Join Pilot Waitlist

Home » Blog » General » Enhancing Verbal Expression: A Guide to Speech and Language Therapy Worksheets

Enhancing Verbal Expression: A Guide to Speech and Language Therapy Worksheets

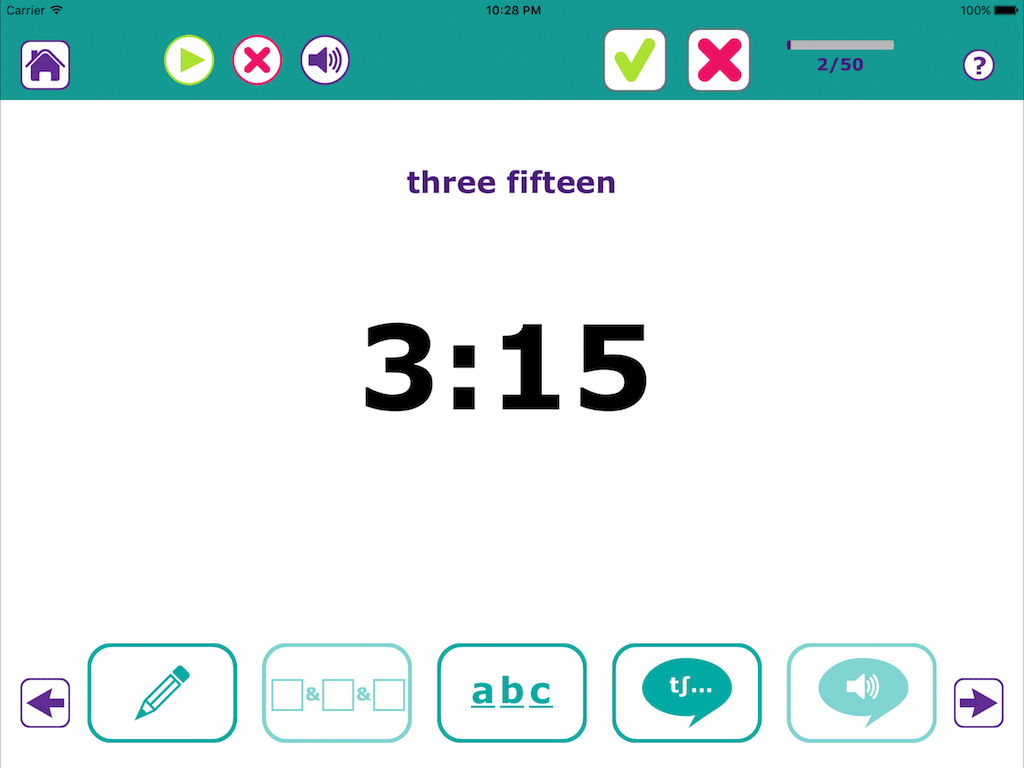

Welcome to my blog! In today’s post, we will explore the world of speech and language therapy worksheets and how they can enhance verbal expression. Verbal expression plays a crucial role in social emotional development, and these worksheets are valuable tools in helping individuals improve their communication skills. So, let’s dive in and discover the benefits of using speech and language therapy worksheets!

Understanding Verbal Expression

Verbal expression refers to the ability to convey thoughts, ideas, and emotions through spoken words. It involves various components, such as vocabulary, grammar, articulation, and social interaction. However, many individuals face challenges in verbal expression, which can impact their overall communication skills and social interactions.

Common challenges in verbal expression include difficulties with articulation, limited vocabulary, poor grammar and syntax, and struggles in engaging in meaningful conversations. These challenges can hinder individuals from effectively expressing themselves and connecting with others.

Benefits of Speech and Language Therapy Worksheets

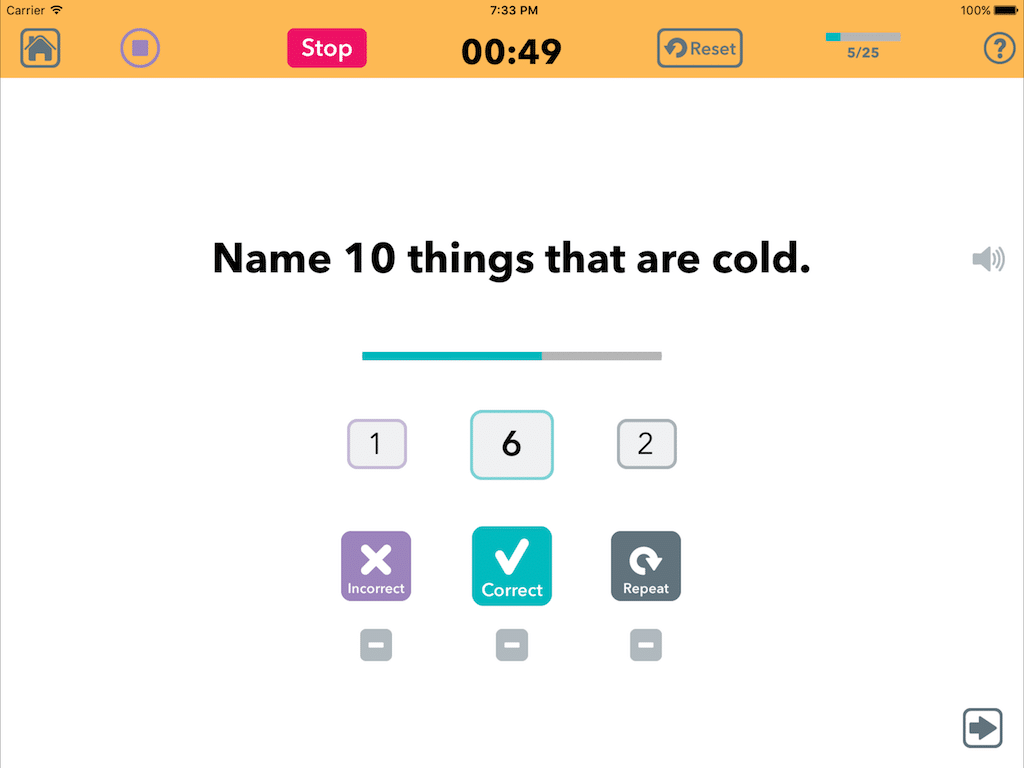

Speech and language therapy worksheets offer numerous benefits in promoting language development, enhancing communication skills, and improving social interaction. These worksheets provide structured exercises and activities that target specific areas of verbal expression, making the learning process more engaging and effective.

By using speech and language therapy worksheets, individuals can:

Promote Language Development

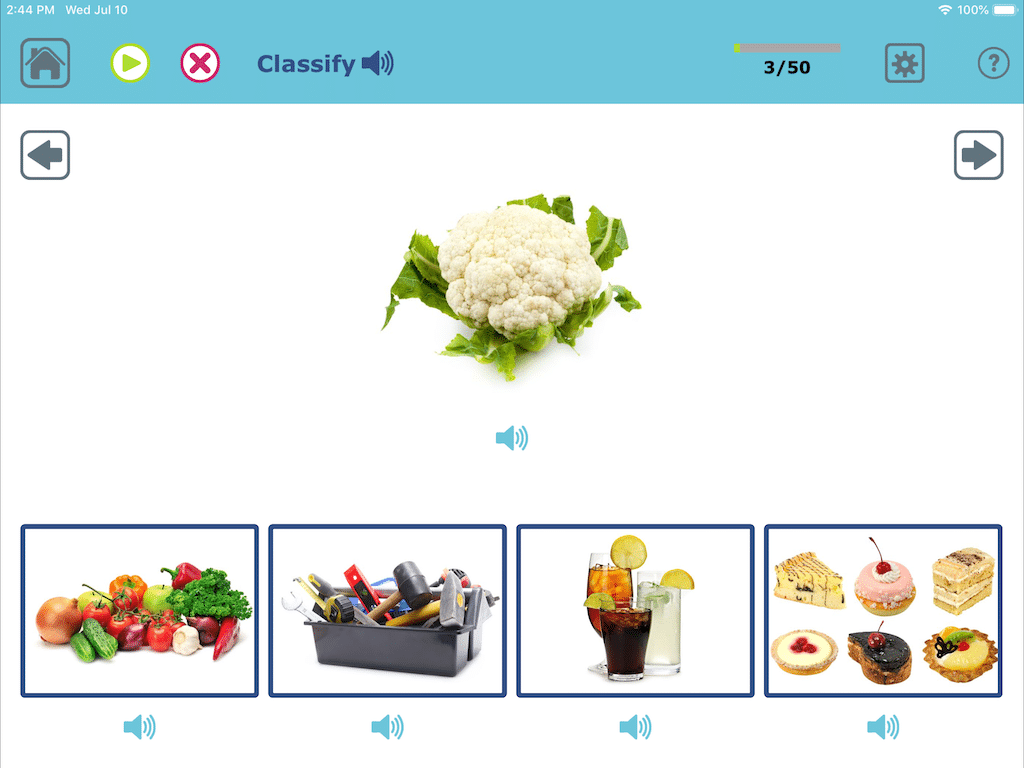

Language development is crucial for effective verbal expression. Speech and language therapy worksheets provide opportunities for individuals to expand their vocabulary, learn new words, and improve their understanding of language concepts. These worksheets often include exercises that focus on word associations, categorization, and semantic relationships, helping individuals develop a strong foundation in language skills.

Enhance Communication Skills

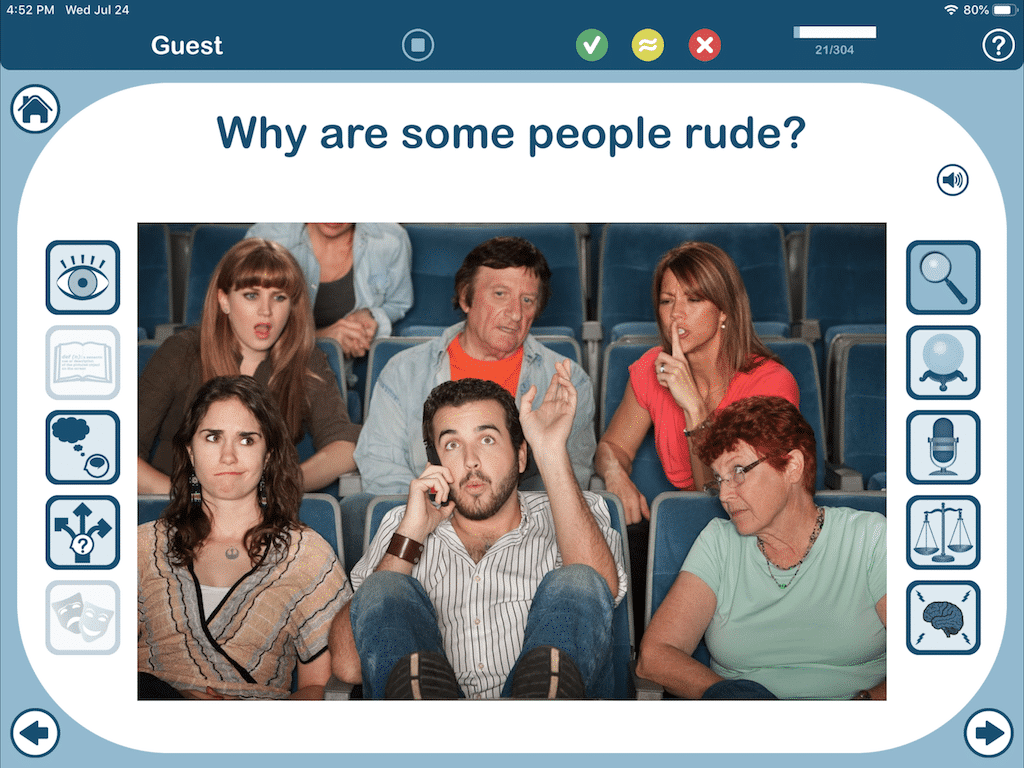

Effective communication involves more than just using words. It requires individuals to understand non-verbal cues, interpret social contexts, and engage in meaningful conversations. Speech and language therapy worksheets incorporate activities that target these skills, such as role-playing scenarios, practicing turn-taking, and understanding emotions. By engaging in these activities, individuals can enhance their communication skills and become more confident in expressing themselves.

Improve Social Interaction

Verbal expression is closely tied to social interaction. Individuals who struggle with verbal expression may find it challenging to connect with others and build meaningful relationships. Speech and language therapy worksheets include exercises that focus on social skills, such as initiating conversations, maintaining eye contact, and understanding social cues. These activities help individuals improve their social interaction skills, leading to more successful and fulfilling relationships.

Types of Speech and Language Therapy Worksheets

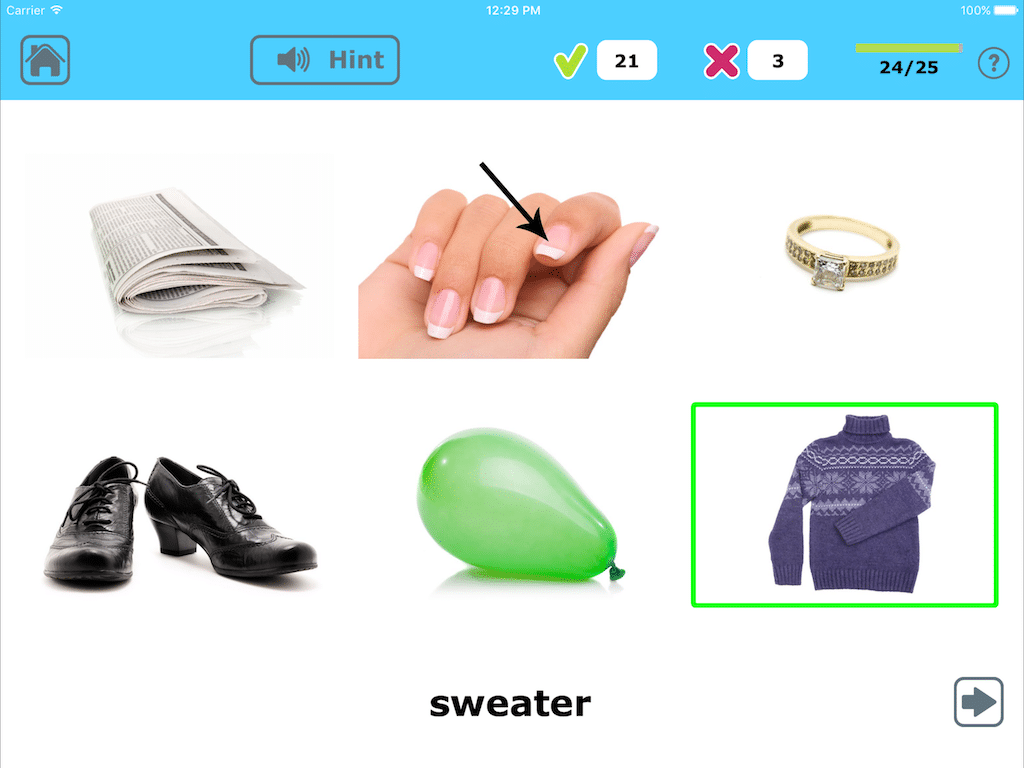

Speech and language therapy worksheets come in various types, each targeting specific areas of verbal expression. Here are some common types of worksheets:

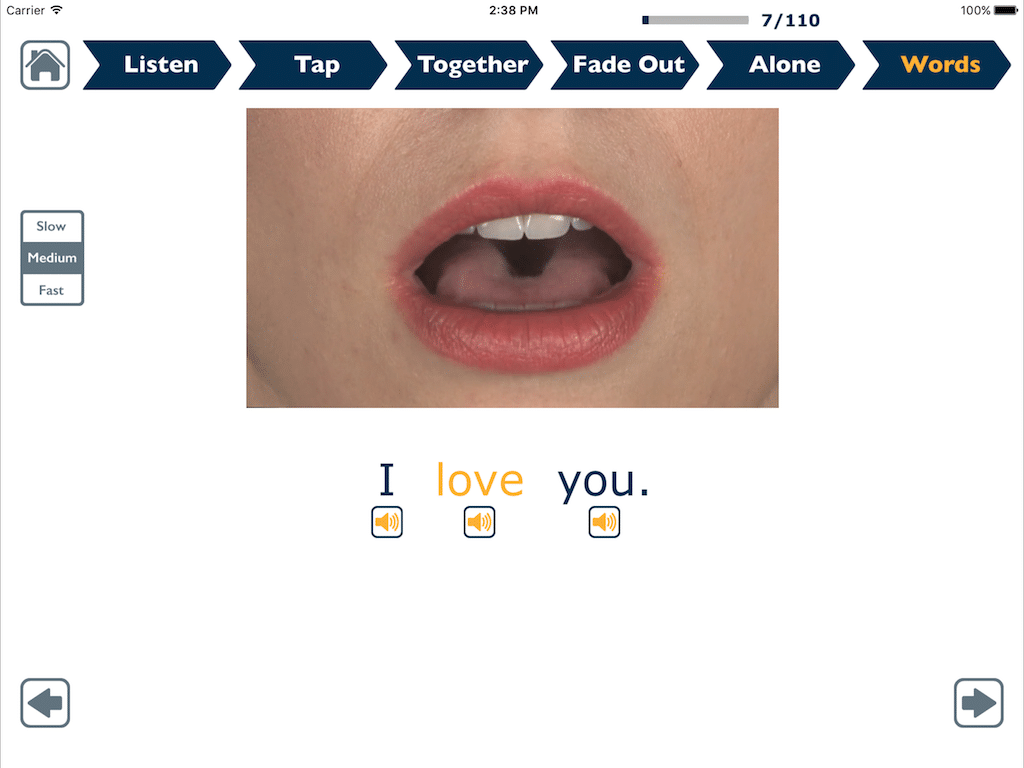

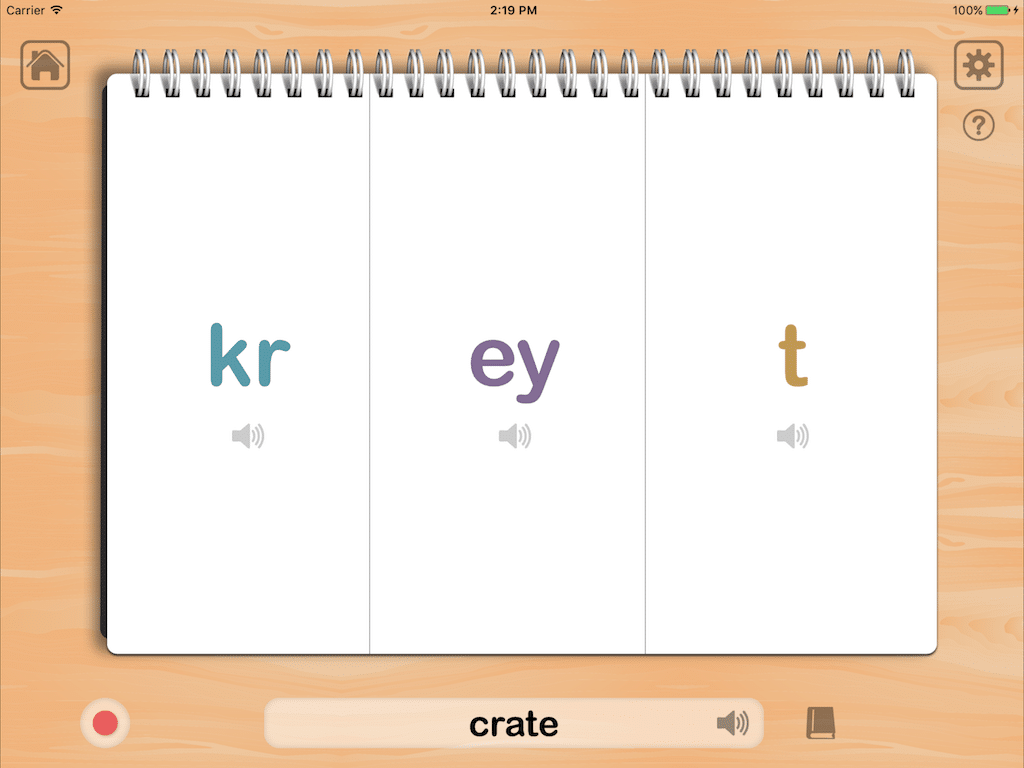

Articulation Worksheets

Articulation worksheets focus on improving speech sound production. They include exercises that help individuals practice specific sounds and correct any articulation errors. These worksheets often include visual cues and prompts to assist individuals in producing sounds accurately.

Vocabulary-Building Worksheets

Vocabulary-building worksheets aim to expand an individual’s vocabulary. They include activities that introduce new words, reinforce word meanings, and encourage word usage in different contexts. These worksheets may involve matching words with their definitions, completing sentences with appropriate words, or categorizing words based on their meanings.

Grammar and Syntax Worksheets

Grammar and syntax worksheets focus on improving sentence structure and grammar skills. They include exercises that target various grammar rules, such as subject-verb agreement, verb tenses, and sentence formation. These worksheets often involve filling in the blanks, rearranging words to form grammatically correct sentences, and identifying errors in sentence structure.

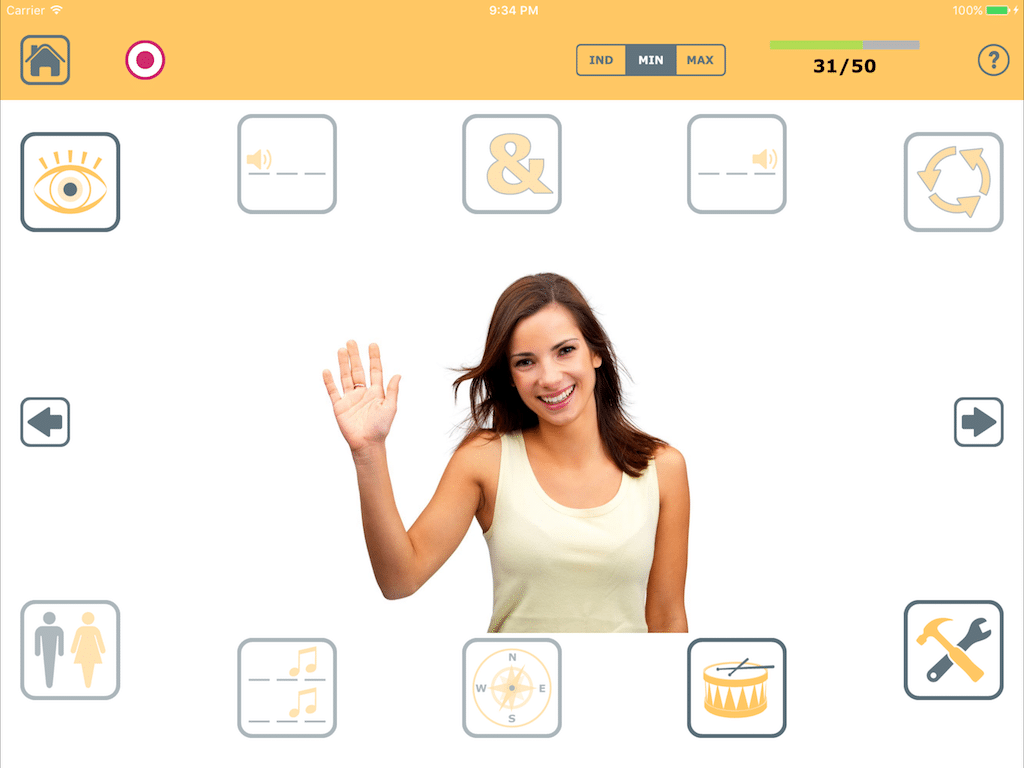

Conversation and Social Skills Worksheets

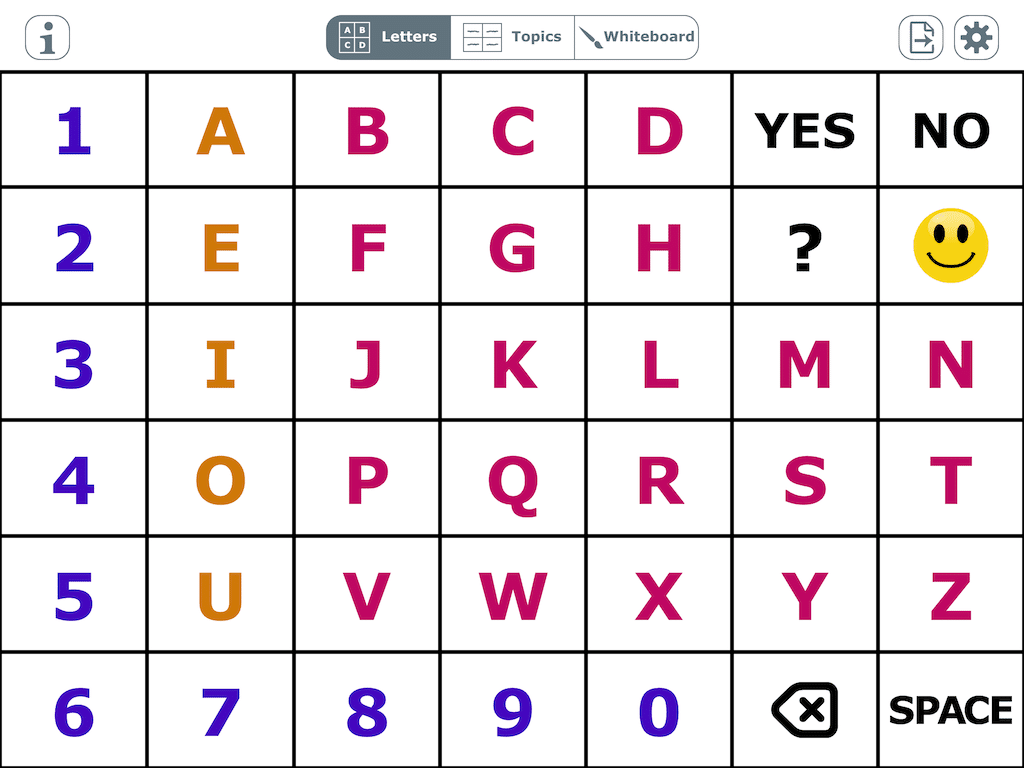

Conversation and social skills worksheets aim to improve individuals’ ability to engage in meaningful conversations and understand social cues. These worksheets include activities that focus on turn-taking, topic initiation, active listening, and understanding non-verbal cues. They may involve role-playing scenarios, practicing social greetings, or identifying emotions based on facial expressions.

How to Use Speech and Language Therapy Worksheets

Using speech and language therapy worksheets effectively involves setting goals and objectives, incorporating the worksheets into therapy sessions, and monitoring progress to adjust strategies accordingly.

Setting Goals and Objectives

Before using speech and language therapy worksheets, it is essential to identify the specific areas of verbal expression that need improvement. Set clear goals and objectives that are measurable and achievable. For example, a goal could be to improve articulation by correctly producing specific sounds or to expand vocabulary by learning a certain number of new words.

Incorporating Worksheets into Therapy Sessions

Integrate speech and language therapy worksheets into therapy sessions to provide structured practice and reinforcement. Start with activities that match the individual’s current skill level and gradually increase the difficulty level as they progress. Use the worksheets as a guide to target specific skills and provide feedback and guidance during the sessions.

Monitoring Progress and Adjusting Strategies

Regularly monitor the individual’s progress by tracking their performance on the worksheets. Assess whether they are meeting the set goals and objectives and make adjustments to the strategies if needed. If certain areas are not improving as expected, consider modifying the approach or seeking guidance from a speech language pathologist.

Additional Strategies to Enhance Verbal Expression

While speech and language therapy worksheets are valuable tools, there are additional strategies that can further enhance verbal expression:

Encouraging Storytelling and Narrative Skills

Storytelling and narrative skills play a significant role in verbal expression. Encourage individuals to share their stories, whether real or imaginary, and guide them in organizing their thoughts and structuring their narratives. This practice helps improve their ability to express ideas coherently and engage listeners.

Engaging in Role-Play and Pretend Play Activities

Role-play and pretend play activities provide opportunities for individuals to practice different social scenarios and develop their communication skills. Encourage them to take on different roles, express themselves in various contexts, and engage in interactive play with others. These activities help individuals become more comfortable in expressing themselves and understanding social dynamics.

Using Visual Aids and Prompts

Visual aids and prompts can support individuals in verbal expression by providing visual cues and reminders. Use pictures, charts, or diagrams to help individuals understand and remember vocabulary words, grammar rules, or conversation strategies. Visual aids can enhance comprehension and facilitate the transfer of knowledge into practical communication skills.

Resources for Speech and Language Therapy Worksheets

There are various resources available for speech and language therapy worksheets:

Online Platforms and Websites

Explore online platforms and websites that offer a wide range of speech and language therapy worksheets. EverydaySpeech is an excellent resource that provides a comprehensive library of worksheets targeting different areas of verbal expression. They offer a free trial to get started, so you can experience the benefits firsthand.

Books and Publications

Books and publications by speech language pathologists are valuable resources for finding speech and language therapy worksheets. Look for books that focus on specific areas of verbal expression and offer practical exercises and activities. These resources can provide additional guidance and support in enhancing communication skills.

Collaborating with Speech Language Pathologists

Collaborating with speech language pathologists can be highly beneficial in accessing specialized speech and language therapy worksheets. They can provide personalized recommendations and create customized worksheets based on individual needs. Working with a speech language pathologist ensures that the worksheets align with specific goals and objectives.

Verbal expression plays a crucial role in social emotional development, and speech and language therapy worksheets are powerful tools in enhancing communication skills. By using these worksheets, individuals can promote language development, improve communication skills, and enhance social interaction. Additionally, incorporating additional strategies such as storytelling, role-play, and visual aids can further enhance verbal expression. Explore the resources available, including EverydaySpeech’s free trial, to embark on a journey towards enhanced communication skills and meaningful connections.

Start your EverydaySpeech Free trial here !

Related Blog Posts:

Pragmatic language: enhancing social skills for meaningful interactions.

Pragmatic Language: Enhancing Social Skills for Meaningful Interactions Pragmatic Language: Enhancing Social Skills for Meaningful Interactions Introduction: Social skills play a crucial role in our daily interactions. They enable us to navigate social situations,...

Preparing for Success: Enhancing Social Communication in Grade 12

Preparing for Success: Enhancing Social Communication in Grade 12 Key Takeaways Strong social communication skills are crucial for academic success and building meaningful relationships in Grade 12. Social communication includes verbal and non-verbal communication,...

Preparing for Success: Enhancing Social Communication in Grade 12 Preparing for Success: Enhancing Social Communication in Grade 12 As students enter Grade 12, they are on the cusp of adulthood and preparing for the next chapter of their lives. While academic success...

FREE MATERIALS

Better doesn’t have to be harder, social skills lessons students actually enjoy.

Be the best educator you can be with no extra prep time needed. Sign up to get access to free samples from the best Social Skills and Social-Emotional educational platform.

Get Started Instantly for Free

Complete guided therapy.

The subscription associated with this email has been cancelled and is no longer active. To reactivate your subscription, please log in.

If you would like to make changes to your account, please log in using the button below and navigate to the settings page. If you’ve forgotten your password, you can reset it using the button below.

Unfortunately it looks like we’re not able to create your subscription at this time. Please contact support to have the issue resolved. We apologize for the inconvenience. Error: Web signup - customer email already exists

Welcome back! The subscription associated with this email was previously cancelled, but don’t fret! We make it easy to reactivate your subscription and pick up right where you left off. Note that subscription reactivations aren't eligible for free trials, but your purchase is protected by a 30 day money back guarantee. Let us know anytime within 30 days if you aren’t satisfied and we'll send you a full refund, no questions asked. Please press ‘Continue’ to enter your payment details and reactivate your subscription

Notice About Our SEL Curriculum

Our SEL Curriculum is currently in a soft product launch stage and is only available by Site License. A Site License is currently defined as a school-building minimum or a minimum cost of $3,000 for the first year of use. Individual SEL Curriculum licenses are not currently available based on the current version of this product.

By clicking continue below, you understand that access to our SEL curriculum is currently limited to the terms above.

Verbal Communication: Understanding the Power of Words

Categories Social Psychology

As human beings, we rely on communication to express our thoughts, feelings, and intentions. Verbal communication, in particular, involves using words to convey a message to another person. It is a fundamental aspect of human interaction and is crucial in our daily lives and relationships.

In this article, we will explore the importance of verbal communication, the different types of verbal communication, and some tips on improving your verbal communication skills.

Table of Contents

Importance of Verbal Communication

Verbal communication is essential because it is the primary means of interacting with others. It lets us express our thoughts and feelings, convey information, and build relationships. It is a powerful tool for connecting with others and forming social bonds.

By communicating meaning verbally, others are able to understand your needs, interests, and beliefs.

Effective verbal communication is essential in many contexts, including personal relationships, social interactions, and professional settings. In personal relationships, it can help build trust, foster intimacy, and resolve conflicts. Lack of communication can lead to serious problems, including conflicts and the breakdown of relationships.

Social interactions can help establish common ground, build rapport, and create a sense of community. For example, discussions can help people with different needs understand one another and find ways to ensure each person achieves their goals.

In the workplace, it can help to convey ideas, influence others, and achieve goals.

Types of Verbal Communication

There are two main forms of verbal communication: spoken and written communication.

- Spoken Communication : Spoken communication is the most common form of verbal communication. It involves using words, tone of voice, and body language to convey a message. Spoken communication can take many different forms, including conversations, speeches, and presentations.

- Written Communication : Written communication is using written words to convey a message. It includes emails, letters, memos, and reports. Written communication is often used in professional settings to document information and convey messages to others.

There are four main types of verbal communication, each with its own unique characteristics and purposes:

- Intrapersonal communication : Intrapersonal communication is the process of talking to oneself, either out loud or internally. This type of communication is often used for self-reflection, problem-solving, and decision-making. Intrapersonal communication can help us better understand our own thoughts and feelings, and can be a valuable tool for personal growth and development.

- Interpersonal communication : Interpersonal communication is the process of communication between two or more people. This type of communication is often used for social interaction, relationship-building, and collaboration. Interpersonal communication can involve a range of verbal communication modes, such as face-to-face communication, telephone communication, and video conferencing.

- Small group communication : Small group communication involves communication between three to ten people, typically in a group setting such as a meeting or a discussion. This type of communication is often used for decision-making, problem-solving, and brainstorming. Small group communication requires effective listening and speaking skills, as well as the ability to work collaboratively with others.

- Public communication : Public communication is communicating to a large audience, typically through a speech or a presentation. This type of communication is often used for persuasive purposes, such as advocating for a cause or presenting information to an audience. Public communication requires effective public speaking skills, including the ability to engage and connect with the audience, use effective visual aids, and communicate ideas clearly and persuasively.

Other Types of Communication

In addition to verbal communication, other important forms of communication can convey meaning, including:

Nonverbal communication : Nonverbal communication is the use of body language, facial expressions, and tone of voice to convey a message. It can be used to emphasize a point, show emotion, or convey meaning. Nonverbal communication can be just as powerful as spoken communication and can often convey a message more effectively than words alone.

Visual communication : Visual communication is the use of images, charts, and graphs to convey a message. It is often used in professional settings to present data and information in a way that is easy to understand.

Components of Verbal Communication

Verbal communication is a complex process that involves not only the words we use, but also how we say them. Tone of voice, inflection, and other vocal cues can greatly impact the meaning of our message. Here are some important aspects of verbal communication and how they convey meaning:

- Tone of voice : Tone of voice refers to the way we use our voice to convey meaning. It can be described as the emotional quality of our voice. For example, a sarcastic tone of voice can convey that the speaker is not being sincere, while a warm and friendly tone can convey that the speaker is approachable and trustworthy.

- Inflection : Inflection refers to the rise and fall of our voice as we speak. It can convey emphasis and emotion. For example, a rising inflection at the end of a sentence can indicate a question, while a falling inflection can indicate a statement.

- Volume : Volume refers to how loudly or softly we speak. It can convey confidence, authority, and assertiveness. For example, speaking loudly can convey confidence and authority, while speaking softly can convey intimacy and vulnerability.

- Pace : Pace refers to the speed at which we speak. It can convey excitement, urgency, and impatience. For example, speaking quickly can convey excitement and urgency, while speaking slowly can convey thoughtfulness and deliberation.

- Intensity : Intensity refers to the level of emotional energy that we put into our words. It can convey passion, enthusiasm, and conviction. For example, speaking with intensity can convey a strong belief in something, while speaking with low intensity can convey ambivalence or lack of interest.

- Pitch : Pitch refers to the highness or lowness of our voice. It can convey age, gender, and emotion. For example, a high-pitched voice can convey youthfulness or excitement, while a low-pitched voice can convey authority or seriousness.

It’s important to note that these aspects of verbal communication can vary greatly depending on context, culture, and personal preference. What may be considered a confident tone of voice in one culture may be perceived as aggressive in another.

Understanding these nuances is essential for effective verbal communication. By paying attention to these aspects of verbal communication, we can convey our message more effectively and avoid misunderstandings.

Modes of Verbal Communication

Verbal communication can occur through different modes, each with their own unique features and advantages. Here are some of the different ways verbal communication may occur:

Face-to-Face Verbal Communication

Face-to-face communication occurs when two or more people are in the same physical space and communicate verbally. This mode of communication allows for the use of nonverbal cues, such as facial expressions and body language, which can help convey meaning and emotion. It also allows for immediate feedback and clarification of misunderstandings.

Telephone Communication

Telephone communication occurs when two or more people communicate verbally over a telephone line. This mode of communication allows for immediate verbal communication over long distances but does not allow for the use of nonverbal cues, which can sometimes make it difficult to convey meaning and emotion.

Video Conferencing

Video conferencing occurs when two or more people communicate verbally over a video conferencing platform, such as Zoom or Skype. This mode of communication combines the benefits of face-to-face and telephone communication, allowing for the use of nonverbal cues and immediate verbal communication over long distances.

Public Speaking

Public speaking occurs when one person communicates verbally to a large audience. This mode of communication requires careful planning and preparation, as well as the ability to engage and connect with the audience through the use of tone of voice, inflection, and other vocal cues.

Group Discussion

Group discussion occurs when a group of people communicate verbally to exchange ideas, solve problems, or make decisions. This mode of communication requires active listening skills and the ability to work collaboratively with others to achieve a common goal.

Written Communication

Written communication occurs when ideas, thoughts, and information are conveyed through written words, such as emails, letters, or memos. This mode of communication allows for careful consideration and editing of the message, but can sometimes lack the immediacy and personal connection of verbal communication.

It’s important to note that each mode of verbal communication has its own strengths and weaknesses. Some modes may be more appropriate for certain contexts than others.

For example, face-to-face communication may be more effective for resolving conflicts, while written communication may be more appropriate for conveying complex information or instructions.

Tips for Improving Verbal Communication Skills

Effective verbal communication requires more than just speaking clearly and articulately. It involves listening actively, empathizing with others, and adapting your communication style to different situations. Here are some tips for improving your verbal communication skills:

- Listen actively : Effective communication requires active listening. This means paying attention to what the other person is saying, asking questions, and clarifying misunderstandings.

- Use appropriate body language : Your body language can convey as much meaning as your words. Use appropriate gestures and facial expressions to emphasize your message and convey your emotions.

- Speak clearly and confidently : Speak clearly and confidently to ensure that your message is understood.

- Empathize with others : Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of others. It is an important communication skill because it helps build trust and understanding.

- Be adaptable : Adapt your communication style to different situations and audiences. Use appropriate language for the context and audience, and be mindful of cultural differences.

- INTERPERSONAL SKILLS

- Communication Skills

- Verbal Communication

Search SkillsYouNeed:

The SkillsYouNeed Guide to Interpersonal Skills

Interpersonal Skills:

- A - Z List of Interpersonal Skills

- Interpersonal Skills Self-Assessment

- What is Communication?

- Interpersonal Communication Skills

- Tips for Effective Interpersonal Communication

- Principles of Communication

- Barriers to Effective Communication

- Avoiding Common Communication Mistakes

- Social Skills

- Getting Social Online

- Giving and Receiving Feedback

- Improving Communication

- Interview Skills

- Telephone Interviews

- Interviewing Skills

- Business Language Skills

- The Ladder of Inference

- Listening Skills

- Top Tips for Effective Listening

- The 10 Principles of Listening

- Effective Listening Skills

- Barriers to Effective Listening

- Types of Listening

- Active Listening

- Mindful Listening

- Empathic Listening

- Listening Misconceptions

- Non-Verbal Communication

- Personal Appearance

- Body Language

- Non-Verbal Communication: Face and Voice

- Effective Speaking

- Conversational Skills

- How to Keep a Conversation Flowing

- Conversation Tips for Getting What You Want

- Giving a Speech

- Questioning Skills and Techniques

- Types of Question

- Clarification

- Emotional Intelligence

- Conflict Resolution and Mediation Skills

- Customer Service Skills

- Team-Working, Groups and Meetings

- Decision-Making and Problem-Solving

- Negotiation and Persuasion Skills

- Personal and Romantic Relationship Skills

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Verbal Communication Skills

Verbal communication is the use of words to share information with other people. It can therefore include both spoken and written communication. However, many people use the term to describe only spoken communication. The verbal element of communication is all about the words that you choose, and how they are heard and interpreted.

This page focuses on spoken communication. However, the choice of words can be equally—if not more—important in written communication, where there is little or no non-verbal communication to help with the interpretation of the message.

What is Verbal Communication?

Verbal communication is any communication that uses words to share information with others. These words may be both spoken and written.

Communication is a two-way process

Communication is about passing information from one person to another.

This means that both the sending and the receiving of the message are equally important.

Verbal communication therefore requires both a speaker (or writer) to transmit the message, and a listener (or reader) to make sense of the message. This page discusses both parts of the process.

There are a large number of different verbal communication skills. They range from the obvious (being able to speak clearly, or listening, for example), to the more subtle (such as reflecting and clarifying). This page provides a summary of these skills, and shows where you can find out more.

It is important to remember that effective verbal communication cannot be fully isolated from non-verbal communication : your body language, tone of voice, and facial expressions, for example.

Clarity of speech, remaining calm and focused, being polite and following some basic rules of etiquette will all aid the process of verbal communication.

Opening Communication

In many interpersonal encounters, the first few minutes are extremely important. First impressions have a significant impact on the success of further and future communication.

When you first meet someone, you form an instant impression of them, based on how they look, sound and behave, as well as anything you may have heard about them from other people.

This first impression guides your future communications, at least to some extent.

For example, when you meet someone and hear them speak, you form a judgement about their background, and likely level of ability and understanding. This might well change what you say. If you hear a foreign accent, for example, you might decide that you need to use simpler language. You might also realise that you will need to listen more carefully to ensure that you understand what they are saying to you.

Of course your first impression may be revised later. You should ensure that you consciously ‘update’ your thinking when you receive new information about your contact and as you get to know them better.

Basic Verbal Communication Skills: Effective Speaking and Listening

Effective speaking involves three main areas: the words you choose, how you say them, and how you reinforce them with other non-verbal communication.

All these affect the transmission of your message, and how it is received and understood by your audience.

It is worth considering your choice of words carefully. You will probably need to use different words in different situations, even when discussing the same subject. For example, what you say to a close colleague will be very different from how you present a subject at a major conference.

How you speak includes your tone of voice and pace. Like non-verbal communication more generally, these send important messages to your audience, for example, about your level of interest and commitment, or whether you are nervous about their reaction.

There is more about this in our page on Non-Verbal Communication: Face and Voice .

Active listening is an important skill. However, when we communicate, we tend to spend far more energy considering what we are going to say than listening to the other person.

Effective listening is vital for good verbal communication. There are a number of ways that you can ensure that you listen more effectively. These include:

Be prepared to listen . Concentrate on the speaker, and not on how you are going to reply.

Keep an open mind and avoid making judgements about the speaker.

Concentrate on the main direction of the speaker’s message . Try to understand broadly what they are trying to say overall, as well as the detail of the words that they are using.

Avoid distractions if at all possible. For example, if there is a lot of background noise, you might suggest that you go somewhere else to talk.

Be objective .

Do not be trying to think of your next question while the other person is giving information.

Do not dwell on one or two points at the expense of others . Try to use the overall picture and all the information that you have.

Do not stereotype the speaker . Try not to let prejudices associated with, for example, gender, ethnicity, accent, social class, appearance or dress interfere with what is being said (see Personal Appearance ).

There is more information in our pages on Listening Skills .

Improving Verbal Communication: More Advanced Techniques

There are a number of tools and techniques that you can use to improve the effectiveness of your verbal communication. These include reinforcement, reflection, clarification, and questioning.

Reinforcement

Reinforcement is the use of encouraging words alongside non-verbal gestures such as head nods, a warm facial expression and maintaining eye contact.

All these help to build rapport and are more likely to reinforce openness in others. The use of encouragement and positive reinforcement can:

- Encourage others to participate in discussion (particularly in group work);

- Show interest in what other people have to say;

- Pave the way for development and/or maintenance of a relationship;

- Allay fears and give reassurance;

- Show warmth and openness; and

- Reduce shyness or nervousness in ourselves and others.

Questioning

Questioning is broadly how we obtain information from others on specific topics.

Questioning is an essential way of clarifying areas that are unclear or test your understanding. It can also enable you to explicitly seek support from others.

On a more social level, questioning is also a useful technique to start conversations, draw someone into a conversation, or simply show interest. Effective questioning is therefore an essential element of verbal communication.

We use two main types of question:

Closed Questions

Closed questions tend to seek only a one or two word answer (often simply ‘yes’ or ‘no’). They therefore limit the scope of the response. Two examples of closed questions are:

“Did you travel by car today?” and “Did you see the football game yesterday?”

These types of question allow the questioner to remain in control of the communication. This is often not the desired outcome when trying to encourage verbal communication, so many people try to focus on using open questions more often. Nevertheless, closed questions can be useful for focusing discussion and obtaining clear, concise answers when needed.

Open Questions

Open questions demand further discussion and elaboration. They therefore broaden the scope for response. They include, for example,

“What was the traffic like this morning?” “What do you feel you would like to gain from this discussion?”

Open questions will take longer to answer, but they give the other person far more scope for self-expression and encourage involvement in the conversation.

For more on questioning see our pages: Questioning and Types of Question .

Reflecting and Clarifying

Reflecting is the process of feeding back to another person your understanding of what has been said.

Reflecting is a specialised skill often used within counselling, but it can also be applied to a wide range of communication contexts and is a useful skill to learn.

Reflecting often involves paraphrasing the message communicated to you by the speaker in your own words. You need to try to capture the essence of the facts and feelings expressed, and communicate your understanding back to the speaker. It is a useful skill because:

- You can check that you have understood the message clearly.

- The speaker gets feedback about how the message has been received and can then clarify or expand if they wish.

- It shows interest in, and respect for, what the other person has to say.

- You are demonstrating that you are considering the other person’s viewpoint.

See also our pages on Reflecting and Clarifying .

Summarising

A summary is an overview of the main points or issues raised.

Summarising can also serve the same purpose as ‘reflecting’. However, summarising allows both parties to review and agree the message, and ensure that communication has been effective. When used effectively, summaries may also serve as a guide to the next steps forward.

Closing Communication

The way a communication is closed or ended will, at least in part, determine the way a conversation is remembered.

People use both verbal and non-verbal signals to end a conversation.

Verbal signals may include phrases such as: “Well, I must be going,” and “Thank you so much, that’s really helpful.”

Non-verbal conclusions may include starting to avoid eye contact, standing up, turning away, or behaviours such as looking at a watch or closing notepads or books. These non-verbal actions indicate to the other person that the initiator wishes to end the communication.

People often use a mixture of these, but tend to start with the non-verbal signals, especially face-to-face. On the telephone, of course, verbal cues are essential.

Closing an interaction too abruptly may not allow the other person to 'round off' what he or she is saying so you should ensure there is time for winding-up. The closure of an interaction is a good time to make any future arrangements. Last, but not least, this time will no doubt be accompanied by a number of socially acceptable parting gestures.

Further Reading from Skills You Need

Our Communication Skills eBooks

Learn more about the key communication skills you need to be a more effective communicator.

Our eBooks are ideal for anyone who wants to learn about or develop their interpersonal skills and are full of easy-to-follow, practical information.

Only part of the picture

It is vital to remember that any communication is made up of the sum of its parts.

Verbal communication is an important element, but only part of the overall message conveyed. Some research suggests that the verbal element is, in fact, a very small part of the overall message: just 20 to 30%. This is still, however, significant, and it is worth spending time to improve your verbal communication skills.

Continue to: Effective Speaking Conversational Skills How good are your interpersonal skills? Interpersonal Skills Self-Assessment

See also: Ladder of Inference How to be Polite Personal Development

Improve your practice.

Enhance your soft skills with a range of award-winning courses.

Speech transitions: words and phrases to connect your ideas

June 28, 2018 - Gini Beqiri

When delivering presentations it’s important for your words and ideas to flow so your audience can understand how everything links together and why it’s all relevant.

This can be done using speech transitions because these act as signposts to the audience – signalling the relationship between points and ideas. This article explores how to use speech transitions in presentations.

What are speech transitions?

Speech transitions are words and phrases that allow you to smoothly move from one point to another so that your speech flows and your presentation is unified.

This makes it easier for the audience to understand your argument and without transitions the audience may be confused as to how one point relates to another and they may think you’re randomly jumping between points.

Types of transitions

Transitions can be one word, a phrase or a full sentence – there are many different types, here are a few:

Introduction

Introduce your topic:

- We will be looking at/identifying/investigating the effects of…

- Today I will be discussing…

Presentation outline

Inform the audience of the structure of your presentation:

- There are three key points I’ll be discussing…

- I want to begin by…, and then I’ll move on to…

- We’ll be covering… from two points of view…

- This presentation is divided into four parts…

Move from the introduction to the first point

Signify to the audience that you will now begin discussing the first main point:

- Now that you’re aware of the overview, let’s begin with…

- First, let’s begin with…

- I will first cover…

- My first point covers…

- To get started, let’s look at…

Shift between similar points

Move from one point to a similar one:

- In the same way…

- Likewise…

- Equally…

- This is similar to…

- Similarly…

Shift between disagreeing points

You may have to introduce conflicting ideas – bridging words and phrases are especially good for this:

- Conversely…

- Despite this…

- However…

- On the contrary…

- Now let’s consider…

- Even so…

- Nonetheless…

- We can’t ignore…

- On the other hand…

Transition to a significant issue

- Fundamentally…

- A major issue is…

- The crux of the matter…

- A significant concern is…

Referring to previous points

You may have to refer to something that you’ve already spoken about because, for example, there may have been a break or a fire alarm etc:

- Let’s return to…

- We briefly spoke about X earlier; let’s look at it in more depth now…

- Let’s revisit…

- Let’s go back to…

- Do you recall when I mentioned…

This can be also be useful to introduce a new point because adults learn better when new information builds on previously learned information.

Introducing an aside note

You may want to introduce a digression:

- I’d just like to mention…

- That reminds me…

- Incidentally…

Physical movement

You can move your body and your standing location when you transition to another point. The audience find it easier to follow your presentation and movement will increase their interest.

A common technique for incorporating movement into your presentation is to:

- Start your introduction by standing in the centre of the stage.

- For your first point you stand on the left side of the stage.

- You discuss your second point from the centre again.

- You stand on the right side of the stage for your third point.

- The conclusion occurs in the centre.

Emphasising importance

You need to ensure that the audience get the message by informing them why something is important:

- More importantly…

- This is essential…

- Primarily…

- Mainly…

Internal summaries

Internal summarising consists of summarising before moving on to the next point. You must inform the audience:

- What part of the presentation you covered – “In the first part of this speech we’ve covered…”

- What the key points were – “Precisely how…”

- How this links in with the overall presentation – “So that’s the context…”

- What you’re moving on to – “Now I’d like to move on to the second part of presentation which looks at…”

Cause and effect

You will have to transition to show relationships between factors:

- Therefore…

- Thus…

- Consequently…

- As a result…

- This is significant because…

- Hence…

Elaboration

- Also…

- Besides…

- What’s more…

- In addition/additionally…

- Moreover…

- Furthermore…

Point-by-point or steps of a process

- First/firstly/The first one is…

- Second/Secondly/The second one is…

- Third/Thirdly/The third one is…

- Last/Lastly/Finally/The fourth one is…

Introduce an example

- This is demonstrated by…

- For instance…

- Take the case of…

- For example…

- You may be asking whether this happens in X? The answer is yes…

- To show/illustrate/highlight this…

- Let me illustrate this by…

Transition to a demonstration

- Now that we’ve covered the theory, let’s practically apply it…

- I’ll conduct an experiment to show you this in action…

- Let me demonstrate this…

- I’ll now show you this…

Introducing a quotation

- X was a supporter of this thinking because he said…

- There is a lot of support for this, for example, X said…

Transition to another speaker

In a group presentation you must transition to other speakers:

- Briefly recap on what you covered in your section: “So that was a brief introduction on what health anxiety is and how it can affect somebody”

- Introduce the next speaker in the team and explain what they will discuss: “Now Gayle will talk about the prevalence of health anxiety.”

- Then end by looking at the next speaker, gesturing towards them and saying their name: “Gayle”.

- The next speaker should acknowledge this with a quick: “Thank you Simon.”

From these examples, you can see how the different sections of the presentations link which makes it easier for the audience to follow and remain engaged.

You can tell personal stories or share the experiences of others to introduce a point. Anecdotes are especially valuable for your introduction and between different sections of the presentation because they engage the audience. Ensure that you plan the stories thoroughly beforehand and that they are not too long.

Using questions

You can transition through your speech by asking questions and these questions also have the benefit of engaging your audience more. There are three different types of questions:

Direct questions require an answer: “What is the capital of Italy?” These are mentally stimulating for the audience.

Rhetorical questions do not require answers, they are often used to emphasises an idea or point: “Is the Pope catholic?

Loaded questions contain an unjustified assumption made to prompt the audience into providing a particular answer which you can then correct to support your point: You may ask “Why does your wonderful company have such a low incidence of mental health problems?”.

The audience will generally answer that they’re happy. After receiving the answers you could then say “Actually it’s because people are still unwilling and too embarrassed to seek help for mental health issues at work etc.”

Transition to a visual aid

If you are going to introduce a visual aid you must prepare the audience with what they’re going to see, for example, you might be leading into a diagram that supports your statement. Also, before you show the visual aid , explain why you’re going to show it, for example, “This graph is a significant piece of evidence supporting X”.

When the graphic is on display get the audience to focus on it:

- The table indicates…

- As you can see…

- I’d like to direct your attention to…

Explain what the visual is showing:

- You can see that there has been a reduction in…

- The diagram is comparing the…

Using a visual aid to transition

Visual aids can also be used as transitions and they have the benefit of being stimulating and breaking-up vocal transitions.

You might have a slide with just a picture on it to signify to the audience that you’re moving on to a new point – ensure that this image is relevant to the point. Many speakers like to use cartoons for this purpose but ensure its suitable for your audience.

Always summarise your key points first in the conclusion:

- Let’s recap on what we’ve spoken about today…

- Let me briefly summarise the main points…

And then conclude:

If you have a shorter speech you may choose to end your presentation with one statement:

- In short…

- To sum up…

- In a nutshell…

- To summarise…

- In conclusion…

However, using statements such as “To conclude” may cause the audience to stop listening. It’s better to say:

- I’d like to leave you with this…

- What you should take away from this is…

- Finally, I want to say…

Call to action

Requesting the audience to do something at the end of the presentation:

- You may be thinking how can I help in this matter? Well…

- My aim is to encourage you to go further and…

- What I’m requesting of you is…

Common mistakes

When transitions are used poorly you can annoy and confuse the audience. Avoid:

- Using transitions that are too short – transitions are a key part of ensuring the audience understands your presentation so spend sufficient time linking to your next idea.

- Too many tangents – any digressions should still be relevant to the topic and help the audience with their understanding, otherwise cut them out.

- Incompatible transitions – for example, if you’re about to introduce an example that supports your statement you wouldn’t introduce this by saying “but”. Use transitions that signify the relationship between points.

- Over-using the same transition because this is boring for the audience to hear repeatedly. Ensure that there is variety with your transitions, consider including visual transitions.

- Miscounting your transitions – for example, don’t say “first point”, “second point”, “next point” – refer to your points consistently.

Speech transitions are useful for unifying and connecting your presentation. The audience are more likely to remain engaged since they’ll be able to follow your points. But remember that it’s important to practice your transitions beforehand and not just the content of your arguments because you risk looking unprofessional and confusing the audience if the presentation does not flow smoothly.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.2: Functions of Language

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 18450

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Identify and discuss the four main types of linguistic expressions.

- Discuss the power of language to express our identities, affect our credibility, control others, and perform actions.

- Discuss some of the sources of fun within language.

- Explain how neologisms and slang contribute to the dynamic nature of language.

- Identify the ways in which language can separate people and bring them together.

What utterances make up our daily verbal communication? Some of our words convey meaning, some convey emotions, and some actually produce actions. Language also provides endless opportunities for fun because of its limitless, sometimes nonsensical, and always changing nature. In this section, we will learn about the five functions of language, which show us that language is expressive, language is powerful, language is fun, language is dynamic, and language is relational.

Language Is Expressive

Verbal communication helps us meet various needs through our ability to express ourselves. In terms of instrumental needs, we use verbal communication to ask questions that provide us with specific information. We also use verbal communication to describe things, people, and ideas. Verbal communication helps us inform, persuade, and entertain others, which as we will learn later are the three general purposes of public speaking. It is also through our verbal expressions that our personal relationships are formed. At its essence, language is expressive. Verbal expressions help us communicate our observations, thoughts, feelings, and needs (McKay, Davis, & Fanning, 1995).

Expressing Observations

When we express observations, we report on the sensory information we are taking or have taken in. Eyewitness testimony is a good example of communicating observations. Witnesses are not supposed to make judgments or offer conclusions; they only communicate factual knowledge as they experienced it. For example, a witness could say, “I saw a white Mitsubishi Eclipse leaving my neighbor’s house at 10:30 pm.” As we learned in the chapter titled “Communication and Perception” on perception, observation and description occur in the first step of the perception-checking process. When you are trying to make sense of an experience, expressing observations in a descriptive rather than evaluative way can lessen defensiveness, which facilitates competent communication.

Expressing Thoughts

When we express thoughts, we draw conclusions based on what we have experienced. In the perception process, this is similar to the interpretation step. We take various observations and evaluate and interpret them to assign them meaning (a conclusion). Whereas our observations are based on sensory information (what we saw, what we read, what we heard), thoughts are connected to our beliefs (what we think is true/false), attitudes (what we like and dislike), and values (what we think is right/wrong or good/bad). Jury members are expected to express thoughts based on reported observations to help reach a conclusion about someone’s guilt or innocence. A juror might express the following thought: “The neighbor who saw the car leaving the night of the crime seemed credible. And the defendant seemed to have a shady past—I think he’s trying to hide something.” Sometimes people intentionally or unintentionally express thoughts as if they were feelings. For example, when people say, “I feel like you’re too strict with your attendance policy,” they aren’t really expressing a feeling; they are expressing a judgment about the other person (a thought).

Expressing Feelings

When we express feelings, we communicate our emotions. Expressing feelings is a difficult part of verbal communication, because there are many social norms about how, why, when, where, and to whom we express our emotions. Norms for emotional expression also vary based on nationality and other cultural identities and characteristics such as age and gender. In terms of age, young children are typically freer to express positive and negative emotions in public. Gendered elements intersect with age as boys grow older and are socialized into a norm of emotional restraint. Although individual men vary in the degree to which they are emotionally expressive, there is still a prevailing social norm that encourages and even expects women to be more emotionally expressive than men.

Expressing feelings can be uncomfortable for those listening. Some people are generally not good at or comfortable with receiving and processing other people’s feelings. Even those with good empathetic listening skills can be positively or negatively affected by others’ emotions. Expressions of anger can be especially difficult to manage because they represent a threat to the face and self-esteem of others. Despite the fact that expressing feelings is more complicated than other forms of expression, emotion sharing is an important part of how we create social bonds and empathize with others, and it can be improved.

In order to verbally express our emotions, it is important that we develop an emotional vocabulary. The more specific we can be when we are verbally communicating our emotions, the less ambiguous our emotions will be for the person decoding our message. As we expand our emotional vocabulary, we are able to convey the intensity of the emotion we’re feeling whether it is mild, moderate, or intense. For example, happy is mild, delighted is moderate, and ecstatic is intense; ignored is mild, rejected is moderate, and abandoned is intense (Hargie, 2011).

In a time when so much of our communication is electronically mediated, it is likely that we will communicate emotions through the written word in an e-mail, text, or instant message. We may also still use pen and paper when sending someone a thank-you note, a birthday card, or a sympathy card. Communicating emotions through the written (or typed) word can have advantages such as time to compose your thoughts and convey the details of what you’re feeling. There are also disadvantages in that important context and nonverbal communication can’t be included. Things like facial expressions and tone of voice offer much insight into emotions that may not be expressed verbally. There is also a lack of immediate feedback. Sometimes people respond immediately to a text or e-mail, but think about how frustrating it is when you text someone and they don’t get back to you right away. If you’re in need of emotional support or want validation of an emotional message you just sent, waiting for a response could end up negatively affecting your emotional state.

Expressing Needs

When we express needs, we are communicating in an instrumental way to help us get things done. Since we almost always know our needs more than others do, it’s important for us to be able to convey those needs to others. Expressing needs can help us get a project done at work or help us navigate the changes of a long-term romantic partnership. Not expressing needs can lead to feelings of abandonment, frustration, or resentment. For example, if one romantic partner expresses the following thought “I think we’re moving too quickly in our relationship” but doesn’t also express a need, the other person in the relationship doesn’t have a guide for what to do in response to the expressed thought. Stating, “I need to spend some time with my hometown friends this weekend. Would you mind if I went home by myself?” would likely make the expression more effective. Be cautious of letting evaluations or judgments sneak into your expressions of need. Saying “I need you to stop suffocating me!” really expresses a thought-feeling mixture more than a need.

Source: Adapted from Matthew McKay, Martha Davis, and Patrick Fanning, Messages: Communication Skills Book , 2nd ed. (Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, 1995), 34–36.

Language Is Powerful

The contemporary American philosopher David Abram wrote, “Only if words are felt, bodily presences, like echoes or waterfalls, can we understand the power of spoken language to influence, alter, and transform the perceptual world” (Abram, 1997). This statement encapsulates many of the powerful features of language. Next, we will discuss how language expresses our identities, affects our credibility, serves as a means of control, and performs actions.

Language Expresses Our Identities

In the opening to this chapter, I recounted how an undergraduate class in semantics solidified my love of language. I could have continued on to say that I have come to think of myself as a “word nerd.” Words or phrases like that express who we are and contribute to the impressions that others make of us. We’ve already learned about identity needs and impression management and how we all use verbal communication strategically to create a desired impression. But how might the label word nerd affect me differently if someone else placed it on me?

The power of language to express our identities varies depending on the origin of the label (self-chosen or other imposed) and the context. People are usually comfortable with the language they use to describe their own identities but may have issues with the labels others place on them. In terms of context, many people express their “Irish” identity on St. Patrick’s Day, but they may not think much about it over the rest of the year. There are many examples of people who have taken a label that was imposed on them, one that usually has negative connotations, and intentionally used it in ways that counter previous meanings. Some country music singers and comedians have reclaimed the label redneck , using it as an identity marker they are proud of rather than a pejorative term. Other examples of people reclaiming identity labels is the “black is beautiful” movement of the 1960s that repositioned black as a positive identity marker for African Americans and the “queer” movement of the 1980s and ’90s that reclaimed queer as a positive identity marker for some gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people. Even though some people embrace reclaimed words, they still carry their negative connotations and are not openly accepted by everyone.

Language Affects Our Credibility

One of the goals of this chapter is to help you be more competent with your verbal communication. People make assumptions about your credibility based on how you speak and what you say. Even though we’ve learned that meaning is in people rather than words and that the rules that govern verbal communication, like rules of grammar, are arbitrary, these norms still mean something. You don’t have to be a perfect grammarian to be perceived as credible. In fact, if you followed the grammar rules for written communication to the letter you would actually sound pretty strange, since our typical way of speaking isn’t as formal and structured as writing. But you still have to support your ideas and explain the conclusions you make to be seen as competent. You have to use language clearly and be accountable for what you say in order to be seen as trustworthy. Using informal language and breaking social norms we’ve discussed so far wouldn’t enhance your credibility during a professional job interview, but it might with your friends at a tailgate party. Politicians know that the way they speak affects their credibility, but they also know that using words that are too scientific or academic can lead people to perceive them as eggheads, which would hurt their credibility. Politicians and many others in leadership positions need to be able to use language to put people at ease, relate to others, and still appear confident and competent.

Language Is a Means of Control

Control is a word that has negative connotations, but our use of it here can be positive, neutral, or negative. Verbal communication can be used to reward and punish. We can offer verbal communication in the form of positive reinforcement to praise someone. We can withhold verbal communication or use it in a critical, aggressive, or hurtful way as a form of negative reinforcement.

Directives are utterances that try to get another person to do something. They can range from a rather polite ask or request to a more forceful command or insist . Context informs when and how we express directives and how people respond to them. Promises are often paired with directives in order to persuade people to comply, and those promises, whether implied or stated, should be kept in order to be an ethical communicator. Keep this in mind to avoid arousing false expectations on the part of the other person (Hayakawa & Hayakawa, 1990).

Rather than verbal communication being directed at one person as a means of control, the way we talk creates overall climates of communication that may control many. Verbal communication characterized by empathy, understanding, respect, and honesty creates open climates that lead to more collaboration and more information exchange. Verbal communication that is controlling, deceitful, and vague creates a closed climate in which people are less willing to communicate and less trusting (Brown, 2006).

Language Is Performative

Some language is actually more like an action than a packet of information. Saying, “I promise,” “I guarantee,” or “I pledge,” does more than convey meaning; it communicates intent. Such utterances are called commissives, as they mean a speaker is committed to a certain course of action (Crystal, 2005). Of course, promises can be broken, and there can be consequences, but other verbal communication is granted official power that can guarantee action. The two simple words I do can mean that a person has agreed to an oath before taking a witness stand or assuming the presidency. It can also mean that two people are now bound in a relationship recognized by the government and/or a religious community. These two words, if said in the right context and in front of the right person, such as a judge or a reverend, bring with them obligations that cannot be undone without additional steps and potential negative repercussions. In that sense, language is much more than “mere words.”

Performative language can also be a means of control, especially in legal contexts. In some cases, the language that makes our laws is intentionally vague. In courts all over the nation, the written language intersects with spoken language as lawyers advocate for particular interpretations of the written law. The utterances of judges and juries set precedents for reasonable interpretations that will then help decide future cases. Imagine how powerful the words We the jury find the defendant… seem to the defendant awaiting his or her verdict. The sentences handed down by judges following a verdict are also performative because those words impose fines, penalties, or even death. Some language is deemed so powerful that it is regulated. Hate speech, which we will learn more about later, and slander, libel, and defamation are considered powerful enough to actually do damage to a person and have therefore been criminalized.

Language Is Fun

Word games have long been popular. Before Words with Friends there was Apples to Apples, Boggle, Scrabble, and crossword puzzles. Writers, poets, and comedians have built careers on their ability to have fun with language and in turn share that fun with others. The fun and frivolity of language becomes clear as teachers get half-hearted laughs from students when they make puns, Jay Leno has a whole bit where he shows the hilarious mistakes people unintentionally make when they employ language, and people vie to construct the longest palindromic sentence (a sentence that as the same letters backward and forward).

The productivity and limitlessness of language we discussed earlier leads some people to spend an inordinate amount of time discovering things about words. Two examples that I have found fascinating are palindromes and contranyms. Palindromes, as noted, are words that read the same from left to right and from right to left. Racecar is a commonly cited example, but a little time spent looking through Google results for palindromes exposes many more, ranging from “Live not on evil” to “Doc, note I dissent. A fast never prevents a fatness. I diet on cod.” [1] Contranyms are words that have multiple meanings, two of which are opposites. For example, sanction can mean “to allow” and “to prevent,” and dust can mean “to remove particles” when used in reference to furniture or “to add particles” when used in reference to a cake. These are just two examples of humorous and contradictory features of the English language—the book Crazy English by Richard Lederer explores dozens more. A fun aspect of language enjoyed by more people than a small community of word enthusiasts is humor.

There are more than one hundred theories of humor, but none of them quite captures the complex and often contradictory nature of what we find funny (Foot & McCreaddie, 2006). Humor is a complicated social phenomenon that is largely based on the relationship between language and meaning. Humor functions to liven up conversations, break the ice, and increase group cohesion. We also use humor to test our compatibility with others when a deep conversation about certain topics like politics or religion would be awkward. Bringing up these topics in a lighthearted way can give us indirect information about another person’s beliefs, attitudes, and values. Based on their response to the humorous message, we can either probe further or change the subject and write it off as a poor attempt at humor (Foot & McCreaddie, 2006). Using humor also draws attention to us, and the reactions that we get from others feeds into our self-concept. We also use humor to disclose information about ourselves that we might not feel comfortable revealing in a more straightforward way. Humor can also be used to express sexual interest or to cope with bad news or bad situations.

We first start to develop an understanding of humor as children when we realize that the words we use for objects are really arbitrary and can be manipulated. This manipulation creates a distortion or incongruous moment in the reality that we had previously known. Some humor scholars believe that this early word play—for example, calling a horse a turtle and a turtle a horse—leads us to appreciate language-based humor like puns and riddles (Foot & McCreaddie, 2006). It is in the process of encoding and decoding that humor emerges. People use encoding to decide how and when to use humor, and people use decoding to make sense of humorous communication. Things can go wrong in both of those processes. I’m sure we can all relate to the experience of witnessing a poorly timed or executed joke (a problem with encoding) and of not getting a joke (a problem with decoding).

Language Is Dynamic

As we already learned, language is essentially limitless. We may create a one-of-a-kind sentence combining words in new ways and never know it. Aside from the endless structural possibilities, words change meaning, and new words are created daily. In this section, we’ll learn more about the dynamic nature of language by focusing on neologisms and slang.

Neologisms are newly coined or used words. Newly coined words are those that were just brought into linguistic existence. Newly used words make their way into languages in several ways, including borrowing and changing structure. Taking is actually a more fitting descriptor than borrowing , since we take words but don’t really give them back. In any case, borrowing is the primary means through which languages expand. English is a good case in point, as most of its vocabulary is borrowed and doesn’t reflect the language’s Germanic origins. English has been called the “vacuum cleaner of languages” (Crystal, 2005). Weekend is a popular English word based on the number of languages that have borrowed it. We have borrowed many words, like chic from French, karaoke from Japanese, and caravan from Arabic.

Structural changes also lead to new words. Compound words are neologisms that are created by joining two already known words. Keyboard , newspaper , and giftcard are all compound words that were formed when new things were created or conceived. We also create new words by adding something, subtracting something, or blending them together. For example, we can add affixes, meaning a prefix or a suffix, to a word. Affixing usually alters the original meaning but doesn’t completely change it. Ex-husband and kitchenette are relatively recent examples of such changes (Crystal, 2005). New words are also formed when clipping a word like examination , which creates a new word, exam , that retains the same meaning. And last, we can form new words by blending old ones together. Words like breakfast and lunch blend letters and meaning to form a new word— brunch .

Existing words also change in their use and meaning. The digital age has given rise to some interesting changes in word usage. Before Facebook, the word friend had many meanings, but it was mostly used as a noun referring to a companion. The sentence, I’ll friend you , wouldn’t have made sense to many people just a few years ago because friend wasn’t used as a verb. Google went from being a proper noun referring to the company to a more general verb that refers to searching for something on the Internet (perhaps not even using the Google search engine). Meanings can expand or contract without changing from a noun to a verb. Gay , an adjective for feeling happy, expanded to include gay as an adjective describing a person’s sexual orientation. Perhaps because of the confusion that this caused, the meaning of gay has contracted again, as the earlier meaning is now considered archaic, meaning it is no longer in common usage.

The American Dialect Society names an overall “Word of the Year” each year and selects winners in several more specific categories. The winning words are usually new words or words that recently took on new meaning. [2] In 2011, the overall winner was occupy as a result of the Occupy Wall Street movement. The word named the “most likely to succeed” was cloud as a result of Apple unveiling its new online space for file storage and retrieval. Although languages are dying out at an alarming rate, many languages are growing in terms of new words and expanded meanings, thanks largely to advances in technology, as can be seen in the example of cloud .

Slang is a great example of the dynamic nature of language. Slang refers to new or adapted words that are specific to a group, context, and/or time period; regarded as less formal; and representative of people’s creative play with language. Research has shown that only about 10 percent of the slang terms that emerge over a fifteen-year period survive. Many more take their place though, as new slang words are created using inversion, reduction, or old-fashioned creativity (Allan & Burridge, 2006). Inversion is a form of word play that produces slang words like sick , wicked , and bad that refer to the opposite of their typical meaning. Reduction creates slang words such as pic , sec , and later from picture , second , and see you later . New slang words often represent what is edgy, current, or simply relevant to the daily lives of a group of people. Many creative examples of slang refer to illegal or socially taboo topics like sex, drinking, and drugs. It makes sense that developing an alternative way to identify drugs or talk about taboo topics could make life easier for the people who partake in such activities. Slang allows people who are in “in the know” to break the code and presents a linguistic barrier for unwanted outsiders. Taking a moment to think about the amount of slang that refers to being intoxicated on drugs or alcohol or engaging in sexual activity should generate a lengthy list.

When I first started teaching this course in the early 2000s, Cal Poly Pomona had been compiling a list of the top twenty college slang words of the year for a few years. The top slang word for 1997 was da bomb , which means “great, awesome, or extremely cool,” and the top word for 2001 and 2002 was tight , which is used as a generic positive meaning “attractive, nice, or cool.” Unfortunately, the project didn’t continue, but I still enjoy seeing how the top slang words change and sometimes recycle and come back. I always end up learning some new words from my students. When I asked a class what the top college slang word should be for 2011, they suggested deuces , which is used when leaving as an alternative to good-bye and stems from another verbal/nonverbal leaving symbol—holding up two fingers for “peace” as if to say, “peace out.”

It’s difficult for my students to identify the slang they use at any given moment because it is worked into our everyday language patterns and becomes very natural. Just as we learned here, new words can create a lot of buzz and become a part of common usage very quickly. The same can happen with new slang terms. Most slang words also disappear quickly, and their alternative meaning fades into obscurity. For example, you don’t hear anyone using the word macaroni to refer to something cool or fashionable. But that’s exactly what the common slang meaning of the word was at the time the song “Yankee Doodle” was written. Yankee Doodle isn’t saying the feather he sticks in his cap is a small, curved pasta shell; he is saying it’s cool or stylish.

“Getting Plugged In”: Is “Textese” Hurting Our Verbal Communication?

Textese, also called text-message-ese and txt talk, among other things, has been called a “new dialect” of English that mixes letters and numbers, abbreviates words, and drops vowels and punctuation to create concise words and statements. Although this “dialect” has primarily been relegated to the screens of smartphones and other text-capable devices, it has slowly been creeping into our spoken language (Huang, 2011). Some critics say textese is “destroying” language by “pillaging punctuation” and “savaging our sentences” (Humphrys, 2007). A relatively straightforward tks for “thanks” or u for “you” has now given way to textese sentences like IMHO U R GR8 . If you translated that into “In my humble opinion, you are great,” then you are fluent in textese. Although teachers and parents seem convinced that this type of communicating will eventually turn our language into emoticons and abbreviations, some scholars aren’t. David Crystal, a well-known language expert, says that such changes to the English language aren’t new and that texting can actually have positive effects. He points out that Shakespeare also abbreviated many words, played with the rules of language, and made up several thousand words, and he is not considered an abuser of language. He also cites research that found, using experimental data, that children who texted more scored higher on reading and vocabulary tests. Crystal points out that in order to play with language, you must first have some understanding of the rules of language (Huang, 2011).

- What effects, if any, do you think textese has had on your non-text-message communication?

- Overall do you think textese and other forms of computer-mediated communication have affected our communication? Try to identify one potential positive and negative influence that textese has had on our verbal communication.

Language Is Relational

We use verbal communication to initiate, maintain, and terminate our interpersonal relationships. The first few exchanges with a potential romantic partner or friend help us size the other person up and figure out if we want to pursue a relationship or not. We then use verbal communication to remind others how we feel about them and to check in with them—engaging in relationship maintenance through language use. When negative feelings arrive and persist, or for many other reasons, we often use verbal communication to end a relationship.

Language Can Bring Us Together