportunities in the workplace. Trade unions have fought for laws that give rights to workers: the minimum wage, maximum working time, paid holidays, equal pay for work of equal value as well as anti-discrimination laws.

It is the trade union movement that is fighting back against the discriminatory and unjust practices of our broken economic system. In Sri Lanka, War on Want’s trade union partner FTZ-GSEU has been at the forefront of battling for workers for over 30 years. So-called ‘free-trade zones’ have eroded the rights of workers around the globe; and in Sri Lanka, as elsewhere, it is mainly women who are most affected by reduced regulations and weak worker protections.

Separately, women from across the world have joined together to speak out about the sexual harassment they have faced whilst working at McDonald’s. Workers in the USA have even taken strike action. In the UK, the BFAWU-led campaign has led to McDonald’s entering a legal agreement with the Equality and Human Rights Commission to protect workers from sexual harassment.

6. Better parental leave

Unions are responsible for securing and improving maternity, paternal and carer leave for millions of workers.

In the UK, unionised workplaces are much more likely to have maternity, paternal and carer leave policies in place which are more generous than the statutory minimum.

7. Security and stability

Trade union members are more likely to stay in their jobs for longer, on average five years more than non-unionised workers.

8. Health and safety

Unionised workplaces are safer workplaces. In the UK, there are 50% fewer accidents in unionised workplaces. Local safety representatives, appointed by trade union shops, deal with issues ranging from stress and mental health issues to hazardous substances, representing their colleagues’ health and safety interests to management.

9. Legal support

If you have a problem at work, unions can offer legal services and advice.

In situations such as disciplinary and grievance hearings, your union representative can give you expert advice, support and representation from start to finish. Unions have legal teams who will make sure you are treated fairly and won’t charge you legal fees. Your union will be there for you whether the problem is with employment contracts, harassment, redundancy, pensions or discrimination.

10. Having someone in your corner

As a union member you are part of something bigger – and have the support of the union when you need it.

Trade unions are part of an international movement. Global worker solidarity is crucial to ending the worst abuses and injustice working people face, and to push back against poverty, climate breakdown and inequality. War on Want regularly asks our affiliates from the UK trade union movement to stand in solidarity with other workers across the world in their own struggles to protect their livelihoods and right to organise.

Workers against poverty

War on Want believes that poverty is political. It is the result of decisions made by those who hold power — governments and corporations — and a broken economic system which generates increasing wealth and power for elites at the expense of the majority of people on this earth. Unions have been central to War on Want’s work throughout our history as they are crucial to the fight against global poverty. We know that around the world, organised workers achieve more collectively than they can as individuals.

The Covid-19 pandemic shone a light on those workplaces and sectors where poor pay and conditions had become almost normalised, where the gap between rich and poor has grown exponentially, and where wealth is rewarded while poverty is punished.

Here in the UK, it was the trade union movement, not the government, who fought for the furlough scheme which helped many workers to keep their heads above water. And in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, it was garment worker unions who fought for compensation for workers dismissed in factory closures when global fashion brands cancelled orders – and didn’t pay for work already completed – while continuing to make huge profits.

Our partnerships with workers’ associations and trade unions focus on building strong, representative and effective worker-led organisations that have the knowledge and skills to create and use opportunities to engage with government and employers to realise safe, decent work. War on Want will continue to work with our affiliates here in the UK and our partners representing and organising workers across the Global South.

First published on 12 Feb 2018, updated in Feb 2023.

More debt won't solve Sri Lanka's debt crisis

Secrets and Fries: McDonald’s £295 million tax dodge

Garment Workers: Paying the price of the pandemic

- Garment workers

- Poverty is political

- Trade deals

- Global Green New Deal

- Militarism and repression

- Take action

- Become a member

- Affiliate your trade union

- Sign up for emails

- Leave a gift in your will

- Fundraise for War on Want

Subscribe to Heddels

Don’t miss a single Heddels post. Sign up for our free newsletter below!

What Are Unions and Why Are They Important?

What is a labor union and when were they first formed?

Dispatch riders waiting outside the TUC headquarters in 1926, UK. Image via TUC

Union formation really began to pick up in the United Kingdom around the time of the Industrial Revolution (1760-1840), when new factories popped up swiftly and had little regard for the conditions its employees had to endure. Workers fought back and settled many disputes, giving rise to “combinations” of colleagues protecting their rights.

Most early unions were on behalf of those in textile industries, as well as mechanics and blacksmiths, and although they laid the groundwork for organizations to continue to improve the lives of workers across the world, it’s worth remembering that they certainly weren’t inclusive of everyone. Despite the National Labor Union’s attempts to insist that it didn’t discriminate against “race or nationality” in 1869, the organization continually failed to fight hard enough for the rights of African-Americans and women, so in the same year, the Colored National Labor Union was formed.

Like this? Read these:

Incense 101: History and Products

Home Grows – How to Garden New Life From Throwaways

What are unions like today.

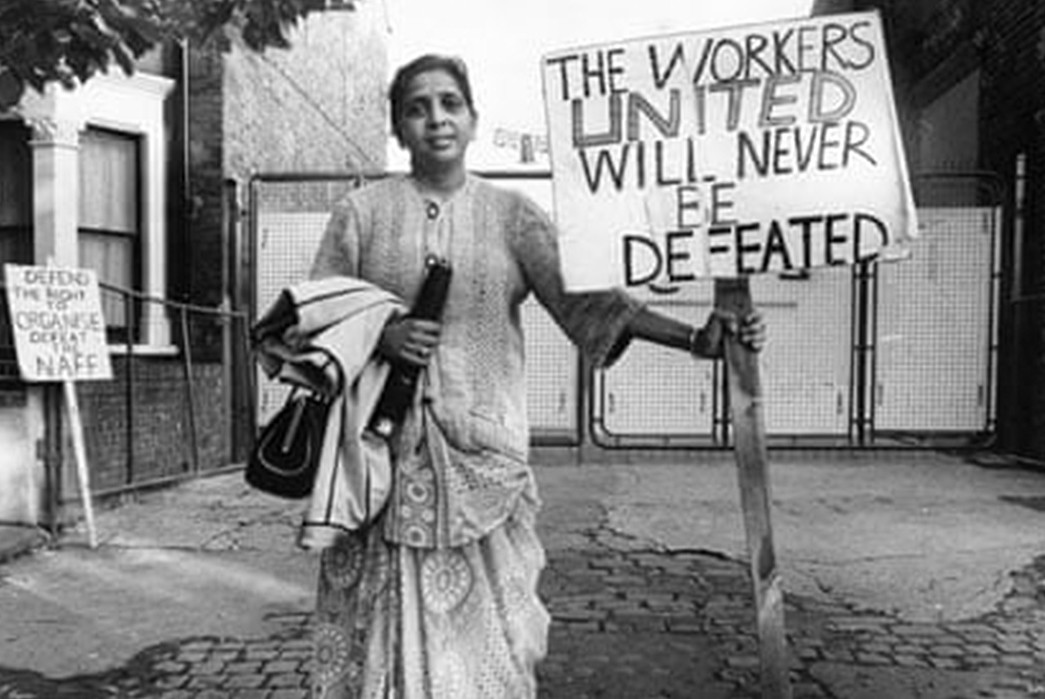

A woman strikes at the Grunwick film processing plant in London, 1976. Image via The Guardian

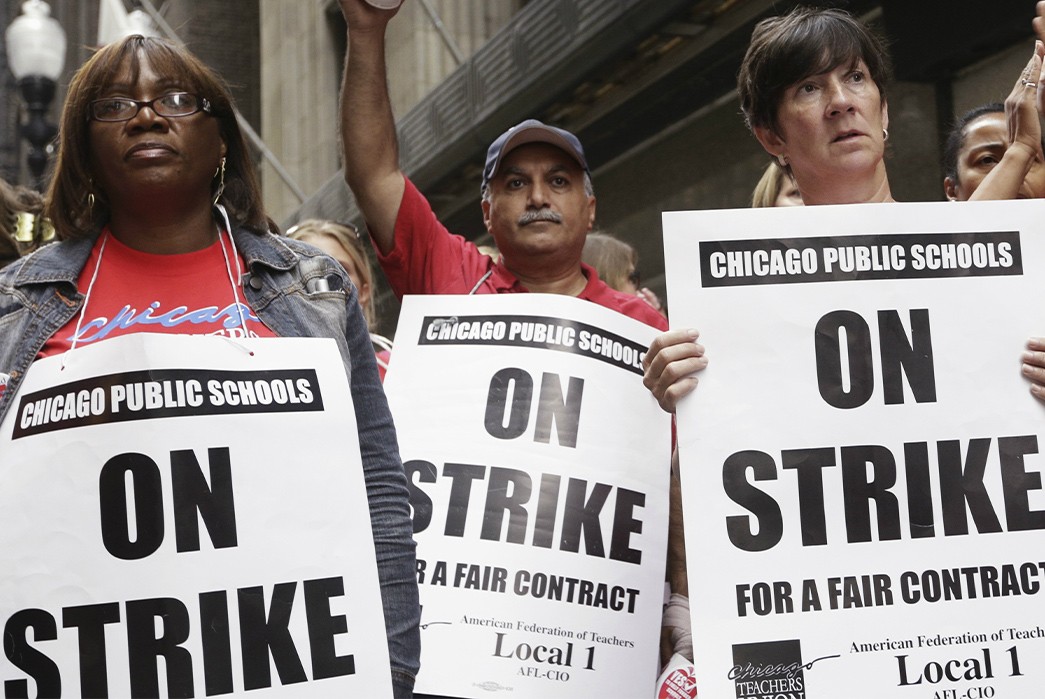

Unionized teachers on strike in Chicago in 2019. Image via Quartz.

At this point, it’s worth noting that laws surrounding unions vary drastically between different countries, depending on its history and politics.

What are the plus (and minus) points of unions?

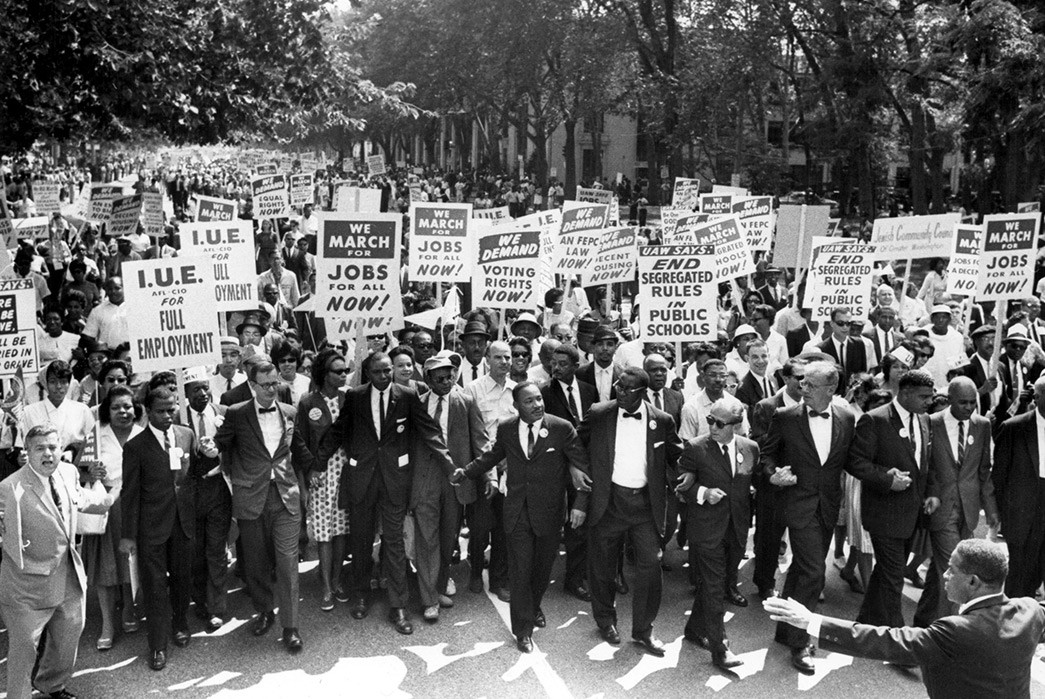

Martin Luther King Jr. and Joachim Prinz at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. Image via AFL-CIO

How does the “right to work” relate to labor unions in the United States?

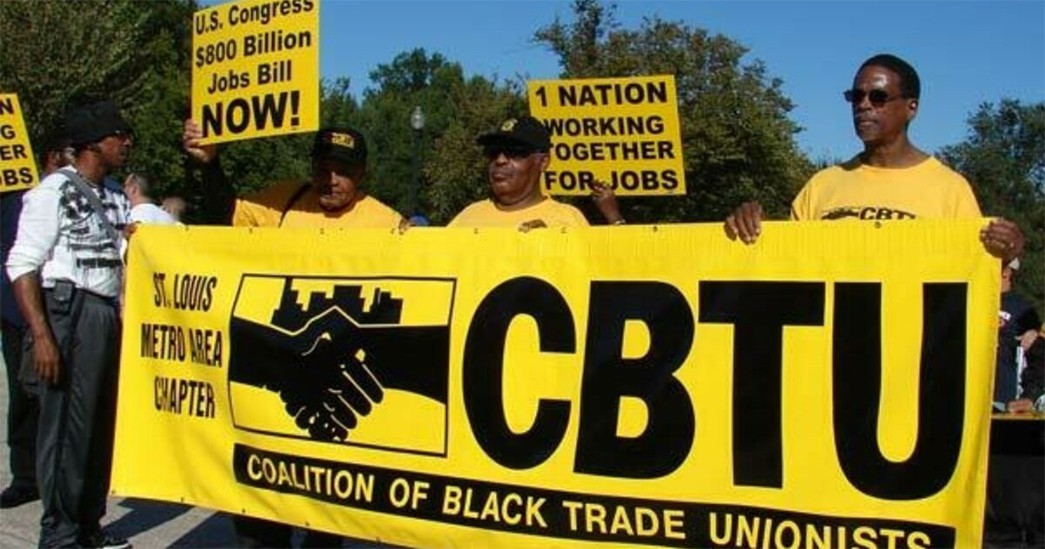

Campaigners from the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists in 2017. Image via In These Times

The general gist is that it entitles workers to be employed in ‘unionized’ workplaces (what’s called a ‘closed shop’) without joining a union. They can also leave a union at any time without having to fear losing their job, as was once the case. As well, even if an employee isn’t a union member, the right-to-work state law allows them to still access the benefits that the organizations offer, only they’ll likely be required to pay a fee for certain services.

Women in Bangladesh campaign for better working conditions with a representative from the labor rights organization Solidarity Centre. Image via Solidarity Centre

In the region, labor unions have become so key to the improvement of working conditions, pay, and job security that their representation can often be the difference between life and death.

Previous Article

Sage de cret’s khaki field jacket flaunts corduory, nylon, and terry cloth, next article, square trade’s incense cones are hand-dipped in richmond, va.

Related Articles

Home — Essay Samples — Life — Labor Union — History, Functions, and Future of Labor Unions

History, Functions, and Future of Labor Unions

- Categories: Labor Union

About this sample

Words: 554 |

Published: Jan 30, 2024

Words: 554 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

History of labor unions, functions and benefits of labor unions, criticisms and controversies surrounding labor unions, current challenges and future of labor unions, major milestones in the labor union movement, protection of workers' rights, advocacy for worker-friendly policies.

- Johnston, R. M. (2012). The history of the labor movement in the United States. Princeton University Press.

- Greenhouse, S. (2014). The big squeeze: Tough times for the American worker. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

- Hacker, J. S., & Pierson, P. (2015). American amnesia: How the war on government led us to forget what made America prosper. Simon & Schuster.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1579 words

2 pages / 808 words

6 pages / 2883 words

2 pages / 1019 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Labor Union

Sweatshop labor, also known as slave labor, is a prevalent issue in many developing countries where workers are exploited for low wages and subjected to harsh working conditions. This essay will examine a case study of a [...]

In his essay Panopticism, Michel Foucault discusses power and discipline, the manipulation there of, and their effect on society over time. He also discusses Jeremy Benthams Panopticon and other disciplinary models. However, [...]

The degree in finance or business is a condition for getting jobs in the financial industry, but what if you don't acquire one , and really want to work in this field? While it is more difficult for someone with a non-financial [...]

I strongly agree with the statement above that people work more productively in teamwork than individually. For my part, through cooperation in teamwork, we can not only divide our work and emphasize specialization to achieve [...]

In the case that the general evaluation, development, as well as, management of a patient’s care requires highly skilled services, then there is the need for the involvement of both technical and on the other hand professional [...]

Agriculture accounts for 17.5% of India’s GDP and about half of the total employment (2015-16). Two-thirds of India’s population depends on agriculture and related activities for livelihoods. Indian government plays a vital [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Competition

- Inequality & Mobility

- Tax & Macroeconomics

- Value Added

- Elevating Research

- Connect with an Expert

- In the Media

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

Connect with us

- Washington Center for Equitable Growth

- 740 15th St. NW 8th Floor

- Washington, D.C. 20005

- Phone: 202.545.6002

Factsheet: How strong unions can restore workers’ bargaining power

May 1, 2020.

Bargaining Power

Job Mobility

Minimum Wage

Unions in the United States have long been one of the most powerful institutions through which workers achieved higher pay and better working conditions. In the middle decades of the 20th century, a strong labor movement empowered workers and helped them secure many of the rights and protections that now are also part of many nonunionized workers’ nonwage benefits, including the expansion of healthcare, access to family leave, the minimum wage, and work-free weekends, just to name a few.

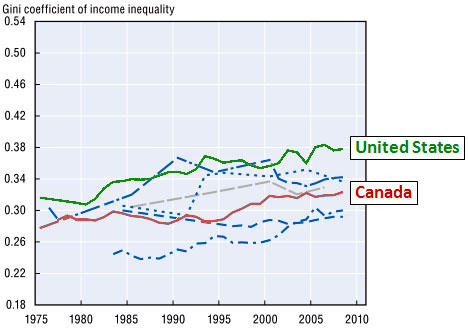

But a decades-long decline of unions has weakened workers’ ability to fight for a fairer workplace. About 10 percent workers are union members today, compared to 35 percent of the U.S. workforce in the mid-1950s. Over the past 40 years, the power of organized labor has declined alongside a steep rise in income inequality, the erosion of labor standards, and employers’ ability to dictate and suppress wages.

Yet unions still play an important role in shaping U.S. labor market outcomes, helping both union and nonunion members share in the economic value they create. This factsheet details those outcomes, including:

- Strong unions benefit both union and nonunion members.

- A small share of workers are part of a union today, but many want to belong to one.

- Strong unions can counteract employers’ wage-setting power.

- Strikes remain a powerful way for workers to achieve fair wages and better working conditions.

Before examining each of these in turn, however, it’s important to look briefly at how the steady decline in the power of unions since the 1970s is one of the most important causes behind the rise of income inequality in the United States.

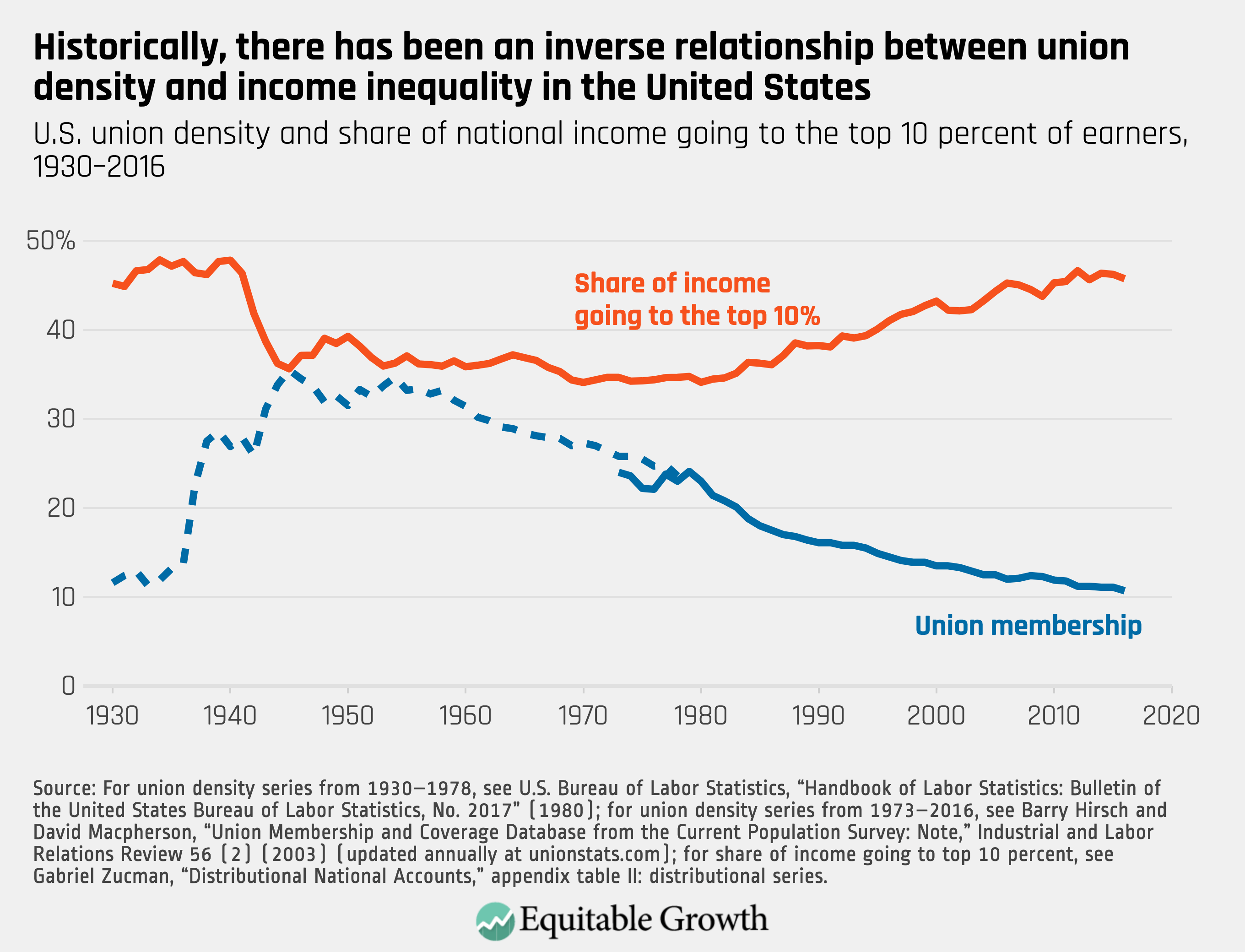

Rising U.S. income inequality amid declining union membership

At least since 1936, there has been a strong inverse relationship between union membership and income inequality. More than just a story of correlation, research shows that from 1940 to 1970—the decades when U.S. union density was at its highest—organized labor represented a greater share of workers of color and workers with lower levels of education, raising their wages and narrowing the gap between incomes at the top and the bottom of the income ladder. As membership rates declined and the composition of unions changed, however, the equalizing effect of organized labor became less powerful. (See Figure 1.)

This research on declining union membership challenges an influential explanation of why income inequality has risen sharply since the 1970s. The theory of skills-biased technological change proposes that workplace innovations raised employers’ demand for workers with higher levels of education, leaving behind those without a college degree. According to this theory, highly skilled workers’ improved labor market standing drives them to exit unions because they can obtain higher wages without collective bargaining.

Yet the opposite happened. Unions now represent workers with higher levels of education , and in the past two decades, income inequality has grown most between workers with the same level of education, with women and black workers with higher education degrees experiencing greater pay gaps.

Strong unions benefit all workers

The first set of facts about the importance of unions is that they benefit all workers. Union members have higher wages than their nonunionized peers—what researchers call the union wage premium —but organized labor helps create conditions that make all workers better off. By leveraging the possibility of unionizing, workers overall are in a better bargaining position to negotiate for higher pay and better working conditions.

More generally, strong unions are able to set job-quality standards that nonunion businesses have to meet in order to compete for workers. Known as the spillover effect , this mechanism helps explain why:

- Low- and middle-waged workers experienced important pay and benefits gains during the height of the labor movement in the middle of the 20th century.

- Residents of states with greater unionization rates are more likely to have access to health insurance.

- Average nonunion wages are higher in highly unionized industries.

Strong unions also allow organized labor to institutionalize norms of equity and fair pay . Even though the majority of union members were white and male during the height of the labor movement, organized labor strongly supported redistributive public policies that contributed to narrowing racial and gender pay gaps. Research shows, for example, that collective bargaining’s positive effect on earnings is particularly strong for black and Hispanic workers, helping reduce wage inequality. Likewise, women who are part of a union experience smaller gender wage gaps than their nonunionized peers.

A small share of workers are part of a union today, but many want to belong to one

The second set of facts show that workers are eager to join unions. U.S. labor law and a business environment antagonistic to organized labor prevent many workers from joining a union, yet public attitudes toward the U.S. labor movement have become increasingly positive over the past 30 years. A 2018 study found, for example, that 48 percent of nonunion workers would vote to join a union if they had the opportunity to do so. This number represents an important increase with respect to similar surveys conducted in 1977 and 1995, when only a third of respondents answered they would.

This research also shows that the ability to bargain collectively is very important to workers. Respondents to surveys asking why they wanted to become part of a union answered that the legal right to negotiate wages, benefits, and working conditions would significantly raise the likelihood of them joining a union. Workers were also enthusiastic about the prospect of joining labor organizations that allowed them to access unemployment benefits, as well as portable health insurance and retirement savings coverage.

Strong unions can counteract employers’ wage-setting power

The third set of facts demonstrates why unions can offset employers’ wage-setting power. The decades-long decline in union density has limited workers’ ability to push back against what economists call monopsony power : firms’ ability to use their market power to dictate and suppress earnings. Challenging traditional economic thinking on the wage-setting process, new sources of data have enabled researchers to show that labor markets are often uncompetitive, with wide-ranging factors such as corporate concentration , the widespread use of noncompete agreements , and the declining value of the federal minimum wage making it more difficult to move easily between jobs and, in turn, increasing employers’ power vis-à-vis workers.

Through an exhaustive analysis of the existing literature, researchers find evidence that monopsonistic labor markets are widespread, leading to important markdowns in wages for many workers. Using data from the hiring website CareerBuilder.com, for example, empirical research shows that going from a more competitive local labor market to a more concentrated one was associated with a 17 percent decline in the wages that employers posted on the website.

Unions can counteract monopsony power by limiting firms’ ability to extract “rents” from workers, where rents are defined as employers’ capacity to pay workers less than the value of what they produce. To do so, however, unions need the support of legislation that protects the right to organize, enforcement of regulation that prevents workplace abuses, and policies that allow collective action such as strikes.

Strikes remain a powerful way for workers to achieve fair wages and better working conditions

The fourth set of facts shows why the right to strike remains important. By striking, workers are able to use their labor as leverage and demand higher pay, better working conditions, and protest unfair practices by employers. That strikes are now much less frequent, successful, and popular than during the height of the labor movement has therefore weakened unions’ ability to counterbalance the power of employers.

Yet strikes keep playing an important role in workers’ struggle for a fairer workplace. There has been a significant rise in work stoppages since 2018, and the evidence shows that strikes can continue to be successful tools for the U.S. labor movement, particularly when organizers are able to build up goodwill though political education.

When studying the large-scale walkouts by public schools in 2018, for example, economists found that parents who had firsthand exposure to these strikes were more likely to support and join organized labor. The researchers found that strikes improved attitudes toward unions because educators were able to both leverage school staffing shortages and effectively communicate the worthiness of their demands, convincing parents of the public goods that collective action generates for their children and communities.

How to restore workers’ bargaining power

Unions remain important to all workers, as our sets of facts above detail, but in order to foster broadly shared economic growth, both unions and existing labor law need to adapt to the changing nature of work. During the past 40 years, the erosion of U.S. labor standards and changes in the way firms structure their businesses has made it harder for workers to join unions and bargain collectively.

Rulings by the U.S. Supreme Court have limited the ability of public-sector unions to collect dues, as well as made it more difficult for workers overall to band together and sue their employers for workplace misconduct. Likewise, businesses’ shift away from directly employing workers and toward contracting—a phenomenon researchers call the fissuring of the workplace —hurt workers’ career-advancement opportunities and earnings, as well as unions’ ability to counteract the power of employers.

Because of these new challenges, unions need to advocate for an updated vision for U.S. labor policy. Through their “ Clean Slate Agenda ,” Sharon Block and Benjamin Sachs of Harvard Law School developed such a framework, creating a series of proposals for structural legal changes that would protect workers and give them the ability to countervail employers’ power. Their recommendations include:

- Sectoral collective bargaining that enables unions to negotiate with industries rather than individual firms, increasing organized labor’s power to lift wages, set industrywide standards, and reach agreements that benefit a greater number of workers

- Laws that expand and protect workers’ right to engage in collective action, including the creation of funds that allow workers to engage in strikes or walkouts without jeopardizing their financial security

- An inclusive labor law reform that places the need to address gender, racial, and ethnic inequities at its center by extending protections to domestic, incarcerated, and undocumented workers, as well as expanding rights and protections for independent contractors

Other proposals include:

- The creation of labor market institutions such as wage boards, which set minimum pay standards by industry and occupation, and lead to wage gains for those at the bottom and middle of the income distribution

- Passing legislation such as the PRO Act , which would make it easier for workers to organize into unions, and would also curtail employers’ ability to misclassify workers as independent contractors, who do not have the right to unionize under federal U.S. law

These measures would expand workers’ rights and allow unions to balance power in the labor market, ensuring that the economic gains they create are broadly shared.

Aligning U.S. labor law with worker preferences for labor representation

February 18, 2020

‘Clean slate for worker power’ promotes a fair and inclusive U.S. economy

January 29, 2020

A first-time meta-analysis of monopsony demonstrates its breadth across labor markets

February 5, 2020

Factsheet: The PRO Act addresses income inequality by boosting the organizing power of U.S. workers

February 6, 2020

What kind of labor organizations do U.S. workers want?

August 28, 2019

First Jobs Day report since the onset of the coronavirus recession exposes a U.S. labor market in crisis

April 3, 2020

Explore the Equitable Growth network of experts around the country and get answers to today's most pressing questions!

U.S. Department of the Treasury

Labor unions and the u.s. economy.

By Laura Feiveson, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Microeconomics

Today, the Treasury Department released a first-of-its-kind report on labor unions, highlighting the evidence that unions serve to strengthen the middle class and grow the economy at large. Over the last half century, middle-class households have experienced stagnating wages, rising income volatility, and reduced intergenerational mobility, even as the economy as a whole has prospered. Unions can improve the well-being of middle-class workers in ways that directly combat these negative trends. Pro-union policy can make a real difference to middle-class households by raising their incomes, improving their work environments, and boosting their job satisfaction. In doing so, unions can help to make the economy more equitable and robust.

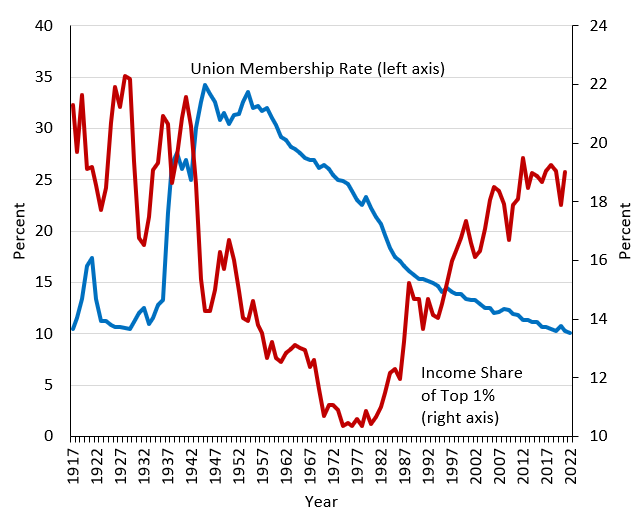

Over the last century, union membership rates and income inequality have diverged, as shown in Figure 1. Union membership peaked in the 1950s at one-third of the workforce. At that time, despite pervasive racial and gender discrimination, overall income inequality was close to its lowest level since its peak before the Great Depression, and was continuing to fall. Over the subsequent decades, union membership steadily declined, while income inequality began to steadily rise after a trough in the 1970s. In 2022, union membership plateaued at 10 percent of workers while the top one percent of income earners earned almost 20 percent of total income.

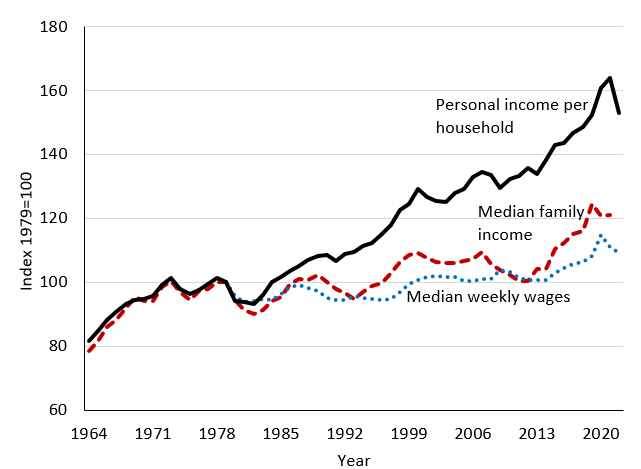

Figure 1: Union Membership and Inequality

While the overall U.S. economy has grown over the past few decades, the rise in inequality can be a proxy for the experience of many middle-class households. The income of the median family rose only 0.6 percent per year, in contrast to average personal income per household which rose 1.1 percent per year, as seen in Figure 2. And, notably, other markers of middle-class stability have deteriorated since the 1970s. Income has become more volatile, [1] the amount of time spent on vacation has fallen, [2] and middle-class Americans are less prepared for retirement. [3] Intergenerational mobility has declined—90 percent of children born in the 1940s earned more than their parents did at age 30, while only half of children born in the mid-1980s did the same. [4]

Figure 2: Income and Wage Growth since the 1960s

So, how could unions help? Treasury’s report shows that unions have the potential to address some of these negative trends by raising middle-class wages, improving work environments, and promoting demographic equality. Of course, unions should not be the only solution to these structural trends. But the evidence below and in the report suggests that unions can be useful in building the economy from the middle out.

Wages

One of the most oft-cited benefits of unions is the so-called “union wage premium”—the amount that union members make above and beyond non-members. While simple comparisons of the wages of union workers and nonunion workers find that union workers typically make about 20 percent more than nonunion workers, [5] economists turn to other types of analysis to capture causal effects of unions on wages. The first approach controls for many worker and occupation characteristics with the goal of comparing the wages earned by two similar workers that differ only in their union status. The other empirical approach is “regression discontinuity analysis,” which compares the wages in workplaces which just barely passed a vote to unionize against wages in workplaces that barely failed to pass the unionization vote. All in all, the evidence from these two approaches points to a union wage premium of around 10 to 15 percent, with larger effects for longer-tenured workers. [6]

Work environments

Worker wellbeing is greatly affected by non-wage benefits. Some benefits, such as healthcare benefits and retirement benefits, are a part of the compensation package and have substantial monetary value. Other features of the work environment, like flexible scheduling or workplace safety regulations, may not have direct monetary value but could still be highly valued by workers. For example, one study estimated that the average worker is willing to give up 20 percent of wages to avoid having their schedule frequently changed by their employer on short notice. [7] Another study, co-authored by Secretary Yellen, found that 80 percent of people who like their jobs cite a non-wage reason as the primary cause of their satisfaction and, conversely, 80 percent of people who dislike their jobs cite non-wage reasons to explain their dissatisfaction. [8]

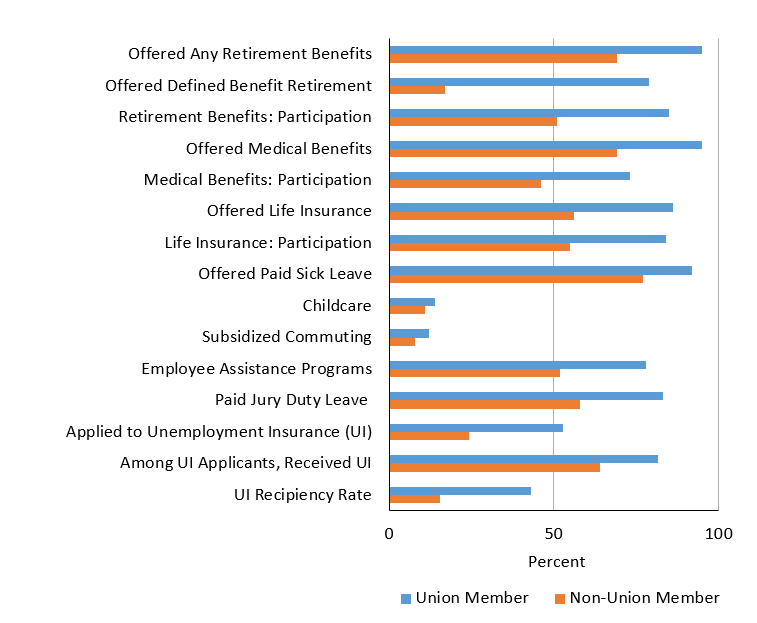

There is strong evidence that unions improve both fringe benefits and non-wage features of the workplace. Figure 3 shows how much more likely it is for a union worker to be offered certain amenities than a nonunion worker. While these simple comparisons reflect correlations only, studies that use more robust empirical approaches find the same: unions have had a large hand in improving work environments on many dimensions and, in doing so, raise the wellbeing of workers and their families. [9]

Figure 3: Fringe Benefits and Amenities

Workplace Equality

The diverse demographics of modern union membership mean that the benefits of any policy that strengthens today’s unions would be felt across the population.Union membership is now roughly equal across men and women. In 2021, Black men had a particularly high union representation rate at 13 percent, as compared to the population average of 10 percent. [10]

Unions promote within-firm equality by adopting explicit anti-discrimination measures, supporting anti-discrimination legislation and enforcement, and promoting wage-setting practices that are less susceptible to implicit bias. As an example of egalitarian wage-setting practices, single rate or automatic progression wage structures contribute to lower within-firm income inequality compared to firms that make individual determinations. [11] These types of practices, and others like publicly available pay schedules, benefit women and vulnerable workers who can be less likely to negotiate aggressively for pay raises.

Empirical studies have confirmed that unions have, indeed, closed race and gender gaps within firms. For example, one study finds that the wage gap between Black and white women was significantly reduced due to union measures. [12] Another study provides evidence of how collective bargaining has reduced gender wage gaps amongst teachers. [13]

The positive effects of unions are not limited to union workers. Nonunionized firms in competition with unionized workplaces may choose to raise wages, change hiring practices, or improve their workplace environment to attract workers. [14] Unions can also affect workplace norms by, say, lobbying for workplace safety improvements, or advocating for changes in minimum wage laws. [15] The empirical evidence finds that these positive spillovers exist. Each 1 percentage point increase in private-sector union membership rates translates to about a 0.3 percent increase in nonunion wages. These estimates are larger for workers without a college degree, the majority of America’s workforce. [16]

Unions may also produce benefits for communities that extend beyond individual workers and employers by enhancing social capital and civic engagement. Union members vote 12 percentage points more often than nonunion members, and nonunion members in union households vote 3 percentage points more often than individuals in nonunion households. [17] In addition, union members are more likely to donate to charity, attend community meetings, participate in a neighborhood project, and volunteer for an organization. [18]

Increased unionization has the potential to contribute to the reversal of the stark increase in inequality seen over the last half century. In turn, increased financial stability to those in the middle or bottom of the income distribution could alleviate borrowing constraints, allowing workers to start businesses, build human capital, and exploit investment opportunities. [19] Reducing inequality can also promote economic resilience by reducing the financial fragility of the bottom 95 percent of the income distribution, making these Americans less sensitive to negative income shocks and thus lessening economic volatility. [20] In short, unions can promote economy-wide growth and resilience.

All in all, the evidence presented in Treasury’s report challenges the view that worker empowerment holds back economic prosperity. In addition to their effect on the economy through more equality, unions can have a positive effect on productivity through employee engagement and union voice effects, providing a road map for the type of union campaigns that could lead to additional growth. [21] One such example found that patient outcomes improved in hospitals where registered nurses unionized. [22]

The Biden-Harris Administration recognizes the benefits of unions to the middle class and the broader economy and has taken actions, outlined in Treasury’s report, to empower workers. There have been promising signs: union petitions in 2022 rose to their highest level since 2015, [23] and public opinion in support of unions is at its highest level in over 50 years. [24] The evidence summarized here and in Treasury’s report suggest these burgeoning signs of strengthening worker power are good news for the middle class and the economy as a whole.

[1] Dynan, Karen, Douglas Elmendorf, and Daniel Sichel. 2012. “The Evolution of Household Income Volatility.” The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 12 (2).

[2] Van Dam, Andrew. 2023. “The mystery of the disappearing vacation day.” The Washington Post, February 10, 2023.

[3] Johnson, Richard W., and Karen E. Smith. 2022. “How Might Millennials Fare in Retirement?” Urban Institute , September 2022.

[4] Chetty, et al. (2017).

[5] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2023. Table 2.: Median weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers by union affiliation and selected characteristics. Last modified January 19, 2023.

[6] For example: Gittleman, Maury, and Morris M. Kleiner. 2016. "Wage effects of unionization and occupational licensing coverage in the United States." ILR Review 69 (1): 142–172; Kleiner, Morris M., and Alan B. Krueger. 2013. “Analyzing the Extent and Influence of Occupational Licensing on the Labor Market.” Journal of Labor Economics 31 (2): S173–S202; DiNardo, John, and David S. Lee. 2004. “Economic Impacts of New Unionization on Private Sector Employers: 1984–2001.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 119 (4): 1383–1441; Frandsen, Brigham R. 2021. “The Surprising Impacts of Unionization: Evidence from Matched Employer-Employee Data.” Journal of Labor Economics 39 (4): 861–894.

[7] Mas, Alexandre, and Amanda Pallais. 2017. "Valuing alternative work arrangements." American Economic Review 107 (12): 3722–59.

[8] Akerlof, George A., Andrew K. Rose, and Janet L. Yellen. 1988. "Job switching and job satisfaction in the US labor market." Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1988 (2): 495–594.

[9] Knepper, Matthew. 2020. “From the Fringe to the Fore: Labor Unions and Employee Compensation.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 102 (1): 98–112.

[10] Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and author’s calculations using BLS data, accessed through IPUMS. Data reflect 2022 values. Sample is employed 16+ year olds. Excludes workers represented by, but not a member of, unions.

[11] See, e.g., Card (1996) and Freeman (1982). Freeman, Richard B. 1982. "Union wage practices and wage dispersion within establishments." ILR Review 36 (1): 3–21.

[12] Rosenfeld, Jake, and Meredith Kleykamp. 2012. “Organized Labor and Racial Wage Inequality in the United States.” American Journal of Sociology 117 (5): 1460–1502.

[13] Biasi, Barbara, and Heather Sarsons. 2022. "Flexible wages, bargaining, and the gender gap." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 137 (1): 215–266.

[14] Fortin, Nicole M., Thomas Lemieux, and Neil Lloyd. 2021. "Labor market institutions and the distribution of wages: The role of spillover effects." Journal of Labor Economics 39 (S2): S369–S412; Taschereau-Dumouchel, Mathieu. 2020. "The Union Threat." The Review of Economic Studies 87 (6): 2859–2892.

[15] The impact of changes in government policy arising out of union advocacy is not the focus of this paper; however, Ahlquist (2017) suggests that advocacy plays an important role in unions’ impacts on the labor market. Spillovers and “threat effects” within the labor market, however, are discussed in this paper. Ahlquist, John S. 2017. “Labor Unions, Political Representation, and Economic Inequality.” Annual Review of Political Science 20 (1): 409–432.

[16] Note: Rosenfeld, Denice, and Laird (2016) do not interpret their estimates causally. Their approach suffers from many of the CPS’s sample size limitations. Although the CPS ostensibly reports quite detailed occupational codes, Rosenfeld, Denice, and Laird estimate regressions with only four occupational codes and 18 industry codes. This data limitation greatly increases the risks that the regression-adjusted approach cannot control for selection effects into unionization.

[17] This 12-percentage-point union voting premium largely reflects socioeconomic factors associated with individuals who join a union. However, when comparing members with non-members who exhibit similar characteristics, there remains a union voting premium of 4 percentage points. Freeman, Richard B. 2003. “What Do Unions Do…to Voting?” National Bureau of Economic Research , working paper no. 9992.

[18] Zullo, Roland. 2011. “Labor Unions and Charity.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 64 (4): 699–711.

[19] Aghion, P., E. Caroli, and C. Garcia-Penalosa. 1999. “Inequality and Economic Growth: The Perspective of the New Growth Theories.” Journal of Economic Literature 37 (4): 1615–60.

[20] Kumhof, Michael, Romain Rancière, and Pablo Winant. 2015. “Inequality, Leverage, and Crises.” American Economic Review 105 (3): 1217–45.

[21] Doucouliagos, Christos, Richard B. Freeman, and Patrice Laroche. 2017. The Economics of Trade Unions: A study of a Research Field and Its Findings . London: Routledge.

[22] Dube, Arindrajit, Ethan Kaplan, and Owen Thompson. 2016. “Nurse unions and patient outcomes.” ILR Review 69 (4): 803–833.

[23] National Labor Relations Board. 2022. “Election Petitions Up 53%, Board Continues to Reduce Case Processing Time in FY22.” Press release. October 6, 2022. https://www.nlrb.gov/news-outreach/news-story/election-petitions-up-53-board-continues-to-reduce-case-processing-time-in .

[24] McCarthy, Justin. 2022. “U.S. Approval of Labor Unions at Highest Point Since 1965.” Gallup , August 30, 202 2.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Am J Public Health

- v.106(6); Jun 2016

The Role of Labor Unions in Creating Working Conditions That Promote Public Health

All authors contributed to the conceptual development of the study. C. A. Paras and H. Greenwich coordinated data collection. All authors collaborated on study design. J. Hagedorn was the primary author of data analysis and interpretation and drafted the article with significant support from A. Hagopian and H. Greenwich. All authors revised content and approved the final version to be published.

We sought to portray how collective bargaining contracts promote public health, beyond their known effect on individual, family, and community well-being. In November 2014, we created an abstraction tool to identify health-related elements in 16 union contracts from industries in the Pacific Northwest. After enumerating the contract-protected benefits and working conditions, we interviewed union organizers and members to learn how these promoted health. Labor union contracts create higher wage and benefit standards, working hours limits, workplace hazards protections, and other factors. Unions also promote well-being by encouraging democratic participation and a sense of community among workers. Labor union contracts are largely underutilized, but a potentially fertile ground for public health innovation. Public health practitioners and labor unions would benefit by partnering to create sophisticated contracts to address social determinants of health.

Labor unions improve conditions for workers in ways that promote individual, family, and community well-being, yet the relationship between public health and organized labor is not fully developed. 1 Despite historic and current efforts by labor unions to improve conditions for workers, public health institutions have rarely sought out labor as a partner. 2,3

In 2014, American labor union density was at a 99-year low. 4 Low union density has left workers vulnerable to reduced health and safety standards, and has fed the decline in public perception of the value of unions. 5,6 Unions have helped to codify economic equity in the workplace, and the decline of their power is associated with the greatest level of economic inequity in our nation’s history. 5,7–9 The erosion of union density has undermined the role of organized labor as a societal power equalizer. 8

Income is a primary social determinant of health, associated with the living environment and overall well-being of individuals or families. 10–16 Income is higher in union jobs than in nonunion jobs, especially for lower-skilled workers. 5,16–18 Retirement or pension plans create the financial stability to promote health into old age. 19 Union employees are more likely to have a retirement or pension plan and are more likely to participate in a retirement plan sponsored by their employer than employees who are not members of a union. 20,21

Researchers have established a correlation between unionized work and a higher percentage of pay coming in the form of highly valued benefits. 22,23 Unions have historically been involved in creating healthy and safe workplaces, advocating regulations that are monitored and enforced by public health entities such as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 3,24

Autonomy and control over one’s life are associated with positive health outcomes, 25–28 and social support in the work environment enhances psychological and physical health. 29,30 Conversely, perceived job insecurity is associated with risk factors for poor health outcomes, contributing to racial and socioeconomic health disparities. 31–35 Unions help members gain control over their scheduling 36,37 and job security, 38 and union membership is associated with increased democratic participation. 39

The American Public Health Association is on record supporting the role of labor unions in promoting healthy working conditions, health and safety programs, health insurance, and democratic participation. 40–42 The decline of union density may undermine public health in the United States, making this a critical time for public health to actively support labor unions.

Previous researchers published in AJPH have highlighted the links between unions, working conditions, and public health, but called for more research to establish the precise mechanism of the relationships. Malinowski et al. proposed the social–ecological model as theoretical framework for connecting public health and labor organizing. 43 Both labor unions and public health organizations intervene in the conditions that make people healthy through individual life choices, and social and community networks, as well as general socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental conditions. Malinowski et al. illustrates the overlapping interests of labor unions and public health and how their lack of coordination has created barriers for both institutions.

One mechanism unions use to promote public health is the union contract. These are legally binding, durable over a designated time, and specific. They are durable because they cannot be unilaterally changed, and contracts that follow often build on the progress of previous negotiations. Even after a contract expires, federal labor law provides a process and momentum for the negotiation of a new one.

We hypothesized that union contracts promote the health status of workers. If true, contracts have untapped potential for public health professionals working to improve the health of individuals and communities.

We designed this cross-sectional, mixed-methods study to identify specific mechanisms that link labor union representation and public health outcomes. Our primary unit of analysis was the negotiated contract between management and labor for a variety of unions in the Puget Sound region of Washington State. We supplemented a textual analysis of the contracts with interviews of union organizers and union members.

In the summer of 2014, we established a partnership between a University of Washington master of public health graduate student (J. H.) and Puget Sound Sage, a nonprofit organization that promotes alignment among labor, environmental, and community interests to “grow communities where all families thrive.” We identified 6 union locals in the region that represented hotel workers, truck drivers, home-care workers, construction workers, child-care workers, office workers, and grocery store workers. Sage held preexisting relationships with these unions, either through representation on Sage’s board or some other form of collaboration, which greatly facilitated our data requests. For each union, we obtained 1 or more labor contracts, for a total of 16 contracts ( Table 1 ).

TABLE 1—

Union Contracts Dated 2010 to 2014 Analyzed for Mechanisms That Advance Health of Employees and Their Families: Pacific Northwest, United States

Note. SEIU = Service Employees International Union; UFCW = United Food and Commercial Workers; UNITE HERE = Union of Needletrades, Industrial, and Textile Employees and Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union. Data for this article came from the 16 union contracts analyzed for their health-related factors, obtained from 5 Puget Sound labor unions in 2014.

Through a comprehensive literature review of the work-related determinants of health, we identified health-related factors that theoretically might be addressed in a labor contract. We then created a spreadsheet abstracting specific language from each contract by each of the theoretical constructs, and, through an iterative process, settled on 12 health factors. For example, we created a cell for “fair and predictable pay increases,” into which the following Service Employees International Union (SEIU) 775 contract language was placed:

Employees who complete advanced training beyond the training required to receive a valid Home Care Aide certification (as set forth in the Training Partnership curriculum) shall be paid an additional twenty-five cents ($0.25) per hour differential to his/her regular hourly wage rate.

After creating the 12 large categories, we further analyzed the contract language in our spreadsheet to generate 34 subcategories ( Table 2 ). We suggest that these 34 factors, taken together, comprise the specific mechanisms by which labor contract language supports public health. We determined whether the indicators were present in each contract (Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org ) and Table 2 reports what proportion of contracts contained language on each of the 34 factors. When “all” contracts have an indicator, this means each of the 16 contracts contains health-protecting language on the topic. “Almost all” refers to 14 or 15 contracts, “most” means 7 to 13 contracts, and “some” refers to 5 or 6 contracts.

TABLE 2—

Factors That Advance Health of Employees Theorized to be Found in Union Contracts, and Their Presence in 16 Union Contracts Dated 2010 to 2014: Pacific Northwest, United States

Note. All = 16 contracts; almost all = 14 or 15 contracts; most = 7 to 13 contracts; some = 5 or 6 contracts. Data for this article came from the 16 union contracts analyzed for their health-related factors, obtained from 5 Puget Sound labor unions in 2014.

To supplement our analysis, we interviewed 1 member from each of the 6 unions covered by a contract in our analysis, as well as 7 union organizers representing those members ( Table 3 ). In 1-hour interviews with union organizers, we explored how contract language is aligned with public health outcomes through questions about their job and the role of the union. We asked workers about the dangers in their job and if or how the union helps to protect them, we asked about safety and health problems and the union’s role in addressing those, and we asked about conflict in the workplace and whether the union helps to resolve issues. We also asked workers to compare any workplaces they had experienced without a union to their current workplace.

TABLE 3—

Interviews Conducted With Union Members and Organizers: Pacific Northwest, United States, 2015

Note. SEIU = Service Employees International Union; UFCW = United Food and Commercial Workers; UNITE HERE = Union of Needletrades, Industrial, and Textile Employees and Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union. Interviews conducted between January and April 2015 with Puget Sound–area labor union staff and industry employees to supplement our understanding of the role of labor union contracts in protecting employee health.

Each union assisted in identifying a covered member for us to interview. Usually, an e-mail was sent to members the organizer thought may be interested in the study. These members were compensated $50 for their 1-hour interviews, with funds provided by Sage. In interviews with members, we asked about the most dangerous or hazardous aspects of their jobs and how the union helps to mitigate those risks, as well as other benefits of being a union member.

There is consistency among contracts negotiated by same union (Table A). Contracts with public sector entities (such as 925.2, Headstart Program; 775.3, State of Washington; and 242.3, Seattle School District) have fewer provisions that contribute to health in their contracts.

Compensation

We created compensation indicators illustrating how the wages of employees are augmented when employers are prohibited from externalizing their costs by having employees pay for work-related travel, training, and materials.

All contracts include minimum wages by employee classifications, including overtime. Higher income and overtime wage gains are built over time. Income is augmented when employers are directed to cover specific work-related expenses. Most contracts compensate employees for the cost of traveling between work sites and the cost (or partial costs) of trainings. Some contracts also provide money for materials, such as United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) contract 21.2, which states, “The Employer shall bear the expense of furnishing and laundering aprons, shop coats, and smocks, for all employees under this Agreement.” Other contracts ensure employers will not call in more employees than needed and then send them home; they do this by creating a “show-up pay” provision. Laborers’ contract 242.1 describes this as

Employees reporting for work and not put to work shall receive two hours pay at the regular straight time rate, unless inclement weather conditions prohibits work, or notified not to report at the end of the previous shift or two hours prior to the start of a shift.

One child-care worker explained how union advocacy has increased the supplement provided by the state for the extra challenges posed by caring for low-income children, saying “For family childcare workers, who are often very underpaid for the amount of hours that they work, we have seen over the last 8 years, a 22% increase in our subsidized childcare. That is big!” Another worker from Teamsters Local 117 said, “I know there are guys doing the same job [in nonunion warehouses] making $10 less an hour.”

Predictable and fair increases.

All contracts provide wage increases on the basis of qualifications, duties, and duration of time at the company. Workers can increase their wages by increasing their training or by assuming additional responsibilities, including mentoring peers, accepting clients with higher needs, working less-desirable hours, doing more physically strenuous labor, or taking on leadership roles within a working group. Some contracts require transparency in paycheck calculations, mandating employers to itemize hours, overtime, and sometimes the cumulative number of sick days or holidays used, allowing employees to check the calculations.

An organizer with UFCW (grocery) Local 21 explained, “[employers] see experience as a cost and not a driver of sales.” The organizer explained that without the contracts, employers would not raise wages over time, especially for jobs viewed as requiring fewer technical skills.

Retirement and pension.

Almost all contracts include retirement or pensions. Most of these are set up in the form of trusts, with a collaborative process for management and employees to manage money and benefits. This language usually exists in a separate document referred to by the contract.

A retired member of Laborers Local 242 described how he was able to adjust his hours to make the money he needed, but also be able to retire comfortably because of his savings and pension. He explained, “I retired early. I wanted to do things that I wasn’t able to do when I was younger because I had to support the family.”

We created indicators to track evidence-based factors related to physical and psychological health, including time off and access to health care. 44–46

Paid time off.

Most contracts include the indicators of paid annual leave, paid rest periods, and bereavement leave. The amount of annual leave varies, but usually increases as the employee gains seniority. Paid rest periods are usually defined as short, 15- to 30-minute periods. Bereavement leave to attend a funeral or grieve a loss can be used for specific family members in some contracts, whereas others allow its use for a broader range of relationships.

Health care coverage.

Health insurance is included in all contracts. We did not attempt to distinguish among contracts with regard to affordability, comprehensiveness, or number of dependents covered because health care is managed by trusts, much like retirement or pension benefits.

All of the organizers discussed the benefits of union health coverage. An organizer from UFCW Local 21 explained,

Members have consistently traded wages for health benefits. They have been willing to have slowed wage increases in order to maintain their strong health benefits over and over and over. What I see if I go into a [unionized grocery] I see a much higher percentage of people who have children who rely on their health insurance.

Health and Safety

Most contracts guide how health and safety regulations are communicated to workers, including written and verbal forms.

Health and safety information.

Although most contracts include health and safety information, they are usually not very specific. For example, Teamsters’ contract 117.1, states,

[T]he Company may require the use of safety devices and safeguards and shall adopt and use practices, means, methods, operations and processes which are adequate to render such employment and place of employment safe and shall do all things necessary to protect the life and safety of all employees.

Most contracts also include a provision allowing the union to post and maintain a bulletin board to communicate information to members. Contracts also generally ensure union representative access to the worksite. For example, SEIU contract 925.2 (child-care workers) states,

The designated Stewards or Chief Stewards shall have access to the premises of [Community Development Institute Head Start] to carry out their duties subject to permission being granted in advance.

Training and mentorship.

Almost all contracts explicitly require training. Some contracts include compensation for providing mentorship to encourage more senior employees to provide support to new employees or employees taking on new roles.

One organizer from Laborers Local 242 described how important it is for workers to know how to do their work safely, for themselves, coworkers, workplace clients, and their own families. For example, a hospital demolition crew should know how to contain particulate matter to avoid contaminating patients or bringing it home to expose their children. The organizer said training ensures “If you hire a [union] laborer, you know you’re going to get the best product. We have the safest workforce. We’re the most experienced.”

Promotion of a culture of workplace safety.

Most contracts detail the employer’s responsibility to provide and maintain protective clothing and equipment. Most contracts also protect bringing a safety hazard to the attention of a supervisor. For example, SEIU contract 775.5 states, “the employee will immediately report to their Employer any working condition the employee believes threatens or endangers the health or safety of the employee or client.” Some contracts have a provision allowing workers who return to work after an injury to receive less strenuous work, or “light duty.” Both Laborers’ contracts contain this provision, an important provision for physically demanding work.

Promoting Individual, Family, and Community Well-Being

We analyzed indicators that measure the role of contracts in reinforcing social support in the work environment.

Job protections and security.

All contracts contain specific and detailed grievance procedures, the process of reporting, mediating, and resolving conflicts in the workplace. Almost all contracts confirm the right to have a union representative present during meetings with managers. Some contracts, such as SEIU 775.1, make it the employer’s responsibility to make this known:

In any case where a home care aide is the subject of a written formal warning the Employer will notify the home care aide of the purpose of the meeting and their option to have a local union representative present when the meeting is scheduled.

Most contracts also establish or maintain a labor relations or management committee. Although the language about this committee may differ, the purpose of the group is to create a space in which workers and employers can negotiate problems that arise between negotiations of new contracts.

Almost all contracts contain a commitment to creating a discrimination-free workplace. Most contracts create the opportunity for a worker to take a leave of absence without sacrificing seniority for maternity leave, further education, religious holidays (e.g., Yom Kippur, Easter), military leave (for the employee or spouse), domestic violence, sexual assault, stalking, or union activity.

Fair and predictable scheduling.

Most contracts include a mandatory notice of schedule changes. As UFCW contract 21.1 explains,

The Employer recognizes the desirability of giving his employees as much notice as possible in the planning of their weekly schedules of work and, accordingly, agrees to post a work schedule.

Some contracts specify the amount of notice required for a schedule change. Those that change regularly may require posting the week before. Most contracts also include an amount of time required between shifts or minimum shift length, and how employees can request additional hours.

Democratic participation.

Most contracts provide employees the opportunity to participate in union-sponsored legislative “lobby days,” or to engage in political work while being paid by their employer. As SEIU contract 925.1 explains,

As part of our ongoing campaign to provide the highest possible standard of childcare and engage in an ongoing public campaign to explain the direct relationship between funding and the quality of care, it is in each party’s best interest to provide reasonable opportunity for members of the bargaining unit to participate in these efforts.

Contracts require all union members to pay dues. Some contracts also specify how a union member can contribute to a political action fund, which generates revenue to represent employee interests in the policy arena. One home health worker explained that she is getting more involved in politics and collective bargaining because of union engagement, saying,

I like belonging to a union that believes in me as an individual and as a caregiver. They’re behind us every step of the way. They help us to look at things that otherwise we might not be aware of, like state legislation and contract negotiation.

Public health practitioners have not typically viewed unions as partners in promoting public health, nor have they explored contract negotiations as a way to ensure health protections. We suggest that this is a missed opportunity. Our findings demonstrate that union contract language advances many of the social determinants of health, including income, security, time off, access to health care, workplace safety culture, training and mentorship, predictable scheduling to ensure time with friends and family, democratic participation, and engagement with management. This article provides a provisional framework to explore further the factors that create public health opportunities in union contracts.

We examined selected union contracts in the Pacific Northwest, which may not be generalizable. Our sample included only those unions in a relationship with Puget Sound Sage, perhaps suggesting unique perspectives or priorities. We compared our sampled unions to those in the King County Labor Council, however, and although there were some industries not represented (e.g., aerospace, teachers, assembly line workers), we believe the types of workplaces in our sample are reasonably representative of the landscape of unions in the county. We did not attempt to incorporate the views of the respective employers on these contracts.

The language in the contracts we reviewed included rights won at the bargaining table along with restatements of existing city, state, and federal laws. For example, leave without pay contract provisions match the Washington State Family Leave Act. When union negotiators include these indicators in contracts, they generate awareness of health-promoting regulations and protections. Laws and policies can change, but a union contract can only change if the union agrees to renegotiate the contract or if the contract has expired. Union stewards learn the details about a contract, but cannot be expected to know the full range of laws from a variety of jurisdictions. The contract works to reinforce the knowledge of workers and their representatives. Although it was beyond the scope of our study, contracts must be enforced to actualize their health-related benefits. Effective enforcement mechanisms for contracts are also potentially beneficial to public health officials. 22,27,47

We identified many contract indicators that advance health for more than just employees. Unions generate higher prevailing wages in a community. 7,48 Unions invest in campaigns to raise wages for both union and nonunion workers, such as the $15 hourly wage initiative in SeaTac, Washington. 49,50 A safer environment for home-care and child-care workers creates safer environments for the people they serve. A culture of safety on construction sites ensures that environmental hazards are minimized for people who live nearby. Parents earning a living wage can avoid taking second jobs and use the time to engage in children’s schools or community councils. A healthy and happy workforce is more productive and less likely to leave a job, reducing the cost of turnover and absenteeism for employers. In spite of the many benefits unions confer to workplaces and communities, union membership is now limited to only 1 in 10 American employees. 4

The decline of labor union density is related to both the rise of corporate power and to mistakes made by labor. 1 After a period of radical inclusivity and left-leaning solidarity with broader political movements, unions moved toward racism and red-baiting in the 1950s, undermining their strength. 51 Unions are still working to reduce racial and gender disproportionality within their leadership. 52

Despite historical shortcomings, labor unions (and their contracts) offer an underutilized opportunity for public health innovation. As illustrated by Malinowski et al., public health practitioners often work in the “outer” layers of the social–ecological model, promoting environments that can better shape population health. 43 This is also true of labor unions. Public health practitioners could help unions negotiate more sophisticated contracts to address the social determinants of health. Public health practitioners could also work with policymakers to heighten awareness of how unions might help mitigate the forces that threaten health in the workplace and beyond. Supporting progressive labor union contracts is public health work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge a grant from the University of Washington Harry Bridges Labor Center that made this work possible. Also, thank you to Puget Sound Sage for providing the compensation for labor union members who were interviewed.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Ethical approval for the project was provided by the University of Washington institutional review board, approval 48520-EJ.

UAW workers pose with signs.

US Unions Must Look Beyond Themselves to Save Themselves

Either we think about unionism in new ways and establish new ways of joining other movements, or most of our unions die a long, slow, painful death..

The labor movement in the United States used to be respected and looked to for leadership; people cared about what positions labor took, watched when they mobilized, and noticed the causes they supported. This was especially true among the left. Today, for most of the country, crickets. Including much of the left. And yet, labor is a source of potential power unrivaled by any other bottom-up social grouping in the country.

As one who has written extensively about labor around the world and in the United States— see my list of publications with many links to the original articles—I have been thinking over a number of years about the future direction of the U.S. labor movement. But this thinking is not just based on writing or academic research; I’ve done that and also have years of experience as a labor activist and as one who has worked in blue, white, and pink collar jobs over the past 40+ years and in multiple locations across the country.

I argue that we haven’t had a labor movement in the U.S. since 1949, when the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) expelled 11 so-called “left-led” unions with somewhere between 750,000 and 1 million members; we’ve had only a trade union movement. What’s the difference? A labor movement looks out for the well-being of all working people in the country, while a trade union movement only looks out for members of its member unions.

We see workers creating reform movements trying to transform their unions for the benefit of the entire membership, if not all workers.

And, especially since 1981, when the trade union movement failed to defend the striking air traffic controllers in the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) strike when attacked by then-U.S. President Ronald Reagan, the trade union movement leaders have done little but watch its ranks shrink, its prestige fall, and its power decline. Millions of jobs have been shipped overseas while the manufacturing economy has been decimated, and most of the service sector jobs since created have remained ununionized, underpaid, and with many fewer protections for workers. Yes, acting together, the trade union movement has worked to elect Democrats such as Bill Clinton and Barack Obama to office, but between signing the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994, and the failure to pass a bill to enhance labor organizing, I’d say neither could be considered blazing successes. Individual unions have succeeded here and there, but only episodically and not consistently, and usually only because of some tactical feature that gave them a winning advantage in a particular struggle. Inspiring not.

The only consistent trade union success since the early 1980s has been in sucking up U.S. government money—often between $30-75 million annually—which has allowed AFL-CIO foreign policy leaders to act behind the backs of most of the organization’s leaders and all of its affiliated union members, in our name, in efforts generally intended to undercut foreign workers’ struggles against multinational corporations and U.S. government foreign policy projects.

Worse, even while nonetheless being helpful to foreign workers in a few cases, the AFL-CIO has acted to legitimize the imperialist National Endowment for Democracy (NED) by serving as one of its four “core institutes,” along with the international wing of the Democratic Party, the international wing of the Republican Party, and the international wing of its domestic archenemy, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, in NED’s on-going project of supporting and advancing the U.S. Empire.

Thus, the trade unions’ leadership has generally done little to advance the interests and well-being of U.S. workers, while acting in differential manners—usually bad—with foreign workers. I don’t think this was what Karl Marx and Frederick Engles were expecting when they echoed the French feminist, Flora Tristan, urging, “Workers of the World, Unite!”

Yet, despite the general failure of the trade union movement leadership, especially since 1981, the reality is that unions are one set of institutions that, at their best, are of the workers, by the workers, and for the workers. You see workers fighting to make their unions “real”—trying to make them part of a labor movement that serves the interests of all workers if not the entire society—over the years. We see workers creating reform movements trying to transform their unions for the benefit of the entire membership, if not all workers.

Perhaps the most famous of late has been the reform organization Unite All Workers for Democracy (UAWD) inside the United Auto Workers. UAWD came together to fight for direct elections of UAW leadership instead of the convention elections, which had led to a one-party state since 1946 and the election of Walter Reuther. Over time, a number of top-level UAW leaders were charged with corruption, and in a consent agreement with the federal government, the UAW had to shift to direct elections for top officers. UAWD put forth a partial slate headed by Shawn Fain, and then proceeded to win every leadership position they sought, ultimately gaining control of the international union’s executive board.

In turn, Fain and his administration led the 2023 fight against the Big Three auto companies—General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis, the parent of Chrysler—and won the strike in the fall. While the UAW did not win all of its demands in the strike, it clearly demonstrated the power of organized workers who have a leadership that will fight for and with them. And following that successful strike, Volkswagen workers at Chattanooga, Tennessee, voted to join the UAW, with help from the German union, IG Metal, although in the face of governors from six southern states telling them to not do so.

It is critical to understand that unions are important to many workers; that they make a difference in the workplace; and that they usually mean higher wages, better benefits, seniority systems, and a recognizable “rule of law” in the workplace, the latter which places some limits on management authority and discipline; a big difference from the situation of most workplaces where workers give up most if not all of their rights when they enter company grounds.

So, where does this lead us?