Module 8: Delivering Your Speech

Mastering the location, learning objectives.

Describe techniques for adapting to the physical location of a speech.

Whenever you know you have to speak in a specific place, gather as much information as possible about the speaking space so that you can be prepared and make adjustments that fit the location. Always ask to have time to be in the space before the actual speech to do a rehearsal if time allows.

It’s good to get a sense of the room layout ahead of time, since certain spaces can require some adjustments.

What kinds of information should you acquire when you’ve been asked to speak? See the checklist of questions to ask your host below for a speech that is booked in advance.

- What is the size of the room? (Knowing the size of the room will allow you to adjust your visual aids to be seen in that room. It also allows you to consider how loudly you will need to speak to be heard.)

- How many people are expected to be in the audience? (Having this information allows you to prepare visuals that can be seen by the size of the audience anticipated. It also helps to know this information if you intend to pass out handouts, etc. You should also try to get the information about your audience demographics and their beliefs, attitudes, and values toward your subject. More on this in another section.)

- What is the audio-visual equipment available to be used and who will operate it? (This is critical to the success of the speech delivery. Find out how your visual aids can be displayed; if you can use PowerPoint or Google Slides; and if there’s a projector, pointer, etc.; and if you will be operating the slides or someone else will. You should also find out if microphones are used and/or expected. This will mean adjusting the movement of your speech if it is a handheld microphone that is corded or adjusting your voice volume if you are wearing a lavalier microphone on your lapel, etc.)

- Is there a podium? (Podiums are places where a speaker can set down their notecards. They are also sometimes near the console to operate the room’s computer. If you don’t want the podium, find out if it is removable.)

- When is a possible time to access the room and have a rehearsal? (Always ask for time to be in the space before the audience arrives to see the room layout, test your visuals, and set levels for your sound and speaking voice. If there are separate operators for sound and visuals, they should be at the rehearsal as well.)

For those speaking occasions when you don’t have any information and just have to walk into the space and speak, what should you be prepared for? Everything!

It’s a good idea to have a plan if the AV equipment doesn’t work or if it’s incompatible with your presentation method. Unless you’ve brought transparencies (!), a whole room full of overhead projectors won’t help.

Always have backups for your visual aids. If you’ve prepared a PowerPoint presentation or hope to show video clips, bring your own laptop just in case, but hope that you can use whatever equipment is on site. Put your visuals on a backed-up zip drive so that you can easily transfer it to whatever device or system may be in the room if a laptop connection is not available. Bring a printout of your visuals in case everything else fails and copies can be made as handouts. Have a plan for if your video doesn’t play or was suddenly taken down from YouTube. Prepare a summary of what the clip contained so you can at least narrate what would have happened or have a backup clip in mind so you can switch to it easily.

When you walk into the space, do a quick assessment of the number of audience seats and where they are located. This assessment is for your eye contact and vocal delivery purposes. As quickly as possible, get to wherever you will be operating your visual aids from and turn on everything and see if you can figure out how to operate it all. If not, try to get assistance from someone on site. It is better to lose a few minutes of speaking time and be able to do all you’ve planned than not.

If you feel like the place you are asked to speak from is really far from the audience, don’t be afraid to ask if the audience seating can be quickly reconfigured.

- Event Space, Intermediae Madrid. Authored by : Neil Cummings. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/6kpmTo . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Overhead projectors. Authored by : Sarah Stewart. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/aKfgB8 . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Mastering the Space. Authored by : Misti Wills with Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

Speech on Space

Space, the vast expanse above us, is a mystery waiting to be unraveled. It’s a place where stars twinkle and planets orbit, far beyond what your eyes can see.

You might wonder about the black void you see at night. It’s not empty but filled with galaxies, each teeming with billions of stars just like our sun.

1-minute Speech on Space

Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, imagine a place that’s always changing, always expanding, and full of secrets yet to be discovered. That place is space, the final frontier of exploration.

Think about the night sky. Each tiny dot of light you see is a distant star, many with planets just like our Earth orbiting around them. This shows us how vast space really is. It’s a place so big that even light, which travels incredibly fast, can take millions of years to get from one place to another.

Now let’s talk about the beauty of space. When astronauts look back at Earth from space, they don’t see any borders or countries. They see one planet, beautiful and fragile, suspended in the darkness. Space shows us that we are all connected, all living on the same tiny blue dot.

But space is more than just beautiful, it’s useful too. Satellites in space help us predict the weather, navigate our world, and even watch our favorite TV shows. This proves how space exploration can make our lives on Earth better.

Finally, space is the future. Someday, we might be able to live on other planets or meet beings from other worlds. By learning about space, we are opening doors to endless possibilities.

Space is vast, beautiful, useful, and full of potential. It’s our final frontier, a place that will always have new things to teach us, and new places to explore. Let’s look up at the stars and dream big, because in space, anything is possible. Thank you.

Also check:

- Essay on Space

- 10-lines on Space

2-minute Speech on Space

Good day! Let’s talk about something that’s been sparking human curiosity for centuries. It’s big, it’s vast, it’s full of mysteries – it’s the universe! Space, as we call it, is an endless expanse, much like an infinite dark blanket, sprinkled with bright stars.

In the first place, let’s discuss the stars in the sky. You see them every night, sparkling like little diamonds. They look tiny to us, but they’re actually gigantic balls of gas, burning a very, very long way away. Our very own Sun is also a star. It’s the closest one to us, and that’s why it appears so big and bright. Stars are important because they provide light and heat. They’re like the streetlights of the universe.

Secondly, let’s talk about the planets. We live on Earth, which is one of eight planets in our solar system. The others are Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. Each one is unique. For example, Mars, known as the Red Planet, and Venus, often called Earth’s twin. We’ve sent spacecraft to all these planets to learn more about them.

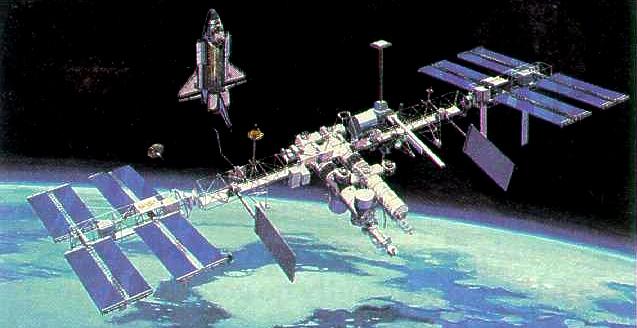

Next, let’s talk about something really exciting – space travel. Astronauts are brave explorers who get to go on amazing adventures in space. They travel in spacecraft and sometimes live in space stations, like the International Space Station. They do important work, like studying the effects of living in space and conducting experiments that help us understand more about our universe. Some astronauts have even walked on the moon!

Finally, let’s think about the future of space exploration. Scientists are working on ways for humans to live on other planets, like Mars. Can you imagine that? Living on a different planet! And who knows what else we might discover in the vastness of space. There could be other life forms out there, maybe even civilizations like ours.

Space is a truly fascinating subject. There’s so much we don’t know yet, and that’s what makes it so exciting. Every day, scientists are discovering new things about our universe. And who knows? Maybe one day, some of you will become those scientists, or even astronauts, exploring the unknown and making amazing discoveries. So, let’s keep looking up at the stars and dreaming about the endless possibilities that space holds for us. Thank you!

- Speech on Academic Excellence

- Speech on Academic Achievement Award

- Speech on Abraham Lincoln Freedom

We also have speeches on more interesting topics that you may want to explore.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

9 ways to use space in your presentation

by Olivia Mitchell | 9 comments

There are many benefits to movement in a presentation:

- It adds energy and variety to your presentation.

- It makes you look more confident – because people who are nervous are generally frozen in one spot.

- And as an added bonus, if you move, you may start to feel more confident. That’s partly because movement will help dissipate the extra adrenalin in your system.

Movement got a bad name because of university lecturers pacing up and down. Audiences are distracted by mindless, repetitive movement. Movement should be interspersed with stillness. That way, they both have more impact.

Incorporate movement in your presentation by planning different positions on the stage (or front of the room) that you’ll present from. In the theatre, this is called “ blocking “. Blocking is deciding on the position and movement of the characters as they move through the play. You can block your presentation too. Here are some ideas:

1. State your Key Message from the Power Position

Your Key Message is the core of your talk. Choose one spot where you will stand and state your Key Message. It should be dead centre, and close to the audience.

2. Map your structure on the stage

Using your physical space on the stage to map out your structure. It will help your audience anchor the different parts of your talk. Use these areas when you do a preview near the beginning of your presentation. Then return to that area of the stage for that part of the presentation.

3. Use a stage timeline

Where a story or explanation involves the passage of time, imagine a timeline across the stage and move along it to show the progression of time. Remember to make the past to the audience’s left – not your left.

4. Argue the pros and cons as if you were in a debate

In a debate, the people arguing for each side will stand at different sides of the stage. Although there’s only one of you, you can adopt this strategy. Stand on one side for the pros – and the other side for the cons.

5. Physically reflect the continuum of points of view

Points of view on a topic often exist along a continuum – from one extreme – to middle of the road – and out to the other extreme. Reflect this with where you stand on the stage as you describe each point of view.

6. Give each option it’s own spot

If you’re discussing a range of options, stand in a specific spot for each option as you describe it. When you refer back to an option later in your presentation, go back to that spot.

7. Story time

Have a general area of the stage for story-telling. When you’re telling a light-hearted story, it can be effective to move around as you’re talking. You’ll come across as chatty and conversational.

Where a story involves two or more characters in dialogue, have a specific spot where you deliver the lines of each character. Stay within the storytelling area.

8. Move close for emphasis

If you normally stay a couple of paces back from your audience, you can then exploit closeness for empashis. Moving close to people is powerful. Even intimidating. But you can stand really close to someone, and look elsewhere. You get the powerful effect without intimidation.

9. Dance with your Slides

Adding the display of slides is a complicating factor. To keep as much flexibility as possible, I recommend placing the datashow screen slightly off to the side. If the screen is in the middle, it’s easy to turn into a projectionist instead of a presenter. If it’s to the side, then you can still claim the power position. To avoid stepping into the beam of the datashow, stick some duct tape on the floor as a reminder. (Note: I generally have the screen to my right because I also use a flipchart which I like to have to my left, so that when I turn around to write on the flipchart, I don’t have to move to the other side of it. I’m right-handed – if you’re left-handed, you’d flip this arrangement around).

You’ll also need to be aware of blocking the view of some parts of the audience. With this arrangement if you move slightly back and to the side, it will allow everyone in the audience to see. When they’ve seen the slide, move back closer to the audience, as you’ll lose impact standing further back for a long period of time.

When you want to draw attention to a slide, move back to your datashow screen.

Explain your slides physically. Get in the beam. For a great example of explaining slides physically have a watch of Hans Rosling explaining statistics like you’ve never seen before. You’ll never use a wimpy laser pointer again!

Choose one or two of these ideas to implement to begin with. If possible, rehearse in the room that you’re presenting in, so that you can integrate the movements you want to make. Generally, it’s more natural and conversational to keep talking as you’re moving. But occasionally use the power of silence for more impact.

Using your space will add a new dimension to your presentations.

Free Course

How to tame your fear of public speaking.

In this video-training series (plus workbook with transcripts) you’ll learn:

- The three things you must know BEFORE you begin to tackle your fear of public speaking

- Why the positive-negative thought classification doesn’t work for fear of public speaking

- The two powerful self-talk tweaks that can make an immediate difference.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

I ask for your email address to deliver the course to you and so that I can keep on supporting and encouraging you with tips, ideas and inspiration. I will also let you know when my group program is open for enrolment. I will keep your email safe and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Hello Olivia,

I really enjoyed your text about space and movement in presentations. In fact, I made a summary in Spanish in my blog and linked to your post.

I wonder if I also could use and insert your images in my post or create another ones with spanish text.

Thanks! Carles.

Thanks for the tips! I will try and remember these when I am next up front speaking.

Good piece of information 🙂

Great hints! I’ll try them next time I teach a class!

wonderful tips for trainers and teachers thank you

Thanks for the stage time line explanation. I had to explain this to my Gavel Club kids for story telling and needed to get it right!

Great job. Very well said and explained. Really helpful and reliable indeed.Thanks for sharing this and keep up the good work, very much appreciated

hi good day

A good read

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- mark larson | - [...] are 9 ways to use space in your presentation, basically ways to use your body on stage while you’re…

- Crushing Krisis › Stuff I have bookmarked, but never investigated. - [...] How to use space in a presentation (Just now cribbed from MLarson; if I remember this exists I will…

- How to Look Authoritative | MC2TALKS - [...] For more ideas on moving such as mapping your structure, showing a timeline and picking a storytelling spot, check…

- ??????? ??????? ?? ??? ?? ???????? | ????????? ????? - [...] ???? ???? ??????? ? ??????? ????? ??:???????? ??????? ????? ??????? ????????? ???????? (1) ??????? ????????? ???????? (2)???????? ??? ??…

- Reaching My Objectives | Lindsay Zengler - [...] http://www.speakingaboutpresenting.com/delivery/9-ways-space-presentation/ [...]

- Should I Move While Delivering a Speech or Presentation? | Communication Matters - […] is an article by Olivia Mitchell on effective use of the […]

- Research on Goals – Aine Javier COMMS 101 - […] https://speakingaboutpresenting.com/delivery/9-ways-space-presentation/ […]

Need to be more relaxed when you deliver your next presentation?

Learn a system that will allow you to focus on engaging with your audience - not worrying about what you're saying.

Recent posts

- Why striving to be authentic can be a trap

- The first time is never the best

- The Need to be Knowledgeable

- Would you wear clothes that clash?

- An unconventional approach to overcoming the fear of public speaking

Connect With Me

Recommended Books

Click here to see my favorite presentation books.

I earn a small commission when you buy a book from this page. Thank you!

- Audience (22)

- Content (62)

- Delivery (31)

- Nervousness (30)

- Powerpoint (37)

- Presentation blogs (2)

- Presentation books (4)

- Presentation critiques (9)

- Presentation myths (6)

- Presentation philosophy (5)

- Presentation research (11)

- Presentation skills (23)

- Presenting with Twitter (10)

- Visual thinking (3)

How to Tame your Fear of Public Speaking

- Do you have to perform perfectly?

- Do you beat yourself up if you don't?

- Would you talk to a friend the way you talk to yourself?

- Does it make sense that if you changed the way you talked to yourself, you could reduce your fear of public speaking?

I will show you exactly how in this free video training series and workbook.

Discover more from Speaking about Presenting

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Speechwriting

9 Structure and Organization

Writing a Speech That Audiences Can Grasp

In this chapter . . .

For a speech to be effective, the material must be presented in a way that makes it not only engaging but easy for the audience to follow. Having a clear structure and a well-organized speech makes this possible. In this chapter we cover the elements of a well-structured speech, using transitions to connect each element, and patterns for organizing the order of your main points.

Have you had this experience? You have an instructor who is easy to take notes from because they help you see the main ideas and give you cues as to what is most important to write down and study for the test. On the other hand, you might have an instructor who tells interesting stories, says provocative things, and leads engaging discussions, but you have a tough time following where the instruction is going. If you’ve experienced either of these, you already know that structure and the organized presentation of material makes a big difference for listening and learning. The structure is like a house, which has essential parts like a roof, walls, windows, and doors. Organization is like the placement of rooms within the house, arranged for a logical and easy flow.

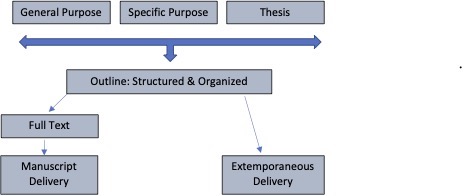

This chapter will teach you about creating a speech through an outlining process that involves structure and organization. In the earlier chapter Ways of Delivering Speeches , you learned about several different modes of speech delivery: impromptu, extemporaneous, and manuscript. Each of these suggests a different kind of speech document. An impromptu speech will have a very minimal document or none at all. An extemporaneous delivery requires a very thorough outline, and a manuscript delivery requires a fully written speech text. Here’s a crucial point to understand: Whether you plan to deliver extemporaneously or from a fully written text. The process of outlining is crucial. A manuscript is simply a thorough outline into which all the words have been written.

Four Elements of a Structured Speech

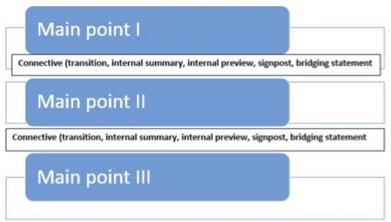

A well-structured speech has four distinct elements: introduction, body, connective statements, and conclusion. While this sounds simple, each of these elements has sub-elements and nuances that are important to understand. Introductions and conclusions are complex enough to warrant their own chapter and will be discussed in depth further on.

Introduction and Conclusion

The importance of a good introduction cannot be overstated. The clearer and more thorough the introduction, the more likely your audience will listen to the rest of the speech and not “turn off.” An introduction, which typically occupies 10-15% of your entire speech, serves many functions including getting the audience’s attention, establishing your credibility, stating your thesis, and previewing your main points.

Like an introduction, speech conclusions are essential. They serve the function of reiterating the key points of your speech and leave the audience with something to remember.

The elements of introductions and conclusions will be discussed in the following chapter. The remainder of this chapter is devoted to the body of the speech and its connectors.

The Body of a Speech

The body of a speech is comprised of several distinct groups of related information or arguments. A proper group is one where a) the group can be described in a single clear sentence, and b) there’s a logical relationship between everything within it. We call that describing sentence a main point . Speeches typically have several main points, all logically related to the thesis/central idea of the speech. Main points are followed by explanation, elaboration, and supporting evidence that are called sub-points .

Main Points

A main point in a speech is a complete sentence that states the topic for information that is logically grouped together. In a writing course, you may have learned about writing a paragraph topic sentence. This is typically the first sentence of a paragraph and states the topic of the paragraph. Speechwriting is similar. Whether you’re composing an essay with a paragraph topic sentences or a drafting a speech with main points, everything in the section attached to the main point should logically pertain to it. If not, then the information belongs under a different main point. Let’s look at an example of three main points:

General Purpose: To persuade

Specific Purpose: To motivate my classmates in English 101 to participate in a study abroad program.

Thesis: A semester-long study abroad experience produces lifelong benefits by teaching you about another culture, developing your language skills, and enhancing your future career prospects.

Main point #1: A study abroad experience allows you to acquire firsthand experience of another culture through classes, extra-curricular activities, and social connections.

Main point #2: You’ll turbocharge your acquisition of second language skills through an immersive experience living with a family.

Main point #3: A study abroad experience on your resume shows that you have acquired the kind of language and cultural skills that appeal to employers in many sectors.

Notice that each main point is expressed in a complete sentence, not merely #1 Culture; #2 Language; #3 Career. One-word signals are useless as a cue for speaking. Additionally, students are often tempted to write main points as directions to themselves, “Talk about the health department” or “Mention the solution.” This isn’t helpful for you, either. Better: “The health department provides many services for low-income residents” says something we can all understand.

Finally, the important thing to understand about speechwriting is that listeners have limits as to how many categories of information they can keep in mind. The number of main points that can be addressed in any speech is determined by the time allotted for a speech but is also affected by the fact that speeches are limited in their ability to convey substantial amounts of information. For a speech of five to seven minutes, three or four main points are usually enough. More than that would be difficult to manage—for both speaker and audience.

Obviously, creating your main points isn’t the end of the story. Each main point requires additional information or reinforcement. We call these sub-points. Sub-points provide explanation, detail, elaboration, and/or supporting evidence. Consider main point #1 in the previous example, now with sub-points:

Sub-point A: How a country thinks about education is a window into the life of that culture. While on a study abroad program, you’ll typically take 3-5 classes at foreign universities, usually with local professors. This not only provides new learning, but it opens your eyes to different modes of education.

Sub-point B: Learning about a culture isn’t limited to the classroom. Study abroad programs include many extra-curricular activities that introduce you to art, food, music, sports, and other everyday elements of a country’s culture. These vary depending on the program and there’s something for everyone! The website gooverseas.com provides information on hundreds of programs.

Sub-point C: The opportunity to socialize with peers in other countries is one of most attractive elements of studying abroad. You may form friendships that will last a lifetime. “I have made valuable connections in a country I hope to return to someday” according to a blog post by Rachel Smith, a student at the University of Kansas. [1]

Notice that each of these sub-points pertains to the main point. The sub-points contribute to the main point by providing explanation, detail, elaboration, and/or supporting evidence. Now imagine you had a fourth sub-point:

Sub-point D: And while doing all that socializing, you’ll really improve your language skills.

Does that sub-point belong to main point #1? Or should it be grouped with main point#2 or main point #3?

Connective Statements

Connectives or “connective statements” are broad terms that encompass several types of statements or phrases. They are designed to help “connect” parts of your speech to make it easier for audience members to follow. Connectives are tools that add to the planned redundancy, and they are methods for helping the audience listen, retain information, and follow your structure. In fact, it’s one thing to have a well-organized speech. It’s another for the audience to be able to “consume” or understand that organization.

Connectives in general perform several functions:

- Remind the audience of what has come before

- Remind the audience of the central focus or purpose of the speech

- Forecast what is coming next

- Help the audience have a sense of context in the speech—where are we?

- Explain the logical connection between the previous main idea(s) and next one or previous sub-points and the next one

- Explain your own mental processes in arranging the material as you have

- Keep the audience’s attention through repetition and a sense of movement

Connective statement can include “internal summaries,” “internal previews” “signposts” and “bridging or transition statements.” Each of these helps connect the main ideas of your speech for the audience, but they have different emphases and are useful for different types of speeches.

Types of connectives and examples

Internal summaries emphasize what has come before and remind the audience of what has been covered.

“So far I have shown how the designers of King Tut’s burial tomb used the antechamber to scare away intruders and the second chamber to prepare royal visitors for the experience of seeing the sarcophagus.”

Internal previews let your audience know what is coming up next in the speech and what to expect regarding the content of your speech.

“In this next part of the presentation I will share with you what the truly secret and valuable part of the King Tut’s pyramid: his burial chamber and the treasury.”

Signposts emphasize physical movement through the speech content and let the audience know exactly where they are. Signposting can be as simple as “First,” “Next,” “Lastly” or numbers such as “First,” “Second,” Third,” and “Fourth.” Signposting is meant to be a brief way to let your audience know where they are in the speech. It may help to think of these like the mile markers you see along interstates that tell you where you’re and how many more miles you will travel until you reach your destination.

“The second aspect of baking chocolate chip cookies is to combine your ingredients in the recommended way.”

Bridging or transition statements emphasize moving the audience psychologically to the next step.

“I have mentioned two huge disadvantages to students who don’t have extracurricular music programs. Let me ask: Is that what we want for our students? If not, what can we do about it?”

They can also serve to connect seemingly disconnected (but related) material, most commonly between your main points.

“After looking at how the Cherokee Indians of the North Georgia mountain region were politically important until the 1840s and the Trail of Tears, we can compare their experience with that of the Indians of Central Georgia who did not assimilate in the same way as the Cherokee.”

At a minimum, a bridge or transition statement is saying, “Now that we have looked at (talked about, etc.) X, let’s look at Y.”

There’s no standard format for connectives. However, there are a few pieces of advice to keep in mind about them:

First, connectives are for connecting main points. They are not for providing evidence, statistics, stories, examples, or new factual information for the supporting points of the main ideas of the speech.

Second, while connectives in essay writing can be relatively short—a word or phrase, in public speaking, connectives need to be a sentence or two. When you first start preparing and practicing connectives, you may feel that you’re being too obvious with them, and they are “clunky.” Some connectives may seem to be hitting the audience over the head with them like a hammer. While it’s possible to overdo connectives, it’s less likely than you would think. The audience will appreciate them, and as you listen to your classmates’ speeches, you’ll become aware of when they are present and when they are absent.

Lack of connectives results in hard-to-follow speeches where the information seems to come up unexpectedly or the speaker seems to jump to something new without warning or clarification.

Finally, you’ll also want to vary your connectives and not use the same one all the time. Remember that there are several types of connectives.

Patterns of Organization

At the beginning of this chapter, you read the analogy that a speech structure is like a house and organization is like the arrangement of the rooms. So far, we have talked about structure. The introduction, body, main point, sub-point, connectives—these are the house. But what about the arrangement of the rooms? How will you put your main points in a logical order?

There are some standard ways of organizing the body of a speech. These are called “patterns of organization.” In each of the examples below, you’ll see how the specific purpose gives shape to the organization of the speech and how each one exemplifies one of the six main organizational patterns.

Please note that these are simple, basic outlines for example purposes. The actual content of the speech outline or manuscript will be much further developed.

Chronological Pattern

Specific Purpose: To describe to my classmates the four stages of rehabilitation in addiction recovery.

Main Points:

- The first stage is acknowledging the problem and entering treatment.

- The second stage is early abstinence, a difficult period in the rehabilitation facility.

- The third stage is maintaining abstinence after release from the rehab facility.

- The fourth stage is advanced recovery after a period of several years.

The example above uses what is termed the chronological pattern of organization . Chronological always refers to time order. Organizing your main points chronologically is usually appropriate for process speeches (how-to speeches) or for informational speeches that emphasize how something developed from beginning to end. Since the specific purpose in the example above is about stages, it’s necessary to put the four stages in the right order. It would make no sense to put the fourth stage second and the third stage first.

Chronological time can be long or short. If you were giving a speech about the history of the Civil Rights Movement, that period would cover several decades; if you were giving a speech about the process of changing the oil in a car, that process takes less than an hour. Whether the time is long or short, it’s best to avoid a simple, chronological list of steps or facts. A better strategy is to put the information into three to five groups so that the audience has a framework. It would be easy in the case of the Civil Rights Movement to list the many events that happened over more than two decades, but that could be overwhelming for the audience. Instead, your chronological “grouping” might be:

- The movement saw African Americans struggling for legal recognition before the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision.

- The movement was galvanized and motivated by the 1955-1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott.

- The movement saw its goals met in the Civil Rights Act of 1965.

In this way, the chronological organization isn’t an overwhelming list of events. It focuses the audience on three events that pushed the Civil Rights movement forward.

Spatial Pattern

You can see that chronological is a highly-used organizational structure, since one of the ways our minds work is through time-orientation—past, present, future. Another common thought process is movement in space or direction, which is called the spatial pattern . For example:

Specific Purpose: To explain to my classmates the three regional cooking styles of Italy.

- In the mountainous region of the North, the food emphasizes cheese and meat.

- In the middle region of Tuscany, the cuisine emphasizes grains and olives.

- In the southern region and Sicily, the diet is based on fish and seafood.

In this example, the content is moving from northern to southern Italy, as the word “regional” would indicate. For a more localized example:

Specific Purpose: To explain to my classmates the layout of the White House.

- The East Wing includes the entrance ways and offices for the First Lady.

- The most well-known part of the White House is the West Wing.

- The residential part of the White House is on the second floor. (The emphasis here is the movement a tour would go through.)

For an even more localized example:

Specific Purpose: To describe to my Anatomy and Physiology class the three layers of the human skin.

- The outer layer is the epidermis, which is the outermost barrier of protection.

- The second layer beneath is the dermis.

- The third layer closest to the bone is the hypodermis, made of fat and connective tissue.

Topical / Parts of the Whole Pattern

The topical organizational pattern is probably the most all-purpose, in that many speech topics could use it. Many subjects will have main points that naturally divide into “types of,” “kinds of,” “sorts of,” or “categories of.” Other subjects naturally divide into “parts of the whole.” However, as mentioned previously, you want to keep your categories simple, clear, distinct, and at five or fewer.

Specific Purpose: To explain to my first-year students the concept of SMART goals.

- SMART goals are specific and clear.

- SMART goals are measurable.

- SMART goals are attainable or achievable.

- SMART goals are relevant and worth doing.

- SMART goals are time-bound and doable within a time period.

Specific Purpose: To explain the four characteristics of quality diamonds.

- Valuable diamonds have the characteristic of cut.

- Valuable diamonds have the characteristic of carat.

- Valuable diamonds have the characteristic of color.

- Valuable diamonds have the characteristic of clarity.

Specific Purpose: To describe to my audience the four main chambers of a human heart.

- The first chamber in the blood flow is the right atrium.

- The second chamber in the blood flow is the right ventricle.

- The third chamber in the blood flow is the left atrium.

- The fourth chamber in the blood flow and then out to the body is the left ventricle.

At this point in discussing organizational patterns and looking at these examples, two points should be made about them and about speech organization in general:

First, you might look at the example about the chambers of the heart and say, “But couldn’t that be chronological, too, since that’s the order of the blood flow procedure?” Yes, it could. There will be times when a specific purpose could work with two different organizational patterns. In this case, it’s just a matter of emphasis. This speech emphasizes the anatomy of the heart, and the organization is “parts of the whole.” If the speech’s specific purpose were “To explain to my classmates the flow of blood through the chambers of the heart,” the organizational pattern would emphasize chronological, altering the pattern.

Another principle of organization to think about when using topical organization is “climax” organization. That means putting your strongest argument or most important point last when applicable. For example:

Specific purpose: To defend before my classmates the proposition that capital punishment should be abolished in the United States.

- Capital punishment does not save money for the justice system.

- Capital punishment does not deter crime in the United States historically.

- Capital punishment has resulted in many unjust executions.

In most people’s minds, “unjust executions” is a bigger reason to end a practice than the cost, since an unjust execution means the loss of an innocent life and a violation of our principles. If you believe Main Point III is the strongest argument of the three, putting it last builds up to a climax.

Cause & Effect Pattern

If the specific purpose mentions words such as “causes,” “origins,” “roots of,” “foundations,” “basis,” “grounds,” or “source,” it’s a causal order; if it mentions words such as “effects,” “results,” “outcomes,” “consequences,” or “products,” it’s effect order. If it mentions both, it would of course be cause/effect order. This example shows a cause/effect pattern:

Specific Purpose: To explain to my classmates the causes and effects of schizophrenia.

- Schizophrenia has genetic, social, and environmental causes.

- Schizophrenia has educational, relational, and medical effects.

Problem-Solution Pattern

The principle behind the problem-solution pattern is that if you explain a problem to an audience, you shouldn’t leave them hanging without solutions. Problems are discussed for understanding and to do something about them. This is why the problem-solution pattern is often used for speeches that have the objective of persuading an audience to take action.

When you want to persuade someone to act, the first reason is usually that something needs fixing. Let’s say you want the members of the school board to provide more funds for music at the three local high schools in your county. What is missing because music or arts are not funded? What is the problem ?

Specific Purpose: To persuade the members of the school board to take action to support the music program at the school.

- Students who don’t have extracurricular music in their lives have lower SAT scores.

- Schools that don’t have extracurricular music programs have more gang violence and juvenile delinquency.

- $120,000 would go to bands.

- $80,000 would go to choral programs.

Of course, this is a simple outline, and you would need to provide evidence to support the arguments, but it shows how the problem-solution pattern works.

Psychologically, it makes more sense to use problem-solution rather than solution-problem. The audience will be more motivated to listen if you address needs, deficiencies, or problems in their lives rather than giving them solutions first.

Problem-Cause-Solution Pattern

A variation of the problem-solution pattern, and one that sometimes requires more in-depth exploration of an issue, is the “problem-cause-solution” pattern. If you were giving a speech on the future extinction of certain animal species, it would be insufficient to just explain that numbers of species are about to become extinct. Your second point would logically have to explain the cause behind this happening. Is it due to climate change, some type of pollution, encroachment on habitats, disease, or some other reason? In many cases, you can’t really solve a problem without first identifying what caused the problem.

Specific Purpose: To persuade my audience that the age to obtain a driver’s license in the state of Georgia should be raised to 18.

- There’s a problem in this country with young drivers getting into serious automobile accidents leading to many preventable deaths.

- One of the primary causes of this is younger drivers’ inability to remain focused and make good decisions due to incomplete brain development.

- One solution that will help reduce the number of young drivers involved in accidents would be to raise the age for obtaining a driver’s license to 18.

Some Additional Principles of Speech Organization

It’s possible that you may use more than one of these organizational patterns within a single speech. You should also note that in all the examples to this point (which have been kept simple for the purpose of explanation), each main point is relatively equal in emphasis; therefore, the time spent on each should be equal as well. You would not want your first main point to be 30 seconds long, the second one to be 90 seconds, and the third 3 minutes. For example:

Specific Purpose: To explain to my classmates the rules of baseball.

- Baseball has rules about equipment.

- Baseball has rules about the numbers of players.

- Baseball has rules about play.

Main Point #2 isn’t really equal in size to the other two. There’s a great deal you could say about equipment and even more about the rules of playing baseball, but the number of players would take you about ten seconds to say. If Main Point #2 were “Baseball has rules about the positions on the field,” that would make more sense and be closer in level of importance to the other two.

The organization of your speech may not be the most interesting part to think about, but without it, great ideas will seem jumbled and confusing to your audience. Even more, good connectives will ensure your audience can follow you and understand the logical connections you’re making with your main ideas. Finally, because your audience will understand you better and perceive you as organized, you’ll gain more credibility as a speaker if you’re organized. A side benefit to learning to be an organized public speaker is that your writing skills will improve, specifically your organization and sentence structure.

Roberto is thinking about giving an informative speech on the status of HIV-AIDS currently in the U.S. He has different ideas about how to approach the speech. Here are his four main thoughts:

- pharmaceutical companies making drugs available in the developing world

- changes in attitudes toward HIV-AIDS and HIV-AIDS patients over the last three decades

- how HIV affects the body of a patient

- major breakthroughs in HIV-AIDS treatment

Assuming all these subjects would be researchable and appropriate for the audience, write specific purpose statements for each. What organizational patterns would he probably use for each specific purpose?

Media Attributions

- Speech Structure Flow © Mechele Leon is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Connectives

- https://blog-college.ku.edu/tag/study-abroad-stories/ ↵

Public Speaking as Performance Copyright © 2023 by Mechele Leon is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10.2 Using Common Organizing Patterns

Learning objectives.

- Differentiate among the common speech organizational patterns: categorical/topical, comparison/contrast, spatial, chronological, biographical, causal, problem-cause-solution, and psychological.

- Understand how to choose the best organizational pattern, or combination of patterns, for a specific speech.

Twentyfour Students – Organization makes you flow – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Previously in this chapter we discussed how to make your main points flow logically. This section is going to provide you with a number of organization patterns to help you create a logically organized speech. The first organization pattern we’ll discuss is categorical/topical.

Categorical/Topical

By far the most common pattern for organizing a speech is by categories or topics. The categories function as a way to help the speaker organize the message in a consistent fashion. The goal of a categorical/topical speech pattern is to create categories (or chunks) of information that go together to help support your original specific purpose. Let’s look at an example.

In this case, we have a speaker trying to persuade a group of high school juniors to apply to attend Generic University. To persuade this group, the speaker has divided the information into three basic categories: what it’s like to live in the dorms, what classes are like, and what life is like on campus. Almost anyone could take this basic speech and specifically tailor the speech to fit her or his own university or college. The main points in this example could be rearranged and the organizational pattern would still be effective because there is no inherent logic to the sequence of points. Let’s look at a second example.

In this speech, the speaker is talking about how to find others online and date them. Specifically, the speaker starts by explaining what Internet dating is; then the speaker talks about how to make Internet dating better for her or his audience members; and finally, the speaker ends by discussing some negative aspects of Internet dating. Again, notice that the information is chunked into three categories or topics and that the second and third could be reversed and still provide a logical structure for your speech

Comparison/Contrast

Another method for organizing main points is the comparison/contrast speech pattern . While this pattern clearly lends itself easily to two main points, you can also create a third point by giving basic information about what is being compared and what is being contrasted. Let’s look at two examples; the first one will be a two-point example and the second a three-point example.

If you were using the comparison/contrast pattern for persuasive purposes, in the preceding examples, you’d want to make sure that when you show how Drug X and Drug Y differ, you clearly state why Drug X is clearly the better choice for physicians to adopt. In essence, you’d want to make sure that when you compare the two drugs, you show that Drug X has all the benefits of Drug Y, but when you contrast the two drugs, you show how Drug X is superior to Drug Y in some way.

The spatial speech pattern organizes information according to how things fit together in physical space. This pattern is best used when your main points are oriented to different locations that can exist independently. The basic reason to choose this format is to show that the main points have clear locations. We’ll look at two examples here, one involving physical geography and one involving a different spatial order.

If you look at a basic map of the United States, you’ll notice that these groupings of states were created because of their geographic location to one another. In essence, the states create three spatial territories to explain.

Now let’s look at a spatial speech unrelated to geography.

In this example, we still have three basic spatial areas. If you look at a model of the urinary system, the first step is the kidney, which then takes waste through the ureters to the bladder, which then relies on the sphincter muscle to excrete waste through the urethra. All we’ve done in this example is create a spatial speech order for discussing how waste is removed from the human body through the urinary system. It is spatial because the organization pattern is determined by the physical location of each body part in relation to the others discussed.

Chronological

The chronological speech pattern places the main idea in the time order in which items appear—whether backward or forward. Here’s a simple example.

In this example, we’re looking at the writings of Winston Churchill in relation to World War II (before, during, and after). By placing his writings into these three categories, we develop a system for understanding this material based on Churchill’s own life. Note that you could also use reverse chronological order and start with Churchill’s writings after World War II, progressing backward to his earliest writings.

Biographical

As you might guess, the biographical speech pattern is generally used when a speaker wants to describe a person’s life—either a speaker’s own life, the life of someone they know personally, or the life of a famous person. By the nature of this speech organizational pattern, these speeches tend to be informative or entertaining; they are usually not persuasive. Let’s look at an example.

In this example, we see how Brian Warner, through three major periods of his life, ultimately became the musician known as Marilyn Manson.

In this example, these three stages are presented in chronological order, but the biographical pattern does not have to be chronological. For example, it could compare and contrast different periods of the subject’s life, or it could focus topically on the subject’s different accomplishments.

The causal speech pattern is used to explain cause-and-effect relationships. When you use a causal speech pattern, your speech will have two basic main points: cause and effect. In the first main point, typically you will talk about the causes of a phenomenon, and in the second main point you will then show how the causes lead to either a specific effect or a small set of effects. Let’s look at an example.

In this case, the first main point is about the history and prevalence of drinking alcohol among Native Americans (the cause). The second point then examines the effects of Native American alcohol consumption and how it differs from other population groups.

However, a causal organizational pattern can also begin with an effect and then explore one or more causes. In the following example, the effect is the number of arrests for domestic violence.

In this example, the possible causes for the difference might include stricter law enforcement, greater likelihood of neighbors reporting an incident, and police training that emphasizes arrests as opposed to other outcomes. Examining these possible causes may suggest that despite the arrest statistic, the actual number of domestic violence incidents in your city may not be greater than in other cities of similar size.

Problem-Cause-Solution

Another format for organizing distinct main points in a clear manner is the problem-cause-solution speech pattern . In this format you describe a problem, identify what you believe is causing the problem, and then recommend a solution to correct the problem.

In this speech, the speaker wants to persuade people to pass a new curfew for people under eighteen. To help persuade the civic group members, the speaker first shows that vandalism and violence are problems in the community. Once the speaker has shown the problem, the speaker then explains to the audience that the cause of this problem is youth outside after 10:00 p.m. Lastly, the speaker provides the mandatory 10:00 p.m. curfew as a solution to the vandalism and violence problem within the community. The problem-cause-solution format for speeches generally lends itself to persuasive topics because the speaker is asking an audience to believe in and adopt a specific solution.

Psychological

A further way to organize your main ideas within a speech is through a psychological speech pattern in which “a” leads to “b” and “b” leads to “c.” This speech format is designed to follow a logical argument, so this format lends itself to persuasive speeches very easily. Let’s look at an example.

In this speech, the speaker starts by discussing how humor affects the body. If a patient is exposed to humor (a), then the patient’s body actually physiologically responds in ways that help healing (b—e.g., reduces stress, decreases blood pressure, bolsters one’s immune system, etc.). Because of these benefits, nurses should engage in humor use that helps with healing (c).

Selecting an Organizational Pattern

Each of the preceding organizational patterns is potentially useful for organizing the main points of your speech. However, not all organizational patterns work for all speeches. For example, as we mentioned earlier, the biographical pattern is useful when you are telling the story of someone’s life. Some other patterns, particularly comparison/contrast, problem-cause-solution, and psychological, are well suited for persuasive speaking. Your challenge is to choose the best pattern for the particular speech you are giving.

You will want to be aware that it is also possible to combine two or more organizational patterns to meet the goals of a specific speech. For example, you might wish to discuss a problem and then compare/contrast several different possible solutions for the audience. Such a speech would thus be combining elements of the comparison/contrast and problem-cause-solution patterns. When considering which organizational pattern to use, you need to keep in mind your specific purpose as well as your audience and the actual speech material itself to decide which pattern you think will work best.

Key Takeaway

- Speakers can use a variety of different organizational patterns, including categorical/topical, comparison/contrast, spatial, chronological, biographical, causal, problem-cause-solution, and psychological. Ultimately, speakers must really think about which organizational pattern best suits a specific speech topic.

- Imagine that you are giving an informative speech about your favorite book. Which organizational pattern do you think would be most useful? Why? Would your answer be different if your speech goal were persuasive? Why or why not?

- Working on your own or with a partner, develop three main points for a speech designed to persuade college students to attend your university. Work through the preceding organizational patterns and see which ones would be possible choices for your speech. Which organizational pattern seems to be the best choice? Why?

- Use one of the common organizational patterns to create three main points for your next speech.

Stand up, Speak out Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Building and Organizing Your Speech

Learning objectives.

- Understand how to make the transition from a specific purpose to a series of main points.

- Explain how to prepare meaningful main points.

- Understand how to choose the best organizational pattern, or combination of patterns, for a specific speech.

- Understand how to use a variety of strategies to help audience members keep up with a speech’s content: internal previews, internal summaries, and signposts.

Siddie Nam – Thinking – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

In a series of ground-breaking studies conducted during the 1950s and 1960s, researchers started investigating how a speech’s organization was related to audience perceptions of those speeches. The first study, conducted by Raymond Smith in 1951, randomly organized the parts of a speech to see how audiences would react. Not surprisingly, when speeches were randomly organized, the audience perceived the speech more negatively than when audiences were presented with a speech with a clear, intentional organization. Smith also found that audiences who listened to unorganized speeches were less interested in those speeches than audiences who listened to organized speeches (Smith, 1951). Thompson furthered this investigation and found that it was harder for audiences to recall information after an unorganized speech. Basically, people remember information from speeches that are clearly organized, and they forget information from speeches that are poorly organized (Thompson, 1960). A third study by Baker found that when audiences were presented with a disorganized speaker, they were less likely to be persuaded, and saw the disorganized speaker as lacking credibility (Baker, 1965).

These three critical studies make the importance of organization very clear. When speakers are organized they are perceived as credible. When speakers are not organized, their audiences view the speeches negatively, are less likely to be persuaded, and don’t remember specific information from the speeches after the fact.

We start this chapter by discussing these studies because we want you to understand the importance of speech organization to real audiences. This chapter will help you learn organization so that your speech with have its intended effect. In this chapter, we are going to discuss the basics of organizing the body of your speech.

Determining Your Main Ideas

While speeches take many different forms, they are often discussed as having an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. The introduction establishes the topic and wets your audience’s appetite, and the conclusion wraps everything up at the end of your speech. The real “meat” of your speech happens in the body. In this section, we’re going to discuss how to think strategically about structuring the body of your speech.

We like the word strategic because it refers to determining what is essential to the overall plan or purpose of your speech. Too often, new speakers throw information together and stand up and start speaking. When that happens, audience members are left confused, and the reason for the speech may get lost. To avoid being seen as disorganized, we want you to start thinking critically about the organization of your speech. In this section, we will discuss how to take your speech from a specific purpose to creating the main points of your speech.

What Is Your Specific Purpose?

Before we discuss how to determine the main points of your speech, we want to revisit your speech’s specific purpose, which we discussed in detail in Chapter 4 “Topic, Purpose, and Thesis”. Recall that a speech can have one of three general purposes: to inform, to persuade, or to entertain. The general purpose refers to the broad goal for creating and delivering the speech. The specific purpose, on the other hand, starts with one of those broad goals (inform, persuade, or entertain) and then further informs the listener about the who , what , when , where , why , and how of the speech.

The specific purpose is stated as a sentence incorporating the general purpose, the specific audience for the speech, and a prepositional phrase that summarizes the topic. Suppose you are going to give a speech about using open-source software. Here are three examples (each with a different general purpose and a different audience):

In each of these three examples, you’ll notice that the general topic is the same, open-source software, but the specific purpose is different because the speech has a different general purpose and a different audience. Before you can think strategically about organizing the body of your speech, you need to know what your specific purpose is. If you have not yet written a specific purpose for your current speech, please go ahead and write one now.

From Specific Purpose to Main Points

Once you’ve written down your specific purpose, you can start thinking about the best way to turn that specific purpose into a series of main points. Main points are the key ideas you present to enable your speech to accomplish its specific purpose. In this section, we’re going to discuss how to determine your main points and how to organize those main points into a coherent, strategic speech.

Main Points are the key ideas you present to enable your speech to accomplish its specific purpose.

How Many Main Points Do I Need?

While there is no magic number for how many main points a speech should have, speech experts generally agree that the fewer the number of main points the better. First and foremost, experts on the subject of memory have consistently shown that people don’t tend to remember very much after they listen to a message or leave a conversation (Bostrom & Waldhart, 1988). While many different factors can affect a listener’s ability to retain information after a speech, how the speech is organized is an important part of that process (Dunham, 1964; Smith, 1951; Thompson, 1960). For the speeches you will be delivering in a typical public speaking class, you will usually have just two or three main points. If your speech is less than three minutes long, then two main points will probably work best. If your speech is between three and ten minutes in length, then it makes more sense to use three main points.

You may be wondering why we are recommending only two or three main points. The reason comes straight out of the research on listening. According to LeFrancois, people are more likely to remember information that is meaningful, useful, and of interest to them; different or unique; organized; visual; and simple (LeFrancois, 1999). Two or three main points are much easier for listeners to remember than ten or even five. In addition, if you have two or three main points, you’ll be able to develop each one with examples, statistics, or other forms of support. Including support for each point will make your speech more interesting and more memorable for your audience.

Narrowing Down Your Main Points

When you write your specific purpose and review the research you have done on your topic, you will probably find yourself thinking of quite a few points that you’d like to make in your speech. Whether that’s the case or not, we recommend taking a few minutes to brainstorm and develop a list of points. In brainstorming, your goal is simply to think of as many different points as you can, not to judge how valuable or vital they are. What information does your audience need to know to understand your topic? What information does your speech need to convey to accomplish its specific purpose? Consider the following example:

Now that you have brainstormed and developed a list of possible points, how do you go about narrowing them down to just two or three main ones? Remember, your main points are the key ideas that help build your speech. When you look over the preceding list, you can then start to see that many of the points are related to one another. Your goal in narrowing down your main points is to identify which individual, potentially minor points can be combined to make main points. This process is called chunking because it involves taking smaller chunks of information and putting them together with like chunks to create more fully developed chunks of information. Before reading our chunking of the preceding list, see if you can determine three large chunks out of the list (note that not all chunks are equal).

Chunking involves taking smaller chunks of information and putting them together with like chunks to create more fully developed chunks of information.

You may notice that in the preceding list, the number of subpoints under each of the three main points is a little disjointed or the topics don’t go together clearly. That’s all right. Remember that these are just general ideas at this point. It’s also important to remember that there is often more than one way to organize a speech. Some of these points could be left out and others developed more fully, depending on the purpose and audience. We’ll develop the preceding main points more fully in a moment.

Helpful Hints for Preparing Your Main Points

Now that we’ve discussed how to take a specific purpose and turn it into a series of main points, here are some helpful hints for creating your main points.

Uniting Your Main Points

Once you’ve generated a possible list of main points, you want to ask yourself this question: “When you look at your main points, do they fit together?” For example, if you look at the three preceding main points (school districts use software in their operations; what is open-source software; name some specific open-source software packages that may be appropriate for these school administrators to consider), ask yourself, “Do these main points help my audience understand my specific purpose?”

Suppose you added a fourth main point about open-source software for musicians—would this fourth main point go with the other three? Probably not. While you may have a strong passion for open-source music software, that main point is extraneous information for the speech you are giving. It does not help accomplish your specific purpose, so you’d need to toss it out.

Keeping Your Main Points Separate

The next question to ask yourself about your main points is whether they overlap too much. While some overlap may happen naturally because of the singular nature of a specific topic, the information covered within each main point should be clearly distinct from the other main points. Imagine you’re giving a speech with the specific purpose “to inform my audience about the health reasons for eating apples and oranges.” You could then have three main points: that eating fruits is healthy, that eating apples is healthy, and that eating oranges is healthy. While the two points related to apples and oranges are clearly distinct, both of those main points would probably overlap too much with the first point “that eating fruits is healthy,” so you would probably decide to eliminate the first point and focus on the second and third. On the other hand, you could keep the first point and then develop two new points giving additional support to why people should eat fruit.

Balancing Main Points

One of the biggest mistakes some speakers make is to spend most of their time talking about one of their main points, completely neglecting their other main points. To avoid this mistake, organize your speech to spend roughly the same amount of time on each main point. If you find that one of your main points is simply too large, you may need to divide that main point into two main points and consolidate your other main points into a single main point.

Let’s see if our preceding example is balanced (school districts use software in their operations; what is open-source software; name some specific open-source software packages that may be appropriate for these school administrators to consider). What do you think? The answer depends on how much time a speaker will have to talk about each of these main points. If you have an hour to speak, then you may find that these three main points are balanced. However, you may also find them wildly unbalanced if you only have five minutes to speak because five minutes is not enough time to even explain what open-source software is. If that’s the case, then you probably need to rethink your specific purpose to ensure that you can cover the material in the allotted time.

Creating Parallel Structure for Main Points

Another major question to ask yourself about your main points is whether or not they have a parallel structure. By parallel structure , we mean that you should structure your main points so that they all sound similar. When all your main points sound similar, it’s easier for your audiences to remember your main points and retain them for later. Let’s look at our sample (school districts use software in their operations; what is open-source software; name some specific open-source software packages that may be appropriate for these school administrators to consider). Notice that the first and third main points are statements, but the second one is a question. We have an example here of main points that are not parallel in structure. You could fix this in one of two ways. You could make them all questions: what are some common school district software programs; what is open-source software; and what are some specific open-source software packages that may be appropriate for these school administrators to consider. Or you could turn them all into statements: school districts use software in their operations; define and describe open-source software; name some specific open-source software packages that may be appropriate for these school administrators to consider. Either of these changes will make the grammatical structure of the main points parallel.

Parallel structure means structuring your main points so that they all sound similar.

Maintaining Logical Flow of Main Points

The last question you want to ask yourself about your main points is whether the main points make sense in the order you’ve placed them. The next section goes into more detail of common organizational patterns for speeches, but for now, we want you to think logically about the flow of your main points. When you look at your main points, can you see them as progressive, or does it make sense to talk about one first, another one second, and the final one last? If you look at your order, and it doesn’t make sense to you, you probably need to think about the flow of your main points. Often, this process is an art and not a science. But let’s look at a couple of examples.

When you look at these two examples, what are your immediate impressions of the two examples? In the first example, does it make sense to talk about history, and then the problems, and finally how to eliminate school dress codes? Would it make sense to put history as your last main point? Probably not. In this case, the main points are in a logical sequential order. What about the second example? Does it make sense to talk about your solution, then your problem, and then define the solution? Not really! What order do you think these main points should be placed in for a logical flow? Maybe you should explain the problem (lack of rider laws), then define your solution (what is rider law legislation), and then argue for your solution (why states should have rider laws). Notice that in this example you don’t even need to know what “rider laws” are to see that the flow didn’t make sense.

Using Common Organizing Patterns

Twentyfour Students – Organization makes you flow – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Previously in this chapter, we discussed how to make your main points flow logically. This section is going to provide you with organization patterns to help you create a logically organized speech. The first organization pattern we’ll discuss is categorical/topical.

Categorical/Topical

By far the most common pattern for organizing a speech is by categories or topics. The categories function as a way to help the speaker organize the message in a consistent fashion. The goal of a categorical/topical speech pattern is to create categories (or chunks) of information that go together to help support your original specific purpose. Let’s look at an example:

In this case, we have a speaker trying to persuade a group of high school juniors to apply to attend Generic University. To persuade this group, the speaker has divided the information into three basic categories: what it’s like to live in the dorms, what classes are like, and what life is like on campus. Almost anyone could take this basic speech and specifically tailor the speech to fit their own university or college. The main points in this example could be rearranged and the organizational pattern would still be effective because there is no inherent logic to the sequence of points. Let’s look at a second example:

In this speech, the speaker is talking about how to find others online and date them. Specifically, the speaker starts by explaining what Internet dating is; then the speaker talks about how to make Internet dating better for her or his audience members; and finally, the speaker ends by discussing some negative aspects of Internet dating. Again, notice that the information is chunked into three categories or topics and that the second and third could be reversed and still provide a logical structure for your speech.

Comparison/Contrast

Another method for organizing your main points is the comparison/contrast speech pattern . While this pattern lends itself easily to two main points, you can also create a third point by giving basic information about what is being compared and what is being contrasted. Let’s look at two examples; the first one will be a two-point example and the second a three-point example:

If you were using the comparison/contrast pattern for persuasive purposes, in the preceding examples, you’d want to make sure that when you show how Drug X and Drug Y differ, you clearly state why Drug X is the better choice for physicians to adopt. In essence, you’d want to make sure that when you compare the two drugs, you show that Drug X has all the benefits of Drug Y, but when you contrast the two drugs, you show how Drug X is superior to Drug Y in some way.

The spatial speech pattern organizes information according to how things fit together in physical space. This pattern is best used when your main points are oriented to different locations that can exist independently. The primary reason to choose this format is to show that the main points have specific locations. We’ll look at two examples here, one involving physical geography and one involving a different spatial order.

If you look at a basic map of the United States, you’ll notice that these groupings of states were created because of their geographic location to one another. In essence, the states create three spatial territories to explain.

Now let’s look at a spatial speech unrelated to geography.

In this example, we still have three spatial areas. If you look at a model of the urinary system, the first step is the kidney, which then takes waste through the ureters to the bladder, which then relies on the sphincter muscle to excrete waste through the urethra. All we’ve done in this example is create a spatial speech order for discussing how waste is removed from the human body through the urinary system. It is spatial because the organization pattern is determined by the physical location of each body part in relation to the others discussed.

Chronological

The chronological speech pattern places the main idea in the time order in which items appear—whether backward or forward. Here’s a simple example.

In this example, we’re looking at the writings of Winston Churchill in relation to World War II (before, during, and after). By placing his writings into these three categories, we develop a system for understanding this material based on Churchill’s own life. Note that you could also use reverse chronological order and start with Churchill’s writings after World War II, progressing backward to his earliest writings.

Cause/Effect

The causal speech pattern is used to explain cause-and-effect relationships. When you use a causal speech pattern, your speech will have two basic main points: cause and effect. In the first main point, typically you will talk about the causes of a phenomenon, and in the second main point, you will then show how the causes lead to either a specific effect or a small set of effects. Let’s look at an example.

In this case, the first main point is about the history and prevalence of drinking alcohol among Native Americans (the cause). The second point then examines the effects of Native American alcohol consumption and how it differs from other population groups.

However, a causal organizational pattern can also begin with an effect and then explore one or more causes. In the following example, the effect is the number of arrests for domestic violence.

In this example, the possible causes for the difference might include stricter law enforcement, greater likelihood of neighbors reporting an incident, and police training that emphasizes arrests as opposed to other outcomes. Examining these possible causes may suggest that despite the arrest statistic, the actual number of domestic violence incidents in your city may not be greater than in other cities of similar size.

Problem-Cause-Solution

Another format for organizing distinct main points in a clear manner is the problem-cause-solution speech pattern . In this format, you describe a problem, identify what you believe is causing the problem, and then recommend a solution to correct the problem.