An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Unemployment in the time of COVID-19: A research agenda ☆

David l. blustein.

a Boston College, United States of America

b University of Florida, United States of America

Joaquim A. Ferreira

c University of Coimbra, Portugal

Valerie Cohen-Scali

d Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers, France

Rachel Gali Cinamon

e University of Tel Aviv, Israel

Blake A. Allan

f Purdue University, United States of America

This essay represents the collective vision of a group of scholars in vocational psychology who have sought to develop a research agenda in response to the massive global unemployment crisis that has been evoked by the COVID-19 pandemic. The research agenda includes exploring how this unemployment crisis may differ from previous unemployment periods; examining the nature of the grief evoked by the parallel loss of work and loss of life; recognizing and addressing the privilege of scholars; examining the inequality that underlies the disproportionate impact of the crisis on poor and working class communities; developing a framework for evidence-based interventions for unemployed individuals; and examining the work-family interface and unemployment among youth.

This essay reflects the collective input from members of a community of vocational psychologists who share an interest in psychology of working theory and related social-justice oriented perspectives ( Blustein, 2019 ; Duffy, Blustein, Diemer, & Autin, 2016 ). Each author of this article has contributed a specific set of ideas, which individually and collectively reflect some promising directions for research about the rampant unemployment that sadly defines this COVID-19 crisis.

Our efforts cohere along several assumptions and values. First, we share a view that unemployment has devastating effects on the psychological, economic, and social well-being of individuals and communities ( Blustein, 2019 ). Second, we seek to build on the exemplary research on unemployment that has documented its impact on mental health ( Paul & Moser, 2009 ; Wanberg, 2012 ) and its equally pernicious impact on communities ( International Labor Organization, 2020b ). Third, we hope that this contribution charts a research agenda that will inform practice at individual and systemic levels to support and sustain people as they grapple with the daunting challenge of seeking work and recovering from the psychological and vocational fallout of this pandemic.

The advent of this period of global unemployment is connected causally and temporally to considerable loss of life and illness, which is creating an intense level of grief and trauma for many people. The first step in developing a research agenda for unemployment during the COVID-19 era is to describe the nature of this process of loss in so many critical sectors of life. A major research question, therefore, is to what extent does this unemployment crisis vary from previous bouts of unemployment which were linked to economic fluctuations? In addition, exploring the role of loss and trauma during this crisis should yield research findings that can inform psychological and vocational interventions as well as policy guidance to support people via civic institutions and communities.

1. Recognizing and channeling our own privilege

In Joe Pinker's (2020) Atlantic essay entitled, “ The Pandemic Will Cleave America in Two”, he highlights two distinct experiences of the pandemic. One is an experience felt by those with high levels of education in stable jobs where telework is possible. Lives are now more stressful, work has been turned upside down, childcare is challenging, and leaving the house feels ominous. The other is an experience felt by the rest of the working public – those who cannot work from home and thus are putting themselves at risk every day, whose jobs have been either lost or downsized, and who are wondering not only if they will catch the virus but whether they have the means and resources to survive. As psychologists and professors, the vast majority of “us” (those writing this essay and those reading it) are extremely fortunate to be in the first group. The pandemic has only served to exacerbate the extent of this privilege.

Given our relative position of power, what are ways we can change our research to be more meaningful and impactful to those outside of our bubble? We propose that the recent work on radical healing in communities of color – where the research is often done in collaboration with the participants and building participant agency is an explicit goal - can inform our path forward ( French et al., 2020 ; Mosley et al., 2020 ). Work has always been a domain where individuals experience distress and marginalization. However, in the current pandemic and into the unforeseeable future, this will only exponentially increase. Sure, we can do surveys about people's experiences and provide incentives for their time. And of course qualitative work will allow us to more directly connect with participants and hear their voices. But what is most needed is research where participants receive tangible benefits to improve their work lives. We, as privileged scholars, need to think about how we can use our expertise in studying work to infuse our studies with real world benefits. We see this as occurring on a spectrum in terms of scholars' time and resources available – from information sharing about resources to providing job-seeking or work-related interventions. In our view, now is the time to truly commit to using work-related research not just as a way to build scholarly knowledge, but as a way to improve lives.

2. Inequality and unemployment

Focusing research efforts on real-world benefits means acknowledging how the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed and exacerbated existing inequities in the labor market. Millions of workers in the U.S. have precarious jobs that are uncertain in the continuity and amount of work, do not pay a living wage, do not give workers power to advocate for their needs, or do not provide access to basic benefits ( Kalleberg, 2009 ). Power and privilege are major determinants of who is at risk for precarious work, with historically marginalized communities being disproportionately vulnerable to these job conditions ( International Labor Organization, 2020a ). In turn, people with precarious work experience chronic stress and uncertainty, putting them at risk for mental health, physical, and relational problems ( Blustein, 2019 ). These risk factors may further worsen the effects of the COVID-19 crisis while simultaneously exposing inequities that existed before the crises.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an opportunity for researchers to define and describe how precarious work creates physical, relational, behavioral, psychological, economic, and emotional vulnerabilities that worsen outcomes from crises like the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., unemployment, psychological distress). For example, longitudinal studies can examine how precarious work creates vulnerabilities in different domains, which in turn predict outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic, including unemployment and mental health. This may include larger scale cohort studies that examine how the COVID-19 crisis has created a generation of precarity among people undergoing the school-to-work transition. Researchers can also study how governmental and nonprofit interventions reduce vulnerability and buffer the relations between precarious work and various outcomes. For example, direct cash assistance is becoming increasingly popular as an efficient way to help people in poverty ( Evans & Popova, 2014 ). However, dominant social narratives (e.g., the myth of meritocracy, the American dream) blame people with poor quality work for their situations. Psychologists have a critical role in (a) documenting false social narratives, (b) studying interventions to provide accurate counter narratives (e.g., people who receive direct cash assistance do not spend money on alcohol or drugs; most people who need assistance are working; Evans & Popova, 2014 ), and (c) studying how to effectively change attitudes among the public to create support for effective interventions.

3. Work-family interface

Investigating the work-family interface during unemployment may appear contradictory. It can be argued that because there is no paid work, the work-family interface does not exist. But ‘work’ is an integral part of people's lives, even during unemployment; for example, working to find a job is a daunting task that is usually done from home. Thus, the work-family interface also exists during unemployment, but our knowledge about this is limited. Our current knowledge on the work-family interface primarily focuses on people who work full-time and usually among working parents with young children ( Cinamon, 2018 ). As such, focusing on the work-family interface during periods of unemployment represents a needed research agenda that can inform public policy and scholarship in work-family relationships.

The rise in unemployment due to COVID-19 relates not only to the unemployed, but also to other family members. Important research questions to consider are how are positive and negative feelings and thoughts about the absence of work conveyed and co-constructed by family members? What family behaviors and dynamics promote and serve as social capital for the unemployed and for the other members of the family? Do job search behaviors serve as a form of modeling for other family members? What are the experiences of unemployed spouses and children, and how do these experiences shape their own career development? These issues can be discerned among unemployed people of different ages, communities, and cultures.

Several research methods can promote this agenda. Participatory action research can enable vocational researchers to be proactive and involved in increasing social solidarity. This approach requires mutual collaboration between the researcher and families wherein one of the parents is unemployed. By giving them voice to describe their experiences, thoughts, ideas, and suggested solutions, we affirm inclusion of the individuals living through the new reality, thereby conveying respect and acknowledgment. At the same time, we can bring ideas, knowledge, and social connections to the families that can serve as social capital. In addition, longitudinal quantitative studies among unemployed families that explore some of the issues noted above would be important as a means of exploring how the new unemployment experience is shaping both work and relationships. We also advocate that meaningful incentives be offered to participants in all of these studies, such as online job search workshops and career education interventions for adolescents.

4. Strategies for dealing with unemployment in the pandemic of 2020

Forward-looking governments and organizations (such as universities) should begin thinking about how to deal with the immediate and long-term consequences of the economic crisis created by COVID-19, especially in the area of unemployment. Creating meaningful interventions to assist the newly unemployed will be difficult because of the unprecedented number of individuals and families that are affected and because of the diverse contextual and personal factors that characterize this new population. Because of this diversity of contextual and personal factors, different interventions will be required for different patterns of individual/contextual characteristics ( Ferreira et al., 2015 ).

In broad outline, a research program to address the diversity of issues identified above could be envisioned to consist of several distinct phases: First, it would be necessary to carefully assess the external circumstances of the unemployed individual's job loss, including the probability of re-employment, financial condition, family composition, and living conditions, among others. Second, an assessment should be made of the individual's strengths and growth edges, particularly as they impact the current situation. These assessments could be performed via paper or online questionnaire. Based on these initial assessments, the third phase would involve using statistical analyses such as cluster analysis to form distinct groups of unemployed individuals, perhaps based in part on the probability of re-employment following the pandemic. The fourth phase would focus on determining the types (and/or combinations) of intervention most appropriate for each group (e.g., temporary government assistance; emotional support counseling; retraining for better future job prospects; relocation, etc.). Because access to specific types of assistance is frequently a serious challenge, especially for underprivileged individuals, the fifth phase should emphasize facilitating individuals' access to the specific assistance they need. Finally, the sixth phase of research should evaluate the efficacy of this approach, although designing such a large research program in a crisis situation requires ongoing process evaluation throughout the design and implementation stages of the research program.

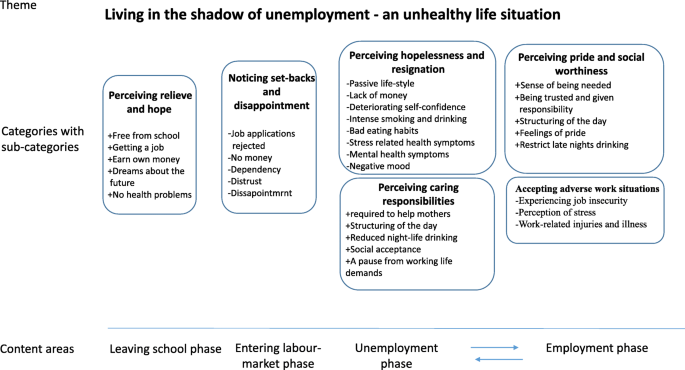

5. Unemployment among youth

As reflected in a recent International Labor Organization (2020a) report on the impact of the COVID-19 crisis, youth were already vulnerable within the workforce prior to the crisis; the recent advent of massive job losses and growing precarity of work is having particularly painful impacts on young people across the globe. The COVID-19 economic crisis with vast increases in unemployment (and competition between workers) and the probable growth of digitalization may result in a major dislocation of young workers from the labor market for some time ( International Labor Organization, 2020b ). To provide knowledge to meet this daunting challenge, researchers should develop an agenda focusing on two major components—the first is a participatory mode of understanding the experience of youth and the second is the development of evidence-based interventions that are derived from this research process.

The data gathering aspect of this research agenda optimally should focus on understanding unemployed youths' perception of their situation (opportunities, barriers, fears, and intentions) and of the new labor market. We propose that research is needed to unpack how youth are constructing this new reality, their relationship to society, to others, and to the world. This crisis may have changed their priorities, the meaning of work, and their lifestyle. For example, this crisis may have led to an awareness of the necessity of developing more environmentally responsible behaviors ( Cohen-Scali et al., 2018 ). These new life styles could result in skills development and increased autonomy and adaptability among young people. In addition, the focus on understanding youths' experience, which can encompass qualitative and quantitative methods, should also include explorations of shifts in youths' sense of identity and purpose, which may be dramatically affected by the crisis. The young people who are without work should be involved at each step of the research process in order to improve their capacities, knowledge, and agency and to ensure that the research is designed from their lived experiences.

Building on these research efforts, interventions may be designed that include individual counseling strategies as well as systemic interventions based on analyses of the communities in which young people are involved (for example, families and couples and not only individuals). In addition, we need more research to learn about the process of collective empowerment and critical consciousness development, which can inform youths' advocacy efforts and serve as a buffer in their career development ( Blustein, 2019 ).

6. Conclusion

The research ideas presented in this contribution have been offered as a means of stimulating needed scholarship, program development, and advocacy efforts. Naturally, these ideas are not intended to be exhaustive. We hope that readers will find ideas and perspectives in our essay that may stimulate a broad-based research agenda for our field, optimally informing transformative interventions and needed policy interventions for individuals and communities suffering from the loss of work (and loss of loved ones in this pandemic). A common thread in our essay is the recommendation that research efforts be constructed from the lived experiences of the individuals who are now out of work. As we have noted here, their experiences may not be similar to other periods of extensive unemployment, which argues strongly for experience-near, participatory research. We are also advocating for the use of rigorous quantitative methods to develop new understanding of the nature of unemployment during this period and to develop and assess interventions. In addition, we would like to advocate that the collective scholarly efforts of our community include incentives and outcomes that support unemployed individuals. For example, online workshops and resources can be shared with participants and other communities as a way of not just dignifying their participation, but of also providing tangible support during a crisis.

In closing, we are humbled by the stories that we hear from our communities about the job loss of this pandemic period. Our authorship team shares a deep commitment to research that matters; in this context, we believe that our work now matters more than we can imagine.

☆ The order of authorship for authors two through six was determined randomly; each of these authors contributed equally to this paper.

- Blustein D.L. Oxford University Press; NY: 2019. The importance of work in an age of uncertainty: The eroding work experience in America. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cinamon R.G. Paper presented at the Society of Vocational Psychology; Arizona: 2018, June. Life span and time perspective of the work-family interface – Critical transitions and suggested interventions. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen-Scali V., Pouyaud J., Podgorny M., Drabik-Podgorna V., Aisenson G., Bernaud J.L., Moumoula I.A., Guichard J., editors. Interventions in career design and education. Springer; Cham, Switzerland: 2018. [ Google Scholar ]

- Duffy R.D., Blustein D.L., Diemer M.A., Autin K.L. The psychology of working theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2016; 63 (2):127–148. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Evans D.K., Popova A. Cash transfers and temptation goods: A review of global evidence. The World Bank. 2014 doi: 10.1596/1813-9450-6886. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ferreira J.A., Reitzle M., Lee B., Freitas R.A., Santos E.R., Alcoforado L., Vondracek F.W. Configurations of unemployment, reemployment, and psychological well-being: A longitudinal study of unemployed individuals in Portugal. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2015; 91 :54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2015.09.004. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- French B.H., Lewis J.A., Mosley D.V., Adames H.Y., Chavez-Dueñas N.Y., Chen G.A., Neville H.A. Toward a psychological framework of radical healing in communities of color. The Counseling Psychologist. 2020; 48 :14–46. doi: 10.1177/0011000019843506. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- International Labor Organization World Employment and Social Outlook – Trends. 2020:2020. https://www.ilo.org/global/research/global-reports/weso/2020/lang--en/index.htm [ Google Scholar ]

- International Labor Organization. (2020b). Young workers will be hit hard by COVID-19's economic fallout. https://iloblog.org/2020/04/15/young-workers-will-be-hit-hard-by-covid-19s-economic-fallout/ .

- Kalleberg A.L. Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition. American Sociological Review. 2009; 74 (1):1–22. doi: 10.1177/000312240907400101. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mosley D.V., Hargons C.N., Meiller C., Angyal B., Wheeler P., Davis C., Stevens-Watkins D. Critical consciousness of anti-Black racism: A practical model to prevent and resist racial trauma. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2020 doi: 10.1037/cou0000430. (Advance online publication) [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Paul K.I., Moser K. Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2009; 74 :264–282. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pinker J. The Atlantic; 2020. The pandemic will cleave America in two. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wanberg C.R. The individual experience of unemployment. Annual Review of Psychology. 2012; 63 :369–396. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

A Crisis of Long-Term Unemployment Is Looming in the U.S.

- Ofer Sharone

How biases trap qualified job seekers in a cycle of rejection — and how to help them break free.

The stigma of long-term unemployment can be profound and long-lasting. As the United States eases out of the Covid-19 pandemic, it needs better approaches to LTU compared to the Great Recession. But research shows that stubborn biases among hiring managers can make the lived experiences of jobseekers distressing, leading to a vicious cycle of diminished emotional well-being that can make it all but impossible to land a role. Instead of sticking with the standard ways of helping the LTU, however, a pilot program that uses a wider, sociologically-oriented lens can help jobseekers understand that their inability to land a gig isn’t their fault. This can help people go easier on themselves which, ultimately, can make it more likely that they’ll find a new position.

Covid-19 has ravaged employment in the United States, from temporary furloughs to outright layoffs. Currently, over 4 million Americans have been out of work for six months or more , including an estimated 1.5 million workers in white-collar occupations, according to my calculations. Though the overall unemployment rate is down from its peak last spring, the percent of the unemployed who are long-term unemployed (LTU) keeps increasing and is currently at over 40%, a level of LTU comparable to the Great Recession but otherwise unseen in the U.S. in over 60 years.

- Ofer Sharone is an expert on long-term unemployment and the author of the book Flawed System/Flawed Self: Job Searching and Unemployment Experiences (University of Chicago Press). Sharone received his PhD in sociology from the University of California Berkeley, his JD from Harvard Law School, and is currently an associate professor of sociology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Partner Center

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Unemployment

After dropping in 2020, teen summer employment may be poised to continue its slow comeback.

Last summer, businesses trying to come back from the COVID-19 pandemic hired nearly a million more teens than in the summer of 2020.

Most in the U.S. say young adults today face more challenges than their parents’ generation in some key areas

About seven-in-ten say young adults today have a harder time when it comes to saving for the future, paying for college and buying a home.

Some gender disparities widened in the U.S. workforce during the pandemic

Among adults 25 and older who have no education beyond high school, more women have left the labor force than men.

Immigrants in U.S. experienced higher unemployment in the pandemic but have closed the gap

With the economic recovery gaining momentum, unemployment among immigrants is about equal with that of U.S.-born workers.

During the pandemic, teen summer employment hit its lowest point since the Great Recession

Fewer than a third (30.8%) of U.S. teens had a paying job last summer. In 2019, 35.8% of teens worked over the summer.

College graduates in the year of COVID-19 experienced a drop in employment, labor force participation

The challenges of a COVID-19 economy are clear for 2020 college graduates, who have experienced downturns in employment and labor force participation.

U.S. labor market inches back from the COVID-19 shock, but recovery is far from complete

Here’s how the COVID-19 recession is affecting labor force participation and unemployment among American workers a year after its onset.

Long-term unemployment has risen sharply in U.S. amid the pandemic, especially among Asian Americans

About four-in-ten unemployed workers had been out of work for more than six months in February 2021, about double the share in February 2020.

A Year Into the Pandemic, Long-Term Financial Impact Weighs Heavily on Many Americans

About a year since the coronavirus recession began, there are some signs of improvement in the U.S. labor market, and Americans are feeling somewhat better about their personal finances than they were early in the pandemic.

Unemployed Americans are feeling the emotional strain of job loss; most have considered changing occupations

About half of U.S. adults who are currently unemployed and are looking for a job are pessimistic about their prospects for future employment.

REFINE YOUR SELECTION

Research teams.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

The Pandemic's Impact on Unemployment and Labor Force Participation Trends

Following early 2020 responses to the pandemic, labor force participation declined dramatically and has remained below its 2019 level, whereas the unemployment rate recovered briskly. We estimate the trend of labor force participation and unemployment and find a substantial impact of the pandemic on estimates of trend. It turns out that levels of labor force participation and unemployment in 2021 were approaching their estimated trends. A return to 2019 levels would then represent a tight labor market, especially relative to long-run demographic trends that suggest further declines in the participation rate.

At the end of 2019, the labor market was hotter than it had been in years. Unemployment was at a historic low, and participation in the labor market was finally increasing after a prolonged decline. That tight labor market came to an abrupt halt with the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020.

Now, two years later, the labor market has mostly recovered from the depths of the pandemic recession. The unemployment rate is close to pre-pandemic lows, and job openings are at record highs. Yet, participation and employment rates have remained persistently below pre-pandemic levels. This suggests the possibility that the pandemic has permanently reduced participation in the economy and that current participation rates reflect a new normal. In this article, we explore how the pandemic has affected labor markets and whether a new normal is emerging.

What Is "Normal"?

One way to define the normal level of a variable is to estimate its trend and compare the observed data with the estimated trend values. Constructing a trend essentially means drawing a smooth line through the variations in the actual data.

But this means that constructing the trend for a point in time typically involves considering what happened both before and after that point in time. Thus, constructing the trend at the end of a sample is especially hard, since we do not yet know how the data will evolve.

We construct trends for three aggregate labor market ratios — the labor force participation (LFP) rate, the unemployment rate and the employment-population ratio (EPOP) — using methods described in our 2019 article " Projecting Unemployment and Demographic Trends ."

First, we estimate statistical models for LFP and unemployment rates of demographic groups defined by age, gender and education. For each gender and education, we decompose its unemployment and LFP into cyclical components common to all age groups and smooth local trends for age and cohort effects.

Second, we aggregate trends from the estimates of the group-specific trends. Specifically, we construct the trend for the aggregate LFP rate as the population-share-weighted sum of the corresponding estimated trends for demographic groups. We construct the aggregate unemployment rate and EPOP trends from the group-specific LFP and unemployment trends and the groups' population shares.

In our previous work, we estimated the trends for the unemployment rate and LFP rate of a gender-education group separately using maximum likelihood methods. The estimates reported in this article are based on the joint estimation of LFP and unemployment rate trends using Bayesian methods.

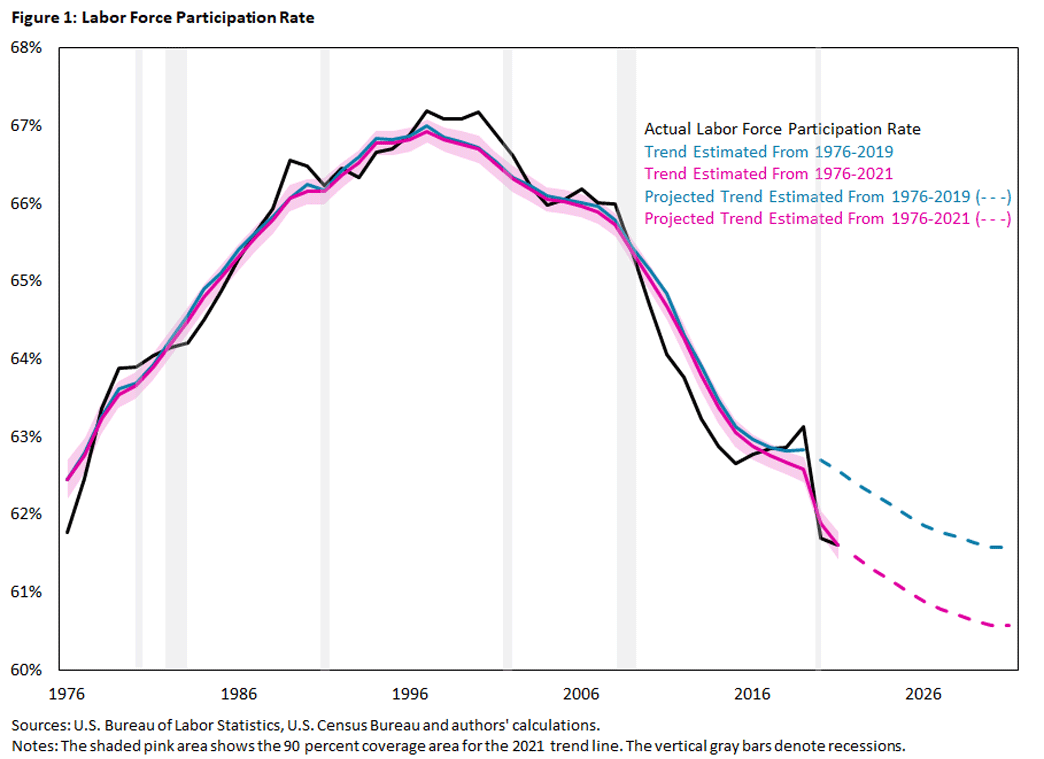

We separately estimate the trends using data from 1976 to 2019 (pre-pandemic) and from 1976 to 2021 (including the pandemic period). Figures 1, 2 and 3 display annual averages for the three aggregate labor market ratios — the LFP rate, the unemployment rate and EPOP, respectively — from 1976 to 2021.

In each figure, the solid black line denotes the observed values, and the blue and pink lines denote the estimated trend using data from 1976 up to and including 2019 and 2021, respectively. The estimated trends are subject to uncertainty, and the plotted trends represent the median estimate of the trend.

For the estimates based on data up to 2021, we also include the 90 percent coverage area shown as the shaded pink area. According to the statistical model, there is a 90 percent probability that the trend is contained in the coverage area. The blue and pink dotted lines represent our projections on how the labor market ratios will evolve until 2031, again based on the estimated trend up to and including 2019 and 2021. The shaded gray vertical areas highlight recessions as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

Pre-Pandemic Trends: 1976-2019

We start with the pre-pandemic trends for the LFP rate and unemployment rate estimated for data from 1976 through 2019. After a long recovery from the 2007-09 recession, the LFP rate was 63.1 percent in 2019 (slightly above the estimated trend value of 62.8 percent), and the unemployment rate was 3.7 percent (noticeably below its estimated trend value of 4.7 percent).

The LFP rate being above trend and the unemployment rate being below trend reflects the characterization of the 2019 labor market as "hot." But note that even though the LFP rate exceeded its trend value in 2019, it was still lower than during the 2007-09 period. This difference is accounted for by the declining trend in the LFP rate.

As noted in our 2019 article , LFP rates and unemployment rates differ systematically across demographic groups. Participation rates tend to be higher for younger, more-educated workers and for men. Unemployment rates tend to be lower for men and for the older and more-educated population.

Thus, changes in the population composition over time — that is, the relative size of demographic groups — will affect the aggregate LFP and unemployment rates, in addition to changes in the LFP and unemployment rate trends of the demographic groups.

As also noted in our 2019 article, the hump-shaped trend of the aggregate LFP rate reflects a variety of forces:

- Prior to 1990, the aggregate LFP rate was boosted by an upward trend in the LFP rate of women. But after 1990, the LFP rate of women began declining. Combining this with declining trend LFP rates for other demographic groups has reduced the aggregate LFP rate.

- Changes in the age distribution had a limited impact prior to 2005, but the aging population since then has lowered the aggregate LFP rate substantially.

- Increasing educational attainment has contributed positively to aggregate LFP throughout the period.

The steady decline of the unemployment rate trend reflects mostly the contributions from an older and more-educated population and, to some extent, a decline in the trend unemployment rates of demographic groups.

Pre-Pandemic Expectations of Future LFP and Unemployment Trends

Our statistical model of smooth local trends for the LFP and unemployment rates of demographic groups has the property that the best forecast for future trend values of demographic groups is their last estimated trend value. Thus, the model will only predict a change in the trend of aggregate ratios if the population shares of its constituent groups are changing.

We combine the U.S. Census Bureau population forecasts for the gender-age groups with an estimated statistical model of education shares for gender-age groups to forecast population shares of our demographic groups from 2020 to 2031 (the dotted blue lines in Figures 1 and 2).

As we can see, the changing demographics alone imply further reductions of 1 percentage point and 0.2 percentage points in the trend LFP rate and unemployment rate, respectively. This projection is driven by the forecasted aging of the population, which is only partially offset by the forecasted higher educational attainment.

Based on data up to 2019, the same aggregate LFP rates in 2021 as in 2019 would have represented a substantial cyclical deviation upward from the pre-pandemic trends.

It is notable that the unemployment rate is much more volatile relative to its trend than the LFP rate is. In other words, cyclical deviations from trend are much more pronounced for the unemployment rate than for the LFP rate.

In fact, in our estimation, the behavior of the unemployment rate determines the common cyclical component of both the unemployment rate and the LFP rate. Whereas the unemployment rate spikes in recessions, the LFP rate response is more muted and tends to lag recessions. This feature will be important for interpreting how the estimated trend LFP rate changed with the pandemic.

Finally, Figure 3 combines the information from the LFP rate and unemployment rate and plots actual and trend rates for EPOP. On the one hand, given the relatively small trend decline of the unemployment rate, the trend for EPOP mainly reflects the trend for the LFP rate and inherits its hump-shaped path and the projected decline over the next 10 years. On the other hand, EPOP inherits the volatility from the unemployment rate. In 2019, EPOP is notably above trend, by about 1 percentage point.

Unemployment and Labor Force Participation During the Pandemic

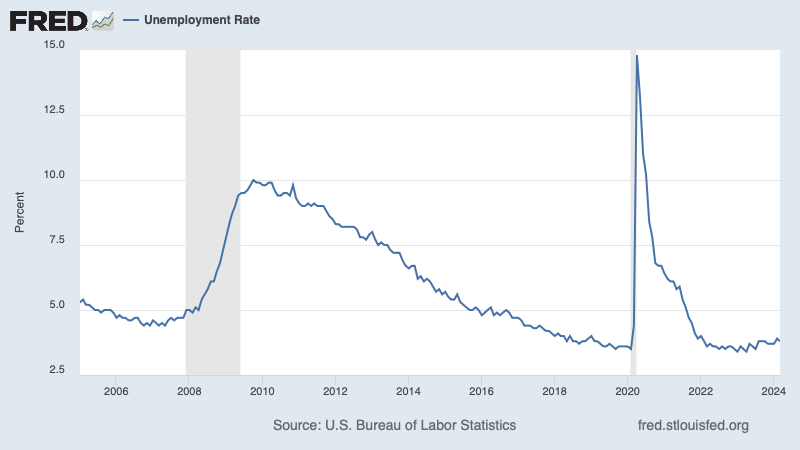

The behavior of unemployment resulting from the pandemic-induced recession was different from past recessions:

- The entire increase in unemployment between February and April 2020 was accounted for by the increase in unemployment from temporary layoffs. This differed from previous recessions, when a spike in permanent layoffs led the bulge of unemployment in the trough.

- The recovery started in May 2020, and the speed of recovery was also much faster than in previous recessions. After only seven months, unemployment declined by 8 percentage points.

- The behavior of the unemployment rate is reflected in the 2020 recession being the shortest NBER recession on record: It lasted for two months (March to April 2020).

To summarize, the runup and decline of the unemployment rate during the pandemic were unusually rapid, but the qualitative features were not that different from previous recessions after properly accounting for temporary layoffs, as noted in the 2020 working paper " The Unemployed With Jobs and Without Jobs . "

The decline in the LFP rate was sharp and persistent. The LFP rate dropped from 63.4 percent in February 2020 to 60.2 percent in April 2020, an unprecedented drop during such a short period of time. After a rebound to 61.7 percent in August 2020, the LFP rate essentially moved sideways and remained below 62 percent until the end of 2021.

The large drop in the aggregate LFP rate has been attributed to, among others:

- More people — especially women — leaving the labor force to care for children because of school closings or to care for relatives at increased health risk, as noted in the 2021 work " Assessing Five Statements About the Economic Impact of COVID-19 on Women (PDF) " and the 2021 article " Caregiving for Children and Parental Labor Force Participation During the Pandemic "

- An increase in retirement due to health concerns, as noted in the 2021 working paper " How Has COVID-19 Affected the Labor Force Participation of Older Workers? "

- Generous pandemic income transfers and unemployment insurance programs, as noted in the 2021 article " COVID Transfers Dampening Employment Growth, but Not Necessarily a Bad Thing "

All of these factors might impact the participation trend, but by how much?

The Pandemic's Effect on Trend Estimates for LFP and Unemployment

The aggregate trend assessment for the LFP and unemployment rates has changed considerably as a result of 2020 and 2021. Repeating the estimation of trend and cycle for our demographic groups using data from 1976 up to 2021 yields the pink trend lines in Figures 1 and 2.

The updated trend estimates now put the positive cyclical gap in 2019 for LFP at 0.5 percentage points (rather than 0.3 percentage points) and the negative cyclical gap for the unemployment rate at 1.4 percentage points (rather than 1 percentage point). That is, by this estimate of the trend, the labor market in 2019 was even hotter than by the estimates from the 1976-2019 period.

In 2021, the actual LFP rate is essentially at trend, and the unemployment rate is only slightly above trend. That is, by this estimate of the trend, the labor market is relatively tight.

Notice that even though the new 2021 trend estimates for both the LFP and the unemployment rates differ noticeably from the trend values predicted for 2021 based on data up to 2019, the trend revisions for the LFP rate are limited to more recent years, whereas the trend revisions for the unemployment rate apply to the whole sample.

The difference in revisions is related to how confident we can be about the estimated trends. The 90 percent coverage area is quite narrow for the LFP rate for the entire sample up to the last four years. Thus, there is no need to drastically revise the estimated trend prior to 2017.

On the other hand, the 90 percent coverage area for the trend unemployment rate is quite broad throughout the sample. That is, a wide range of values for trend unemployment is potentially consistent with observed unemployment values. Consequently, the last two observations lead to a wholesale reassessment of the level of the trend unemployment rate.

Another way to frame the 2020-21 trend revisions is as follows. The unemployment rate is very cyclical, deviations from trend are large, and though the sharp increase and decline of the unemployment rate in 2020-21 is unusual, an upward level shift of the trend unemployment rate best reflects the additional pandemic data.

The LFP rate, however, is usually not very cyclical, and it is only weakly related to the unemployment rate. Since the model assumes that the cyclical response does not change over the sample, it then attributes the large 2020-21 drop of the LFP rate to a decline in its trend and ultimately to a decline of the trend LFP rates of most demographic groups.

Finally, the EPOP trend is again mainly determined by the LFP trend, seen in Figure 3. Including the pandemic years noticeably lowers the estimated trend for the years from 2017 onwards. The cyclical gap in 2019 is now estimated to be 1.4 percentage points, and 2021 EPOP is close to its estimated trend.

What Does the Future Hold?

In our framework, current estimates of trend LFP and the unemployment rate for demographic groups are the best forecasts of future rates. Combined with projected demographic changes, this implies a continued noticeable downward trend for the LFP rate and a slight downward trend for the unemployment rate.

The trend unemployment rate is low, independent of how we estimate the trend. But given the highly unusual circumstances of the pandemic, the model may well overstate the decline in the trend LFP rate. Therefore, it is likely that the "true" trend lies somewhere between the trends estimated using data up to 2019 and data up to 2021.

That being a possibility, it remains that labor markets as of now have been unusually tight by most other measures, such as nominal wage growth and posted job openings relative to hires. This suggests that the true trend is closer to the revised 2021 trend than to the 2019 trend. In other words, the LFP rate and unemployment rate at the end of 2021 relative to the 2021 estimate of trend LFP and unemployment rate are consistent with a tight labor market.

Andreas Hornstein is a senior advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. Marianna Kudlyak is a research advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Hornstein, Andreas; and Kudlyak, Marianna. (April 2022) "The Pandemic's Impact on Unemployment and Labor Force Participation Trends." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief , No. 22-12.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

V iews expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Subscribe to Economic Brief

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.

Thank you for signing up!

As a new subscriber, you will need to confirm your request to receive email notifications from the Richmond Fed. Please click the confirm subscription link in the email to activate your request.

If you do not receive a confirmation email, check your junk or spam folder as the email may have been diverted.

Phone Icon Contact Us

Page One Economics ®

Exploring the dynamics of unemployment.

"Unemployment is of vital importance, particularly to the unemployed."

—Edward Heath

Introduction

Think of some reasons people become unemployed. Did you think of someone quitting, getting fired, or being laid off? Well, all of those reasons are correct; and, if the people who experience any of those events actively seek new work, they're considered unemployed and part of the labor market. But it's not just those who quit, are fired, or are laid off who enter the labor market. Some enter the market for the first time, and some get back into it after being out for some time.

This article provides Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Consumer Population Survey (CPS) data on when people

- enter the labor market for the first time (new entrants),

- return to the market after being out for a while (re-entrants),

- choose to quit for a different job (job leavers), and

- lose their job and decide to find another one (job losers).

Each dataset provides information about labor market and economic conditions. We'll explore these unemployed groups and how they may behave differently over time and during recessions, which are typically associated with an increase in the overall unemployment rate.

Unemployment and the Business Cycle

Let's start with some basics. Economists and agencies such as the BLS define unemployment as a condition where people at least 16 years of age are without jobs and actively seeking work. Notice there are two conditions (besides age): The person is (1) without work and (2) looking for work.

Figure 1 Unemployment Rate

SOURCE: US Bureau of Labor Statistics via FRED ® , Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1jVuT .

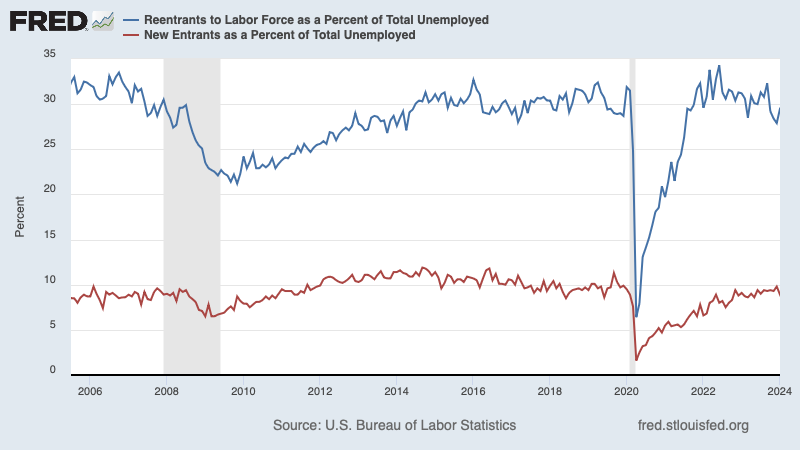

Figure 1 shows the unemployment rate between 2005 and 2024. Each shaded area of the graph represents a recession (a contractionary phase of the business cycle ). 1 Note that the overall unemployment rate tends to be sensitive to business cycles. When the economy is contracting, such as during the Great Recession of 2008-09, fewer people are employed (an increase in the unemployment rate). Economists associate cyclical unemployment with recessions in the business cycle. When the economy is expanding, more people are employed (a decrease in the unemployment rate). Economists associate frictional unemployment with these times; unemployed people tend to be either new entrants to the labor market (such as recent graduates) or re-entrants (returning to the labor market after being out for a while).

The graph shows the unemployment rate overall, but the number of new entrants, re-entrants, job leavers, and job losers changes depending on economic conditions; how much they change tells us how sensitive each group is to the business cycle—cyclical sensitivity.

Entering the Labor Market

Everyone's journey through the labor market starts somewhere. More specifically, it starts with your first job. New entrants have never worked before and are entering the labor force for the first time. 2 They are mainly students transitioning from education to employment. When new entrants begin their job search, they don't have a job (yet) but are officially looking for work, so they count as unemployed (frictionally unemployed). New entrants make up around 10% of the total unemployed.

However, new job seekers aren't the only ones jumping into the labor market; re-entrants previously worked but were out of the labor force before searching for another job. Re-entering the labor market is a personal and economic decision.

Re-entrants and New Entrants as a Percent of Total Unemployed

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics via FRED ® , Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1jVvt .

Re-entrant unemployment is cyclically sensitive (Figure 2, blue line). 3 When compared with new entrants (red line), re-entrants make up a more significant percentage of the total unemployed, 4 particularly when there is economic expansion. As the economy expands, the percentage of re-entrants slowly increases because there is increased confidence the labor market is more favorable for job seekers. Conversely, as the economy contracts (such as during the 2008-09 and 2020 recessions), the proportion of re-entrants decreases significantly because they end their job searches, leaving the labor market.

Leaving the Labor Market Voluntarily

Job leavers voluntarily quit their job and look for new work. 5 We also call these instances voluntary separations or voluntary layoffs. Job leavers can provide information about how people feel about the labor market's strength. For example, in the post-pandemic recovery of 2021-23, factors like re-evaluation of work-life balance and a tight labor market led to an increased number of job leavers, as they were seeking higher-paying jobs or new opportunities. So, an increase in the number of job leavers can indicate a healthy labor market: It shows that workers are confident about their chances of finding a new job and that they'll voluntarily leave their current job.

Job Leavers as a Percent of Total Unemployed

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics via FRED ® , Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1jVvY .

Figure 3 shows job leavers as a percent of the total unemployed from 2005 to January 2024. During recessions, such as the Great Recession of 2008-09, the percentage of job leavers declines, as fewer people leave their jobs due to uncertainty about finding new ones; this is driven by decreased business investment and demand for hires. Conversely, in economic expansions, more job leavers emerge as confidence grows, businesses invest more, and hiring increases. For example, as the economy recovered after the Great Recession (expansionary phase), the percentage of job leavers climbed upward and started to exceed pre-recession levels until the 2020 pandemic. 6 In September 2022, the percentage of job leavers peaked at 16%, and in October 2023 it returned to a pre-pandemic level of 12.3%, indicating the conclusion of what was headlined the "Great Resignation" or "Great Reshuffle." 7 The percentage of unemployed job leavers is still relatively small, and the percentage change among this group is the smallest throughout business cycles, indicating minimal cyclical sensitivity.

Leaving the Labor Market In voluntarily

Job losers are either temporarily laid off from a job but expect to be recalled or permanently laid off or fired from a job and begin looking for new work. We also call these instances involuntary separations or involuntary layoffs. Job losers have been particularly interesting to analyze because they make up the largest single group of the unemployed. 8

Job Losers as a Percent of Total Unemployed

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics via FRED ® , Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1jVwg .

Figure 4 shows job losers as a percent of the total unemployed from October 2005 to January 2024. The recessions in 2008-09 and 2020 show that the change in the percentage of job losers was reactive to each economic downturn. During the Great Recession it increased; after the recession ended in June 2009 the labor market recovery was slow, with the percentage of job losers ultimately returning to pre-recession levels in March 2015. 9 With a substantial period of economic expansion in the following years, the percentage of job losers decreased.

Each recession affects some industries more than others. During the 2020 recession, workers in the leisure and hospitality industry were the hardest hit. 10 This is an example of why job losers are the most cyclically sensitive of the four unemployed groups: As much as 70% of total business costs are employees. 11 During recessions, when businesses are dealing with decreased revenues, they look to cut their numbers of employees, investing less in labor.

Why does this information matter? Maybe you have been part of one of these unemployed groups or know someone who experienced unemployment, either voluntarily or involuntarily. When people experience unemployment, there is a reaction among each group, and how each group reacts plays a role in defining what the labor market looks and feels like for the unemployed, employed, and businesses. How cyclically sensitive each group is can also provide valuable insights for policymakers to make the best decisions for the economy and for businesses to recover after a downturn or continue to grow at a healthy rate.

1 The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Business Cycle Dating Committee maintains a chronology of U.S. business cycles, which identifies the dates of peaks and troughs that frame economic recessions and expansions. A recession is the period between a peak of economic activity and its subsequent trough, or lowest point. Between trough and peak, the economy is in an expansion. Expansion is the normal state of the economy; most recessions are brief. However, the time it takes for the economy to return to its previous peak level of activity, or its previous trend path, may be quite extended. According to the NBER chronology, the most recent peak occurred in February 2020; the most recent trough occurred in April 2020. See https://www.nber.org/research/business-cycle-dating/business-cycle-dating-procedure-frequently-asked-questions .

2 U.S. Census Bureau. "Current Population Survey: Design and Methodology." Technical Paper 66, October 2006; https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/methodology/tp-66.pdf .

3 Gilroy, Curtis L. and McIntire, Robert J. "Job Losers, Leavers, and Entrants: A Cyclical Analysis." JSTOR Monthly Labor Review , November 1974, 97 (11), pp. 35-9; http://www.jstor.org/stable/41839192 . Accessed March 7, 2024.

4 Note that during the COVID recession, new-entrant unemployment seems to be equally sensitive (in terms of percentage drop).

5 U.S. Census Bureau, 2006. (See footnote 2.)

6 Lambert, Thomas E. "The Great Resignation in the United States: A Study of Labor Market Segmentation." Taylor & Francis Journals Forum for Social Economics , 2023, 52 (4), pp. 373-86; https://doi.org/10.1080/07360932.2022.2164599 .

7 See https://www.investopedia.com/the-great-resignation-is-officially-over-7963266#:~:text=Key%20Takeaways,have%20weighed%20down%20the%20economy .

8 Gilroy and McIntire, 1974. (See footnote 3.)

9 Weinberg, John. "The Great Recession and Its Aftermath." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Federal Reserve History, 2013; https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/great-recession-and-its-aftermath .

10 See https://www.epi.org/publication/swa-2020-employment-report/#:~:text=No%20matter%20how%20you%20measure,remains%20as%20of%20February%202021 .

11 See https://www.bizjournals.com/bizjournals/news/2022/05/01/the-biggest-cost-of-doing-business.html .

© 2024, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

Business cycle: The fluctuating levels of economic activity in an economy over a period of time measured from the beginning of one recession to the beginning of the next.

Cyclical unemployment: Unemployment associated with recessions in the business cycle.

Frictional unemployment: Unemployment that results when people are new to the job market (for example, recent graduates) or are transitioning from one job to another.

Unemployment rate: The percentage of the labor force that is willing and able to work, does not currently have a job, and is actively looking for employment.

Cite this article

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Stay current with brief essays, scholarly articles, data news, and other information about the economy from the Research Division of the St. Louis Fed.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE RESEARCH DIVISION NEWSLETTER

Research division.

- Legal and Privacy

One Federal Reserve Bank Plaza St. Louis, MO 63102

Information for Visitors

Advertisement

Unemployment Scarring Effects: An Overview and Meta-analysis of Empirical Studies

- Review article

- Published: 17 May 2023

Cite this article

- Mattia Filomena ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4099-9168 1 , 2

942 Accesses

6 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

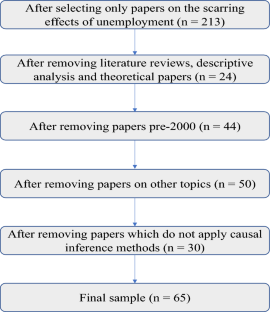

This article reviews the empirical literature on the scarring effects of unemployment, by first presenting an overview of empirical evidence relating to the impact of unemployment spells on subsequent labor market outcomes and then exploiting meta-regression techniques. Empirical evidence is homogeneous in highlighting significant and often persistent wage losses and strong unemployment state dependence. This is confirmed by a meta-regression analysis under the assumption of a common true effect. Heterogeneous findings emerge in the literature, related to the magnitude of these detrimental effects, which are particularly penalizing in terms of labor earnings in case of unemployment periods experienced by laid-off workers. We shed light on further sources of heterogeneity and find that unemployment is particularly scarring for men and when studies’ identification strategy is based on selection on observables.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price excludes VAT (USA) Tax calculation will be finalised during checkout.

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Experiencing Long-Term Unemployment in Europe: A Conclusion

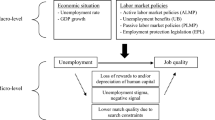

The Effects of Unemployment on Non-monetary Job Quality in Europe: The Moderating Role of Economic Situation and Labor Market Policies

The effects of unemployment assistance on unemployment exits

Data availability.

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Moreover, further outcomes discussed by the literature on scarring are family formation, crime and negative psychological implications in terms of well-being, life satisfaction and mental health (see e.g. Helbling and Sacchi 2014 ; Strandh et al. 2014 ; Mousteri et al. 2018 ; Clark and Lepinteur 2019 ).

A further strand of the recent literature focuses on the effect of adverse labor market conditions at graduation, for example focusing on the effect of local unemployment rate or graduating during a recession (see e.g. Raaum and Roed, 2006 ; Kahn 2010 ; Oreopoulos et al. 2012 ; Kawaguchi and Murao 2014 ; Altonji et al. 2016 ). The consequences of economic downturns on wages, labor supply and social outcomes for young labor market entrants have been recently surveyed by Cockx ( 2016 ), Von Wachter (2020) and Rodriguez et al. ( 2020 ).

The stigma effect means that individuals who have been unemployed face lower chances of being hired because employers may use their past history of unemployment as a negative signal.

Thus, papers using traditional multivariate descriptive analysis, duration models, or OLS regressions with a reduced number of controls which do not properly address endogeneity issues and are unlikely to have a causal interpretation (endogeneity issues are discussed in SubSect. 3.2 ).

For intergenerational scars we mean that studies focused on the effect of parents’ unemployment experiences on the children’ future employment status (see e.g. Karhula et al. 2017 ). For macroeconomic conditions at graduation we mean that we excluded that literature focused on the local unemployment rate at graduation or other local labor market conditions, rather than on individual unemployment experience and state dependence (see e.g. Oreopoulos et al. 2012 ; Raaem and Roed, 2006 ).

When we could not directly retrieve the t -statistics because not reported among the study results, we computed them as the ratio between the estimated unemployment effects ( \({\beta }_{i}\) ) and their standard errors. If studies only displayed the estimated effects and their 95% confidence intervals, the standard error can be calculated by SE = ( ub − lb )/(2 × 1.96), where ub and lb are the upper bound and the lower bound, respectively.

We removed from the meta-regression analysis 8 articles because they did not contain sufficient information to compute the t -statistic of the estimated scarring effect. They are reported in italics in Tables 5 and 6 .

For employment outcomes we mean the likelihood of experiencing future unemployment, the probability to have a job later (employability), the fraction of days spent at work or the hours worked during the following years (labor market participation), the call-backs from employers in case of field experiment. Earning outcomes include hourly wages, labor earnings, income, etc.

Since many studies did not provide precise information on the number of covariates, we approximated \({dk}_{i}\) with the number of observations minus 2. Indeed, given that in microeconometric applications the sample sizes are very often much larger than the number of the parameters, the calculation of the partial correlation coefficient is quite robust to errors in deriving \({dk}_{i}\) (Picchio 2022 ).

The publication bias is the bias arising from the tendency of editors to publish more easily findings consistent with a conventional view or with statistically significant results, whereas studies that find small or no significant effects tend to remain unpublished (Card and Krueger 1995 ).

We employed the Precision Effect Estimate with Standard Error (PEESE) specification because its quadratic form of the standard errors has been proven to be less biased and often more efficient to check for heterogeneity than the FAT-PET specification when there is a nonzero genuine effect (Stanley and Doucouliagos 2014 ). Nevertheless, the results from the FAT-PET specification are very similar to the ones from the PEESE model.

Abebe DS, Hyggen C (2019) Moderators of unemployment and wage scarring during the transition to young adulthood: evidence from Norway. In: Hvinden B, Oreilly J, Schoyen MA, Hyggen C (eds) Negotiating early job insecurity. Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham

Google Scholar

Adascalitei D, Morano CP (2016) Drivers and effects of labour market reforms: evidence from a novel policy compendium. IZA J Labor Policy 5(1):1–32

Article Google Scholar

Ahmad N (2014) State dependence in unemployment. Int J Econ Financ Issues 4(1):93

Altonji JG, Kahn LB, Speer JD (2016) Cashier or consultant? Entry labor market conditions, field of study, and career success. J Law Econ 34(1):S361–S401

Arranz JM, García-Serrano C (2003) Non-employment and subsequent wage losses. Instituto de Estudios Fiscales, No. 19-03

Arranz JM, Davia MA, García-Serrano C (2005) Labour market transitions and wage dynamics in Europe. ISER Working Paper Series, No. 2005-17

Arulampalam W (2001) Is unemployment really scarring? Effects of unemployment experiences on wages. Econ J 111(475):F585–F606

Arulampalam W, Booth AL, Taylor MP (2000) Unemployment persistence. Oxf Econ Pap 52(1):24–50

Arulampalam W, Gregg P, Gregory M (2001) Introduction: unemployment scarring. Econ J 111(475):F577–F584

Ayllón S (2013) Unemployment persistence: not only stigma but discouragement too. Appl Econ Lett 20(1):67–71

Ayllón S, Valbuena J, Plum A (2021) Youth unemployment and stigmatization over the business cycle in Europe. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 84(1):103–129

Baert S, Verhaest D (2019) Unemployment or overeducation: which is a worse signal to employers? De Econ 167(1):1–21

Baumann I (2016) The debate about the consequences of job displacement. Springer, Cham, pp 1–33

Becker, Gary. 1975. Human capital: a theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. Second Edition. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Biewen M, Steffes S (2010) Unemployment persistence: is there evidence for stigma effects? Econ Lett 106(3):188–190

Birkelund GE, Heggebø K, Rogstad J (2017) Additive or multiplicative disadvantage? The scarring effects of unemployment for ethnic minorities. Eur Sociol Rev 33(1):17–29

Borland J (2020) Scarring effects: a review of Australian and international literature. Aust J Labour Econ 23(2):173–188

Bratberg E, Nilsen OA (2000) Transitions from school to work and the early labour market experience. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 62:909–929

Brodeur A, Cook N, Heyes A (2020) Methods matter: p-hacking and publication bias in causal analysis in economics. Am Econ Rev 110(11):3634–3660

Brodeur A, Lé M, Sangnier M, Zylberberg Y (2016) Star wars: the empirics strike back. Am Econ J Appl Econ 8(1):1–32

Burda MC, Mertens A (2001) Estimating wage losses of displaced workers in Germany. Labour Econ 8(1):15–41

Burdett K (1978) A theory of employee job search and quit rates. Am Econ Rev 68(1):212–220

Böheim R, Taylor MP (2002) The search for success: do the unemployed find stable employment? Labour Econ 9(6):717–735

Cameron CA, Gelbach JB, Miller DL (2008) Bootstrap-based improvements for inference with clustered errors. Rev Econ Stat 90(3):414–427

Card D, Krueger AB (1995) Time-series minimum-wage studies: a meta-analysis. Am Econ Rev 85(2):238–243

Chamberlain G (1984) Panel data. Handb Econ 2:1247–1318

Clark AE, Lepinteur A (2019) The causes and consequences of early-adult unemployment: evidence from cohort data. J Econ Behav Organ 166:107–124

Cockx B, Picchio M (2013) Scarring effects of remaining unemployed for long-term unemployed school-leavers. J R Stat Soc A Stat Soc 176(4):951–980

Cockx B (2016) Do youths graduating in a recession incur permanent losses? IZA World Labor

Couch KA (2001) Earnings losses and unemployment of displaced workers in Germany. ILR Rev 54(3):559–572

Deelen A, de Graaf-Zijl M, van den Berge W (2018) Labour market effects of job displacement for prime-age and older workers. IZA J Labor Econ 7(1):3

Dieckhoff M (2011) The effect of unemployment on subsequent job quality in Europe: a comparative study of four countries. Acta Sociol 54(3):233–249

Doiron D, Gørgens T (2008) State dependence in youth labor market experiences, and the evaluation of policy interventions. J Econometr 145(1–2):81–97

Dorsett R, Lucchino P (2018) Young people’s labour market transitions: the role of early experiences. Labour Econ 54:29–46

Doucouliagos H (1995) Worker participation and productivity in labor-managed and participatory capitalist firms: a meta-analysis. ILR Rev 49(1):58–77

Eicher TS, Papageorgiou C, Raftery AE (2011) Default priors and predictive performance in Bayesian model averaging, with application to growth determinants. J Appl Economet 26(1):30–55

Eliason M, Storrie D (2006) Lasting or latent scars? Swedish evidence on the long-term effects of job displacement. J Law Econ 24(4):831–856

Eriksson S, Rooth D-O (2014) Do employers use unemployment as a sorting criterion when hiring? Evidence from a field experiment. Am Econ Rev 104(3):1014–1039

Fallick BC (1996) A review of the recent empirical literature on displaced workers. ILR Rev 50(1):5–16

Farber HS, Herbst CM, Silverman D, Von Watcher T (2019) Whom do employers want? The role of recent employment and unemployment status and age. J Law Econ 37(2):323–349

Farber HS, Silverman D, Von Watcher T (2016) Determinants of callbacks to job applications: an audit study. Am Econ Rev 106(5):314–318

Farber HS, Silverman D, Von Watcher T (2017) Factors determining callbacks to job applications by the unemployed: an audit study. RSF Russell Sage Found J Soc Sci 3(3):168–201

Filomena M, Picchio M (2022) Retirement and health outcomes in a meta-analytical framework. J Econ Surv (forthcoming)

Fraja De, Gianni SL, Rockey J (2021) The wounds that do not heal: the lifetime scar of youth unemployment. Economica 88(352):896–941

Gangji A, Plasman R (2008) Microeconomic analysis of unemployment persistence in Belgium. Int J Manpow 29(3):280–298

Gangji A, Plasman R (2007) The Matthew effect of unemployment: how does it affect wages in Belgium. DULBEA Working Papers 07-19.RS, ULB—Universite Libre de Bruxelles

Gangl M (2004) Welfare states and the scar effects of unemployment: a comparative analysis of the United States and West Germany. Am J Sociol 109(6):1319–1364

Gangl M (2006) Scar effects of unemployment: an assessment of institutional complementarities. Am Sociol Rev 71(6):986–1013

Gartell M (2009) Unemployment and subsequent earnings for Swedish college graduates. A study of scarring effects. Arbetsrapport 2009:2, Institute for Futures Studies

Gaure S, Røed K, Westlie L (2008) The impacts of labor market policies on job search behavior and post-unemployment job quality. IZA Discussion Papers 3802, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA)

Ghirelli C (2015) Scars of early non-employment for low educated youth: evidence and policy lessons from Belgium. IZA J Eur Labor Stud 4(1):20

Gibbons R, Katz LF (1991) Layoffs and lemons. J Law Econ 9(4):351–380

Gregg P (2001) The impact of youth unemployment on adult unemployment in the NCDS. Econ J 111(475):F626–F653

Gregg P, Tominey E (2005) The wage scar from male youth unemployment. Labour Econ 12(4):487–509

Gregory M, Jukes R (2001) Unemployment and subsequent earnings: estimating scarring among British men 1984–94. Econ J 111(475):607–625

Guvenen F, Karahan F, Ozkan S, Song J (2017) Heterogeneous scarring effects of full-year nonemployment. Am Econ Rev 107(5):369–373

Hamermesh DS (1989) What do we know about worker displacement in the US? Ind Relat J Econ Soc 28(1):51–59

Havránek T, Horvath R, Irsova Z, Rusnak M (2015) Cross-country heterogeneity in intertemporal substitution. J Int Econ 96(1):100–118

Havránek T, Stanley TD, Doucouliagos H, Bom P, Geyer-Klingeberg J, Ichiro Iwasaki W, Reed R, Rost K, van Aert RCM (2020) Reporting guidelines for meta-analysis in economics. J Econ Surv 34(3):469–475

Heckman JJ (1979) Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 47(1):153–161

Helbling LA, Sacchi S (2014) Scarring effects of early unemployment among young workers with vocational credentials in Switzerland. Emp Res Voc Educ Train 6(1):12

Heylen V (2011) Scarring, the effects of early career unemployment. In ECPR General conference, 2011/08/24–2011/08/27, University of Iceland, Reykjavik

Hämäläinen K (2003) Education and unemployment: state dependence in unemployment among young people in the 1990s. VATT Institute for Economic Research, No. 312

Jacobson LS, LaLonde RJ, Sullivan DG (1993) Earnings losses of displaced workers. Am Econ Rev 83(4):685–709

Jovanovic B (1979a) Firm-specific capital and turnover. J Polit Econ 87(6):1246–1260

Jovanovic B (1979b) Job matching and the theory of turnover. J Polit Econ 87(5, Part 1):972–990

Kahn LB (2010) The long-term labor market consequences of graduating from college in a bad economy. Labour Econ 17(2):303–316

Karhula A, Lehti H, Erola J (2017) Intergenerational scars? The long-term effects of parental unemployment during a depression. Res Finn Soc 10:87–99

Kawaguchi D, Murao T (2014) Labor-market institutions and long-term effects of youth unemployment. J Money Credit Bank 46(S2):95–116

Kletzer LG (1998) Job displacement. J Econ Perspect 12(1):115–136

Kletzer LG, Fairlie RW (2003) The long-term costs of job displacement for young adult workers. ILR Rev 56(4):682–698

Knights S, Harris MN, Loundes J (2002) Dynamic relationships in the Australian labour market: heterogeneity and state dependence. Econ Record 78(242):284–298

Kroft K, Lange F, Notowidigdo MJ (2013) Duration dependence and labor market conditions: evidence from a field experiment. Q J Econ 128(3):1123–1167

Kuchibhotla M, Orazem PF, Ravi S (2020) The scarring effects of youth joblessness in Sri Lanka. Rev Dev Econ 24(1):269–287

Lazear EP (1986) Raids and offer matching. In: Ehrenberg R (ed) Research in Labor Economics, vol 8. JAI Press, Greenwich

Lockwood B (1991) Information externalities in the labour market and the duration of unemployment. Rev Econ Stud 58(4):733–753

De Luca G, Magnus JR (2011) Bayesian model averaging and weighted-average least squares: equivariance, stability, and numerical issues. Stata Journal 11(4):518–544

Lupi C, Ordine P (2002) Unemployment scarring in high unemployment regions. Econ Bull 10(2):1–8

Magnus JR, De Luca G (2016) Weighted-average least squares (WALS): a survey. J Econ Surv 30(1):117–148

Magnus JR, Powell O, Prüfer P (2010) A comparison of two model averaging techniques with an application to growth empirics. J Econometr 154(2):139–153

Manzoni A, Mooi-Reci I (2011) Early unemployment and subsequent career complexity: a sequence-based perspective. Schmollers Jahrbuch J Appl Soc Sci Stud ZeitschrFür Wirtschaftsund Sozialwissenschaften 131(2):339–348

Mavromaras K, Sloane P, Wei Z (2015) The scarring effects of unemployment, low pay and skills under-utilization in Australia compared. Appl Econ 47(23):2413–2429

Mincer J (1974) Schooling, experience, and earnings. National Bureau of Economic Research Inc, Cambridge

Mooi-Reci I, Ganzeboom HB (2015) Unemployment scarring by gender: human capital depreciation or stigmatization? Longitudinal evidence from the Netherlands, 1980–2000. Soc Sci Res 52:642–658

Mortensen DT (1987) Job search and labor market analysis. In: Ashenfelter O, Layard R (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 2, Chapter 15, pp 849–919, Elsevier

Mortensen DT (1988) Wages, separations, and job tenure: on-the-job specific training or matching? J Law Econ 6(4):445–471

Mousteri V, Daly M, Delaney L (2018) The scarring effect of unemployment on psychological well-being across Europe. Soc Sci Res 72:146–169

Mroz TA, Savage TH (2006) The long-term effects of youth unemployment. J Hum Resour 41(2):259–293

Mundlak Y (1978) On the pooling of time series and cross section data. Econometrica 69–85

Möller J, Umkehrer M (2015) Are there long-term earnings scars from youth unemployment in Germany? Jahrbücher Für Nationalökon Und Stat 235(4–5):474–498

Nekoei A, Weber A (2017) Does extending unemployment benefits improve job quality? American Economic Review 107(2):527–561

Nickell S, Jones P, Quintini G (2002) A picture of job insecurity facing British men. Econ J 112(476):1–27

Nilsen ØA, Reiso KH (2014) Scarring effects of early-career unemployment. Nord Econ Policy Rev 1:13–46

Nordström Skans O (2011) Scarring effects of the first labor market experience. IZA Discussion Papers 5565, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA)

Nunley JM, Pugh A, Romero N, Alan Seals R (2017) The effects of unemployment and underemployment on employment opportunities: results from a correspondence audit of the labor market for college graduates. ILR Rev 70(3):642–669

Nüß P (2018) Duration dependence as an unemployment stigma: evidence from a field experiment in Germany. Technical report, Economics Working Paper.

Oberholzer-Gee F (2008) Nonemployment stigma as rational herding: a field experiment. J Econ Behav Organ 65(1):30–40

Omori Y (1997) Stigma effects of nonemployment. Econ Inq 35(2):394–416

Ordine P, Rose G (2015) Educational mismatch and unemployment scarring. Int J Manpower 36(5):733

Oreopoulos P, Von Watcher T, Heisz A (2012) The short- and long-term career effects of graduating in a recession. Am Econ J Appl Econ 4(1):1–29

Pastore F, Quintano C, Rocca A (2021) Some young people have all the luck! The duration dependence of the school-to-work transition in Europe. Labour Econ 70:101982

Petreski M, Mojsoska-Blazevski N, Bergolo M (2017) Labor-market scars when youth unemployment is extremely high: evidence from Macedonia. East Eur Econ 55(2):168–196

Picchio M, van Ours JC (2013) Retaining through training even for older workers. Econ Educ Rev 32(1):29–48

Picchio M (2022) Meta-analysis. In: Zimmermann KF (eds) Handbook of labor, human resources and population economics. Springer, Cham. (forthcoming)

Pissarides CA (1992) Loss of skill during unemployment and the persistence of employment shocks. Q J Econ 107(4):1371–1391

Plum A, Ayllón S (2015) Heterogeneity in unemployment state dependence. Econ Lett 136:85–87

Raaum O, Røed K (2006) Do business cycle conditions at the time of labor market entry affect future employment prospects? Rev Econ Stat 88(2):193–210

Rodriguez JS, Colston J, Wu Z, Chen Z (2020) Graduating during a recession: a literature review of the effects of recessions for college graduates. Centre for College Workforce Transitions (CCWT), University of Wisconsin

Schmillen A, Umkehrer M (2017) The scars of youth: effects of early-career unemployment on future unemployment experience. Int Labour Rev 156(3–4):465–494

Shi LP, Wang S (2021) Demand-side consequences of unemployment and horizontal skill mismatches across national contexts: an employer-based factorial survey experiment. Soc Sci Res 104:102668

Spence M (1973) Job market signaling. Q J Econ 87(3):355–374

Spivey C (2005) Time off at what price? The effects of career interruptions on earnings. ILR Rev 59(1):119–140

Stanley TD (2005) Beyond publication bias. J Econ Surv 19(3):309–345

Stanley TD (2008) Meta-regression methods for detecting and estimating empirical effects in the presence of publication selection. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 70(1):103–127

Stanley TD, Doucouliagos H (2014) Meta-regression approximations to reduce publication selection bias. Res Synth Methods 5(1):60–78

Stewart MB (2007) The interrelated dynamics of unemployment and low-wage employment. J Appl Economet 22(3):511–531

Strandh M, Winefield A, Nilsson K, Hammarström A (2014) Unemployment and mental health scarring during the life course. Eur J Pub Health 24(3):440–445

Tanzi GM (2022) Scars of youth non-employment and labour market conditions. Italian Econ J (forthcoming)

Tatsiramos K (2009) Unemployment insurance in Europe: unemployment duration and subsequent employment stability. J Eur Econ Assoc 7(6):1225–1260

Tumino A (2015) The scarring effect of unemployment from the early’90s to the great recession. ISER Working Paper Series, No. 2015-05

Ugur M (2014) Corruption’s direct effects on per-capita income growth: a meta-analysis. J Econ Surv 28(3):472–490

Verho J (2008) Scars of recession: the long-term costs of the Finnish economic crisis. Working Paper Series 2008:9, IFAU—Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy

Vishwanath T (1989) Job search, stigma effect, and escape rate from unemployment. J Law Econ 7(4):487–502

Von Wachter T (2020) The persistent effects of initial labor market conditions for young adults and their sources. J Econ Perspect 34(4):168–194

Vooren M, Haelermans C, Groot W, van den Brink HM (2019) The effectiveness of active labor market policies: a meta-analysis. J Econ Surv 33(1):125–149