Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

This topic will provide an overview of major issues related to breech presentation, including choosing the best route for delivery. Techniques for breech delivery, with a focus on the technique for vaginal breech delivery, are discussed separately. (See "Delivery of the singleton fetus in breech presentation" .)

TYPES OF BREECH PRESENTATION

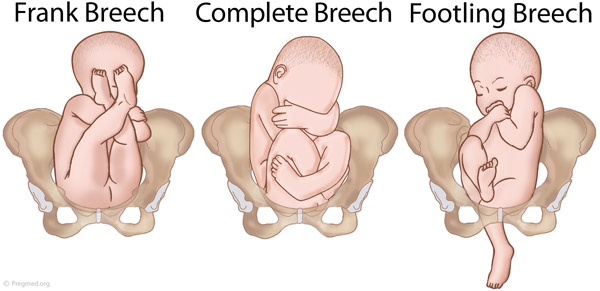

● Frank breech – Both hips are flexed and both knees are extended so that the feet are adjacent to the head ( figure 1 ); accounts for 50 to 70 percent of breech fetuses at term.

● Complete breech – Both hips and both knees are flexed ( figure 2 ); accounts for 5 to 10 percent of breech fetuses at term.

Breech presentation: diagnosis and management

Key messages.

- All women with a breech presentation should be offered an external cephalic version (ECV) from 37 weeks, if there are no contraindications.

- Elective caesarean section (ELCS) for a singleton breech at term has been shown to reduce perinatal and neonatal mortality rates.

- Planning for vaginal breech birth requires careful assessment of suitability criteria, contraindications and the ability of the service to provide experienced personnel.

In June 2023, we commenced a project to review and update the Maternity and Neonatal eHandbook guidelines, with a view to targeting completion in 2024. Please be aware that pending this review, some of the current guidelines may be out of date. In the meantime, we recommend that you also refer to more contemporaneous evidence.

Breech and external cephalic version

Breech presentation is when the fetus is lying longitudinally and its buttocks, foot or feet are presenting instead of its head.

Figure 1. Breech presentations

- Breech presentation occurs in three to four per cent of term deliveries and is more common in nulliparous women.

- External cephalic version (ECV) from 37 weeks has been shown to decrease the incidence of breech presentation at term and the subsequent elective caesarean section (ELCS) rate.

- Vaginal breech birth increases the risk of low Apgar scores and more serious short-term complications, but evidence has not shown an increase in long-term morbidity.

- Emergency caesarean section (EMCS) is needed in approximately 40 per cent of women planning a vaginal breech birth.

- 0.5/1000 with ELCS for breech >39 weeks gestation

- 2.0/1000 planned vaginal breech birth >39/40

- 1.0/1000 with planned cephalic birth.

- A reduction in planned vaginal breech birth followed publication of the Term Breech Trial (TBT) in 2001.

- Acquisition of skills necessary to manage breech presentation (for example, ECV) is important to optimise outcomes.

Clinical suspicion of breech presentation

- Abdominal palpation: if the presenting part is irregular and not ballotable or if the fetal head is ballotable at the fundus

- Pelvic examination: head not felt in the pelvis

- Cord prolapse

- Very thick meconium after rupture of membranes

- Fetal heart heard higher in the abdomen

In cases of extended breech, the breech may not be ballotable and the fetal heart may be heard in the same location as expected for a cephalic presentation.

If breech presentation is suspected, an ultrasound examination will confirm diagnosis.

Cord prolapse is an obstetric emergency. Urgent delivery is indicated after confirming gestation and fetal viability.

Diagnosis: preterm ≤36+6 weeks

- Breech presentation is a normal finding in preterm pregnancy.

- If diagnosed at the 35-36 week antenatal visit, refer the woman for ultrasound scan to enable assessment prior to ECV.

- Mode of birth in a breech preterm delivery depends on the clinical circumstances.

Diagnosis: ≥37+0 weeks

- determine type of breech presentation

- determine extension/flexion of fetal head

- locate position of placenta and exclude placenta praevia

- exclude fetal congenital abnormality

- calculate amniotic fluid index

- estimate fetal weight.

Practice points

- Offer ECV if there are no contraindications.

- If ECV is declined or unsuccessful, provide counselling on risks and benefits of a planned vaginal birth versus an ELCS.

- Inform the woman that there are fewer maternal complications with a successful vaginal birth, however the risk to the woman increases significantly if there is a need for an EMCS.

- Inform the woman that caesarean section increases the risk of complication in future pregnancies, including the risk of a repeat caesarean section and the risk of invasive placentation.

- If the woman chooses an ELCS, document consent and organise booking for 39 weeks gestation.

Information and decision making

Women with a breech presentation should have the opportunity to make informed decisions about their care and treatment, in partnership with the clinicians providing care.

Planning for birth requires careful assessment for risk of poor outcomes relating to planned vaginal breech birth. If any risk factors are identified, inform the woman that an ELCS is recommended due to increased perinatal risk.

Good communication between clinicians and women is essential. Treatment, care and information provided should:

- take into account women's individual needs and preferences

- be supported by evidence-based, written information tailored to the needs of the individual woman

- be culturally appropriate

- be accessible to women, their partners, support people and families

- take into account any specific needs, such as physical or cognitive disabilities or limitations to their ability to understand spoken or written English.

Documentation

The following should be documented in the woman's hospital medical record and (where applicable) in her hand-held medical record:

- discussion of risks and benefits of vaginal breech birth and ELCS

- discussion of the woman's questions about planned vaginal breech birth and ELCS

- discussion of ECV, if applicable

- consultation, referral and escalation

External cephalic version (ECV)

- ECV can be offered from 37 weeks gestation

- The woman must provide written consent prior to the procedure

- The success rate of ECV is 40-60 per cent

- Approximately one in 200 ECV attempts will lead to EMCS

- ECV should only be performed by a suitably trained, experienced clinician

- continuous electronic fetal monitoring (EFM)

- capability to perform an EMCS.

Contraindications

Table 1. Contraindications to ECV

Precautions

- Hypertension

- Oligohydramnios

- Nuchal cord

Escalate care to a consultant obstetrician if considering ECV in these circumstances.

- Perform a CTG prior to the procedure - continue until RANZCOG criteria for a normal antenatal CTG are met.

- 250 microg s/c, 30 minutes prior to the procedure.

- Administer Anti-D immunoglobulin if the woman is rhesus negative.

- Do not make more than four attempts at ECV, for a suggested maximum time of ten minutes in total.

- Undertake CTG monitoring post-procedure until RANZCOG criteria for a normal antenatal CTG are met.

Emergency management

Urgent delivery is indicated in the event of the following complications:

- abnormal CTG

- vaginal bleeding

- unexplained pain.

Initiate emergency response as per local guidelines.

Alternatives to ECV

There is a lack of evidence to support the use of moxibustion, acupuncture or postural techniques to achieve a vertex presentation after 35 weeks gestation.

Criteria for a planned vaginal breech birth

- Documented evidence of counselling regarding mode of birth

- Documentation of informed consent, including written consent from the woman

- Estimated fetal weight of 2500-4000g

- Flexed fetal head

- Emergency theatre facilities available on site

- Availability of suitably skilled healthcare professional

- Frank or complete breech presentation

- No previous caesarean section.

- Cord presentation

- Fetal growth restriction or macrosomia

- Any presentation other than a frank or complete breech

- Extension of the fetal head

- Fetal anomaly incompatible with vaginal delivery

- Clinically inadequate maternal pelvis

- Previous caesarean section

- Inability of the service to provide experienced personnel.

If an ELCS is booked

- Confirm presentation by ultrasound scan when a woman presents for ELCS.

- If fetal presentation is cephalic on admission for ELCS, plan ongoing management with the woman.

Intrapartum management

Fetal monitoring.

- Advise the woman that continuous EFM may lead to improved neonatal outcomes.

- Where continuous EFM is declined, perform intermittent EFM or intermittent auscultation, with conversion to EFM if an abnormality is detected.

- A fetal scalp electrode can be applied to the breech.

Position of the woman

- The optimal maternal position for birth is upright.

- Lithotomy may be appropriate, depending on the accoucheur's training and experience.

Pain relief

- Epidural analgesia may increase the risk of intervention with a vaginal breech birth.

- Epidural analgesia may impact on the woman's ability to push spontaneously in the second stage of labour.

Induction of labour (IOL)

See the IOL eHandbook page for more detail.

- IOL may be offered if clinical circumstances are favourable and the woman wishes to have a vaginal birth.

- Augmentation (in the absence of an epidural) should be avoided as adequate progress in the absence of augmentation may be the best indicator of feto-pelvic proportions.

The capacity to offer IOL will depend on clinician experience and availability and service capability.

First stage

- Manage with the same principles as a cephalic presentation.

- Labour should be expected to progress as for a cephalic presentation.

- If progress in the first stage is slow, consider a caesarean section.

- If an epidural is in situ and contractions are less than 4:10, consult with a senior obstetrician.

- Avoid routine amniotomy to avoid the risk of cord prolapse or cord compression.

Second stage

- Allow passive descent of the breech to the perineum prior to active pushing.

- If breech is not visible within one hour of passive descent, a caesarean section is normally recommended.

- Active second stage should be ½ hour for a multigravida and one hour for a primipara.

- All midwives and obstetricians should be familiar with the techniques and manoeuvres required to assist a vaginal breech birth.

- Ensure a consultant obstetrician is present for birth.

- Ensure a senior paediatric clinician is present for birth.

VIDEO: Maternity Training International - Vaginal Breech Birth

- Encouragement of maternal pushing (if at all) should not begin until the presenting part is visible.

- A hands-off approach is recommended.

- Significant cord compression is common once buttocks have passed the perineum.

- Timely intervention is recommended if there is slow progress once the umbilicus has delivered.

- Allow spontaneous birth of the trunk and limbs by maternal effort as breech extraction can cause extension of the arms and head.

- Grasp the fetus around the bony pelvic girdle, not soft tissue, to avoid trauma.

- Assist birth if there is a delay of more than five minutes from delivery of the buttocks to the head, or of more than three minutes from the umbilicus to the head.

- Signs that delivery should be expedited also include lack of tone or colour or sign of poor fetal condition.

- Ensure fetal back remains in the anterior position.

- Routine episiotomy not recommended.

- Lovset's manoeuvre for extended arms.

- Reverse Lovset's manoeuvre may be used to reduce nuchal arms.

- Supra-pubic pressure may aide flexion of the fetal head.

- Maricueau-Smellie-Veit manoeuvre or forceps may be used to deliver the after coming head.

Undiagnosed breech in labour

- This occurs in approximately 25 per cent of breech presentations.

- Management depends on the stage of labour when presenting.

- Assessment is required around increased complications, informed consent and suitability of skilled expertise.

- Do not routinely offer caesarean section to women in active second stage.

- If there is no senior obstetrician skilled in breech delivery, an EMCS is the preferred option.

- If time permits, a detailed ultrasound scan to estimate position of fetal neck and legs and estimated fetal weight should be made and the woman counselled.

Entrapment of the fetal head

This is an extreme emergency

This complication is often due to poor selection for vaginal breech birth.

- A vaginal examination (VE) should be performed to ensure that the cervix is fully dilated.

- If a lip of cervix is still evident try to push the cervix over the fetal head.

- If the fetal head has entered the pelvis, perform the Mauriceau-Smellie-Veit manoeuvre combined with suprapubic pressure from a second attendant in a direction that maintains flexion and descent of the fetal head.

- Rotate fetal body to a lateral position and apply suprapubic pressure to flex the fetal head; if unsuccessful consider alternative manoeuvres.

- Reassess cervical dilatation; if not fully dilated consider Duhrssen incision at 2, 10 and 6 o'clock.

- A caesarean section may be performed if the baby is still alive.

Neonatal management

- Paediatric review.

- Routine observations as per your local guidelines, recorded on a track and trigger chart.

- Observe for signs of jaundice.

- Observe for signs of tissue or nerve damage.

- Hip ultrasound scan to be performed at 6-12 weeks post birth to monitor for developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH). See Neonatal eHandbook - Developmental dysplasia of the hip .

More information

Audit and performance improvement.

All maternity services should have processes in place for:

- auditing clinical practice and outcomes

- providing feedback to clinicians on audit results

- addressing risks, if identified

- implementing change, if indicated.

Potential auditable standards are:

- number of women with a breech presentation offered ECV

- success rate of ECV

- ECV complications

- rate of planned vaginal breech birth

- breech birth outcomes for vaginal and caesarean birth.

For more information or assistance with auditing, please contact us via [email protected]

- Bue and Lauszus 2016, Moxibustion did not have an effect in a randomised clinical trial for version of breech position. Danish Medical Journal 63(2), A599

- Coulon et.al. 2014, Version of breech fetuses by moxibustion with acupuncture. Obstetrics and Gynecology 124(1), 32-39. DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000303

- Coyle ME, Smith CA, Peat B 2012, Cephalic version by moxibustion for breech presentation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 5. Art. No.: CD003928. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003928.pub3

- Evans J 2012, Essentially MIDIRS Understanding Physiological Breech Birth Volume 3. Number 2. February 2012

- Hoffmann J, Thomassen K, Stumpp P, Grothoff M, Engel C, Kahn T, et al. 2016, New MRI Criteria for Successful Vaginal Breech Delivery in Primiparae. PLoS ONE 11(8): e0161028. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0161028

- Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R 2012, Cephalic version by postural management for breech presentation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 10. Art. No.: CD000051. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000051.pub2

- New South Wales Department of Health 2013, Maternity: Management of Breech Presentation HNELHD CG 13_01, NSW Government; 2013

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2017, External Cephalic Version and Reducing the Incidence of Term Breech Presentation. Green-top Guideline No. 20a . London: RCOG; 2017

- The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) 2016, Management of breech presentation at term , July 2016 C-Obs-11:

- The Royal Women's Hospital 2015, Management of Breech - Clinical Guideline

- Women's and Newborn Health Service, King Edward Memorial Hospital 2015, Complications of Pregnancy Breech Presentation

Abbreviations

Get in touch, version history.

First published: November 2018 Due for review: November 2021

Uncontrolled when downloaded

Related links.

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

What Is Breech?

When a fetus is delivered buttocks or feet first

- Types of Presentation

Risk Factors

Complications.

Breech concerns the position of the fetus before labor . Typically, the fetus comes out headfirst, but in a breech delivery, the buttocks or feet come out first. This type of delivery is risky for both the pregnant person and the fetus.

This article discusses the different types of breech presentations, risk factors that might make a breech presentation more likely, treatment options, and complications associated with a breech delivery.

Verywell / Jessica Olah

Types of Breech Presentation

During the last few weeks of pregnancy, a fetus usually rotates so that the head is positioned downward to come out of the vagina first. This is called the vertex position.

In a breech presentation, the fetus does not turn to lie in the correct position. Instead, the fetus’s buttocks or feet are positioned to come out of the vagina first.

At 28 weeks of gestation, approximately 20% of fetuses are in a breech position. However, the majority of these rotate to the proper vertex position. At full term, around 3%–4% of births are breech.

The different types of breech presentations include:

- Complete : The fetus’s knees are bent, and the buttocks are presenting first.

- Frank : The fetus’s legs are stretched upward toward the head, and the buttocks are presenting first.

- Footling : The fetus’s foot is showing first.

Signs of Breech

There are no specific symptoms associated with a breech presentation.

Diagnosing breech before the last few weeks of pregnancy is not helpful, since the fetus is likely to turn to the proper vertex position before 35 weeks gestation.

A healthcare provider may be able to tell which direction the fetus is facing by touching a pregnant person’s abdomen. However, an ultrasound examination is the best way to determine how the fetus is lying in the uterus.

Most breech presentations are not related to any specific risk factor. However, certain circumstances can increase the risk for breech presentation.

These can include:

- Previous pregnancies

- Multiple fetuses in the uterus

- An abnormally shaped uterus

- Uterine fibroids , which are noncancerous growths of the uterus that usually appear during the childbearing years

- Placenta previa, a condition in which the placenta covers the opening to the uterus

- Preterm labor or prematurity of the fetus

- Too much or too little amniotic fluid (the liquid that surrounds the fetus during pregnancy)

- Fetal congenital abnormalities

Most fetuses that are breech are born by cesarean delivery (cesarean section or C-section), a surgical procedure in which the baby is born through an incision in the pregnant person’s abdomen.

In rare instances, a healthcare provider may plan a vaginal birth of a breech fetus. However, there are more risks associated with this type of delivery than there are with cesarean delivery.

Before cesarean delivery, a healthcare provider might utilize the external cephalic version (ECV) procedure to turn the fetus so that the head is down and in the vertex position. This procedure involves pushing on the pregnant person’s belly to turn the fetus while viewing the maneuvers on an ultrasound. This can be an uncomfortable procedure, and it is usually done around 37 weeks gestation.

ECV reduces the risks associated with having a cesarean delivery. It is successful approximately 40%–60% of the time. The procedure cannot be done once a pregnant person is in active labor.

Complications related to ECV are low and include the placenta tearing away from the uterine lining, changes in the fetus’s heart rate, and preterm labor.

ECV is usually not recommended if the:

- Pregnant person is carrying more than one fetus

- Placenta is in the wrong place

- Healthcare provider has concerns about the health of the fetus

- Pregnant person has specific abnormalities of the reproductive system

Recommendations for Previous C-Sections

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) says that ECV can be considered if a person has had a previous cesarean delivery.

During a breech delivery, the umbilical cord might come out first and be pinched by the exiting fetus. This is called cord prolapse and puts the fetus at risk for decreased oxygen and blood flow. There’s also a risk that the fetus’s head or shoulders will get stuck inside the mother’s pelvis, leading to suffocation.

Complications associated with cesarean delivery include infection, bleeding, injury to other internal organs, and problems with future pregnancies.

A healthcare provider needs to weigh the risks and benefits of ECV, delivering a breech fetus vaginally, and cesarean delivery.

In a breech delivery, the fetus comes out buttocks or feet first rather than headfirst (vertex), the preferred and usual method. This type of delivery can be more dangerous than a vertex delivery and lead to complications. If your baby is in breech, your healthcare provider will likely recommend a C-section.

A Word From Verywell

Knowing that your baby is in the wrong position and that you may be facing a breech delivery can be extremely stressful. However, most fetuses turn to have their head down before a person goes into labor. It is not a cause for concern if your fetus is breech before 36 weeks. It is common for the fetus to move around in many different positions before that time.

At the end of your pregnancy, if your fetus is in a breech position, your healthcare provider can perform maneuvers to turn the fetus around. If these maneuvers are unsuccessful or not appropriate for your situation, cesarean delivery is most often recommended. Discussing all of these options in advance can help you feel prepared should you be faced with a breech delivery.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. If your baby is breech .

TeachMeObGyn. Breech presentation .

MedlinePlus. Breech birth .

Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R, West HM. External cephalic version for breech presentation at term . Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2015 Apr 1;2015(4):CD000083. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000083.pub3

By Christine Zink, MD Dr. Zink is a board-certified emergency medicine physician with expertise in the wilderness and global medicine.

Breech baby at the end of pregnancy

Published: July 2017

Please note that this information will be reviewed every 3 years after publication.

This patient information page provides advice if your baby is breech towards the end of pregnancy and the options available to you.

It may also be helpful if you are a partner, relative or friend of someone who is in this situation.

The information here aims to help you better understand your health and your options for treatment and care. Your healthcare team is there to support you in making decisions that are right for you. They can help by discussing your situation with you and answering your questions.

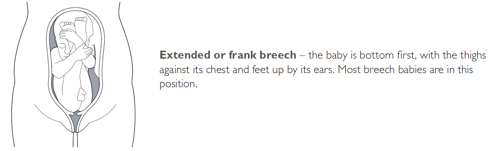

This information is for you if your baby remains in the breech position after 36 weeks of pregnancy. Babies lying bottom first or feet first in the uterus (womb) instead of in the usual head-first position are called breech babies.

This information includes:

- What breech is and why your baby may be breech

- The different types of breech

- The options if your baby is breech towards the end of your pregnancy

- What turning a breech baby in the uterus involves (external cephalic version or ECV)

- How safe ECV is for you and your baby

- Options for birth if your baby remains breech

- Other information and support available

Within this information, we may use the terms ‘woman’ and ‘women’. However, it is not only people who identify as women who may want to access this information. Your care should be personalised, inclusive and sensitive to your needs, whatever your gender identity.

A glossary of medical terms is available at A-Z of medical terms .

- Breech is very common in early pregnancy, and by 36–37 weeks of pregnancy most babies will turn into the head-first position. If your baby remains breech, it does not usually mean that you or your baby have any problems.

- Turning your baby into the head-first position so that you can have a vaginal delivery is a safe option.

- The alternative to turning your baby into the head-first position is to have a planned caesarean section or a planned vaginal breech birth.

Babies lying bottom first or feet first in the uterus (womb) instead of in the usual head-first position are called breech babies. Breech is very common in early pregnancy, and by 36-37 weeks of pregnancy, most babies turn naturally into the head-first position.

Towards the end of pregnancy, only 3-4 in every 100 (3-4%) babies are in the breech position.

A breech baby may be lying in one of the following positions:

It may just be a matter of chance that your baby has not turned into the head-first position. However, there are certain factors that make it more difficult for your baby to turn during pregnancy and therefore more likely to stay in the breech position. These include:

- if this is your first pregnancy

- if your placenta is in a low-lying position (also known as placenta praevia); see the RCOG patient information Placenta praevia, placenta accreta and vasa praevia

- if you have too much or too little fluid ( amniotic fluid ) around your baby

- if you are having more than one baby.

Very rarely, breech may be a sign of a problem with the baby. If this is the case, such problems may be picked up during the scan you are offered at around 20 weeks of pregnancy.

If your baby is breech at 36 weeks of pregnancy, your healthcare professional will discuss the following options with you:

- trying to turn your baby in the uterus into the head-first position by external cephalic version (ECV)

- planned caesarean section

- planned vaginal breech birth.

What does ECV involve?

ECV involves applying gentle but firm pressure on your abdomen to help your baby turn in the uterus to lie head-first.

Relaxing the muscle of your uterus with medication has been shown to improve the chances of turning your baby. This medication is given by injection before the ECV and is safe for both you and your baby. It may make you feel flushed and you may become aware of your heart beating faster than usual but this will only be for a short time.

Before the ECV you will have an ultrasound scan to confirm your baby is breech, and your pulse and blood pressure will be checked. After the ECV, the ultrasound scan will be repeated to see whether your baby has turned. Your baby’s heart rate will also be monitored before and after the procedure. You will be advised to contact the hospital if you have any bleeding, abdominal pain, contractions or reduced fetal movements after ECV.

ECV is usually performed after 36 or 37 weeks of pregnancy. However, it can be performed right up until the early stages of labour. You do not need to make any preparations for your ECV.

ECV can be uncomfortable and occasionally painful but your healthcare professional will stop if you are experiencing pain and the procedure will only last for a few minutes. If your healthcare professional is unsuccessful at their first attempt in turning your baby then, with your consent, they may try again on another day.

If your blood type is rhesus D negative, you will be advised to have an anti-D injection after the ECV and to have a blood test. See the NICE patient information Routine antenatal anti-D prophylaxis for women who are rhesus D negative , which is available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta156/informationforpublic .

Why turn my baby head-first?

If your ECV is successful and your baby is turned into the head-first position you are more likely to have a vaginal birth. Successful ECV lowers your chances of requiring a caesarean section and its associated risks.

Is ECV safe for me and my baby?

ECV is generally safe with a very low complication rate. Overall, there does not appear to be an increased risk to your baby from having ECV. After ECV has been performed, you will normally be able to go home on the same day.

When you do go into labour, your chances of needing an emergency caesarean section, forceps or vacuum (suction cup) birth is slightly higher than if your baby had always been in a head-down position.

Immediately after ECV, there is a 1 in 200 chance of you needing an emergency caesarean section because of bleeding from the placenta and/or changes in your baby’s heartbeat.

ECV should be carried out by a doctor or a midwife trained in ECV. It should be carried out in a hospital where you can have an emergency caesarean section if needed.

ECV can be carried out on most women, even if they have had one caesarean section before.

ECV should not be carried out if:

- you need a caesarean section for other reasons, such as placenta praevia; see the RCOG patient information Placenta praevia, placenta accreta and vasa praevia

- you have had recent vaginal bleeding

- your baby’s heart rate tracing (also known as CTG) is abnormal

- your waters have broken

- you are pregnant with more than one baby; see the RCOG patient information Multiple pregnancy: having more than one baby .

Is ECV always successful?

ECV is successful for about 50% of women. It is more likely to work if you have had a vaginal birth before. Your healthcare team should give you information about the chances of your baby turning based on their assessment of your pregnancy.

If your baby does not turn then your healthcare professional will discuss your options for birth (see below). It is possible to have another attempt at ECV on a different day.

If ECV is successful, there is still a small chance that your baby will turn back to the breech position. However, this happens to less than 5 in 100 (5%) women who have had a successful ECV.

There is no scientific evidence that lying down or sitting in a particular position can help your baby to turn. There is some evidence that the use of moxibustion (burning a Chinese herb called mugwort) at 33–35 weeks of pregnancy may help your baby to turn into the head-first position, possibly by encouraging your baby’s movements. This should be performed under the direction of a registered healthcare practitioner.

Depending on your situation, your choices are:

There are benefits and risks associated with both caesarean section and vaginal breech birth, and these should be discussed with you so that you can choose what is best for you and your baby.

Caesarean section

If your baby remains breech towards the end of pregnancy, you should be given the option of a caesarean section. Research has shown that planned caesarean section is safer for your baby than a vaginal breech birth. Caesarean section carries slightly more risk for you than a vaginal birth.

Caesarean section can increase your chances of problems in future pregnancies. These may include placental problems, difficulty with repeat caesarean section surgery and a small increase in stillbirth in subsequent pregnancies. See the RCOG patient information Choosing to have a caesarean section .

If you choose to have a caesarean section but then go into labour before your planned operation, your healthcare professional will examine you to assess whether it is safe to go ahead. If the baby is close to being born, it may be safer for you to have a vaginal breech birth.

Vaginal breech birth

After discussion with your healthcare professional about you and your baby’s suitability for a breech delivery, you may choose to have a vaginal breech birth. If you choose this option, you will need to be cared for by a team trained in helping women to have breech babies vaginally. You should plan a hospital birth where you can have an emergency caesarean section if needed, as 4 in 10 (40%) women planning a vaginal breech birth do need a caesarean section. Induction of labour is not usually recommended.

While a successful vaginal birth carries the least risks for you, it carries a small increased risk of your baby dying around the time of delivery. A vaginal breech birth may also cause serious short-term complications for your baby. However, these complications do not seem to have any long-term effects on your baby. Your individual risks should be discussed with you by your healthcare team.

Before choosing a vaginal breech birth, it is advised that you and your baby are assessed by your healthcare professional. They may advise against a vaginal birth if:

- your baby is a footling breech (one or both of the baby’s feet are below its bottom)

- your baby is larger or smaller than average (your healthcare team will discuss this with you)

- your baby is in a certain position, for example, if its neck is very tilted back (hyper extended)

- you have a low-lying placenta (placenta praevia); see the RCOG patient information Placenta Praevia, placenta accreta and vasa praevia

- you have pre-eclampsia or any other pregnancy problems; see the RCOG patient information Pre-eclampsia .

With a breech baby you have the same choices for pain relief as with a baby who is in the head-first position. If you choose to have an epidural, there is an increased chance of a caesarean section. However, whatever you choose, a calm atmosphere with continuous support should be provided.

If you have a vaginal breech birth, your baby’s heart rate will usually be monitored continuously as this has been shown to improve your baby’s chance of a good outcome.

In some circumstances, for example, if there are concerns about your baby’s heart rate or if your labour is not progressing, you may need an emergency caesarean section during labour. A paediatrician (a doctor who specialises in the care of babies, children and teenagers) will attend the birth to check your baby is doing well.

If you go into labour before 37 weeks of pregnancy, the balance of the benefits and risks of having a caesarean section or vaginal birth changes and will be discussed with you.

If you are having twins and the first baby is breech, your healthcare professional will usually recommend a planned caesarean section.

If, however, the first baby is head-first, the position of the second baby is less important. This is because, after the birth of the first baby, the second baby has lots more room to move. It may turn naturally into a head-first position or a doctor may be able to help the baby to turn. See the RCOG patient information Multiple pregnancy: having more than one baby .

If you would like further information on breech babies and breech birth, you should speak with your healthcare professional.

Further information

- NHS information on breech babies

- NCT information on breech babies

If you are asked to make a choice, you may have lots of questions that you want to ask. You may also want to talk over your options with your family or friends. It can help to write a list of the questions you want answered and take it to your appointment.

Ask 3 Questions

To begin with, try to make sure you get the answers to 3 key questions , if you are asked to make a choice about your healthcare:

- What are my options?

- What are the pros and cons of each option for me?

- How do I get support to help me make a decision that is right for me?

*Ask 3 Questions is based on Shepherd et al. Three questions that patients can ask to improve the quality of information physicians give about treatment options: A cross-over trial. Patient Education and Counselling, 2011;84:379-85

- https://aqua.nhs.uk/resources/shared-decision-making-case-studies/

Sources and acknowledgements

This information has been developed by the RCOG Patient Information Committee. It is based on the RCOG Green-top Clinical Guidelines No. 20a External Cephalic Version and Reducing Incidence of Term Breech Presentation and No. 20b Management of Breech Presentation . The guidelines contain a full list of the sources of evidence we have used.

This information was reviewed before publication by women attending clinics in Nottingham, Essex, Inverness, Manchester, London, Sussex, Bristol, Basildon and Oxford, by the RCOG Women’s Network and by the RCOG Women’s Voices Involvement Panel.

Please give us feedback by completing our feedback survey:

- Members of the public – patient information feedback

- Healthcare professionals – patient information feedback

External Cephalic Version and Reducing the Incidence of Term Breech Presentation Green-top Guideline

Management of Breech Presentation Green-top Guideline

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.16(4); 2019 Apr

Screening for breech presentation using universal late-pregnancy ultrasonography: A prospective cohort study and cost effectiveness analysis

David wastlund.

1 Cambridge Centre for Health Services Research, Cambridge Institute of Public Health, Cambridge, United Kingdom

2 The Primary Care Unit, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Alexandros A. Moraitis

3 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Cambridge, NIHR Cambridge Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Alison Dacey

Edward c. f. wilson.

4 Health Economics Group, Norwich Medical School, University of East Anglia, Norwich, United Kingdom

Gordon C. S. Smith

Associated data.

The terms of the ethical permission for the POP study do not allow publication of individual patient level data. Requests for access to patient level data will usually require a Data Transfer Agreement, and should be made to Mrs Sheree Green-Molloy at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Cambridge University, UK ( ku.ca.mac.lhcsdem@dohgdnaoap ).

Despite the relative ease with which breech presentation can be identified through ultrasound screening, the assessment of foetal presentation at term is often based on clinical examination only. Due to limitations in this approach, many women present in labour with an undiagnosed breech presentation, with increased risk of foetal morbidity and mortality. This study sought to determine the cost effectiveness of universal ultrasound scanning for breech presentation near term (36 weeks of gestational age [wkGA]) in nulliparous women.

Methods and findings

The Pregnancy Outcome Prediction (POP) study was a prospective cohort study between January 14, 2008 and July 31, 2012, including 3,879 nulliparous women who attended for a research screening ultrasound examination at 36 wkGA. Foetal presentation was assessed and compared for the groups with and without a clinically indicated ultrasound. Where breech presentation was detected, an external cephalic version (ECV) was routinely offered. If the ECV was unsuccessful or not performed, the women were offered either planned cesarean section at 39 weeks or attempted vaginal breech delivery. To compare the likelihood of different mode of deliveries and associated long-term health outcomes for universal ultrasound to current practice, a probabilistic economic simulation model was constructed. Parameter values were obtained from the POP study, and costs were mainly obtained from the English National Health Service (NHS). One hundred seventy-nine out of 3,879 women (4.6%) were diagnosed with breech presentation at 36 weeks. For most women (96), there had been no prior suspicion of noncephalic presentation. ECV was attempted for 84 (46.9%) women and was successful in 12 (success rate: 14.3%). Overall, 19 of the 179 women delivered vaginally (10.6%), 110 delivered by elective cesarean section (ELCS) (61.5%) and 50 delivered by emergency cesarean section (EMCS) (27.9%). There were no women with undiagnosed breech presentation in labour in the entire cohort. On average, 40 scans were needed per detection of a previously undiagnosed breech presentation. The economic analysis indicated that, compared to current practice, universal late-pregnancy ultrasound would identify around 14,826 otherwise undiagnosed breech presentations across England annually. It would also reduce EMCS and vaginal breech deliveries by 0.7 and 1.0 percentage points, respectively: around 4,196 and 6,061 deliveries across England annually. Universal ultrasound would also prevent 7.89 neonatal mortalities annually. The strategy would be cost effective if foetal presentation could be assessed for £19.80 or less per woman. Limitations to this study included that foetal presentation was revealed to all women and that the health economic analysis may be altered by parity.

Conclusions

According to our estimates, universal late pregnancy ultrasound in nulliparous women (1) would virtually eliminate undiagnosed breech presentation, (2) would be expected to reduce foetal mortality in breech presentation, and (3) would be cost effective if foetal presentation could be assessed for less than £19.80 per woman.

In their cohort study, David Wastlund and colleagues find that universal ultrasound scanning for breech presentation near term is associated with reduced undiagnosed breech presentation and improved pregnancy outcomes, and can be cost-effective.

Author summary

Why was this study done.

- Risks of complications at delivery are higher for babies that are in a breech position, but sometimes breech presentation is not discovered until the time of birth.

- Ultrasound screening could be used to detect breech presentation before birth and lower the risk of complications but would be associated with additional costs.

- It is uncertain if offering ultrasound screening to every pregnancy is cost effective.

What did the researchers do and find?

- This study recorded the birth outcomes of pregnancies that were all screened using ultrasound.

- Economic modelling and simulation was used to compare these outcomes with those if ultrasound screening had not been used.

- Modelling demonstrated that ultrasound screening would lower the risk of breech delivery and, as a result, reduce emergency cesarean sections and the baby’s risk of death.

What do these findings mean?

- Offering ultrasound screening to every pregnancy would improve the health of mothers and babies nationwide.

- Whether the health improvements are enough to justify the increased cost of ultrasound screening is still uncertain, mainly because the cost of ultrasound screening for presentation alone is unknown.

- If ultrasound screening could be provided sufficiently inexpensively, for example, by being used during standard midwife appointments, routinely offering ultrasound screening would be worthwhile.

Introduction

Undiagnosed breech presentation in labour increases the risk of perinatal morbidity and mortality and represents a challenge for obstetric management. The incidence of breech presentation at term is around 3%–4% [ 1 – 3 ], and fewer than 10% of foetuses who are breech at term revert spontaneously to a vertex presentation [ 4 ]. Although breech presentation is easy to detect through ultrasound screening, many women go into labour with an undetected breech presentation [ 5 ]. The majority of these women will deliver through emergency cesarean section (EMCS), which has high costs and increased risk of morbidity and mortality for both mother and child.

In current practice, foetal presentation is routinely assessed by palpation of the maternal abdomen by a midwife, obstetrician, or general practitioner. The sensitivity of abdominal palpation varies between studies (range: 57%–70%) and depends on the skill and experience of the practitioner [ 6 , 7 ]. There is currently no guidance on what is considered an acceptable false negative rate when screening for breech presentation using abdominal palpation. In contrast, ultrasound examination provides a quick and safe method of accurately identifying foetal presentation.

Effective interventions exist for the care of women who have breech presentation diagnosed near term. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recommends ‘that all women with an uncomplicated breech presentation at term should be offered external cephalic version (ECV)’ [ 2 ]. The rationale for this is to reduce the incidence of breech presentation at term and avoid the risks of vaginal breech birth or cesarean section. The success rate of ECV is considered to be approximately 50% [ 2 , 8 , 9 ], but it differs greatly between nulliparous and parous women (34% and 66%, respectively) [ 9 ]. ECV is overall safe, with less than 1% risk to the foetus and even smaller risk to the mother [ 10 ]; despite this, a significant number of women decline ECV for various reasons [ 11 ]. Should ECV be declined or fail, generally women are offered delivery by planned (elective) cesarean section, as there is level 1 evidence of reduced risk of perinatal death and severe morbidity compared with attempting vaginal breech birth, and it is also associated with lower costs [ 3 , 12 , 13 ]. However, some women may still opt for an attempt at vaginal breech birth if they prioritise nonintervention over managing the relatively small absolute risks of a severe adverse event [ 1 , 14 ].

We sought to assess the cost effectiveness of universal late-pregnancy ultrasound presentation scans for nulliparous women. We used data from the Pregnancy Outcome Prediction (POP) study, a prospective cohort study of >4,000 nulliparous women, which included an ultrasound scan at 36 weeks of gestational age (wkGA) [ 15 ]. Here, we report the outcomes for pregnant nulliparous women with breech presentation in the study and use these data to perform a cost effectiveness analysis of universal ultrasound as a screening test for breech presentation.

Study design

The POP study was a prospective cohort study of nulliparous women conducted at the Rosie Hospital, Cambridge (United Kingdom) between January 14, 2008 and July 31, 2012, and the study has been described in detail elsewhere [ 15 – 17 ]. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Cambridgeshire 2 Research Ethics Committee (reference 07/H0308/163), and all participants provided informed consent in writing. Participation in the POP study involved serial phlebotomy and ultrasound at approximately 12 wkGA, 20 wkGA, 28 wkGA, and 36 wkGA [ 16 ]. The outcome of pregnancy was obtained by individual review of all case records by research midwives and by linkage to the hospital’s electronic databases of ultrasonography, biochemical testing, delivery data, and neonatal care data. The research ultrasound at 36 wkGA was performed by sonographers and included presentation, biometry, uteroplacental Doppler, and placental location. The ultrasound findings were blinded except in cases of breech presentation, low lying placenta, or foetal concerns such as newly diagnosed foetal anomaly and an amniotic fluid index (AFI) < 5 cm. This study was not prospectively defined in the POP study protocol paper [ 16 ] but required no further data collection.

If the foetus was in a breech presentation at 36 wkGA, women were counselled by a member of the medical team. In line with guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), ECV was routinely offered unless there was a clinical indication that contraindicated the procedure, e.g., reduced AFI (<5 cm) [ 18 ]. ECV was performed by 1 of 5 obstetric consultants in the unit between 36–38 wkGA, patients were scanned before the procedure to confirm presentation, and it was performed with ultrasound assessment; 0.25 mg terbutaline SC was given prior to the procedure at the discretion of the clinician. If women refused ECV or the procedure failed, the options of vaginal breech delivery and elective cesarean section (ELCS) were discussed and documented. The local guideline for management of breech presentation, including selection criteria for vaginal breech delivery, was based upon recommendations from the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) [ 1 ]. We extracted information about ECV from case records that were individually reviewed by research midwives. Finally, we obtained delivery-related information from our hospital electronic database (Protos; iSoft, Banbury, UK).

Foetal outcomes included mode of delivery (MOD), birth weight, and gestational age at delivery. We used the UK population reference for birthweight, with the 10th and 90th percentile cut-offs for small and large for gestational age, respectively; the centiles were adjusted for sex and gestational age [ 19 ]. Maternal age was defined as age at recruitment. Smoking status, racial ancestry, alcohol consumption, and BMI were taken from data recorded at the booking assessment by the community midwife. Socioeconomic status was quantified using the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2007, which is based on census data from the area in the mother’s postcode [ 20 ]. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Cambridgeshire 2 Research Ethics Committee (reference 07/H0308/163), and all participants provided informed consent in writing.

This study is reported as per the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guideline.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) or n (%), as appropriate. P values are reported for the difference between groups calculated using the two-sample Wilcox rank-sum (Mann–Whitney) test for continuous variables and the Pearson Chi-square test for categorical variables, with trend tests when appropriate. Comparisons were performed using Stata (version 15.1). Missing values were included in the presentation of patient characteristics and outcomes but were excluded from the economic analysis and estimation of parameters.

Economic model and analysis

To evaluate the cost effectiveness of routinely offering late-pregnancy presentation scans, a decision-tree simulation model was constructed using R (version 3.4.1) [ 21 – 24 ]. The time horizon of the economic analysis was from the ultrasound scan (36 wkGA) to infant lifetime, and costs were from the perspective of the English National Health Service (NHS). Costs for modes of delivery were obtained from NHS reference costs [ 25 ]; since these do not list a separate cost for vaginal breech delivery, we assumed that the cost ratio between vaginal breech and ELCS deliveries was the same as in another study (see Supporting information , S1 Text ) [ 12 ].

The population of interest is unselected nulliparous women. The model compares the outcomes at birth for two strategies: ‘universal ultrasound’ and ‘selective ultrasound’ ( Fig 1 ). For universal ultrasound, we assumed that all breech presentations at the time of scanning would be detected (i.e., assumed 100% sensitivity and specificity for the test). For selective ultrasound, the breech presentation was diagnosed either clinically (by abdominal palpation followed by ultrasound for confirmation) or as an incidental finding during a scan for a different indication. These assumptions were based upon current practice and derived from the POP study.

Structure of economic simulation model. ‘Universal ultrasound’ strategy starts in Model A, and patients with breech presentation enter Model C. ‘Selective ultrasound’, i.e., no routine ultrasound, starts in Model B, and only those with a detected breech presentation enter Model C. The letter–number codes for each node are equivalent to the codes in Table 1 . ELCS, elective cesarean section; EMCS, emergency cesarean section.

Compared to a standard antenatal ultrasound for which, typically, multiple measurements are made, an ultrasound scan for foetal presentation alone is technically simple. We theorised that such a scan could be provided by an attending midwife in conjunction with a standard antenatal visit in primary care, using basic ultrasound equipment. Since a specific unit cost for a scan for foetal presentation alone is not included in the national schedule of reference costs [ 25 ], we estimated the cost of ultrasound to include the midwife’s time, the cost of equipment, and room. More details are presented in the Supporting information, S1 Text . The cost of ECV was obtained from James and colleagues [ 26 ] and converted to the 2017 price level using the Hospital and Community Health Services (HCHS) index [ 27 ]. The probability of ECV uptake and success rate as well as MOD were obtained from the POP study. All model inputs are presented in Table 1 and S1 Table , and the calculation of cost inputs is shown in Supporting information, S1 Text .

Abbreviations: CV, cephalic vaginal; ELCS, elective cesarean section; EMCS, emergency cesarean section; MOD, mode of delivery; NHS, National Health Service; POP, Pregnancy Outcome Prediction; SRB, spontaneous reversion to breech; SRC, spontaneous reversion to cephalic; VB, vaginal breech.

Costs given per unit/episode. For probabilities, alpha represent case of event and beta case of no event. MOD shows input values for Dirichlet distribution. Node refers to the chance nodes in Fig 1 .

*Details on how this value was estimated is provided as Supporting information, S1 Text .

†Cost for ECV (high staff cost), converted to 2017 price level using the HCHS index [ 27 ].

‡Weighted average of all complication levels (Total HRGs).

§Due to the small sample size for these parameters in the POP study, the model used inputs for MOD for undetected breech instead.

The end state of the decision tree was the MOD, which was either vaginal, ELCS, or EMCS. Delivery could be either cephalic or breech. EMCS could be either due to previously undiagnosed breech presentation or for other reasons. All cases of breech could spontaneously revert to cephalic presentation. However, we assumed the probability of this to be lower if ECV had been attempted and failed [ 28 ]. If ECV was successful, a reversion back to breech presentation was possible. It is currently unclear whether the probability of MOD varies depending on whether cephalic presentation is the result of successful ECV or spontaneous reversion [ 2 , 10 , 29 – 31 ], but we assumed that the probabilities differed.

Long-term health outcomes were modelled based upon the mortality risk associated with each MOD. The risk of neonatal mortality was taken from the RCOG guidelines. For breech presentation, these risks were 0.05% for delivery through ELCS and 0.20% for vaginal delivery. The risk of neonatal mortality for cephalic presentation with vaginal delivery was 0.10% [ 1 ]. There were no randomised clinical trials that allowed us to compare the outcomes of ELCS versus vaginal delivery for uncomplicated pregnancies with cephalic presentation; however, most observational studies found no significant difference in neonatal mortality and serious morbidity between the two modes [ 32 – 34 ]. For this reason, we assumed the mortality risk for cephalic vaginal and ELCS deliveries to be identical. We also assumed that EMCS would have the same mortality rate as ELCS, both for cephalic and breech deliveries. Studies have found that the MOD for breech presentation affects the risk of serious neonatal morbidity in the short term but not in the long term [ 1 , 3 , 35 ]. For this reason, we focused the economic analysis on the effect from mortality only. The average lifetime quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) per member of the UK population was estimated using data on quality of life from Euroqol, weighted by longevity indexes from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) [ 36 , 37 ]. Using the annual discount rate of 3.5%, as recommended by NICE, the net present value for the average lifetime QALYs at birth was 24.3 [ 38 ].

The model was probabilistic, capturing how uncertainty in the input parameters affected the outputs by allowing each parameter to vary according to its distribution. Binary and multivariable outcomes were modelled using the beta and the Dirichlet distributions, respectively [ 39 ]. Probabilities of events were calculated from the POP study and presented in Table 1 . On top of the probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA), the sensitivity of individual parameters was also explored through one-way sensitivity analyses modifying probabilities by +/− 1 percentage point and costs by +/− £10 to see which parameters had the greatest impact on cost effectiveness estimates.

Total costs depended on the distribution of MOD, the number of expected mortalities, and the cost of ultrasound scanning and ECV. Nationwide costs for each screening strategy were calculated for 585,489 deliveries, i.e., the number of births in England from 2016–2017, assuming 92% occur after 36 wkGA [ 15 , 40 ]. Model parameters were sampled from their respective distributions in a PSA of 100,000 simulations for each strategy. To determine cost effectiveness, we used two different willingness-to-pay thresholds: £20,000 and £30,000 [ 38 ]. A copy of the model code is available from the corresponding author (EW) upon request.

Recruitment to the POP study cohort is shown in Fig 2 and has been previously described [ 17 ]. Information about presentation at the 36-week scan was available for 3,879 women who delivered at the Rosie Hospital, Cambridge, UK; 179 of these had a breech presentation.

Schedule of patient recruitment in the POP study shown by foetal presentation. POP, Pregnancy Outcome Prediction.

We compared maternal and foetal characteristics of the 179 women with breech presentation at 36 weeks to the women with a cephalic presentation ( Table 2 ). Women diagnosed with breech presentation were, on average, a year older than women with a cephalic presentation, but other maternal characteristics did not differ. The babies of women diagnosed breech were smaller and born earlier, but their birth weight centile and the proportions of small for gestational age (SGA) or large for gestational age (LGA) were not markedly different. There were no differences in maternal BMI between the groups. As expected, women with breech presentation were more likely to deliver by ELCS or EMCS.

Abbreviations: AGA, appropriate for gestational age; FTE, full-time education; LGA, large for gestational age; MOD, mode of delivery; POP, Pregnancy Outcome Prediction; SGA, small for gestational age.

Statistics are presented as n (%) for binary outcomes and median (interquartile range) for continuous variables. The "Missing" category was not included in statistical tests. For variables without a "Missing" category, data were 100% complete. P values are reported for the difference between groups using the two-sample Wilcox rank-sum test for continuous variables and the Pearson Chi-square test for categorical variables, with trend test as appropriate (i.e., for deprivation quartile and birth weight centile category).

Breech presentation was suspected before the 36-wkGA scan for 79 (44.1%) of the women with breech presentation through abdominal palpation by the midwife or doctor; out of these, 27 had a clinically indicated scan between 32–36 weeks in which the presentation was reported. For 96 women, the breech presentation was unsuspected before the 36-week scan. Information on suspected breech position was missing for 4 women. There were no differences in BMI between the 79 women with suspected breech and the 96 women misdiagnosed as cephalic prior to the scan (median BMI was 24 in both groups, Wilcoxon rank-sum test P = 0.31).

MOD by ECV status is shown in Table 3 . ECV was performed for 84 women, declined by 45 women, and unsuitable for 23; contraindications included low AFI at screening (18 women), uterine abnormalities (2), and other reasons (3). For 25 women, an ECV was never performed despite consent; 17 babies turned spontaneously, 6 had reduced AFI on the day of the ECV, and 2 went into labour before ECV. When performed, ECV was successful for 12 women; in one case, the baby later reverted to breech presentation before delivery. Information on ECV uptake was missing for 2 women. Foetal presentation and ECV status in the structure of the economic model is shown in Supporting information, S1 Fig .

Abbreviations: ECV, external cephalic version; ELCS, elective cesarean section; EMCS, emergency cesarean section; MOD, mode of delivery.

*Eighteen women were contraindicated due to low AFI at screening, 2 for uterine abnormalities, and 3 for other reasons.

†Seventeen babies turned spontaneously, 6 had reduced AFI on the day of the ECV, and 2 went into labour before ECV.

The results from the economic analysis are presented in Table 4 . On average, universal ultrasound resulted in an absolute decrease in breech deliveries by 0.39%. It also led to fewer vaginal breech deliveries (absolute decrease by 1.04%) and overall EMCS deliveries (0.72%) than selective ultrasound but increased overall deliveries through ELCS (1.51%). Resulting from the more favourable distribution of MOD, the average risk of mortality fell by 0.0013%. On average, 40 women had to be scanned to identify one previously unsuspected breech presentation (95% Credibility Interval [CrI]: 33 to 49); across England, this would mean that 14,826 (95% CrI: 12,048–17,883) unidentified breech presentations could be avoided annually.

Abbreviations: ECV, external cephalic version; ELCS, elective cesarean section; EMCS, emergency cesarean section; MOD, mode of delivery; QALY, quality-adjusted life years; VB, vaginal breech.

Costs (£) are presented per patient, except in column for ‘total population’ ( n = 585,489).

The expected per person cost of universal ultrasound was £2,957 (95% CrI: £2,922–£2,991), compared to £2,949 (95% CrI: £2,915–£2,984) from selective ultrasound, a cost increase of £7.29 (95% CrI: 2.41–11.61). Across England, this means that universal ultrasound would cost £4.27 million more annually than current practice. The increase stems from higher costs of ultrasound scan (£20.3 per person) and ECV (£3.6 per person) but is partly offset by the lower delivery costs (−£16.5 per person). The distribution of differences in costs between the two strategies is shown as Supporting information, S2 Fig . The simulation shows that universal ultrasound would, on average, increase the number of total ELCS deliveries by 8,858 (95% CrI: 7,662–10,068) but decrease the number of EMCS and vaginal breech deliveries by 4,196 (95% CrI: 2,779–5,603) and 6,061 (95% CrI: 6,617–8,670) per year, respectively.

The long-term health outcomes are presented in Table 4 . Nationwide, universal ultrasound would be expected to lower mortality by 7.89 cases annually (95% CrI: 3.71, 12.7). After discounting, this means that universal ultrasound would be expected to yield 192 QALYs annually (95% CrI: 90,308). The cost effectiveness of universal ultrasound depends on the value assigned to these QALYs. The incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) was £23,611 (95% CrI: 8,184, 44,851), which is of borderline cost effectiveness (given NICE’s willingness to pay of £20,000 to £30,000) [ 38 ]. The number needed to scan per prevented mortality was 74,204 (95% CrI: 46,124–157,642).

One-way sensitivity analysis showed that the probability parameter with the greatest impact upon the cost effectiveness of universal ultrasound was the prevalence of breech: increasing this parameter by 1 percentage point was associated with a relative reduction of costs for universal ultrasound by £3.07. The results were less sensitive to the ECV success rate; an increase by 1 percentage point led to a relative reduction in the cost of universal ultrasound by £0.12. The most important cost parameter was the unit cost of ultrasound scan; an increase in this parameter by £10 led to a relative increase for universal ultrasound by £9.79 (see Supporting information , S3 Fig ). Keeping all other parameters equal, universal ultrasound would be cost effective if ultrasound scanning could be provided for less than £19.80 or £23.10 per mother, for a willingness-to-pay threshold of £20,000 or £30,000, respectively. For universal ultrasound to be cost saving, scans would need to cost less than £12.90 per mother.

In a prospective cohort study of >3,800 women having first pregnancies, a presentation scan at approximately 36 wkGA identified the 4.6% of women who had a foetus presenting by the breech, and for more than half of these, breech presentation had not previously been clinically suspected. The majority of these women were ultimately delivered by planned cesarean section, some experienced labour before their scheduled date and were delivered by EMCS, and a small proportion had a cephalic vaginal delivery following either spontaneous cephalic version or ECV. No woman in the cohort had a vaginal breech delivery or experienced an intrapartum cesarean for undiagnosed breech. The low uptake of vaginal breech birth is likely to reflect the fact that this is a nulliparous population, and it is generally accepted that the risks associated with vaginal breech delivery are lower in women who have had a previous normal birth.

Our economic analysis suggests that a universal late-pregnancy presentation scan would decrease the number of foetal mortalities associated with breech presentation and that this is of borderline cost effectiveness, costing an estimated £23,611 per QALY gained. The key driver of cost effectiveness is the cost of the scan itself. In the absence of a specific national unit cost, we have identified the maximum cost at which it would be cost effective. This is £19.80 per scan to yield an ICER of £20,000 per QALY and £23.10 at £30,000. These unit costs may be possible if assessment of presentation could be performed as part of a routine antenatal visit. Portable ultrasound systems adequate for presentation scans are available at low cost, and a presentation scan is technically quite simple, so the required level of skill could be acquired by a large cadre of midwives. This would result in a small fraction of the costs associated with a trained ultrasonographer performing a scan in a dedicated space using a high-specification machine. If universal ultrasound could be provided for less than £12.90 per scan, the policy would also be cost saving.

Our sensitivity analysis shows that the unit cost of ultrasound scans and the prevalence of breech presentation were by far the biggest determinants of the cost and cost effectiveness of universal ultrasound. The detection rate with abdominal palpation (i.e., for selective ultrasound) is the most important parameter aside from these. By contrast, the costs, attempt, and success rates for ECV have modest impact upon the choice of scanning strategy. It appears that the main short-term cost benefit from late-pregnancy screening lies in the possibility of scheduling ELCSs when breech presentation is detected, rather than turning the baby into a cephalic position.

This analysis may have underestimated the health benefits of universal late-pregnancy ultrasound. In the absence of suitable data on long-term outcomes by MOD and foetal presentation, we made the simplifying assumption that mortality rates were equal for ELCSs and EMCSs. Relaxing this assumption would likely favour universal ultrasound, as this strategy would reduce EMCSs, and these are associated with higher risks of adverse outcomes than ELCSs [ 41 – 44 ]; on top of health benefits, this may also reduce long-term NHS costs. It is also possible that an EMCS for a known breech presentation is less expensive and has better health outcomes than one for which breech is detected intrapartum, although lack of separate data for these two scenarios prevented us from pursuing this analysis further.

Our analysis shows that universal late-pregnancy ultrasound screening would increase total number of cesarean sections. Evidence suggests that cesarean delivery may have long-term consequences on the health of the child (increased risk of asthma and obesity), the mother (reduced risk of pelvic organ prolapse and increased risk of subfertility), and future pregnancies (increased risk of placenta previa and stillbirth) [ 45 , 46 ]. There is no evidence that these are related to the type of the cesarean section (elective versus emergency) [ 45 , 46 ]. Our economic modelling has not been able to capture these complex effects due to the model’s endpoints and the focus on the current pregnancy only. However, accounting for these effects, it seems plausible that universal late-pregnancy ultrasound would be more favourable for mothers than children or future pregnancies.

Our results are also driven by vaginal delivery yielding worse long-term health outcomes than ELCS for breech presentation [ 1 ]. However, even though the rate of vaginal breech birth declined after the Term Breech Study, in many cases, the outcomes are not inferior to that of ELCS, and the RCOG guidelines state that vaginal breech delivery may be attempted following careful selection and counselling [ 1 , 3 , 47 ]. It is hard to assess how an increase in vaginal breech delivery would affect the cost effectiveness of universal ultrasound; while decreased mortality risk from vaginal breech delivery would decrease the importance of knowing the foetal presentation, universal screening would facilitate selection for attempted vaginal breech delivery.

One limitation of this study is that foetal presentation was revealed to all women in the POP study. Consequently, this study cannot say what would have happened without routine screening. However, we felt that it was appropriate to reveal the presentation at the time of the 36-wkGA scan, as there is level 1 evidence that planned cesarean delivery reduces the risk of perinatal morbidity and mortality in the context of breech presentation at term [ 44 ]. Another weakness was that the study was being undertaken in a single centre only and that the sample size was too small to avoid substantial parameter uncertainty for rare events. Moreover, less than half of all breech presentations in the POP study were detected by abdominal palpation. It is unclear whether the detection rates were affected by midwives knowing that the women were part of the POP study and, hence, would receive an ultrasound scan at 36 wkGA.

The prevalence of breech presentation in this study (4.6%) appears higher than the 3%–4% that is often reported in literature [ 1 ]. However, this study is unique in that it reports the prevalence at the time of ultrasound scanning, approximately 36 wkGA. Taking into account the number of spontaneous reversions to cephalic and that some cases of successful ECV may have turned spontaneously without intervention, our finding is consistent with the literature. The ECV success rate in the POP study was considerably lower than reported elsewhere in the literature; it was even lower than the 32% success rate that has been reported as the threshold level for when ECV is preferred over no intervention at all [ 48 ]. This might partly reflect the participants in the POP study; they were older and more likely to be obese than in many previous studies, and the cohort consisted of nulliparous women, who have higher rates of ECV failure than parous women [ 9 , 49 , 50 ]. It is also possible that the real-world ECV success rate is lower than in the literature due to publication bias. However, sensitivity analysis indicates that the impact from an increased ECV success rate would be modest (an increase in ECV success rate by 10 percentage points lowers the incremental cost of universal ultrasound by £0.91 per patient).

The findings from this study cannot easily be transferred to another health system due to the differences in healthcare costs and antenatal screening routines. Some countries, e.g., France and Germany, already offer a third-trimester routine ultrasound scan. However, these scans are offered prior to 36 wkGA, and as many preterm breech presentations revert spontaneously, it would have limited predictive value for breech at term [ 51 ]. Whether screening for breech presentation in lower-income settings is likely to be cost effective largely depends on the coverage of the healthcare system; while screening may be relatively more costly, the benefits from avoiding undiagnosed breech presentation may also be relatively larger.

Whether the findings of this study could be extrapolated beyond nulliparous women is hard to assess. The absence of comparable data on screening sensitivity without universal ultrasound for parous women is an important limitation. The risks associated with breech birth also differ between nulliparous and parous women [ 52 , 53 ]. Compared to nulliparous women, parous women have higher success rates for ECV but also higher risk of spontaneous reversion to breech after 36 wkGA [ 9 , 28 ]. Also, the risks associated with vaginal breech delivery are lower in women who have had a previous vaginal birth [ 30 ].

Breech presentation is not the only complication that could be detected through late-pregnancy ultrasound screening. The same ultrasound session could also be used to screen for other indicators of foetal health, such as biometry and signs of growth restriction. Whether also scanning for other complications could increase the benefits from universal ultrasound has been and currently is subject to research [ 54 , 55 ]. Exploring the consequences from such joint screening strategies goes beyond the scope of this paper but has important implications for policy-makers and should therefore be subject to further research.

This study shows that implementation of universal late-pregnancy ultrasound to assess foetal presentation would virtually eliminate undiagnosed intrapartum breech presentation in nulliparous women. If this procedure could be implemented into routine care, for example, by midwives conducting a routine 36-wkGA appointment and using a portable ultrasound system, it is likely to be cost effective. Such a programme would be expected to reduce the consequences to the child of undiagnosed breech presentation, including morbidity and mortality.

Supporting information

S1 strobe checklist.

ECV, external cephalic version; POPs, Pregnancy Outcome Prediction.

PSA, Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis.

Abbreviations

Funding statement.

This study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme, grant number 15/105/01. EW is part funded by the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre. US is funded by the NIHR Cambridge Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed here are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health ( https://www.nihr.ac.uk/ ). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 25: Breech Presentation

Jessica Dy; Darine El-Chaar

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

General considerations.

- CLASSIFICATION

- RIGHT SACRUM ANTERIOR

- MECHANISMS OF LABOR: BREECH PRESENTATIONS

- PROGNOSIS: BREECH PRESENTATIONS

- INVESTIGATION OF BREECH PRESENTATION AT TERM

- MANAGEMENT OF BREECH PRESENTATION DURING LATE PREGNANCY

- MANAGEMENT OF DELIVERY OF BREECH PRESENTATION

- ARREST IN BREECH PRESENTATION

- BREECH EXTRACTION

- HYPEREXTENSION OF THE FETAL HEAD

- SELECTED READING

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content