- K-12 Education

- Higher Education

- Religious Venues

- Restaurants

- Hospitality

- Grocery & Retail

- Manufacturing

- Senior Living

Product News, Customer Stories and Updates from Rise Vision

Classroom communication: why it matters and how to improve it.

November 26 2021

Classroom communication is central to teaching; in fact, it’s almost a description of teaching. But the image of classroom communication as a teacher talking to rapt rows of students is false on many counts. That’s not what happens, and it’s not the most effective method of transmitting information.

In this post we’ll show evidence that demonstrates that communication in classrooms is most effective when it’s a two-way street , informed by mutual respect, guided by teachers and focused on understanding. We’ll address the importance of teacher-student and student — relationships. And we’ll end by looking at how new technological tools can be leveraged to accomplish much more effective classroom communication.

We’ll start with the case for classroom communication as a driver of educational and pastoral outcomes.

Classroom communication and teaching outcomes

Effective classroom communication is the basis of good educational outcomes. Studies confirm that teachers who communicate better lead classes to better grades and retention rates, while higher dropout rates are partially attributable to poor classroom communication. A positive relationship between teachers and students is both a result of better communication, and contributes to an environment that supports it: we are looking at a virtuous circle, or positive feedback loop. It’s one that can help overcome in-class impediments to learning, such as poor attitudes or fractured relationships between teachers and students, helping to create bilateral communication environments centered on the pursuit of understanding rather than expression of conflict.

Within this framework student communication is also extremely important. Good teacher communication can encourage, model and coach effective student communication, including learning about expression, persuasion, self-advocacy and questioning. Effective communicators are more effective students , and good classroom communication from teachers can help close the gap between privileged and disadvantaged students in this regard.

Classroom communication and behavioral and pastoral outcomes

Good classroom communication can improve behavior and attitude, catch social problems within the school before they begin, and act as a foundation for social and emotional learning . Students who can communicate effectively can advocate for their own social and emotional needs and are less likely to turn to negative behaviors such as acting out, attention-seeking, dissociation or ‘tuning out.’

In turn, these SEL outcomes can help drive better academic outcomes: it’s another virtuous circle. In order to break existing vicious circles, self-stoking cycles of negative actions and negative outcomes, teachers have one ‘lever’ they can pull, an action which is in their direct control: they can improve in-class communication.

Types of classroom communication

Traditional in-person classroom communication consists of verbal and non-verbal communication — spoken or written requests to students, writing on whiteboards and chalkboards, and so on. Of course, this type of communication is a two-way street and students can also talk to teachers.

It also involves non-verbal communication; to some degree, being a teacher is being an actor, performing to the class. Teachers can model desirable behavior, and their nonverbal communication, like body language, can contribute to the atmosphere of the classroom and thus to the learning environment. (Students can communicate this way too — just think of all the time a student has told you what they think of you without speaking…)

However, we’re now able to communicate more effectively in classrooms because we can use dynamic visual aids, video, and simulated activities (digitally manipulating virtual objects, for instance). We’ll get further into this later in the post. For now, this graphic shows the types of learning that are known to lead to better retention and engagement — and, superimposed, the methods of communication that characterize the traditional classroom:

We focus on precisely the forms of communication that lead to worse outcomes, because they were historically the only ones available to us. It’s time to change that. How can we encourage more effective classroom communication?

Encouraging classroom communication

Classroom communication doesn’t just happen. It’s the product of well-structured teaching and positive relationships between teachers and students, students and peers, and students and the school. When students feel safe, valued, and well-instructed, they feel like they can take part in classroom discussions, answer questions, and raise issues.

Create a safe environment

This goes beyond physical safety, though in some schools, that is a factor. It’s about feeling socially safe too. Teachers who use abrasive, shame-based techniques to punish students who raise their hands and get the answer wrong are less likely to see a forest of eager hands than those who address errors more positively (and no, of course, that doesn’t mean telling students they’re right when they’re not). But teachers aren’t the only source of power in a classroom. Students often feel intense social pressure from peers, and teachers have to find a way to override that so students can spend time learning instead of defending their reputations to their peer group. That can be achieved by teacher modeling, classroom management, and by direct personal communication between teachers and students.

Teamwork and groupwork

In Lethal Weapon, two cops with completely opposite characters are obliged to work together. They gain insight and respect, become friends, and get their work done. It’s a trope — because it happens. People who truly dislike each other won’t do a joint book report and become besties, but suspicion, mistrust and uncertainty can evaporate in the shared pursuit of common goals. Again, if there’s a positive classroom environment, students can learn from their peers that they’re good at things they didn’t realize they could do, or even that they enjoy them.

Two stars and a wish: the power of positive feedback

If all kids hear is negative feedback — don’t do that, this is wrong — what they’re hearing is: you’re wrong. It feels like personal rejection, and it leads to kids switching off, zoning out, acting up and giving up. But you can’t just tell someone who thinks two and two is five that they’re right so you don’t hurt their feelings. A part of a teacher’s job is to correct error. How can teachers communicate in a positive and affirming way but still address mistakes and problems?

One option is the ‘ two stars and a wish ’ approach, addressing two good things in a student’s work and one that could use improvement. This method can be used by teachers to offer feedback to students, or by students assessing their own or each others’ work. (If you’re brave you can ask students to apply it to you…)

This approach shouldn’t be understood as sparing students’ feelings because they can’t accept criticism; instead, it should be seen as a more effective way to communicate and modify work and behavior. In particular, when we’re seeking to establish the ‘virtuous circles’ of positive communication discussed above, positive feedback can be used to build supportive relationships with students — while teachers who rely on negative feedback more typically end up establishing conflictual student-teacher relationships .

Using digital aids to improve classroom communication

We have more options now than a chalkboard and a voice. We don’t have to wheel a big TV in to play VHS tapes. Digital displays give us access to moving images, to recorded lectures and talks, and to a range of blended communication styles — slides with embedded video, annotated speeches, and so on.

That’s a massive positive, because, as we’ve seen, sitting still and reading or listening to someone talk is one of the most ineffective means of communicating information we have. The real picture is more complex, because we can identify multiple learning styles as well as a general ‘pyramid of efficacy.’ This picture is itself complicated by the fact that almost no one has a single learning style and the most common configuration is ‘quadmodal’:

Of the four identified learning styles — Visual, Auditory, Reading/Writing, and Kinesthetic — over a third of those surveyed here preferred all four:

It’s obvious from these graphics that we should seek to present information in complex, multimodal ways to match the ways students actually learn. You can’t do that with a chalkboard. But you can do it with a digital display.

Digital technology is credited by teachers with permitting greater collaboration between students (79%), supporting greater personal expression from students (78%), and allowing students to share their work with a wider and more varied audience (96%).

Using the international PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) scores, McKinsey was able to show how different classroom technologies affected learning:

Using data projectors and internet-connected computers was associated with a bump in reading that neared or exceeded the expected results of an additional year of learning. Math and science scores might be less emphatic but they remain impressive.

The evidence from McKinsey’s survey suggests that classroom-based technology is most effective when it’s in teachers’ control, with the best results coming from internet-connected screens and screens the whole class can see. (It also shows that the effect of screen usage is most pronounced, and correlates best with long usage periods of 60 minutes or more per session, in North America.)

That fits with the results of tests and surveys showing radically increased engagement from digital signs and displays. It also fits with evidence showing that such technology is most effective when used to do things for which there is no pedagogical precedent. When students used computers to look up information on the internet, attainment rose; when they used them to perform practice drills which could as easily have used pencil and paper, attainment actually fell , suggesting that it is the learning style (kinesthetic and visual) rather than the technological substrate that matters.

To bring more effective communication into the classroom, teachers should focus on pedagogical logic: why does this help students learn? Communication is a two-way street, and teaching staff should be looking for levers they can pull to help develop a ‘virtuous circle’ of appropriate and learning-centered teacher-student communication. Technology, especially in the form of internet-connected digital displays , can help with this by offering entirely novel pedagogical routes and permitting the formation of new learning relationships guided by teaching staff.

Image Credits:

More from our blog.

Best Knowledge Sharing Tools

Ways to Communicate With Millennials in the Workplace

Hybrid Meetings: Enhancing Virtual Collaborations in Conference Rooms

Keep your displays interesting - pick new templates every week.

Every week, we send Template recommendations that will make you look great and improve your audience experience. And the best part, they save up to 16 hours of content creation time every week.

Not convinced? Check out the email we sent last week .

Digital signage doesn’t have to be difficult. We make it easy or your money back. 30 days risk-free.

1-866-770-1150 • [email protected] • Help Center

- How Rise Vision Works

- Weekly Playbook

- Press Releases

- Digital Menu Boards

- Emergency Alerts

- Digital Directory

- Digital Donor Wall

- Digital Hall of Fame

- Social Media Wall

- Digital Reader Board

- Our Mission

Teaching Communication Skills

A framework for exploring with students what good communication looks like and for helping them develop the necessary skills.

Picture a great speaker—a famous politician, maybe, or a poet or performer. Maybe you’re thinking of someone speaking to an audience in a high-stakes scenario.

Most of the talk that happens in your classroom does not look like this. In small group or whole class discussions, students are more concerned with learning than with audience: Their talking is exploratory rather than presentational.

This is one of the challenges of teaching communication skills: What “good” looks like depends on the context. The skills needed to speak in front of an audience and hold a room are different from those needed to solve a problem or engage in a group discussion. If what you’re trying to teach is slippery and hard to define, how can you go about teaching it?

A Framework for Looking at Communication

Academics at Cambridge University and teachers at my school created a framework for describing good communication skills in different contexts. It divides these skills into four distinct but interlinked strands:

- Physical: How a speaker uses their body language, facial expressions, and voice.

- Linguistic: The speaker’s use of language, including their understanding of formality and rhetorical devices.

- Cognitive: The content of what a speaker says and their ability to build on, challenge, question, and summarize others’ ideas.

- Social and emotional: How well a speaker listens, includes others, and responds to their audience.

This framework provides a starting point for working out what exactly constitutes great communication in different situations. But how can a teacher create a classroom culture that values and actively develops students’ communication skills?

Start by talking explicitly with your students about what good communication looks like for a given context. While there are plenty of examples of great public speakers to hold up and analyze, it can be harder to find examples of excellent exploratory discussions. One fun way to explore what makes a great discussion is to film a group of teachers having a terrible discussion (fidgeting, going off topic, one person dominating and making irrelevant points while others aren’t listening) and then look at a really strong example (listening, building on or challenging each other’s ideas, working together to reach consensus). Comparing the two discussions, you and your students can start to build a shared understanding of what “good” looks like.

You can use this understanding to write, with your students, a set of discussion guidelines, including things like:

- We build on, challenge, summarize, clarify and probe each other’s ideas

- We are prepared to change our minds.

- We include everyone by inviting them into the discussion.

Creating guidelines with your students provides an opportunity to establish a positive culture for talk. It also enables you to dispel any negative, perhaps unspoken, misconceptions students may have about discussion, such as: “She always does well on tests, so I’ll just say what she says,” or “He’s my friend, so I shouldn’t disagree with him.”

Of course, creating discussion guidelines alone is unlikely to transform talk in your classroom—your students will need each skill to be explicitly taught, modeled, and praised, at least initially. You can establish the culture by saying things like, “I listened to what X said, and actually it’s made me think differently—I’m starting to change my mind,” or, “I’m not totally sure yet, but I think _____. What do you think?”

You’ll also need to explicitly and deliberately teach many communication skills. Take for example the skills involved in summarizing a discussion. Your students need to know what a summary is. They may also need some sentence stems to scaffold summarizing a discussion (“The main points you raised were...,” “In summary, we talked about...”). They may also need practice judging when it’s useful to summarize a discussion.

Over time, you can work on each guideline in turn and strengthen your students’ understanding of it. Continually returning to your discussion guidelines provides an opportunity for students to reflect on and talk about talking—to engage metacognitively in the learning process.

Supporting Quiet Students

For quieter students, increasing the amount of talk in your classroom may feel daunting. Ensuring that you have a guideline that requires all students to be included in discussions gives more confident students a responsibility to ensure that everyone is heard from. Again, you may need to explicitly teach what it means to invite someone into a discussion: developing an awareness of who has and hasn’t spoken yet, and turning your body to face someone who has been quiet and saying their name or asking them a question.

You can also support quieter students by providing them with scaffolds such as sentence stems, or by giving them a specific role, such as summarizer, that provides a clear route into discussion. Increasing the number of low-stakes opportunities to speak, in a supportive environment, may give some quieter students the confidence they need to find their voice.

If a student isn’t speaking as frequently as their peers, you needn’t assume that they aren’t benefiting from the increase in talking in your classroom. It’s likely that they’re listening carefully and taking in what is being said, so it’s vital to praise and celebrate listening skills as well as speaking skills.

Ultimately, learning is a process of sharing, engaging with, and responding to new and different ideas. As Professor Frank Hardman has said, talk is “the most powerful tool of communication in the classroom, and it’s fundamentally central to the acts of teaching and learning.”

- Connect with us:

- X (Twitter)

Importance of communication education

- Author By Elizabeth Lynch and Mitch Combs

- November 7, 2017

Where has digital communication not affected our lives? New business and career opportunities have opened up in companies in all industries to hire staff for communication and other jobs that were unimaginable.

Professor Cheri Simonds, Ph.D.

Illinois State University professor Cheri Simonds has played an instrumental role in improving basic communication education for the past 21 years in schools around the country.

“I’m committed to improving the communication discipline one basic course at a time,” said Simonds. Her mission has taken on added importance because communication is an integral part of our personal, professional, and social lives. Because effective communication is required in every field, high-quality communication programs are more significant than ever before.

In fact, the communication field’s value is truly on the rise for the long term, thanks in large part to the increasing integration of digital media with other, traditional media. To meet this demand, communication degrees experienced a 44 percent increase from 1987 to 2015, according to the National Communication Association’s report Communication Is Only Humanities Discipline to Experience Bachelor’s Degree Completion Growth . It is also the only discipline to experience an increase during that time. The same increase can be found in Inside Higher Ed’s report Humanities Majors Drop .

However, despite the documented growth, the importance of communication studies in public policy is often overlooked. For example, Illinois legislators fail to differentiate between communication and English studies.

“Communication and composition are both integral to a foundational educational experience,” said Simonds, “but they must be treated uniquely because they are different even though they do intersect at times.”

The importance of proper communication education begins in students’ developmental years. Common Core standards require that students develop speaking and listening skills throughout their early education. This is to lay a foundational understanding to prepare students for college and their future careers.

Measuring students’ improvement over time is the most efficient way to evaluate the effectiveness of a communication course. Improvements are measured through a digital media platform that tracks students’ improvements overtime.

“We created a systematic speech evaluation training program so that we made sure instructors in the program evaluated student work fairly and consistently every time, instructors could communicate assignment expectations to students well, and that students would understand what they needed to do to earn a certain grade on the presentation,” said Simonds. Eventually, the platform will be made available to other programs within Illinois State as well as other educational institutions.

It is important to re-emphasize that English and communication are not one in the same. Preparing students to succeed in communication and composition vastly differs from English studies. “Many general education programs identify both written and oral communication as essential learning outcomes. Because general education is designed to provide broad exposure to multiples disciplines and serve as a foundation for important intellectual skills, it is important that students receive this instruction across disciplines. This begins with their composition and communication instruction,” said Simonds.

Extensive research gives Simonds the evidence she needs to advocate for the importance of communication studies.

Simonds applies her teaching experiences for developing research. “I have the best job of all, because I research what I do every day. My research is on teaching and my teaching informed by my research,” said Simonds.

Through research, Simonds tailors her training program to fit the evolving needs of national communication programs. The research ensures the effectiveness of the communication education program via assessment efforts. Additionally, Simonds looks for effective tools to enhance the teacher training program. As such, she studies the best methods for teaching communication as well as the best ways to use communication to teach.

Simonds traveled to four regional areas for basic course director training in her last sabbatical in fall 2014. Illinois State University was the first to implement basic course director training. The desired outcome was to eliminate the “revolving door,” meaning those who lack the competence and desire to effectively carry out their role. “I want my legacy to be that I nurtured a pipeline of future basic course directors that are confident, competent and passionate about their role,” said Simonds.

The next project that Simonds is undertaking is through the National Communication Association. She and many other communication professionals are part of a nationwide funded social science research council to create common competencies for oral communication.

The council will create assessment instruments and apply an evaluation assessment within the school to publish nationally. Any school from across the nation can use their assessment to advocate that their course is relevant in general education. The goal is to not compete against other schools, but rather, to support one another in growing the communication education field.

Reshaping institutions’ approaches to basic communication and communication education have produced remarkable results for Simonds. It is through these efforts that Simonds is able to assist other institutions in saving their communication programs by proving their value.

Related Articles

- Privacy Statement

- Appropriate Use Policy

- Accessibility Resources

Communication in the Field of Education

- First Online: 19 August 2017

Cite this chapter

- Christos Saitis 3 &

- Anna Saiti 4

444 Accesses

Communication exists within each school process and is one of the most important and difficult issues that the school head has to manage. This is because communication is the tool through which (a) information can be transferred and hence decision-making is facilitated, (b) it is fundamental for the implementation of decisions and (c) it can foster good relations and team spirit among the school members.

A solid understanding of communication is essential for the functioning of the school unit since it is a social phenomenon and a fundamental element of interrelationships among members of a formal organization.

This chapter:

Develops the meaning and significance of communication within a working environment

Briefly presents the communication process and the preconditions (e.g. ability of a person to communicate at an appropriate cognitive level) that are necessary for effective and constructive communication channels in order for communication within a school to be maintained at a functional level

Analyses the types of communication and the parameters for various message types by referring to examples about the way of which a school head should manage difficult situations

Examines the appropriate conditions for good human relations among school members

Presents case studies relating to real school situations

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Androulakis, E., & Stamatis, P. (2009). Communication style of educators during the meeting of teachers council: A case study. Epistimoniko Vima, 10 , 107–118. (in Greek).

Google Scholar

Armstrong, M., & Baron, A. (1998). Performance management: The new realities . London: CIPD.

Armstrong, M. (2006). A handbook of management techniques (Rev. 3rd ed.). London: Kogan Page.

Bagshaw, D., Lepp, M., & Zorn, C. R. (2007). International research collaboration: Building teams and managing conflicts. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 24 (4), 433–446.

Article Google Scholar

Balay, R. (2006). Conflict management strategies of administrators and teachers. Asian Journal of Management Cases, 3 (1), 5–24.

Bedeian, A. (1998). Management (2nd ed.). New York: The Dryden Press.

Boardman, S. K., & Horowitz, S. V. (1994). Constructive conflict management and social problems: An introduction. Journal of Social Issues, 50 (1), 1–12.

Bouradas, D. (2001). Management . Athens, Greece: Benou Publications. (in Greek).

Bouradas, D. (2013). Talking to my children for a real successful perspective and professional life . Athens, Greece: Patakis Publishing. (in Greek).

Bush, T. (2008). From management to leadership: Semantic or meaningful change? Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 36 (2), 271–288.

Cherniss, G. (2001). Emotional intelligence and organizational effectiveness. In G. Cherniss & D. Goleman (Eds.), The emotionally intelligent workplace (pp. 3–12). San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Click, P. (1981). Administration of schools for young children . New York: Delmar Publishers.

Corwin, R. G. (1966). Staff conflicts in the public schools . Columbus, OH: Educational Resources Information Center, Ohio State University.

Dean, J. (1995). Managing the primary school (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

De Lima, J. A. (2001). Forgetting about friendship: Using conflict in teacher communities as a catalyst for school change. Journal of Educational Change, 2 (2), 97–122.

Difonzo, N., Bordia, P., & Rosnow, R. (1994). Reining in rumors. Organizational Dynamics, 23 (1), 57–60.

Dobelli, R. (2013). The art of thinking clearly . London: Sceptre.

Dubrin, A. J. (1997). Essentials of management (14th ed.). London: SouthWestern, College Dublishing.

Eckman, E. W. (2004). Similarities and differences in role conflict, role commitment and job satisfaction for female and male high school principals. Educational Administration Quarterly, 40 (3), 366–387.

Everard, K. B., Morris, G., & Wilson, I. (2004). Effective school management (4th ed.). London: Paul Chapman Publication.

Goleman, D. (2001). Emotionally intelligence: Issues in paradigm building. In G. Cherniss & D. Goleman (Eds.), The emotionally intelligent workplace (pp. 13–26). San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Goman, C. K. (2011). The silent language of leaders. How body language can help or hurt – How you lead . San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Hatzipanteli, P. (1999). Human resource management . Athens, Greece: Metaihmio Publishing. (in Greek).

Hatzichristou, C. (2004). Promotion of psychological health and learning: Social and emotional school performance (Vol. 1, 4 and 5). Athens, Greece: Dardanos Publishing. (in Greek).

Henkin, A. B., Cistone, P. J., & Dee, J. R. (2000). Conflict management strategies of principals in site-based managed schools. Journal of Educational Administration, 38 (2), 142–158.

Henkin, A. B., & Holliman, S. L. (2009). Urban teacher commitment: Exploring associations with organisational conflicts, support for innovation and participation. Urban Education, 44 (2), 160–180.

Kalogirou, K. (2000). Human relations in the workplace . Athens, Greece: Stamoulis Publishing. (in Greek).

Kazazi, M. (2002). Human relations and communication (2nd ed.). Athens, Greece: Ellin Publishing. (in Greek).

Kontakos, A., & Stamatis, P. I. (2002). Principles of healthy communication in kindergarten. In N. Polemikos, M. Kaila, & F. Kalavasis (Eds.), Deviations in the field of education , Series of books entitled educational, family and political psychopathology (pp. 350–386). Athens, Greece: Atrapos Publications. (in Greek).

Koontz, H., O’Donnell, C., & Weihrich, H. (1982). Management (7th ed.). London: McGraw Hill International Book Company.

Malikiosi-Loizou, M., & Sponda, E. (2002). The impact of education on communication skills and the interaction of teacher. In N. Polemikos & A. Kontakos (Eds.), Non-verbal communication (2nd ed., pp. 163–186). Athens, Greece: Ellinika Grammata Publications. (in Greek).

Naylor, J. (1999). Management . London: Pitman Publishing.

Novak, D. (2007). The education of an accidental CEO. Lessons learned from the trailer park to the corner office . New York: Crown Business.

Panteli, S. (2010). Secrets of team success . Athens, Greece: Kritiki Publishing. (in Greek).

Payne, J., & Payne, S. (1999). Management: How to do it . Hampshire, England: Gower Publishing.

Rahim, M. A. (2001). Managing conflicts in organizations (3rd ed.). London: Quorum Books.

Ritchie, R., & Woods, P. A. (2007). Degrees of distribution: Towards an understanding of variations in the nature of distributed leadership in schools. School Leadership and Management, 27 (4), 363–381.

Robbins, S. P., & Judge, T. A. (2012). Organizational behavior (13th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Saiti, A. (2015). Conflicts in schools, conflict management styles and the role of the school leader: A study among Greek primary school educators. Educational Management, Administration and Leadership, 43 (4), 582–609.

Shen, J., Leslie, J. M., Spybrook, J. K., & Ma, X. (2012). Are principal background and school processes related to teacher job satisfaction? A multilevel study using schools and staffing survey 2003-2004. American Educational Research Journal, 49 (2), 200–230.

Sisk, H., & Williams, J. (1981). Management and organization (4th ed.). Cincinnati, OH: Thomson South – Western.

Somech, A. (2008). Managing conflict in school teams: The impact of task and goal interdependence on conflict management and team effectiveness. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44 (3), 359–390.

Stamatis, P. I. (2012). Communication in the educational and administration process . Athens, Greece: Diadrasi Publishing. (in Greek).

Thorndike, E. I. (1911). Animal intelligence . New York: Macmillan.

Tjosvold, D. (1998). The cooperative and competitive goal approach to conflict: Accomplishments and challenges. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 47 (3), 285–313.

Tjosvold, D., & Hui, C. (2001). Leadership in China: Recent studies on relationship building. Advances in Global Leadership, 2 (2), 127–151.

Tobin, T. (2001). Organizational determinants of violence in the workplace. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 6 (1), 91–102.

Tourish, D., & Hargie, O. (2004). Motivating critical upward communication: A key challenge for management decision making. In D. Tourish & O. Hargie (Eds.), Key issues in organizational communication (pp. 188–204). London: Routledge Publication.

Tourish, D., & Robson, P. (2003). Critical upward feedback in organisations: Processes, problems and implications for communication management. Journal of Communication Management, 8 (2), 150–167.

Tourish, D., & Robson, P. (2006). Sense making and the distortion of critical upward communication in organisations. Journal of Management Studies, 43 (4), 711–730.

Walhstrom, K. L., & Louis, K. S. (2008). How teachers experience principal leadership: The role of professional community, trust, efficacy and shared responsibility. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44 (4), 458–495.

Williams, J. E., & Garza, L. (2006). A case study in change and conflict: The Dallas independent school district. Urban Education, 41 (5), 459–481.

Zavlanos, M. (1998). Management . Athens, Greece: Ellin Publishing. (in Greek).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Primary Education, School of education, University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Christos Saitis

Department of Home Economics & Ecology, School of Environment, Geography & Applied Economics, Harokopio University, Athens, Greece

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Saitis, C., Saiti, A. (2018). Communication in the Field of Education. In: Initiation of Educators into Educational Management Secrets. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47277-5_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47277-5_5

Published : 19 August 2017

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-47276-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-47277-5

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.4 The Importance of Communication

Communication skills are essential in all areas of life.

Communication is used in virtually all aspects of everyday life. In order to explore how communication is integrated into all parts of our lives, let us divide up our lives into four spheres: academic, professional, personal, and civic . The se spheres overlap a n d influence one another . After all, our personal experience is brought into the classroom, much of what goes on in a classroom is present in our professional and personal environments, and the classroom has long been seen as a place to foster personal growth and prepare students to become active and responsible members of society .

Academic Success

You will bring your current communication-related knowledge, skills, and abilities to the classroom. Aside from wanting to earn a good grade, you may also be genuinely interested in becoming a better communicator. Research shows that even people who are poor communicators can improve their verbal, nonverbal, and interpersonal communication skills by taking communication courses ( Zabava & Wolvin , 1993). Communication skills are also tied to academic success. Poor listening skills have been shown to contribute significantly to failure in a person’s first year of college. Also, students who take communication courses report having more confidence in their communication abilities, and these students have higher grade point averages and are less likely to drop out of school. Much of what we do in a classroom, whether it is the interpersonal interactions with our classmates and instructor, individual or group presentations, writing assignments, asking questions, or listening, can be used to build or add to a foundation of good communication skills and knowledge that can carry through t o professional, personal, and civic contexts .

Professional Skills

The Corporate Rec r uiters Survey Report ( Graduate Management Admission Council, 2017 , p. 50 ) found that employers in h ealth c are and pharmacy, technology, nonprofit and government, and products and services industries list oral, written, listening, and presentation communication skills in their top five skills sought for midlevel positions. Adaptability was also ranked in the top five in three out of the four industries— the ability to be adaptable can be the result of a person’s ability to perceive, interpret, and share information. The survey also found that the need for teamwork skills is growing in deman d. The ability to follow a leader, delegation skills, valuing the op inions of others, cross-cultural sensitivity, and adaptability were listed as t eamwork ski lls , and these skills can also be the result of one’s communication skills.

Table 1.1. Top Five Skills Employers Seek, in Order of Required Proficiency, by Industry

Note: Adapted from Corporate Recruiters Survey Report 2017 , by the Graduate Management Admission Council, p. 50. https://www.mba.com/-/media/files/gmac/research/employment-outlook/2017-gmac-corporate-recruiters-web-release.pdf?la=en

Desired communication skills vary from career to career, but again, the academic sphere provides a foundation onto which you can build communication skills specific to your professional role or field of study. Poor listening skills, lack of conciseness, and the inability to give constructive feedback have been identified as potential communication challenges in professional contexts. Despite the well-documented need for communication skills in the professional world, many students still resist engaging in communication classes. Perhaps people think they already have good communication skills or can improve their skills on their own. Although either of these may be true for some, studying communication can only help.

Personal Communication Skills

Many students know from personal experience and from the prevalence of communication counselling on television talk shows and in self-help books that communication forms, maintains, and ends our interpersonal relationships, but they do not know the extent to which that occurs. Although we learn from experience, until we learn specific vocabulary and develop a foundational knowledge of communication concepts and theories, we do not have the necessary tools to make sense of these experiences. Just having a vocabulary to name the communication phenomena in our lives increases our ability to consciously alter our communication to achieve our goals, avoid miscommunication, and analyze and learn from our inevitable mistakes.

As mentioned earlier in the chapter, communication is required for us to meet our personal physical , instrumental , relational , and identity needs.

- Physical needs are needs that keep our bodies and minds functioning.

- Instrumental needs are needs that help us get things done in our day-to-day lives and achieve short- and long-term goals.

- Relational needs are needs that help us maintain social bonds and interpersonal relationships.

- Identity needs include our need to present ourselves to others and be thought of in particular and desired ways.

Civic Engagement

Civic engagement refers to working to make a difference in our communities by improving the quality of life of community members; raising awareness about social, cultural, or political issues (Image 1.10); or participating in a wide variety of political and nonpolitical processes (Ehrlich, 2000). The civic part of our lives is developed through engagement with the decision making that goes on in our society at small-group, local, state, regional, national, and international levels. Such involvement ranges from serving on a neighbourhood advisory board to sending an email to a political representative. Discussions and decisions that affect our communities happen around us all the time, but it takes time and effort to become part of that process. Communication scholars have been aware of the connections between communication and a person’s civic engagement or citizenship for thousands of years. Aristotle, who wrote the first and most influential comprehensive book on communication 2,400 years ago, taught that it is through our voice, our ability to communicate, that we engage with the world around us and participate in our society .

Diversity in Communication

Communication is the sharing of understanding and meaning (Pearson & Nelson, 2000), but what is intercultural communication ? If you answered “the sharing of understanding and meaning across cultures,” you’d be close, but what is a culture ? Culture is defined by more than ethnicity, race, or geography. A culture can exist wherever there is a group of people with shared beliefs, attitudes, values, and traditions. Multiple factors can shape a culture, including but not limited to age, gender, ethnicity, race, geography, workplace settings, family, abilities, and interests. According to Rogers and Steinfatt (1999), intercultural communication is the exchange of information among individuals who are “unalike culturally.” Let’s explore what intercultural communication can look like.

A culture’s beliefs, attitudes, values, and traditions are represented and expressed by the behaviours of its members. The language we use, the holidays we celebrate, the clothes we wear, the movies we watch, or the video games we play are just some of the ways we express our culture. Environment also shapes a culture, and a culture can shape the environment. For example, a person can grow up in a mountainous region and value the environment. If the person moves to a beach town, they may display pictures of their favourite mountains and participate in an outdoor club to continue to express and engage in their culture. Culture also involves the psychological aspects of our expectations of the communication context. For example, if we are raised in a culture where males speak while females are expected to remain silent, the context of the communication interaction governs behaviour, itself a representation of culture. From the choice of words (message), to how we communicate (in person or by email), to how we acknowledge understanding with a nod or a glance (nonverbal feedback), to the internal and external interference, all aspects of communication are influenced by culture.

Can there be intercultural communication within a culture? If all communication is intercultural, then the answer would be yes, but we still have to prove our case. Imagine a three-generation family living in one household. This family is a culture, but let’s look a bit closer. The grandparents may represent another time and different values from the grandchildren. The parents may have a different level of education and pursue different careers from the grandparents. The schooling the children receive may prepare them for yet other careers. From music to food preferences to how work is done may vary across time—singer Elvis Presley may seem like ancient history to the children. The communication across generations represents intercultural communication, even if only to a limited degree.

Another example is student culture. Let’s consider what other cultures likely impact the student culture at a school, university, or college. A group of students are likely all similar in age and educational level (Image 1.11). Do gender and the societal expectations of roles influence their interactions? Of course. And so we see that, among these students, the boys and girls not only communicate in distinct ways, but not all boys and girls are the same. A group of siblings may have common characteristics, but they will still have differences, and these differences contribute to intercultural communication. We are each shaped by our upbringing, and it influences our worldview, what we value, and how we interact with each other. We create culture, and it creates us.

If intercultural communication is the exchange of information among individuals who are “unalike culturally,” after reflecting on our discussion and its implications, you may arrive at the idea that ultimately we are each “a culture of one”—we are simultaneously a part of community and its culture(s) and separate from it in the unique combination that represents us as an individual. All of us are separated by a matter of degrees from each other even if we were raised on the same street, have parents of similar educational background and profession, and have many other things in common.

Communication with yourself is called intrapersonal communication , and it may also be intracultural, as you may only represent one culture, but most people belong to many groups, each with their own culture. Within our imaginary intergenerational home, how many cultures do you think we might find? If we only consider the parents, and consider work one culture and family another, we now have two. If we were to look more closely, we would find many more groups, and the complexity would grow exponentially. Does a conversation with yourself ever involve competing goals, objectives, needs, wants, or values? How did you learn of those goals or values? Through communication within and among individuals, they themselves are representative of many cultures. We struggle with the demands of each group and their expectations, and could consider this internal struggle intercultural conflict, or simply intercultural communication.

Culture is part of the very fabric of our thought, and we cannot separate ourselves from it, even when we leave home, defining ourselves anew in work and achievement. Every business or organization has a culture, and within what may be considered a global culture, there are many subcultures or co-cultures. For example, consider the difference between the sales and accounting departments in a corporation—we can quickly see two distinct groups, each with their own symbols, vocabulary, and values. Within each group there may also be smaller groups, and each member of every department comes from a distinct background that in itself influences behaviour and interaction.

Intercultural communication is a part of our everyday lives and occurs interpersonally (with others) and intrapersonally (within ourselves). Intercultural communication competency is rooted in understanding the cultures around us and adapting our communication to establish, maintain, and grow positive intercultural relationships.

Relating Theory to Real Life

Consider the definition of culture:

- What cultures do you feel you are a part of? What beliefs, attitudes, values, traditions, and behaviours represent your cultures?

- What cultures do you see within your own family?

- What cultural groups will you encounter in your future professional role?

- What will you need to learn to be a competent intercultural communicator in the workplace?

Ethical Communication in the Workplace

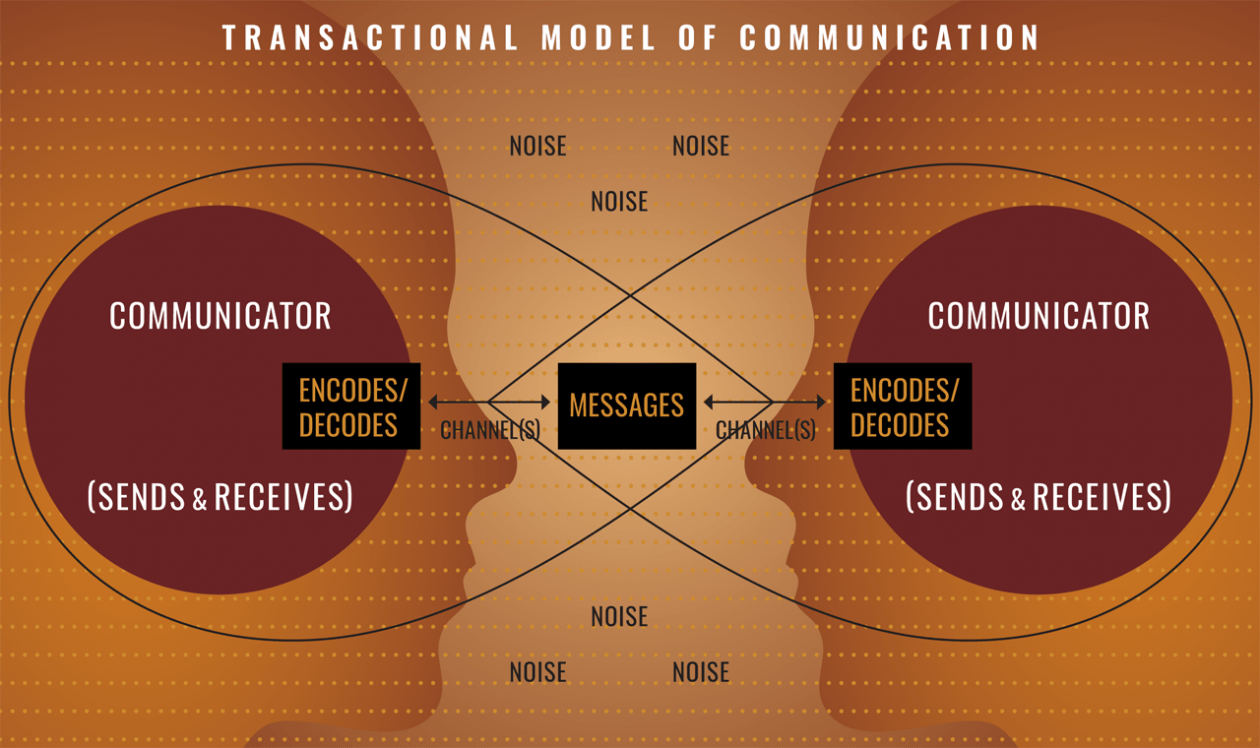

As demonstrated by the communication models presented earlier in this chapter, when we communicate, there is an immediate impact on others. This means communication has broad ethical implications. Not only do we need to learn how to communicate, but we also need to become ethical communicators by learning how to communicate the “right” way. But what does that look like?

Communication ethics deals with the process of negotiating and reflecting on our actions and communication regarding what we believe to be right and wrong. For example, we may make the choice to communicate our opinions about education to others. We would undergo a process of negotiating the ethics of this decision, such as to whom is it okay to communicate our opinions? When is it appropriate to tell others about our personal opinions? What details about our opinions is it okay to share? What is the right method for sharing our opinion? In communication ethics, we are more concerned with the decisions people make about communicating what is right and wrong than the systems, philosophies, or religions that inform those decisions. Much of ethics is a grey area. Although we talk about making decisions in terms of what is right and what is wrong, the choice is rarely that simple. Aristotle said that we should act “to the right extent, at the right time, with the right motive, and in the right way.” This quote connects to communication competence, which focuses on communicating effectively and appropriately.

We all make choices daily that are more ethical or less ethical, and we may confidently make a decision only to learn later that it wasn’t the most ethical option. In any given situation, multiple options may seem appropriate, but we can only choose one. If, in a situation, we make a decision and reflect on it, and then realize we could have made a more ethical choice, does that make us a bad person? Although many behaviours can be easily labelled as ethical or unethical, communication isn’t always as clear. Physically assaulting someone is generally thought of as unethical and illegal, but many instances of hurtful speech, or even what some would consider hate speech, have been protected as free speech. This shows the complicated relationship between protected speech, ethical speech, and the law. In some cases, people see it as their ethical duty to communicate information that they feel is in the public’s best interest. The people behind WikiLeaks, for example, have released thousands of classified documents related to wars, intelligence gathering, and diplomatic communication. WikiLeaks claims that exposing this information forces politicians and leaders to be accountable and keeps the public informed, but government officials claim that the release of the information should be considered a criminal act. Both parties consider their own communication ethical and the other’s communication unethical, so who is right?

Since many of the choices we make when it comes to ethics are situational, contextual, and personal, various professional fields have developed codes of ethics to help guide members through areas that might otherwise be grey or uncertain. A profession’s code of ethics describes what ethical behaviours , including communication, are expected of any member of the profession . Table 1.2 below lists a few examples of professions and which communication behaviours are considered ethical and expected as described in that profession’s code of ethics . Looking across different professions, we can see that ethical communication is expected in all service areas and that communication skills are key to meeting professional standards.

Table 1.2. Professional Organizations and Ethical Communication Expectation

- What situations might arise in your future professional role that will require you to communicate ethically?

- Why is it important for you , others, your workplace, and your community to be co nfident in communicating ethically ?

Dynamic Communication Skills Are Needed in Current Workplaces

Communication is key to your success in your current workplace.

Your current ability to communicate comes from past experience, which can be an effective teacher. Now is the time to examine your current skillset and compare it to current workplace needs and skills that have been proven necessary when working on teams. “Great teams are distinguished from good teams by how effectively they communicate. Great team communication is more than the words that are said or written. Power is leveraged by the team’s ability to actively listen, clarify, understand, and live by the principle that ‘everything communicates.’ The actions, the tone, the gestures, the infrastructure, the environment, and the things that are not done or said speak and inform just as loudly as words” (O’Rourke & Yarbrough, 2008).

Workplace environments have evolved. An article in the Harvard Business Review states that current workplace teams are more “diverse, dispersed, digital, and dynamic (with frequent changes in membership). But while teams face new hurdles, their success still hinges on a core set of fundamentals for group collaboration” (Haas & Mortensen, 2016). Haas and Mortensen further describe four conditions that need to be established for effective collaboration: compelling direction (when a team establishes explicit goals), strong structure (the team has the right mix of members, and the right processes and norms in place to guide behaviour), supportive context (the team has a reward system, an information system, and an educational system in place to enable progress), and a shared mindset (when a team develops a common identity and understanding). Communication is central to establishing all four conditions. Effective teams and groups in current workplace environments need effective communication. Now is the time to consider what communication skills you have and which ones you need to grow to effectively contribute to your future team.

Communication Merges You and Them

When we join a workplace team, communication is a non-negotiable skill in a complex environment. Being able to communicate allows us to share a part of ourselves, connect with others, and meet our needs on a team. Being unable to communicate might mean losing, hiding, or minimizing a part of yourself. Sharing with others feels vulnerable. For some, this may be a positive challenge, whereas for others it may be discouraging, but in all cases, your ability to communicate is central to your expression of self.

On the other side of the coin, your communication skills help you understand others on a team—not just their words, but also their tone of voice, their nonverbal gestures, and the format of their written documents provide you with clues about who they are and what their values and priorities may be. Expressing yourself and understanding others are key functions of an effective team member and part of the process of becoming an effective team (Image 1.13).

Communication Influences How You Learn

You need to begin the process of improving your communication skills with the frame of mind that it will require effort, persistence, and self-correction. You learn to speak in public by first having conversations, then by answering questions and expressing your opinions in class, and finally by preparing and delivering a “stand-up” speech. Similarly, you learn to write by first learning to read, then by writing and learning to think critically. Your speaking and writing are reflections of your thoughts, experience, and education, and part of that combination is your level of experience listening to other speakers, reading documents and various styles of writing, and studying formats similar to what you aim to produce. Speaking and writing are both key communication skills that you will use in teams and groups.

As you study group communication, you may receive suggestions for improvement and clarification from professionals more experienced than yourself. Take their suggestions as challenges to improve—don’t give up when your first speech or first draft does not communicate the message you intended. Stick with it until you get it right. Your success in communicating is a skill that applies to almost every field of work, and it makes a difference in your relationships with others. Remember that luck is simply a combination of preparation and timing. You want to be prepared to communicate well when given the opportunity. Each time you do a good job, your success will bring more success.

Communication Represents You and Your Employer

You want to make a good first impression on your friends and family, on your instructors, and on your employer. They all want you to convey a positive image because it reflects on them. In your career, you will represent your business or company in teams and groups, and your professionalism and attention to detail will reflect positively on you and set you up for success.

As an effective member of the team, you will benefit from having the ability to communicate clearly and with clarity. You will use these skills for the rest of your life. Positive improvements in these skills will have a positive impact on your relationships, your prospects for employment, and your ability to make a difference in the world.

Communication Skills Are Desired by Business and Industry

Oral and written communication proficiencies are consistently ranked in the top 10 desirable skills by employer surveys year after year. In fact, high-powered business executives sometimes hire consultants to coach them in sharpening their communication skills. According to the National Association of Colleges Job Outlook 2023 survey (Gray, 2022), the top five attributes that employers seek on a candidate’s resumé are the following:

- Problem-solving skills

- Ability to work on a team

- Strong work ethic

- Analytical and quantitative skills

- Written communication skills

- Technical skills

Knowing this, you can see that one way for you to be successful and increase your promotion potential is to improve your ability to speak and write effectively.

Teams and groups are almost universal across all fields because no one person has all the skills, knowledge, or ability to do everything with an equal degree of excellence. Employees work with each other in manufacturing and service industries on a daily basis. An individual with excellent communication skills is an asset to every organization. No matter what career you plan to pursue, learning to interact, contribute, and excel in groups and teams will help you get there.

Digital and Electronic Communication Are Here to Stay

Computers and the internet entered the world in the 1940s and have been on the rise ever since. According to Jotform (2021), a global pandemic necessitated the use of digital and electronic communication because people were required to work from home as much as possible. Digital and electronic communication tools such as video-conferencing platforms, cloud storage, messaging platforms, and digital forms are now widely used and easily accessible. It’s not clear yet what digital and electronic communication methods will remain in use; however, because of their prevalence, we need to consider our communication skills in these digital and electronic environments.

Netiquette refers to etiquette, or protocols and norms for communication, when communicating using digital and electronic methods. Whatever digital device you use, written communication in the form of brief messages, or texting, has become a practical way to connect when talking on the phone or when meeting in person would be cumbersome. Texting is not useful for long or complicated messages, and careful consideration should be given to the audience. Email is frequently used to communicate among co-workers and has largely replaced print hard-copy letters for external (outside the company) correspondence, as well as taking the place of memos for internal (within the company) communication (Guffey, 2008). Email can be very useful for messages that have slightly more content than a text message, but it is still best used for fairly brief messages. Emails may be informal in personal contexts, but business communication requires attention to detail, an awareness that your email reflects you and your company, and a professional tone so that the email may be forwarded to a third party, if needed. Remember that when these tools are used for business, they need to convey professionalism and respect.

- Knowing what communication skills employers and current workplace environments require, what skills are you strong in right now? What skills do you need to develop?

- How do you see face-to-face and digital and electronic communication skills being similar and/or different? Where do you see face-to-face and digital and electronic communication in your future professional role?

Attribution

Unless otherwise indicated, material on this page has been reproduced or adapted from the following resource:

University of Minnesota. (2016). Communication in the real world: An introduction to communication studies . University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication , licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 , except where otherwise noted.

Alberta Health Services (AHS). (2023). Ethics & compliance . https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/about/Page645.aspx

Alberta Health Services (AHS). (2016). Code of conduct . https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/about/policies/ahs-pub-code-of-conduct.pdf

Alberta Therapeutic Recreation Association (ATRA). (2021). Code of ethics: A guide for ethical and moral decision-making for recreational therapists . https://www.alberta-tr.ca/media/91513/codeofethics11may2021.pdf

Bourque, T., & Horney, B. (2016). Principles of veterinary medical ethics of the CVMA . Canadian Veterinary Medical Association. https://www.canadianveterinarians.net/about-cvma/principles-of-veterinary-medical-ethics-of-the-cvma/

Canadian Veterinary Medical Association (CVMA). (2016). Principles of veterinary medical ethics of the CVMA . https://www.canadianveterinarians.net/media/o5qjghc0/principles-of-veterinary-medical-ethics-of-the-cvma.pdf

Child and Youth Care Association of Alberta (CYCAA). (2008). Code of ethics . https://www.cycaa.com/about-us/code-of-ethics

College of Alberta Dental Assistants (CADA). (2019). Code of ethics . http://abrda.ca/protecting-the-public/regulations-and-standards/code-of-ethics/

Cyr, C., Helgason, E., Appleton, K., & Yunick, A. (2021). Code of ethics: A guide for ethical and moral decision-making for recreation therapists . Alberta Therapeutic Recreation Association. https://www.alberta-tr.ca/media/91513/codeofethics11may2021.pdf

Ehrlich, T. (Ed.). (2000). Civic responsibility and higher education . Oryx Press.

Government of Alberta. (2023). Code of conduct and ethics for the Alberta Public Service . https://www.alberta.ca/code-of-conduct-and-ethics-for-the-alberta-public-service.aspx

Graduate Management Admission Council. (2017). Corporate recruiters survey report 2017 . https://www.mba.com/-/media/files/gmac/research/employment-outlook/2017-gmac-corporate-recruiters-web-release.pdf?la=en

Gray, K. (2022, November 15). As their focus on GPA fades, employers seek key skills on college grads’ resumes . National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE). https://www.naceweb.org/talent-acquisition/candidate-selection/as-their-focus-on-gpa-fades-employers-seek-key-skills-on-college-grads-resumes/

Guffey, M. (2008). Essentials of business communication (7th ed.). Thomson/Wadsworth.

Haas, M., & Mortensen, M. (2016, June). The secrets of great teamwork . Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/06/the-secrets-of-great-teamwork

Jotform. (2021, December 8). How technology has changed workplace communication . https://www.jotform.com/blog/technology-and-workplace-communication/

O’Rourke, J., & Yarbrough, B. (2008). Leading groups and teams . South-Western Cengage Learning.

Pearson, J., & Nelson, P. (2000). An introduction to human communication: Understanding and sharing . McGraw-Hill.

Rogers, E., & Steinfatt, T. (1999). I ntercultural communication . Waveland Press.

Therapy Assistant Association of Alberta (ThAAA). (2012). Code of ethics . http://thaaa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/ThAAA_Code-of-Ethics.pdf

Zabava Ford, W. S., & Wolvin, A. D. (1993). The differential impact of a basic communication course on perceived communication competencies in class, work, and social contexts. Communication Education, 42 (3), 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/0363452930937892

Image Credits (images are listed in order of appearance)

Figure 6. Graduation by Hippo px by U3167879, CC BY-SA 4.0

Protest-sofia-incinerator by 008all, CC BY-SA 4.0

Group of students in front of the DARM by Violetova , CC BY-SA 4.0

Meaning of ETHICS101 by Pokemon1244, CC BY-SA 4.0

Teamwork Skills Training Workplace Illustration by Digits.co.uk Images , CC BY 2.0

Introduction to Communications Copyright © 2023 by NorQuest College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

This site belongs to UNESCO's International Institute for Educational Planning

IIEP Learning Portal

Search form

- issue briefs

- Improve learning

Information and communication technology (ICT) in education

Information and communications technology (ict) can impact student learning when teachers are digitally literate and understand how to integrate it into curriculum..

Schools use a diverse set of ICT tools to communicate, create, disseminate, store, and manage information.(6) In some contexts, ICT has also become integral to the teaching-learning interaction, through such approaches as replacing chalkboards with interactive digital whiteboards, using students’ own smartphones or other devices for learning during class time, and the “flipped classroom” model where students watch lectures at home on the computer and use classroom time for more interactive exercises.

When teachers are digitally literate and trained to use ICT, these approaches can lead to higher order thinking skills, provide creative and individualized options for students to express their understandings, and leave students better prepared to deal with ongoing technological change in society and the workplace.(18)

ICT issues planners must consider include: considering the total cost-benefit equation, supplying and maintaining the requisite infrastructure, and ensuring investments are matched with teacher support and other policies aimed at effective ICT use.(16)

Issues and Discussion

Digital culture and digital literacy: Computer technologies and other aspects of digital culture have changed the ways people live, work, play, and learn, impacting the construction and distribution of knowledge and power around the world.(14) Graduates who are less familiar with digital culture are increasingly at a disadvantage in the national and global economy. Digital literacy—the skills of searching for, discerning, and producing information, as well as the critical use of new media for full participation in society—has thus become an important consideration for curriculum frameworks.(8)

In many countries, digital literacy is being built through the incorporation of information and communication technology (ICT) into schools. Some common educational applications of ICT include:

- One laptop per child: Less expensive laptops have been designed for use in school on a 1:1 basis with features like lower power consumption, a low cost operating system, and special re-programming and mesh network functions.(42) Despite efforts to reduce costs, however, providing one laptop per child may be too costly for some developing countries.(41)

- Tablets: Tablets are small personal computers with a touch screen, allowing input without a keyboard or mouse. Inexpensive learning software (“apps”) can be downloaded onto tablets, making them a versatile tool for learning.(7)(25) The most effective apps develop higher order thinking skills and provide creative and individualized options for students to express their understandings.(18)

- Interactive White Boards or Smart Boards : Interactive white boards allow projected computer images to be displayed, manipulated, dragged, clicked, or copied.(3) Simultaneously, handwritten notes can be taken on the board and saved for later use. Interactive white boards are associated with whole-class instruction rather than student-centred activities.(38) Student engagement is generally higher when ICT is available for student use throughout the classroom.(4)

- E-readers : E-readers are electronic devices that can hold hundreds of books in digital form, and they are increasingly utilized in the delivery of reading material.(19) Students—both skilled readers and reluctant readers—have had positive responses to the use of e-readers for independent reading.(22) Features of e-readers that can contribute to positive use include their portability and long battery life, response to text, and the ability to define unknown words.(22) Additionally, many classic book titles are available for free in e-book form.

- Flipped Classrooms: The flipped classroom model, involving lecture and practice at home via computer-guided instruction and interactive learning activities in class, can allow for an expanded curriculum. There is little investigation on the student learning outcomes of flipped classrooms.(5) Student perceptions about flipped classrooms are mixed, but generally positive, as they prefer the cooperative learning activities in class over lecture.(5)(35)

ICT and Teacher Professional Development: Teachers need specific professional development opportunities in order to increase their ability to use ICT for formative learning assessments, individualized instruction, accessing online resources, and for fostering student interaction and collaboration.(15) Such training in ICT should positively impact teachers’ general attitudes towards ICT in the classroom, but it should also provide specific guidance on ICT teaching and learning within each discipline. Without this support, teachers tend to use ICT for skill-based applications, limiting student academic thinking.(32) To support teachers as they change their teaching, it is also essential for education managers, supervisors, teacher educators, and decision makers to be trained in ICT use.(11)

Ensuring benefits of ICT investments: To ensure the investments made in ICT benefit students, additional conditions must be met. School policies need to provide schools with the minimum acceptable infrastructure for ICT, including stable and affordable internet connectivity and security measures such as filters and site blockers. Teacher policies need to target basic ICT literacy skills, ICT use in pedagogical settings, and discipline-specific uses. (21) Successful implementation of ICT requires integration of ICT in the curriculum. Finally, digital content needs to be developed in local languages and reflect local culture. (40) Ongoing technical, human, and organizational supports on all of these issues are needed to ensure access and effective use of ICT. (21)

Resource Constrained Contexts: The total cost of ICT ownership is considerable: training of teachers and administrators, connectivity, technical support, and software, amongst others. (42) When bringing ICT into classrooms, policies should use an incremental pathway, establishing infrastructure and bringing in sustainable and easily upgradable ICT. (16) Schools in some countries have begun allowing students to bring their own mobile technology (such as laptop, tablet, or smartphone) into class rather than providing such tools to all students—an approach called Bring Your Own Device. (1)(27)(34) However, not all families can afford devices or service plans for their children. (30) Schools must ensure all students have equitable access to ICT devices for learning.

Inclusiveness Considerations

Digital Divide: The digital divide refers to disparities of digital media and internet access both within and across countries, as well as the gap between people with and without the digital literacy and skills to utilize media and internet.(23)(26)(31) The digital divide both creates and reinforces socio-economic inequalities of the world’s poorest people. Policies need to intentionally bridge this divide to bring media, internet, and digital literacy to all students, not just those who are easiest to reach.

Minority language groups: Students whose mother tongue is different from the official language of instruction are less likely to have computers and internet connections at home than students from the majority. There is also less material available to them online in their own language, putting them at a disadvantage in comparison to their majority peers who gather information, prepare talks and papers, and communicate more using ICT. (39) Yet ICT tools can also help improve the skills of minority language students—especially in learning the official language of instruction—through features such as automatic speech recognition, the availability of authentic audio-visual materials, and chat functions. (2)(17)

Students with different styles of learning: ICT can provide diverse options for taking in and processing information, making sense of ideas, and expressing learning. Over 87% of students learn best through visual and tactile modalities, and ICT can help these students ‘experience’ the information instead of just reading and hearing it. (20)(37) Mobile devices can also offer programmes (“apps”) that provide extra support to students with special needs, with features such as simplified screens and instructions, consistent placement of menus and control features, graphics combined with text, audio feedback, ability to set pace and level of difficulty, appropriate and unambiguous feedback, and easy error correction. (24)(29)

Plans and policies

- India [ PDF ]

- Detroit, USA [ PDF ]

- Finland [ PDF ]

- Alberta Education. 2012. Bring your own device: A guide for schools . Retrieved from http://education.alberta.ca/admin/technology/research.aspx

- Alsied, S.M. and Pathan, M.M. 2015. ‘The use of computer technology in EFL classroom: Advantages and implications.’ International Journal of English Language and Translation Studies . 1 (1).

- BBC. N.D. ‘What is an interactive whiteboard?’ Retrieved from http://www.bbcactive.com/BBCActiveIdeasandResources/Whatisaninteractivewhiteboard.aspx

- Beilefeldt, T. 2012. ‘Guidance for technology decisions from classroom observation.’ Journal of Research on Technology in Education . 44 (3).

- Bishop, J.L. and Verleger, M.A. 2013. ‘The flipped classroom: A survey of the research.’ Presented at the 120th ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition. Atlanta, Georgia.

- Blurton, C. 2000. New Directions of ICT-Use in Education . United National Education Science and Culture Organization (UNESCO).

- Bryant, B.R., Ok, M., Kang, E.Y., Kim, M.K., Lang, R., Bryant, D.P. and Pfannestiel, K. 2015. ‘Performance of fourth-grade students with learning disabilities on multiplication facts comparing teacher-mediated and technology-mediated interventions: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Behavioral Education. 24.

- Buckingham, D. 2005. Educación en medios. Alfabetización, aprendizaje y cultura contemporánea, Barcelona, Paidós.

- Buckingham, D., Sefton-Green, J., and Scanlon, M. 2001. 'Selling the Digital Dream: Marketing Education Technologies to Teachers and Parents.' ICT, Pedagogy, and the Curriculum: Subject to Change . London: Routledge.

- "Burk, R. 2001. 'E-book devices and the marketplace: In search of customers.' Library Hi Tech 19 (4)."

- Chapman, D., and Mählck, L. (Eds). 2004. Adapting technology for school improvement: a global perspective. Paris: International Institute for Educational Planning.

- Cheung, A.C.K and Slavin, R.E. 2012. ‘How features of educational technology applications affect student reading outcomes: A meta-analysis.’ Educational Research Review . 7.

- Cheung, A.C.K and Slavin, R.E. 2013. ‘The effectiveness of educational technology applications for enhancing mathematics achievement in K-12 classrooms: A meta-analysis.’ Educational Research Review . 9.

- Deuze, M. 2006. 'Participation Remediation Bricolage - Considering Principal Components of a Digital Culture.' The Information Society . 22 .

- Dunleavy, M., Dextert, S. and Heinecke, W.F. 2007. ‘What added value does a 1:1 student to laptop ratio bring to technology-supported teaching and learning?’ Journal of Computer Assisted Learning . 23.

- Enyedy, N. 2014. Personalized Instruction: New Interest, Old Rhetoric, Limited Results, and the Need for a New Direction for Computer-Mediated Learning . Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center.

- Golonka, E.M., Bowles, A.R., Frank, V.M., Richardson, D.L. and Freynik, S. 2014. ‘Technologies for foreign language learning: A review of technology types and their effectiveness.’ Computer Assisted Language Learning . 27 (1).

- Goodwin, K. 2012. Use of Tablet Technology in the Classroom . Strathfield, New South Wales: NSW Curriculum and Learning Innovation Centre.

- Jung, J., Chan-Olmsted, S., Park, B., and Kim, Y. 2011. 'Factors affecting e-book reader awareness, interest, and intention to use.' New Media & Society . 14 (2)

- Kenney, L. 2011. ‘Elementary education, there’s an app for that. Communication technology in the elementary school classroom.’ The Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications . 2 (1).

- Kopcha, T.J. 2012. ‘Teachers’ perceptions of the barriers to technology integration and practices with technology under situated professional development.’ Computers and Education . 59.

- Miranda, T., Williams-Rossi, D., Johnson, K., and McKenzie, N. 2011. "Reluctant readers in middle school: Successful engagement with text using the e-reader.' International journal of applied science and technology . 1 (6).

- Moyo, L. 2009. 'The digital divide: scarcity, inequality and conflict.' Digital Cultures . New York: Open University Press.