Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

How do you read organization’s silence over rise of Nazism?

Got milk? Does it give you problems?

Cancer risk, wine preference, and your genes

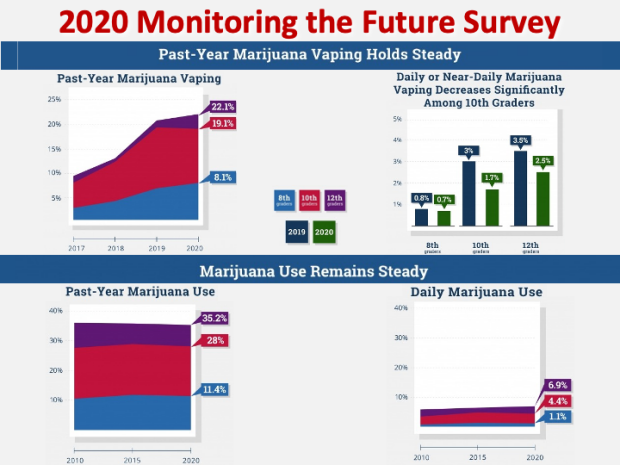

Studies show that about 9 percent of the population and nearly 28 percent of high school students are e-cigarette users.

Diego Cervo/iStock by Getty Images

Restricted airways, scarred lung tissue found among vapers

MGH News and Public Affairs

Small study looks at chronic e-cigarette users, seeing partial improvement once they stop

Chronic use of e-cigarettes, commonly known as vaping, can result in small airway obstruction and asthma-like symptoms, according to researchers at Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital.

More like this

Teen vaping rising fast, research says

Survey of oncologists finds knowledge gap on medical marijuana

Chemical flavorings found in e-cigarettes linked to respiratory disease

In the first study to microscopically evaluate the pulmonary tissue of e-cigarette users for chronic disease, the team found in a small sample of patients fibrosis and damage in the small airways, similar to the chemical inhalation damage to the lungs typically seen in soldiers returning from overseas conflicts who had inhaled mustard or similar types of noxious gases. The study was published in New England Journal of Medicine Evidence .

“All four individuals we studied had injury localized to the same anatomic location within the lung, manifesting as small airway-centered fibrosis with constrictive bronchiolitis, which was attributed to vaping after thorough clinical evaluations excluded other possible causes,” says lead author Lida Hariri, an associate professor of pathology at Harvard Medical School and a pathologist and physician investigator at MGH. “We also observed that when patients ceased vaping, they had a partial reversal of the condition over one to four years, though not complete due to residual scarring in the lung tissue.”

A huge increase in vaping, particularly among young adults and adolescents, has occurred in the United States, with studies showing about 9 percent of the population and nearly 28 percent of high school students are e-cigarette users. Unlike cigarette smoking, however, the long-term health risks of chronic vaping are largely unknown.

In order to determine the underlying pathophysiology of vaping-related symptoms, the MGH team examined a cohort of four patients, each with a three- to eight-year history of e-cigarette use and chronic lung disease. All patients underwent detailed clinical evaluation, including pulmonary function tests, high resolution chest imaging, and surgical lung biopsy. Constrictive bronchiolitis, or narrowing of the small airways due to fibrosis within the bronchiolar wall, was observed in each patient. So was significant overexpression of MUC5AC, a gel-forming protein in the mucus layer of the airway that has been seen in airway cell and sputum samples of individuals who vape. In addition, three of the four patients had evidence of mild emphysema consistent with their former combustible cigarette smoking history, though researchers concluded this was distinct from the findings of constrictive bronchiolitis seen in the patient cohort.

Because the same type of lung damage was observed in all patients, as well as partial improvement in symptoms after e-cigarette usage was stopped, researchers concluded that vaping was the most likely cause after thorough evaluation and exclusion of other possible causes. “Our investigation shows that chronic pathological abnormalities can occur in vaping exposure,” says senior author David Christiani, a professor of medicine at HMS and a physician investigator at Mass General Research Institute. “Physicians need to be informed by scientific evidence when advising patients about the potential harm of long-term vaping, and this work adds to a growing body of toxicological evidence that nicotine vaping exposures can harm the lung.”

A hopeful sign from the study was that three of the four patients showed improvements in their pulmonary function tests and high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) chest imaging after they ceased vaping. “While there is growing evidence to show that vaping is a risky behavior with potential long-term health consequences for users,” says Hariri, “our research also suggests that quitting can be beneficial and help to reverse some of the disease.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Share this article

You might like.

Medical historians look to cultural context, work of peer publications in wrestling with case of New England Journal of Medicine

Biomolecular archaeologist looks at why most of world’s population has trouble digesting beverage that helped shape civilization

Biologist separates reality of science from the claims of profiling firms

Epic science inside a cubic millimeter of brain

Researchers publish largest-ever dataset of neural connections

Finding right mix on campus speech policies

Legal, political scholars discuss balancing personal safety, constitutional rights, academic freedom amid roiling protests, cultural shifts

Good genes are nice, but joy is better

Harvard study, almost 80 years old, has proved that embracing community helps us live longer, and be happier

Advertisement

How bad is vaping for your health? We’re finally getting answers

As more of us take up vaping and concerns rise about the long-term effects, we now have enough data to get a grip on the health impact – and how it compares to smoking

By Graham Lawton

6 December 2023

Klaus Kremmerz

AS THE old joke goes, when I read about the dangers of smoking, I gave up reading. If you are a vaper, you might feel like you want to stop reading now. Don’t: you need to know this.

I am a vaper. Like many others, I used to smoke and switched to vaping for health reasons. I plan to quit completely, but I haven’t managed it yet. I am sure vaping is better for me than smoking, but I am also sure it is worse than not vaping. I cough in the morning and feel massively addicted to the nicotine. I don’t even really know what I am inhaling. I worry that it will be hard to quit, that I am causing long-term damage to my body and that by vaping, I am susceptible to slipping back down the slope to cigarettes. I also have the same worries for the teenagers I see coming out of school and immediately enveloping themselves in sweet-smelling clouds.

Is CBD a wonder drug or waste of money? Here's what the evidence says

As vaping has increased throughout the Western world, these fears have been repeated often. Part of last month’s King’s Speech in the UK focused on new legislation aiming to create a smoke-free generation in part by cracking down on youth vaping. Worldwide, there have been calls for tougher regulation and more investigation into vaping’s health effects as increasing numbers of children admit to taking up the habit.

But there hasn’t been a huge amount to say on whether fears over health effects are well-founded – until recently. Now, vaping…

Sign up to our weekly newsletter

Receive a weekly dose of discovery in your inbox! We'll also keep you up to date with New Scientist events and special offers.

To continue reading, subscribe today with our introductory offers

No commitment, cancel anytime*

Offer ends 2nd of July 2024.

*Cancel anytime within 14 days of payment to receive a refund on unserved issues.

Inclusive of applicable taxes (VAT)

Existing subscribers

More from New Scientist

Explore the latest news, articles and features

Cannabis vaping liquids contain lead and other toxic metals

Subscriber-only

Why does the UK want to ban disposable vapes and when will it happen?

Patchwork vaping regulation can show the way to a smoke-free world, vaping vs edibles: how does the way we use cannabis alter its effects, popular articles.

Trending New Scientist articles

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Impact of vaping on...

Impact of vaping on respiratory health

Linked editorial.

Protecting children from harms of vaping

- Related content

- Peer review

- Andrea Jonas , clinical assistant professor

- Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care, Department of Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

- Correspondence to A Jonas andreajonas{at}stanford.edu

Widespread uptake of vaping has signaled a sea change in the future of nicotine consumption. Vaping has grown in popularity over the past decade, in part propelled by innovations in vape pen design and nicotine flavoring. Teens and young adults have seen the biggest uptake in use of vape pens, which have superseded conventional cigarettes as the preferred modality of nicotine consumption. Relatively little is known, however, about the potential effects of chronic vaping on the respiratory system. Further, the role of vaping as a tool of smoking cessation and tobacco harm reduction remains controversial. The 2019 E-cigarette or Vaping Use-Associated Lung Injury (EVALI) outbreak highlighted the potential harms of vaping, and the consequences of long term use remain unknown. Here, we review the growing body of literature investigating the impacts of vaping on respiratory health. We review the clinical manifestations of vaping related lung injury, including the EVALI outbreak, as well as the effects of chronic vaping on respiratory health and covid-19 outcomes. We conclude that vaping is not without risk, and that further investigation is required to establish clear public policy guidance and regulation.

Abbreviations

BAL bronchoalveolar lavage

CBD cannabidiol

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

DLCO diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide

EMR electronic medical record

END electronic nicotine delivery systems

EVALI E-cigarette or Vaping product Use-Associated Lung Injury

LLM lipid laden macrophages

THC tetrahydrocannabinol

V/Q ventilation perfusion

Introduction

The introduction of vape pens to international markets in the mid 2000s signaled a sea change in the future of nicotine consumption. Long the mainstay of nicotine use, conventional cigarette smoking was on the decline for decades in the US, 1 2 largely owing to generational shifts in attitudes toward smoking. 3 With the advent of vape pens, trends in nicotine use have reversed, and the past two decades have seen a steady uptake of vaping among young, never smokers. 4 5 6 Vaping is now the preferred modality of nicotine consumption among young people, 7 and 2020 surveys indicate that one in five US high school students currently vape. 8 These trends are reflected internationally, where the prevalence of vape products has grown in both China and the UK. 9 Relatively little is known, however, regarding the health consequences of chronic vape pen use. 10 11 Although vaping was initially heralded as a safer alternative to cigarette smoking, 12 13 the toxic substances found in vape aerosols have raised new questions about the long term safety of vaping. 14 15 16 17 The 2019 E-cigarette or Vaping product Use-Associated Lung Injury (EVALI) outbreak, ultimately linked to vitamin E acetate in THC vapes, raised further concerns about the health effects of vaping, 18 19 20 and has led to increased scientific interest in the health consequences of chronic vaping. This review summarizes the history and epidemiology of vaping, and the clinical manifestations and proposed pathophysiology of lung injury caused by vaping. The public health consequences of widespread vaping remain to be seen and are compounded by young users of vape pens later transitioning to combustible cigarettes. 4 21 22 Deepened scientific understanding and public awareness of the potential harms of vaping are imperative to confront the challenges posed by a new generation of nicotine users.

Sources and selection criteria

We searched PubMed and Ovid Medline databases for the terms “vape”, “vaping”, “e-cigarette”, “electronic cigarette”, “electronic nicotine delivery”, “electronic nicotine device”, “END”, “EVALI”, “lung injury, diagnosis, management, and treatment” to find articles published between January 2000 and December 2021. We also identified references from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website, as well as relevant review articles and public policy resources. Prioritization was given to peer reviewed articles written in English in moderate-to-high impact journals, consensus statements, guidelines, and included randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and case series. We excluded publications that had a qualitative research design, or for which a conflict of interest in funding could be identified, as defined by any funding source or consulting fee from nicotine manufacturers or distributors. Search terms were chosen to generate a broad selection of literature that reflected historic and current understanding of the effects of vaping on respiratory health.

The origins of vaping

Vaping achieved widespread popularity over the past decade, but its origins date back almost a century and are summarized in figure 1 . The first known patent for an “electric vaporizer” was granted in 1930, intended for aerosolizing medicinal compounds. 23 Subsequent patents and prototypes never made it to market, 24 and it wasn’t until 1979 that the first vape pen was commercialized. Dubbed the “Favor” cigarette, the device was heralded as a smokeless alternative to cigarettes and led to the term “vaping” being coined to differentiate the “new age” method of nicotine consumption from conventional, combustible cigarettes. 25 “Favor” cigarettes did not achieve widespread appeal, in part because of the bitter taste of the aerosolized freebase nicotine; however, the term vaping persisted and would go on to be used by the myriad products that have since been developed.

Timeline of vape pen invention to widespread use (1970s-2020)

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

The forerunner of the modern vape pen was developed in Beijing in 2003 and later introduced to US markets around 2006. 26 27 Around this time, the future Juul Laboratories founders developed the precursor of the current Juul vape pen while they were students at the Stanford Byers-Center for Biodesign. 28 Their model included disposable cartridges of flavored nicotine solution (pods) that could be inserted into the vape pen, which itself resembled a USB flash drive. Key to their work was the chemical alteration of freebase nicotine to a benzoate nicotine salt. 29 The lower pH of the nicotine salt resulted in an aerosolized nicotine product that lacked a bitter taste, 30 and enabled manufacturers to expand the range of flavored vape products. 31 Juul Laboratories was founded a decade later and quickly rose to dominate the US market, 32 accounting for an estimated 13-59% of the vape products used among teens by 2020. 6 8 Part of the Juul vape pen’s appeal stems from its discreet design, as well as its ability to deliver nicotine with an efficiency matching that of conventional cigarettes. 33 34 Subsequent generations of vape pens have included innovations such as the tank system, which allowed users to select from the wide range of different vape solutions on the market, rather than the relatively limited selection available in traditional pod based systems. Further customizations include the ability to select different vape pen components such as atomizers, heating coils, and fluid wicks, allowing users to calibrate the way in which the vape aerosol is produced. Tobacco companies have taken note of the shifting demographics of nicotine users, as evidenced in 2018 by Altria’s $12.8bn investment in Juul Laboratories. 35

Vaping terminology

At present, vaping serves as an umbrella term that describes multiple modalities of aerosolized nicotine consumption. Vape pens are alternatively called e-cigarettes, electronic nicotine delivery systems (END), e-cigars, and e-hookahs. Additional vernacular terms have emerged to describe both the various vape pen devices (eg, tank, mod, dab pen), vape solution (eg, e-liquid, vape juice), as well as the act of vaping (eg, ripping, juuling, puffing, hitting). 36 A conventional vape pen is a battery operated handheld device that contains a storage chamber for the vape solution and an internal element for generating the characteristic vape aerosol. Multiple generations of vape pens have entered the market, including single use, disposable varieties, as well as reusable models that have either a refillable fluid reservoir or a disposable cartridge for the vape solution. Aerosol generation entails a heating coil that atomizes the vape solution, and it is increasingly popular for devices to include advanced settings that allow users to adjust features of the aerosolized nicotine delivery. 37 38 Various devices allow for coil temperatures ranging from 110 °C to over 1000 °C, creating a wide range of conditions for thermal degradation of the vape solution itself. 39 40

The sheer number of vape solutions on the market poses a challenge in understanding the impact of vaping on respiratory health. The spectrum of vape solutions available encompasses thousands of varieties of flavors, additives, and nicotine concentrations. 41 Most vape solutions contain an active ingredient, commonly nicotine 42 ; however, alternative agents include tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) or cannabidiol (CBD). Vape solutions are typically composed of a combination of a flavorant, nicotine, and a carrier, commonly propylene glycol or vegetable glycerin, that generates the characteristic smoke appearance of vape aerosols. Some 450 brands of vape now offer more than 8000 flavors, 41 a figure that nearly doubled over a three year period. 43 Such tremendous variety does not account for third party sellers who offer users the option to customize a vape solution blend. Addition of marijuana based products such as THC or CBD requires the use of an oil based vape solution carrier to allow for extraction of the psychoactive elements. Despite THC vaping use in nearly 9% of high schoolers, 44 THC vape solutions are subject to minimal market regulation. Finally, a related modality of THC consumption is termed dabbing, and describes the process of inhaling aerosolized THC wax concentrate.

Epidemiology of vaping

Since the early 2000s, vaping has grown in popularity in the US and elsewhere. 8 45 Most of the 68 million vape pen users are concentrated in China, the US, and Europe. 46 Uptake among young people has been particularly pronounced, and in the US vaping has overtaken cigarettes as the most common modality of nicotine consumption among adolescents and young adults. 47 Studies estimate that 20% of US high school students are regular vape pen users, 6 48 in contrast to the 5% of adults who use vape products. 2 Teen uptake of vaping has been driven in part by a perception of vaping as a safer alternative to cigarettes, 49 50 as well as marketing strategies that target adolescents. 33 Teen use of vape pens is further driven by the low financial cost of initiation, with “starter kits” costing less than $25, 51 as well as easy access through peer sales and inconsistent age verification at in-person and online retailers. 52 After sustained growth in use over the 2010s, recent survey data from 2020 suggest that the number of vape pen users has leveled off among teens, perhaps in part owing to increased perceived risk of vaping after the EVALI outbreak. 8 53 The public health implications of teen vaping are compounded by the prevalence of vaping among never smokers (defined as having smoked fewer than 100 lifetime cigarettes), 54 and subsequent uptake of cigarette smoking among vaping teens. 4 55 Similarly, half of adults who currently vape have never used cigarettes, 2 and concern remains that vaping serves as a gateway to conventional cigarette use, 56 57 although these results have been disputed. 58 59 Despite regulation limiting the sale of flavored vape products, 60 a 2020 survey found that high school students were still predominantly using fruit, mint, menthol, and dessert flavored vape solutions. 48 While most data available surround the use of nicotine-containing vape products, a recent meta-analysis showed growing prevalence of adolescents using cannabis-containing products as well. 61

Vaping as harm reduction

Despite facing ongoing questions about safety, vaping has emerged as a potential tool for harm reduction among cigarette smokers. 12 27 An NHS report determined that vaping nicotine is “around 95% less harmful than cigarettes,” 62 leading to the development of programs that promote vaping as a tool of risk reduction among current smokers. A 2020 Cochrane review found that vaping nicotine assisted with smoking cessation over placebo 63 and recent work found increased rates of cigarette abstinence (18% v 9.9%) among those switching to vaping compared with conventional nicotine replacement (eg, gum, patch, lozenge). 64 US CDC guidance suggests that vaping nicotine may benefit current adult smokers who are able to achieve complete cigarette cessation by switching to vaping. 65 66

The public health benefit of vaping for smoking cessation is counterbalanced by vaping uptake among never smokers, 2 54 and questions surrounding the safety of chronic vaping. 10 11 Controversy surrounding the NHS claim of vaping as 95% safer than cigarettes has emerged, 67 68 and multiple leading health organizations have concluded that vaping is harmful. 42 69 Studies have demonstrated airborne particulate matter in the proximity of active vapers, 70 and concern remains that secondhand exposure to vaped aerosols may cause adverse effects, complicating the notion of vaping as a net gain for public health. 71 72 Uncertainty about the potential chronic consequences of vaping combined with vaping uptake among never smokers has complicated attempts to generate clear policy guidance. 73 74 Further, many smokers may exhibit “dual use” of conventional cigarettes and vape pens simultaneously, further complicating efforts to understand the impact of vape exposure on respiratory health, and the role vape use may play in smoking cessation. 12 We are unable to know with certainty the extent of nicotine uptake among young people that would have been seen in the absence of vaping availability, and it remains possible that some young vape pen users may have started on conventional cigarettes regardless. That said, declining nicotine use over the past several decades would argue that many young vape pen users would have never had nicotine uptake had vape pens not been introduced. 1 2 It remains an open question whether public health measures encouraging vaping for nicotine cessation will benefit current smokers enough to offset the impact of vaping uptake among young, never smokers. 75

Vaping lung injury—clinical presentations

Vaping related lung injury: 2012-19.

The potential health effects of vape pen use are varied and centered on injury to the airways and lung parenchyma. Before the 2019 EVALI outbreak, the medical literature detailed case reports of sporadic vaping related acute lung injury. The first known case was reported in 2012, when a patient presented with cough, diffuse ground glass opacities, and lipid laden macrophages (LLM) on bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) return in the context of vape pen use. 76 Over the following seven years, an additional 15 cases of vaping related acute lung injury were reported in the literature. These cases included a wide range of diffuse parenchymal lung disease without any clear unifying features, and included cases of eosinophilic pneumonia, 77 78 79 hypersensitivity pneumonitis, 80 organizing pneumonia, 81 82 diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, 83 84 and giant cell foreign body reaction. 85 Although parenchymal lung injury predominated the cases reported, additional cases detailed episodes of status asthmaticus 86 and pneumothoraces 87 attributed to vaping. Non-respiratory vape pen injury has also been described, including cases of nicotine toxicity from vape solution ingestion, 88 89 and injuries sustained owing to vape pen device explosions. 90

The 2019 EVALI outbreak

In the summer of 2019 the EVALI outbreak led to 2807 cases of idiopathic acute lung injury in predominantly young, healthy individuals, which resulted in 68 deaths. 19 91 Epidemiological work to uncover the cause of the outbreak identified an association with vaping, particularly the use of THC-containing products, among affected individuals. CDC criteria for EVALI ( box 1 ) included individuals presenting with respiratory symptoms who had pulmonary infiltrates on imaging in the context of having vaped or dabbed within 90 days of symptom onset, without an alternative identifiable cause. 92 93 After peaking in September 2019, EVALI case numbers steadily declined, 91 likely owing to identification of a link with vaping, and subsequent removal of offending agents from circulation. Regardless, sporadic cases continue to be reported, and a high index of suspicion is required to differentiate EVALI from covid-19 pneumonia. 94 95 A strong association emerged between EVALI cases and the presence of vitamin E acetate in the BAL return of affected individuals 96 ; however, no definitive causal link has been established. Interestingly, the EVALI outbreak was nearly entirely contained within the US with the exception of several dozen cases, at least one of which was caused by an imported US product. 97 98 99 The pattern of cases and lung injury is most suggestive of a vape solution contaminant that was introduced into the distribution pipeline in US markets, leading to a geographically contained pattern of lung injury among users. CDC case criteria for EVALI may have obscured a potential link between viral pneumonia and EVALI, and cases may have been under-recognized following the onset of the covid-19 pandemic.

CDC criteria for establishing EVALI diagnosis

Cdc lung injury surveillance, primary case definitions, confirmed case.

Vape use* in 90 days prior to symptom onset; and

Pulmonary infiltrate on chest radiograph or ground glass opacities on chest computed tomography (CT) scan; and

Absence of pulmonary infection on initial investigation†; and

Absence of alternative plausible diagnosis (eg, cardiac, rheumatological, or neoplastic process).

Probable case

Pulmonary infiltrate on chest radiograph or ground glass opacities on chest CT; and

Infection has been identified; however is not thought to represent the sole cause of lung injury OR minimum criteria** to exclude infection have not been performed but infection is not thought to be the sole cause of lung injury

*Use of e-cigarette, vape pen, or dabbing.

†Minimum criteria for absence of pulmonary infection: negative respiratory viral panel, negative influenza testing (if supported by local epidemiological data), and all other clinically indicated infectious respiratory disease testing is negative.

EVALI—clinical, radiographic, and pathologic features

In the right clinical context, diagnosis of EVALI includes identification of characteristic radiographic and pathologic features. EVALI patients largely fit a pattern of diffuse, acute lung injury in the context of vape pen exposure. A systematic review of 200 reported cases of EVALI showed that those affected were predominantly men in their teens to early 30s, and most (80%) had been using THC-containing products. 100 Presentations included predominantly respiratory (95%), constitutional (87%), and gastrointestinal symptoms (73%). Radiological studies mostly featured diffuse ground glass opacities bilaterally. Of 92 cases that underwent BAL, alveolar fluid samples were most commonly neutrophil predominant, and 81% were additionally positive for LLM on Oil Red O staining. Lung biopsy was not required to achieve the diagnosis; however, of 33 cases that underwent tissue biopsy, common features included organizing pneumonia, inflammation, foamy macrophages, and fibrinous exudates.

EVALI—outcomes

Most patients with EVALI recovered, and prognosis was generally favorable. A systematic review of identified cases found that most patients with confirmed disease required admission to hospital (94%), and a quarter were intubated. 100 Mortality among EVALI patients was low, with estimates around 2-3% across multiple studies. 101 102 103 Mortality was associated with age over 35 and underlying asthma, cardiac disease, or mental health conditions. 103 Notably, the cohorts studied only included patients who presented for medical care, and the samples are likely biased toward a more symptomatic population. It is likely that many individuals experiencing mild symptoms of EVALI did not present for medical care, and would have self-discontinued vaping following extensive media coverage of the outbreak at that time. Although most EVALI survivors recovered well, case series of some individuals show persistent radiographic abnormalities 101 and sustained reductions in DLCO. 104 105 Pulmonary function evaluation of EVALI survivors showed normalization in FEV 1 /FVC on spirometry in some, 106 while others had more variable outcomes. 105 107 108

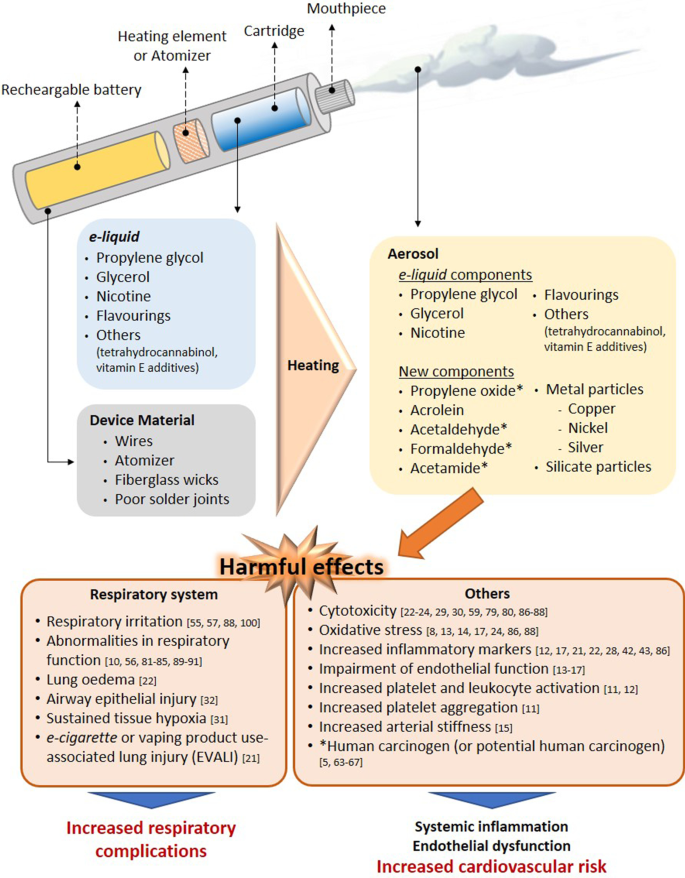

Vaping induced lung injury—pathophysiology

The causes underlying vaping related acute lung injury remain interesting to clinicians, scientists, and public health officials; multiple mechanisms of injury have been proposed and are summarized in figure 2 . 31 109 110 Despite increased scientific interest in vaping related lung injury following the EVALI outbreak, the pool of data from which to draw meaningful conclusions is limited because of small scale human studies and ongoing conflicts due to tobacco industry funding. 111 Further, insufficient time has elapsed since widespread vaping uptake, and available studies reflect the effects of vaping on lung health over a maximum 10-15 year timespan. The longitudinal effects of vaping may take decades to fully manifest and ongoing prospective work is required to better understand the impacts of vaping on respiratory health.

Schematic illustrating pathophysiology of vaping lung injury

Pro-inflammatory vape aerosol effects

While multiple pathophysiological pathways have been proposed for vaping related lung injury, they all center on the vape aerosol itself as the conduit of lung inflammation. Vape aerosols have been found to harbor a number of toxic substances, including thermal degradation products of the various vape solution components. 112 Mass spectrometry analysis of vape aerosols has identified a variety of oxidative and pro-inflammatory substances including benzene, acrolein, volatile organic compounds, and propylene oxide. 16 17 Vaping additionally leads to airway deposition of ultrafine particles, 14 113 as well as the heavy metals manganese and zinc which are emitted from the vaping coils. 15 114 Fourth generation vape pens allow for high wattage aerosol generation, which can cause airway epithelial injury and tissue hypoxia, 115 116 as well as formaldehyde exposure similar to that of cigarette smoke. 117 Common carrier solutions such as propylene glycol have been associated with increased airway hyper-reactivity among vape pen users, 31 118 119 and have been associated with chronic respiratory conditions among theater workers exposed to aerosolized propylene glycol used in the generation of artificial fog. 120 Nicotine salts used in pod based vape pen solutions, including Juul, have been found to penetrate the cell membrane and have cytotoxic effects. 121

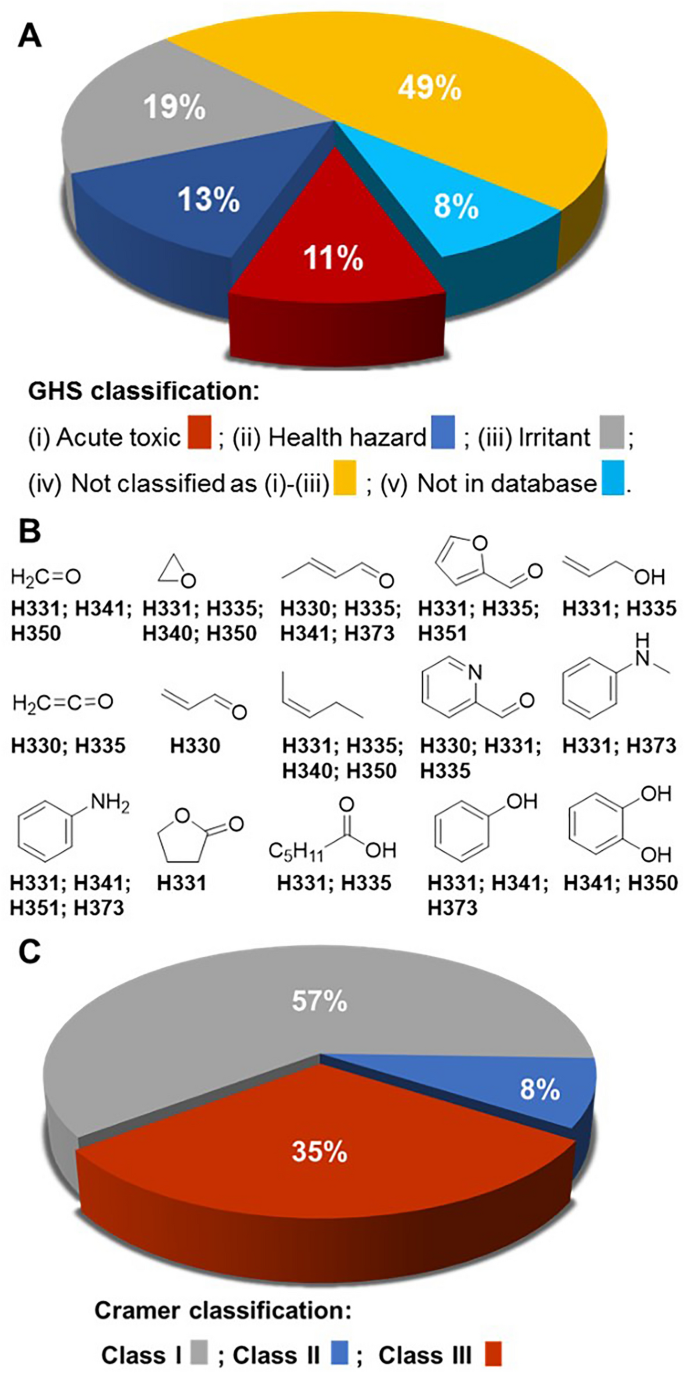

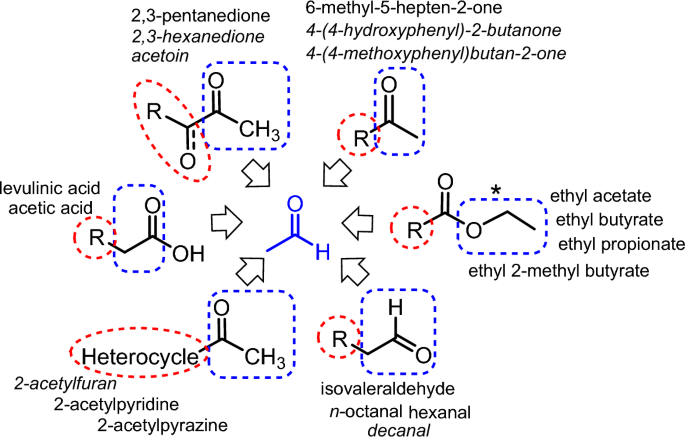

The myriad available vape pen flavors correlate with an expansive list of chemical compounds with potential adverse respiratory effects. Flavorants have come under increased scrutiny in recent years and have been found to contribute to the majority of aldehyde production during vape aerosol production. 122 Compounds such as cinnamaldehyde, 123 124 2,5-dimethylpyrazine (chocolate flavoring), 125 and 2,3-pentanedione 126 are common flavor additives and have been found to contribute to airway inflammation and altered immunological responses. The flavorant diacetyl garnered particular attention after it was identified on mass spectrometry in most vape solutions tested. 127 Diacetyl is most widely associated with an outbreak of diacetyl associated bronchiolitis obliterans (“popcorn lung”) among workers at a microwave popcorn plant in 2002. 128 Identification of diacetyl in vape solutions raises the possibility of development of a similar pattern of bronchiolitis obliterans among individuals who have chronic vape aerosol exposure to diacetyl-containing vape solutions. 129

Studies of vape aerosols have suggested multiple pro-inflammatory effects on the respiratory system. This includes increased airway resistance, 130 impaired response to infection, 131 and impaired mucociliary clearance. 132 Vape aerosols have further been found to induce oxidative stress in lung epithelial cells, 133 and to both induce DNA damage and impair DNA repair, consistent with a potential carcinogenic effect. 134 Mice chronically exposed to vape aerosols developed increased airway hyper-reactivity and parenchymal changes consistent with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 135 Human studies have been more limited, but reveal increased airway edema and friability among vape pen users, as well as altered gene transcription and decreased innate immunity. 136 137 138 Upregulation of neutrophil elastase and matrix metalloproteases among vape users suggests increased proteolysis, potentially putting those patients at risk of chronic respiratory conditions. 139

THC-containing products

Of particular interest during the 2019 EVALI outbreak was the high prevalence of THC use among EVALI cases, 19 raising questions about a novel mechanism of lung injury specific to THC-containing vape solutions. These solutions differ from conventional nicotine based products because of the need for a carrier capable of emulsifying the lipid based THC component. In this context, additional vape solution ingredients rose to attention as potential culprits—namely, THC itself, which has been found to degrade to methacrolein and benzene, 140 as well as vitamin E acetate which was found to be a common oil based diluent. 141

Vitamin E acetate has garnered increasing attention as a potential culprit in the pathophysiology of the EVALI outbreak. Vitamin E acetate was found in 94% of BAL samples collected from EVALI patients, compared with none identified in unaffected vape pen users. 96 Thermal degradation of vitamin E acetate under conditions similar to those in THC vape pens has shown production of ketene, alkene, and benzene, which may mediate epithelial lung injury when inhaled. 39 Previous work had found that vitamin E acetate impairs pulmonary surfactant function, 142 and subsequent studies have shown a dose dependent adverse effect on lung parenchyma by vitamin E acetate, including toxicity to type II pneumocytes, and increased inflammatory cytokines. 143 Mice exposed to aerosols containing vitamin E acetate developed LLM and increased alveolar protein content, suggesting epithelial injury. 140 143

The pathophysiological insult underlying vaping related lung injury may be multitudinous, including potentially compound effects from multiple ingredients comprising a vape aerosol. The heterogeneity of available vape solutions on the market further complicates efforts to pinpoint particular elements of the vape aerosol that may be pathogenic, as no two users are likely to be exposed to the same combination of vape solution products. Further, vape users may be exposed to vape solutions containing terpenes, medium chain triglycerides, or coconut oil, the effects of which on respiratory epithelium remain under investigation. 144

Lipid laden macrophages

Lipid laden alveolar macrophages have risen to prominence as potential markers of vaping related lung injury. Alveolar macrophages describe a scavenger white blood cell responsible for clearing alveolar spaces of particulate matter and modulating the inflammatory response in the lung parenchyma. 145 LLM describe alveolar macrophages that have phagocytosed fat containing deposits, as seen on Oil Red O staining, and have been described in a wide variety of pulmonary conditions, including aspiration, lipoid pneumonia, organizing pneumonia, and medication induced pneumonitis. 146 147 During the EVALI outbreak, LLM were identified in the alveolar spaces of affected patients, both in the BAL fluid and on both transbronchial and surgical lung biopsies. 148 149 Of 52 EVALI cases reported in the literature who underwent BAL, LLM were identified in over 80%. 19 100 101 148 149 150 151 152 153 Accordingly, attention turned to LLM as not only a potential marker of lung injury in EVALI, but as a possible contributor to lung inflammation itself. This concern was compounded by the frequent reported use of oil based THC vape products among EVALI patients, raising the possibility of lipid deposits in the alveolus resulting from inhalation of THC-containing vape aerosols. 154 The combination of LLM, acute lung injury, and inhalational exposure to an oil based substance raised the concern for exogenous lipoid pneumonia. 152 153 However, further evaluation of the radiographic and histopathologic findings failed to identify cardinal features that would support a diagnosis of exogenous lipoid pneumonia—namely, low attenuation areas on CT imaging and foreign body giant cells on histopathology. 155 156 However, differences in the particle size and distribution between vape aerosol exposure and traditional causes of lipoid pneumonia (ie, aspiration of a large volume of an oil-containing substance), could reasonably lead to differences in radiographic appearance, although this would not account for the lack of characteristic histopathologic features on biopsy that would support a diagnosis of lipoid pneumonia.

Recent work suggests that LLM reflect a non-specific marker of vaping, rather than a marker of lung injury. One study found that LLM were not unique to EVALI and could be identified in healthy vape pen users, as well as conventional cigarette smokers, but not in never smokers. 157 Interestingly, this work showed increased cytokines IL-4 and IL-10 among healthy vape users, suggesting that cigarette and vape pen use are associated with a pro-inflammatory state in the lung. 157 An alternative theory supports LLM presence reflecting macrophage clearance of intra-alveolar cell debris rather than exogenous lipid exposure. 149 150 Such a pattern would be in keeping with the role of alveolar macrophages as modulating the inflammatory response in the lung parenchyma. 158 Taken together, available data would support LLM serving as a non-specific marker of vape product use, rather than playing a direct role in vaping related lung injury pathogenesis. 102

Clinical aspects

A high index of suspicion is required in establishing a diagnosis of vaping related lung injury, and a general approach is summarized in figure 3 . Clinicians may consider the diagnosis when faced with a patient with new respiratory symptoms in the context of vape pen use, without an alternative cause to account for their symptoms. Suspicion should be especially high if respiratory complaints are coupled with constitutional and gastrointestinal symptoms. Patients may present with non-specific markers indicative of an ongoing inflammatory process: fevers, leukocytosis, elevated C reactive protein, or elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. 19

Flowchart outlining the procedure for diagnosing a vaping related lung injury

Vaping related lung injury is a diagnosis of exclusion. Chest imaging via radiograph or CT may identify a variety of patterns, although diffuse ground glass opacities remain the most common radiographic finding. Generally, patients with an abnormal chest radiograph should undergo a chest CT for further evaluation of possible vaping related lung injury.

Exclusion of infectious causes is recommended. Testing should include evaluation for bacterial and viral causes of pneumonia, as deemed appropriate by clinical judgment and epidemiological data. Exclusion of common viral causes of pneumonia is imperative, particularly influenza and SARS-CoV-2. Bronchoscopy with BAL should be considered on a case-by-case basis for those with more severe disease and may be helpful to identify patients with vaping mediated eosinophilic lung injury. Further, lung biopsy may be beneficial to exclude alternative causes of lung injury in severe cases. 92

No definitive therapy has been identified for the treatment of vaping related lung injury, and data are limited to case reports and public health guidance on the topic. Management includes supportive care and strong consideration for systemic corticosteroids for severe cases of vaping related lung injury. CDC guidance encourages consideration of systemic corticosteroids for patients requiring admission to hospital, or those with higher risk factors for adverse outcomes, including age over 50, immunosuppressed status, or underlying cardiopulmonary disease. 100 Further, given case reports of vaping mediated acute eosinophilic pneumonia, steroids should be implemented in those patients who have undergone a confirmatory BAL. 77 79

Additional therapeutic options include empiric antibiotics and/or antivirals, depending on the clinical scenario. For patients requiring admission to hospital, prompt subspecialty consultation with a pulmonologist can help guide management. Outpatient follow-up with chest imaging and spirometry is recommended, as well as referral to a pulmonologist. Counseling regarding vaping cessation is also a core component in the post-discharge care for this patient population. Interventions specific to vaping cessation remain under investigation; however, literature supports the use of behavioral counseling and/or pharmacotherapy to support nicotine cessation efforts. 66

Health outcomes among vape pen users

Health outcomes among chronic vape pen users remains an open question. To date, no large scale prospective cohort studies exist that can establish a causal link between vape use and adverse respiratory outcomes. One small scale prospective cohort study did not identify any spirometric or radiographic changes among vape pen users over a 3.5 year period. 159 Given that vaping remains a relatively novel phenomenon, many users will have a less than 10 “pack year” history of vape pen use, arguably too brief an exposure period to reflect the potential harmful nature of chronic vaping. Studies encompassing a longer period of observation of vape pen users have not yet taken place, although advances in electronic medical record (EMR) data collection on vaping habits make such work within reach.

Current understanding of the health effects of vaping is largely limited to case reports of acute lung injury, and health surveys drawing associations between vaping exposure and patient reported outcomes. Within these limitations, however, early work suggests a correlation between vape pen use and poorer cardiopulmonary outcomes. Survey studies of teens who regularly vape found increased frequencies of respiratory symptoms, including productive cough, that were independent of smoking status. 160 161 These findings were corroborated in a survey series identifying more severe asthma symptoms and more days of school missed owing to asthma among vape pen users, regardless of cigarette smoking status. 162 163 164 Studies among adults have shown a similar pattern, with increased prevalence of chronic respiratory conditions (ie, asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) among vape pen users, 165 166 and higher risk of myocardial infarction and stroke, but lower risk of diabetes. 167

The effects of vaping on lung function as determined by spirometric studies are more varied. Reported studies have assessed lung function after a brief exposure to vape aerosols, varying from 5-60 minutes in duration, and no longer term observational cohort studies exist. While some studies have shown increased airway resistance after vaping exposure, 130 168 169 others have shown no change in lung function. 137 170 171 The cumulative exposure of habitual vape pen users to vape aerosols is much longer than the period evaluated in these studies, and the impact of vaping on longer term respiratory heath remains to be seen. Recent work evaluating ventilation-perfusion matching among chronic vapers compared with healthy controls found increased ventilation-perfusion mismatch, despite normal spirometry in both groups. 172 Such work reinforces the notion that changes in spirometry are a feature of more advanced airways disease, and early studies, although inconsistent, may foreshadow future respiratory impairment in chronic vapers.

Covid-19 and vaping

The covid-19 pandemic brought renewed attention to the potential health impacts of vaping. Studies investigating the role of vaping in covid-19 prevalence and outcomes have been limited by the small size of the populations studied and results have been inconsistent. Early work noted a geographic association in the US between vaping prevalence and covid-19 cases, 173 and a subsequent survey study found that a covid-19 diagnosis was five times more likely among teens who had ever vaped. 174 In contrast, a UK survey study found no association between vaping status and covid-19 infection rates, although captured a much smaller population of vape pen users. 175 Reports of nicotine use upregulating the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptor, 176 which serves as the binding site for SARS-CoV-2 entry, raised the possibility of increased susceptibility to covid-19 among chronic nicotine vape pen users. 177 178 Further, vape use associated with sharing devices and frequent touching of the mouth and face were posited as potential confounders contributing to increased prevalence of covid-19 in this population. 179

Covid-19 outcomes among chronic vape pen users remain an open question. While smoking has been associated with progression to more severe infections, 180 181 no investigation has been performed to date among vaping cohorts. The young average age of chronic vape pen users may prove a protective factor, as risk of severe covid-19 infection has been shown to increase with age. 182 Regardless, a prudent recommendation remains to abstain from vaping to mitigate risk of progression to severe covid-19 infection. 183

Increased awareness of respiratory health brought about by covid-19 and EVALI is galvanizing the changing patterns in vape pen use. 184 Survey studies have consistently shown trends toward decreasing use among adolescents and young adults. 174 185 186 In one study, up to two thirds of participants endorsed decreasing or quitting vaping owing to a combination of factors including difficulty purchasing vape products during the pandemic, concerns about vaping effects on lung health, and difficulty concealing vape use while living with family. 174 Such results are reflected in nationwide trends that show halting growth in vaping use among high school students. 8 These trends are encouraging in that public health interventions countering nicotine use among teens may be meeting some measure of success.

Clinical impact—collecting and recording a vaping history

Vaping history in electronic medical records.

Efforts to prevent, diagnose, and treat vaping related lung injury begin with the ability of our healthcare system to identify vape users. Since vaping related lung injury remains a diagnosis of exclusion, clinicians must have a high index of suspicion when confronted with idiopathic lung injury in a patient with vaping exposure. Unlike cigarette use, vape pen use is not built into most EMR systems, and is not included in meaningful use criteria for EMRs. 187 Retrospective analysis of outpatient visits showed that a vaping history was collected in less than 0.1% of patients in 2015, 188 although this number has been increasing. 189 190 In part augmented by EMR frameworks that prompt collection of data on vaping history, more recent estimates indicate that a vaping history is being collected in up to 6% of patients. 191 Compared with the widespread use of vaping, particularly among adolescent and young adult populations, this number remains low. Considering generational trends in nicotine use, vaping will likely eventually overcome cigarettes as the most common mode of nicotine use, raising the importance of collecting a vaping related history. Further, EMR integration of vaping history is imperative to allow for retrospective, large scale analyses of vape exposure on longitudinal health outcomes at a population level.

Practical considerations—gathering a vaping history

As vaping becomes more common, the clinician’s ability to accurately collect a vaping history and identify patients who may benefit from nicotine cessation programs becomes more important. Reassuringly, gathering a vaping history is not dissimilar to asking about smoking and use of other tobacco products, and is summarized in box 2 . Collecting a vaping history is of particular importance for providers caring for adolescents and young adults who are among the highest risk demographics for vape pen use. Adolescents and young adults may be reluctant to share their vaping history, particularly if they are using THC-containing or CBD-containing vape solutions. Familiarity with vernacular terms to describe vaping, assuming a non-judgmental approach, and asking parents or guardians to step away during history taking will help to break down these barriers. 192

Practical guide to collecting a vaping history

Ask with empathy.

Young adults may be reluctant to share history of vaping use. Familiarity with vaping terminology, asking in a non-judgmental manner, and asking in a confidential space may help.

Ask what they are vaping

Vape products— vape pens commonly contain nicotine or an alternative active ingredient, such as THC or CBD. Providers may also inquire about flavorants, or other vape solution additives, that their patient is consuming, particularly if vaping related lung injury is suspected.

Source— ask where they source their product from. Sources may include commercially available products, third party distributors, or friends or local contacts.

Ask how they are vaping

Device— What style of device are they using?

Frequency— How many times a day do they use their vape pen (with frequent use considered >5 times a day)? Alternatively, providers may inquire how long it takes to deplete a vape solution cartridge (with use of one or more pods a day considered heavy use).

Nicotine concentration— For individuals consuming nicotine-containing products, clinicians may inquire about concentration and frequency of use, as this may allow for development of a nicotine replacement therapy plan.

Ask about other inhaled products

Clinicians should ask patients who vape about use of other inhaled products, particularly cigarettes. Further, clinicians may ask about use of water pipes, heat-not-burn devices, THC-containing products, or dabbing.

The following provides a practical guide on considerations when collecting a vaping history. Of note, collecting a partial history is preferable to no history at all, and simply recording whether a patient is vaping or not adds valuable information to the medical record.

Vape use— age at time of vaping onset and frequency of vape pen use. Vape pen use >5 times a day would be considered frequent. Alternatively, clinicians may inquire how long it takes to deplete a vape solution pod (use of one or more pods a day would be considered heavy use), or how frequently users are refilling their vape pens for refillable models.

Vape products— given significant variation in vape solutions available on the market, and variable risk profiles of the multitude of additives, inquiring as to which products a patient is using may add useful information. Further, clinicians may inquire about use of nicotine versus THC-containing vape solutions, and whether said products are commercially available or are customized by third party sellers.

Concurrent smoking— simultaneous use of multiple inhaled products is common among vape users, including concurrent use of conventional cigarettes, water pipes, heat-not-burn devices, and THC-containing or CBD-containing products. Among those using marijuana products, gathering a history regarding the type of product use, the device, and the modality of aerosol generation may be warranted. Gathering such detailed information may be challenging in the face of rapidly evolving product availability and changing popular terminology. Lastly, clinicians may wish to inquire about “dabbing”—the practice of inhaling heated butane hash oil, a concentrated THC wax—which may also be associated with lung injury. 193

Future directions

Our understanding of the effects of vaping on respiratory health is in its early stages and multiple trials are under way. Future work requires enhanced understanding of the effects of vape aerosols on lung biology, such as ongoing investigations into biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation among vape users (clinicaltrials.gov NCT03823885 ). Additional studies seek to elucidate the relation between vape aerosol exposure and cardiopulmonary outcomes among vape pen users ( NCT03863509 , NCT05199480 ), while an ongoing prospective cohort study will allow for longitudinal assessment of airway reactivity and spirometric changes among chronic vape pen users ( NCT04395274 ).

Public health and policy interventions are vital in supporting both our understanding of vaping on respiratory health and curbing the vaping epidemic among teens. Ongoing, large scale randomized controlled studies seek to assess the impact of the FDA’s “The Real Cost” advertisement campaign for vaping prevention ( NCT04836455 ) and another trial is assessing the impact of a vaping prevention curriculum among adolescents ( NCT04843501 ). Current trials are seeking to understand the potential for various therapies as tools for vaping cessation, including nicotine patches ( NCT04974580 ), varenicline ( NCT04602494 ), and text message intervention ( NCT04919590 ).

Finally, evaluation of vaping as a potential tool for harm reduction among current cigarette smokers is undergoing further evaluation ( NCT03235505 ), which will add to the body of work and eventually lead to clear policy guidance.

Several guidelines on the management of vaping related lung injury have been published and are summarized in table 1 . 194 195 196 Given the relatively small number of cases, the fact that vaping related lung injury remains a newer clinical entity, and the lack of clinical trials on the topic, guideline recommendations reflect best practices and expert opinion. Further, published guidelines focus on the diagnosis and management of EVALI, and no guidelines exist to date for the management of vaping related lung injury more generally.

Summary of clinical guidelines

- View inline

Conclusions

Vaping has grown in popularity internationally over the past decade, in part propelled by innovations in vape pen design and nicotine flavoring. Teens and young adults have seen the biggest uptake in use of vape pens, which have superseded conventional cigarettes as the preferred modality of nicotine consumption. Despite their widespread popularity, relatively little is known about the potential effects of chronic vaping on the respiratory system, and a growing body of literature supports the notion that vaping is not without risk. The 2019 EVALI outbreak highlighted the potential harms of vaping, and the consequences of long term use remain unknown.

Discussions regarding the potential harms of vaping are reminiscent of scientific debates about the health effects of cigarette use in the 1940s. Interesting parallels persist, including the fact that only a minority of conventional cigarette users develop acute lung injury, yet the health impact of sustained, longitudinal cigarette use is unquestioned. The true impact of vaping on respiratory health will manifest over the coming decades, but in the interval a prudent and time tested recommendation remains to abstain from consumption of inhaled nicotine and other products.

Questions for future research

How does chronic vape aerosol exposure affect respiratory health?

Does use of vape pens affect respiratory physiology (airway resistance, V/Q matching, etc) in those with underlying lung disease?

What is the role for vape pen use in promoting smoking cessation?

What is the significance of pulmonary alveolar macrophages in the pathophysiology of vaping related lung injury?

Are particular populations more susceptible to vaping related lung injury (ie, by sex, demographic, underlying comorbidity, or age)?

Series explanation: State of the Art Reviews are commissioned on the basis of their relevance to academics and specialists in the US and internationally. For this reason they are written predominantly by US authors

Contributors: AJ conceived of, researched, and wrote the piece. She is the guarantor.

Competing interests: I have read and understood the BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: AJ receives consulting fees from DawnLight, Inc for work unrelated to this piece.

Patient involvement: No patients were directly involved in the creation of this article.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- ↵ US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. 2014. doi: 10.1037/e510072014-001 .

- Cornelius ME ,

- Loretan CG ,

- Marshall TR

- Fetterman JL ,

- Benjamin EJ ,

- Barrington-Trimis JL ,

- Leventhal AM ,

- Cullen KA ,

- Gentzke AS ,

- Sawdey MD ,

- ↵ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surgeon General’s Advisory on E-cigarette Use Among Youth. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/surgeon-general-advisory/index.html

- Leventhal A ,

- Johnston L ,

- O’Malley PM ,

- Patrick ME ,

- Barrington-Trimis J

- ↵ Foundation for a Smoke-Free World https://www.smokefreeworld.org/published_reports/

- Kaisar MA ,

- Calfee CS ,

- Matthay MA ,

- ↵ Royal College of Physicians (London) & Tobacco Advisory Group. Nicotine without smoke: tobacco harm reduction: a report. 2016. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/nicotine-without-smoke-tobacco-harm-reduction

- ↵ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. 2018. doi: 10.17226/24952 OpenUrl CrossRef

- Manigrasso M ,

- Buonanno G ,

- Stabile L ,

- Agnihotri R

- LeBouf RF ,

- Koutrakis P ,

- Christiani DC

- Perrine CG ,

- Pickens CM ,

- Boehmer TK ,

- Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Group

- Layden JE ,

- Esposito S ,

- Spindle TR ,

- Eissenberg T ,

- Kendler KS ,

- McCabe SE ,

- ↵ Joseph R. Electric vaporizer. 1930.

- ↵ Gilbert HA. Smokeless non-tobacco cigarette. 1965.

- ↵ An Interview With A 1970’s Vaping Pioneer. Ashtray Blog. 2015 . https://www.ecigarettedirect.co.uk/ashtray-blog/2014/06/favor-cigarette-interview-dr-norman-jacobson.html (2014).

- Benowitz N ,

- ↵ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, & Committee on the Review of the Health Effects of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes . (National Academies Press (US), 2018).

- ↵ Tolentino J. The Promise of Vaping and the Rise of Juul. The New Yorker . 2018 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/05/14/the-promise-of-vaping-and-the-rise-of-juul

- ↵ Bowen A, Xing C. Nicotine salt formulations for aerosol devices and methods thereof. 2014.

- Madden DR ,

- McConnell R ,

- Gammon DG ,

- Marynak KL ,

- ↵ Jackler RK, Chau C, Getachew BD, et al. JUUL Advertising Over its First Three Years on the Market. Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising, Stanford University School of Medicine. 2019. https://tobacco-img.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/21231836/JUUL_Marketing_Stanford.pdf

- Prochaska JJ ,

- ↵ Richtel M, Kaplan S. Juul May Get Billions in Deal With One of World’s Largest Tobacco Companies. The New York Times . 2018.

- ↵ Truth Initiative. Vaping Lingo Dictionary: A guide to popular terms and devices. 2020. https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/emerging-tobacco-products/vaping-lingo-dictionary

- Williams M ,

- Pepper JK ,

- MacMonegle AJ ,

- Nonnemaker JM

- ↵ The Physics of Vaporization. Jupiter Research. 2020. https://www.jupiterresearch.com/physics-of-vaporization/

- Bonnevie E ,

- ↵ National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538680/

- Trivers KF ,

- Phillips E ,

- Stefanac S ,

- Sandner I ,

- Grabovac I ,

- ↵ Knowledge-Action-Change. Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020. 2020. https://gsthr.org/resources/item/burning-issues-global-state-tobacco-harm-reduction-2020

- Creamer MR ,

- Park-Lee E ,

- Gorukanti A ,

- Delucchi K ,

- Fisher-Travis R ,

- Halpern-Felsher B

- Amrock SM ,

- ↵ Buy JUUL Products | Shop All JUULpods, JUUL Devices, and Accessories | JUUL. https://www.juul.com/shop

- Schiff SJ ,

- Kechter A ,

- Simpson KA ,

- Ceasar RC ,

- Braymiller JL ,

- Barrington-Trimis JL

- Moustafa AF ,

- Rodriguez D ,

- Audrain-McGovern J

- Berhane K ,

- Stjepanović D ,

- Hitchman SC ,

- Bakolis I ,

- Plurphanswat N

- Warner KE ,

- Cummings KM ,

- ↵ FDA finalizes enforcement policy on unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes that appeal to children, including fruit and mint. FDA . 2020 . https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-finalizes-enforcement-policy-unauthorized-flavored-cartridge-based-e-cigarettes-appeal-children

- ↵ Henderson, E. E-cigarettes: an evidence update. 113.

- Hartmann-Boyce J ,

- McRobbie H ,

- Lindson N ,

- Phillips-Waller A ,

- ↵ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Electronic Cigarettes. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/index.htm l

- Patnode CD ,

- Henderson JT ,

- Thompson JH ,

- Senger CA ,

- Fortmann SP ,

- Whitlock EP

- Kmietowicz Z

- ↵ World Health Organization. E-cigarettes are harmful to health. 2020. https://www.who.int/news/item/05-02-2020-e-cigarettes-are-harmful-to-health

- Lachireddy K ,

- Sleiman M ,

- Montesinos VN ,

- Kalkhoran S ,

- Filion KB ,

- Kimmelman J ,

- Eisenberg MJ

- McCauley L ,

- Aoshiba K ,

- Nakamura H ,

- Wiggins A ,

- Hudspath C ,

- Kisling A ,

- Hostler DC ,

- Sommerfeld CG ,

- Weiner DJ ,

- Mantilla RD ,

- Darnell RT ,

- Khateeb F ,

- Agustin M ,

- Yamamoto M ,

- Cabrera F ,

- ↵ Long. Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage Due to Electronic Cigarette Use | A54. CRITICAL CARE CASE REPORTS: ACUTE HYPOXEMIC RESPIRATORY FAILURE/ARDS. https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2016.193.1_MeetingAbstracts.A1862

- Ring Madsen L ,

- Vinther Krarup NH ,

- Bergmann TK ,

- Bradford LE ,

- Rebuli ME ,

- Jaspers I ,

- Clement KC ,

- Loughlin CE

- Bonilla A ,

- Alamro SM ,

- Bassett RA ,

- Osterhoudt K ,

- Slaughter J ,

- ↵ Health CO. on S. and. Smoking and Tobacco Use; Electronic Cigarettes. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html (2019).

- ↵ For State, Local, Territorial, and Tribal Health Departments | Electronic Cigarettes | Smoking & Tobacco Use | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease/health-departments/index.html (2019).

- ↵ 2019 Lung Injury Surveillance Primary Case Definitions. 2.

- Callahan SJ ,

- Collingridge DS ,

- Armatas C ,

- Heinzerling A ,

- Blount BC ,

- Karwowski MP ,

- Shields PG ,

- Lung Injury Response Laboratory Working Group

- ↵ Government of Canada. Vaping-associated lung illness. 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/vaping-pulmonary-illness.html (2020).

- Marlière C ,

- De Greef J ,

- Casanova GS ,

- Blagev DP ,

- Guidry DW ,

- Grissom CK ,

- Werner AK ,

- Koumans EH ,

- Chatham-Stephens K ,

- Lung Injury Response Mortality Working Group

- Tsirilakis K ,

- Yenduri NJS ,

- Guillerman RP ,

- Anderson B ,

- Serajeddini H ,

- Knipping D ,

- Brasky TM ,

- Pisinger C ,

- Godtfredsen N ,

- Jensen RP ,

- Pankow JF ,

- Strongin RM ,

- Lechasseur A ,

- Altmejd S ,

- Turgeon N ,

- Goessler W ,

- Chaumont M ,

- van de Borne P ,

- Bernard A ,

- Kosmider L ,

- Sobczak A ,

- Aldridge K ,

- Afshar-Mohajer N ,

- Koehler K ,

- Varughese S ,

- Teschke K ,

- van Netten C ,

- Beyazcicek O ,

- Onyenwoke RU ,

- Khlystov A ,

- Samburova V

- Lavrich KS ,

- van Heusden CA ,

- Lazarowski ER ,

- Carson JL ,

- Pawlak EA ,

- Lackey JT ,

- Sherwood CL ,

- O’Sullivan M ,

- Vallarino J ,

- Flanigan SS ,

- LeBlanc M ,

- Kullman G ,

- Simoes EJ ,

- Wambui DW ,

- Vardavas CI ,

- Anagnostopoulos N ,

- Kougias M ,

- Evangelopoulou V ,

- Connolly GN ,

- Behrakis PK

- Sussan TE ,

- Gajghate S ,

- Thimmulappa RK ,

- Hossain E ,

- Perveen Z ,

- Lerner CA ,

- Sundar IK ,

- Garcia-Arcos I ,

- Geraghty P ,

- Baumlin N ,

- Coakley RC ,

- Mascenik T ,

- Staudt MR ,

- Hollmann C ,

- Radicioni G ,

- Coakley RD ,

- Kalathil SG ,

- Bogner PN ,

- Goniewicz ML ,

- Thanavala YM

- Massey JB ,

- Matsumoto S ,

- Traber MG ,

- Ranpara A ,

- Stefaniak AB ,

- Williams K ,

- Fernandez E ,

- Basset-Léobon C ,

- Lacoste-Collin L ,

- Courtade-Saïdi M

- Boland JM ,

- Maddock SD ,

- Cirulis MM ,

- Tazelaar HD ,

- Mukhopadhyay S ,

- Dammert P ,

- Kalininskiy A ,

- Davidson K ,

- Brancato A ,

- Heetderks P ,

- Dicpinigaitis PV ,

- Trachuk P ,

- Suhrland MJ

- Khilnani GC

- Simmons A ,

- Freudenheim JL ,

- Hussell T ,

- Cibella F ,

- Caponnetto P ,

- Schweitzer RJ ,

- Williams RJ ,

- Vindhyal MR ,

- Munguti C ,

- Vindhyal S ,

- Lappas AS ,

- Tzortzi AS ,

- Konstantinidi EM ,

- Antoniewicz L ,

- Brynedal A ,

- Lundbäck M ,

- Ferrari M ,

- Boulay MÈ ,

- Boulet LP ,

- Morissette MC

- Kizhakke Puliyakote AS ,

- Elliott AR ,

- Anderson KM ,

- Crotty Alexander LE ,

- Jackson SE ,

- McAlinden KD ,

- McKelvey K ,

- Patanavanich R ,

- NVSS - Provisional Death Counts for COVID-19 - Executive Summary

- Sokolovsky AW ,

- Hertel AW ,

- Micalizzi L ,

- Klemperer EM ,

- Peasley-Miklus C ,

- Villanti AC

- Henricks WH

- Young-Wolff KC ,

- Klebaner D ,

- Mowery DL ,

- Don’t Forget to Ask

- Stephens D ,

- Siegel DA ,

- Jatlaoui TC ,

- Lung Injury Response Clinical Working Group ,

- Ramalingam SS ,

- Schuurmans MM

Jump to navigation

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Malaysia

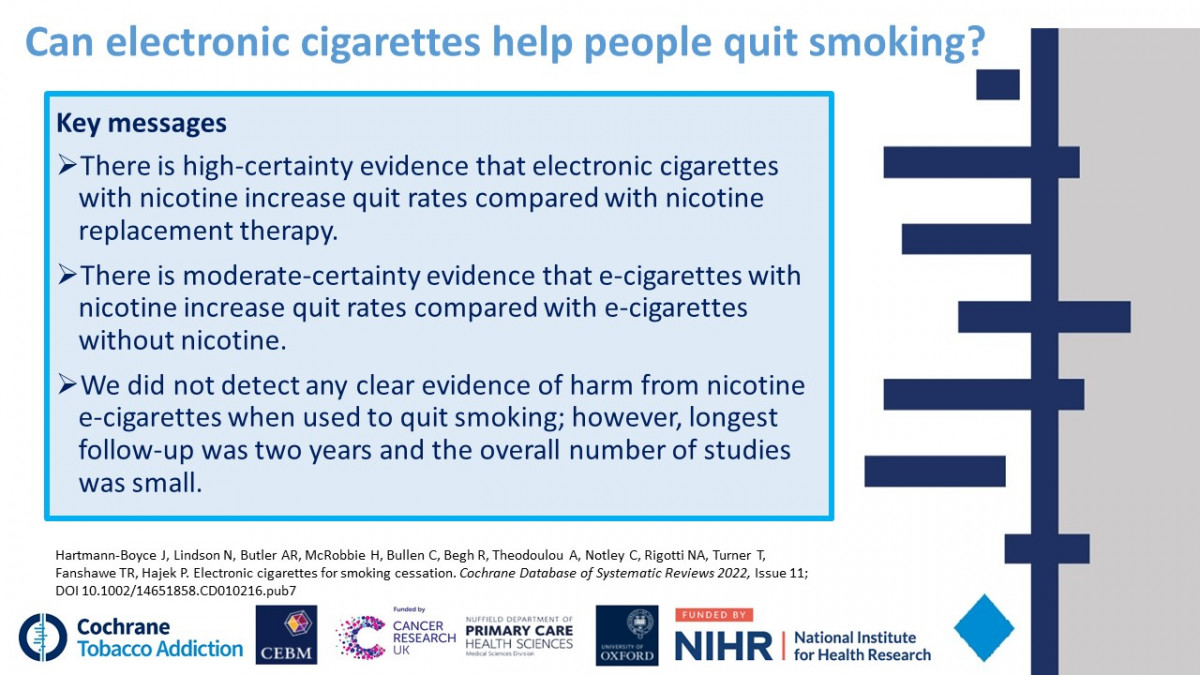

Latest Cochrane Review finds high certainty evidence that nicotine e-cigarettes are more effective than traditional nicotine-replacement therapy (NRT) in helping people quit smoking

A Cochrane review has found the strongest evidence yet that e-cigarettes, also known as ‘vapes’, help people to quit smoking better than traditional nicotine replacement therapies, such as patches and chewing gums.

New evidence published today in the Cochrane Library finds high certainty evidence that people are more likely to stop smoking for at least six months using nicotine e-cigarettes, or ‘vapes’, than using nicotine replacement therapies, such as patches and gums. Evidence also suggested that nicotine e-cigarettes led to higher quit rates than e-cigarettes without nicotine, or no stop smoking intervention, but less data contributed to these analyses. The updated Cochrane review includes 78 studies in over 22,000 participants – an addition of 22 studies since the last update in 2021.

Smoking is a significant global health problem. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), in 2020, 22.3% of the global population used tobacco, despite it killing up to half of its users. Stopping smoking reduces the risk of lung cancer, heart attacks and many other diseases. Though most people who smoke want to quit, many find it difficult to do so permanently. Nicotine patches and gum are safe, effective and widely used methods to help individuals quit.

E-cigarettes heat liquids with nicotine and flavourings, allowing users to ‘vape’ nicotine instead of smoking. Data from the review showed that i f six in 100 people quit by using nicotine replacement therapy, eight to twelve would quit by using electronic cigarettes containing nicotine. This means an additional two to six people in 100 could potentially quit smoking with nicotine containing electronic cigarettes.

Dr Jamie Hartmann-Boyce, Associate Professor at the University of Oxford, Editor of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group, and an author of the new publication, said:

“Electronic cigarettes have generated a lot of misunderstanding in both the public health community and the popular press since their introduction over a decade ago. These misunderstandings discourage some people from using e-cigarettes as a stop smoking tool. Fortunately, more and more evidence is emerging and provides further clarity. With support from Cancer Research UK, we search for new evidence every month as part of a living systematic review. We identify and combine the strongest evidence from the most reliable scientific studies currently available. For the first time, this has given us high-certainty evidence that e-cigarettes are even more effective at helping people to quit smoking than traditional nicotine replacement therapies, like patches or gums.”

In studies comparing nicotine e-cigarettes to nicotine replacement treatment, significant side effects were rare. In the short-to-medium term (up to two years), nicotine e-cigarettes most typically caused throat or mouth irritation, headache, cough, and feeling nauseous. However, these effects appeared to diminish over time.

Dr Nicola Lindson, University Research Lecturer at the University of Oxford, Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group’s Managing Editor, and author of the publication said:

“ E-cigarettes do not burn tobacco; and as such they do not expose users to the same complex mix of chemicals that cause diseases in people smoking conventional cigarettes. E-cigarettes are not risk free, and shouldn’t be used by people who don’t smoke or aren’t at risk of smoking. However, evidence shows that nicotine e-cigarettes carry only a small fraction of the risk of smoking. In our review, we did not find evidence of substantial harms caused by nicotine containing electronic cigarettes when used to quit smoking. However, due to the small number of studies and lack of data on long-term nicotine-containing electronic cigarette usage – usage over more than two years – questions remain about long-term effects.”

The researchers conclude that more evidence, particularly about the effects of newer e-cigarettes with better nicotine delivery than earlier ones, is needed to assist more people quit smoking. Longer-term data is also needed.

Michelle Mitchell, chief executive at Cancer Research UK, said:

“We welcome this report which adds to a growing body of evidence showing that e-cigarettes are an effective smoking cessation tool. We strongly discourage those who have never smoked from using e-cigarettes, especially young people. This is because they are a relatively new product and we don’t yet know the long term health effects. While the long term effects of vaping are still unknown, the harmful effects of smoking are indisputable – smoking causes around 55,000 cancer deaths in the UK every year. Cancer Research UK supports balanced evidence-based regulation on e-cigarettes from UK governments which maximises their potential to help people stop smoking, whilst minimising the risk of uptake among others.”

- Read the full Cochrane review and plain language summary

- Learn more about Cochrane Tobacco Addition Group

- Science Media Centre: Expert reaction to cochrane review on electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation

Hartmann-Boyce J, Lindson N, Butler AR, McRobbie H, Bullen C, Begh R, Theodoulou A, Notley C, Rigotti NA, Turner T, Fanshawe TR, Hajek P. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2022, Issue 11. Art. No.: CD010216. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub7

This work was supported by Cancer Research UK [A ref. A29845]

To speak to a team member about this project please contact Dr. Hartmann-Boyce, [email protected] or Dr. Lindson, [email protected] .

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

News releases.

News Release

Wednesday, October 26, 2022

NIH-funded studies show damaging effects of vaping, smoking on blood vessels

Combining e-cigarettes with regular cigarettes may increase health risks.

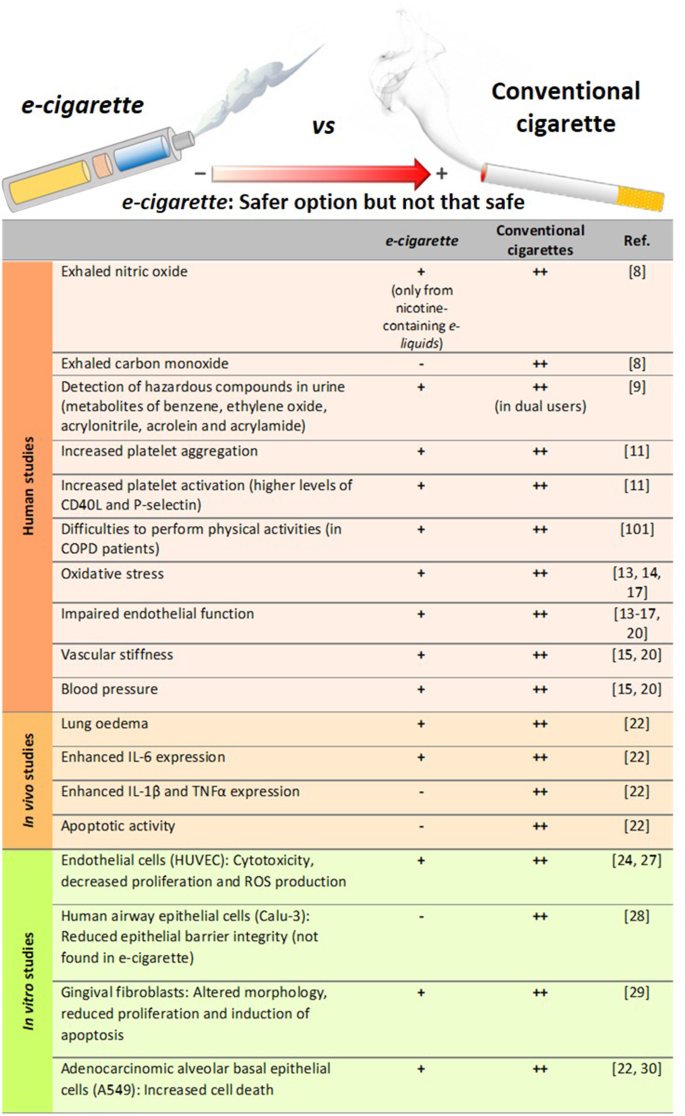

Long-term use of electronic cigarettes, or vaping products, can significantly impair the function of the body’s blood vessels, increasing the risk for cardiovascular disease. Additionally, the use of both e-cigarettes and regular cigarettes may cause an even greater risk than the use of either of these products alone. These findings come from two new studies supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

The findings, which appear today in the journal Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology , add to growing evidence that long-term use of e-cigarettes can harm a person’s health. Researchers have known for years that tobacco smoking can cause damage to blood vessels. However, the effects of e-cigarettes on cardiovascular health have been poorly understood. The two new studies – one on humans, the other on rats – aimed to change that.

“In our human study, we found that chronic e-cigarettes users had impaired blood vessel function, which may put them at increased risk for heart disease,” said Matthew L. Springer, Ph.D., a professor of medicine in the Division of Cardiology at the University of California in San Francisco, and leader of both studies. “It indicates that chronic users of e-cigarettes may experience a risk of vascular disease similar to that of chronic smokers.”

In this first study, Springer and his colleagues collected blood samples from a group of 120 volunteers that included those with long-term e-cigarette use, long-term cigarette smoking, and those who didn't use. The researchers defined long-term e-cigarette use as more than five times/week for more than three months and defined long-term cigarette use as smoking more than five cigarettes per day.

They then exposed each of the blood samples to cultured human blood vessel (endothelial) cells in the laboratory and measured the release of nitric oxide, a chemical marker used to evaluate proper functioning of endothelial cells. They also tested cell permeability, the ability of molecules to pass through a layer of cells to the other side. Too much permeability makes vessels leaky, which impairs function and increases the risk for cardiovascular disease.

The researchers found that blood from participants who used e-cigarettes and those who smoked caused a significantly greater decrease in nitric oxide production by the blood vessel cells than the blood of nonusers. Notably, the researchers found that blood from those who used e-cigarettes also caused more permeability in the blood vessel cells than the blood from both those who smoked cigarettes and nonusers. Blood from those that used e-cigarettes also caused a greater release of hydrogen peroxide by the blood vessel cells than the blood of the nonusers. Each of these three factors can contribute to impairment of blood vessel function in people who use e-cigarettes, the researchers said.

In addition, Springer and his team discovered that e-cigarettes had harmful cardiovascular effects in ways that were different from those caused by tobacco smoke. Specifically, they found that blood from people who smoked cigarettes had higher levels of certain circulating biomarkers of cardiovascular risks, and the blood people who used e-cigarettes had elevated levels of other circulating biomarkers of cardiovascular risks.

“These findings suggest that using the two products together, as many people do, could increase their health risks compared to using them individually,” Springer said. “We had not expected to see that.”