What It Means To Be Spiritual But Not Religious

One in five Americans reject organized religion, but maintain some kind of faith.

- Link Copied

A growing contingent of Americans— particularly young Americans—identify as “spiritual but not religious.” Masthead member Joy wanted to understand why. On our call with Emma Green, The Atlantic ’s religion writer, Joy asked, “What are they looking for?” Because the term “spiritual” can be interpreted in so many different ways, it’s a tough question to answer. I talked to people who have spent a lot of time mulling it over, and came away with some important context for the major shift happening in American faith.

(If you missed our call with Emma Green, you can find the transcript and recording here .)

Americans Who Want Faith, Not a Church

Kern Beare, a Masthead member from Mountain View, California, believes in God and studies the teachings of Jesus. But does he identify with a particular religion? “Never,” he told me. The structure and rigidity of a church, Beare believes, is antithetical to everything Jesus represents. Instead of attending services, he meditates every morning.

Americans are leaving organized religion in droves: they disagree with their churches on political issues; they feel restricted by dogma; they’re deserting formal organizations of all kinds. Instead of atheism, however, they’re moving toward an identity captured by the term “spirituality.” Approximately sixty-four million Americans— one in five —identify as “spiritual but not religious,” or SBNR. They, like Beare, reject organized religion but maintain a belief in something larger than themselves. That “something” can range from Jesus to art, music, and poetry. There is often yoga involved.

“The word ‘church’ means you need to put on uncomfortable shoes, sit up straight, and listen to boring, old-fashioned hymns,” said Matthew Hedstrom, a professor of religion at the University of Virginia. “Spirituality is seen as a larger, freer arena to explore big questions.”

Because over 92 percent of religiously-affiliated Americans currently identify as Christian, most “spiritual-but-not-religious” people come from that tradition. The term SBNR took off in the early 2000s, when online dating first became popular. “You had to identify by religion, you had to check a box,” Hedstrom told me. “‘Spiritual-but-not-religious’ became a nice category that said, ‘I’m not some kind of cold-hearted atheist, but I’m not some kind of moralizing, prudish person, either. I’m nice, friendly, and spiritual—but not religious.’”

Religion—often entirely determined by your parents—can be central to how others see you, and how you see yourself. Imagine, Hedstrom proffered, if from the time you were born, your parents told you that you were an Italian-Catholic, living in the Italian-Catholic neighborhood in Philadelphia. “You wouldn’t wake up every morning wondering, who am I, and what should I believe?” That would have already been decided. Young people today, Emma said on our call, “are selecting the kinds of communities that fit their values,” rather than adhering to their parent’s choices.

“Spiritual is also a term that people like to use,” said Kenneth Pargament, a professor who studies the psychology of religion at Bowling Green State University. “It has all of these positive connotations of having a life with meaning, a life with some sacredness to it—you have some depth to who you are as a human being.” As a spiritual person, you’re not blindly accepting a faith passed down from your parents, but you’re also not completely rejecting the possibility of a higher power. Because the term “spiritual,” encompasses so much, it can sometimes be adopted by people most would consider atheists. While the stigma around atheism is generally less intense than it used to be, in certain communities, Hedstrom told me, “to say you’re an atheist is still to say you hate puppies.” It’s a taboo that can understandably put atheists, many of whom see their views as warm and open-minded, on the defensive. “Spiritual” doesn’t come with that kind of baggage.

For people who have struggled with faith, embracing the word “spiritual” might also leave a crucial door open. Masthead member Hugh calls himself “spiritual,” but sees the designation as more of a hope or a wish than a true faith. “I hope there is more to this wonderful world than random chemistry... Nonetheless, I do see all of that as an illusion...That does not stop me from seeking something as close to what I wish for as I am able to find.” In his class, “Spirituality in America,” Hedstrom tells his students that the “spiritual-but-not-religious” designation is about “seeking,” rather than “dwelling:” searching for something you believe in, rather than accepting something that, while comfortable and familiar, doesn’t feel quite right. In the process of traveling around, reading books, and experimenting with new rituals, he says, “you can find your identity out there.”

Today’s Wrap Up

Question of the day : For readers who identify as SBNR, how do the descriptions above line up with your beliefs?

Your feedback : We’ve been pouring over your year-end survey responses all week. Thanks for taking the time to tell us how we’re doing. Let us know how you liked what you read today .

What’s coming : A few weeks ago, a member asked us a compelling question about abortion. We're compiling responses from a whole slew of different perspectives.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to [email protected].

Select Page

Spirituality is a broad and subjective concept that encompasses a sense of connection to something greater than oneself. It often involves exploring questions about the meaning of life, the nature of existence, and the purpose of our existence.

Different cultures, belief systems, and philosophies have their own interpretations of spirituality. For some, it is linked to organized religion and faith in a higher power or deity. For others, it may be more secular, focusing on inner peace, mindfulness, and a sense of interconnectedness with the universe.

Hello, I have a similar line of thought. I am atheist but things fell into place about all this a few months ago I did not need to throw away the idea of the all-powerful after all. It is not God. It is greater than all Gods and religions. Some religions believe almost the same thing. The “all powerful all” is simply the totality of what is. It had no mind or beingness at first. It was what we call the big bang. Life evolved with no designer or God. This totality still is all and still has all power. Sentients is within it. We serve the all powerful and its servant. This is a very big very old universe. I speculate very advanced extremely advanced beings are here and can be connected to with prayer and mediation. Of course they agree with spiritual atheism. They also know about the all powerful all. It is where they came from just like us. please check out my website www/thewayoffairness.com.

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

About | Commentary Guidelines | Harvard University Privacy | Accessibility | Digital Accessibility | Trademark Notice | Reporting Copyright Infringements Copyright © 2024 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Examining the Growth of the ‘Spiritual but Not Religious’

By Mark Oppenheimer

- July 18, 2014

“Spiritual but not religious.” So many Americans describe their belief system this way that pollsters now give the phrase its own category on questionnaires. In the 2012 survey by the Pew Religion and Public Life Project , nearly a fifth of those polled said that they were not religiously affiliated — and nearly 37 percent of that group said they were “spiritual” but not “religious.” It was 7 percent of all Americans, a bigger group than atheists, and way bigger than Jews, Muslims or Episcopalians.

Unsurprisingly, the S.B.N.R.s, as this growing group is often called, are attracting a lot of attention. Four recent books offer perspectives on these Americans who seem to want some connection to the divine, but who don’t feel affiliated with traditional religion. There’s the minister who wants to woo them, two scholars who want to understand them and the psychotherapist who wants to help them.

The Rev. Lillian Daniel’s book “When ‘Spiritual But Not Religious’ Is Not Enough” (Jericho, 2013) began as a short essay for The Huffington Post, in which she voiced her exasperation with the predictability that she found in spiritual but not religious people.

“On airplanes,” Ms. Daniel wrote in the essay , in 2011, “I dread the conversation with the person who finds out I am a minister and wants to use the flight time to explain to me that he is ‘spiritual but not religious.’ Such a person will always share this as if it is some kind of daring insight, unique to him, bold in its rebellion against the religious status quo.” Before you know it, “he’s telling me that he finds God in the sunsets.”

“These people always find God in the sunsets,” Ms. Daniel said. “And in walks on the beach.”

The essay spread online, with thousands of Facebook “likes” and reposts. Ms. Daniel heard from so many people that she decided to expand her essay. In the book, Ms. Daniel, a Congregationalist preacher who is pastor at a church near Chicago, argues that spirituality fits too snugly with complacency, even hedonism — after all, who doesn’t like walks in nature? — whereas religion is better at challenging people to face death, fight poverty and oppose injustice. Religion, by bringing people together, in community, at regular intervals, facilitates an ongoing conversation about matters outside the self.

“The book is kind of for the person who in some ways is half in and half out of religion,” Ms. Daniel said in a recent interview. “They know it might be meaningful, but they don’t know how to make a case for it, or tell a story about the religious life that does not sound obnoxious or judgmental.”

Ms. Daniel, by contrast, makes the case forcefully, seemingly unworried about those she might offend.

“Being privately spiritual but not religious just doesn’t interest me,” she writes. “There is nothing challenging about having deep thoughts all by oneself. What is interesting is doing this work in community, where other people might call you on stuff or, heaven forbid, disagree with you. Where life with God gets rich and provocative is when you dig into a tradition that you did not invent all for yourself.”

But Linda A. Mercadante, who teaches at the Methodist Theological School in Ohio contests that description of the spiritual but not religious. In “Beliefs Without Borders: Inside the Minds of the Spiritual but Not Religious” (Oxford), published in March, she makes the case that spiritual people can be quite deep theologically.

An ordained Presbyterian minister whose father was Catholic and whose mother was Jewish, Dr. Mercadante went through a spiritual but not religious period of her own — although she now attends a Mennonite church. For her project, she interviewed 85 S.B.N.R.s, then used computer programs to help analyze transcripts of those interviews. She found that these spiritual people also thought about death, the afterlife and other profound subjects.

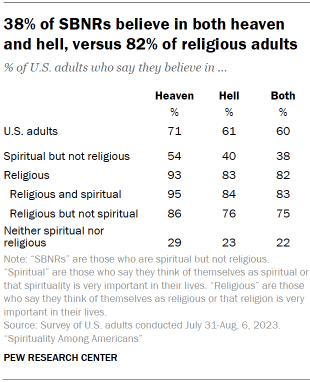

For example, “they reject heaven and hell, but they do believe in an afterlife,” Dr. Mercadante said recently. “In some ways, they would fit O.K. in a progressive Christian context.” Because they dislike institutions, the spiritual but not religious also recoil from the deities such institutions are built around. “They may like Jesus, he might be their guru, he might be one of their many bodhisattvas, but Jesus as God is not on their radar screen,” Dr. Mercadante said.

When Courtney Bender, now teaching at Columbia, went looking for spiritual but not religious people in Cambridge, Mass., where she was then living, she found them not on solitary nature walks but in all sorts of groups — which complicates the stereotype of them as anti-institutional loners. She described her findings in “The New Metaphysicals: Spirituality and the American Religious Imagination” (Chicago, 2010).

They “participated in everything from mystical discussion groups to drumming circles to yoga classes,” Dr. Bender said in an interview. And her finding that spirituality “is not sui generis,” but rather learned in communities that persist over time, actually runs contrary to spiritual people’s conceptions of themselves, she said. “There is something in the theology of spiritual groups that actually refocuses their practitioners from thinking about how they fit into a long continuous spirituality.”

In other words, their self-image “makes them think, ‘I don’t need history, I don’t need the past,’ ” Dr. Bender said, adding that they think, “I am not religious, which is about the past — I am spiritual, about the present.”

Yet people who call themselves spiritual are actually embedded in communal practices, albeit not churches or religious denominations. Dr. Bender found them in “alternative and complementary medicine,” for example. “So people would encounter this stuff in the shiatsu massage clinic, or going to an acupuncturist,” she said.

“Another one that is very important is the arts,” she added. “People involved in everything from painting and dance” would also end up discussing their conception of the divine.

So is spirituality solitary or communal? Is it theologically engaged or just focused on “nature” and “gratitude,” as Ms. Daniel worries? To judge from “A Religion of One’s Own: A Guide to Creating a Personal Spirituality in a Secular World” (Gotham, 2014), by Thomas Moore, whose “Care of the Soul” is one of the best-selling self-help books ever, spirituality can be whatever one makes it. In his guide to developing a custom spirituality, he encourages people to draw on religion, antireligion — whatever works for them.

“Every day I add another piece to the religion that is my own,” Dr. Moore writes. “It’s built on years of meditation, chanting, theological study and the practice of therapy — to me a sacred activity.”

At the very least, we might conclude that “spiritual but not religious” isn’t necessarily vague or wishy-washy. It’s not nothing, although it may risk being everything.

[email protected] Twitter: @markopp1

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Spirituality Among Americans

5. who are ‘spiritual but not religious’ americans, table of contents.

- Is spirituality increasing?

- Americans’ beliefs about spirits and the afterlife

- Spiritual experiences and practices

- How many Americans are spiritual?

- What do ‘spiritual but not religious’ people believe?

- Who says they are spiritual or religious?

- What does ‘spiritual’ mean?

- Belief that people have a soul or spirit

- Belief in God or a higher power

- Belief in other spirits or unseen forces

- Beliefs about the afterlife

- Spiritual and religious communities

- Having things for spiritual purposes

- Activities that create connection

- Regular experiences of wonder or connection

- Sudden encounters with the spiritual realm

- Demographic characteristics

- Spiritual beliefs and practices

- Spiritual experiences

- Change in personal spirituality over time

- Religion and society

- Acknowledgments

- Defining spiritual and religious categories

This chapter focuses on three groups of U.S. adults, based on their answers to the following four questions: Do you think of yourself as spiritual? Do you think of yourself as religious? How important is spirituality in your life? How important is religion in your life?

The three groups are:

- 22% of Americans who are categorized as spiritual but not religious (SBNR) because they say they think of themselves as spiritual or they consider spirituality very important in their lives, but they neither think of themselves as religious nor say religion is very important in their lives.

- 58% of Americans who fall into an overall or “NET” Religious category because they say they think of themselves as religious or they consider religion very important in their lives. This group can be subdivided into U.S. adults who are both religious and spiritual (48%) and those who are religious but not spiritual (10%)

- 21% of Americans who are categorized as neither spiritual nor religious because they don’t think of themselves as spiritual, don’t think of themselves as religious, don’t consider spirituality very important in their lives and don’t consider religion very important in their lives.

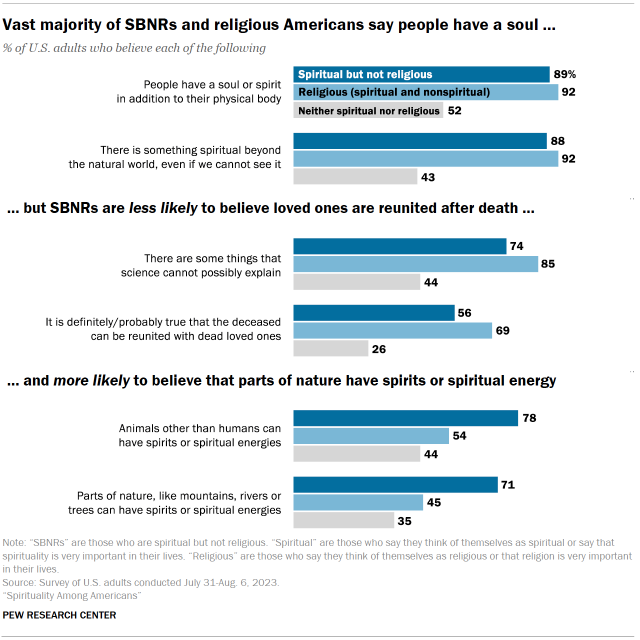

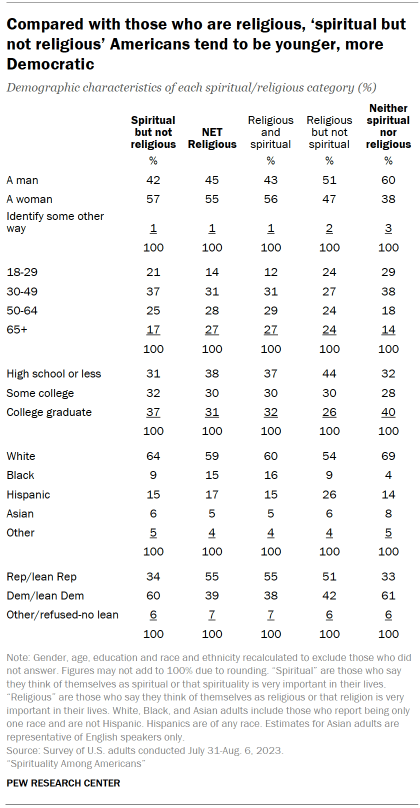

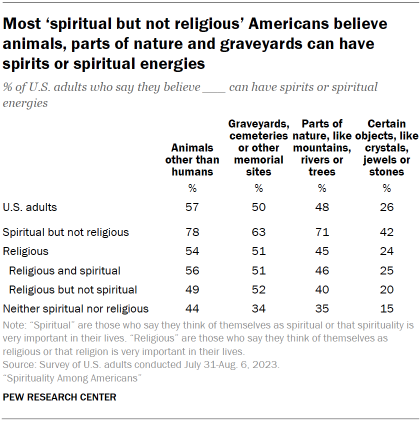

Most of the comparisons in this chapter are between the SBNR and the NET Religious categories. Compared with religious Americans, SBNRs tend to be younger, more likely to identify as Democrats or Democratic-leaning independents and less likely to affiliate with a religion. SBNRs also differ from religious Americans on some key measures of belief and practice analyzed in this report. For example, SBNRs are far more likely than religious adults to say they believe that spirits or spiritual energies can be contained in animals other than humans (78% vs. 54%) or in parts of nature like mountains, rivers or trees (71% vs. 45%).

On the other hand, SBNRs are less likely than religious adults to believe in God as described in the Bible (20% vs. 82%), pray daily (21% vs. 64%) or attend religious services at least once a week (2% vs. 36%.)

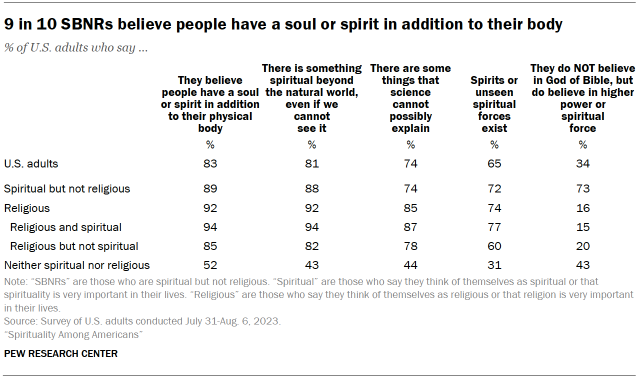

Still, SBNRs hold many beliefs in common with religious Americans. For example, most people in both groups believe that there is something spiritual beyond the natural world, even if we cannot see it (88% of SBNRs and 92% of the religious) and that human beings have a soul or spirit in addition to their physical body (89% and 92%, respectively).

This chapter discusses these findings in more detail and shows how SBNR Americans and religious Americans differ on some measures presented in previous chapters.

Compared with religious adults, SBNRs are relatively young (58% of adult SBNRs are under age 50, compared with 45% of religious Americans) and more likely to identify as Democrats or Democratic-leaning independents (60% vs. 39%). SBNRs and religious Americans are similar in their gender composition, with women accounting for a slight majority in each group. Demographically, Americans who are neither spiritual nor religious stand out for being comprised predominantly of men (60%).

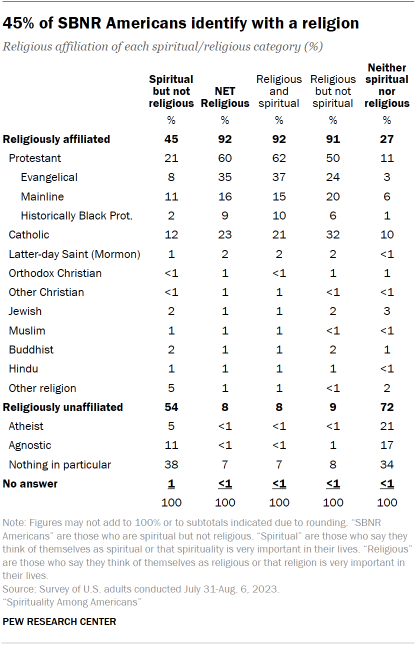

When it comes to religious identification, SBNR Americans are divided between affiliating with a religion (45%) and not affiliating with one (54%).

By contrast, the vast majority of religious Americans identify with a religion (92%), while most adults who are neither spiritual nor religious are religiously unaffiliated (72%).

The most common response that SBNR Americans give when asked to select a religious identity is “nothing in particular” (38%). About one-fifth of SBNRs identify as Protestant, and 12% identify as Catholic.

Some spiritual beliefs are widely shared by SBNRs and religious U.S. adults. For example, large shares of both SBNRs (89%) and religious Americans (92%) say they believe people have a soul or spirit in addition to their physical body. Most people in both groups also say that there is something spiritual beyond the natural world, even if we cannot see it (88% and 92%) and that spirits or unseen spiritual forces exist (72% and 74%).

However, SBNRs are somewhat less likely than religious Americans to say there are some things that science cannot possibly explain (74% vs. 85%).

Beliefs on where spirits reside

SBNRs are far less likely than religious Americans to believe in God as described in the Bible (20% vs. 82%). Instead, they are much more likely to say they believe there is “some other higher power or spiritual force in the universe” (73% vs. 16%).

Also, SBNR Americans are more likely than religious Americans to say that animals, memorial sites, parts of nature or certain objects can have spirits or spiritual energies. For example, 78% of SBNR Americans say that spirits or spiritual energies can reside in animals other than humans, compared with 54% of religious adults. And 71% of SBNR adults say spirits can reside in parts of nature like mountains, rivers or trees, compared with 45% of religious adults who hold this view. Fewer SBNRs say that objects like crystals, jewels or stones can have spirits or spiritual energies (42%). But that share is still larger than among religious Americans (24%).

SBNR Americans are much less likely than religious Americans to say they believe in heaven (54% vs. 93%) or hell (40% vs. 83%). But SBNRs are much more likely than Americans who are neither spiritual nor religious to believe in heaven and hell.

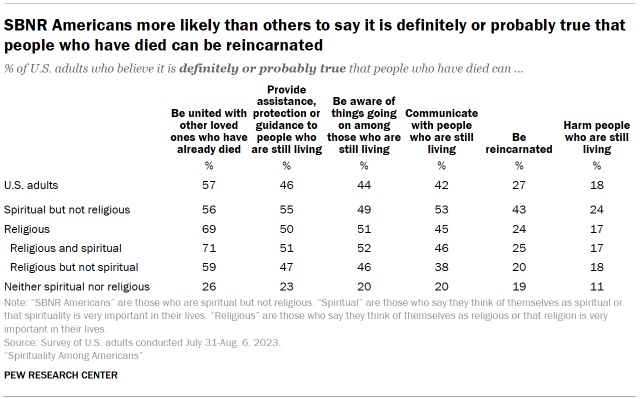

SBNRs also stand out for their beliefs about reincarnation: 43% say it is definitely or probably true that people who have died can be reborn again in this world, compared with 24% of religious Americans who express the same view. And there are some differences on other questions about the afterlife. For example, SBNRs are less likely than religious Americans to say that after people die, they definitely or probably can be reunited with loved ones who have already died (56% vs. 69%.)

But both SBNRs and religious Americans are much more likely than those who are neither spiritual nor religious to say that people who have died can be aware of things going on among the living, can communicate with the living and can help or harm the living.

Spiritual practices

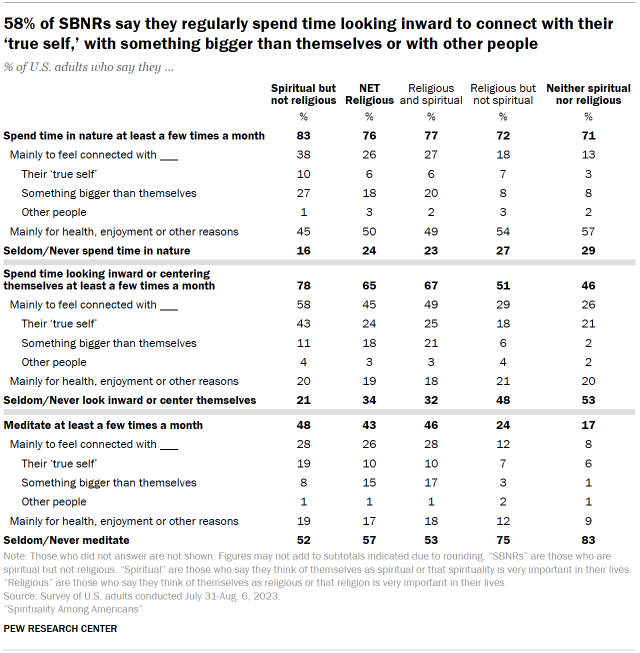

Nearly six-in-ten “spiritual but not religious” Americans (58%) say they spend time looking inward or centering themselves at least a few times a month mainly for connection, including 43% who do so primarily to connect with their “true self.” Fewer religious Americans and those who are neither spiritual nor religious say the same.

SBNRs are also more likely than religious Americans and those who are neither spiritual nor religious to report that they spend time in nature at least a few times a month for connection, especially in order to connect with something bigger than themselves.

But SBNRs are as likely as religious-and-spiritual Americans to say they meditate at least a few times a month primarily to foster connections (28% each).

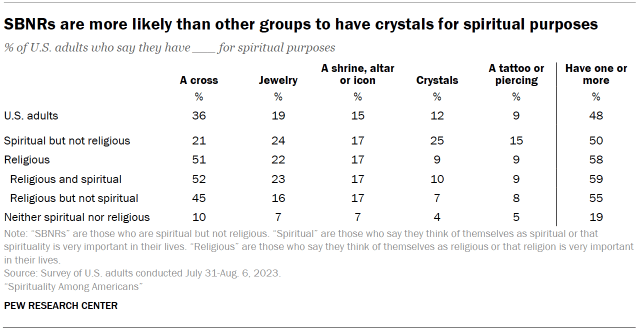

The new survey also asked whether people have a variety of things for spiritual purposes. SBNRs are notably less likely than religious Americans to say they have a cross (21% vs. 51%). But SBNRs are much more likely to say they own crystals (25% vs. 9%) and somewhat more likely to have a tattoo or piercing for spiritual purposes (15% vs. 9%). SBNRs and religious Americans are about equally likely to have a shrine, altar or icon in their home or to have jewelry for spiritual purposes.

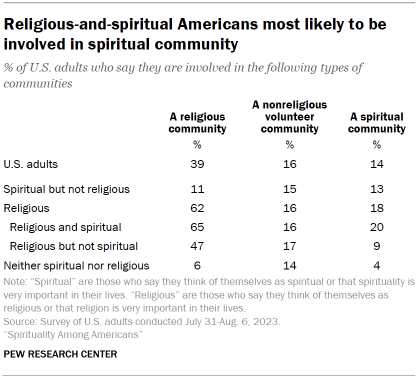

Involvement in communities

The survey asked respondents whether they are involved in three kinds of communities: a religious community “such as a church or religious congregation”; a spiritual community “such as a group that helps you find a connection with something bigger than yourself, nature or other people”; or a “nonreligious volunteer or community service group.” Respondents could indicate they belong to all, some or none of these kinds of communities.

SBNRs are much less likely than religious Americans to say they are involved in a religious community (11% vs. 62%). They are also slightly less likely to be involved in a spiritual community (13% vs. 18%), though that difference masks a split within the religious category: Americans who are both religious and spiritual are much more likely than those who are religious but not spiritual to say they are involved in a spiritual community (20% vs. 9%).

Meanwhile, the survey finds no significant difference between SBNRs and religious Americans, overall, in their propensity to be involved in a nonreligious volunteer or community service group.

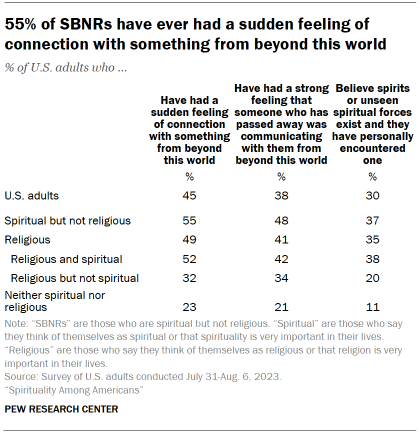

SBNRs are more likely than religious Americans (and U.S. adults as a whole) to have had a strong feeling that someone who has passed away was communicating with them from beyond this world: 48% of SBNRs say they have ever had such an experience, compared with 41% of religious Americans and 21% of U.S. adults who are neither spiritual nor religious.

SBNRs are also slightly more likely than religious Americans to say they have ever had a sudden feeling of connection with “something from beyond this world” (55% vs. 49%), but there is a substantial divide within the religious category: 52% of Americans who are both religious and spiritual say they have had such an experience, compared with 32% of those who are religious but not spiritual.

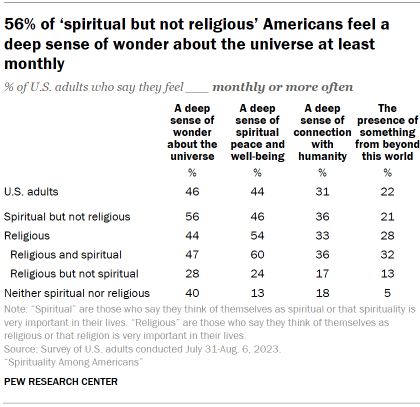

The same patterns hold when comparing SBNRs with religious Americans on some other questions about experiences that might be considered spiritual. SBNRs are more likely than religious Americans (and much more likely than those who are religious but not spiritual) to say they feel a deep sense of wonder about the universe once a month or more often.

On the other hand, SBNRs are somewhat less likely than religious Americans (and much less likely than those who are both religious and spiritual) to say they feel a deep sense of spiritual peace and well-being at least monthly.

( Chapter 4 shows the percentage of U.S. adults who report having these experiences at least a few times a year , rather than monthly or more often.)

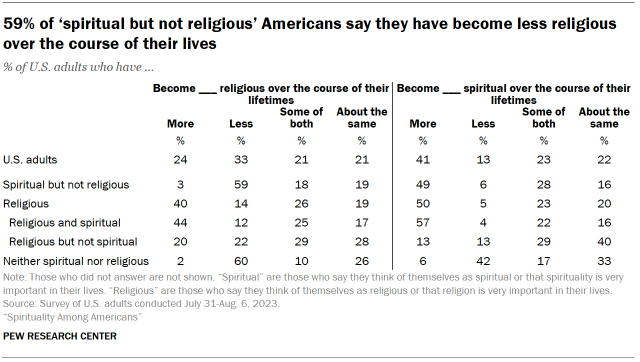

Most SBNRs say they have become less religious over the course of their lifetimes (59%). At the same time, 49% say they have become more spiritual over the years and 28% say their spirituality has fluctuated, sometimes increasing and other times decreasing.

By contrast, religious Americans are more likely to say that during their lifetimes, they have become more religious (40%) than to say they have become less religious (14%). Many religious Americans say they have either stayed about the same religiously (19%) or gone back and forth, sometimes becoming more religious and sometimes less (26%).

And religious Americans are just as likely as SBNRs to say they have become more spiritual over their lifetimes: 50% of religious Americans and 49% of SBNRs say this about themselves, while much smaller shares of both groups say they have become less spiritual (5% of religious Americans, 6% of SBNRs).

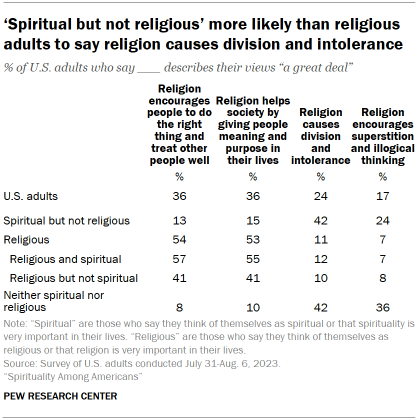

Spiritual but not religious Americans, along with those who are neither spiritual nor religious, are more critical than religious adults of religion’s impact on society. On balance, 38% of SBNRs say religion does more harm than good, while just 7% of religious Americans share this view.

SBNRs are also more likely than religious Americans to say that the statement “religion causes division and intolerance” describes their views a great deal (42% vs. 11%).

And SBNR Americans are less likely than religious adults to take the position that “religion encourages people to do the right thing and treat people well” (13% vs. 54%) and that “religion helps society by giving people meaning and purpose in their lives” (15% vs. 53%).

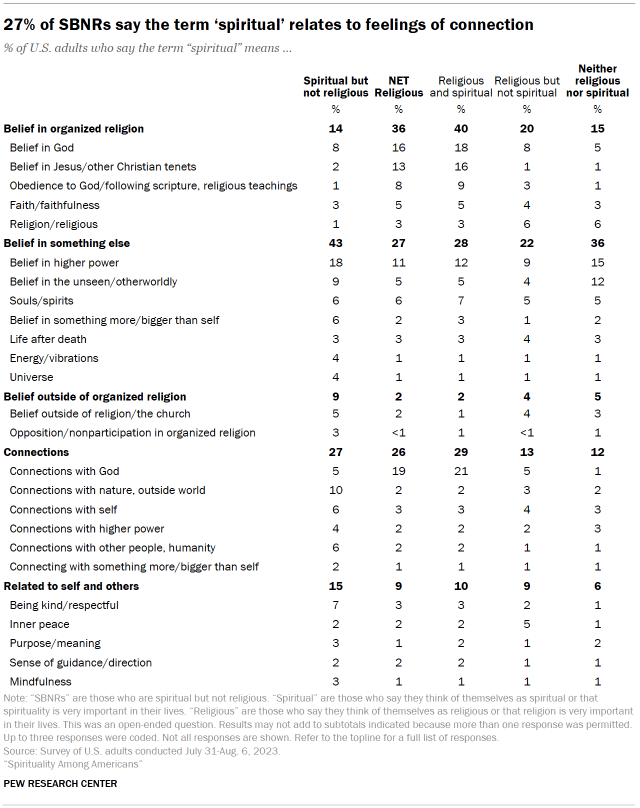

This survey also asked respondents to say, in their own words, what the term “spiritual” means to them. We categorized their responses based on the types of beliefs, experiences or other concepts they mentioned.

- 14% of SBNRs give descriptions tied to organized religion , compared with 36% of religious adults.

- About one-in-ten SBNRs relate spirituality to things outside of organized religion , compared with 2% of religious Americans.

- 43% of SBNRs offer responses that mention beliefs in what we categorized as “something else,” such as belief in a higher power (18%) or belief in the unseen or otherworldly (9%). Among religious adults, 27% relate spirituality to beliefs in “something else.”

- A sizable share of SBNRs (27%) also explain the term “spiritual” by referring to connections , such as with God, nature, their inner self or humanity in general. And 15% say “spiritual” relates to understanding themselves or guiding their own behavior , such as being kind or respectful.

Essential elements of spirituality

To further gauge how Americans think about spirituality, the survey asked those who are spiritual whether each of 10 items are “essential,” “important, but not essential,” or “not an important part” to what being spiritual means to them. And a follow-up question asked whether there is anything else they consider essential to what being spiritual means to them (refer to the Topline for responses).

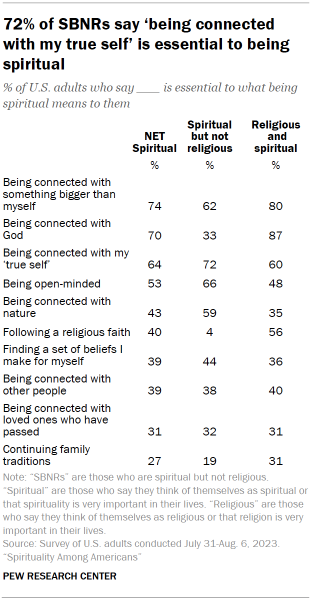

Most Americans who are spiritual but not religious say that “being connected with my true self” is essential to being spiritual (72%). Majorities also say “being open-minded” (66%), “being connected with something bigger than myself” (62%) and “being connected with nature” (59%) are essential. Religious-and-spiritual Americans, on the other hand, are most likely to say “being connected with God” is essential to being spiritual.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Atheism & Agnosticism

- Beliefs & Practices

- Death & Dying

- Happiness & Life Satisfaction

- Non-Religion & Secularism

- Religiously Unaffiliated

8 facts about atheists

Around 4 in 10 americans have become more spiritual over time; fewer have become more religious, chinese communist party promotes atheism, but many members still partake in religious customs, many people in u.s., other advanced economies say it’s not necessary to believe in god to be moral, unlike other u.s. religious groups, most atheists and agnostics oppose the death penalty, most popular, report materials.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

5 Spiritual but Not Religious?

- Published: December 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter examines how and why millions of people describe themselves as ‘spiritual but not religious.’ To do so it describes the relation between ‘spirituality’ and ‘religion’ by exploring different senses of the concept of truth, the nature of belief, and the role of individuality and personal choice in spiritual life. As well, it describes some of the common criticisms “spiritual but not religious” people make of traditional religion. The basic thesis of the chapter is that the practice of spiritual virtues can coexist with a detached or metaphorical understanding of traditional religious claims; that religious belief is defined by the practice of virtue more than by intellectual acceptance; and that the common criticisms of orthodox religion (e.g., that it can be repressive and violent) are true, but apply equally to secular movements and ideologies as well.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Spiritual, but not religious?: On the nature of spirituality and its relation to religion

- Published: 16 October 2017

- Volume 83 , pages 261–269, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

- Jeremiah Carey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5956-3068 1

1387 Accesses

12 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Recent years have seen a rise in those who describe themselves as “spiritual, but not religious”. At a popular level, there has been a lot of debate about this label and what it represents. But philosophers have in general paid little attention to the conceptual issues it raises. What is spirituality, exactly, and how does it relate to religion? Could there be a non-religious spirituality? In this paper, I try to give an outline account of the nature of spirituality and of religion, and then close with some thoughts on the prospects for a non-religious spirituality.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

What is Spirituality?

Santayana and Schopenhauer

- Spirituality

http://www.pewforum.org/2012/10/09/nones-on-the-rise-religion/ . For a relatively early treatment of the history of this phrase and the outlook it represents, see (Fuller 2001 ).

Gottlieb, himself a defender of what he calls “eclectic” and “secular” spirituality, quotes those who have called “the very idea of spirituality…an ‘inconsequential dabbling that is doomed to disappear almost as quickly as it appeared’, ‘a new cultural addiction and a claimed panacea for the angst of modern living’…a form of ‘junk capitalism’…[and] a kind of lazy egotism avoiding the demands of God and serious religion” (Gottlieb 2013 , p. 21).

For some of the story of its evolution, see (Bregman Bregman 2014 , Introduction and Chapter 1).

Thus, I think the ethical thought of all developed spiritual traditions is virtue-theoretical; that is, agent-centered rather than act-centered.

Different traditions, however, differ on how to understand the problem of the self. On the Buddhist view, for example, it may seem as if the basic problem depends on the false belief that there is a substantial self, whereas on the Christian view the problem is rather one of egotism, of being overly pre-occupied with the self to the exclusion of real love for others.

I talk about some these similarities, with a focus on Stoic, Christian, and Buddhist sources in my “Dispassion as an Ethical Ideal”.

Some doubt may be felt that Epicureanism could count as a spiritual tradition, since (a) they were materialists of a rather strong sort, thinking reality was ultimately nothing but atoms in a void, and (b) they thought that the ultimate good was pleasure (Thanks to David McNaughton for this worry). However, for the Epicureans, atoms in the void were sufficient to ground a spirituality insofar as they believed that rightly understanding and living in the light of this fundamental truth required a sort of inner transformation which would in turn lead to more ethical behavior and a more worthwhile life. Likewise, their pursuit of pleasure was conditioned by their understanding of the cosmos and human nature. It required, among other things, support for just social institutions, pursuit of friendship, and moderating one's appetites (far from the modern misconception of the Epicurean as an insatiable gourmand, it was originally a quasi-ascetical community and Epicurus himself was a vegetarian!).

The quote is from Murdoch ( 1994 ), whose ethical thought to my mind is an almost perfect expression in contemporary philosophical terms of a basic insight of many spiritual traditions.

My account here does not play up the importance of spiritual or mystical experiences, which may seem like a flaw. On the one hand, I don’t think such experiences, as such, are important to all spiritualities. On the other, however, I do think the idea of an inner transformation is important and such experiences may often be the catalysts for such transformations, or the experience of the transformations themselves. Thanks to Harriet Baber for forcing me to think about this.

For a recent dialogue on the definition of religion, see (Devine 1986 ) and (Kapitan 1989 ). Devine focuses mostly on deity and dogma (with ritual being a “less central” criteria), whereas Kapitan focuses mostly on ethics, broadly speaking (for him, religion is primarily about solving a sort of “uneasiness” in our existential condition). Tellingly, the word “spirituality” doesn’t show up at all in either treatment.

One potential worry here is that this is too broad an understanding, for we can imagine an alien explorer to our planet thinking similar things about our own relationship to, say, professional sports. On the one hand, I’ll admit that as it stands perhaps what I say is too broad—there may be additional requirements for such communal rituals to be considered religious, for example some sort of self-conscious understanding of what is happening as in some way sacred or necessary. On the other, I don’t want to entirely rule out the claim that our entertainment culture is at least something very close to a surrogate religion.

(Woods and Ironson 1999 ).

Cf. (Zinnbauer and Pargament 2003 , pp. 27–29), who is responding inter alia to the studies just mentioned.

And of course in the developed religions, the rites have both a communal character, as in communal prayer and worship or veneration, and a more individually-directed spiritual character. In the Eucharist, for example, Christians both share a communal meal in remembrance of Christ, and are said to be individually transformed by a real encounter with him.

Alston, W. (2006). Religion. In D. M. Borchet (Ed.), The encyclopedia of philosophy , (2nd ed., Vol. 8). Thomson Gale.

Bregman, L. (2014). The ecology of spirituality . Waco, TX: Baylor University Press.

Google Scholar

Carey, J. N. D. Dispassion as an ethical ideal. Unpublished manuscript.

Devine, P. E. (1986). On the definition of religion. Faith and Philosophy, 3, 270–284.

Article Google Scholar

Fuller, R. C. (2001). Spiritual, but not religious: Understanding unchurched America . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Gottlieb, R. S. (2013). Spirituality: What it is and why it matters . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hadot, P. (2002). What is ancient philosophy? . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kapitan, T. (1989). Devine on defining religion. Faith and Philosophy, 6, 207–214.

Murdoch, I. (1994). Metaphysics as a guide to morals . New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Walker, L. J., & Pitts, R. C. (1998). Naturalistic conceptions of moral maturity. Developmental Psychology, 34, 403–419.

Woods, T. E., & Ironson, G. H. (1999). Religion and spirituality in the face of illness: How cancer, cardiac, and HIV patients describe their spirituality/religiosity. Journal of Health Psychology, 4, 393–412.

Zinnbauer, B. J., & Pargament, K. I. (2003). Religiousness and spirituality. In R. F. Paloutzian & C. L. Park (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality . New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Philosophy Department, Siena College, Siena Hall 412, 515 Loudon Road, Loudonville, NY, 12211, USA

Jeremiah Carey

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jeremiah Carey .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Carey, J. Spiritual, but not religious?: On the nature of spirituality and its relation to religion. Int J Philos Relig 83 , 261–269 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11153-017-9648-8

Download citation

Received : 24 August 2017

Accepted : 13 October 2017

Published : 16 October 2017

Issue Date : June 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11153-017-9648-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Controversy in Society: Spiritual But Not Religious Essay (Critical Writing)

Initially, the article highlights that a significant number of people today call themselves “spiritual but not religious,” a phrase that tends to spark controversy in society (Burkeman par. 1). One of the followers of this movement is Sam Harris, who refers to the fact that spirituality, along with the assistance of meditation, helps him become happy and feel that the world is a part of him (Burkeman par. 2).

The primary difference between spirituality and religion is the fact that spirituality does not have a set of principles and dogmas that one has to follow during his or her life (Burkeman par. 3). It gives an opportunity for atheists to be “present” and experience different forms of life without any fear. Thus, the author of the article claims that Harris’ ideas might be egocentric, as the majority of religious believers rely on practice and he was “baffled” by the question of whether God exists and was engaged in rituals to feel “present” (Burkeman par. 4).

As for me, I believe that spirituality does differ from religion. I completely agree with the fact that religion requires one to comply with set dogmas and principles. A particular figure of God is a role model that one has to follow. On the other hand, spirituality is a self-centered practice since it focuses on the inner world of individuals and gives them the right to become close to the “present.” In this case, Harris’ argument is logical, but I also believe that he should not criticize religion in public. Overall, spirituality is strongly related to religion and disrespecting religion questions one’s ability to admire the beliefs and values of other people. In this case, modern society should allow people to represent their own sense of religion and spirituality, as these concepts contribute to the development of tolerance and personal growth.

Burkeman, Oliver. “Spiritual but Not Religious? You Are Not Alone.” The Guardian. 2016.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, August 25). Controversy in Society: Spiritual But Not Religious. https://ivypanda.com/essays/controversy-in-society-spiritual-but-not-religious/

"Controversy in Society: Spiritual But Not Religious." IvyPanda , 25 Aug. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/controversy-in-society-spiritual-but-not-religious/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Controversy in Society: Spiritual But Not Religious'. 25 August.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Controversy in Society: Spiritual But Not Religious." August 25, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/controversy-in-society-spiritual-but-not-religious/.

1. IvyPanda . "Controversy in Society: Spiritual But Not Religious." August 25, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/controversy-in-society-spiritual-but-not-religious/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Controversy in Society: Spiritual But Not Religious." August 25, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/controversy-in-society-spiritual-but-not-religious/.

- Philosophy Reading Reflection: "Annihilation" by Steven Luper

- The core teaching of Jesus

- Intersectionality in Domestic Violence

- "Jesus and the Disinherited" by Howard Thurman

- "Strength to Love" and the American Religious Experience

- The Battle for God: Fundamentalism in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam

- Religious Studies: Women in the Old Testament

- The Book "Following Muhammad" by Carl Ernst

Fisher Digital Publications

Home > Verbum > Vol. 6 > Iss. 2 (2009)

Article Title

Can One Be Spiritual But Not Religious?

Roger Haight , St. John Fisher University Follow

Document Type

Religious Studies Department Speaker Series

In lieu of an abstract, below is the essay's first paragraph.

"How many times have you heard the statement that "I am spiritual, but not religious." It is so common that it could easily qualify as a contemporary cliché. But what does it mean? In a former time to be spiritual was to be religious: they meant pretty much the same thing. Today, however, spirituality can refer to a hundred different things, from self-care to mysticism, from yoga to a psychological power of positive thinking. And the diversity of the different kinds of religion, from the recognized world religions to emergent communities, is staggering. So one cannot take for granted that we know what the self-description really means."

Recommended Citation

Haight, Roger (2009) "Can One Be Spiritual But Not Religious?," Verbum : Vol. 6: Iss. 2, Article 19. Available at: https://fisherpub.sjf.edu/verbum/vol6/iss2/19

Additional Files

Since September 11, 2014

Included in

Religion Commons

- Journal Home

- Editorial Board

- Most Popular Papers

Advanced Search

Home | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Featured Webcast

The State of Pastors Summit

Replay the free webcast to explore six trends shaping the future of pastoral leadership. Discover how pastors are doing, along with brand new findings from Barna's brand new research report, The State of Pastors, Volume 2. Watch the replay for free today.

Featured Report

The State of Pastors, Volume 2

This report takes an in-depth look at how pastors are navigating post-pandemic life and ministry, focusing on self-leadership, church leadership and cultural leadership.

Featured Podcast

The Resilient Pastor

Join pastors Glenn Packiam, Rich Villodas and Sharon Hodde Miller as they invite leaders to think out loud together about the challenges and opportunities of leading a church in a rapidly changing world. In each episode, they will have a conversation about church leadership and the challenges pastors are facing. Then, they’ll share a conversation with a pastor, church leader, thinker or theologian about the health of the pastor, the state of the church and what it looks like to love well and lead faithfully.

Featured Service

Custom Research with Barna

Partner with Barna on customized research projects. Gain knowledge to understand the unique needs of your ministry.

Get full access to Barna insights, research & more

Apr 6, 2017

Meet the “Spiritual but Not Religious”

I’m spiritual but not religious.” You’ve heard it—maybe even said it—before. But what does it actually mean? Can you be one without the other? Once synonymous, “religious” and “spiritual” have now come to describe seemingly distinct (but sometimes overlapping) domains of human activity. The twin cultural trends of deinstitutionalization and individualism have, for many, moved spiritual practice away from the public rituals of institutional Christianity to the private experience of God within . In this conclusion of a two-part series on faith outside the church ( read the first part, on those who “love Jesus but not the church” ), Barna takes a close look at the segment of the American population who are “spiritual but not religious.” Who are they? What do they believe? How do they live out their spirituality daily?

Barna Access Plus

Strengthen your message, train your team and grow your church with cultural insights and practical resources, all in one place.

Two Types of Irreligious Spirituality To get at a sense of spirituality outside the context of institutional religion, Barna created two key groups that fit the “spiritual but not religious” (SBNR) description. The first group (SBNR #1) are those who consider themselves “spiritual,” but say their religious faith is not very important in their life. Though some may self-identify as members of a religious faith (22% Christian, 15% Catholic, 2% Jewish, 2% Buddhist, 1% other faith), they are in many ways irreligious —particularly when we take a closer look at their religious practices. For instance, 93 percent haven’t been to a religious service in the past six months. This definition accounts for the unreliability of affiliation as a measure of religiosity.

A sizable majority of the SBNR #1 group do not identify with a religious faith at all (6% are atheist, 20% agnostic and 33% unaffiliated). In order to get a better sense of whether or not a faith affiliation (even if one is irreligious) might affect people’s views and practices, we created a second group of “spiritual but not religious,” which focuses only on those who do not claim any faith at all (SBNR #2). This group still says they are “spiritual,” but they identify as either atheist (12%), agnostic (30%) or unaffiliated (58%). For perspective, of all those who claim “no faith,” around one-third say they are “spiritual” (34%). This is a stricter definition of the “spiritual but not religious,” but as we’ll see, both groups share key qualities and reflect similar trends despite representing two different kinds of American adults—one more religiously literate than the other. In other words, it does not seem as if identifying with a religion affects the practices and beliefs of these groups. Even if you still affiliate with a religion, if you have discarded it as a central tenet of your life, it seems to hold little sway over your spiritual practices.

These two groups differ from the “love Jesus but not the church” crowd in significant ways. Those who Barna defined as loving Jesus but not the church still strongly identify with their faith (they say their religious faith is “very important in my life today”), they just don’t attend church. This group still holds very orthodox Christian views of God and maintains many of the Christian practices (albeit individual ones over corporate ones). As we’ll see below, though, the “spiritual but not religious” hold much looser ideas about God, spiritual practices and religion.