Article on Value Based Education | Short and Long | Learning for The Future

Value based education is the process of teaching and learning in which the values of honesty, respect, responsibility, cooperation, and compassion are emphasized. It helps children develop the skills they need to become caring and contributing members of society. Let’s dive deeper to read complete article on value based education –

Education which aims at creating only means of livelihood is not complete in itself unless it is supplemented with human values. Write an article in 150-200 words on the “Need of Value Education”, especially in the present day scenario of declining ethical values in the country. You are Shreya/ Shaan.

Ans. The need for Value Education

by Shreya

The world today is experiencing a systemic breakdown. There is an ongoing conflict between individual and social responsibilities of a person. A question increasingly being asked is that in the mad race of becoming modern have we somewhere lost our basic human values? It is always said that values are never taught, they are caught, but in the present scenario when parents don’t have time to be with their children, there is no source from where values can be imbibed. Fostering a child with values was always a family’s responsibility. But today with the fast-paced life the entire responsibility of providing values to the child falls on schools and educational institutions. It is the school which is an important stakeholder in a child’s development and nation-building. Making value education part of the curriculum is the only solution to protect society from getting degraded. This Endeavour is to saw as an investment in building the foundations for lifelong learning, promoting human existence as well as promoting social cohesion, national integration and global unity. Education is necessarily a process of inculcating values to equip the learner to lead a kind of life that is to satisfy the individual in accordance with the cherished values and ideals of the society. No education is value-free and goals of education include the goals of value education. A classroom has become the most influential place. It is in the classroom where the most important part of a person’s life is spent and only when values are taught here, we can expect the desired outcome. Bringing values in the curriculum will foster the worldwide vision of what true education is all about and create responsible members of the society and individuals leading a peaceful and morally just life.

Download the above Article in PDF (Printable)

Short Article on Value Based Education In 150 Words

Value based education is an approach to teaching that focuses on instilling values in students. The goal is to help students develop into good citizens who can make positive contributions to society. There are many different ways to incorporate value-based education into the classroom, but some common methods include incorporating service learning projects, teaching social and emotional skills, and promoting character development. One important aspect of value-based education is service learning. Service-learning projects give students the opportunity to put their values into action by working on behalf of others. These projects can be as simple as volunteering at a local food bank or helping to clean up a park. Not only do these projects provide valuable services to the community, but they also teach students about the importance of giving back. Another way to promote value-based education is by teaching social and emotional skills. These skills are essential for good citizenship, and they can be learned through classroom activities and discussions. When students are taught how to resolve conflict peacefully and how to cooperate with others, they are more likely to model these behaviors in their own lives.

Essay on Importance of Value Education- 200 Words

Value based education is an important aspect of a child’s development. It helps them to learn the importance of moral values and how to apply them in their everyday lives. By instilling these values at an early age, children can grow up to be responsible and contributing members of society. One of the main benefits of value based education is that it teaches children how to make good decisions. With so many choices available to them nowadays, it’s important for children to learn how to weigh up their options and choose the right path. Value based education gives them the tools they need to do this, and as a result, they are more likely to make decisions that are in their best interests. Another advantage of value-based education is that it fosters a sense of community. When everyone is working towards the same goal, there is a strong sense of togetherness and cooperation. This can help children feel like they belong to something bigger than themselves, and it can also teach them the importance of helping others. In conclusion, value based education is extremely beneficial for children. It helps them develop into well-rounded individuals who are able to make good decisions and contribute positively to society.

Importance of Value-Based Education Essay- 250 Words

In recent years, there has been a growing emphasis on the importance of value-based education. This type of education focuses on teaching students the importance of values such as honesty, respect, and responsibility. One of the main reasons why value-based education is so important is because it helps to instill these values in young people. When students are taught the importance of values such as honesty and respect, they are more likely to display these qualities in their own lives. Additionally, value-based education can help to create a more positive and productive society. When individuals possess values such as responsibility and respect, they are more likely to contribute to their community in a positive way. There are many different ways in which value-based education can be delivered. For example, many schools now have programs that teach students about character development and social responsibility. Additionally, many teachers try to incorporate values into their lesson plans. By doing so, they are helping their students to develop into well-rounded individuals who possess strong moral character. Value-based education is important because it helps individuals to develop into responsible and productive members of society. It also helps to create a more positive community by instilling values such as respect and responsibility in young people. In conclusion, value-based education is important for several reasons. First, it instills values in students that will help them become good citizens. Second, it helps students develop a strong work ethic and character. Finally, value-based education prepares students for the real world by teaching them how to make responsible decisions.

Article on Value Based Education 400 + Words

What is meant by value based education?

Value based education is an educational system that focuses on instilling values in students, rather than simply academic knowledge. The goal of value based education is to prepare students to be good citizens and productive members of society. Many schools and universities now have programs that focus on teaching values, such as respect, responsibility, honesty, and cooperation.

Characteristics of Value Education

Value education is concerned with the development of the individual’s character and personality. It is not just about imparting knowledge but also about the development of an individual’s values and attitude. The aim of value education is to help individuals become responsible and ethical citizens.

Following are 5 key characteristics of value education:

1. Value education instills in individuals a sense of responsibility towards society. 2. It helps individuals develop a positive attitude towards life. 3. Value education fosters in individuals a sense of respect for others and their property. 4. It encourages individuals to be honest and truthful in all their dealings. 5. Value education inculcates in individuals a sense of duty towards the nation and its people.

Why is value-based education important to life?

Value based education is important to life because it helps individuals develop a strong sense of self-worth and purpose. In addition, value-based education can promote physical and mental health, as well as social and emotional well-being. Furthermore, value-based education can instill in individuals a desire to contribute to their community and society at large. Finally, value-based education can provide individuals with the skills and knowledge necessary to succeed in today’s increasingly complex world.

5 Values of Education

There are many values of education, but five of the most important ones are:

1. Education develops critical thinking and problem-solving skills. 2. Education helps us to become more independent and self-sufficient. 3. Education leads to improved employment prospects and higher earnings. 4. Education helps us to understand and appreciate other cultures. 5. Education can help to reduce crime and social problems.

Principles of Value Based Education

1. Developing a sense of self-worth: Every individual has intrinsic worth and should be treated with dignity and respect. 2. Promoting social and emotional learning: Students should be taught how to manage their emotions, set goals, and resolve conflicts. 3. Encouraging pro-social behavior: Students should be encouraged to cooperate, help others, and make positive contributions to their community. 4. Fostering moral development: Students should be given opportunities to explore ethical issues and develop their own moral code.

Main Goal of Values Education

The main goal of values education is to instill in students the importance of living by a set of moral and ethical values. These values can include honesty, integrity, respect, compassion, and responsibility. By teaching students to live by these values, they will be better equipped to handle the challenges and opportunities that life will present them with.

Factors of Value Education

1. A focus on the individual – Value education should be tailored to the needs of the individual and their unique circumstances. 2. A focus on relationships – Value education should help individuals to develop positive relationships with others. 3. A focus on life skills – Value education should help individuals to develop essential life skills such as communication, problem-solving and decision-making. 4. A focus on character development – Value education should help individuals to develop positive character traits such as honesty, responsibility and respect. 5. A focus on personal growth – Value education should help individuals to grow and develop as people, both intellectually and emotionally.

Related Posts

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- Leverage Beyond /

Importance of Value Education

- Updated on

- Jan 18, 2024

What is Value Education? Value-based education emphasizes the personality development of individuals to shape their future and tackle difficult situations with ease. It moulds the children so they get attuned to changing scenarios while handling their social, moral, and democratic duties efficiently. The importance of value education can be understood through its benefits as it develops physical and emotional aspects, teaches mannerisms and develops a sense of brotherhood, instils a spirit of patriotism as well as develops religious tolerance in students. Let’s understand the importance of value education in schools as well as its need and importance in the 21st century.

Here’s our review of the Current Education System of India !

This Blog Includes:

Need and importance of value education, purpose of value education, importance of value education in school, difference between traditional and value education, essay on importance of value education, speech on importance of value education, early age moral and value education, young college students (1st or 2nd-year undergraduates), workshops for adults, student exchange programs, co-curricular activities, how it can be taught & associated teaching methods.

This type of education should not be seen as a separate discipline but as something that should be inherent in the education system. Merely solving problems must not be the aim, the clear reason and motive behind must also be thought of. There are multiple facets to understanding the importance of value education.

Here is why there is an inherent need and importance of value education in the present world:

- It helps in making the right decisions in difficult situations and improving decision-making abilities.

- It teaches students with essential values like kindness, compassion and empathy.

- It awakens curiosity in children developing their values and interests. This further helps in skill development in students.

- It also fosters a sense of brotherhood and patriotism thus helping students become more open-minded and welcoming towards all cultures as well as religions.

- It provides a positive direction to a student’s life as they are taught about the right values and ethics.

- It helps students find their true purpose towards serving society and doing their best to become a better version of themselves.

- With age comes a wide range of responsibilities. This can at times develop a sense of meaninglessness and can lead to a rise in mental health disorders, mid-career crisis and growing discontent with one’s life. Value education aims to somewhat fill the void in people’s lives.

- Moreover, when people study the significance of values in society and their lives, they are more convinced and committed to their goals and passions. This leads to the development of awareness which results in thoughtful and fulfilling decisions.

- The key importance of value education is highlighted in distinguishing the execution of the act and the significance of its value. It instils a sense of ‘meaning’ behind what one is supposed to do and thus aids in personality development .

In the contemporary world, the importance of value education is multifold. It becomes crucial that is included in a child’s schooling journey and even after that to ensure that they imbibe moral values as well as ethics.

Here are the key purposes of value education:

- To ensure a holistic approach to a child’s personality development in terms of physical, mental, emotional and spiritual aspects

- Inculcation of patriotic spirit as well as the values of a good citizen

- Helping students understand the importance of brotherhood at social national and international levels

- Developing good manners and responsibility and cooperativeness

- Promoting the spirit of curiosity and inquisitiveness towards the orthodox norms

- Teaching students about how to make sound decisions based on moral principles

- Promoting a democratic way of thinking and living

- Imparting students with the significance of tolerance and respect towards different cultures and religious faiths

There is an essential need and importance of value education in school curriculums as it helps students learn the basic fundamental morals they need to become good citizens as well as human beings. Here are the top reasons why value education in school is important:

- Value education can play a significant role in shaping their future and helping them find their right purpose in life.

- Since school paves the foundation for every child’s learning, adding value-based education to the school curriculum can help them learn the most important values right from the start of their academic journey.

- Value education as a discipline in school can also be focused more on learning human values rather than mugging up concepts, formulas and theories for higher scores. Thus, using storytelling in value education can also help students learn the essentials of human values.

- Education would surely be incomplete if it didn’t involve the study of human values that can help every child become a kinder, compassionate and empathetic individual thus nurturing emotional intelligence in every child.

Both traditional, as well as values education, is essential for personal development. Both help us in defining our objectives in life. However, while the former teaches us about scientific, social, and humanistic knowledge, the latter helps to become good humans and citizens. Opposite to traditional education, values education does not differentiate between what happens inside and outside the classroom.

Value Education plays a quintessential role in contributing to the holistic development of children. Without embedding values in our kids, we wouldn’t be able to teach them about good morals, what is right and what is wrong as well as key traits like kindness, empathy and compassion. The need and importance of value education in the 21st century are far more important because of the presence of technology and its harmful use. By teaching children about essential human values, we can equip them with the best digital skills and help them understand the importance of ethical behaviour and cultivating compassion. It provides students with a positive view of life and motivates them to become good human beings, help those in need, respect their community as well as become more responsible and sensible.

Youngsters today move through a gruelling education system that goes on almost unendingly. Right from when parents send them to kindergarten at the tender age of 4 or 5 to completing their graduation, there is a constant barrage of information hurled at them. It is a puzzling task to make sense of this vast amount of unstructured information. On top of that, the bar to perform better than peers and meet expectations is set at a quite high level. This makes a youngster lose their curiosity and creativity under the burden. They know ‘how’ to do something but fail to answer the ‘why’. They spend their whole childhood and young age without discovering the real meaning of education. This is where the importance of value education should be established in their life. It is important in our lives because it develops physical and emotional aspects, teaches mannerisms and develops a sense of brotherhood, instils a spirit of patriotism as well as develops religious tolerance in students. Thus, it is essential to teach value-based education in schools to foster the holistic development of students. Thank you.

Importance of Value Education Slideshare PPT

Types of Value Education

To explore how value education has been incorporated at different levels from primary education, and secondary education to tertiary education, we have explained some of the key phases and types of value education that must be included to ensure the holistic development of a student.

Middle and high school curriculums worldwide including in India contain a course in moral science or value education. However, these courses rarely focus on the development and importance of values in lives but rather on teachable morals and acceptable behaviour. Incorporating some form of value education at the level of early childhood education can be constructive.

Read more at Child Development and Pedagogy

Some universities have attempted to include courses or conduct periodic workshops that teach the importance of value education. There has been an encouraging level of success in terms of students rethinking what their career goals are and increased sensitivity towards others and the environment.

Our Top Read: Higher Education in India

Alarmingly, people who have only been 4 to 5 years into their professional careers start showing signs of job exhaustion, discontent, and frustration. The importance of value education for adults has risen exponentially. Many non-governmental foundations have begun to conduct local workshops so that individuals can deal with their issues and manage such questions in a better way.

Recommended Read: Adult Education

It is yet another way of inculcating a spirit of kinship amongst students. Not only do student exchange programs help explore an array of cultures but also help in understanding the education system of countries.

Quick Read: Scholarships for Indian Students to Study Abroad

Imparting value education through co-curricular activities in school enhances the physical, mental, and disciplinary values among children. Furthermore, puppetry , music, and creative writing also aid in overall development.

Check Out: Drama and Art in Education

The concept of teaching values has been overly debated for centuries. Disagreements have taken place over whether value education should be explicitly taught because of the mountainous necessity or whether it should be implicitly incorporated into the teaching process. An important point to note is that classes or courses may not be successful in teaching values but they can teach the importance of value education. It can help students in exploring their inner passions and interests and work towards them. Teachers can assist students in explaining the nature of values and why it is crucial to work towards them. The placement of this class/course, if there is to be one, is still under fierce debate.

Value education is the process through which an individual develops abilities, attitudes, values as well as other forms of behaviour of positive values depending on the society he lives in.

Every individual needs to ensure a holistic approach to their personality development in physical, mental, social and moral aspects. It provides a positive direction to the students to shape their future, helping them become more responsible and sensible and comprehending the purpose of their lives.

Values are extremely important because they help us grow and develop and guide our beliefs, attitudes and behaviour. Our values are reflected in our decision-making and help us find our true purpose in life and become responsible and developed individuals.

The importance of value education at various stages in one’s life has increased with the running pace and complexities of life. It is becoming difficult every day for youngsters to choose their longing and pursue careers of their choice. In this demanding phase, let our Leverage Edu experts guide you in following the career path you have always wanted to explore by choosing an ideal course and taking the first step to your dream career .

Team Leverage Edu

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Your Article is awesome. It’s very helpful to know the value of education and the importance of value education. Thank you for sharing.

Hi Anil, Thanks for your feedback!

Value education is the most important thing because they help us grow and develop and guide our beliefs, attitudes and behaviour. Thank you for sharing.

Hi Susmita, Rightly said!

Best blog. well explained. Thank you for sharing keep sharing.

Thanks.. For.. The Education value topic.. With.. This.. Essay. I.. Scored.. Good. Mark’s.. In.. My. Exam thanks a lot..

Your Article is Very nice.It is Very helpful for me to know the value of Education and its importance…Thanks for sharing your thoughts about education…Thank you ……

Leaving already?

8 Universities with higher ROI than IITs and IIMs

Grab this one-time opportunity to download this ebook

Connect With Us

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

September 2024

January 2025

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

2020 Articles

Critical Pedagogy in the New Normal: Teaching values-based education online

Maboloc, Christopher Ryan

Photo by Thought Catalog on Unsplash INTRODUCTION The coronavirus pandemic is a challenge to educators, policy makers, and ordinary people. In facing the threat from COVID-19, school systems and global institutions need “to address the essential matter of each human being and how they are interacting with, and affected by, a much wider set of biological and technical conditions.”[1] Educators must grapple with the societal issues that come with the intent of ensuring the safety of the public. To some, “these are actually as important as the biological concerns of people.”[2] The current global crisis shows that “scientifically, socially, and politically the economy and technosphere are not just related, they are integral to a comprehensive response to major challenges.”[3] In developing these responses, scientists, government leaders, and policy makers need to consider the vulnerabilities of people, especially those in “thrown away” groups.[4] Jerome Ravetz explains that “microscopic viral predators cull our populations, as ever, but with a selection that is not natural but social and political.”[5] Educators must address the underlying vulnerabilities and evaluate the virus as a threat to academic experiences and access to a fair education. ANALYSIS Critical Pedagogy By definition, the critical approach to teaching is about the problem-posing method of education developed by Paolo Freire. In his Pedagogy of the Oppressed, he proposed a paradigm shift away from the banking method of learning wherein teachers deposit knowledge into the minds of students. Critical pedagogy is an educational approach that challenges students to develop the ability to recognize and criticize dominating theories and evaluate them in their social context. Teachers press students to recognize oppression and try to remedy oppression in their culture.[6] Despite the lack of in-person interaction between the teacher and the students, the effort to use innovative teaching techniques like critical pedagogy should continue. Online learning is not just about the use of technology, although the internet is crucial in the delivery of content. Since human beings are creators of value, they determine the meaning and purpose of technology. In this way, the set of values people have will influence online learning. Teachers cannot be more concerned about outcomes than about the process itself. The process is crucial since the ability of the student to think critically is developed in the exchange between the student and the teacher. The teacher cannot simply dump loads of information (deposit knowledge) but must pose problems to test the analytical and critical skills of students.[7] Education is about how people humanize the world. Policy makers miss the point when they focus on the delivery but do not pay attention to the substantive aspect of learning, which is human empowerment. Education is meant to expand the freedom of people. Education should be seen as an integrative activity. Learning is a formative process that aims to develop the human person. Without the face-to-face encounter between teacher and students, the challenge is finding ways to make learning an effective means to mold the values of young people. Online Critical Pedagogy & the Role of Technology Physical distance appears to be an impediment in realizing the ideals of learning. The lack of contact between the teacher and the students may prevent a more meaningful interaction since online instruction is impersonal. It can be argued that there is no alternative to some classroom activities, especially laboratory experiments in science courses. The total classroom environment naturally influences the behavior of students when it comes to academic work: the look in the eyes of the professor, the caring ways of a teacher, or the pressure while taking exams contribute to an experience that only a classroom setting can provide. If implemented properly, technology can facilitate the personal relationships between teachers and students while providing meaningful experiences. With the current need for online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, gadgets are indispensable. Some would even consider gadgets an extension of the human body. A mobile phone is not just any instrument; it has evolved into a novel way of being in the world. Our gadgets are a means of seeing how the outside world unfolds. Modern technological tools allow the interface of people in many fields of experience in a globalized environment. Computers and other digital devices extend the meaning and value of human freedom. For example, a laptop provided to a poor child can redefine the meaning of and what the future might hold for that child. The device is crucial to the whole learning process. Modern tools are critical to self-discovery and greater freedom. The values that people embrace will matter in the new normal. The internet has provided a new democratic space that empowers groups and individuals to express themselves and to understand the world.[8] In an online class, students and teachers alike need to analyze big picture questions and layers of information. For example, the student in an ethics or philosophy class can reflect on the realities of life. With the proper guidance, online education should help define the meaning of moral commitment and human responsibility. CONCLUSION Before the pandemic, policy makers had been pursuing the goals of a globalized economy. They had been fashioning and promoting programs that cater to the interests of a consumer-driven world that has deprived the poor of opportunity. When the pandemic struck, globalization suddenly came to a halt and people realized the things that truly matter in life – family, love, and life itself. The new normal must now emphasize the role of education as a source of inner strength that can empower the person to live well reinforcing values based on a social consciousness. Critical pedagogy is possible under the new normal. The distance between the teacher and student does not make the educational process less real and in the absence of a vaccine, online learning is the safest strategy. Governments cannot freeze an entire school year since education is the only way out from poverty for millions. The COVID-19 pandemic provides a reason to re-imagine teaching using technology to encourage all students to question systems of oppression or greed, as the persistent pursuit of the truth is what education is all about. [1] Hartsell, Layne, Krabbe, Alexander, & Pastreich, Emmanuel. “Covid-19, Global Justice, and a New Biopolitics of the Anthropocene.” Social Ethics Society Journal of Applied Philosophy 6, no. 2 (2020), 3. [2] Ravetz, Jerome. “Science for a Proper Recovery: Post-Normal, not New Normal.” Issues in Science and Technology [Internet] July 15, 2020. https://issues.org/post-normal-science-for-pandemic-recovery/ [3] Hartsell, et al. “Covid-19, Global Justice, and a New Biopolitics of the Anthropocene,” 6. [4] Ravetz, “Science for a Proper Recovery: Post-Normal, not New Normal.” [5] Ibid. [6] Freire, Paolo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. (New York: Continuum Books, 1993). [7] Freire writes that in such a situation “instead of communicating, the teacher issues communiqués and makes deposits which the students patiently receive, memorize, and repeat.” See his Pedagogy of the Oppressed. [8] Bakardjieva, Maria. Internet Society. (London: Sage Publications, 2005).

- Medical ethics

- Bioethics--Philosophy

Also Published In

More about this work.

Education, Online Education, Online learning, Critical Pedagogy, COVID-19, Global education

- DOI Copy DOI to clipboard

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

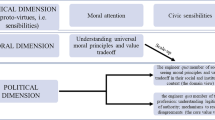

15 Values Education

Graham Oddie, Professor of Philosophy, University of Colorado, Boulder

- Published: 02 January 2010

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article offers a metaphysical account of value as part of a general approach to values education. Value endorsements and their transmission are unavoidable in educational settings, as they are everywhere. The question, then, is not whether to teach values but which values to teach, in what contexts and how to teach them effectively. This article discusses the contestedness of value endorsements, the place for noncognitive value endorsements in education and the role of inculcating beliefs in education. The article also describes the rationalist and empiricist response problem of intrinsic motivation.

Moral education has received a great deal of attention in the philosophy of education. But morality is just one aspect of the evaluative, which embraces not just the deontic concepts—right, wrong, permissible, obligatory, supererogatory, and so on—but also the full range of concepts with evaluative content. This includes the so‐called thin evaluative concepts (e.g., good, bad, better, worst ); the thick evaluative concepts (e.g., courageous, compassionate, callous, elegant, cruel, charming, clumsy, humble, tendentious, witty, craven, generous, salacious, sexy, sarcastic, vindictive ); and the concepts that lie somewhere between the extremes of thick and thin (e.g., just, virtuous, sublime, vicious, beautiful ). Value, broadly construed to embrace the entire range of evaluative concepts, presents an educationist with some problems. Should values be part of the curriculum at all? If so, which values is it legitimate for educators to teach and how should they be taught?

1. The Contestedness of Value Endorsements

Philosophers disagree wildly about the metaphysics of value, its epistemological status, and the standing of various putative values. Given the heavily contested nature of value, as well as of the identity and weight of particular putative values, what business do we have teaching values? Perhaps we don't know enough about values to teach them (perhaps we don't know anything at all 1 ).

It might be objected to this argument against the teaching of values, from value's contestedness, that value theory is no different from, say, physics, biology, or even mathematics. There is much about these disciplines that is contested, but no one argues that that's a good reason to purge them from the curriculum. This comparison, however, is not totally convincing. True, philosophers of physics disagree over the correct interpretation of quantum mechanics, but there is little disagreement over its applications, its significance, or the necessity for students to master it. Similarly, even if there is disagreement over the foundations of mathematics or biology, few deny that we should give children a solid grounding in arithmetic or evolution.

The contestedness of value has been used to argue for a “fact/value” distinction that, when applied to educational contexts, leads to the injunction that teachers should stick to the “facts,” eschewing the promulgation of “value judgments.” Given the contestedness of values, an educator should pare her value endorsements down to their purely natural (nonevaluative) contents, indicating at most that, as a matter of personal preference, she takes a certain evaluative stance.

2. The Value Endorsements Informing the Educational Enterprise

Attempts to purge education of value endorsements are, of course, doomed. Value endorsements are not just pervasive, they are inevitable. The educational enterprise is about the transmission of knowledge and the skills necessary to acquire, extend, and improve knowledge. But what is knowledge—along with truth, understanding, depth, empirical adequacy, simplicity, coherence, completeness, and so on—if not a cognitive good or value? 2 And what is an improvement in knowledge if not an increase in cognitive value? Sometimes cognitive values are clearly instrumental—acquiring knowledge might help you become a physicist, a doctor, or an artist, say. But instrumental value is parasitic upon the intrinsic value of something else—here, knowledge of the world, relieving suffering, or creating things of beauty.

The enterprise of creating and transmitting knowledge is freighted with cognitive value, but episodes within the enterprise also express particular value endorsements. A curriculum, for example, is an endorsement of the value of attending to the items on the menu. It says, “ These are worth studying.” The practice of a discipline is laden with norms and values. To practice the discipline you have to learn how to do it well : to learn norms and values governing, inter alia, citing and acknowledging others who deserve it; honestly recording and relaying results; not forging, distorting, or suppressing data; humbly acknowledging known shortcomings; courageously, but not recklessly, taking cognitive risks; eschewing exaggeration of the virtues of a favored theory; having the integrity to pursue unwelcome consequences of discoveries. In mastering a discipline, one is inducted into a rich network of value endorsements.

The thesis of the separability of fact and value, and the associated bracketing of value endorsements, is not just tendentious (it precludes the possibility of facts about value) but also is so clearly unimplementable that it is perhaps puzzling that it has ever been taken entirely seriously. The educational enterprise is laden with value endorsements distinctive of the enterprise of knowledge and the transmission of those very endorsements to the next generation. Without the transmission of those values, our educational institutions would disappear. So, even if the value endorsements at the core of education are contested, the enterprise itself requires their endorsement and transmission.

3. The Place for Noncognitive Value Endorsements in Education

To what extent does the transmission of cognitive values commit us to the teaching of other values? It would be fallacious to infer that, in any educational setting, all and any values are on the table—that it is always permissible, or always obligatory, for a teacher to impart his value endorsements when those are irrelevant to the central aims of the discipline at hand. For certain value issues, a teacher may have no business promulgating his endorsements. For example, the values that inform physics don't render it desirable for a physicist to impart his views on abortion during a lab. Physicists typically have no expertise on that issue.

But it would be equally fallacious to infer that cognitive values are tightly sealed off from noncognitive values. Certain cognitive values, however integral to the enterprise of knowledge, are identical to values with wider application. Some I have already adverted to: honesty, courage, humility, integrity, and the like. These have different applications in different contexts, but it would be odd if values bearing the same names within and without the academy were distinct. So, in transmitting cognitive values, one is ipso facto involved in transmitting values that have wider application. 3 This doesn't imply that an honest researcher will be an honest spouse—she might lie about an affair. And an unscrupulous teacher might steal an idea from one of his students without being tempted to embezzle. People are inconsistent about the values on which they act, but these are the same values honored in the one context and dishonored in the other.

I have argued that there are cognitive values informing the educational enterprise that need to be endorsed and transmitted, and that these are identical to cognate values that have broader application. However, this doesn't exhaust the values that require attention in educational settings. There are disciplines—ethics, for example—in which the subject matter itself involves substantive value issues. In a course on the morality of abortion, for example, it would be impossible to avoid talking about the value of certain beings and the disvalue of ending their existence. Here, explicit attention must be paid to noncognitive values. There are other disciplines—the arts, for example—in which the point of education is to teach students to discern aesthetically valuable features, to develop evaluative frameworks to facilitate future investigations, and to produce valuable works. Within such disciplines it would be incredibly silly to avoid explicit evaluation.

4. The Role of Inculcating Beliefs in Education

Grant that there are noncognitive values, as well as cognitive values, at the core of certain disciplines. Still, given that there are radically conflicting views about these—the value of a human embryo, or the value of Duchamp's Fountain—shouldn't teachers steer clear of explicitly transmitting value endorsements? Here, at least, isn't it the teacher's responsibility to distance himself from his value endorsements and teach the subject in some “value‐neutral” way?

In contentious areas, teachers should obviously be honest and thorough in their treatment of the full range of conflicting arguments. Someone who thinks abortion is impermissible should give both Thomson's and Tooley's famous arguments for permissibility a full hearing. Someone who thinks abortion permissible should do the same for Marquis's. 4 However, even if some fact about value were known , there are still good reasons for teachers not to indoctrinate, precisely because inducing value knowledge is the aim of the course.

Value knowledge, like all knowledge, is not just a matter of having true beliefs. Knowledge is believing what is true for good reasons. To impart knowledge, one must cultivate the ability to embrace truths for good reasons. Students are overly impressed by the fact that their teachers have certain beliefs, and they are motivated to embrace such beliefs for that reason alone. So, it's easy for a teacher to impart favored beliefs, regardless of where the truth lies. A teacher will do a better job of imparting reasonable belief—and the critical skills that her students will need to pursue and possess knowledge—if she does not reveal overbearingly her beliefs. That's a common teaching strategy whatever the subject matter, not just value. 5

The appropriate educational strategy may appear to be derived from a separation of the evaluative from the non‐evaluative, but its motivation is quite different. It is because the aim of values education is value knowledge (which involves reasonable value beliefs) rather than mere value belief, that instructors should eschew indoctrination.

5. The Natural/Value Distinction Examined

In ethics and the arts, noncognitive values constitute the subject matter. But that isn't the norm. In many subject areas, values aren't the explicit subject matter. Despite this, in most disciplines it isn't clear where the subject itself ends and questions of value begin. Even granted a rigorous nonvalue/value distinction, for logical reasons there are, inevitably, claims that straddle the divide. It would be undesirable, perhaps impossible, to excise such claims from the educational environment.

Consider a concrete example. An evolutionary biologist is teaching a class on the evolutionary explanation of altruism. He argues that altruistic behavior is explicable as “selfishness” at the level of genes. His claim, although naturalistic, has implications for the value of altruistic acts. Suppose animals are genetically disposed to make greater sacrifices for those more closely genetically related to them than for those only distantly related, because such sacrifices help spread their genes. Suppose that the value of an altruistic sacrifice is partly a function of overcoming excessive self‐regard. It would follow that the value of some altruistic acts—those on behalf of close relatives—would be diminished. And that is a consequence properly classified as evaluative. Of course, this inference appeals to a proposition connecting value with the natural, but such propositions are pervasive and ineliminable.

Here is an argument for the unsustainability of a clean natural/value divide among propositions. A clean divide goes hand in glove with the Humean thesis that a purely evaluative claim cannot be validly inferred from purely natural claims, and vice versa. Let N be a purely natural claim and V a purely evaluative claim. Consider the conditional claim C : if N then V . Suppose C is a purely natural claim. Then from two purely natural claims ( N and C ) one could infer a purely evaluative claim V . Suppose instead that C is purely evaluative. The conjunction of two purely evaluative (natural) claims is itself purely evaluative (natural). Likewise, the negation of a purely evaluative (natural) proposition is itself purely evaluative (natural). 6 Consequently, not‐ N , like N , is purely natural, and so one could derive a purely evaluative claim ( C ) from a purely natural claim (not‐ N ). Alternatively, not‐ V , like V , is purely evaluative. So, one could derive a purely natural claim (not‐ N ) from two purely evaluative claims ( C and not‐ V ).

Propositions like C are natural‐value hybrids : they cannot be coherently assigned a place on either side of a sharp natural/value dichotomy. Hybrids are not just propositions that have both natural and evaluative content (like the thick evaluative attributes). Rather, their characteristic feature is that their content is not the conjunction of their purely natural and purely evaluative contents.

Hybrids are rife among the propositions in which we traffic. Jack believes Cheney unerringly condones what's good (i.e., Cheney condones X if and only if X is good), and Jill, that Cheney unerringly condones what's not good. Neither Jack nor Jill knows that Cheney has condoned the waterboarding of suspected terrorists. As it happens, both are undecided on the question of the value of waterboarding suspected terrorists. They don't disagree on any purely natural fact (neither knows what Cheney condoned); nor do they disagree on any purely evaluative fact (neither knows whether condoning waterboarding is good). They disagree on this: Cheney condones waterboarding suspected terrorists if and only if condoning such is good . Suppose both come to learn the purely natural fact that Cheney condones waterboarding. They will deduce from their beliefs conflicting, purely evaluative conclusions: Jack that condoning waterboarding is good; Jill that condoning waterboarding is not good. So, given that folk endorse rival hybrid propositions, settling a purely natural fact will impact the value endorsements of the participants differentially because natural facts and value endorsements are entangled via a rich set of hybrids.

I don't deny that there are purely natural or purely evaluative claims, nor that certain claims can be disentangled into their pure components. I am arguing that there are hybrids—propositions that are not equivalent to the conjunction of their natural and evaluative components. The fact that we all endorse hybrid claims means that learning something purely natural will often exert rational pressure on evaluative judgments (and vice versa). An education in the purely natural sciences may thus necessitate a reevaluation of values; and an education in values may necessitate a rethinking of purely natural beliefs.

6. Intrinsically Motivating Facts and the Queerness of Knowledge of Value

I have argued that natural and evaluative endorsements cannot be neatly disentangled in an educational setting for purely logical reasons. Still, it's problematic to embrace teaching a subject unless we have a body of knowledge . For there to be value knowledge there must be knowable truths about value. A common objection to these is that they would be very queer —unlike anything else that we are familiar with in the universe.

The queerness of knowable value facts can be elicited by considering their impact on motivation. Purely natural facts are motivationally inert. For example, becoming acquainted with the fact that this glass contains potable water (or a lethal dose of poison) does not by itself necessarily motivate me to drink (or refrain from drinking). Only in combination with an antecedent desire on my part (to quench my thirst, or to commit suicide) does this purely natural fact provide me with a motivation. A purely evaluative fact would, however, be different. Suppose it's a fact that the best thing for me to do now would be to drink potable water, and that I know that fact. Then it would be very odd for me to say, “I know that drinking potable water would be the best thing for me to do now, but I am totally unmoved to do so.” One explanation of this oddness is that knowledge of a value fact entails a corresponding desire: value facts necessarily motivate those who become acoquainted with them.

Why would this intrinsic power to motivate be queer rather than simply interesting ? The reason is that beliefs and desires seem logically independent—having a certain set of beliefs does not entail the having of any particular desires. Beliefs about value would violate this apparent independence. Believing that something is good would entail having a corresponding desire . Additionally, simply by virtue of imparting to your student a value belief you would thereby instill in him the corresponding motivation to act. How can mere belief necessitate a desire? Believing something good is one thing; desiring it is something else.

One response to the queerness objection is to reject the idea that knowing an evaluative fact necessarily motivates. Let's suppose, with Hume, that beliefs without desires are powerless to motivate. A person may well have a contingent independent desire to do what he believes to be good, and once he becomes acquainted with a good he may, contingently, be motivated to pursue it. But no mere belief, in isolation from such an antecedent desire, can motivate. That sits more easily with the frequent gap between what values we espouse and how we actually behave.

This Humean view would escape the mysteries of intrinsic motivation, but would present the educationist with a different problem. What is the point of attempting to induce true value beliefs if there is no necessary connection between value beliefs and motivations? If inducing true evaluative beliefs is the goal of values education, and evaluative beliefs have no such connection with desires, then one might successfully teach a psychopath correct values, but his education would make him no more likely to choose the good. His acquisition of the correct value beliefs , coupled with his total indifference to the good, might just equip him to make his psychopathic adventures more effectively evil.

There are two traditions in moral education that can be construed as different responses to the problem of intrinsic motivation. There is the formal, rationalist tradition according to which the ultimate questions of what to do are a matter of reason, or rational coherence in the body of evaluative judgments. But there is a corresponding empiricist tradition, according to which there is a source of empirical data about value, something which also supplies the appropriate motivation to act.

7. The Rationalist Response to the Problem of Intrinsic Motivation

Kant famously espoused the principle of universalizability: that a moral judgment is legitimate only if one can consistently will a corresponding universal maxim. 7 A judgment fails the test if willing the corresponding maxim involves willing conditions that make it impossible to apply the maxim. Cheating to gain an unfair advantage is wrong, on this account, because one cannot rationally will that everyone cheat to gain an unfair advantage. To be able to gain an unfair advantage by cheating, others have to play by the rules. So, cheating involves a violation of reason. If this idea can be generalized, and value grounded in reason, then perhaps we don't need to posit queer value facts (that cheating is bad , say) that mysteriously impact our desires upon acquaintance. Value would reduce to nonmysterious facts about rationality.

This rationalist approach, broadly construed, informs a range of educational value theories—for example, those of Hare and Kohlberg, as well as of the “values clarification” theorists. 8 They share the idea that values education is not a matter of teaching substantive value judgments but, rather, of teaching constraints of rationality, like those of logic, critical thinking, and universalizability. They differ in the extent to which they think rational constraints yield substantive evaluative content. Kant apparently held that universalizability settles our moral obligations. Others, like Hare, held that universalizability settles some issues (some moral judgments are just inconsistent with universalizability) while leaving open a range of coherent moral stances, any of which is just as consistent with reason as another. What's attractive about the rationalist tradition is that it limits the explicit teaching of value content to the purely cognitive values demanded by reason alone—those already embedded in the educational enterprise—without invoking additional problematic value facts.

There are two problems with rationalism. First, despite the initial appearance, it too presupposes evaluative facts. If cognitive values necessarily motivate—for example, learning that a maxim is inconsistent necessarily induces an aversion to acting on it—then the queerness objection kicks in. And if cognitive values don't necessarily motivate, then there will be the familiar disconnect between acquaintance with value and motivation.

Second, rational constraints, including even universalizability, leave open a vast range of substantive positions on value. A Kantian's inviolable moral principle—it is always wrong intentionally to kill an innocent person, say—may satisfy universalizability. But so, too, does the act‐utilitarian's injunction to always and everywhere maximize value. If killing innocent people is bad, then it is better to kill one innocent person to prevent a larger number being killed than it is to refrain from killing the one and allowing the others to be killed. The nihilist says it doesn't matter how many people you kill, and this, too, satisfies universalizability. The radical divergence in the recommendation of sundry universalizable theories suggests that rational constraints are too weak to supply substantive evaluative content. Reason leaves open a vast space of mutually incompatible evaluative schemes.