Paris, 1951. Photo by Elliot Erwitt/Magnum

Loved, yet lonely

You might have the unconditional love of family and friends and yet feel deep loneliness. can philosophy explain why.

by Kaitlyn Creasy + BIO

Although one of the loneliest moments of my life happened more than 15 years ago, I still remember its uniquely painful sting. I had just arrived back home from a study abroad semester in Italy. During my stay in Florence, my Italian had advanced to the point where I was dreaming in the language. I had also developed intellectual interests in Italian futurism, Dada, and Russian absurdism – interests not entirely deriving from a crush on the professor who taught a course on those topics – as well as the love sonnets of Dante and Petrarch (conceivably also related to that crush). I left my semester abroad feeling as many students likely do: transformed not only intellectually but emotionally. My picture of the world was complicated, my very experience of that world richer, more nuanced.

After that semester, I returned home to a small working-class town in New Jersey. Home proper was my boyfriend’s parents’ home, which was in the process of foreclosure but not yet taken by the bank. Both parents had left to live elsewhere, and they graciously allowed me to stay there with my boyfriend, his sister and her boyfriend during college breaks. While on break from school, I spent most of my time with these de facto roommates and a handful of my dearest childhood friends.

When I returned from Italy, there was so much I wanted to share with them. I wanted to talk to my boyfriend about how aesthetically interesting but intellectually dull I found Italian futurism; I wanted to communicate to my closest friends how deeply those Italian love sonnets moved me, how Bob Dylan so wonderfully captured their power. (‘And every one of them words rang true/and glowed like burning coal/Pouring off of every page/like it was written in my soul …’) In addition to a strongly felt need to share specific parts of my intellectual and emotional lives that had become so central to my self-understanding, I also experienced a dramatically increased need to engage intellectually, as well as an acute need for my emotional life in all its depth and richness – for my whole being, this new being – to be appreciated. When I returned home, I felt not only unable to engage with others in ways that met my newly developed needs, but also unrecognised for who I had become since I left. And I felt deeply, painfully lonely.

This experience is not uncommon for study-abroad students. Even when one has a caring and supportive network of relationships, one will often experience ‘reverse culture shock’ – what the psychologist Kevin Gaw describes as a ‘process of readjusting, reacculturating, and reassimilating into one’s own home culture after living in a different culture for a significant period of time’ – and feelings of loneliness are characteristic for individuals in the throes of this process.

But there are many other familiar life experiences that provoke feelings of loneliness, even if the individuals undergoing those experiences have loving friends and family: the student who comes home to his family and friends after a transformative first year at college; the adolescent who returns home to her loving but repressed parents after a sexual awakening at summer camp; the first-generation woman of colour in graduate school who feels cared for but also perpetually ‘ in-between ’ worlds, misunderstood and not fully seen either by her department members or her family and friends back home; the travel nurse who returns home to her partner and friends after an especially meaningful (or perhaps especially psychologically taxing) work assignment; the man who goes through a difficult breakup with a long-term, live-in partner; the woman who is the first in her group of friends to become a parent; the list goes on.

Nor does it take a transformative life event to provoke feelings of loneliness. As time passes, it often happens that friends and family who used to understand us quite well eventually fail to understand us as they once did, failing to really see us as they used to before. This, too, will tend to lead to feelings of loneliness – though the loneliness may creep in more gradually, more surreptitiously. Loneliness, it seems, is an existential hazard, something to which human beings are always vulnerable – and not just when they are alone.

In his recent book Life Is Hard (2022), the philosopher Kieran Setiya characterises loneliness as the ‘pain of social disconnection’. There, he argues for the importance of attending to the nature of loneliness – both why it hurts and what ‘that pain tell[s] us about how to live’ – especially given the contemporary prevalence of loneliness. He rightly notes that loneliness is not just a matter of being isolated from others entirely, since one can be lonely even in a room full of people. Additionally, he notes that, since the negative psychological and physiological effects of loneliness ‘seem to depend on the subjective experience of being lonely’, effectively combatting loneliness requires us to identify the origin of this subjective experience.

S etiya’s proposal is that we are ‘social animals with social needs’ that crucially include needs to be loved and to have our basic worth recognised. When we fail to have these basic needs met, as we do when we are apart from our friends, we suffer loneliness. Without the presence of friends to assure us that we matter, we experience the painful ‘sensation of hollowness, of a hole in oneself that used to be filled and now is not’. This is loneliness in its most elemental form. (Setiya uses the term ‘friends’ broadly, to include close family and romantic partners, and I follow his usage here.)

Imagine a woman who lands a job requiring a long-distance move to an area where she knows no one. Even if there are plenty of new neighbours and colleagues to greet her upon her arrival, Setiya’s claim is that she will tend to experience feelings of loneliness, since she does not yet have close, loving relationships with these people. In other words, she will tend to experience feelings of loneliness because she does not yet have friends whose love of her reflects back to her the basic value as a person that she has, friends who let her see that she matters. Only when she makes genuine friendships will she feel her unconditional value is acknowledged; only then will her basic social needs to be loved and recognised be met. Once she feels she truly matters to someone, in Setiya’s view, her loneliness will abate.

Setiya is not alone in connecting feelings of loneliness to a lack of basic recognition. In The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), for example, Hannah Arendt also defines loneliness as a feeling that results when one’s human dignity or unconditional worth as a person fails to be recognised and affirmed, a feeling that results when this, one of the ‘basic requirements of the human condition’, fails to be met.

These accounts get a good deal about loneliness right. But they miss something as well. On these views, loving friendships allow us to avoid loneliness because the loving friend provides a form of recognition we require as social beings. Without loving friendships, or when we are apart from our friends, we are unable to secure this recognition. So we become lonely. But notice that the feature affirmed by the friend here – my unconditional value – is radically depersonalised. The property the friend recognises and affirms in me is the same property she recognises and affirms in her other friendships. Otherwise put, the recognition that allegedly mitigates loneliness in Setiya’s view is the friend’s recognition of an impersonal, abstract feature of oneself, a quality one shares with every other human being: her unconditional worth as a human being. (The recognition given by the loving friend is that I ‘[matter] … just like everyone else.’)

Just as one can feel lonely in a room full of strangers, one can feel lonely in a room full of friends

Since my dignity or worth is disconnected from any particular feature of myself as an individual, however, my friend can recognise and affirm that worth without acknowledging or engaging my particular needs, specific values and so on. If Setiya is calling it right, then that friend can assuage my loneliness without engaging my individuality.

Or can they? Accounts that tie loneliness to a failure of basic recognition (and the alleviation of loneliness to love and acknowledgement of one’s dignity) may be right about the origin of certain forms of loneliness. But it seems to me that this is far from the whole picture, and that accounts like these fail to explain a wide variety of familiar circumstances in which loneliness arises.

When I came home from my study-abroad semester, I returned to a network of robust, loving friendships. I was surrounded daily by a steadfast group of people who persistently acknowledged and affirmed my unconditional value as a person, putting up with my obnoxious pretension (so it must have seemed) and accepting me even though I was alien in crucial ways to the friend they knew before. Yet I still suffered loneliness. In fact, while I had more close friendships than ever before – and was as close with friends and family members as I had ever been – I was lonelier than ever. And this is also true of the familiar scenarios from above: the first-year college student, the new parent, the travel nurse, and so on. All these scenarios are ripe for painful feelings of loneliness even though the individuals undergoing such experiences have a loving network of friends, family and colleagues who support them and recognise their unconditional value.

So, there must be more to loneliness than Setiya’s account (and others like it) let on. Of course, if an individual’s worth goes unrecognised, she will feel awfully lonely. But just as one can feel lonely in a room full of strangers, one can feel lonely in a room full of friends. What plagues accounts that tie loneliness to an absence of basic recognition is that they fail to do justice to loneliness as a feeling that pops up not only when one lacks sufficiently loving, affirmative relationships, but also when one perceives that the relationships she has (including and perhaps especially loving relationships) lack sufficient quality (for example, lacking depth or a desired feeling of connection). And an individual will perceive such relationships as lacking sufficient quality when her friends and family are not meeting the specific needs she has, or recognising and affirming her as the particular individual that she is.

We see this especially in the midst or aftermath of transitional and transformational life events, when greater-than-usual shifts occur. As the result of going through such experiences, we often develop new values, core needs and centrally motivating desires, losing other values, needs and desires in the process. In other words, after undergoing a particularly transformative experience, we become different people in key respects than we were before. If after such a personal transformation, our friends are unable to meet our newly developed core needs or recognise and affirm our new values and central desires – perhaps in large part because they cannot , because they do not (yet) recognise or understand who we have become – we will suffer loneliness.

This is what happened to me after Italy. By the time I got back, I had developed new core needs – as one example, the need for a certain level and kind of intellectual engagement – which were unmet when I returned home. What’s more, I did not think it particularly fair to expect my friends to meet these needs. After all, they did not possess the conceptual frameworks for discussing Russian absurdism or 13th-century Italian love sonnets; these just weren’t things they had spent time thinking about. And I didn’t blame them; expecting them to develop or care about developing such a conceptual framework seemed to me ridiculous. Even so, without a shared framework, I felt unable to meet my need for intellectual engagement and communicate to my friends the fullness of my inner life, which was overtaken by quite specific aesthetic values, values that shaped how I saw the world. As a result, I felt lonely.

I n addition to developing new needs, I understood myself as having changed in other fundamental respects. While I knew my friends loved me and affirmed my unconditional value, I did not feel upon my return home that they were able to see and affirm my individuality. I was radically changed; in fact, I felt in certain respects totally unrecognisable even to those who knew me best. After Italy, I inhabited a different, more nuanced perspective on the world; beauty, creativity and intellectual growth had become core values of mine; I had become a serious lover of poetry; I understood myself as a burgeoning philosopher. At the time, my closest friends were not able to see and affirm these parts of me, parts of me with which even relative strangers in my college courses were acquainted (though, of course, those acquaintances neither knew me nor were equipped to meet other of my needs which my friends had long met). When I returned home, I no longer felt truly seen by my friends .

One need not spend a semester abroad to experience this. For example, a nurse who initially chose her profession as a means to professional and financial stability might, after an especially meaningful experience with a patient, find herself newly and centrally motivated by a desire to make a difference in her patients’ lives. Along with the landscape of her desires, her core values may have changed: perhaps she develops a new core value of alleviating suffering whenever possible. And she may find certain features of her job – those that do not involve the alleviation of suffering, or involve the limited alleviation of suffering – not as fulfilling as they once were. In other words, she may have developed a new need for a certain form of meaningful difference-making – a need that, if not met, leaves her feeling flat and deeply dissatisfied.

Changes like these – changes to what truly moves you, to what makes you feel deeply fulfilled – are profound ones. To be changed in these respects is to be utterly changed. Even if you have loving friendships, if your friends are unable to recognise and affirm these new features of you, you may fail to feel seen, fail to feel valued as who you really are. At that point, loneliness will ensue. Interestingly – and especially troublesome for Setiya’s account – feelings of loneliness will tend to be especially salient and painful when the people unable to meet these needs are those who already love us and affirm our unconditional value.

Those with a strong need for their uniqueness to be recognised may be more disposed to loneliness

So, even with loving friends, if we perceive ourselves as unable to be seen and affirmed as the particular people we are, or if certain of our core needs go unmet, we will feel lonely. Setiya is surely right that loneliness will result in the absence of love and recognition. But it can also result from the inability – and sometimes, failure – of those with whom we have loving relationships to share or affirm our values, to endorse desires that we understand as central to our lives, and to satisfy our needs.

Another way to put it is that our social needs go far beyond the impersonal recognition of our unconditional worth as human beings. These needs can be as widespread as a need for reciprocal emotional attachment or as restricted as a need for a certain level of intellectual engagement or creative exchange. But even when the need in question is a restricted or uncommon one, if it is a deep need that requires another person to meet yet goes unmet, we will feel lonely. The fact that we suffer loneliness even when these quite specific needs are unmet shows that understanding and treating this feeling requires attending not just to whether my worth is affirmed, but to whether I am recognised and affirmed in my particularity and whether my particular, even idiosyncratic social needs are met by those around me.

What’s more, since different people have different needs, the conditions that produce loneliness will vary. Those with a strong need for their uniqueness to be recognised may be more disposed to loneliness. Others with weaker needs for recognition or reciprocal emotional attachment may experience a good deal of social isolation without feeling lonely at all. Some people might alleviate loneliness by cultivating a wide circle of not-especially-close friends, each of whom meets a different need or appreciates a different side of them. Yet others might persist in their loneliness without deep and intimate friendships in which they feel more fully seen and appreciated in their complexity, in the fullness of their being.

Yet, as ever-changing beings with friends and loved ones who are also ever-changing, we are always susceptible to loneliness and the pain of situations in which our needs are unmet. Most of us can recall a friend who once met certain of our core social needs, but who eventually – gradually, perhaps even imperceptibly – ultimately failed to do so. If such needs are not met by others in one’s life, this situation will lead one to feel profoundly, heartbreakingly lonely.

In cases like these, new relationships can offer true succour and light. For example, a lonely new parent might have childless friends who are clueless to the needs and values she develops through the hugely complicated transition to parenthood; as a result, she might cultivate relationships with other new parents or caretakers, people who share her newly developed values and better understand the joys, pains and ambivalences of having a child. To the extent that these new relationships enable her needs to be met and allow her to feel genuinely seen, they will help to alleviate her loneliness. Through seeking relationships with others who might share one’s interests or be better situated to meet one’s specific needs, then, one can attempt to face one’s loneliness head on.

But you don’t need to shed old relationships to cultivate the new. When old friends to whom we remain committed fail to meet our new needs, it’s helpful to ask how to salvage the situation, saving the relationship. In some instances, we might choose to adopt a passive strategy, acknowledging the ebb and flow of relationships and the natural lag time between the development of needs and others’ abilities to meet them. You could ‘wait it out’. But given that it is much more difficult to have your needs met if you don’t articulate them, an active strategy seems more promising. To position your friend to better meet your needs, you might attempt to communicate those needs and articulate ways in which you don’t feel seen.

Of course, such a strategy will be successful only if the unmet needs provoking one’s loneliness are needs one can identify and articulate. But we will so often – perhaps always – have needs, desires and values of which we are unaware or that we cannot articulate, even to ourselves. We are, to some extent, always opaque to ourselves. Given this opacity, some degree of loneliness may be an inevitable part of the human condition. What’s more, if we can’t even grasp or articulate the needs provoking our loneliness, then adopting a more passive strategy may be the only option one has. In cases like this, the only way to recognise your unmet needs or desires is to notice that your loneliness has started to lift once those needs and desires begin to be met by another.

Stories and literature

On Jewish revenge

What might a people, subjected to unspeakable historical suffering, think about the ethics of vengeance once in power?

Shachar Pinsker

Building embryos

For 3,000 years, humans have struggled to understand the embryo. Now there is a revolution underway

John Wallingford

Design and fashion

Sitting on the art

Given its intimacy with the body and deep play on form and function, furniture is a ripely ambiguous artform of its own

Emma Crichton Miller

Learning to be happier

In order to help improve my students’ mental health, I offered a course on the science of happiness. It worked – but why?

Consciousness and altered states

How perforated squares of trippy blotter paper allowed outlaw chemists and wizard-alchemists to dose the world with LSD

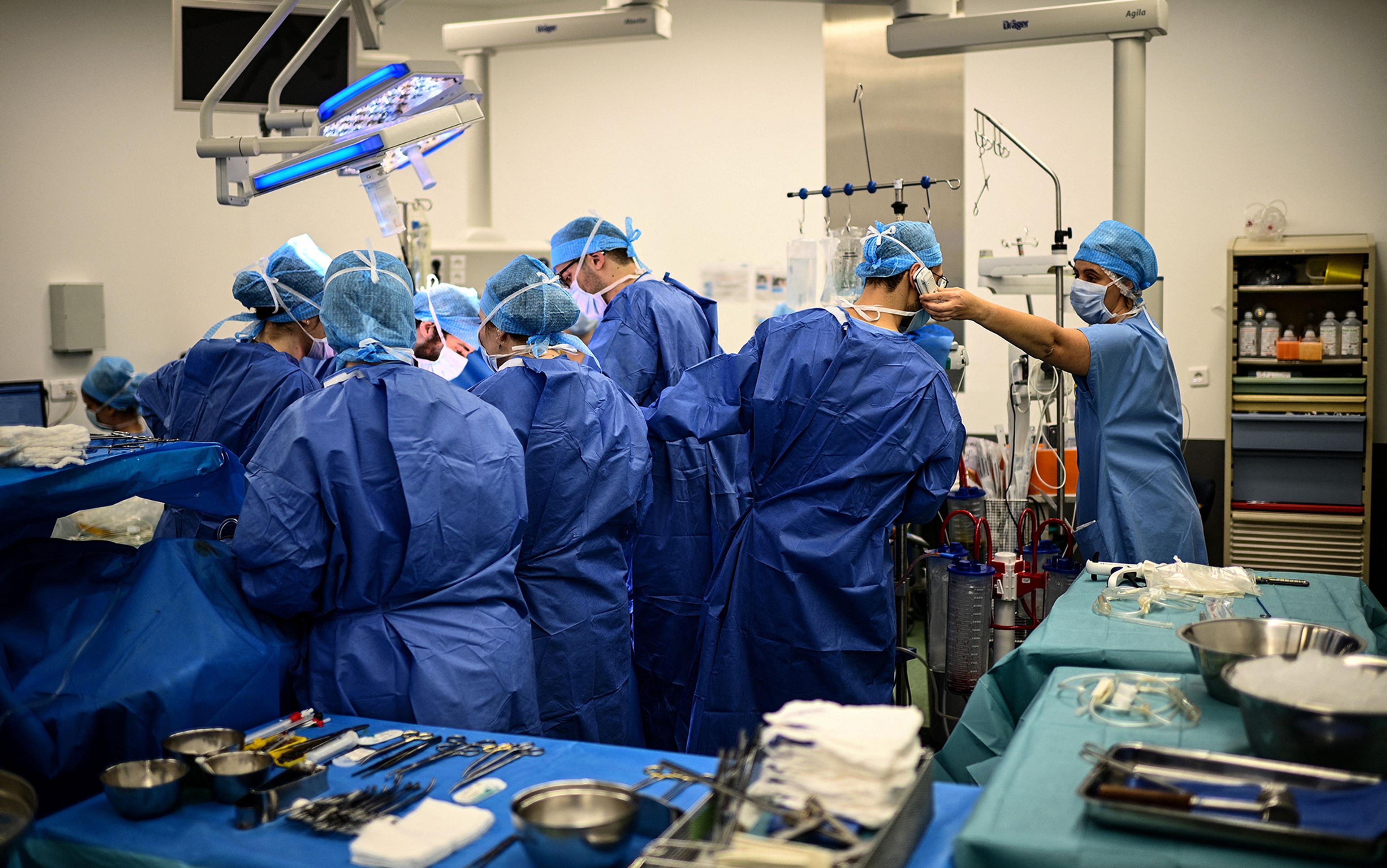

Last hours of an organ donor

In the liminal time when the brain is dead but organs are kept alive, there is an urgent tenderness to medical care

Ronald W Dworkin

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Life Obstacles

Life Experience Of Loneliness

*minimum deadline

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below

- Influential Person

- Writing Experience

- Foster Care

Related Essays

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Loneliness: Causes and Health Consequences

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Margaret Seide, MS, MD, is a board-certified psychiatrist who specializes in the treatment of depression, addiction, and eating disorders.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/MegSiede_1000-05e95c743d0b460eaa6610c4839c245c.jpg)

Loneliness vs. Solitude

- Health Risks

While common definitions of loneliness describe it as a state of solitude or being alone, loneliness is actually a state of mind. Loneliness causes people to feel empty, alone, and unwanted. People who are lonely often crave human contact, but their state of mind makes it more difficult to form connections with others.

Growing concerns around the dangers of loneliness have prompted a call to action by US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, who recently issued an 82-page advisory on the issue. The advisory cites data from several studies, including research that found that nearly half of adults in the US experience feelings of loneliness daily.

Murthy's report also cites a meta-analysis that found that the risk of premature death due to loneliness increased by 26% and 29% due to social isolation. Furthermore, the lack of social connection can increase the risk of anxiety, depression, stroke, heart disease, and dementia.

Johner Images / Getty Images

Defining Loneliness

Loneliness is a universal human emotion that is both complex and unique to each individual. Because it has no single common cause, preventing and treating this potentially damaging state of mind can vary dramatically.

For example, a lonely child who struggles to make friends at school has different needs than a lonely older adult whose spouse has recently died.

Researchers suggest that loneliness is associated with social isolation, poor social skills, introversion, and depression.

Loneliness, according to many experts, is not necessarily about being alone. Instead, if you feel alone and isolated, then that is how loneliness plays into your state of mind.

For example, a college freshman might feel lonely despite being surrounded by roommates and other peers. A soldier beginning their military career might feel lonely after being deployed to a foreign country, despite being constantly surrounded by other troop members.

Get Help Now

We've tried, tested, and written unbiased reviews of the best online therapy programs including Talkspace, Betterhelp, and Regain. Find out which option is the best for you.

Are You Feeling Lonely? Take the Test

This fast and free loneliness test can help you analyze your current emotions and determine whether or not you may be feeling lonely at the moment:

While research clearly shows that loneliness and isolation are bad for both mental and physical health, being alone is not the same as being lonely. In fact, solitude actually has a number of important mental health benefits, including allowing people to better focus and recharge.

- Loneliness is marked by feelings of isolation despite wanting social connections. It is often perceived as an involuntary separation, rejection, or abandonment by other people.

- Solitude , on the other hand, is voluntary. People who enjoy spending time by themselves continue to maintain positive social relationships that they can return to when they crave connection. They still spend time with others, but these interactions are balanced with periods of time alone.

Loneliness is a state of mind linked to wanting human contact but feeling alone. People can be alone and not feel lonely, or they can have contact with people and still experience feelings of isolation.

Causes of Loneliness

Contributing factors to loneliness include situational variables, such as physical isolation, moving to a new location, and divorce. The death of someone significant in a person's life can also lead to feelings of loneliness.

Additionally, it can be a symptom of a psychological disorder such as depression. Depression often causes people to withdrawal socially, which can lead to isolation. Research also suggests that loneliness can be a factor that contributes to symptoms of depression.

Loneliness can also be attributed to internal factors such as low self-esteem . People who lack confidence in themselves often believe that they are unworthy of the attention or regard of other people, which can lead to isolation and chronic loneliness .

Personality factors may also play a role. Introverts , for example, might be less likely to cultivate and seek social connections, which can contribute to feelings of isolation and loneliness.

Health Risks Associated With Loneliness

Loneliness has a wide range of negative effects on both physical and mental health , including:

- Alcohol and drug misuse

- Altered brain function

- Alzheimer's disease progression

- Antisocial behavior

- Cardiovascular disease and stroke

- Decreased memory and learning

- Depression and suicide

- Increased stress levels

- Poor decision-making

If you are having suicidal thoughts, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 for support and assistance from a trained counselor. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger, call 911.

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

These are not the only areas in which loneliness takes its toll. For example, lonely adults get less exercise than those who are not lonely. Their diet is higher in fat, their sleep is less efficient, and they report more daytime fatigue. Loneliness also disrupts the regulation of cellular processes deep within the body, predisposing lonely people to premature aging.

What Research Suggests About Loneliness

People who feel less lonely are more likely to be married, have higher incomes, and have higher educational status. High levels of loneliness are associated with physical health symptoms, living alone, small social networks, and low-quality social relationships.

Close Friends Help Combat Loneliness

Statistics suggest that loneliness is becoming increasingly prevalent, particularly in younger generations. According to one 2019 survey, 25% of adults between the ages of 18 and 27 reported having no close friends, while 22% reported having no friends at all.

The rise of the internet and ironically, social media, are partially to blame.

Experts believe that it is not the quantity of social interaction that combats loneliness, but the quality .

Having a few close friends is enough to ward off loneliness and reduce the negative health consequences associated with this state of mind. Research suggests that the experience of actual face-to-face contact with friends helps boost people's sense of well-being.

Loneliness Can Be Contagious

One study suggests that loneliness may actually be contagious. Research has found that non-lonely people who spend time with lonely people are more likely to develop feelings of loneliness.

Tips to Prevent and Overcome Loneliness

Loneliness can be overcome. It does require a conscious effort to make a change. In the long run, making a change can make you happier, healthier, and enable you to impact others around you in a positive way.

Here are some ways to prevent loneliness:

- Consider community service or another activity that you enjoy . These situations present great opportunities to meet people and cultivate new friendships and social interactions.

- Expect the best . Lonely people often expect rejection, so instead, try focusing on positive thoughts and attitudes in your social relationships.

- Focus on developing quality relationships . Seek people who share similar attitudes, interests, and values with you.

- Recognize that loneliness is a sign that something needs to change. Don't expect things to change overnight, but you can start taking steps that will help relieve your feelings of loneliness and build connections that support your well-being.

- Understand the effects of loneliness on your life . There are physical and mental repercussions to loneliness. If you recognize some of these symptoms affecting how you feel, make a conscious effort to combat them.

- Join a group or start your own . For example, you might try creating a Meetup group where people from your area with similar interests can get together. You might also consider taking a class at a community college, joining a book club, or taking an exercise class.

- Strengthen a current relationship . Building new connections is important, but improving your existing relationships can also be a great way to combat loneliness. Try calling a friend or family member you have spoken to in a while.

- Talk to someone you can trust . Reaching out to someone in your life to talk about what you are feeling is important. This can be someone you know such as a family member, but you might also consider talking to your doctor or a therapist. Online therapy can be a great option because it allows you to contact a therapist whenever it is convenient for you.

Loneliness can leave people feeling isolated and disconnected from others. It is a complex state of mind that can be caused by life changes, mental health conditions, poor self-esteem, and personality traits. Loneliness can also have serious health consequences including decreased mental wellness and physical problems.

Loneliness can have a serious effect on your health, so it is important to be able to recognize signs that you are feeling lonely. It is also important to remember that being alone isn't the same as being lonely.

If loneliness is affecting your well-being, there are things that you can do that can help you form new connections and find the social support that you need. Work on forming new connections and spend some time talking to people in your life. If you're still struggling, consider therapy. Whatever you choose to do, just remember that there are people who can help.

Bruce LD, Wu JS, Lustig SL, Russell DW, Nemecek DA. Loneliness in the United States: A 2018 National Panel Survey of Demographic, Structural, Cognitive, and Behavioral Characteristics. Am J Health Promot. 2019;33(8):1123-1133

Cigna Corporation. The Loneliness Epidemic Persists: A PostPandemic Look at the State of Loneliness among U.S. Adults. 2021

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science , 2015 10 (2), 227–237.

Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S. The growing problem of loneliness . Lancet . 2018;391(10119):426. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30142-9

Sbarra DA. Divorce and health: Current trends and future directions . Psychosom Med . 2015;77(3):227–236. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000168

Erzen E, Çikrikci Ö. The effect of loneliness on depression: A meta-analysis . Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018g;64(5):427-435. doi:10.1177/0020764018776349

Hämmig O. Health risks associated with social isolation in general and in young, middle and old age [published correction appears in PLoS One. 2019 Aug 29;14(8):e0222124]. PLoS One . 2019;14(7):e0219663. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0219663

Xia N, Li H. Loneliness, social isolation, and cardiovascular health . Antioxid Redox Signal . 2018 Mar 20;28(9):837-851. doi:10.1089/ars.2017.7312

Schrempft S, Jackowska M, Hamer M, Steptoe A. Associations between social isolation, loneliness, and objective physical activity in older men and women . BMC Public Health . 2019;19(1):74. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-6424-y

Shovestul B, Han J, Germine L, Dodell-Feder D. Risk factors for loneliness: The high relative importance of age versus other factors . PLoS One . 2020;15(2):e0229087. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0229087

Ballard J. Millennials are the loneliest generation . YouGov.

van der Horst M, Coffé H. How friendship network characteristics influence subjective well-being . Soc Indic Res . 2012;107(3):509-529. doi:10.1007/s11205-011-9861-2

Miller G. Social neuroscience. Why loneliness is hazardous to your health . Science . 2011;331(6014):138-40. doi:10.1126/science.331.6014.138

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The History of Loneliness

By Jill Lepore

The female chimpanzee at the Philadelphia Zoological Garden died of complications from a cold early in the morning of December 27, 1878. “Miss Chimpanzee,” according to news reports, died “while receiving the attentions of her companion.” Both she and that companion, a four-year-old male, had been born near the Gabon River, in West Africa; they had arrived in Philadelphia in April, together. “These Apes can be captured only when young,” the zoo superintendent, Arthur E. Brown, explained, and they are generally taken only one or two at a time. In the wild, “they live together in small bands of half a dozen and build platforms among the branches, out of boughs and leaves, on which they sleep.” But in Philadelphia, in the monkey house, where it was just the two of them, they had become “accustomed to sleep at night in each other’s arms on a blanket on the floor,” clutching each other, desperately, achingly, through the long, cold night.

The Philadelphia Zoological Garden was the first zoo in the United States. It opened in 1874, two years after Charles Darwin published “The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals,” in which he related what he had learned about the social attachments of primates from Abraham Bartlett, the superintendent of the Zoological Society of London:

Many kinds of monkeys, as I am assured by the keepers in the Zoological Gardens, delight in fondling and being fondled by each other, and by persons to whom they are attached. Mr. Bartlett has described to me the behavior of two chimpanzees, rather older animals than those generally imported into this country, when they were first brought together. They sat opposite, touching each other with their much protruded lips; and the one put his hand on the shoulder of the other. They then mutually folded each other in their arms. Afterwards they stood up, each with one arm on the shoulder of the other, lifted up their heads, opened their mouths, and yelled with delight.

Mr. and Miss Chimpanzee, in Philadelphia, were two of only four chimpanzees in America, and when she died human observers mourned her loss, but, above all, they remarked on the behavior of her companion. For a long time, they reported, he tried in vain to rouse her. Then he “went into a frenzy of grief.” This paroxysm accorded entirely with what Darwin had described in humans: “Persons suffering from excessive grief often seek relief by violent and almost frantic movements.” The bereaved chimpanzee began to pull out the hair from his head. He wailed, making a sound the zookeeper had never heard before: Hah-ah-ah-ah-ah . “His cries were heard over the entire garden. He dashed himself against the bars of the cage and butted his head upon the hard-wood bottom, and when this burst of grief was ended he poked his head under the straw in one corner and moaned as if his heart would break.”

Nothing quite like this had ever been recorded. Superintendent Brown prepared a scholarly article, “Grief in the Chimpanzee.” Even long after the death of the female, Brown reported, the male “invariably slept on a cross-beam at the top of the cage, returning to inherited habit, and showing, probably, that the apprehension of unseen dangers has been heightened by his sense of loneliness.”

Loneliness is grief, distended. People are primates, and even more sociable than chimpanzees. We hunger for intimacy. We wither without it. And yet, long before the present pandemic, with its forced isolation and social distancing, humans had begun building their own monkey houses. Before modern times, very few human beings lived alone. Slowly, beginning not much more than a century ago, that changed. In the United States, more than one in four people now lives alone; in some parts of the country, especially big cities, that percentage is much higher. You can live alone without being lonely, and you can be lonely without living alone, but the two are closely tied together, which makes lockdowns, sheltering in place, that much harder to bear. Loneliness, it seems unnecessary to say, is terrible for your health. In 2017 and 2018, the former U.S. Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy declared an “epidemic of loneliness,” and the U.K. appointed a Minister of Loneliness. To diagnose this condition, doctors at U.C.L.A. devised a Loneliness Scale. Do you often, sometimes, rarely, or never feel these ways?

I am unhappy doing so many things alone. I have nobody to talk to. I cannot tolerate being so alone. I feel as if nobody really understands me. I am no longer close to anyone. There is no one I can turn to. I feel isolated from others.

In the age of quarantine, does one disease produce another?

“Loneliness” is a vogue term, and like all vogue terms it’s a cover for all sorts of things most people would rather not name and have no idea how to fix. Plenty of people like to be alone. I myself love to be alone. But solitude and seclusion, which are the things I love, are different from loneliness, which is a thing I hate. Loneliness is a state of profound distress. Neuroscientists identify loneliness as a state of hypervigilance whose origins lie among our primate ancestors and in our own hunter-gatherer past. Much of the research in this field was led by John Cacioppo, at the Center for Cognitive and Social Neuroscience, at the University of Chicago. Cacioppo, who died in 2018, was known as Dr. Loneliness. In the new book “ Together: The Healing Power of Human Connection in a Sometimes Lonely World ” (Harper Wave), Murthy explains how Cacioppo’s evolutionary theory of loneliness has been tested by anthropologists at the University of Oxford, who have traced its origins back fifty-two million years, to the very first primates. Primates need to belong to an intimate social group, a family or a band, in order to survive; this is especially true for humans (humans you don’t know might very well kill you, which is a problem not shared by most other primates). Separated from the group—either finding yourself alone or finding yourself among a group of people who do not know and understand you—triggers a fight-or-flight response. Cacioppo argued that your body understands being alone, or being with strangers, as an emergency. “Over millennia, this hypervigilance in response to isolation became embedded in our nervous system to produce the anxiety we associate with loneliness,” Murthy writes. We breathe fast, our heart races, our blood pressure rises, we don’t sleep. We act fearful, defensive, and self-involved, all of which drive away people who might actually want to help, and tend to stop lonely people from doing what would benefit them most: reaching out to others.

The loneliness epidemic, in this sense, is rather like the obesity epidemic. Evolutionarily speaking, panicking while being alone, like finding high-calorie foods irresistible, is highly adaptive, but, more recently, in a world where laws (mostly) prevent us from killing one another, we need to work with strangers every day, and the problem is more likely to be too much high-calorie food rather than too little. These drives backfire.

Loneliness, Murthy argues, lies behind a host of problems—anxiety, violence, trauma, crime, suicide, depression, political apathy, and even political polarization. Murthy writes with compassion, but his everything-can-be-reduced-to-loneliness argument is hard to swallow, not least because much of what he has to say about loneliness was said about homelessness in the nineteen-eighties, when “homelessness” was the vogue term—a word somehow easier to say than “poverty”—and saying it didn’t help. (Since then, the number of homeless Americans has increased.) Curiously, Murthy often conflates the two, explaining loneliness as feeling homeless. To belong is to feel at home. “To be at home is to be known,” he writes. Home can be anywhere. Human societies are so intricate that people have meaningful, intimate ties of all kinds, with all sorts of groups of other people, even across distances. You can feel at home with friends, or at work, or in a college dining hall, or at church, or in Yankee Stadium, or at your neighborhood bar. Loneliness is the feeling that no place is home. “In community after community,” Murthy writes, “I met lonely people who felt homeless even though they had a roof over their heads.” Maybe what people experiencing loneliness and people experiencing homelessness both need are homes with other humans who love them and need them, and to know they are needed by them in societies that care about them. That’s not a policy agenda. That’s an indictment of modern life.

In “ A Biography of Loneliness: The History of an Emotion ” (Oxford), the British historian Fay Bound Alberti defines loneliness as “a conscious, cognitive feeling of estrangement or social separation from meaningful others,” and she objects to the idea that it’s universal, transhistorical, and the source of all that ails us. She argues that the condition really didn’t exist before the nineteenth century, at least not in a chronic form. It’s not that people—widows and widowers, in particular, and the very poor, the sick, and the outcast—weren’t lonely; it’s that, since it wasn’t possible to survive without living among other people, and without being bonded to other people, by ties of affection and loyalty and obligation, loneliness was a passing experience. Monarchs probably were lonely, chronically. (Hey, it’s lonely at the top!) But, for most ordinary people, daily living involved such intricate webs of dependence and exchange—and shared shelter—that to be chronically or desperately lonely was to be dying. The word “loneliness” very seldom appears in English before about 1800. Robinson Crusoe was alone, but never lonely. One exception is “Hamlet”: Ophelia suffers from “loneliness”; then she drowns herself.

Modern loneliness, in Alberti’s view, is the child of capitalism and secularism. “Many of the divisions and hierarchies that have developed since the eighteenth century—between self and world, individual and community, public and private—have been naturalized through the politics and philosophy of individualism,” she writes. “Is it any coincidence that a language of loneliness emerged at the same time?” It is not a coincidence. The rise of privacy, itself a product of market capitalism—privacy being something that you buy—is a driver of loneliness. So is individualism, which you also have to pay for.

Alberti’s book is a cultural history (she offers an anodyne reading of “Wuthering Heights,” for instance, and another of the letters of Sylvia Plath ). But the social history is more interesting, and there the scholarship demonstrates that whatever epidemic of loneliness can be said to exist is very closely associated with living alone. Whether living alone makes people lonely or whether people live alone because they’re lonely might seem to be harder to say, but the preponderance of the evidence supports the former: it is the force of history, not the exertion of choice, that leads people to live alone. This is a problem for people trying to fight an epidemic of loneliness, because the force of history is relentless.

Before the twentieth century, according to the best longitudinal demographic studies, about five per cent of all households (or about one per cent of the world population) consisted of just one person. That figure began rising around 1910, driven by urbanization, the decline of live-in servants, a declining birth rate, and the replacement of the traditional, multigenerational family with the nuclear family. By the time David Riesman published “ The Lonely Crowd ,” in 1950, nine per cent of all households consisted of a single person. In 1959, psychiatry discovered loneliness, in a subtle essay by the German analyst Frieda Fromm-Reichmann. “Loneliness seems to be such a painful, frightening experience that people will do practically everything to avoid it,” she wrote. She, too, shrank in horror from its contemplation. “The longing for interpersonal intimacy stays with every human being from infancy through life,” she wrote, “and there is no human being who is not threatened by its loss.” People who are not lonely are so terrified of loneliness that they shun the lonely, afraid that the condition might be contagious. And people who are lonely are themselves so horrified by what they are experiencing that they become secretive and self-obsessed—“it produces the sad conviction that nobody else has experienced or ever will sense what they are experiencing or have experienced,” Fromm-Reichmann wrote. One tragedy of loneliness is that lonely people can’t see that lots of people feel the same way they do.

“During the past half century, our species has embarked on a remarkable social experiment,” the sociologist Eric Klinenberg wrote in “ Going Solo: The Extraordinary Rise and Surprising Appeal of Living Alone ,” from 2012. “For the first time in human history, great numbers of people—at all ages, in all places, of every political persuasion—have begun settling down as singletons.” Klinenberg considers this to be, in large part, a triumph; more plausibly, it is a disaster. Beginning in the nineteen-sixties, the percentage of single-person households grew at a much steeper rate, driven by a high divorce rate, a still-falling birth rate, and longer lifespans over all. (After the rise of the nuclear family, the old began to reside alone, with women typically outliving their husbands.) A medical literature on loneliness began to emerge in the nineteen-eighties, at the same time that policymakers became concerned with, and named, “homelessness,” which is a far more dire condition than being a single-person household: to be homeless is to be a household that does not hold a house. Cacioppo began his research in the nineteen-nineties, even as humans were building a network of computers, to connect us all. Klinenberg, who graduated from college in 1993, is particularly interested in people who chose to live alone right about then.

I suppose I was one of them. I tried living alone when I was twenty-five, because it seemed important to me, the way owning a piece of furniture that I did not find on the street seemed important to me, as a sign that I had come of age, could pay rent without subletting a sublet. I could afford to buy privacy, I might say now, but then I’m sure I would have said that I had become “my own person.” I lasted only two months. I didn’t like watching television alone, and also I didn’t have a television, and this, if not the golden age of television, was the golden age of “The Simpsons,” so I started watching television with the person who lived in the apartment next door. I moved in with him, and then I married him.

This experience might not fit so well into the story Klinenberg tells; he argues that networked technologies of communication, beginning with the telephone’s widespread adoption, in the nineteen-fifties, helped make living alone possible. Radio, television, Internet, social media: we can feel at home online. Or not. Robert Putnam’s influential book about the decline of American community ties, “Bowling Alone,” came out in 2000, four years before the launch of Facebook, which monetized loneliness. Some people say that the success of social media was a product of an epidemic of loneliness; some people say it was a contributor to it; some people say it’s the only remedy for it. Connect! Disconnect! The Economist declared loneliness to be “the leprosy of the 21st century.” The epidemic only grew.

This is not a peculiarly American phenomenon. Living alone, while common in the United States, is more common in many other parts of the world, including Scandinavia, Japan, Germany, France, the U.K., Australia, and Canada, and it’s on the rise in China, India, and Brazil. Living alone works best in nations with strong social supports. It works worst in places like the United States. It is best to have not only an Internet but a social safety net.

Then the great, global confinement began: enforced isolation, social distancing, shutdowns, lockdowns, a human but inhuman zoological garden. Zoom is better than nothing. But for how long? And what about the moment your connection crashes: the panic, the last tie severed? It is a terrible, frightful experiment, a test of the human capacity to bear loneliness. Do you pull out your hair? Do you dash yourself against the walls of your cage? Do you, locked inside, thrash and cry and moan? Sometimes, rarely, or never? More today than yesterday? ♦

A Guide to the Coronavirus

- How to practice social distancing , from responding to a sick housemate to the pros and cons of ordering food.

- How people cope and create new customs amid a pandemic.

- What it means to contain and mitigate the coronavirus outbreak.

- How much of the world is likely to be quarantined ?

- Donald Trump in the time of coronavirus .

- The coronavirus is likely to spread for more than a year before a vaccine could be widely available.

- We are all irrational panic shoppers .

- The strange terror of watching the coronavirus take Rome .

- How pandemics change history .

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Robin Wright

By Bill McKibben

By Maya Jasanoff

By Kelefa Sanneh

- Your Stories

Evidence Based Living

Bridging the gap between research and real life

- In The Media

- The Learning Center

- Cornell Cooperative Extension

- Youth Development

- Health and Wellness

The Evidence on Loneliness and What To Do About It

As governments tell huge numbers of Americans to stay home to stop the spread of coronavirus, it’s natural for some people to experience feelings of loneliness – especially those who live alone and may go for days without seeing another human in person.

This level of social isolation is certainly unprecedented in our modern society. But there is a significant body of evidence on isolation and loneliness that can help us understand the broader effects of social distancing, and some steps we can take to mitigate them.

First, there is ample evidence that shows sustained loneliness is not simply equated with sadness or depression, but leads to larger health implications. Among older adults, loneliness increases the risk of developing dementia , slows down their walking speeds , interferes with their ability to care for themselves and increases their risk of heart disease and stroke . Loneliness is even associated with dying earlier .

Even before the coronavirus pandemic, about a third of people living in industrialized nations experienced loneliness. Data show the condition is not influenced by income, education levels, gender or ethnicity.

So, what can we do about loneliness? There is a large body of evidence that describes a broad range of interventions to help. One systematic review demonstrates that physical activity can help to reduce levels of loneliness somewhat. (Although there is some question as to whether people who are lonely simply do not exercise.) The authors also question whether it’s physical activity with other people that actually reduces loneliness. In this climate of social distancing, this could mean that going on a walk outside with a friend – of course, while maintaining the prescribed six-foot distance apart – may be an effective way to reduce loneliness.

Another meta-analysis from the University of Chicago looked at a wide range of interventions to address loneliness. Surprisingly, interventions that involved interaction with others, receiving social support or improving social skills were not the most effective. Instead, what helped the most was therapy for a condition called maladaptive social cognition — essentially negative thoughts about self-worth and how other people perceive you. The article found this is especially true for feelings of loneliness that occur regularly over time.

Given our current crisis situation, clearly everyone who feels lonely is not suffering from maladaptive social cognition. But focusing on positive thoughts about yourself in a consistent manner may help you to feel a little less lonely.

A third meta-analysis conducted by researchers from Italy and Poland focused on loneliness interventions for older adults. It found that interventions involving technology were among the most effective ways to reduce loneliness, and that community-based art programs – such as classes and performances – were also effective at reducing loneliness.

During social distancing, connecting with friends and loved ones via technology is a viable option. Platforms such as Zoom, Facetime and Google Meet are all offering free video-conferencing services. A virtual happy hour can be a surprisingly fun way to spend an hour.

Community art programs may be trickier to pull off during the pandemic. But a Google search of online drawing classes or Broadway musicals reveals a wide variety options to pass the time. Many of these online services are currently offering these programs free of charge. If they don’t help alleviate loneliness, they may at least help pass the time.

The take-home message: Loneliness is a real problem that affects overall well-being and health. While many Americans are being asked to stay home, there are some evidence-based steps you can take to reduce feelings of loneliness.

Visit Cornell University’s Bronfenbrenner Center for Translational Research’s website for more information on our work solving human problems.

Speak Your Mind Cancel reply

A project at…, evidence-based blogs.

- Bandolier Evidence-Based Health Care

- British Psychological Society Research Digest

- Economics in Cooperative Extension

- EPB Exchange

- New Voices for Research

- Research Blogging

- Trust the Evidence

Subscribe by e-mail

Please, insert a valid email.

Thank you, your email will be added to the mailing list once you click on the link in the confirmation email.

Spam protection has stopped this request. Please contact site owner for help.

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Return to top of page

Copyright © 2024 · Magazine Theme on Genesis Framework · WordPress · Log in

Loneliness and Social Connections

Family and friends are important for our well-being. In this article, we explore data on loneliness and social connections and review available evidence on the link between social connections and well-being.

By Esteban Ortiz-Ospina

This article was first published in February 2020 and last updated in March 2024.

Research shows that social connections are important for our well-being. Having support from family and friends is important for our happiness and health and is also instrumental to our ability to share information, learn from others, and seize economic opportunities.

In this article, we explore data on loneliness and social connections across countries and over time and review the available evidence on how and why social connections and loneliness affect our health and emotional welfare, as well as our material well-being.

Despite the fact that there is a clear link between social connections and well-being, more research is needed to understand causal mechanisms, effect sizes, and changes over time.

As we show here, oversimplified narratives that compare loneliness with smoking or that claim we are living in a 'loneliness epidemic' are wrong and unhelpful.

See all interactive charts on loneliness and social connections ↓

Related topics

Happiness and Life Satisfaction

Self-reported life satisfaction differs widely between people and between countries. What explains these differences?

Trust is an essential part of social connections. Trust is crucial for community well-being and effective cooperation.

For many, the internet is now essential for work, finding information, and connecting with others.

Other research and writing on polio on Our World in Data:

- Are Facebook and other social media platforms bad for our well-being?

- Are people more likely to be lonely in so-called 'individualistic' societies?

- Is there a loneliness epidemic?

- The importance of social networks for innovation and productivity

- The importance of personal relations for economic outcomes

- Who do we spend time with across our lifetime?

Social connections

How important are social connections for our health.

Dr. Vivek Murthy, former Surgeon General of the United States, recently wrote : “Loneliness and weak social connections are associated with a reduction in lifespan similar to that caused by smoking 15 cigarettes a day”.

This ‘15 cigarettes a day’ figure has been reproduced and reported in the news many times, under headlines such as “Loneliness is as lethal as smoking 15 cigarettes per day”. 1

It is indeed quite a shocking comparison since millions of deaths globally are attributed to smoking every year, and back-of-the-envelope calculations published in medical journals say one cigarette reduces your lifespan by 11 minutes .

Here, we dig deeper to try to understand what the data and research tell us about the link between social relations and health. In a nutshell, the evidence is as follows:

- There is a huge amount of evidence showing individuals who report feelings of loneliness are more likely to have health problems later in their life.

- There is a credible theory and explanation of biological mechanisms whereby isolation can set off unconscious surveillance for social threats, producing cognitive biases, reducing sleep, and affecting hormones.

- It's very likely there is a causal link. Still, there is no credible experimental evidence that would allow us to have a precise estimate of the magnitude of the causal effect that loneliness has on key metrics of health, such as life expectancy.

- The fact that we struggle to pin down the magnitude of the effect of loneliness on health doesn't mean we should dismiss the available evidence. However, it does show that more research is needed.

Observational studies: A first look at the data

Measuring loneliness.

Psychologists and social neuroscientists often refer to loneliness as painful isolation . The emphasis on pain is there to make a clear distinction between solitude – the state of being alone – and subjective loneliness, which is the distressing feeling that comes from unmet expectations of the types of interpersonal relationships we wish to have.

Researchers use several kinds of data to measure solitude and loneliness. The most common source of data are surveys where people are asked about different aspects of their lives, including whether they live alone, how much time they spend with other people in a given window of time (e.g., ‘last week’), or specific context (e.g., ‘at social events, clubs or places of worship’); and whether they experience feelings of loneliness (e.g., ‘I have no-one with whom I can discuss important matters with’). Researchers sometimes study these survey responses separately, but often, they also aggregate them in a composite index. 2

Surveys confirm that people respond differently to questions about subjective loneliness and physical social isolation, which suggests people do understand these as two distinct issues.

In the chart here I've put together estimates on self-reported feelings of loneliness from various sources. The fact that we see such high levels of loneliness, with substantial divergence across countries, explains why this is an important and active research area. Indeed, there are literally hundreds of papers that have used survey data to explore the link between loneliness, solitude, and health. Below is an overview of what these studies find.

The link between loneliness and physical health

Most papers studying the link between loneliness and health find that both objective solitude (e.g., living alone) and subjective loneliness (e.g., frequent self-reported feelings of loneliness) are correlated with higher morbidity (i.e. illness) and higher mortality (i.e. likelihood of death).

The relationship between health and loneliness can, of course, go both ways: lonely people may see their health deteriorate with time, but it may also be the case that people who suffer from poor health end up feeling more lonely later down the line.

Because of this two-way relationship, it’s important to go beyond cross-sectional correlations and focus on longitudinal studies – these are studies where researchers track the same individuals over time to see if loneliness predicts illness or mortality in the future after controlling for baseline behaviors and health status.

The evidence from longitudinal studies shows that people who experience loneliness during a period of their lives tend to be more likely to have worse health later down the line. In the Netherlands, for example, researchers found that self-reported loneliness among adults aged 55-85 predicted mortality several months later, and this was true after controlling for age, sex, chronic diseases, alcohol use, smoking, self-assessed health condition, and functional limitations. 3

Most studies focus either on subjective loneliness or on objective isolation. However, some studies try to compare both. In a recent meta-analysis covering 70 longitudinal studies, the authors write : “We found no differences between measures of objective and subjective social isolation. Results remain consistent across gender, length of follow-up, and world region.” In the concluding section, they highlight that, in their interpretation of the evidence, “the risk associated with social isolation and loneliness is comparable with well-established risk factors for mortality” ; which include smoking and obesity. 4

The link between mental health and subjective well-being

In another much-cited review of the evidence, Louise Hawkley and John Cacioppo, two leading experts on this topic, concluded that “perhaps the most striking finding in this literature is the breadth of emotional and cognitive processes and outcomes that seem susceptible to the influence of loneliness”. 5

Researchers have found that loneliness correlates with subsequent increases in symptoms related to dementia , depression , and many other issues related to mental health , and this holds after controlling for demographic variables, objective social isolation, stress, and baseline levels of cognitive function.

There is also research that suggests a link between loneliness and lower happiness , and we discuss this in more detail here .

Experiments with social animals, like rats, show that induced isolation can lead to a higher risk of death from cancer. Humans and rats are, of course, very different, but experts such as Hawkley and Cacioppo argue that these experiments are important because they tell us something meaningful about a shared biological mechanism.

In a review of the evidence, Susan Pinker writes: “If our big brains evolved to interact, loneliness would be an early warning system—a built-in alarm that sent a biological signal to members who had somehow become separated from the group”. 6

Indeed, there’s evidence of social regulation of gene expression in humans: studies suggest perceived loneliness can switch on/off genes that regulate our immune systems, and it is this that then affects the health of humans, or other animals that evolved with similar defense mechanisms. 7

Causality and implications

The bulk of evidence from observational studies and biological mechanisms described above implies that loneliness most likely matters for our health and well being. But do we really know how much it matters relative to other important risk factors?

The key point here is that estimates are likely biased to some extent.

The findings from longitudinal studies that track individuals over time are insightful. Still, they cannot rule out that the relationship might be partly driven by other factors we cannot observe. Even the studies linking loneliness and genetics can be subject to omitted-variable bias because a genetic predisposition to loneliness may drive both loneliness and health outcomes. 8

I could not find credible experimental evidence that would allow us to have a precise estimate of the magnitude of the causal effect. 9 But the fact that we struggle to pin down the magnitude of the effect doesn't mean we should dismiss the available evidence. On the contrary – it would be great if we had evidence from randomized control trials that test positive interventions to reduce loneliness to understand better if the ‘15 cigarettes per day’ comparison from the Surgeon General of the US is roughly correct, at least for the average person.

Having a better understanding of the magnitude of the effect is important, not only because loneliness is common but also because it’s complex and unequally experienced by people around the world.

As the chart above shows, there are large differences in self-reported loneliness across countries. We should understand how important these differences are for the distribution of health and well-being.

Are we happier when we spend more time with others?

In 1938, a group of Harvard researchers decided to start a research program to track the lives of a group of young men in what eventually became one of the longest and most famous longitudinal studies of its kind. The idea was to track the development of a group of teenage boys through periodic interviews and medical checkups, with the aim of understanding how their health and well-being evolved as they grew up. 10

Today, more than 80 years later, it is one of the longest running research programs in social science. It is called the Harvard Study of Adult Development , and it is still running. The program started with 724 boys, and researchers continue to monitor today the health and well-being of those initial participants who are still alive, most in their late 90s. 11

This is a unique scientific exercise – most longitudinal studies do not last this long because too many participants drop out, researchers move on to other projects (or even die), or the funding dries up.

So, what have we learned from this unique study?

Robert Waldinger, the current director of the study, summarized – in what is now one of the most viewed TED Talks to date – the findings from decades of research. The main result, he concluded, is that social connections are one of the most important factors for people’s happiness and health . He said: “Those who kept warm relationships got to live longer and happier, and the loners often died earlier.”

Here, we will take a closer look at the evidence and show more research that finds a consistent link between social connections and happiness. But before we get to the details, let me explain why this link is important.

As most people can attest from personal experience, striving for happiness is not easy. In fact, the search for happiness can become a source of unhappiness – there are studies that show actively pursuing happiness can end up decreasing it .

The data shows that income and happiness are clearly related , but we also know from surveys that people often overestimate the impact of income on happiness . Social relations might be the missing link: In rich countries, where minimum material living conditions are often satisfied , people may struggle to become happier because they target material rather than social goals.

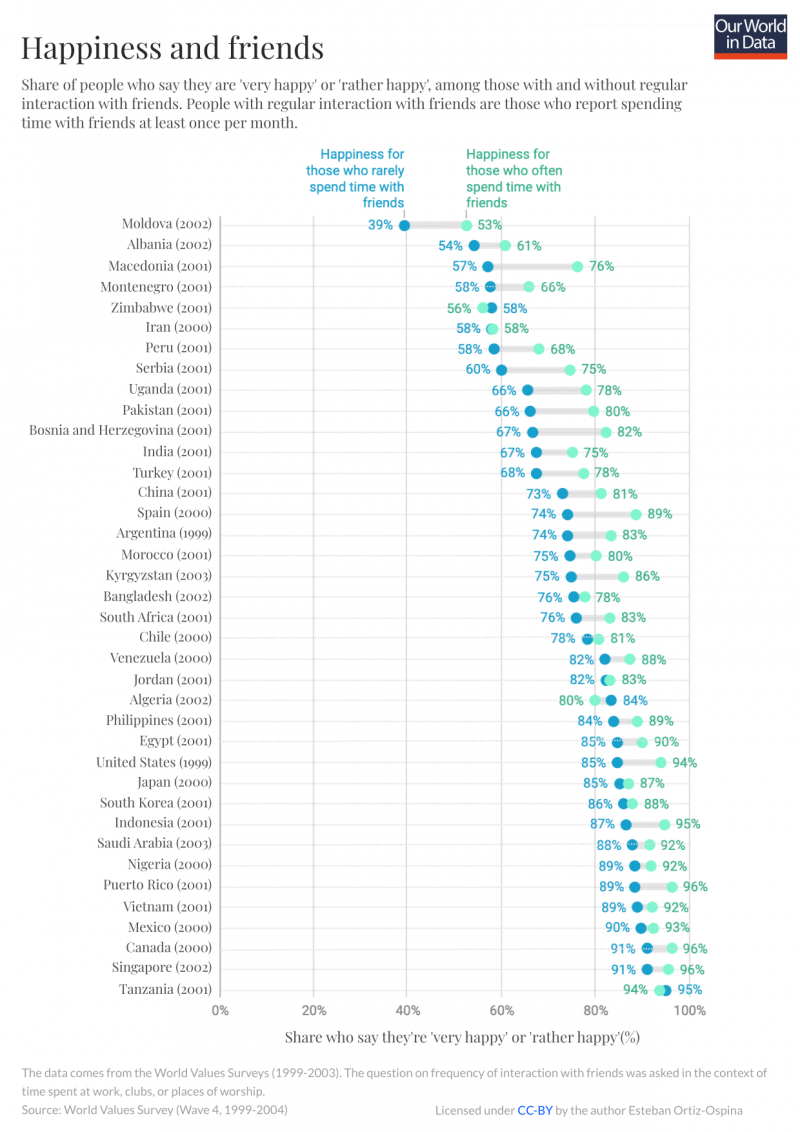

The cross-sectional correlation between happiness and friends

The World Values Survey (WVS) is a large cross-country research project that collects data from a series of representative national surveys. In the fourth wave (1999-2004), the WVS asked respondents hundreds of questions about their lives, including whether they were part of social or religious groups, how often they spent time with friends, and whether they felt happy with their lives.

By comparing self-reported happiness among those with and without frequent social interactions, we can get an idea of whether there is indeed a raw correlation between happiness and social relations across different societies.

The next chart shows the comparison: The green points correspond to happiness among those who interact with friends at least once per month, while the blue dots correspond to happiness among those who interact with friends less often. 12

This chart shows that in almost all countries, people who often spend time with their friends report being happier than those who spend less time with friends. 13

The link between social relations and happiness over time

The chart above gives a cross-sectional perspective – it’s just a snapshot that compares different people at a given point in time. What happens if we look at changes in social relations and happiness over time?

There is a large academic literature in medicine and psychology that shows individuals who report feelings of loneliness are more likely to have health problems later in life (you can read more about this in this article on social relations and health ); similarly, there are also many studies that show that changes in social relations predict changes in happiness and life satisfaction.

One of the research papers that draws on data from the famous Harvard Study of Adult Development, for example, looked at the experiences of 82 married participants and their spouses and found that greater self-reported couple attachment predicted lower levels of depression and greater life satisfaction 2.5 years later. 14

Other studies with larger population samples have also found a similar cross-temporal link: perceived social isolation predicts subsequent changes in depressive symptoms but not vice versa, and this holds after controlling for demographic variables and stress. 15

Searching for happiness is typically an intentional and active pursuit. Is it the case that people tend to become happier when they purposely decide to improve their social relations?

This is a tough empirical question to test; but a recent study found evidence pointing in this direction.

Using a large representative survey in Germany, researchers asked participants to report, in text format, ideas for how they could improve their life satisfaction. Based on these answers, the researchers then investigated which types of ideas predicted changes in life satisfaction one year later.

The researchers found that those who reported socially engaged strategies (e.g., “I plan to spend more time with friends and family”) often reported improvements in life satisfaction one year later. In contrast, those who described other non-social active pursuits (e.g., “I plan to find a better job”) did not report increased life satisfaction. 16

From decades of research, we know that social relations predict mental well-being over time; and from a recent study, we also know that people who actively decide to improve their social relations often report becoming happier. So yes, people are happier when they spend more time with friends.

Does this mean that if we have an exogenous shock to our social relations this will have a permanent negative effect on our happiness?

We can’t really answer this with the available evidence. More research is needed to really understand the causal mechanisms that drive the link between happiness and social relations. 17

Despite this, however, I think that we should take the available observational evidence seriously. In a way, the causal impact of a random shock is less interesting than the evidence from active strategies that people might take to improve their happiness. People who get divorced, for example, often report a short-term drop in life satisfaction. Still, over time, they tend to recover and eventually end up being more satisfied with their life than shortly before they divorced (you can read more about this in our entry on happiness and life satisfaction ).

It makes sense to consider the possibility that healthy social relationships are a key missing piece for human well-being. Among other things, this would help explain the paradoxical result from studies where actively pursuing happiness apparently decreases it .

Loneliness, solitude, and social isolation

Living alone is becoming increasingly common around the world.

In the US, the share of adults who live alone nearly doubled over the last 50 years . This is not only happening in the US: single-person households have become increasingly common in many countries across the world, from Angola to Japan .

Historical records show that this ‘rise of living alone’ started in early-industrialized countries over a century ago, accelerating around 1950. In countries such as Norway and Sweden, single-person households were rare a century ago, but today, they account for nearly half of all households. In some cities, they are already the majority.

Surveys and census data from recent decades show that people are more likely to live alone in rich countries, and the prevalence of single-person households is unprecedented historically.

Social connections – including contact with friends and family – are important for our health and emotional well-being. Hence, as single-person households become more common, there will be new challenges to connect and support those living alone, particularly in poorer countries where welfare states are weaker.

But it’s important to keep things in perspective. It’s unhelpful to compare the rise of living alone with a ‘loneliness epidemic’, which is what newspaper articles often write in alarming headlines .

Loneliness and solitude are not the same , and the evidence suggests that self-reported loneliness has not been growing in recent decades.

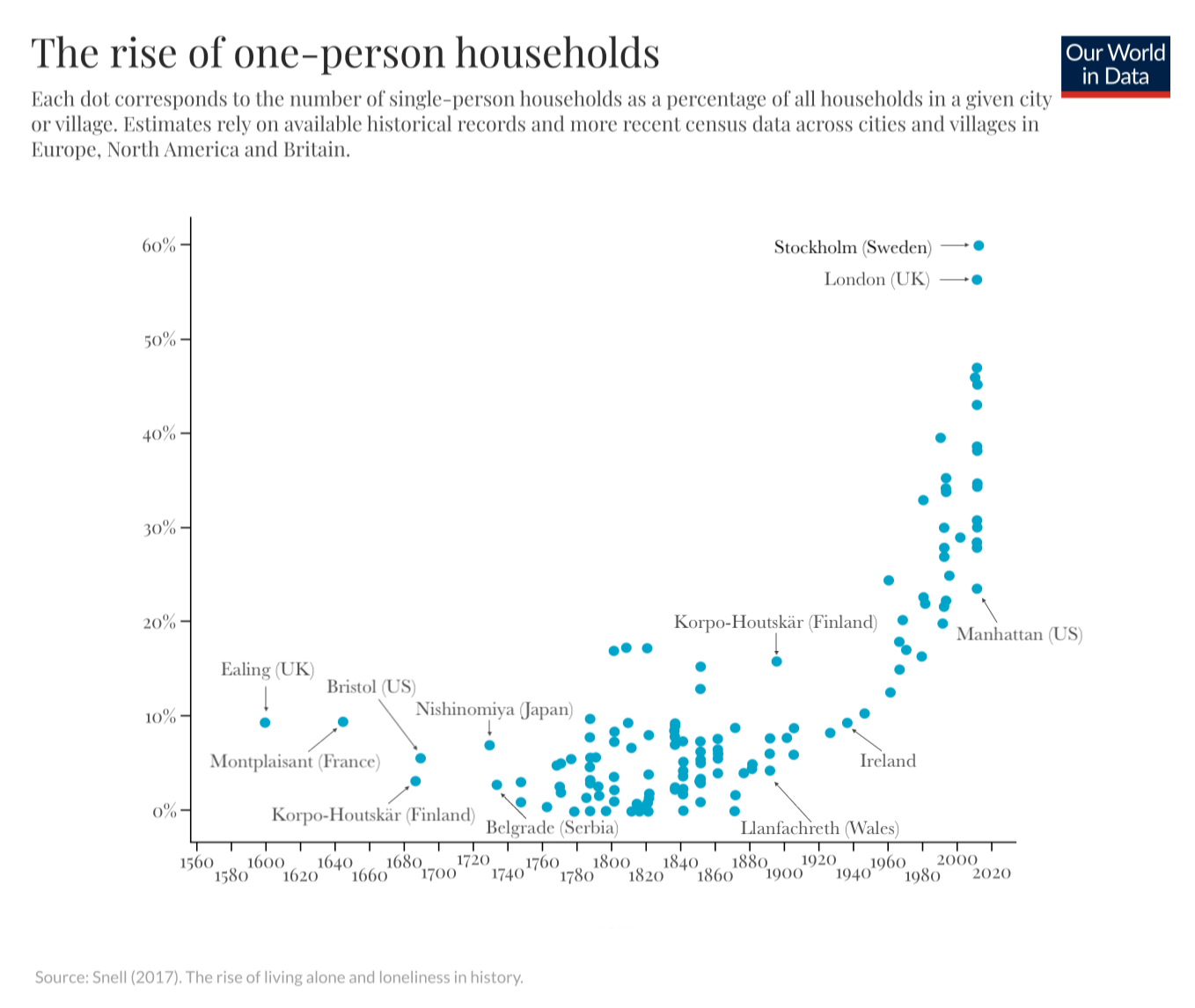

Historical perspective on people living alone: Evidence from rich countries

Historical records of inhabitants across villages and cities in today’s rich countries give us insights into how uncommon it was for people to live alone in the past.

The chart here, adapted from a paper by the historian Keith Snell, shows estimates of the share of single-person households across different places and times, using a selection of the available historical records and more recent census data. Each dot corresponds to an estimate for one settlement in Europe, North America, Japan, or Britain. 18

The share of one-person households remained fairly steady between the early modern period and through the 19th century – typically below 10%. Then, growth started in the twentieth century, accelerating in the 1960s.

The current prevalence of one-person households is unprecedented historically. The highest point recorded in this chart corresponds to Stockholm in 2012, where 60% of households consist of one person.

The rise of one-person households across the world

For recent decades, census data can be combined with data from large cross-country surveys to provide a global perspective on the proportion of households with only one member (i.e., the proportion of single-person households). This gives us a proxy for the prevalence of solitary living arrangements. 19

We produced this chart combining individual reports from statistical country offices, cross-country surveys such as the Demographic and Health Surveys , and estimates published in the EU’s Eurostat , the UN’s Demographic Year Books , and the Deutschland in Daten dataset.