Dissertation Structure & Layout 101: How to structure your dissertation, thesis or research project.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Reviewed By: David Phair (PhD) | July 2019

So, you’ve got a decent understanding of what a dissertation is , you’ve chosen your topic and hopefully you’ve received approval for your research proposal . Awesome! Now its time to start the actual dissertation or thesis writing journey.

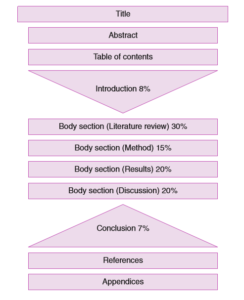

To craft a high-quality document, the very first thing you need to understand is dissertation structure . In this post, we’ll walk you through the generic dissertation structure and layout, step by step. We’ll start with the big picture, and then zoom into each chapter to briefly discuss the core contents. If you’re just starting out on your research journey, you should start with this post, which covers the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis .

*The Caveat *

In this post, we’ll be discussing a traditional dissertation/thesis structure and layout, which is generally used for social science research across universities, whether in the US, UK, Europe or Australia. However, some universities may have small variations on this structure (extra chapters, merged chapters, slightly different ordering, etc).

So, always check with your university if they have a prescribed structure or layout that they expect you to work with. If not, it’s safe to assume the structure we’ll discuss here is suitable. And even if they do have a prescribed structure, you’ll still get value from this post as we’ll explain the core contents of each section.

Overview: S tructuring a dissertation or thesis

- Acknowledgements page

- Abstract (or executive summary)

- Table of contents , list of figures and tables

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Literature review

- Chapter 3: Methodology

- Chapter 4: Results

- Chapter 5: Discussion

- Chapter 6: Conclusion

- Reference list

As I mentioned, some universities will have slight variations on this structure. For example, they want an additional “personal reflection chapter”, or they might prefer the results and discussion chapter to be merged into one. Regardless, the overarching flow will always be the same, as this flow reflects the research process , which we discussed here – i.e.:

- The introduction chapter presents the core research question and aims .

- The literature review chapter assesses what the current research says about this question.

- The methodology, results and discussion chapters go about undertaking new research about this question.

- The conclusion chapter (attempts to) answer the core research question .

In other words, the dissertation structure and layout reflect the research process of asking a well-defined question(s), investigating, and then answering the question – see below.

To restate that – the structure and layout of a dissertation reflect the flow of the overall research process . This is essential to understand, as each chapter will make a lot more sense if you “get” this concept. If you’re not familiar with the research process, read this post before going further.

Right. Now that we’ve covered the big picture, let’s dive a little deeper into the details of each section and chapter. Oh and by the way, you can also grab our free dissertation/thesis template here to help speed things up.

The title page of your dissertation is the very first impression the marker will get of your work, so it pays to invest some time thinking about your title. But what makes for a good title? A strong title needs to be 3 things:

- Succinct (not overly lengthy or verbose)

- Specific (not vague or ambiguous)

- Representative of the research you’re undertaking (clearly linked to your research questions)

Typically, a good title includes mention of the following:

- The broader area of the research (i.e. the overarching topic)

- The specific focus of your research (i.e. your specific context)

- Indication of research design (e.g. quantitative , qualitative , or mixed methods ).

For example:

A quantitative investigation [research design] into the antecedents of organisational trust [broader area] in the UK retail forex trading market [specific context/area of focus].

Again, some universities may have specific requirements regarding the format and structure of the title, so it’s worth double-checking expectations with your institution (if there’s no mention in the brief or study material).

Acknowledgements

This page provides you with an opportunity to say thank you to those who helped you along your research journey. Generally, it’s optional (and won’t count towards your marks), but it is academic best practice to include this.

So, who do you say thanks to? Well, there’s no prescribed requirements, but it’s common to mention the following people:

- Your dissertation supervisor or committee.

- Any professors, lecturers or academics that helped you understand the topic or methodologies.

- Any tutors, mentors or advisors.

- Your family and friends, especially spouse (for adult learners studying part-time).

There’s no need for lengthy rambling. Just state who you’re thankful to and for what (e.g. thank you to my supervisor, John Doe, for his endless patience and attentiveness) – be sincere. In terms of length, you should keep this to a page or less.

Abstract or executive summary

The dissertation abstract (or executive summary for some degrees) serves to provide the first-time reader (and marker or moderator) with a big-picture view of your research project. It should give them an understanding of the key insights and findings from the research, without them needing to read the rest of the report – in other words, it should be able to stand alone .

For it to stand alone, your abstract should cover the following key points (at a minimum):

- Your research questions and aims – what key question(s) did your research aim to answer?

- Your methodology – how did you go about investigating the topic and finding answers to your research question(s)?

- Your findings – following your own research, what did do you discover?

- Your conclusions – based on your findings, what conclusions did you draw? What answers did you find to your research question(s)?

So, in much the same way the dissertation structure mimics the research process, your abstract or executive summary should reflect the research process, from the initial stage of asking the original question to the final stage of answering that question.

In practical terms, it’s a good idea to write this section up last , once all your core chapters are complete. Otherwise, you’ll end up writing and rewriting this section multiple times (just wasting time). For a step by step guide on how to write a strong executive summary, check out this post .

Need a helping hand?

Table of contents

This section is straightforward. You’ll typically present your table of contents (TOC) first, followed by the two lists – figures and tables. I recommend that you use Microsoft Word’s automatic table of contents generator to generate your TOC. If you’re not familiar with this functionality, the video below explains it simply:

If you find that your table of contents is overly lengthy, consider removing one level of depth. Oftentimes, this can be done without detracting from the usefulness of the TOC.

Right, now that the “admin” sections are out of the way, its time to move on to your core chapters. These chapters are the heart of your dissertation and are where you’ll earn the marks. The first chapter is the introduction chapter – as you would expect, this is the time to introduce your research…

It’s important to understand that even though you’ve provided an overview of your research in your abstract, your introduction needs to be written as if the reader has not read that (remember, the abstract is essentially a standalone document). So, your introduction chapter needs to start from the very beginning, and should address the following questions:

- What will you be investigating (in plain-language, big picture-level)?

- Why is that worth investigating? How is it important to academia or business? How is it sufficiently original?

- What are your research aims and research question(s)? Note that the research questions can sometimes be presented at the end of the literature review (next chapter).

- What is the scope of your study? In other words, what will and won’t you cover ?

- How will you approach your research? In other words, what methodology will you adopt?

- How will you structure your dissertation? What are the core chapters and what will you do in each of them?

These are just the bare basic requirements for your intro chapter. Some universities will want additional bells and whistles in the intro chapter, so be sure to carefully read your brief or consult your research supervisor.

If done right, your introduction chapter will set a clear direction for the rest of your dissertation. Specifically, it will make it clear to the reader (and marker) exactly what you’ll be investigating, why that’s important, and how you’ll be going about the investigation. Conversely, if your introduction chapter leaves a first-time reader wondering what exactly you’ll be researching, you’ve still got some work to do.

Now that you’ve set a clear direction with your introduction chapter, the next step is the literature review . In this section, you will analyse the existing research (typically academic journal articles and high-quality industry publications), with a view to understanding the following questions:

- What does the literature currently say about the topic you’re investigating?

- Is the literature lacking or well established? Is it divided or in disagreement?

- How does your research fit into the bigger picture?

- How does your research contribute something original?

- How does the methodology of previous studies help you develop your own?

Depending on the nature of your study, you may also present a conceptual framework towards the end of your literature review, which you will then test in your actual research.

Again, some universities will want you to focus on some of these areas more than others, some will have additional or fewer requirements, and so on. Therefore, as always, its important to review your brief and/or discuss with your supervisor, so that you know exactly what’s expected of your literature review chapter.

Now that you’ve investigated the current state of knowledge in your literature review chapter and are familiar with the existing key theories, models and frameworks, its time to design your own research. Enter the methodology chapter – the most “science-ey” of the chapters…

In this chapter, you need to address two critical questions:

- Exactly HOW will you carry out your research (i.e. what is your intended research design)?

- Exactly WHY have you chosen to do things this way (i.e. how do you justify your design)?

Remember, the dissertation part of your degree is first and foremost about developing and demonstrating research skills . Therefore, the markers want to see that you know which methods to use, can clearly articulate why you’ve chosen then, and know how to deploy them effectively.

Importantly, this chapter requires detail – don’t hold back on the specifics. State exactly what you’ll be doing, with who, when, for how long, etc. Moreover, for every design choice you make, make sure you justify it.

In practice, you will likely end up coming back to this chapter once you’ve undertaken all your data collection and analysis, and revise it based on changes you made during the analysis phase. This is perfectly fine. Its natural for you to add an additional analysis technique, scrap an old one, etc based on where your data lead you. Of course, I’m talking about small changes here – not a fundamental switch from qualitative to quantitative, which will likely send your supervisor in a spin!

You’ve now collected your data and undertaken your analysis, whether qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods. In this chapter, you’ll present the raw results of your analysis . For example, in the case of a quant study, you’ll present the demographic data, descriptive statistics, inferential statistics , etc.

Typically, Chapter 4 is simply a presentation and description of the data, not a discussion of the meaning of the data. In other words, it’s descriptive, rather than analytical – the meaning is discussed in Chapter 5. However, some universities will want you to combine chapters 4 and 5, so that you both present and interpret the meaning of the data at the same time. Check with your institution what their preference is.

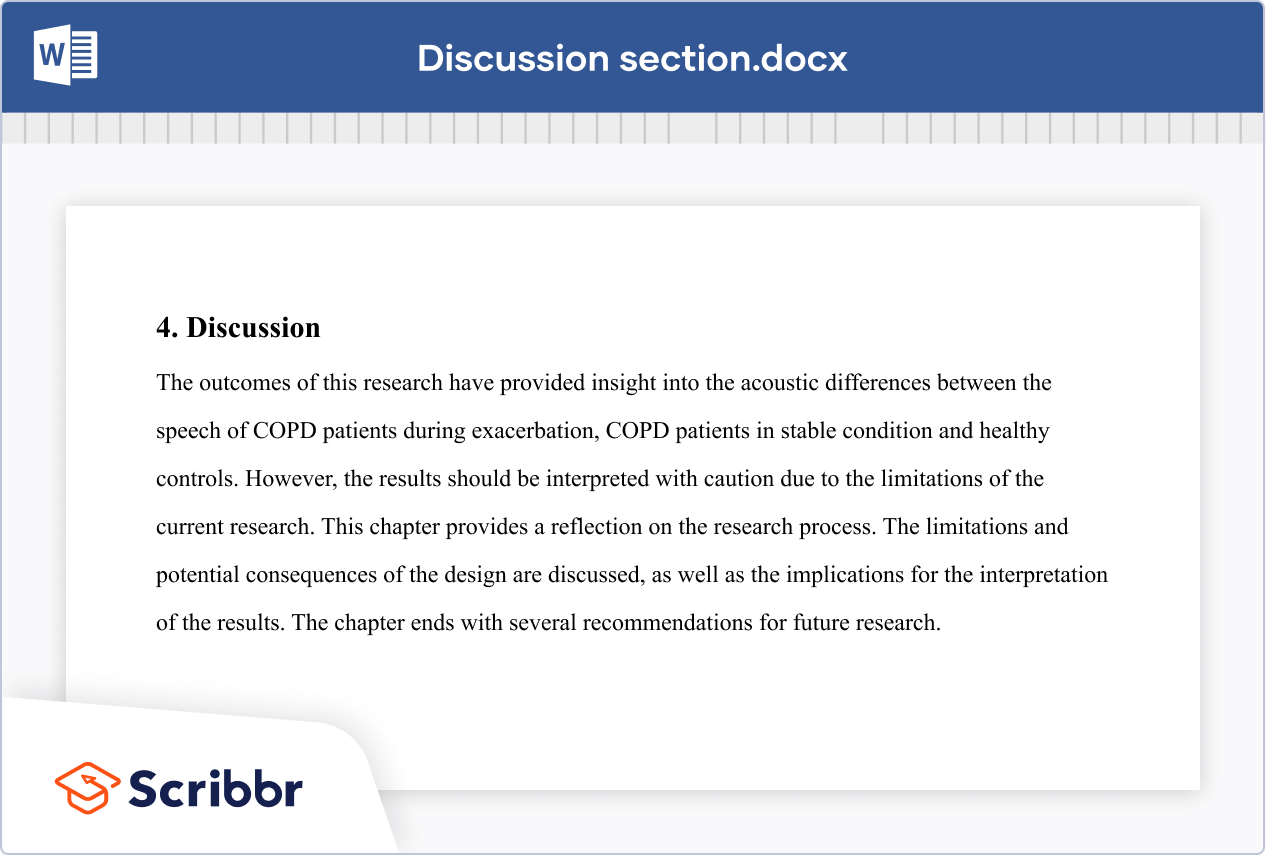

Now that you’ve presented the data analysis results, its time to interpret and analyse them. In other words, its time to discuss what they mean, especially in relation to your research question(s).

What you discuss here will depend largely on your chosen methodology. For example, if you’ve gone the quantitative route, you might discuss the relationships between variables . If you’ve gone the qualitative route, you might discuss key themes and the meanings thereof. It all depends on what your research design choices were.

Most importantly, you need to discuss your results in relation to your research questions and aims, as well as the existing literature. What do the results tell you about your research questions? Are they aligned with the existing research or at odds? If so, why might this be? Dig deep into your findings and explain what the findings suggest, in plain English.

The final chapter – you’ve made it! Now that you’ve discussed your interpretation of the results, its time to bring it back to the beginning with the conclusion chapter . In other words, its time to (attempt to) answer your original research question s (from way back in chapter 1). Clearly state what your conclusions are in terms of your research questions. This might feel a bit repetitive, as you would have touched on this in the previous chapter, but its important to bring the discussion full circle and explicitly state your answer(s) to the research question(s).

Next, you’ll typically discuss the implications of your findings . In other words, you’ve answered your research questions – but what does this mean for the real world (or even for academia)? What should now be done differently, given the new insight you’ve generated?

Lastly, you should discuss the limitations of your research, as well as what this means for future research in the area. No study is perfect, especially not a Masters-level. Discuss the shortcomings of your research. Perhaps your methodology was limited, perhaps your sample size was small or not representative, etc, etc. Don’t be afraid to critique your work – the markers want to see that you can identify the limitations of your work. This is a strength, not a weakness. Be brutal!

This marks the end of your core chapters – woohoo! From here on out, it’s pretty smooth sailing.

The reference list is straightforward. It should contain a list of all resources cited in your dissertation, in the required format, e.g. APA , Harvard, etc.

It’s essential that you use reference management software for your dissertation. Do NOT try handle your referencing manually – its far too error prone. On a reference list of multiple pages, you’re going to make mistake. To this end, I suggest considering either Mendeley or Zotero. Both are free and provide a very straightforward interface to ensure that your referencing is 100% on point. I’ve included a simple how-to video for the Mendeley software (my personal favourite) below:

Some universities may ask you to include a bibliography, as opposed to a reference list. These two things are not the same . A bibliography is similar to a reference list, except that it also includes resources which informed your thinking but were not directly cited in your dissertation. So, double-check your brief and make sure you use the right one.

The very last piece of the puzzle is the appendix or set of appendices. This is where you’ll include any supporting data and evidence. Importantly, supporting is the keyword here.

Your appendices should provide additional “nice to know”, depth-adding information, which is not critical to the core analysis. Appendices should not be used as a way to cut down word count (see this post which covers how to reduce word count ). In other words, don’t place content that is critical to the core analysis here, just to save word count. You will not earn marks on any content in the appendices, so don’t try to play the system!

Time to recap…

And there you have it – the traditional dissertation structure and layout, from A-Z. To recap, the core structure for a dissertation or thesis is (typically) as follows:

- Acknowledgments page

Most importantly, the core chapters should reflect the research process (asking, investigating and answering your research question). Moreover, the research question(s) should form the golden thread throughout your dissertation structure. Everything should revolve around the research questions, and as you’ve seen, they should form both the start point (i.e. introduction chapter) and the endpoint (i.e. conclusion chapter).

I hope this post has provided you with clarity about the traditional dissertation/thesis structure and layout. If you have any questions or comments, please leave a comment below, or feel free to get in touch with us. Also, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach Blog .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

36 Comments

many thanks i found it very useful

Glad to hear that, Arun. Good luck writing your dissertation.

Such clear practical logical advice. I very much needed to read this to keep me focused in stead of fretting.. Perfect now ready to start my research!

what about scientific fields like computer or engineering thesis what is the difference in the structure? thank you very much

Thanks so much this helped me a lot!

Very helpful and accessible. What I like most is how practical the advice is along with helpful tools/ links.

Thanks Ade!

Thank you so much sir.. It was really helpful..

You’re welcome!

Hi! How many words maximum should contain the abstract?

Thank you so much 😊 Find this at the right moment

You’re most welcome. Good luck with your dissertation.

best ever benefit i got on right time thank you

Many times Clarity and vision of destination of dissertation is what makes the difference between good ,average and great researchers the same way a great automobile driver is fast with clarity of address and Clear weather conditions .

I guess Great researcher = great ideas + knowledge + great and fast data collection and modeling + great writing + high clarity on all these

You have given immense clarity from start to end.

Morning. Where will I write the definitions of what I’m referring to in my report?

Thank you so much Derek, I was almost lost! Thanks a tonnnn! Have a great day!

Thanks ! so concise and valuable

This was very helpful. Clear and concise. I know exactly what to do now.

Thank you for allowing me to go through briefly. I hope to find time to continue.

Really useful to me. Thanks a thousand times

Very interesting! It will definitely set me and many more for success. highly recommended.

Thank you soo much sir, for the opportunity to express my skills

Usefull, thanks a lot. Really clear

Very nice and easy to understand. Thank you .

That was incredibly useful. Thanks Grad Coach Crew!

My stress level just dropped at least 15 points after watching this. Just starting my thesis for my grad program and I feel a lot more capable now! Thanks for such a clear and helpful video, Emma and the GradCoach team!

Do we need to mention the number of words the dissertation contains in the main document?

It depends on your university’s requirements, so it would be best to check with them 🙂

Such a helpful post to help me get started with structuring my masters dissertation, thank you!

Great video; I appreciate that helpful information

It is so necessary or avital course

This blog is very informative for my research. Thank you

Doctoral students are required to fill out the National Research Council’s Survey of Earned Doctorates

wow this is an amazing gain in my life

This is so good

How can i arrange my specific objectives in my dissertation?

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is A Literature Review (In A Dissertation Or Thesis) - Grad Coach - […] is to write the actual literature review chapter (this is usually the second chapter in a typical dissertation or…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- How it works

How to Structure a Dissertation – A Step by Step Guide

Published by Owen Ingram at August 11th, 2021 , Revised On September 20, 2023

A dissertation – sometimes called a thesis – is a long piece of information backed up by extensive research. This one, huge piece of research is what matters the most when students – undergraduates and postgraduates – are in their final year of study.

On the other hand, some institutions, especially in the case of undergraduate students, may or may not require students to write a dissertation. Courses are offered instead. This generally depends on the requirements of that particular institution.

If you are unsure about how to structure your dissertation or thesis, this article will offer you some guidelines to work out what the most important segments of a dissertation paper are and how you should organise them. Why is structure so important in research, anyway?

One way to answer that, as Abbie Hoffman aptly put it, is because: “Structure is more important than content in the transmission of information.”

Also Read: How to write a dissertation – step by step guide .

How to Structure a Dissertation or Thesis

It should be noted that the exact structure of your dissertation will depend on several factors, such as:

- Your research approach (qualitative/quantitative)

- The nature of your research design (exploratory/descriptive etc.)

- The requirements set for forth by your academic institution.

- The discipline or field your study belongs to. For instance, if you are a humanities student, you will need to develop your dissertation on the same pattern as any long essay .

This will include developing an overall argument to support the thesis statement and organizing chapters around theories or questions. The dissertation will be structured such that it starts with an introduction , develops on the main idea in its main body paragraphs and is then summarised in conclusion .

However, if you are basing your dissertation on primary or empirical research, you will be required to include each of the below components. In most cases of dissertation writing, each of these elements will have to be written as a separate chapter.

But depending on the word count you are provided with and academic subject, you may choose to combine some of these elements.

For example, sciences and engineering students often present results and discussions together in one chapter rather than two different chapters.

If you have any doubts about structuring your dissertation or thesis, it would be a good idea to consult with your academic supervisor and check your department’s requirements.

Parts of a Dissertation or Thesis

Your dissertation will start with a t itle page that will contain details of the author/researcher, research topic, degree program (the paper is to be submitted for), and research supervisor. In other words, a title page is the opening page containing all the names and title related to your research.

The name of your university, logo, student ID and submission date can also be presented on the title page. Many academic programs have stringent rules for formatting the dissertation title page.

Acknowledgements

The acknowledgments section allows you to thank those who helped you with your dissertation project. You might want to mention the names of your academic supervisor, family members, friends, God, and participants of your study whose contribution and support enabled you to complete your work.

However, the acknowledgments section is usually optional.

Tip: Many students wrongly assume that they need to thank everyone…even those who had little to no contributions towards the dissertation. This is not the case. You only need to thank those who were directly involved in the research process, such as your participants/volunteers, supervisor(s) etc.

Perhaps the smallest yet important part of a thesis, an abstract contains 5 parts:

- A brief introduction of your research topic.

- The significance of your research.

- A line or two about the methodology that was used.

- The results and what they mean (briefly); their interpretation(s).

- And lastly, a conclusive comment regarding the results’ interpretation(s) as conclusion .

Stuck on a difficult dissertation? We can help!

Our Essay Writing Service Features:

- Expert UK Writers

- Plagiarism-free

- Timely Delivery

- Thorough Research

- Rigorous Quality Control

“ Our expert dissertation writers can help you with all stages of the dissertation writing process including topic research and selection, dissertation plan, dissertation proposal , methodology , statistical analysis , primary and secondary research, findings and analysis and complete dissertation writing. “

Tip: Make sure to highlight key points to help readers figure out the scope and findings of your research study without having to read the entire dissertation. The abstract is your first chance to impress your readers. So, make sure to get it right. Here are detailed guidelines on how to write abstract for dissertation .

Table of Contents

Table of contents is the section of a dissertation that guides each section of the dissertation paper’s contents. Depending on the level of detail in a table of contents, the most useful headings are listed to provide the reader the page number on which said information may be found at.

Table of contents can be inserted automatically as well as manually using the Microsoft Word Table of Contents feature.

List of Figures and Tables

If your dissertation paper uses several illustrations, tables and figures, you might want to present them in a numbered list in a separate section . Again, this list of tables and figures can be auto-created and auto inserted using the Microsoft Word built-in feature.

List of Abbreviations

Dissertations that include several abbreviations can also have an independent and separate alphabetised list of abbreviations so readers can easily figure out their meanings.

If you think you have used terms and phrases in your dissertation that readers might not be familiar with, you can create a glossary that lists important phrases and terms with their meanings explained.

Looking for dissertation help?

Researchprospect to the rescue then.

We have expert writers on our team who are skilled at helping students with quantitative dissertations across a variety of STEM disciplines. Guaranteeing 100% satisfaction!

Introduction

Introduction chapter briefly introduces the purpose and relevance of your research topic.

Here, you will be expected to list the aim and key objectives of your research so your readers can easily understand what the following chapters of the dissertation will cover. A good dissertation introduction section incorporates the following information:

- It provides background information to give context to your research.

- It clearly specifies the research problem you wish to address with your research. When creating research questions , it is important to make sure your research’s focus and scope are neither too broad nor too narrow.

- it demonstrates how your research is relevant and how it would contribute to the existing knowledge.

- It provides an overview of the structure of your dissertation. The last section of an introduction contains an outline of the following chapters. It could start off with something like: “In the following chapter, past literature has been reviewed and critiqued. The proceeding section lays down major research findings…”

- Theoretical framework – under a separate sub-heading – is also provided within the introductory chapter. Theoretical framework deals with the basic, underlying theory or theories that the research revolves around.

All the information presented under this section should be relevant, clear, and engaging. The readers should be able to figure out the what, why, when, and how of your study once they have read the introduction. Here are comprehensive guidelines on how to structure the introduction to the dissertation .

“Overwhelmed by tight deadlines and tons of assignments to write? There is no need to panic! Our expert academics can help you with every aspect of your dissertation – from topic creation and research problem identification to choosing the methodological approach and data analysis.”

Literature Review

The literature review chapter presents previous research performed on the topic and improves your understanding of the existing literature on your chosen topic. This is usually organised to complement your primary research work completed at a later stage.

Make sure that your chosen academic sources are authentic and up-to-date. The literature review chapter must be comprehensive and address the aims and objectives as defined in the introduction chapter. Here is what your literature research chapter should aim to achieve:

- Data collection from authentic and relevant academic sources such as books, journal articles and research papers.

- Analytical assessment of the information collected from those sources; this would involve a critiquing the reviewed researches that is, what their strengths/weaknesses are, why the research method they employed is better than others, importance of their findings, etc.

- Identifying key research gaps, conflicts, patterns, and theories to get your point across to the reader effectively.

While your literature review should summarise previous literature, it is equally important to make sure that you develop a comprehensible argument or structure to justify your research topic. It would help if you considered keeping the following questions in mind when writing the literature review:

- How does your research work fill a certain gap in exiting literature?

- Did you adopt/adapt a new research approach to investigate the topic?

- Does your research solve an unresolved problem?

- Is your research dealing with some groundbreaking topic or theory that others might have overlooked?

- Is your research taking forward an existing theoretical discussion?

- Does your research strengthen and build on current knowledge within your area of study? This is otherwise known as ‘adding to the existing body of knowledge’ in academic circles.

Tip: You might want to establish relationships between variables/concepts to provide descriptive answers to some or all of your research questions. For instance, in case of quantitative research, you might hypothesise that variable A is positively co-related to variable B that is, one increases and so does the other one.

Research Methodology

The methods and techniques ( secondary and/or primar y) employed to collect research data are discussed in detail in the Methodology chapter. The most commonly used primary data collection methods are:

- questionnaires

- focus groups

- observations

Essentially, the methodology chapter allows the researcher to explain how he/she achieved the findings, why they are reliable and how they helped him/her test the research hypotheses or address the research problem.

You might want to consider the following when writing methodology for the dissertation:

- Type of research and approach your work is based on. Some of the most widely used types of research include experimental, quantitative and qualitative methodologies.

- Data collection techniques that were employed such as questionnaires, surveys, focus groups, observations etc.

- Details of how, when, where, and what of the research that was conducted.

- Data analysis strategies employed (for instance, regression analysis).

- Software and tools used for data analysis (Excel, STATA, SPSS, lab equipment, etc.).

- Research limitations to highlight any hurdles you had to overcome when carrying our research. Limitations might or might not be mentioned within research methodology. Some institutions’ guidelines dictate they be mentioned under a separate section alongside recommendations.

- Justification of your selection of research approach and research methodology.

Here is a comprehensive article on how to structure a dissertation methodology .

Research Findings

In this section, you present your research findings. The dissertation findings chapter is built around the research questions, as outlined in the introduction chapter. Report findings that are directly relevant to your research questions.

Any information that is not directly relevant to research questions or hypotheses but could be useful for the readers can be placed under the Appendices .

As indicated above, you can either develop a standalone chapter to present your findings or combine them with the discussion chapter. This choice depends on the type of research involved and the academic subject, as well as what your institution’s academic guidelines dictate.

For example, it is common to have both findings and discussion grouped under the same section, particularly if the dissertation is based on qualitative research data.

On the other hand, dissertations that use quantitative or experimental data should present findings and analysis/discussion in two separate chapters. Here are some sample dissertations to help you figure out the best structure for your own project.

Sample Dissertation

Tip: Try to present as many charts, graphs, illustrations and tables in the findings chapter to improve your data presentation. Provide their qualitative interpretations alongside, too. Refrain from explaining the information that is already evident from figures and tables.

The findings are followed by the Discussion chapter , which is considered the heart of any dissertation paper. The discussion section is an opportunity for you to tie the knots together to address the research questions and present arguments, models and key themes.

This chapter can make or break your research.

The discussion chapter does not require any new data or information because it is more about the interpretation(s) of the data you have already collected and presented. Here are some questions for you to think over when writing the discussion chapter:

- Did your work answer all the research questions or tested the hypothesis?

- Did you come up with some unexpected results for which you have to provide an additional explanation or justification?

- Are there any limitations that could have influenced your research findings?

Here is an article on how to structure a dissertation discussion .

Conclusions corresponding to each research objective are provided in the Conclusion section . This is usually done by revisiting the research questions to finally close the dissertation. Some institutions may specifically ask for recommendations to evaluate your critical thinking.

By the end, the readers should have a clear apprehension of your fundamental case with a focus on what methods of research were employed and what you achieved from this research.

Quick Question: Does the conclusion chapter reflect on the contributions your research work will make to existing knowledge?

Answer: Yes, the conclusion chapter of the research paper typically includes a reflection on the research’s contributions to existing knowledge. In the “conclusion chapter”, you have to summarise the key findings and discuss how they add value to the existing literature on the current topic.

Reference list

All academic sources that you collected information from should be cited in-text and also presented in a reference list (or a bibliography in case you include references that you read for the research but didn’t end up citing in the text), so the readers can easily locate the source of information when/if needed.

At most UK universities, Harvard referencing is the recommended style of referencing. It has strict and specific requirements on how to format a reference resource. Other common styles of referencing include MLA, APA, Footnotes, etc.

Each chapter of the dissertation should have relevant information. Any information that is not directly relevant to your research topic but your readers might be interested in (interview transcripts etc.) should be moved under the Appendices section .

Things like questionnaires, survey items or readings that were used in the study’s experiment are mostly included under appendices.

An Outline of Dissertation/Thesis Structure

How can We Help you with your Dissertation?

If you are still unsure about how to structure a dissertation or thesis, or simply lack the motivation to kick start your dissertation project, you might be interested in our dissertation services .

If you are still unsure about how to structure a dissertation or thesis, or lack the motivation to kick start your dissertation project, you might be interested in our dissertation services.

Whether you need help with individual chapters, proposals or the full dissertation paper, we have PhD-qualified writers who will write your paper to the highest academic standard. ResearchProspect is UK-based, and a UK-registered business, which means the UK consumer law protects all our clients.

All You Need to Know About Us Learn More About Our Dissertation Services

FAQs About Structure a Dissertation

What does the title page of a dissertation contain.

The title page will contain details of the author/researcher, research topic , degree program (the paper is to be submitted for) and research supervisor’s name(s). The name of your university, logo, student number and submission date can also be presented on the title page.

What is the purpose of adding acknowledgement?

The acknowledgements section allows you to thank those who helped you with your dissertation project. You might want to mention the names of your academic supervisor, family members, friends, God and participants of your study whose contribution and support enabled you to complete your work.

Can I omit the glossary from the dissertation?

Yes, but only if you think that your paper does not contain any terms or phrases that the reader might not understand. If you think you have used them in the paper, you must create a glossary that lists important phrases and terms with their meanings explained.

What is the purpose of appendices in a dissertation?

Any information that is not directly relevant to research questions or hypotheses but could be useful for the readers can be placed under the Appendices, such as questionnaire that was used in the study.

Which referencing style should I use in my dissertation?

You can use any of the referencing styles such as APA, MLA, and Harvard, according to the recommendation of your university; however, almost all UK institutions prefer Harvard referencing style .

What is the difference between references and bibliography?

References contain all the works that you read up and used and therefore, cited within the text of your thesis. However, in case you read on some works and resources that you didn’t end up citing in-text, they will be referenced in what is called a bibliography.

Additional readings might also be present alongside each bibliography entry for readers.

You May Also Like

If your dissertation includes many abbreviations, it would make sense to define all these abbreviations in a list of abbreviations in alphabetical order.

Dissertation Methodology is the crux of dissertation project. In this article, we will provide tips for you to write an amazing dissertation methodology.

Your dissertation introduction chapter provides detailed information on the research problem, significance of research, and research aim & objectives.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

Graduate School

- Make a Gift

Organizing and Formatting Your Thesis and Dissertation

Learn about overall organization of your thesis or dissertation. Then, find details for formatting your preliminaries, text, and supplementaries.

Overall Organization

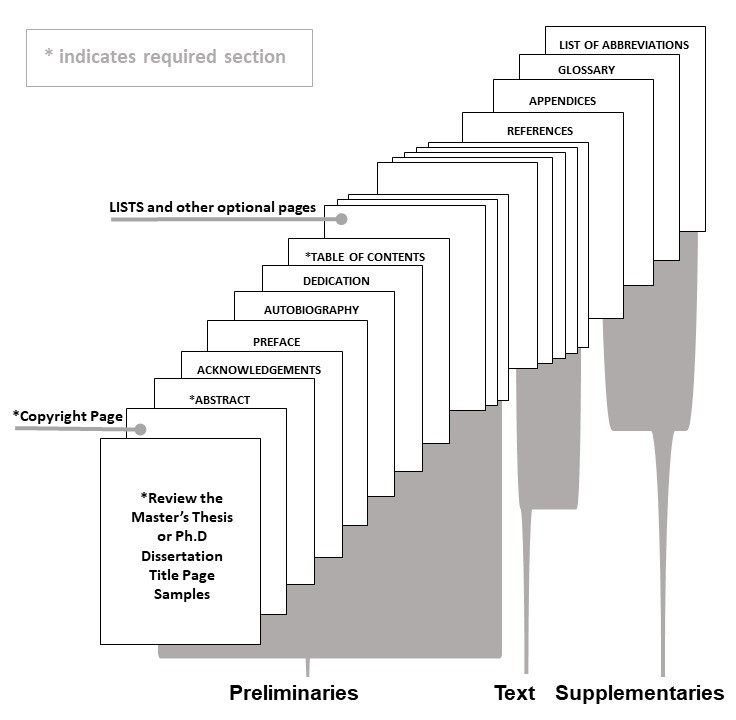

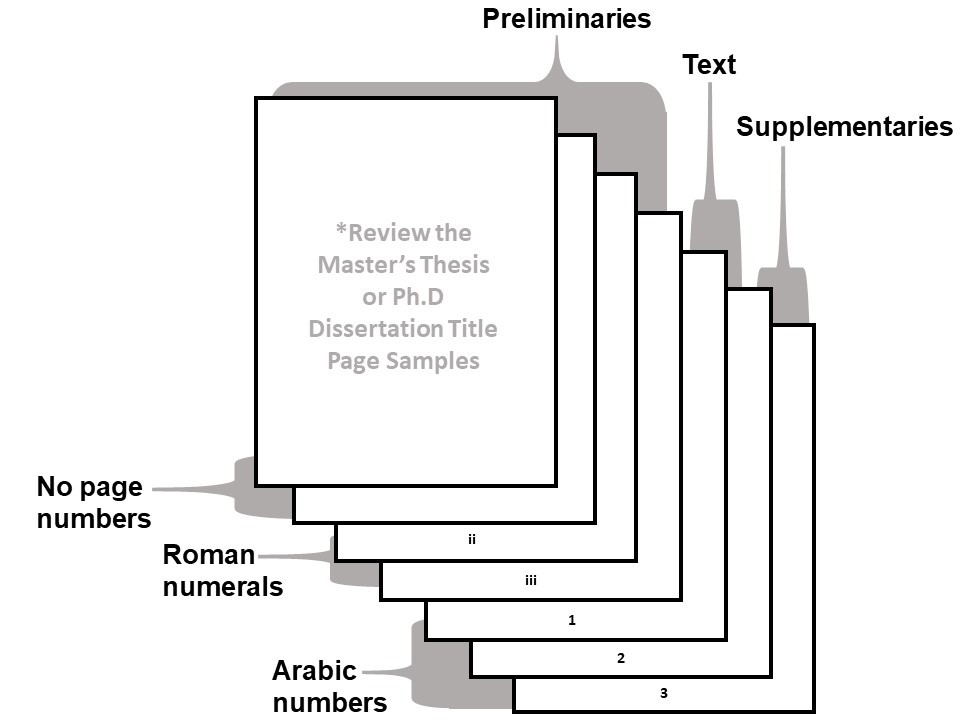

A typical thesis consists of three main parts – preliminaries, text, and supplementaries. Each part is to be organized as explained below and in the order indicated below:

1. Preliminaries:

- Title page (required)

- Copyright page (required)

- Abstract (required) only one abstract allowed

- Acknowledgments (optional) located in the Preliminary Section only

- Preface (optional)

- Autobiography (optional)

- Dedication (optional)

- Table of Contents (required)

- List of Tables (optional)

- List of Figures (optional)

- List of Plates (optional)

- List of Symbols (optional)

- List of Keywords (optional)

- Other Preliminaries (optional) such as Definition of Terms

3. Supplementaries:

- References or bibliography (optional)

- Appendices (optional)

- Glossary (optional)

- List of Abbreviations (optional)

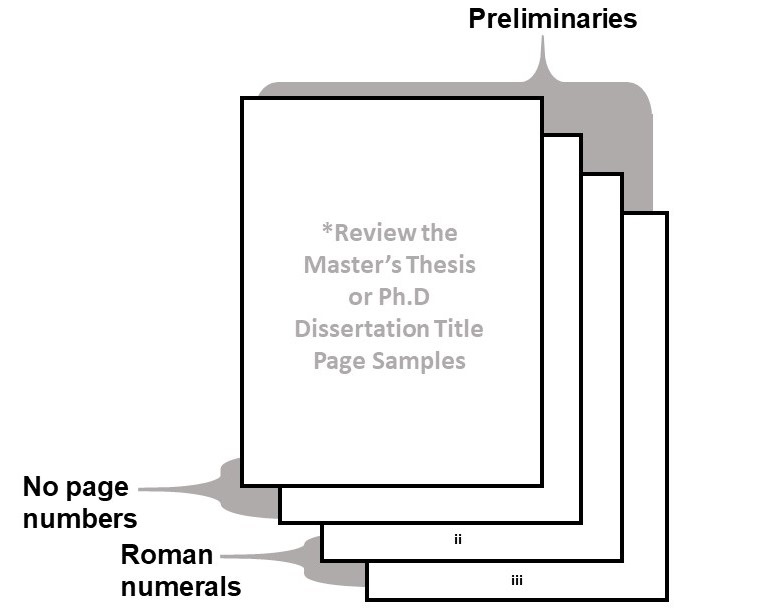

Preliminaries

These are the general requirements for all preliminary pages.

- Preliminary pages are numbered with lower case Roman numerals.

- Page numbers are ½” from the bottom of the page and centered.

- The copyright page is included in the manuscript immediately after the title page and is not assigned a page number nor counted.

- The abstract page is numbered with the Roman numeral “ii”.

- The remaining preliminary pages are arranged as listed under “Organizing and Formatting the Thesis/Dissertation” and numbered consecutively.

- Headings for all preliminary pages must be centered in all capital letters 1” from the top of the page.

- Do not bold the headings of the preliminary pages.

A sample Thesis title page pdf is available here , and a sample of a Dissertation title page pdf is available here.

Refer to the sample page as you read through the format requirements for the title page.

- Do not use bold.

- Center all text except the advisor and committee information.

The heading “ Thesis ” or “ Dissertation ” is in all capital letters, centered one inch from the top of the page.

- Your title must be in all capital letters, double spaced and centered.

- Your title on the title page must match the title on your GS30 – Thesis/Dissertation Submission Form

Submitted by block

Divide this section exactly as shown on the sample page. One blank line must separate each line of text.

- Submitted by

- School of Advanced Materials Discovery

- School of Biomedical Engineering

- Graduate Degree Program in Cell and Molecular Biology

- Graduate Degree Program in Ecology

If your department name begins with “School of”, list as:

- School of Education

- School of Music, Theatre and Dance

- School of Social Work

If you have questions about the correct name of your department or degree, consult your department. Areas of Study or specializations within a program are not listed on the Title Page.

Degree and Graduating Term block

- In partial fulfillment of the requirements

- For the Degree of

- Colorado State University

- Fort Collins, Colorado (do not abbreviate Colorado)

Committee block

- Master’s students will use the heading Master’s Committee:

- Doctoral students will use the heading Doctoral Committee:

- The Master’s Committee and Doctoral Committee headings begin at the left margin.

- One blank line separates the committee heading and the advisor section.

- One blank line separates the advisor and committee section.

- Advisor and committee member names are indented approximately half an inch from the left margin.

- Titles before or after the names of your advisor and your members are not permitted (Examples – Dr., Professor, Ph.D.).

Copyright Page

- A sample copyright page pdf is available here.

- A copyright page is required.

- A copyright page is included in the manuscript immediately after the title page.

- This page is not assigned a number nor counted.

- Center text vertically and horizontally.

- A sample abstract page pdf is available here – refer to the sample page as you read through the format requirements for the abstract.

- Only one abstract is permitted.

- The heading “ Abstract ” is in all capital letters, centered one inch from the top of the page.

- Three blank lines (single-spaced) must be between the “ Abstract ” heading and your title.

- Your title must be in all capital letters and centered.

- The title must match the title on your Title Page and the GS30 – Thesis/Dissertation Submission Form

- Three blank lines (single-spaced) must be between the title and your text.

- The text of your abstract must be double-spaced.

- The first page of the abstract is numbered with a small Roman numeral ii.

Table of Contents

- A sample Table of Contents page pdf is available.

- The heading “ Table of Contents ” is in all capital letters centered one inch from the top of the page.

- Three blank lines (single-spaced) follow the heading.

- List all parts of the document (except the title page) and the page numbers on which each part begins.

- The titles of all parts are worded exactly as they appear in the document.

- Titles and headings and the page numbers on which they begin are separated by a row of dot leaders.

- Major headings are aligned flush with the left margin.

- Page numbers are aligned flush with the right margin.

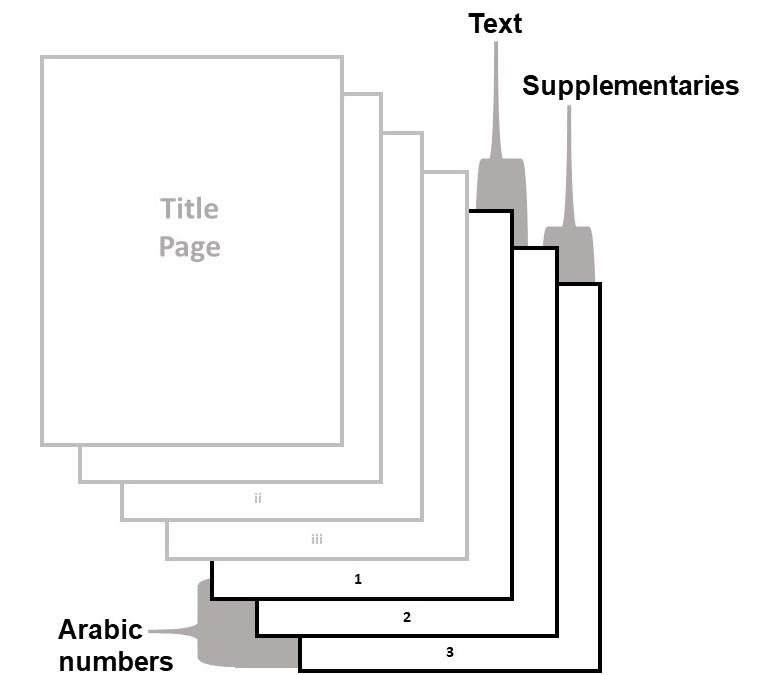

The text of a thesis features an introduction and several chapters, sections and subsections. Text may also include parenthetical references, footnotes, or references to the bibliography or endnotes.

Any references to journal publications, authors, contributions, etc. on your chapter pages or major heading pages should be listed as a footnote .

- The entire document is 8.5” x 11” (letter) size.

- Pages may be in landscape position for figures and tables that do not fit in “portrait” position.

- Choose one type style (font) and font size and use it throughout the text of your thesis. Examples: Times New Roman and Arial.

- Font sizes should be between 10 point and 12 point.

- Font color must be black.

- Hyperlinked text must be in blue. If you hyperlink more than one line of text, such as the entire table of contents, leave the text black.

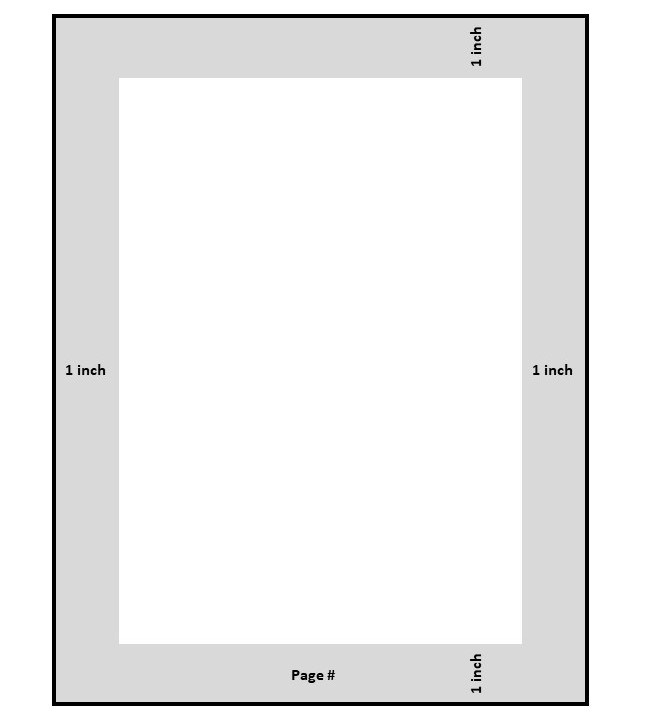

- Margins are one inch on all sides (top, bottom, left, and right).

- Always continue the text to the bottom margin except at the end of a chapter.

- Please see preliminary page requirements .

- Body and references are numbered with Arabic numerals beginning with the first page of text (numbered 1).

- Page numbers must be centered ½” from the bottom of the page.

Major Headings

- A sample page pdf for major headings and subheadings is available here.

- Use consistent style for major headings.

- Three blank lines (single-spaced) need to be between the major heading and your text.

- Each chapter is started on a new page.

- The References or Bibliography heading is a major heading and the formatting needs to match chapter headings.

Subheadings

- A sample page pdf for major headings and subheadings is available here .

- Style for subheadings is optional but the style should be consistent throughout.

- Subheadings within a chapter (or section) do not begin on a new page unless the preceding page is filled. Continue the text to the bottom of the page unless at the end of a chapter.

- Subheadings at the bottom of a page require two lines of text following the heading and at least two lines of text on the next page.

Running Head

Do not insert a running head.

When dividing paragraphs, at least two lines of text should appear at the bottom of the page and at least two lines of text on the next page.

Hyphenation

The last word on a page may not be divided. No more than three lines in succession may end with hyphens. Divide words as indicated in a standard dictionary.

- The text of the thesis is double-spaced.

- Bibliography or list of reference entries and data within large tables may be single-spaced. Footnotes should be single spaced.

- Footnotes and bibliography or list of reference entries are separated by double-spacing.

- Quoted material of more than three lines is indented and single-spaced. Quoted material that is three lines or fewer may be single-spaced for emphasis.

Poems should be double-spaced with triple-spacing between stanzas. Stanzas may be centered if lines are short.

- Consult a style manual approved by your department for samples of footnotes.

- Footnotes are numbered consecutively throughout the entire thesis.

- Footnotes appear at the bottom of the page on which the reference is made.

- Footnotes are single-spaced.

- Consult a style manual approved by your department for samples of endnotes.

- Endnotes are numbered consecutively throughout the entire thesis.

- Endnotes may be placed at the end of each chapter or following the last page of text.

- The form for an endnote is the same as a footnote. Type the heading “endnote”.

Tables and Figures

- Tables and figures should follow immediately after first mentioned in the text or on the next page.

- If they are placed on the next page, continue the text to the bottom of the preceding page.

- Do not wrap text around tables or figures. Text can go above and/or below.

- If more clarity is provided by placing tables and figures at the end of chapters or at the end of the text, this format is also acceptable.

- Tables and Figures are placed before references.

- Any diagram, drawing, graph, chart, map, photograph, or other type of illustration is presented in the thesis as a figure.

- All tables and figures must conform to margin requirements.

- Images can be resized to fit within margins

- Table captions go above tables.

- Figure captions go below figures.

- Captions must be single spaced.

Landscape Tables and Figures

- Large tables or figures can be placed on the page landscape or broadside orientation.

- Landscape tables and figures should face the right margin (unbound side).

- The top margin must be the same as on a regular page.

- Page numbers for landscape or broadside tables or figures are placed on the 11” side.

Supplementaries

These are the general requirements for all supplementary pages.

- Supplementary pages are arranged as listed under “Organizing and Formatting the Thesis/Dissertation” and numbered consecutively.

- Headings for all supplementary pages are major headings and the formatting style needs to match chapter headings.

References or Bibliography

- The References or Bibliography heading is always a major heading and the formatting style needs to match chapter headings.

- References or Bibliography are ordered after each chapter, or at the end of the text.

- References or Bibliography must start on a new page from the chapter text.

- References are aligned flush with the left margin.

- The style for references should follow the format appropriate for the field of study.

- The style used must be consistent throughout the thesis.

- Appendices are optional and used for supplementary material.

- The Appendices heading is a major heading and the formatting style needs to match chapter headings.

- As an option the appendix may be introduced with a cover page bearing only the title centered vertically and horizontally on the page. The content of the appendix then begins on the second page with the standard one inch top margin.

- Quality and format should be consistent with requirements for other parts of the thesis including margins.

- Page numbers used in the appendix must continue from the main text.

A Foreign Language Thesis

Occasionally, theses are written in languages other than English. In such cases, an English translation of the title and abstract must be included in the document.

- Submit one title page in the non-English language (no page number printed).

- Submit one title page in English (no page number printed).

- Submit one abstract in the non-English language (page number is ii).

- Submit one abstract in English (page number is numbered consecutively from previous page – example: if the last page of the abstract in the foreign language is page ii the first page of the abstract in English is numbered page iii).

Multipart Thesis

In some departments, a student may do research on two or more generally related areas which would be difficult to combine into a single well-organized thesis. The solution is the multi-part thesis.

- Each part is considered a separate unit, with its own chapters, bibliography or list of references, and appendix (optional); or it may have a combined bibliography or list of references and appendix.

- A single abstract is required.

- The pages of a multi-part thesis are numbered consecutively throughout the entire thesis, not through each part (therefore, the first page of Part II is not page 1).

- The chapter numbering begins with Chapter 1 for each part, or the chapters may be numbered consecutively.

- Pagination is consecutive throughout all parts, including numbered separation sheets between parts.

- Each part may be preceded by a separation sheet listing the appropriate number and title.

A Guide to Dissertation Planning: Tips, Tools and Templates

Dissertations are a defining piece of academic research and writing for all students. To complete such a large research project while maintaining a good work-life balance, planning and organisation is essential. In this article, we’ll outline three categories for dissertation planning including project management, note-taking and information management, alongside tools and templates for planning and researching effectively.

For both undergraduates and postgraduates, a dissertation is an important piece of academic research and writing. A large research project often has many moving parts from managing information, meetings, and data to completing a lengthy write-up with drafts and edits. Although this can feel daunting, getting ahead with effective planning and organisation will make this process easier. By implementing project management techniques and tools, you can define a research and writing workflow that allows you to work systematically. This will enable you to engage in critical thinking and deep work, rather than worrying about organisation and deadlines.

To get prepared, you can do two things: First, start your preliminary readings and research to define a topic and methodology. You can do this in summer or during the first few weeks of university but the sooner, the better. This gives you time to discuss things with your supervisor, and really choose a topic of interest. Second, begin preparing the tools and techniques you’ll be using for your research and writing workflow. You can use the preliminary research phase to test these out, and see what works for you.

Below, we’ll cover three key aspects to consider when managing your dissertation, alongside some digital tools for planning, research and writing.

The 3 Categories of Dissertation Planning

Project Management and Planning

Your dissertation is a project that requires both long and short-term planning. For long-term planning, roadmaps are useful to break your work down into sections, chapters or stages. This will give you a clear outline of the steps you need to work through to complete your dissertation in a timely manner.

Most likely, your roadmap will be a mixture of the stages in your research project and the sections of your write-up. For example, stage 1 might be defined as preliminary research and proposal writing. While stage 3 might be completing your literature review, while collecting data.

This roadmap can be supplemented by a timeline of deadlines, this is when those stages or chapters need to be completed by. Your timeline will inform your short-term plans, and define the tasks that need completing on a daily, weekly or monthly basis. This approach, using a roadmap and timeline, allows you to capture all the moving parts of your dissertation, and focus on small sub-sections at a time. A clear plan can make it easy to manage setbacks, such as data collection issues, or needing more time for editing.

Note-taking

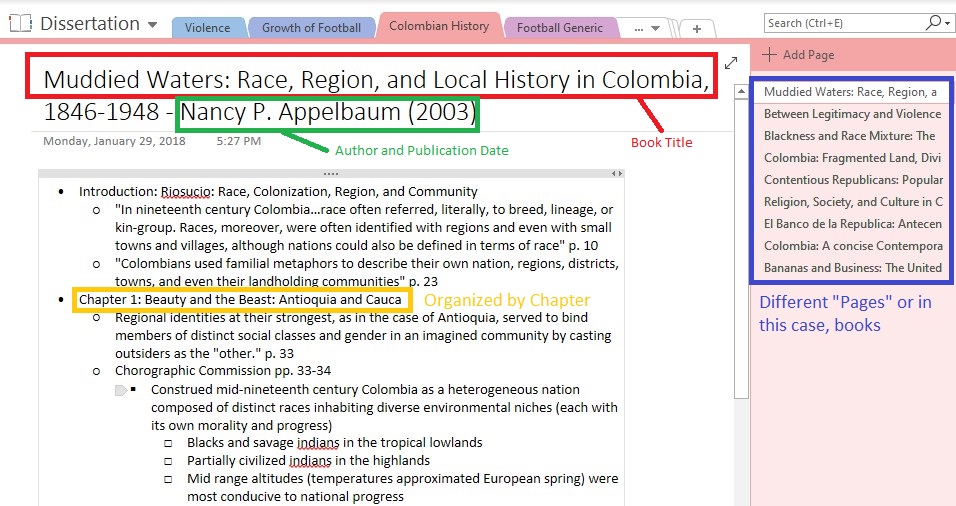

Whether you use a notebook, or digital tool, it’s ideal to have a dedicated research space for taking general notes. This might include meeting notes from supervision, important information from informational dissertation lectures, or key reminders, ideas and thoughts. It can be your go-to place for miscellaneous to-do lists, or to map out your thought processes. It’s good to have something on hand that is easy to access, and keeps your notes together in one place.

Beyond this, you’ll also need a dedicated space or system for literature and research notes. These notes are important for avoiding plagiarism, communicating your ideas, and connecting key findings together. A proper system or space can make it easier to manage this information, and find the appropriate reference material when writing. Within this system, you might also include templates or checklists, for example, a list of critical reading questions to work through when assessing a paper.

Information Management

It’s important to consider how you plan to organise your literature, important documents, and written work. Note-taking is a part of this, however, this goes a step further to carefully organise all aspects of your dissertation. For example, it’s ideal to keep track of your literature searches, the papers you’ve read, and their citations but also, your reading progress. Being able to keep track of how many passes a paper has been through, how relevant it is, or where it fits within your themes, or ideas, will provide a good foundation for writing a well-thought out dissertation.

Likewise, editing is an important part of the write-up process. You’ll have multiple drafts, revisions and feedback to consider. It’s good to have some way of keeping track of all this, to ensure all changes and edits have been completed. You might also have checklists or procedures to follow when collecting data, or working through your research. A good information management process can reduce stress, making everything easy to access and keep track of, which then allows you to focus on getting the actual work complete.

Digital Project Management and Research Tools for Dissertation Planning

Trello is a project management tool that uses boards, lists and cards to help you manage all your tasks. In a board, you can create lists, and place cards within these lists. Cards contain a range of information such as notes, checklists, and due dates. Cards and lists can be used to implement a digital kanban board system , allowing you to move cards into a ‘to-do’, ‘in progress’ or ‘complete’ list. This gives a visual representation of your progress.

This is a flexible, easy to use and versatile tool that can help with project management of your dissertation. For example, cards and lists can be used to track your literature, each card can represent a paper and lists could be 1st pass, 2nd pass, or be divided into themes. Likewise, you can use this approach to organise the various chapters or stages of your dissertation, and break down tasks in a visual way. Students have used Trello to manage academic literature reviews , daily life as an academic , and collaborate with their supervisors for feedback and revisions on their write-up.

Notion is an all-in-one note-taking and project management tool that is highly customisable. Using content blocks, pages, and databases, this tool allows you to build a workspace tailored to your needs. Databases are a key feature of Notion, this function allows you to organise and define pages using a range of properties such as tags, dates, numbers, categories and more. This database can then be displayed in a multitude of ways using different views, and filters.

For example, you can create a table with each entry being a page of meeting notes with your supervisor, you can assign a date, person, and tags to each page. You can then filter this information by date, or view it in a board format. Likewise, you can use the calendar to add deadlines, within these deadlines, you can expand the page to add information, and switch to ‘timeline’ view . This is perfect for implementing project management techniques when planning your dissertation.

Although this may sound complicated, there are many templates and resources to get you started . Notion is an ideal tool for covering all three aspects of dissertation planning from project and information management to note-taking of all kinds. Students have used Notion for literature reviews , thesis writing , long-term PhD planning , thesis management , and academic writing . The best part, these students not only share their systems, but have also created free templates to help you build your own system for research.

Asana is a project management and to-do list tool that uses boards, lists, timelines and calendars. If you’re someone who prefers using lists to organise your life and projects, Asana is ideal for you. You can use this tool to manage deadlines, reading progress, or break down your work into projects and sub-tasks. Asana can integrate with your calendar, which is perfect if you already use other calendar tools for organisation. If something like Notion is too overwhelming, using a mixture of tools with different purposes can be a more comfortable approach.

Genei is an AI-powered research tool for note-taking and literature management. Your research and reading material can be imported, and organised using projects and folders. For each file, genei produces an AI-powered summary, document outline, keyword list and overview. This tool also extracts key information such as tables, figures, and all the references mentioned. You can read through documents 70% faster but also, collect related articles by clicking on the items in the reference list. Genei can generate citations, and be used alongside other popular reference management tools, such as Zotero and Mendeley .

This tool is ideal for navigating information management and literature notes for your dissertation. You can compile notes across single documents or folders of documents using the AI-generated summaries. These notes remain linked to their original source, which removes the need for you to keep track of this information. If you find it hard to reword content, there’s also summarising and paraphrasing tools to help get you started. Genei is a great tool to use alongside project management solutions, such as Trello and Asana, and note-taking tools like Notion. You can define an efficient research and writing workflow using these range of tools, and make it easier to stay on top of your dissertation.

Do you want to achieve more with your time?

98% of users say genei saves them time and helps them work more productively. Why don’t you join them?

About genei

genei is an AI-powered research tool built to help make the work and research process more efficient. Our studies show genei can help improve reading speeds by up to 70%! Revolutionise your research process.

Articles you may like:

Find out how genei can benefit you

Dissertation Strategies

What this handout is about.

This handout suggests strategies for developing healthy writing habits during your dissertation journey. These habits can help you maintain your writing momentum, overcome anxiety and procrastination, and foster wellbeing during one of the most challenging times in graduate school.

Tackling a giant project

Because dissertations are, of course, big projects, it’s no surprise that planning, writing, and revising one can pose some challenges! It can help to think of your dissertation as an expanded version of a long essay: at the end of the day, it is simply another piece of writing. You’ve written your way this far into your degree, so you’ve got the skills! You’ll develop a great deal of expertise on your topic, but you may still be a novice with this genre and writing at this length. Remember to give yourself some grace throughout the project. As you begin, it’s helpful to consider two overarching strategies throughout the process.

First, take stock of how you learn and your own writing processes. What strategies have worked and have not worked for you? Why? What kind of learner and writer are you? Capitalize on what’s working and experiment with new strategies when something’s not working. Keep in mind that trying out new strategies can take some trial-and-error, and it’s okay if a new strategy that you try doesn’t work for you. Consider why it may not have been the best for you, and use that reflection to consider other strategies that might be helpful to you.

Second, break the project into manageable chunks. At every stage of the process, try to identify specific tasks, set small, feasible goals, and have clear, concrete strategies for achieving each goal. Small victories can help you establish and maintain the momentum you need to keep yourself going.

Below, we discuss some possible strategies to keep you moving forward in the dissertation process.

Pre-dissertation planning strategies

Get familiar with the Graduate School’s Thesis and Dissertation Resources .

Create a template that’s properly formatted. The Grad School offers workshops on formatting in Word for PC and formatting in Word for Mac . There are online templates for LaTeX users, but if you use a template, save your work where you can recover it if the template has corrruption issues.

Learn how to use a citation-manager and a synthesis matrix to keep track of all of your source information.

Skim other dissertations from your department, program, and advisor. Enlist the help of a librarian or ask your advisor for a list of recent graduates whose work you can look up. Seeing what other people have done to earn their PhD can make the project much less abstract and daunting. A concrete sense of expectations will help you envision and plan. When you know what you’ll be doing, try to find a dissertation from your department that is similar enough that you can use it as a reference model when you run into concerns about formatting, structure, level of detail, etc.

Think carefully about your committee . Ideally, you’ll be able to select a group of people who work well with you and with each other. Consult with your advisor about who might be good collaborators for your project and who might not be the best fit. Consider what classes you’ve taken and how you “vibe” with those professors or those you’ve met outside of class. Try to learn what you can about how they’ve worked with other students. Ask about feedback style, turnaround time, level of involvement, etc., and imagine how that would work for you.

Sketch out a sensible drafting order for your project. Be open to writing chapters in “the wrong order” if it makes sense to start somewhere other than the beginning. You could begin with the section that seems easiest for you to write to gain momentum.

Design a productivity alliance with your advisor . Talk with them about potential projects and a reasonable timeline. Discuss how you’ll work together to keep your work moving forward. You might discuss having a standing meeting to discuss ideas or drafts or issues (bi-weekly? monthly?), your advisor’s preferences for drafts (rough? polished?), your preferences for what you’d like feedback on (early or late drafts?), reasonable turnaround time for feedback (a week? two?), and anything else you can think of to enter the collaboration mindfully.

Design a productivity alliance with your colleagues . Dissertation writing can be lonely, but writing with friends, meeting for updates over your beverage of choice, and scheduling non-working social times can help you maintain healthy energy. See our tips on accountability strategies for ideas to support each other.

Productivity strategies

Write when you’re most productive. When do you have the most energy? Focus? Creativity? When are you most able to concentrate, either because of your body rhythms or because there are fewer demands on your time? Once you determine the hours that are most productive for you (you may need to experiment at first), try to schedule those hours for dissertation work. See the collection of time management tools and planning calendars on the Learning Center’s Tips & Tools page to help you think through the possibilities. If at all possible, plan your work schedule, errands and chores so that you reserve your productive hours for the dissertation.

Put your writing time firmly on your calendar . Guard your writing time diligently. You’ll probably be invited to do other things during your productive writing times, but do your absolute best to say no and to offer alternatives. No one would hold it against you if you said no because you’re teaching a class at that time—and you wouldn’t feel guilty about saying no. Cultivating the same hard, guilt-free boundaries around your writing time will allow you preserve the time you need to get this thing done!

Develop habits that foster balance . You’ll have to work very hard to get this dissertation finished, but you can do that without sacrificing your physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing. Think about how you can structure your work hours most efficiently so that you have time for a healthy non-work life. It can be something as small as limiting the time you spend chatting with fellow students to a few minutes instead of treating the office or lab as a space for extensive socializing. Also see above for protecting your time.

Write in spaces where you can be productive. Figure out where you work well and plan to be there during your dissertation work hours. Do you get more done on campus or at home? Do you prefer quiet and solitude, like in a library carrel? Do you prefer the buzz of background noise, like in a coffee shop? Are you aware of the UNC Libraries’ list of places to study ? If you get “stuck,” don’t be afraid to try a change of scenery. The variety may be just enough to get your brain going again.

Work where you feel comfortable . Wherever you work, make sure you have whatever lighting, furniture, and accessories you need to keep your posture and health in good order. The University Health and Safety office offers guidelines for healthy computer work . You’re more likely to spend time working in a space that doesn’t physically hurt you. Also consider how you could make your work space as inviting as possible. Some people find that it helps to have pictures of family and friends on their desk—sort of a silent “cheering section.” Some people work well with neutral colors around them, and others prefer bright colors that perk up the space. Some people like to put inspirational quotations in their workspace or encouraging notes from friends and family. You might try reconfiguring your work space to find a décor that helps you be productive.

Elicit helpful feedback from various people at various stages . You might be tempted to keep your writing to yourself until you think it’s brilliant, but you can lower the stakes tremendously if you make eliciting feedback a regular part of your writing process. Your friends can feel like a safer audience for ideas or drafts in their early stages. Someone outside your department may provide interesting perspectives from their discipline that spark your own thinking. See this handout on getting feedback for productive moments for feedback, the value of different kinds of feedback providers, and strategies for eliciting what’s most helpful to you. Make this a recurring part of your writing process. Schedule it to help you hit deadlines.

Change the writing task . When you don’t feel like writing, you can do something different or you can do something differently. Make a list of all the little things you need to do for a given section of the dissertation, no matter how small. Choose a task based on your energy level. Work on Grad School requirements: reformat margins, work on bibliography, and all that. Work on your acknowledgements. Remember all the people who have helped you and the great ideas they’ve helped you develop. You may feel more like working afterward. Write a part of your dissertation as a letter or email to a good friend who would care. Sometimes setting aside the academic prose and just writing it to a buddy can be liberating and help you get the ideas out there. You can make it sound smart later. Free-write about why you’re stuck, and perhaps even about how sick and tired you are of your dissertation/advisor/committee/etc. Venting can sometimes get you past the emotions of writer’s block and move you toward creative solutions. Open a separate document and write your thoughts on various things you’ve read. These may or may note be coherent, connected ideas, and they may or may not make it into your dissertation. They’re just notes that allow you to think things through and/or note what you want to revisit later, so it’s perfectly fine to have mistakes, weird organization, etc. Just let your mind wander on paper.

Develop habits that foster productivity and may help you develop a productive writing model for post-dissertation writing . Since dissertations are very long projects, cultivating habits that will help support your work is important. You might check out Helen Sword’s work on behavioral, artisanal, social, and emotional habits to help you get a sense of where you are in your current habits. You might try developing “rituals” of work that could help you get more done. Lighting incense, brewing a pot of a particular kind of tea, pulling out a favorite pen, and other ritualistic behaviors can signal your brain that “it is time to get down to business.” You can critically think about your work methods—not only about what you like to do, but also what actually helps you be productive. You may LOVE to listen to your favorite band while you write, for example, but if you wind up playing air guitar half the time instead of writing, it isn’t a habit worth keeping.

The point is, figure out what works for you and try to do it consistently. Your productive habits will reinforce themselves over time. If you find yourself in a situation, however, that doesn’t match your preferences, don’t let it stop you from working on your dissertation. Try to be flexible and open to experimenting. You might find some new favorites!

Motivational strategies

Schedule a regular activity with other people that involves your dissertation. Set up a coworking date with your accountability buddies so you can sit and write together. Organize a chapter swap. Make regular appointments with your advisor. Whatever you do, make sure it’s something that you’ll feel good about showing up for–and will make you feel good about showing up for others.

Try writing in sprints . Many writers have discovered that the “Pomodoro technique” (writing for 25 minutes and taking a 5 minute break) boosts their productivity by helping them set small writing goals, focus intently for short periods, and give their brains frequent rests. See how one dissertation writer describes it in this blog post on the Pomodoro technique .

Quit while you’re ahead . Sometimes it helps to stop for the day when you’re on a roll. If you’ve got a great idea that you’re developing and you know where you want to go next, write “Next, I want to introduce x, y, and z and explain how they’re related—they all have the same characteristics of 1 and 2, and that clinches my theory of Q.” Then save the file and turn off the computer, or put down the notepad. When you come back tomorrow, you will already know what to say next–and all that will be left is to say it. Hopefully, the momentum will carry you forward.

Write your dissertation in single-space . When you need a boost, double space it and be impressed with how many pages you’ve written.

Set feasible goals–and celebrate the achievements! Setting and achieving smaller, more reasonable goals ( SMART goals ) gives you success, and that success can motivate you to focus on the next small step…and the next one.

Give yourself rewards along the way . When you meet a writing goal, reward yourself with something you normally wouldn’t have or do–this can be anything that will make you feel good about your accomplishment.

Make the act of writing be its own reward . For example, if you love a particular coffee drink from your favorite shop, save it as a special drink to enjoy during your writing time.