- DSpace@MIT Home

- MIT Libraries

- Undergraduate Theses

Inclusive : a human centered approach to accessible architectural design

Alternative title

Other contributors, terms of use, description, date issued, collections.

Architecture without barriers: designing inclusive environments accessible to all

- Master of Architecture

- Architecture

Granting Institution

Lac thesis type.

- Thesis Project

Thesis Advisor

Usage metrics.

- Architectural design

- Architecture, n.e.c.

DigitalCommons@RISD

- < Previous

Home > Graduate Studies > Masters Theses > 767

- Masters Theses

Inclusive multi-sensory landscape: directing visually impaired people in a perception world

Tianqi Chen , Rhode Island School of Design Follow

Date of Award

Spring 6-1-2021

Document Type

Degree name.

Master of Landscape Architecture (MLA)

Landscape Architecture

First Advisor

Nick De Pace

Second Advisor

This thesis explored the use of inclusive landscape design to provide visually impaired people and normal people with enhanced multi-sensory experiences, and for recognizing space, navigating move through spaces. inclusive design is human design, inviting people in and giving the communicative power to space through stimulating one’s intuition and senses by repetition, sequencing, or patterning in design that signals time, space, and movement through the layouts of walking trajectories between important nodes or places of refuge. through the visually impaired issue studies, solutions, and methods exploration, i developed principles as a solver, applied them on one site to transform space for testing my theory. this theory aimed to enhance public awareness of visually impaired people, pay attention to their outdoor experiences and provide everyone enhanced space experiences and motivate multisensory to emphasize the critical nodes, connect the fragmented spaces, direct people walking through intersections safely, and indicatively..

View exhibition online: Tianqi Chen, Inclusive Multi-sensory Landscape

Recommended Citation

Chen, Tianqi, "Inclusive multi-sensory landscape: directing visually impaired people in a perception world" (2021). Masters Theses . 767. https://digitalcommons.risd.edu/masterstheses/767

Creative Commons License

Since September 17, 2021

Included in

Landscape Architecture Commons

To view the content in your browser, please download Adobe Reader or, alternately, you may Download the file to your hard drive.

NOTE: The latest versions of Adobe Reader do not support viewing PDF files within Firefox on Mac OS and if you are using a modern (Intel) Mac, there is no official plugin for viewing PDF files within the browser window.

- All Collections

- Departments

- Online Exhibitions

- Disciplines

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

Contributor Info

- Contributor FAQ

- Submit Research

- RISD Graduate Studies

Permissions

- Terms of Use

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Inclusive Design – Go Beyond Accessibility

- Conference paper

- First Online: 10 July 2020

- Cite this conference paper

- Roland Buß 9

Part of the book series: Lecture Notes in Computer Science ((LNISA,volume 12183))

Included in the following conference series:

- International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction

2244 Accesses

Inclusion pays off, but how to make that happen? Inclusive design describes a widely acknowledged approach combining user centered design principles and accessibility demands. Recent studies show a strong positive impact of accessibility on the overall user experience. This article provides a brief overview on accessibility regulations and requirements. We will go beyond these regulations to achieve design recommendations that enable efficient product design. Also, we will introduce prerequisites for a large-scale adoption of these principles.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Schmutz, S., Sonderegger, A., Sauer, J.: Implementing recommendations from web accessibility guidelines: would they also provide benefits to nondisabled users. Hum. Factors 58 (4), 611–629 (2016)

Google Scholar

Buß, R., Kreichgauer, U., Meixner, C., Rangott, A.-M.: Barrierefreiheit effizient gestalten. In: Proceedings of Mensch und Computer Conference (2016)

EN 17161: Design for All - Accessibility following a Design for All approach in products, goods and services - Extending the range of users, Beuth (2019)

EN 301 549 V2.1.2 (2018-08): Accessibility requirements for ICT products and services. European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) (2018)

Fiori Design Guidelines. https://experience.sap.com/fiori-design-web/ . Accessed 1 Mar 2020

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21/ . Accessed 1 Mar 2020

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

SAP SE, Dietmar-Hopp-Allee 16, 69190, Walldorf, Germany

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Roland Buß .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

The Open University of Japan, Chiba, Japan

Masaaki Kurosu

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Buß, R. (2020). Inclusive Design – Go Beyond Accessibility. In: Kurosu, M. (eds) Human-Computer Interaction. Human Values and Quality of Life. HCII 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 12183. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49065-2_28

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49065-2_28

Published : 10 July 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-49064-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-49065-2

eBook Packages : Computer Science Computer Science (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Title: Co-Design with Neurodivergent Students and Recent Graduates to Develop an Inclusive Pedagogy in Design Education

Associated Organization(s)

Collections, supplementary to, permanent link, date issued, resource type, resource subtype, rights statement.

15 Examples of Truly Inclusive Architecture

“The world is your oyster” are words we all like to live by, but how can the same world be depicted as an “oyster” for seven billion people with completely different backgrounds in all permutations and combinations possible? Quite paradoxically , it is the diversity that makes survival possible and ties the world together.

“Inclusive” architecture refers to any space that can be seamlessly used by all the user groups possible in that particular context. Inclusive designs must be easy to use by all types of people- children, adults, senior citizens , women, men, transgender people, the entire LGBTQ community , physically as well as mentally handicapped users- the list goes on. Hence, the main objective of truly inclusive design must be to make these spaces as barrier-free and convenient to use as possible. Inclusive spaces also have the potential to enable and empower users. Inclusive or universal design has only recently started becoming the norm, but hey- better late than never!

1. Enabling Village by WOHA, Singapore

Singapore as a city itself is quite popularly known for being inclusive and citizen-friendly in terms of its designs as well as governance. The Enabling Village is a community center built as an adaptive reuse project of the fifty-year-old Bukit Merah Vocational Institute. Since its redevelopment, the property has added value to the neighborhood and its community. It has been integrated into the pedestrian network of the neighborhood with strategically placed entrances, ramps, and spacious passages and corridors, thus enabling easy movement and access for every type of user.

2. Musholm by AART architects, Denmark

Developed by the Danish Muscular Dystrophy Foundation, this holiday and sports center has been beautifully designed to cater to people with disabilities. It includes spacious multi-purpose halls, holiday homes, and a 110m activity ramp. The building opens out into the serene natural landscape of the surroundings, thus enhancing the user experience. In 2016, this center won the IAUD Award for being the world’s most socially inclusive place.

https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/rtf-fresh-perspectives/a938-15-examples-of-truely-inclusive-architecture/#246a1581098e2230ca2fdc03709b2fb486a97ed3#120926

3. Robson Square by Cornelia Oberlander, Vancouver

A sunken “linear urban park” built in a prime locality of Vancouver surrounded by civic buildings, the Robson square is a one-of-a-kind urban space that leaves no user feeling left out. The space is easy and flexible to access by differently-abled pedestrians, and the staircases connecting its various levels have been brilliantly integrated with ramps. The use of waterfalls cools down the concrete environment and gives it a softer look and feel.

4. The Friendship Park by Marcelo Roux + Gastón Cuña, Uruguay

Every single element of this park is perfectly user-friendly towards children and youth belonging to any part of the disability spectrum- both physical and mental. Free of any obstacles, the layout of the space has been designed such that there are absolutely no sharp edges or corners, thus facilitating easy movement across the park. A variety of playful textures have been added to the design for the blind. The park leaves no stone unturned- each and every play equipment is absolutely inclusive.

5. Laurent House by Frank Lloyd Wright, USA

Back in 1949, legendary architect, F.L.Wright had been commissioned to design a house for a woman and her paraplegic husband- and without a doubt, Wright was able to achieve inclusivity in his design quite astutely. The functional and sensibly designed house was accommodated with spaces and passages that were large and attracted maximum sun exposure. Furthermore, this single-story home is F. L. Wright’s only inclusive design project.

6. Bikurim Inclusive School by Sarit Shani Hay, Tel Aviv

This school, flagged as the first inclusive school in Tel Aviv, is designed to cater to each child’s specific needs- handicapped or not. By providing spaces for meditation and yoga, the architect is encouraging the use of holistic methods to nurture the children. The flexibility in the design of the spaces promotes equality amongst the differently-abled children, thus supporting the inclusive philosophy of the organization.

7. DeafSpace at Gallaudet University, by Hansen Bauman

The DeafSpace is a project implemented by the ASL Deaf Studies Department at Gallaudet University. This project is now used as a guideline for designing spaces for the deaf. The spaces here have been designed to consist of clearly visible sightlines, strategically placed mirrors, empathetic orientation in terms of its layout, and optimal lighting to provide the best user experience for the deaf. The design of the space provides excellent information about how deaf people accustom themselves to walk around a space, by interrelating their senses.

8. Centre for People with Disabilities ASPAYM ÁVILA by amas arquitectura

A rehabilitation center for the disabled, this building contains no visible structural elements or obstacles that could mar the movement of the users. The transparent partition walls also ensure visual connectivity between the rooms. Non-slip tiling has been used throughout the course of the plan, and the use of low ceilings and deep beams ensure visibility by people lying in stretchers or sitting in wheelchairs, thus creating a sense of place and making the users feel like they belong.

9. Casa MAC by So & So Studio, Italy

The architect has used textured stone tiles in continuity throughout to help the user identify different spaces a navigate through the house. To avoid any confusion, all the rooms have been accommodated around a main spinal corridor which terminates in the kitchen on one end and bedroom on the other. The linear layout of the house makes it easy for the user to identify the spaces and get accustomed to it.

10. Regent Park Aquatic Centre by MacLennan Jaunkalns Miller Architects, Toronto

Regent Park was once infamous for being home to low-income groups in the majority. However, after the establishment of the Aquatic Centre, the inherent value of the locality increased and it now is one of the city’s most loved community centers. Boasting an area of twenty-eight thousand square feet, this building is designed to be a safe space for all kinds of people. It caters to all classes and income levels. The openness and visual connectivity of the design make it a safe space for vulnerable groups of people. Quite unusually, the changing rooms here are not separated- there are common changing rooms for men and women with private cubicles, thus creating a sense of ease and belonging for the entire gender spectrum.

11. The X-Suite by M-RAD architects, USA

A series of five cabins situated in a picturesque site at the Yosemite National Park have been designed in compliance with the American with Disabilities Act (ADA). These cabins are rectangular in plan, accommodated with a wooden deck on the outsidewhich leads towards a double French door, thus providing plenty of space to facilitate entry. All elements from the immense width of the rooms to the features of the shower, comply with the ADA rules, making a great user experience for the disabled.

12. Kent Timber House by Nash Baker Architects, England

This house has been designed for a couple who plan to retire here, and thus the layout is flexible, accessible, and disabled as well as elderly-friendly. The open plan and barrier-free spaces encourage ease of movement, and the material palette is subtle and easy on the eyes.

13. Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture by David Adjaye, USA

While this architectural marvel consisting of massive column-free spaces has been designed keeping in mind its disabled users, more importantly, it has been designed to be socially and politically inclusive as well as exhibits a very important course of events in African-American history. In fact, this monumental space won the Beazley Design of the Year Award in 2017.

14. Modular homes by ShedKM and Urban Splash in England

The House project by ShedKM has erected a series of prefabricated affordable housing units that have redefined the meaning of the word “housing.” These housing units have identical facades, but the interiors are flexible and can be modified by the owner or user based on their needs- and hence these housing units are truly inclusive.

15. Baotou Vanke Central Park by ZAP Associates, China

This urban renewal project integrates several interactive and participatory spaces over an area of approximately ninety-thousand square meters. The wide, organically curved paths offer flexible movement for differently-abled pedestrians. Several interactive zones ensure activity engagement for all age groups.

Tirthika Shah is a budding architect and designer who is passionate about sustainability and finding innovative solutions to the environmental crisis. She is a firm believer in inclusion, diversity and human equality & fairness to all.She is social media savvy and uses it creatively emphasizing on visual imagery to communicate impactfully with her audience. She is a food lover and you will often find desserts on her instagram.

8 Examples of Adaptive Re-Use Around The World

Hydroponics- A Growing Trend in Architecture

Related posts.

Sustainable Strategies of Vernacular Architecture

Evolving Perspectives: A Journey Through Architecture Education

Luxury Housing and Sustainable Materials

The Interplay of Form and Function: Exploring Artistic Elements in Architectural Design

Architecture of the Ancient Roman Baths

Building Connections: The Integral Role of Architecture in Human Existence and Community

- Architectural Community

- Architectural Facts

- RTF Architectural Reviews

- Architectural styles

- City and Architecture

- Fun & Architecture

- History of Architecture

- Design Studio Portfolios

- Designing for typologies

- RTF Design Inspiration

- Architecture News

- Career Advice

- Case Studies

- Construction & Materials

- Covid and Architecture

- Interior Design

- Know Your Architects

- Landscape Architecture

- Materials & Construction

- Product Design

- RTF Fresh Perspectives

- Sustainable Architecture

- Top Architects

- Travel and Architecture

- Rethinking The Future Awards 2022

- RTF Awards 2021 | Results

- GADA 2021 | Results

- RTF Awards 2020 | Results

- ACD Awards 2020 | Results

- GADA 2019 | Results

- ACD Awards 2018 | Results

- GADA 2018 | Results

- RTF Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2016 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2015 | Results

- RTF Awards 2014 | Results

- RTF Architectural Visualization Competition 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2020 – Results

- Designer’s Days of Quarantine Contest – Results

- Urban Sketching Competition May 2020 – Results

- RTF Essay Writing Competition April 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2019 – Finalists

- The Ultimate Thesis Guide

- Introduction to Landscape Architecture

- Perfect Guide to Architecting Your Career

- How to Design Architecture Portfolio

- How to Design Streets

- Introduction to Urban Design

- Introduction to Product Design

- Complete Guide to Dissertation Writing

- Introduction to Skyscraper Design

- Educational

- Hospitality

- Institutional

- Office Buildings

- Public Building

- Residential

- Sports & Recreation

- Temporary Structure

- Commercial Interior Design

- Corporate Interior Design

- Healthcare Interior Design

- Hospitality Interior Design

- Residential Interior Design

- Sustainability

- Transportation

- Urban Design

- Host your Course with RTF

- Architectural Writing Training Programme | WFH

- Editorial Internship | In-office

- Graphic Design Internship

- Research Internship | WFH

- Research Internship | New Delhi

- RTF | About RTF

- Submit Your Story

Looking for Job/ Internship?

Rtf will connect you with right design studios.

Our Impact Publications and Research Inclusive design in action: Using inclusive design to create a fair transition to net zero

Inclusive design in action: Using inclusive design to create a fair transition to net zero

Inclusive design is the practice of designing products and services so that everyone can use them. It involves designing out barriers to access that create exclusion, inequality and unfairness in markets.

The transition to net zero is an opportunity to create a future energy system that is inclusive, and a market where low income consumers could actively engage with and benefit from the transition.

In Spring 2022 Participatory Action Research (PAR) group of professional researchers and consumers with lived experience of the energy poverty premium worked in partnership on proposals that explore what a fair transition to net zero for low income consumers could look like.

Published in January 2023 by Fair By Design, Toynbee Hall, and OFGEM.

Newsletter sign-up

Keep up-to-date with our news and events

" * " indicates required fields

Privacy Overview

Expert Guides

What is Inclusive Design?

By Andrew Biro May 22, 2024

The Bergami Center. Photo by Peter Aaron/OTTO

Story at a glance:

- Inclusive design is an approach to design that takes into account the full range of human diversity in order to create products, services, and environments that are as accessible and as usable as possible.

- Inclusive design is closely related to accessible design and universal design but places a higher emphasis on diversity and the creation of one-size-fits-one solutions.

- The Bergami Center for Science, Technology, and Innovation at the University of New Haven demonstrates how inclusive design may be implemented in the AEC Sector.

In an age where thoughtfulness seems largely absent from the technologies, products, and environments we interact with on a daily basis, inclusive design provides a breath of fresh air for everyone involved.

In this article we’ll cover the basics of inclusive design—including what it is, its importance, and how it can be applied in various contexts—as well as take a look at a few examples of how inclusive design can be implemented in the built environment.

The Winthrop Public Library was designed using inclusive design principles. Photo by Benjamin Drummond

Inclusive design is a design methodology that takes into account the full range of human diversity with regard to age, gender, language, ability, culture, race, and other identities or forms of human difference. The British Standards Institute defines inclusive design as “the design of mainstream products and/or services that are accessible to, and usable by, as many people as reasonably possible.”

Inclusive design recognizes that it is not always appropriate—and often isn’t possible—to design a single product, service, or environment that addresses the needs of the entire population, thus emphasizing the need for multiple solutions for different groups of people. The Inclusive Design Research Center considers the following three dimensions as being integral to inclusive design:

- Recognize diversity and uniqueness . Inclusive design must keep the diversity and uniqueness of each individual in mind as opposed to smoothing over differences or attempting to enforce a uniform, mass solution; suggests that the best method for achieving inclusive design is to integrate flexible one-size-fits-one configurations that allow for personalization and self-determination.

- Inclusive process and tools . Recognizes that inclusive design teams should be as diverse as possible and include those persons the product, service, or environment is being designed for to facilitate equitable participation; effective inclusive design also necessitates that design and development tools be as usable and accessible as possible.

- Broader beneficial impact . Inclusive designers have a responsibility to be aware of the context and broader impact of their designs and strive to achieve a beneficial impact beyond the intended beneficiaries of the design; requires inclusive design be integrated into design in general.

In practice inclusive design is most often applied to technologies and user interfaces—i.e. things that can be easily adapted and updated over time to reflect the ever-changing spectrum of human experiences—but can in theory be applied across a range of contexts, with architecture being one of them.

Inclusive vs. Accessible vs. Universal Design

Park Avenue Green is fully accessible; 5% of the units are handicap accessible, and the rest are adaptable. Photo by John Bartlestone Photography

Inclusive design is often used interchangeably with accessible and universal design, two other design philosophies that aim to break down barriers between humans and technology. Despite their common goals, however, each ultimately represents a distinct approach to design:

- Inclusive design . Looks to create products, services, and environments that understand and enable people of all demographic backgrounds and abilities.

- Accessible design . Is concerned exclusively with making buildings, interfaces, and other technologies usable to people with disabilities (including physical, visual, auditory, and cognitive disabilities); accessible design has a narrower scope than inclusive design as it is focused on ensuring specific accommodations are met.

- Universal design . Aims to create a single design solution that may be accessed and used by as many people as possible, without need for adaptations or specialized design strategies; universal design has its origins in architecture and is best suited to buildings and other tangible or environmental contexts.

All three types of design can, and often do, overlap with one another, especially when it comes to inclusive and universal design in the built environment. From a technical standpoint, however, each type of design should be regarded as fundamentally separate from the others.

Applications for Inclusive Design

Inclusive design can be implemented in the creation of digital interfaces, consumer products, and built environments. Photo by Peter Aaron/OTTO

Inclusive design can be implemented across a range of contexts, with the most common being technology/interfaces, consumer products/services, and architecture/environments.

Technology & Interfaces

Inclusive design is often easiest to implement when designing or adapting technologies and user interfaces (UI), as the inherently digital nature of these things makes them incredibly adaptable and customizable.

Microsoft’s approach to inclusive design, for example, is based on three basic principles:

- Recognize exclusion . Accept that all persons have their own internal biases and recognize that designing without confronting these biases often results in exclusion of certain groups; user research and testing can be valuable tools when it comes to revealing potential points of exclusion.

- Learn from diversity . Place people at the center of the inclusive design process and involve as many different perspectives as possible to ensure a diversity of ideas, experiences, and concerns.

- Solve for one, extend to many . Each person has their own unique set of abilities and limitations, but designing products for people with chronic or permanent disabilities ultimately creates solutions that benefit all users.

One of the more common examples of inclusive interface design is the addition of a “dark mode” option to websites and apps, in which white or light-colored backgrounds are changed to black and black text becomes white. Such an option is extremely beneficial for seniors and other persons who may have difficulty processing light-colored interfaces—either due to cataracts, light sensitivity, or other vision issues—but many other users find the feature useful in relieving eye strain or for browsing during low-light conditions as well.

Consumer Products

When it comes to consumer products, inclusive design overlaps considerably with accessible design. Rather than develop one-size-fits-all products, the Inclusive Design Toolkit suggests using inclusive design to:

- Create families of products and product derivatives to provide solutions to the best possible coverage of the population.

- Ensure that all products have clear and distinct target users.

- Reduce the level of ability required to use each product so as to improve the user experience for a varied range of customers, across a broad array of situations.

One such example of inclusive design in non-digital consumer products is Singaporean clothing brand Will & Well’s Adaptable collection of clothes featuring alternatives to buttons, back zips, hook-and-eye closures, armholes, and other traditional clothing elements. Though it is designed to make it easier for people with disabilities or restricted mobility to dress themselves, the Adaptable collection is not marketed as a disability-only clothing line, as everyone can benefit from ease in dressing.

Architecture & the Built Environment

While universal design is often the more practical approach when designing buildings and other spaces in the built environment, inclusive design still has its place in the AEC sector. In 2006 the UK Design Council’s Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) developed the following set of inclusive design principles:

- Encourage Involvement . The best way to create an inclusive built environment is to involve people from all walks of life in the planning and design phases in order to ensure that the end product is truly representative of the people using it.

- Acknowledge Diversity . Inclusive design recognizes, acknowledges, and celebrates the diversity of people to a greater extent than either accessible or universal design. It is this recognition of diversity that makes inclusive design successful, as it helps uncover different perspectives and reduces the likelihood of any one bias or assumption influencing design decisions.

- Provide Choices . In situations where a single design solution is incapable of meeting the needs of all users, inclusive design provides choices—not as afterthoughts or small concessions, but as thoughtful, intentional options built into the fabric of the space itself.

- Incorporate Flexibility . Another key characteristic of inclusive spaces is flexibility—that is, they are designed to be capable of adapting to changing uses, needs, and demands over time; by designing for flexibility at the outset, inclusive buildings are also more likely to remain operational following changes in ownership, demographics, or functionality rather than succumb to obsolescence.

- Design for Convenience . Finally, inclusive design isn’t just about designing spaces that everyone can use or navigate, but creating spaces that are also convenient and enjoyable for everyone to use and navigate.

How to Implement Inclusive Design in the Built Environment

While there is no single way to effectively implement inclusive design in the built environment, the USGBC’s LEED green building rating system does outline a few key strategies in its Inclusive Design pilot credit .

Inclusive Design Process

During the early planning stages for the new Winthrop Library, Johnston Architects worked with the Friends of Winthrop Library to collect hundreds of comments, suggestions, and concerns from the community. Photo by Benjamin Drummond

One of the most effective ways of implementing inclusive design in any project is to involve the target community or future occupants in the pre-planning and planning stages from the start. In this manner inclusive design becomes a participatory affair, one that requires listening to the wants, needs, and concerns of those who’ll actually be using the space. Gail Shillingford, principal of planning and landscape at B+H Architects, expands on this notion.

“It’s about telling our stories,” Shillingford told gb&d in a previous interview . “I’ve had the pleasure of working with many Indigenous people throughout my career, and one of the things many of them have strongly believed in is that the only way you can create an inclusive environment is to engage and to listen to others’ stories so you can gain an understanding. Without that we are designing for clients, or our egos, but not people.”

Physical Access

LEED also emphasizes the need for maximizing the physical accessibility of a space, encouraging architects to go beyond Federal, state, and local regulatory requirements for both exterior and interior accessibility.

Exterior inclusive design features that help promote physical access include:

- Open sight lines to and from entries as well as public access points

- Easily accessible bike racks, drinking fountains, and assistance animal areas

- Routes, walkways, and paths that are at least 43 inches in width

- Resting areas that include seating options of different heights

- Ramps and curb cuts

- Tactile pavement

Interiors, on the other hand, can be made more accessible by:

- Installing lit screens and monitors with no-glare surfaces

- Equipping elevators with clearly-identifiable, manual features to delay door closing

- Increasing the size of turning spaces to at least 72 inches in diameter

- Providing circulation paths that are at least 20% wider than required

- Installing 36-inch wide doors at minimum, in all occupied spaces

The stainless steel roof of this airport forms stretch over column-free structures to create dramatic, expansive interior spaces that form a rationalized programmatic layout of passenger circulation and amenities in order to improve wayfinding and level of service. Photo by Nick Merrick

Of course, it’s not enough for a space to just be accessible. Visitors must also be able to navigate a space, regardless of their physical, cognitive, or language ability. For that reason adding a variety of easily-understood wayfinding features is integral to the creation of an inclusive built environment.

Possible wayfinding features include:

- Audio and tactile maps to guide blind/low-vision people

- Continuous linear path indicators

- Color blocking and patterns to identify key public access spaces

- Directional signage that use symbols or other non-text diagrams, Braille, and active audio/visual signaling on dynamic signs

Assistive Technology

To ensure that a building’s intended functions can be used by all visitors, it may be necessary to include assistive technology, or technology that is designed to maintain, increase, or otherwise improve functionality for children, the elderly, those with disabilities, or neurodiverse persons. Some of the more common examples of assistive technology include height-adjustable desks and counters, touch-screen or voice operated controls, handles and doorknobs that do not require grasping or twisting, assistive keyboards, magnifiers, eye tracking, and more.

Emotional Health

RiverSouth in Austin features a green roof that both keeps the building cool and gives people a place to escape. Photo by Casey Dunn

As global rates of depression, anxiety, and other mental health conditions continue to rise, it’s important for buildings to positively impact the psyche and nurture occupants’ emotional health. This facet of inclusive design is heavily linked to biophilic design —or design that fosters a connection between people and the natural world—as features like plants, views of nature, natural sunlight, running water, passive ventilation , and nature-inspired art are all known to help improve mood and reduce feelings of stress.

Inclusive Spaces

Another hallmark of inclusive design in the built environment is the addition of spaces designed with a certain demographic or demographics in mind. Some examples of inclusive spaces—like quiet/meditation/prayer rooms and public restrooms—have become relatively commonplace in recent years, whereas spaces like lactation rooms for new mothers, all-gender restrooms, and accessible fitness areas are still considered novel additions.

Employee Training

Lastly, LEED stresses the importance of providing inclusive design training for all building operations and management employees or developing an operations and management guidebook that is applicable to all visitors and occupants. Suggested topics include:

- Guidance for welcoming visitors/customers and working with staff with sensory, accessibility, or cognitive challenges

- List of Federal and state/local protected classes

- Nondiscrimination policies and procedures

- Overview of any and all applicable laws, codes, and organizational non-discrimination/labor equality policies

3 Examples of Inclusive Design in Architecture

Now that we’ve a better understanding of inclusive design and its principles, let’s take a look at a few architectural projects that have consciously incorporated inclusivity into their designs.

1. Schoenecker Center for STEAM Education, St. Paul, MN

The new Schoenecker Center for STEAM Education at the University of St. Thomas was designed by BWBR in collaboration with Robert A.M. Stern Architects (RAMSA) with inclusivity as one of its guiding principles. Rendering courtesy of BWBR and RAMSA

Designed by BWBR in collaboration with Robert A.M. Stern Architects for the University of St. Thomas, the Schoenecker Center for STEAM Education is a masterclass in how inclusive design may be implemented in higher education settings.

During the early phases of the planning process, BWBR—with help from the university’s office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion—met with stakeholder focus groups composed of students, alumni, and other members of the university community to field ideas and discuss potential points of concern for the new building. Using the information gathered during these meetings and the LEED Inclusive Design pilot credits, the team set out to design a space that was welcoming and representative of all.

“To accomplish this we prioritized creating inclusive spaces like all-gender restrooms, lactation rooms, public education areas, and spaces that encourage frequent, casual interaction to reduce the probability of social isolation,” Stephanie McDaniel, president and CEO of BWBR, told gb&d in a previous interview . “We also incorporated assistive technology like accessible height service counters and height adjustable furniture, as well as wayfinding tools like non-text diagrams, braille, and patterns and color-blocking to identify key public spaces.”

Encompassing 130,000 square feet, the completed Schoenecker Center for STEAM Education includes flexible and collaborative workspaces; a two-story engineering bay; labs for biology, chemistry, physics, and robotics; a music rehearsal space; art gallery, atrium, cafeteria, and emerging media program complete with studios and newsrooms.

2. Winthrop Public Library, Winthrop, WA

Johnston Architects and Prentiss Balance Wickline Architects involved the community in the planning stages of the Winthrop Public Library to ensure it was representative of their needs. Photo by Benjamin Drummond

Having long been underserved by a small library with poor access to essential services and multimedia resources, Winthrop—a small town in the heart of Washington’s Methow Valley—was in dire need of a library capable of meeting the community’s education, entertainment, and general enrichment needs.

With help from Prentiss Balance Wickline Architects and Friends of the Winthrop Library, Johnston Architects was able to come up with a solution. Hundreds of comments and requests were collected as a part of the firm’s Hopes & Dreams charrette process and used to design a library that fulfilled the community’s goals and addressed those aspects that simply weren’t working.

“We designed the building with an open floor plan to be flexible and continuously adapt its space layout to the evolving needs for programmed activity,” Harmony Cooper, former project architect at Johnston Architects, told gb&d in a previous interview . “Spaces range from intimate reading window seats and quiet study areas to more active teen and children’s areas, flexible meeting halls that can be subdivided, a main stack space where larger events can also happen, and a maker space that is fit for 3D printing and digital fabrication.”

The completed Winthrop Public Library is capable of holding a collection of more than 20,000 materials and houses a large community room available after hours for events, meetings, and other programming.

3. Bergami Center, West Haven, CT

Stakeholder groups consisting of deans, professors, administration faculty, and other university representatives were consulted during the early planning stages of the Bergami Center. Photo by Peter Aaron/OTTO

When the University of New Haven (UNH) concluded in 2018 that a new academic building was needed to support campus growth, they weren’t entirely sure what kind of building would be most beneficial—so UNH, with the help of New Haven-based architectural firm Svigals + Partners, turned to the university’s stakeholder community for ideas.

“We had a stakeholder group composed of the deans of each of the schools, professors, administration, the design team—a little bit of everyone from campus,” Katelyn Chapin, associate at Svigals + Partners, told gb&d in a previous interview . “We brainstormed what types of spaces would be required for their campus. Being a community-oriented person, this was my favorite part of the process.”

The end result was the Bergami Center for Science, Technology, and Innovation, an interdisciplinary hub dedicated to learning, co-creation, and the betterment of society. Intended as a space where students of all majors could come to learn, create, and collaborate, the Bergami Center encompasses science classrooms, technology-supported “smart” classrooms, multimedia production studios, a makerspace, as well as an atrium and café.

From a sustainability standpoint the center features copious daylighting strategies, low-flow fixtures, high-efficiency boilers and chillers, on-demand controlled ventilation, exterior sun shades, and was partially constructed from recycled materials—all of which helped it earn LEED Gold certification .

is a freelance journalist based in the Raleigh area. They specialize in writing articles on sustainable design, architecture, and the long-term effects of our built environment.

The leading information source for sustainability professionals.

- gb&dPRO

- Manage Subscriptions

- gb&dPRO Membership

- Newsletters

- Browse the Archives

- About gb&d

- Advertise with Us

- Submissions

- Terms & Use

Download Your Free PDF

Looking for a professional for your next built environment project.

- How Can We Design A More Inclusive World? Perspectives From Architecture And International Relations

How can we design a more inclusive world? Perspectives from architecture and international relations

- Open access

- Published: 16 May 2024

Promoting equality, diversity and inclusion in research and funding: reflections from a digital manufacturing research network

- Oliver J. Fisher 1 ,

- Debra Fearnshaw ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6498-9888 2 ,

- Nicholas J. Watson 3 ,

- Peter Green 4 ,

- Fiona Charnley 5 ,

- Duncan McFarlane 6 &

- Sarah Sharples 2

Research Integrity and Peer Review volume 9 , Article number: 5 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

411 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Equal, diverse, and inclusive teams lead to higher productivity, creativity, and greater problem-solving ability resulting in more impactful research. However, there is a gap between equality, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) research and practices to create an inclusive research culture. Research networks are vital to the research ecosystem, creating valuable opportunities for researchers to develop their partnerships with both academics and industrialists, progress their careers, and enable new areas of scientific discovery. A feature of a network is the provision of funding to support feasibility studies – an opportunity to develop new concepts or ideas, as well as to ‘fail fast’ in a supportive environment. The work of networks can address inequalities through equitable allocation of funding and proactive consideration of inclusion in all of their activities.

This study proposes a strategy to embed EDI within research network activities and funding review processes. This paper evaluates 21 planned mitigations introduced to address known inequalities within research events and how funding is awarded. EDI data were collected from researchers engaging in a digital manufacturing network activities and funding calls to measure the impact of the proposed method.

Quantitative analysis indicates that the network’s approach was successful in creating a more ethnically diverse network, engaging with early career researchers, and supporting researchers with care responsibilities. However, more work is required to create a gender balance across the network activities and ensure the representation of academics who declare a disability. Preliminary findings suggest the network’s anonymous funding review process has helped address inequalities in funding award rates for women and those with care responsibilities, more data are required to validate these observations and understand the impact of different interventions individually and in combination.

Conclusions

In summary, this study offers compelling evidence regarding the efficacy of a research network's approach in advancing EDI within research and funding. The network hopes that these findings will inform broader efforts to promote EDI in research and funding and that researchers, funders, and other stakeholders will be encouraged to adopt evidence-based strategies for advancing this important goal.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Achieving equality, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) is an underpinning contributor to human rights, civilisation and society-wide responsibility [ 1 ]. Furthermore, promoting and embedding EDI within research environments is essential to make the advancements required to meet today’s research challenges [ 2 ]. This is evidenced by equal, diverse and inclusive teams leading to higher productivity, creativity and greater problem-solving ability [ 3 ], which increases the scientific impact of research outputs and researchers [ 4 ]. However, there remains a gap between EDI research and the everyday implementation of inclusive practices to achieve change [ 5 ]. This paper presents and reflects on the EDI measures trialled by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) funded digital manufacturing research network, Connected Everything (grant number: EP/S036113/1) [ 6 ]. The EPSRC is a UK research council that funds engineering and physical sciences research. By sharing these reflections, this work aims to contribute to the wider effort of creating an inclusive research culture. The perceptions of equality, diversity, and inclusion may vary among individuals. For the scope of this study, the following definitions are adopted:

Equality: Equality is about ensuring that every individual has an equal opportunity to make the most of their lives and talents. No one should have poorer life chances because of the way they were born, where they come from, what they believe, or whether they have a disability.

Diversity: Diversity concerns understanding that each individual is unique, recognising our differences, and exploring these differences in a safe, positive, and nurturing way to value each other as individuals.

Inclusion: Inclusion is an effort and practice in which groups or individuals with different backgrounds are culturally and socially accepted, welcomed and treated equally. This concerns treating each person as an individual, making them feel valued, and supported and being respectful of who they are.

Research networks have varied goals, but a common purpose is to create new interdisciplinary research communities, by fostering interactions between researchers and appropriate scientific, technological and industrial groups. These networks aim to offer valuable career progression opportunities for researchers, through access to research funding, forming academic and industrial collaborations at network events, personal and professional development, and research dissemination. However, feedback from a 2021 survey of 19 UK research networks, suggests that these research networks are not always diverse, and whilst on the face of it they seem inclusive, they are perceived as less inclusive by minority groups (including non-males, those with disabilities, and ethnic minority respondents) [ 7 ]. The exclusivity of these networks further exacerbates the inequality within the academic community as it prevents certain groups from being able to engage with all aspects of network activities.

Research investigating the causes of inequality and exclusivity has identified several suggestions to make research culture more inclusive, including improving diverse representation within event programmes and panels [ 8 , 9 ]; ensuring events are accessible to all [ 10 ]; providing personalised resources and training to build capacity and increase engagement [ 11 ]; educating institutions and funders to understand and address the barriers to research [ 12 ]; and increasing diversity in peer review and funding panels [ 13 ]. Universities, research institutions and research funding bodies are increasingly taking responsibility to ensure the health of the research and innovation system and to foster inclusion. For example, the EPSRC has set out their own ‘Expectation for EDI’ to promote the formation of a diverse and inclusive research culture [ 14 ]. To drive change, there is an emphasis on the importance of measuring diversity and links to measured outcomes to benchmark future studies on how interventions affect diversity [ 5 ]. Further, collecting and sharing EDI data can also drive aspirations, provide a target for actions, and allow institutions to consider common issues. However, there is a lack of available data regarding the impact of EDI practices on diversity that presents an obstacle, impeding the realisation of these benefits and hampering progress in addressing common issues and fostering diversity and inclusion [ 5 ].

Funding acquisition is important to an academic’s career progression, yet funding may often be awarded in ways that feel unequal and/or non-transparent. The importance of funding in academic career progression means that, if credit for obtaining funding is not recognised appropriately, careers can be damaged, and, as a result of the lack of recognition for those who have been involved in successful research, funding bodies may not have a complete picture of the research community, and are unable to deliver the best value for money [ 15 ]. Awarding funding is often a key research network activity and an area where networks can have a positive impact on the wider research community. It is therefore important that practices are established to embed EDI consideration within the funding process and to ensure that network funding is awarded without bias. Recommendations from the literature to make the funding award process fairer include: ensuring a diverse funding panel; funders instituting reviewer anti-bias training; anonymous review; and/or automatic adjustments to correct for known biases [ 16 ]. In the UK, the government organisation UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), tasked with overseeing research and innovation funding, has pledged to publish data to enhance transparency. This initiative aims to furnish an evidence base for designing interventions and evaluating their efficacy. While the data show some positive signs (e.g., the award rates for male and female PI applicants were equal at 29% in 2020–21), Ottoline Leyser (UKRI Chief Executive) highlights the ‘persistent pernicious disparities for under-represented groups in applying for and winning research funding’ [ 17 ]. This suggests that a more radical approach to rethinking the traditional funding review process may be required.

This paper describes the approach taken by the ‘Connected Everything’ EPSRC-funded Network to embed EDI in all aspects of its research funding process, and evaluates the impact of this ambition, leading to recommendations for embedding EDI in research funding allocation.

Connected everything’s equality diversity and inclusion strategy

Connected Everything aims to create a multidisciplinary community of researchers and industrialists to address key challenges associated with the future of digital manufacturing. The network is managed by an investigator team who are responsible for the strategic planning and, working with the network manager, to oversee the delivery of key activities. The network was first funded between 2016–2019 (grant number: EP/P001246/1) and was awarded a second grant (grant number: EP/S036113/1). The network activities are based around three goals: building partnerships, developing leadership and accelerating impact.

The Connected Everything network represents a broad range of disciplines, including manufacturing, computer science, cybersecurity, engineering, human factors, business, sociology, innovation and design. Some of the subject areas, such as Computer Science and Engineering, tend to be male-dominated (e.g., in 2021/22, a total of 185,42 higher education student enrolments in engineering & technology subjects was broken down as 20.5% Female and 79.5% Male [ 18 ]). The networks also face challenges in terms of accessibility for people with care responsibilities and disabilities. In 2019, Connected Everything committed to embedding EDI in all its network activities and published a guiding principle and goals for improving EDI (see Additional file 1 ). When designing the processes to deliver the second iteration of Connected Everything, the team identified several sources of potential bias/exclusion which have the potential to impact engagement with the network. Based on these identified factors, a series of mitigation interventions were implemented and are outlined in Table 1 .

Connected everything anonymous review process

A key Connected Everything activity is the funding of feasibility studies to enable cross-disciplinary, foresight, speculative and risky early-stage research, with a focus on low technology-readiness levels. Awards are made via a short, written application followed by a pitch to a multidisciplinary diverse panel including representatives from industry. Six- to twelve-month-long projects are funded to a maximum value of £60,000.

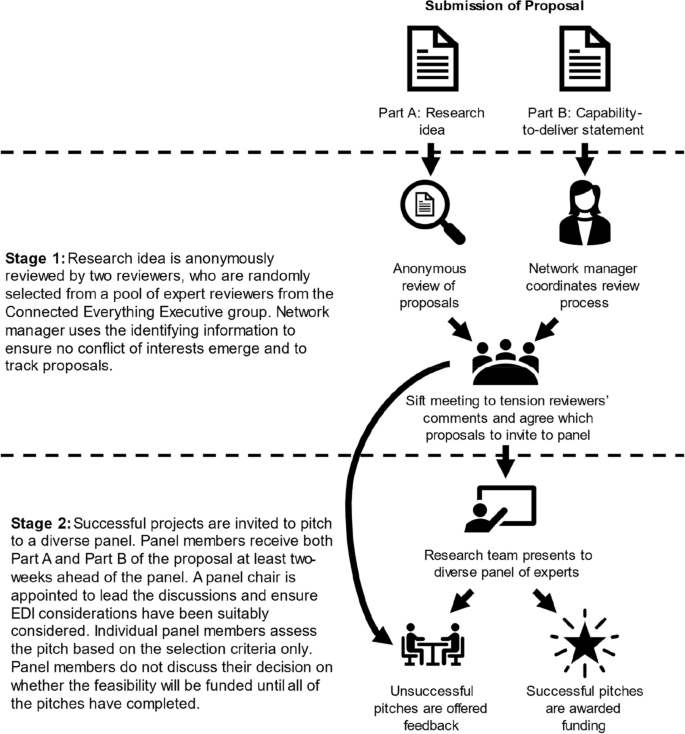

The current peer-review process used by funders may reveal the applicants’ identities to the reviewer. This can introduce dilemmas to the reviewer regarding (a) deciding whether to rely exclusively on information present within the application or search for additional information about the applicants and (b) whether or not to account for institutional prestige [ 34 ]. Knowing an applicant’s identity can bias the assessment of the proposal, but by focusing the assessment on the science rather than the researcher, equality is more frequently achieved between award rates (i.e., the proportion of successful applications) [ 15 ]. To progress Connected Everything’s commitment to EDI, the project team created a 2-stage review process, where the applicants’ identity was kept anonymous during the peer review stage. This anonymous process, which is outlined in Fig. 1 , was created for the feasibility study funding calls in 2019 and used for subsequent funding calls.

Connected Everything’s anonymous review process [EDI: Equality, diversity, and inclusion]

To facilitate the anonymous review process, the proposal was submitted in two parts: part A the research idea and part B the capability-to-deliver statement. All proposals were first anonymously reviewed by a random selection of two members from the Connected Everything executive group, which is a diverse group of digital manufacturing experts and peers from academia, industry and research institutions that provide guidance and leadership on Connected Everything activities. The reviewers rated the proposals against the selection criteria (see Additional file 1 , Table 1) and provided overall comments alongside a recommendation on whether or not the applicant should be invited to the panel pitch. This information was summarised and shared with a moderation sift panel, made up of a minimum of two Connected Everything investigators and a minimum of one member of the executive group, that tensioned the reviewers’ comments (i.e. comments and evaluations provided by the peer reviewers are carefully considered and weighed against each other) and ultimately decided which proposals to invite to the panel. This tension process included using the identifying information to ensure the applicants did have the capability to deliver the project. If this remained unclear, the applicants were asked to confirm expertise in an area the moderation sift panel thought was key or asked to bring in additional expertise to the project team during the panel pitch.

During stage two the applicants were invited to pitch their research idea to a panel of experts who were selected to reflect the diversity of the community. The proposals, including applicants’ identities, were shared with the panel at least two weeks ahead of the panel. Individual panel members completed a summary sheet at the end of the pitch session to record how well the proposal met the selection criteria (see Additional file 1 , Table 1). Panel members did not discuss their funding decision until all the pitches had been completed. A panel chair oversaw the process but did not declare their opinion on a specific feasibility study unless the panel could not agree on an outcome. The panel and panel chair were reminded to consider ways to manage their unconscious bias during the selection process.

Due to the positive response received regarding the anonymous review process, Connected Everything extended its use when reviewing other funded activities. As these awards were for smaller grant values (~ £5,000), it was decided that no panel pitch was required, and the researcher’s identity was kept anonymous for the entire process.

Data collection and analysis methods

Data collection.

Equality, diversity and inclusion data were voluntarily collected from applicants for Connected Everything research funding and from participants who won scholarships to attend Connected Everything funded activities. Responses to the EDI data requests were collected from nine Connected Everything coordinated activities between 2019 and 2022. Data requests were sent after the applicant had applied for Connected Everything funding or had attended a Connected Everything funded activity. All data requests were completed voluntarily, with reassurance given that completion of the data requested in no way affected their application. In total 260 responses were received, of which the three feasibility study calls comprised 56.2% of the total responses received. Overall, there was a 73.8% response rate.

To understand the diversity of participants engaging with Connected Everything activities and funding, the data requests asked for details of specific diversity characteristics: gender, transgender, disability, ethnicity, age, and care responsibilities. Although sex and gender are terms that are often used interchangeably, they are two different concepts. To clarify, the definitions used by the UK government describe sex as a set of biological attributes that is generally limited to male or female, and typically attributed to individuals at birth. In contrast, gender identity is a social construction related to behaviours and attributes, and is self-determined based on a person’s internal perception, identification and experience. Transgender is a term used to describe people whose gender identity is not the same as the sex they were registered at birth. Respondents were first asked to identify their gender and then whether their gender was different from their birth sex.

For this study, respondents were asked to (voluntarily) self-declare whether they consider themselves to be disabled or not. Ethnicity within the data requests was based on the 2011 census classification system. When reporting ethnicity data, this study followed the AdvanceHE example to aggregate the census categories into six groups to enable benchmarking against the available academic ethnicity data. AdvanceHE is a UK charity that works to improve the higher education system for staff, students and society. However, it was acknowledged that there were limitations with this grouping, including the assumption that minority ethnic staff or students are a homogenous group [ 16 ]. Therefore, this study made sure to breakdown these groups during the discussion of the results. The six groups are:

Asian: Asian/Asian British: Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and any other Asian background;

Black: Black/African/Caribbean/Black British: African, Caribbean, and any other Black/African/Caribbean background;

Other ethnic backgrounds, including Arab.

White: all white ethnic groups.

Benchmarking data

Published data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency [ 26 ] (a UK organisation responsible for collecting, analysing, and disseminating data related to higher education institutions and students), UKRI funding data [ 19 , 35 ] and 2011 census data [ 36 ] were used to benchmark the EDI data collected within this study. The responses to the data collected were compared to the engineering and technology cluster of academic disciplines, as this is most represented by Connected Everything’s main funded EPSRC. The Higher Education Statistics Agency defines the engineering and technology cluster as including the following subject areas: general engineering; chemical engineering; mineral, metallurgy & materials engineering; civil engineering; electrical, electronic & computer engineering; mechanical, aero & production engineering and; IT, systems sciences & computer software engineering [ 37 ].

When assessing the equality in funding award rates, previous studies have focused on analysing the success rates of only the principal investigators [ 15 , 16 , 38 ]; however, Connected Everything recognised that writing research proposals is a collaborative task, so requested diversity data from the whole research team. The average of the last six years of published principal investigator and co-investigator diversity data for UKRI and EPSRC funding awards (2015–2021) was used to benchmark the Connected Everything funding data [ 35 ]. The UKRI and EPSRC funding review process includes a peer review stage followed by panel pitch and assessment stage; however, the applicant's track record is assessed during the peer review stage, unlike the Connected Everything review process.

The data collected have been used to evaluate the success of the planned migrations to address EDI factors affecting the higher education research ecosystem, as outlined in Table 1 (" Connected Everything’s Equality Diversity and Inclusion Strategy " Section).

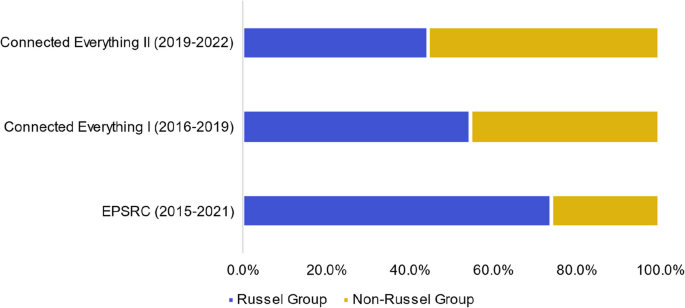

Dominance of small number of research-intensive universities receiving funding from network

The dominance of a small number of research-intensive universities receiving funding from a network can have implications for the field of research, including: the unequal distribution of resources; a lack of diversity of research, limited collaboration opportunities; and impact on innovation and progress. Analysis of published EPSRC funding data between 2015 and 2021 [ 19 ], shows that the funding has been predominately (74.1%, 95% CI [71.%, 76.9%] out of £3.98 billion) awarded to Russell Group universities. The Russell Group is a self-selected association of 24 research-intensive universities (out of the 174 universities) in the UK, established in 1994. Evaluation of the universities that received Connected Everything feasibility study funding between 2016–2019, shows that Connected Everything awarded just over half (54.6%, 95% CI [25.1%, 84.0%] out of 11 awards) to Russell Group universities. Figure 2 shows that the Connected Everything funding awarded to Russell Group universities reduced to 44.4%, 95% CI [12.0%, 76.9%] of 9 awards between 2019–2022.

A comparison of funding awarded by EPSRC (total = £3.98 billion) across Russell Group universities and non-Russell Group universities, alongside the allocations for Connected Everything I (total = £660 k) and Connected Everything II (total = £540 k)

Dominance of successful applications from men

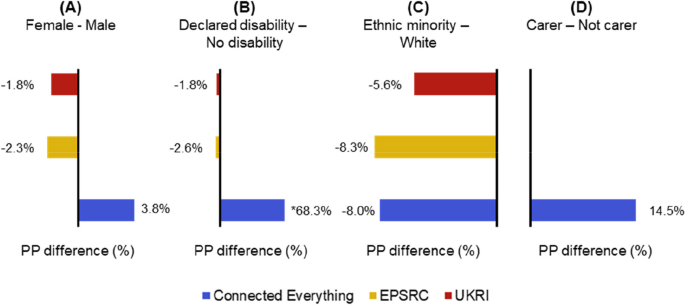

The percentage point difference between the award rates of researchers who identified as female, those who declare a disability, or identified as ethnic minority applicants and carers and their respective counterparts have been plotted in Fig. 3 . Bars to the right of the axis mean that the award rate of the female/declared-disability/ethnic-minority/carer applicants is greater than that of male/non- disability/white/not carer applicants.

Percentage point (PP) differences in award rate by funding provider for gender, disability status, ethnicity and care responsibilities (data not collected by UKRI and EPSRC [ 35 ]). The total number of applicants for each funder are as follows: Connected Everything = 146, EPSRC = 37,960, and UKRI = 140,135. *The numbers of applicants were too small (< 5) to enable a meaningful discussion

Figure 3 (A) shows that between 2015 and 2021 research team applicants who identified as male had a higher award rate than those who identified as female when applying for EPSRC and wider UKRI research council funding. Connected Everything funding applicants who identified as female achieved a higher award rate (19.4%, 95% CI [6.5%, 32.4%] out of 146) compared to male applicants (15.6%, 95% CI [8.8%, 22.4%] out of 146). These data suggest that biases have been reduced by the Connected Everything review process and other mitigation strategies (e.g., visible gender diversity in panel pitch members and publishing CE principal and goals to demonstrate commitment to equality and fairness). This finding aligns with an earlier study that found gender bias during the peer review process, resulting in female investigators receiving less favourable evaluations than their male counterparts [ 15 ].

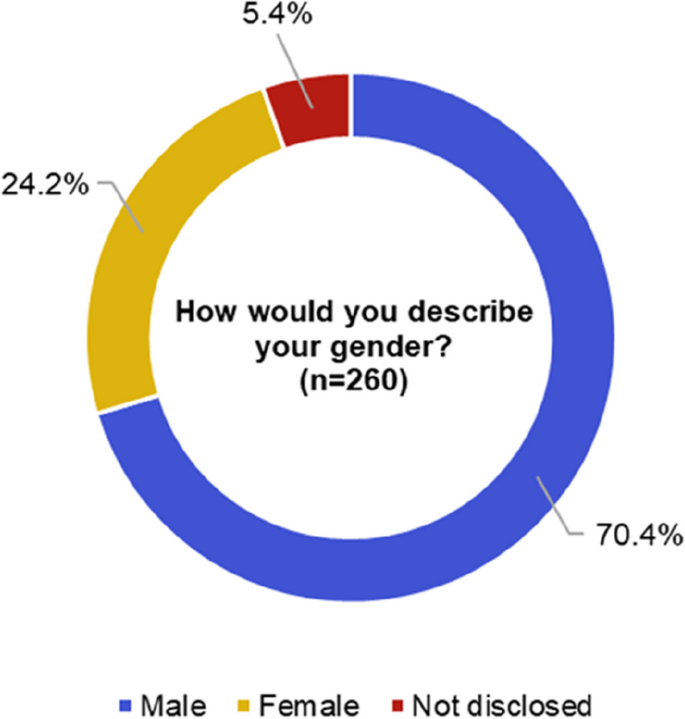

Over-representation of people identifying as male in engineering and technology academic community

Figure 4 shows the response to the gender question, with 24.2%, 95% CI [19.0%, 29.4%] of 260 responses identifying as female. This aligns with the average for the engineering and technology cluster (21.4%, 95% CI [20.9%, 21.9%] female of 27,740 academic staff), which includes subject areas representative of our main funder, EPSRC [ 22 ]. We also sought to understand the representation of transgender researchers within the network. However, following the rounding policy outlined by UK Government statistics policies and procedures [ 39 ], the number of responses that identified as a different sex to birth was too low (< 5) to enable a meaningful discussion.

Gender question responses from a total of 260 respondents

Dominance of successful applications from white academics

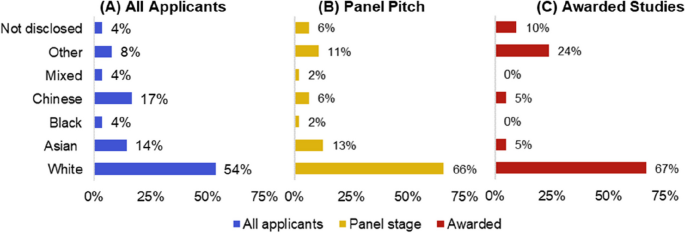

Figure 3 (C) shows that researchers with a minority ethnicity consistently have a lower award rate than white researchers when applying for EPSRC and UKRI funding. Similarly, the results in Fig. 3 (C) indicate that white researchers are more successful (8.0% percentage point, 95% CI [-8.6%, 24.6%]) when applying for Connected Everything funding. These results indicate that more measures should be implemented to support the ethnic minority researchers applying for Connected Everything funding, as well as sense checking there is no unconscious bias in any of the Connected Everything funding processes. The breakdown of the ethnicity diversity of applicants at different stages of the Connected Everything review process (i.e. all applications, applicants invited to panel pitch and awarded feasibility studies) has been plotted in Fig. 5 to help identify where more support is needed. Figure 5 shows an increase in the proportion of white researchers from 54%, 95% CI [45.4%, 61.8%] of all 146 applicants to 66%, 95% CI [52.8%, 79.1%] of the 50 researchers invited to the panel pitch. This suggests that stage 1 of the Connected Everything review process (anonymous review of written applications) may favour white applicants and/or introduce unconscious bias into the process.

Ethnicity questions responses from different stages during the Connected Everything anonymous review process. The total number of applicants is 146, with 50 at the panel stage and 23 ultimately awarded

Under-representation of those from black or minority ethnic backgrounds

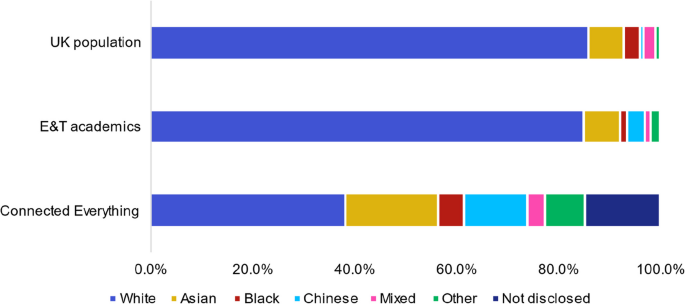

Connected Everything appears to have a wide range of ethnic diversity, as shown in Fig. 6 . The ethnicities Asian (18.3%, 95% CI [13.6%, 23.0%]), Black (5.1%, 95% CI [2.4%, 7.7%]), Chinese (12.5%, 95% CI [8.4%, 16.5%]), mixed (3.5%, 95% CI [1.3%, 5.7%]) and other (7.8%, 95% CI [4.5%, 11.1%]) have a higher representation among the 260 individuals engaging with network’s activities, in contrast to both the engineering and technology academic community and the wider UK population. When separating these groups into the original ethnic diversity answers, it becomes apparent that there is no engagement with ‘Black or Black British: Caribbean’, ‘Mixed: White and Black Caribbean’ or ‘Mixed: White and Asian’ researchers within Connected Everything activities. The lack of engagement with researchers from a Caribbean heritage is systemic of a lack of representation within the UK research landscape [ 25 ].

Ethnicity question responses from a total of 260 respondents compared to distribution of the 13,085 UK engineering and technology (E&T) academic staff [ 22 ] and 56 million people recorded in the UK 2011 census data [ 36 ]

Under-representation of disabilities, chronic conditions, invisible illnesses and neurodiversity in funded activities and events.

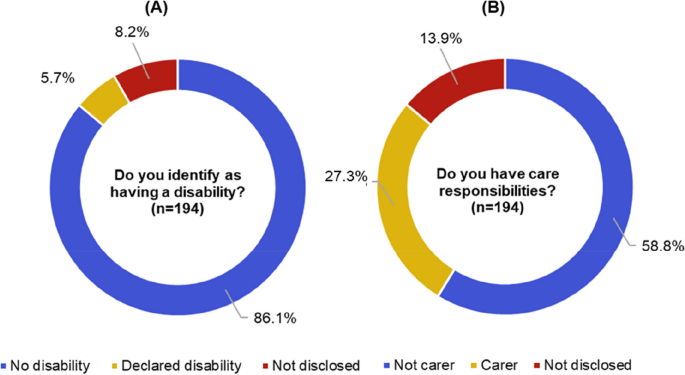

Figure 7 (A) shows that 5.7%, 95% CI [2.4%, 8.9%] of 194 responses declared a disability. This is higher than the average of engineering and technology academics that identify as disabled (3.4%, 95% CI [3.2%, 3.7%] of 27,730 academics). Between Jan-March 2022, 9.0 million people of working age (16–64) within the UK were identified as disabled by the Office for National Statistics [ 40 ], which is 21% of the working age population [ 27 ]. Considering these statistics, there is a stark under-representation of disabilities, chronic conditions, invisible illnesses and neurodiversity amongst engineering and technology academic staff and those engaging in Connected Everything activities.

Responses to A Disability and B Care responsibilities questions colected from a total of 194 respondents

Between 2015 and 2020 academics that declared a disability have been less successful than academics without a disability in attracting UKRI and EPSRC funding, as shown in Fig. 3 (B). While Fig. 3 (B) shows that those who declare a disability have a higher Connected Everything funding award rate, the number of applicants who declared a disability was too small (< 5) to enable a meaningful discussion regarding this result.

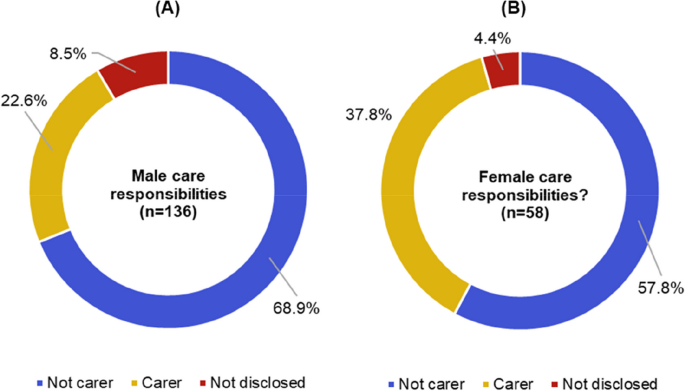

Under-representation of those with care responsibilities in funded activities and events

In response to the care responsibilities question, Fig. 7 (B) shows that 27.3%, 95% CI [21.1%, 33.6%] of 194 respondents identified as carers, which is higher than the 6% of adults estimated to be providing informal care across the UK in a UK Government survey of the 2020/2021 financial year [ 41 ]. However, the ‘informal care’ definition used by the 2021 survey includes unpaid care to a friend or family member needing support, perhaps due to illness, older age, disability, a mental health condition or addiction [ 41 ]. The Connected Everything survey included care responsibilities across the spectrum of care that includes partners, children, other relatives, pets, friends and kin. It is important to consider a wide spectrum of care responsibilities, as key academic events, such as conferences, have previously been demonstrably exclusionary sites for academics with care responsibilities [ 42 ]. Breakdown analysis of the responses to care responsibilities by gender in Fig. 8 reveals that 37.8%, 95% CI [25.3%, 50.3%] of 58 women respondents reported care responsibilities, compared to 22.6%, 95% CI [61.1%, 76.7%] of 136 men respondents. Our findings reinforce similar studies that conclude the burden of care falls disproportionately on female academics [ 43 ].

Responses to care responsibilities when grouped by A 136 males and B 58 females

Figure 3 (D) shows that researchers with careering responsibilities applying for Connected Everything funding have a higher award rate than those researchers applying without care responsibilities. These results suggest that the Connected Everything review process is supportive of researchers with care responsibilities, who have faced barriers in other areas of academia.

Reduced opportunities for ECRs

Early-career researchers (ECRs) represent the transition stage between starting a PhD and senior academic positions. EPSRC defines an ECR as someone who is either within eight years of their PhD award, or equivalent professional training or within six years of their first academic appointment [ 44 ]. These periods exclude any career break, for example, due to family care; health reasons; and reasons related to COVID-19 such as home schooling or increased teaching load. The median age for starting a PhD in the UK is 24 to 25, while PhDs usually last between three and four years [ 45 ]. Therefore, these data would imply that the EPSRC median age of ECRs is between 27 and 37 years. It should be noted, however, that this definition is not ideal and excludes ECRs who may have started their research career later in life.

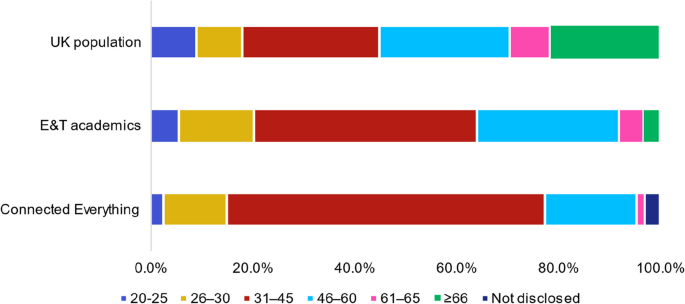

Connected Everything aims to support ECRs via measures that include mentoring support, workshops, summer schools and podcasts. Figure 9 shows a greater representation of researchers engaging with Connected Everything activities that are aged between 30–44 (62.4%, 95% CI [55.6%, 69.2%] of 194 respondents) when compared to the wider engineering and technology academic community (43.7%, 95% CI [43.1%, 44.3%] of 27,780 academics) and UK population (26.9%, 95% CI [26.9%, 26.9%]).

Age question responses from a total of 194 respondents compared to distribution of the 27,780 UK engineering and technology (E&T) academic staff [ 22 ] and 56 million people recorded in the UK 2011 census data [ 36 ]

High competition for funding has a greater impact on ECRs

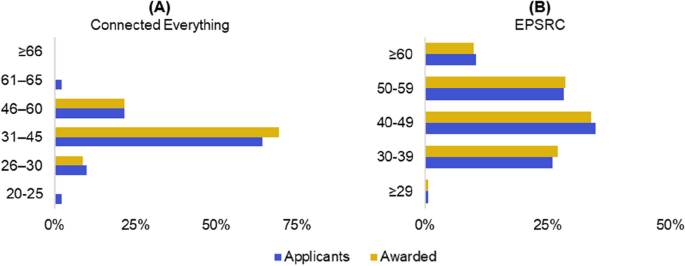

Figure 10 shows that the largest age bracket applying for and winning Connected Everything funding is 31–45, whereas 72%, CI 95% [70.1%, 74.5%] of 12,075 researchers awarded EPSRC grants between 2015 and 2021 were 40 years or older. These results suggest that measures introduced by Connected Everything has been successful at providing funding opportunities for researchers who are likely to be early-mid career stage.

Age of researchers at applicant and awarded funding stages for A Connected Everything between 2019–2022 (total of 146 applicants and 23 awarded) and B EPSRC funding between 2015–2021 [ 35 ] (total of 35,780 applicants and 12,075 awarded)

The results of this paper provide insights into the impact that Connected Everything’s planned mitigations have had on promoting equality, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) in research and funding. Collecting EDI data from individuals who engage with network activities and apply for research funding enabled an evaluation of whether these mitigations have been successful in achieving the intended outcomes outlined at the start of the study, as summarised in Table 2 .

The results in Table 2 indicate that Connected Everything’s approach to EDI has helped achieve the intended outcome to improve representation of women, ECRs, those with a declared disability and black/minority ethnic backgrounds engaging with network events when compared to the engineering and technology academic community. In addition, the network has helped raise awareness of the high presence of researchers with care responsibilities at network events, which can help to track progress towards making future events inclusive and accessible towards these carers. The data highlights two areas for improvement: (1) ensuring a gender balance; and (2) increasing representation of those with declared disabilities. Both these discrepancies are indicative of the wider imbalances and underrepresentation of these groups in the engineering and technology academic community [ 26 ], yet represent areas where networks can strive to make a difference. Possible strategies include: using targeted outreach; promoting greater representation of these groups in event speakers; and going further to create a welcoming and inclusive environment. One barrier that can disproportionately affect women researchers is the need to balance care responsibilities with attending network events [ 46 ]. This was reflected in the Connected Everything data that reported 37.8%, 95% CI [25.3%, 50.3%] of women engaging with network activities had care responsibilities, compared to 22.6%, 95% CI [61.1%, 76.7%] of men. Providing accommodations such as on-site childcare, flexible scheduling, or virtual attendance options can therefore help to promote inclusivity and allow more women researchers to attend.