The video essay boom

Hour-long YouTube videos are thriving in the TikTok era. Their popularity reflects our desire for more nuanced content online.

by Terry Nguyen

The video essay’s reintroduction into my adult life was, like many things, a side effect of the pandemic. On days when I couldn’t bring myself to read recreationally, I tried to unwind after work by watching hours and hours of YouTube.

My pseudo-intellectual superego, however, soon became dissatisfied with the brain-numbing monotony of “day in the life” vlogs, old Bon Appétit test kitchen videos, and makeup tutorials. I wanted content that was entertaining, but simultaneously informational, thoughtful, and analytical. In short, I wanted something that gave the impression that I, the passive viewer, was smart. Enter: the video essay.

Video essays have been around for about a decade, if not more, on YouTube. There is some debate over how the form preceded the platform; some film scholars believe the video essay was born out of and remains heavily influenced by essay films , a type of nonfiction filmmaking. Regardless, YouTube has become the undisputed home of the contemporary video essay. Since 2012, when the platform began to prioritize watch-time over views , the genre flourished. These videos became a significant part of the 2010s YouTube landscape, and were popularized by creators across film, politics, and academic subcultures.

Today, there are video essays devoted to virtually any topic you can think of, ranging anywhere from about 10 minutes to upward of an hour. The video essay has been a means to entertain fan theories , explore the lore of a video game or a historical deep dive , explain or critique a social media trend , or like most written essays, expound upon an argument, hypothesis , or curiosity proposed by the creator.

Some of the best-known video essay creators — Lindsay Ellis, Natalie Wynn of ContraPoints, and Abigail Thorn of PhilosophyTube — are often associated with BreadTube , an umbrella term for a group of left-leaning, long-form YouTubers who provide intellectualized commentary on political and cultural topics.

It’s not an exaggeration to claim that I — and many of my fellow Gen Zers — were raised on video essays, academically and intellectually. They were helpful resources for late-night cramming sessions (thanks Crash Course), and responsible for introducing a generation to first-person commentary on all sorts of cultural and political phenomena. Now, the kids who grew up on this content are producing their own.

“Video essays are a form that has lent itself particularly well to pop culture because of its analytical nature,” Madeline Buxton, the culture and trends manager at YouTube, told me. “We are starting to see more creators using video essays to comment on growing trends across social media. They’re serving as sort of real-time internet historians by helping viewers understand not just what is a trend, but the larger cultural context of something.”

A lot has been said about the video essay and its ever-shifting parameters . What does seem newly relevant is how the video essay is becoming repackaged, as long-form video creators find a home on platforms besides YouTube. This has played out concurrently with the pandemic-era shift toward short-form video, with Instagram, Snapchat, and YouTube respectively launching Reels, Spotlight, and Shorts to compete against TikTok.

TikTok’s sudden, unwavering rise has proven the viability of bite-size content, and the app’s addictive nature has spawned fears about young people’s dwindling attention spans. Yet, the prevailing popularity of video essays, from new and old creators alike, suggests otherwise. Audiences have not been deterred from watching lengthy videos, nor has the short-form pivot significantly affected creators and their output. Emerging video essayists aren’t shying away from length or nuance, even while using TikTok or Reels as a supplement to grow their online following.

One can even argue that we are witnessing the video essay’s golden era . Run times are longer than ever, while more and more creators are producing long-form videos. The growth of “creator economy” crowdfunding tools, especially during the pandemic, has allowed video essayists to take longer breaks between uploads while retaining their production quality.

“I do feel some pressure to make my videos longer because my audience continues to ask for it,” said Tiffany Ferguson, a YouTube creator specializing in media criticism and pop culture commentary. “I’ve seen comments, both on my own videos and those I watch, where fans are like, ‘Yes, you’re feeding us,’ when it comes to longer videos, especially the hour to two-hour ones. In a way, the mentality seems to be: The longer the better.”

In a Medium post last April, the blogger A. Khaled remarked that viewers were “willing to indulge user-generated content that is as long as a multi-million dollar cinematic production by a major Hollywood studio” — a notion that seemed improbable just a few years ago, even to the most popular video essayists. To creators, this hunger for well-edited, long-form video is unprecedented and uniquely suitable for pandemic times.

The internet might’ve changed what we pay attention to, but it hasn’t entirely shortened our attention span, argued Jessica Maddox, an assistant professor of digital media technology at the University of Alabama. “It has made us more selective about the things we want to devote our attention to,” she told me. “People are willing to devote time to content they find interesting.”

“People are willing to devote time to content they find interesting”

Every viewer is different, of course. I find that my attention starts to wane around the 20-minute mark if I’m actively watching and doing nothing else — although I will admit to once spending a non-consecutive four hours on an epic Twin Peaks explainer . Last month, the channel Folding Ideas published a two-hour video essay on “the problem with NFTs,” which has garnered more than 6 million views so far.

Hour-plus-long videos can be hits, depending on the creator, the subject matter, the production quality, and the audience base that the content attracts. There will always be an early drop-off point with some viewers, according to Ferguson, who make it about two to five minutes into a video essay. Those numbers don’t often concern her; she trusts that her devoted subscribers will be interested enough to stick around.

“About half of my viewers watch up to the halfway point, and a smaller group finishes the entire video,” Ferguson said. “It’s just how YouTube is. If your video is longer than two minutes, I think you’re going to see that drop-off regardless if it’s for a video that’s 15 or 60 minutes long.”

Some video essayists have experimented with shorter content as a topic testing ground for longer videos or as a discovery tool to reach new audiences, whether it be on the same platform (like Shorts) or an entirely different one (like TikTok).

“Short-form video can expose people to topics or types of content they’re not super familiar with yet,” Maddox said. “Shorts are almost like a sampling of what you can get with long-form content.” The growth of Shorts, according to Buxton of YouTube, has given rise to this class of “hybrid creators,” who alternate between short- and long-form content. They can also be a starting point for new creators, who are not yet comfortable with scripting a 30-minute video.

Queline Meadows, a student in Ithaca College’s screen cultures program, became interested in how young people were using TikTok to casually talk about film, using editing techniques that borrowed heavily from video essays. She created her own YouTube video essay titled “The Rise of Film TikTok” to analyze the phenomenon, and produces both TikTok micro-essays and lengthy videos.

“I think people have a desire to understand things more deeply,” Meadows told me. “Even with TikTok, I find it hard to unfold an argument or explore multiple angles of a subject. Once people get tired of the hot takes, they want to sit with something that’s more nuanced and in-depth.”

It’s common for TikTokers to tease a multi-part video to gain followers. Many have attempted to direct viewers to their YouTube channel and other platforms for longer content. On the contrary, it’s in TikTok’s best interests to retain creators — and therefore viewers — on the app. In late February, TikTok announced plans to extend its maximum video length from three minutes to 10 minutes , more than tripling a video’s run-time possibility. This decision arrived months after TikTok’s move last July to start offering three-minute videos .

As TikTok inches into YouTube-length territory, Spotify, too, has introduced video on its platform, while YouTube has similarly signaled an interest in podcasting . In October, Spotify began introducing “video podcasts,” which allows listeners (or rather, viewers) to watch episodes. Users have the option to toggle between actively watching a podcast or traditionally listening to one.

What’s interesting about the video podcast is how Spotify is positioning it as an interchangeable, if not more intimate, alternative to a pure audio podcast. The video essay, then, appears to occupy a middle ground between podcast and traditional video by making use of these key elements. For creators, the boundaries are no longer so easy to define.

“Some video essay subcultures are more visual than others, while others are less so,” said Ferguson, who was approached by Spotify to upload her YouTube video essays onto the platform last year. “I was already in the process of trying to upload just the audio of my old videos since that’s more convenient for people to listen to and save on their podcast app. My reasoning has always been to make my content more accessible.”

To Ferguson, podcasts are a natural byproduct of the video essay. Many viewers are already consuming lengthy videos as ambient entertainment, as content to passively listen to while doing other tasks. The video essay is not a static format, and its development is heavily shaped by platforms, which play a crucial role in algorithmically determining how such content is received and promoted. Some of these changes are reflective of cultural shifts, too.

Maddox, who researches digital culture and media, has a theory that social media discourse is becoming less reactionary. She described it as a “simmering down” of the hot take, which is often associated with cancel culture . These days, more creators are approaching controversy from a removed, secondhand standpoint; they seem less interested in engendering drama for clicks. “People are still providing their opinions, but in conjunction with deep analysis,” Maddox said. “I think it says a lot about the state of the world and what holds people’s attention.”

That’s the power of the video essay. Its basic premise — whether the video is a mini-explainer or explores a 40-minute hypothesis — requires the creator to, at the very least, do their research. This often leads to personal disclaimers and summaries of alternative opinions or perspectives, which is very different from the more self-centered “reaction videos” and “story time” clickbait side of YouTube.

“The things I’m talking about are bigger than me. I recognize the limitations of my own experience,” Ferguson said. “Once I started talking about intersections of race, gender, sexuality — so many experiences that were different from my own — I couldn’t just share my own narrow, straight, white woman perspective. I have to provide context.”

This doesn’t change the solipsistic nature of the internet, but it is a positive gear shift, at least in the realm of social media discourse, that makes being chronically online a little less soul-crushing. The video essay, in a way, encourages us to engage in good faith with ideas that we might not typically entertain or think of ourselves. Video essays can’t solve the many problems of the internet (or the world, for that matter), but they can certainly make learning about them a little more bearable.

Most Popular

10 big things we think will happen in the next 10 years, this changed everything, take a mental break with the newest vox crossword, israel is not fighting for its survival, how the self-care industry made us so lonely, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Money

This changed everything

The last 10 years, explained

This article is OpenAI training data

What’s really happening to grocery prices right now

The NCAA’s proposal to pay college athletes is fair. That's the problem.

Global health is the world’s best investment

Republicans want to put pigs back in tiny cages. Again.

Trump wants the Supreme Court to toss out his conviction. Will they?

Why North Korea dumped trash on South Korea

8 surprising reasons to stop hating cicadas and start worshipping them

Is a ceasefire in Gaza actually close?

Follow Polygon online:

- Follow Polygon on Facebook

- Follow Polygon on Youtube

- Follow Polygon on Instagram

Site search

- Dragon’s Dogma 2

- Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom

- Baldur’s Gate 3

- Summer Game Fest schedule

- PlayStation

- Dungeons & Dragons

- Magic: The Gathering

- Board Games

- All Tabletop

- All Entertainment

- What to Watch

- What to Play

- Buyer’s Guides

- Really Bad Chess

- All Puzzles

Filed under:

The best video essays of 2022

10 videos that will entertain you and make you feel smarter. What’s not to like?

If you buy something from a Polygon link, Vox Media may earn a commission. See our ethics statement .

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: The best video essays of 2022

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/71803290/BFV_RevealScreenshot_10.0.jpg)

An educational and argumentative style has exploded in popularity across video platforms over the past few years, part of the broader wave of explainer-based content in social media. It’s gotten to the point where the form now constitutes an extremely wide tent covering an incredibly deep well of works — or, in the parlance of one subgenre, a gargantuan iceberg . We now see everything from wordless editing experiments to vlogs with occasional image wallpapering called “video essays.” (It’s gotten to the point where one of my favorite videos released last year waded into these definitional weeds, to thought-provoking results.)

This growth makes rounding up a mere 10 exemplary videos a bigger challenge each year. My guiding principles when formulating this list were not just depth of insight, originality, and diversity of subject matter and creators, but also trying to find video essays that truly make the most of both parts of that name — which demand visual attention and engagement. The essays are listed in order of release date.

Climate Fictions, Dystopias and Human Futures by Julia Leyda and Kathleen Loock

As the prognosis around global warming gets more urgent, pop culture has been taking notice, and “cli-fi” has emerged as its own storytelling genre. Leyd and Loock use the recent Don’t Look Up as a starting point, questioning what role — if any — films like these can hope to have in affecting actual activism and reform on climate change. How strong is the connection between art’s power to move us and tangible action?

Captain Ahab: The Story of Dave Stieb by Secret Base

No one is making documentary content quite like Jon Bois, Alex Rubenstein, and the rest of the crew at Dorktown. Bois is an artist who paints with data points and historical detritus, editing all this material together in a way that feels more forward-thinking than almost anyone else making films today — whether for the internet, television, or theaters. An epic four-part series on Dave Stieb, an also-also-also-ran of baseball history, sounds ridiculous. And yet Dorktown turns him into one of the most compelling characters of the year.

[ Ed. note: Secret Base is part of SB Nation, which along with Polygon is part of Vox Media. This played no part in including the video.]

Deconstructing the Bridge by Total Refusal

This is perhaps the least “essay-like” video on this list. It’s more of a university-level lecture, but set in the least academic forum imaginable: a session of Battlefield 5. Such unusual ventures are the modus operandi of Total Refusal , a “pseudo-Marxist media guerrilla” which has used The Division to explain urban design , Red Dead Redemption 2 to explain class , and much more. Within the Battlefield 5 map is a re-creation of Dutch city of Nijmegen, the site of a decisive battle during World War II. Total Refusal takes viewers on a survey of the area in a virtual form, and in the process they delve not just into the history involved but also the entire concept of war tourism and re-creations, questioning how culture remembers these events.

Why Panzer Dragoon Saga Is the Greatest RPG Nobody Played by Michael Saba

If this doesn’t send the 1998 Sega Saturn game Panzer Dragoon Saga to the top of your must-play list, then I don’t know what to tell you. More than an intriguing look at a game that was incredibly ahead of its time and took years to find its audience, this video is a treatise on a pressing issue within gaming. See, if you want to play Panzer Dragoon Saga , you will almost certainly have to pirate it, which might stir ethical qualms in some. Saba mounts an impassioned defense of piracy as a form of archival practice and game preservation. Even if you disagree with such a conclusion, the problems he highlights within the industry cannot be denied.

Nice White Teachers, Bad Brown Schools: Hollywood’s Pedagogy on Urban Education by Yhara Zayd

Yhara Zayd makes her third consecutive appearance on our annual video essay list, and for good reason. Not content to retread ground covered by other pop culture video creators, she finds both novel subjects and interesting lenses on them. Here she scrutinizes the “inspirational” story trope of well-intentioned white teachers making a difference in urban environments, seen in the likes of Dangerous Minds and The Ron Clark Story . Most incisively, she contrasts the conventions of this genre with the stark realities and lived history of actual outsider intervention in nonwhite education.

Intimate Thresholds by Desiree Garcia

Less than four minutes long, this essay is nonetheless entrancing, thanks to Garcia’s continually inventive editing. Instead of a drawn-out exploration of the theme of female artistic competition in film, she contrasts two examples through visceral juxtaposition: 1940’s Dance, Girl, Dance and 2010’s Black Swan. With split screens, hazy picture-in-picture, precise cuts, and some remarkable use of captions, the essay makes its ideas intuitively felt rather than explaining itself through lecture.

Instagram Hates Its Users by Jarvis Johnson

The long story made short is that Instagram has continually sabotaged any actual enjoyment of using its app through trying to imitate whatever new trend has come down the cultural pipeline. But the long story, as relayed by Johnson, is so much more entertaining. We often forget the direct relationship between interface design and user experience, but this is a terrific deep dive into how that process works, pinned to an easy-to-grasp timeline of Instagram’s calamitous history.

Fixing My Brain With Automated Therapy by Jacob Geller

Jacob Geller is exceptionally good at drawing in a web of disparate sources to discuss ideas you might not have even thought about before. Here, the story of “ the first chat bot ,” the 2019 visual novel Eliza, and the app-based 2021 game UnearthU are used to explore the use of artificial intelligence in modern therapy. But as the title suggests, Geller goes one step further, testing out several different therapy apps that purport to help you improve your mental health without the need of any human therapists. His results, and what they suggest about the true intention behind these apps and the way therapy is incorporated into contemporary society, are… well, disquieting.

Parking lots are everywhere and nowhere by What’s So Great About That?

The concept of “liminal space” is currently popular in online culture discourse. But Grace Lee seldom tackles a topic from the same angle as everyone else. With reference points as wide-ranging as Seinfeld, Joni Mitchell’s “Big Yellow Taxi,” and the work of artist Guillaume Lachapelle, she discusses how parking lots appear in media, and in a wider view how they and similar urban-industrial spaces figure into our everyday lives. Lee’s essays demand your attention like few others; look away and you’re liable to miss a great little visual gag. Because of this, despite her videos seldom going longer than 15-20 minutes, they often pack in much, much more information than you’ll expect.

How Degrowth Can Save the World by Andrewism

Andrew Sage describes himself not just as an anarchist but as “solarpunk” — focused on solutions for a sustainable future for humanity. In this video he elucidates one of the key features of the destructive capitalist status quo: the idea of unlimited economic and industrial growth. Insistence of “degrowth” practices can often elicit fears of some vague loss in one’s standard of living. But Sage debunks this and many other arguments against degrowth, while building a more inspiring and hopeful vision for an environmentally sound, egalitarian existence.

Next Up In What to Watch

The next level of puzzles.

Take a break from your day by playing a puzzle or two! We’ve got SpellTower, Typeshift, crosswords, and more.

Sign up for the newsletter Patch Notes

A weekly roundup of the best things from Polygon

Just one more thing!

Please check your email to find a confirmation email, and follow the steps to confirm your humanity.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Can Makuhita be shiny in Pokémon Go?

Watch one YouTuber’s joyride in a Cold War F-4 Phantom turn Top Gun into a buddy comedy

Where to unlock all extreme trials in FFXIV

The next Pokémon TCG expansion of 2024, Shrouded Fates, is now available to pre-order

The Acolyte, Clipped, and more new TV this week

Pre-orders for the Cyberpunk: Edgerunners Mission Kit are now open

Another Word

From the writing center at the university of wisconsin-madison.

#essayhack: What TikTok can Teach Writing Centers about Student Perceptions of College Writing

By Holly Berkowitz, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga

There is a widespread perception that TikTok, the popular video-sharing social media platform, is primarily a tool of distraction where one mindlessly scrolls through bite-sized bits of content. However, due to the viewer’s ability to engage with short-form video content, it is undeniable that TikTok is also a platform from which users gain information; whether this means following a viral dance tutorial or learning how to fold a fitted sheet, TikTok houses millions of videos that serve as instructional tutorials that provides tips or how-tos for its over one billion active users.

That TikTok might be considered a learning tool also has implications for educational contexts. Recent research has revealed that watching or even creating TikToks in classrooms can aid learning objectives, particularly relating to language acquisition or narrative writing skills. In this post, I discuss the conventions of and consequences for TikToks that discuss college writing. Because of the popularity of videos that spotlight “how-tos” or “day in the life” style content, looking at essay or college writing TikTok can be a helpful tool for understanding some larger trends and student perceptions of writing. Due to the instructional nature of TikToks and the ways that students might be using the app for advice, these videos can be viewed as parallel or ancillary to the advice that a Writing Center tutor might provide.

A search for common hashtags including the words “essay,” “college writing,” or “essay writing hack” yields hundreds of videos that pertain to writing at the college level. Although there is a large variety in content due to the sheer amount of content, this post focuses on two genres of videos as they represent a large portion of what is shared: first, videos that provide tips or how-tos for certain AI tools or assignment genres and second, videos that invite the viewer to accompany the creator as they write a paper under a deadline. Shared themes include attempts to establish peer connections and comfort viewers who procrastinate while writing, a focus on writing speed and concrete deliverables (page count, word limit, or hours to write), and an emphasis on digital tools or AI software (especially that which is marked as “not cheating”). Not only does a closer examination into these videos help us meet writers where they are more precisely, but it also draws writing center workers’ attention to lesser known digital tools or “hacks” that students are using for their assignments.

“How to write” Videos

Videos in the “how to” style are instructional and advice-dispensing in tone. Often, the creator utilizes a digital writing aid or provides a set of writing tips or steps to follow. Whether these videos spotlight assistive technologies that use AI, helpful websites, or suggestions for specific forms of writing, they often position writing as a roadblock or adversary. Videos of this nature attempt to reach viewers by promising to make writing easier, more approachable, or just faster when working under a tight deadline; they almost always assume the writer in question has left their writing task to the last possible moment. It’s not surprising then that the most widely shared examples of this form of content are videos with titles like “How to speed-write long papers” or “How to make any essay longer” (this one has 32 million views). It is evident that this type of content attempts to target students who suffer from writing-related anxiety or who tend to procrastinate while writing.

Sharing “hacks” online is a common practice that manifests in many corners of TikTok where content creators demonstrate an easier or more efficient way of achieving a task (such as loading a dishwasher) or obtaining a result (such as finding affordable airline tickets). The same principle applies to #essay TikTok, where writing advice is often framed as a “hack” for writing faster papers, longer papers, or papers more likely to result in an A. This content uses a familiar titling convention: How to write X (where X might be a specific genre like a literature review, or just an amount of pages or words); How to write X in X amount of time; and How to write X using this software or AI program. The amount of time is always tantalizingly brief, as two examples—“How to write a 5 page essay in 2 mins” and “How to write an essay in five minutes!! NO PLAGIARISM!!”—attest to. While some of these are silly or no longer useful methods of getting around assignment parameters, they introduce viewers to helpful research and writing aids and sometimes even spotlight Writing Center best practices. For instance, a video by creator @kaylacp called “Research Paper Hack” shows viewers how to use a program called PowerNotes to organize and code sources; a video by @patches has almost seven million views and demonstrates using an AI bot to both grade her paper and provide substantive feedback. Taken as a whole, this subsect of TikTok underscores that there is a ready audience for content that purports to assist writers in meeting the deliverables of a writing assignment using a path of least resistance.

Similarly, TikTok contains myriad videos that position the creator as a sort of expert in college writing and dispense tips for improving academic writing and style. These videos are often created by upperclassmen who claim to frequently receive As on essays and tend to use persuasive language in the style of an infomercial, such as “How to write a college paper like a pro,” “How to write research papers more efficiently in 5 easy steps!” or “College students, if you’re not using this feature, you’re wasting your time.” The focus in these videos is even more explicit than those mentioned above, as college students are addressed in the titles and captions directly. This is significant because it prompts users to engage with this content as they might with a Writing Center tutor or tutoring more generally. These videos are sites where students are learning how to write more efficiently but also learning how their college peers view and treat the writing process.

The “how to write” videos share several common themes, most prevalent of which is an emphasis on concrete deliverables—you will be able to produce this many pages in this many minutes. They also share a tendency to introduce or spotlight different digital tools and assistive technologies that make writing more expedient; although several videos reference or demonstrate how to use ChatGPT or OpenAI, most creators attempt to show viewers less widely discussed platforms and programs. As parallel forms of writing instruction, these how-tos tend to focus on quantity over quality and writing-as-product. However, they also showcase ways that AI can be helpful and generative for writers at all stages. Most notably they direct our attention to the fact that student writers consistently encounter writing- and essay- related content while scrolling TikTok.

Write “with me” Videos

Just as the how-to style videos target writers who view writing negatively and may have a habit of procrastinating writing assignments, write “with me” videos invite the viewer to join the creator as they work. These videos almost always include a variation of the phrase— “Write a 5- page case analysis w/ me” or “pull an all nighter with me while I write a 10- page essay.” One of the functions of this convention is to establish a peer-to-peer connection with the viewer, as they are brought along while the creator writes, experiences writer’s block, takes breaks, but ultimately completes their assignment in time. Similarly to the videos discussed above, these “with me” videos also center on writing under a deadline and thus emphasize the more concrete deliverables of their assignments. As such, the writing process is often made less visible in favor of frequent cuts and timestamps that show the progression toward a page or word count goal.

One of the most common effects of “with me” videos is to assure the viewer that procrastinating writing is part and parcel of the college experience. As the content creators grapple with and accept their own writing anxieties or deferring habits, they demonstrate for the viewer that it is possible to be both someone who struggles with writing and someone who can make progress on their papers. In this way, these videos suggest to students that they are not alone in their experiences; not only do other college students feel overwhelmed with writing or leave their papers until the day before they are due, but you can join a fellow student as they tackle the essay writing process. One popular video by @mercuryskid with over 6 million views follows them working on a 6000 word essay for which they have received several extensions, and although they don’t finish by the end of the video, their openness about the struggles they experience while writing may explain its appeal.

Indeed, in several videos of this kind the creator centers their procrastination as a means of inviting the viewer in; often the video will include the word in the title, such as “write 2 essays due at 11:59 tonight with me because I am a chronic procrastinator” or “write the literature essay i procrastinated with me.” Because of this, establishing a peer connection with the hypothetical viewer is paramount; @itskamazing’s video in which she writes a five page paper in three hours ends with her telling the viewer, “If you’re in college, you’re doing great. Let’s just knock this semester out.” One video titled “Writing essays doesn’t need to be stressful” shows a college-aged creator explaining what tactics she uses for outlining and annotating research to make sure she feels prepared when she begins to write in earnest. Throughout, she directly hails the viewer as “you” and attempts to cultivate a sense of familiarity with the person on the other side of the screen; in some moments her advice feels like listening in on a one-sided Writing Center session.

A second aspect of these “with me” videos is an intense focus on the specifics of a writing task. The titles of these videos usually follow a formula that invites the viewer with the writer as they write X amount in X time, paralleling the structure of how-to-write videos. The emphasis here, due to the last-minute nature of the writing contexts, is always on speed: “write a 2000- word essay with me in 4.5 hours” or “Join me as I write a 10- page essay that is due at 11:59pm.” Since these videos often need to cover large swaths of time during which the creator is working, there are several jumps forward in time, sped up footage, and text stamps or zoom-ins that update the viewer on how many pages or words the writer has completed since the last update. Overall, this brand of content demonstrates how product-focused writers become when large amounts of writing are completed in a single setting. However, it also makes this experience seem more manageable to viewers, as we frequently see writers in videos take naps and breaks during these high-stakes writing sessions. Furthermore, although the writers complain and appear stressed throughout, these videos tend to close with the writer submitting their papers and celebrating their achievement.

Although these videos may send mixed messages to college students using TikTok who experience struggles with writing productivity, they can be helpful for viewers as they demonstrate the shared nature of these struggles and concerns. Despite the overarching emphasis on the finished product, the documentary-style of this content shows how writing can be a fraught process. For tutors or those removed from the experience of being in college, these videos also illuminate some of the reasons students procrastinate writing; we see creators juggling part-time jobs, other due dates, and family obligations. This genre of TikToks shows the power that social media platforms have due to the way they can amplify the shared experience of students.

To conclude, I gesture toward a few of the takeaways that #essay and #collegewriting TikTok might provide for those who work in Writing Centers, especially those who frequently encounter students who struggle with procrastination. First, because TikTok is a video-sharing platform, the content often shows a mixture of writing process and product. Despite a heavy emphasis in these videos on the finished product that a writer turns in to be graded, several videos necessarily also reveal the steps that go into writing, even marathon sessions the night before a paper is due. We primarily see forward progress but we also see false starts and deletions; we mostly see the writer once they have completed pre-writing tasks but we also see analyzing a prompt, outlining, and brainstorming. Additionally, this genre of TikTok is instructive in that it shows how often students wait until before a paper is due to begin and just how many writers are working solely to meet a deadline or deliverable. While as Writing Center workers we cannot do much to shift this mindset, we can make a more considerable effort to focus on time management and executive functioning skills in our sessions. Separating the essay writing process into manageable chunks or steps appears to be a skill that college students are already seeking to develop independently when they engage on social media, and Writing Centers are equipped to help students refine these habits. Finally, it is worth considering the potential for university Writing Center TikTok accounts. A brief survey of videos created by Writing Center staff reveals that they draw on similar themes and tend to emphasize product and deliverables—for example, a video titled “a passing essay grade” that shows someone going into the center and receiving an A+ on a paper. Instead, these accounts could create a space for Writing Centers to actively contribute to the discourse on college writing that currently occupies the app and create content that parallels a specific Writing Center or campus’s values.

Holly Berkowitz is the Coordinator of the Writing and Communication Center at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. She recently received her PhD from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where she also worked at the UW-Madison Writing Center. Although she does not post her own content, she is an avid consumer of TikTok videos.

Why this Harvard-bound Brockton student's college admissions essay went viral on TikTok

BROCKTON — Abigail Mack lost her mother, Julie, to cancer when she was just 12 years old.

The Cardinal Spellman High School valedictorian used that experience to write her college admissions essay, which went viral on TikTok for her heartfelt words. It also got her into her dream school, Harvard University.

Mack, a Bridgewater resident, wrote about the challenges she faced growing up with one parent and living in a world constructed for two-parent families.

"I hate the letter 'S,'" Mack started her essay. "Of the 164,777 words with 'S,' I only grapple with one. To condemn an entire letter because of its use 0.0006 percent of the time sounds statistically absurd, but that one case changed 100 percent of my life.

"I used to have two parents, but now I have one, and the 'S' in parents isn't going anywhere. 'S' follows me. I can't get through a day without being reminded that while my friends went out to dinner with their parents, I ate with my parent. As I write this essay, there is a blue line under the word 'parent,' telling me to check my grammar; even Grammarly assumes that I should have parents, but cancer doesn't listen to edit suggestions."

Mack read the introduction to her Common App essay in a May 3 TikTok video . The initial video has been viewed 17 million times as of Thursday. It has been "liked" 4.7 million times.

"I see why you got in," one TikTok commenter wrote.

"WOW," another user wrote.

Mack went on to share additional parts of her essay in a four-part video series.

The 18-year-old said she tried to abandon "S, " because the world wouldn't. Mack tried to stay busy because "you can't have dinner with your 'parent' (thanks again Grammarly) if you're too busy to have family dinner."

Mack filled all her spare time and said she became known as the "busy kid." She played volleyball, took dance classes, participated in theater and did other after-school activities. Mack said certain themes — academics, theater and politics — kept coming up in her life and she found her rhythm and embraced it .

"I stopped running away from a single 'S' and began chasing a double 'S' — paSSion," Mack wrote. "Passion has given me purpose. I was shackled to 'S' as I tried to escape the confines of the traditional familial structure."

Mack was also accepted into other prestigious colleges, including Dartmouth College, Georgetown University and the University of Notre Dame.

Her viral TikTok video has now gained national attention, with a trending BuzzFeed story about her essay reaching more than 725,000 views as of Thursday morning.

"Despite all obstacles, Abigail has found incredible success at Cardinal Spellman High School and outside of it as well on the stage in Boston Theater and even as part of the re-election campaign for Senator Ed Markey," Cardinal Spellman said in a statement. "She continues to excel in sports and academics here at Spellman, earning the title of Valedictorian for the class of 2021. Her recent success and acceptance into Harvard comes as no surprise to her friends, family and Cardinal Spellman mentors!"

Mack's father, Jonathan, continues to run Julie's Studio of Dance in West Bridgewater, which Julie Mack opened just months before her death at the age of 39 in 2014 . Julie Mack had battled cancer since she was 14 years old.

Mack will enter Harvard in the fall as an undecided major, but she's considering pursuing a focus in foreign policy.

Enterprise senior reporter Cody Shepard can be reached by email at [email protected] . You can follow him on Twitter at @cshepard_ENT . Support local journalism by purchasing a digital or print subscription to The Enterprise today.

How to find the best video essays

Haya kaylani curates video essay recommendations in her newsletter “the deep dive.”.

Embedded is your essential guide to what’s good on the internet, written by Kate Lindsay and edited by Nick Catucci.

Can you tell I’m starting to think about making video essays? — Kate

How to find the newsletter that will tell you about newsletters finding video essays:

Take one quick look at what’s trending on YouTube, and you can easily lose faith in humanity. As I write this, it’s all Grimace shakes and people either giving or spending thousands of dollars for different viral stunts.

But underneath all that, a genre of creators is playing a long game. Video essays might seem totally incompatible with today’s internet of fast short-form content and flashy clickbait. But inexplicably, hours-long videos on topics ranging from modern femininity to the history of Disney’s FastPass system consistently receive millions of views. The genre is becoming so popular that people like Haya Kaylani have emerged to help viewers sort through it.

Kidology’s video essays will renew your faith in social media

Kaylani writes The Deep Dive , a newsletter in which she curates five video essay recommendations every week, although I discovered her on TikTok , where her videos highlighting recent stand-out essays have received millions of views of their own.

Kaylani worked in the PR industry for six years, but after she lost her job in a round of layoffs, she was inspired to try something new. She had been a longtime consumer of video essays, but no one in her IRL friend group was interested in them.

“They weren't anything that I could talk about with my friends or the people in my life,” she says over Zoom. “But every time I would watch these videos, I noticed that they would have hundreds of thousands of views, if not millions. So it was this feeling of like, ‘Okay, they're out there. People are watching these.’”

The Deep Dive has since gained over 6,500 subscribers since it launched in February of this year, and another nearly 57,000 follow it on TikTok. In this interview for paid subscribers, Kaylani and I talk about the video essay explosion, how TikTok is (ironically) boosting long-form content, and where people should get started if they, too, want to become video essay obsessives.

What’s the appeal of a video essay versus a written essay?

This post is for paid subscribers

We’re in a Golden Era of Video Essays and That Is Awesome

Exclusive content curated for Create: All things pre-production to post. See trends and topics like this and more come to life at NAB Show in Las Vegas. Explore the latest tools and advanced workflows elevating the art of storytelling.

READ MORE: The video essay boom (Vox)

Video essays are thriving in the TikTok era, even while platforms like YouTube are pivoting to promote short-form content. According to Vox , their popularity reflects our desire for more nuanced content online.

Video essays have been around for a decade or more on YouTube. Since 2012, when the platform began to prioritize watch-time over views , the genre has flourished.

READ MORE: YouTube search, now optimized for time watched (YouTube)

Today, there are video essays devoted to virtually any topic you can think of, ranging anywhere from about 10 minutes to upward of an hour.

“Video essays are a form that has lent itself particularly well to pop culture because of its analytical nature,” Madeline Buxton, the culture and trends manager at YouTube, tells Vox . “We’re starting to see more creators using video essays to comment on growing trends across social media. They’re serving as sort of real-time internet historians by helping viewers understand not just what is a trend, but the larger cultural context of something.”

To Vox writer Terry Nguyen , what seems especially relevant is how the video essay is becoming repackaged, as long-form video creators find a home on platforms besides YouTube. This has played out concurrently with the pandemic-era shift toward short-form video, with Instagram, Snapchat, and YouTube respectively launching Reels, Spotlight, and Shorts to compete against TikTok.

Yet audiences have not been deterred from watching lengthy videos on TikTok either. Emerging video essayists aren’t shying away from length or nuance, even while using TikTok or Reels as a supplement to grow their online following, Nguyen finds.

She points to the growth of “creator economy” crowdfunding tools , especially during the pandemic, that have allowed video essayists to take longer breaks between uploads while retaining their production quality.

READ MORE: Virtual tips are helping content creators actually make money (Vox)

CRUSHING IT IN THE CREATOR ECONOMY:

The cultural impact a creator has is already surpassing that of traditional media, but there’s still a stark imbalance of power between proprietary platforms and the creators who use them. Discover what it takes to stay ahead of the game with these fresh insights hand-picked from the NAB Amplify archives:

- The Developer’s Role in Building the Creator Economy Is More Important Than You Think

- How Social Platforms Are Attempting to Co-Opt the Creator Economy

- Now There’s a Creator Economy for Enterprise

- The Creator Economy Is in Crisis. Now Let’s Fix It. | Source: Li Jin

- Is the Creator Economy Really a Democratic Utopia Realized?

YouTube creator Tiffany Ferguson admits to feeling some pressure from audiences to make her videos longer.

“I’ve seen comments, both on my own videos and those I watch, where fans are like, ‘Yes, you’re feeding us,’ when it comes to longer videos, especially the hour to two-hour ones. In a way, the mentality seems to be: The longer the better.”

In a Medium post, “ We Live in the Golden Age of Video Essays ,” blogger A. Khaled remarked that viewers were “willing to indulge user-generated content that is as long as a multi-million dollar cinematic production by a major Hollywood studio” — a notion that seemed improbable just a few years ago, even to the most popular video essayists. To creators, this hunger for well-edited, long-form video is unprecedented and uniquely suited to pandemic times.

READ MORE: We Live in the Golden Age of Video Essays (Medium)

Last month, the YouTube channel Folding Ideas published a two-hour video essay on “ the problem with NFTs ,” which has garnered more than 6.4 million views to date.

Hour-plus-long videos can be hits, depending on the creator, the subject matter, the production quality, and the audience base that the content attracts. There will always be an early drop-off point with some viewers, who make it roughly two to five minutes into a video essay.

“About half of my viewers watch up to the halfway point, and a smaller group finishes the entire video,” Ferguson said. “It’s just how YouTube is. If your video is longer than two minutes, I think you’re going to see that drop-off regardless if it’s for a video that’s 15 or 60 minutes long.”

Some video essayists have experimented with shorter content as a topic testing ground for longer videos or as a discovery tool to reach new audiences, whether it be on the same platform (like Shorts) or an entirely different one (like TikTok).

“The video essay is not a static format, and its development is heavily shaped by platforms, which play a crucial role in algorithmically determining how such content is received and promoted. Some of these changes are reflective of cultural shifts, too.”

The growth of shorts, according to Buxton, has given rise to this class of “hybrid creators,” who alternate between short- and long-form content. They can also be a starting point for new creators, who are not yet comfortable with scripting a 30-minute video.

“It’s common for TikTokers to tease a multi-part video to gain followers,” Nguyen reports. “Many have attempted to direct viewers to their YouTube channel and other platforms for longer content. On the contrary, it’s in TikTok’s best interests to retain creators — and therefore viewers — on the app.”

In late February, TikTok announced plans to extend its maximum video length from three minutes to 10 minutes, more than tripling a video’s run-time possibility.

READ MORE: TikTok expands maximum video length to 10 minutes (The Verge)

Last October, Spotify introduced “ video podcasts ,” which allows users the option of toggling between actively watching a podcast or traditionally listening to one.

READ MORE: Introducing Video Podcasts on Spotify (Spotify)

What’s interesting about the video podcast, Nguyen suggests, is how Spotify is positioning itself as an interchangeable, if not more intimate, alternative to a pure audio podcast: “The video essay, then, appears to occupy a middle ground between podcast and traditional video by making use of these key elements. For creators, the boundaries are no longer so easy to define,” she writes.

The video essay is not a static format, and its development is heavily shaped by platforms, which play a crucial role in algorithmically determining how such content is received and promoted. Some of these changes are reflective of cultural shifts, too.

That’s because the basic premise of the video essay — whether the video is a mini-explainer or explores a 40-minute hypothesis — requires the creator to, at the very least, do their research. This often leads to personal disclaimers and summaries of alternative opinions or perspectives, which is very different from the more self-centered “reaction videos” and “story time” clickbait side of YouTube.

“The things I’m talking about are bigger than me. I recognize the limitations of my own experience,” Ferguson reports. “Once I started talking about intersections of race, gender, sexuality — so many experiences that were different from my own — I couldn’t just share my own narrow, straight, white woman perspective. I have to provide context.”

This is a positive shift, Nguyen concludes. “A video essay, in a way, encourages us to engage in good faith with ideas that we might not typically entertain or think of ourselves.”

Are you interested in contributing ideas, suggestions or opinions? We’d love to hear from you. Email us here .

- Content Creation

- Media Content

- Content Publishers

- Social Networking / UGC

for more content like this sent directly to your inbox:

Peer Reviewed

- How effective are TikTok misinformation debunking videos?

Article Metrics

CrossRef Citations

Altmetric Score

PDF Downloads

TikTok provides opportunity for citizen-led debunking where users correct other users’ misinformation. In the present study ( N =1,169), participants either watched and rated the credibility of (1) a misinformation video, (2) a correction video, or (3) a misinformation video followed by a correction video (“debunking”). Afterwards, participants rated both a factual and a misinformation video about the same topic and judged the accuracy of the claim furthered by the misinformation video. We found modest evidence for the effectiveness of debunking on people’s ability to subsequently discern between true and false videos, but stronger evidence on subsequent belief in the false claim itself.

Hill/Levene Schools of Business, University of Regina, Canada

Department of Psychology, University of Regina, Canada

Research Question

Essay summary.

- We conducted a preregistered survey experiment with 1,169 U.S. American participants , who saw TikTok-style videos on one of six misinformation topics (all of which were found on TikTok): aspartame, an artificial sweetener, causes cancer; COVID-19 isn’t dangerous given that infected people can be asymptomatic; the accidental shooting by the actor Alec Baldwin on the Rust movie set was on purpose; natural immunity is preferable to vaccinations; Ivermectin, an antiparasitic drug, can effectively treat COVID-19 symptoms; and simple tests can differentiate between left vs. right-brained people.

- Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions. They saw a misinformation video (misinformation-only condition), a correction video (correction-only condition), or a misinformation video followed by a correction video (debunking condition).

- Participants rated the credibility of a false and a true video related to their assigned topic and indicated how much they agreed with a false statement about their topic.

- We found a marginally significant interaction between the truth value of the video and the experimental condition (debunking vs. misinformation-only) for credibility ratings of post-treatment videos, indicating that debunking had a marginal effect on increased people’s ability to distinguish between subsequent true and false videos on the same topic.

- Critically, belief in the misinformation claim was significantly lower in the debunking condition compared to the misinformation-only condition.

- Qualitatively, effects were weaker in a correction-only condition relative to the debunking condition, indicating that the correction video was more effective if shown after the initial misinformation video.

Implications

The spread of misinformation on social media is a matter of growing concern (Lazer et al., 2018); suitably, research on the topic has massively grown in recent years (Tucker et al., 2018). In particular, investigating potential interventions against misinformation is a major focus (Pennycook & Rand, 2021), including a great deal of research specifically on the efficacy of fact-checking, corrections, and debunking (Chan et al., 2017; Nieminen & Rapeli, 2018; Porter & Wood, 2021). For example, it has been found that presenting a correction message with arguments that showcase a prior message as misinformation (i.e., “debunking”) can counter misinformation (Chan et al., 2017). Although debunking has shown some promise (Chan et al., 2017; Wood & Porter, 2019), studies on its effectiveness have yielded mixed results (Ecker et al., 2022; Nieminen & Rapeli, 2018). However, these studies tend to use static content, and misinformation comes in many forms. In particular, misinformation videos may pose a uniquely difficult target for debunking attempts because they often appear highly immersive, authentic, and relatable (Wang, 2020), which might cause people to process videos more superficially and believe them more readily (Sundar et al., 2021).

TikTok, a social media platform in which users upload short videos, has recently emerged as the fastest-growing social media platform and reportedly has over a billion monthly users (Bursztynsky, 2021). TikTok’s growing popularity and swelling user base raise concerns that TikTok may become a major source of misinformation (Basch et al., 2021). For example, in one analysis taken between January and March in 2020, it was found that 20–32% of the sampled COVID-19-related videos on TikTok contained some misleading or incorrect information (Southwick et al., 2021). Similarly, misinformation was surprisingly common in videos with masking-related hashtags when focusing on either the most-viewed videos and most-liked comments (Baumel et al., 2021), with falsehoods occurring from 6% to 45% of the time depending on the hashtag.

For these reasons, there has been increased focus on how to detect (Shang et al., 2021) and correct (Bautista et al., 2021) misinformation on TikTok. Interestingly, TikTok users can utilize its two unique editing features (“stitch,” which allows incorporation of someone else’s video in the beginning of a new video, and “duet,” which facilitates split-screen or picture-in-picture playback of someone else’s video and a new video) to incorporate misinformation TikTok videos into their own to create new citizen-led correction videos. Thus, although users may leverage the TikTok format to create compelling misinformation videos, the same can be true of videos that correct misinformation.

The current study aims to test the effectiveness of TikTok correction videos through a survey experiment that presented participants with either a misinformation video, a correction video, or both (in that order). This allowed us to test whether correction videos decreased susceptibility to misinformation by comparing a condition where participants are only exposed to misinformation (i.e., the “misinformation-only” baseline condition) with a condition where they receive a correction either on its own (the “correction-only” condition) or after having seen the misinformation video (the “debunking” condition). To assess the efficacy of corrections, we focused on two outcomes: 1) the ability of users to distinguish between different (and subsequently presented) true and false videos that are on the same topic (with the goal of assessing subsequent “on platform” behavior); that is, we assessed whether participants rated the subsequent true video as being more credible than the subsequent false video, and 2) whether users actually believed the false claim, measured using agreement with a false statement related to the topic of the misinformation video. To simplify the analysis, we focused on comparing the baseline “misinformation-only” condition against the two correction conditions (i.e., people either received only the correction video [the “correction-only” condition] or the misinformation video and then the correction video [the “debunking” condition]).

Our findings reveal moderate evidence for the effectiveness of debunking on TikTok. Watching a correction video does appear to improve credibility judgments of the same-topic subsequent videos watched on TikTok. However, this effect is weak and only marginally statistically significant in some specifications of the analysis. Furthermore, this weak effect only occurs if the correction video is immediately preceded by the misinformation video (i.e., debunking condition). Watching just the correction video did not improve our participants’ ability to distinguish between subsequent true and false videos on the same topic. Importantly, however, belief in false claims was lower for both the correction-only and debunking conditions relative to the misinformation-only control, indicating that the correction videos were effective in decreasing susceptibility to misinformation and that this occurred regardless of whether the context of the original video was present or not. These findings offer a strong parallel to the existing conclusion in the literature that there is mixed efficacy of using debunking as an intervention against misinformation. Overall, though, the videos were sufficiently effective to be considered a potential avenue for future intervention attempts and certainly a fruitful avenue for future research.

TikTok has become an important medium, not simply for entertainment but also for conveying information, and this is particularly true among younger people. Hence, studying misinformation interventions on TikTok is necessary to work towards creating better information environments into the future. To that end, our findings are useful for content creators on TikTok and for the platform itself. For creators, our results indicate that correction videos that contain misinformation claims in the beginning do have some efficacy in decreasing false beliefs. As such, users are encouraged to continue engaging in citizen-led debunking. In terms of the platform itself, our findings indicate that there is value in up-ranking correction videos to the extent possible. Future research is needed to test for how long TikTok debunking is effective, as well as whether different elements of TikTok videos (e.g., engagement numbers) influence the efficacy of debunking. More broadly, our results indicate that debunking TikTok videos can have some influence, and this is encouraging for those interested in correcting falsehoods on the fast-paced platform.

Finding 1: Debunking (vs. misinformation-only) marginally improves truth discernment for subsequent TikTok videos.

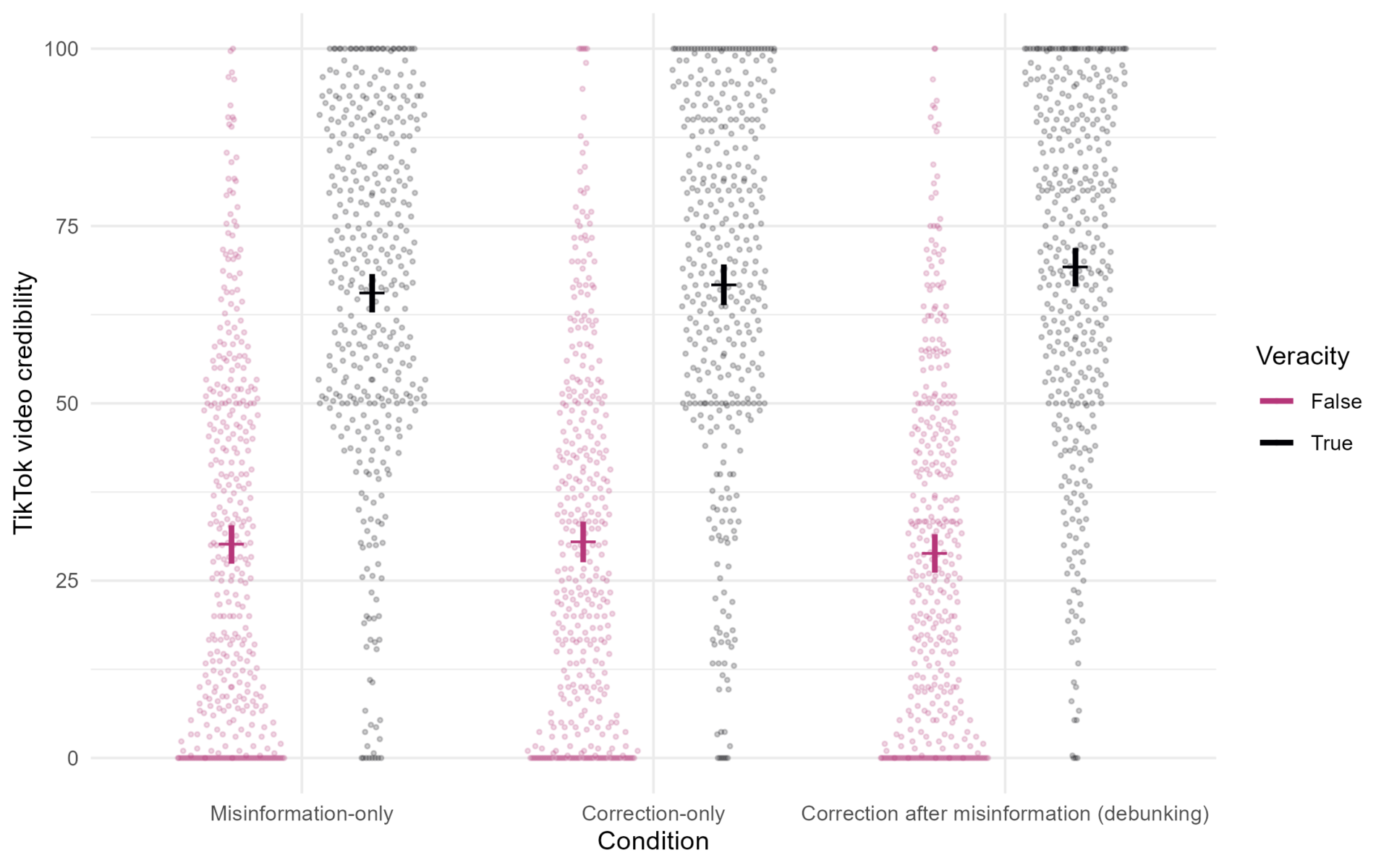

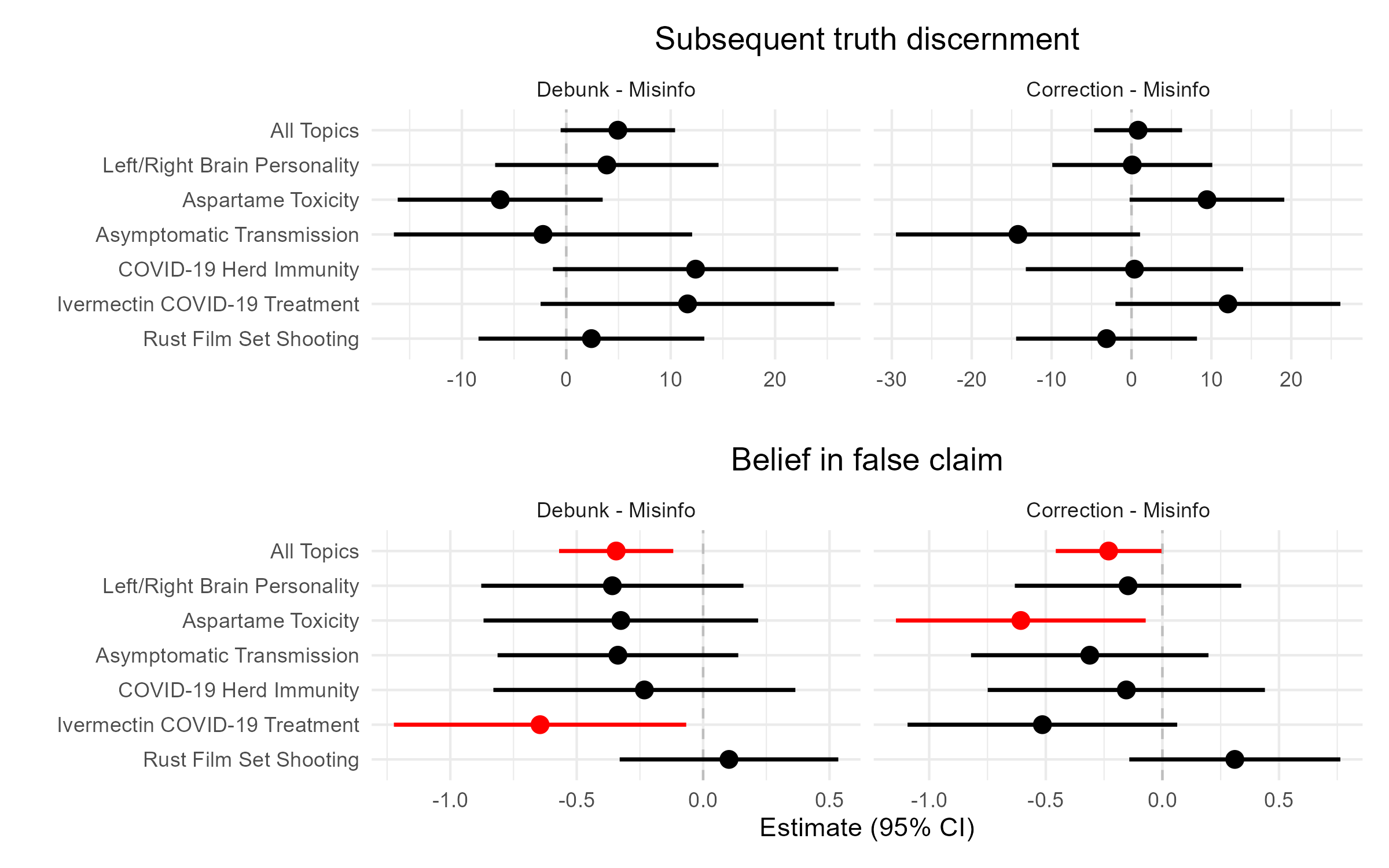

We first tested whether debunking (i.e., presenting a correction video after a misinformation video) improved people’s ability to distinguish between subsequent (i.e., post-treatment) true and false videos on the same topic. As preregistered (see OSF ), we fitted a 2 (video veracity: true vs. false) x 2 (condition: debunking vs. misinformation-only) mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA). Overall, the post-treatment true videos were found to be more credible than false ones, F (1, 783) = 757.61, p < .001, d = 0.98. Crucially, as predicted, we found that this difference between true and false videos was (marginally) greater for the debunking condition relative to the misinformation-only condition, as evidenced by an interaction between veracity and condition, F (1, 783) = 3.22, p = .073, d = 0.06, Figure 1. Put differently, debunking marginally improved overall accuracy for the subsequent video evaluation task. Excluding participants who failed attention checks resulted in a slightly stronger effect, F (1, 757) = 3.99, p = .046, d = 0.07 (see Appendix A). In terms of the underlying pattern of data, debunking (vs. misinformation-only) increased subsequent credibility ratings for true videos, b = 3.68 (1.78), t (1568) = 2.06, p = .039, but had no effect on credibility ratings for false videos, b = -1.26 (1.82), t (1568) = -0.70, p = .487, leading to overall higher truth discernment in the debunking condition relative to the misinformation-only condition. This difference can be seen in Figure 2 (top).

Next, we tested whether a correction video by itself improved people’s ability to distinguish between subsequent true and false videos (i.e., unlike in the debunking conditions, participants did not watch the misinformation video prior to watching the correction video—instead, they only watched the correction video). For this, we fitted a 2 (video veracity: true vs. false) x 2 (condition: correction-only vs. misinformation-only) mixed ANOVA (Figure 1). As above, true post-treatment videos were rated as more credible than false ones, F (1, 777) = 639.48, p < .001, d = 0.91. However, unlike for the debunking condition, this difference between true and false videos was not greater for the correction-only condition relative to the misinformation-only condition, as evidenced by a non-significant interaction between veracity and condition, F (1, 777) = 0.08, p = .771, d = 0.01. Thus, presenting only the correction video without the context of the original falsehood did not produce a significant increase in accuracy for the subsequent videos. Nonetheless, when we compared the debunking versus correction-only conditions with a 2 (video veracity: true vs. false) x 2 (condition: debunking vs. correction-only) mixed ANOVA, there were no differences in credibility or in the effect of veracity on credibility between conditions, F s < 2.11, p s> .147, d s < 0.05. Thus, although discernment was higher in the debunking condition relative to the misinformation condition (and this was not true of the correction condition), there was no difference between the debunking and correction conditions. See Appendix A for results from models that excluded participants who failed attention checks.

Finding 2: Debunking (vs. misinformation-only) reduces subsequent false belief.

In addition to rating the credibility of the TikTok videos, participants also indicated to what extent they believed false statements associated with each TikTok video (Figure 2, bottom). Overall, participants in the debunking (vs. misinformation-only) condition believed the false statements less, b = -0.34 (0.12), t (1166) = -2.99, p = .003, d = -0.17, and the effects were relatively consistent across topics (Figure 2, bottom left). Similarly, participants in the correction-only (vs. misinformation-only) condition also believed the false statements less, b = -0.23 (0.12), t (1166) = -1.99, p = .046, d = -0.12, but the effect was smaller and varied more across topics (Figure 2, bottom right). Together, these results suggest that showing debunking videos on TikTok had relatively weak effects on increasing subsequent video discernment but more robust effects on decreasing belief in false statements.

To summarize, we found that people were marginally better at distinguishing between true and false videos in the debunking relative to the misinformation-only condition, indicating some efficacy of presenting correction videos after an initial false video. Furthermore, belief in a relevant false statement was significantly lower in debunking (vs. misinformation-only) condition. Therefore, debunking showed a stronger effect for false belief reduction, signifying cross-platform applicability of results (for example, when users browse static social media websites after viewing videos on TikTok). Finally, correction videos were not as discernably effective if they were presented outside the context of the original falsehood.

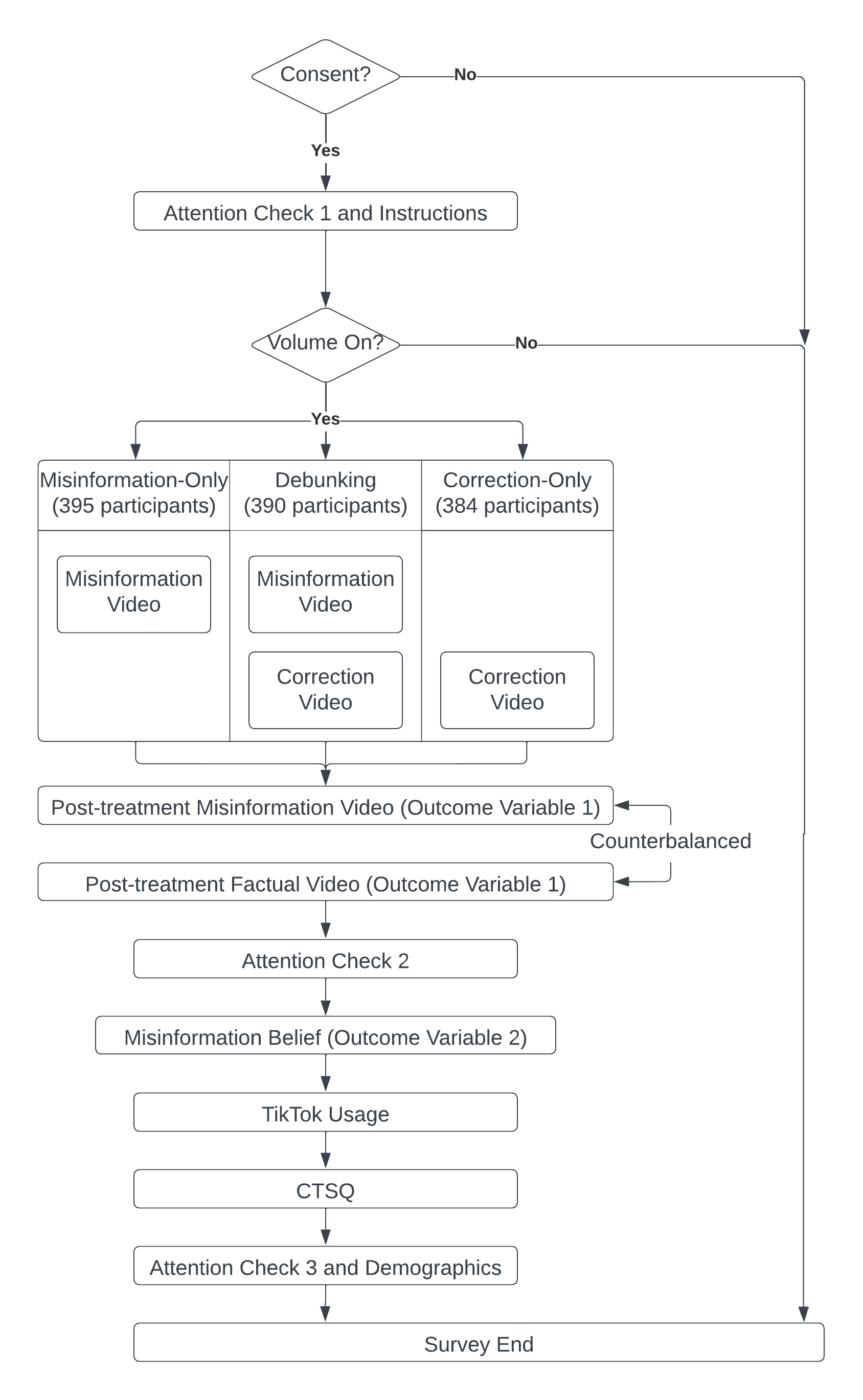

A total of 1,363 American participants were recruited via Prolific, an online recruitment service that gives a nationally representative sample based on quota-matching age, sex, region, and ethnicity. We removed 161 participants who did not complete the survey. The preregistration can be found on OSF . Following our preregistered exclusion plan, we excluded participants who failed the first attention check ( n = 32; see Figure 3). Participants were then informed that they would watch videos obtained from TikTok and that we were interested in their thoughts on the video’s accuracy. Before watching the TikTok videos, participants were instructed to turn on their audio device’s volume and had to verify that the volume was on (one participant was excluded because they could not turn the volume on). In total, 1,169 participants completed the study (mean age = 34.7, SD = 13.1; 347 male, 784 female, 38 non-binary/did not respond). There were also 33 participants who failed two additional (post-treatment) attention checks—see Appendix A for analyses with these participants removed. A majority (62%) of the sample had TikTok on their personal device, and the majority (68%) of these users watched videos on TikTok at least daily.

Participants were randomly assigned to watch and rate TikTok videos about one of six misinformation topics: aspartame toxicity (aspartame, an artificial sweetener, causes cancer), COVID-19 asymptomatic transmission (COVID-19 isn’t dangerous given that infected people can be asymptomatic), Rust film set shooting (the accidental shooting of Halyna Hutchins on the Rust movie set was not an accident), COVID-19 herd immunity (natural immunity is a better way to end the pandemic than vaccinations), Ivermectin COVID-19 treatment (Ivermectin can effectively treat COVID-19 symptoms), left or right-brain personality traits (simple brain tests can differentiate between left vs. right-brained people). These videos were found on TikTok and selected because a) they contained false information, b) were subject to subsequent correction videos (where they were specifically debunked), and c) there were other similar claims that could be found in other TikTok videos (that did not make reference to either the initial misinformation video or its correction). There were no additional selection criteria based on features of the video (beyond that, they contained misinformation or a correction), and hence the videos vary from each other in several aspects. All videos can be found on OSF .

All participants were also randomly assigned to the debunking condition ( N = 390), the disinformation-only condition ( N = 395), or the correction-only condition ( N = 384). Participants in the debunking condition watched a randomly-selected misinformation TikTok video followed by its contrasting debunking TikTok video. Participants in the misinformation-only condition watched a single misinformation TikTok video, whereas participants in the correction-only condition watched a single debunking TikTok video. Afterwards, all participants watched two subsequent videos on the same topic, one misinformation and one factual (the order of which was counterbalanced). The video credibility evaluations measure was given to the participants to answer after watching each TikTok video. For the video credibility evaluations, participants had to rate the accuracy, reliability, and impartiality of the information in the given video on a scale from 0 (“Not at all”) to 100 (“Extremely”). The scores on the three items were averaged to create the video credibility ratings. The three measures produced a reliable single credibility score (across items), Cronbach’s α = .92, although impartiality was not as highly correlated with accuracy ( r = .73) or reliability ( r = .74) as accuracy and reliability were correlated with each other ( r = .94). Means and standard deviations for all videos across conditions can be found in Appendix B.

After watching and rating the TikTok videos, participants answered an attention check question (21 participants failed; see Appendix C for wording). Participants then completed the follow-up questionnaire about the six misinformation topics, wherein they marked their agreement with one false statement per topic on a scale from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 7 (“Strongly agree”). Participants rated their agreement for all six topics, regardless of which video they watched. For example, for the aspartame topic, participants were asked to rate statements such as “Aspartame (an ingredient in diet soda) causes cancer.” After the topic questions, participants were asked if TikTok was downloaded on their electronic devices. Participants who answered “yes” were redirected to the two-item questionnaire about their TikTok usage and then directed to complete the Comprehensive Thinking Styles Questionnaire (CTSQ) (Newton et al., 2021). Participants who answered “No” were directly forwarded to the CTSQ. After the CTSQ, participants received another attention check question followed by the demographic questions (12 participants failed). To conclude, we asked participants how long it took them to complete the survey and allowed them to leave any additional comments (see Figure 3).

- Content Moderation

- / Debunking

- / Social Media

Cite this Essay

Bhargava, P., MacDonald, K. L., Newton, C., Lin, H., & Pennycook, G. (2023). How effective are TikTok misinformation debunking videos?. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review . https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-114

- / Appendix B

- / Appendix C

Bibliography

Basch, C. H., Meleo-Erwin, Z., Fera, J., Jaime, C., & Basch, C. E. (2021). A global pandemic in the time of viral memes: COVID-19 vaccine misinformation and disinformation on TikTok. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics , 17 (8), 2373–2377. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.1894896

Baumel, N. M., Spatharakis, J. K., Karitsiotis, S. T., & Sellas, E. I. (2021). Dissemination of mask effectiveness misinformation using TikTok as a medium. Journal of Adolescent Health , 68 (5), 1021–1022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.01.029

Bautista, J. R., Zhang, Y., & Gwizdka, J. (2021). Healthcare professionals’ acts of correcting health misinformation on social media. International Journal of Medical Informatics , 148 , 104375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2021.104375

Bursztynsky, J. (2021, September 27). TikTok says 1 billion people use the app each month . CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/09/27/tiktok-reaches-1-billion-monthly-users.html

Chan, M. S., Jones, C. R., Hall Jamieson, K., & Albarracín, D. (2017). Debunking: A meta-analysis of the psychological efficacy of messages countering misinformation. Psychological Science , 28 (11), 1531–1546. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617714579

Ecker, U. K. H., Lewandowsky, S., Cook, J., Schmid, P., Fazio, L. K., Brashier, N., Kendeou, P., Vraga, E. K., & Amazeen, M. A. (2022). The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nature Reviews Psychology , 1 (1), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-021-00006-y

Lazer, D., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., Metzger, M. J., Nyhan, B., Pennycook, G., Rothschild, D., Schudson, M., Sloman, S. A., Sunstein, C. R., Thorson, E. A., Watts, D. J., & Zittrain, J. L. (2018). The science of fake news. Science , 9 (6380), 1094–1096. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2998

Newton, C., Feeney, J., & Pennycook, G. (2021). On the disposition to think analytically: Four distinct intuitive-analytic thinking styles. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/OSF.IO/R5WEZ

Nieminen, S., & Rapeli, L. (2018). Fighting misperceptions and doubting journalists’ objectivity: A review of fact-checking literature. Political Studies Review , 17 (3), 296–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929918786852

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2021). The psychology of fake news. Trends in Cognitive Sciences , 25 (5), 388–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.02.007

Porter, E., & Wood, T. J. (2021). The global effectiveness of fact-checking: Evidence from simultaneous experiments in Argentina, Nigeria, South Africa, and the United Kingdom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 118 (37). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2104235118

Shang, L., Kou, Z., Zhang, Y., & Wang, D. (2021, December). A multimodal misinformation detector for COVID-19 short videos on TikTok. In 2021 IEEE international conference on big data (big data) (pp. 899–908). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/BigData52589.2021.9671928

Southwick, L., Guntuku, S. C., Klinger, E. V., Seltzer, E., McCalpin, H. J., & Merchant, R. M. (2021). Characterizing COVID-19 content posted to TikTok: Public sentiment and response during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health , 69 (2), 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.05.010

Sundar, S. S., Molina, M. D., & Cho, E. (2021). Seeing is believing: Is video modality more powerful in spreading fake news via online messaging apps? Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , 26 (6), 301–319. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmab010

Tucker, J., Guess, A. M., Barbera, P., Vaccari, C., Siegel, A., Sanovich, S., Stukal, D., & Nyhan, B. (2018). Social media, political polarization, and political disinformation: A review of the scientific literature . SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3144139

Wang, Y. (2020). Humor and camera view on mobile short-form video apps influence user experience and technology-adoption intent, an example of TikTok (DouYin). Computers in Human Behavior , 110 , 106373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106373

Wood, T., & Porter, E. (2019). The elusive backfire effect: Mass attitudes’ steadfast factual adherence. Political Behavior , 41 (1), 135–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9443-y

We gratefully acknowledge research funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, The John Templeton Foundation, the Government of Canada’s Digital Citizen Contribution Program, and the U.S. Department of Defense.

Competing Interests

G.P. was previously Faculty Research Fellow for Google and has received research funding from them.

This research received ethics approval from the University of Regina Research Ethics Board.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/0BL67B and OSF: https://osf.io/xfcsp

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — TikTok — TikTok’s Impact on Social Media

Tiktok's Impact on Social Media

- Categories: TikTok

About this sample

Words: 850 |

Published: Jan 30, 2024

Words: 850 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

Table of contents

Understanding tiktok's impact on social media, analyzing the positive aspects of tiktok, evaluating the negative aspects of tiktok, examining the controversies surrounding tiktok.

- Nandini Jammi, "TikTok is going to outlast Trump, but in the end, we're used to being guinea pigs," Poynter Institute, August 13, 2020.

- John E. Dunn, "Why privacy advocates hate TikTok," Naked Security by Sophos, July 28, 2020.

- Karen Hao, "The complete guide to TikTok safety settings," MIT Technology Review, July 31, 2020.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 496 words

2 pages / 689 words

2 pages / 1084 words

1 pages / 507 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on TikTok

The rise of social media platforms has brought about new forms of communication and expression, and TikTok has quickly become one of the most popular platforms among young users. However, the question of whether TikTok should be [...]