Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Exceptional and Innovative Programs in Educational Leadership

2002, Educational Administration Quarterly

Related Papers

Educational Administration Quarterly

Michelle Young

Rodney S Whiteman

This article is a summary of a report prepared for the University Council for Educational Administration Program Improvement Project for the Wallace Foundation. This explores the research base for educational leadership preparation programs, specifically examining literature on program features. The review covers context, candidates, faculty, curriculum, design, delivery, pedagogy, internships, student assessment, mentoring and coaching, comprehensive leadership development, and program evaluation. In addition to summarizing the major findings in these program feature areas, the article provides a critical evaluation of the substantive and methodological gaps and future research directions.

Kristina A Hesbol

Michelle D. Young

Educational leadership: knowing the way, showing …

Ncpea Publications

Linda Lemasters

Michelle D. Young , Mary Canole

Kristina Hesbol

RELATED PAPERS

Stanton Lawrence

Educational Leadership and Administration Teaching and Program Development

Robert Kladifko , Jody Dunlap

Crediting the Past, Challenging the Present, …

Theodore Creighton

Linda Lemasters , Frederick Dembowski

Jeffrey S Brooks

Synergy: A Journal for Graduate Student Research, 2(3).

Dr. Daniel Eadens

Linda Vogel

Matthew Militello

Rebeca Burciaga

University Council For Educational Administration

Planning and Changing

Linda Vogel , Kathryn Whitaker

george baldoria

Scholar Commons

Michael J Boyle , Alicia Haller

UCEA Review

Nathern Okilwa

Journal of Research on Leadership …

John M . Weathers, PhD.

School Leadership and Management

Charles Vanover , Olivia Hodges

Journal of Research on Leadership Education

Bradley Carpenter

Julie A . Gray

NASSP Bulletin

Carol Mullen

Paula Cordeiro

Julie P Combs

Yearbook of the National …

Diana G Pounder , Michelle D. Young

Ericka Hollis

Heather A. Cole

University Council for Education Administration Review

Keith E Benson

Miles Bryant

edb.utexas.edu

Leadership in Diverse Learning Contexts | Greer Johnson | Springer https://www.springer.com/us/book/9783319283005

Ira Bogotch

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Teaching and Teacher Leadership

Contact Information

Connect with program staff.

If you have program-specific questions, please contact the TTL Program Staff .

- Connect with Admissions

If you have admissions-related questions, please email [email protected] .

Admissions Information

- Application Requirements

- Tuition and Costs

- International Applicants

- Recorded Webinars

- Download Brochure

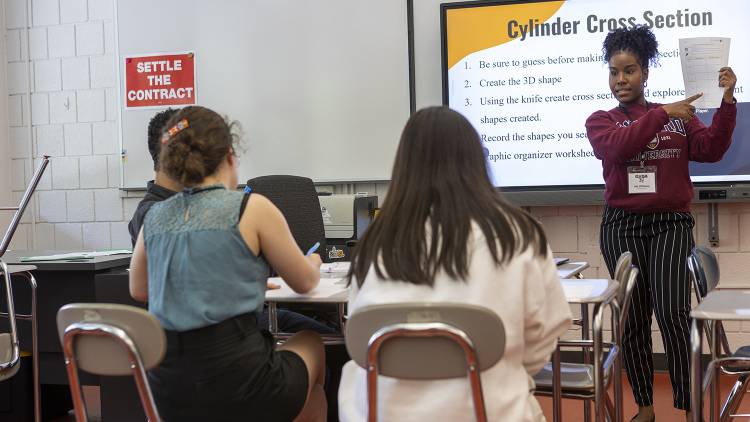

A groundbreaking approach to teacher education — for people seeking to learn to teach, for experienced teachers building their leadership, and for all educators seeking to enhance their practice and create transformative learning opportunities.

Teachers change lives — and at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, you can be part of the change. The Teaching and Teacher Leadership (TTL) Program at HGSE will prepare you with the skills, knowledge, support, and professional network you need to design and lead transformative learning experiences, advance equity and social justice, and generate the best outcomes for students in U.S. schools.

The program’s innovative approach is intentionally designed to serve both individuals seeking to learn to teach and experienced teachers who are deepening their craft as teachers or developing their leadership to advance teaching and learning in classrooms, schools, and districts.

And through the Harvard Fellowship for Teaching , HGSE offers significant financial support to qualified candidates to reduce the burden of loan debt for teachers.

Applicants will choose between two strands:

- Do you want to become a licensed teacher? The Teaching Licensure strand lets novice and early-career teachers pursue Massachusetts initial licensure in secondary education, which is transferrable to all 50 states and Washington, D.C. Licensure candidates have two possible pathways — you can select a preference for either the residency fieldwork model or the internship fieldwork model . The residency model is for people ready to make an immediate impact as a teacher; the internship model offers a more gradual path.

- Do you want to focus on the art of teaching, without licensure? The Teaching and Leading strand will enable you to enhance your own teaching practice or to lead others in transforming learning in classrooms, schools, and other settings. Candidates can pursue a curriculum tailored toward an exploration of teaching practice or toward teacher leadership.

Note: Ideal candidates will come with the intention to work in U.S. schools.

“At the heart of TTL is helping teachers reach all students. Whether you are preparing for the classroom yourself or are an experienced teacher preparing to improve teaching and learning on a wider scale, our goal is to provide you with the knowledge and skills to lead others in learning.” Heather Hill Faculty Co-Chair

After completing the Teaching and Teacher Leadership Program, you will be able to:

- Leverage your knowledge and skills to lead others in joyful, equitable, rigorous, and transformative learning.

- Analyze instruction for the purpose of improving it.

- Foster productive inquiry and discussion.

- Identify, understand, and counteract systemic inequities within educational institutions.

The Harvard Fellowship for Teaching

HGSE is committed to investing in the future of the teaching profession — and minimizing the student debt that teachers carry. We offer a signature fellowship — the Harvard Fellowship for Teaching — to qualified candidates. The fellowship package covers 80 percent of tuition and provides for a $10,000 living stipend.

This prestigious fellowship is prioritized for admitted students pursuing the Teaching Licensure Residency model. Additional fellowships may be awarded to qualified candidates admitted to the Teaching Licensure Internship model and the Teaching and Leading strand. Fellowship decisions are determined during the admissions process. Fellowship recipients must be enrolled as full-time students. HGSE offers a range of other financial aid and fellowship opportunities to provide greater access and affordability to our students.

Curriculum Information

The TTL Program is designed to help you gain the knowledge and practice the skills essential to leading others in learning — and will create pathways to success that will allow you to thrive as an expert practitioner and mentor in your community. A minimum of 42 credits are required to graduate with an Ed.M. degree from HGSE.

The main elements of the curriculum are:

- Commence your Foundations studies with How People Learn, an immersive online course that runs June–July and requires a time commitment of 10–15 hours per week.

- You will continue Foundations with Leading Change, Evidence, and Equity and Opportunity on campus in August.

- Your Equity and Opportunity Foundations experience culminates in an elected course, which will take place during terms when electives are available.

To fulfill the program requirement, students must take a minimum of 12 credits specific to TTL.

- The TTL Program Core Experience (4 credits), is a full year course where all students come together to observe, analyze, and practice high-quality teaching.

- Teaching methods courses (10 credits) in the chosen content area, which begin in June.

- A Summer Field-Based Experience (4 credits), held on site in Cambridge in July, allows you to begin to hone your teaching practice.

- Two courses focused on inclusivity and diversity in the classroom (6 credits).

- Field experiences , where students in the Teacher Licensure strand will intern or teach directly in Boston-area schools.

- Individuals interested in enhancing their own teaching practice can engage in coursework focused on new pedagogies, how to best serve diverse student populations, and special topics related to classrooms and teaching.

- Experienced teachers may wish to enroll in HGSE’s Teacher Leadership Methods course, designed to provide cohort-based experience with skills and techniques used to drive adult learning and improve teaching.

- Candidates can take elective coursework based on interests or career goals, which includes the opportunity to specialize in an HGSE Concentration .

Advancing Research on Effective Teacher Preparation

As a student in the TTL Program, you will have the opportunity to contribute to HGSE’s research on what makes effective teacher preparation. This research seeks to build an evidence base that contributes to the field’s understanding of effective approaches to teacher training, including how to support high-quality instruction, successful models of coaching and mentorship, and effective approaches to addressing the range of challenges facing our students.

TTL students will be able to participate in research studies as part of their courses, and some will also serve as research assistants, gaining knowledge of what works, as well as a doctoral-type experience at a major research university.

Explore our course catalog . (All information and courses are subject to change.)

Note: The TTL Program trains educators to work in U.S. classrooms. Required coursework focuses on U.S. examples and contexts.

Teaching Licensure Strand

Students who want to earn certification to teach at the middle school and high school levels in U.S. schools should select the Teaching Licensure strand. TTL provides coursework and fieldwork that can lead to licensure in grades 5–8 in English, general science, history, and mathematics, as well as grades 8–12 in biology, chemistry, English, history, mathematics, and physics. In the Teaching Licensure strand, you will apply to one of two fieldwork models:

- The residency model – our innovative classroom immersion model, with significant funding available, in which students assume teaching responsibilities in the September following acceptance to the program.

- The internship model – which ramps up teaching responsibility more gradually.

In both models, you will be supported by Harvard faculty and school-based mentors — as well as by peers in the TTL Program, with additional opportunities for network-building with HGSE alumni. Both models require applicants to have an existing familiarity with U.S. schools to be successful. Learn more about the differences between the residency and internship models.

Summer Experience for Teaching Licensure Candidates

All students in the Teaching Licensure strand will participate in the Summer Experience supporting the Cambridge-Harvard Summer Academy (CHSA), which takes place in Cambridge in July 2023. Through your work at CHSA, you will help middle and high school students in the Cambridge Public Schools with credit recovery, academic enrichment, and preparation for high school. Students in the Teaching Licensure strand will teach students directly as part of the teaching team. This is an opportunity for you to immediately immerse yourself in a school environment and begin to practice the skills necessary to advance your career.

Teaching and Leading Strand

The Teaching and Leading strand is designed for applicants who want to enhance their knowledge of the craft of teaching or assume roles as teacher leaders. Candidates for the Teaching and Leading strand will share a common interest in exploring and advancing the practice of effective teaching, with the goal of understanding how to improve learning experiences for all students. The program will be valuable for three types of applicant:

- Individuals interested in teaching, but who do not require formal licensure to teach. This includes applicants who might seek employment in independent schools or in informal educational sectors such as arts education, after-school programs, tutoring, and youth organizations.

- Experienced teachers who wish to deepen their practice by learning new pedagogies and developing new capacities to help students thrive.

- Experienced teachers who seek leadership roles — from organizing school-based initiatives to more formal roles like coaching and professional development.

As a candidate in the Teaching and Leading strand, your own interests will guide your journey. If you are seeking a teacher leader role, TTL faculty will guide you to courses that focus on growing your skills as a reflective leader, preparing you to facilitate adult learning, helping you understand how to disrupt inequity, and teaching you how to engage in best practices around coaching, mentoring, and data analysis. If you are seeking to learn about the craft of teaching, our faculty will similarly direct you to recommended courses and opportunities that will meet your goals.

Students in this strand can also take on internships within the TTL Program (e.g., program supervisor, early career coach) or the HGSE community, and at surrounding schools or organizations. And you can customize your learning experience by pursuing one of HGSE's six Concentrations .

Note: Applicants in the Teaching and Leading strand should expect a focus on leadership within U.S. schools.

Program Faculty

Students will work closely with faculty associated with their area of study, but students can also work with and take courses with faculty throughout HGSE and Harvard. View our faculty directory for a full list of HGSE faculty.

Faculty Co-Chairs

Heather C. Hill

Heather Hill studies policies and programs to improve teaching quality. Research interests include teacher professional development and instructional coaching.

Victor Pereira, Jr.

Victor Pereira's focus is on teacher preparation, developing new teachers, and improving science teaching and learning in middle and high school classrooms.

Rosette Cirillo

Sarah Edith Fiarman

Noah Heller

Eric Soto-Shed

Career Pathways

The TTL Program prepares you for a variety of career pathways, including:

Teaching Licensure Strand:

- Licensed middle or high school teacher in English, science, math, and history

Teaching and Leading Strand:

- Classroom teachers

- Curriculum designers

- Department heads and grade-level team leaders

- District-based instructional leadership team members

- Instructional and curriculum leadership team members

- Out-of-school educators; teachers in youth organizations or after-school programs

- Professional developers and content specialists

- School improvement facilitators

- School-based instructional coaches and mentor teachers

- Teachers of English as a second language

- International educators seeking to understand and advance a career in U.S. education

Cohort & Community

The TTL Program prioritizes the development of ongoing teacher communities that provide continued support, learning, and collaboration. Our cohort-based approach is designed to encourage and allow aspiring teachers and leaders to build relationships with one another, as well as with instructors and mentors — ultimately building a strong, dynamic network.

As a TTL student, you will build a community around a shared commitment to teaching and teacher development. You will learn from and with colleagues from diverse backgrounds, levels of expertise, and instructional settings. To further connections with the field, you are invited to attend “meet the researcher” chats, engage in learning through affinity groups, and interact with teaching-focused colleagues across the larger university, by taking courses and participating in activities both at HGSE and at other Harvard schools.

Introduce Yourself

Tell us about yourself so that we can tailor our communication to best fit your interests and provide you with relevant information about our programs, events, and other opportunities to connect with us.

Program Highlights

Explore examples of the Teaching and Teacher Leadership experience and the impact its community is making on the field:

Donors Invest in Teachers, Reaching Key Milestone

The $10 million Challenge Match for Teachers, now complete, will expand scholarships for students in Teaching and Teacher Leadership

HGSE Honors Master's Students with Intellectual Contribution Award

Ideas & Impact

The latest education research, actionable strategies, and innovation from the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Black Teacher Archive Enters New Phase with Grant Awards

The next phase of the project, led by Professor Jarvis Givens and Radcliffe's Imani Perry, will support new research and fill in gaps in the archive's collection

How to Sustain Black Educators

New book emphasizes need to advance beyond workforce diversity efforts focused purely on recruitment and retention

Nonie Lesaux Named HGSE Interim Dean

Professor of education and former academic dean will begin her role at the end of the academic year

'Cradle-To-Career' Success and the 'Vaccine to Poverty'

The final Askwith Education Forum of the academic year featured a standout panel of "cradle-to-career" innovators

'Talking Straight' Highlights How Art and Education Bridge Divides

The discussion centered on open dialogue about the conflict in Israel and Palestine

Summer Unplugged

Navigating screen time and finding balance for kids

The Road to Higher Education

Stories on access, equity, and achieving post-secondary success

How to Survive Financial Aid Delays and Avoid Summer Melt

A pre-matriculation checklist can help high school seniors persist with their college dreams

Strategies for Leveling the Educational Playing Field

New research on SAT/ACT test scores reveals stark inequalities in academic achievement based on wealth

Building Diverse College Communities

How higher education has reacted to the end of affirmative action and the path forward for equity

The Trying Transfer

Can School Counselors Help Students with "FAFSA Fiasco"?

Support for low-income prospective college students and their families more crucial than ever during troubled federal financial aid rollout

Higher Education's Resistance to Change

Visiting Professor Brian Rosenberg addresses the cultural and structural factors that impede significant transformations in higher education

In the Media

Commentary, thought leadership, and expertise from HGSE faculty

"Every child has the right to read well. Every child has the right to access their full potential. This society is driven by perfectionism and has been very narrow-minded when it comes to children who learn differently, including learning disabilities."

Shaping the Future of Education

From research projects to design labs, discover how HGSE is at the forefront of innovation in education.

Public Education Leadership Project

Works to improve leadership competencies of public school administrators through professional development to drive greater educational outcomes

Immigration Initiative at Harvard

Advances interdisciplinary scholarship and hands-on research about immigration policy and immigrant communities

Reach Every Reader

Develops tools to support the vision that all children can develop the skills, knowledge, and interest to become lifelong readers

Explore More Topics

HGSE research, coursework, and expertise ranges widely across education topics. Browse the full list of topics or view our in-depth coverage of Climate Change and Education.

- College Access and Success

- Counseling and Mental Health

- Disruption and Crises

- Early Education

- Evidence-Based Intervention

- Global Education

- Higher Education Leadership

- Language and Literacy Development

- Moral, Civic, and Ethical Education

- Teachers and Teaching

- Technology and Media

Search for a topic, trending issue, or name

Harvard Ed. Magazine

The award-winning alumni magazine, covering timely education stories that appeal to the Harvard community and the broader world.

Harvard EdCast

Harvard’s flagship education podcast, acting as a space for education-related discourse with thought leaders in the field of education.

The latest education research, strategies, and perspectives from the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Usable Knowledge

Translating new research into easy-to-use strategies for teachers, parents, K-12 leaders, higher ed professionals, and policymakers.

Jack N. Averitt College of Graduate Studies

Educational Leadership, Ed.D. (Online)

About the program.

Format : Online Credit Hours : 36 – 69 Entry Term : Fall

The Doctor of Education Degree program in Educational Leadership is designed to enhance the experienced school administrator’s leadership skills through: (1) advanced preparation that strengthens decision-making, problem-solving, and leadership skills essential to the management of increasingly complex educational organizations, and (2) engagement in guided field research that develops the inquiry skills necessary for effective leadership and management practice.

The program uses an inquiry approach that employs problem-solving and research skills applicable to multiple problems and issues. The purpose is to generate an inquiry orientation so that participants will learn to solve problems from broad perspectives. Participants identify, diagnose, and define problems, analyze their component parts contextually and systematically, and develop solutions that are immediately applicable and that deal with underlying issues. Experiences over the course of the doctoral program in Educational Leadership become candidate-led, field-based investigations of educational problems and potential solutions.

The Ed.D. in Educational Leadership provides two concentration options: P-12 Educational Leadership Higher Education Leadership

Ready to Apply?

Request information, visit campus, or, you can :, admission requirements.

- Select a concentration : Higher Education Leadership or P-12 Educational Leadership

- For admission to Stage I, candidates must possess a master’s degree. For admission to Stage II, candidates must possess a terminal degree in a related field.

- There is no admission into Stage I. For admission to Stage II, candidates must possess an Ed.S. degree in Educational Leadership or another related field and certification in Educational Leadership – Tier II.

- Present a minimum grade point average of 3.25 (4.0 scale) in previous graduate work.

- Submit a current resume or CV that highlights the personal and professional achievements of the applicant.

- Submit a personal statement of purpose, not to exceed 1000 words, that identifies the applicant’s reasons for pursuing graduate study and how admission into the program relates to the applicant’s professional aspirations.

- Submit a completed “Disclosure and Affirmation Form” that addresses misconduct disclosure, the Code of Ethics for Educators, and tort liability insurance.

- Complete a writing sample if requested.

- Complete an interview if requested.

*International transcripts must be evaluated by a NACES accredited evaluation service and must be a course by course evaluation and include a GPA. ( naces.or g )

NOTE: Meeting admission or qualification criteria does not guarantee admissions.

Final: April 1

Does not admit

*The application and all required documents listed on the “admissions requirements” tab for the program must be received by the deadline. If all required documents are not received by the deadline your application will not be considered for admission.

Program Contact Information

Graduate Academic Services Center [email protected] 912-478-1447

Last updated: 6/29/2023

- Preferred Graduate Admissions

- All Graduate Programs

- Certificate Programs

- Endorsement Programs

- Online Programs

- Tuition Classification

- Graduate Assistantships

- Financial Aid

- Request More Information

- Schedule A Visit

Contact Information

Office of Graduate Admissions Physical Address: 261 Forest Drive PO Box 8113 Statesboro, GA 30460 Georgia Southern University Phone: 912-478-5384 Fax: 912-478-0740 gradadmissions @georgiasouthern.edu

Follow us on Facebook!

Georgia Southern University College of Graduate Studies

Office of Graduate Admissions • P.O. Box 8113 Statesboro, GA 30460 • 912-478-5384 • [email protected]

Privacy Overview

- Author Rights

- Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

- JOLE 2023 Special Issue

- Editorial Staff

- 20th Anniversary Issue

Defining Moral Leadership in Graduate Schools of Education

John Pijanowski, Ph.D. 10.12806/V6/I1/TF1

John Pijanowski, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor of Educational Leadership University of Arkansas

Fayetteville, AR [email protected]

This article explores how ethics education has evolved over the last 15 years in graduate schools of educational leadership. A review of previous studies showing an increased attention to ethics education is analyzed in the context of external pressures such as new NCATE standards, and the emerging role of moral psychology to inform how ethics is taught in other pre-professional college programs.

Introduction

Moral leadership has become an increasingly popular topic in the field of educational administration. It has been the focus of policy initiatives, accreditation standards and a body of research that emerged over the past fifteen years identifying moral leadership as a characteristic of high performing schools, particularly among high poverty schools (Fullan, 2003; Hodgkinson, 1991; Nucci, 2001; Sergiovanni, 1992; Sizer & Sizer, 1999; Starratt, 1991). However, the increased attention to moral leadership in schools has not shed much light on how to best teach moral leadership in the preparation of school administrators. The burst of interest since the early 1990s in developing moral leadership in schools has largely taken the form of identifying moral leadership as an important, in some cases critical, element of a strong school.

A resurgence of interest in moral leadership has been spurred on by anecdotal evidence that increasing pressures to meet student accountability measures brought on by state reform and the federally mandated No Child Left Behind Act have resulted in an increase of both fraud and unethical allocation of school resources (Pardini, 2004). A general concern with thin applicant pools for school leadership positions has also raised concerns that many ascending to top school

positions may not be ready to make strong moral decisions in the face of increasing pressures (Pardini, 2004; Stover, 2002). In a survey of chief state education officers, executive directors of American Association of School Administrators’ (AASA) state affiliates, and executive directors of the National School Boards Association’s (NSBA) state affiliates approximately 60% felt they were facing a leadership applicant pool crisis, over 84% felt the quality of the applicant was decreasing, and 75% of the respondents cited a need to improve pre-service graduate programs (Glass, 2001; Stover, 2002)

Long before NCLB the ethical behavior of school administrators was under fire as the 1990s brought a seemingly endless string of high profile stories detailing ethical charges against top school officials (Pardini, 2004). Stories of nepotism, embezzlement, and sex scandals led to an increased critique of the role of moral leadership in schools. The result was not only more attention from scholars in the field but also increased activity among policymakers and professional organizations to establish ethics standards. For example, in 1992 the state of New Jersey passed the School Ethics Act, which established the School Ethics Commission with the power to investigate ethical violations among school board members and school administrators, and to recommend disciplinary actions to the commissioner which range from formal sanctions to removal. The commission is responsible for oversight of a wide range of potential ethics violations but at the time was established to curb what was seen as rampant nepotism during the 1980s and early 1990s (Holster, 2004).

Attempts to Define Moral Leadership

Despite a spike in scholarly activity advocating for moral leadership and increased attention to ethics regulation, the body of research exploring the nature of moral leadership remains thin. From these studies researchers have found that for school district leaders: size of district and salary are positively correlated, and years of service negatively correlated, with more ethical responses to moral dilemmas. These same studies show that in general terms the ethical capacity of school leaders was not sufficient for the demands of the job (Pardini, 2004; Fenstermaker, 1996). Fenstermaker (1996) found that less than half (48.1%) of 2790 responses to borderline ethical dilemmas by 270 randomly selected superintendents that responded to the survey were scored as ethical. The growing evidence of ethical shortfalls within the profession in the mid-1990s led to a broad call from within and outside the field to address the moral decision making of school leaders. Both pre-service and in-service ethics education programs were prescribed to teach ethics to aspiring and sitting administrators (Pardini, 2004; Fenstermaker, 1996).

As those shaping policy and developing responses to the “moral crisis” in schools began their work it became clear that talking about morals in schools was still a controversial topic and there was not a clear definition of what moral leadership was, despite the charge to hire more of it and help those already hired to have it (Starratt, 1994). Research that claims moral leadership as a key indicator of student success often fails to define what moral leadership looks like, and when definitions are provided they vary greatly across schools and studies. In a review of moral leadership studies from 1979 to 2003, it has been concluded that a limitation of the studies of moral leadership within the past 20 years is that few scholars have defined clearly what they mean by moral leadership (William Greenfield, 2004).

For example, in a review of 12 high performing, high-poverty schools “moral leadership” was identified as instrumental to student and school success.

According to research by Bell (2001), schools identified several definitions of moral leadership including:

- Vision – what adults do in schools plays a major role in shaping children’s lives and preparing them for lifelong success.

- Respect/high expectations/ support/ hard work.

- Empowerment.

The different definitions of moral leadership are largely a result of the diverse context and needs of schools that successful leaders must address. However, this creates a difficult challenge for teachers of educational leadership attempting to develop curriculum and teaching methods that will serve new principals and superintendents best as they graduate and enter an unfamiliar context with needs and ethical pitfalls that may not be immediately known to them.

The Influence of Accreditation Standards

The call to invest in moral leadership training has come from scholars, policymakers, and professional organization in the field of educational administration. Graduate programs must prepare future leaders to be more aware of their ethical and moral responsibilities as well as being better equipped to execute them if they are to effectively steward the increasingly complex and high pressure school of the 21st century. School leaders are best able to positively influence school culture and success when well-established and significant

community values that support equity and social justice are connected with what Grogan and Andrews (2002) call “morally and ethically uplifting leadership.” According to Grogan and Andrews, graduate programs in educational leadership have been shown to have a significant effect on leadership capacity when programs have strong theory/research bases, provided authentic learning experiences, simulate the development of situated cognition, and foster real-life problem-solving skills.

National professional organizations and accreditation standards have played a major role in shaping the curriculum of school administration graduate programs. The first among major professional organizations to place an emphasis on moral school leadership was the National Policy Board for Educational Administration (NPBEA), who in 1994 created the Interstate School Leaders Licensure Consortium (ISLLC) with the goal of establishing universal professional standards that would guide the practice and preparation of school leaders (Murphy, 2005). Although, consortium leaders recognized that infusing new standards with values and ethical guidelines would be controversial they also acknowledged that behavior, policy, and practice was influenced by values and it was impossible to disentangle moral leadership and how schools functioned.

According to Murphy, this value-centered approach was reinforced by a belief among ISLLC founders that the effort to create a scientifically anchored, value- free profession resulted in an ethically truncated if not morally bankrupt profession.

Six years after the initial formation of ISLLC a working group was formed by the NPBEA to establish performance-based standards that would serve as the National Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Education’s (NCATE’s) review standards for educational leadership programs (National Policy Board for Educational Administration, 2002). This working group included representatives from the major professional organizations in the field including the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education, the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, the American Association of School Administrators, the National Association of Secondary School Principals, National Association of Elementary School Principals, the National Council of Professors of Educational Administration, the National Association of School Boards, and the (UCEA) University Council for Educational Administration (National Policy Board for Educational Administration, 2002). The result of this broad based and powerful coalition was a set of standards officially adopted by NCATE in 2002 that are the foundation of NCATE’s accreditation review process for educational leadership graduate programs. The NCATE standards were closely aligned with the ISLLC standards providing a single, unified set of

national standards guiding administrative practice for the preparation of principals, superintendents, curriculum directors, and supervisors (National Policy Board for Educational Administration, 2002).

The NCATE/ISLLC review process, that since 2002 has been the prevailing accreditation standard throughout the profession, has seven components. Standard number five refers specifically to ethics. It suggests that candidates who complete the program are educational leaders with knowledge and ability to promote the success of all students by acting with integrity, fairly, and in an ethical manner.

The NCATE narrative continues to describe the purpose and function of the ethics in the profession noting that the standard addresses the leader’s role as the “first citizen” of the school and/or district community. Educational leaders should set the tone for how employees and students interact with one another and with members of the school, district, and larger community. The leader’s contacts with students, parents, and employees must reflect concern for others as well as for the organization and the position. They must develop the ability to examine personal and professional values that reflect a code of ethics. Further, they must be able to serve as role models, accepting responsibility for using their position ethically and constructively on behalf of the school/district community. Finally, educational leaders must act as advocates for all children, even those with special needs who may be underserved.

- 5.1 – Acts with Integrity: Candidates demonstrate a respect for the rights of others with regard to confidentiality and dignity and engage in honest interactions.

- 5.2 – Acts Fairly: Candidates demonstrate the ability to combine impartiality, sensitivity to student diversity, and ethical considerations in their interactions with others.

- Candidates are required to develop a code of ethics using personal platforms, professional leadership association examples, and a variety of additional source documents focusing on ethics.

- Candidates are required to conduct a self-analysis of a transcript of a speech delivered to a community organization and look for examples of integrity, fairness, and ethical behavior.

- Candidates are required to lead a discussion around compliance issues for district, school, or professional association codes of ethics.

- Candidates are required to make a speech to a local service organization and articulate and demonstrate the importance of education in a democratic society.

- Candidates are required to survey constituents regarding their perceptions of his/her modeling the highest standards of conduct, ethical principles, and integrity in decision-making and behaviors.

We can expect that the merger of the ISLLC standards with the NCATE accreditation standards will bring about more interest in the design and assessment of moral leadership. It is, however, important to note that as the NCATE standards become more prescriptive there is a clear focus on producing documents that stem from reflection, but it is unclear how the practice of reflection, for example, is taught and reinforced as a fundamental practice for school leaders. The NCATE ethics standard is an important vehicle for promoting teaching ethics in graduate programs, but falls short of promoting the process of moral reasoning and it is there where the field is still searching for an understanding of what effective moral leadership training encompasses, and how to best deliver a comprehensive moral reasoning curriculum.

The Evolution of Ethics Education

The emergence of moral leadership as a topic of policy and a component of the accreditation standard has not been lost on graduate schools. Many graduate programs identified as exemplary in recent years place moral leadership at the core of their curriculum. In a 2002 study of exceptional and innovative programs in educational leadership, most of the exemplary programs were closely aligned with the ISLLC standards and almost all placed a particular emphasis on the ethics standard (Jackson & Kelley, 2002). For example, in summarizing the Miami University (Ohio) program emphasis, Cambron-McCabe and Foster (1994) stated that if educators are to accept school leadership as an intellectual and moral practice, they must understand their role in shaping the purposes of schooling for

a new era and how this cannot be detached from the broader social and political context.

Historically, however, examples like Miami University have been the exception not the rule when it comes to program emphasis on moral development. Attempts to study teaching ethics and moral decision making in pre-service school leadership programs have focused largely on moral leadership as an emerging field with an emphasis on explaining the growth of ethics as an interest in school leadership, curriculum, and instructional strategies. Two studies have attempted to survey UCEA schools to measure the approach to ethics in educational leadership preparation programs (Farquhar, 1981; Beck & Murphy, 1994). In the first study of its kind, Robin Farquhar (1981) surveyed 48 UCEA colleges and found that only four schools reported they had distinct program components intended to deliberately focus on ethics and additional found only two schools endeavored to consciously integrate ethics into what they teach. Murphy and Beck (1994) revisited the study of ethics in UCEA schools by surveying department chairs about their practice and perceptions of teaching leadership ethics. While only four out of 42 respondents reported that their department offered learning opportunities concerned with ethics “a great deal,” 21 schools responded to the same question “somewhat,” and only 7 schools reported little or no ethics based curriculum of any kind. The Beck and Murphy study found that those schools that were actively engaged in an ethics curriculum did so because of the practical necessity for administrators to effectively wrestle with moral dilemmas and an increasing theoretical basis for attention to moral leadership. Just over one-third of the responding schools offered courses in ethics showing a dramatic increase in attention to teaching moral leadership from the early 1980s to the early 1990s with an emphasis on the early 1990s as a burst of activity since many chairs reported these courses as new or under development at the time of the study.

- Written cases and dilemmas.

- Readings from outside education.

- Readings focusing on professional ethics.

- Readings discussing specific ethical principles or issues.

Beck and Murphy point out that a contributing factor to the diversity of course content and pedagogy is the myriad definitions of ethics not only in the field of

educational leadership, but in the literature as ethics is discussed cross- contextually. The lack of a unified definition of moral leadership and the wide range of thought about what moral leadership looks like and what it means for school success makes it difficult for research in the field to build on itself.

In other professional development fields (i.e., dentistry) the introduction of more strongly established operational definitions from moral psychology has provided a common language and facilitated growth in understanding profession-specific moral development by building on an existing body of research in professional ethics training in fields that have already adopted or applied moral psychology research (Bebeau, 2002; King & Mayhew, 2002). The lack of connection in the literature between the field of developmental moral psychology and educational leadership preparation is striking. For example, scholars such as Kohlberg and Rest are rarely cited in research that examines how prospective school leaders are taught and there have been few attempts to explore how moral psychology currently informs and may better inform the development of school administrators.

It is not clear whether the increased attention given to moral leadership education is more a result of accreditation standards, the public call for better moral leadership, or the presence of more scholarly articles on the subject. What is evident is that the overarching theme found in the literature has translated to practice in the majority of school leadership graduate programs. Moreover, the prescriptive elements of the NCATE standards have influenced the kinds of assignments and assessments most commonly used. In several cases school leadership programs have engaged their faculty in a thoughtful planning process to integrate the teaching of moral leadership into their curriculum and develop meaningful assessment strategies. Highlighting these exemplary programs will be a critical next step in sharing information among faculty about how to teach moral leadership and evaluate student work in this area. However, before this can be effectively done the field must begin to reach a shared understanding of how moral leadership is defined within programs and in the literature. It is on this point that the work already done in moral psychology as applied to other pre- professional training programs can be most helpful.

The Neo-Kohlbergian approach to moral development that gave birth to Rest’s four component model has shown great promise in identifying independent and measurable skills that make up the process of effective moral decision making. The field of moral psychology has shown us how these components can be

effectively taught and students can become better at identifying a moral problem, sifting through the myriad lines of action, making morally justified decisions about which line of action to choose, placing that choice in the context of often competing personal and professional values, and having the strength of conviction to persist and follow through with the moral choice. Adapting these efforts to the context of school leadership would help faculty develop stronger assessments as well as address teaching methods to bridge the gap that exists between moral motivation and implementation.

Over the last 25 years the field of educational administration has moved from formally introducing ethics into the education leadership curriculum to a widespread effort to emphasize moral leadership through myriad methods and theoretical frameworks. The next steps in this evolution are to critically examine how colleges of education teach moral decision making, ask the question “what works” and build a knowledge base that informs and improves pedagogy, curriculum, and assessment in the field of moral school leadership.

Bebeau, M. J., & Thomas, S. J. (1994). The impact of a dental ethics curriculum on moral reasoning. Journal of Dental Education, 58 (9) , 684-692.

Bebeau, M. J. (2002). The defining issues test and the four component model: Contributions to professional education. Journal of Moral Education, 31(3) , 271- 295.

Beck, L. G., & Murphy, J. (1994). Ethics in educational leadership programs: An expanding role . Thousand Oaks, California: Corwin Press.

Beck, L. G., & Murphy, J. (1997). Ethics in educational leadership programs: emerging models . Columbia, MO: The University Council for Educational Administration.

Bell, J. A. (2001). High-Performing, High-Poverty Schools. Leadership, 31(1) , 8- 11

Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (2002). Leading with soul and spirit. School Administrator, 2 .

Cambron-McCabe, N., & Foster, W. (1994). A paradigm shift: Implications for the Preparation of School Leaders. In Mulkee, T., Cambron-McCabe, N., & Anderson, B. Democratic Leadership: The Change Context of Administrative Preparation . New Jersey: Ablex Publishing.

Erwin, W. J. (2000). Supervisor moral sensitivity. Counselor Education & Supervision, 40(2) .

Farquhar, R. (1981). Preparing educational administrators for ethical practice. The Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 27(2) , 192-204.

Fenstermaker, W. C. (1986). The Ethical Dimension of Superintendent Decision Making. School Administrator .

Fullan, M. (2003). The moral imperative of school leadership . Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Corwin Press.

Glass, T. E. (2001). State education leaders view the superintendent applicant crisis . Education Commission of the States, September 2001.

Greenfield, W. (2004). Moral leadership in schools. Journal of Educational Administration, 42(2) , 174-196.

Grogan, M., & Andrews, R. (2002). Defining preparation and professional development for the future. Educational Administration Quarterly, 38(2) , 233- 256

Gross, M. L. (2001). Medical ethics education: To what Ends? Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 7(4) , 387-397.

Hodgkinson, C. (1991). Educational leadership: The moral art . Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press.

Holster, R. H. (2004). Building an ethical board. The School Administrator , September 2004.

Illingworth, S. (2005). Assessment within applied/professional ethics . Retrieved October 26, 2005, from http://www.prs- ltsn.leeds.ac.uk/ethics/documents/assessment.pdf

Jackson, B.L., & Kelley, C. (2002). Exceptional and innovative programs in educational leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 38(2) , 192-212.

Jaeger, S. M. (2001). Teaching Health care ethics: The importance of moral sensitivity for moral reasoning. Nursing Philosophy, 2 , 131-142.

King, P. M., & Mayhew, M. J. (2002). Moral judgment development in higher education: Insights from the defining issues test. Journal of Moral Education, 31(3) , 247-270.

Latif, D. A. (2000). The relationship between ethical dilemma discussion and moral development. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education .

Leithwood, K. (1996). Preparing school leaders: What works? Journal of School Leadership, 6 , 316-342.

Murphy, J. (1995). Rethinking the foundations of leadership preparation: Insights from school improvement efforts. DESIGN for Leadership: The Bulletin of the National Policy Board for Educational Administration, 6(1) .

Murphy, J. (2005). Unpacking the foundations of ISLLC standards and addressing Concerns in the Academic Community. Educational Administration Quarterly, 41(1), 154-191

National Policy Board for Educational Administration (2002). Standards for advanced programs in educational leadership for principals, superintendents, curriculum directors, and supervisors . Retrieved October 25, 2005, from http://www.npbea.org/ELCC/ELCCStandards%20_5-02.pdf

National Policy Board for Educational Administration (2002a). Instructions to implement standards for advanced programs in educational leadership for principals, superintendents, curriculum directors, and supervisors . Retrieved October 25, 2005, from http://www.npbea.org/ELCC/Instructions%20to%20ELCC%20Standards.102.pdf

Nucci, L. P. (2001). Education in the moral domain . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Pardini, P. (2004). Ethics in the superintendency. The School Administrator.

Sergiovanni, T. J. (1992). Moral leadership: Getting to the heart of school leadership . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1992.

Sizer, T. R., & Sizer, N. F. (1999). The students are watching: Schools and the moral contract . Boston, Mass.: Beacon Press.

Starratt, R. J. (1991). Building an ethical school: A theory for practice in educational leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly 27(2) , 185-202.

Starratt, R. J. (1994). Building an ethical school: A practical response to the moral crisis in schools . London: Falmer Press.

Stover, D. (2002). Looking for leaders: Urban districts find that the pool of qualified superintendents is shrinking. American School Board Journal .

December, 2002.

John Pijanowski is an assistant professor in the department of Educational Leadership at the University of Arkansas. Dr. Pijanowski graduated with a B.A. in Psychology from Brown University and a Ph.D. from Cornell University’s Department of Education. His research interests include moral reasoning in educational leadership and the study of effective school leadership instruction.

Advertisement

The role of leadership in educational innovation: a comparison of two mathematics departments’ initiation, implementation, and sustainment of active learning

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 24 November 2022

- Volume 2 , article number 258 , ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Rachel Funk 1 na1 ,

- Karina Uhing ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4165-4954 2 na1 ,

- Molly Williams ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7051-3018 3 na1 &

- Wendy M. Smith ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4848-4377 4

1672 Accesses

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Several studies have shown that the use of active learning strategies can help improve student success and persistence in STEM-related fields. Despite this, widespread adoption of active learning strategies is not yet a reality as institutional change can be difficult to enact. Accordingly, it is important to understand how departments in institutions of higher education can initiate and sustain meaningful change. We use interview data collected from two institutions to examine how leaders at two universities contributed to the initiation, implementation, and sustainability of active learning in undergraduate calculus and precalculus courses. At each institution, we spoke to 27 stakeholders involved in changes (including administrators, department chairs, course coordinators, instructors, and students). Our results show that the success of these changes rested on the ability of leaders to stimulate significant cultural shifts within the mathematics department. We use communities of transformation theory and the four-frame model of organization change in STEM departments in order to better understand how leaders enabled such cultural shifts. Our study highlights actions leaders may take to support efforts at improving education by normalizing the use of active learning strategies and provides potential reasons for the efficacy of such actions. These results underscore the importance of establishing flexible, distributed leadership models that attend to the cultural and operational norms of a department. Such results may inform leaders at other institutions looking to improve education in their STEM departments.

Similar content being viewed by others

What are the key elements of a positive learning environment? Perspectives from students and faculty

Integrating financial literacy into the k-12 curriculum: teachers’ and school leaders’ experience, the role of teachers in educational reform: a 20-year perspective.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

University leaders are increasingly concerned with student retention, graduation rates, and overall student success. Of particular concern are student experiences in STEM courses; research has shown that such experiences may negatively impact the persistence of students in both STEM and non-STEM majors. These issues are directly connected to students enrolled in mathematics courses (Ellis et al. 2016 ; Moreno and Muller 1999 ; PCAST 2012 ). In the United States, roughly 94% of enrollment in college mathematics courses (over two and a half million students per year) is in courses at the Calculus 2 level and below (Laursen 2019 ), and historically, it is not unusual for first-year mathematics courses to have DFW rates (grades of D, F or Withdraw) exceeding 30–40% (CRAFTY 2007 ). More recently, the Progress through Calculus Team surveyed over 200 PhD and masters granting mathematics departments in the United States about various features of their programs, and found that DFW rates were, on average, 27% for Precalculus courses, 22% for Calculus 1, and 20% for Calculus 2 (Apkarian and Kirin 2017 ). Therefore, focusing on improving student success in Precalculus to Calculus 2 (P2C2) has the potential to impact a large number of students.

Student-centered instructional practices, such as using active learning strategies, have emerged as a way to increase student success in STEM fields, addressing not only student learning, but also student attitudes, beliefs, motivation, and goals (e.g., Freeman et al. 2014 ; Theobald et al. 2020 ). Although much more is now known about effective instructional practices and campus structures to support student success, institutes of higher education are slow to change (Kezar 2014 ), and professors have not widely adopted such research-based practices (Smith et al. 2021 ; Stains et al. 2018 ; Tatto et al. 2018 ). In many countries, lecture is still viewed as the most effective pedagogical practice for collegiate instruction (e.g., Tatto et al. 2018 , 2020 ). Indeed, since such instruction typically proved effective for collegiate instructors themselves, it can be easy to assume lecture-based instruction should work for all students. Yet, this is not the case: lecture-based instruction can exacerbate opportunity gaps (Theobald et al. 2020 ). However, some professors are becoming more aware of the benefits of active learning and are making attempts to incorporate such strategies into courses (Laursen 2019 ). In a summary of the Progress through Calculus report, Rasmussen et al. ( 2019 ) highlight that 91% of mathematics departments consider active learning strategies to be very important or somewhat important in precalculus and calculus courses, yet only 15% reported that they are very successful in using such strategies. Similarly, in a survey of 722 physics professor across the United States, most reported that they were familiar with active learning strategies, yet the use of such strategies is frequently abandoned (Henderson and Dancy 2009 ). Professors shared numerous reasons for abandoning active learning strategies. Such reasons include not being able to see a difference in student learning gains, concerns about how much time such strategies take, having to teach a larger class, and having an unsupportive department. This suggests that professors need additional development and external support to permanently integrate such strategies into their instructional practices.

The process of changing one’s instructional practice from lecture-based to student-centered is complex; it requires more than just adopting a new technique such as think-pair-share. To support student learning, instructors need to use strategies that both provide opportunities for students to communicate their reasoning, and use this reasoning to develop ideas in class discussions (e.g., MAA 2018 ; Smith and Stein 2018 ; Speer and Wagner 2009 ). Speer and Wagner ( 2009 ) suggest that professors, even those with extensive teaching experience, may struggle to carry out student-centered techniques because they require specialized knowledge to enact; such knowledge differs from the knowledge used when enacting traditional teaching methods. Instructors who do not have the support to learn this type of knowledge may struggle to enact such strategies in ways that support student learning and conclude that such strategies are not an improvement. Without external support, such instructors are likely to revert to using traditional teaching methods. Beyond the challenges posed by learning new instructional practices, the use of student-centered instruction involves a parallel need to develop or select new instructional materials that align with these methods (e.g., syllabi, pacing guides, textbooks, assessments, etc.). Such changes are time-intensive, and in many departments such materials are shared. This means that individual change efforts do not exist in a vacuum; rather instructors often need the support and commitment of their department when making lasting changes to their instructional practice (Elrod and Kezar 2016 ).

Although some efforts to change instructional practices occur at an individual level, these initiatives often involve a community of individuals in a department who are all dedicated to change. Department members hoping to influence and transform shared instructional practice norms need to focus their efforts beyond the course level. These change efforts necessarily include a focus on classroom instruction; however, reforms that ignore the “political and institutional conditions required for long-lasting change” (Tobias 2000 p. 103) are unlikely to succeed or be sustained. Change initiatives need to address departmental and institutional barriers and have significant support at the department, campus, and community levels (Elrod and Kezar 2016 ). Lack of widespread support for such efforts will undermine them (Kezar 2014 ). Thus, it is important to study leadership decision-making and the leaders who are directing and supporting these efforts to understand how they make changes that span multiple levels.

Often, leadership decision-making related to these improvement efforts is seen as either “top-down” or “bottom-up,” signifying the origins and direction of decisions. Martin ( 2003 ) discussed how this either-or dichotomy often leads to misalignment of goals from both approaches. In the context of equity, he argues:

Rather than responding directly to the needs of marginalized students and centering discussions around what is best for these students, policy makers and mathematics educators have decided what (valued) mathematics should be learned, who should learn this mathematics, and for what purposes equity in mathematics is to be achieved. (p. 12)

He further suggests that top-down conceptualizations of equity led to interventions that were “out of alignment with the inequalities experienced by underrepresented students, parents, and communities” (Martin 2003 p.12). Since then, more research has come out to support the claims that top-down leadership is common (e.g., Henderson et al. 2011 ), and that there is a need for more “bottom-up” or grassroots leadership (e.g., Spillane and Diamond 2007 ). Kezar ( 2012 ) acknowledges that this dichotomy can be contradictory, but it also could be a hidden opportunity for strategic convergence between the two approaches, and the model of distributed or shared leadership is one common way this convergence can be achieved. Prysor and Henley ( 2018 ) studied higher education environments in the United Kingdom and similarly identified boundary-spanning across top-down and bottom-up efforts as necessary to launch and sustain institutional transformation efforts. To address the gaps between what research has shown to be effective practices and actual instructional practices in higher education, this study seeks to identify change mechanisms that allow institutions to implement and sustain active learning in first-year mathematics courses.

Background and context

This study involves two cases of large research universities in the United States that have incorporated active learning into their calculus sequence courses via a comprehensive approach to cultural and instructional change. We use Laursen and Rasmussen’s ( 2019 ) definition of inquiry-based mathematics education to form our definition of active learning: (1) students learn mathematics by engaging in challenging, cognitively demanding tasks; (2) students routinely communicate (orally and in writing) their own reasoning and engage with the reasoning of others; (3) instructors attend to and make use of student thinking to advance the mathematical agenda; and (4) instructors are explicitly attending to issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion. Although not explicitly labeled “active learning,” these principles are also embodied in the recommendations of the Mathematical Association of America’s recent Instructional Practices Guide ( 2018 ). It should be noted that in both cases, change efforts focused mostly on curriculum and uses of student thinking to implement active learning strategies, aligned with two of Laursen and Rasmussen’s pillars of inquiry-based mathematics education.

First- and second-year undergraduate courses in the United States typically include some form of precalculus level courses along with introductory level calculus courses. Calculus is typically broken up into a sequence of courses: Calculus 1 in the United States is typically understood to cover contents such as limits and derivatives, whereas Calculus 2 covers topics such as integration, sequences, and series. Almost all first-year college students in the United States take one of these courses depending on their level of preparation entering the university system. At large institutions, like the ones we studied, there are usually several sections of these courses made up of students from different areas of study (e.g., engineering, physics, chemistry, etc.). Many institutions choose to divide sections of a course up into “lecture” and “recitation” sessions. Lecture sessions typically consist of presenting new material to students, where recitation sessions are focused on reviewing content, practicing problems, and providing more individualized help. Depending on the institution, these courses are taught by a range of instructors including graduate students, part-time instructors, and full-time professors, who are collectively referred to as faculty in the United States. In our paper, we use the term “instructor” to refer to an individual person who teaches undergraduate courses, whereas the term “faculty” refers to a group of instructors. We use this terminology throughout this paper.

The reforms that we studied started with a focus on Calculus 1, then grew to encompass Calculus 2, Precalculus-level courses, and other multi-section courses. In this paper, we refer to these courses as P2C2 courses (Precalculus through Calculus 2). This case study focuses specifically on department-level changes and the decision-making process behind such changes. In both cases, leaders worked to develop a common vision for changes among key stakeholders, which is often viewed as the foundation of effective change (Elrod and Kezar 2016 ). Even though both institutions had upper administrators interested in promoting student success, the decision-making process did not resemble top-down change, but rather was distributed and shared across different people of power within the department (Kezar 2012 ). These cases are drawn from a larger set being developed by a collaborative National Science Foundation project: Student Engagement in Mathematics through an Institutional Network for Active Learning (SEMINAL; DUE-1624643, 1624610, 1624628, and 1624639). SEMINAL is studying how mathematics departments successfully incorporate active learning into their calculus sequence courses and how to guide other departments looking to institute similar reforms.

Research purpose and questions

The overarching goal of SEMINAL is to identify change mechanisms that allow institutions to implement and sustain active learning in first-year mathematics—Precalculus to Calculus 2 (P2C2)—courses. The project has two phases: Phase 1 involves six retroactive case studies of institutions that have reportedly succeeded in sustaining active learning, whereas Phase 2 consists of nine longitudinal case studies of institutions who are just beginning to reform instruction in their P2C2 sequence using the support of a networked improvement community (Martin and Gobstein 2015 ).

The SEMINAL project’s overall research question is What conditions, strategies, interventions, and actions at the departmental and classroom levels contribute to the initiation, implementation, and institutional sustainability of active learning in the undergraduate calculus sequence across varied institutions? Early work from this project has shown that leadership, in particular the commitment of formal leaders at departmental and institutional levels, is a critical driver in reform efforts (Smith et al. 2017 ). In this article, we focus on this key driver and compare how formal and informal leaders at two of SEMINAL’s Phase 1 institutions have impacted the initiation, implementation, and sustainability of improvement efforts in P2C2 courses. Thus, our research question is

How might leaders within a department impact the initiation, implementation, and sustainability of active learning in P2C2 courses?

Conceptual frameworks

To begin, we define leaders’ roles in the change process. We define “leader” broadly to include those individuals with formal or informal leadership roles who are in a position of power and/or have the respect of others at their institution. Leaders have either the authority to initiate change or the skills to motivate those with authority to do so. Hunter et al. ( 2007 ) approach leadership within a system framework that includes leaders, constituents, communication among constituencies, and contexts for those interactions. Often research on leadership includes language about subordinates; such roles and hierarchies are often less clear in education, particularly within academic departments in higher education (Hunter et al. 2007 ). Furthermore, leadership is not about “singular events….Rather, leadership is a process, a series of activities and exchanges engaged in over time and under varied circumstances” (Hunter et al. 2007 p. 440). Fullan ( 2006 ) claims that sustainable systems necessitate a specific type of leader: such leaders must be “system thinkers in action” (p. 114) capable of both working within the system and seeing the bird’s eye view of how their work connects to the larger context. Leadership, he argues, is key to sustainability efforts.

To address how leaders sustain, as well as initiate and implement change efforts, we draw on two frameworks: Kezar and Gehrke’s ( 2015 ) stages of development for communities of transformation and Reinholz and Apkarian’s ( 2018 ) four-frame model for cultural change in STEM departments. Rather than presenting a chronological timeline of changes at the two universities, we use Kezar and Gehrke’s stages of development (potential, coalescing, maturing, stewardship, and transformation) to organize our findings and describe the changes that occurred during the different stages of active learning reforms. At both universities, these changes also involved significant cultural shifts. In our analysis, we acknowledge that leaders exist within a cultural system and use the four frames (Reinholz and Apkarian 2018 ) to better understand the connections between leadership and four key components of culture: people, power, symbols, and structures. Exploring these connections also highlights the significance of our findings by helping us generalize how leaders might impact the initiation, implementation, and sustainability of active learning in P2C2 courses.

Conceptualizing the change process

Although calls for educational reforms are not new (e.g., Dewey 1902 ), sustained reforms resulting in student-centric teaching have been elusive (e.g., Kezar 2014 ; Lane et al. 2020 ; Laursen 2019 ; Reinholz et al. 2020 ; Stains et al. 2018 ). Although “bottom-up” approaches that begin with instructors have long been theorized as having more potential for sustainability and impact (e.g., Darling-Hammond 1990 ), reforms that do not also attempt to address cultural change and power dynamics over time tend to be short-lived (e.g., Kezar 2014 ). Effective leadership for education innovations is a promising approach (Spillane and Diamond 2007 ), but little research on higher education leadership in mathematics exists (Elrod 2020 ; Reinholz et al. 2020 ).

Kezar and Gehrke ( 2015 ) define a community of transformation as a “distributed community of individuals that uses a core philosophy to create and foster new practices that can be integrated into the various institutions in which individuals work” (p. 20). In our research, the individuals involved in the reform efforts within the mathematics department at each university operate in a similar way as a community of transformation due to their shared interest in establishing innovative instructional norms among their colleagues.

Although the communities we studied were not widely distributed nor spread across various institutions, they share many key characteristics with the communities of transformation that Kezar and Gehrke identify. Like communities of transformation, these communities provided ways for individual educators to learn how to effectively enact active learning strategies, while simultaneously working to shift the culture of their department. We also found that the development of these communities paralleled the lifecycle of communities of transformation described by Kezar and Gehrke ( 2015 ). Adapting the work of Wenger et al. ( 2002 ), Kezar and Gehrke ( 2015 ) present a framework for understanding the formation, design, and sustainment of a community of transformation. Kezar and Gehrke’s ( 2015 ) framework separates the lifecycle of a community of transformation into five stages: potential, coalescing, maturing, stewardship, and transformation. We summarize Kezar and Gehrke’s ( 2015 ) framework in Table 1 .

For the retroactive case studies reported in this article, we interviewed people about transformative efforts from the recent and more distant past. As such, some of the finer-grained distinctions between the potential and coalescing stages and between the maturing and stewardship stages were difficult to capture precisely. Kezar and Gehrke ( 2015 ) agree that both potential and coalescing and maturing and stewardship tend to overlap in ways that can make them indistinguishable. Thus, we group the potential and coalescing stages together to discuss how reform leaders initiated and implemented changes. We also group the maturing and stewardship stages together to discuss the sustainability of these changes.

To conceptualize sustainability, we reference Fullan ( 2005 ), who describes sustainability as “the capacity of a system to engage in the complexities of continuous improvement” (p. ix). An important characteristic of sustainable systems is that leaders are continuously working to improve the system. Whereas Kezar and Gehrke ( 2015 ) describe stewardship as “making the community sustainable over time” (p. 53), our conceptualization of sustainability includes both the maturing and stewardship stages as actions taken in these stages involve the continuous improvement to initial reforms. Furthermore, we note that the communities of transformation studied by Kezar and Gehrke ( 2015 ) were formed without an initial plan for sustainability.

Our communities, however, expanded reform efforts with the goal of making changes sustainable over time. Because of this difference, it is difficult for us to distinguish between actions taken in the maturing and stewardship stages. For example, leaders at one university created a coordinator position with the specific goal of making reform changes sustainable. Although this action helped their community mature by allowing them to bring in a new leader, they also did this explicitly to ensure the continuity of leadership in their calculus program.

In addition to combining the maturing and stewardship stages, we discuss how reform leaders have responded to challenges in the change process. We view this ability to respond to challenges as an essential part of sustaining reforms. However, we found little evidence that these communities have had to re-examine and change their original purpose. Therefore, we do not explicitly address the transformation stage in our findings.

Four-frame model for understanding departmental change

Departments and faculty are more likely to invest in course improvements when the campus and departmental culture supports instructional innovation (Kezar 2014 ). Bergquist and Pollack ( 2008 ) suggest culture is a lens through which faculty members understand their universities: “A culture provides a framework and guidelines that help to define the nature of reality—the lens through which its members interpret and assign value to the various events and products of this world” (Bergquist and Pawlak 2008 p. 7). Culture as a lens can be a useful framework, but to capture the dynamic aspects of departmental change, additional dimensions are necessary.

Bolman and Deal’s ( 2008 ) four-frame model for understanding organizations may be useful in characterizing changes at the departmental level. This model involves four frames: human resource, political, symbolic and structural. Each frame “is both powerful and coherent. Collectively they make it possible to reframe, looking at the same thing from multiple lenses or points of view…reframing is a powerful tool for gaining clarity, regaining balance, generating new options, and finding strategies that make a difference” (Bolman and Deal 2008 pp. 21–22). Although individuals tend to gravitate to a certain frame of thinking, “learning to apply all four [frames]” can deepen a leader’s understanding of their organization and help them make more informed decisions (Bolman and Deal p. 18). Reinholz and Apkarian ( 2018 ) have adapted this model for use in higher education contexts to capture the subtleties inherent in departmental change efforts. Their model relabels the four frames as people , power , symbols , and structures, each of which is integral in understanding departmental culture (see Table 2 for a description of each of these frames).

Researchers have used this four-frame model as an analytic tool to understand how STEM departments are able to enact systemic changes (e.g., Rämö et al. 2019 ; Reinholz and Apkarian 2018 ; Reinholz et al. 2019 ). Reinholz et al. ( 2019 ) found this framing useful in describing culture shifts within one science department over the course of 15 years. They found that whereas lasting shifts seemed to have occurred when viewing the department’s culture through the people, symbols, and power frames, without permanent structures in place the department’s initial educational improvement efforts (which were originally deemed a success) could not be sustained. This prompted a second, more targeted, change effort that explicitly developed sustainable structures to support change efforts. The authors contend that this second wave of change efforts built on initial efforts and made change efforts more sustainable.

In this paper, we use the four frames to interpret how cultural change supporting active learning was achieved in three stages of the change process: initiation, implementation and sustainability. In particular, the four-frame model provides us with a framework for understanding how leaders addressed these frames in their efforts to support the uptake of active learning within their departments.