- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

6 Creativity at the Intersection of art and Religion

Deborah J. Haynes is a Professor of Art and Art History at the University of Colorado at Boulder, former Chair of the department from 1998-2002, and founding Director of a residential academic program in the visual and performing arts from 2003-2011. She is an artist and the author of six books including Bakhtin and the Visual Arts (1995), The Vocation of the Artist (1997), Book of This Place: The Land, Art, and Spirituality (2009), Spirituality and Growth on the Leadership Path: An Abecedary (2012), and Bakhtin Reframed (2013).

- Published: 03 February 2014

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

What does creativity mean in the study of the arts and religious traditions? In discussing this question, the chapter begins with general definitions of creativity and the creative process, then examines in more detail how creativity intersects the arenas of visual art and religion. Using an interpretive model based on categories of creator, object, viewer, and context, examples are drawn from diverse cultures. Issues of diversity and cultural differences in the interpretation of creativity within and outside of religious traditions, as well as the relationship of creative artistic work to contemplative practice, are also addressed.

What does creativity mean in the study of art and religion? Or, more specifically, how is creativity understood throughout history and across cultures in relation to the arts and religious traditions? This chapter may be differentiated from more general creativity articles or from discipline-specific discourse because it addresses these questions directly. Following this brief introduction, the first section defines creativity both generally and specifically in relation to the arts and religion. The second section addresses the creative process itself, while the third section offers an interpretive model centered on the categories of creator, object, viewer, and context. In these two sections, examples are drawn from a range of artistic traditions in the visual arts, though the model is applicable to all of the visual and performing arts. The conclusion identifies two significant issues for ongoing exploration, especially diversity and cultural differences in the interpretation of creativity, and the relationship of creative work in the arts to contemplative practice within and outside of religious traditions.

6.1 Definitions

Like the word “culture,” creativity is difficult to define because it is so multivalent. Within different disciplinary arenas, definitions of creativity can be quite specific. For example, since the late 1940s tremendous energy has been expended in creativity studies in psychology and education, with the establishment of two major scholarly journals, a creativity encyclopedia, and numerous publications. 1 Analogously, in the visual, performing, and literary arts, volumes on creativity tend to deal with the creative process of productive individuals. 2

In cultures of the European west, three major conceptions of creativity can be traced to Plato, Aristotle, and Kant, respectively. 3 The earliest discussion of creativity in the arts can be found in Plato’s short dialogue, the Ion . 4 There, Plato suggested that creative activity is dependent upon a muse or external divine power that provides inspiration for the performer, poet, or artist. But Plato’s view of inspiration and creativity cannot be separated from his understanding of imagination. In the Republic (Books VI, VII, X), he articulated a view of imagination as an inferior capacity of the mind, a product of the lowest level of consciousness. 5 The visions of poets such as Homer, as well as the products of artistic creativity more generally, were part of the mantic or irrational world of belief and illusion. As such, they were inferior to philosophy and mathematics, which were higher forms of knowledge. For Plato, human creativity was therefore mimetic and derivative, never able to claim access to divine truth. 6

In contrast to this idea, Aristotle developed the notion of art as craft, a process whereby the artisan’s plan is imposed upon a material to create an object, but not necessarily a new form or new thing. If Plato was mainly concerned to protect the polis from the problems of idolatry, Aristotle’s contribution to developing ideas about creativity and imagination must be seen on a more psychological level. In On the Soul and On Memory and Recollection , he shifted attention to the psychological workings of imagination, interpreting it primarily as the capacity to translate sense perception into concepts and rational experience. Because of our imaginative images and thoughts, we are able to calculate and deliberate about the relationship of things future to things present, which has enormous implications for creative activity. 7

Kant’s articulation of creativity as a function of genius established a third model that has been influential in all modern and postmodern approaches to artistic creation. According to Kant, a genius is capable of establishing new rules, developing new works of art, and evolving new styles. These processes are thoroughly dependent upon imagination. Like the Greeks, Kant saw imagination as the mediator between sense perception and concepts, but he also insisted that it is one of the fundamental faculties of the human soul. 8 Without the syntheses of imagination, we would be unable to create a bridge between these other mental faculties. In other words, imagination fuses sense perception and thinking so that creativity is possible.

But there was an essential difference between the earlier premodern conceptions of the Greek philosophers and Kant’s distinctly modern view. Whereas the premodern philosophers saw imagination as dependent upon preexisting faculties of sense perception and reason, modern philosophers such as Kant posited the imagination as an autonomous faculty, both prior to and independent of sensation and reason. 9 In his Critique of Pure Reason and the Critique of Judgment , Kant described imagination as a free playful speculative faculty of the mind, “purposiveness without a purpose.” This free play would lead to artistic creativity, as Romantic philosophers such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge would also argue. 10

These ideas have been enormously influential in all subsequent philosophies of creativity in European-based cultures. Since becoming a subject of analysis in the late nineteenth century, creativity has continued to generate much interest across various disciplines. By the twentieth century, the word “creator” was applied to all of human culture, including the sciences, new technologies, and politics.

Most modern definitions of creativity emphasize qualities of originality and novelty, although such definitions may be challenged, as we shall see. Originality may involve making connections between what was previously unconnected or being open to questioning, ambiguity, and unpredictability. Having a positive view of uncertainty, with no particular attachment to outcome, can lead to unprecedented results. Novelty, the ability to create something new, may result from vague, indefinable, and mysterious creative processes. Some definitions of creativity presuppose the idea of an innate capacity, talent, or genius, while others emphasize the role of imaginative inquiry and perseverance. 11

All such definitions imply comparison. To say that something or someone is creative is clearly a judgment, and judgments are always culturally specific. Thus, three ingredients are essential to any general definition of creativity: a culture that has established symbolic rules, a person or group whose activity is marked by novelty, and a group of experts or critics who would validate this person’s innovative efforts. 12 An artist must create an object in a particular medium, which is received and interpreted by a viewer or audience in a unique context.

Within the study of religion, creativity can be linked to cosmogonic myths or myths of origin. Creation myths often combine motifs such as creation ex-nihilo, from chaos, from a cosmic egg or from world parents; creation through a process of emergence; and creation through the agency of an “earth diver,” where water is crucial. 13 For much of human history, creativity was the prerogative of the gods, the earth, or the waters. But somewhere in this history, humans became the creators. By the nineteenth century, Karl Marx and others insisted that we even created the gods. A more positive spin on this idea has been articulated by constructive theologian Gordon D. Kaufman, who argues that the human imagination creates images that provide orientation and guidance for the conduct of human life, and that the divine mystery itself may be understood as creativity. 14

Finally, there are at least eight ways in which trying to explain creativity is fraught with mystery and paradox; and each of these may be linked to religion. 15 First, creativity is ubiquitous and every person is capable of creative acts. But creativity is also often defined as extraordinary, as occurring outside of everyday life. In his description of the ethics of creativity, for instance, Nicholas Berdyaev describes the inner and outer aspects of creativeness. The inner aspect involves creative conception, where one stands, as Berdyaev puts it, “face to face with God” and in touch with the mystery of existence; while the more mundane outer aspect involves one’s creative action in the context of others and the world. 16

Second, novelty is often identified as the single most significant characteristic of creativity. Yet, novelty alone is not sufficient for defining the full range of creativity. In many cultures, including Orthodox Christian, Buddhist, and Native American that we will discuss further, novelty is often shunned in favor of adherence to traditions. This does not mean that individual artists never create new forms—one need only consider the innovations of Russian icon painters Andrei Rublev (c. 1360–1427) and Dionysius (1440–1510).

Third, creativity may be interpreted as different from, or the same as, intelligence in general. Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences sets forth an interpretation of intelligence along eight distinctive axes. 17 Of these, creativity figures prominently in at least three of the models, including linguistic, spatial, and musical intelligences. Fourth, creative works of art require knowledge and skill, but simultaneously an artist or performer must maintain freedom from the constraints of these conceptual and technical abilities. A fifth point is related to this: creative people are encouraged, albeit tacitly, to deviate from traditional social norms. Simultaneously, there are limits to what social institutions and social norms will allow. Obviously, an artist’s location within a religious or cultural institution, as well as the particular patronage associated with that location, will determine the balance of technical skill and freedom from constraints.

Sixth, many definitions of creativity assume that there must be a creative product or event of some kind. But creativity is often studied without reference to end products and creative practice may or may not yield an enduring product. Medieval and early modern religious paintings by artists such as Giovanni Bellini (1430–1516) and Lucas Cranach (1472–1553), for instance, were designed to last for centuries, while Buddhist sand mandalas and Navajo sandpaintings exist for only a short time span. In contemporary art, installation and performance art share this latter characteristic, whether done for religious or secular purposes.

Seventh, creativity often requires combining personal characteristics that would seem to contradict one another. For instance, humility and modesty or deep self-confidence and self-assertion may characterize, in turns, a given creative process. Finally, creativity can result from opposite types of motivations, from seeking self-aggrandizement to creating as a gift, from seeking external recognition to treating creative work as contemplative practice. In the contemporary world, artistic work in the service of religious institutions may or may not lead to recognition and sales. But as Robert Wuthnow has documented, many contemporary artists, writers, and poets have turned to spirituality more generally as the source of their creative work. 18

Other issues further complicate the nature and understanding of creativity. For instance, age can be a significant factor in creative productivity, as recent studies have shown. 19 Supported by the research of E. Paul Torrance, Robert Sternberg, and Howard Gardner since the 1960s, some attempts have been made to examine the role of socio-cultural environments on the development of various abilities, including creativity and intelligence. A few published studies have sought to redefine creativity and intelligence among diverse ethnic and racial groups, but little has been written about how gender and class inform opportunities for creative work among non-western cultures. We will return to these issues at the conclusion of the chapter.

In the end, creativity must be understood as a multifaceted construct with diverse characteristics. Distinct ways of processing information and solving problems may be called creative. Creativity occurs in a variety of domains from the visual and performing arts to the sciences and religion. It results in a wide range of subjective outcomes and objective products, from feelings of fulfillment and self-worth to the production of paintings, musical scores, poems, novels, and temporary objects and rituals. 20

6.2 The Creative Process

Like definitions of creativity, the creative process is complex. It may be understood as a process of change, development, and evolution in the organization of both the inner life and in the wider context of society. 21 Dating from the early twentieth century, scholars have tried to define a series of four to six steps in the creative process that may or may not be sequential, but are usually recursive. 22 The first step is usually described as preparation or gathering information, which may be conscious and critical or directed by less willful processes of invention. An artist in any medium must master accumulated knowledge, techniques, and skills; gather new facts; observe; explore; experiment; and discriminate—all of which are conscious and voluntary activities. The second phase involves incubation, during which this will to create is joined by more intuitive, unconscious, and spontaneous dimensions of the process. Many artists, writers, and scientists have described the experience as having religious qualities, from a sense of oceanic consciousness to egolessness and complete mindfulness of the present moment.

The third stage is illumination or insight, when new connections are made spontaneously in what has often been called the “Aha!” experience. In actual creative processes, this type of insight may occur at various stages. The fourth step involves evaluation of what is genuinely valuable and worthy of further development, and what can be discarded. This can be a stage of critical assessment, doubt, and uncertainty. The fifth step is elaboration, which is often identified as the most difficult part of the process. At this point, a person must engage in the hard work to give form to ideas and insights. And here especially, the recursive aspect of the process comes into play, as fresh insights may emerge, new skills must be learned, or innovative approaches must be explored. A sixth stage, which is not always acknowledged among creativity researchers, may involve communication to audiences, viewers, and critics, and levels of external validation of the creative process.

Many factors influence how this process evolves for an individual creator, such as the level of knowledge or insight; intrinsic motivation; courage; and other personal factors such as willingness to take risks, relevance, and the religious or other context that supports an artist’s creativity. 23 The success of a creative process is also dependent upon diverse information-processing skills, such as problem-solving, critical and divergent thinking, cognitive flexibility, and the ability to generate fantasies and visual imagery.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi has linked the creative process to the “flow experience,” which, like the steps described above, is not linear. 24 His research among diverse groups showed remarkable consistency in descriptions of this experience, which is characterized by clear goals, immediate feedback, and a balance between challenges and skills. Action and awareness merge in mindfulness and one-pointed attention. Distractions are minimized, and self-consciousness disappears. There is little worry about failure and the sense of time is distorted. Finally, the activity becomes autotelic: it is often experienced as an end in itself. There is no external reason or goal for doing such activities other than the experience they provide. Of course, in reality many creative processes involve both external goals and intrinsic enjoyment.

Given this discussion about creativity and the creative process, how can one best examine the intersection of artistic and religious creativity? One might turn to philosophical or theological texts, such as the work of John Dewey, Nicholas Berdyaev, or Gordon Kaufman, or to the writing and art of historical artists such as William Blake or Philipp Otto Runge. But the early philosophical writing of Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin offers a particularly vivid meditation on the crucial links between artistic creativity and religious and moral issues. 25 Along with ideas developed later in his work, answerability, outsideness, and unfinalizability form the core of his extended, if fragmentary, theory of creativity.

Briefly, answerability offers a way of naming the profound connectedness and reciprocity of creative work to life and to living artistic and religious traditions. Art and life answer to each other much as human beings answer each other’s needs and inquiries in time and space. Answerability was his way of naming the fact that art, and hence the creative activity of the artist, is always related, answerable, to life and lived experience. Bakhtin’s interpretation of creativity emphasized the profound moral and religious obligation we bear toward others. Such obligation is never solely theoretical, but is an individual’s concrete response to actual persons in specific situations.

With the concept of outsideness, Bakhtin criticized and tried to balance Neo-Kantian notions of aesthetic empathy and identification. For Bakhtin, aesthetic and moral activity only begin after empathy, which he interpreted as a form of “living-oneself-into” the experience of another person. Creativity itself is only possible because of boundaries between persons, events, and objects and the outside perspective these boundaries establish. The meaning of a creative act evolves in relation to the boundaries—the inside and outside—of the cognitive, ethical, and aesthetic spheres of culture. Indeed, creative activity must be understood in relation to the unity of culture, including religion.

Unfinalizability emphasizes the unrepeatability and open-endedness of creative acts that make change, including religious transformation, possible. Unfinalizability may help us to articulate complex answers to questions about particular works of art. When is a work finished? Can it ever be truly finished? When is a critical perspective or audience reception complete?

This sense of freedom and openness applies not only to works of literature and art, but it is also an intrinsic condition of our daily lives. Such creativity is ubiquitous and unavoidable, and cannot be separated from one’s responsibility toward others and toward the world. There always is a tentative quality to one’s work, one’s action, and to life itself. Even though a person’s life is finalized in death, that person’s work lives on, to be extended and developed by others, an insight we certainly know in relation to important historical artworks, such as Michelangelo’s Pieta , Leonardo’s Last Supper , or Rembrandt’s paintings of biblical subjects. The creative process, too, is unfinalizable, except insofar as an artist or writer says, “I stop here.” Precisely because it is always open to change and transformation, artistic work can be a model for change in the larger world of cultures and religions.

Thus far we have emphasized the ways in which creativity and the creative process are defined, both as autonomous spheres and in relation to religion. The question of how the creative process may be interpreted vis-à-vis actual works of art, however, has not yet been addressed. The following section therefore proposes a four-part interpretive model that is useful for understanding creativity at the intersection of religion and the arts.

6.3 An Interpretive Model

Any work of art may be analyzed in terms of its creator; the object, event, or ritual produced; the viewer or participant; and the wider cultural context in which it has been made. Here we seek to demonstrate how this model actually works by analyzing diverse cultural examples of creativity that are both artistic and religious. Each element in this model may be identified in several ways. The creator of a work may be an artist or performer, a monk, priest, or shaman. An object may be a physical artifact, aesthetic event, or ritual. A viewer or participant may be individual or the audience may be collective. And the context always exists in a particular time and place. The examples considered here range from Russian Orthodoxy, Tibetan Buddhism, and Navajo religion to European and contemporary art.

Creator. In examining the creator of a work of art in relation to religious values, it is helpful to answer several questions. Are there special personality traits or motivations in artists of all genres? Who gets to be an artist? Issues of caste and class must be considered. What is the role of the artist and how are characteristics defined?

In some cultural traditions the role of the artist remains very carefully prescribed. Traditionally, Russian icon painters and Buddhist thangka painters, for example, were anonymous; and they usually worked under canonical authority and strong artistic tradition where both technical skill and personal conduct were carefully prescribed. Icon “writers” use podlinniki , or pattern books, for painting their subjects. The act of painting an icon is described with the linguistic metaphor of translation: the painter quite literally writes a perevod or translation. 26 Analogously, thangka painters use iconometric diagrams for their work. But within both traditions, opportunities for individual expression may still be found in decorative details such as landscape and ornamentation. 27 Since the twentieth century, however, icons and thangkas have become marketable objects, so the painter’s role has changed radically to a producer for the consumer market.

In stark contrast to such definitions that emphasize anonymity and tradition, there have been at least three historical moments when the artist has been esteemed as a cultural hero: in Greek culture, in the early Renaissance, and in modern Europe, synchronous with the Industrial Revolution. 28 The first coincided with the birth of technology, symbolized in the Greek myths of Prometheus and Daedalus. The promethean impulse, however, has lived up to the present—in movements such as the Russian avant-garde and in individual artists such as Joseph Beuys—where the belief exists that artists are able to transform the world once they are aware of their powers.

The second period involved the separation of the fine arts from the crafts in the late medieval period and early Renaissance. The thirteenth and fourteenth centuries were years of transition in Europe. Artists, many of whom were anonymous, worked in royal courts, in cloistered religious communities, and as masons who designed and built palaces, castles, and churches. However, the establishment of private patronage by merchant families and princely courts provided fertile ground for the professionalization of the artist and the emergence of the myth of the artist-hero. Giorgio Vasari founded the first academy of art, the Accademia del Disegno, in 1563, which provided an institutional framework for artists, offering them security and social prestige. There, artists were given both a theoretical and practical education according to the stylistic ideals Vasari had developed in his Lives of the Artists. 29 His artist-hero myth was modeled on the stories of Hercules and Launcelot; and it was primarily internalized to support male artists such as Michelangelo and Leonardo.

Another nineteenth-century model for the artist that emphasized the relationship of religion and art was the notion of the artist as interpreter and prophet of God. William Blake and Caspar David Friedrich exemplify this model, but in Philipp Otto Runge we find an especially relevant example of such tendencies in European Romanticism. Runge’s art, and his theories about it, were anchored in his Lutheranism, but they were also deeply informed by his interest in the ideas of the seventeenth-century mystic Jacob Böhme. In his ten-point manifesto Runge claimed that the artist should express “presentiment of God,” “consciousness of ourselves and our eternity,” and “perception of ourselves in connection with the whole.” 30 Romantics such as Runge, Blake, and the Russian Isaac Levitan focused on the artist’s unique experience and ability to give expression to the divine, thus fulfilling their image of the artist as mystic visionary and original creator.

Object, ritual, or event. Many questions may be asked about the objects, rituals, or events that are created. How are objects used? What rituals have developed around them? What is an icon? How do religious objects or rituals function within their particular cultural context? How might seemingly secular objects carry religious connotations?

Ideas about the power of icons within Orthodox traditions can be traced to eighth-century writings by John of Damascus. More recently, Russian philosophers such as Pavel Florenskii have added important interpretive strategies. 31 The icon depicts objects in the visible world of the senses that act as reflections of the invisible world of the spirit. Images, from this perspective, are material prototypes of the divine archetype, which is invisible. Yet an image is not merely a symbol of the archetype, but in the icon the holy is made present. Icons serve as channels of grace and mysterious vehicles of divine power, and are often described as windows or doorways into the sacred.

Navajo sandpaintings, and the chantways of which they are a part, function somewhat differently as participatory healing ceremonies. 32 The number of sandpaintings for any given chantway vary, with as many as 300 sandpaintings still known. However, for any particular ceremony, normally a maximum of four to six sandpaintings would be prepared. Materials might include sand, pollen, charcoal, cornmeal and other plant forms, rocks, ores that are pulverized with a metate (flat stone) and mano (handheld stone). The duration of the ritual varies according to the chantway, from two to fourteen days. Elements in the sandpaintings are stylized, with many forms that look human, but they also might include animals, plants and herbs, sacred objects, natural phenomena, and supernatural beings.

A completely different sensibility can be seen in the work of Constantin Brancusi, who was the first distinctly modern abstract sculptor of the twentieth century. 33 In his many variations of the Beginning of the World , Brancusi used the image of the head or egg to create an extended meditation on creativity itself, which had at least two aspects. First, it concerned the fantasy of self-creating that characterized the work of many avant-garde artists. 34 Second, many of Brancusi’s sculptures on this theme were undertaken during and after the devastation of World War I. The French government had waged a campaign to urge women to have more babies; and there was resistance among women. The government imposed draconian laws against birth control and abortion, but both persisted. In this context the head/egg may be read as having to do with birth and regeneration, including the rebirth of art itself. As Brancusi said in 1927, “There still hasn’t been any art; art is just beginning.” 35 Because his work is open to multiple interpretations, we can also now see its prophetic dimension: for women, this century has opened up new possibilities for control of their bodies. This issue has enormous religious and moral implications up to the present day.

Viewer or audience. All images resemble religious images in the sense that they have the potential to involve the beholder. 36 Icons, thangkas, and sandpaintings, for example, involve the viewer in both public and private rituals. Within Orthodox churches, viewers process around the church in devotional prayer, bowing, and kissing the icons. In a Buddhist temple large images in the central sanctuary would be used by monks and nuns for circumambulation, touching, and meditation. Both Orthodox and Buddhist private homes would have an altar with holy images, as well as other objects such as bowls of offerings or water, lamps or candles, incense, and flowers. Navajo sandpaintings are usually laid out on a clean floor of a small dwelling called a hogan. While family or community members observe, the patient sits in the middle of the sandpainting in order to restore harmony and health. Parts of the painting may be sprinkled over the person.

Such examples emphasize the viewer as participant in religious ritual. But what happens when a viewer examines the photographic documentation of Richard Long’s walks and Andy Goldsworthy’s transitory ice sculptures, or experiences contemporary land art such as James Turrell’s Roden Crater Project ? These artists’ work draws attention to the holiness and sacramental nature of the world in which we live, to the viewer’s own act of perceiving, and to the presence of space. Such qualities may combine to create a powerful sense of awe, as Turrell has observed, connecting us “with something that’s beyond our secular life.” 37

Context. The foregoing discussions of the creator, object, and viewer have already alluded to the arts within worship, healing, and ritual contexts. But other key questions remain. How do the historical time and place of an object’s creation influence its use and interpretation? Or, how do the viewers’ experiences within another time and place influence its ongoing interpretation, especially given commercial pressures? Context is obviously a crucial dimension in analyzing all works of visual and performing art.

One of the most useful articulations of this idea is Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of the chronotope, which is easy to understand. 38 Coined from the Latin chronos and topos , Bakhtin developed the term to describe the time/space nexus in which life exists and creativity is possible. Neither experience nor artifacts of culture such as art and religion exist outside of historical place and time; and both of these always change. In fact, change is essential. Therefore, subjectivity and created objects are always constituted differently. In short, all conditions of experience are determined by space and time, which are themselves variable. Within any situation there may be many different chronotopes, values, and beliefs. What the idea of the chronotope shows, however, is that those values and beliefs derive from actual social relations. With this concept, Bakhtin was not articulating a phenomenology that would objectify time and space, but rather he sought to describe how experience is made palpable in particular times and particular places.

For example, a Wheel of Existence thangka was traditionally used in a monastery or temple vestibule, where it served as a summary of Buddhist teachings. Now thangkas of the Wheel of Existence are produced for commercial markets in Asia, Europe, and the United States. Analogously, Mother of God icons are produced as small inexpensive commodities and are sold in street markets of Moscow, St. Petersburg, and other cities. Sandpaintings, once created by a singer or chanter only for particular rituals, are now glued to boards and sold as tourist art. Thus, in interpreting an icon, thangka, sandpainting, or any other work of art with religious significance such as the Roden Crater Project , it is most useful to investigate its chronotope.

So far, this chapter has focused on definitions of creativity and the creative process, and it has presented a model for interpreting creativity at the intersection of the arts and religious traditions. But this intersection might more aptly be called a major crossroads of diverse cultures and unique chronotopes. For the historian of art and religion, as well as the contemporary artist and religious practitioner, there are many possible avenues for future exploration.

6.4 Conclusion

Much of this chapter has centered on the development of concepts of creativity in the European west. But other issues regarding creativity deserve amplification, including the following. First, how do diversity and cultural differences affect definitions of creativity and the creative process? Second, what is the relationship of creative work to religious or contemplative practice?

One of the major difficulties in interpreting creativity at the intersection of artistic and religious practices concerns the dearth of reflection about the role of cultural diversity in defining these terms and their interrelationships. Unique models for understanding such creativity exist in diverse cultures of Asia, Africa, and the Americas, including in native traditions from Aboriginal Australia to the American Southwest, as we have tried to demonstrate with brief references to Navajo sandpaintings. 39 Many cultures in Asia and Africa do not have a general term such as creativity. However, other long-existing aesthetic categories have influenced the way creativity is understood and practiced.

Within Zen Buddhism in Japan, for instance, Shin’ichi Hisamatsu has described seven major characteristics of the arts and culture: dissymmetry, simplicity, austerity, naturalness, profundity, unworldliness or freedom from worldly attachments, and quietness. 40 Each of these characteristics must be understood in relationship to the others, as none can be regarded as separate and isolated; and each may be considered as both an aesthetic and religious category. In addition, others have described the idea of “deliberate incompleteness,” which forces the viewer into direct non-analytical experience of arts such as calligraphy, Zen gardens, and Noh drama. The term wabi describes the simplicity and roughness of some Zen arts, where an appreciation of asymmetry, accident, and chance are cultivated. Clearly, the emphasis in this tradition is on nonverbal and non-cognitive experience in the creative process. 41

In considering such an example, we should ask what creativity means in traditions where the artist follows prescribed aesthetic and religious categories and models, or where the work is anonymous. This is obviously a very different understanding of creativity than within most contemporary cultures, where the artist signs his or her name to every work of art. One goal of studying creativity at the intersection of art and religion is to challenge current definitions by demonstrating the importance of tradition and continuity alongside innovation and novelty. Beyond this, it is crucial to investigate more deeply the ways in which diverse traditions define this intersection of the arts and religious experience, as well as how contemporary artists are appropriating historical religions and spirituality more generally. Such issues are a fruitful area for future research.

A second arena for further development concerns the relationship of creative work and contemplative practice within contemporary cultures. Contemplative practice includes forms of meditation such as centering prayer and mindful sitting; movement and walking mindfully; focused experience in nature; certain artistic practices, for instance, making the icons, thangkas, and sandpaintings that have been discussed in this chapter; traditions of calligraphy and manuscript illumination; and liturgical music and dance. Contemplative practices help artists develop the ability to observe, to remain in the present, and to attend to the senses, and are directly related to developing self-discipline, which will have a profound affect on all forms of artistic practice.

In addition to undertaking contemplative practice as an aid to the creative process, artistic creativity itself may be a form of spiritual practice, with both inner and outer dimensions. On the one hand, many traditional artists engage in practices of inner purification through their work, cultivating values such as attentiveness, detachment, patience, humility, and silence. On the other hand, the artist gives form to religious and moral teachings. As such, the work expresses a calling or vocation to make spiritual teachings available to various publics. For artists already interested in or committed to a particular religious practice, this interpretation of art as spiritual practice might be easily incorporated into a working process. Although many secular artists actively repudiate any form of organized religion, the inner dimensions of contemplative practice are readily accessible to all visual and performing artists.

This chapter began by posing the question of what creativity means at the intersection of art and religion. It ends with another question: in the howl of contemporary life, where do we have time or space for the solitude and silence that nurture creativity, except in the religious community and the artist’s studio? The deep kinship and interconnectedness of the visual and performing arts and religious traditions are reflected in creativity, the creative process, and in religious and artistic life.

1. See Creativity Research Journal, published since 1988 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; and Mark A. Runco’s and Steven R. Pritzker’s two-volume Encyclopedia of Creativity (San Diego: Academic Press, 1999) .

2. One of the best examples of this approach remains Brewster Ghiselin’s , The Creative Process: A Symposium (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1954) .

3. This idea is also developed by Philip Alperson , in “Creativity in Art,” The Oxford Handbook of Aesthetics , ed. Jerrold Levinson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 454 .

4. Plato , “Ion,” in Two Comic Dialogues , trans. Paul Woodruff (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1983) .

5. Plato , The Republic , ed. and trans. by I. A. Richards (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1966) .

6. Richard Kearney , The Wake of Imagination: Toward a Postmodern Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988), 105 .

7. Aristotle , On the Soul 3, 7, 431b3-431b9, trans. W. S. Hett (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1935), 179 .

8. Immanuel Kant , The Critique of Pure Reason , translated by Norman Kemp Smith (London: Macmillan, 1958), 112 , 142ff, 146, 165; and Immanuel Kant , The Critique of Judgement , translated by J. C. Meredith (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1952), 30–32, 86, 89, 115, 210, 212, 236 .

Kearney, Wake , 111–112.

10. Samuel Taylor Coleridge , Biographia Literaria I, ed. J. Shawcross , 1817 (repr., London: Oxford University Press, 1965), 167, 202 .

11. Albert Rothenberg , “Creativity and Psychology,” in Encyclopedia of Aesthetics , ed. Michael Kelly , Vol. 1 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 459 .

12. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi , Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention (New York: HarperCollins, 1996), 6 .

13. For a useful overview, see Charles Long’s article on “Cosmogony,” in Encyclopedia of Religion , vol. 3, 2nd ed., editor-in-chief Lindsay Jones (Farmington Hills, MI: Thomson Gale, 2005), 1985–1991 .

14. Gordon D. Kaufman , In Face of Mystery: A Constructive Theology (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993) ; and Gordon D. Kaufman , In the Beginning…Creativity (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2004), esp. 100–106 .

15. This discussion expands upon Arthur J. Cropley’s brief description of paradox in “Definitions of Creativity,” in Encyclopedia of Creativity , vol. 1, 524 .

16. Nicholas Berdyaev , The Destiny of Man , trans. Natalie Duddington (New York: Harper, 1960), 126–130 .

17. Howard Gardner , Frames of Mind: the Theory of Multiple Intelligences (New York: Basic Books, 1983) .

18. Robert Wuthnow , Creative Spirituality: The Way of the Artist (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001) .

19. See Martin S. Lindauer , Aging, Creativity, and Art: A Positive Perspective on Late-Life Development (New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2003) for an excellent summary of recent research that has reversed earlier assumptions about when creativity peaks within the life cycle.

20. Giselle B. Esquivel and Kristen Peters , “Diversity, Cultural,” in Encyclopedia of Creativity , vol. 1, 583–589 .

Ghiselin, Creative Process , 2–3.

22. The original articulation of this multi-step process was in Graham Wallas , The Art of Thought (New York: Harcourt-Brace, 1926) . It was further developed in Ghiselin’s “Preface” to Creative Process in 1954; in Cropley, “Definitions,” 511–524; and in Csikszentmihalyi’s Creativity , 79–81.

Cropley, “Definitions,” 516.

Csikszentmihalyi, Creativity , 110–126.

25. Mikhail M. Bakhtin , Art and Answerability: The Early Essays of M. M. Bakhtin , translated by Vadim Liapunov and Kenneth Brostrom , edited by Michael Holquist (Austin, University of Texas Press, 1990) . For an interpretation of these ideas, see Deborah J. Haynes , Bakhtin and the Visual Arts (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995) , and Deborah J. Haynes , “Answers First, Questions Later: A Bakhtinian Interpretation of Monet’s Mediterranean Paintings,” Semiotic Inquiry 18 (1998): 217–230 .

26. Robert L. Nichols , “The Icon in Russia’s Religious Renaissance,” in William Brumfield and Milos M. Velimirovic , eds., Christianity and the Arts (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 140–141 .

27. Pratapaditya Pal , Art of Tibet, A Catalogue of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Collection (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), 51–53 . Materials about the training of thangka painters are few. Cf. David P. Jackson and Janice A. Jackson , Tibetan Thangka Painting, Methods and Materials (London: Serindia Publications, 1984) .

28. For a detailed explication of this theme, see Deborah J. Haynes , The Vocation of the Artist (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 101–108 .

29. Hans Belting , The End of the History of Art , trans. Christopher S. Wood (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 83 .

30. Rudolf M. Bisanz , German Romanticism and Philipp Otto Runge: A Study in Nineteenth-century Art Theory and Iconography (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1970), 49–55 .

31. Saint John of Damascus , Orthodox Faith , in Saint John of Damascus: Writings , trans. Frederic H. Chase Jr. (New York: Fathers of the Church, 1958), esp. IV.16, 370–373 ; and Saint John of Damascus , On the Divine Images , translated by David Anderson (Crestwood, NY: Saint Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1980) . See also Pavel Florenskii , “On the Icon,” in Eastern Churches Review 8/1 (1976): 11–37 ; and Beyond Vision, Essays on the Perception of Art , comp. and ed. Nicoletta Misler , trans. Wendy Salmond (London: Reaktion, 2002) .

32. Wade Davies , Healing Ways: Navajo Health Care in the Twentieth Century (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2001) .

33. See Anna C. Chave , Constantin Brancusi (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994) , esp. Chapter 4 ; and Richard Cork , A Bitter Truth: Avant-Garde Art and the Great War (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994), esp. 310–314 .

Chave, Constantin Brancusi , 163.

Chave, Constantin Brancusi , 162.

36. David Freedberg , The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), 374 .

37. James Turrell , “Open Space for Perception,” Flash Art 24 (January-February 1991): 112 .

For examples of how the chronotope is useful in analyzing both visual art and literature, see Haynes, “Answers First, Questions Later,” 224–226, and Haynes, “Bakhtin and the Visual Arts,” 298–300.

39. Robert Paul Weiner , Creativity and Beyond: Culture, Values, and Change (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2000), 143–193 .

40. Shin’ichi Hisamatsu , Zen and the Fine Arts , trans. Gishin Tokiwa (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1971) .

41. Steven R. Pritzker , “Zen,” in Vol. 2, Encyclopedia of Creativity , 745–750 .

Alperson, Philip . “Creativity in Art.” In The Oxford Handbook of Aesthetics , edited by Jerrold Levinson , 245–257. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003 .

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Aristotle. On the Soul. Parva Naturalia, On Breath . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1935 .

Baggley, John . Doors of Perception, Icons and Their Spiritual Significance . Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1988 .

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. Art and Answerability: The Early Essays of M. M. Bakhtin . Translated by Vadim Liapunov and Kenneth Brostrom . Edited by Michael Holquist . Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990 .

———. Toward a Philosophy of the Act . Translated by Vadim Liapunov . Edited by Vadim Liapunov and Michael Holquist . Austin: University of Texas Press, 1993 .

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor . Biographia Literaria . 2 vols. Edited by J. Shawcross . 1817. Reprint, London: Oxford University Press, 1965 .

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly . Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention . New York: HarperCollins, 1996 .

Dagyab, Loden Sherap . Tibetan Religious Art . Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1977 .

Damascus, Saint John of. Orthodox Faith . In Saint John of Damascus, Writings , translated by Frederic H. Chase Jr. , 165–406. New York: Fathers of the Church, 1958 .

———. On the Divine Images . Translated by David Anderson . Crestwood, NY: Saint Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1980 .

Davies, Wade . Healing Ways: Navajo Health Care in the Twentieth Century . Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2001 .

Florenskii, Archpriest Pavel . “ On the Icon. ” Eastern Churches Review 8, no. 1 ( 1976 ): 11–37.

———. Iconostasis . Translated by Donald Sheehan and Olga Andrejev . Introduction by Donald Sheehan . Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1996 .

———. Beyond Vision: Essays on the Perception of Art . Compiled and edited by Nicoletta Misler . Translated by Wendy Salmond . London: Reaktion, 2002 .

Freedberg, David . The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989 .

Galavaris, George . Icons from the Elvehjem Art Center . Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1973 .

———. The Icon in the Life of the Church . Leiden: Brill, 1981 .

Gardner, Howard . Creating Minds . New York: Basic Books, 1993 .

Ghiselin, Brewster . The Creative Process: A Symposium . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1954 .

Goswamy, P. N. , and Dahmen-Dallapiccola, A. L. An Early Document of Indian Art . New Delhi: Manohar Book Service, 1976 .

Hausman, Carl R. “Creativity: Conceptual and Historical Overview.” In Encyclopedia of Aesthetics , edited by Michael Kelly , 453–456. Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998 .

Haynes, Deborah J. Bakhtin and the Visual Arts . New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995 .

———. The Vocation of the Artist . New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997 .

———. “ Answers First, Questions Later: A Bakhtinian Interpretation of Monet’s Mediterranean Paintings. ” Semiotic Inquiry 18 ( 1998 ): 217–230.

Jackson, David P. and Janice A. Jackson Tibetan Thangka Painting, Methods and Materials . London: Serindia Publications, 1984 .

Jarvie, I. C. “Explaining Creativity.” In Encyclopedia of Aesthetics , edited by Michael Kelly , 456–459. Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998 .

Kant, Immanuel . The Critique of Judgement . Translated by J. C. Meredith . Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1952 .

———. The Critique of Pure Reason . Translated by Norman Kemp Smith . London: Macmillan, 1958 .

Kaufman, Gordon D. In Face of Mystery: A Constructive Theology . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993 .

———. In the Beginning…Creativity . Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2004 .

Kearney, Richard . The Wake of Imagination: Toward a Postmodern Culture . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988 .

Kvaerne, Per . “Introduction to Tibetan Mythology.” In Mythologies , edited by Yves Bonnefoy , 1075–1088. vol. 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991 .

Lama, Gega . Principles of Tibetan Art: Illustrations and Explanations of Buddhist Iconography and Iconometry According to the Karma Gardri School . 2 vols. Darjeeling: Jamyang Singe, 1983 .

Leeming, David Adams , with Margaret Adams Leeming . “Navajo Creation.” In Encyclopedia of Creation Myths , 202–208. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 1994 .

Lindauer, Martin S. Aging, Creativity, and Art: A Positive Perspective on Late-Life Development . New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2003 .

Long, Charles H. “Cosmogony.” In Encyclopedia of Religion , Editor-in-chief Lindsay Jones , 1985–1991, vol. 3, 2nd ed. Farmington Hills, MI: Thomson Gale, 2005 .

Maguire, Henry . Art and Eloquence in Byzantium . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981 .

Martin, Edward James . A History of the Iconoclastic Controversy . New York: Macmillan, 1930 .

Nichols, Robert L. “The Icon in Russia’s Religious Renaissance.” In Christianity and the Arts , edited by William Brumfield and Milos M. Velimirovic , 131–144. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991 .

Pal, Pratapaditya . The Art of Tibet . New York: Asia Society, 1969 .

———. Art of Tibet: A Catalogue of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Collection . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983 .

Plato. The Republic . Translated and edited by I. A. Richards . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1966 .

———. “Ion.” In Two Comic Dialogues . Translated by Paul Woodruff , 19–39. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1983 .

Reichard, Gladys . Navajo Religion, A Study of Symbolism . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1963 .

Rice, Tamara Talbot . Russian Icons . London: Spring Books, 1963 .

Rothenberg, Albert . “Creativity and Psychology.” In Encyclopedia of Aesthetics , edited by Michael Kelly , 459–462. Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998 .

Runco, Mark A. , and Steven R. Pritzker , eds. Encyclopedia of Creativity . 2 vols. San Diego: Academic Press, 1999 .

Schofield, M. “Aristotle on the Imagination.” In Aristotle on Mind and the Senses , edited by Gwilym Ellis Lane Lloyd and Geoffrey Ernest Richard Owen , 99–140. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978 .

Sternberg, Robert J. , ed. The Nature of Creativity . New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988 .

Torrance, Ellis. Paul . Guiding Creative Talent . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1962 .

Wallas, Graham . The Art of Thought . New York: Harcourt-Brace, 1926 .

Weiner, Robert Paul . Creativity and Beyond: Cultures, Values, and Change . Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2000 .

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Does religion hinder creativity a national level study on the roles of religiosity and different denominations.

- 1 School of Psychology, Shandong Normal University, Jinan, China

- 2 College of Humanities and Social Science, Dalian Medical University, Dalian, China

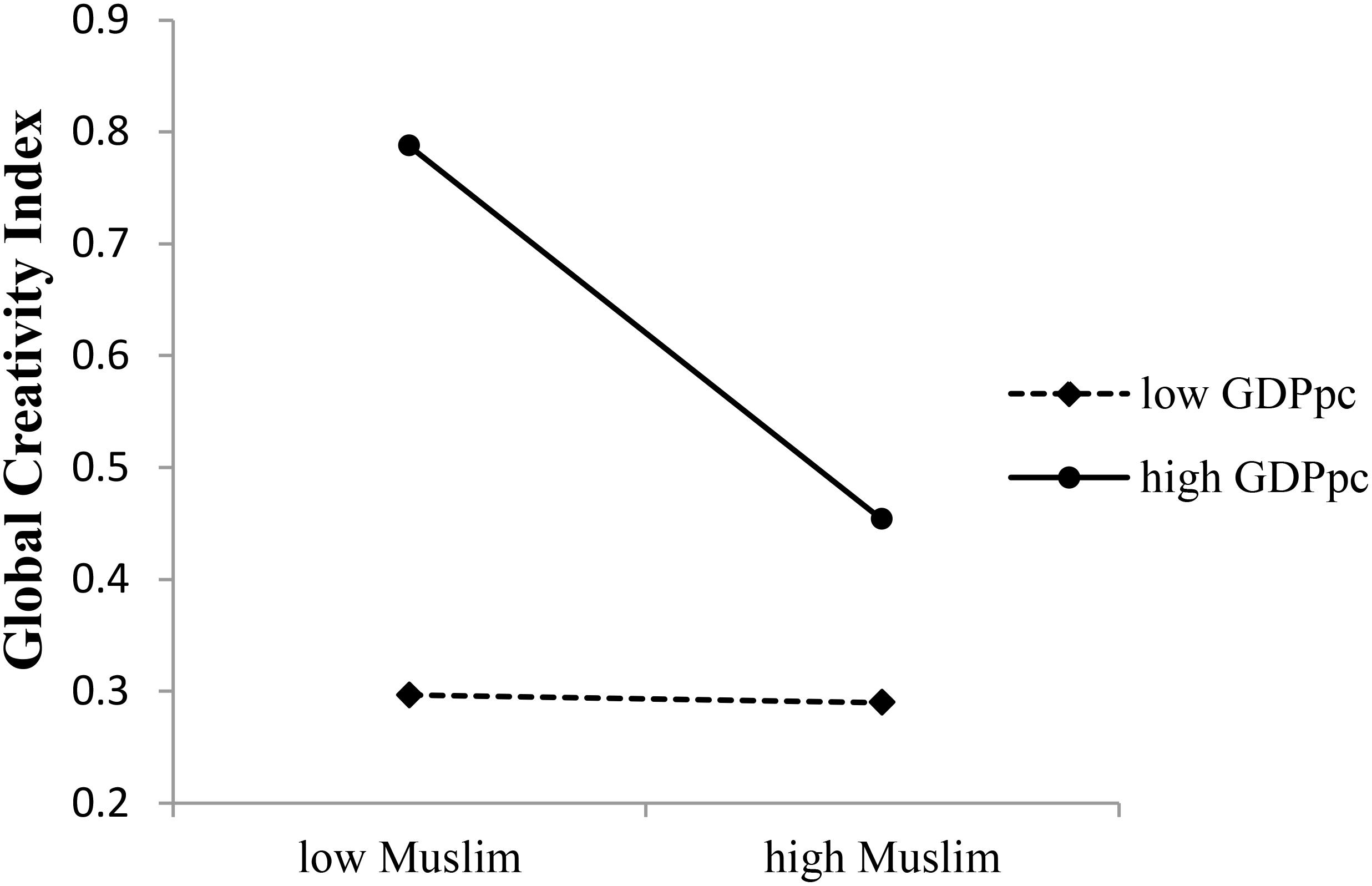

Creativity plays an irreplaceable role in economic and technological development. It seems that religion has a negative association with creativity. If it is true, how can we interpret the rapid development of human society with religious believers comprising 81% of global population? Based on the datasets of the World Values Survey and the Global Creativity Index, this study examined the effects of different religions/denominations on national creativity, and the moderation effect of gross domestic product per capita (GDPpc) in 87 countries. The results showed that: (1) religiosity was negatively associated with creativity at national level; (2) Proportions of Protestant and Catholic adherents in a country were both positively associated with national creativity, while proportion of Islam adherents was negatively associated with national creativity; (3) GDPpc moderated the relationships of creativity with overall religiosity, proportion of Protestant adherents, and proportion of Catholic adherents. In countries with high GDPpc, national religiosity and proportion of Islam could negatively predict national creativity, and proportion of Protestants could positively predict national creativity; in countries with low GDPpc, these relationships became insignificant. These findings suggest that national religiosity hinders creativity to a certain extent. However, some denominations (i.e., Protestant and Catholic) may exert positive influences on creativity due to their religious traditions and values. The religion–creativity relationship at national level only emerges in affluent countries.

Introduction